Submitted:

07 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

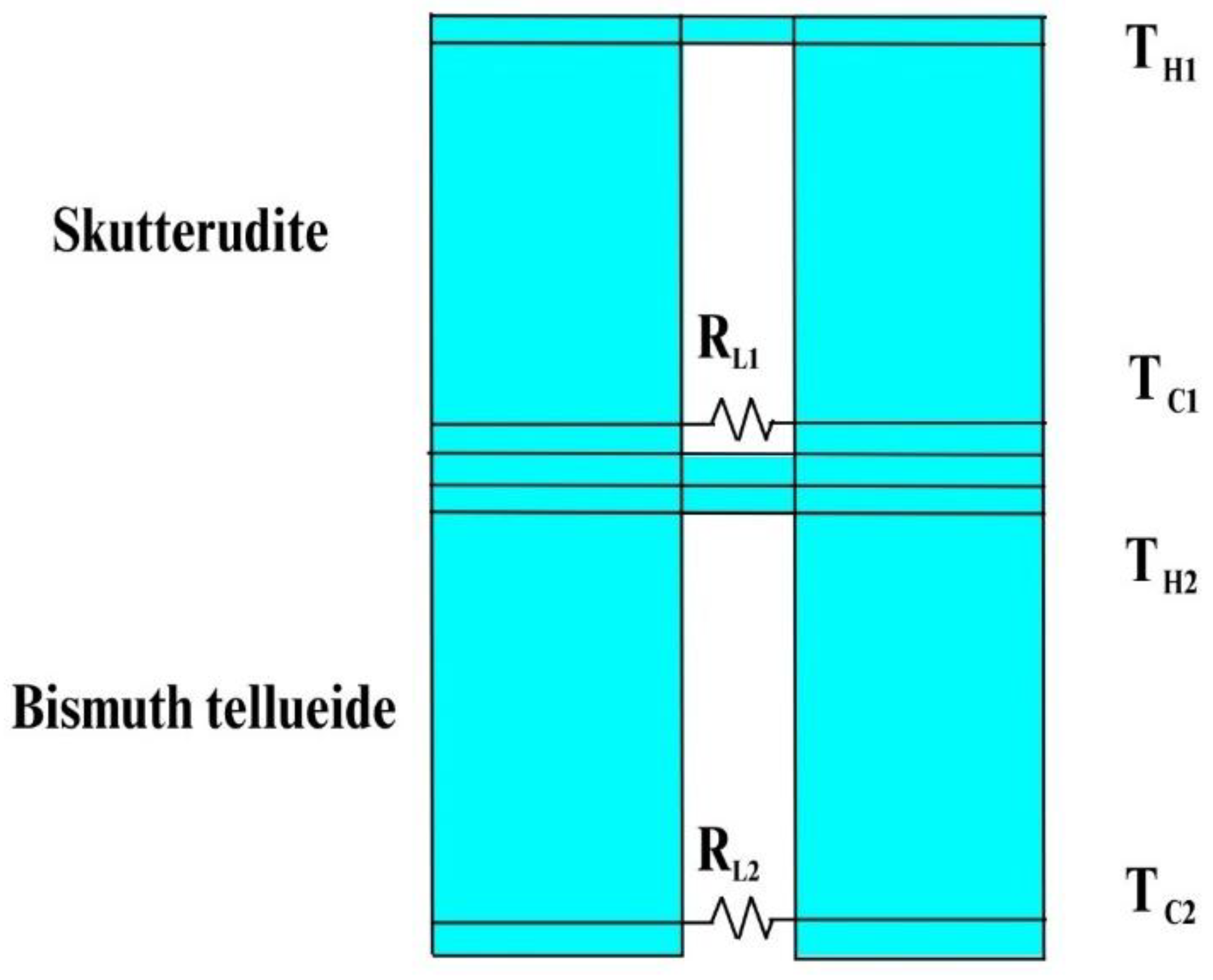

This project presents the design, fabrication, and performance study of a solar thermoelectric generator. Solar energy is considered one of the most effective types and sources of renewable energy. Among the available options, solar energy has predominantly been harnessed through the use of solar PV panels. However, solar PV panels are quite expensive, an alternative system is designed to utilize solar energy through thermoelectric generators. This new design is a cheaper system because it replaces solar PV panels with thermoelectric generators that can absorb heat and convert it directly into electricity through a concept known as the Seebeck effect. The Seebeck effect is based on the temperature difference between two sides. By heating the hot side of a thermoelectric material, electrons migrate from the hot side to the cooler side, thereby generating an electrical current. Since the Seebeck effect depends on higher temperature differences for more efficiency, a cooling system positioned below which will cool the cold side of the STEG, while the sun above will heat the hot side, creating a higher temperature difference and improved efficiency. This system focuses on a two-stage thermoelectric generator comprised of two modules: a lower-temperature generator and a medium-temperature generator. In accordance with the optimal operating temperature of thermoelectric materials, the medium-temperature generator is positioned on the hot side, while the lower-temperature generator is situated on the cold side. Ultimately, the performance of the two-stage STEG is assessed across various operational conditions. The primary advantage of employing a two-stage STEG is that the heat-to-electricity conversion process occurs twice as the heat passes through the two-stage STEG, resulting in higher efficiency compared to a single-stage thermoelectric generator.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of Thermoelectric Generator

- Reliability - Solid-state electronics include thermoelectric generators. They are extremely dependable since they are no moving components to fail or wear out. Thermoelectric generators have an exceptionally long lifespan. As of this writing, the Voyager 1 spacecraft's thermoelectric generator has been in service for 41 years. Without any maintenance or repairs, it has logged more over 13 billion miles of the journey.

- Quiet - It is possible to build thermoelectric generators to be absolutely quiet.

- No Greenhouse Gases - There are no greenhouse emissions needed to run thermoelectric generators. Some technologies for energy conversion do.

- Wide Range of Fuel Sources - The types of fuels that may be utilized to produce the necessary heat with thermoelectric generators are not constrained. This is true of many different energy conversion systems.

- Scalability - Microwatts to kilowatts of power may be generated using thermoelectric generators.

- Mountable in Any Orientation - In any position, the thermoelectric generator's function. Depending on how they are oriented in relation to gravity, several energy conversion devices are sensitive.

- Operation Under high and Zero G-forces - High-G or zero-G operating conditions are also possible for thermoelectric generators. Other energy conversion systems can't, though.

- Direct Energy Conversion - Heat is immediately converted into electricity using thermoelectric generators. When converting heat to electricity, several energy conversion systems demand intermediary processes. For instance, the thermal energy from the fuel is transformed into mechanical energy in a turbine, and the mechanical energy is subsequently transformed into electrical energy in a generator. Waste heat losses are added with each energy conversion stage. In comparison to certain other energy conversion methods, thermoelectric generators are less mechanically difficult because of this.

- Compact Size - Compact thermoelectric generator designs are possible. Greater design freedom results from this.

1.2. Principle of Thermoelectric Generator

1.3. Objectives of the Study

- I.

- To Design a Solar Thermoelectric Generator.

- II.

- To Fabricate a Solar Thermoelectric Generator.

- III.

- To Study the performance of a Solar Thermoelectric Generator under different temperatures.

