1. Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a valuable curative therapy for hematological malignancies; however, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) remains of concern, although recent advances have reduced its incidence [

1,

2]. Antithymocytic globulin (ATG) and post-transplant cyclophosphadmide (PTCy) were the most popularly used regimens for the prevention of acute and chronic GVHD [

3,

4]. ATG is polyclonal T cell depleting antibody, usually targeted for T cell antigen and ATG significantly enhanced overall survival and GVHD-free survival compared to those of patients not given ATG in patients undergoing human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched donor HSCT [

5,

6]. PTCy also effectively eradicates alloreactive T cells after haplo-identical stem cell infusion, but hematopoietic stem cells are spared; thus, PTCy could reduce the incidences of acute and chronic GVHD [

7,

8].

ATG and PTCy had comparable clinical outcomes in terms of overall survival, relapse rate, and incidence of acute or chronic GVHD in the setting of HLA-matched or haplo-identical HSCT [

9,

10,

11]. However, few studies have been reported on their biological features, especially regulatory T (Treg) cells between ATG and PTCy. Treg cells are a functionally distinct subset of mature T cells with broad suppressive activity and play a central role in maintaining immune tolerance and suppressing potentially harmful immune responses after allogeneic HSCT [

12,

13]. Treg cells are closely related to GVHD and are considered as therapeutic targets for various agents such as interleukin-2 (IL-2) [

14,

15,

16]. For example, Kennedy-Nasser et al. demonstrated that ultra-low-dose IL-2 expands a Treg population in vivo and may be associated with a lower incidence of GVHD [

15]. And adoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded Treg cells had clinical improvement with substantially decreased steroid-refractory GVHD activity [

17].

Treg cells are differentiated from CD4+ T cells and classically identified by the expression of FOXP3 or IL-2 receptor α chain (CD25). As a way to consider heterogeneity of the Treg compartment and analyze the property of Treg subpopulation, CD45RA was introduced to discriminate between antigen-experienced Treg (e.g., CD45RA

-) and naïve Treg (e.g., CD45RA

+) cells [

18,

19]. Treg subsets have been extensively studied to analyze the pathophysiology of autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and Behçet's disease [

20,

21,

22]. For example, in a study conducted on patients with RA, there was no difference in the total Treg population in the peripheral blood of RA patients and healthy controls, but the effector Treg, defined as CD45RA

-CD25

hi population, was significantly decreased in RA patients compared to healthy individuals [

23]. There is lack of data analyzing Treg cell subpopulations between ATG and PTCy group for the GVHD prophylaxis. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the subset of Treg cells between these two regimens in patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing allogeneic HSCT.

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of patients are given in

Table 1. Between June 2018 and June 2023, 45 patients were included in the study. In the PTCy group, 17 patients were enrolled, 5 with HLA matched donors and 12 with HLA haplo-identical donors, while in the ATG group, all 28 patients were enrolled with HLA matched donors. The median age for all patients was 54 years, with a range of 21 to 71 years. There were no differences between both groups in terms of gender, median age, type and status of diseases, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation comorbidity index (HCT-CI), type of conditioning regimes, median stem cells dose infused and median follow-up duration. However, CMV reactivation was significantly higher in the PTCy group compared to the ATG group (76.5% vs. 28.6%, p=0.002).

2.2. GVHD

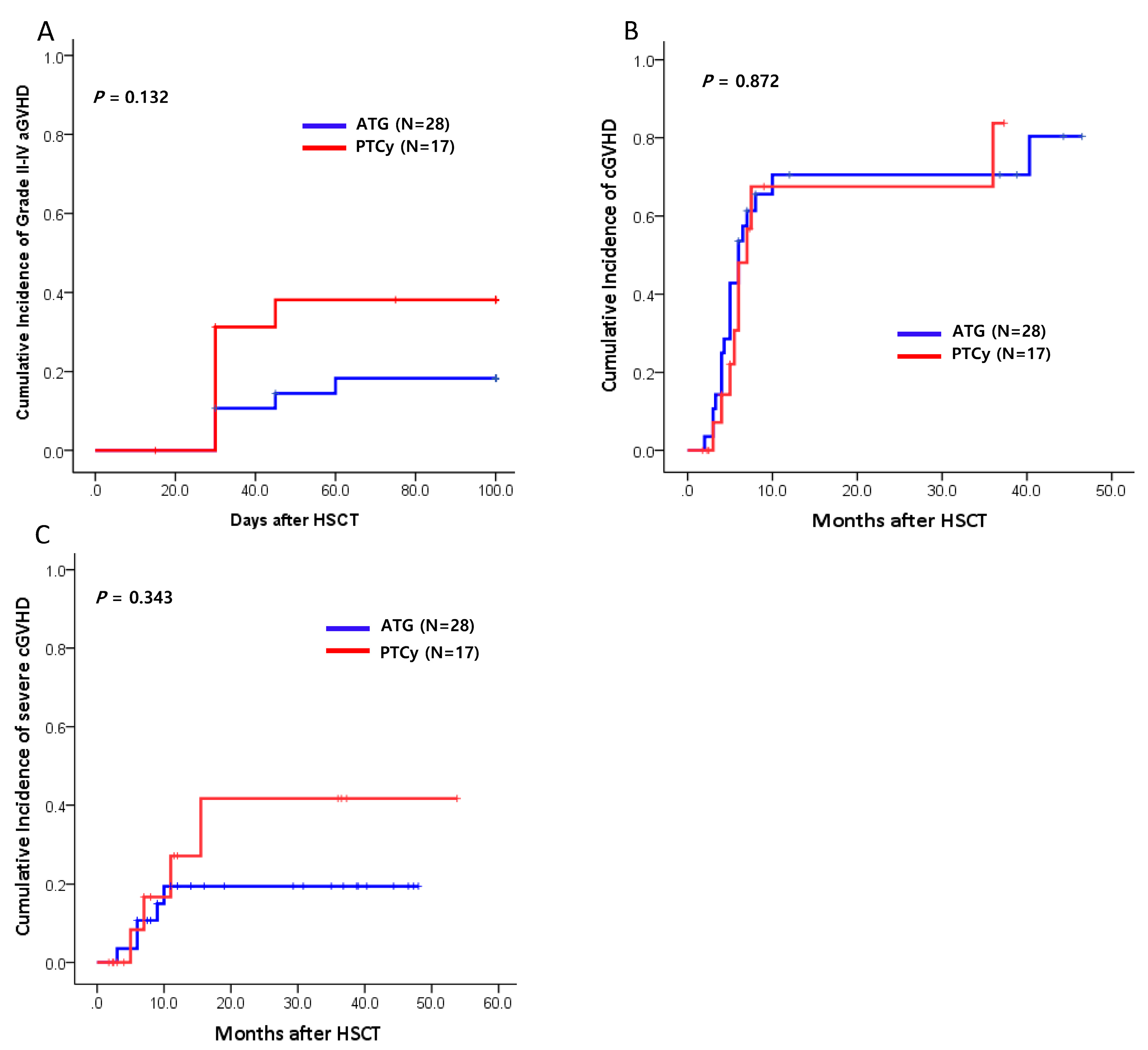

The cumulative incidence (CI) of grade II-IV acute GVHD at 100 days post-transplantation was 18% (95% CI: 12%-20%) in the ATG group, and 38% (95% CI: 10%- 42%) in the PTCy group (

Figure 1A). The CI of chronic GVHD at 1 year was 67% in the ATG group and 71% in the PTCy group (p=0.872;

Figure 1B). There were similar the CI of severe degree chronic GVHD between both groups (19% vs. 42%, p=0.343,

Figure 1C).

