Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

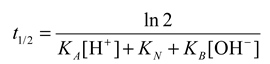

The oil and gas industry has emerged as one of the largest consumers of polymer composites, with dissolvable polymers and composites representing one of the most significant technological advancements in this sector. These materials are essential for the manufacturing of high-performance tools such as hydraulic fracturing plugs, which must withstand extreme downhole conditions—temperatures up to 250°C, pressure differential up to 150 MPa—before dissolving rapidly in wellbore fluids to facilitate continuous production. Unlike traditional dissolvable polymers from the medical or consumer industries, which lack the required thermal stability, mechanical strength, and cost-effectiveness, these advanced materials must be formulated from readily available raw materials and manufactured on an industrial scale. Over the past two decades, significant progress has been made in the design and application of polymers like poly(glycolic acid), polyurethane, polyamide, epoxy, and isocyanate ester, developed through collaborative efforts between academia and industry. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the evolution of dissolvable polymer composites, covering material design, degradation mechanisms, manufacturing processes, and field applications. It concludes with insights into future development opportunities in the field.

Keywords:

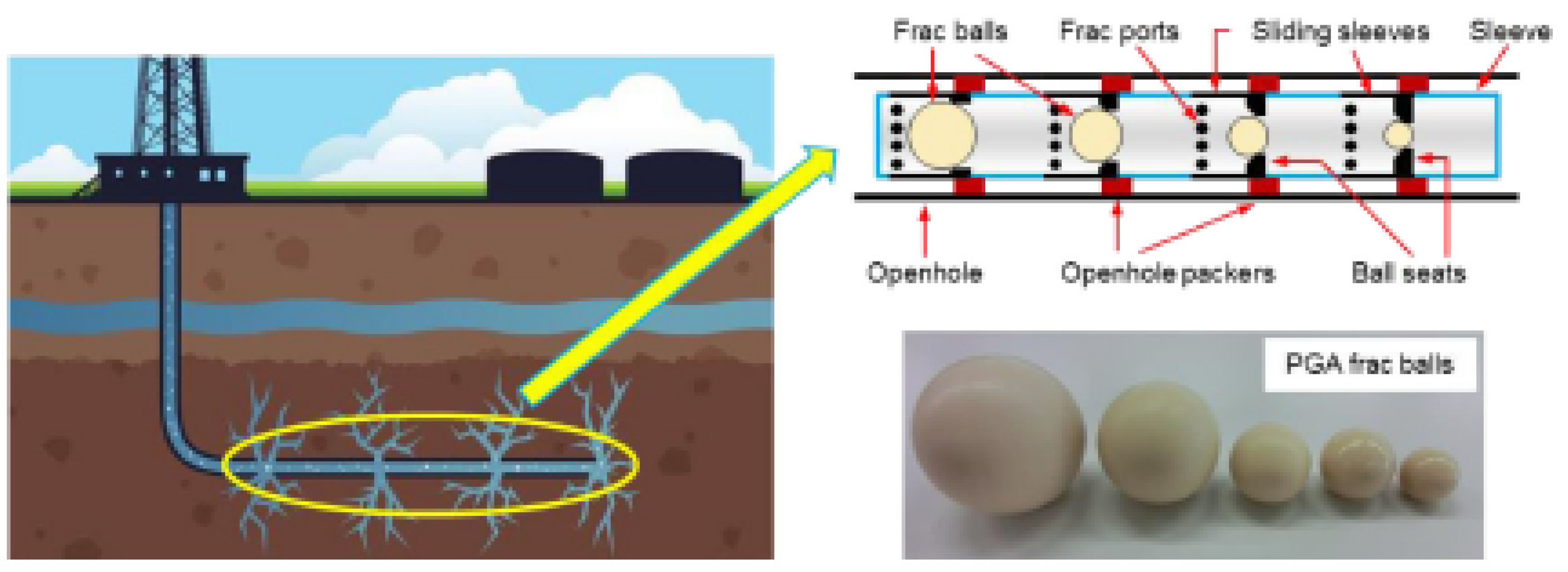

1. Introduction

2. Dissolvable/Degradable Materials Fundamentals

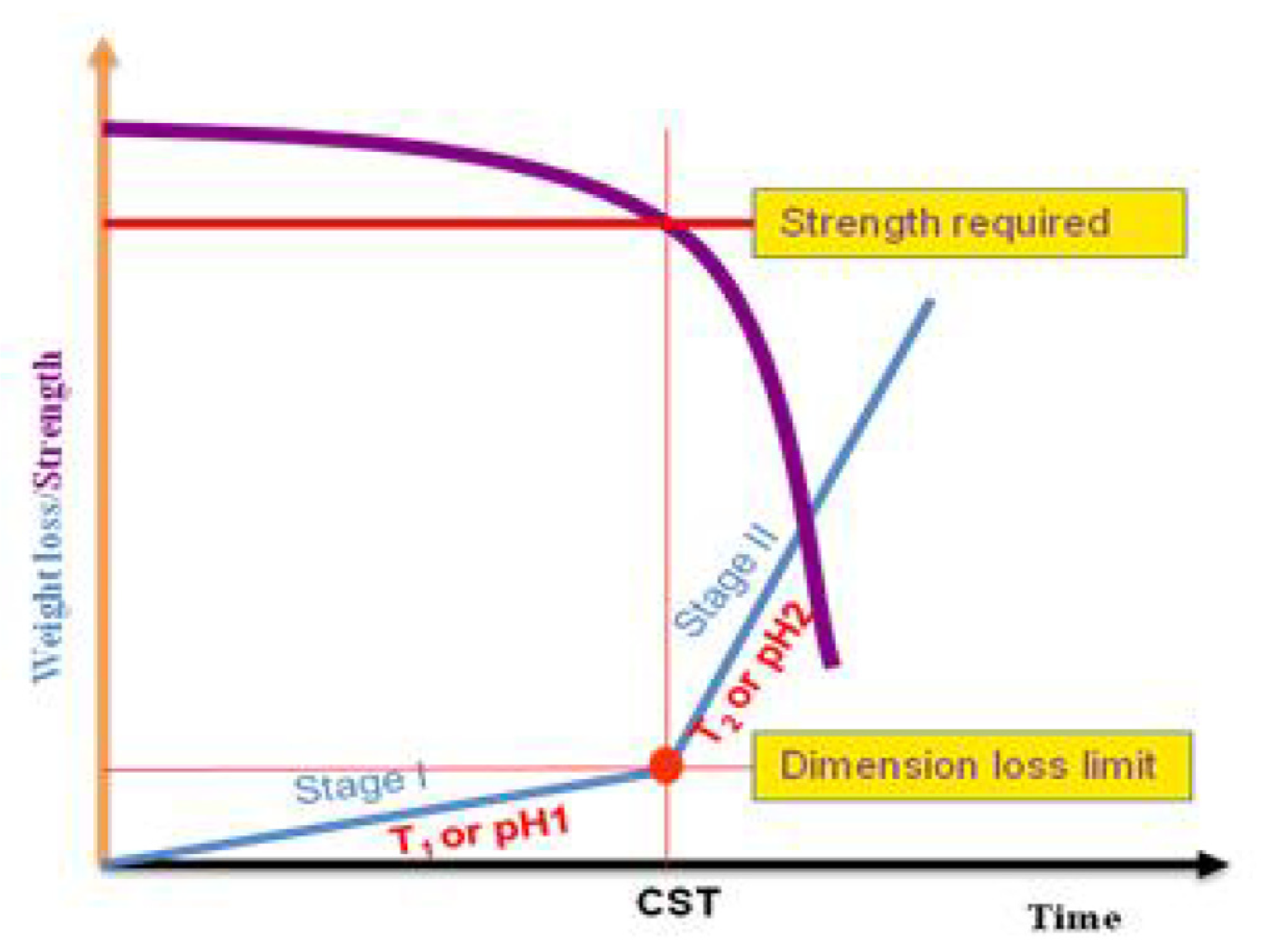

2.1. Polymer Degradation Process

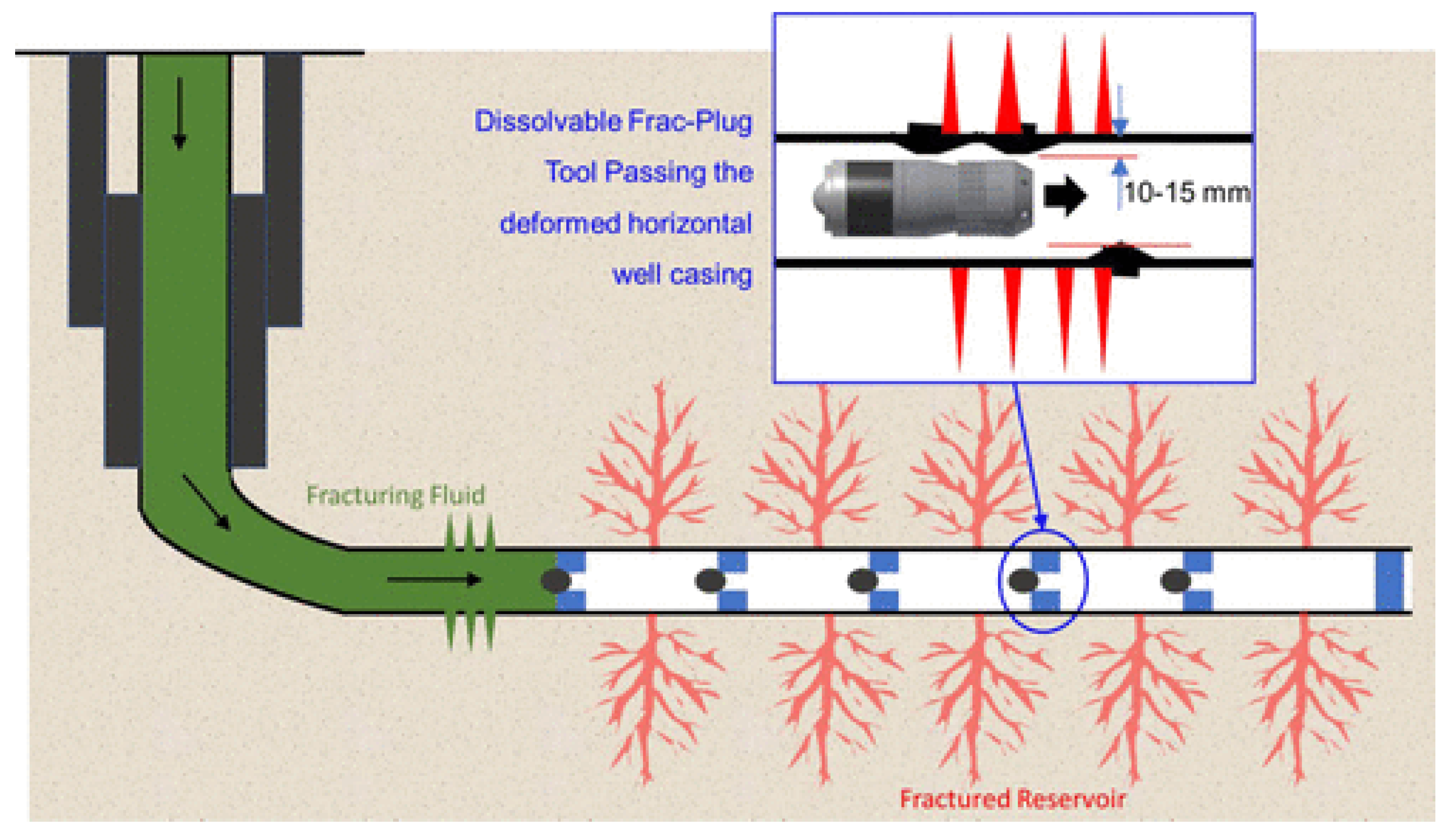

- Type 1: Surface Reaction Type

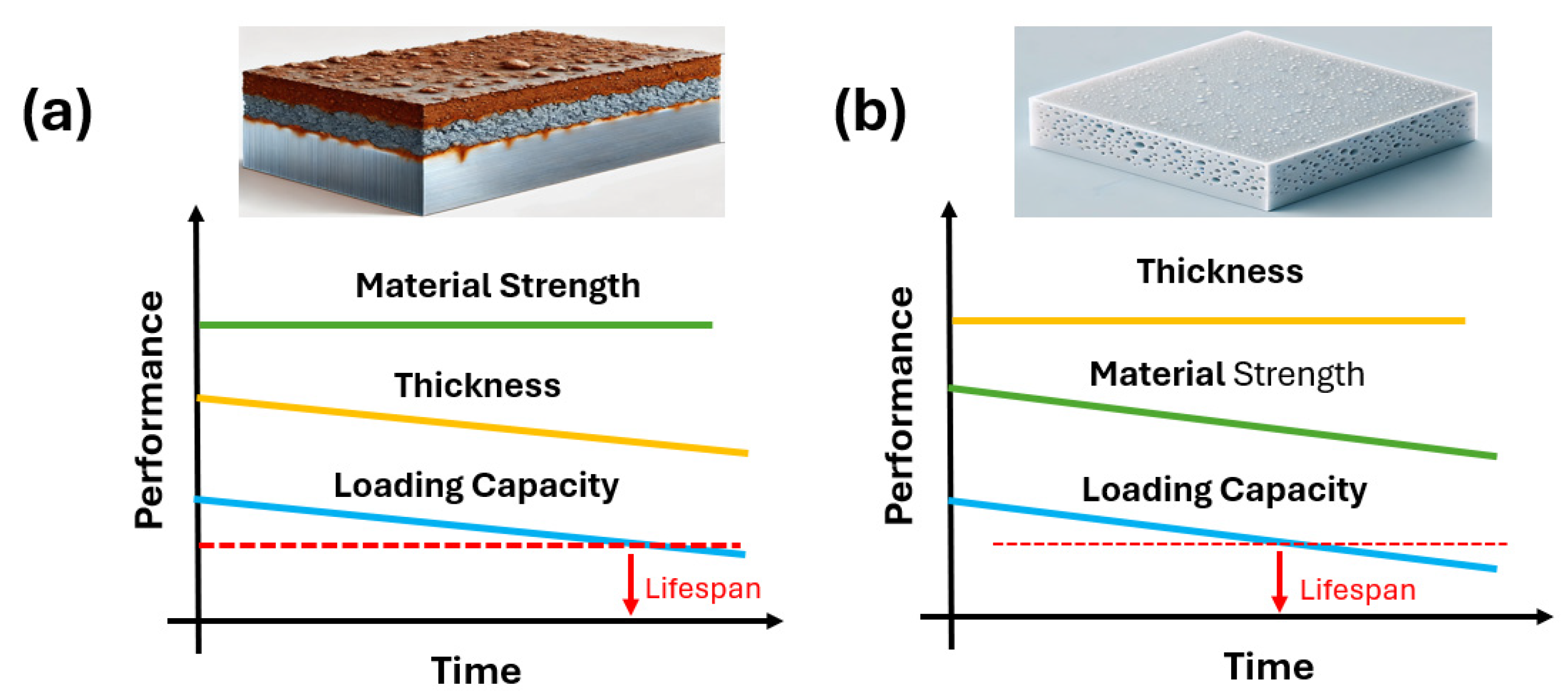

- Type 2: Corrosion Layer Forming Type

- Type 3: Penetration Type

2.2. Unique Requirements from Oil and Gas Industry

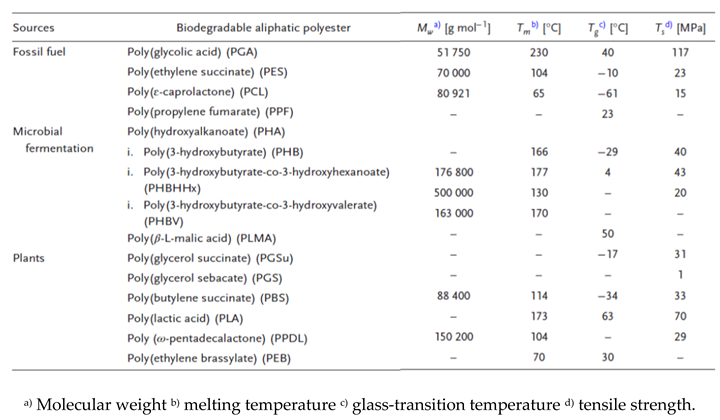

- Biodegradable Materials: These materials are designed to operate at low temperatures, typically below 60°C, to align with human body compatibility or natural environmental conditions [15]. Additionally, their mechanical strength is relatively low. Common examples include thermoplastic materials such as PGA and certain thermoset materials with glass transition temperatures below 60°C, which limits the materials application for high temperature wells.

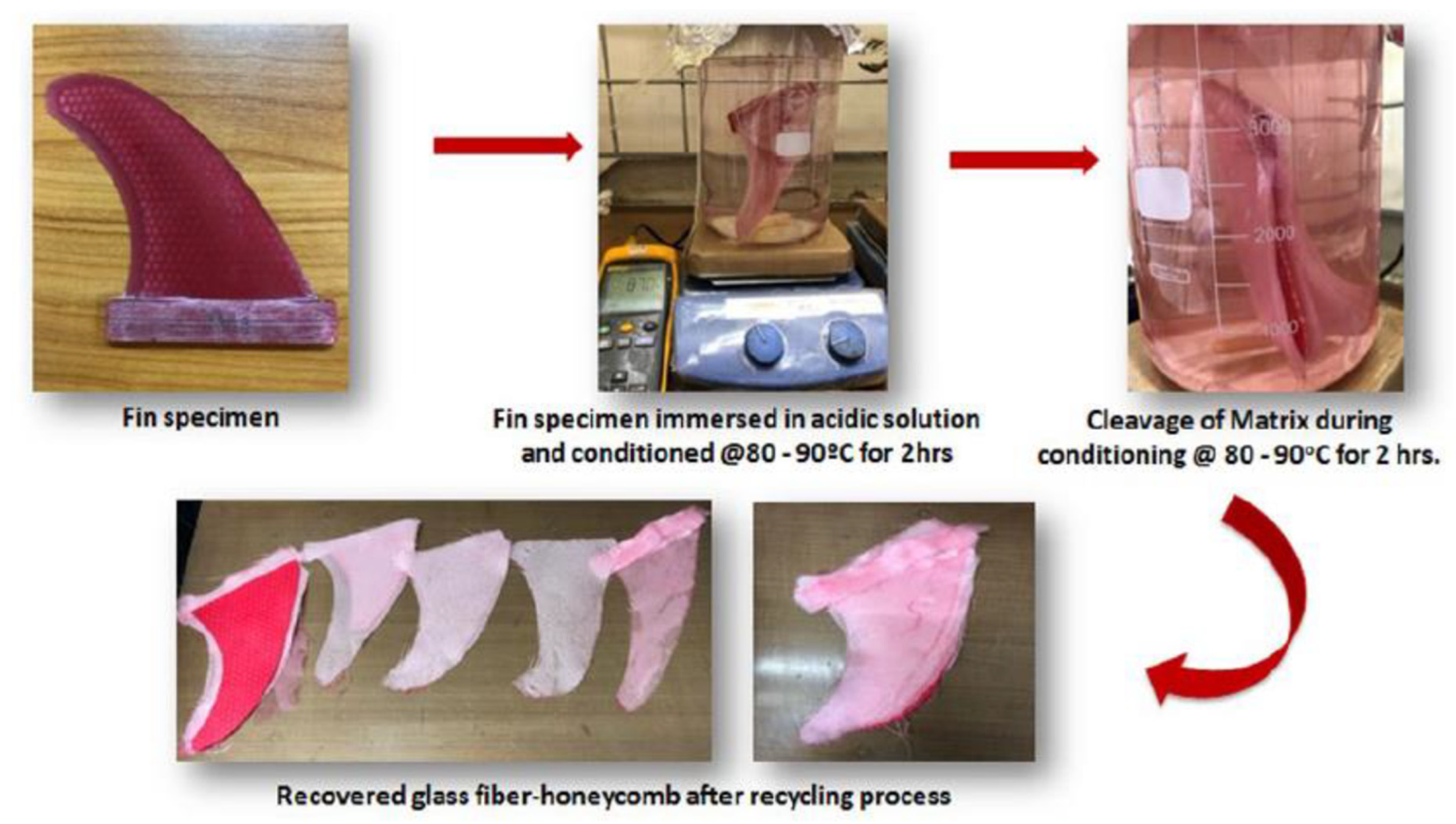

- Sustainable Materials: High-Tg thermoset materials (typically >100°C) are widely used in civil applications such as wind turbines, pipes, and storage tanks, often in fiber-reinforced composite forms. These materials are designed to degrade for recycling purposes, such as recovering expensive fiber reinforcements or reducing waste disposal issues. While their mechanical strength and temperature performance can meet oil and gas requirements, their degradation typically requires highly aggressive environments—such as high temperature and pressure, strong acids/bases, toxic solvents, or supercritical fluids [13,16]. These conditions are not typically present in downhole environments.

