Submitted:

21 August 2024

Posted:

22 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Druker, B.J.; Talpaz, M.; Resta, D.J.; Peng, B.; Buchdunger, E.; Ford, J.M.; Lydon, N.B.; Kantarjian, H.; Capdeville, R.; Ohno-Jones, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of a Specific Inhibitor of the BCR-ABL Tyrosine Kinase in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, S.G.; Guilhot, F.; Larson, R.A.; Gathmann, I.; Baccarani, M.; Cervantes, F.; Cornelissen, J.J.; Fischer, T.; Hochhaus, A.; Hughes, T.; et al. Imatinib Compared with Interferon and Low-Dose Cytarabine for Newly Diagnosed Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.P.; Guilhot, F.; Cortes, J.E.; Schiffer, C.A.; le Coutre, P.; Brümmendorf, T.H.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Hochhaus, A.; Rousselot, P.; Mohamed, H.; et al. Long-Term Outcome with Dasatinib after Imatinib Failure in Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Follow-up of a Phase 3 Study. Blood 2014, 123, 2317–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles, F.J.; le Coutre, P.D.; Pinilla-Ibarz, J.; Larson, R.A.; Gattermann, N.; Ottmann, O.G.; Hochhaus, A.; Radich, J.P.; Saglio, G.; Hughes, T.P.; et al. Nilotinib in Imatinib-Resistant or Imatinib-Intolerant Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in Chronic Phase: 48-Month Follow-up Results of a Phase II Study. Leukemia 2013, 27, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochhaus, A.; Saglio, G.; Hughes, T.P.; Larson, R.A.; Kim, D.-W.; Issaragrisil, S.; le Coutre, P.D.; Etienne, G.; Dorlhiac-Llacer, P.E.; Clark, R.E.; et al. Long-Term Benefits and Risks of Frontline Nilotinib vs Imatinib for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in Chronic Phase: 5-Year Update of the Randomized ENESTnd Trial. Leukemia 2016, 30, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, J.E.; Saglio, G.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Baccarani, M.; Mayer, J.; Boqué, C.; Shah, N.P.; Chuah, C.; Casanova, L.; Bradley-Garelik, B.; et al. Final 5-Year Study Results of DASISION: The Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naïve Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2333–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarani, M.; Deininger, M.W.; Rosti, G.; Hochhaus, A.; Soverini, S.; Apperley, J.F.; Cervantes, F.; Clark, R.E.; Cortes, J.E.; Guilhot, F.; et al. European LeukemiaNet Recommendations for the Management of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: 2013. Blood 2013, 122, 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.J.; Ito, S. The Role of Stem Cell Transplantation for Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia in the 21st Century. Blood 2015, 125, 3230–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübking, A.; Dreimane, A.; Sandin, F.; Isaksson, C.; Märkevärn, B.; Brune, M.; Ljungman, P.; Lenhoff, S.; Stenke, L.; Höglund, M.; et al. Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in the TKI Era: Population-Based Data from the Swedish CML Registry. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019, 54, 1764–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, T.I.; Radich, J.P.; Deininger, M.W.; Apperley, J.F.; Hughes, T.P.; Harrison, C.J.; Gambacorti-Passerini, C.; Saglio, G.; Cortes, J.; Daley, G.Q. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Reminiscences and Dreams. Haematologica 2016, 101, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratwohl, A.; Brand, R.; Apperley, J.; Crawley, C.; Ruutu, T.; Corradini, P.; Carreras, E.; Devergie, A.; Guglielmi, C.; Kolb, H.-J.; et al. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in Europe 2006: Transplant Activity, Long-Term Data and Current Results. An Analysis by the Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Haematologica 2006, 91, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dazzi, F.; Szydlo, R.M.; Craddock, C.; Cross, N.C.; Kaeda, J.; Chase, A.; Olavarria, E.; van Rhee, F.; Kanfer, E.; Apperley, J.F.; et al. Comparison of Single-Dose and Escalating-Dose Regimens of Donor Lymphocyte Infusion for Relapse after Allografting for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2000, 95, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlu, J.; Szydlo, R.M.; Goldman, J.M.; Apperley, J.F. Three Decades of Transplantation for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: What Have We Learned? Blood 2011, 117, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innes, A.J.; Milojkovic, D.; Apperley, J.F. Allogeneic Transplantation for CML in the TKI Era: Striking the Right Balance. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratwohl, A.; Heim, D. Current Role of Stem Cell Transplantation in Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2009, 22, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passweg, J.R.; Baldomero, H.; Gratwohl, A.; Bregni, M.; Cesaro, S.; Dreger, P.; de Witte, T.; Farge-Bancel, D.; Gaspar, B.; Marsh, J.; et al. The EBMT Activity Survey: 1990-2010. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012, 47, 906–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, E.; Kantarjian, H. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: 2025 Update on Diagnosis, Therapy, and Monitoring. Am. J. Hematol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, E.; Cortes, J.; Santos, F.P.S.; Jones, D.; O’Brien, S.; Rondon, G.; Popat, U.; Giralt, S.; Kebriaei, P.; Jones, R.B.; et al. Results of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Patients Who Failed Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors after Developing BCR-ABL1 Kinase Domain Mutations. Blood 2011, 117, 3641–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolini, F.E.; Basak, G.W.; Kim, D.-W.; Olavarria, E.; Pinilla-Ibarz, J.; Apperley, J.F.; Hughes, T.; Niederwieser, D.; Mauro, M.J.; Chuah, C.; et al. Overall Survival with Ponatinib versus Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation in Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Leukemias with the T315I Mutation. Cancer 2017, 123, 2875–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Kaeda, J.; Branford, S.; Rudzki, Z.; Hochhaus, A.; Hensley, M.L.; Gathmann, I.; Bolton, A.E.; van Hoomissen, I.C.; Goldman, J.M.; et al. Frequency of Major Molecular Responses to Imatinib or Interferon Alfa plus Cytarabine in Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian, H.; Shah, N.P.; Hochhaus, A.; Cortes, J.; Shah, S.; Ayala, M.; Moiraghi, B.; Shen, Z.; Mayer, J.; Pasquini, R.; et al. Dasatinib versus Imatinib in Newly Diagnosed Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2260–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saglio, G.; Kim, D.-W.; Issaragrisil, S.; le Coutre, P.; Etienne, G.; Lobo, C.; Pasquini, R.; Clark, R.E.; Hochhaus, A.; Hughes, T.P.; et al. Nilotinib versus Imatinib for Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2251–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saussele, S.; Richter, J.; Guilhot, J.; Gruber, F.X.; Hjorth-Hansen, H.; Almeida, A.; Janssen, J.J.W.M.; Mayer, J.; Koskenvesa, P.; Panayiotidis, P.; et al. Discontinuation of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy in Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia (EURO-SKI): A Prespecified Interim Analysis of a Prospective, Multicentre, Non-Randomised, Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaucha, J.M.; Prejzner, W.; Giebel, S.; Gooley, T.A.; Szatkowski, D.; Kałwak, K.; Wojnar, J.; Kruzel, T.; Balon, J.; Hołowiecki, J.; et al. Imatinib Therapy prior to Myeloablative Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005, 36, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deininger, M.; Schleuning, M.; Greinix, H.; Sayer, H.G.; Fischer, T.; Martinez, J.; Maziarz, R.; Olavarria, E.; Verdonck, L.; Schaefer, K.; et al. The Effect of Prior Exposure to Imatinib on Transplant-Related Mortality. Haematologica 2006, 91, 452–459. [Google Scholar]

