Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Sustainable Energy Transition: Overcoming Fossil Fuel Challenges

1.2. Exploring Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC): Principles, Research, and Applications

1.3. Advancing OTEC Efficiency: Integrating Thermoelectric Generators

1.4. Optimizing Thermoelectric Generators: From Material Innovations to Seawater Efficiency Analysis

2. Numerical Methods

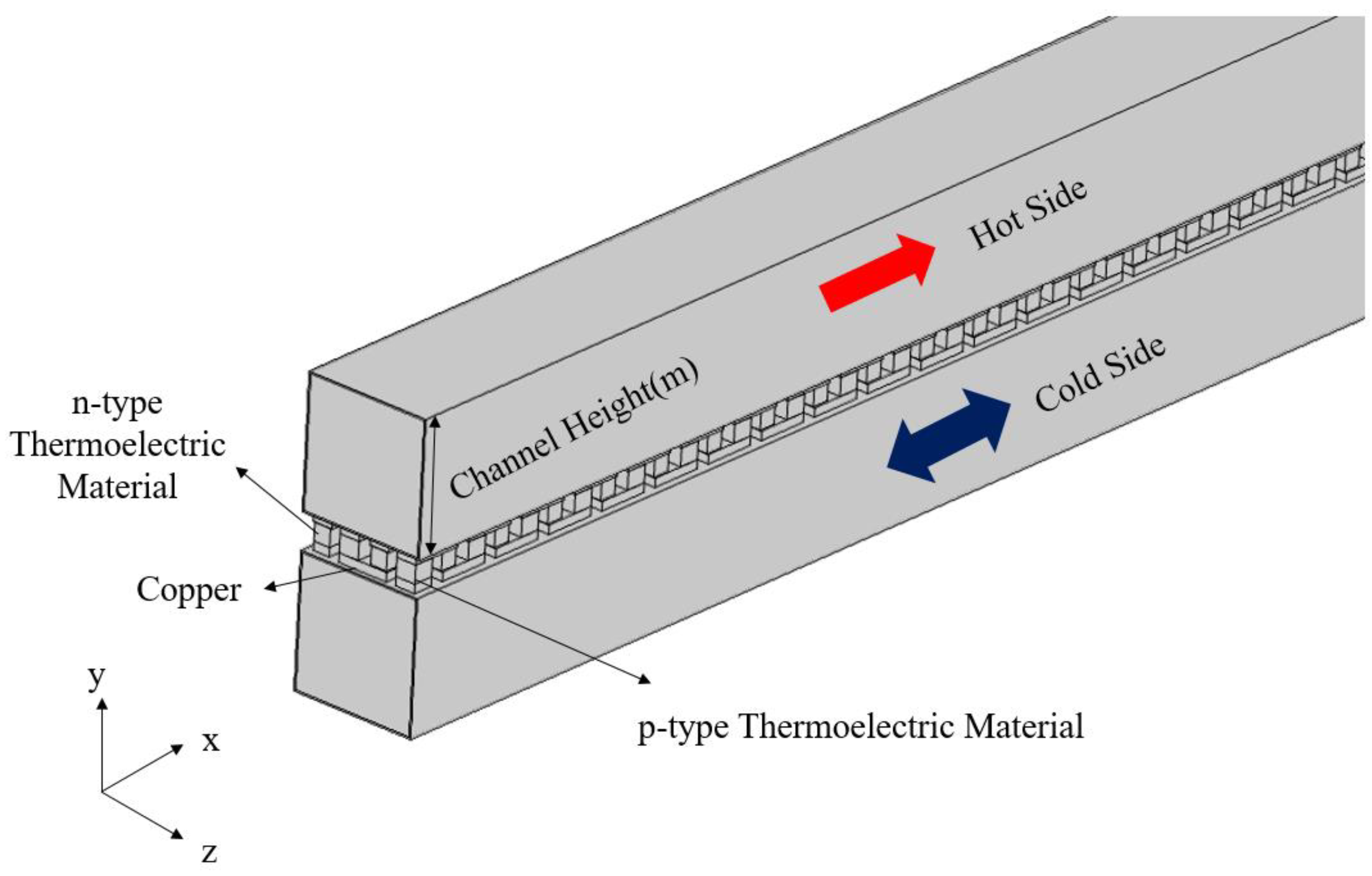

2.1. Modeling and Simulation of TEG for OTEC: Design and Material Configuration

2.2. Governing Equations and Assumptions for Thermoelectric System Simulation

- The fluid in the input channel is steady, fully developed, and incompressible.

- The flow channel is thermally insulated, with radiation and convection effects around the channel being disregarded.

- The electrical and thermal resistances at the contact surfaces of the TEG materials are neglected.

- Thermal losses between the heat exchanger and the thermoelectric module are ignored.

- The fluid-solid interface is considered a no-slip boundary.

- Within the TEG module, the leads of the first set of thermocouples are grounded, while all other boundaries of the TEG are set as electrically insulated.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Effects of Reynolds Number and Channel Height on TEG Performance in OTEC Systems

3.2. Analyzing Pump Power and Channel Dimensions in Thermoelectric System Efficiency

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Thermoelectric Materials and Their Impact on Performance