1.4. Structure of the Thesis

2. Literature Review

3. Description of the Model/System

3.1. Generator Specification and Operating Parameter

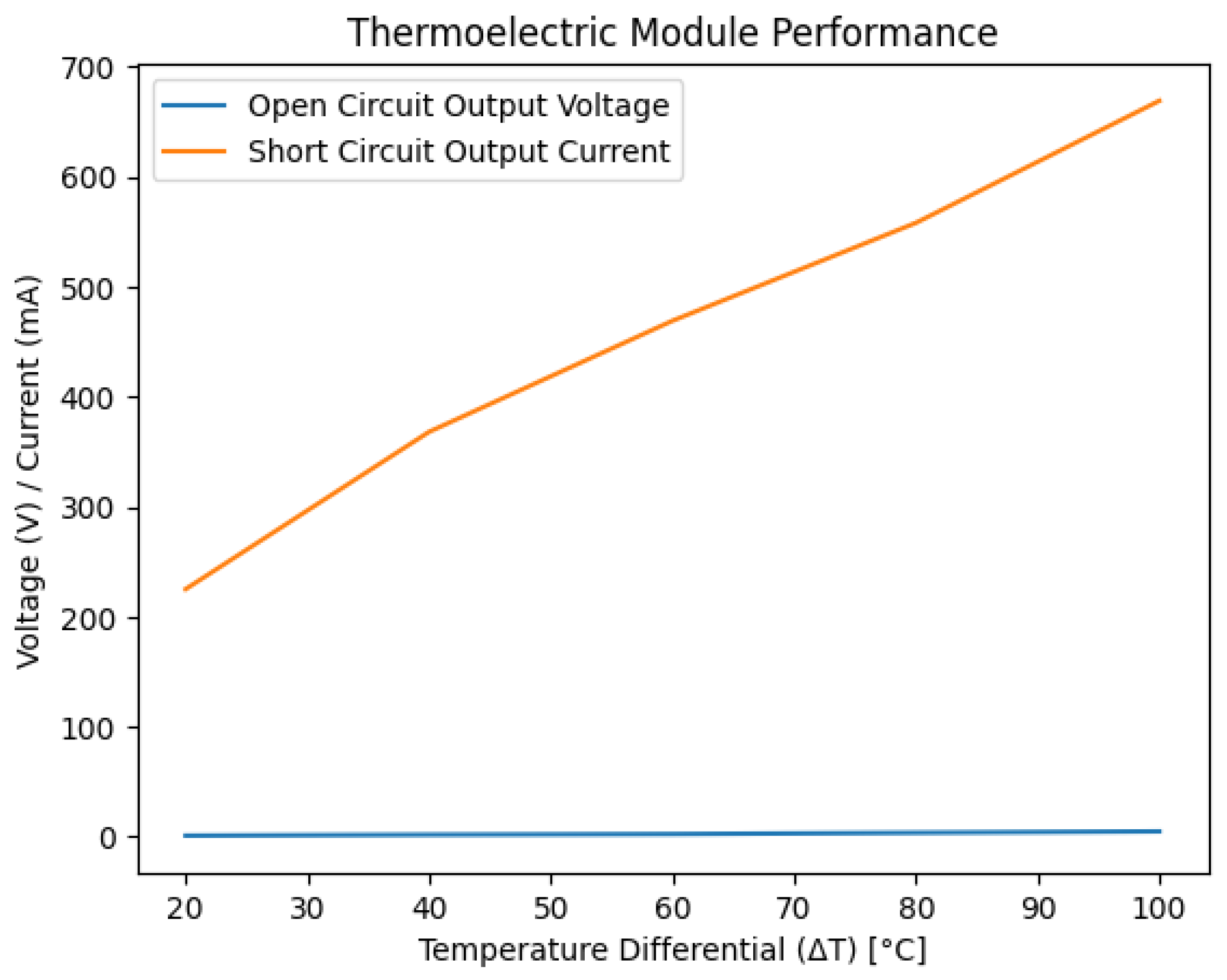

- i.

- The Thevenin voltage (open-circuit) is 0.9V and the produced current is 225mA when the temperature difference approaches 20°C.

- ii.

- The Thevenin voltage (open-circuit) is 1.8V and the produced current is 368mA when the temperature difference approaches 40°C.

- iii.

- The Thevenin voltage (open-circuit) 2.4V and the produced current is 469mA when the temperature difference approaches 60°C.

- iv.

- The Thevenin voltage (open-circuit) is 3.6V and the produced current is 558mA when the temperature difference approaches 80°C.

- v.

- The Thevenin voltage (open-circuit) is 4.8V and the produced current is 669mA when the temperature difference approaches 100°C.

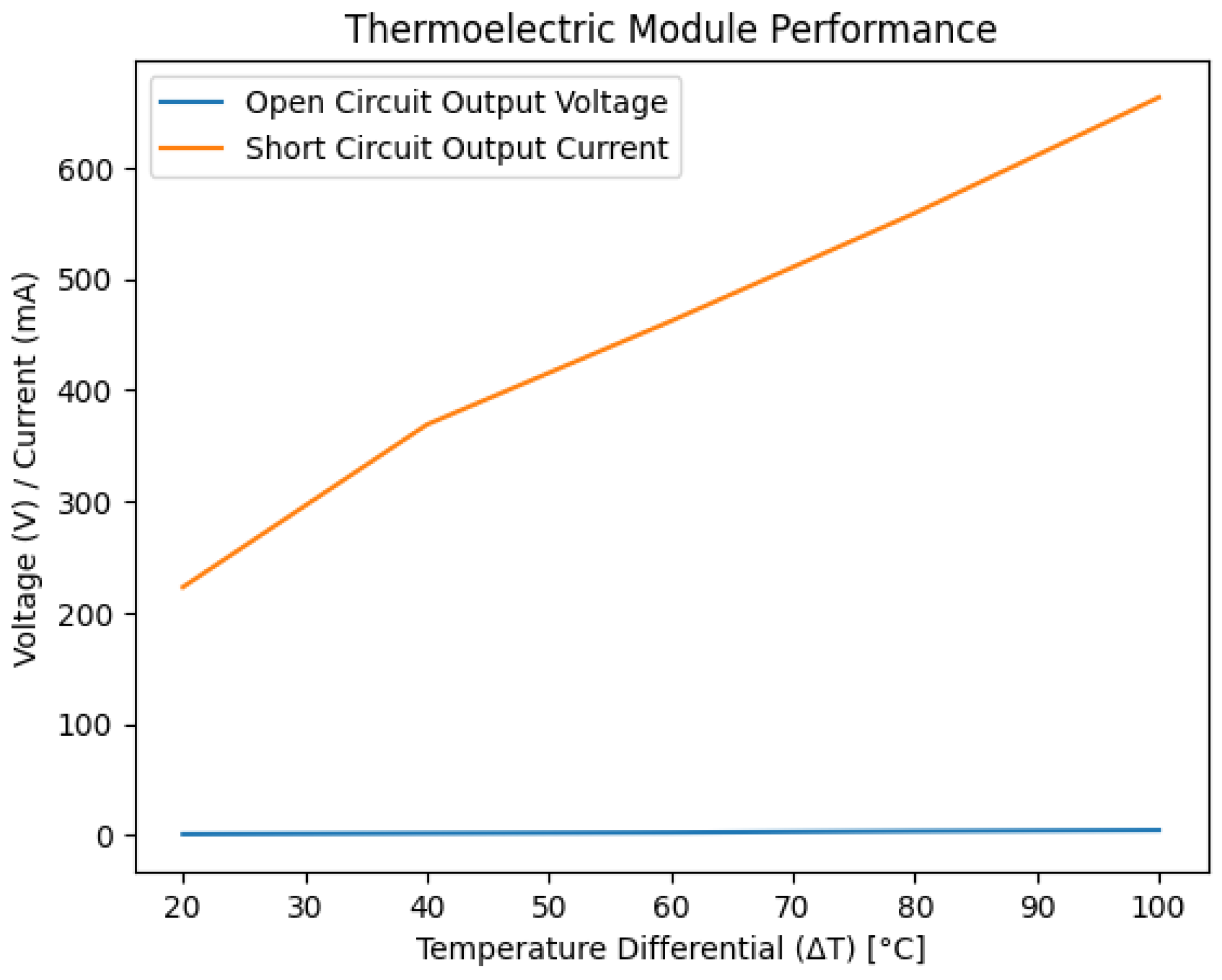

- i.

