1. Introduction

The first medical article on the hazards of asbestos dust appeared in the British Medical Journal in 1924 and since then, several diseases related to asbestos exposure have been described [

1]. Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) and lung cancer (LC) represent two types of neoplasia associated with occupational asbestos exposure [

2,

3,

4] and due to the late and non-ubiquitous ban on asbestos, as well as the long latency period of these diseases, they continue to represent a pressing and current issue. Although a century has passed since the first report on the pathological consequences of asbestos exposure, the mechanisms underlying lung and pleural genotoxicity are still far from being understood. Currently local disruption of iron homeostasis described both in animal models and patients affected by asbestos-related cancers [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] and the resulting iron-induced oxidative stress are considered the main mechanisms of asbestos dependent genotoxicity [

7,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Iron is a fundamental micronutrient exploited by all living cells in a wide variety of physiological processes. The ability of iron to gain and lose electrons, cycling between ferrous (Fe2+) and ferric (Fe3+) states, makes it able to act as a co-factor of several ferro-dependent enzymes involved in DNA replication and repair, cell respiration and cell cycle progression [

19]. However, excess of redox-active iron can foster the generation of highly reactive oxygen species (ROS) which are potentially mutagenic due to their ability to damage DNA [

20,

21]. In case of asbestos, iron is present as structural component of amphiboles minerals like amosite, crocidolite and actinolite fibers, while serpentine chrysotile is able to induce haemolysis and thus iron release [

22]. Fiber-adsorbed iron, once internalized by the cell, acts as a catalyst in ROS production through Fenton reaction [

23,

24]. In addition, internalized asbestos fibers can adsorb the host metal on their surface, tricking the cell to perceive a functional iron deficiency [

25,

26] (

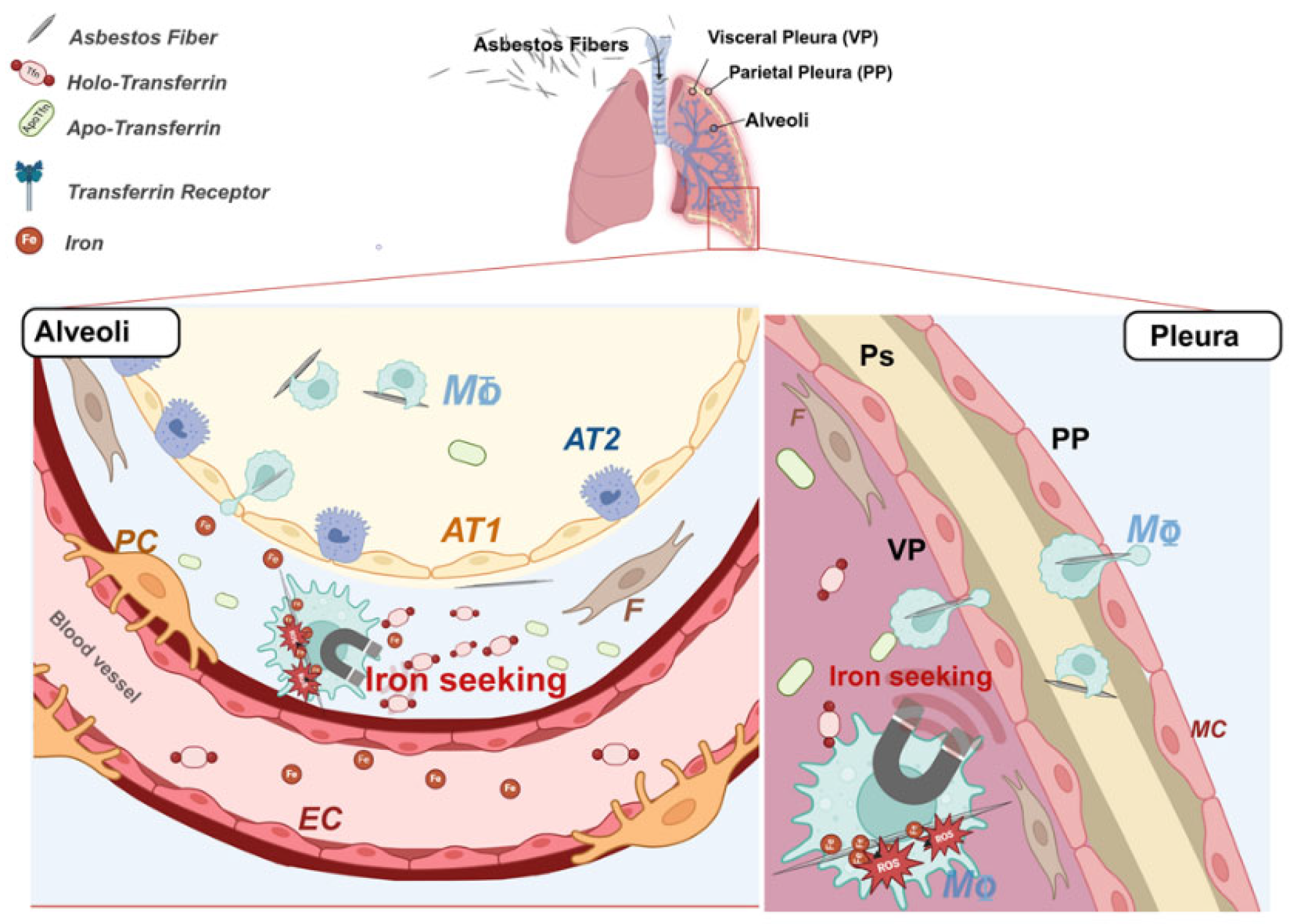

Figure 1). In an attempt to re-establish iron homeostasis, the cell responds by either increasing iron uptake and/or decreasing iron egress, thus contributing to the establishment of a harmful iron-overload environment that prompts a cascade of cell signaling and mediator release leading to inflammation, fibrosis and neoplastic transformation [

12,

25,

27] (

Figure 1). Although mesothelioma has been considered for many years the paradigm of environmentally determined type of cancer, the presence of genetic predisposing factors in the aetiology of the disease has been proposed by many studies [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37] and germline variants in BAP1 tumor suppressor gene have been reported as a high-risk factor for MPM [

38]. In case of asbestos-related LC the contribution of genetics is still poorly understood, even though individual genetic variations able to affect the risk of developing this neoplasm have been reported [

39,

40,

41].