2.3. Survival Outcomes

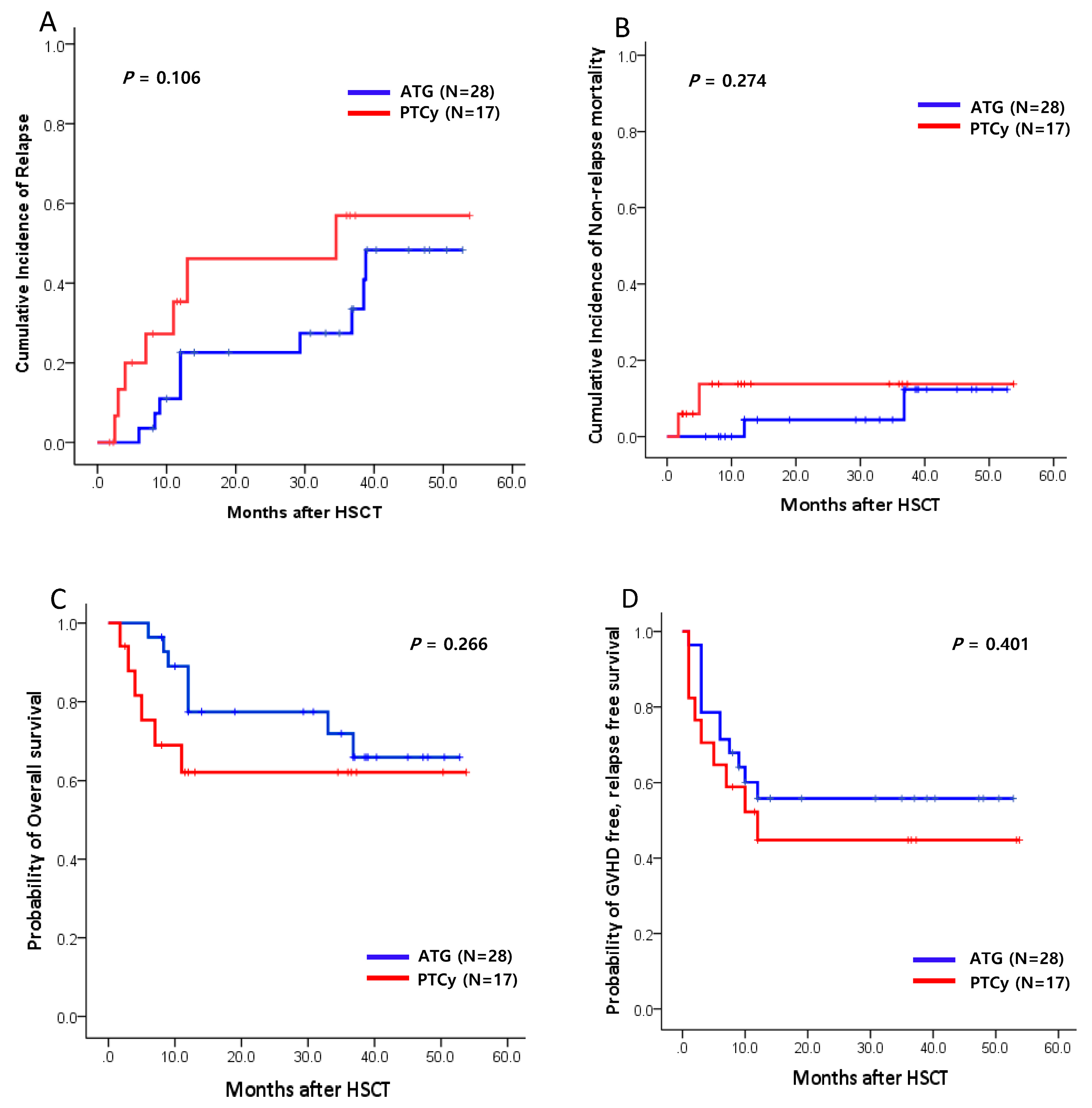

With the median follow-up of 19.0 months (range, 1.8-53.8 months) for all patients, there was no significant difference in the CI of relapse at 1 year between the two groups (ATG vs. PTCy, 22.6% vs. 35.4%; p=0.106;

Figure 2A). The 1-year CI of NRM was 11.7% for the ATG group and 13.1% for the PTCy group (p=0.274;

Figure 2B). Infections and GVHD were the most common causes of NRM, with no significant difference in the causes of death between the two GVHD prophylaxis groups. The 1-year OS was 77.4% for the ATG group and 62.1% for the PTCy group (p=0.266;

Figure 2C). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the 1-year GFRS between two groups (64.1% vs. 44.8%, respectively, p=0.401;

Figure 2D).

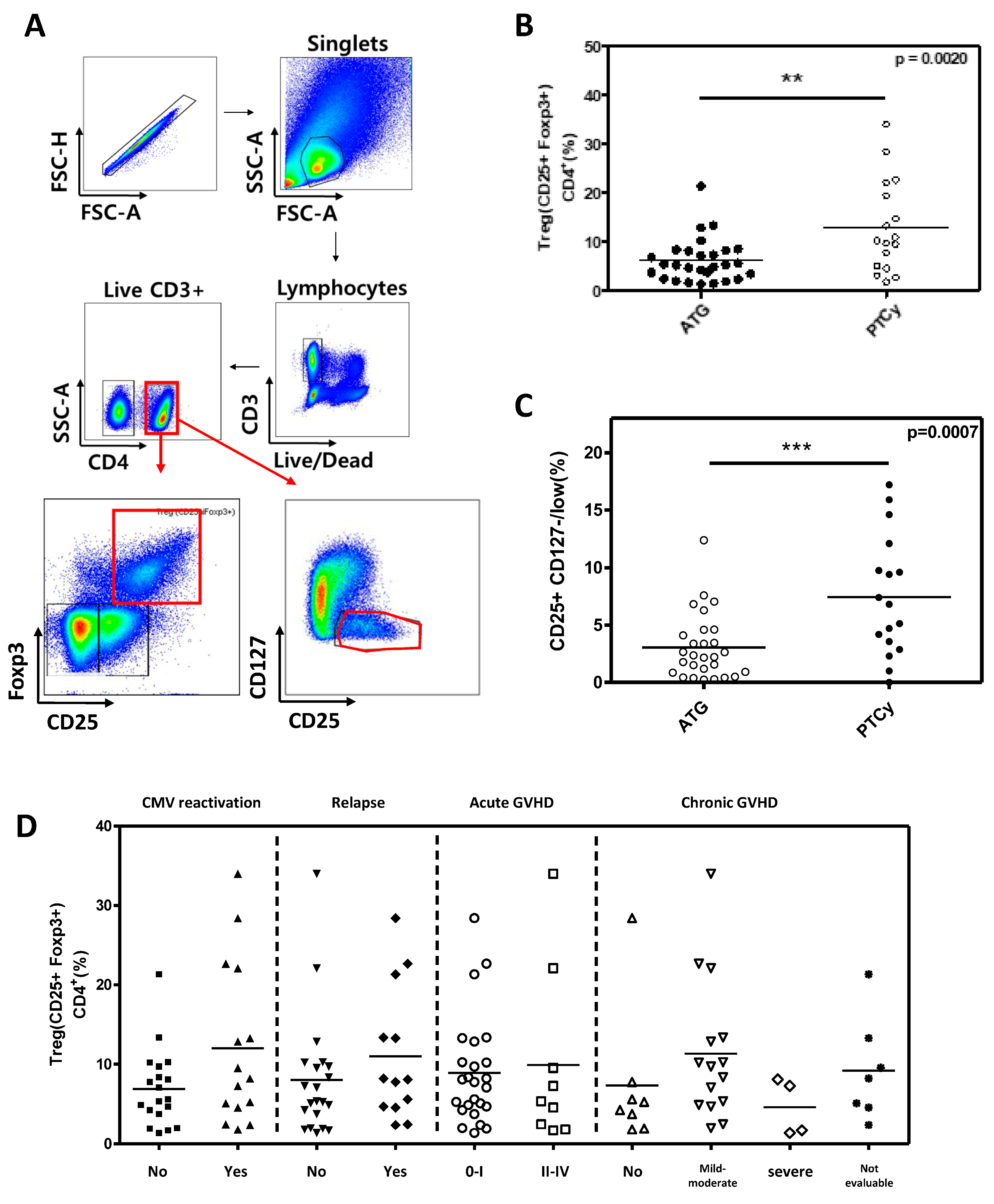

2.4. Regulatory T Cells and Their Subpopulation

First, we analyzed the conventional Treg cells, defined as CD4

+CD25

+FOXP3

+ in both ATG and PTCy group (

Figure 3A). The proportion of conventional Treg cells was statistically significantly higher than in the PTCy group compared to the ATG group (12.96% in PTCy

vs 6.14 % in ATG group, p=0.0020;

