1. Introduction

Oil remains an essential energy resource for meeting global needs. Oil recovery occurs in three stages: primary, secondary, and Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) [

1]. Among EOR techniques, modified water injection, particularly water flooding, has gained increasing interest due to its relatively low cost and environmental benefits [

2,

3,

4]. Adding polymers to the injected water increases its viscosity, thereby improving the sweep efficiency of reservoirs and enhancing oil recovery [

5,

6,

7].

Their mobility primarily influences the transport of polymers in porous systems [

8,

9], defined as the ratio between the polymer's viscosity and pore permeability [

10,

11,

12]. This mobility depends on the balance between viscous forces, which facilitate polymer displacement, and capillary forces [

13,

14,

15], which can slow or block their passage through the pores. A low-mobility polymer moves slowly but can penetrate smaller pores more effectively, optimising oil recovery. Conversely, excessive mobility may lead to preferential flow, leaving certain reservoir zones unswept by the injected fluid [

1].

Various parameters influence polymer performance in porous systems. Pore size and geometry determine whether polymers can flow freely or accumulate in restricted areas. Temperature plays a key role: at high temperatures, some polymers degrade, reducing their efficiency [

16,

17]. Additionally, flow velocity impacts the formation of viscoelastic structures, which are essential for maximising oil recovery.

However, polymer efficiency is often diminished by retention mechanisms [

18,

19,

20], such as mechanical trapping [

21], adsorption [

22], and hydrodynamic retention [

23]. Mechanical trapping occurs when polymers are blocked in narrow pores, while adsorption on rock surfaces decreases their active concentration for displacing oil. Hydrodynamic retention refers to the fraction of polymers trapped in the porous medium due to fluid interactions, reducing their effectiveness [

24].

Previous research on using HPAM and other polymers in core flooding tests has demonstrated their potential in EOR applications while highlighting significant limitations, notably reduced effectiveness under high salinity conditions [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Studies have shown that HPAM's viscosity and performance deteriorate in high salt concentrations, leading to less efficient oil recovery.

In response to these challenges, other biopolymers, such as Xanthan [

29,

30] and Guar Gum [

31,

32], have been explored in various contexts for EOR applications. However, these polymers face similar degradation issues under saline conditions and concerns regarding high costs. Research conducted in countries such as Saudi Arabia [

33], Brazil [

34], Pakistan [

35], Egypt [

36], Sudan [

37], and Colombia [

38] has consistently pointed out these constraiPalatino Linotypents, indicating that while these biopolymers offer environmental advantages, their effectiveness in harsh reservoir environments remains limited.

Despite using various EOR techniques, much oil remains trapped in geological formations. Partially hydrolysed polyacrylamide is commonly used to improve the viscosity of injected water and thus increase sweep efficiency. However, its performance is limited in environments with high salinity and temperature [

39]. Studies conducted by Zhang [

40] and Bo Wang [

41] have highlighted a phenomenon of plugging caused by HPAM, where reservoir pores become clogged, reducing permeability and limiting recovery efficiency. These findings underscore the limitations of current methods, which struggle to maximise oil production under varying reservoir conditions [

42,

43].

Faced with these challenges, natural biopolymers, such as Opuntia ficus-Indica mucilage, present a promising alternative. Their natural origin and biodegradability make them ideal candidates for industrial applications, particularly in EOR [

44,

45]. While this study is among the first to explore and apply this biopolymer in the context of EOR in Algerian reservoirs, further research is required to assess its scalability and long-term effectiveness. These initial findings open new avenues for integrating local and renewable resources into the oil industry. However, additional studies are essential to fully understand such materials' practical implications and potential in real-field conditions.

The cladode of

Opuntia ficus-indica is used in various fields, including food [

46] and cosmetics [

47], due to its richness in Mucilage and polysaccharides [

48]. Regarding rheological behavior, the Mucilage from Opuntia exhibits interesting properties that make it comparable to other natural polymers like Guar Gum [

49] and Xanthan [

50]. While these polymers are also used to enhance the viscosity of solutions, Opuntia's Mucilage stands out for its better performance in saline environments and ability to maintain optimal viscoelastic properties, making it a promising alternative in industrial applications.

In our comparative study of the performance of HPAM, Opuntia mucilage, and their blend, we demonstrated that biopolymers can improve recovery efficiency under high salinity conditions while reducing costs and environmental impact. Furthermore, our approach aligns with an eco-responsible vision by promoting the use of local renewable resources to meet industry needs [

51].

This article evaluates the relevance of Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage as an alternative to HPAM in enhanced oil recovery techniques. Through a comparative study of these polymers' physicochemical and rheological properties and structural analyses of core plugs, we aim to determine if their synergy can offer optimal performance in challenging reservoir conditions. This approach seeks to improve the efficiency of current methods and promotes the use of natural and local resources in a sector seeking sustainable innovation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Opuntia ficus-indica Powder and Fluid Preparation

2.1.1. Isolation and Extraction Powder of the Opuntia ficus-indica

For the experimental tests, the synthetic HPAM polymer (Flopaam 3130S, Mw: 3.5 x 106 g/mol, 30% hydrolysis degree) generously provided by SNF Floerger France was selected as the benchmark polymer.

The fine powder derived from the cladodes of

Opuntia ficus-indica was harvested in the Tizi Ouzou (Algiers, Algeria) in January 2024. The extraction process involved meticulous steps: i1) Before extraction, the cladodes were rinsed with water to remove any dust particles; i2) The spines were carefully cut off with a knife, and the cladodes were peeled and chopped into pieces measuring 1-2 cm; i3) These pieces were then frozen for 24 hours; i4) After freezing, three volumes of the cladodes were combined with one volume of distilled water at 40°C;i5) The resulting mixture was homogenised at room temperature; i6) It was then passed through a fine-mesh sieve to eliminate more extensive insoluble materials, followed by filtration through sterile cloth to recover the Mucilage; i7) To precipitate the Mucilage from the filtrate, three volumes of 96% ethanol were added while stirring at 350 rpm for one hour; i8) The Mucilage was collected by filtration, dried in an oven at 60°C for 24 hours, and finally ground into a fine powder using a mortar [

51].

2.1.2. Crude Oil and Brine

In this study, we simulated the salinity of an Algerian petroleum reservoir by preparing a saline solution containing 20 g/L of sodium chloride (NaCl) dissolved in deionised water (DW). We selected NaCl for our simulated formation water to maintain a straightforward and controlled experimental approach. Using a common salt such as NaCl, we aimed to create a precise baseline for our research, enabling us to isolate the effects of particles and polymers. While we recognise the limitations of this simplified method, it serves as a crucial preliminary step in examining fundamental interactions before tackling the more complex ionic compositions typically found in actual reservoir conditions. The crude oil utilised in this study was obtained from an Algerian oil field, exhibiting a density of 0.8401 g/cm³, a viscosity of 6.0453 cP, and an API gravity of 36.93.

2.1.3. Fluid Preparation

This study investigated a concentration of 10,000 ppm using a synthetic brine with a composition of 2% NaCl for both HPAM and Opuntia ficus-indica polymers. The HPAM solutions were meticulously prepared by dissolving the appropriate quantity of powder in water under low-speed magnetic stirring (90 rpm) for 6 to 7 hours, resulting in homogeneous and transparent dispersions devoid of insoluble particles.

Opuntia ficus-indica solutions were carefully prepared by mixing the suitable powders in synthetic brine and agitating for 10 hours at room temperature (20 ± 2 °C). HPAM and Opuntia ficus-indica solutions were securely stored in sealed containers and left undisturbed for 12 hours to ensure complete hydration and prevent oxidation.

A synergistic blend of HPAM and Opuntia ficus-indica was also prepared with proportions of 80% HPAM and 20% Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage while maintaining a total concentration of 10,000 ppm. This blend was formulated by dissolving both components in the synthetic brine. After uniform agitation for 10 hours at room temperature (20 ± 2 °C), it was left to rest for 12 hours in sealed containers to allow optimal interaction between the two polymers, thus ensuring maximum homogeneity and stability.

2.1.4. Core Samples

Three identical plugs of Triassic clay-type rock were extracted from petroleum cores in the Hassi Messaoud reservoir, Algeria. Each plug had the following dimensions: a diameter of 2.45 cm, a length of 4.24 cm, and a mass of 47.16 g. The plugs exhibited a known porosity of 16.52% and a permeability of 206 md, making them suitable for simulating the petrophysical conditions encountered in this reservoir. This selection ensures that the experimental results accurately represent the fluid behavior in the targeted reservoir.

2.2. Physico-Chemical Analyses

2.2.1. Thermal Analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted for Opuntia ficus-indica and HPAM powder using a TA instrument (SDT Q600 V20.9 Build 20, New Castle, DE, USA). Argon was used as the purge gas at a 100 mL/min flow rate. A dried powder sample of Opuntia ficus-indica and HPAM was placed in an aluminum vessel and heated from 25 to 1000 °C at 10 °C/min.

2.2.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis (XRD)

For XRD analysis, HPAM and Opuntia ficus-indica powders were loaded into aluminum sample holders and analysed using a Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer operating at 40 kV and 30 mA. The diffractometer utilised Cu-Kα radiation with a wavelength (λ) of 1.5406 Å. The analysis was also conducted on the core plugs before and after injection of the polymer solutions to assess any changes in crystallographic structure.

2.2.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

Fourier-transform infrared spectrometry (Bruker Lances, TENSOR 27) was employed to measure the FTIR spectra of HPAM, Opuntia ficus-indicas powder, and the mixed. The frequency range used was from 400 to 4000 cm-1.

2.2.4. Rheological Measurements

Rheological properties were evaluated using a temperature-controlled rheometer with Peltier temperature control (Physica MCR302, Anton Paar). The measurement system had a cone-plate geometry (Φ60 mm, Ө = 1°, CP60/1). Tests were conducted on HPAM and Opuntia ficus-indica powder mixed at 80 °C using a synthetic brine solution with 2% NaCl.

2.2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis EDX

The microscopic structure of Opuntia ficus- indica powder, HPAM, and the plug samples sourced from petroleum cores (before and after injection into core flooding) were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with a CARL ZEISS EVO LS 10 from Germany. An energy-dispersive X-ray detector (EDX) was used for additional analysis to determine the elemental composition of both the powders and the core plugs, providing insights into the material interactions before and after polymer solution injection.

