Submitted:

07 February 2025

Posted:

08 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

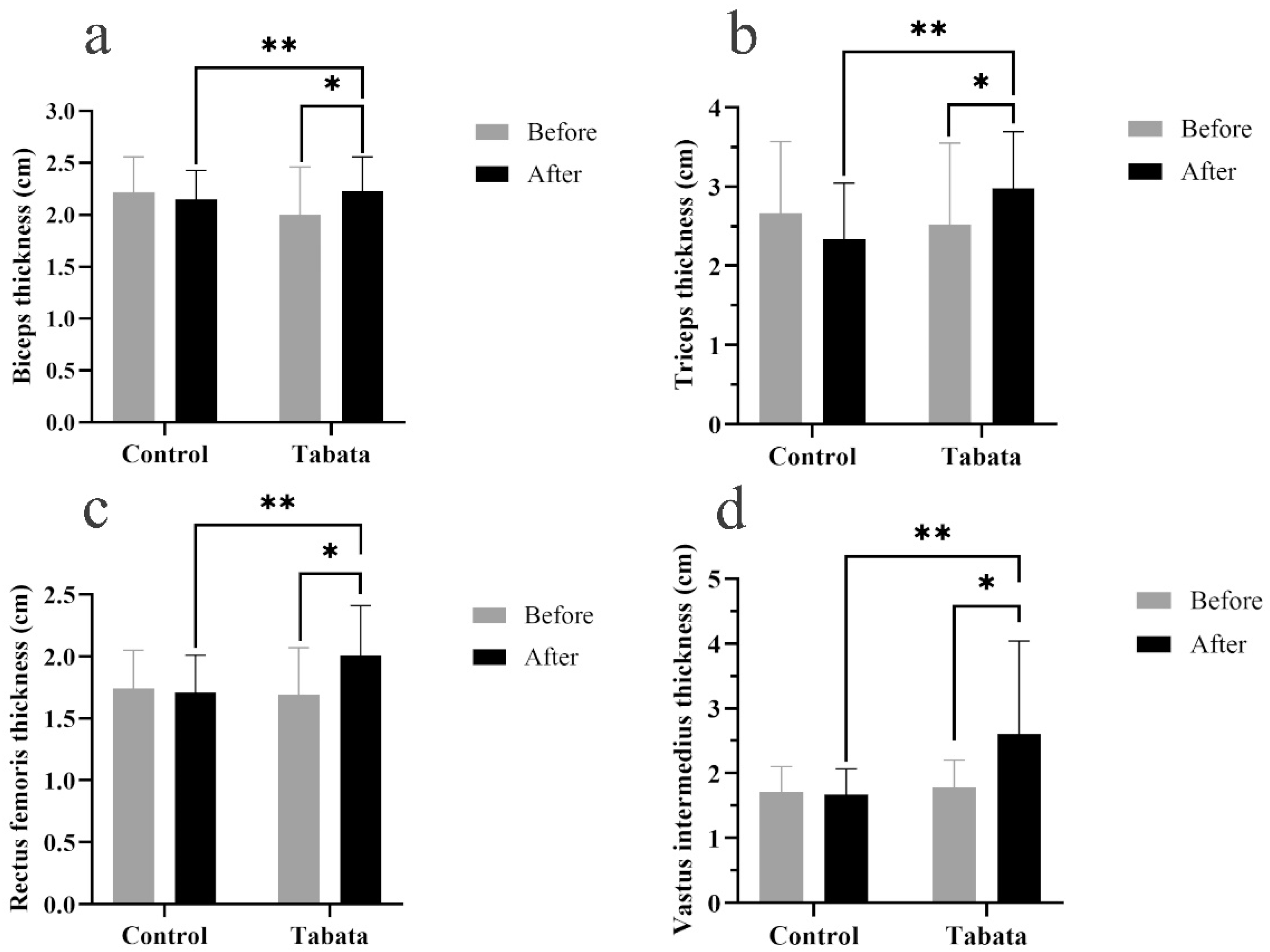

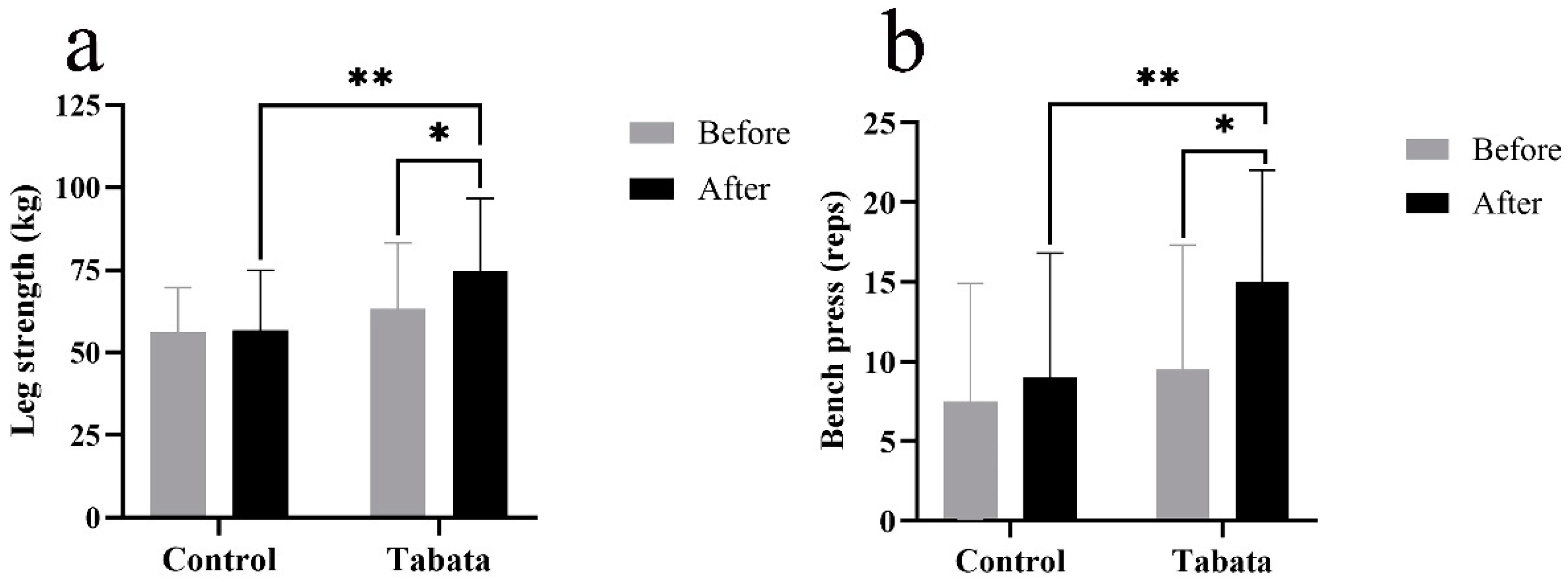

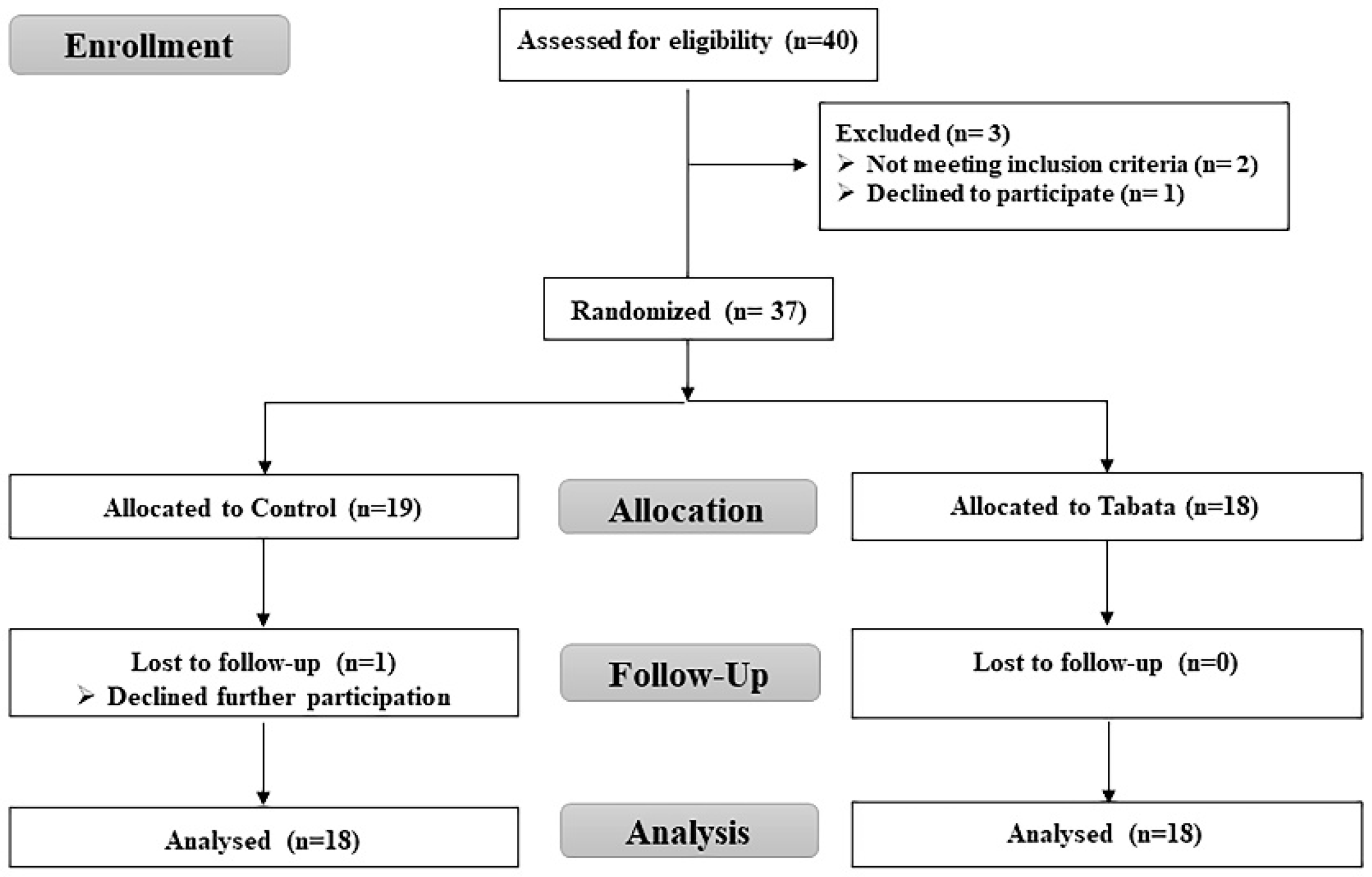

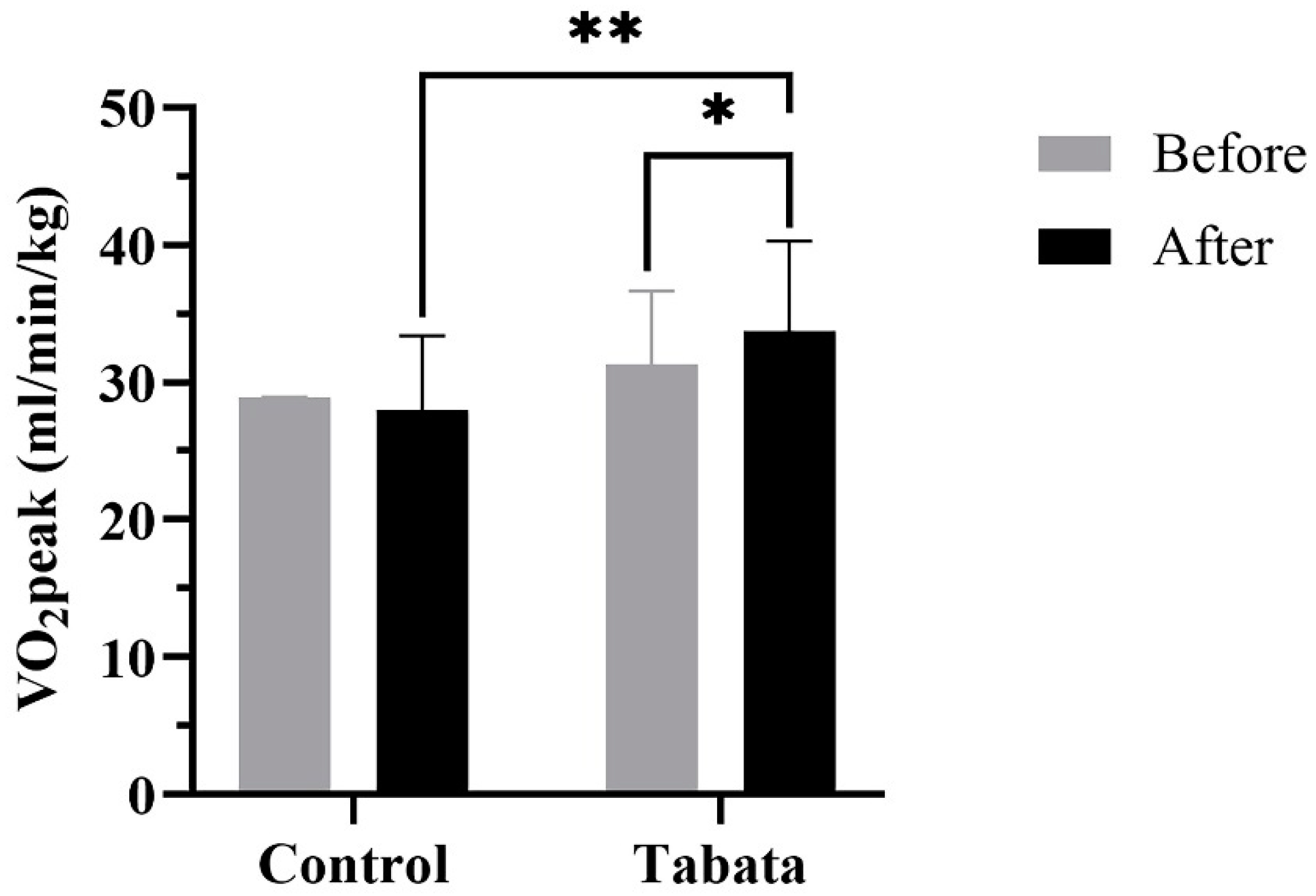

This study was to examine changes in body fat, muscle mass, muscle thickness, and physical and cardiorespiratory fitness in overweight and obese individuals following progressive Tabata training. Thirty-six participants were randomly assigned to either a Tabata group (progressive 4 cycles of body-weight high-intensity intermittent training at 75%-85% of maximum perceived exertion, 3 days/week for 12 weeks) and control group. Body composition, muscle thickness, strength and endurance, and peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) were examined at baseline and after the training and compared between groups. Body fat percentage and fat mass did not change but waist-to-hip ratio was lower in Tabata group (p=0.043). Percentage of muscle mass of right (p=0.026) and left legs (p=0.043) were raised and muscle thickness of biceps, triceps, rectus femoris, and vastus intermedius were increased in Tabata group (all p<0.05) and greater than in control group (p<0.05). Muscle strength and endurance were also increased in Tabata group (p<0.05) as well as VO2peak (p=0.006). Twelve weeks of modified Tabata training effectively increased muscle mass and thickness, and physical and cardiorespiratory fitness, although it did not reduce fat accumulation in overweight and obese. The combination of the training with a dietary intervention may yield more apparent impacts.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design, randomization and non-blinded