- Oehler, V.G.; Gooley, T.; Snyder, D.S.; Johnston, L.; Lin, A.; Cummings, C.C.; Chu, S.; Bhatia, R.; Forman, S.J.; Negrin, R.S.; et al. The Effects of Imatinib Mesylate Treatment before Allogeneic Transplantation for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2007, 109, 1782–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Kukreja, M.; Wang, T.; Giralt, S.A.; Szer, J.; Arora, M.; Woolfrey, A.E.; Cervantes, F.; Champlin, R.E.; Gale, R.P.; et al. Impact of Prior Imatinib Mesylate on the Outcome of Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2008, 112, 3500–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saussele, S.; Lauseker, M.; Gratwohl, A.; Beelen, D.W.; Bunjes, D.; Schwerdtfeger, R.; Kolb, H.-J.; Ho, A.D.; Falge, C.; Holler, E.; et al. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (allo SCT) for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in the Imatinib Era: Evaluation of Its Impact within a Subgroup of the Randomized German CML Study IV. Blood 2010, 115, 1880–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, E.; Cortes, J.; Kantarjian, H.; Giralt, S.; Andersson, B.S.; Giles, F.; Shpall, E.; Kebriaei, P.; Champlin, R.; de Lima, M. Novel Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy before Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: No Evidence for Increased Transplant-Related Toxicity. Cancer 2007, 110, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoni, A.; Leiba, M.; Schleuning, M.; Martineau, G.; Renaud, M.; Koren-Michowitz, M.; Ribakovski, E.; le Coutre, P.; Arnold, R.; Guilhot, F.; et al. Prior Treatment with the Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Dasatinib and Nilotinib Allows Stem Cell Transplantation (SCT) in a Less Advanced Disease Phase and Does Not Increase SCT Toxicity in Patients with Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia and Philadelphia Positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Leukemia 2009, 23, 190–194. [Google Scholar]