Figure 3B). Similar results were observed when defining Treg cells as CD25

+CD127

low (7.44% in PTCy

vs 3.06 % in ATG group, p=0.0007;

Figure 3C). However, conventional Treg cells were not significantly associated with clinical outcomes such as CMV reactivation, relapse, acute GVHD and chronic GVHD (

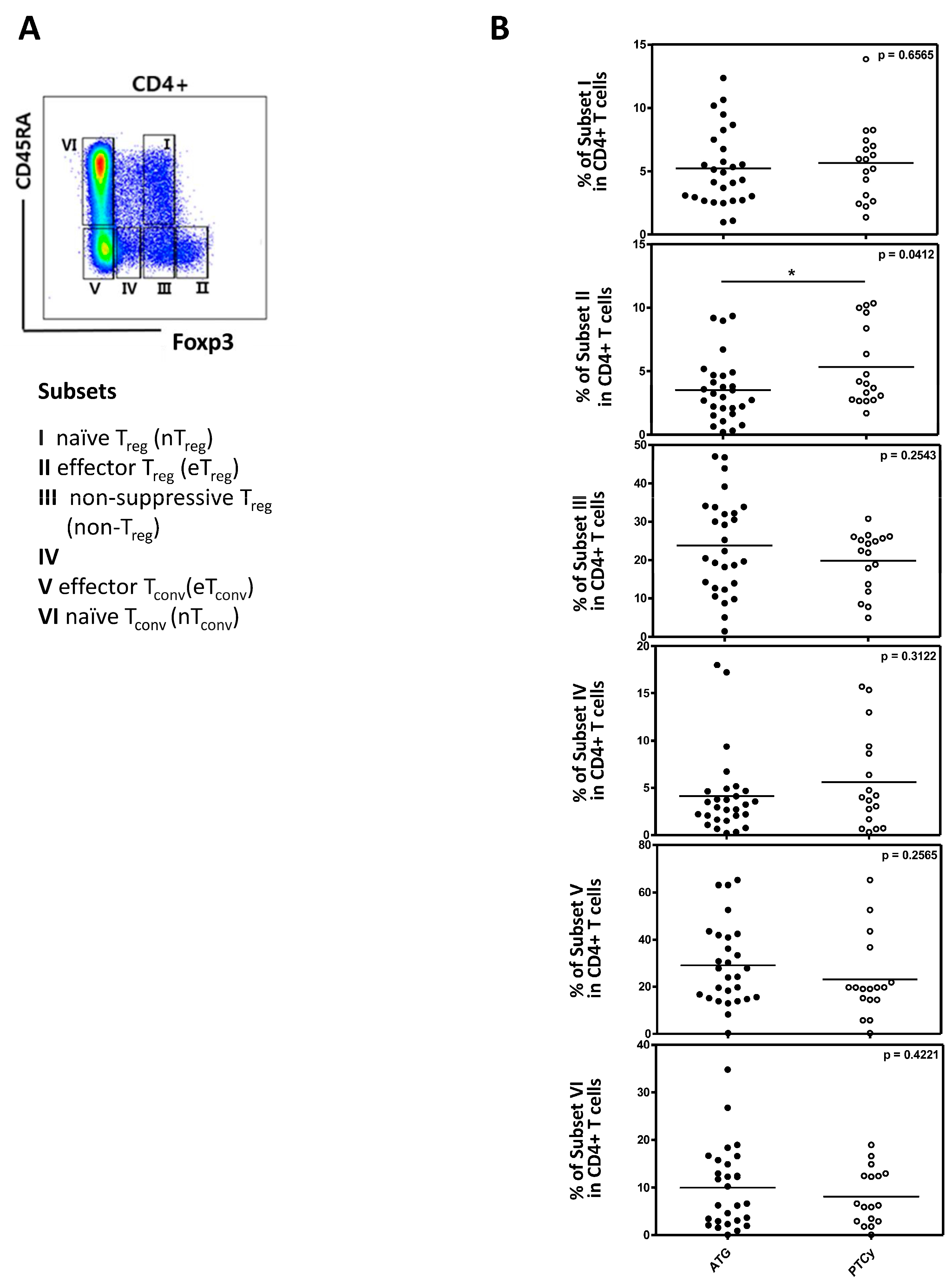

Figure 3D). When Treg cells were divided into three subpopulations based on CD45RA and FOXP3, the effector Treg subset was significantly higher in the PTCy group compared to the ATG group, while other subsets did not differ between the two groups. there were statistically significant differences between the two groups in effector Treg subset (

Figure 4A and 4B).