2.2. Screening of participants

2.3. Sample size

2.4. Tabata training

2.5. Study end points

2.5.1. Body composition

2.5.2. Muscle thickness

2.5.3. Physical fitness

2.5.4. Cardiorespiratory fitness

2.5.5. Physical activity level

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics and feasibility

3.2. Impact on body composition

3.3. Impact on muscle thickness

3.4. Impact on physical fitness

3.5. Impact on cardiorespiratory fitness

4. Discussion

4.1. Modified Tabata training improves body proportions

4.2. Modified Tabata training improves muscle thickness

4.3. Modified Tabata training improves muscle strength and endurance

4.4. Modified Tabata training improves cardiorespiratory fitness

4.5. Limitations of study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BB | Biceps muscle |

| BF | Body fat |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BMR | Basal metabolic rate |

| BW | Body weight |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| ES | Effect size |

| FFM | Fat-free mass |

| FMs | Fat mass |

| FM | Femur |

| HM | Humerus |

| HIIT | High-intensity intermittent training |

| HR | Heart rate |

| HRmax | Maximal heart rate |

| MAP | Mean arterial pressure |

| MM | Muscle mass |

| RER | Respiratory exchange ratio |

| RF | Rectus femoris muscle |

| RR | Respiratory rate |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| SpO2 | Partial oxygen saturation |

| TC | Triceps muscle |

| VCO2 | Carbon dioxide production |

| VI | Vastus intermedius muscle |

| VO2 | Oxygen uptake |

| VO2max | Maximal oxygen consumption |

| VT | Ventilatory threshold |

| WHO | World health organization |

| WHR | Waist-hip ratio |

References

- Murray, C.J.L.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Zheng, P.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdollahpour, I.; et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunogbe, A.; Nugent, R.; Spencer, G.; Powis, J.; Ralston, J.; Wilding, J. Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: current and future estimates for 161 countries. BMJ Glob Health 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaei, M.; Sundararajan, E.A.; Driss, M.; Boulila, W.; Shapi'i, A. A systematic literature review on obesity: Understanding the causes & consequences of obesity and reviewing various machine learning approaches used to predict obesity. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2021, 136, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.; Irfan, W.; Jameel, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R.K. Obesity and Cancer: A Current Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Outcomes, and Management. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Gerdes, M.W.; Martinez, S.G. Identification of Risk Factors Associated with Obesity and Overweight—A Machine Learning Overview. Sensors 2020, 20, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel Report: Guidelines (2013) for the management of overweight and obesity in adults. Obesity (Silver Spring), 2. [CrossRef]

- ACSM. ACSM information on high-intensity interval training. 2014.

- Tschakert, G.; Hofmann, P. High-Intensity Intermittent Exercise: Methodological and Physiological Aspects. International journal of sports physiology and performance 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutcher, S.H. High-intensity intermittent exercise and fat loss. J Obes 2011, 2011, 868305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.B.; Dring, K.J.; Nevill, M.E. High-Intensity Intermittent Exercise: Effect on Young People's Cardiometabolic Health and Cognition. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016, 15, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, S.; Thoma, C.; Hallsworth, K.; Parikh, J.; Hollingsworth, K.G.; Taylor, R.; Jakovljevic, D.G.; Trenell, M.I. High intensity intermittent exercise improves cardiac structure and function and reduces liver fat in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, I. Tabata training: one of the most energetically effective high-intensity intermittent training methods. J Physiol Sci 2019, 69, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, I.; Nishimura, K.; Kouzaki, M.; Hirai, Y.; Ogita, F.; Miyachi, M.; Yamamoto, K. Effects of moderate-intensity endurance and high-intensity intermittent training on anaerobic capacity and VO2max. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996, 28, 1327–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, I.; Irisawa, K.; Kouzaki, M.; Nishimura, K.; Ogita, F.; Miyachi, M. Metabolic profile of high intensity intermittent exercises. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1997, 29, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, R.B.; de Lira, C.A.B.; Naves, J.P.A.; Coswig, V.S.; Del Vecchio, F.B.; Gentil, P. Tabata protocol: a review of its application, variations and outcomes. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2019, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto-Mikami, E.; Tsuji, K.; Horii, N.; Hasegawa, N.; Fujie, S.; Homma, T.; Uchida, M.; Hamaoka, T.; Kanehisa, H.; Tabata, I.; et al. Gene expression profile of muscle adaptation to high-intensity intermittent exercise training in young men. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 16811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuensiri, N.; Suksom, D.; Tanaka, H. Effects of High-Intensity Intermittent Training on Vascular Function in Obese Preadolescent Boys. Child Obes 2018, 14, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, G.R.; Harris, N.; Duncan, S.; Plank, L.D.; Merien, F.; Schofield, G. Low-Active Male Adolescents: A Dose Response to High-Intensity Interval Training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2016, 48, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Hall, E.E.; Petruzzello, S.J. The relationship between exercise intensity and affective responses demystified: to crack the 40-year-old nut, replace the 40-year-old nutcracker! Ann Behav Med 2008, 35, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western, P. The Asia-Pacific perspective : redefining obesity and its treatment; Sydney : Health Communications Australia: 2000.