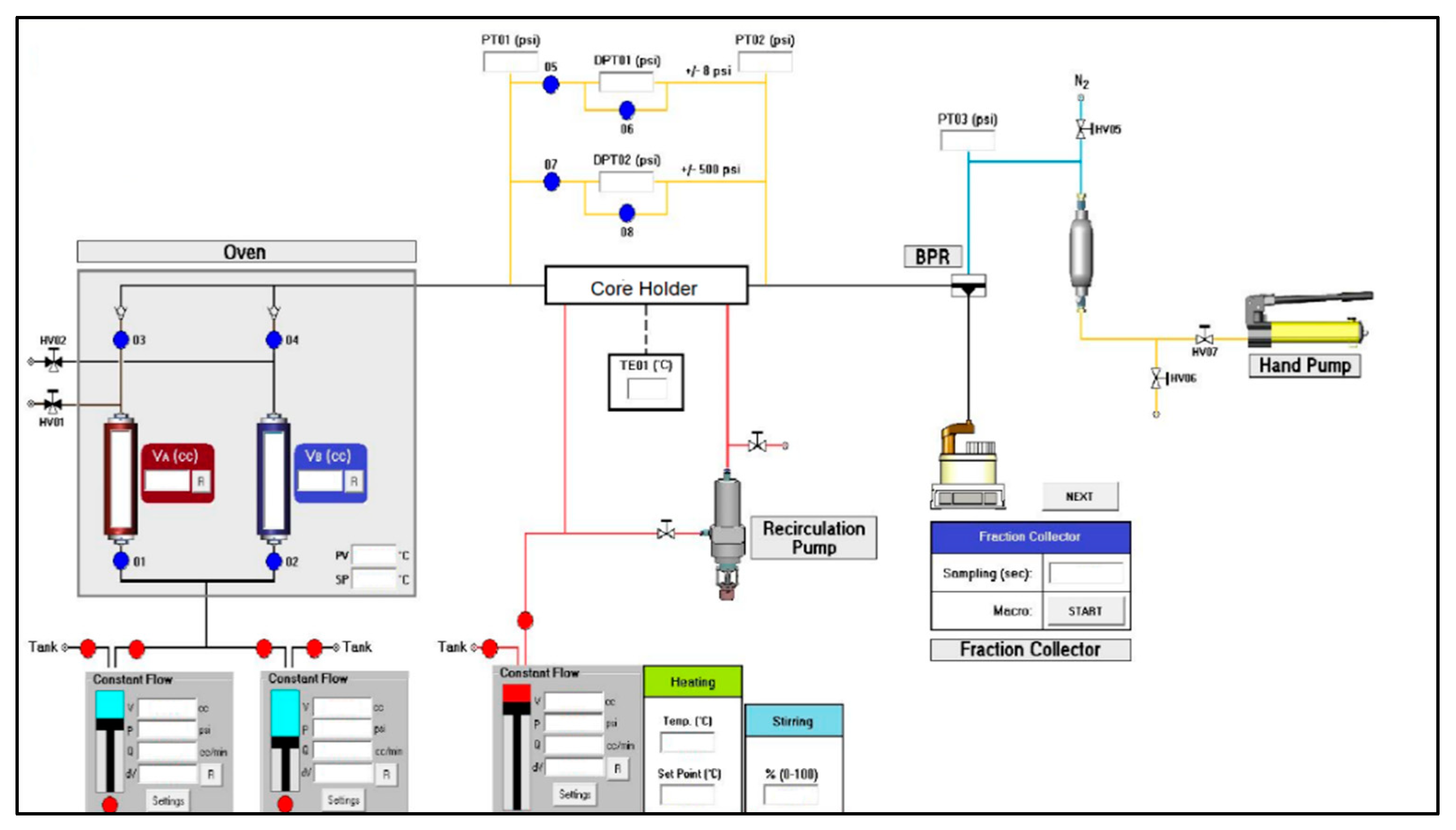

2.2.6. Assessment of Polymer Efficiency in Core Flooding Analysis for Enhanced Flood Resistance

The experimental procedure for core flooding followed rigorous steps to ensure precise and reproducible results. Triassic clay-sandstone core plugs were prepared and inserted into the core flooding apparatus. Saturation of the medium was achieved by injecting a 20 g/L NaCl solution throughout 3 to 6 hours. Subsequently, the injection system was set up with two BT series syringe pumps, allowing fluid injection at up to 5,000 psi pressures. The thermostat-controlled oven maintained a temperature of 120 °C, corresponding to the specific reservoir under study. This temperature was chosen to simulate the reservoir's actual conditions, as the target reservoir's temperature is around 120°C. The core was saturated with the test fluid using a back-pressure regulator (BPR), increasing the interstitial pressure to fill all fluid pores.

Each experiment was conducted twice, once with HPAM, once with Opuntia ficus-indica biopolymer, and once with a mixture of both, directly comparing their efficacy in enhanced oil recovery processes. Crude oil was injected at various rates (0.5, 1, and 1.5 mL/min) during the experiments. In contrast, polymer solutions at a concentration of 10,000 ppm (for both HPAM and Mucilage, as well as the mixed solution) were injected at corresponding rates. The pressure sensor system continuously monitored the pressure difference during flow, providing essential data for evaluating polymer displacement efficiency under reservoir conditions.

This rigorous methodological approach facilitated a comprehensive assessment of polymer performance in a realistic context of enhanced oil recovery. The study utilised Algerian reservoir core plugs, characterised by a permeability of 206 mD and a porosity of 16.52%, which was crucial for reproducing the conditions of Algerian petroleum reservoirs.

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the displacement device.

2.2.7. Statistical Analysis

All measurements were performed in triplicate, and the results were mean ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermal Analysis

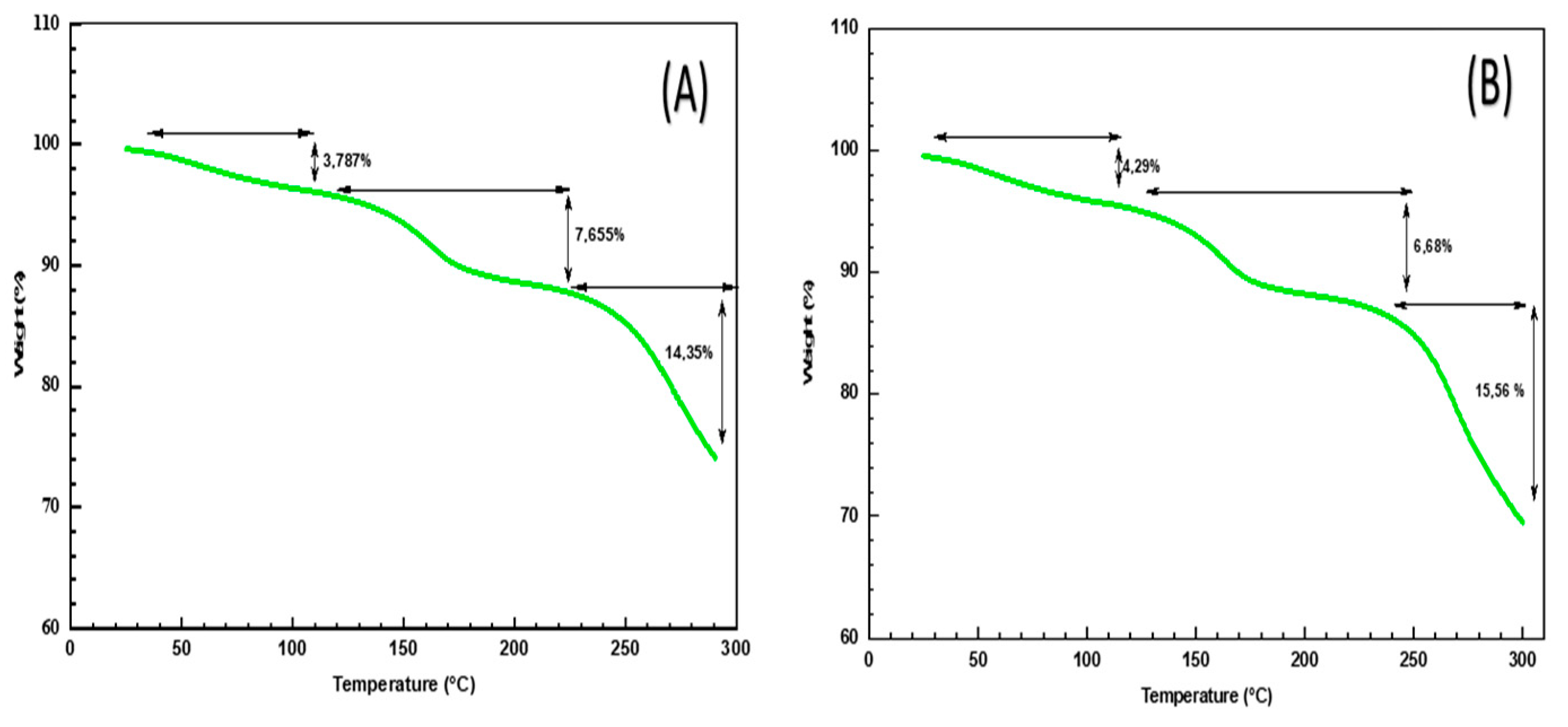

Figure 2 illustrates the thermal behavior of the Mucilage extracted from

Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes and HPAM. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) reveals distinct zones of weight loss at different temperatures, providing insights into the thermal decomposition of the components present in these polymers.

As shown in

Figure 2A, three major thermal events are identified during the characterisation of the Mucilage. First, a weight loss of 3.787% is observed at 100 °C, attributed to the endothermic evaporation of absorbed water or moisture in the polymer [

52,

53]. While this loss is measurable, it is considered negligible, especially given the well temperatures in Algeria, which typically reach around 100 °C. This underscores the potential of the Mucilage in enhanced oil recovery (EOR) applications.

The second phenomenon, characterised by a weight loss of 7.695% at 200 °C, corresponds to the decomposition of organic components. This thermal behavior aligns with previous studies by Otálora et al. [

54] and Manhivi et al. [

55], who reported similar behaviors in various biopolymers.

Finally, the last thermal event occurs at 300 °C, resulting in a weight loss of 14.35%, indicating significant thermal degradation. This degradation may be related to the breakdown of components, such as chain breaks in polysaccharides and the decomposition of pectins [

56].

In comparison, in

Figure 2B, HPAM, commonly used in EOR applications, exhibits similar thermal events. At 100 °C, a weight loss of 4.29% is observed, followed by a loss of 6.68% at 200 °C due to the decomposition of organic components and a notable thermal degradation of 15.56% at 300 °C [

57,

58]. Although the two polymers differ in chemical structures, their thermal behaviors are remarkably equivalent within the examined temperature range.

These findings suggest important implications for their combined use in enhanced oil recovery applications. The Mucilage from Opuntia ficus-indica behaves similarly to HPAM, indicating that this biopolymer could be a promising alternative in EOR processes.

3.2. SEM and EDX Analysis

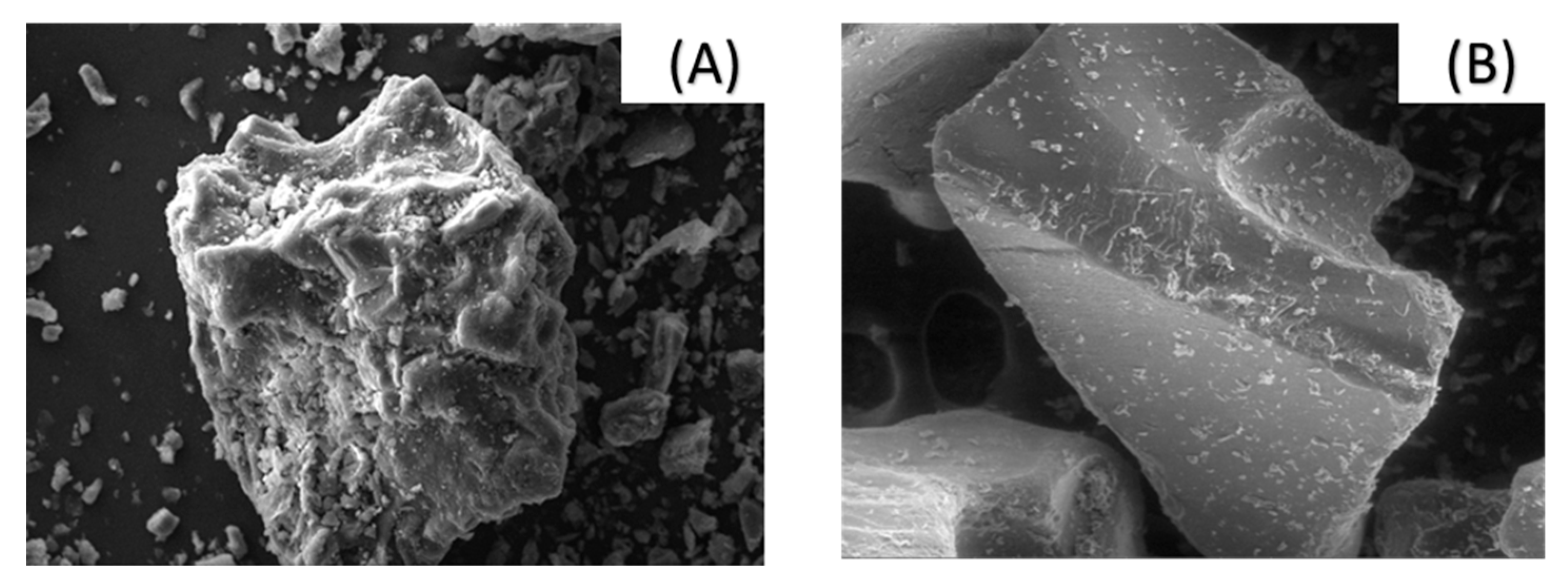

Combined scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analyses were conducted to study the morphology, geometric structure, distribution, and purity of the mucilage powder samples derived from Cladode Opuntia ficus-indica and partially hydrolysed polyacrylamide.