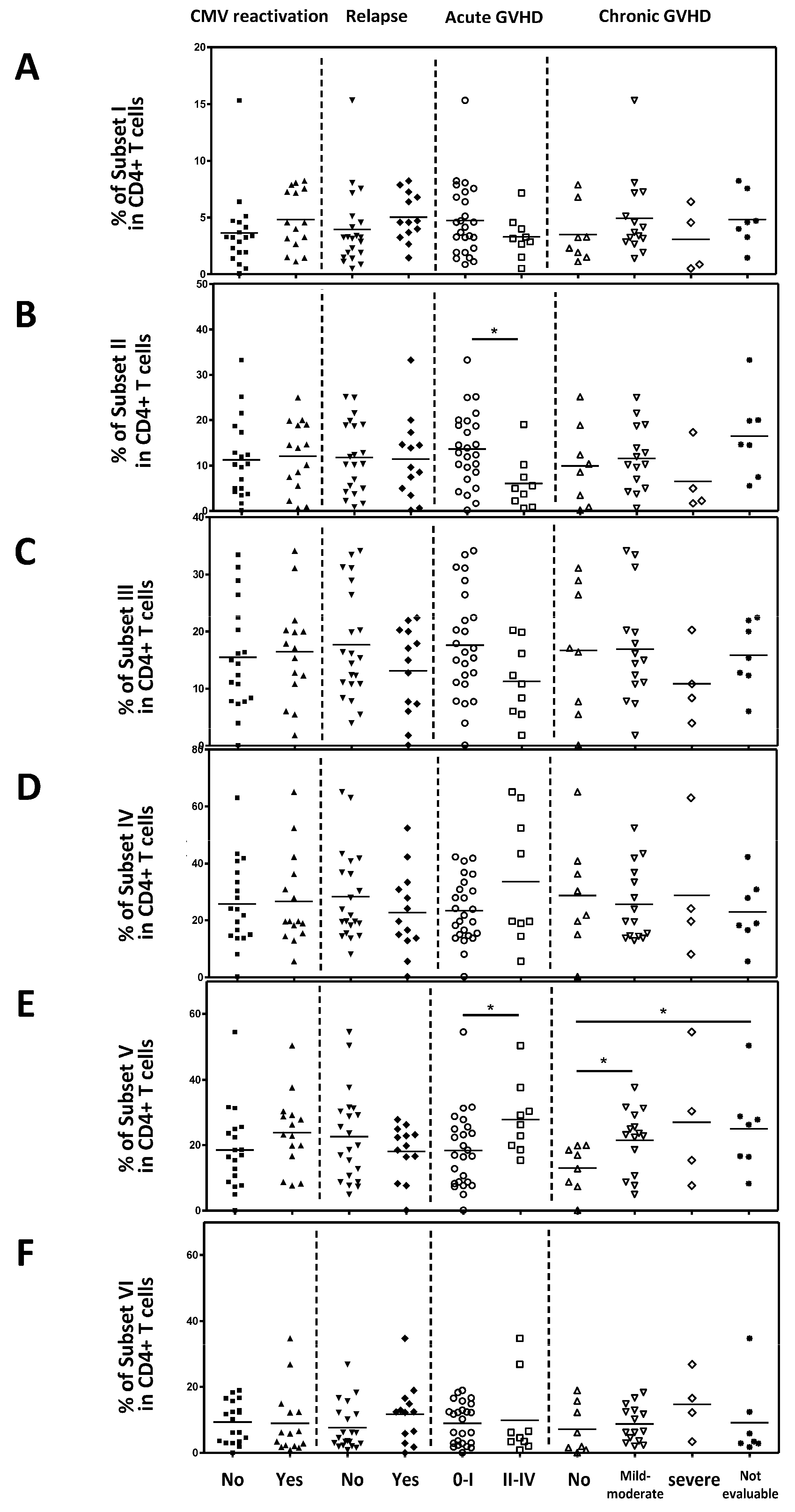

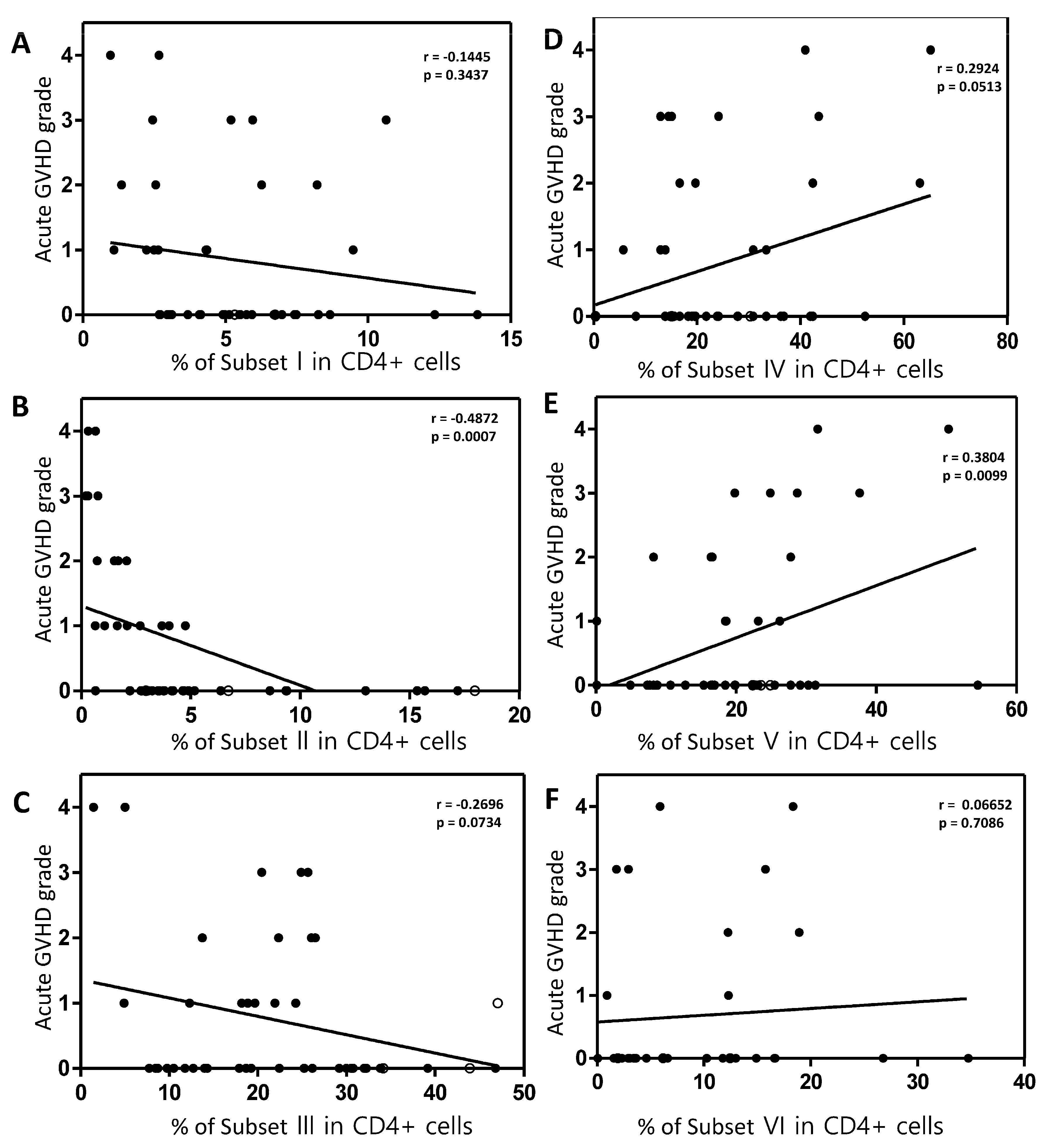

2.5. The Association Between Active Treg Cells and Clinical Outcomes

Next, we analyzed the correlation between each Treg subset and clinical outcomes. Naive Tregs (subset I), naive CD4+T cells (subset VI), non-suppressive Tregs (subset III) and subset IV did not correlate with clinical outcomes (

Figure 5A, 5C, 5D, 5F). However, effector Treg cells (subset II) were significantly lower in patients with Grade II-IV acute GVHD compared to those with acute GVHD grade 0-I (p=0.0154;

Figure 5B). Conventional CD4+T cells (Subset V) were statistically significantly increased in patients with grade II to IV acute GVHD compared to those with acute GVHD grade 0-I and mild to moderate chronic GVHD compared to those without chronic GVHD (

Figure 5E). And in Spearman correlation analysis, an inverse correlation was observed between the severity of acute GVHD and the effector Treg cells (p=0.007;

Figure 6B). Furthermore, a positive correlation was observed between conventional CD4+ T cells (subset V) and the severity of acute GVHD (

Figure 6E). However, other subsets did not correlate with the severity of acute GVHD (

Figure 6A, 6C, 6D and 6F).

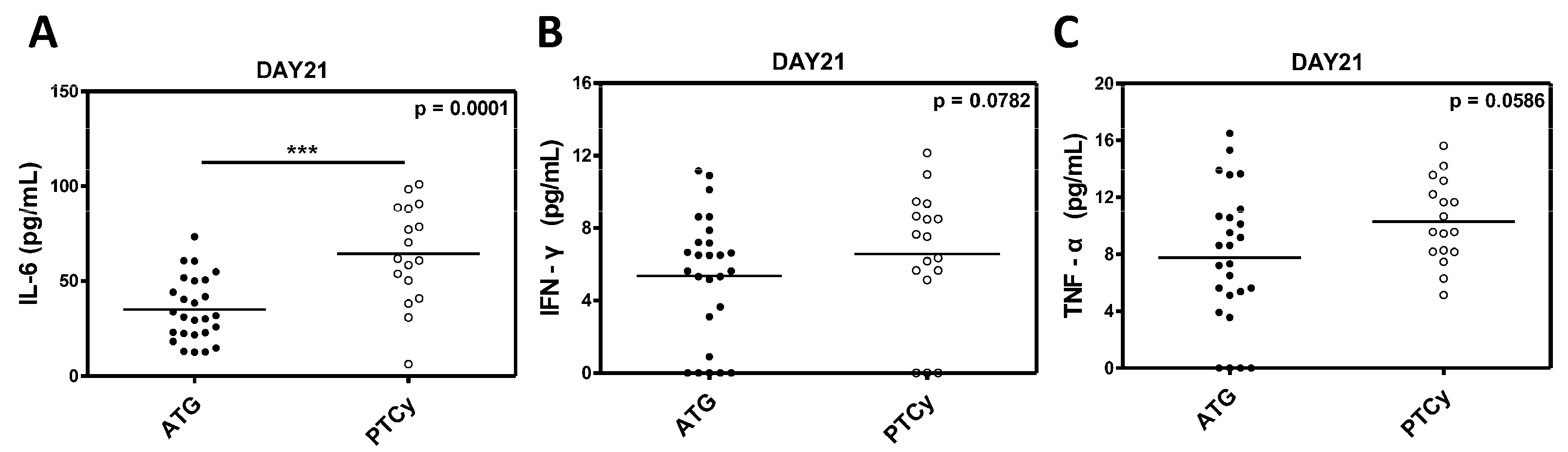

2.6. Inflammatory Cytokine Levels

Serum levels of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IFN-γ and TNF-α were measured to evaluate the immunological environment and its impact on Treg cells in the ATG and PTCy groups. The IL-6 levels were significantly elevated in the PTCy group compared to the ATG group (p = 0.0001;

Figure 7A), indicating a stronger inflammatory milieu in the PTCy-treated patients. While the differences in IFN-γ and TNF-α levels did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0782 and p = 0.0586, respectively), we observed a trend toward a higher inflammatory response in the PTCy group (

Figure 7B and 7C).