- Triyulianti S, P.A. , Utami R. The Effect of High Intensity Interval Training on Maximal Oxygen Uptake (VO2max) in Overweight Adolescents. International Journal of Aging Health and Movement 2023, 5, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentzen, J.; van Wijk, L.; Buis, C.; Viddeleer, A.; Bock, G.; van der Schans, C.; Dam, G.; Kruijff, S.; Klaase, J. Impact and risk factors for clinically relevant surgery-related muscle loss in patients after major abdominal cancer surgery: study protocol for a prospective observational cohort study (MUSCLE POWER). International Journal of Clinical Trials 2019, 6, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spineti, J.; Figueiredo, T.; Miranda, H.; de Salles, B.; Oliveira, L.; Simão, R. The effects of exercise order and periodized resistance training on maximum strength and muscle thickness. International SportMed Journal 2014, 15, 374–390. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Sports, M. ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription; Sixth edition. Philadelphia : Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, [2000] ©2000: 2000.

- Bruce, R.A. Exercise testing of patients with coronary heart disease. Principles and normal standards for evaluation. Ann Clin Res 1971, 3, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jalayondeja, C.; Jalayondeja, W.; Vachalathiti, R.; Bovonsunthonchai, S.; Sakulsriprasert, P.; Kaewkhuntee, W.; Bunprajun, T.; Upiriyasakul, R. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the Compendium of Physical Activity: Thai Translation and Content Validity. J Med Assoc Thai 2015, 98 Suppl 5, S53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Baecke, J.A.; Burema, J.; Frijters, J.E. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr 1982, 36, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanca-Valeriano, S.; Espinola-Sánchez, M.; Caballero-Alvarado, J.; Canelo-Aybar, C. Effect of high-intensity interval training compared to moderate-intensity continuous training on body composition and insulin sensitivity in overweight and obese adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amuri, A.; Sanz, J.M.; Capatti, E.; Di Vece, F.; Vaccari, F.; Lazzer, S.; Zuliani, G.; Dalla Nora, E.; Passaro, A. Effectiveness of high-intensity interval training for weight loss in adults with obesity: a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2021, 7, e001021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airin, S.; Linoby, A.; Mohamad Zaki, M.S.; Baki, H.; Sariman, H.; Esham, B.; Mohd Azam, M.Z.; Mohamed, M.N. The Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training and Continuous Training on Weight Loss and Body Composition in Overweight Females. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Colloquium on Sports Science, Exercise, Engineering and Technology 2014 (ICoSSEET 2014), Singapore, 2014//, 2014.

- Türk, Y.; Theel, W.; Kasteleyn, M.J.; Franssen, F.M.E.; Hiemstra, P.S.; Rudolphus, A.; Taube, C.; Braunstahl, G.J. High intensity training in obesity: a Meta-analysis. Obes Sci Pract 2017, 3, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wewege, M.; van den Berg, R.; Ward, R.E.; Keech, A. The effects of high-intensity interval training vs. moderate-intensity continuous training on body composition in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2017, 18, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardavani, A.; Aziz, H.; Smith, K.; Atherton, P.J.; Phillips, B.E.; Idris, I. The Effects of Very Low Energy Diets and Low Energy Diets with Exercise Training on Skeletal Muscle Mass: A Narrative Review. Adv Ther 2021, 38, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astorino, T.A.; Schubert, M.M.; Palumbo, E.; Stirling, D.; McMillan, D.W. Effect of two doses of interval training on maximal fat oxidation in sedentary women. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2013, 45, 1878–1886. [Google Scholar]

- Tjønna, A.E.; Stølen, T.O.; Bye, A.; Volden, M.; Slørdahl, S.A.; Ødegård, R.; Skogvoll, E.; Wisløff, U. Aerobic interval training reduces cardiovascular risk factors more than a multitreatment approach in overweight adolescents. Clinical science 2009, 116, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N.A.; Caudwell, P.; Hopkins, M.; Byrne, N.M.; Colley, R.; Hills, A.P.; Stubbs, J.R.; Blundell, J.E. Metabolic and behavioral compensatory responses to exercise interventions: barriers to weight loss. Obesity 2007, 15, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melanson, E.L.; Keadle, S.K.; Donnelly, J.E.; Braun, B.; King, N.A. Resistance to exercise-induced weight loss: compensatory behavioral adaptations. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 2013, 45, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue, M.N.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Trexler, E.T.; Hirsch, K.R. The effects of high intensity interval training on muscle size and quality in overweight and obese adults. Journal of science and medicine in sport 2018, 21, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; DeHoyos, D.V.; Pollock, M.L.; Garzarella, L. Time course for strength and muscle thickness changes following upper and lower body resistance training in men and women. Eur J Appl Physiol 2000, 81, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, L.; Weltman, J.; Hartman, M.; Johannes, D.; Weltman, A. Growth Hormone Release During Acute and Chronic Aerobic and Resistance Exercise. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 2002, 32, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francois, M.E.; Little, J.P. Effectiveness and safety of high-intensity interval training in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr 2015, 28, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaroni, R.S.; Brigatto, F.A.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Braz, T.V.; Benvenutti, J.C.; Germano, M.D.; Marchetti, P.H.; Aoki, M.S.; Lopes, C.R. High Resistance-Training Frequency Enhances Muscle Thickness in Resistance-Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res 2019, 33 Suppl 1, S140–s151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, G.; Payne, A.; Zelt, J.G.; Scribbans, T.D.; Jung, M.E.; Little, J.P.; Gurd, B.J. Extremely low volume, whole-body aerobic-resistance training improves aerobic fitness and muscular endurance in females. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2012, 37, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparrós-Manosalva, C.; Garrido-Muñoz, N.; Alvear-Constanzo, B.; Sanzana-Laurié, S.; Artigas-Arias, M.; Alegría-Molina, A.; Vidal-Seguel, N.; Espinoza-Araneda, J.; Huard, N.; Pagnussat, A.S.; et al. Effects of high-intensity interval training on lean mass, strength, and power of the lower limbs in healthy old and young people. Frontiers in Physiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, P.B.; Jenkins, D.G. The scientific basis for high-intensity interval training: optimising training programmes and maximising performance in highly trained endurance athletes. Sports Med 2002, 32, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menz, V.; Marterer, N.; Amin, S.B.; Faulhaber, M.; Hansen, A.B.; Lawley, J.S. Functional vs. Running low-volume high-intensity interval training: Effects on vo2max and muscular endurance. Journal of sports science & medicine 2019, 18, 497. [Google Scholar]