The results presented in

Figure 3A. indicate that the mucilage particles exhibit a crystalline and irregular morphology, suggesting that the particles do not have an elongated shape. The surfaces of the particles display a marbled appearance, enhanced by wavy fibers, while their particle size distribution reveals heterogeneity. In contrast, HPAM, as shown in

Figure 3B presents a uniform and smooth morphology characteristic of synthetic polymers. This morphological uniformity promotes a more even distribution of particles in solution, leading to more predictable interactions with other enhanced oil recovery (EOR) system components. Previous studies have reported similar findings regarding the morphology of synthetic polymers, highlighting the significance of this characteristic for industrial applications [

59].

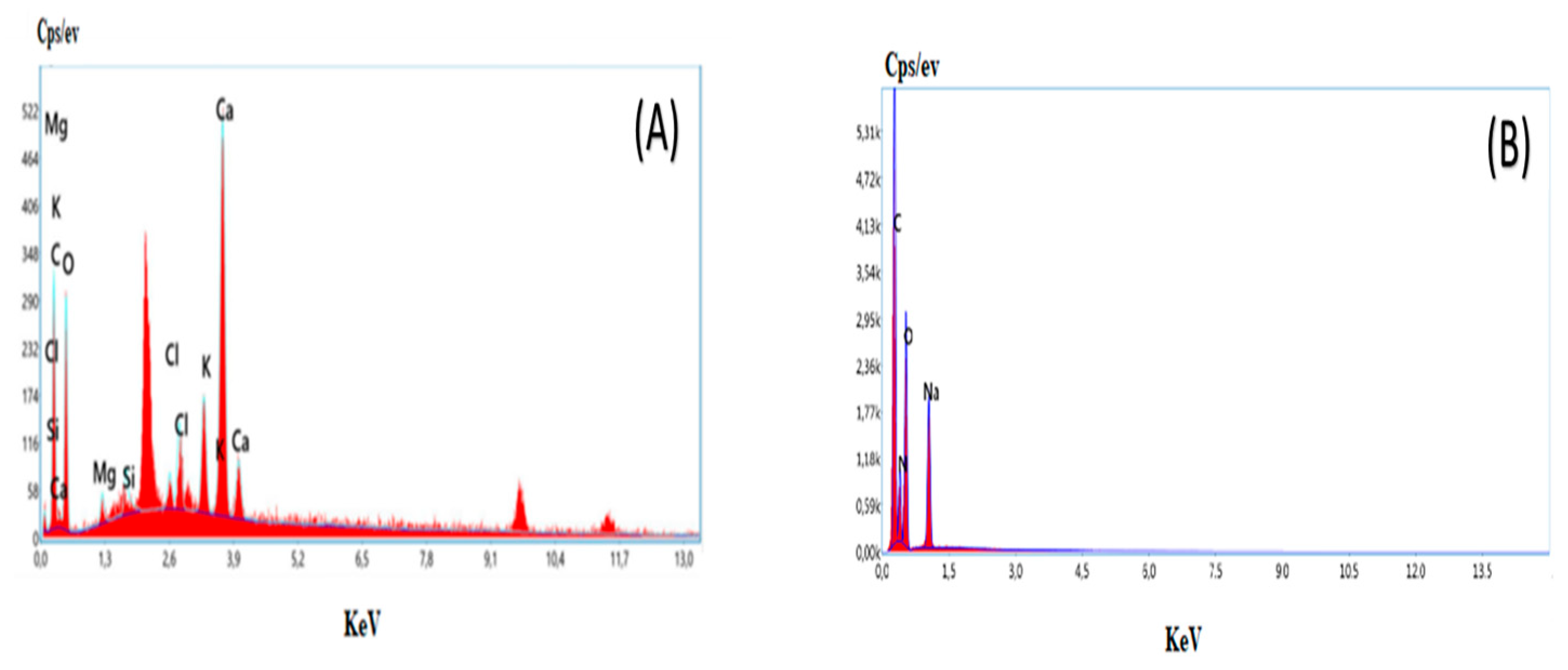

Figure 4 illustrate the EDX analysis of the chemical elements present on the surface of the particles. The results for Cladode

Opuntia ficus-indica, presented in Figure4.A, reveal the presence of silicon, carbon, potassium, chlorine, magnesium, calcium, and oxygen. These identified mineral elements are consistent with those reported in the literature, underscoring the importance of the chemical composition of plant extracts in industrial applications [

60]. In contrast, for HPAM, Figure4.B indicates the presence of carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and sodium, characteristic elements of this synthetic polymer. The predominance of these elements reflects the chemical structure of HPAM [

61], which may influence its viscoelastic properties and performance in enhanced oil recovery applications, as demonstrated by other research.

The SEM/EDX analyses reveal significant distinctions morphologically and chemically between the Mucilage from Opuntia ficus-indica and HPAM. These differences may lead to interesting synergistic interactions in enhanced oil recovery applications. With its complex structure, the Mucilage offers promising potential for improving interaction with porous surfaces, while HPAM provides the necessary stability to its viscoelastic properties. This synergy between the two polymers could optimize the efficiency of enhanced oil recovery processes, as suggested by several previous studies.

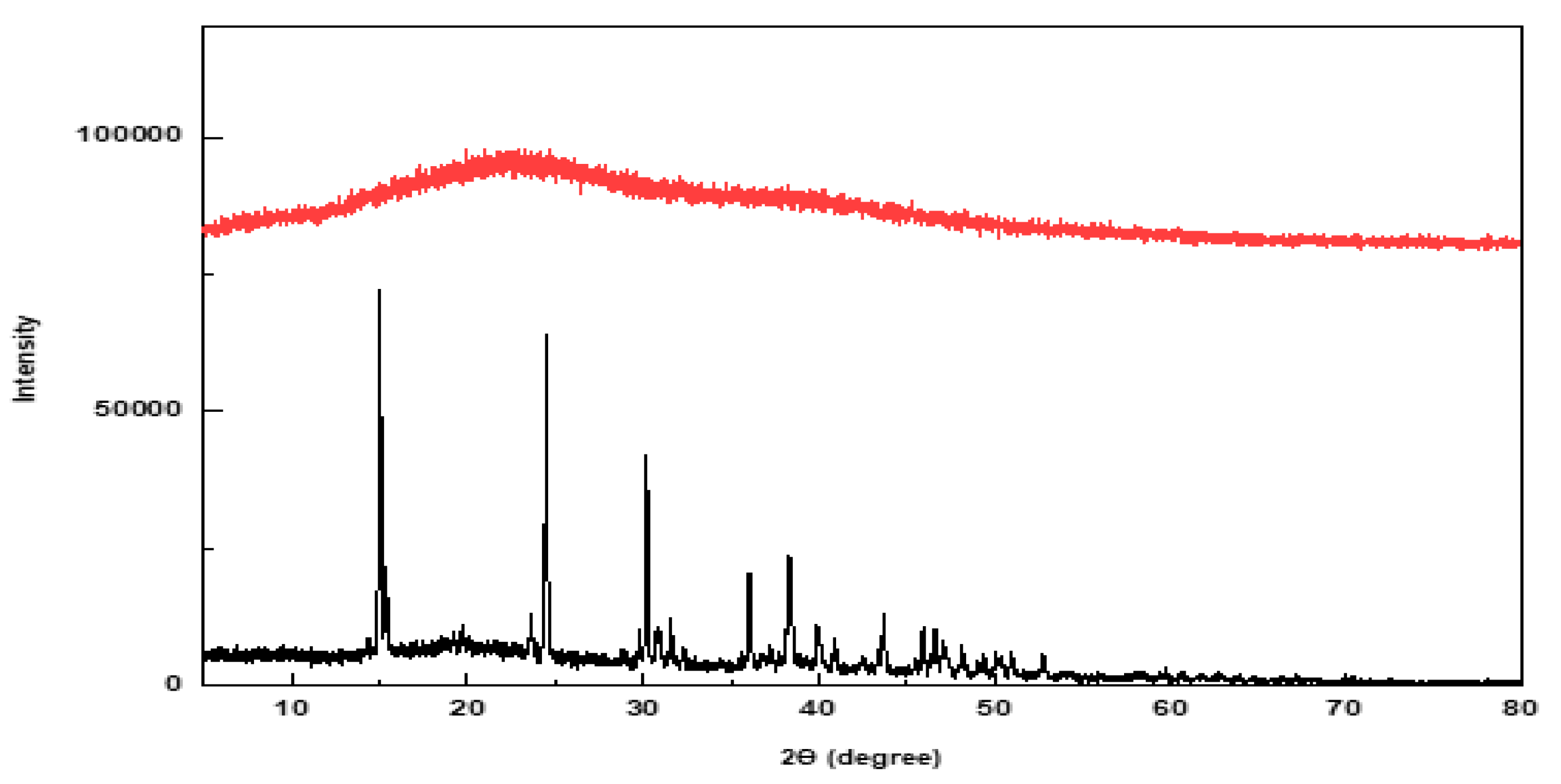

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis (XRD)

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis explored the structural differences between the Mucilage extracted from

Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes and partially amorphous polyacrylamide. The analysis results, illustrated in Figure5., indicate that the Mucilage exhibits a crystalline structure with diffraction peaks at 15°, 25°, 32°, 38 and 43°, corresponding to minerals such as calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), calcium magnesium bicarbonate (CaMg(CO₃)₂), magnesium oxide (MgO), potassium chloride (KCl), and silicon dioxide (SiO₂) in quartz form. These findings corroborate previous studies that highlighted the presence of these minerals in

Opuntia ficus-indica extracts, emphasising the influence of various environmental factors on their composition [

62,

63].

In contrast, the analysis of HPAM, presented in Figure5, reveals no distinct diffraction peaks characteristic of amorphous materials. This absence of regular diffraction indicates a disordered arrangement of polymer chains, as demonstrated in numerous studies [

64,

65]. The structural differences observed between the crystalline Mucilage and amorphous HPAM may significantly affect their performances in enhanced oil recovery applications. While the Mucilage, with its mineral composition, may provide stability or reactivity properties, HPAM may exhibit different interactions and behavior depending on the operational conditions.

These results underscore the importance of analysing the mineral and structural composition of materials used in enhanced oil recovery processes, as these characteristics can directly influence the effectiveness of recovery methods.

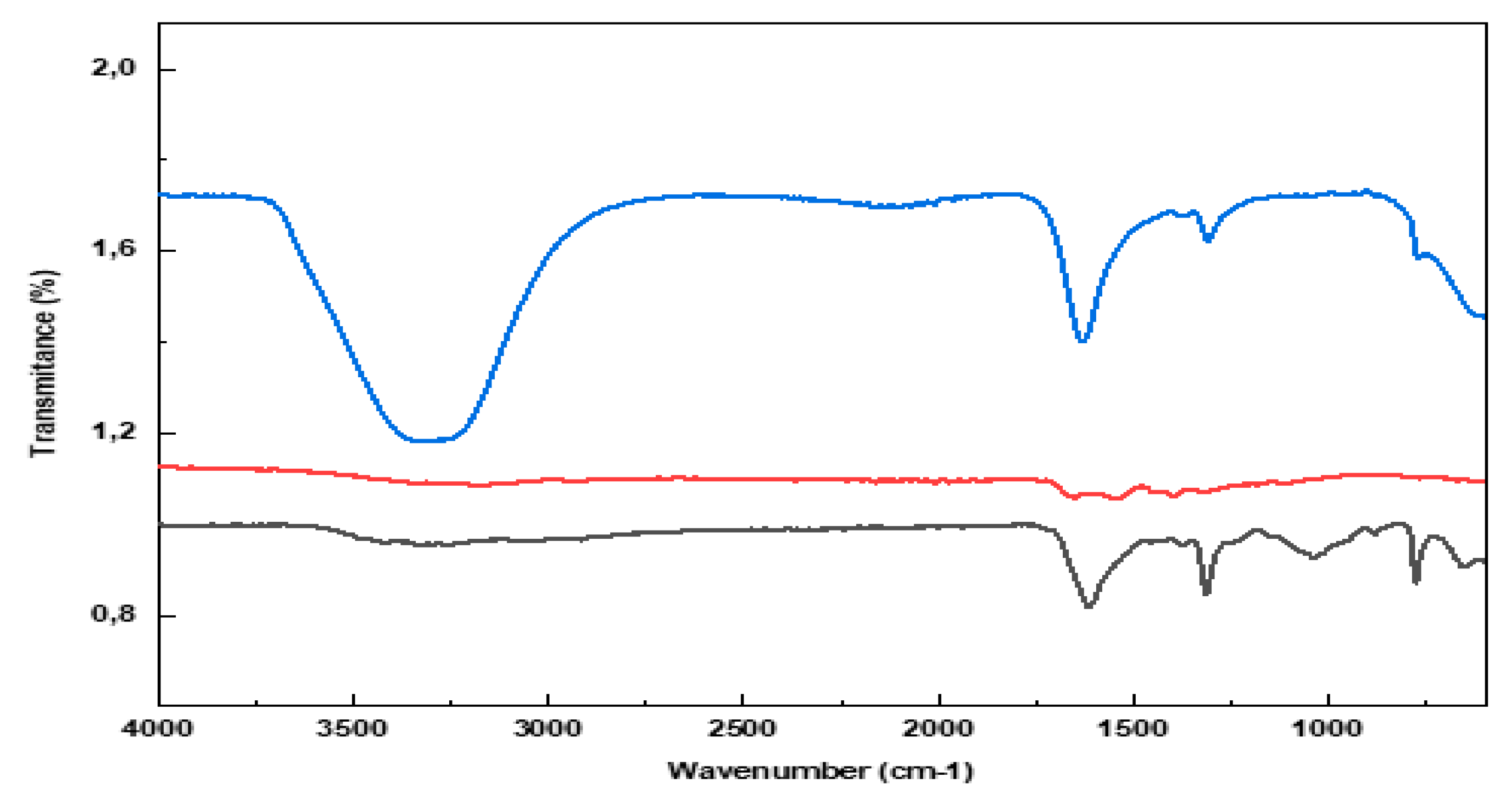

3.4. FTIR Analysis

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed to investigate and compare the molecular characteristics of hydrophilic polyacrylamide, the extract of Opuntia ficus-indica powder, and the mixture. FTIR spectra were obtained for each sample to identify the present functional groups and analyse their chemical structures.