In a previous study, we addressed the association between a full panel of iron metabolism genes with susceptibility to develop MPM and LC in a highly selected asbestos-exposed population employing post-mortem paraffin-embedded tissues [

42,

43]. Three SNPs, two non-coding localized in the ferritin heavy chain (FTH1) and transferrin (TF) genes and a coding SNP in the hephaestin gene (HEPH), resulted protective against the development of both asbestos related neoplasms. The coding SNP of the multicopper ferroxidase Heph has attracted our attention, since it could represent a potential prognostic indicator once established a clear correlation between Heph functional alterations, iron metabolism dysregulation, and protection against MPM. Heph belongs to a small family of multicopper ferroxidases (MCFs) which promote the transfer of iron across biological membranes in concert with the multi-pass membrane protein ferroportin (Fpn1), the only known iron exporter identified in mammals [

44,

45]. The MCFs family includes three members namely ceruloplasmin (CP), hephaestin (Heph), and zyklopen (ZP) [

46], all of them are characterized by the presence of multiple copper atoms that couple substrate oxidation to full reduction of oxygen to water [

47]. By oxidizing ferrous iron to its ferric form, Heph enhances not only the efficiency of iron export through Fpn1 but also iron loading to the major iron-carrier plasma glycoprotein transferrin (Tfn) [

48]. These activities are exploited by enterocytes to promote nutritional iron absorption [

49,

50], but Heph expression is not limited to the gastrointestinal tract. This ferroxidase, indeed, has been shown to be expressed by brain microvasculature endothelial cells (BMVEC) where it exerts control over brain iron delivery across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [

51,

52]. In particular, iron needs are sensed by Heph interaction with iron-depleted apo-transferrin (apo-Tfn) [

53], whose local levels raise when tissue iron utilization is elevated. Therefore, Heph/apo-Tfn interaction would coordinate ferrous iron egress with its conversion into the Tfn loadable ferric form. In asbestos-related LC and MPM the identified protective Heph SNP (rs3747359) introduces an aspartic acid substitution by histidine at position 568 (D568H) [

42,

43]. According to in silico analysis, this amino acid change is predicted to deleteriously impact on Heph function. We recently addressed Heph distribution in the context of lung cancer and found the protein to be mainly expressed by vascular cells [

54], a localization reminiscent of what has been observed at neuro-vascular unit. At the vascular compartment of the pulmonary tissue Heph could exert a similar control over local iron supply to that shown in brain, thus extending the paradigm uncovered at the BBB [

53]. In this context, functional alterations of the ferroxidase may affect iron procurement in response to a specific tissue request and thus either favoring or hampering the establishment of a harmful iron-overload condition.

