Submitted:

17 April 2024

Posted:

18 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patient-, Disease-, and Transplantation-Related Characteristics

3.2. Acute and Chronic GvHD

3.3. Infection-Related Mortality and Viral Infections

3.4. Survival Outcomes

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wingard, J.R.; Majhail, N.S.; Brazauskas, R.; Wang, Z.; Sobocinski, K.A.; Jacobsohn, D.; Sorror, M.L.; Horowitz, M.M.; Bolwell, B.; Rizzo, J.D.; et al. Long-Term Survival and Late Deaths after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2011, 29, 2230–2239. [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.J.; Counts, G.W.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Lee, S.J.; Sanders, J.E.; Deeg, H.J.; Flowers, M.E.D.; Syrjala, K.L.; Hansen, J.A.; Storb, R.F.; et al. Life Expectancy in Patients Surviving More than 5 Years after Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28, 1011–1016. [CrossRef]

- Pidala, J.; Kurland, B.; Chai, X.; Majhail, N.; Weisdorf, D.J.; Pavletic, S.; Cutler, C.; Jacobsohn, D.; Palmer, J.; Arai, S.; et al. Patient-Reported Quality of Life Is Associated with Severity of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease as Measured by NIH Criteria: Report on Baseline Data from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood 2011, 117, 4651–4657. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, B.; Williams, K.M. Controversies and Expectations for the Prevention of GVHD: A Biological and Clinical Perspective. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Arai, S.; Arora, M.; Wang, T.; Spellman, S.R.; He, W.; Couriel, D.R.; Urbano-Ispizua, A.; Cutler, C.S.; Bacigalupo, A.A.; Battiwalla, M.; et al. Increasing Incidence of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease in Allogeneic Transplantation: A Report from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015, 21, 266–274. [CrossRef]

- Flowers, M.E.D.; Inamoto, Y.; Carpenter, P.A.; Lee, S.J.; Kiem, H.P.; Petersdorf, E.W.; Pereira, S.E.; Nash, R.A.; Mielcarek, M.; Fero, M.L.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Risk Factors for Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease and for Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease According to National Institutes of Health Consensus Criteria. Blood 2011, 117, 3214–3219. [CrossRef]

- Anasetti, C.; Logan, B.R.; Lee, S.J.; Waller, E.K.; Weisdorf, D.J.; Wingard, J.R.; Cutler, C.S.; Westervelt, P.; Woolfrey, A.; Couban, S.; et al. Peripheral-Blood Stem Cells versus Bone Marrow from Unrelated Donors. N Engl J Med 2012, 367, 1487–1496. [CrossRef]

- Thomas E.; Storb R.; Clift R.A.; et al: Bone-marrow transplantation (first of two parts). N Engl J Med 292:832-843, 1975.

- Storb R.; Deeg H.J.; Whitehead J.; et al: Methotrexate and cyclosporine compared with cyclosporine alone for prophylaxis of acute graft versus host disease after marrow transplantation for leukemia. N Engl J Med 314:729-735, 1986.

- Hahn T.; McCarthy P.L. Jr; Zhang M.J.; et al: Risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease after human leukocyte antigen-identical sibling transplants for adults with leukemia. J Clin Oncol 26:5728-5734, 2008.

- Lai Y.R.; Chen Y.H.; Hu D.M.; et al: Multicenter phase II study of a combination of cyclosporine a, methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil for GVHD prophylaxis: Results of the Chinese Bone Marrow Transplant Cooperative Group (CBMTCG). J Hematol Oncol 7:59, 2014.

- Mohty M.: Mechanisms of action of antithymocyte globulin: T-cell depletion and beyond. Leukemia 21:1387-1394, 2007 .