- Gibala, M.J.; McGee, S.L. Metabolic adaptations to short-term high-intensity interval training: a little pain for a lot of gain? Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2008, 36, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohmansyah, N.A.; Ka Praja, R.; Phanpheng, Y.; Hiruntrakul, A. High-Intensity Interval Training Versus Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training for Improving Physical Health in Elderly Women. Inquiry 2023, 60, 469580231172870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjønna, A.E.; Lee, S.J.; Rognmo, Ø.; Stølen, T.O.; Bye, A.; Haram, P.M.; Loennechen, J.P.; Al-Share, Q.Y.; Skogvoll, E.; Slørdahl, S.A.; et al. Aerobic Interval Training Versus Continuous Moderate Exercise as a Treatment for the Metabolic Syndrome. Circulation 2008, 118, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, B.; Guo, A.; Kaila, S.J.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wei, J.; Yao, Y. Elucidating the primary mechanisms of high-intensity interval training for improved cardiac fitness in obesity. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1170324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, R.L.; Costill, D.L.; Fink, W.J.; King, D.S. Effects of eight weeks of bicycle ergometer sprint training on human muscle buffer capacity. Int J Sports Med 1986, 7, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torma, F.; Gombos, Z.; Jokai, M.; Takeda, M.; Mimura, T.; Radak, Z. High intensity interval training and molecular adaptive response of skeletal muscle. Sports Med Health Sci 2019, 1, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control group (n = 18) |

Tabata group (n = 18) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Number | 18 | 18 |

| Sex (n, male:female) | 5:13 | 5:13 |

| Age (years) | 21.61 ± 2.06 | 20.72 ± 1.32 |

| WHO BMI classification (n, overweight:obese) |

2:16 | 5:13 |

| Physical activity score | ||

| - Pretest | 7.01 ± 1.07 | ± 0.99 |

| - Posttest | 6.96 ± 0.79 | 7.31 ± 1.22 |

| Physical activity level | ||

| - Sedentary (n, %) | 3 (17%) | 3 (17%) |

| - Active (n, %) | 11 (61%) | 12 (66%) |

| - Athletic (n, %) | 4 (22%) | 3 (17%) |

| HR (/min) | 77.22 ± 9.35 | 77.00 ± 9.83 |

| RR (/min) | 18.33 ± 3.29 | 16.11 ± 2.03 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 118.65 ± 16.16 | 118.31 ± 11.77 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 74.41 ± 12.54 | 73.94 ± 8.54 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 89.15 ± 13.04 | 88.73 ± 9.00 |

| SpO2 (%) | 97.78 ± 1.21 | 97.50 ± 1.29 |

| Control group (n = 18) | Tabata group (n = 18) | p-value of change between groups | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | Posttest | Mean change |

Pretest | Posttest | Mean change |

|||||

| BW (kg) | 74.25 ± 19.70 | 73.85 ± 17.80 | -0.20 ± 4.77 | 73.85 ± 28.05 | 74.70 ± 25.80 | 1.45 ± 2.78 | 0.281 | |||

| Height (cm) | 163.00 ± 9.06 | 163.11 ± 8.86 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 163.00 ± 9.06 | 163.16 ± 8.77 | -0.05 ± 0.23 | 0.956 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.10 ± 5.15 | 28.00 ± 4.72 | -0.05 ± 1.73 | 27.00 ± 7.47 | 27.75 ± 7.98 | 0.40 ± 1.13 | 0.269 | |||

| MM (kg) | 23.35 ± 7.80 | 23.55 ± 7.78 | -0.30 ± 1.15 | 23.30 ± 9.85 | 23.60 ± 10.55 | 0.20 ± 1.38 | 0.290 | |||