- The Thevenin voltage (open-circuit) is 2.2V and the produced current is 390mA when the temperature difference approaches 40°C.

- ii.

- The Thevenin voltage (open-circuit) is 3.6V and the produced current is 489mA when the temperature difference approaches 60°C.

- iii.

- The Thevenin voltage (open-circuit) is 4.8V and the produced current is 569mA when the temperature difference approaches 80°C.

- iv.

- The Thevenin voltage (open-circuit) is 6.0V and the produced current is 658mA when the temperature difference approaches 100°C.

- v.

- The Thevenin voltage (open-circuit) is 7.2V and the produced current is 759mA when the temperature difference approaches 120°C.

- vi.

- The Thevenin voltage (open-circuit) is 8.4V and the produced current is 969mA when the temperature difference approaches 140°C.

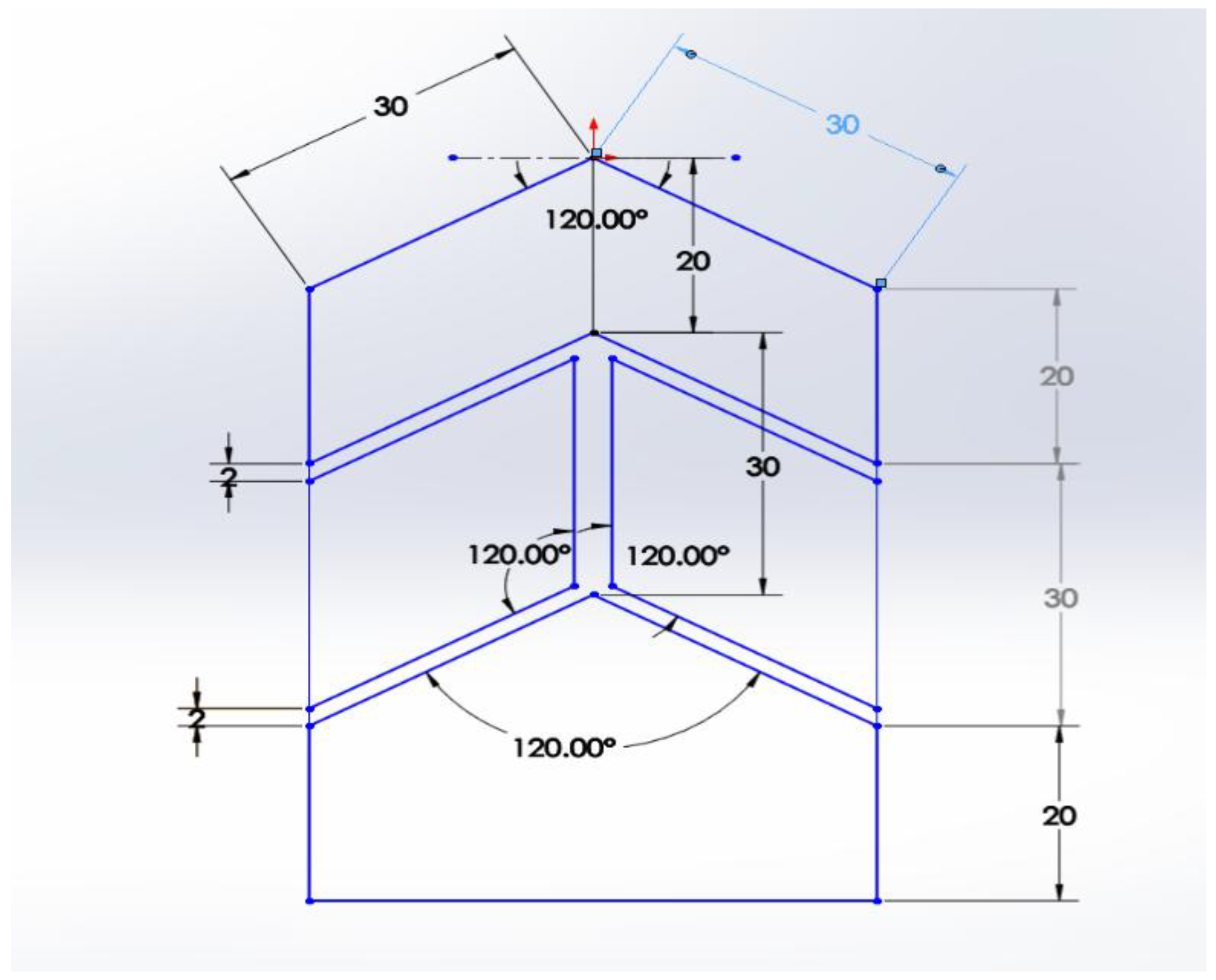

3.2. Solar Tilt Angle Analysis

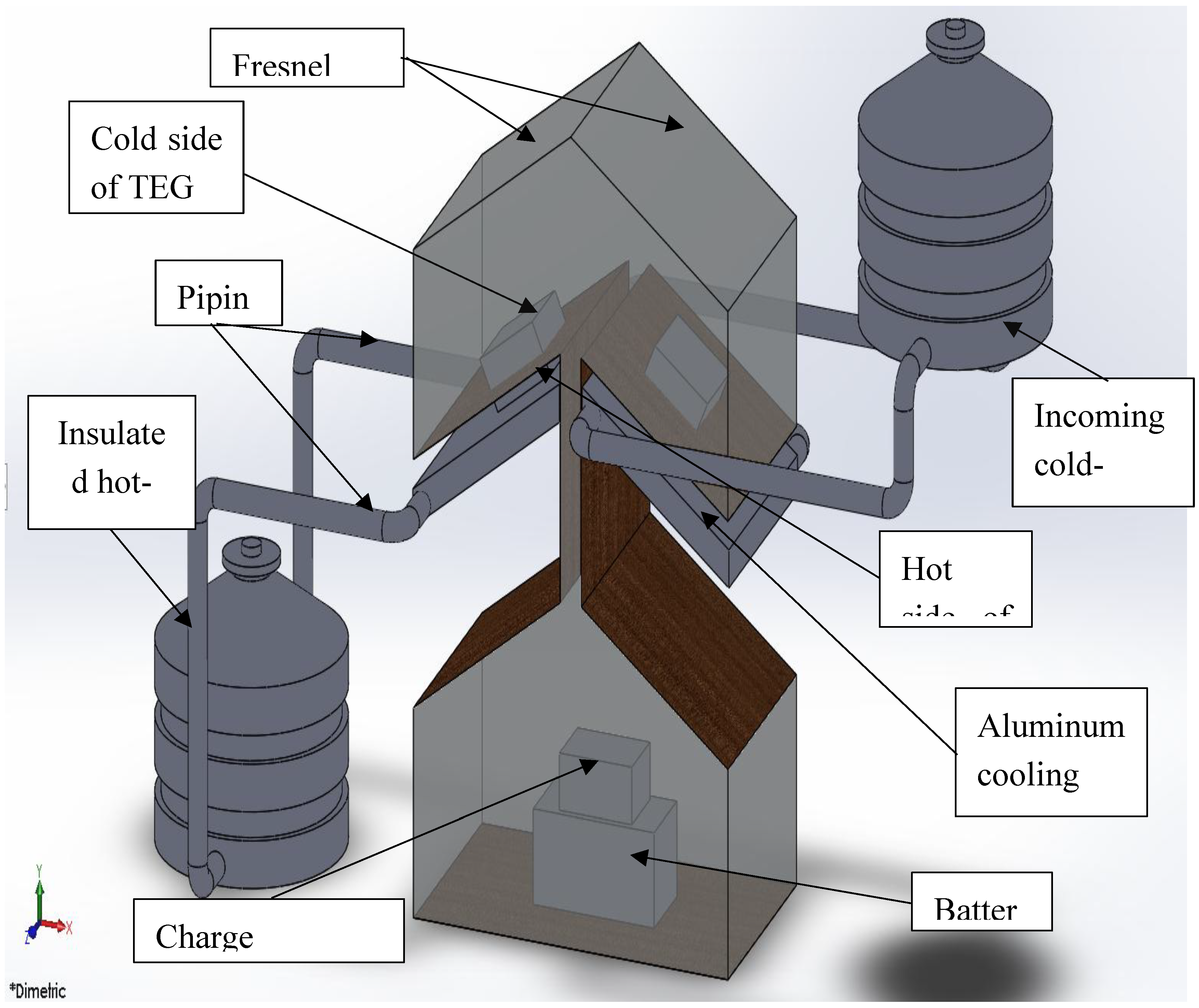

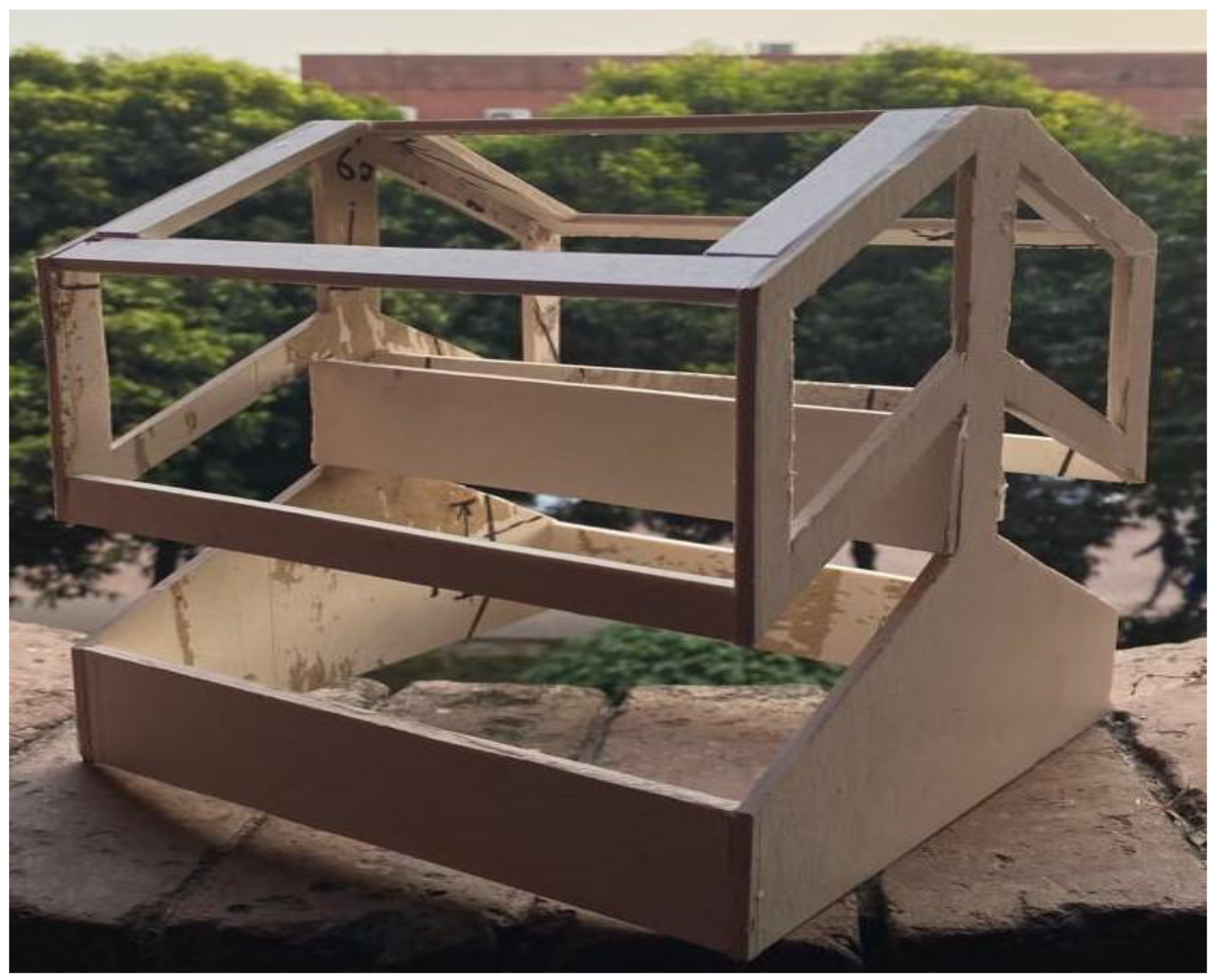

3.3. Configuration of STEG

