Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Method

2.1. Materials

2.2. SEM Characterization

2.3. Hydrolyzed Keratin Permeability Test

2.4. Tensile Tests

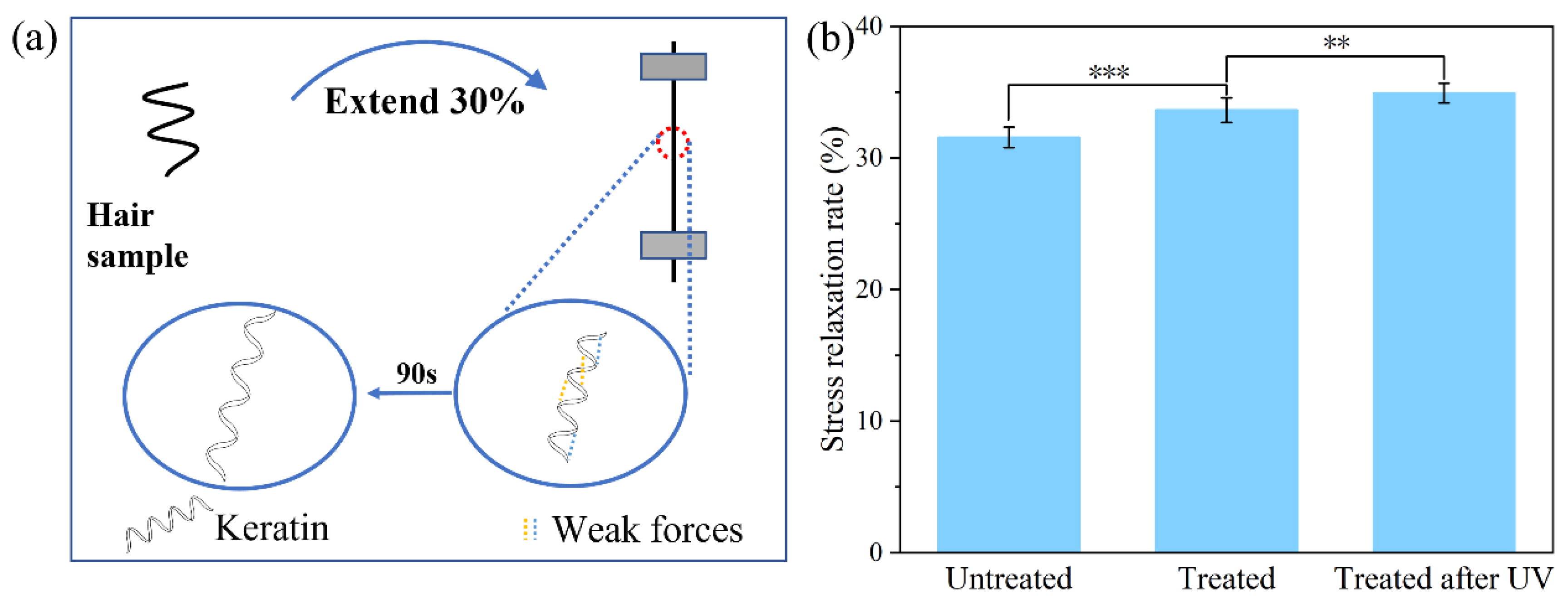

2.5. Stress Relaxation

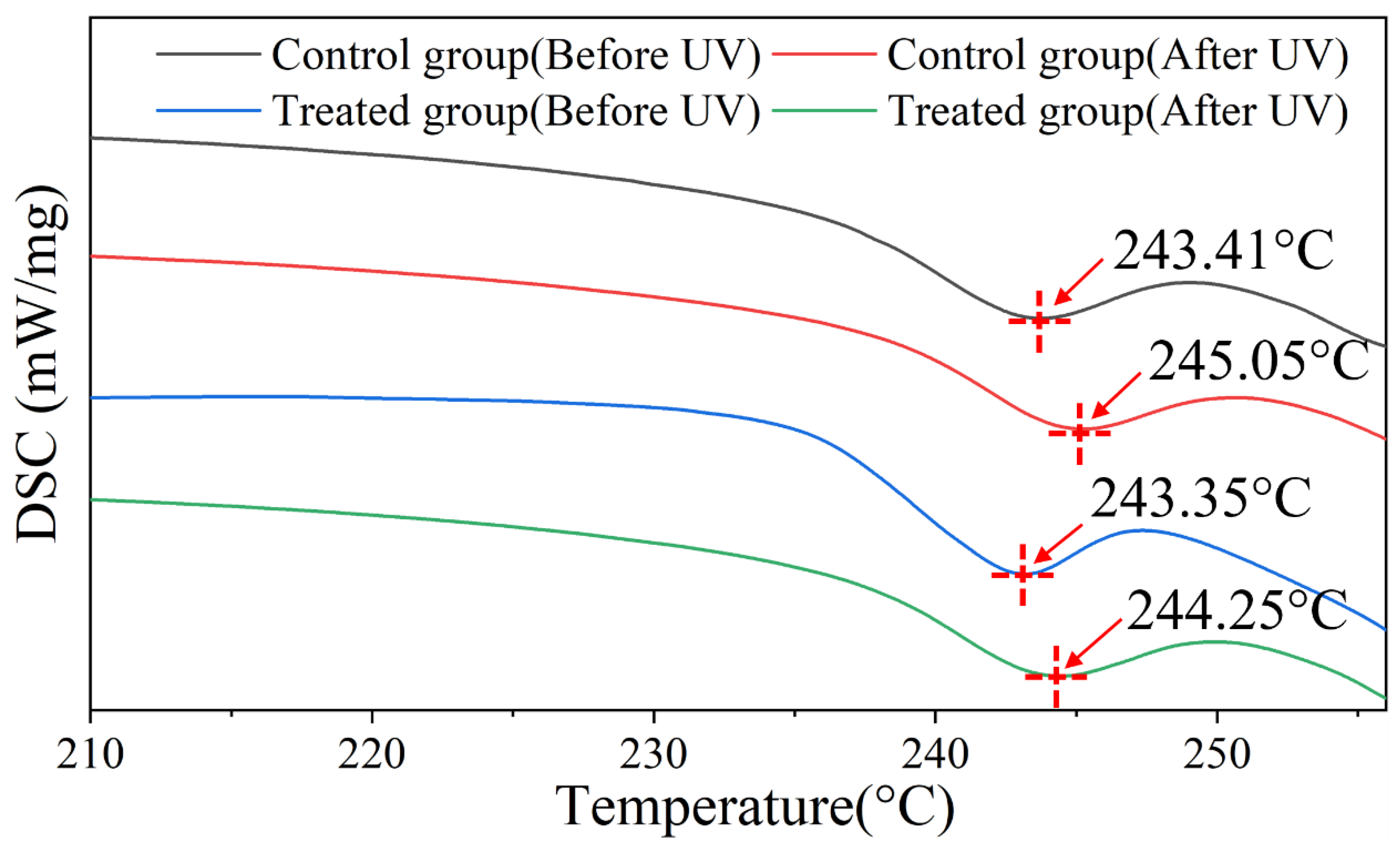

2.6. DSC

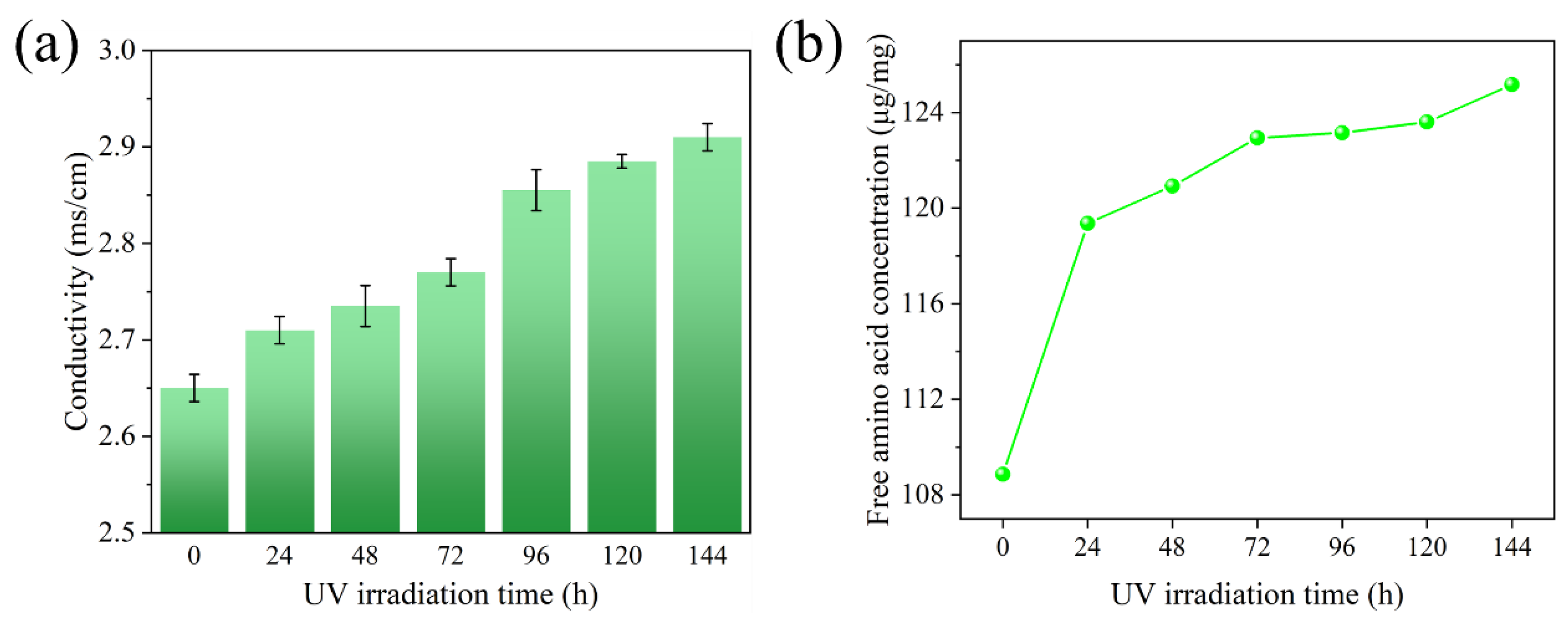

2.7. Hydrolyzed Keratin Degradation Experiment

3. Result and Discussion

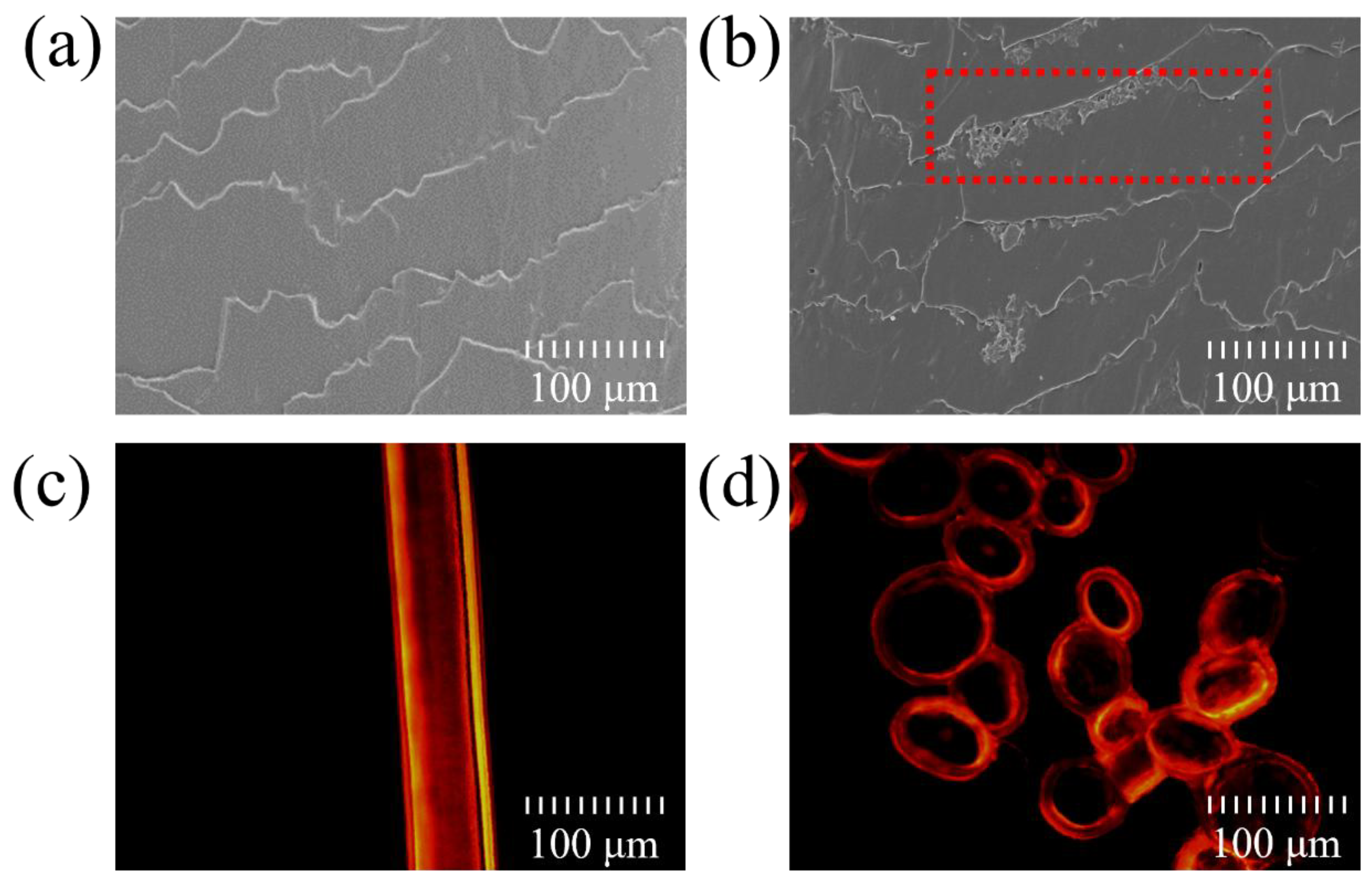

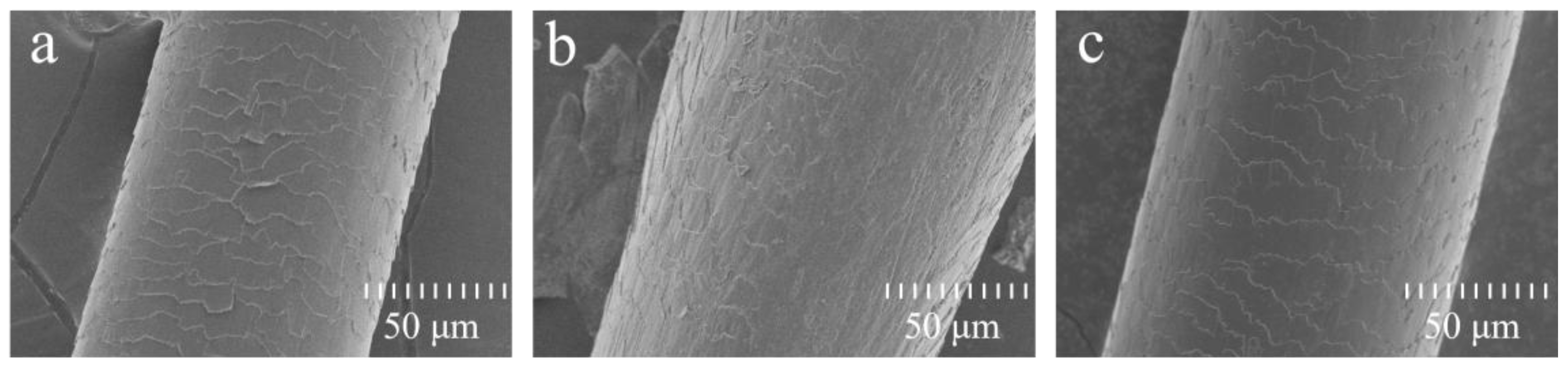

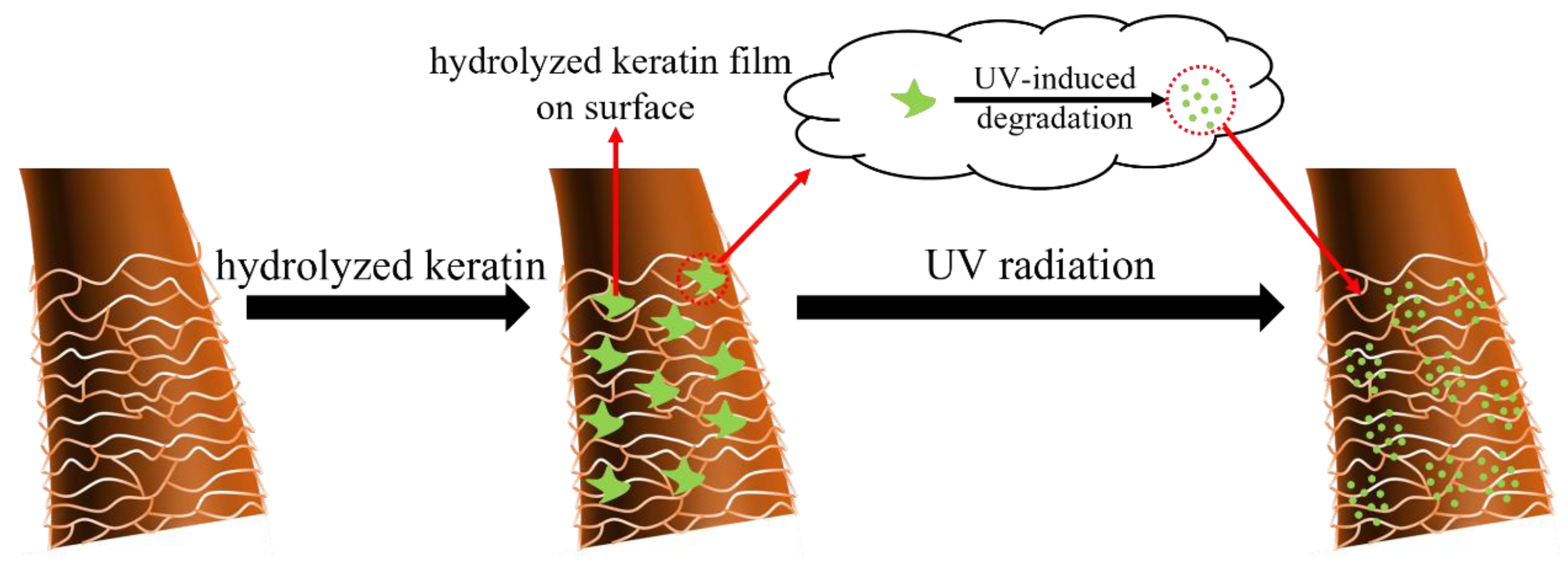

3.1. Deposition and Penetration Behavior of Hydrolyzed Keratin

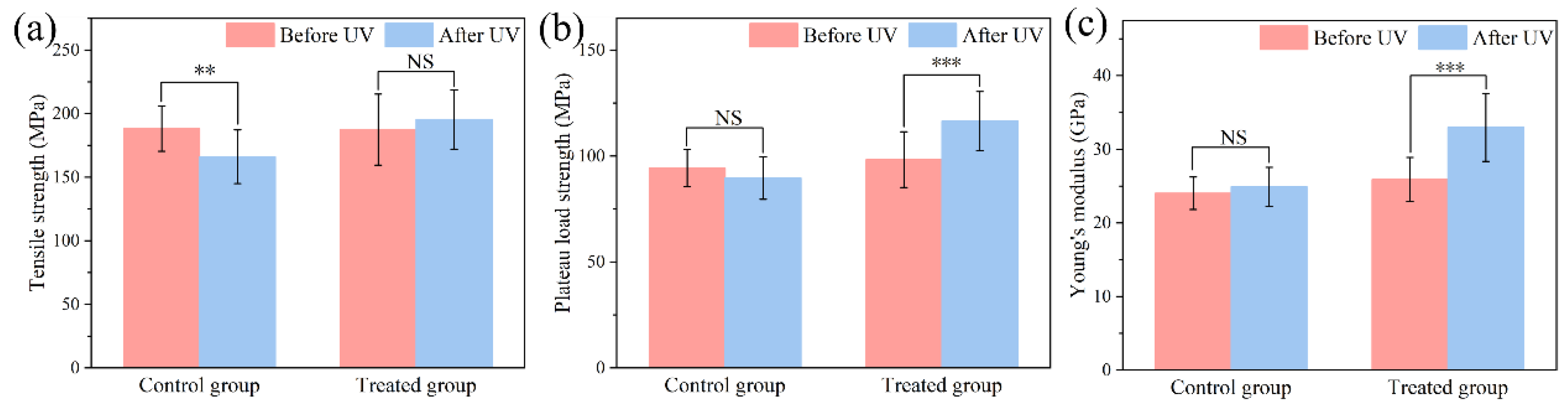

3.2. UV Protection Performance of Hydrolyzed Keratin

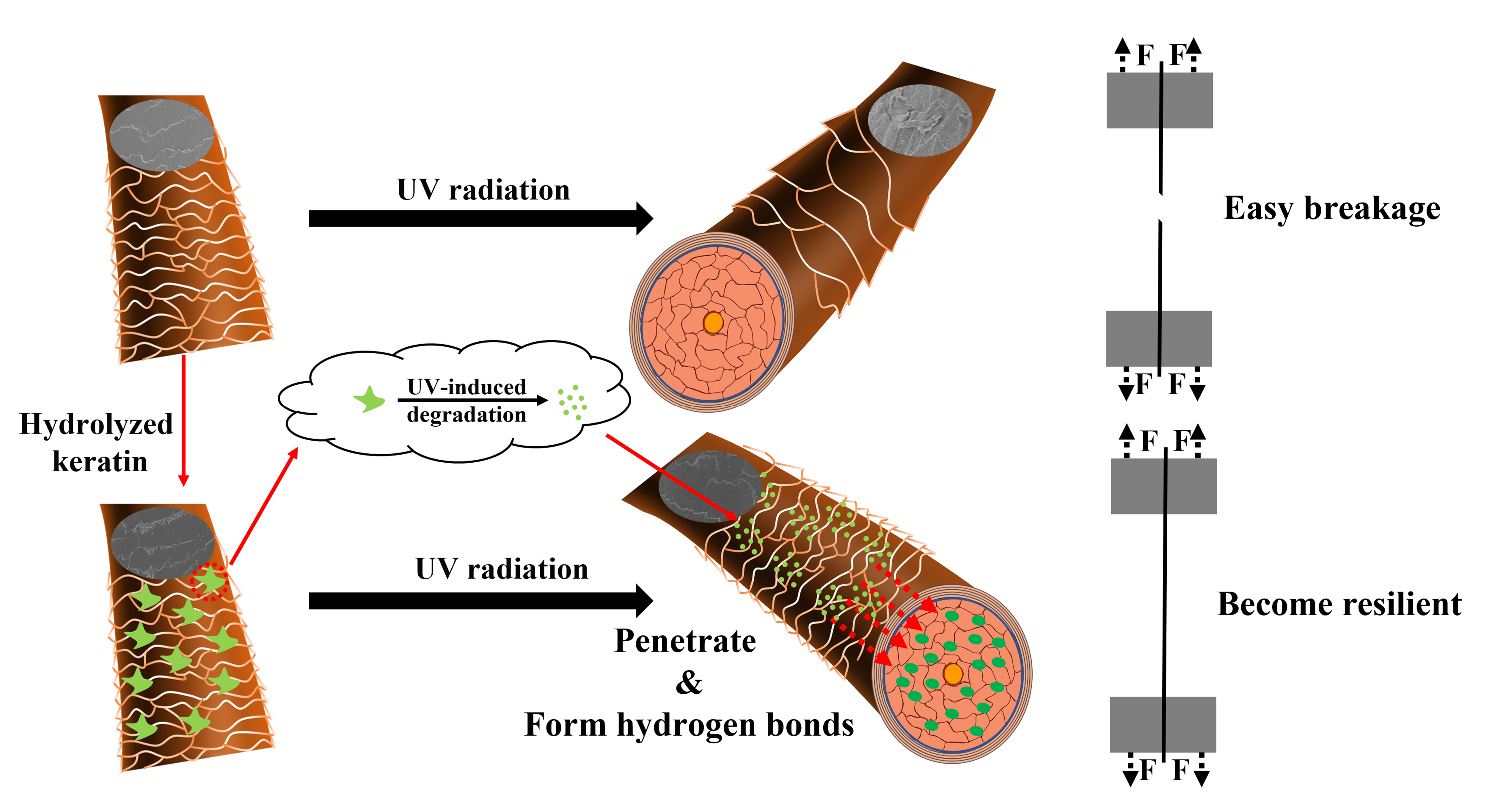

3.3. Mechanism Investigation

4. Conclusions