| FMs (kg) | 31.00 ± 11.13 | 30.00 ± 9.52 | 0.25 ± 2.68 | 29.20 ± 15.20 | 30.85 ± 14.48 | 0.75 ± 3.97 | 0.529 | |||

| BF (%) | 40.20 ± 10.25 | 39.60 ± 10.73 | 0.80 ± 2.22 | 41.10 ± 11.90 | 39.90 ± 15.02 | -0.15 ± 3.90 | 0.927 | |||

| FFM (kg) | 42.65 ± 13.02 | 42.80 ± 12.93 | -0.70 ± 1.88 | 42.75 ± 16.63 | 43.15 ± 17.00 | 0.45 ± 2.48 | 0.361 | |||

| BMR (kcal) | 1,291.50 ± 281.25 |

1,295.00 ± 280.25 |

-16.00 ± 41.25 |

1,293.50 ± 359.75 |

1,302.00 ± 368.00 |

9.5 ± 53.75 | 0.361 | |||

| Water (L) | 31.20 ± 9.55 | 31.30 ± 9.67 | -0.45 ± 1.33 | 31.30 ± 12.08 | 31.60 ± 12.50 | 0.25 ± 1.83 | 0.384 | |||

| Protein (kg) | 8.45 ± 2.68 | 8.50 ± 2.55 | -0.10 ± 0.35 | 8.40 ± 3.20 | 8.50 ± 3.60 | 0.10 ± 0.33 | 0.300 | |||

| Mineral (kg) | 3.11 ± 0.87 | 3.01 ± 0.80 | -0.05 ± 0.14 | 2.98 ± 1.11 | 3.00 ± 1.10 | 0.10 ± 0.23 | 0.293 | |||

| WHR | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 0.94 ± 0.06* | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 0.89 ± 0.06** | -0.01 ± 0.03 | 0.043 | |||

| Control group (n = 18) | Tabata group (n = 18) |

p-value of change between groups |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | Posttest | Mean change | Pretest | Posttest | Mean change | ||||

| Right arm (kg) | 2.38 ± 0.66 | 2.40 ± 0.65 | 0.01 ± 0.10 | 2.44 ± 0.70 | 2.45 ± 0.71 | 0.01 ± 0.10 | 0.937 | ||

| Right arm (%) | 93.38 ± 9.00 | 94.08 ± 8.17 | 0.70 ± 4.36 | 96.60 ± 12.35 | 96.80 ± 13.30 | 0.20 ± 3.51 | 0.707 | ||

| Left arm (kg) | 2.35 ± 0.64 | 2.35 ± 0.63 | -0.00 ± 0.11 | 2.38 ± 0.66 | 2.43 ± 0.69 | 0.04 ± 0.10 | 0.198 | ||

| Left arm (%) | 92.20 ± 8.17 | 92.11 ± 7.05 | -0.09 ± 4.76 | 94.78 ± 12.71 | 95.98 ± 13.50 | 1.19 ± 3.51 | 0.363 | ||

| Right leg (kg) | 7.20 ± 1.50 | 7.04 ± 1.49* | -0.16 ± 0.24 | 7.41 ± 1.88 | 7.43 ± 1.88** | 0.02 ± 0.24 | 0.031 | ||

| Right leg (%) | 93.71 ± 6.55 | 91.56 ± 6.11* | -1.72 ± 2.58 | 96.18 ± 8.03 | 96.22 ± 8.44** | 0.06 ± 2.45 | 0.026 | ||

| Left leg (kg) | 7.13 ± 1.48 | 6.84 ± 1.78 | -0.29 ± 0.84 | 7.38 ± 1.83 | 7.42 ± 1.84 | 0.04 ± 0.25 | 0.117 | ||

| Left leg (%) | 92.78 ± 6.02 | 91.06 ± 6.26* | -1.72 ± 2.58 | 95.87 ± 7.59 | 95.97 ± 8.23** | 0.10 ± 2.60 | 0.043 | ||

| Abdomen (kg) | 20.75 ± 4.10 | 20.79 ± 4.06 | 0.04 ± 0.61 | 20.95 ± 4.30 | 21.17 ± 4.37 | 0.22 ± 0.52 | 0.358 | ||

| Abdomen (%) | 94.56 ± 5.16 | 94.80 ± 4.49 | 0.23 ± 2.80 | 95.99 ± 7.25 | 96.50 ± 7.84 | 0.50 ± 2.11 | 0.750 | ||

| Control group (n = 18) | Tabata group (n = 18) | p-value of changebetween groups | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | Posttest | Mean change |