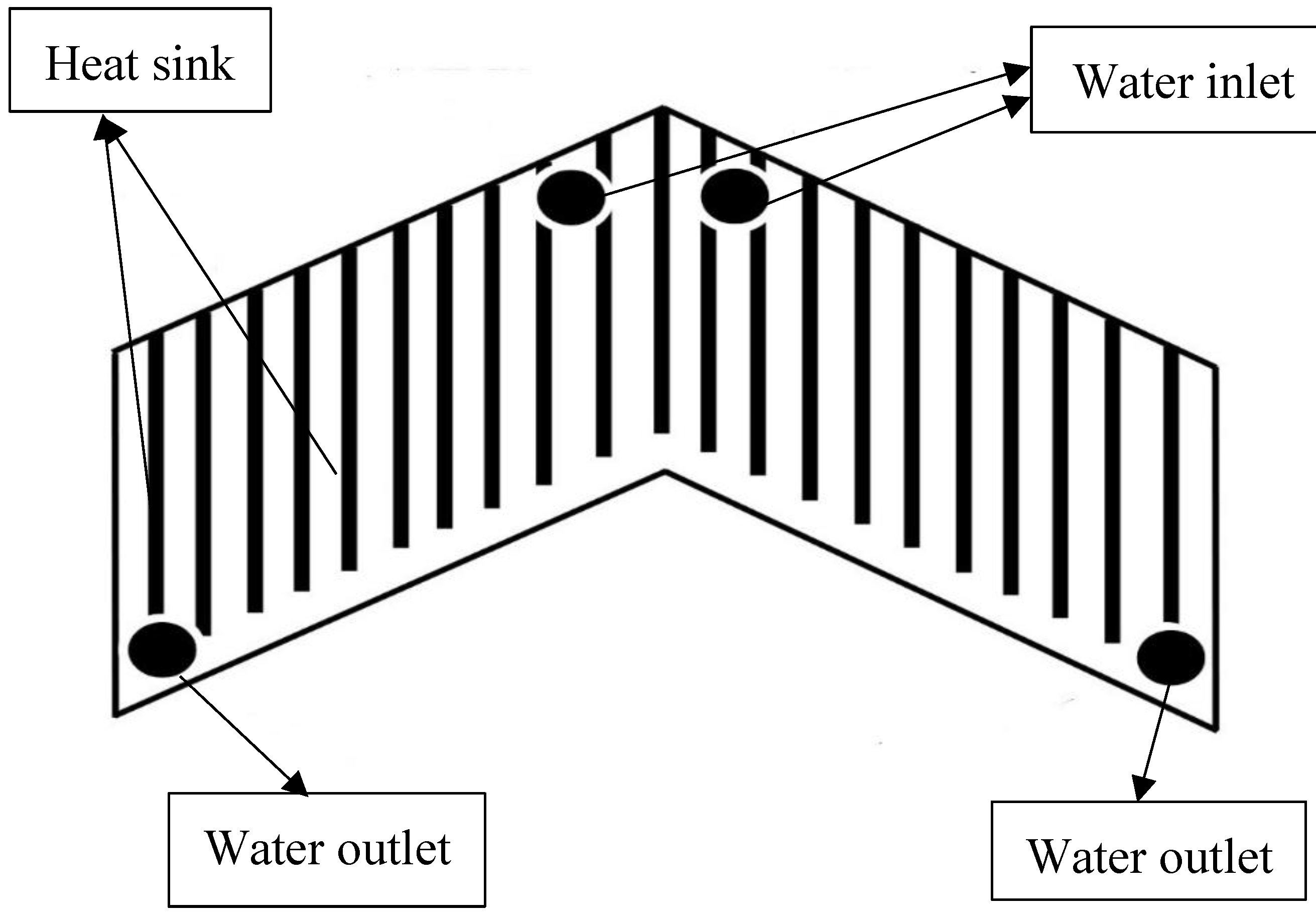

3.4. Cooling System of STEG

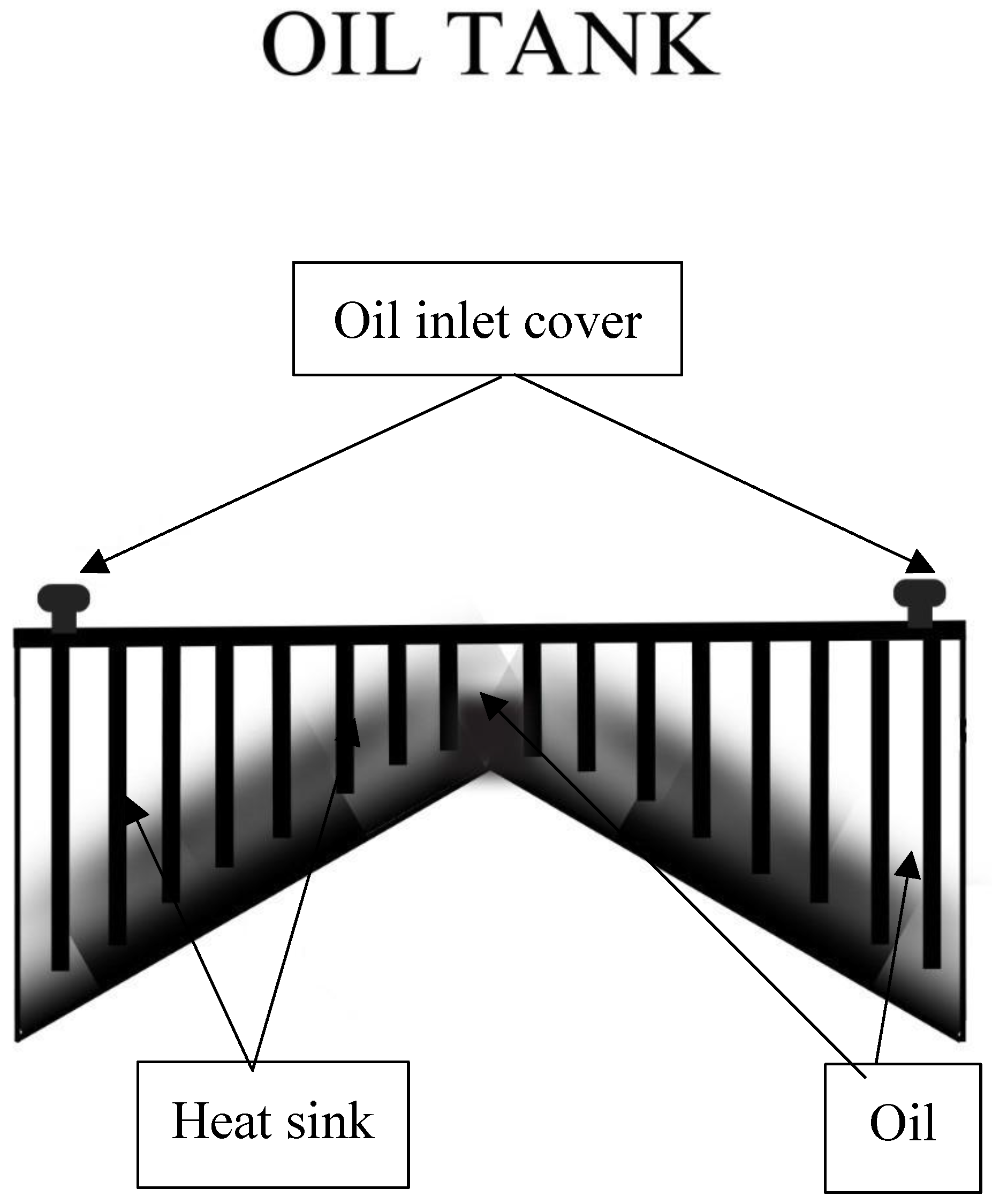

3.5. Heating System of STEG

4. Computational Methodology

4.1. Computational Methodology

4.2. Governing Equations of Coupled Thermoelectricity

4.3. Performance Analysis

- i.

- Testing and evaluation of the SSTEG system.

- ii.

- Measurement of electrical power output under varying solar radiation.

- iii.

- Efficiency calculation using the power output and incident solar energy.