3.4. Impact of Temperature Differential on Power Output and Efficiency in Thermoelectric Systems

3.5. Simulation Results and Performance Analysis of TEGs in OTEC Applications

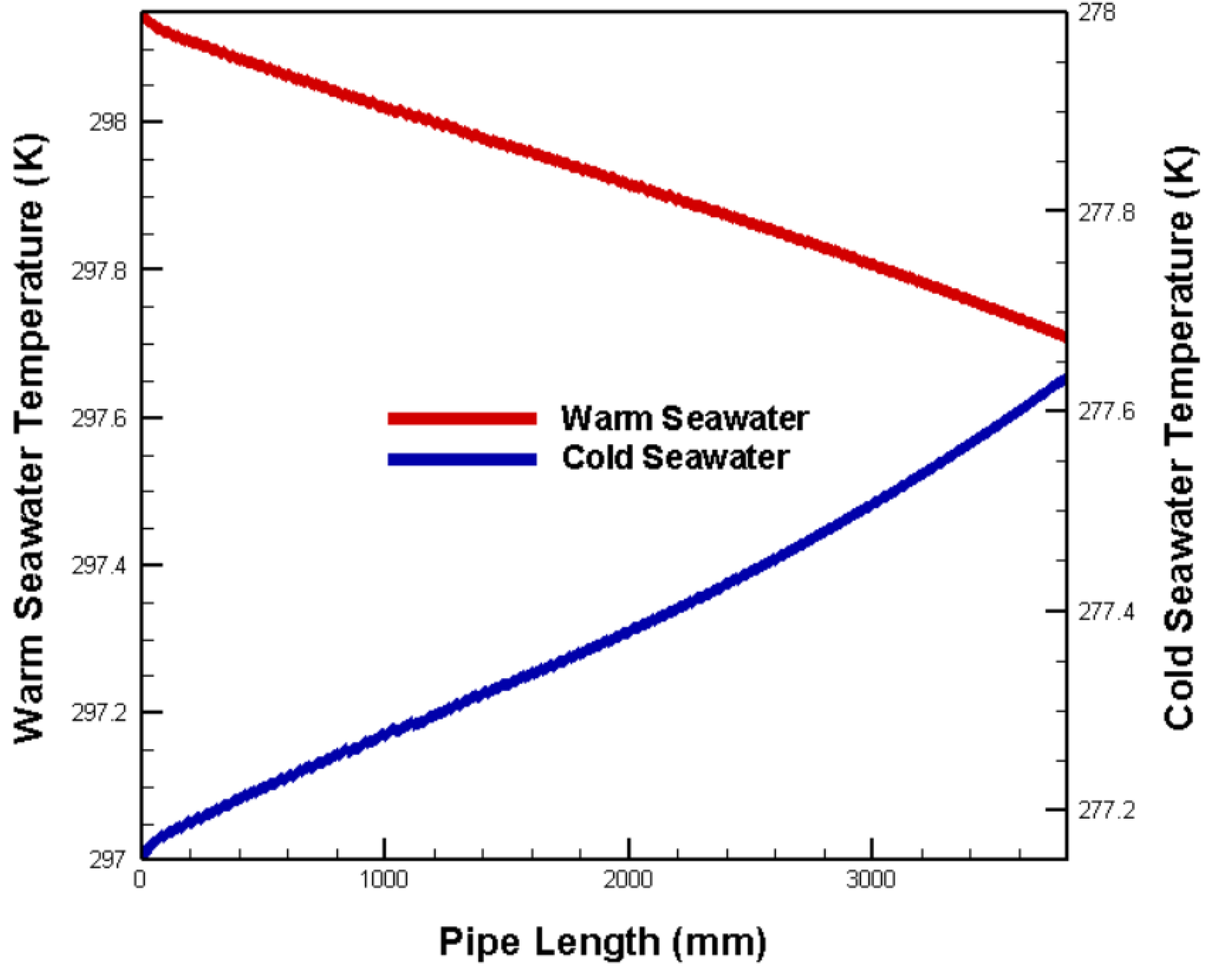

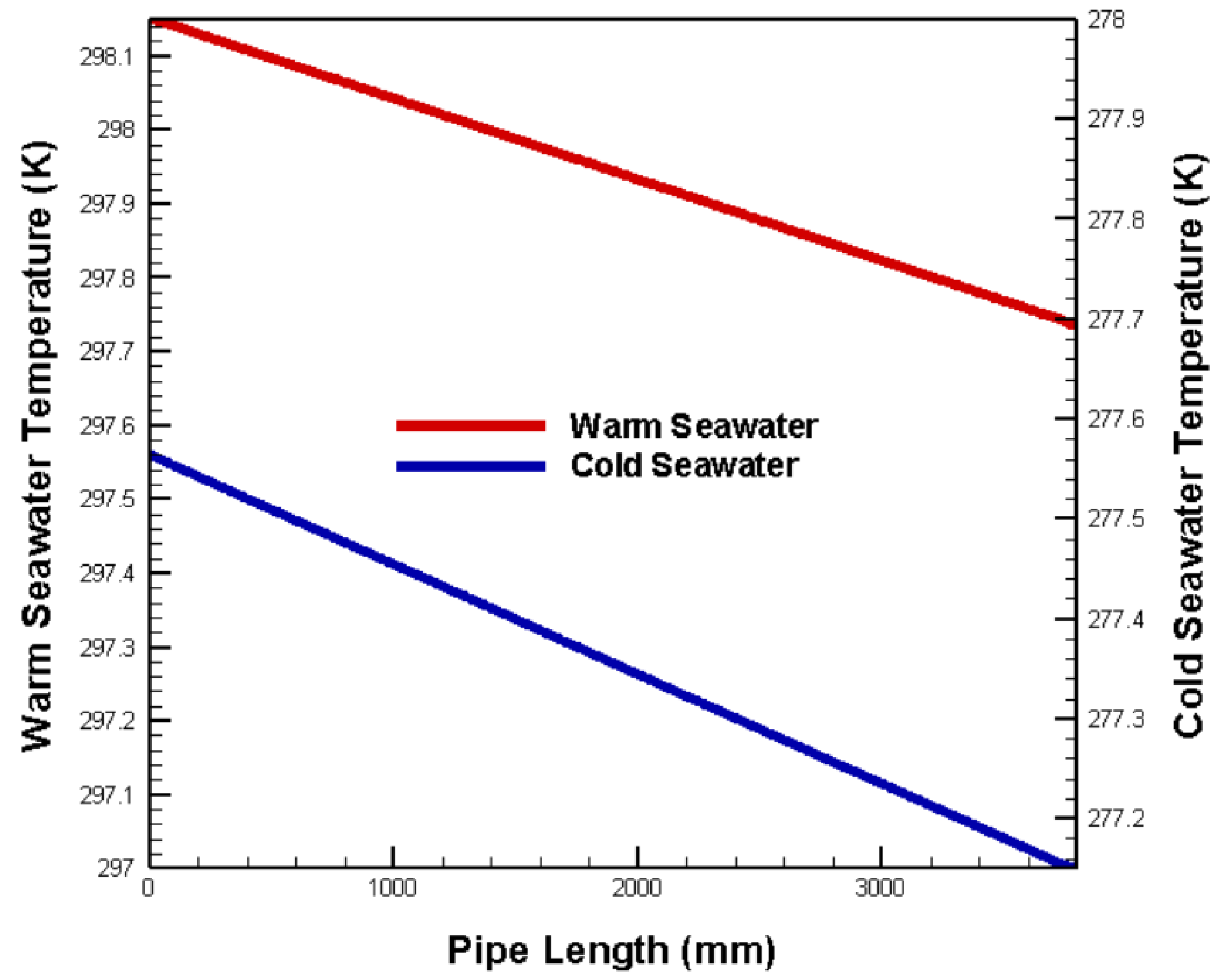