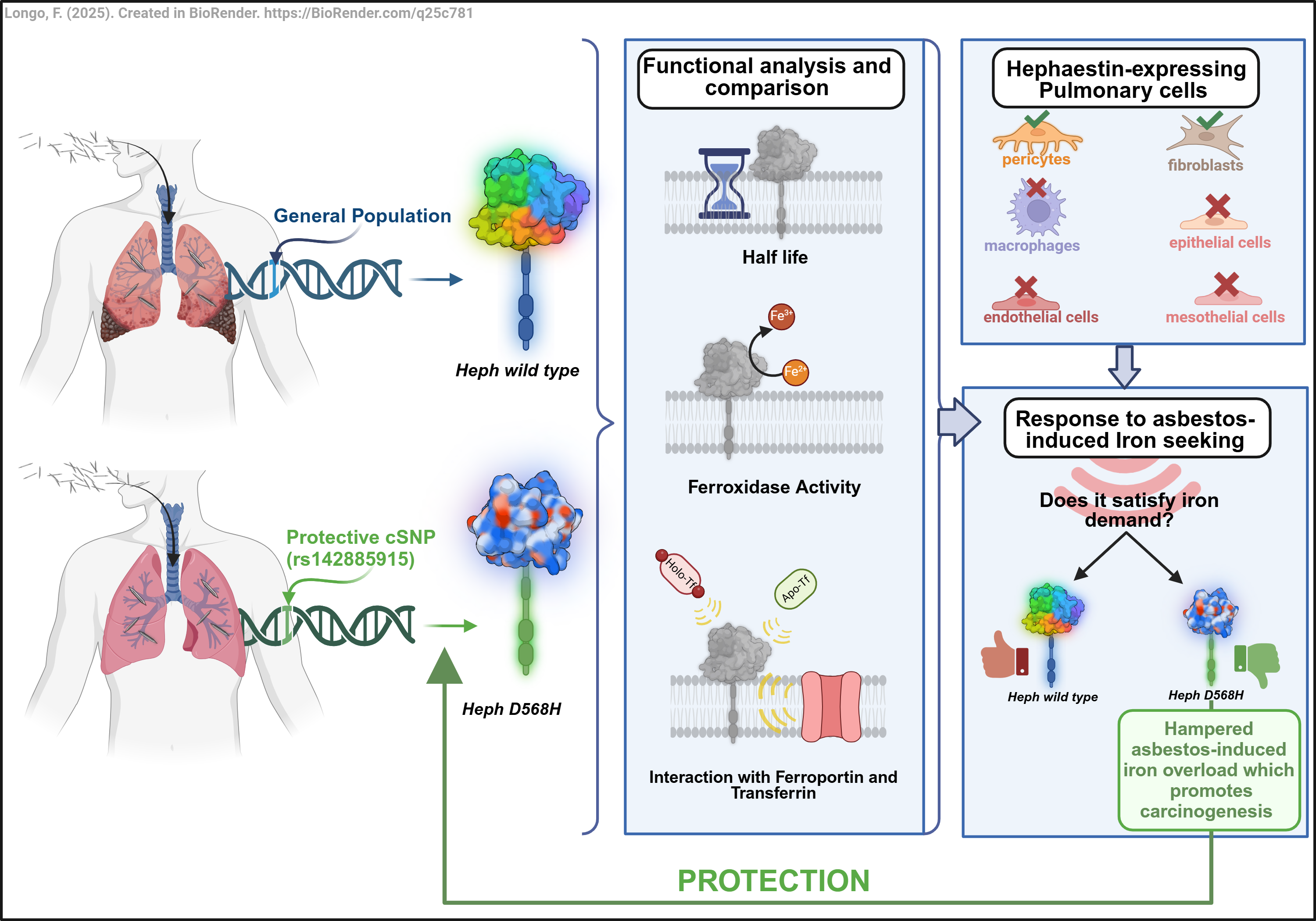

In the present study we conducted an in-depth functional characterization of the HephD568H variant to gain valuable insights on the molecular basis of its protective activity in asbestos-related carcinogenesis. Our findings revealed that the amino acid change does not affect Heph ferroxidase activity nor its ability to interact with Fpn1. Interestingly, HephD568H/Fpn1 complexes, while being more enriched at the plasma membrane as compared to HephWT, resulted impaired in apo-transferrin recruitment and thus less prone to iron export. In healthy human lung, endogenous Heph was found expressed by two resident mesenchymal cell populations, namely lung pericytes and fibroblasts: the former are functionally and physically associated with the vascular endothelium, while the latter are situated just beneath the alveolar epithelial cells or scattered in the interstitium. At this location, the expression of an Heph variant compromised in the ability to sense iron demand is expected to limit iron supply in response to a perceived local iron deficiency consequent to fibers metal adsorption, thus consequently limiting the establishment of an iron-induced oxidizing microenvironment, a fertile soil for neoplastic transformation. We propose that this mechanism may contribute to the observed protective effect exerted by the identified nonsynonymous substitution at position 568 of the Heph coding sequence against the development of asbestos-induced cancers.

3. Discussion

In the present study we provide new mechanistic understanding of how the Heph variant D568H, identified in a genetic susceptibility study as protective against the development of asbestos-dependent neoplasia, exerts its activity. This Heph variant can complex with Fpn1, the functional partner for iron egress, and possesses a full ferroxidase activity: both features shared with the WT form. By contrast, HephD568H has a longer half-life than the HephWT and is more enriched at the plasma membrane when coupled with the permease. Despite its enhanced surface recruitment, HephD568H is hampered in (iron-depleted) apo-Tfn binding, whose interaction with the WT ferroxidase represents a newly identified mechanism operating at the neuro-vascular unit to perceive brain iron needs [

53]. Heph in human lung is expressed by two resident mesenchymal cell populations, namely lung pericytes and fibroblasts: the former are in close functional contact with the microvascular endothelial cells, while the latter are positioned just beneath the alveolar epithelial cells or scattered in the interstitium. At these locations the expression of an Heph variant impaired in sensing local iron demand is expected to impede the establishment of a harmful iron-overload condition promoted by respiratory cells perceiving a false iron deficiency consequent to host metal sequestration by asbestos fibres. These data altogether would support the notion that alterations in iron sensing are determinant for a person's risk of developing asbestos-dependent neoplasms.

The ferroxidase Heph was initially identified as the mutated gene responsible for the phenotype of the sex-linked anaemia (sla) in mouse [

49]. In these mice intestinal enterocytes, while able to perform normal iron uptake, are impaired in efficient iron release into the blood, leading to duodenum iron accumulation and consequent anaemia. At the level of another physiological barrier, the one operating in the brain, Heph was shown to play a key role in iron supply. At the neuro-vascular unit, Heph expressed by all cell types composing it namely brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVEC), astrocytes, and pericytes [

60,

62], not only assists iron release in conjunction with Fpn1 but also assures that its release is adequate to satisfy precise local demands. Recently it has been clarified that this “on-demand” release is achieved through the interaction of the ferroxidase with iron-depleted Tfn, whose levels rise when iron-loaded Tfn is utilized. This regulatory mechanism has been characterized upon exploiting induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC), reprogrammed to become bona fide mature brain endothelial cells [

63], which differ from peripheral ones by their very constricted tight junctions, low permeability and high trans-endothelial resistance [

64,

65]. The contribution of the endothelial cells to iron transport across physiological barriers [

66] has been the subject of many studies due to several reasons: first, these cells are in direct contact with circulating iron and thus are determinant in its procurement; second, they can act as iron storage cell type; third, a large body of work has been devoted to this type of cells, under normal and pathological conditions, leading to their extensive phenotypic characterization.

The contribution of pericytes in iron handling at the BBB has been, instead, poorly investigated, even though these cells provide structural and nutritional support to endothelial cells to enhance the barrier function of the BBB [

67,

68]. Pericytes are also structurally and functionally connected to endothelial cells: this organization allows a single pericyte to integrate and coordinate nearby cell responses. These mural cells were shown to express Heph together with CP, both the soluble and the GPI-anchored forms, just like astrocytes, but how their activity is coordinated with that of the endothelial cells is mostly unknown [

60].