- Breccia, M.; Palandri, F.; Iori, A.P.; Colaci, E.; Latagliata, R.; Castagnetti, F.; Torelli, G.F.; Usai, S.; Valle, V.; Martinelli, G.; et al. Second-Generation Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors before Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Resistant to Imatinib. Leuk. Res. 2010, 34, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekarska, A.; Gil, L.; Prejzner, W.; Wiśniewski, P.; Leszczyńska, A.; Gniot, M.; Komarnicki, M.; Hellmann, A. Pretransplantation Use of the Second-Generation Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Has No Negative Impact on the HCT Outcome. Ann. Hematol. 2015, 94, 1891–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saidu, N.E.B.; Bonini, C.; Dickinson, A.; Grce, M.; Inngjerdingen, M.; Koehl, U.; Toubert, A.; Zeiser, R.; Galimberti, S. New Approaches for the Treatment of Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease: Current Status and Future Directions. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 578314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Ortega, I.; Parody, R.; Servitje, O.; Muniesa, C.; Arnan, M.; Patino, B.; Sureda, A.; Duarte, R.F. Imatinib and Dasatinib as Salvage Therapy for Sclerotic Chronic Graft-vs-Host Disease. Croat. Med. J. 2016, 57, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ortega, I.; Servitje, O.; Arnan, M.; Ortí, G.; Peralta, T.; Manresa, F.; Duarte, R.F. Dasatinib as Salvage Therapy for Steroid Refractory and Imatinib Resistant or Intolerant Sclerotic Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012, 18, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srour, M.; Alsuliman, T.; Labreuche, J.; Bulabois, C.-E.; Chevallier, P.; Daguindau, E.; Forcade, E.; François, S.; Guillerm, G.; Coiteux, V.; et al. Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety as Salvage Treatment Following Imatinib Intolerance And/or Inefficacy in Steroid Refractory Chronic Graft-versus-Host-Disease (SR-cGVHD): A Prospective, Multicenter, Phase II Study on Behalf of the Francophone Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (SFGM-TC). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2023, 58, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olivieri, A.; Mancini, G.; Olivieri, J.; Marinelli Busilacchi, E.; Cimminiello, M.; Pascale, S.P.; Nuccorini, R.; Patriarca, F.; Corradini, P.; Bacigalupo, A.; et al. Nilotinib in Steroid-Refractory cGVHD: Prospective Parallel Evaluation of Response, according to NIH Criteria and Exploratory Response Criteria (GITMO Criteria). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020, 55, 2077–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. Available online: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Jakavi. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/jakavi (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Moslehi, J.J.; Deininger, M. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor-Associated Cardiovascular Toxicity in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 4210–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lavallade, H.; Khoder, A.; Hart, M.; Sarvaria, A.; Sekine, T.; Alsuliman, A.; Mielke, S.; Bazeos, A.; Stringaris, K.; Ali, S.; et al. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Impair B-Cell Immune Responses in CML through off-Target Inhibition of Kinases Important for Cell Signaling. Blood 2013, 122, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Nakamae, H.; Katayama, T.; Nakane, T.; Koh, H.; Nakamae, M.; Hirose, A.; Hagihara, K.; Terada, Y.; Nakao, Y.; et al. Different Immunoprofiles in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Treated with Imatinib, Nilotinib or Dasatinib. Leuk. Lymphoma 2012, 53, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarani, M.; Saglio, G.; Goldman, J.; Hochhaus, A.; Simonsson, B.; Appelbaum, F.; Apperley, J.; Cervantes, F.; Cortes, J.; Deininger, M.; et al. Evolving Concepts in the Management of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Recommendations from an Expert Panel on Behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 2006, 108, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarani, M.; Cortes, J.; Pane, F.; Niederwieser, D.; Saglio, G.; Apperley, J.; Cervantes, F.; Deininger, M.; Gratwohl, A.; Guilhot, F.; et al. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: An Update of Concepts and Management Recommendations of European LeukemiaNet. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 6041–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przepiorka, D.; Weisdorf, D.; Martin, P.; Klingemann, H.G.; Beatty, P.; Hows, J.; Thomas, E.D. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995, 15, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harris, A.C.; Young, R.; Devine, S.; Hogan, W.J.; Ayuk, F.; Bunworasate, U.; Chanswangphuwana, C.; Efebera, Y.A.; Holler, E.; Litzow, M.; et al. International, Multicenter Standardization of Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease Clinical Data Collection: A Report from the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016, 22, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipovich, A.H.; Weisdorf, D.; Pavletic, S.; Socie, G.; Wingard, J.R.; Lee, S.J.; Martin, P.; Chien, J.; Przepiorka, D.; Couriel, D.; et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005, 11, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, H.M.; Sullivan, K.M.; Weiden, P.L.; McDonald, G.B.; Striker, G.E.; Sale, G.E.; Hackman, R.; Tsoi, M.S.; Storb, R.; Thomas, E.D. Chronic Graft-versus-Host Syndrome in Man. A Long-Term Clinicopathologic Study of 20 Seattle Patients. Am. J. Med. 1980, 69, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, V.S.; Baccarani, M.; Hasford, J.; Castagnetti, F.; Di Raimondo, F.; Casado, L.F.; Turkina, A.; Zackova, D.; Ossenkoppele, G.; Zaritskey, A.; et al. Treatment and Outcome of 2904 CML Patients from the EUTOS Population-Based Registry. Leukemia 2017, 31, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, J.; Sasaki, K.; Issa, G.C.; Lipton, J.H.; Radich, J.P.; Jabbour, E.; Kantarjian, H.M. Management of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in 2023 - Common Ground and Common Sense. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Kantarjian, H.; Alattar, M.L.; Jabbour, E.; Sasaki, K.; Nogueras Gonzalez, G.; Dellasala, S.; Pierce, S.; Verstovsek, S.; Wierda, W.; et al. Long-Term Molecular and Cytogenetic Response and Survival Outcomes with Imatinib 400 Mg, Imatinib 800 Mg, Dasatinib, and Nilotinib in Patients with Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia: Retrospective Analysis of Patient Data from Five Clinical Trials. Lancet Haematol 2015, 2, e118–e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, H.; Björkholm, M.; Dickman, P.W.; Höglund, M.; Lambert, P.C.; Andersson, T.M.-L. Life Expectancy of Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Approaches the Life Expectancy of the General Population. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2851–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehlmann, R.; Lauseker, M.; Saußele, S.; Pfirrmann, M.; Krause, S.; Kolb, H.J.; Neubauer, A.; Hossfeld, D.K.; Nerl, C.; Gratwohl, A.; et al. Assessment of Imatinib as First-Line Treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: 10-Year Survival Results of the Randomized CML Study IV and Impact of Non-CML Determinants. Leukemia 2017, 31, 2398–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochhaus, A.; Larson, R.A.; Guilhot, F.; Radich, J.P.; Branford, S.; Hughes, T.P.; Baccarani, M.; Deininger, M.W.; Cervantes, F.; Fujihara, S.