In

Figure 6, the FTIR analysis of HPAM displays distinctive features. Notably, prominent peaks are observed at specific wavenumbers: 3182 cm⁻¹ signifies elongation vibrations attributed to N-H bonds, while 2937 cm⁻¹ and 1651 cm⁻¹ represent C-H deformation and vibration, respectively, associated with C=O functional groups. Discernible peaks ranging from 1317 to 1110 cm⁻¹ indicate C-O stretching vibrations [

64,

65].

In the spectrum of

Opuntia ficus-indica powder, the absorption band at 3255 cm⁻¹ indicates the presence of hydroxyl functional groups (-OH). Firm peaks observed at approximately 1615 cm⁻¹ and around 1314 cm⁻¹ are associated with carbonyl (C=O) and ether (C-O) functional groups' elongation and deformation vibrations. The bands identified between 1040 and 778 cm⁻¹ are attributed to the stretching vibrations of the Si-O-Si group [

66].

For the HPAM/mucilage mixture, a broad and intense band is observed between 3000 and 3500 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the elongation vibrations associated with N-H and O-H bonds. This indicates the formation of hydrogen bonds between the HPAM and mucilage groups. The peaks at 1631 cm⁻¹, 1379 cm⁻¹, and 773 cm⁻¹ are associated with the stretching and bending vibrations of -OH, C-C, C-O, and Si-O-Si groups [

67,

68].

The FTIR analysis of the individual polymers and their combination reveals how the unique chemical properties of each integrate into the mixture, thereby providing insight into their interactions and potential for use in specific applications.

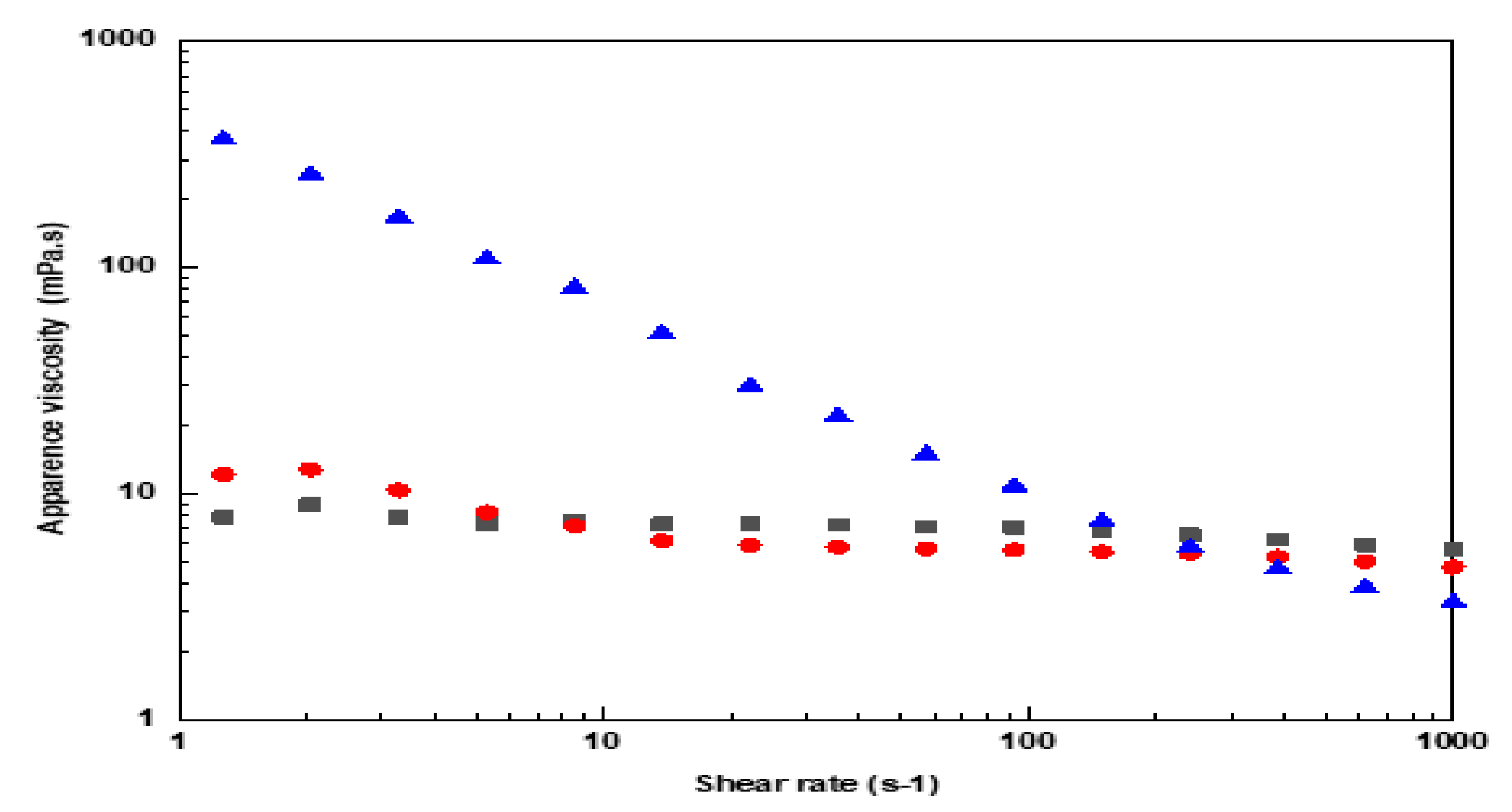

3.5. Rheological Measurements

The analysis of apparent viscosity as a function of shear rate was conducted for a 2% NaCl brine at 80 °C (

Figure 7), representing the typical salinity conditions of the Hassi Messaoud reservoirs. For concentrations of 1% of HPAM and mucilage solutions, both exhibited a quasi-Newtonian behavior with a viscosity of about 10 mPa·s. This behavior is consistent with other studies that have reported similar viscosities for HPAM solutions under comparable salinity conditions, highlighting the stability of low-concentration solutions [

69,

70].

However, the analysis of the mixture containing 80% HPAM and 20% Mucilage at a total concentration of 10,000 ppm revealed a significant increase in viscosity, reaching approximately 1,000 mPa·s. This observation aligns with previous research indicating that adding Mucilage or other biopolymers to HPAM solutions can significantly enhance viscosity due to synergistic interactions. For example, studies have shown that incorporating silica into polymer systems can increase viscosity by strengthening the polymer network structure. Adding silica contributes to enhanced intermolecular interactions, resulting in higher viscosity, which is crucial for enhanced oil recovery applications.

Results from earlier works indicate that adding silica in HPAM and mucilage blends can improve viscosity and increase solutions' stability in saline environments [

71,

72]. For instance, one study demonstrated that incorporating silica into polymer systems increased reactivity and resistance to salinity effects, thus allowing better performance under reservoir conditions. These findings highlight the importance of synergies between components, where Mucilage and silica could interact to offer even higher viscosity and optimised rheological characteristics.

This increase in viscosity is particularly relevant for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) applications. In the Hassi Messaoud reservoir context, higher viscosity can help reduce gravitational segregation and improve the mobility of the displacement fluid. Previous studies have also shown that more viscous fluids can better mobilise trapped oil in the pores, thereby increasing recovery efficiency.

In summary, the rheological results underscore the promising potential of the HPAM/mucilage mixture, especially when combined with additives such as silica in saline environments. These systems exhibit superior viscosity and flow characteristics compared to individual solutions. This research contributes to understanding the rheology of polymer systems under specific reservoir conditions and opens avenues for optimising oil recovery processes.

3.6. Core Flooding Analysis: Comparative Evaluation of HPAM, Opuntia ficus-indica, and mixes for EOR

This section presents the results of the analyses conducted during the core flooding experiments, including the relationship between pressure drop and flow rate for different polymer solutions. We will also discuss the fluid displacement curves, the SEM and EDX analyses of the plugs before and after injection, and the results of the XRD analysis.

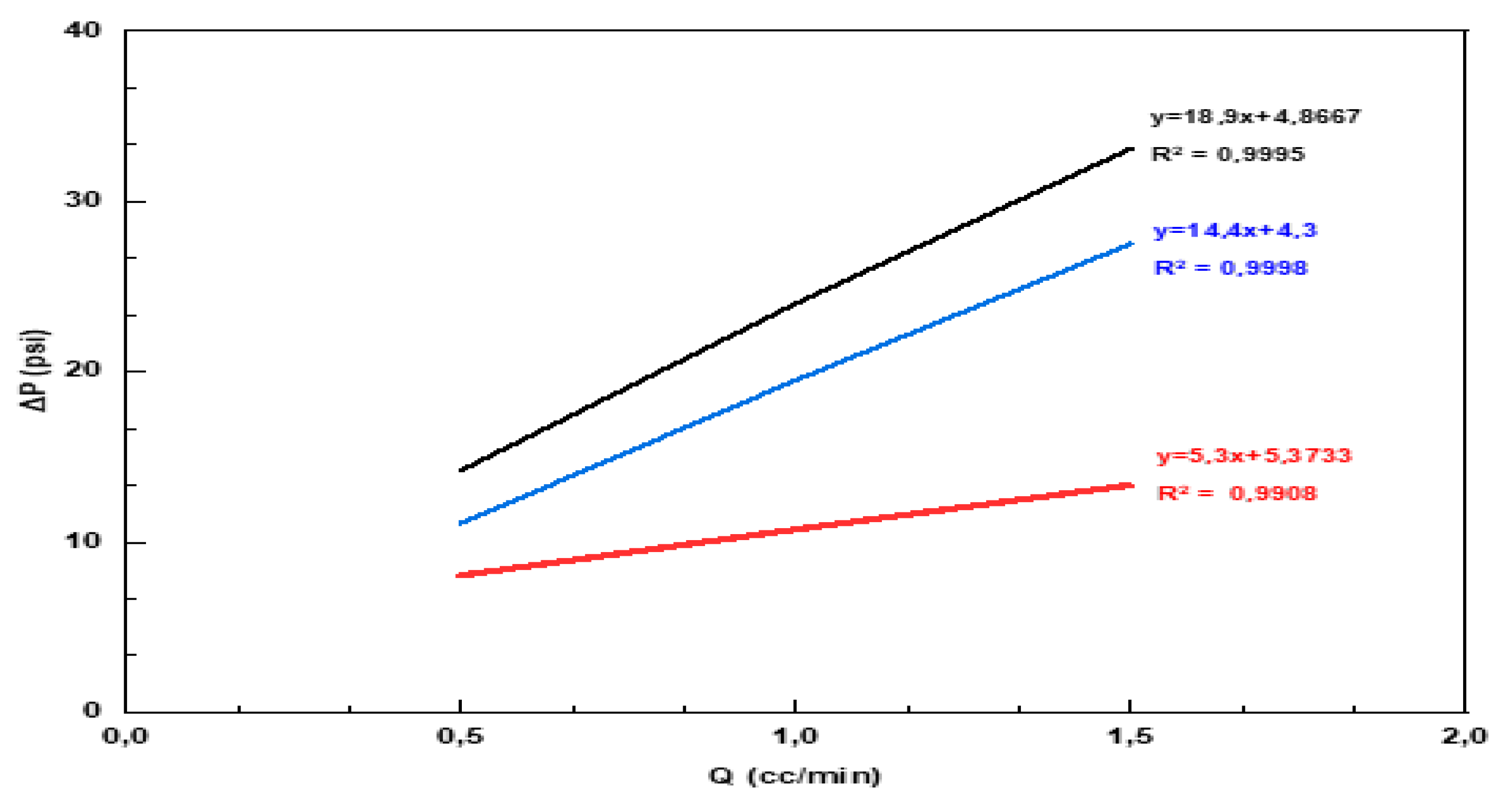

3.6.1. Analysis of the Relationship Between Pressure Drop and Volumetric Flow Rate for Different Polymer Solutions in Core Flooding:

Studying the relationship between pressure drop (ΔP) and volumetric flow rate (Q) is critical for understanding polymer solutions' performance in core flooding experiments. These results provide an in-depth evaluation of the impact of each formulation on flow resistance, offering valuable insights into their behavior under simulated reservoir conditions. Specifically,

Figure 8 presents the ΔP versus Q curves for three types of solutions: HPAM,

Opuntia ficus-indica cladode mucilage, and their blend. This data establishes a solid foundation for comparing the effectiveness of these formulations in enhanced oil recovery (EOR) processes, highlighting their potential to improve hydrocarbon displacement.

The core flooding tests (

Figure 8) revealed distinct performance differences among three polymeric solutions: HPAM,

Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage, and their blend. The HPAM solution exhibited the highest flow resistance with a slope of 18.9, which is consistent with findings from studies showing that high-viscosity HPAM can cause pore-blocking and lead to rapid pressure buildup, as reported by R. S. Seright et al. [

73] and Guoyin Zhang [

74]. This high resistance suggests that while HPAM can improve sweep efficiency, it may also reduce oil recovery due to increased formation damage.

In contrast, the

Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage demonstrated a lower slope of 5.35, indicating reduced flow resistance. This agrees with recent research by Jae-Eun Ryou [

75] and Hua Li [

76], who found that natural polymers like Mucilage provide smoother flow through porous media due to their biocompatible structure. The lower pressure drop observed could enhance oil recovery by allowing more effortless movement through reservoir formations.

The HPAM/mucilage blend, with an intermediate slope of 14.4, strikes a balance between high mobility and low resistance, mitigating the risk of pore-clogging seen with pure HPAM. Similar results were documented in a study by Yan Liang [

77], who demonstrated that blending HPAM with natural polymers like xanthan gum can reduce viscosity-related clogging while maintaining enhanced recovery performance.

These results emphasise the importance of tailoring polymer formulations to manage viscosity and minimise formation damage in EOR processes. Integrating Mucilage into HPAM formulations offers a promising solution, allowing for adjustable viscosities and reduced pressure drops. This could optimise EOR applications in saline reservoirs such as Hassi Messaoud, where conditions require robust and adaptable solutions.

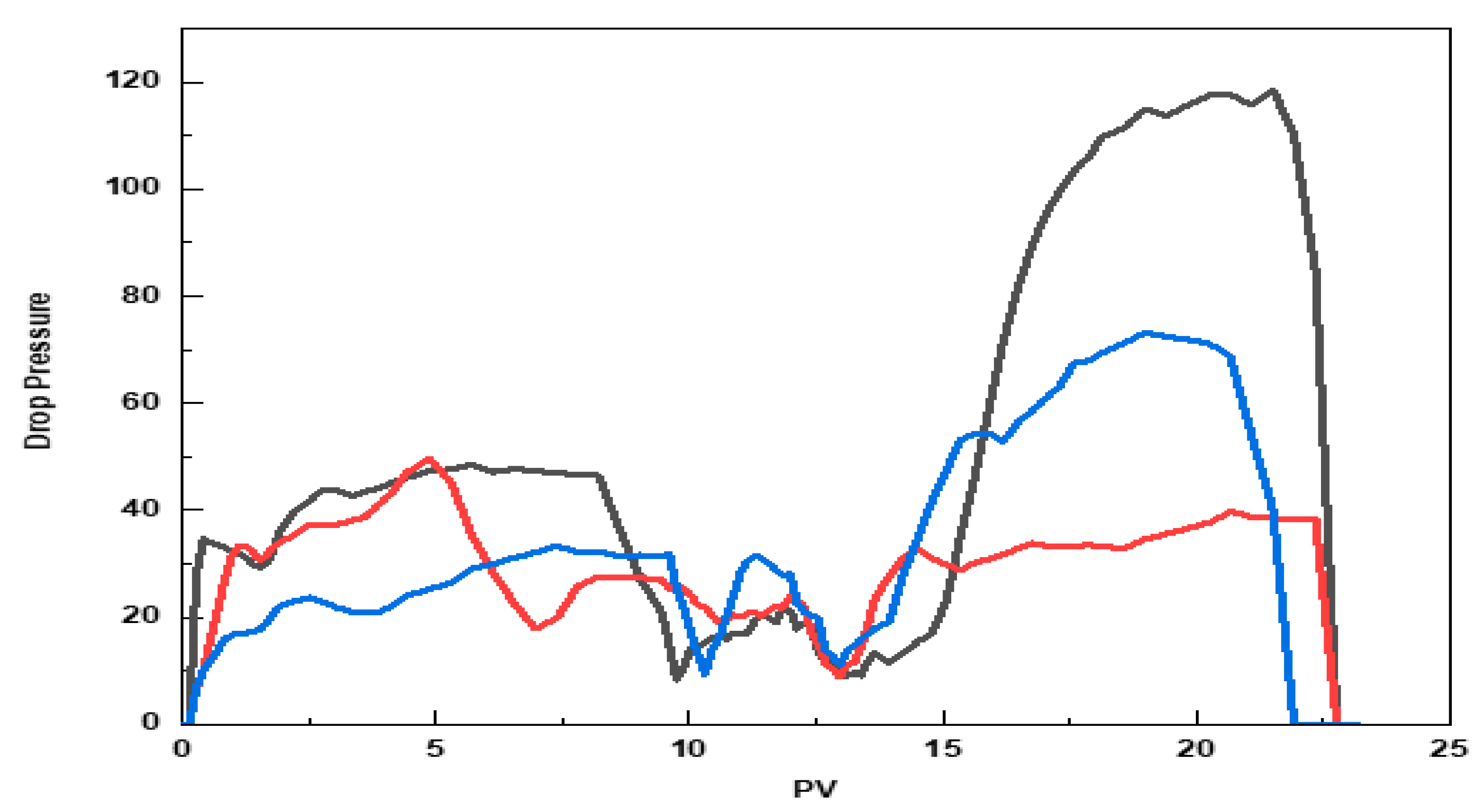

3.6.2. Analysis of Fluid Displacement Curves in Core Flooding

Figure 9 illustrates the relationship between differential pressure (ΔP) and injected pore volume (PV) for three polymeric solutions tested: HPAM,

Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage, and their blend. This analysis provides valuable insights into the fluid dynamics within reservoir cores, shedding light on the mobility and efficiency of fluids under conditions representative of real oil reservoirs. Polymer injection in EOR processes often leads to increased differential pressure. This pressure is a key indicator of flow resistance and fluid mobility through the porous medium. Previous studies, such as those by Fuwei Yu [

78], have shown that high-pressure drops associated with increased viscosity can hinder oil recovery due to pore blockage, a phenomenon observed with pure HPAM in our tests.

Our results show distinct differences among the tested solutions: the HPAM solution exhibited a high ΔP, increasing from 0 to 120 and stabilising at a PV of 22.76, indicating significant flow resistance and potential blockage, which can impede oil recovery by slowing the advancement of the displacement front. In contrast, the

Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage solution showed a much lower ΔP, ranging from 0 to 40, stabilising at a PV of 23.1848, suggesting better fluid mobility and a more remarkable ability to recover hydrocarbons trapped in delicate pores. The HPAM/mucilage blend displayed an intermediate ΔP, reaching 80 at a PV of 21.92, offering a balanced compromise between flow resistance and fluid mobility, making it an efficient solution for enhanced oil recovery, as suggested by Laura M. Corredor [

79] in their research on polymer formulations for high-salinity reservoir environments.

These findings confirm that adding Mucilage to HPAM improves EOR efficiency by reducing blockage while maintaining favorable fluid mobility [

80,

81].

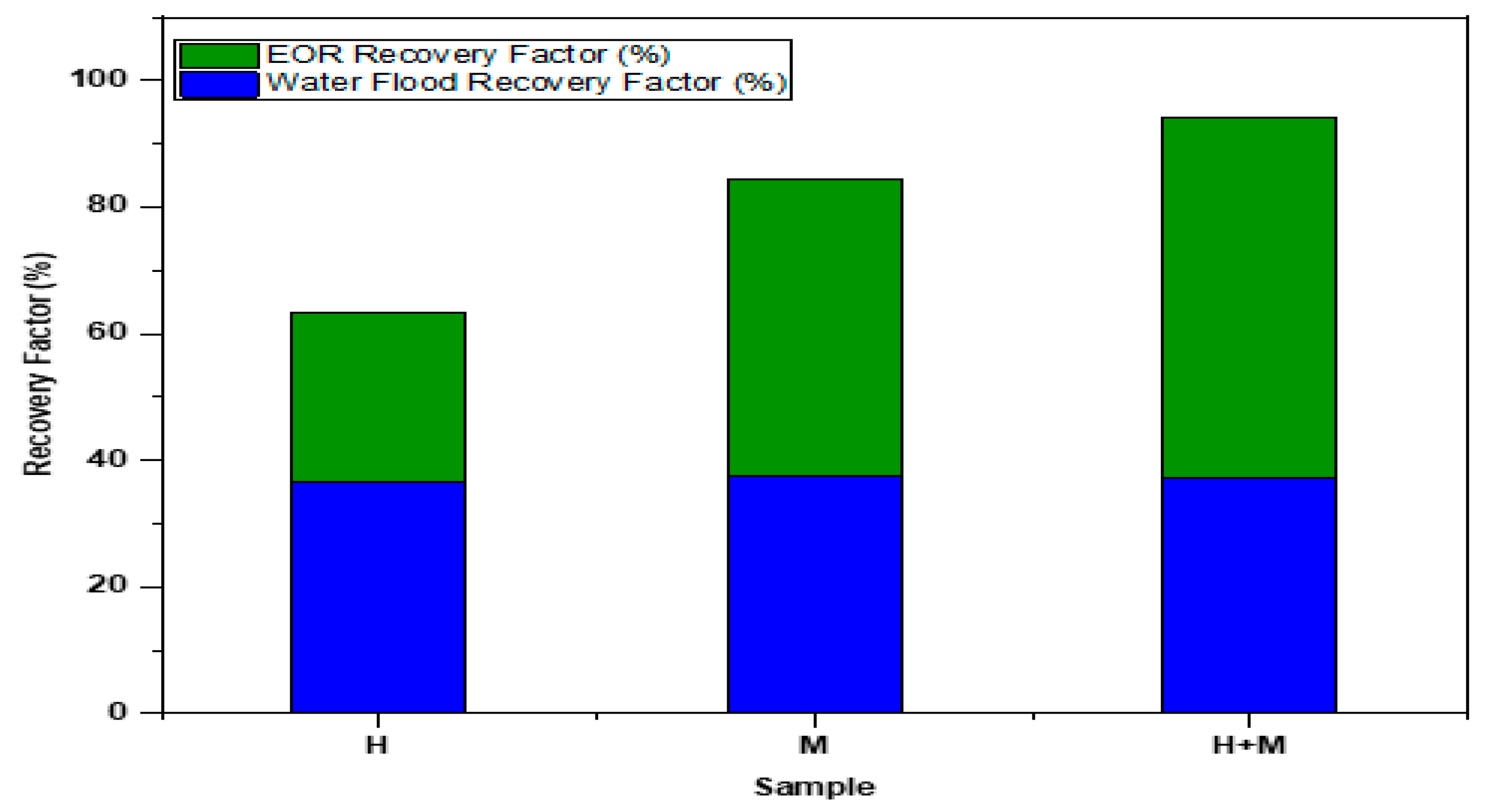

The recovery factors varied significantly among the polymer solutions: the HPAM solution achieved a recovery factor of 63.3%, while the

Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage alone achieved 84.35%. The HPAM/mucilage blend provided the highest recovery, reaching an impressive 94.28% recovery factor. These results, shown in

Figure 10, emphasise the blend's superior performance in enhancing oil recovery compared to the individual polymer solutions, highlighting the potential benefits of combining synthetic and biopolymer solutions in EOR processes.