2.3. Degradable Polymer Matrix

2.3.1. Dissolvable Polymers

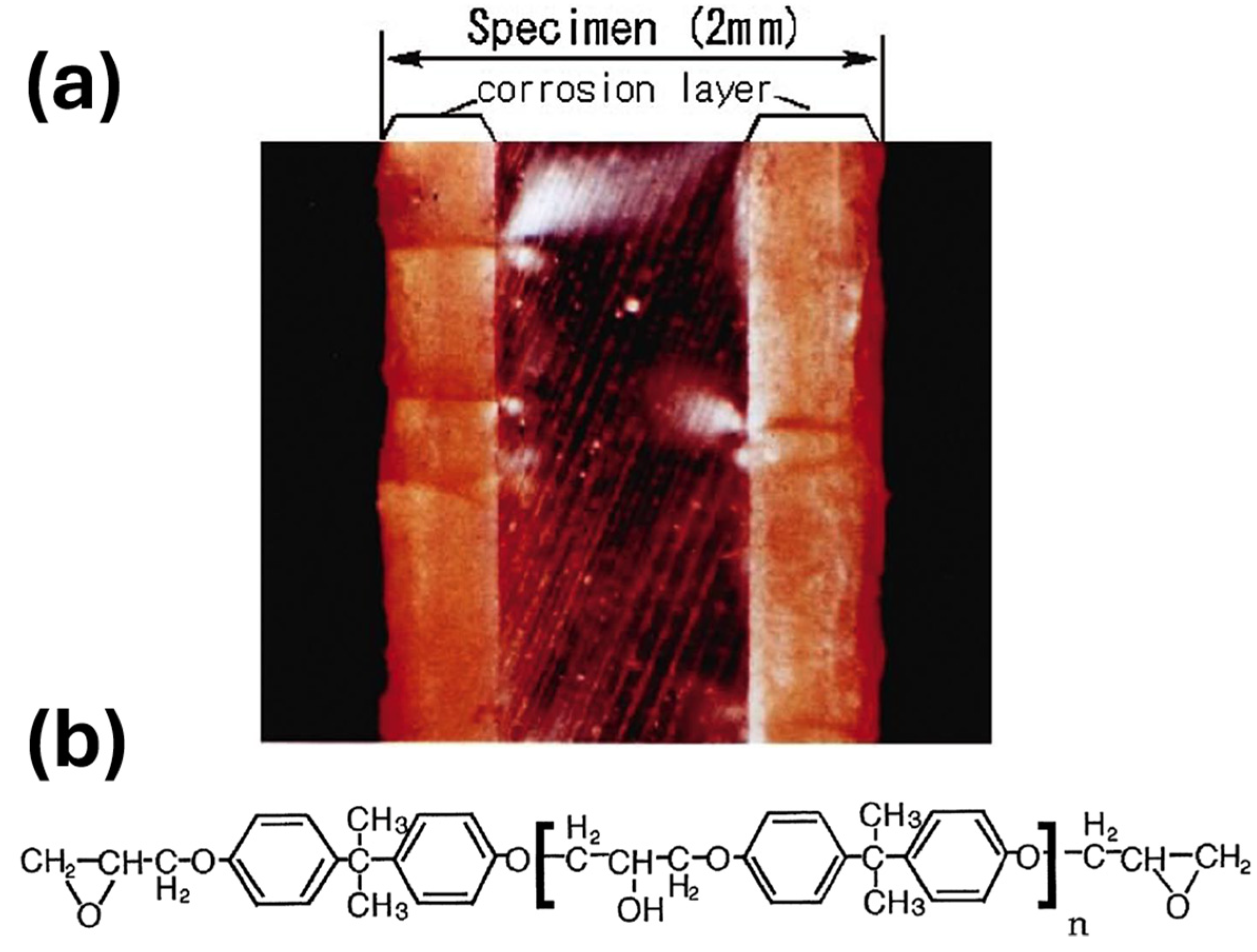

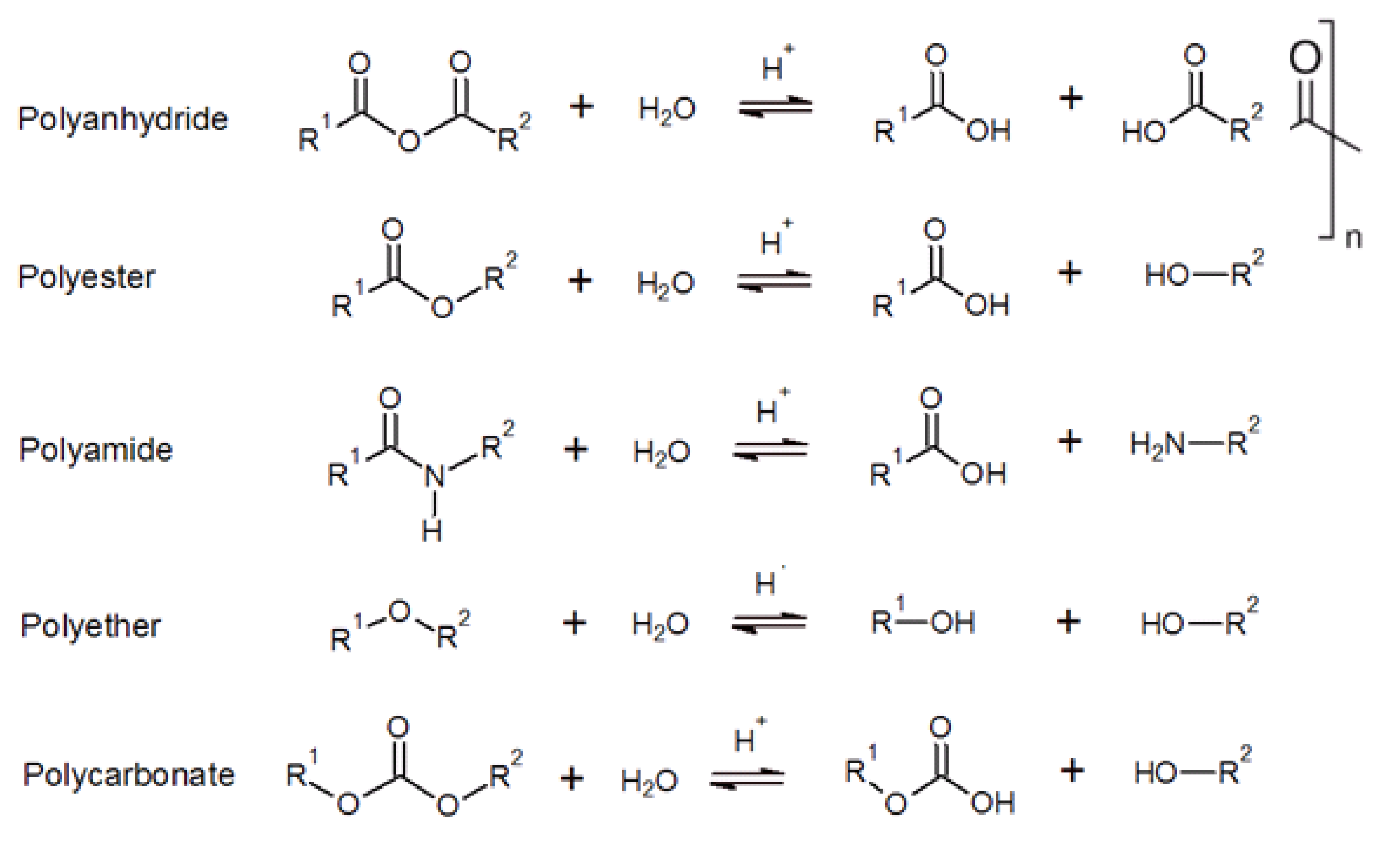

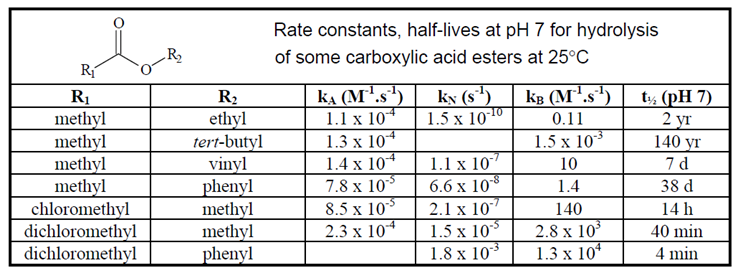

2.3.2. Fundamental of Hydrolysis

2.4. Dissolvable/Degradable Fibers for Reinforcement

2.5. Catalyst for Hydrolysis Process

- The catalyst must not react with the polymer or prepolymer during mixing and processing.

- It must not catalyze hydrolysis during the mixing or processing stages.

- The catalyst must withstand processing conditions, including high temperatures, without degradation, vaporization, or loss of effectiveness.

- The catalyst should be water-free to avoid premature activation.