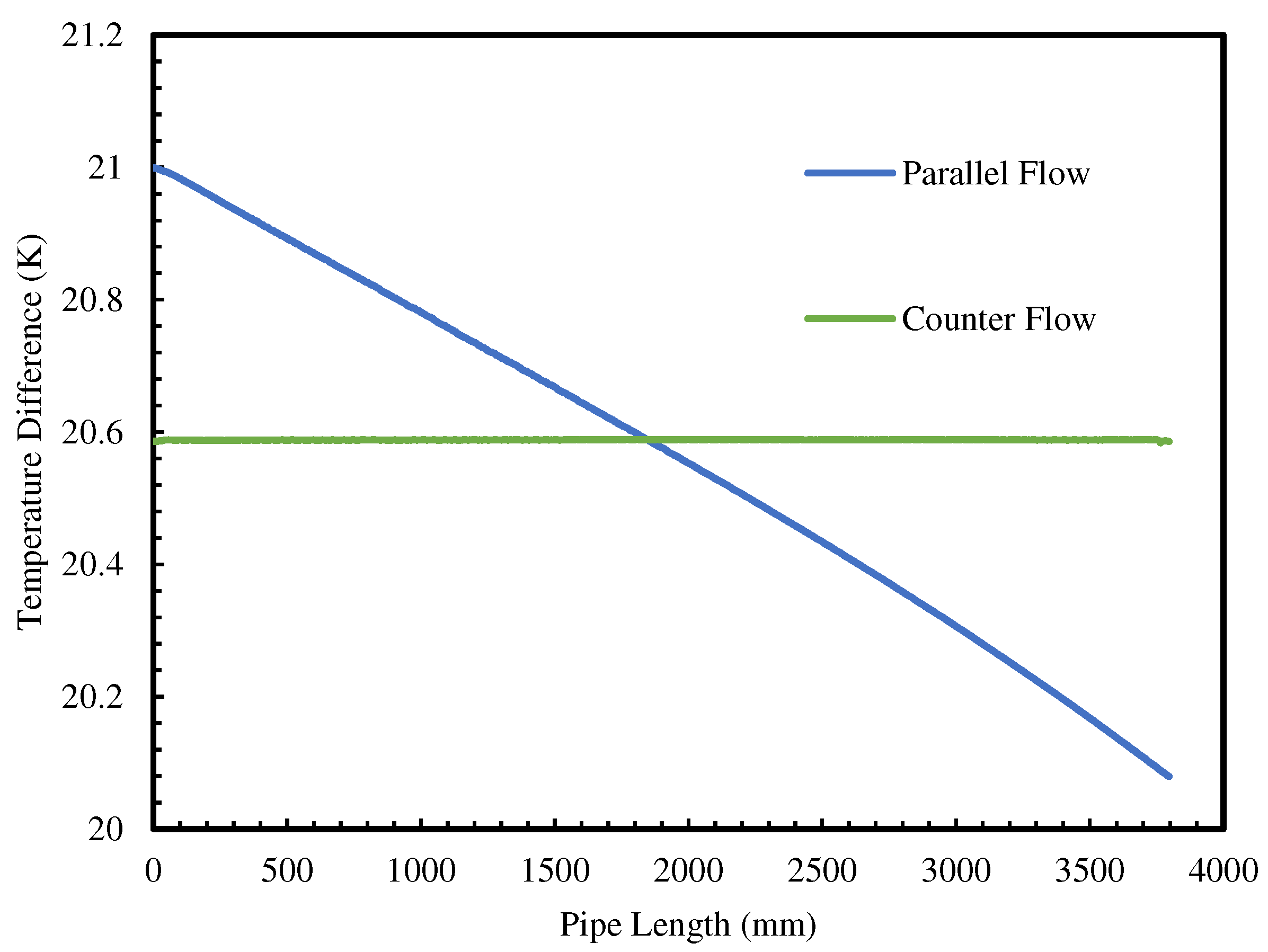

- When surface warm seawater and deep cold seawater flow through the channels at fixed temperatures and velocities, the temperature change is nearly linear, indicating stable heat exchange between the fluid and TEG.