- Ruutu, T.; Van Biezen, A.; Hertenstein, B.; Henseler, A.; Garderet, L.; Passweg, J.; Mohty, M.; Sureda, A.; Niederwieser, D.; Gratwohl, A.; et al. Prophylaxis and Treatment of GVHD after Allogeneic Haematopoietic SCT: A Survey of Centre Strategies by the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2012, 47, 1459–1464. [CrossRef]

- Baron, F.; Mohty, M.; Blaise, D.; Socié, G.; Labopin, M.; Esteve, J.; Ciceri, F.; Giebel, S.; Gorin, N.C.; Savani, B.N.; et al. Anti-Thymocyte Globulin as Graft-versus-Host Disease Prevention in the Setting of Allogeneic Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation: A Review from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica 2017, 102, 224–234. [CrossRef]

- Popow, I.; Leitner, J.; Majdic, O.; J. Kovarik, J.; D. Saemann, M.; Zlabinger, G.J.; Steinberger, P. Assessment of Batch to Batch Variation in Polyclonal Antithymocyte Globulin Preparations. Transplantation 2012, 93, 32–40. [CrossRef]

- Popow, I.; Leitner, J.; Grabmeier-Pfistershammer, K.; Majdic, O.; Zlabinger, G.J.; Kundi, M.; Steinberger, P. A Comprehensive and Quantitative Analysis of the Major Specificities in Rabbit Antithymocyte Globulin Preparations. Am J Transplant 2013, 13, 3103–3113. [CrossRef]

- Servais, S.; Menten-Dedoyart, C.; Beguin, Y.; Seidel, L.; Gothot, A.; Daulne, C.; Willems, E.; Delens, L.; Humblet-Baron, S.; Hannon, M.; et al. Impact of Pre-Transplant Anti-T Cell Globulin (ATG) on Immune Recovery after Myeloablative Allogeneic Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation. PLoS One 2015, 10. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, M.; Dhadda, M.; Hoegh-Petersen, M.; Liu, Y.; Hagel, L.M.; Podgorny, P.; Ugarte-Torres, A.; Khan, F.M.; Luider, J.; Auer-Grzesiak, I.; et al. Immune Reconstitution after Anti-Thymocyte Globulin-Conditioned Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Cytotherapy 2012, 14, 1258–1275. [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, F.; Rubio, M.T.; Bacigalupo, A.; Boelens, J.J.; Finke, J.; Greinix, H.; Mohty, M.; Nagler, A.; Passweg, J.; Rambaldi, A.; et al. Rabbit ATG/ATLG in Preventing Graft-versus-Host Disease after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: Consensus-Based Recommendations by an International Expert Panel. Bone Marrow Transplant 2020, 55, 1093–1102. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson K, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Lee MB, Rimm AA, Bortin MM. Consensus among bone marrow transplanters for diagnosis, grading and treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. Bone Marrow Transplant.1989;4:247-254.

- Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825-828.

- Lee, S.J.; Logan, B.; Westervelt, P.; Cutler, C.; Woolfrey, A.; Khan, S.P.; Waller, E.K.; Maziarz, R.T.; Wu, J.; Shaw, B.E.; et al. Comparison of Patient-Reported Outcomes in 5-Year Survivors Who Received Bone Marrow vs Peripheral Blood Unrelated Donor Transplantation: Long-Term Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1583–1589.

- Polverelli, N.; Malagola, M.; Turra, A.; Skert, C.; Perucca, S.; Chiarini, M.; Cattina, F.; Rambaldi, B.; Cancelli, V.; Morello, E.; et al. Comparative Study on ATG-Thymoglobulin versus ATG-Fresenius for the Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD) Prophylaxis in Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation from Matched Unrelated Donor: A Single-Centre Experience over the Contemporary Years. Leuk. Lymphoma 2018, 59, 2700–2705.

- Oostenbrink, L.V.E.; Jol-Van Der Zijde, C.M.; Kielsen, K.; Jansen-Hoogendijk, A.M.; Ifversen, M.; Müller, K.G.; Lankester, A.C.; Van Halteren, A.G.S.; Bredius, R.G.M.; Schilham, M.W.; et al. Differential Elimination of Anti-Thymocyte Globulin of Fresenius and Genzyme Impacts T-Cell Reconstitution After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 315.

- Liu, L.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, W.; Lei, M.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Q.; Qiu, H.; Tang, X.; Han, Y.; et al. Comparison of 2 Different Rabbit Anti-Thymocyte Globulin (r-ATG) Preparations: Thymocyte r-ATG versus T Lymphoblast Cell Line r-ATG in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Acquired Severe Aplastic Anemia: Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2021, 27, 186.e1–186.e3.