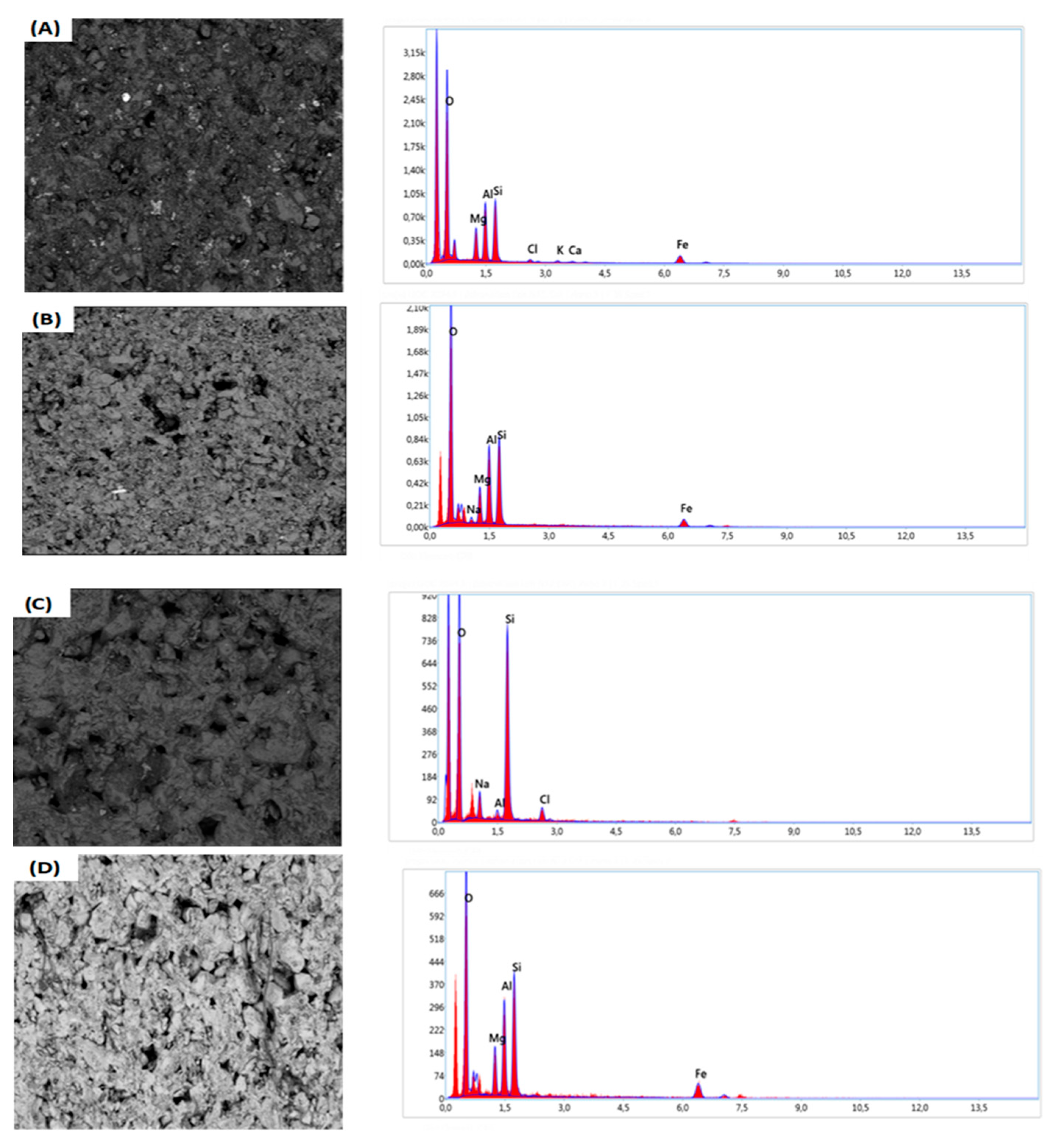

3.6.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDX) Analysis of the Plugs Before and After Injection

The MEB/EDX analysis of the core plug samples before and after injection revealed significant changes in chemical composition, providing valuable insights into the interaction between the polymers and the core's pore matrix (

Figure 11).

Pre-injection analyses showed that the plugs, sourced from a Triassic clay formation, contained elements such as oxygen (O), silicon (Si), magnesium (Mg), aluminum (Al), and iron (Fe), in agreement with observations from YI Wayan Rakananda Saputra [

82]. The prevalence of oxygen and silicon confirms the presence of silicate minerals, notably quartz. At the same time, magnesium and iron suggest the presence of clay minerals such as chlorites, consistent with findings reported by Magda I. Youssif [

83]. The elemental composition indicates the rocks' clayey and siliceous nature, which is essential for understanding the interactions during the injection of recovery fluids.

Post-injection results revealed notable characteristics. For Plug 11, EDX analysis highlighted concentrations of sodium (Na), iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), and silicon (Si) following HPAM injection. The detection of sodium suggests ionic exchanges between the fluid and the rock minerals, an observation also reported by Imane Guetni [

84]. The persistent concentrations of iron and magnesium in the rock underscore the stability of the minerals. At the same time, the limited pore openings indicate that HPAM injection has modestly altered the pore structure. These interactions may influence fluid mobility and the efficiency of the recovery process, as discussed in the work of Gordon M [

85], which emphasises that high-pressure losses can limit recovery.

For Plug 12, the SEM/EDX analysis of the polymer based on

Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes showed a high concentration of silicon, along with oxygen (O), sodium (Na), aluminum (Al), and chlorine (Cl). The results indicate that this polymer promotes pore stability while enhancing fluid mobility, contrasting with conventional recovery fluids. Other studies, such as those by Yongqiang Bi [

86], also report that natural polymers can reduce plugging, thereby improving recovery efficiency.

Finally, plug 13 revealed significant characteristics following the injection of the HPAM and mucilage mixture. The predominant presence of silicon and other elements such as oxygen, magnesium, and iron demonstrated that the mixture optimises pore structure management. This interaction is similar to that observed by Khalaf G. Salem [

87], who found that polymeric mixtures can enhance recovery performance by facilitating fluid circulation. The results indicate that Mucilage, combined with HPAM, provides considerable advantages for pore structure management, promoting faster oil recovery. In summary, this study highlights the importance of developing innovative polymer formulations that minimise undesirable interactions while maximising the efficiency of enhanced oil recovery.

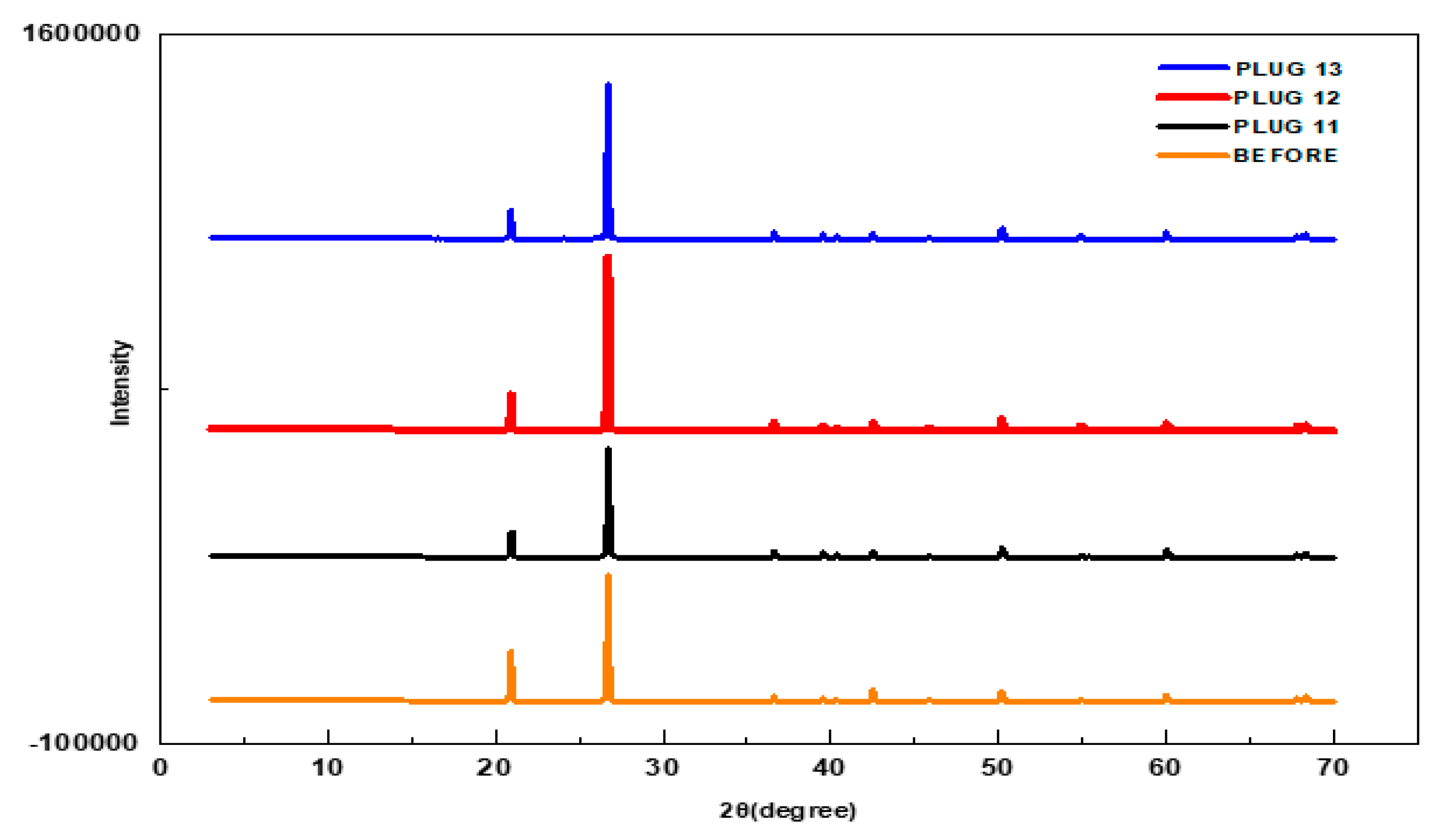

3.6.4. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis of Plugs Before and After Injection

To assess the mineralogical changes occurring in the plugs following the injection of various fluids, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted (

Figure 12). This technique allows for a comparative evaluation of the mineralogical composition of the plugs before and after treatment, providing crucial insights into the interactions between the injected fluids and the rock matrix. The results highlight potential structural and mineralogical changes that could influence the efficiency of enhanced oil recovery (EOR) processes.

Pre-injection XRD analysis revealed that the reservoir plugs were primarily composed of quartz (SiO₂) and clinochlore-1M2b ((Mg, Fe), (Si, Al)₄O₁₀(OH)₈). These findings establish a stable baseline for evaluating mineralogical alterations induced by injecting different fluids.

Post-injection, the XRD results showed distinct variations based on the type of fluid used. For

Plug 11, treated with HPAM, the XRD peaks remained relatively stable, indicating limited interaction with the rock and no significant mineralogical changes. This mineralogical stability aligns with the findings of Eseosa M. Ekanem [

88], who reported similar stability in mineralogy when using synthetic polymers.