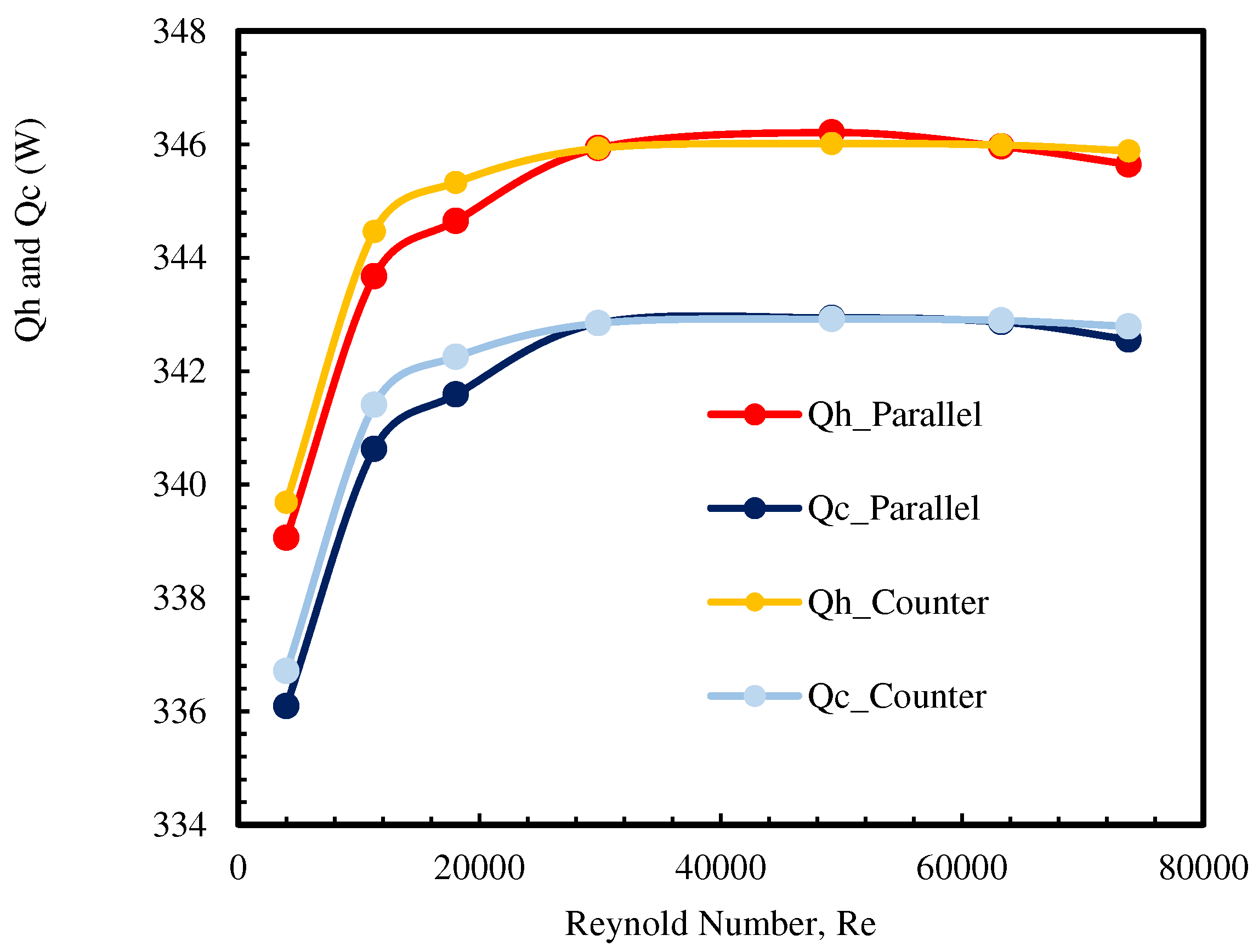

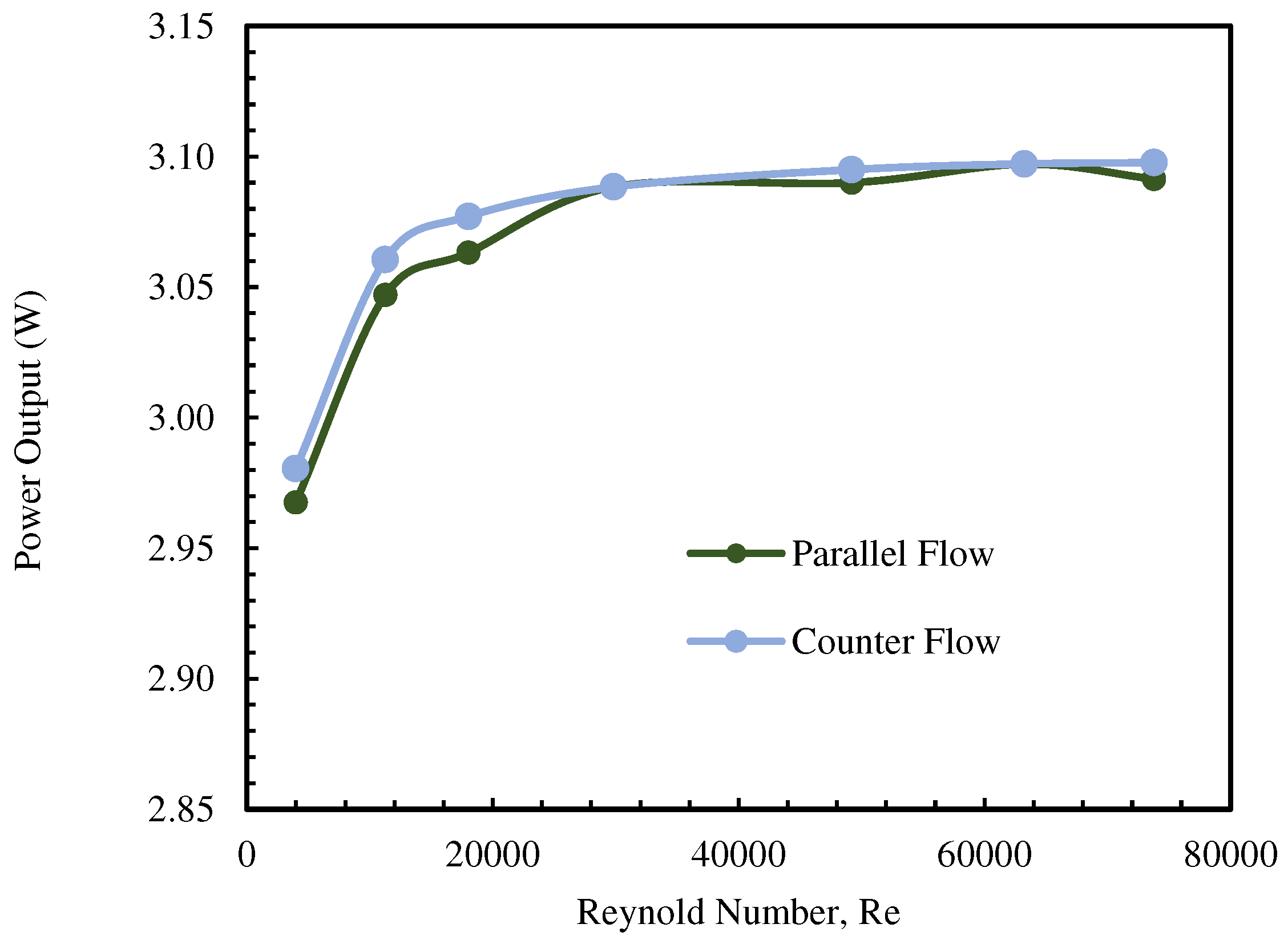

- In both parallel and counter flows models, when the Reynolds number (Re) is less than 12000, the warm surface and cold deep seawater provide lower heat to the TEG. Conversely, at Re>12000, they provide sufficient and stable heat.

- In the parallel flows, as the Reynolds number increases and sufficient thermal energy is provided to the TEG, the output power also increases, stabilizing at 3.01 W for Re>12000.