3. Degradable Thermoplastic Polymers

4. Degradable Thermosetting Polymers

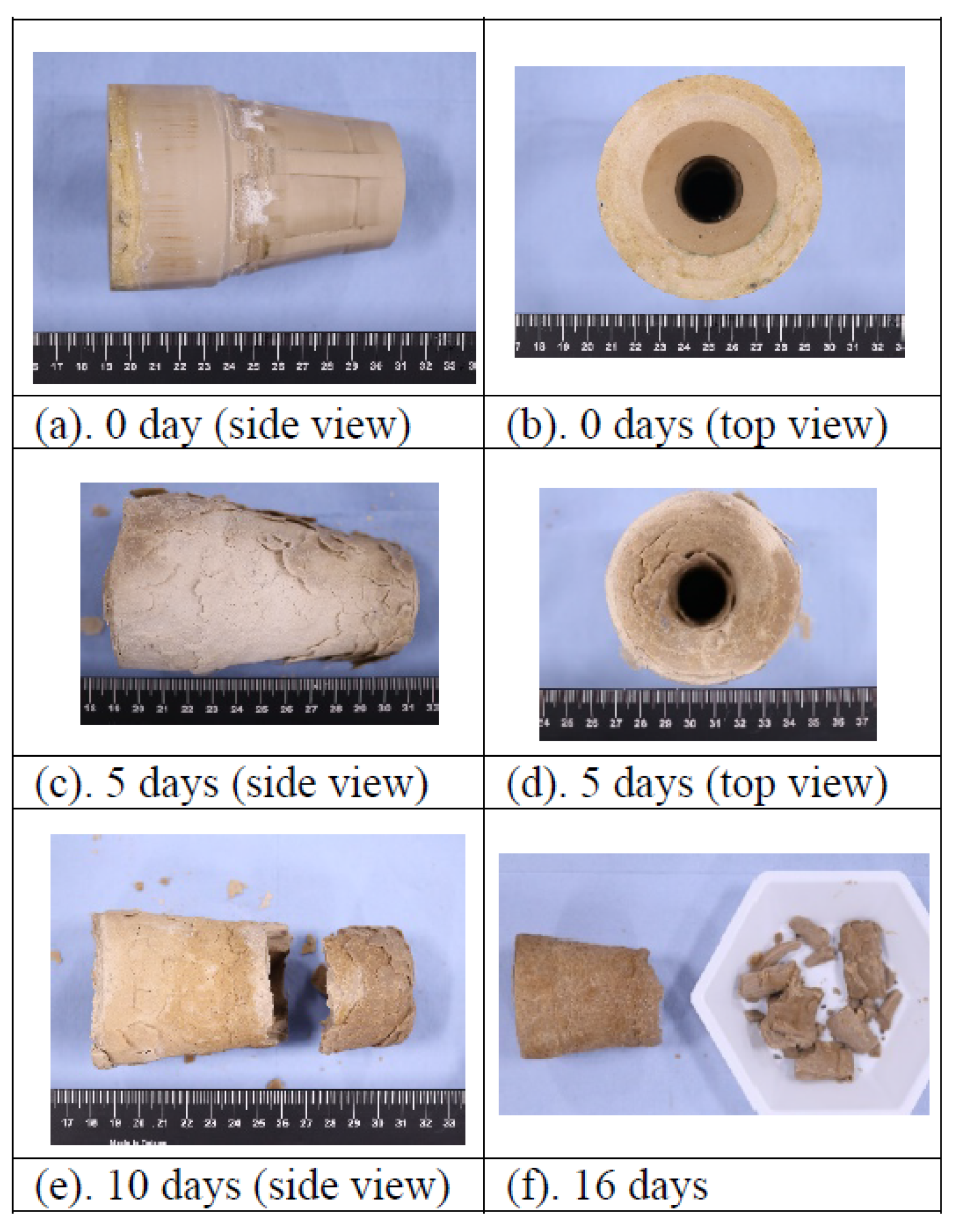

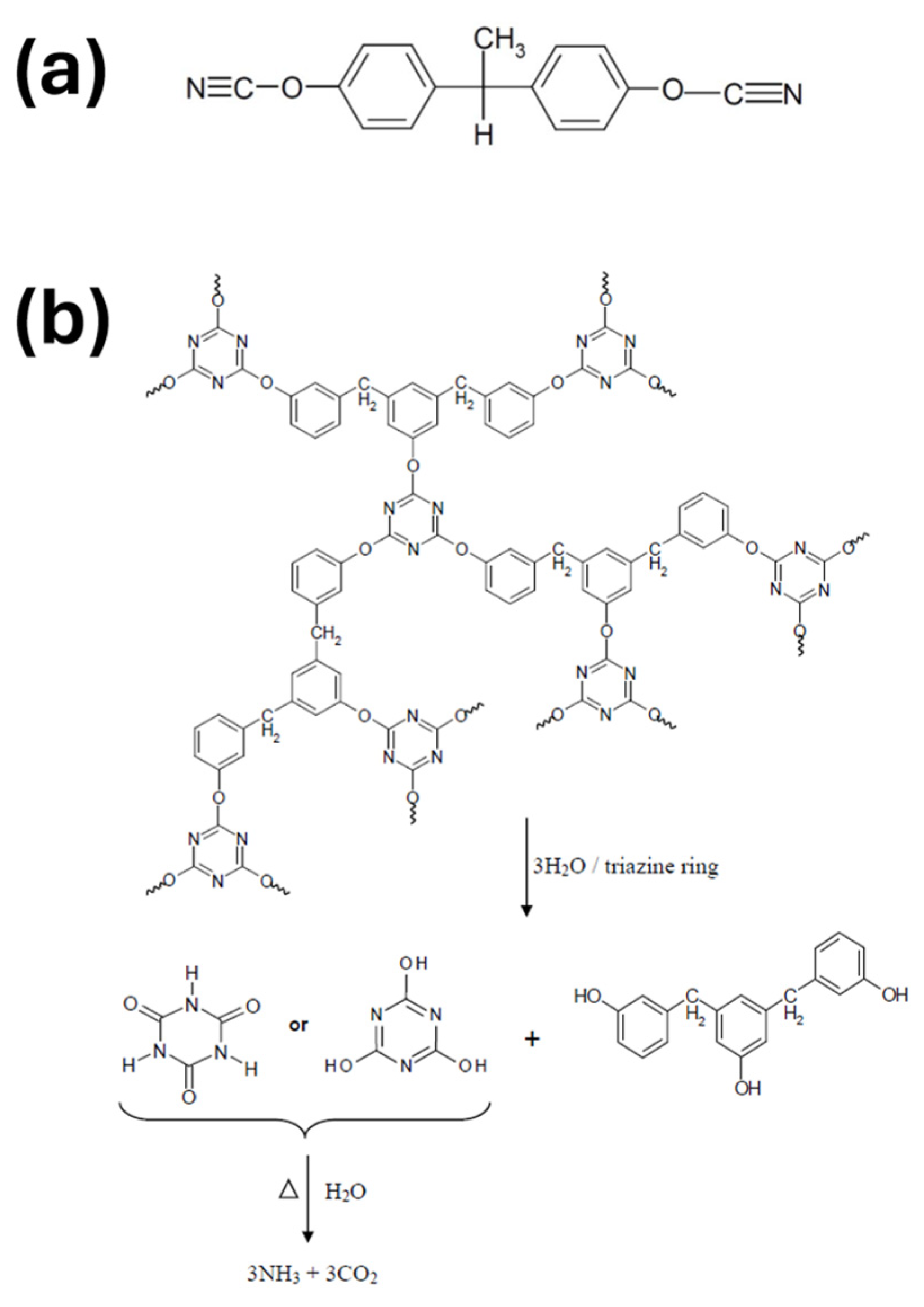

4.1. Cyanate Ester

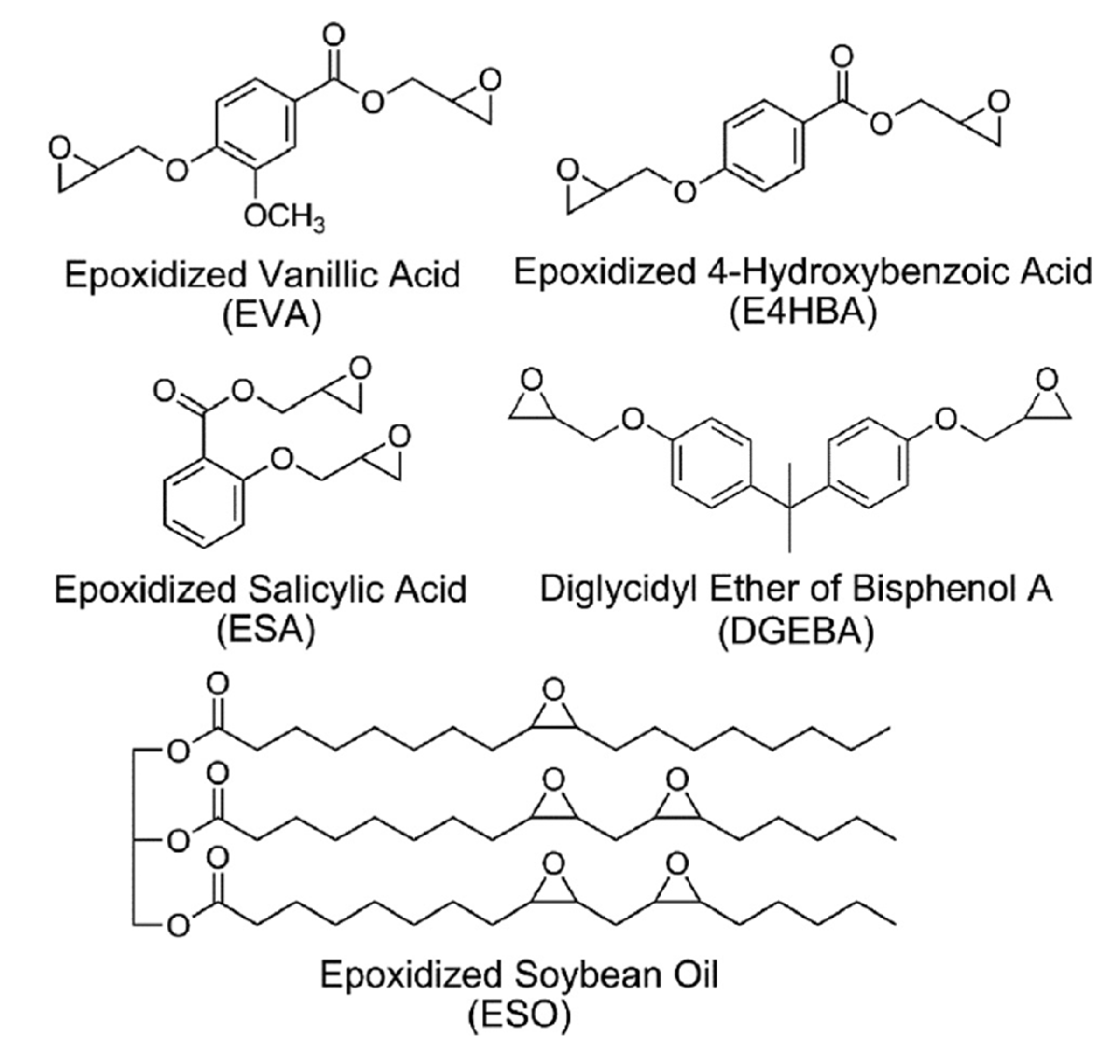

4.2. Epoxy

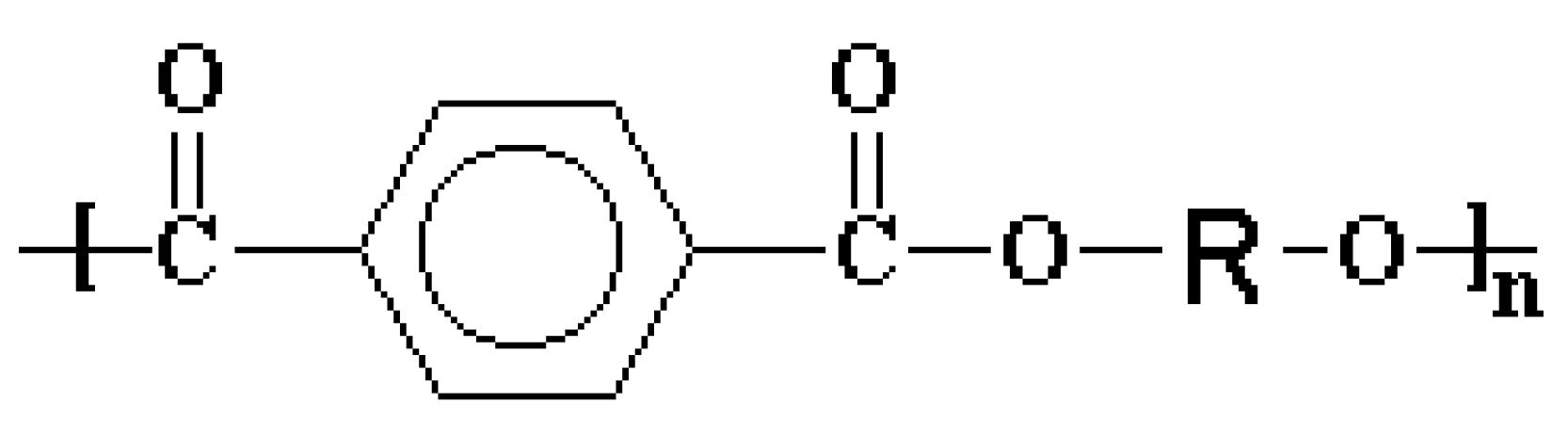

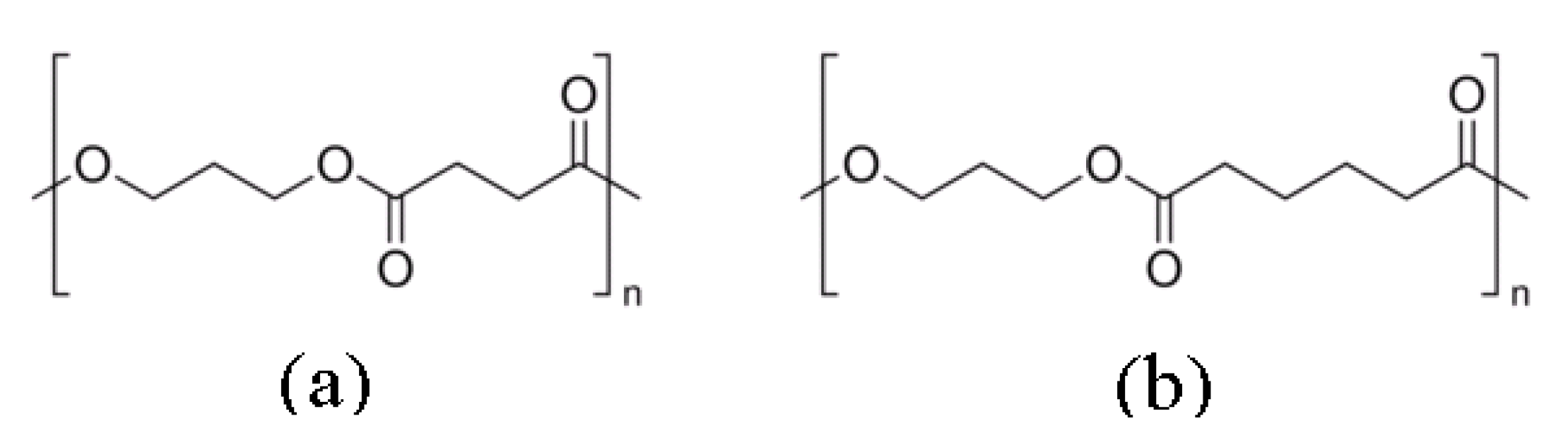

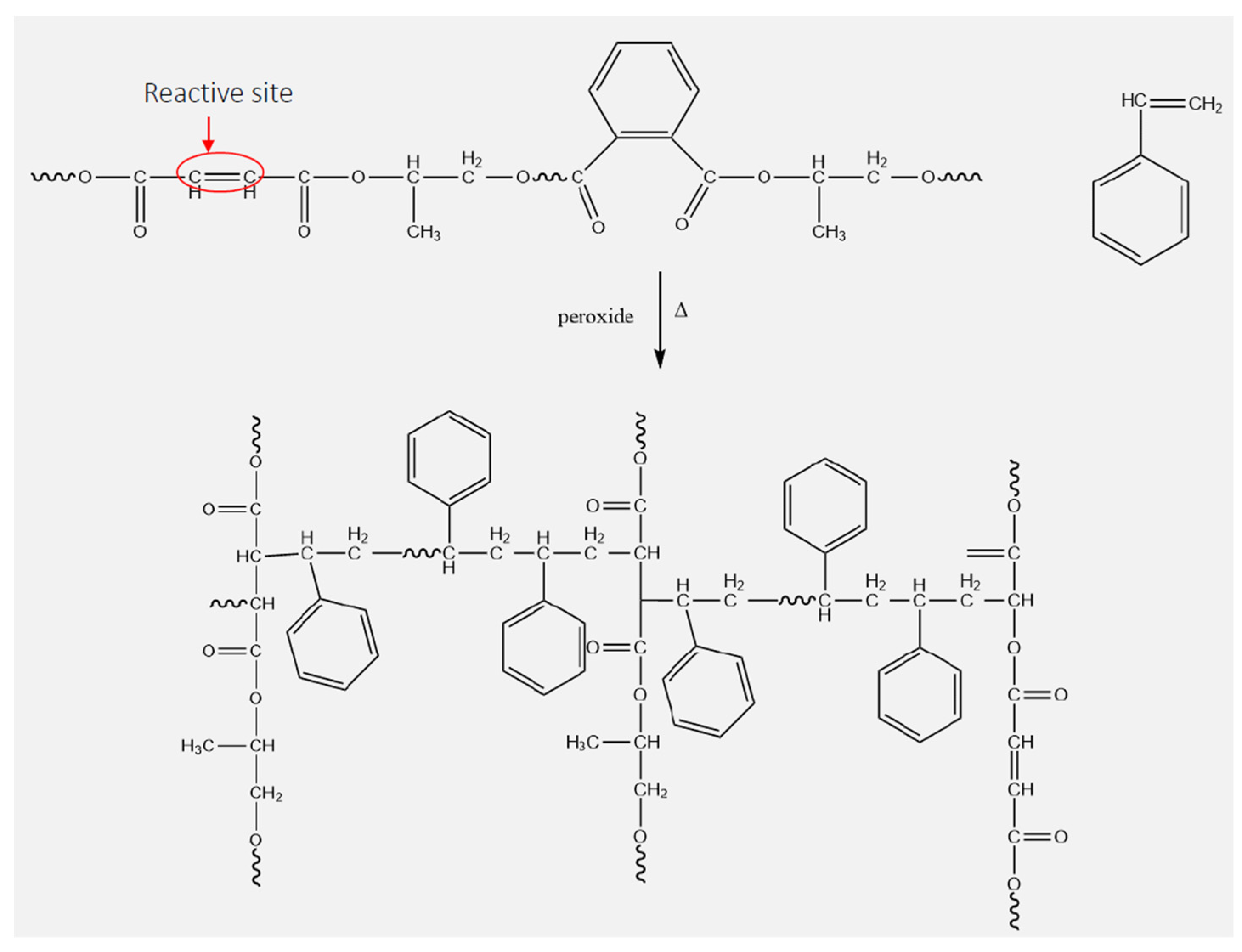

4.3. Polyester

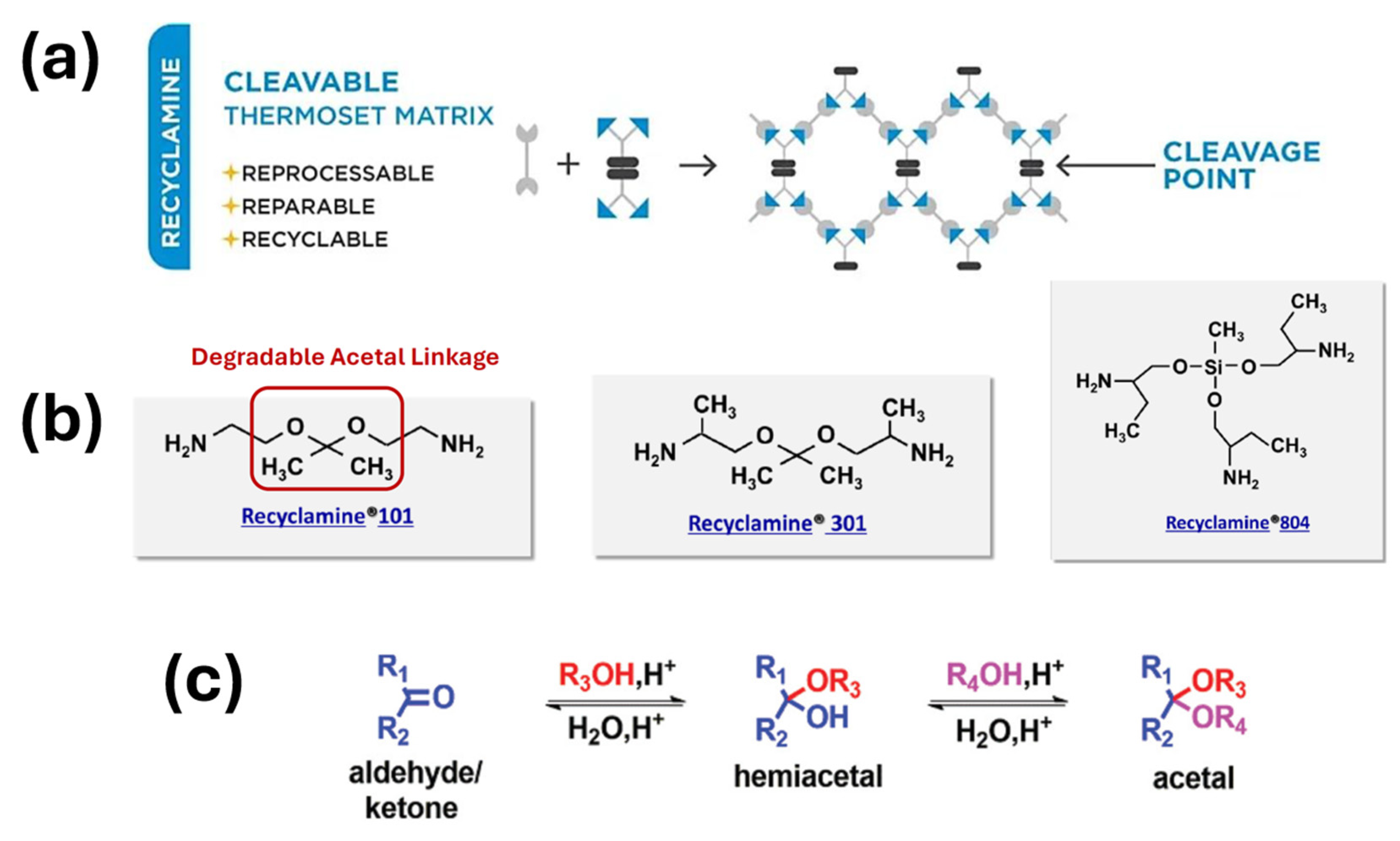

4.4. Acetal Linkages

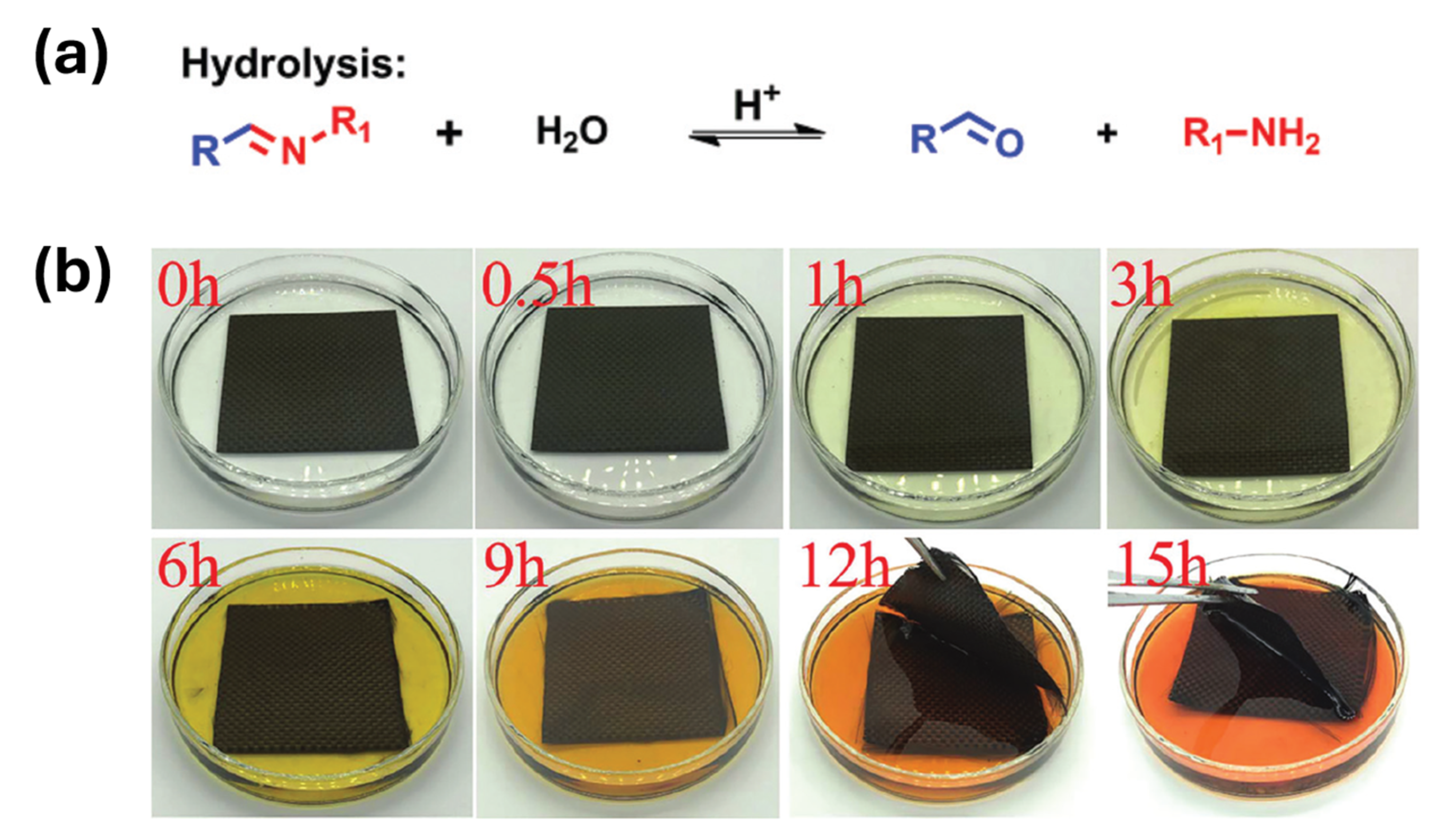

4.5. Other Potential Chemistry

4.5.1. Urea-formaldehyde Resins

4.5.2. Schiff Base Bonds

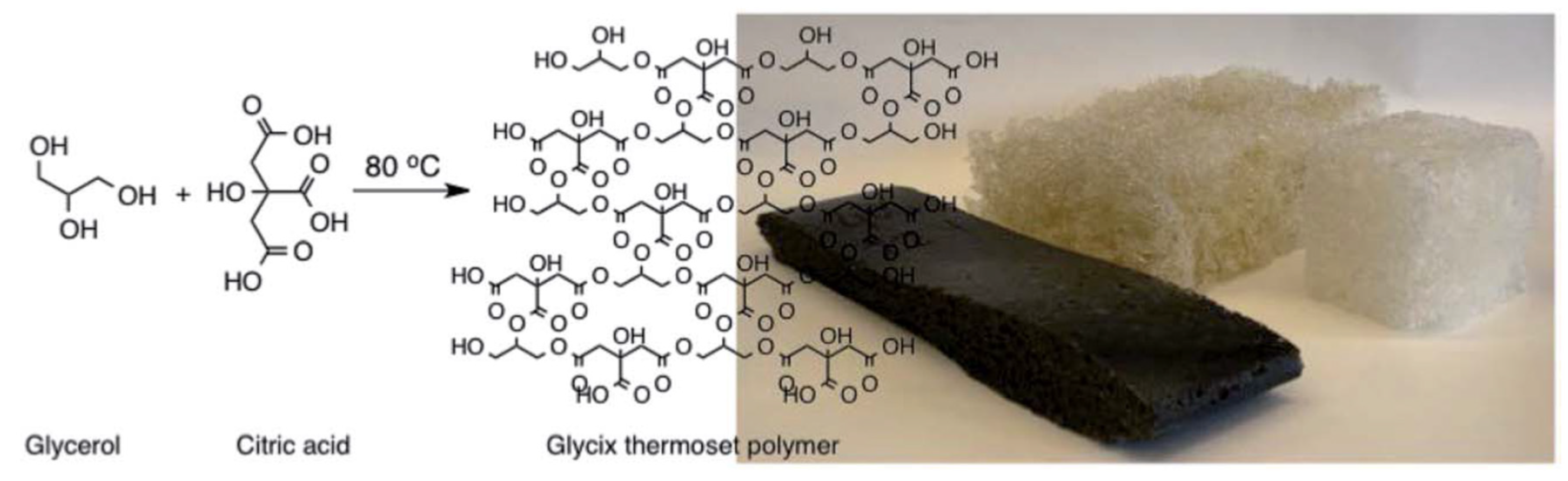

4.5.3. Glycerol-Based Thermosetting Polymers

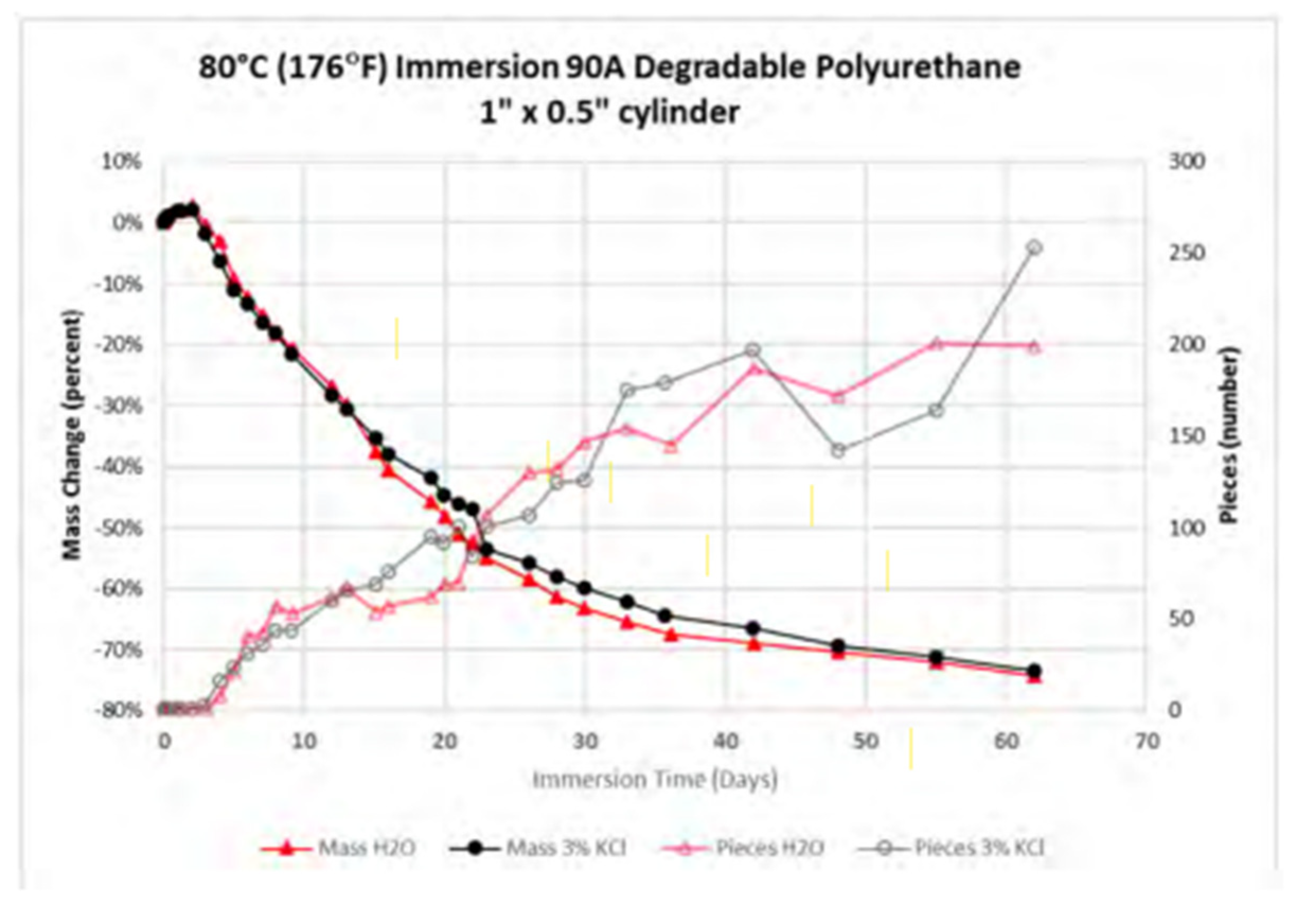

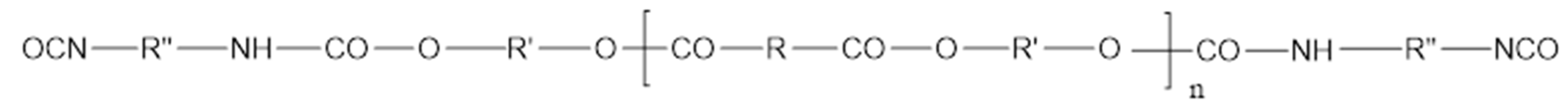

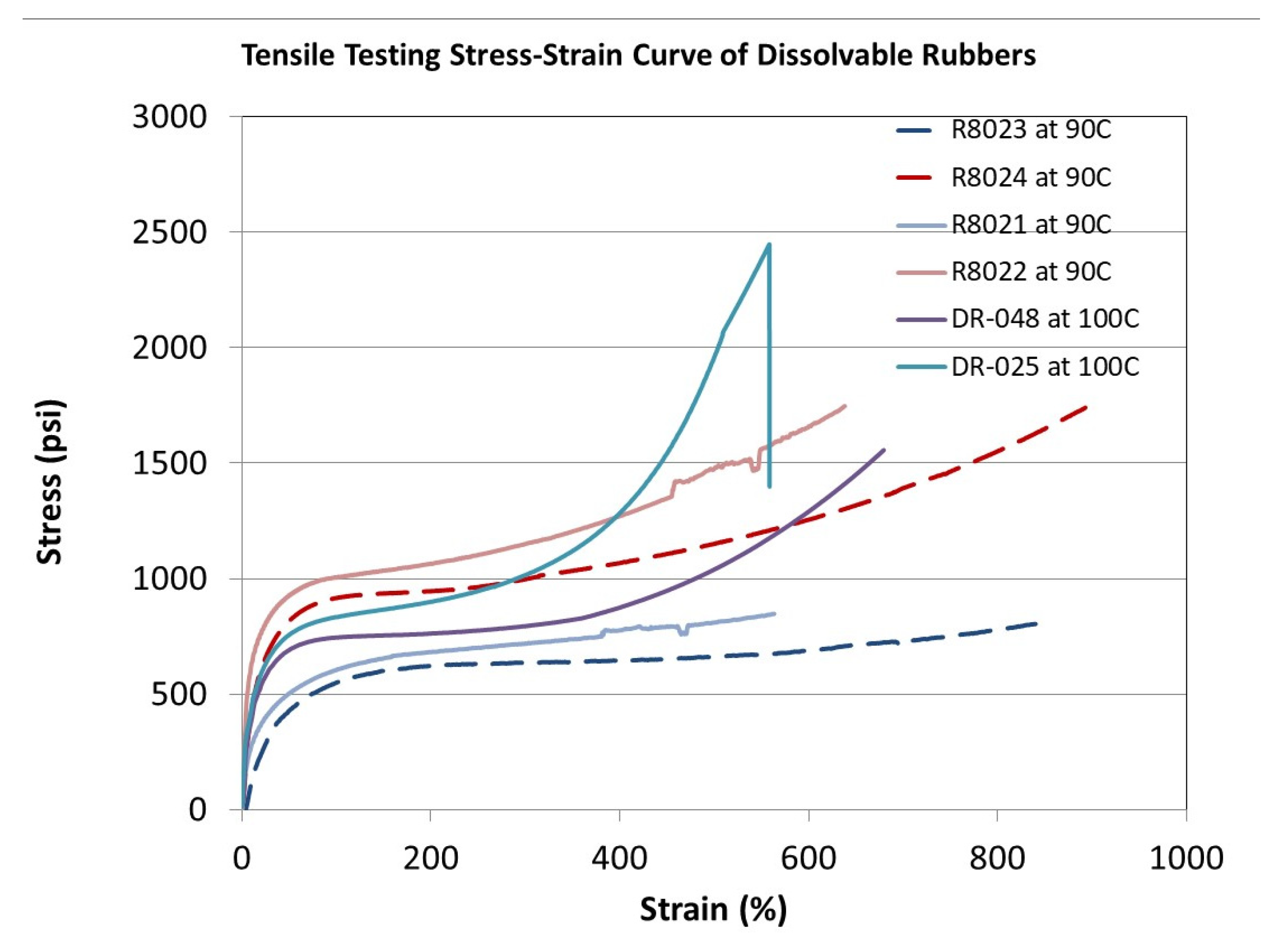

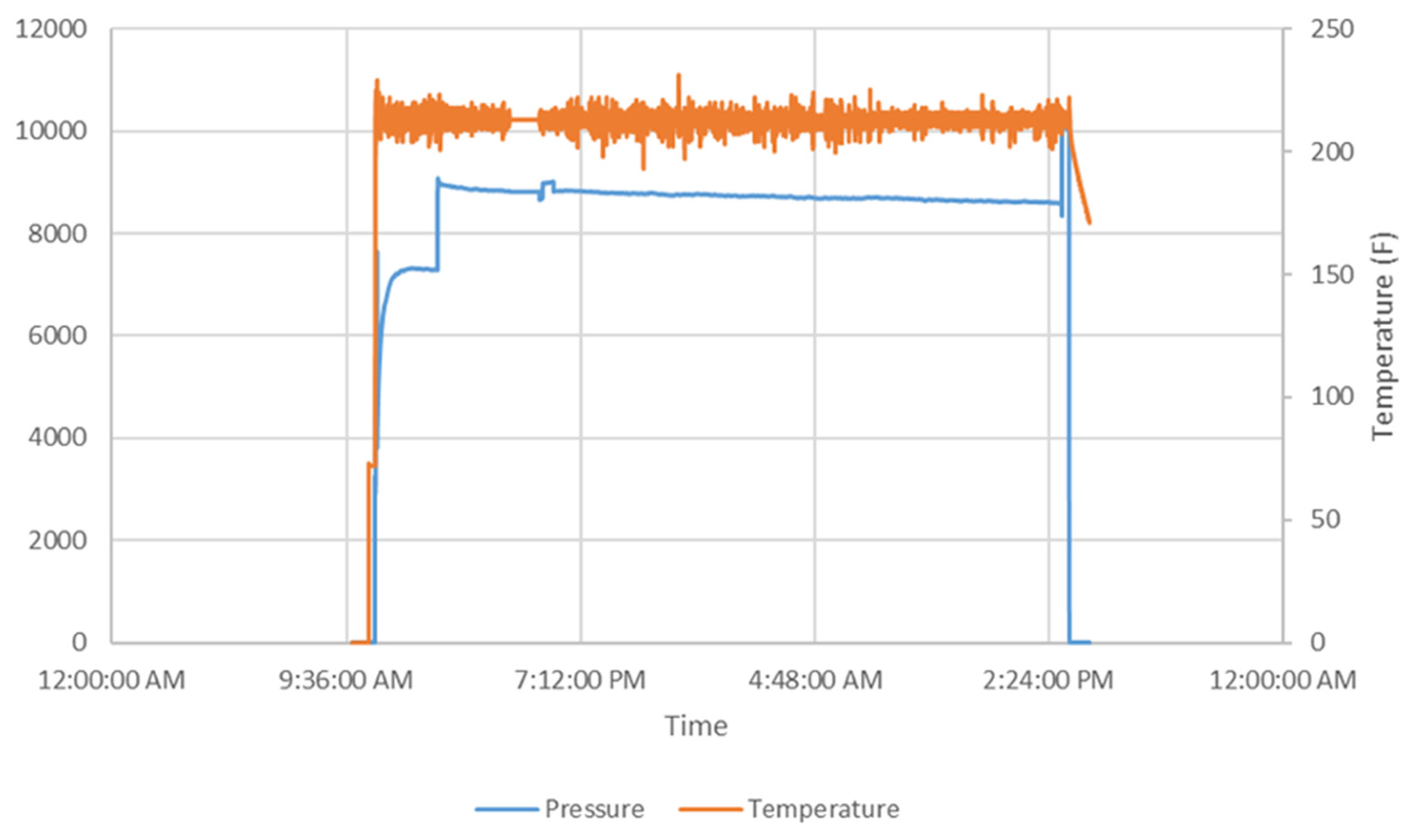

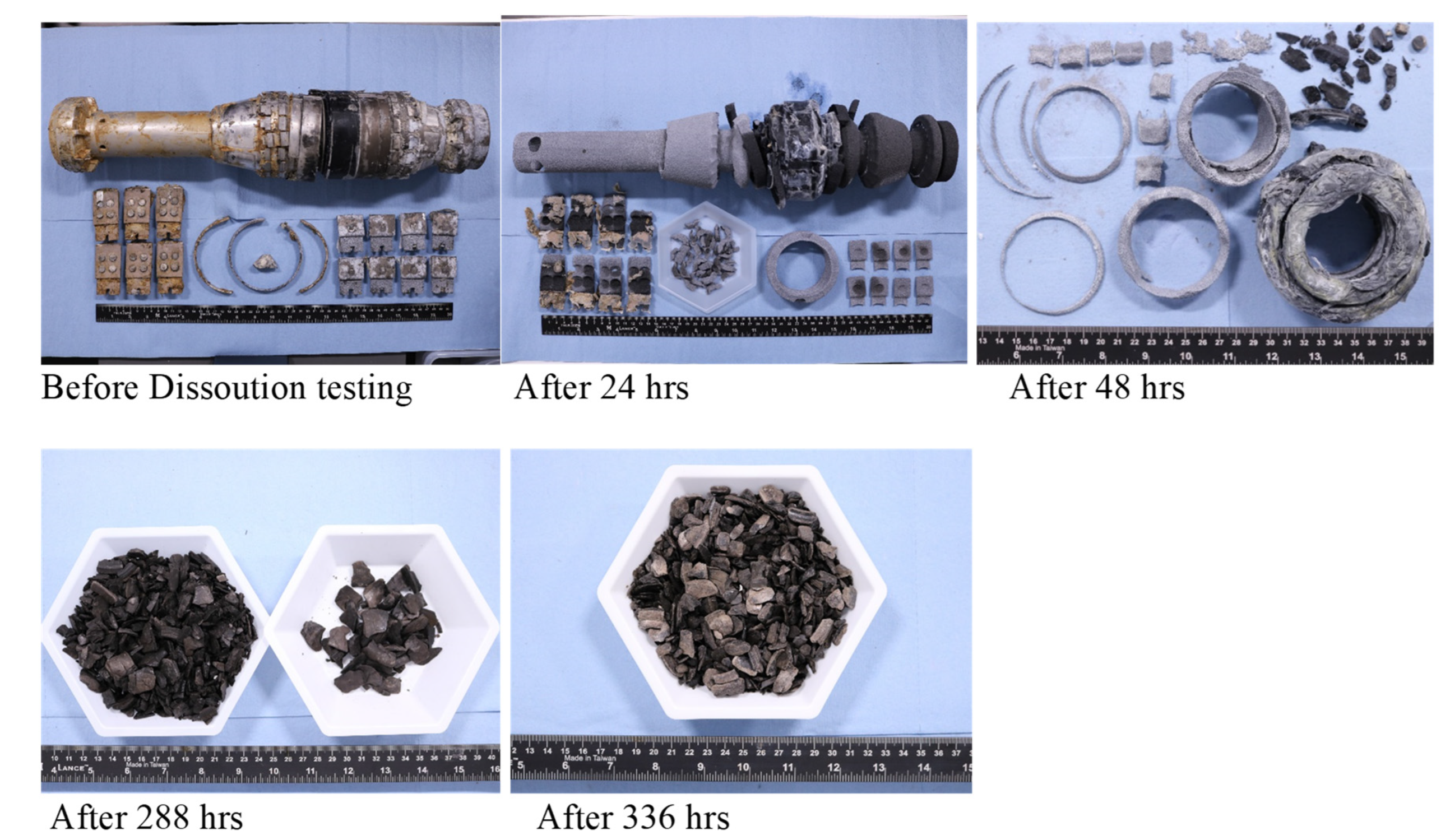

5. Dissolvable/Degradable Rubbers

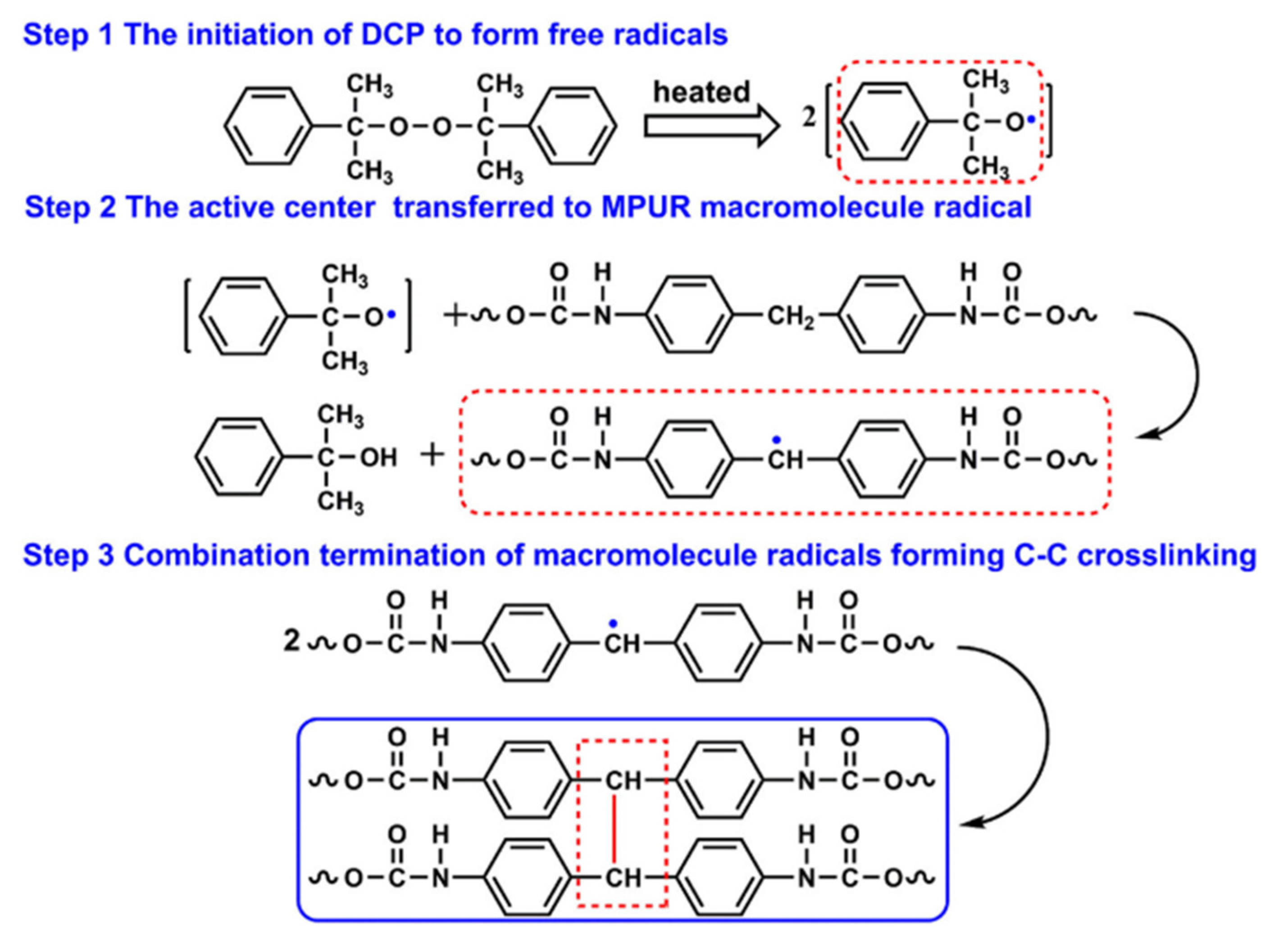

5.1. Development of Dissolvable Rubbers

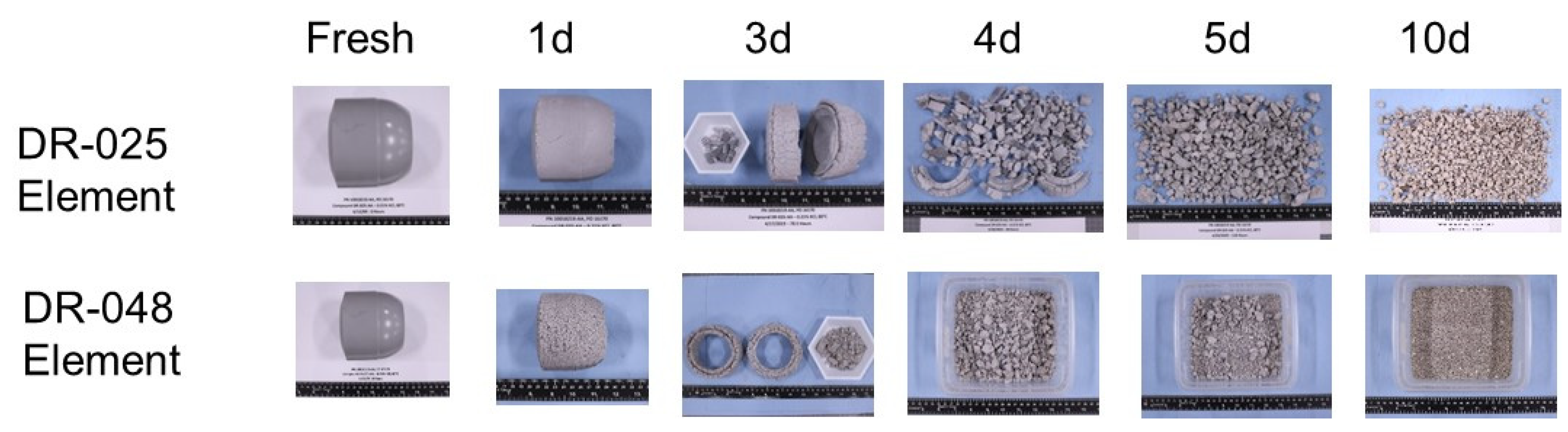

5.2. Low Temperature Dissolvable Rubbers

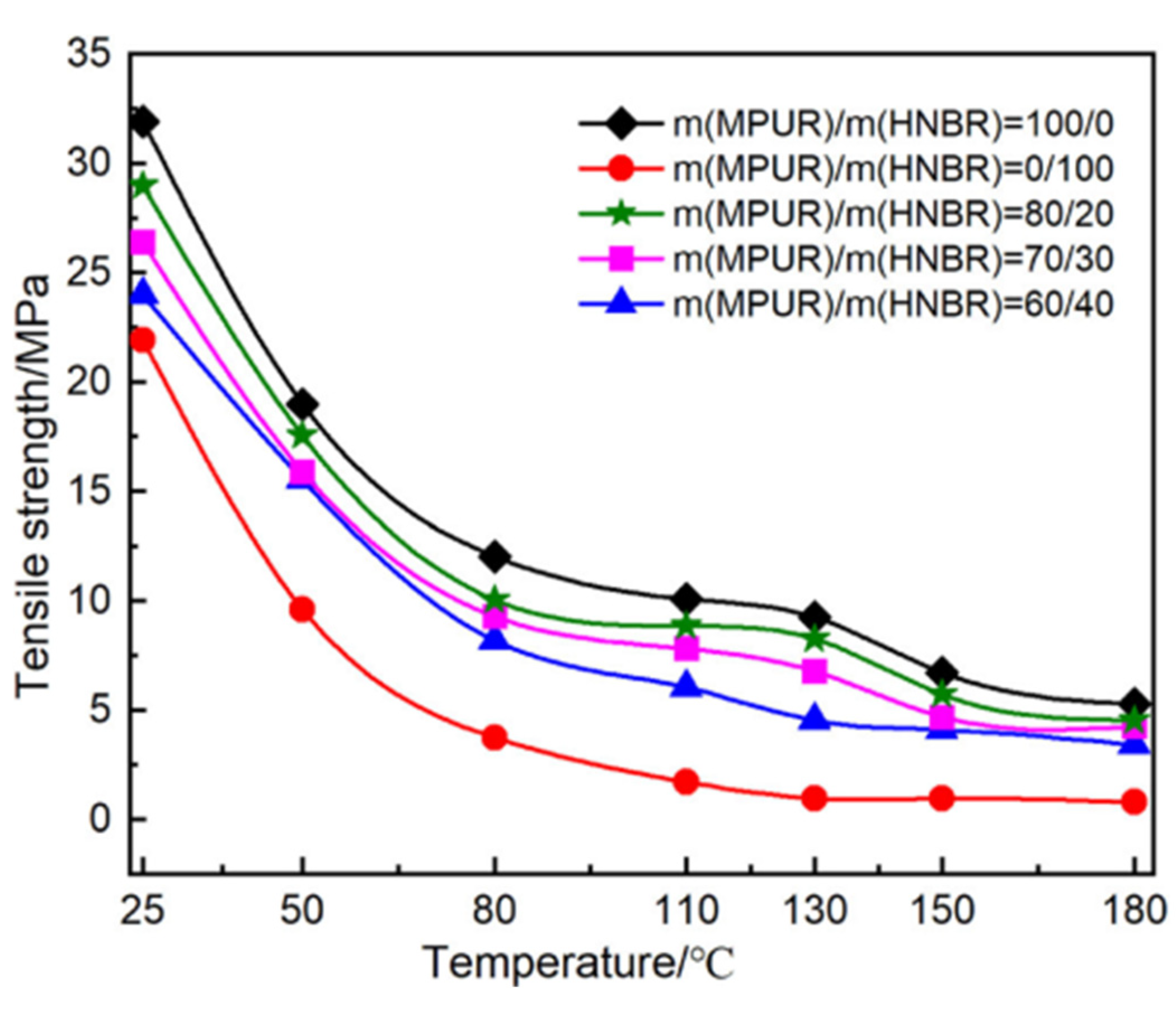

5.3. Medium Temperature Dissolvable Rubbers

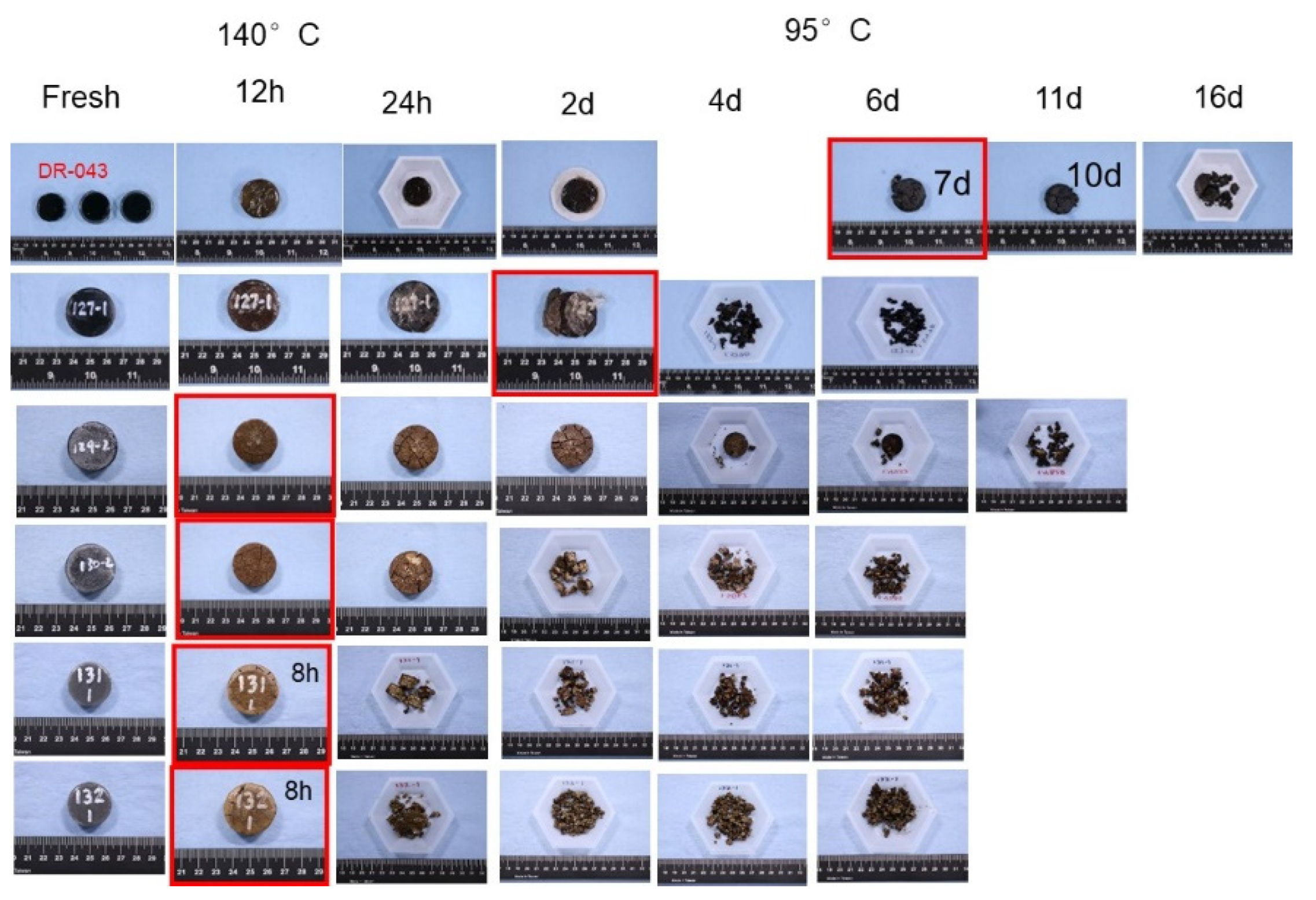

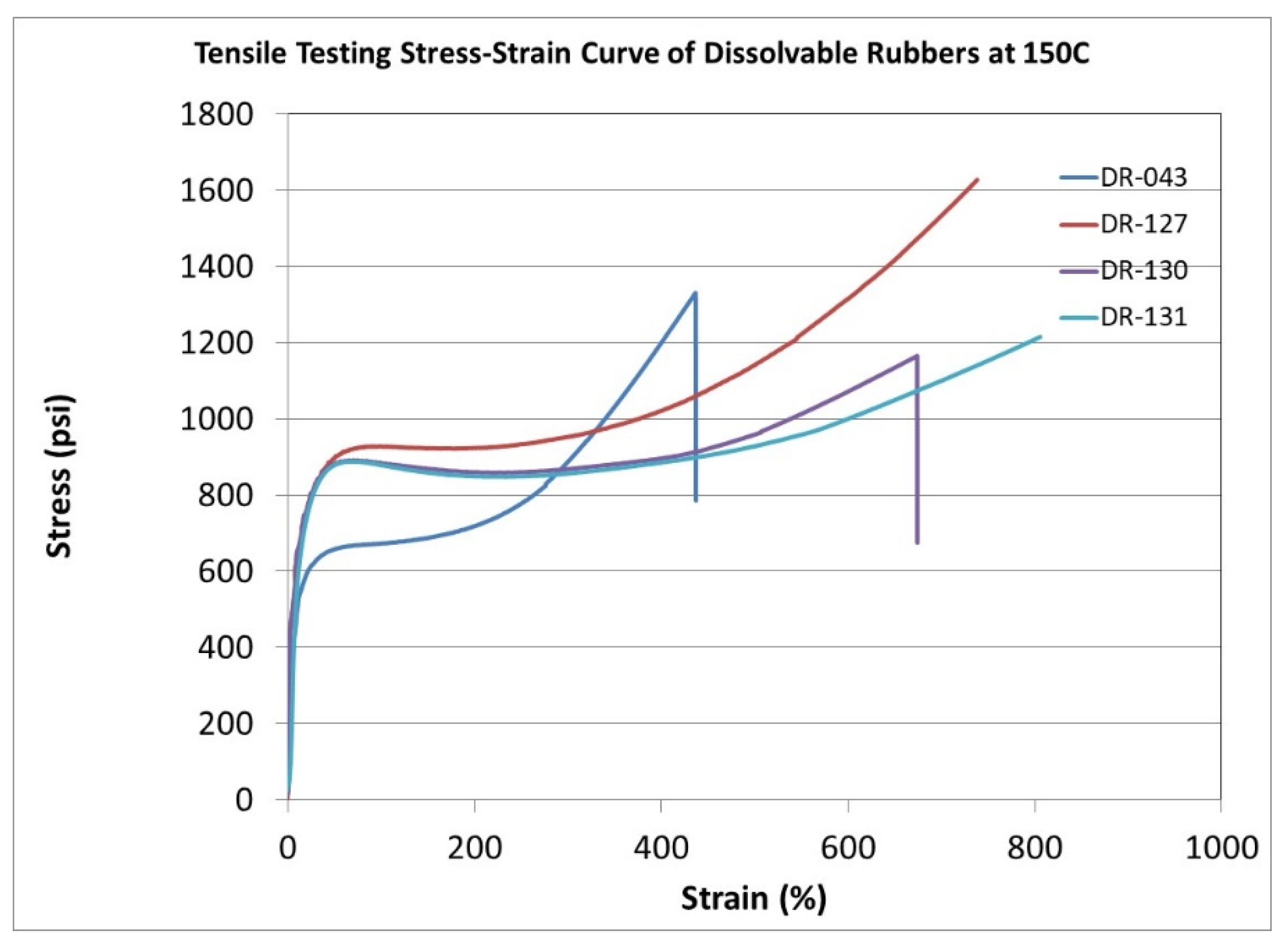

5.4. High Temperature Dissolvable Rubbers

6. Conclusion and Outlook

Acknowledgments

References