- Wang, L.; Kong, P.; Zhang, C.; Gao, L.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Gao, S.; Chen, T.; Liu, H.; Yao, H.; et al. Outcomes of Patients with Hematological Malignancies Who Undergo Unrelated Donor Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation with ATG-Fresenius versus ATG-Genzyme. Ann. Hematol. 2023, 102, 1–11.

- Butera, S.; Cerrano, M.; Brunello, L.; Dellacasa, C.M.; Faraci, D.G.; Vassallo, S.; Mordini, N.; Sorasio, R.; Zallio, F.; Busca, A.; et al. Impact of Anti-Thymocyte Globulin Dose for Graft-versus-Host Disease Prophylaxis in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation from Matched Unrelated Donors: A Multicenter Experience. Ann. Hematol. 2021, 100, 1837–1847.

- Gaber AO et al (2010) Rabbit antithymocyte globulin (thymoglobulin): 25 years and new frontiers in solid organ transplantation and haematology. Drugs 70(6):691–732.

- Gagelmann, N.; Ayuk, F.; Wolschke, C.; Kröger, N. Comparison of Different Rabbit Anti-Thymocyte Globulin Formulations in Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: Systematic Literature Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017, 23, 2184–2191.

- Luo X-H et al (2021) CMV infection and CMV-specific immune reconstitution following haploidentical stem cell transplantation: an update. Front Immunol 12:732826.

- Marty, F.M.; Ljungman, P.; Chemaly, R.F.; Maertens, J.; Dadwal, S.S.; Duarte, R.F.; Haider, S.; Ullmann, A.J.; Katayama, Y.; Brown, J.; et al. Letermovir Prophylaxis for Cytomegalovirus in Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2433–2444.

- Schmidt-Hieber, M.; Schwarck, S.; Stroux, A.; Ganepola, S.; Reinke, P.; Thiel, E.; Uharek, L.; Blau, I.W. Immune Reconstitution and Cytomegalovirus Infection after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: The Important Impact of in Vivo T Cell Depletion. Int. J. Hematol. 2010, 91, 877–885.

- Russo D, Schmitt M, Pilorge S, Stelljes M, Kawakita T, Teal VL, Haber B, Bopp C, Dadwal SS, Badshah C. Efficacy and safety of extended duration letermovir prophylaxis in recipients of haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation at risk of cytomegalovirus infection: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2024 Feb;11(2):e127-e135.

| ATG-T (n = 40) |

ATG-G (n = 47) |

P value | |||

| Median age, y (range) | 45 (35-53) | 55 (39-62) | 0.065 | ||

| Age, n (%) | 0.003 | ||||

| <55 years | 33 | 82.5% | 24 | 51.1% | |

| ≥55 years | 7 | 17.5% | 23 | 48.9% | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.832 | ||||

| Male | 23 | 57.5% | 27 | 57.4% | |

| Female | 17 | 42.5% | 20 | 42.6% | |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.524 | ||||