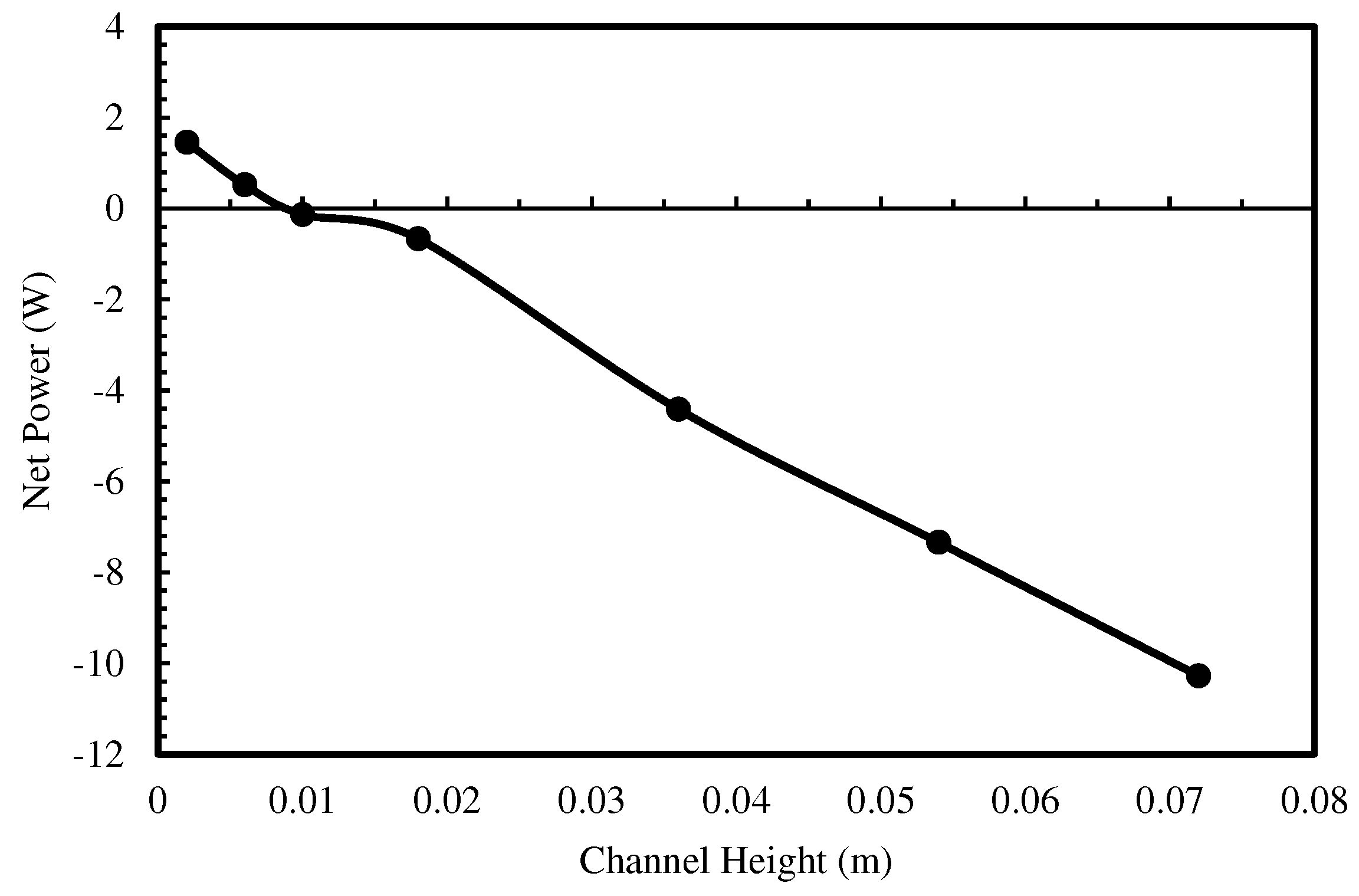

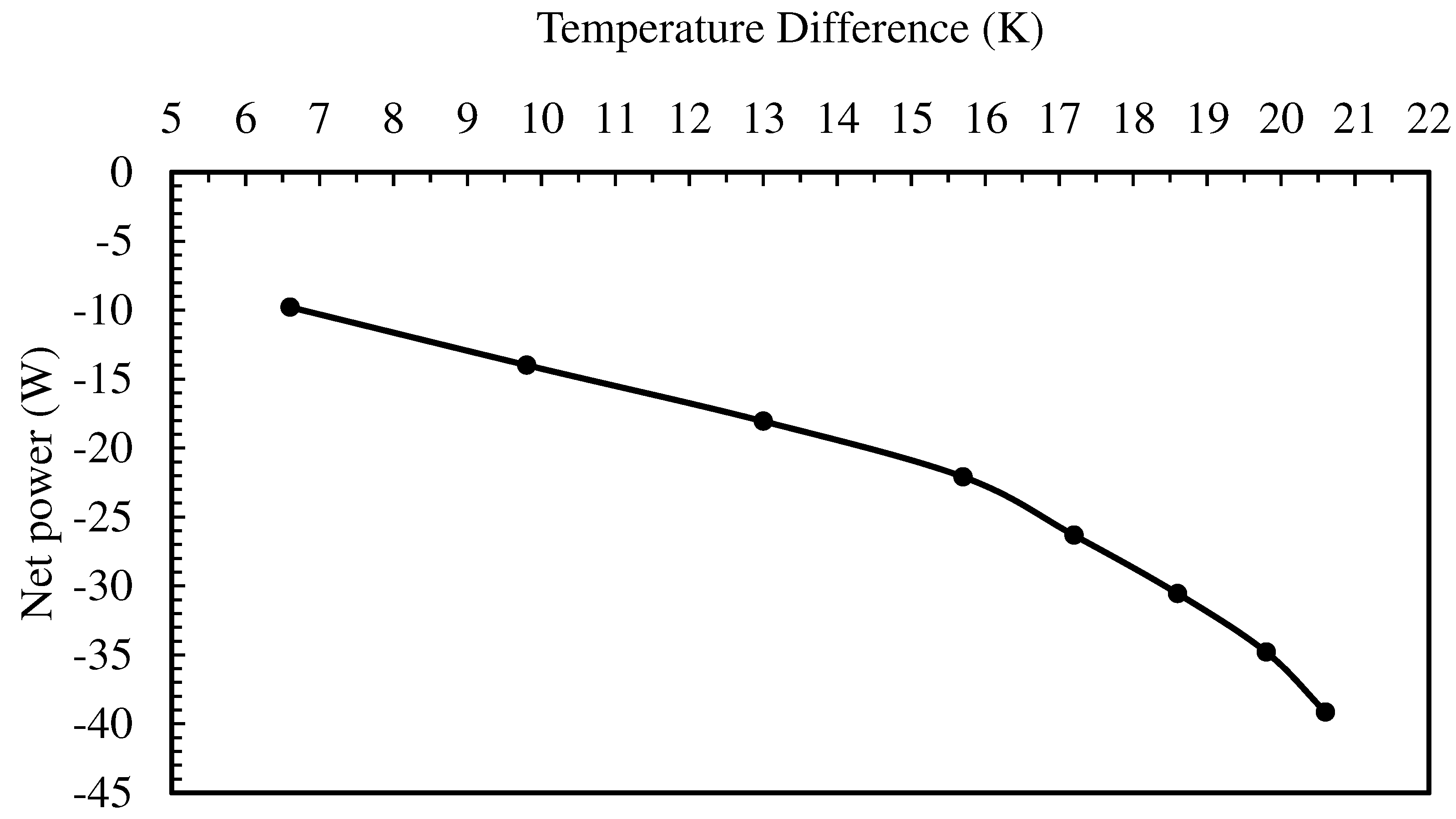

- Although higher channel heights yield better TEG output power, the highest net power, considering pump consumption, occurs at a channel height of D = 0.002 m due to the lowest fluid flow and, consequently, the lowest pump consumption. Net power becomes negative when channel height exceeds 0.01 m.