- R. Case, L. Zhao, Y. Ding, J. Ren and T. Dunne, "Susceptibility to Localized Corrosion Attack and Application Service Envelopes for Ni Based Corrosion Resistant Alloys in Oil & Gas Production Service Conditions, a Literature Review," in AMPP Annual Conference + Expo, New Orleans, USA, March 2024.

- Y. Yuan and J. Goodson, "Hot-wet Downhole Conditions Affect Composite Selection," Oil & Gas Journal, pp. 52-63, 2007.

- Zhang, P.; Pu, C.; Pu, J.; Wang, Z. Study and Field Trials on Dissolvable Frac Plugs for Slightly Deformed Casing Horizontal Well Volume Fracturing. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 10292–10303, . [CrossRef]

- Walton, Z.; Fripp, M.; Porter, J.; Vargus, G. Evolution of Frac Plug Technologies – Cast Iron to Composites to Dissolvable. SPE Middle East Oil and Gas Show and Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, BahrainDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

- Zhao, L.; Dunne, T.R.; Ren, J.; Cheng, P. "Dissolvable Magnesium Alloys in Oil and Gas Industry," in Magnesium Alloys - Processing, Potential and Applications, London, UK, IntechOpen, 2023.

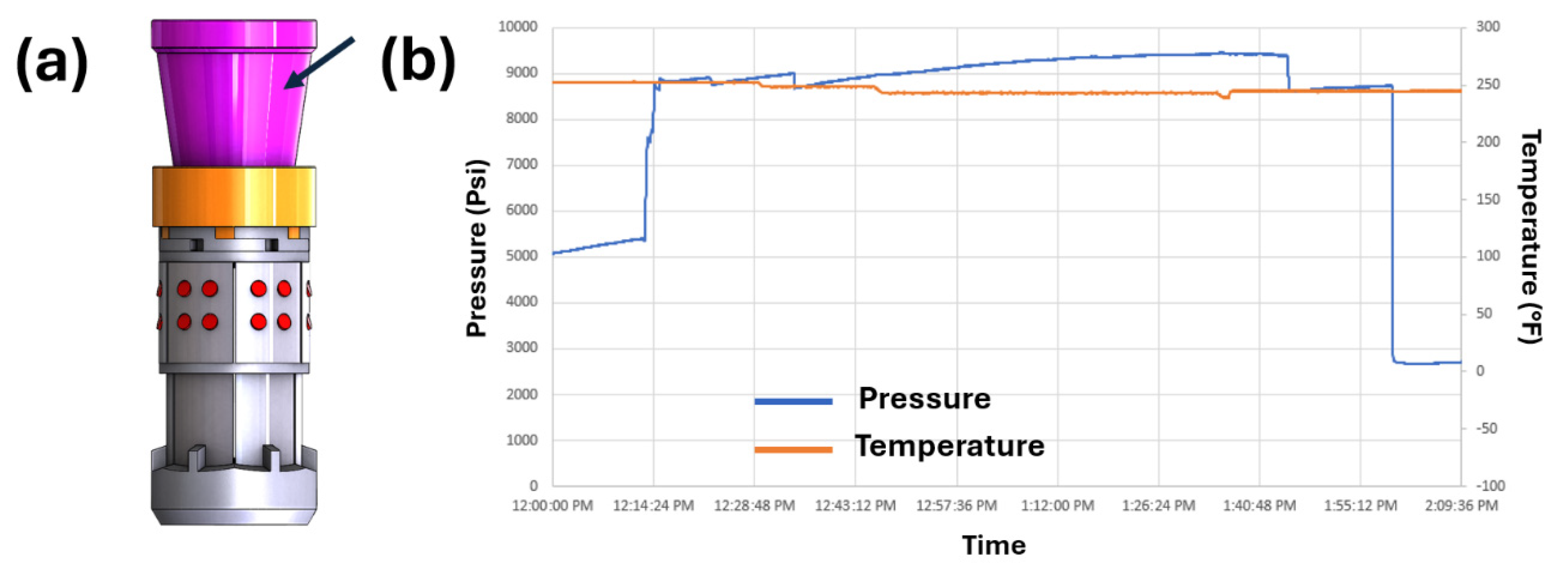

- Zhao, L.; Ren, J.X.; Yuan, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.L.; Zhou, C.J.; Wang, S.W.; Ren, G.F.; Cheng, P. Novel Hybrid Degradable Plugs to Enable Acid Fracturing at High Temperature High Pressure Conditions. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