Our initial study addressing the possible contribution of the ferroxidase Heph to lung tumour progression [

54] demonstrated that its expression is associated with the lung vasculature and cellular elements characterized by the typical elongated spindle-shaped morphology of fibroblasts. This initial characterization performed on lung cancer specimens did not allow to thoroughly characterize the cell types actively involved in Heph expression and, more importantly, to address its distribution in a healthy context. To bridge this gap of knowledge we proceeded by evaluating Heph expression on primary human cell lines representative of healthy lung and pleural districts. In particular, we tested alveolar type 1-like TT1 cells, which are involved in gas exchange and therefore share the basement membrane (BM) with the pulmonary capillary endothelium; microvascular endothelial cells, which are integral part of the alveoli–capillary barrier; lung pericytes, fundamental for maintaining the health and function of the pulmonary vasculature and therefore critical for optimal gas exchange [

69]; lung fibroblasts, which provide extracellular matrix but also paracrine cues to developing epithelium and endothelium; and finally primary human pleural mesothelial cells.

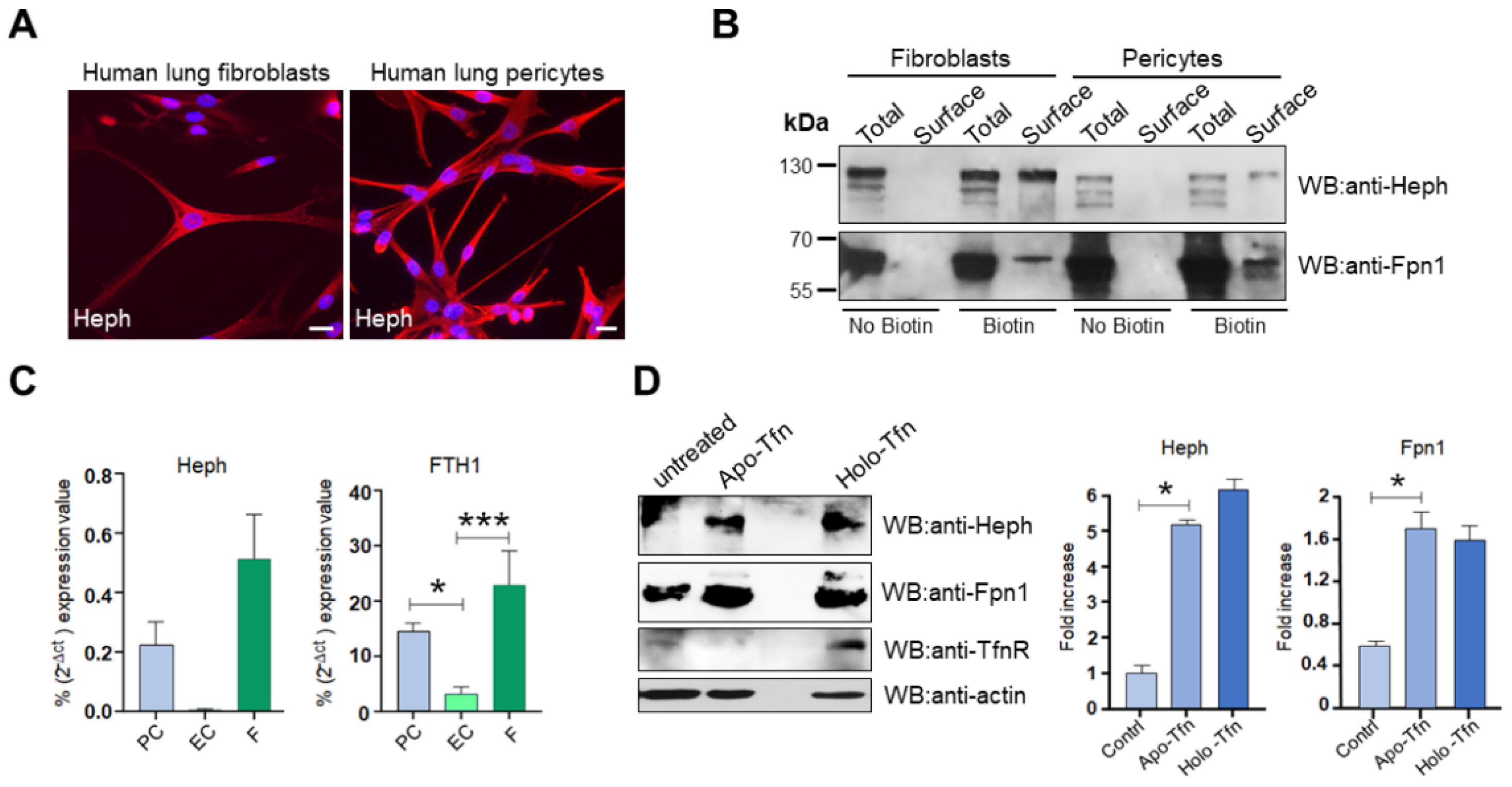

Surface biotinylation experiments unveiled that at the pulmonary barrier Heph is solely expressed by lung pericytes and fibroblasts, while pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells were negative for Heph (

Figure 3BS, left panel) and CP expression. This was further confirmed by qRT-PCR (

Figure 3BS, right panel). We also tested endothelial cells derived from human umbilical veins (Huvec), a physiologically relevant model system for vascular biology research. Also in this case, these cells resulted unable to express Heph (

Figure 3CS, left panel) while relying on CP as ferroxidase for iron excretion (

Figure 3CS, right panel). These observations are indicative that iron handling at the vascular units of different organs must be tailored to sustain context-specific needs. Brain and lung are characterized by profound differences in iron requirement. The brain is one of the most energy-demanding organs in the body, whose iron demand does not only support basic cellular processes such as energy production and DNA repair but is also fundamental for neuronal specific functions like the synthesis and catabolism of neurotransmitters and axon myelination [

70,

71]. Lungs, instead, are extremely sensitive to metal-induced oxidative stress due to their partial pressure of oxygen, which is the highest in the body [

72]. Moreover, excessive iron bioavailability could favour lung infections [

73]. Therefore, as a protective strategy to prevent redox damage and potential microbes’ proliferation, lung epithelial cells maintain intracellular iron concentration just sufficient to sustain their metabolic demand [