3. Discussion

In this study, we found that using PTCy as a prophylactic regimen for GVHD preserves Treg cells better than using ATG. Among the patients included in this study, all patients of the ATG group received allogeneic HSCT from HLA-matched donors, while the PTCy group had approximately 70% of patients receiving haplo-identical donor HSCT. The fact that there was no significant difference in clinical outcomes despite the fact that the PTCy group received HSCT under unfavorable conditions, as shown in this study, suggests that the use of PTCy is more effective in preventing GVHD by preserving Treg cells. In our study, serum IL-6 levels were significantly higher in the PTCy group than in the ATG group. IL-6 is known not only to inhibit TGFβ-induced T cell differentiation into regulatory T cells but also downregulate FOXP3 expression on Treg cells [

24,

25]. IL-6 is also considered a potential biomarker of acute GVHD after allogeneic HSCT, and elevated IL-6 levels have been shown to be significantly associated with worse outcomes, including severe cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and acute GVHD, and decreased overall survival. [

26,

27]. However, in this study, despite higher IL-6 levels in the PTCy group, the incidence and severity of GVHD was similar to the ATG group, which may be due to better preservation of Tregs with PTCy, resulting in higher Treg levels in the PTCy group.

In the EBMT registry study for comparing ATG and PTCy in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients underwent haplo-identical HSCT, patients in the PTCy group had significantly less grade III-IV acute GVHD than those in the ATG group [

28]. And patients receiving PTCy had better GVHD-free, relapse-free survival and leukemia-free survival than those in ATG group. In a meta-analysis study, PTCy also demonstrates a more favorable effect in preventing acute GVHD and improving overall survival (OS) compared to ATG [

29]. This is thought to be attributed not only to the effective removal of alloreactive T cells by PTCy after allogeneic HSCT but also to the better recovery of Treg cells in the PTCy group, which observed in our study. Rambaldi et al. also reported that the recovery of Treg cells after haplo-identical HSCT using PTCy was earlier than that after HLA-identical HSCT, resulting in a significantly higher Tregs/conventional T-cell ratio during early period after HSCT [

30].

The results of this study alone are insufficient to fully elucidate the pathophysiology of why PTCy preserves Treg cells more effectively compared to ATG. However, by integrating findings from previously reported studies, it can be explained that rabbit ATG acts not only on alloreactive T cells but also on Treg cells, and its long half-life sustains this effect for an extended period. Consequently, due to the nature of ATG, Treg cells are presumed to undergo depletion following HSCT. On the other hand, PTCy primarily affects actively proliferating alloreactive T or NK cells and spares hematopoietic stem cell or Treg cells by their high expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase [

31]. In the murine experiment conducted by Ganguly et al., rapid recovery of donor-derived Tregs was observed after PTCy treatment, suggesting its potential role in GVHD prevention [

32]. This suggests that PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis preferentially promotes the reconstitute of Tregs in a clinical setting. In a previous study on post-transplant complications associated with Treg cells that we reported, it was observed that in most patients treated with PTCy after allo-HSCT, naïve and effector Treg cells were well-preserved. However, in some patients with insufficient Treg cells, the manifestation of life-threatening GVHD or complications such as autoimmune limbic encephalitis was observed [

33].

As effective as PTCy is in preventing GVHD, there are still challenges that need to be addressed. Firstly, despite the use of PTCy, some patients still experience severe GVHD or CRS [

34]. To address this issue, recent approaches include combining PTCy and ATG, which has been reported to be more effective in reducing GVHD than either alone. [

35,

36,

37]. Second, T-cell depletion appears to occur more frequently with PTCy compared to patients not using PTCy, which, along with high levels of Treg cells, contributes to a higher risk of relapse. For example, in the EBMT registry data, we observe a slightly higher recurrence rate in the PTCy group compared to the ATG group [

28]. Therefore, for patients at high risk of relapse after allo-HSCT, additional efforts will be needed to prevent relapse, such as donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) or maintenance therapy.

To our knowledge, this study is the first report to compare subpopulation of Treg cells in patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT when using ATG and PTCy. Furthermore, given the inverse correlation observed between effector Treg cells measured in peripheral blood early post-transplant and the severity of acute GVHD, it could be used as a biomarker to predict the severity of acute GVHD after allogeneic HSCT. Therefore, in patients at high risk for acute GVHD due to low levels of effector Treg cells, interventions such as increasing the dose of immunosuppressive agents or administering a GVHD treatment agents such as ruxolinitib earlier should be considered.

In conclusion, the use of PTCy preserves Treg cells more effectively compared to using ATG, and among the Treg subpopulations, effector Treg cells exhibit an inverse correlation with the severity of acute GVHD. Therefore, effector Tregs can be used as a biomarker to predict the severity of acute GVHD after allo-HSCT.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients and Treatments

We retrospectively analyzed consecutive adult patients (age, >18 years) with hematological malignancies who underwent allogeneic HSCT in Chungnam National University Hospital (Daejeon, South Korea) between June 2018 and June 2023. We excluded those receiving second transplantations and patients with refractory disease. PTCy was given on days +3 and +4 at a dose of 50 mg/kg. Rabbit ATG (thymoglobulin; Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France) was given from days -3 to -1 at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg. We usually assigned PTCy in haplo-identical HSCT and ATG in HLA-matched donor HSCT for prophylaxis of GVHD according to the institute’s policy. Two conditioning regimens were used. In the myeloablating conditioning (MAC) regimen, 3.2 mg/kg busulfan was administered for 4 days and 40 mg/m2 fludarabine was administered for 5 days. In the reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimen, 3.2 mg/kg busulfan was administered for 2 days and 30 mg/m2 fludarabine was administered for 6 days. RIC was administered to patients over 55 years of age or with comorbidities. No pharmacokinetic adjustment of busulfan dose was performed. Cyclosporine or tacrolimus for GVHD prophylaxis was given commencing on day -1 in ATG group and on day +5 in PTCy group. All patients received granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs; target CD34+ cell count, 5 x 106/kg). Filgrastim 300ug/m2 was administered from day +5 until neutrophil recovery. Any therapy for prevention of relapse after allogeneic HSCT, such as donor lymphocyte infusion or hypomethylating agents or tyrosine kinase inhibitors, was not added.

4.2. Clinical Outcomes

We collected clinical data for assessing the overall survival (OS), the incidences and severity of acute and chronic GVHD, the relapse rate, non-relapse mortality (NRM) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) & Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivation. Acute GVHD was graded using the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium (MAGIC) criteria, and chronic GVHD was graded according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus [

38,

39]. And GVHD-free, relapse-free survival (GFRS) was defined as the occurrence of any of the following events from the time of transplantation; grade III or IV acute GVHD, chronic GVHD warranting systemic immunosuppression, disease relapse or progression or death from any cause. NRM was defined as death from any cause other than relapse. CMV and EBV reactivation was defined as detection of viral DNA in whole blood by PCR at least once.

4.3. Assessment of Regulatory T Cells Subpopulation and Cytokine

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained from whole blood at day+21 after allogeneic HSCT using lymphocyte separation medium (Corning) by density gradient centrifugation. PBMC were stained with live/dead fixable stain dye (Life technologies) to distinguish live and dead cells. After PBS washing, cells were incubated with FITC-CD3 (BD Biosciences), PerCP-Cy5.5-CD4 (BD Biosciences), BV421-CD25 (BD Biosciences), APC-CD127 (Biolegend), and PE-Cy7-CD45RA (BD Biosciences). Cells were then fixed and permeabilized with Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience) and further stained with PE-Foxp3 (BD Biosciences). Based on markers CD25 and CD45RA, the subpopulation of Treg are as follows: CD25intCD45RA+ cells (Subgroup I, naïve/resting Treg),

CD25

hiCD45RA

− cells (Subgroup II, activated/effector Treg), CD25

intCD45RA

− cells (Subgroup III, non-suppressive Treg), CD25

lowCD45RA

− cells (Subgroup IV), CD25

−CD45RA

−cells (Subgroup V, effector Tconv), and CD25

-CD45RA

+ cells (Subgroup VI, naïve Tconv) (

Figure 1). Treg cells and their subpopulation were analyzed with a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biociences), and data were processed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, OR, USA). Interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of plasma samples.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test and logistic regression was employed to examine correlations. Overall and leukemia-free survival was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival rates were compared using the log-rank test. Cumulative incidence functions were used to estimate the acute and chronic GVHD rates, relapse rate, and NRM. A p-value <0.05 was considered to reflect significance. All statistical analyses were performed with the aid of SPSS software ver. 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

4.5. Ethics Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungnam National University Hospital (IRB No. CNUH 2018-08-013-012). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Author Contributions

BY Heo: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing original draft preparation. JS Koh: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, funding, writing original draft preparation. SY Choi: Conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing original draft preparation. TTD Pham: Methodology, investigation, data curation. SW Lee: Methodology, investigation, data curation. JH Park: Methodology, data curation, validation. YS Jang: Methodology, data curation, validation. MW Lee: Methodology, data curation, validation. SB Lee: Methodology, data curation, validation. WH Seo: Methodology, data curation, investigation. DY Jo: Supervision, validation, writing review & editing. J Kwon: Conceptualization, supervision, formal analysis, validation, data curation, writing review & editing. IC Song: Conceptualization, supervision, methodology, funding, formal analysis, validation, data curation, writing review & editing.