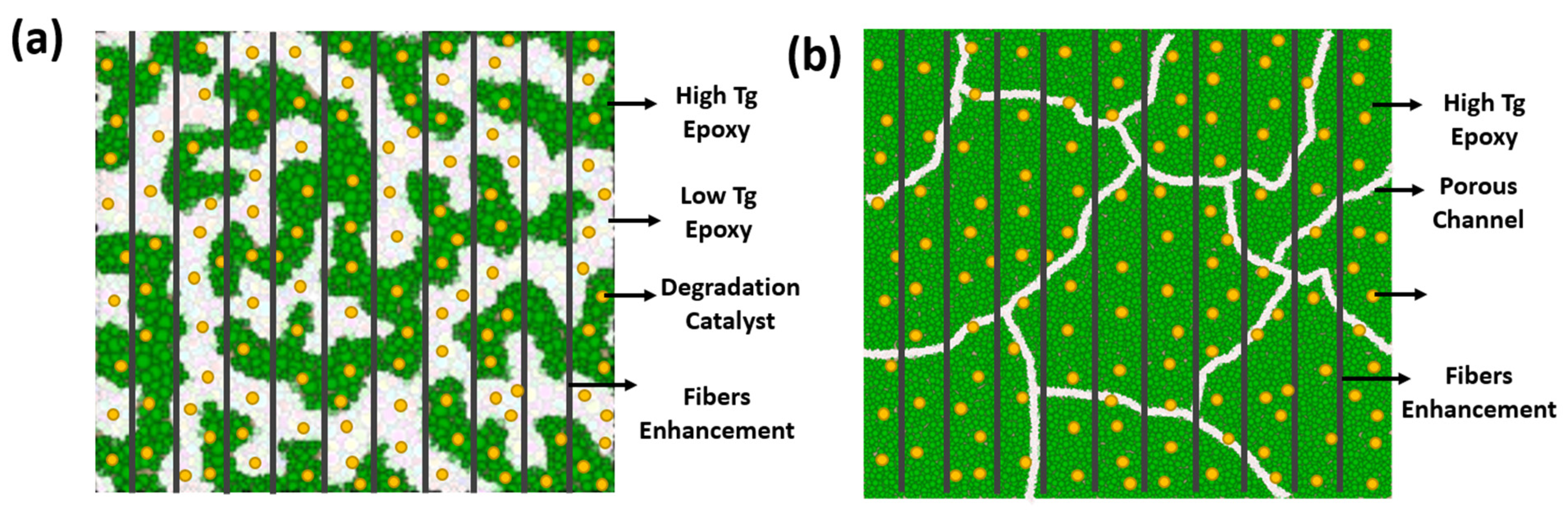

- Zhao, L.; Ren, J.; Dunne, T.; Cheng, P. "Technical Route to DeveloP High-Tg Epoxy Composite That Is Water Degradable at Low Temperature," in TMS Annual Meeting & Exhibition, Orlando, Florida, USA, February 2024.

- Nair, L.S.; Laurencin, C.T. Biodegradable polymers as biomaterials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 762–798, . [CrossRef]

- Post, W.; Susa, A.; Blaauw, R.; Molenveld, K.; Knoop, R.J.I. A Review on the Potential and Limitations of Recyclable Thermosets for Structural Applications. Polym. Rev. 2019, 60, 359–388, . [CrossRef]

- Göpferich, "Mechanisms of polymer degradation and erosion," Biomaterials, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 103-114, 1996.

- Tsuda, K. Behavior and Mechanisms of Degradation of Thermosetting Plastics in Liquid Environments. J. Jpn. Pet. Inst. 2007, 50, 240–248, . [CrossRef]

- Vaidya and K. Spoo, "Performance and Cost Comparison of Stainless-steel and E-CR-FRP Composites in Corrosive Environments," in Corrosion 2014, San Antonio, USA, 2014.

- G. Oliveux, L. O. Dandy and G. A. Leeke, "Current status of recycling of fibre reinforced polymers: Review of technologies, reuse and resulting properties," Progress in Materials Science, vol. 72, pp. 61-99, 2015.