In contrast,

Plug 12 (mucilage) and

Plug 13 (mucilage-HPAM mixture) exhibited notable increases in the intensity of XRD peaks after injection. This enhancement suggests increased crystallisation or mineral reorganisation within the rock pores, indicating a more pronounced interaction of mucilage-containing fluids with the rock minerals. These results align with the observations of Mohammed Bashir Abdullahi [

89], who found that natural polymer fluids promote significant mineral reactivity and alteration compared to synthetic polymers.

The pronounced mineral interactions facilitated by the Mucilage contrast sharply with the relative stability observed with HPAM, highlighting the advantages of biopolymer formulations in EOR. This finding supports the conclusions drawn by A. N. El-hoody [

90], which emphasise the superior performance of natural polymers in enhancing oil recovery through improved mineral interactions.

In summary, this study underscores the importance of exploring innovative polymer formulations, such as mucilage from Opuntia ficus-indica, which minimises undesired interactions while promoting beneficial modifications in the rock's pore structure. These changes can potentially enhance EOR efficiency by improving fluid flow within the reservoir, without significantly altering its mineral composition.

4. Conclusions

This study highlights the potential of Opuntia ficus-indica powder extract as a promising alternative to traditional hydrophilic polyacrylamides (HPAM) for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) applications. The thermal analysis (TGA) showed that Opuntia mucilage and HPAM exhibit similar thermal stability, suggesting that both materials could withstand the harsh conditions typically encountered in oil recovery operations.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) revealed significant differences in the chemical composition and molecular characteristics between Opuntia mucilage, HPAM, and their blend. These differences likely play a crucial role in how the polymers interact with the reservoir matrix, potentially influencing the effectiveness of the recovery fluids in various reservoir conditions.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis indicated that Opuntia ficus-indica extract has a crystalline structure, unlike the amorphous structure of HPAM. This structural variation may affect the interaction between the polymer solutions and the reservoir, further influencing their performance during recovery.

Core flooding tests demonstrated that Opuntia mucilage, combined with HPAM, significantly improves pore saturation and oil recovery performance. The HPAM/mucilage blend showed a significant improvement in oil recovery, suggesting a synergistic effect between the two agents that enhances the overall efficiency of the EOR process. The recovery factors for the different solutions were also significantly different: HPAM achieved a recovery factor of 63.3%, Opuntia mucilage alone achieved 84.35%, and the HPAM/mucilage blend achieved the highest recovery factor at 94.28%, underlining the superior performance of the blend in enhancing oil recovery compared to the individual solutions.

Additionally, using Opuntia mucilage extract improved pressure stability and facilitated better fluid mobility through the reservoir pores, as evidenced by the enhanced pore opening observed in scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis. This improvement was more pronounced in plugs treated with the mucilage solution, further supporting the potential of this biopolymer in oil recovery applications.

In summary, Opuntia ficus-indica powder extract presents a viable alternative to traditional HPAM in EOR, offering efficiency, fluid mobility, and environmental sustainability advantages. The HPAM/mucilage blend, in particular, shows a remarkable increase in oil recovery and could represent a promising approach to optimise EOR processes. However, further studies and field trials are needed to validate these findings and assess the long-term environmental impact of incorporating natural materials into oil recovery processes. Developing innovative polymer formulations combining natural biopolymers like Opuntia mucilage with synthetic polymers could pave the way for more sustainable and cost-effective solutions in the petroleum industry.

Author Contributions

Kamila BOURKAIB conceptualized the project, developed the methodology, coordinated all stages, managed the data, performed the formal analysis, and wrote the manuscript. Abdelkader HADJSADOK supervised the work and participated in revising the manuscript. Charaf Eddine IZOUNTAR, Mohamed Fouad ABI MOULOUD, and Abdelali GUEZEI contributed to the implementation and the methodology of core flooding tests and injection experiments at DLCC SONATRACH. Amine BOUHAFES and Amar Isseri, as laboratory managers at DLCC SONATRACH, coordinated the experimental protocols. Djamila MAATALAH and Meriem BRAIK guided the experiment and contributed to the revision of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has not been funded.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alvarado, V.; Manrique, E. Enhanced Oil Recovery: An Update Review. Energies 2010, 3, 1529–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.; Ivanova, A.; Cheremisin, A. Foam EOR as an Optimization Technique for Gas EOR: A Comprehensive Review of Laboratory and Field Implementations. Energies 2023, 16, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, A.; Kalam, S.; Kamal, M.S.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Solling, T. EOR Perspective of Microemulsions: A Review. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2022, 208, 109312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, K.; Masalmeh, S. A Review of EOR Techniques for Carbonate Reservoirs in Challenging Geological Settings. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2020, 195, 107889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malozyomov, B.V.; Martyushev, N.V.; Kukartsev, V.V.; Tynchenko, V.S.; Bukhtoyarov, V.V.; Wu, X.; Tyncheko, Y.A.; Kukartsev, V.A. Overview of Methods for Enhanced Oil Recovery from Conventional and Unconventional Reservoirs. Energies 2023, 16, 4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.-L.; Zhou, B.-B.; Issakhov, M.; Gabdullin, M. Advances in Enhanced Oil Recovery Technologies for Low Permeability Reservoirs. Petroleum Science 2022, 19, 1622–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, S.; Al-Shargabi, M.; Wood, D.A.; Rukavishnikov, V.S.; Minaev, K.M. Experimental and Field Applications of Nanotechnology for Enhanced Oil Recovery Purposes: A Review. Fuel 2022, 324, 124669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.-X.; Li, S.-Y.; Li, B.-F.; Chen, D.-Q.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Li, Z.-M. A Review of Development Methods and EOR Technologies for Carbonate Reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2020, 17, 990–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lai, J.; Fan, X.; Shu, H.; Wang, G.; Ma, X.; Liu, M.; Guan, M.; Luo, Y. Insights in the Pore Structure, Fluid Mobility and Oiliness in Oil Shales of Paleogene Funing Formation in Subei Basin, China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2020, 114, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetni, I.; Marlière, C.; Rousseau, D.; Pelletier, M.; Bihannic, I.; Villiéras, F. Transport of EOR Polymer Solutions in Low Permeability Porous Media: Impact of Clay Type and Injection Water Composition. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2020, 186, 106690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Hou, Z.; Wu, X.; Song, K.; Yang, E.; Huang, B.; Dong, C.; Lu, S.; Sun, L.; Gai, J.; et al. A New Method for Calculating the Relative Permeability Curve of Polymer Flooding Based on the Viscosity Variation Law of Polymer Transporting in Porous Media. Molecules 2022, 27, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.; Yu, H.; Xu, G.; Liu, P.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y. Polymer-Surfactant Flooding in Low-Permeability Reservoirs: An Experimental Study. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 4595–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Song, K.; Hilfer, R. A Critical Review of Capillary Number and Its Application in Enhanced Oil Recovery.; August 31 2020; p. D031S046R001.

- Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, B.; Zuo, M.; Chen, H. The Influence Mechanism and the Contribution of Capillary Force and Gravity to Recovery in Spontaneous Imbibition in Low Permeability Reservoirs. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 2024, 45, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Cui, Y.; Wang, S. Study of the Influence of Dynamic and Static Capillary Forces on Production in Low-Permeability Reservoirs. Energies 2023, 16, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Tang, X.; Xu, M.; Li, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Kong, D.; Wen, Y.; Li, Q. Surfactant–Polymer Viscosity Effects on Enhanced Oil Recovery Across Pore Structures: Microfluidic Insights from Pore Scale to Darcy Scale. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 17380–17391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Abdollahi, H.; Derikvand, Z.; Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A.; Mosavi, A.; Nabipour, N. Insights into the Effects of Pore Size Distribution on the Flowing Behavior of Carbonate Rocks: Linking a Nano-Based Enhanced Oil Recovery Method to Rock Typing. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2020, 10, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, S.; Abu-Khamsin, S.A.; Kamal, M.S.; Patil, S. A Review on Surfactant Retention on Rocks: Mechanisms, Measurements, and Influencing Factors. Fuel 2021, 293, 120459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.; Al-Shalabi, E.W.; AlAmeri, W. A Review on Retention of Surfactants in Enhanced Oil Recovery: A Mechanistic Insight. Geoenergy Science and Engineering 2023, 230, 212243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A.H.; Alsaif, B.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Khan, S.; Kamal, M.S.; Patil, S.; Al-Shalabi, E.W.; Hassan, A.M. Advances in Understanding Polymer Retention in Reservoir Rocks: A Comprehensive Review. Polymer Reviews 2024, 64, 1387–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emad W., A. -S. Effects of Trapping Number on Biopolymer Flooding Recovery of Carbonate Reservoirs. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2022, 49, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beteta, A.; McIver, K.; Vazquez, O.; Boak, L.; Jordan, M.; Shields, R. The Impact of EOR Polymers on Scale Inhibitor Adsorption. SPE Virtual International Oilfield Scale Conference and Exhibition 2020 2020. [CrossRef]

- Belhaj, A.; Elraies, K.; Sarma, H.; Muhamad Shuhili, J.A.; Mahmood, S.; Alnarabiji, M. Surfactant Partitioning and Adsorption in Chemical EOR: The Neglected Phenomenon in Porous Media; 2021.

- Skauge, A.; Zamani, N.; Gausdal Jacobsen, J.; Shaker Shiran, B.; Al-Shakry, B.; Skauge, T. Polymer Flow in Porous Media: Relevance to Enhanced Oil Recovery. Colloids and Interfaces 2018, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancela, B.R.; Palermo, L.C.M.; de Oliveira, P.F.; Mansur, C.R.E. Rheological Study of Polymeric Fluids Based on HPAM and Fillers for Application in EOR. Fuel 2022, 330, 125647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, S. Effect of Salt-Resistant Monomers on Viscosity of Modified Polymers Based on the Hydrolyzed Poly-Acrylamide (HPAM): A Molecular Dynamics Study. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2021, 325, 115161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, P.-S.; Lim, J.-S.; Huh, C. Temperature Dependence of the Shear-Thinning Behavior o Partially Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide Solution for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Journal of Energy Resources Technology 2020, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.F.; Santos, A.S.; de Oliveira, P.F.; Santos, I.C.V.M.; Mansur, C.R.E. Statistical and Rheological Evaluation of the Effect of Salts in Partially Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide Solutions. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2024, 141, e55278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Qin, F.; Liu, T.; Zhang, X. Enhanced Oil Recovery Performance and Solution Properties of Hydrophobic Associative Xanthan Gum. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaie, F.; Esmaeilnezhad, E.; Jin Choi, H. Xanthan Gum-Added Natural Surfactant Solution of Chuback: A Green and Clean Technique for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2022, 354, 118909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaeed, Shimaa. M.; Zaki, E.G.; Omar, W.A.E.; Ashraf Soliman, A.; Attia, A.M. Guar Gum-Based Hydrogels as Potent Green Polymers for Enhanced Oil Recovery in High-Salinity Reservoirs. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 23421–23431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, M.; Haq, B.; Al Shehri, D.; Rahman, M.M.; Muhammed, N.S.; Mahmoud, M. Modification of Xanthan Gum for a High-Temperature and High-Salinity Reservoir. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAYYOUH, M.H.; AL-BLEHED, M. Screening Criteria for Enhanced Recovery of Saudi Crude OUs. Energy Sources 1990, 12, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.A.; Lins, A.G.; Silva, I.P. Lessons Learned From Polymer Flooding Pilots in Brazil. In Proceedings of the Day 2 Thu, March 16, 2017; SPE: Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, March 15 2017; p. D021S013R001.

- Shuker, M.T.; Buriro, M.A.; Hamza, M.M. Enhanced Oil Recovery: A Future for Pakistan. In Proceedings of the SPE/PAPG Annual Technical Conference; SPE: Islamabad, Pakistan, December 3 2012; p. SPE-163124-MS.