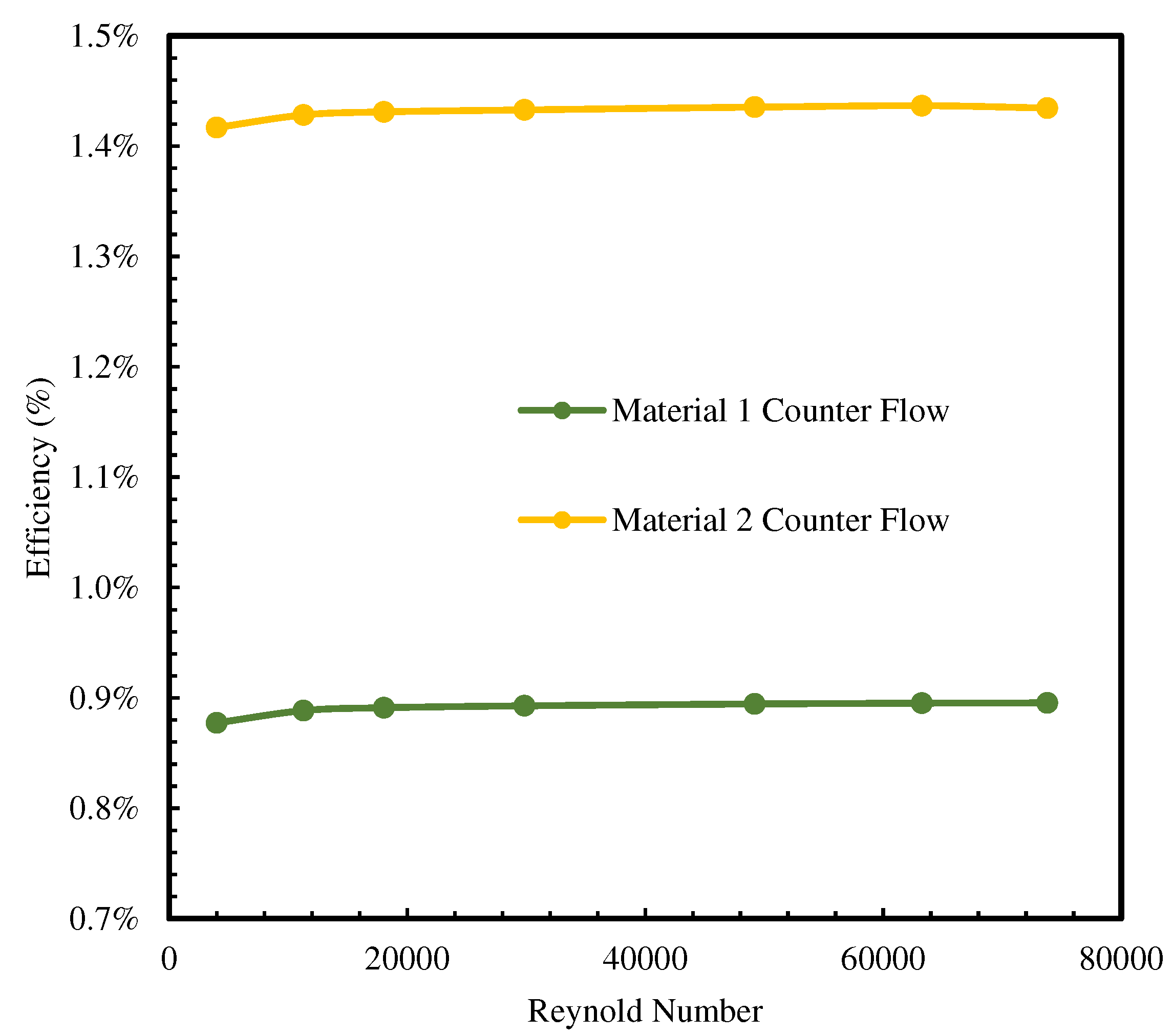

- Comparing two different thermoelectric materials, it was found that materials with higher electrical conductivity and lower thermal conductivity exhibit superior thermoelectric performance, resulting in higher output power, in both parallel and counter models.