| AML+MDS | 15 | 37.5% | 25 | 53.2% | |

| ALL | 10 | 25.0% | 8 | 17.0% | |

| HL+NHL+MM | 8 | 20.0% | 7 | 14.9% | |

| OMF, CML, SAA et al. | 7 | 17.5% | 7 | 14.9% | |

| The advancement of the disease, n (%) | 0.425 | ||||

| Remission | 23 | 57.5% | 32 | 68.1% | |

| Active | 17 | 42.5% | 15 | 39.1% | |

| ELN cytogenetic risk, n (%) | 0.246 | ||||

| Favorable | 3 | 7.5% | 11 | 23.4% | |

| Intermediate | 9 | 22.5% | 9 | 19.2% | |

| Adverse | 5 | 12.5% | 4 | 8.5% | |

| N/A | 23 | 57.5% | 23 | 48.9% | |

| Complete remission number, n (%) | 0.147 | ||||

| 0 | 18 | 45.0% | 14 | 29.8% | |

| 1 | 16 | 40.0% | 27 | 57.4% | |

| 2 | 6 | 15.0% | 3 | 6.4% | |

| 3 | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 4.3% | |

| 4 | 0 | 2.2% | 1 | 2.1% | |

| CMV IgG, n (%) | 0.936 | ||||

| Negative | 7 | 17.5% | 9 | 19.2% | |

| Positive | 33 | 82.5% | 38 | 80.8% | |

| ATG-T (n = 40) |

ATG-G (n = 47) |

P value | |||

| Median donor age, years (range) | 30 (24-39) | 33 (25-40) | 0.399 | ||

| Donor age, n (%) | 0.849 | ||||

| <40 years | 30 | 75.0% | 35 | 74.5% | |

| ≥40 years | 10 | 25.0% | 12 | 25.5% | |

| Donor sex, n (%) | 0.145 | ||||

| Male | 11 | 27.5% | 6 | 12.8% | |

| Female | 29 | 72.5% | 41 | 87.2% | |

| Locus with a mismatch, n (%) | 0.221 | ||||

| A | 13 | 44.8% | 1 | 10.0% | |

| B | 2 | 6.9% | 2 | 20.0% | |

| C | 10 | 34.5% | 5 | 50.0% | |

| DQ | 4 | 13.8% | 2 | 20.0% | |

| Donor status CMV IgG , n (%) | 0.954 | ||||

| Negative | 16 | 40.0% | 18 | 38.3% | |

| Positive | 24 | 60.0% | 29 | 61.7% | |

| CMV prophylaxis, n (%) | 0.004 | ||||

| Acyclovir | 36 | 90.0% | 27 | 58.7% | |

| Valgancyclovir | 1 | 2.5% | 4 | 8.7% | |

| Acyclovir+ Valgancyclovir | 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 21.7% | |

| Letermovir | 3 | 7.5% | 5 | 10.9% | |

| Conditioning regimen, n (%) | 0.014 | ||||

| RIC | 4 | 10.0% | 15 | 31.9% | |

| MAC | 33 | 82.5% | 25 | 53.2% | |

| NMA | 3 | 7.5% | 7 | 14.9% | |

| Median CD34+ count, x106/kg (range) | 8.1 [5.1-9.6] | 7.4 [5.5-9.9] | 0.810 | ||

| ATG-T (n = 40) |

ATG-G (n = 47) |

P value | |||

| Acute GvHD, n (%) | 0.084 | ||||

| Yes | 26 | 65.0% | 21 | 44.7% | |

| No | 14 | 35.0% | 26 | 55.3% | |

| Degree of acute GvHD, n (%) | 0.103 | ||||

| 0 | 14 | 35.0% | 27 | 57.4% | |

| 1 or 2 | 18 | 45.0% | 15 | 31.9% | |

| 3 or 4 | 8 | 20.0% | 5 | 10.6% | |

| Deegree of acute GvHD, n (%) | 0.308 | ||||

| 0 or 1 | 23 | 57.5% | 32 | 68.1% | |

| 2 or more | 17 | 42.5% | 15 | 31.9% | |

| Median time of onset of acute GVHD, days (range) | 24 [17-36] | 29 [19-49] | 0.366 | ||

| Chronic GvHD, n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 7.5% | 18 | 38.3% | |

| No | 37 | 92.5% | 29 | 61.7% | |

| ATG-T (n = 40) |

ATG-G (n = 47) |

P value | |||

| CMV reactivation, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 28 | 70.0% | 15 | 31.9% | |

| No | 12 | 30.0% | 32 | 68.1% | |

| Median time between transplant and CMV reactivation, days (range) | 35 [26-51] | 69 [33-127] | 0.057 | ||

| Time between transplant and CMV, n (%) | n = 27 | n = 15 | 0.008 | ||

| <61 days | 21 | 77.8% | 5 | 33.3% | |

| ≥61 days | 6 | 22.2% | 10 | 66.7% | |

| Median CMV copy number (PCR), count (range) | 1000 (0-18000) |

0 (0-634) |

0.004 | ||

| CMV copy (CR), n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| <400 copies | 14 | 35.0% | 35 | 74.5% | |

| ≥400 copies | 26 | 65.0% | 12 | 25.5% | |

| Symptoms of CMV disease, n (%) | n = 35 | n = 16 | 0.005 | ||

| Yes | 5 | 14.3% | 9 | 56.2% | |

| No | 30 | 85.7% | 7 | 43.8% | |

| Disease manifestation, n (%) | 0.367 | ||||

| No | 38 | 96.0% | 37 | 80.4% | |

| Pneumonia CMV | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 4.3% | |

| Hepatitis | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.2% | |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 | 1.2% | 4 | 8.7% | |