- Helmi, M.E.; Abu El Ela, M.; Desouky, S.M.; Sayyouh, M.H. Effects of Nanocomposite Polymer Flooding on Egyptian Crude Oil Recovery. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 2020, 10, 3937–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.A.; Musa, T.A.; Doroudi, A. Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery Pilot Design for Heglig Main Field-Sudan. SPE Saudi Arabia Section Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition 2015, SPE-177984-MS. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, M.; Castro, R.H.; Corredor, L.M.; Fernández, F.R.; Zapata, J.; Jimenez, J.A.; Reyes, J.D.; Rojas, D.M.; Jimenez, R.; Acosta, T.; et al. Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery Experiences in Colombia: Field Pilots Review. SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference 2024, D031S019R003. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Han, M.; Fuseni, A.; Alsofi, A.M. An Approach to Evaluate Polyacrylamide-Type Polymers’ Long-Term Stability under High Temperature and High Salinity Environment. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2019, 180, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Khan, N.; Pu, C. A New Method of Plugging the Fracture to Enhance Oil Production for Fractured Oil Reservoir Using Gel Particles and the HPAM/Cr3+ System. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lin, M.; Guo, J.; Wang, D.; Xu, F.; Li, M. Plugging Properties and Profile Control Effects of Crosslinked Polyacrylamide Microspheres. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2016, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H. How to Select Polymer Molecular Weight and Concentration to Avoid Blocking in Polymer Flooding? In Proceedings of the Day 1 Tue, November 07, 2017; SPE: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, November 7 2017; p. D011S001R005.

- Wu, H.; Ge, J.; Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Guo, H. Developments of Polymer Gel Plug for Temporary Blocking in SAGD Wells. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2022, 208, 109650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekunke, V.; Kosi, S.; Junior, J.; Obada, O.; Ikechukwu, S.; Ifechukwu, J.; Collins, I.; Chadi, P.; Ibe, M.; Peter, Y. ENHANCED OIL RECOVERY METHODS USING BIODEGRADABLE MATERIALS IN DIFFERENT RESERVOIRS. 2024, 12, 647–664. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, B.; Liu, J.; Liu, K.; Al Shehri, D. The Role of Biodegradable Surfactant in Microbial Enhanced Oil Recovery. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2020, 189, 106688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Garcia, C.; Fessard, A.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Aboudia, A.; Ouadia, A.; Remize, F. Opuntia Ficus Indica Edible Parts: A Food and Nutritional Security Perspective. Food Reviews International 2022, 38, 930–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.C. de A.; Barreto, S.M. de A.G.; Ostrosky, E.A.; da Rocha-Filho, P.A.; Veríssimo, L.M.; Ferrari, M. Production and Characterization of Cosmetic Nanoemulsions Containing Opuntia Ficus-Indica (L.) Mill Extract as Moisturizing Agent. Molecules 2015, 20, 2492–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, N.; Kriaa, M.; Kammoun, R. Extraction and Characterization of Three Polysaccharides Extracted from Opuntia Ficus Indica Cladodes. Int J Biol Macromol 2016, 92, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinzio, C.; Ayunta, C.; Alancay, M.; de Mishima, B.L.; Iturriaga, L. Physicochemical and Rheological Properties of Mucilage Extracted from Opuntia Ficus Indica (L. Miller). Comparative Study with Guar Gum and Xanthan Gum. Food Measure 2018, 12, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Torres, L.; Brito-De La Fuente, E.; Torrestiana-Sanchez, B.; Katthain, R. Rheological Properties of the Mucilage Gum (Opuntia Ficus Indica). Food Hydrocolloids 2000, 14, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourkaib, K.; Hadjsadok, A.; Djedri, S. Synergistic Effect of Opuntia Ficus-Indica Cladode Mucilage on Physicochemical and Rheological Properties of HPAM Polymer Solutions for EOR Application. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2024, 691, 133794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, L.A.; Nunes, C.A.; Pereira, J. Physical and Chemical Analysis in Crude Taro Mucilage Obtained by Simple Extraction Technique. Boletim do Centro de Pesquisa de Processamento de Alimentos 2019, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otálora, M.C.; Gómez Castaño, J.A.; Wilches-Torres, A. Preparation, Study and Characterization of Complex Coacervates Formed between Gelatin and Cactus Mucilage Extracted from Cladodes of Opuntia Ficus-Indica. LWT 2019, 112, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otálora, M.C.; Carriazo, J.G.; Iturriaga, L.; Nazareno, M.A.; Osorio, C. Microencapsulation of Betalains Obtained from Cactus Fruit (Opuntia Ficus-Indica) by Spray Drying Using Cactus Cladode Mucilage and Maltodextrin as Encapsulating Agents. Food Chem 2015, 187, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhivi, V.E.; Venter, S.; Amonsou, E.O.; Kudanga, T. Composition, Thermal and Rheological Properties of Polysaccharides from Amadumbe (Colocasia Esculenta) and Cactus (Opuntia Spp.). Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 195, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otálora, M.C.; Wilches-Torres, A.; Castaño, J.A.G. Extraction and Physicochemical Characterization of Dried Powder Mucilage from Opuntia Ficus-Indica Cladodes and Aloe Vera Leaves: A Comparative Study. Polymers 2021, 13, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, J.J.; Schulz, D.N.; Siano, D.B.; Bock, J. Thermal Analysis of Acrylamide-Based Polymers. In Analytical Calorimetry: Volume 5; Johnson, J.F., Gill, P.S., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1984; pp. 43–55. ISBN 978-1-4613-2699-1. [Google Scholar]

- Neamtu, I.; Chiriac, A.P.; Nita, L.E. Characterization of Poly(Acrylamide) as Temperature- Sensitive Hydrogel.

- Olajire, A.A. Review of ASP EOR (Alkaline Surfactant Polymer Enhanced Oil Recovery) Technology in the Petroleum Industry: Prospects and Challenges. Energy 2014, 77, 963–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouhammou, M.; Nabil, B.; Hidar, N.; Ouaabou, R.; Bouchdoug, M.; Jaouad, A.; Mahrouz, M. Chemical Activation of the Skin of Prickly Pear Fruits and Cladode Opuntia Megacantha: Treatment of Textile Liquid Discharges. South African Journal of Chemical Engineering 2021, 37, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Fernandez, P.A.; Miedema, S.J.; Bruning, H.; Leermakers, F.A.M.; Rijnaarts, H.H.M.; Post, J.W. Influence of Solution Composition on Fouling of Anion Exchange Membranes Desalinating Polymer-Flooding Produced Water. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2019, 557, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benhamou, A.; Boussetta, A.; Grimi, N.; Idrissi, M.E.; Nadifiyine, M.; Barba, F.J.; Moubarik, A. Characteristics of Cellulose Fibers from Opuntia Ficus Indica Cladodes and Its Use as Reinforcement for PET Based Composites. Journal of Natural Fibers 2022, 19, 6148–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Padilla, M.; Rivera-Muñoz, E.M.; Gutiérrez-Cortez, E.; del López, A.R.; Rodríguez-García, M.E. Characterization of Crystalline Structures in Opuntia Ficus-Indica. J Biol Phys 2015, 41, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, M.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Jiang, G. Biodegradation of Partially Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide by Bacteria Isolated from Production Water after Polymer Flooding in an Oil Field. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010, 184, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, M.A.; Pervaiz, S.; Hu, Z.; Nourafkan, E.; Wen, D. Improved Rheology and High-Temperature Stability of Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide Using Graphene Oxide Nanosheet. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2019, 136, 47582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje, P.V.; Baran, E.J. Complex Biomineralization Pattern in Cactaceae. Journal of Plant Physiology 2004, 161, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azli, N.B.; Junin, R.; Agi, A.A.; Risal, A.R. Partially Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide Apparent Viscosity in Porous Media Enhancement by Silica Dioxide Nanoparticles under High Temperature and High Salinity. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2021, 25, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magami, S.; Haruna, M. Influence of Nanoparticle Size Distributions on the (in)Stability and Rheology of Colloidal SiO2 Dispersions and HPAM/SiO2 Nanofluid Hybrids. Fine Chemical Engineering 2023, 4, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, A.; Higuera-Ciapara, I.; Goycoolea, F. Rheology and Aggregation of Cactus (Opuntia Ficus-Indica) Mucilage in Solution. Journal of the Professional Association for Cactus Development 1997, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas Lopes, L.; Silveira, B.; Moreno, R. Rheological Evaluation of HPAM Fluids for EOR Applications. Int. J. Eng. Technol. IJET-IJENS 2014, 14, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Corredor, L.; Maini, B.; Husein, M. Corredor, L.; Maini, B.; Husein, M. Improving Polymer Flooding by Addition of Surface Modified Nanoparticles.; OnePetro, October 23 2018.

- Wang, Y.; He, Z.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Ding, M.; Yang, Z.; Qian, C. Stability and Rheological Properties of HPAM/Nanosilica Suspensions: Impact of Salinity. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2020, 587, 124320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seright, R.S.; Seheult, M.; Talashek, T. Injectivity Characteristics of EOR Polymers. SPE Reservoir Evaluation & Engineering 2009, 12, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Seright, R. Hydrodynamic Retention and Rheology of EOR Polymers in Porous Media. Proceedings - SPE International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry 2015, 1, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryou, J.-E.; Jung, J. Characteristics of Thermo-Gelation Biopolymer Solution Injection into Porous Media. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 384, 131451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, W.; Niu, H.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Song, Z.; Kong, D. 2-D Porous Flow Field Reveals Different EOR Mechanisms between the Biopolymer and Chemical Polymer. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2022, 210, 110084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Tian, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Fan, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Cao, M.; et al. Heterogeneity Control Ability in Porous Media: Associative Polymer versus HPAM. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2019, 183, 106425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaddahen, A. Étude Expérimentale Multi-Échelle et Modélisation Hybride Prédictive Du Comportement, de l’endommagement et de La Durée de Vie En Fatigue d’un Matériau Composite Polypropylène / Fibres de Verre, 2020.

- Corredor, L.M.; Aliabadian, E.; Husein, M.; Chen, Z.; Maini, B.; Sundararaj, U. Heavy Oil Recovery by Surface Modified Silica Nanoparticle/HPAM Nanofluids. Fuel 2019, 252, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, N.; Tang, L.; Jia, N.; Qiao, D.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X. Feasibility Study of Applying Modified Nano-SiO2 Hyperbranched Copolymers for Enhanced Oil Recovery in Low-Mid Permeability Reservoirs. Polymers 2019, 11, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhu, B.; Huang, X.; Leng, Z.; Chen, L.; Song, F. Enhanced Oil Recovery by a Suspension of Core-Shell Polymeric Nanoparticles in Heterogeneous Low-Permeability Oil Reservoirs. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2019, 9, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, I.W.R.; Adebisi, O.; Ladan, E.B.; Bagareddy, A.; Sarmah, A.; Schechter, D.S. The Influence of Oil Composition, Rock Mineralogy, Aging Time, and Brine Pre-Soak on Shale Wettability. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssif, M.I.; El-Maghraby, R.M.; Saleh, S.M.; Elgibaly, A. Silica Nanofluid Flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery in Sandstone Rocks. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum 2018, 27, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetni, I.; Marliere, C.; Rousseau, D.; Bihannic, I.; Pelletier, M.; Villieras, F. Transport of HPAM Solutions in Low Permeability Porous Media: Impacts of Salinity and Clay Content. SPE Europec featured at 81st EAGE Conference and Exhibition 2019, D041S011R001. [CrossRef]

- Graham, G.M.; Frigo, D.M. Production Chemistry Issues and Solutions Associated with Chemical EOR. SPE International Conference on Oilfield Chemistry 2019, D021S008R001. [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Xiu, J.; Ma, T. Application Potential Analysis of Enhanced Oil Recovery by Biopolymer-Producing Bacteria and Biosurfactant-Producing Bacteria Compound Flooding. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, K.G.; Salem, A.M.; Tantawy, M.A.; Gawish, A.A.; Gomaa, S.; El-hoshoudy, A.N. A Comprehensive Investigation of Nanocomposite Polymer Flooding at Reservoir Conditions: New Insights into Enhanced Oil Recovery. J Polym Environ 2024, 32, 5915–5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanem, E.M.; Rücker, M.; Yesufu-Rufai, S.; Spurin, C.; Ooi, N.; Georgiadis, A.; Berg, S.; Luckham, P.F. Novel Adsorption Mechanisms Identified for Polymer Retention in Carbonate Rocks. JCIS Open 2021, 4, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir Abdullahi, M.; Rajaei, K.; Junin, R.; Bayat, A.E. Appraising the Impact of Metal-Oxide Nanoparticles on Rheological Properties of HPAM in Different Electrolyte Solutions for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2019, 172, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-hoshoudy, A.N. Experimental and Theoretical Investigation for Synthetic Polymers, Biopolymers and Polymeric Nanocomposites Application in Enhanced Oil Recovery Operations. Arab J Sci Eng 2022, 47, 10887–10915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).