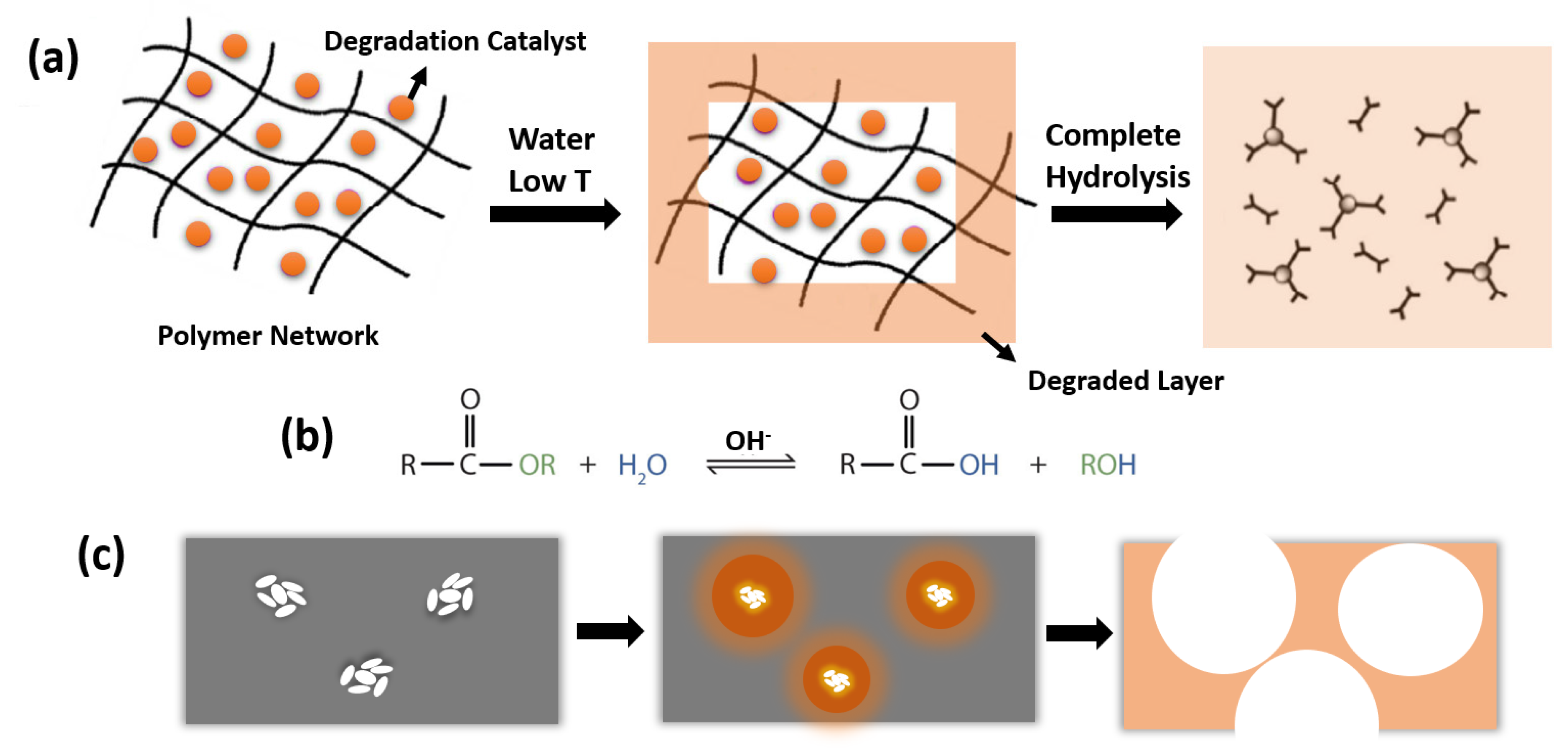

- Xu, Z.; Agrawal, G.; Salinas, B.J. Smart Nanostructured Materials Deliver High Reliability Completion Tools for Gas Shale Fracturing. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

- Shen, M.; Almallahi, R.; Rizvi, Z.; Gonzalez-Martinez, E.; Yang, G.; Robertson, M.L. Accelerated hydrolytic degradation of ester-containing biobased epoxy resins. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 3217–3229, . [CrossRef]

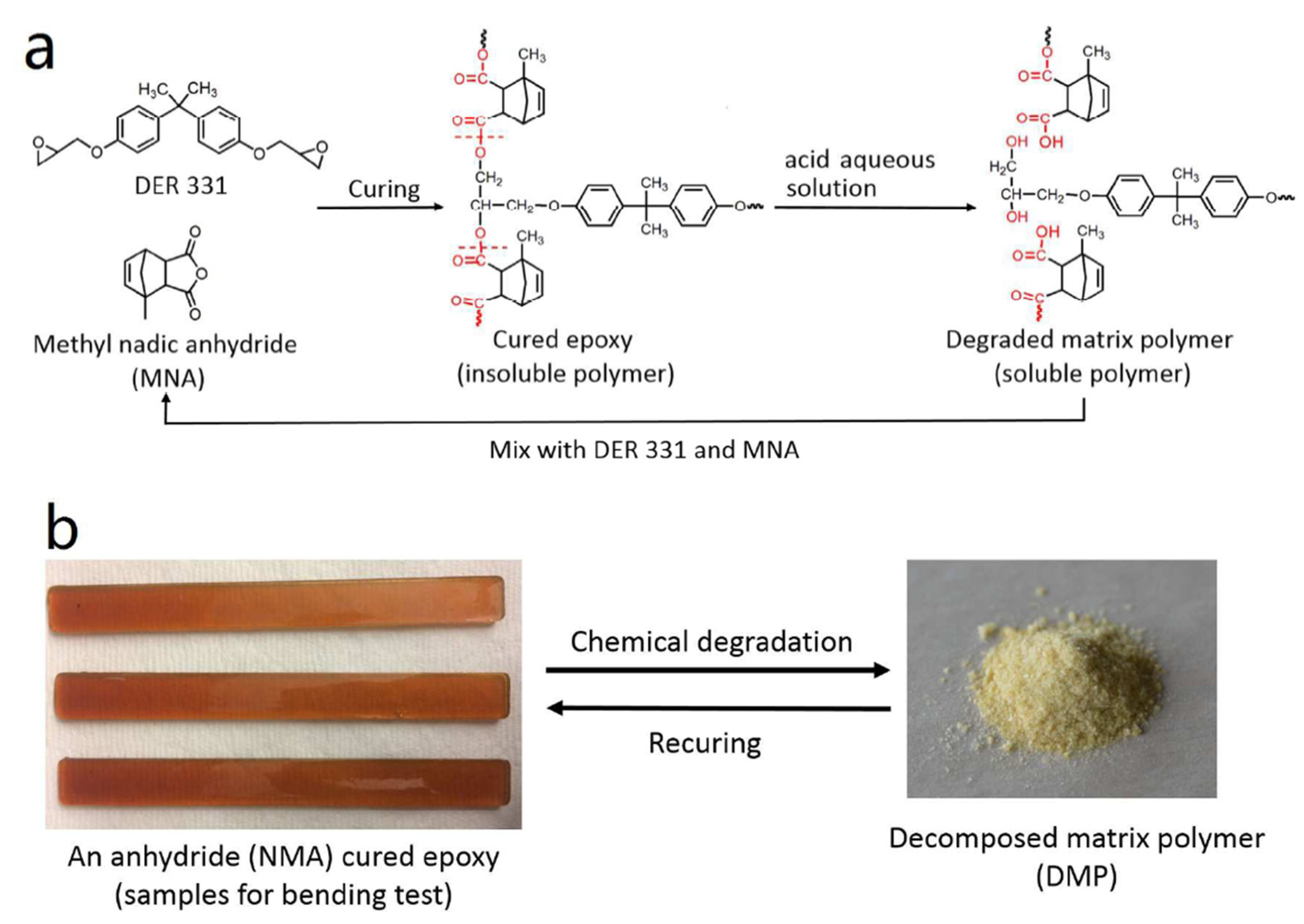

- Liu, T.; Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Hao, C.; Wang, L.; Hiscox, W.C.; Liu, C.; Jin, C.; Xin, J.; Zhang, J. Selective cleavage of ester linkages of anhydride-cured epoxy using a benign method and reuse of the decomposed polymer in new epoxy preparation. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 4364–4372, . [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.T.; Thill, B.P.; Fairchok, W.J. "Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline): A NeW Water- and Organic-Soluble Adhesive," Advances in Chemistry, vol. 213, ppJ. 425-433, 1986.

- B. Wang, Q. Wang and L. Li, "Morphology and properties of highly talc- and CaCO3-filled poly(vinyl alcohol) composites prepared by melt processing," Journal of Applied Polymer Science, vol. 130, no. 5, pp. 3050-3057, 2013.

- Hydrolysis of condensation polymers," Polymer Properties Database, 2015. [Online]. Available: polymerdatabase.com.

- C. Hassan, P. Trakampan and N. A. Peppas , "Water Solubility Characteristics of Poly(vinyl alcohol) and Gels Prepared by Freezing/Thawing Processes," in Water Soluble Polymers, New York, USA, Springer Nature, 2002, pp. 31-40.

- Nishino, T.; Kani, S.; Gotoh, K.; Nakamae, K. Melt processing of poly(vinyl alcohol) through blending with sugar pendant polymer. Polymer 2002, 43, 2869–2873, . [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.K.; Bhalla, R. Advances in the Production of Poly(Lactic Acid) Fibers. A Review. J. Macromol. Sci. Part C: Polym. Rev. 2003, 43, 479–503, . [CrossRef]

- KURALON K-II," Kuraray, 2015. [Online]. Available: https://www.kuraray.com/products/k2.

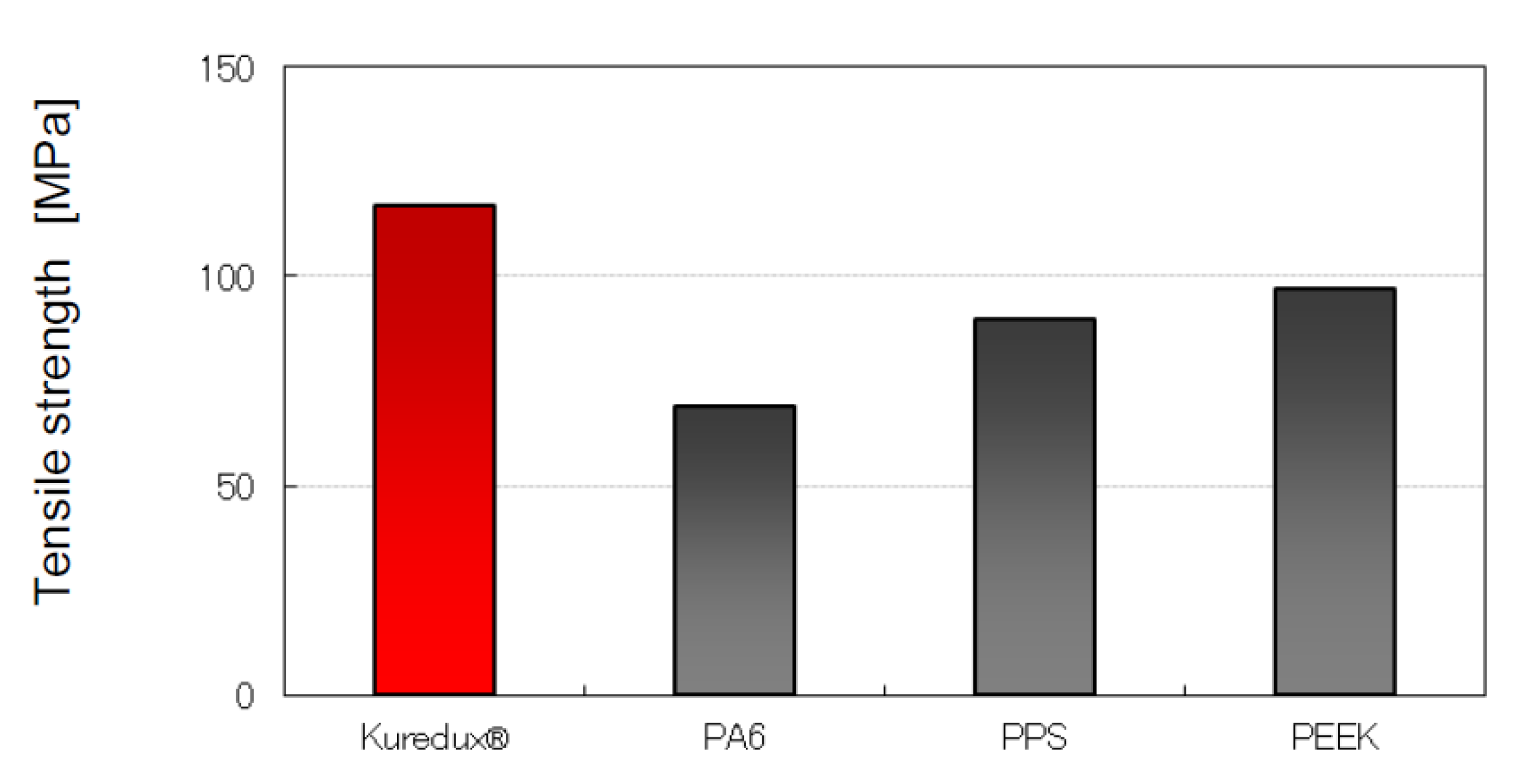

- Mechanical Properties," Kureha, 2015. [Online]. Available: https://www.kuredux.com/en/about/properties.html.

- Wyatt, T.P.; Chien, A.; Kumar, S.; Yao, D. Development of a gel spinning process for high-strength poly(ethylene oxide) fibers. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2014, 54, 2839–2847, . [CrossRef]

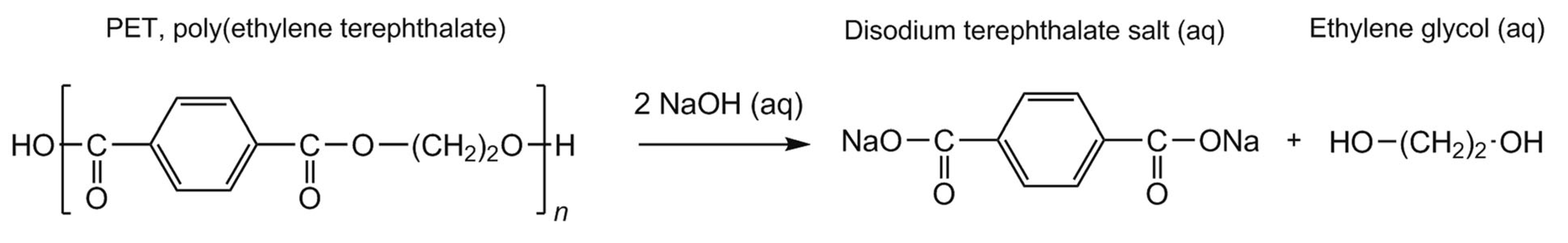

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Han, W.; Yi, H.; Wang, J.; Xing, P.; Ren, J.; Yao, D. Toward Making Poly(ethylene terephthalate) Degradable in Aqueous Environment. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2021, 307, 2100832, . [CrossRef]

- Palme, A.; Peterson, A.; de la Motte, H.; Theliander, H.; Brelid, H. Development of an efficient route for combined recycling of PET and cotton from mixed fabrics. Text. Cloth. Sustain. 2017, 3, 1–9, . [CrossRef]

- Rydz, J.; Sikorska, W.; Kyulavska, M.; Christova, D. Polyester-Based (Bio)degradable Polymers as Environmentally Friendly Materials for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 564–596, doi:10.3390/ijms16010564.

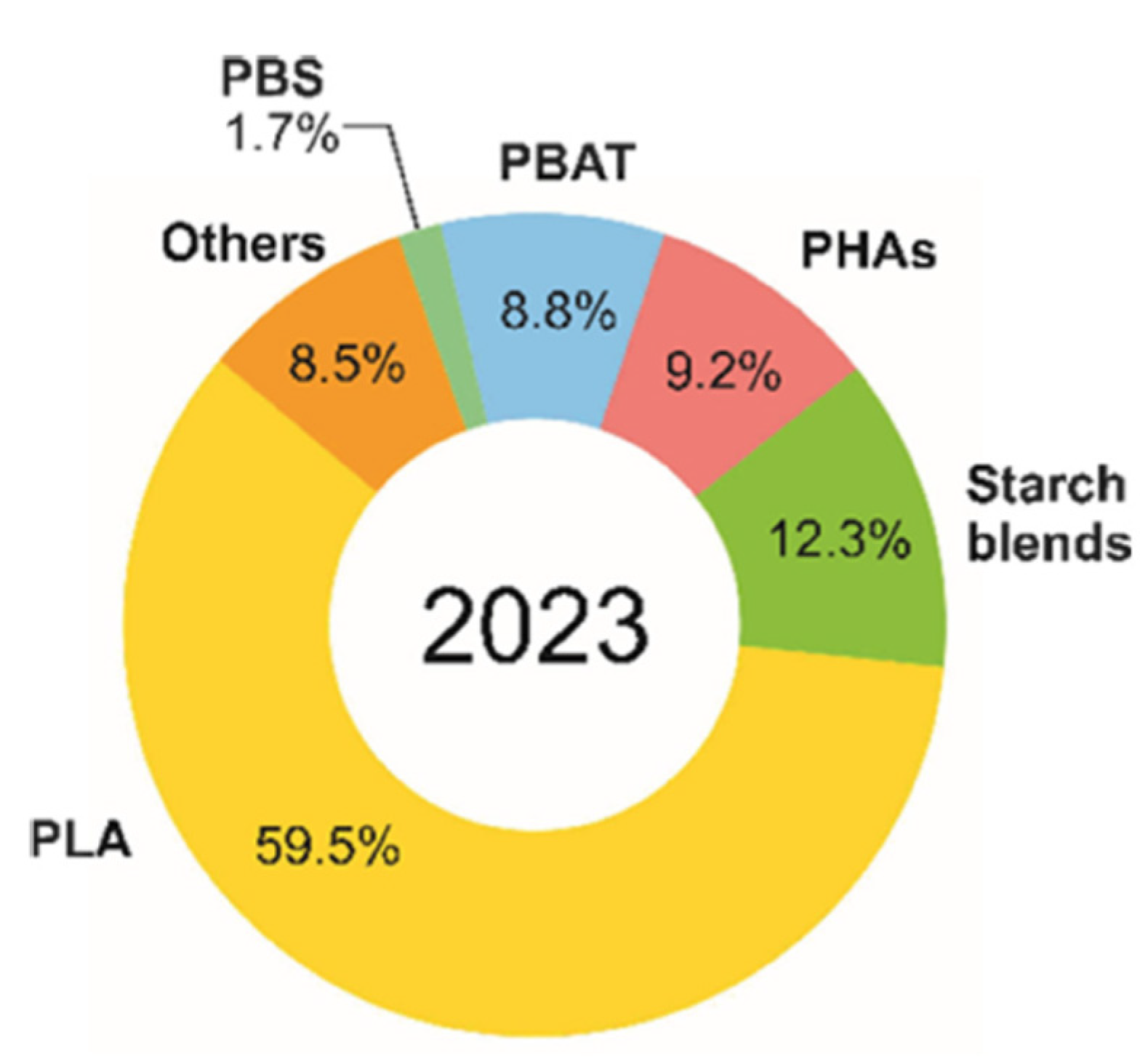

- V. Oliver-Cuenca, V. Salaris, P. F. Muñoz-Gimena, Á. Agüero, M. A. Peltzer, V. A. Montero, M. P. Arrieta, J. Sempere-Torregrosa, C. Pavon, M. D. Samper, G. R. Crespo, J. M. Kenny, . D. López and L. Peponi, "Bio-Based and Biodegradable Polymeric Materials for a Circular Economy," Polymers, no. 16, pp. 3015-3095, 2024.

- Asri, N.A.; Sezali, N.A.A.; Ong, H.L.; Pisal, M.H.M.; Lim, Y.H.; Fang, J. Review on Biodegradable Aliphatic Polyesters: Development and Challenges. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2024, 45, e2400475, . [CrossRef]

- Yield10 Bioscience, Inc.," [Online]. Available: https://www.yield10bio.com.

- Barham, P.J.; Keller, A.; Otun, E.L.; Holmes, P.A. Crystallization and morphology of a bacterial thermoplastic: poly-3-hydroxybutyrate. J. Mater. Sci. 1984, 19, 2781–2794, . [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.; Dong, L.; An, Y.; Feng, Z.; Avella, M.; Martuscelli, E. Miscibility and Crystallization of Poly(β-hydroxybutyrate) and Poly(p-vinylphenol) Blends. Macromolecules 1997, 30, 2726–2733, . [CrossRef]

- P. Xing, X. Ai, L. Dong and Z. Feng, "Miscibility and Crystallization of Poly(beta-hydroxybutyrate) and Poly(vinyl acetate-co-vinyl alcohol) Blends," Macromolecules, vol. 31, pp. 6898-6907, 1998.

- Roohi, M. R. Zaheer and M. Kuddus, "PHB (poly-β-hydroxybutyrate) and its enzymatic degradation," Polymers Advanced technologies, vol. 29, pp. 30-40, 2018.

- NatureWorks, LLC, [Online]. Available: https://www.natureworksllc.com/.

- Malikmammadov, E.; Tanir, T.E.; Kiziltay, A.; Hasirci, V.; Hasirci, N. PCL and PCL-based materials in biomedical applications. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2017, 29, 863–893, . [CrossRef]

- K. Cho, J. Lee and P. Xing, "Enzymatic degradation of blends of poly(ε-caprolactone) and poly(styrene-co-acrylonitrile) by Pseudomonas lipase," Journal of Applied Polymer Science, vol. 83, pp. 868-879, 2002.

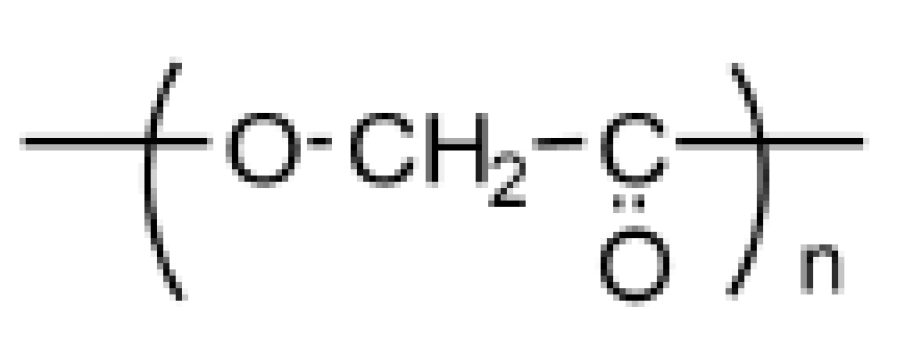

- Kureha Inc.," [Online]. Available: https://www.kureha.co.jp/.