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Imatinib Treatment for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breccia, M. Imatinib Improved the Overall Survival of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Therapeutic Goal Has Been Reached. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 19, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, C.C.H.M.; van Klaveren, D.; Ector, G.I.C.G.; Posthuma, E.F.M.; Visser, O.; Westerweel, P.E.; Janssen, J.J.W.M.; Blijlevens, N.M.A.; Dinmohamed, A.G. The Evolution of the Loss of Life Expectancy in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia: A Population-Based Study in the Netherlands, 1989-2018. Br. J. Haematol. 2022, 196, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molica, M.; Naqvi, K.; Cortes, J.E.; Paul, S.; Kadia, T.M.; Breccia, M.; Kantarjian, H.; Jabbour, E.J. Treatment-Free Remission in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 17, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Radich, J.P.; Hochhaus, A.; Masszi, T.; Hellmann, A.; Stentoft, J.; Casares, M.T.G.; García-Gutiérrez, J.V.; Conneally, E.; le Coutre, P.D.; Gattermann, N.; et al. Treatment-Free Remission Following Frontline Nilotinib in Patients with Chronic Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: 5-Year Update of the ENESTfreedom Trial. Leukemia 2021, 35, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.P.; García-Gutiérrez, V.; Jiménez-Velasco, A.; Larson, S.; Saussele, S.; Rea, D.; Mahon, F.-X.; Levy, M.Y.; Gómez-Casares, M.T.; Pane, F.; et al. Dasatinib Discontinuation in Patients with Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia and Stable Deep Molecular Response: The DASFREE Study. Leuk. Lymphoma 2020, 61, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugliotta, G.; Castagnetti, F.; Breccia, M.; Levato, L.; Intermesoli, T.; D’Adda, M.; Salvucci, M.; Stagno, F.; Rege-Cambrin, G.; Tiribelli, M.; et al. Treatment-Free Remission in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients Treated Front-Line with Nilotinib: 10-Year Followup of the GIMEMA CML 0307 Study. Haematologica 2022, 107, 2356–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, F.G.; Sasaki, K.; Issa, G.C.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Ravandi, F.; Kadia, T.; Cortes, J.; Konopleva, M.; Pemmaraju, N.; Alvarado, Y.; et al. Treatment-Free Remission in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Following the Discontinuation of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Am. J. Hematol. 2022, 97, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, H.J.; Kukreja, M.; Goldman, J.M.; Wang, T.; Halter, J.; Arora, M.; Gupta, V.; Rizzieri, D.A.; George, B.; Keating, A.; et al. Prognostic Factors for Outcomes in Allogeneic Transplantation for CML in the Imatinib Era: A CIBMTR Analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012, 47, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Liu, Q.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Q.; Ye, Y.; Huang, H.; Meng, F.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, M. Prior Exposure to Imatinib Does Not Impact Outcome of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Transplantation for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients: A Single-Center Experience in China. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 2495–2505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heim, D.; Baldomero, H.; Medinger, M.; Masouridi-Levrat, S.; Schanz, U.; Nair, G.; Güngör, T.; Halter, J.; Passweg, J.R.; Chalandon, Y.; et al. Allogeneic Haematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia in Switzerland in the Face of Rapid Development of Effective Drugs. Swiss Med. Wkly 2024, 154, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichs, B.; Tichelli, A.; Bacigalupo, A.; Russell, N.H.; Ruutu, T.; Shapira, M.Y.; Beksac, M.; Hasenclever, D.; Socié, G.; Schmitz, N. Long-Term Outcome and Late Effects in Patients Transplanted with Mobilised Blood or Bone Marrow: A Randomised Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaise, D.; Kuentz, M.; Fortanier, C.; Bourhis, J.H.; Milpied, N.; Sutton, L.; Jouet, J.P.; Attal, M.; Bordigoni, P.; Cahn, J.Y.; et al. Randomized Trial of Bone Marrow versus Lenograstim-Primed Blood Cell Allogeneic Transplantation in Patients with Early-Stage Leukemia: A Report from the Société Française de Greffe de Moelle. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigorito, A.C.; Azevedo, W.M.; Marques, J.F.; Azevedo, A.M.; Eid, K.A.; Aranha, F.J.; Lorand-Metze, I.; Oliveira, G.B.; Correa, M.E.; Reis, A.R.; et al. A Randomised, Prospective Comparison of Allogeneic Bone Marrow and Peripheral Blood Progenitor Cell Transplantation in the Treatment of Haematological Malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998, 22, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couriel, D.R.; Saliba, R.M.; Giralt, S.; Khouri, I.; Andersson, B.; de Lima, M.; Hosing, C.; Anderlini, P.; Donato, M.; Cleary, K.; et al. Acute and Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease after Ablative and Nonmyeloablative Conditioning for Allogeneic Hematopoietic Transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004, 10, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Simón, J.A.; Díez-Campelo, M.; Martino, R.; Brunet, S.; Urbano, A.; Caballero, M.D.; de León, A.; Valcárcel, D.; Carreras, E.; del Cañizo, M.C.; et al. Influence of the Intensity of the Conditioning Regimen on the Characteristics of Acute and Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease after Allogeneic Transplantation. Br. J. Haematol. 2005, 130, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielcarek, M.; Martin, P.J.; Leisenring, W.; Flowers, M.E.D.; Maloney, D.G.; Sandmaier, B.M.; Maris, M.B.; Storb, R. Graft-versus-Host Disease after Nonmyeloablative versus Conventional Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Blood 2003, 102, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Sohn, S.K.; Baek, J.H.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, J.W.; Min, W.S.; Kim, D.W.; Choi, S.-J.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, K.-H.; et al. Retrospective Multicenter Study of Allogeneic Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation Followed by Reduced-Intensity Conditioning or Conventional Myeloablative Regimen. Acta Haematol. 2005, 113, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoudjhane, M.; Labopin, M.; Gorin, N.C.; Shimoni, A.; Ruutu, T.; Kolb, H.-J.; Frassoni, F.; Boiron, J.M.; Yin, J.L.; Finke, J.; et al. Comparative Outcome of Reduced Intensity and Myeloablative Conditioning Regimen in HLA Identical Sibling Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Patients Older than 50 Years of Age with Acute Myeloblastic Leukaemia: A Retrospective Survey from the Acute Leukemia Working Party (ALWP) of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Leukemia 2005, 19, 2304–2312. [Google Scholar]