74]. In this context lung pericytes, shown to express Heph/Fpn1 complexes at the plasma membrane, could represent the prominent cell type exerting control over iron mobilization upon local request instead of the vascular endothelial cells, as emerged at the BBB. This lung-specific role is further supported by the fact that these mural cells express more ferritin than lung endothelial cells, as judged by qRT-PCR, indicating a better iron storage capacity. It should be emphasised that an increase in iron demand is a rather exceptional event in the pulmonary context which operates to avoid any possible risk of iron-dependent oxidative damage. Inhaled asbestos fibres that reach the low respiratory tract and the alveoli represent that unusual occurrence which dramatically perturbs this delicate system in exposed cells, mostly professional phagocytes like alveolar macrophages. Host metal sequestration by fibre surface makes the cell perceive a functional iron deficiency. This event provokes a homeostatic response aimed at re-establishing the appropriate cellular iron concentration. It is reasonable to suppose that the resulting increase in local iron demand will cause an increased utilisation of iron-loaded Tfn and a concomitant increase in apo-Tfn concentration (

Figure 8). This iron demand is expected to be intercepted by nearby pericytes which are equipped to appropriately sense it and also to respond to it by enhancing Heph and Fpn1 expression, as it emerged from our experiments. In case of a prolonged iron request, as it occurs upon the deposition of bio-persistent asbestos fibers, the prompt response to satisfy it is likely to promote a local iron overload. But if the iron supply mechanism is not responding, such dangerous condition will be far more difficult to establish. Since the identified HephD568H variant is protective against asbestos-dependent carcinogenesis, we hypothesized that it could exert its activity by hampering iron release in response to a persistent request. This could be achieved by several mechanisms ranging from impairment in Heph catalytic activity to alteration in Heph ability to associate with Fpn1 at the plasma membrane or to sense iron needs upon interacting with apo-Tfn.