References

- Nogueira, A. C. S.; Nakano, A. K.; Joekes, I. Impairment of hair mechanical properties by sun exposure and bleaching treatments. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2004, 55, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Imai, T. The influence of hair bleach on the ultrastructure of human hair with special reference to hair damage. Okajimas Folia Anat. Jpn. 2011, 88, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, J. M.; Bell, F.; Koehn, H.; et al. Redox proteomic evaluation of bleaching and alkali damage in human hair. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2013, 35, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, F.; Ermolenkov, A.; Kurouski, D. Infrared analysis of hair dyeing and bleaching history. Anal. Methods 2020, 12, 3741–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J. W. Analysis of Morphological changes on the hair surface by heat perm treatment method. J. Korean Soc. Cosmetol. 2023, 2023 29, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, R. M.; Chen, J. Y.; Raman, C.; et al. Photo-neuro-immuno-endocrinology: How the ultraviolet radiation regulates the body, brain, and immune system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2024, 121, e2308374121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estibalitz, F.; Barba, C.; Alonso, C.; et al. Photodamage determination of human hair. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2012, 106, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, C. R.; Bahl, M. K. Analysis of hair by electron spectroscopy for chemical analysis. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1984, 35, 379–390. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J. H.; Park, T. S.; Lee, H. J.; et al. The ethnic differences of the damage of hair and integral hair lipid after ultra violet radiation. Ann. Dermatol. 2013, 25, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoting, E.; Zimmermann, M.; Höcker, H. Photochemical alterations in human hair. II: Analysis of melanin. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1995, 46, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Richena, M.; Rezende, C. A. Effect of photodamage on the outermost cuticle layer of human hair. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2015, 153, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smart, K. E.; Kilburn, M.; Schroeder, M.; et al. Copper and calcium uptake in colored hair. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2009, 60, 337–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, T.; Jolon, M.; Dyer, Santanu, D. ; et al. Trace metal ions in hair from frequent hair dyers in China and the associated effects on photo-oxidative damage. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2016, 156, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, K. R.; Marsh, J. M.; Godfrey, S.; et al. The role of chelants in controlling Cu(II)-induced radical chemistry in oxidative hair colouring products. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2013, 35, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelli, F. D.; André, R. B.; Maria, V. R. V. Effects of solar radiation on hair and photoprotection. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2015, 153, 240–246. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser, A. Silicones used in permanent and semi-permanent hair dyes to reduce the fading and color change process of dyed hair occurred by wash-out or UV radiation. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2004, 55 Suppl, S123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, C. M.; Albrecht, L.; Yang, B. Hair photoprotection by dyes. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2001, 52, 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, E.; Martínez-Teipel, B.; Armengol, R.; et al. Efficacy of antioxidants in human hair. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2012, 117, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelli, F. D.; Richard, P.; Jordana, R. C.; et al. Efficacy of Punica granatum L. hydroalcoholic extract on properties of dyed hair exposed to UVA radiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2013, 120, 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S. L.; Marsh, J. M.; Kelly, C. P.; et al. Protection of hair from damage induced by ultraviolet irradiation using tea (Camellia sinensis) extracts. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 2246–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahib, S.; Jungman, E. Aquis Hairsciences Inc. Composition for improving hair health. US2020/0069551A1.