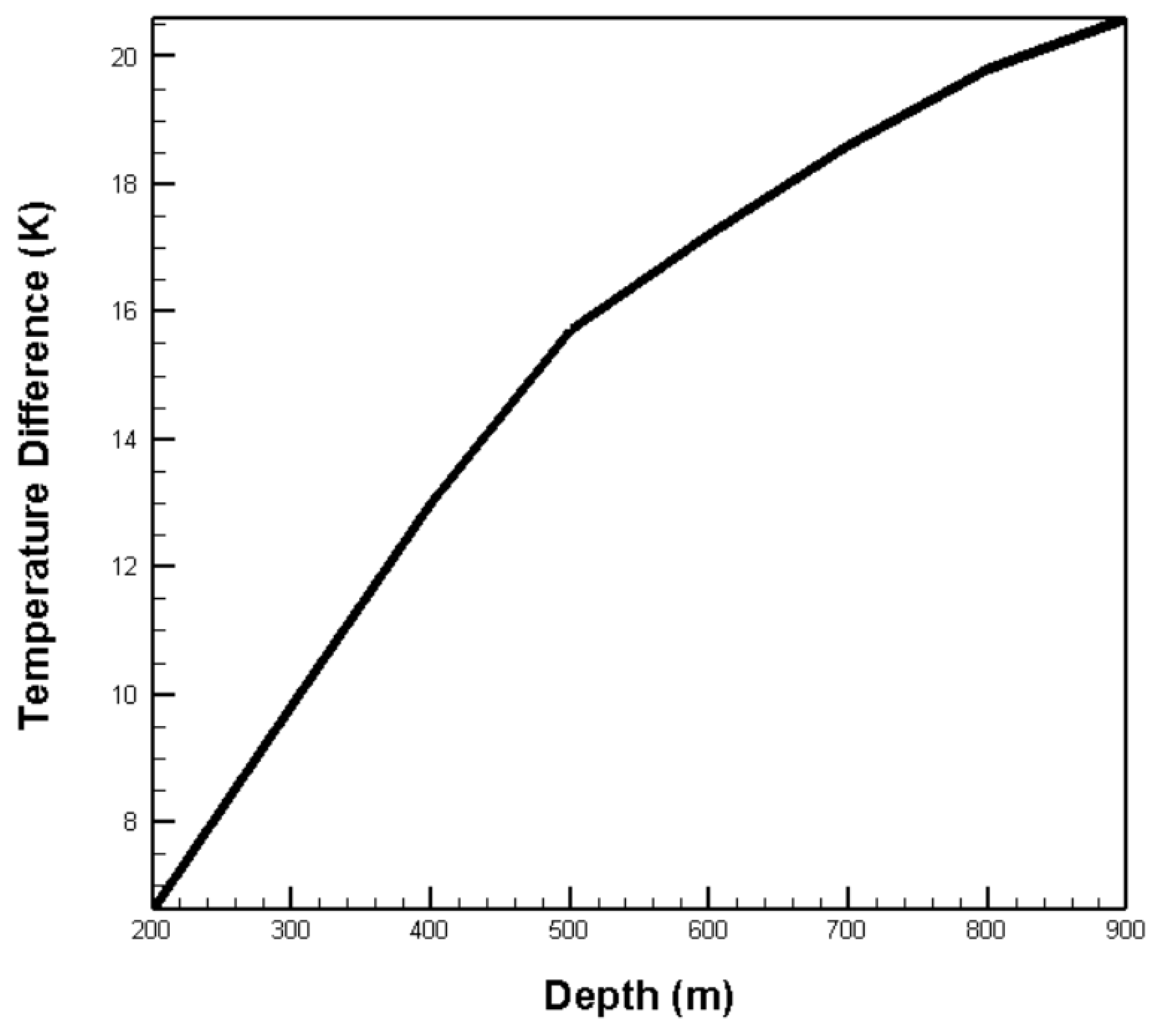

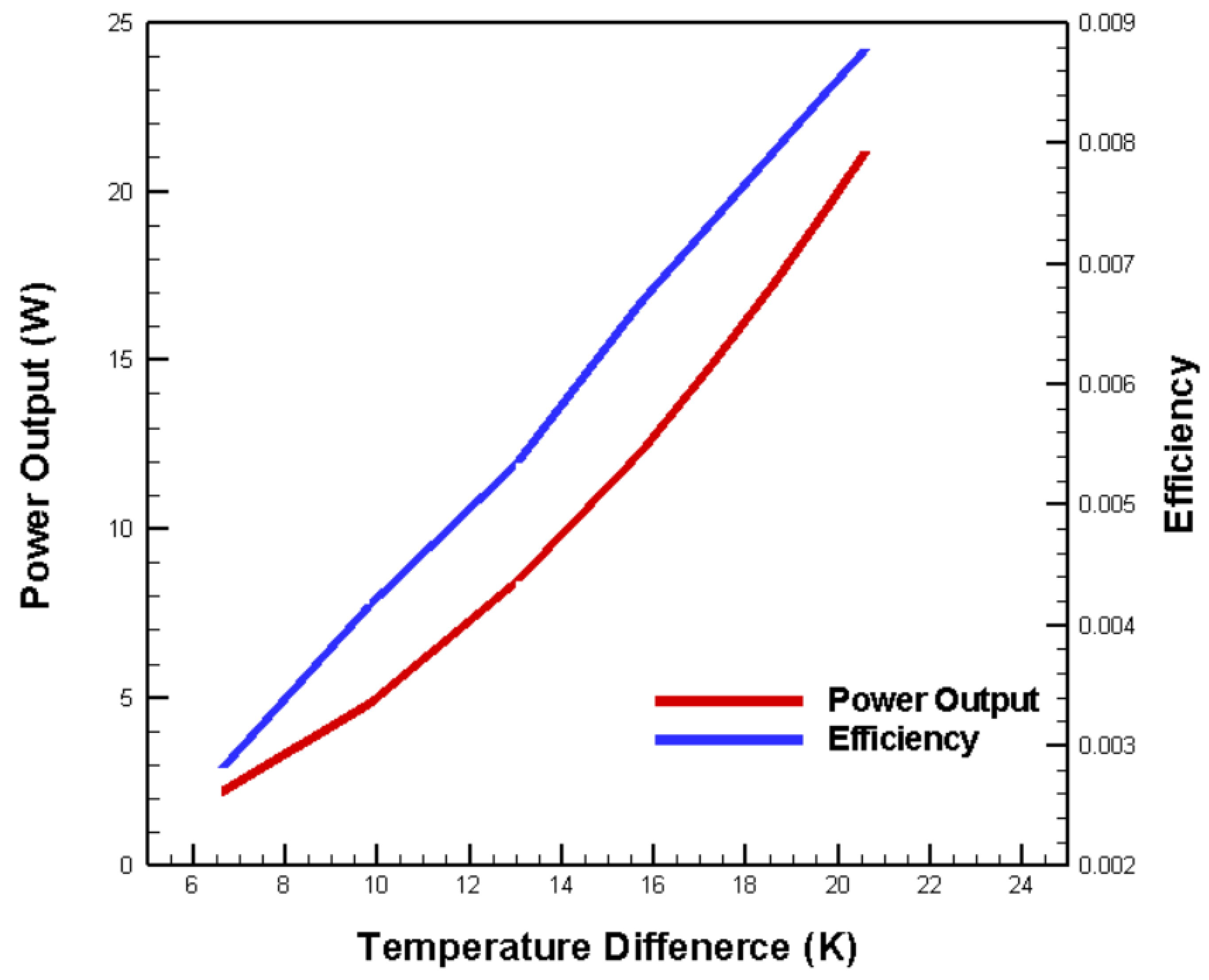

- Keeping the surface warm seawater temperature constant and varying the cold end temperature at different depths showed that the open-circuit voltage of the TEG increases with the temperature difference, thereby increasing both output power and conversion efficiency.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keles, S., Fossil Energy Sources, Climate Change, and Alternative Solutions. Energy Sources Part a-Recovery Utilization and Environmental Effects, 2011. 33(12): p. 1184-1195.

- Abbasi, T., M. Premalatha, and S.A. Abbasi, The return to renewables: Will it help in global warming control? Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2011. 15: p. 891-894.

- Abolhosseini, S., A. Heshmati, and J. Altmann, A Review of Renewable Energy Supply and Energy Efficiency Technologies. Sustainable Technology eJournal, 2014.

- Şen, Z., Solar energy in progress and future research trends. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 2004. 30: p. 367-416.

- Rosen, M.A., Combating global warming via non-fossil fuel energy options. International Journal of Global Warming, 2009. 1: p. 2. [CrossRef]

- Klugmann-Radziemska, E. Environmental Impacts of Renewable Energy Technologies. 2014.