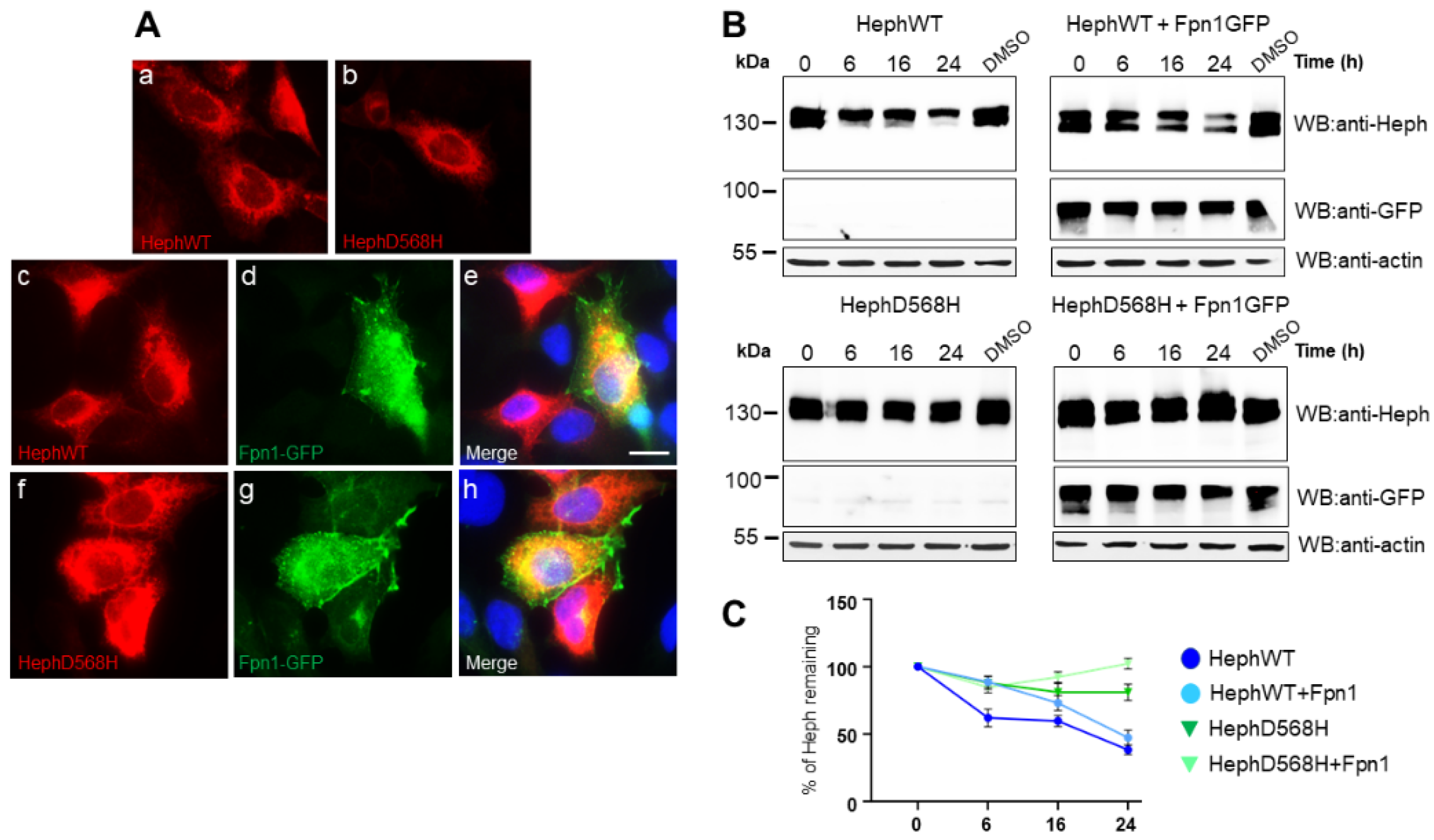

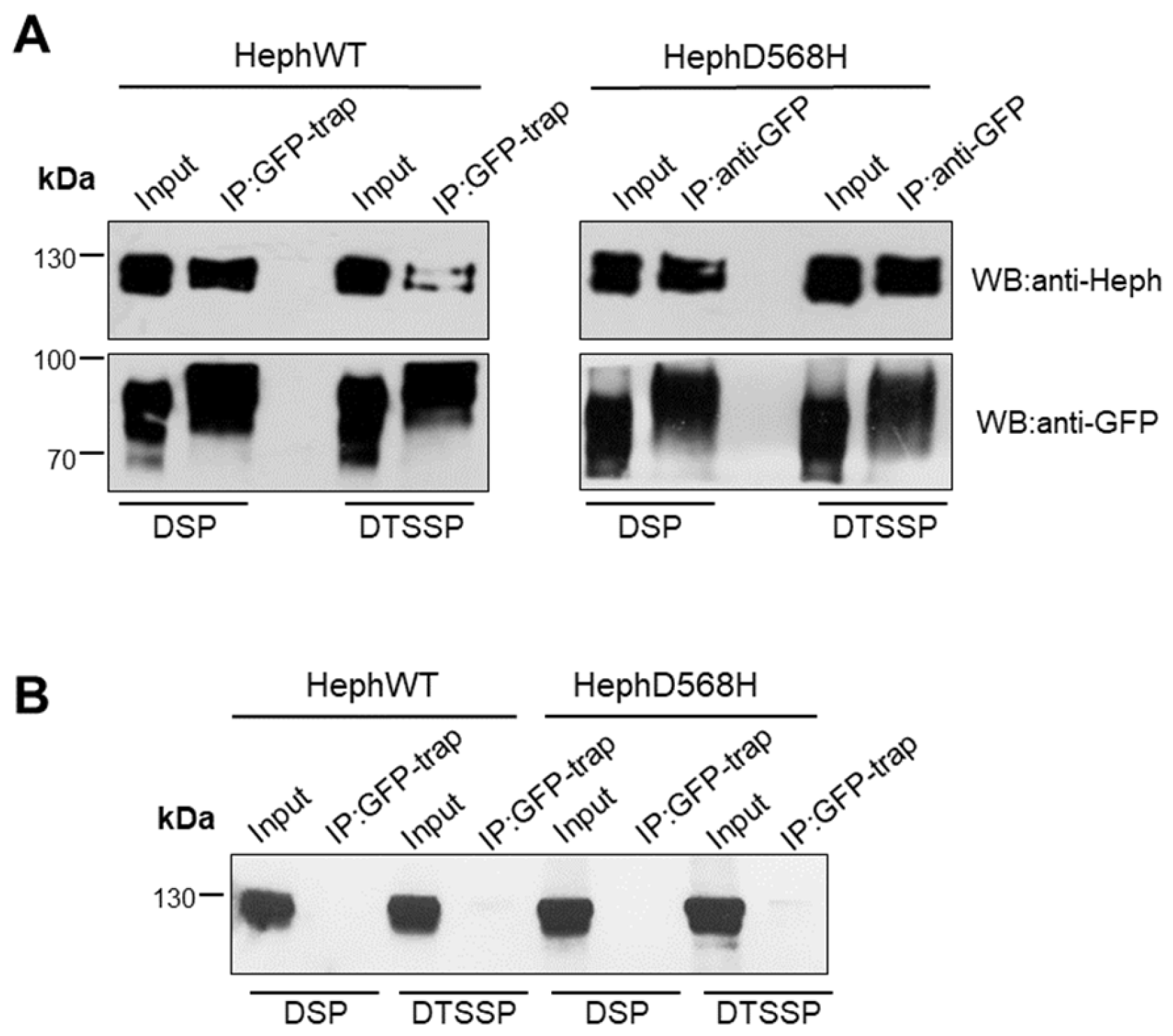

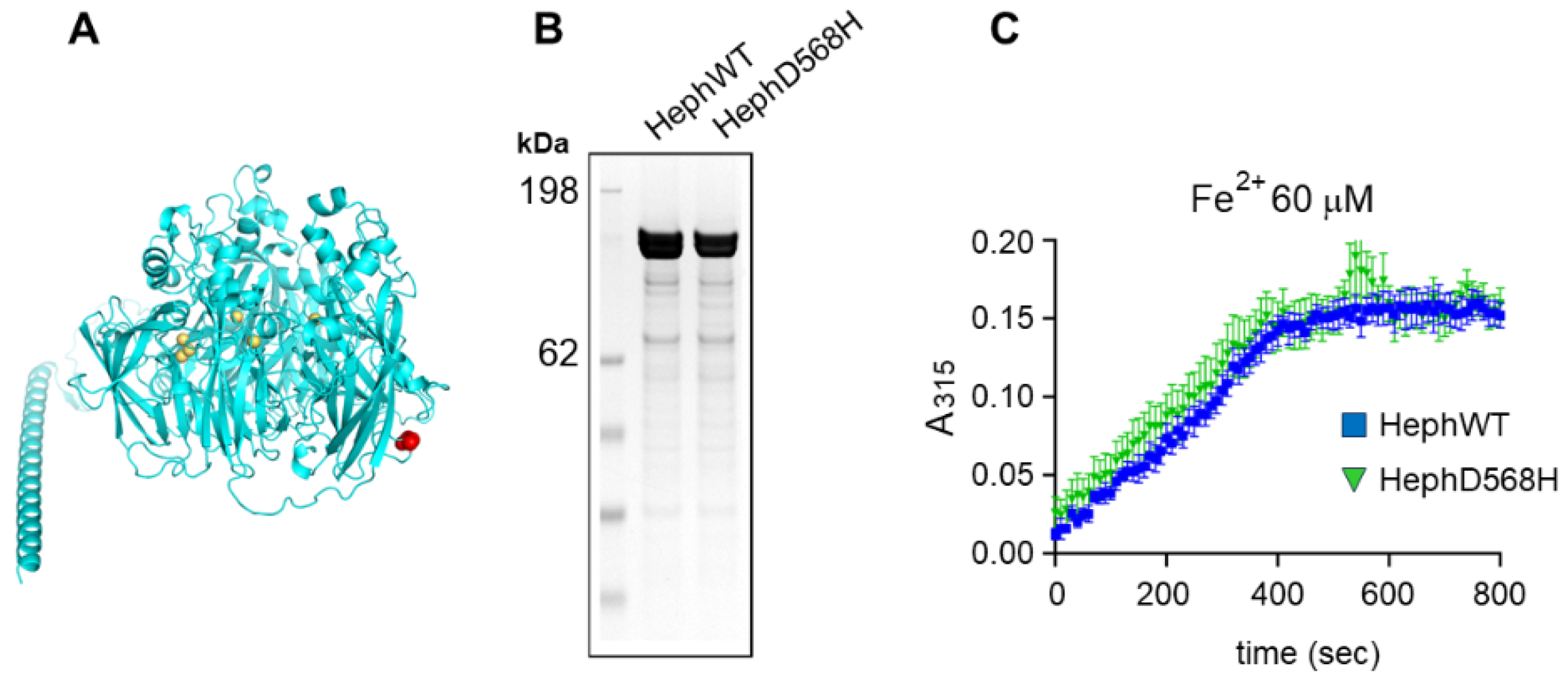

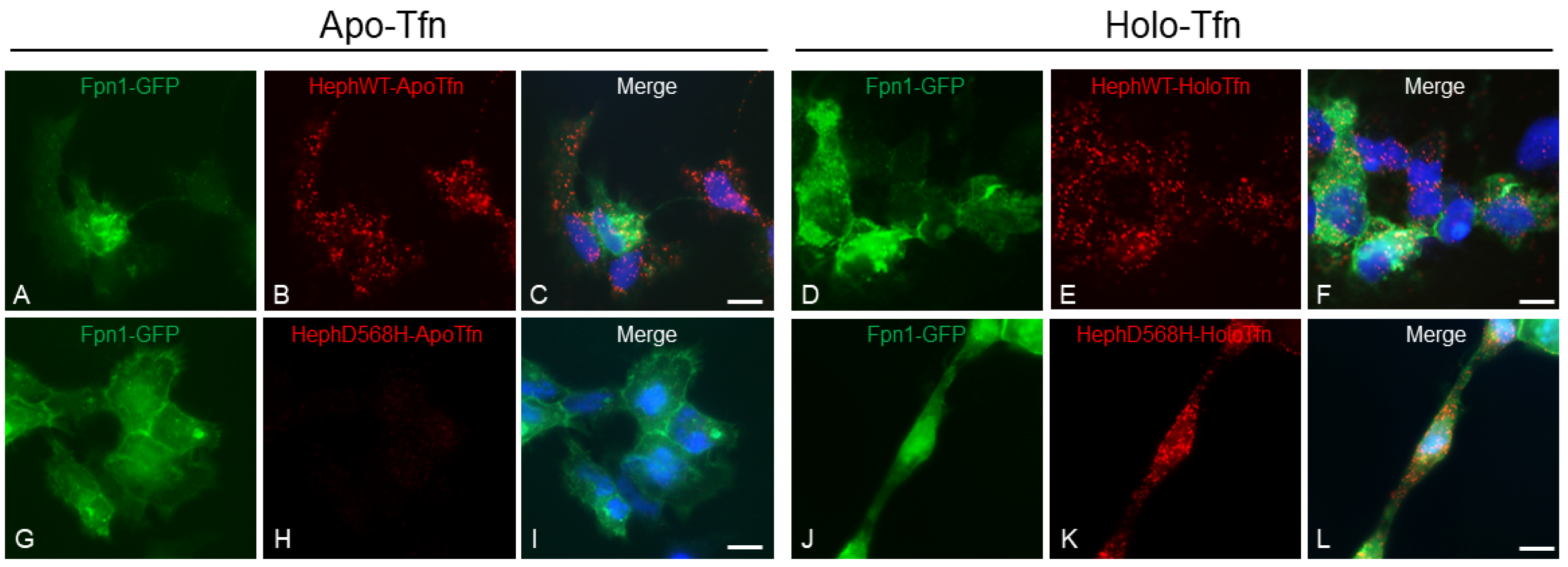

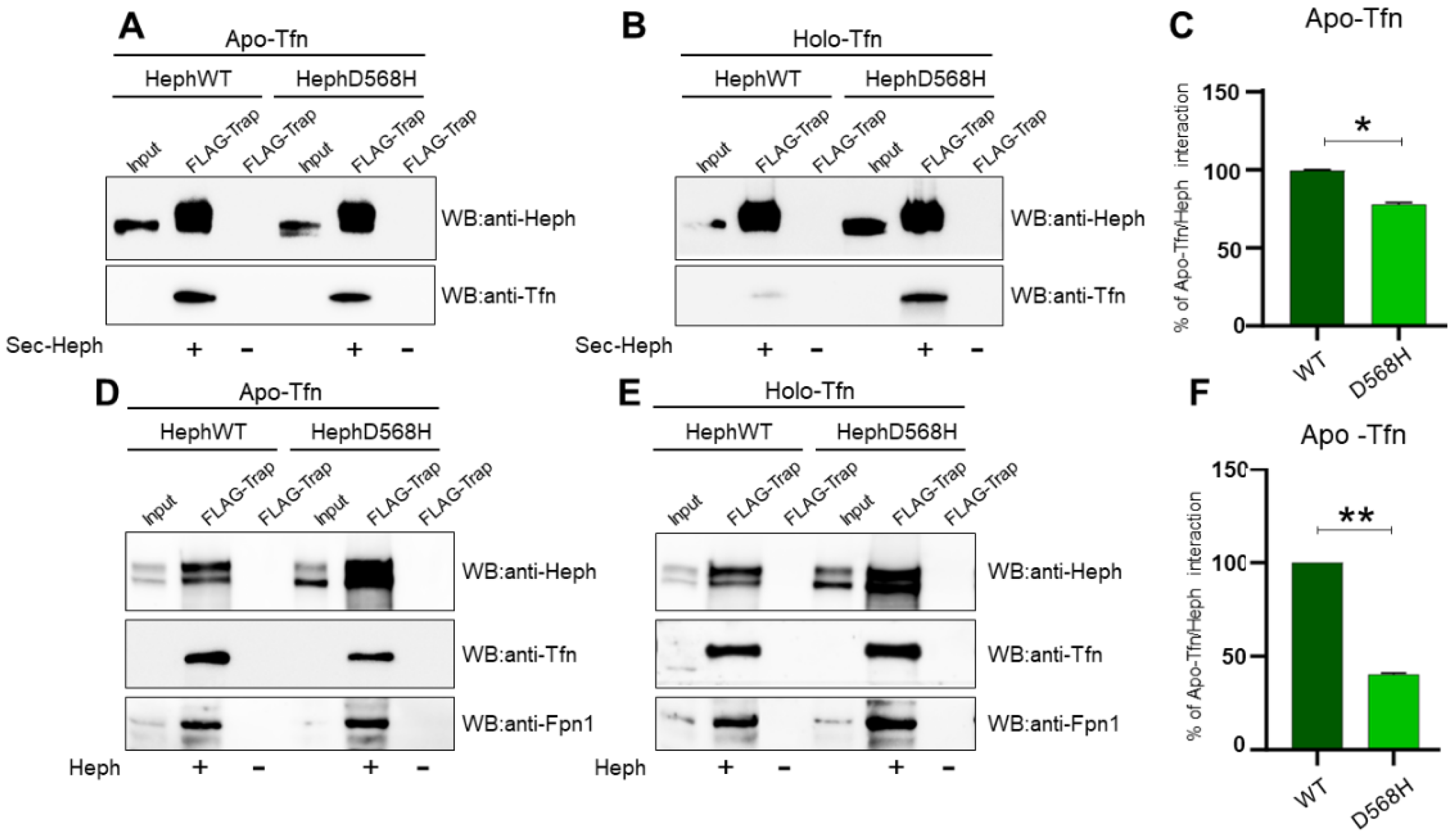

From

in vitro characterization of the ferroxidase activity, it emerged that the kinetic parameters were not significantly different between HephWT and D568H, in contrast with our initial in silico prediction. This finding may not be so surprising because the D568 residue is distant from the Cu binding sites. D568 is predicted to be located on a surface exposed loop; replacement of Asp with His removes a negative charge and our results point to a role for this residue in the stability of Heph and/or in the ability of the protein to interact with molecular partners. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments performed upon having selectively cross-linked Heph/Fpn1 complexes at the plasma membrane unveiled that HephD568H/Fpn1 were more enriched compared to the HephWT/Fpn1 complex. Even though the mechanisms involved in controlling intracellular Heph association to Fpn1, the endomembrane compartments involved and its resulting targeting to the plasma membrane have been poorly clarified, our findings point the attention to Heph stability as an important factor. In fact, we observed that HephWT, which is characterized by a shorter half-life compared to HephD568H, is poorly delivered to the plasma membrane. HephD568H, intrinsically more stable than the WT form regardless of Fpn1 expression, appears to be more efficiently