Data Access Statement

Original data can be requested from the corresponding author (petrosong@cnu.ac.kr).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (NRF-2021R1C1C1012397) and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (RS-2020-KH088690) and was supported by the research fund of Chungnam National University, 2024.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest existed.

References

- Gooley, T. A., J.W. Chien, S. A. Pergam, S. Hingorani, M. L. Sorror, M. Boeckh, P. J. Martin, B. M. Sandmaier, K. A. Marr, F. R. Appelbaum, R. Storb, and G. B. McDonald. "Reduced Mortality after Allogeneic Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation." N Engl J Med 363, no. 22 (2010): 2091-101. [CrossRef]

- Penack, O., M.Marchetti, T. Ruutu, M. Aljurf, A. Bacigalupo, F. Bonifazi, F. Ciceri, J. Cornelissen, R. Malladi, R. F. Duarte, S. Giebel, H. Greinix, E. Holler, A. Lawitschka, S. Mielke, M. Mohty, M. Arat, A. Nagler, J. Passweg, H. Schoemans, G. Socié, C. Solano, R. Vrhovac, R. Zeiser, N. Kröger, and G. W. Basak. "Prophylaxis and Management of Graft Versus Host Disease after Stem-Cell Transplantation for Haematological Malignancies: Updated Consensus Recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation." Lancet Haematol 7, no. 2 (2020): e157-e67. [CrossRef]

- Kröger, N., C.Solano, C. Wolschke, G. Bandini, F. Patriarca, M. Pini, A. Nagler, C. Selleri, A. Risitano, G. Messina, W. Bethge, J. Pérez de Oteiza, R. Duarte, A. M. Carella, M. Cimminiello, S. Guidi, J. Finke, N. Mordini, C. Ferra, J. Sierra, D. Russo, M. Petrini, G. Milone, F. Benedetti, M. Heinzelmann, D. Pastore, M. Jurado, E. Terruzzi, F. Narni, A. Völp, F. Ayuk, T. Ruutu, and F. Bonifazi. "Antilymphocyte Globulin for Prevention of Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease." N Engl J Med 374, no. 1 (2016): 43-53. [CrossRef]

- Rimando, J., S.R. McCurdy, and L. Luznik. "How I Prevent Gvhd in High-Risk Patients: Posttransplant Cyclophosphamide and Beyond." Blood 141, no. 1 (2023): 49-59. [CrossRef]

- Mohty, M. "Mechanisms of Action of Antithymocyte Globulin: T-Cell Depletion and Beyond." Leukemia 21, no. 7 (2007): 1387-94. [CrossRef]

- Mohty, M., and F. Malard. "Antithymocyte Globulin for Graft-Versus-Host Disease Prophylaxis after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation." J Clin Oncol 35, no. 36 (2017): 3993-95. [CrossRef]

- Luznik, L., and E. J. Fuchs. "High-Dose, Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide to Promote Graft-Host Tolerance after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation." Immunol Res 47, no. 1-3 (2010): 65-77. [CrossRef]

- Bashey, A., X.Zhang, C. A. Sizemore, K. Manion, S. Brown, H. K. Holland, L. E. Morris, and S. R. Solomon. "T-Cell-Replete Hla-Haploidentical Hematopoietic Transplantation for Hematologic Malignancies Using Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide Results in Outcomes Equivalent to Those of Contemporaneous Hla-Matched Related and Unrelated Donor Transplantation." J Clin Oncol 31, no. 10 (2013): 1310-6. [CrossRef]

- McCurdy, S. R., Y.L. Kasamon, C. G. Kanakry, J. Bolaños-Meade, H. L. Tsai, M. M. Showel, J. A. Kanakry, H. J. Symons, I. Gojo, B. D. Smith, M. P. Bettinotti, W. H. Matsui, A. E. Dezern, C. A. Huff, I. Borrello, K. W. Pratz, D. E. Gladstone, L. J. Swinnen, R. A. Brodsky, M. J. Levis, R. F. Ambinder, E. J. Fuchs, G. L. Rosner, R. J. Jones, and L. Luznik. "Comparable Composite Endpoints after Hla-Matched and Hla-Haploidentical Transplantation with Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide." Haematologica 102, no. 2 (2017): 391-400. [CrossRef]

- Baron, F., M.Labopin, J. Tischer, F. Ciceri, A. M. Raiola, D. Blaise, S. Sica, J. Vydra, R. Fanin, J. L. Diez-Martin, C. E. Bulabois, F. Stölzel, A. Busca, P. Jindra, Y. Koc, P. Chevallier, E. Forcade, W. Rösler, J. Passweg, A. Kulagin, A. M. Carella, C. Simand, A. Bazarbachi, P. Pioltelli, A. Nagler, and M. Mohty. "Comparison of Hla-Mismatched Unrelated Donor Transplantation with Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide Versus Hla-Haploidentical Transplantation in Patients with Active Acute Myeloid Leukemia." Bone Marrow Transplant 57, no. 11 (2022): 1657-63.

- Nagler, A., A.S. Kanate, M. Labopin, F. Ciceri, E. Angelucci, Y. Koc, Z. Gülbas, W. Arcese, J. Tischer, P. Pioltelli, H. Ozdogu, B. Afanasyev, D. Wu, M. Arat, Z. Peric, S. Giebel, B. Savani, and M. Mohty. "Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide Versus Anti-Thymocyte Globulin for Graft-Versus-Host Disease Prevention in Haploidentical Transplantation for Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia." Haematologica 106, no. 6 (2021): 1591-98. [CrossRef]

- Ikegawa, S., and K. I. Matsuoka. "Harnessing Treg Homeostasis to Optimize Posttransplant Immunity: Current Concepts and Future Perspectives." Front Immunol 12 (2021): 713358. [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, K., H.T. Kim, S. McDonough, G. Bascug, B. Warshauer, J. Koreth, C. Cutler, V. T. Ho, E. P. Alyea, J. H. Antin, R. J. Soiffer, and J. Ritz. "Altered Regulatory T Cell Homeostasis in Patients with Cd4+ Lymphopenia Following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation." J Clin Invest 120, no. 5 (2010): 1479-93. [CrossRef]

- Meguri, Y., T.Asano, T. Yoshioka, M. Iwamoto, S. Ikegawa, H. Sugiura, Y. Kishi, M. Nakamura, Y. Sando, T. Kondo, Y. Sumii, Y. Maeda, and K. I. Matsuoka. "Responses of Regulatory and Effector T-Cells to Low-Dose Interleukin-2 Differ Depending on the Immune Environment after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation." Front Immunol 13 (2022): 891925. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy-Nasser, A. A., S.Ku, P. Castillo-Caro, Y. Hazrat, M. F. Wu, H. Liu, J. Melenhorst, A. J. Barrett, S. Ito, A. Foster, B. Savoldo, E. Yvon, G. Carrum, C. A. Ramos, R. A. Krance, K. Leung, H. E. Heslop, M. K. Brenner, and C. M. Bollard. "Ultra Low-Dose Il-2 for Gvhd Prophylaxis after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Mediates Expansion of Regulatory T Cells without Diminishing Antiviral and Antileukemic Activity." Clin Cancer Res 20, no. 8 (2014): 2215-25.