- Afram, G.; Simón, J.A.P.; Remberger, M.; Caballero-Velázquez, T.; Martino, R.; Piñana, J.L.; Ringden, O.; Esquirol, A.; Lopez-Corral, L.; Garcia, I.; et al. Reduced Intensity Conditioning Increases Risk of Severe cGVHD: Identification of Risk Factors for cGVHD in a Multicenter Setting. Med. Oncol. 2018, 35, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linn, S.M.; Novitzky-Basso, I.; Abduljalil, O.; Pasic, I.; Lam, W.; Law, A.; Michelis, F.V.; Gerbitz, A.; Viswabandya, A.; Lipton, J.; et al. A Single-Center, Real-World Experience of Chronic GVHD Treatment Using Ibrutinib, Imatinib, and Ruxolitinib and Its Treatment Outcomes. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Ther. 2023, 17, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeiser, R. Novel Approaches to the Treatment of Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1820–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| p-value | |||||||

| TKI naïve N = 171 |

IMA N = 41 |

2G-TKI N = 28 |

|||||

| Patient sex, n (%) | 0.211 | ||||||

| Male | 100 | 58.8% | 26 | 63.4% | 12 | 42.9% | |

| Female | 71 | 41.2% | 15 | 36.6% | 16 | 57.1% | |

| Patient age (years), Me [Q1; Q3] | 37 [28; 44] | 35 [26; 40] | 48 [33; 57] | < 0.001 | |||

| Donor sex, n (%) | 0.766 | ||||||

| Male | 101 | 58.7% | 26 | 63.4% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Female | 70 | 41.3% | 15 | 36.6% | 28 | 100% | |