- Cruz, C. F.; Azoia, N. G.; Matamá, T.; et al. Peptide-protein interactions within human hair keratins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinoco, A.; Gonçalves, J.; Silva, C.; et al. Keratin-based particles for protection and restoration of hair properties. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2018, 40, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, A.; Minamitake, Y.; Göpferich, A. Labelling peptides with fluorescent probes for incorporation into degradable polymers. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 1998, 45, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, E.; Cruz, C. F.; Azoia, N. G.; et al. Insights on the mechanical behavior of keratin fibrils. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 89, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, F. J.; Quadflieg, J. M.; Wortmann, G. Comparing hair tensile testing in the wet and the dry state: Possibilities and limitations for detecting changes of hair properties due to chemical and physical treatments. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2022, 44, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, C.; Scott, S.; Roddick-Lanzilotta, A.; et al. Restoring important hair properties with wool keratin proteins and peptides. Fibers Polym. 2010, 11, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C. R. R. de C.; Machado, L. D. B.; Velasco, M. V. R.; et al. DSC measurements applied to hair studies. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018, 132, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H. j.; Peng, L.; Jiang, W. C.; et al. Impact of solar ultraviolet radiation on daily outpatient visits of atopic dermatitis in Shanghai, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 18081–18088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernathy, D. G.; Spedding, G.; Starcher, B. Analysis of protein and total usable nitrogen in beer and wine using a microwell ninhydrin assay. J. Inst. Brew. 2009, 115, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinauskyte, E.; Shrestha, R.; Cornwell, P. A.; et al. Penetration of different molecular weight hydrolysed keratins into hair fibres and their effects on the physical properties of textured hair. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2021, 43, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesche, E. S.; Körner, A.; Schäfer, K.; Wortmann, F. J. Prevention of hair surface aging. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2011, 2011 62, 237–49. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, F. B. Jr.; Minami, M. M.; Rossan, M. R.; et al. Prevention of chemically induced hair damage by means of treatment based on proteins and polysaccharides. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallaro, G.; Milioto, S.; Konnova, S.; et al. Halloysite/keratin nanocomposite for human hair photoprotection coating. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 24348–24362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, K.; Yamazaki, J.; Okita, N.; et al. Mechanism of cuticle hole development in human hair due to UV-radiation exposure. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekara, M. N.; Ranganathaiah, C. Chemical and photochemical degradation of human hair: A free-volume microprobe study. J. Photoch. Photobio. B 2010, 101, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiayi, F.; Wenshen, Y.; Marina, B.; et al. Study on the efficacy and mechanism of an amino acid combination in hair care. China Surfactant Detergent & Cosmetics 2024, 54, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).