- Matsuoka, K. I. "Low-Dose Interleukin-2 as a Modulator of Treg Homeostasis after Hsct: Current Understanding and Future Perspectives." Int J Hematol 107, no. 2 (2018): 130-37. [CrossRef]

- Landwehr-Kenzel, S., L.Müller-Jensen, J. S. Kuehl, M. Abou-El-Enein, H. Hoffmann, S. Muench, D. Kaiser, A. Roemhild, H. von Bernuth, M. Voeller, M. Schmueck-Henneresse, B. Gruhn, U. Stervbo, N. Babel, H. D. Volk, and P. Reinke. "Adoptive Transfer of Ex vivo Expanded Regulatory T Cells Improves Immune Cell Engraftment and Therapy-Refractory Chronic Gvhd." Mol Ther 30, no. 6 (2022): 2298-314. [CrossRef]

- Fontenot, J. D., M.A. Gavin, and A. Y. Rudensky. "Foxp3 Programs the Development and Function of Cd4+Cd25+ Regulatory T Cells." Nat Immunol 4, no. 4 (2003): 330-6. [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, E., M.van den Biggelaar, S. de Kivit, Y. Y. Chen, M. Slot, I. Doubal, A. Meijer, R. A. W. van Lier, J. Borst, and D. Amsen. "Proteomic Analyses of Human Regulatory T Cells Reveal Adaptations in Signaling Pathways That Protect Cellular Identity." Immunity 48, no. 5 (2018): 1046-59.e6. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. R., J.N. Chae, S. H. Kim, and J. S. Ha. "Subpopulations of Regulatory T Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, and Behcet's Disease." J Korean Med Sci 27, no. 9 (2012): 1009-13.

- Dominguez-Villar, M., and D. A. Hafler. "Regulatory T Cells in Autoimmune Disease." Nat Immunol 19, no. 7 (2018): 665-73. [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, S., N.Mikami, J. B. Wing, A. Tanaka, K. Ichiyama, and N. Ohkura. "Regulatory T Cells and Human Disease." Annu Rev Immunol 38 (2020): 541-66.

- Go, E., S.J. Yoo, S. Choi, P. Sun, M. K. Jung, S. Kwon, B. Y. Heo, Y. Kim, J. G. Kang, J. Kim, E. C. Shin, S. W. Kang, and J. Kwon. "Peripheral Blood from Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Shows Decreased T(Reg) Cd25 Expression and Reduced Frequency of Effector T(Reg) Subpopulation." Cells 10, no. 4 (2021).

- Korn, T., and M. Hiltensperger. "Role of Il-6 in the Commitment of T Cell Subsets." Cytokine 146 (2021): 155654. [CrossRef]

- van Loosdregt, J., V.Fleskens, J. Fu, A. B. Brenkman, C. P. Bekker, C. E. Pals, J. Meerding, C. R. Berkers, J. Barbi, A. Gröne, A. J. Sijts, M. M. Maurice, E. Kalkhoven, B. J. Prakken, H. Ovaa, F. Pan, D. M. Zaiss, and P. J. Coffer. "Stabilization of the Transcription Factor Foxp3 by the Deubiquitinase Usp7 Increases Treg-Cell-Suppressive Capacity." Immunity 39, no. 2 (2013): 259-71. [CrossRef]

- Norelli, M., B.Camisa, G. Barbiera, L. Falcone, A. Purevdorj, M. Genua, F. Sanvito, M. Ponzoni, C. Doglioni, P. Cristofori, C. Traversari, C. Bordignon, F. Ciceri, R. Ostuni, C. Bonini, M. Casucci, and A. Bondanza. "Monocyte-Derived Il-1 and Il-6 Are Differentially Required for Cytokine-Release Syndrome and Neurotoxicity Due to Car T Cells." Nat Med 24, no. 6 (2018): 739-48. [CrossRef]

- Greco, R., F.Lorentino, R. Nitti, M. T. Lupo Stanghellini, F. Giglio, D. Clerici, E. Xue, L. Lazzari, S. Piemontese, S. Mastaglio, A. Assanelli, S. Marktel, C. Corti, M. Bernardi, F. Ciceri, and J. Peccatori. "Interleukin-6 as Biomarker for Acute Gvhd and Survival after Allogeneic Transplant with Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide." Front Immunol 10 (2019): 2319. [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, A., Y.Sun, M. Labopin, A. Bacigalupo, F. Lorentino, W. Arcese, S. Santarone, Z. Gülbas, D. Blaise, G. Messina, A. Ghavamzadeh, F. Malard, B. Bruno, J. L. Diez-Martin, Y. Koc, F. Ciceri, M. Mohty, and A. Nagler. "Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide Versus Anti-Thymocyte Globulin as Graft- Versus-Host Disease Prophylaxis in Haploidentical Transplant." Haematologica 102, no. 2 (2017): 401-10. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F., J.Zhang, J. Hu, L. Lin, and Y. Xu. "Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide Versus Antithymocyte Globulin in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Meta-Analysis." Ann Hematol 100, no. 2 (2021): 529-40. [CrossRef]

- Rambaldi, B., H.T. Kim, C. Reynolds, S. Chamling Rai, Y. Arihara, T. Kubo, L. Buon, M. Gooptu, J. Koreth, C. Cutler, S. Nikiforow, V. T. Ho, E. P. Alyea, J. H. Antin, C. J. Wu, R. J. Soiffer, J. Ritz, and R. Romee. "Impaired T- and Nk-Cell Reconstitution after Haploidentical Hct with Posttransplant Cyclophosphamide." Blood Adv 5, no. 2 (2021): 352-64. [CrossRef]

- Kanakry, C. G., S.Ganguly, M. Zahurak, J. Bolaños-Meade, C. Thoburn, B. Perkins, E. J. Fuchs, R. J. Jones, A. D. Hess, and L. Luznik. "Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Expression Drives Human Regulatory T Cell Resistance to Posttransplantation Cyclophosphamide." Sci Transl Med 5, no. 211 (2013): 211ra157. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S., D.B. Ross, A. Panoskaltsis-Mortari, C. G. Kanakry, B. R. Blazar, R. B. Levy, and L. Luznik. "Donor Cd4+ Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells Are Necessary for Posttransplantation Cyclophosphamide-Mediated Protection against Gvhd in Mice." Blood 124, no. 13 (2014): 2131-41. [CrossRef]

- Heo, B. Y., M.W. Lee, S. Choi, Y. Jung, T. T. D. Pham, Y. Jang, J. H. Park, S. Kang, J. S. Koh, D. Y. Jo, J. Kwon, and I. C. Song. "Autoimmune Limbic Encephalitis in Patients with Hematologic Malignancies after Haploidentical Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation with Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide." Cells 12, no. 16 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sanz, J., J.E. Galimard, M. Labopin, B. Afanasyev, E. Angelucci, F. Ciceri, D. Blaise, J. J. Cornelissen, E. Meijer, J. L. Diez-Martin, Y. Koc, M. Rovira, L. Castagna, B. Savani, A. Ruggeri, A. Nagler, and M. Mohty. "Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide after Matched Sibling, Unrelated and Haploidentical Donor Transplants in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Comparative Study of the Alwp Ebmt." J Hematol Oncol 13, no. 1 (2020): 46. [CrossRef]

- Spyridonidis, A., M.Labopin, E. Brissot, I. Moiseev, J. Cornelissen, G. Choi, F. Ciceri, J. Vydra, P. Reményi, M. Rovira, E. Meijer, H. Labussière-Wallet, D. Blaise, G. van Gorkom, N. Kröger, Y. Koc, S. Giebel, A. Bazarbachi, B. Savani, A. Nagler, and M. Mohty. "Should Anti-Thymocyte Globulin Be Added in Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide Based Matched Unrelated Donor Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation for Acute Myeloid Leukemia? A Study on Behalf of the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the Ebmt." Bone Marrow Transplant 57, no. 12 (2022): 1774-80. [CrossRef]

- Duléry, R., E.Brissot, and M. Mohty. "Combining Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide with Antithymocyte Globulin for Graft-Versus-Host Disease Prophylaxis in Hematological Malignancies." Blood Rev (2023): 101080. [CrossRef]