- Elavarasan, R.M., The Motivation for Renewable Energy and its Comparison with Other Energy Sources: A Review. European Journal of Sustainable Development Research, 2019.

- Bombarda, P.A., C.M. Invernizzi, and M. Gaia, Performance Analysis of OTEC Plants With Multilevel Organic Rankine Cycle and Solar Hybridization. Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power-transactions of The ASME, 2013. 135: p. 042302. [CrossRef]

- Gritton, E.C., et al. Quantitative evaluation of closed-cycle Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) technology in central station applications. 1980.

- Kamogawa, H., OTEC research in Japan. Energy, 1980. 5: p. 481-492. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, N., A. Hoshi, and Y. Ikegami. Thermal Efficiency Enhancement of Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) Using Solar Thermal Energy. 2006.

- Cavrot, D., Economics of Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC). Renewable Energy, 1993. 3: p. 891-896. [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, M.R.M. and R. Abraham, The Indian 1 MW Demonstration OTEC Plant and the Pre-Commissioning Tests. Marine Technology Society Journal, 2002. 36: p. 36-41. [CrossRef]

- Burmistrov, I.N., et al., Advances in Thermo-Electrochemical (TEC) Cell Performances for Harvesting Low-Grade Heat Energy: A Review. Sustainability, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pourkiaei, S.M., et al., Thermoelectric cooler and thermoelectric generator devices: A review of present and potential applications, modeling and materials. Energy, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Dogra, S. and N. Chauhan. A Review on various ocean thermal energy conversion systems (OTEC). 2021.

- Chopra, K.N., Ocean Energy Thermal Conversion (OTEC) and Its Mathematical Modeling-A Short Technical Note. Invertis Journal of Renewable Energy, 2013. 3: p. 222-229.

- Zheng, X., et al., A review of thermoelectrics research – Recent developments and potentials for sustainable and renewable energy applications. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2014. 32: p. 486-503. [CrossRef]

- Kishore, D.R. and T.J. Prasnnamba, An application of OTEC principle to thermal power plant as a co-generation plant. 2017 2nd International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), 2017: p. 992-995.

- Wood, C., Materials for thermoelectric energy conversion. Reports on Progress in Physics, 1988. 51: p. 459-539. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L., et al., Steady State Performance Analysis of OTEC Organic Rankine Cycle System. 2023 5th Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium (AEEES), 2023: p. 1563-1567.

- Bohn, M., D. Benson, and T. Jayadev, Thermoelectric ocean thermal energy conversion. 1980. [CrossRef]

- Anatychuk, L. and V. Polyak, Computer design of thermoelectric OTEC. Journal of thermoelectricity, 2015(2): p. 34-44.

- Yu, J. and H. Zhao, A numerical model for thermoelectric generator with the parallel-plate heat exchanger. Journal of Power Sources, 2007. 172(1): p. 428-434. [CrossRef]

- Niu, X., J. Yu, and S. Wang, Experimental study on low-temperature waste heat thermoelectric generator. Journal of Power Sources, 2009. 188(2): p. 621-626. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q., et al., Comprehensive insight into p-type Bi2Te3-based thermoelectrics near room temperature. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2022. 14(44): p. 49425-49445.

- Hong, M., Z.-G. Chen, and J. Zou, Fundamental and progress of Bi2Te3-based thermoelectric materials. Chinese Physics B, 2018. 27(4): p. 048403.

- Lu, X. and D.T. Morelli, Natural Mineral Tetrahedrite as a Direct Source of Thermoelectric Materials. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2013. 15: p. 5762. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., et al., n-Bi2–x Sb x Te3: A Promising Alternative to Mainstream Thermoelectric Material n-Bi2Te3–x Se x near Room Temperature. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2020. 12(28): p. 31619-31627.

- Tang, X., et al., A comprehensive review on Bi2Te3-based thin films: thermoelectrics and beyond. Interdisciplinary Materials, 2022. 1(1): p. 88-115.

- Shu, R., et al., Mg3+ δSbxBi2− x Family: A Promising Substitute for the State-of-the-Art n-Type Thermoelectric Materials near Room Temperature. Advanced Functional Materials, 2019. 29(4): p. 1807235.

- Wang, S., et al., Enhanced thermoelectric properties of Bi 2 (Te 1− x Se x) 3-based compounds as n-type legs for low-temperature power generation. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 2012. 22(39): p. 20943-20951.

- Wu, C., Specific power analysis of thermoelectric OTEC plants. Ocean engineering, 1993. 20(4): p. 433-442. [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Y. and T. Oh, Thermoelectric properties of p-type (Bi, Sb) 2Te3 nanocomposites dispersed with multiwall carbon nanotubes. Materials Research Bulletin, 2014. 58: p. 54-58.

- Tan, M., Y. Hao, and G. Wang, Improvement of thermoelectric properties induced by uniquely ordered lattice field in Bi2Se0. 5Te2. 5 pillar array. Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 2014. 215: p. 219-224. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, W.-L., Simulation design of ocean thermoelectric power generation system, in Mechanical and Mechatronic Engineering. 2021, National Taiwan Ocean University. p. 76.

- Yan, S.-R., et al., Performance and profit analysis of thermoelectric power generators mounted on channels with different cross-sectional shapes. Applied Thermal Engineering, 2020. 176: p. 115455.

- Ma, T., et al., Numerical study on thermoelectric–hydraulic performance of a thermoelectric power generator with a plate-fin heat exchanger with longitudinal vortex generators. Applied Energy, 2017. 185: p. 1343-1354. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-H., S.-Q. Bai, and L.-D. Chen, Technologies and applications of thermoelectric devices: current status, challenges and prospects. 2019.

- Chen, W.-H., et al., A comprehensive analysis of the performance of thermoelectric generators with constant and variable properties. Applied energy, 2019. 241: p. 11-24. [CrossRef]

- Sandoz-Rosado, E.J., Investigation and development of advanced models of thermoelectric generators for power generation applications. 2009: Rochester Institute of Technology.

- APDRC LAS7 for public. 2021 [cited 2021 2021/6/30]; Available from: http://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu/las/v6/constrain?var=11412.

| Channel Height (m) | Hydraulic Diameter (m) | Reynold Number |

|---|---|---|

| 0.002 | 3.89×10-3 | 3987 |

| 0.006 | 1.11×10-2 | 11275 |

| 0.010 | 1.76×10-2 | 18040 |

| 0.018 | 2.91×10-2 | 29848 |

| 0.036 | 4.8×10-2 | 49200 |

| 0.054 | 6.17×10-2 | 63253 |

| 0.072 | 7.2×10-2 | 73800 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).