| Donor age (years), M ± SD | 37.0 ± 10.4 | 37.6 ± 11.3 | - | 0.769 | |||

| Type of donor, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Sibling | 129 | 75.5% | 14 | 34.1% | 10 | 35.7% | |

| Unrelated | 37 | 21.6% | 27 | 65.9% | 18 | 64.3% | |

| Other | 5 | 2.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Source of stem cells, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| BM | 100 | 58,5% | 19 | 46,3% | 4 | 14,3% | |

| PBSC | 71 | 41,5% | 22 | 53,7% | 24 | 85,7% | |

| Transplant risk category, Me [Q1; Q3] | 2 [1; 3] | 3 [3; 4] | - | 1.000 | |||

| Median CD34+ count ×106/kg, Me [Q1; Q3] | 4.0 [2.7; 5.7] | 5.5 [2.2; 7.1] | 4.0 [3.6; 4.7] | 0.543 | |||

| Donor positive CMV status, n (%) | 99 | 77.3% | 21 | 51.2% | NA | 0.006 | |

| CML phase at day of transplant, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Chronic Phase | 147 | 88.0% | 14 | 37.9% | 20 | 71.4% | |

| Accelerated Phase | 14 | 8.4% | 8 | 21.6% | 4 | 14.3% | |

| Blast Crisis Phase | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 8.1% | 4 | 14.3% | |

| Second/next Chronic Phase | 6 | 3.6% | 12 | 32.4% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| HU 1 year before transplant | 140 | 98.6% | 14 | 66.7% | NA | <0.001 | |

| IFNa (yes), n (%) | 22 | 14.8% | 16 | 47.1% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| RIC (yes), n (%) | 20 | 11.8% | 7 | 17.1% | 13 | 46.4% | <0.001 |

| High dose TBI (yes), n (%) | 6 | 3.5% | 11 | 28.9% | 1 | 3.6% | <0.001 |

| ATG in condtioning regimen | 48 | 28,1% | 27 | 71,1% | NA | <0.001 | |

| p-value | |||||||

| TKI naïve N = 171 |

IMA N = 41 |

2G-TKI N = 28 |

|||||

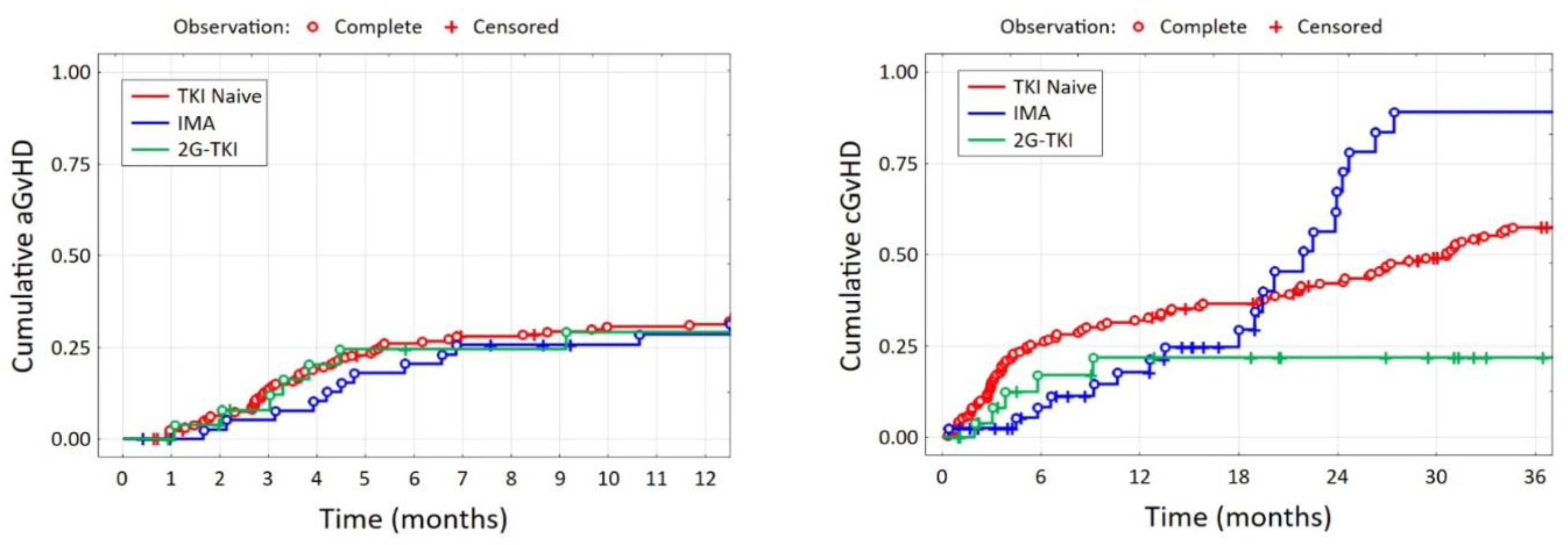

| aGvHD day, Me [Q1; Q3] | 36 [24; 54] | 44 [23; 59] | 32 [24; 49] | 0.894 | |||

| cGvHD day, Me [Q1; Q3] | 139 [103; 250] | 131 [120; 151] | 257 [132; 317] | 0.625 | |||