- K. Yamane, H. Sato, . Y. Ichikawa, K. Sunagawa and Y. Shigaki, "Development of an industrial production technology for high-molecular-weight polyglycolic acid," Polymer Journal, pp. 1-7, 2014.

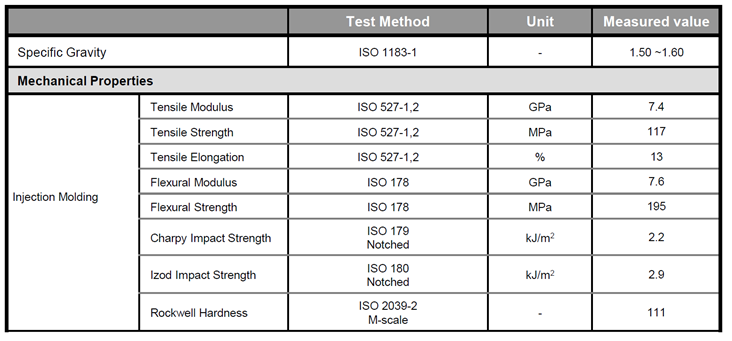

- M. Okura, S. Takahashi, T. Kobayashi, H. Saijo and T. Takahashi, "Improvement of Impact Strength of Polyglycolic Acid for Self-Degradable Tools for Low-Temperature Wells," in SPE Middle East Unconventional Resources Conference and Exhibition, SPE-172969-MS, Muscat, Oman, 2015.

- Kureha Energy Solutions," [Online]. Available: https://kurehadegradableplug.com/.

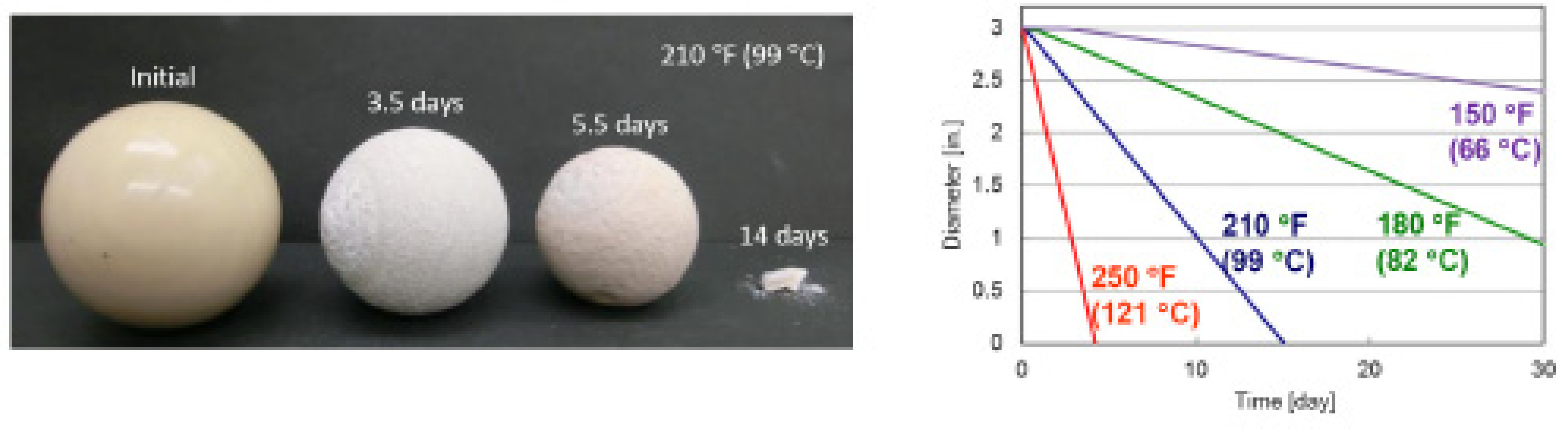

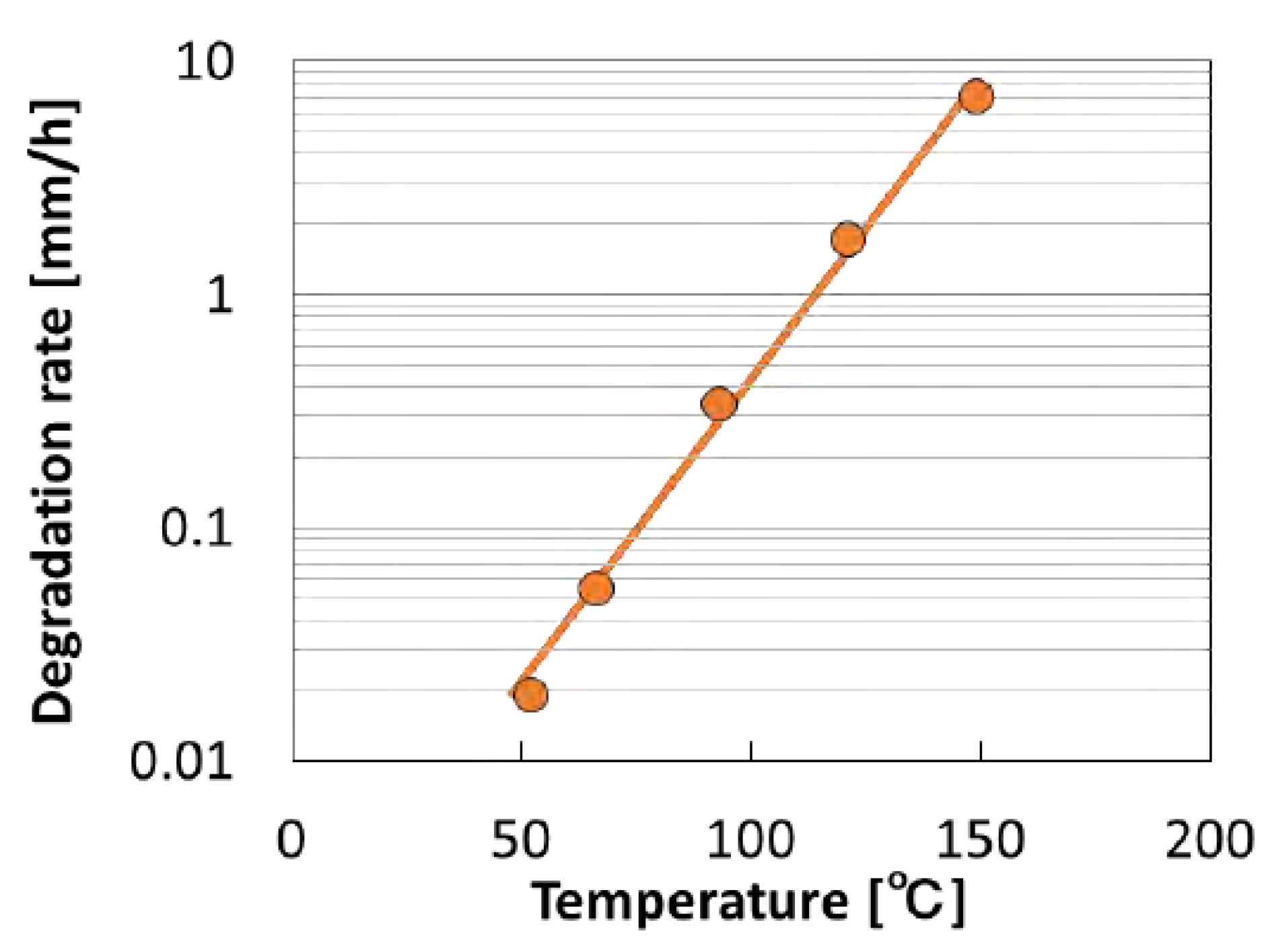

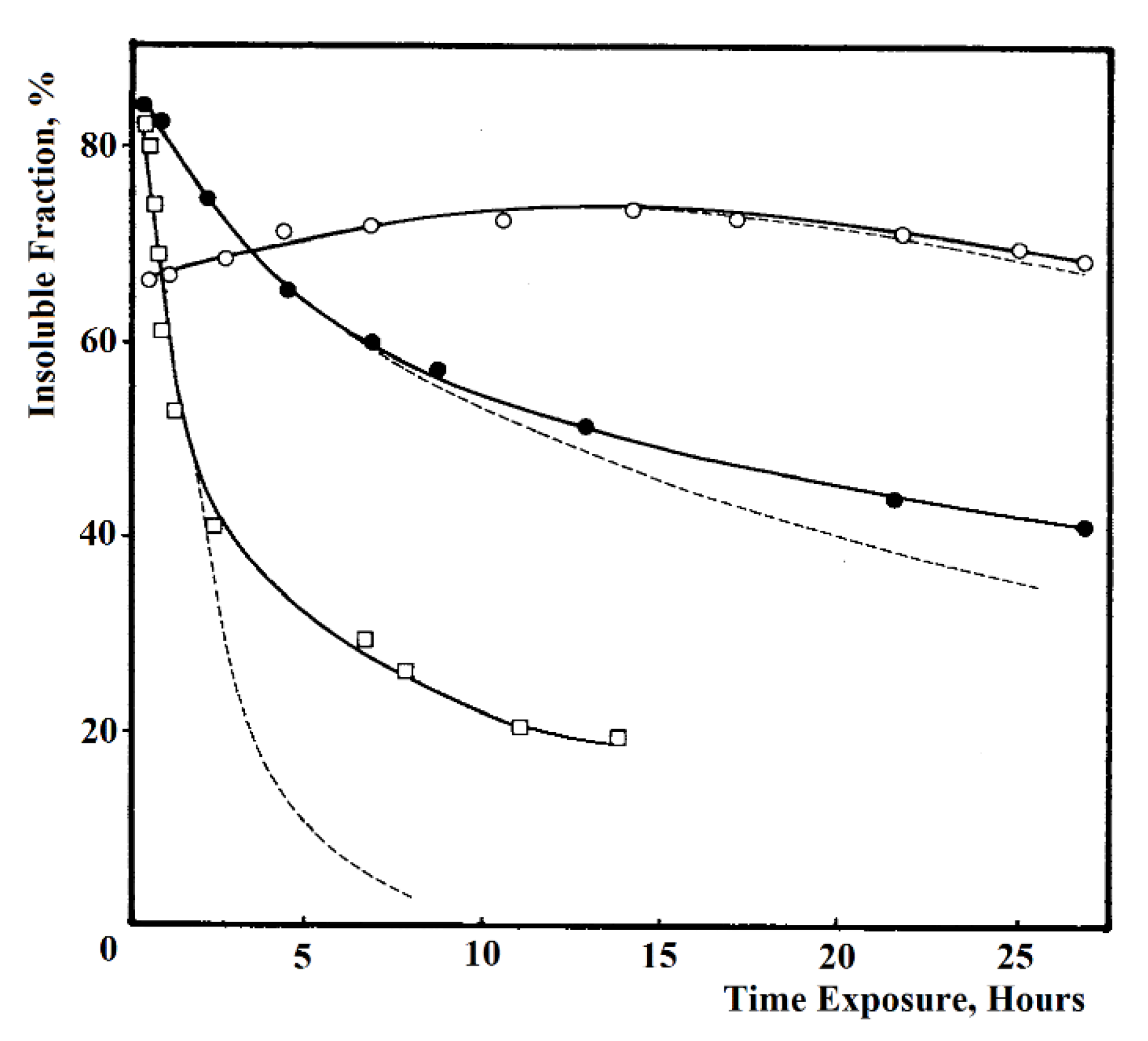

- S. Takahashi, A. Shitsukawa and M. Okura, "Degradation Study on Materials for Dissolvable Frac Plugs," in Unconventional Resources Technology Conference URTeC: 2901283, Houston, USA, 2018.

- P. Xing, W. Zheng, R. Lindemann, D. Wellman, J. Halling, J. Ren, P. Cheng, M. Yuan, J. Chen and D. Yao, "Study of the Properties of Hydrolytic Degradable Polyglycolic Acid and Its Blends with Polylactic Acid, and Its Application in the Dissolvable Plug," in SPE's Annual Technical Conference, ANTEC 2024, St. Louis, USA, 2024.

- Wang, B.; Ma, S.; Yan, S.; Zhu, J. Readily recyclable carbon fiber reinforced composites based on degradable thermosets: a review. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 5781–5796, . [CrossRef]

- Hamerton, Chemistry and Technology of Cyanate Ester Resins, London, UK: Springer Nature, 1994.

- Khatiwada, S.; Duan, P.; Garza, R.; Sadana, A.K. Degradable Thermoset Polymer Composite for Intervention-Less Downhole Tools. Offshore Technology Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

- L. J. Kasehagen, I. Haury, C. W. Macosko and D. A. Shimp, "Hydrolysis and blistering of cyanate ester networks," Journal of Applied Polymer Science, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 107-113, 1997.

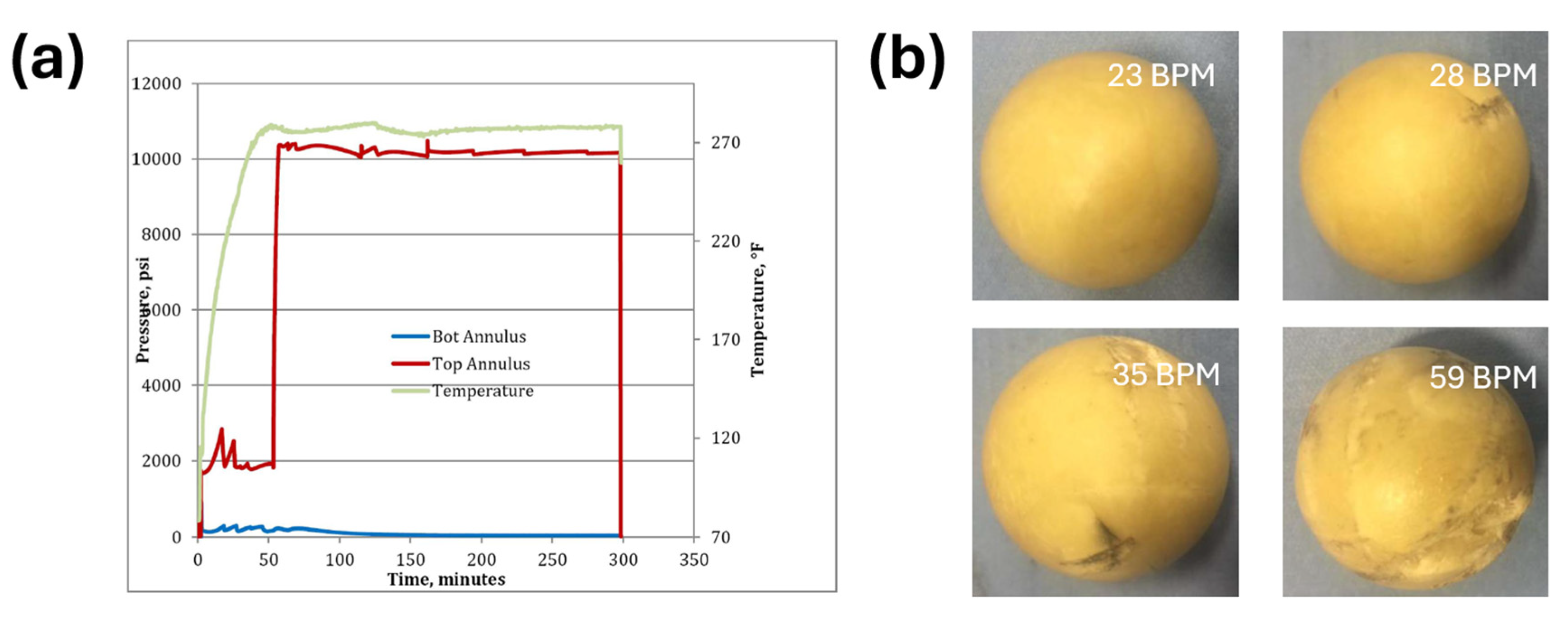

- Garza, R.; Sadana, A.; Khatiwada, S.; Duan, P. Novel Degradable Polymeric Composite Balls for Hydraulic Fracturing. Offshore Technology Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

- Takahashi, A.; Ohishi, T.; Goseki, R.; Otsuka, H. Degradable epoxy resins prepared from diepoxide monomer with dynamic covalent disulfide linkage. Polymer 2016, 82, 319–326, doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2015.11.057.

- Gandini, A. The furan/maleimide Diels–Alder reaction: A versatile click–unclick tool in macromolecular synthesis. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 1–29, . [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhao, F.; Wang, B.; Hu, Z.; Huang, Y. The designing of degradable unsaturated polyester based on selective cleavage activated hydrolysis and its application in recyclable carbon fiber composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 229, . [CrossRef]

- Buchwalter, S.L.; Kosbar, L.L. Cleavable epoxy resins: Design for disassembly of a thermoset. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 1996, 34, 249–260, . [CrossRef]

- S. J. Pastine, "Sterically hindered aliphatic polyamine cross-linking agents, compositions containing them and uses thereof". USA Patent US9862797B2, 9 1 2018.

- P. K. Dubey, S. K. Mahanth and A. Dixit, "Recyclamine® - Novel Amine Building Blocks for a Sustainable World," in SAMPE neXus Proceedings, Virtual, June 2021.

- Dutkiewicz, J. Hydrolytic degradation of cured urea–formaldehyde resin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1983, 28, 3313–3320, . [CrossRef]

- Nuryawan, I. Risnasari, T. Sucipto, A. Heri Iswanto and R. Rosmala Dewi, "Urea-formaldehyde resins: production, application, and testing," in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Medan, Indonesia, November, 2016.

- S. Wang, S. Ma, Q. Li, X. Xu, B. Wang,, W. Yuan, S. Zhou, S. You and J. Zhu, "Facile in situ preparation of high-performance epoxy vitrimer from renewable resources and its application in nondestructive recyclable carbon fiber composite," Green Chemistry, vol. 21, pp. 1484-1497, 2019.

- Alberts, A.H.; Rothenberg, G. Plantics-GX: a biodegradable and cost-effective thermoset plastic that is 100% plant-based. Faraday Discuss. 2017, 202, 111–120, . [CrossRef]

- Kasetaite, S.; Ostrauskaite, J.; Grazuleviciene, V.; Bridziuviene, D.; Rainosalo, E. Biodegradable glycerol-based polymeric composites filled with industrial waste materials. J. Compos. Mater. 2017, 51, 4029–4039, . [CrossRef]

- H. Alberts and G. Rothenberg, "Composite material comprising bio-filler and specific polymer". United States Patent US10036122B2, 31 7 2018.

- Yang, F.; A Hanna, M.; Sun, R. Value-added uses for crude glycerol--a byproduct of biodiesel production. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2012, 5, 13–13, . [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yan, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, X.; Jia, L. Multiply fully recyclable carbon fibre reinforced heat-resistant covalent thermosetting advanced composites. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14657, . [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xing, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Jing, X. Room-temperature fully recyclable carbon fibre reinforced phenolic composites through dynamic covalent boronic ester bonds. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 10868–10878, . [CrossRef]

- R. d. Luzuriaga, R. Martin, N. Markaide, A. Rekondo, G. Cabañero, J. Rodríguez and I. Odriozola, "Epoxy resin with exchangeable disulfide crosslinks to obtain reprocessable, repairable and recyclable fiber-reinforced thermoset composites," Materials Horizons, vol. 3, pp. 241-247, 2016.