targeted at the cell surface. Then we tested the ability of apo- and holo-Tfn to bind Heph. Upon expression of Heph in HEK293T cells and immunoprecipitation we observed that apo-Tfn was poorly recruited by HephD568H as compared to the WT form, impairment further attested by PLA. This phenotype was more evident in case of HephD568H expressed in a cellular context than the corresponding secreted extracellular domain which appeared to be able to recruit also iron-loaded Tfn in the absence of Fpn1. We hypothesized that the secreted HephD568H domain, endowed with a greater degree of freedom, would interact with holo-Tfn via protein-interaction domains that are not accessible when the ferroxidase is membrane-bound. Alternatively, these data may indicate that HephD568H, upon iron oxidation and loading onto Tfn, does not efficiently release it. In this way the ferroxidase could act as inefficient sensor not only because it is impaired in apo-Tfn capture but also because it keeps Tfn sequestered. This behaviour was better underscored when dealing with the isolated extracellular domain of Heph since we tested the system in the absence of Fpn1, the physiologically relevant binder of holo-Tfn. The molecular dissection of all steps involved in iron transfer from Heph/Fpn1 complex to Tfn cannot exclude a deep structural characterization of the domains involved. Based on our findings we can surely affirm that HephD568H results hampered in apo-Tfn recruitment, a condition that would render the ferroxidase poorly responsive to satisfy iron request (