| aGvHD (yes), n (%) | for 163 pt. | for 27 pt. | 0.044 | ||||

| 100 | 61.4% | 29 | 70.7% | 11 | 40.7% | ||

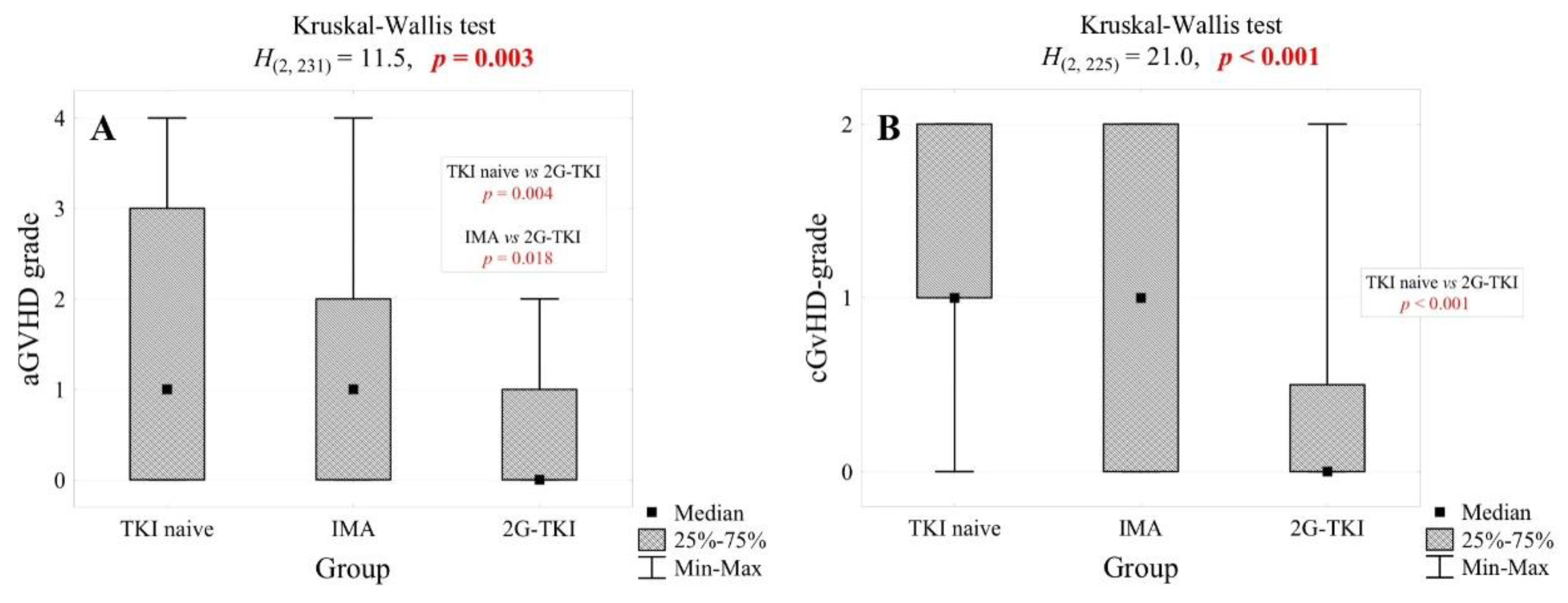

| aGvHD grade, n (%) | for 163 pt. | for 27 pt. | 0.002 | ||||

| 0 | 63 | 38.7% | 12 | 29.3% | 16 | 59.3% | |

| 1 | 25 | 15.3% | 9 | 22.0% | 9 | 33.3% | |

| 2 | 33 | 20.2% | 13 | 31.7% | 2 | 7.4% | |

| 3 | 18 | 11.0% | 6 | 14.6% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 4 | 24 | 14.7% | 1 | 2.4% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| cGvHD (yes), n (%) | for 157 pt. | <0.001 | |||||

| 120 | 76.4% | 21 | 51.2% | 7 | 25.0% | ||

| cGvHD grade, n (%) | for 157 pt. | <0.001 | |||||

| 0 | 37 | 23.6% | 20 | 48.8% | 21 | 75.0% | |

| 1 | 49 | 31.2% | 7 | 17.1% | 2 | 7.1% | |

| 2 | 71 | 45.2% | 14 | 34.1% | 5 | 17.9% | |

| Karnofsky scale at the day of last contact, Me [Q1; Q3] | 85 [0; 100] | 90 [80; 100] | NA | 1.000 | |||