| Pancytopenia | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.2% | |

| Klebsiella | 1 | 1.2% | 1 | 2.2% | |

| Other viral reactivations: | 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 6 | 15.0% | 31 | 66.0% | |

| No | 34 | 85.0% | 16 | 34.0% | |

| EBV | 4 | 10.0% | 19 | 40.4% | 0.001 |

| BKV | 2 | 5.0% | 14 | 29.8% | 0.004 |

| JCV | 1 | 2.5% | 10 | 21.3% | 0.010 |

| HHV6 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.1% | 1.000 |

| Others | 1 | 2.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.460 |

| ATG-T (n = 40) |

ATG-G (n = 47) |

P value | |

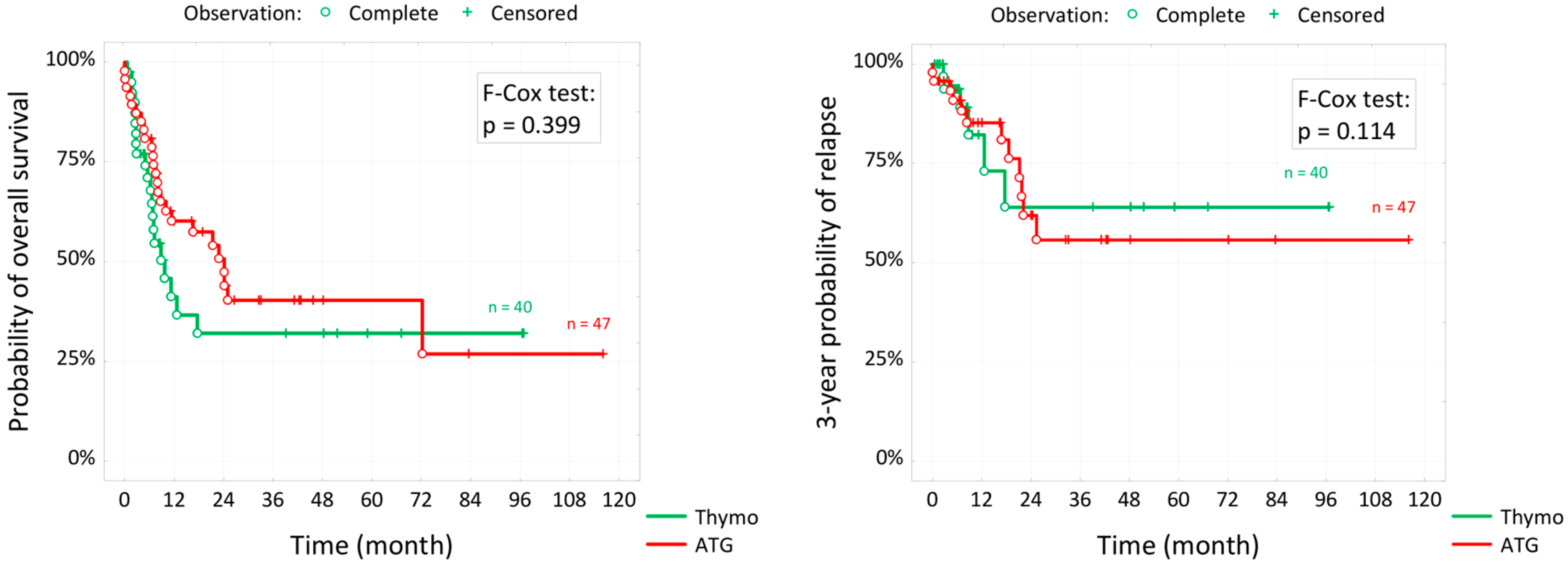

| Median months of follow-up (interquartile range)* | 8 [5-52] | 22 [12-42] | 0.110 |

| 3-year probability of relapse(t=3) | 63.9% | 55.7% | 0.438 |

| 5-years overall survival OS(t=5) | 32.0% | 40.3% | 0.423 |

| Median survival function** | 8.9 months | 23.1 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).