4.4. Environmental Impact Analysis

5. Results and Discussions

5.1. Solar Fresnel lens Power Output Calculation

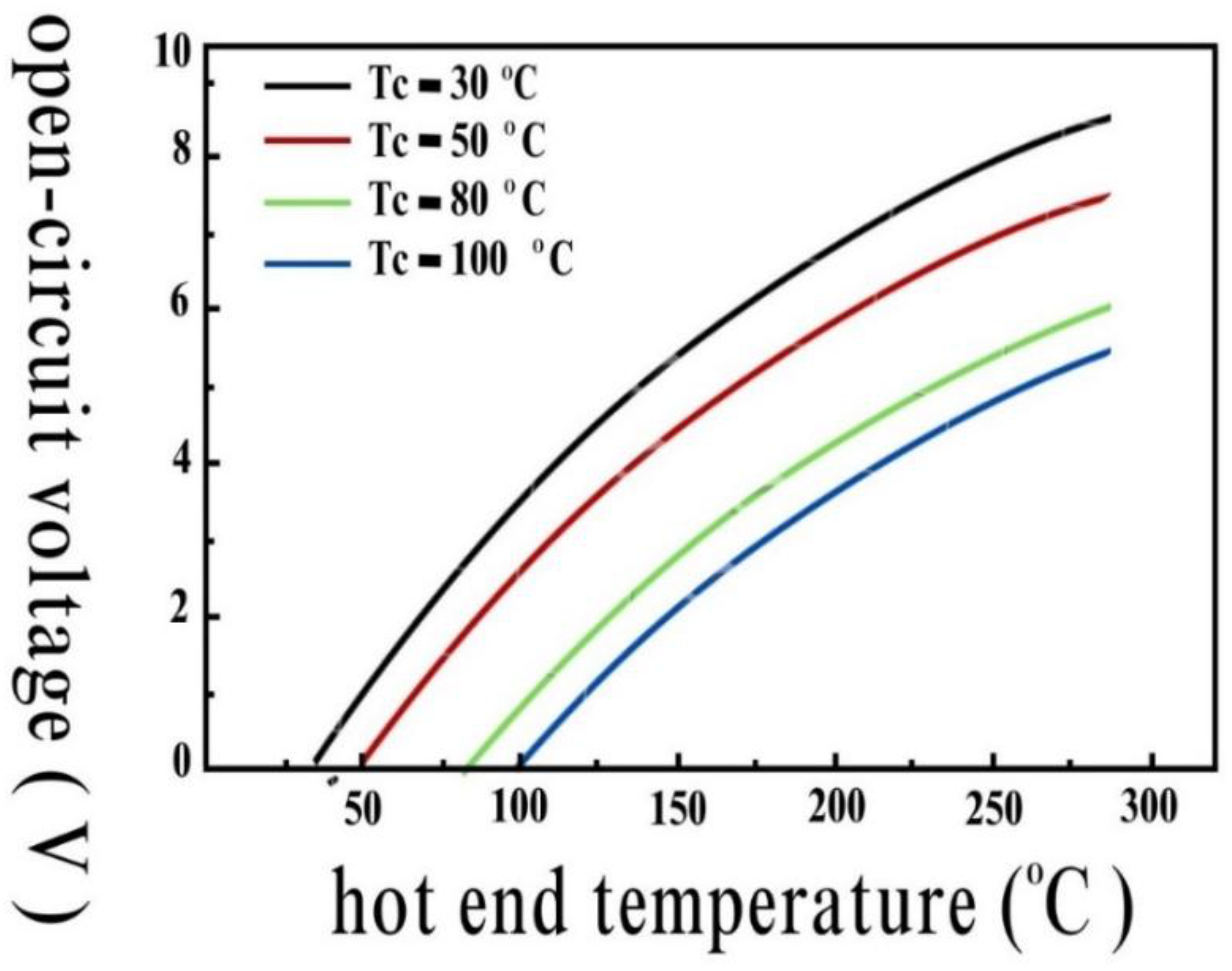

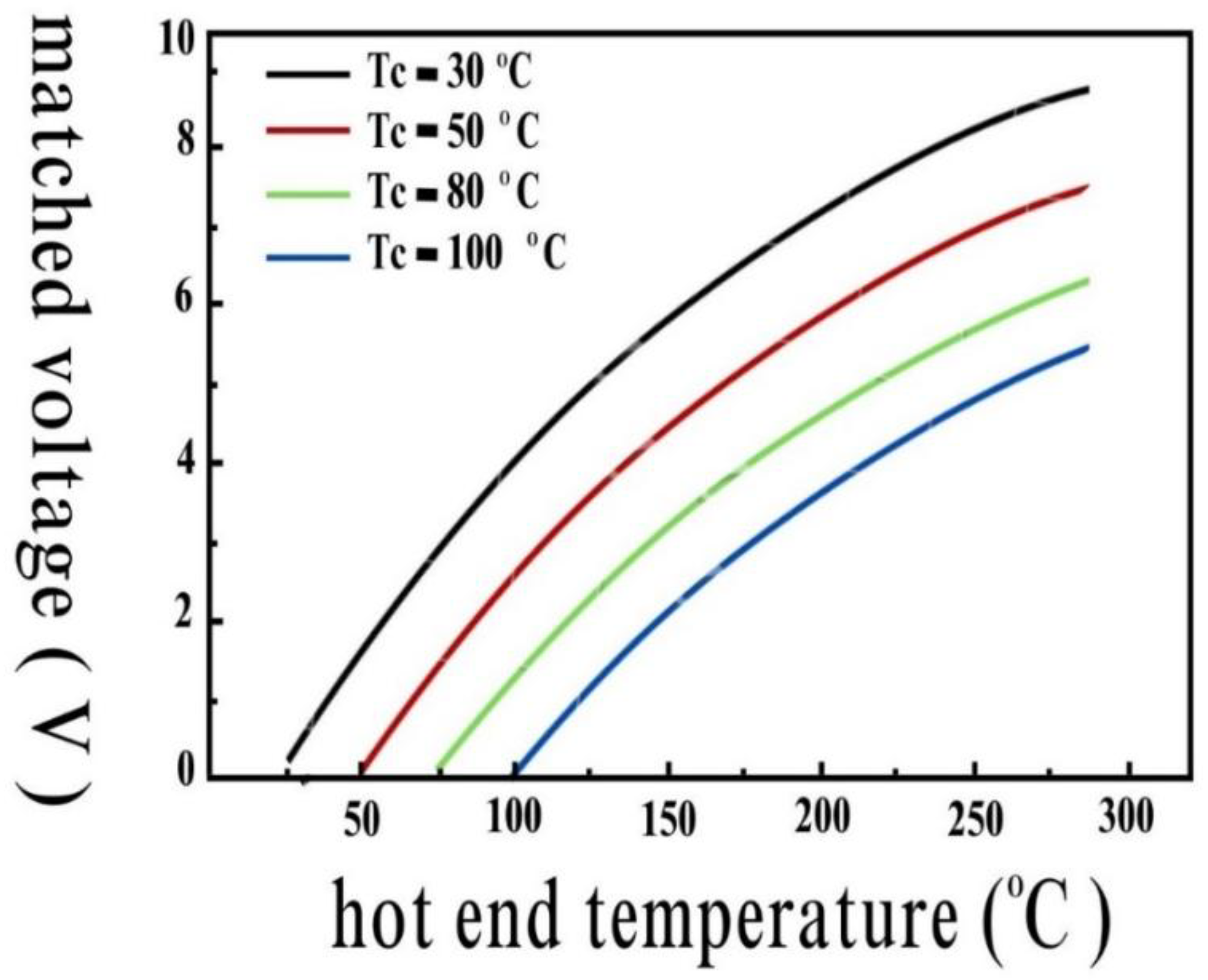

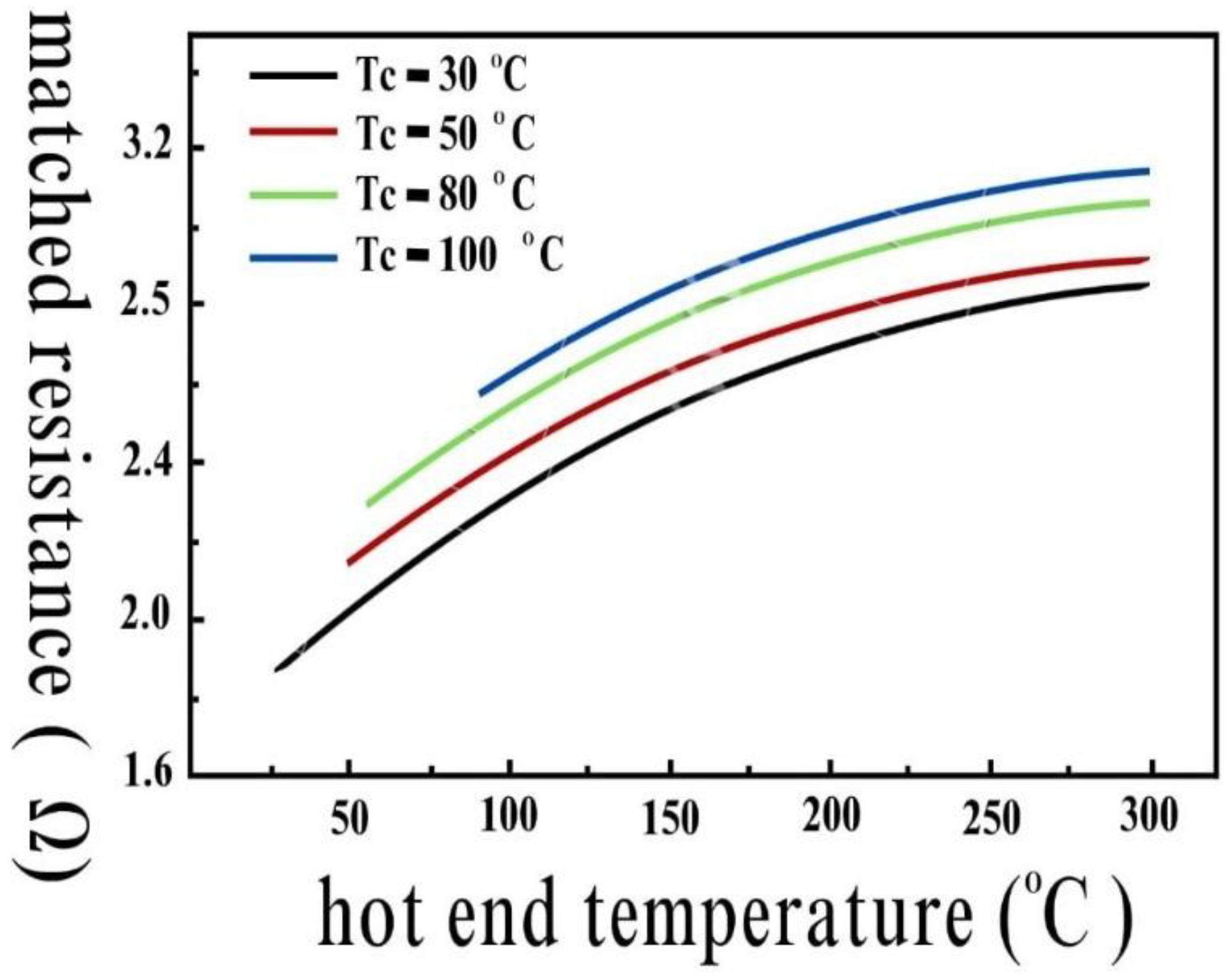

5.2. Results

5.3. Discussions

5.4. Comparison with Other Technologies like Solar PV

- I.

-

Principle of Operation:

- Solar PV: Solar PV technology converts sunlight directly into electricity using semiconducting materials. When photons from sunlight strike the PV cells, they generate an electric current through the photovoltaic effect.

- STEG: The STEG operates on the principle of the thermoelectric effect, converting temperature differentials into electricity. It utilizes the temperature gradient between the hot side (exposed to sunlight) and the cold side to generate electricity through thermoelectric materials [30].

- II.

-

Efficiency:

- Solar PV: PV systems have achieved high levels of efficiency, with some commercial panels exceeding 20%. However, their efficiency decreases at higher temperatures, leading to reduced performance in hot climates.

- STEG: The efficiency of STEG systems is typically lower compared to PV, but they can still offer advantages in certain scenarios. STEGs can operate more efficiently in environments with high-temperature differentials, such as concentrated solar power (CSP) applications or solar thermal collectors [31].

- III.

-

Power Generation:

- Solar PV: PV systems generate electricity continuously when exposed to sunlight, offering a consistent power output during daylight hours. The power output depends on factors such as solar irradiance, panel orientation, shading, and temperature.

- STEG: STEGs can provide power generation in situations where there are substantial temperature differentials, such as solar thermal applications. They are especially useful in environments where direct sunlight is less available, such as remote or cloudy regions. Additionally, STEGs can potentially operate in both sunlight and waste heat recovery applications [32].