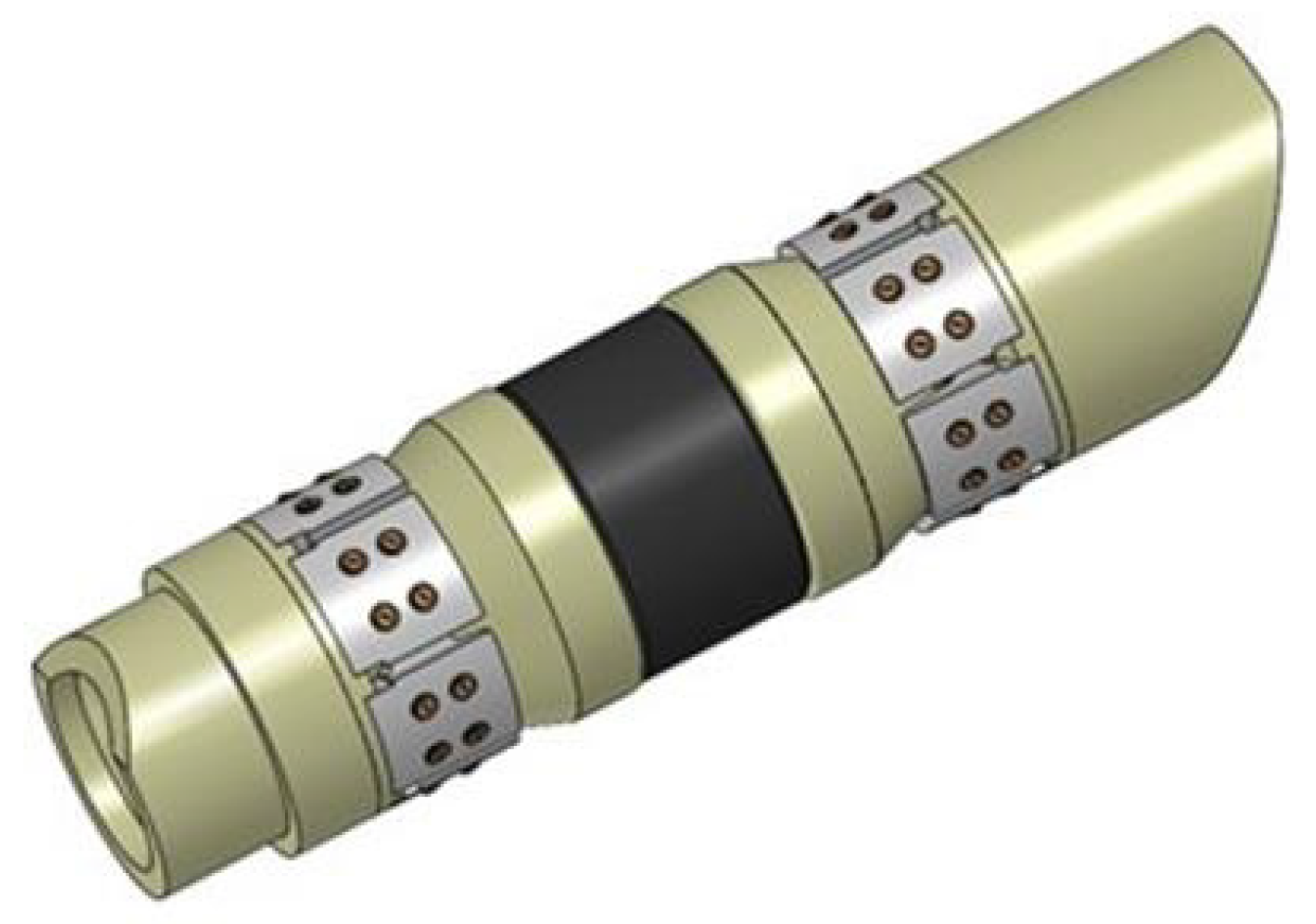

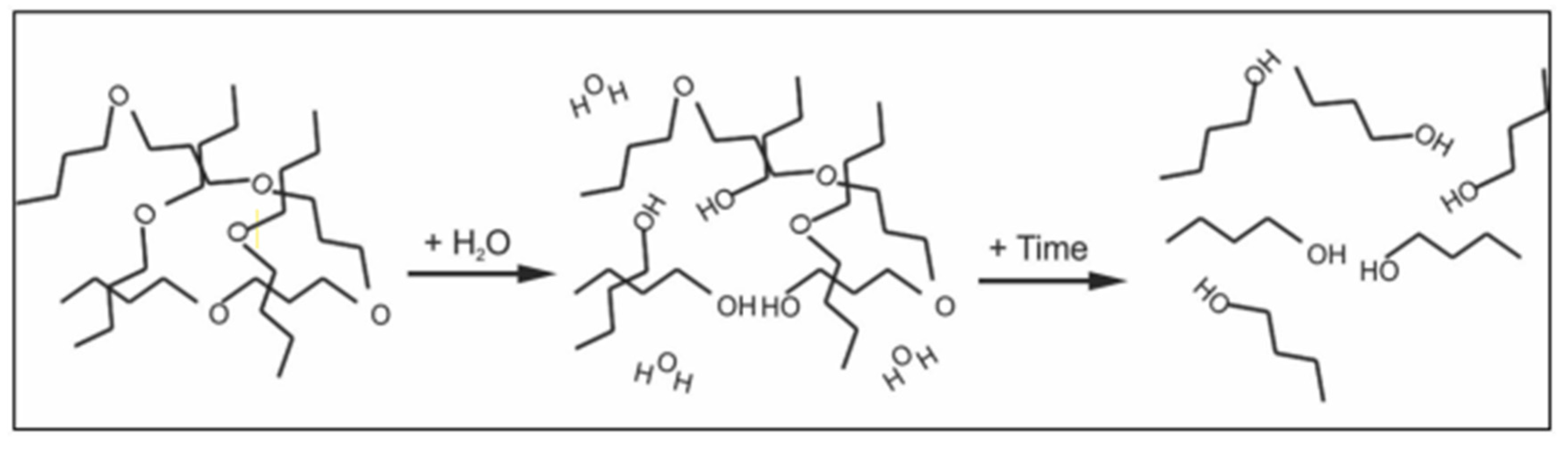

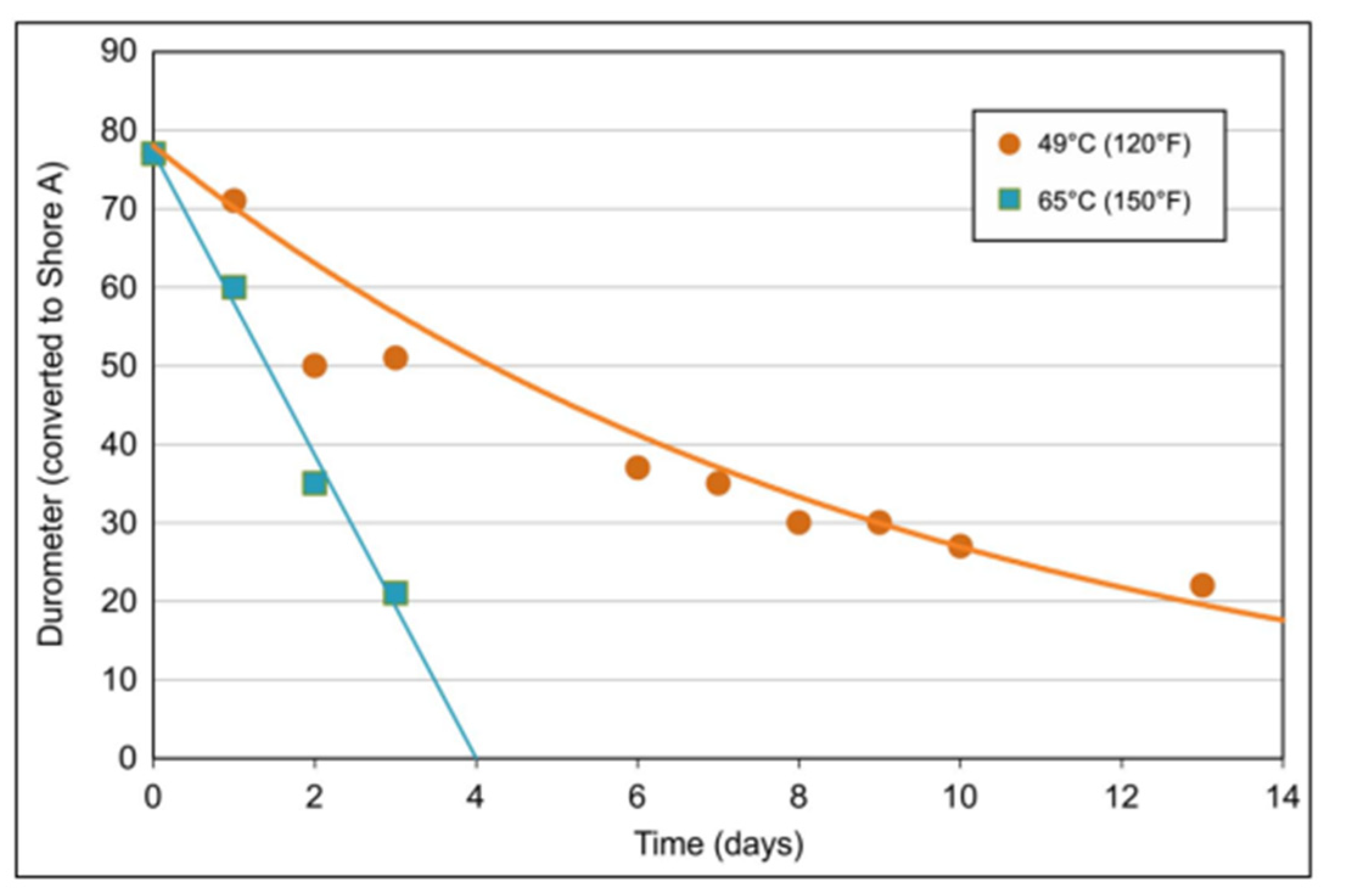

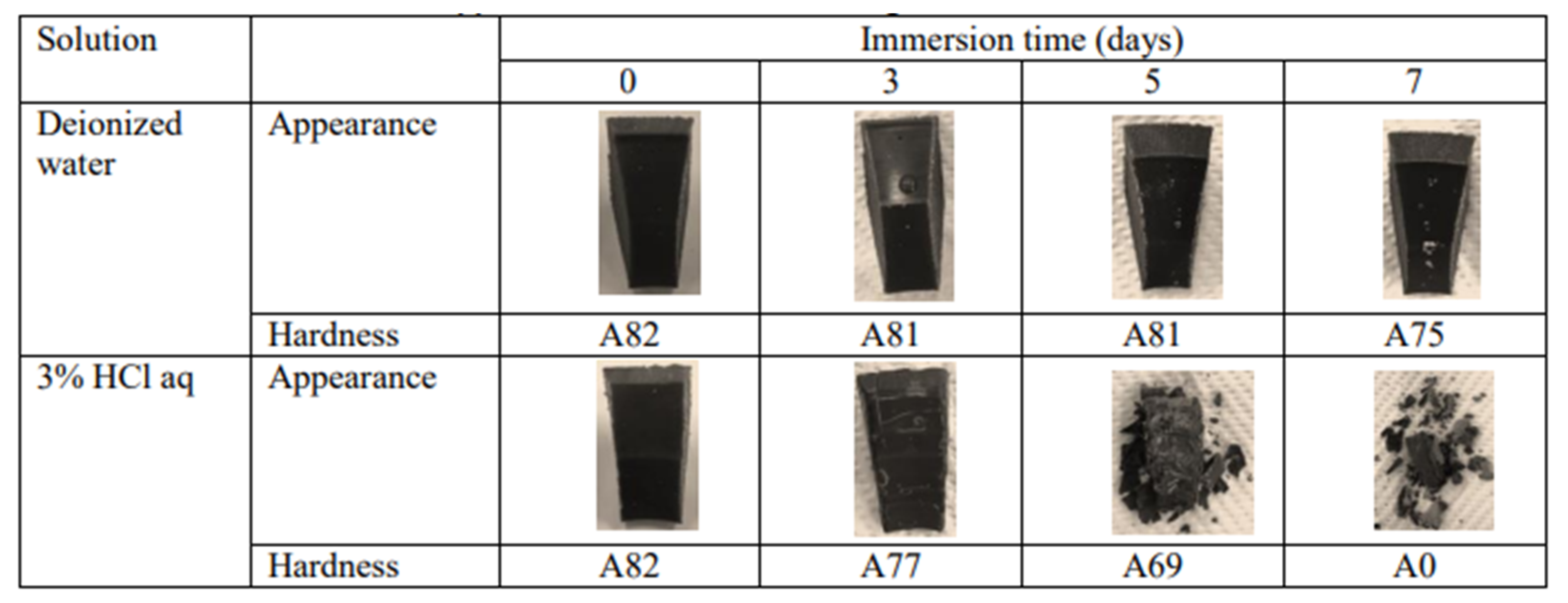

- Takahashi, T.; Takahashi, S.; Okura, M. Development of Degradable Seal Elements for Fully Degradable Frac Plugs. Offshore Technology Conference Asia. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, MalaysiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

- J. Sherman and B. Doud, "Dissolvable Rubber". US Patent 10,544, 304, B2, 28 January 2020.

- Cheng, K.; Shang, L.; Li, H.; Peng, B.; Li, Z. A novel degradable sealing material for the preparation of dissolvable packer rubber barrel. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A 2023, 60, 207–216, . [CrossRef]

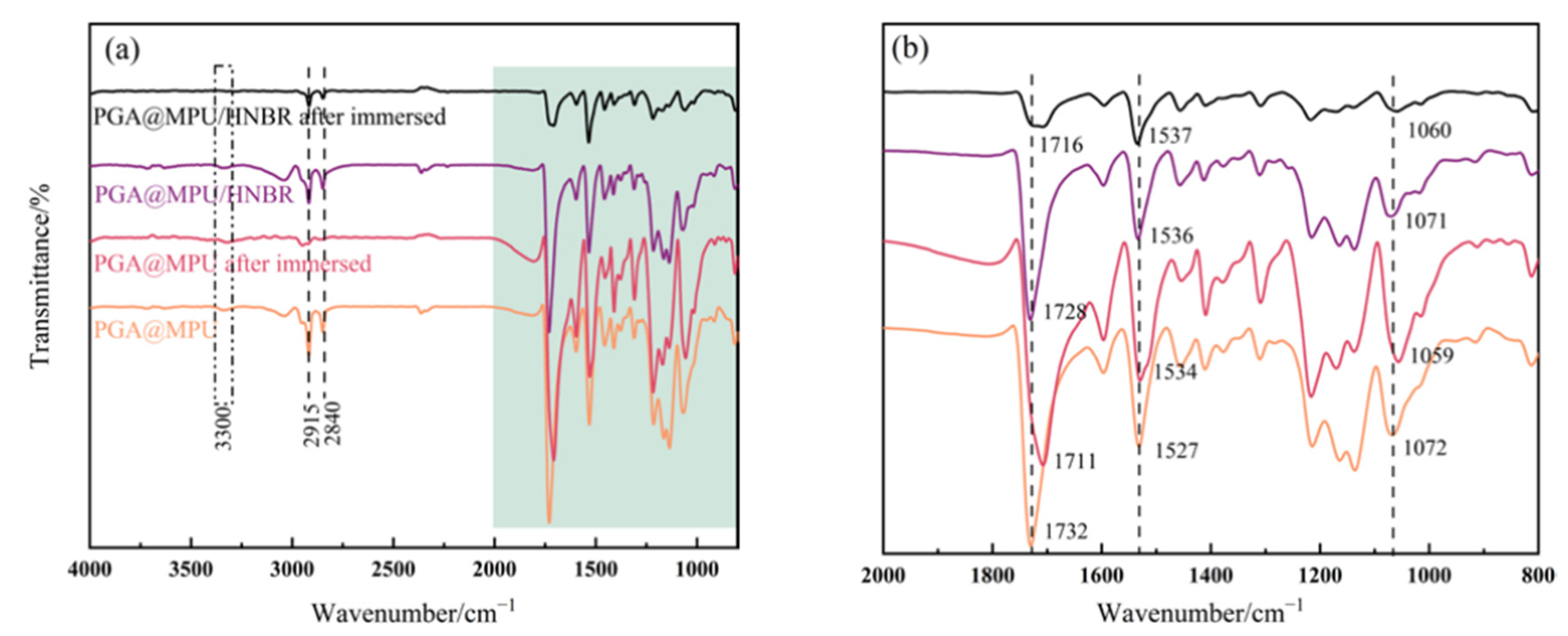

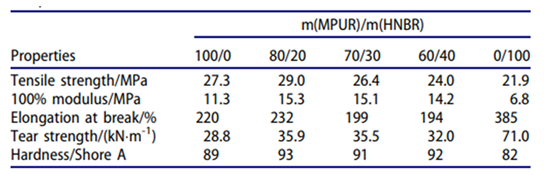

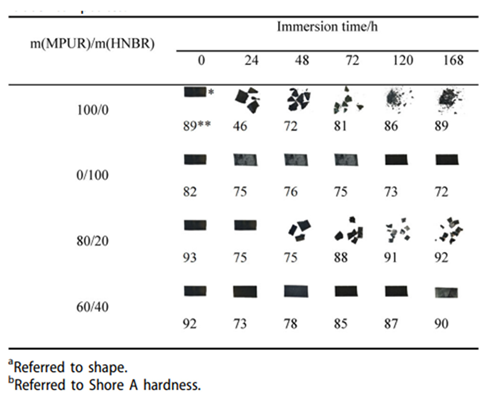

- Cheng, K.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, N.; Peng, B. Application and Properties of Polyglycolic Acid as a Degradation Agent in MPU/HNBR Degradable Elastomer Composites for Dissolvable Frac Plugs. Polymers 2024, 16, 181, . [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, J. Zheng, X. Chen and M. Yang, "A Water-Soluble Rubber and Its Preparation Method". P. R. China Patent 109810451 B, 22 10 2021.

- J. Zheng, Z. Zhang, X. Chen, H. Yang, M. Zhu and M. Yang, "A water-soluble rubber material and its preparation method". P.R.China Patent 109762322, 17 5 2019.

- Duan, P.; Sadana, A.; Xu, Y.; Deng, G.; Pratt, B. Degradable Packing Element for Low-Temperature Fracturing Applications. Offshore Technology Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

- Fripp, M.; Walton, Z.; Norman, T. Fully Dissolvable Fracturing Plug for Low-Temperature Wellbores. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

- Burdzy, M.P. Aqueous Degradable Polyurethane Elastomers for Oil & Gas Applications. Offshore Technology Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

- D. Xu, F. Wang, Z. Lin, J. Sun, J. Ren, Q. Li, B. Zheng and Q. Wang, "Experimental Study on a Water-Soluble Rubber Cylinder Based on Thermosetting Polyester Polyurethane Popolymer," in Proceedings of the International Field Exploration and Development Conference 2020, Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd, 2021, pp. 1783-1792.

- Ren, J.; Cheng, P.; Wang, X. Dissolvable Rubbers Development and its Applications in Downhole Tools. SPE Middle East Oil & Gas Show and Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

- T. Notman, Z. Waltron and M. Fripp, "Full Dissolvable Frac Plug for High-Temperature Wellbores," in Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, 2018.

- 78. .

- Yue, W.; Ren, J.; Yue, J.; Cheng, P.; Dunne, T.; Zhao, L.; Patsy, M.; Nettles, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. High Temperature Dissolvable Materials Development for High Temperature Dissolvable Plug Applications. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; .

| Performance | High strength | High thermal stability | Controllable dissolvability |

| Property | a. High tensile strength b. High stiffness (compared with rubber) c. High flexural strength d. High flexural modulus |

a. High Tg b. High Tm c. High HDT d. Delayed degradation |

a. Proper water solubility b. Proper hydrolysis rate c. Proper thermal degradation rate d. Disintegration capability |

| Structure | 1. Stiff polymer 2. Stiff fibers 3. Continuous fibers 4. Long fibers 5. Interfacial bonding |

1. A rigid chain 2. A high crystallinity 3. Oriented crystals 4. Stiff fibers/fillers 5. Dissolvable coating |

1. Water soluble molecules 2. Polymer chain containing hydrolysable linkages 3. Hydrophilic chains 4. Structural units sensitive to temperature 5. Non-dissolvable particles in dissolvable matrix |

|

| Kuralon | PET | Nylon 6 | Aramid | Vectran | |||

| Type | 1239 | 5501 | 5516-1 | Regular | HT | ||

| Thickness (dtex) | 1330 | 20000 | 2000 | 1110 | 930 | 1670 | 1670 |

| Number of filaments | 200 | 1000 | 1000 | 250 | 96 | 1000 | 300 |

| Tensile strength (cN/dtex) | 8.2 | 9.8 | 11.9 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 19.4 | 22.9 |

| Elongation at break (%) | 7.7 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 10.7 | 19.4 | 3.9 | 3.8 |

| Young’s modulus (cN/dtex) | 177 | 203 | 260 | 110 | 34 | 493 | 530 |

| Dry heat shrinkage (%) | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 11.2 | 6.5 | ||

| Boiling shrinkage (%) | 4.5 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 5.4 | 11.8 | ||

| Specific gravity | 1.30 | 1.38 | 1.14 | 1.41 | 1.44 | ||

| Moisture regain (%) | 5.0 | 0.4 | 4.5 | 7.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Test method | Unit | Measured value | |

| Tensile modulus | ISO 2062 | GPa | 29 |

| Tensile strength | GPa | 1.1 | |

| Tensile elongation | % | 20 | |

| Single-end breaking force | GPa | 1.1 | |

| Single-end breaking elongation | % | 14 |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).