Pretest | Posttest | Mean change |

||||

| Right arm (kg) | 2.69 ± 1.38 | 2.63 ± 1.32 | 0.33 ± 0.21 | 2.58 ± 1.50 | 2.71 ± 1.56 | 0.09 ± 0.25 | 0.445 | ||

| Right arm (%) | 321.72 ± 161.12 |

324.39 ± 153.33 |

2.67 ± 25.11 | 308.11 ± 170.64 |

322.76 ± 43.70 | 11.03 ± 31.57 |

0.385 | ||

| Left arm (kg) | 2.62 ± 1.37 | 2.66 ± 1.32 | 0.04 ± 0.22 | 2.63 ± 1.50 | 2.67 ± 1.54 | 0.07 ± 0.25 | 0.675 | ||

| Left arm (%) | 324.87 ± 161.29 |

329.37 ± 154.56 |

4.50 ± 25.21 | 313.80 ± 173.20 |

319.14 ± 183.72 |

8.95 ± 31.53 | 0.643 | ||

| Right leg (kg) | 4.85 ± 1.93 | 4.72 ± 1.59 | -0.12 ± 0.56 | 4.75 ± 1.74 | 4.87 ± 1.94 | 0.12 ± 0.41 | 0.138 | ||

| Right leg (%) | 226.24 ± 82.10 |

220.52 ± 69.46 |

-5.71 ± 23.97 |

217.58 ± 80.25 |

222.93 ± 89.87 | 5.29 ± 18.89 | 0.134 | ||

| Left leg (kg) | 4.82 ± 1.89 | 4.68 ± 1.58 | -0.13 ± 0.52 | 4.72 ± 1.71 | 4.85 ± 1.90 | 0.12 ± 0.39 | 0.100 | ||

| Left leg (%) | 225.03 ± 80.70 |

219.66 ± 68.57 |

-5.36 ± 23.46 |

216.13 ± 78.25 |

221.43 ± 88.22 | 5.35 ± 18.93 | 0.142 | ||

| Abdomen (kg) | 15.20 ± 3.84 | 15.58 ± 3.88* | 0.37 ± 0.82 | 15.05 ± 4.83 | 15.26 ± 1.18 | 0.21 ± 1.11 | 0.625 | ||

| Abdomen (%) | 316.30 ± 88.06 |

324.00 ± 87.19* |

7.70 ± 16.94 | 305.77 ± 102.02 |

309.73 ± 108.02 |

3.96 ± 23.14 | 0.583 | ||

| Control group (n = 18) | Tabata group (n = 18) |

p-value of change between groups |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | Posttest | Mean change | Pretest | Posttest | Mean change |

|||||

| Rest | ||||||||||

| HR (beats/min) | 94.44 ± 10.31 | 92.00 ± 11.90 | -2.44 ± 7.51 | 91.72 ± 10.39 | 90.16 ± 10.40 | -1.55 ± 8.84 | 0.747 | |||

| BF (breaths/min) | 20.16 ± 3.85 | 19.50 ± 3.83 | -0.66 ± 2.97 | 21.05 ± 4.24 | 21.66 ± 5.20 | 0.61 ± 2.70 | 0.186 | |||

| RER | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 0.84 ± 0.03* | 0.04 ± 0.06 | 0.81 ± 0.04 | 0.86 ± 0.04* | 0.04 ± 0.06 | 0.740 | |||

| VO2 (L/min) | 0.33 ± 0.07 | 0.29 ± 0.07* | -0.04 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.07 | 0.34 ± 0.08** | -0.02 ± 0.06 | 0.265 | |||

| VO2 (ml/min/kg) | 4.44 ± 0.92 | 3.94 ± 0.80* | -0.50 ± 0.71 | 4.66 ± 0.77 | 4.44 ± 0.86 | -0.22 ± 1.00 | 0.344 | |||

| Exercise | ||||||||||

| HR (/min) | 177.22 ± 14.28 |

181.44 ± 7.90 |

4.22 ± 9.72 |

186.00 ± 8.40 |

191.00 ± 9.57 |

5.00 ± 8.68 |

0.802 | |||

| HR (% age-predicted maximum HR) | 89.33 ± 7.15 | 91.46 ± 4.03 | 2.13 ± 4.89 | 93.34 ± 4.45 | 95.86 ± 5.14 | 2.51 ± 4.34 | 0.806 | |||

| VT1 (ml/min/kg) | 17.22 ± 4.60 | 16.06 ± 3.19 | -1.17 ± 3.29 | 19.89 ± 3.20 | 18.06 ± 3.62 | -1.83 ± 3.91 | 0.584 | |||

| VT2 (ml/min/kg) | 25.56 ± 6.54 | 22.17 ± 4.72* | -3.39 ± 4.79 | 27.78 ± 4.62 | 26.72 ± 5.69** | -1.06 ± 4.39 | 0.137 | |||

| VO2peak (L/min) | 2.18 ± 0.48 | 2.14 ± 0.49 | -0.04 ± 0.24 | 2.42 ± 0.62 | 2.43 ± 0.63** | 0.01 ± 0.28 | 0.323 | |||

| BF (/min) | 45.94 ± 9.25 | 54.44 ± 10.19* | 8.50 ± 9.30 | 48.11 ± 8.87 | 62.22 ± 12.75* | 14.11 ± 12.96 | 0.145 | |||

| RER | 1.06 ± 0.06 | 1.29 ± 0.05* | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 1.07 ± 0.05 | 1.29 ± 1.28* | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 0.625 | |||

| SV (ml) | 76.38 ± 17.04 | 74.20 ± 15.99 | -2.17 ± 9.41 | 79.86 ± 18.31 | 78.62 ± 18.99 | -1.24 ± 15.98 | 0.767 | |||

| CO (L/min) | 13.47 ± 2.98 | 13.19 ± 3.02 | -0.28 ± 1.52 | 14.92 ± 3.85 | 14.50 ± 3.49 | -0.42 ± 2.83 | 0.481 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).