- IV.

-

Scalability and Flexibility:

- Solar PV: PV systems are highly scalable and modular, allowing for easy expansion and installation on various surfaces such as rooftops or large-scale solar farms. They can be integrated into building designs and connected to the grid.

- STEG: STEG systems have the advantage of being potentially more flexible in terms of form factor and integration options. They can be designed as standalone devices or integrated into existing thermal systems to harness waste heat. However, their scalability might be limited due to the availability of suitable temperature differentials and thermoelectric material performance [33].

- V.

-

Cost:

- Solar PV: PV technology has experienced significant cost reductions over the years, making it more affordable and accessible. Economies of scale, technological advancements, and government incentives have contributed to the declining cost of PV systems.

- STEG: STEG systems, especially those utilizing advanced thermoelectric materials, may still be relatively more expensive compared to PV systems. However, their cost-effectiveness can be enhanced by utilizing waste heat recovery or concentrating solar power applications. In Addition, while solar PV technology has achieved widespread adoption and high-efficiency levels, the solar thermoelectric generator (STEG) offers unique advantages in scenarios with substantial temperature differentials and waste heat recovery. STEGs can be beneficial in environments where direct sunlight is limited, providing an alternative or complementary solution to solar PV. Further research and development in thermoelectric materials and system design can enhance the performance and cost-effectiveness of STEGs, making them more competitive with solar PV and other solar energy conversion technologies [34].