| Patient status at the day of last contact, n (%) | |||||||

| Dead | 76 | 44,4% | 16 | 39,0% | 8 | 29,6% | 0.268 |

| Relapse | 73 | 42,7% | 14 | 35,9% | 3 | 11,1% | 0.007 |

| Variable | Risk Factor for | HR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor sex: female | Acute GvHD | 2.17 | 1.15-4.08 | 0.017 |

| GvHD prophylaxis: ATG | 2.80 | 1.15-6.79 | 0.023 | |

| Donor sex: female | Chronic GvHD | 2.43 | 1.26-4.69 | 0.009 |

| RIC conditioning | 0.24 | 0.11-0.51 | <0.001 | |

| CML accelerated phase | 3.13 | 1.05-9.36 | 0.041 |

| p-value | ||||

| TKI naïve N = 171 |

IMA N = 41 |

2G-TKI N = 28 |

||

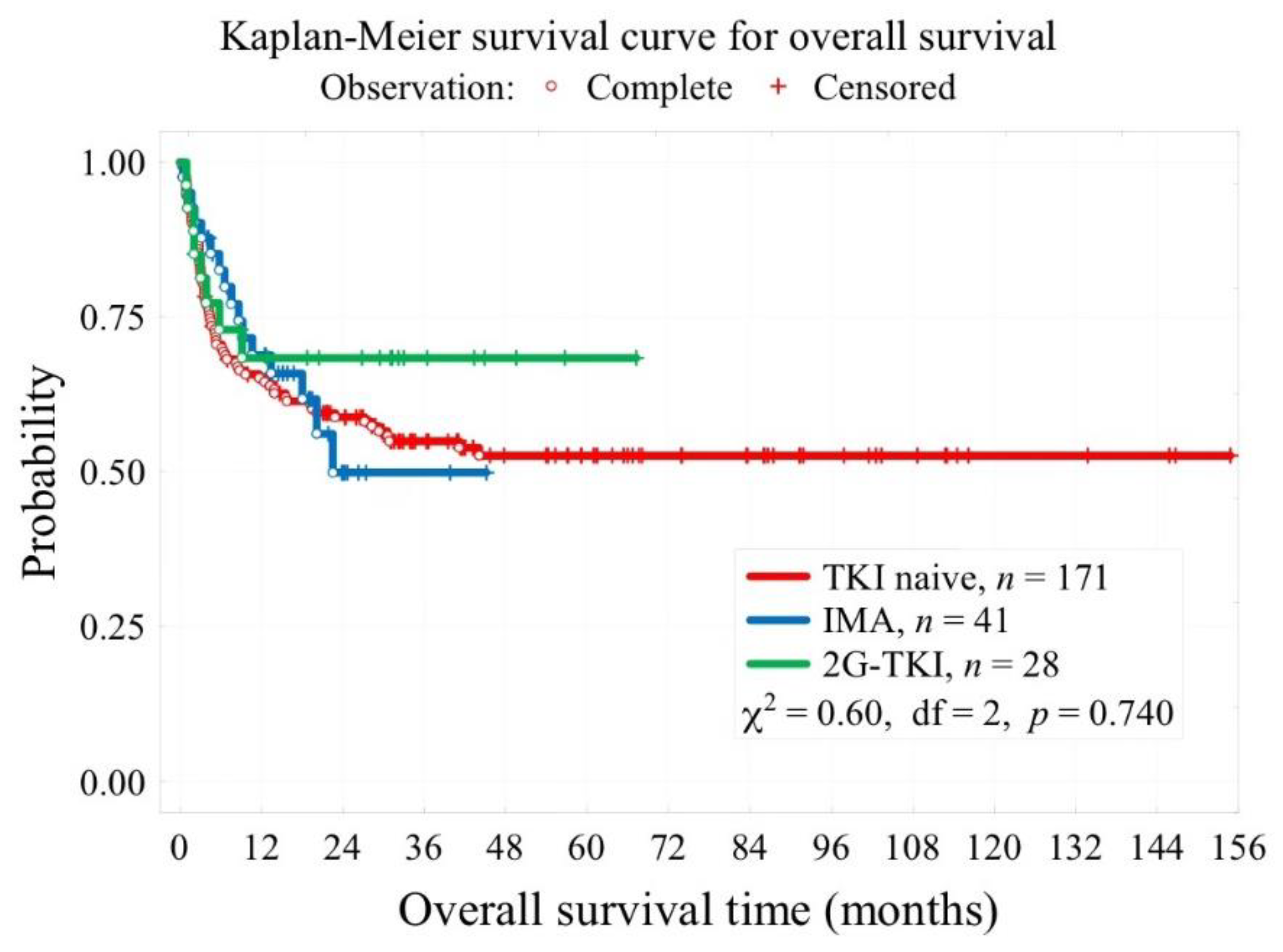

| Median follow-up time, months | 41 [28; 73] for 163 pt. |

19 [14; 24] | 30 [16; 40] | <0.001 |

| 3-year overall survival OS (t=3 years) | 55% | 49.9% | 69.6% | 0.740 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).