- Koh, J. S., M.W. Lee, T. T. D. Pham, B. Y. Heo, S. Choi, S. W. Lee, W. Seo, S. Kang, S. B. Lee, C. H. Kim, H. Ryu, H. S. Eun, H. J. Lee, H. J. Yun, D. Y. Jo, and I. C. Song. "Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide Plus Anti-Thymocyte Globulin Decreased Serum Il-6 Levels When Compared with Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide Alone after Haploidentical Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation." Blood Res 60, no. 1 (2025): 5. [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. C., R.Young, S. Devine, W. J. Hogan, F. Ayuk, U. Bunworasate, C. Chanswangphuwana, Y. A. Efebera, E. Holler, M. Litzow, R. Ordemann, M. Qayed, A. S. Renteria, R. Reshef, M. Wölfl, Y. B. Chen, S. Goldstein, M. Jagasia, F. Locatelli, S. Mielke, D. Porter, T. Schechter, Z. Shekhovtsova, J. L. Ferrara, and J. E. Levine. "International, Multicenter Standardization of Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease Clinical Data Collection: A Report from the Mount Sinai Acute Gvhd International Consortium." Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 22, no. 1 (2016): 4-10. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. J., D.Wolff, C. Kitko, J. Koreth, Y. Inamoto, M. Jagasia, J. Pidala, A. Olivieri, P. J. Martin, D. Przepiorka, I. Pusic, F. Dignan, S. A. Mitchell, A. Lawitschka, D. Jacobsohn, A. M. Hall, M. E. Flowers, K. R. Schultz, G. Vogelsang, and S. Pavletic. "Measuring Therapeutic Response in Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease: Iv. The 2014 Response Criteria Working Group Report." Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21, no. 6 (2015): 984-99. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidences (CIs) of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) between ATG and PTCy group (n=45). (A) The CI of grade II-IV acute GVHD (aGVHD). (B) The CI of chronic GVHD (cGVHD). (C) The CI of severe chronic GVHD. HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidences (CIs) of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) between ATG and PTCy group (n=45). (A) The CI of grade II-IV acute GVHD (aGVHD). (B) The CI of chronic GVHD (cGVHD). (C) The CI of severe chronic GVHD. HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Figure 2.

Clinical outcomes between ATG and PTCy group (n=45). (A) The CI of relapse. (OS). (B) The CI of non-relapse mortality (NRM). (C) The probability of Overall survival (OS). (D) The probability of GVHD free, relapse free survival (GRFS). HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Figure 2.

Clinical outcomes between ATG and PTCy group (n=45). (A) The CI of relapse. (OS). (B) The CI of non-relapse mortality (NRM). (C) The probability of Overall survival (OS). (D) The probability of GVHD free, relapse free survival (GRFS). HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Treg cells between ATG and PTCy group and association between Treg cells and clinical outcomes. (A) Flow cytometry gating strategy, with CD4+ T cells divided into CD25+Foxp3+ and CD25+ CD127-/low (B) Proportions of CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells among CD4+ T cells were compared between ATG and PTCy patients. (C) Proportions of CD25+ CD127-/low Treg cells among CD4+ T cells were compared between ATG and PTCy patients. (D) Association between CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells and clinical outcomes, such as CMV reactivation, relapse, acute GVHD and chronic GVHD. Statistical difference by two tailed t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Treg cells between ATG and PTCy group and association between Treg cells and clinical outcomes. (A) Flow cytometry gating strategy, with CD4+ T cells divided into CD25+Foxp3+ and CD25+ CD127-/low (B) Proportions of CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells among CD4+ T cells were compared between ATG and PTCy patients. (C) Proportions of CD25+ CD127-/low Treg cells among CD4+ T cells were compared between ATG and PTCy patients. (D) Association between CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells and clinical outcomes, such as CMV reactivation, relapse, acute GVHD and chronic GVHD. Statistical difference by two tailed t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

The analysis of Treg cells subpopulation between ATG and PTCy group (n=45). (A) Flow cytometry gating strategy with division into subsets I-VI based on CD45RA and FOXP3 as indicated. (B) Comparison of CD4+T cells between ATG and PTCy groups in each subset. Statistical difference by two tailed t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. .

Figure 4.

The analysis of Treg cells subpopulation between ATG and PTCy group (n=45). (A) Flow cytometry gating strategy with division into subsets I-VI based on CD45RA and FOXP3 as indicated. (B) Comparison of CD4+T cells between ATG and PTCy groups in each subset. Statistical difference by two tailed t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. .

Figure 5.

The association between Treg cells subset and clinical outcomes. (A) Naïve Treg cells. (B) Effector Treg cells. (C) Non-suppressive Treg cells. (D) Subset IV. (E) Conventional CD4+T cells. (F) Naïve CD4+T cells. Statistical difference by two tailed t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

The association between Treg cells subset and clinical outcomes. (A) Naïve Treg cells. (B) Effector Treg cells. (C) Non-suppressive Treg cells. (D) Subset IV. (E) Conventional CD4+T cells. (F) Naïve CD4+T cells. Statistical difference by two tailed t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 6.

Spearman correlation analysis between each subset and the severity of acute GVHD. (A) Naïve Treg cells. (B) Effector Treg cells. (C) Non-suppressive Treg cells. (D) Subset IV. (E) Conventional CD4+T cells. (F) Naïve CD4+T cells. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) and p value were indicated.

Figure 6.

Spearman correlation analysis between each subset and the severity of acute GVHD. (A) Naïve Treg cells. (B) Effector Treg cells. (C) Non-suppressive Treg cells. (D) Subset IV. (E) Conventional CD4+T cells. (F) Naïve CD4+T cells. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) and p value were indicated.

Figure 7.

Inflammatory cytokine levels between ATG and PTCy group. (A) IL-6. (B) IFN-γ. (C) TNF-α. Statistical difference by two tailed t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 7.

Inflammatory cytokine levels between ATG and PTCy group. (A) IL-6. (B) IFN-γ. (C) TNF-α. Statistical difference by two tailed t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics in patients with allogeneic-HSCT between ATG and PTCy group (n=45).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics in patients with allogeneic-HSCT between ATG and PTCy group (n=45).

| |

ATG (n=28) |

PTCy (n=17) |

p-value |

| Median Age, year (range) |

52.5 (21-66) |

57 (29-71) |

0.060 |

| Gender, M:F |

16 : 12 |

11 : 6 |

1.000 |

| Type of diseases |

|

|

0.824 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia |

18 (64.3%) |

10 (58.8%) |

|

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

6 (21.4%) |

3 (17.6%) |

|

| Myelodysplastic syndrome |

4 (14.3%) |

4 (23.5%) |

|

| Type of donors |

|

|

<0.001 |

| HLA-matched sibling |

16 (57.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

| HLA-matched unrelated |

12 (42.9%) |

5 (29.4%) |

|

| Haplo-identical |

0 (0.0%) |

12 (70.6%) |

|

| Disease status at transplant |

|

|

0.830 |

| 1st CR |

18 (64.3%) |

11 (64.7%) |

|

| 2nd CR |

4 (14.3%) |

1 (5.9%) |

|

| MDS |

4 (14.3%) |

4 (23.5%) |

|

| Persistent |

2 (7.1%) |

1 (5.9%) |

|

| Poor risk* |

15 (53.6%) |

7 (43.8%) |

0.755 |

| HCT-CI |

|

|

0.434 |

| 0 |

20 (71.5%) |

13 (76.5%) |

|

| 1-2 |

8 (28.6%) |

3 (17.6%) |

|

| 3- |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (5.9%) |

|

| CMV reactivation |

8 (28.6%) |

13 (76.5%) |

0.002 |

| Acute GVHD (evaluable) |

|

|

0.215 |

| Grade 0-I |

23 (82.1%) |

11 (37.6%) |

|

| Grade II-IV |

5 (17.9%) |

6 (35.3%) |

|

| Stem cell source |

|

|

- |

| PB |

28 (100%) |

17 (100%) |

|

| BM |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

| Conditioning regimen |

|

|

0.101 |

| MAC |

22 (78.6%) |

9 (52.9%) |

|

| RIC |

6 (21.4%) |

8 (47.1%) |

|

| Cell count, median (range) |

|

|

|

| TNC count (x108 cells/kg) |

11.97 (6.86-22.51) |

12.08 (6.87-20.60) |

0.926 |

| CD34+ cell (x106cells/kg) |

7.94 (2.60-22.17) |

11.11 (2.17-36.00) |

0.216 |

| Median F/U duration, month (range) |

16.8 (3.8-23.3) |

11.5 (1.8-53.8) |

0.101 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).