6. Conclusions

6.1. Conclusion

6.2. Recommendation for Future Works

Acknowledgment

Nomenclatures and Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| STEG | Solar Thermoelectric generator |

| TEC | Thermoelectric cooler |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| ZT | Dimensionless figure of merit |

List of symbols:

| [℃] | Temperature | |

| [J/KgK] | Specific heat | |

| [W/m2] | Vector of heat flux | |

| [W/m3] | Rate of heat generation by volume | |

| [V/m] | Vector of electric field intensity | |

| [C/m2] | Density of electric flux vector | |

| [A/m2] | Density of electric current vector | |

| Qin | [W] | Input power |

| P | [W] | Output power |

| I | [A] | Electric current |

| RL | [Ω] | Electric resistance |

| ρ | [Kg/m3] | Density |

| [λ] | [W/mK] | Matrix of thermal conductivity |

| [σ] | [S/m] | Matrix of electrical conductivity |

| [α] | [V/K] | Matrix of see-beck coefficient |

| [ε] | [F/m] | Matrix of dielectric permittivity |

| φ | [v] | Electric potential |

| a | [uV/ ℃] | Temperature electromotive force |

| qsolar | [KW/m2] | Density of solar radiation flux |

| Cg | Optical focusing system concentration ratio | |

| ηSTEG | Solar thermoelectric generator total efficiency | |

| ηTE | Efficiency of thermoelectric conversion | |

| ηopt | Efficiency of optical focusing system | |

| ηa | Heat collector absorption | |

References

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Solar thermoelectric generator: A review of materials, performance, and applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 108, 537–552. [Google Scholar]

- Rezk, H.; Rezk, E. Solar thermoelectric generators: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 43, 1331–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.W.; Shi, J. Solar thermoelectric energy conversion. Materials Today 2014, 17, 385–392. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, T.; Mahanwar, G.P. Thermoelectric generator using solar energy: A review. Energy Reports 2020, 6, 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hochbaum, A.I.; Chen, R.; Delgado, R.D.; et al. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of rough silicon nanowires. Nature 2008, 451, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, G.J.; Toberer, E.S. Complex thermoelectric materials. Nature Materials 2008, 7, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, S.; et al. Nanostructured thermoelectric materials: Current research and future challenges. Progress in Materials Science 2019, 99, 180–269. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, G.; Sun, B. Recent progress and perspective in thermoelectric materials research: A personal viewpoint. Materials Today Physics 2017, 2, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Shakouri, A. Recent developments in semiconductor thermoelectric physics and materials. Annual Review of Materials Research 2011, 41, 399–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Fleurial, J.P. Thermoelectric materials research: Historical review and current trends. Journal of Materials Research 2011, 26, 814–819. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc, S.P.; Snyder, G.J. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of rough lead telluride nanocomposites. Physical Review B 2009, 80, 075412. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Borca-Tasciuc, T.; Johnson, L.M.; et al. Fabrication and characterization of textured bismuth telluride thick films with high thermoelectric performance. Journal of Applied Physics 2006, 100, 124907. [Google Scholar]

- Dames, C.; Chen, G. Theoretical phonon thermal conductivity of Si and Ge nanowires. Physical Review B 2007, 75, 085409. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, S.P.; Iverson, R.B. Performance limits for flat-plate solar thermoelectric generators. Journal of Applied Physics 1982, 53, 4899–4906. [Google Scholar]

- Lenert, A.; Bierman, D.M.; Nam, Y.; et al. A nanophotonic solar thermophotovoltaic device. Nature Nanotechnology 2014, 9, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, B.; Shi, L.; et al. Thermophotovoltaic cells for solar energy harvesting. Nano Energy 2017, 34, 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, N.N.; Fenning, D.P. Nanophotonic designs for solar thermophotovoltaics. Nano Convergence 2017, 4, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Feng, Z.; Chen, H.; et al. A review on thermophotovoltaic energy conversion using nanoscale emitters and absorbers. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 7641–7659. [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M.A.A.; Sarkar, M.R.; Parvez, M.; et al. Determining the optimum tilt angle and orientation for photovoltaic (PV) systems in Bangladesh. Optimum tilt angle 2017, 11, 4522. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoof, C. Micro power generators for ambient intelligence. Microelectronics Journal 2003, 34, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Sadek, A.Z.; Ribeiro, R.S.A.; Neves, R.M.; et al. Design and optimization of a solar thermoelectric generator for energy harvesting applications. Energy Conversion and Management 2017, 150, 680–692. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Arora, G. Solar thermoelectric energy conversion: A study on optimization of system efficiency. Energy Conversion and Management 2014, 77, 555–564. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, H.P.; Mohamad, M.I.; Sopian, K.; et al. Design and performance optimization of a solar thermoelectric generator. Energy Procedia 2015, 68, 370–379. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Zaidi, M.A.; Ali, A.; et al. Development of a solar thermoelectric generator for energy harvesting applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 74, 867–878. [Google Scholar]

- Alqarni, H.A.; Prasher, R. Enhanced heat transfer for solar thermoelectric generators using nanofluids. Solar Energy 2019, 177, 302–308. [Google Scholar]

- Alqarni, H.A.; Prasher, R. Performance improvement of solar thermoelectric generators using phase change materials. Applied Energy 2018, 225, 953–961. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.A.; Rowe, D.M. A review of thermoelectric cooling: Materials, modeling, and applications. Applied Thermal Engineering 2003, 23, 371–392. [Google Scholar]

- Lizardi, J.M.; Zanón, R.; Vásquez-Arenas, A.; et al. Analysis of thermoelectric cooling systems for photovoltaic panels. Solar Energy 2018, 171, 114–122. [Google Scholar]

- Khazaee, A.; Ghahremani-Ghajar, A.A. Performance analysis of a thermoelectric cooling system for photovoltaic modules. Renewable Energy 2016, 94, 492–499. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, G.J.; Toberer, E.S. Complex thermoelectric materials. Nature Materials 2008, 7, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, T.J.; Canfield, J.L. Photovoltaic materials, devices, and systems based on CdTe. Annual Review of Materials Research 2003, 33, 295–326. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, D.M. Recent developments in thermoelectric refrigeration. Applied Thermal Engineering 2003, 23, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar]

- Shakeri, A.; Hajabdollahi, H. Thermoelectric cooling of solar photovoltaic panels: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 70, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, M.I.; Sopian, K.; Yatim, B.; et al. Performance of a solar thermoelectric generator for small-scale applications. Energy Procedia 201, 75, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

| Dimensions | 40mm x 40mm x 3.4mm |

| Lead Length | 300mm |

| Thermal conductivity (λ) | 15~16x10-3W/Celsius.cm |

| ZT | 1.2 |

| Temperature electromotive force (a) | >190 |

| Conductivity | 850~1250Ω |

| Dimensions of generator | 40mm x 40mm x 3.8mm |

| Lead Length | 200mm |

| ZT | 1.4 |

| Locations | Latitude Angle | Tilt Angle |

|---|---|---|

| Cox’s bazar | 21.44° | 26° |

| Chittagong | 22.35° | 25° |

| Jessore | 23.16° | 25° |

| Dhaka | 23.81° | 30° |

| Ishurdi | 24.13° | 27° |

| Bogra | 24.84° | 27° |

| Sylhet | 24.9° | 28° |

| Rangpur | 25.75° | 29° |

| Temperature Differential (℃) | 20 | 40 | 60 | 80 | 100 |

| Open Circuit Output Voltage (V) | 0.97 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 4.8 |

| Short Circuit Output Current (mA) | 225 | 368 | 469 | 558 | 669 |

| Temperature Differential (℃) | 20 | 40 | 60 | 80 | 100 |

| Open Circuit Output Voltage (V) | 0.88 | 1.56 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 4.5 |

| Short Circuit Output Current (mA) | 202 | 331 | 427 | 542 | 644 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).