Figure 8).

Regarding the contribution of lung fibroblasts to the phenotype, the fact that they express Heph and Fpn1 makes them potentially able to respond similarly to lung pericytes, from which they could also derive [

75]. This capacity has been described in gastric cancer associated fibroblasts where the up-regulation of Heph and Fpn1 is exploited to induce iron overload dependent ferroptosis in NK cells, thus hampering their anti-tumour immune response [

76]. Based on qRT-PCR, fibroblasts can be considered an iron storage cell type as lung pericytes, being able to express more ferritin than pericytes and lung endothelial cells. Pericytes and resident fibroblasts are busily sensing and responding, through diverse mechanisms, to changes in lung health and function [

77]. A better understanding of the relative contribution given by pericytes and fibroblasts to regulated iron release in response to local demands still deserves further dedicated studies.

Another puzzling aspect refers to how lung pericytes and fibroblasts acquire iron, since they are not in direct contact with the bloodstream. At least three possibilities can be envisaged. In the first scenario the iron absorbed by the endothelium is exported through Fpn1, shown to be present on the abluminal side of the endothelial membrane [

51]. Based on our findings, lung endothelial cells lack ferroxidase activity that could be supplied by nearby pericytes/fibroblasts to promote iron oxidation and Tfn loading. Another way of iron supply could be the delivery of iron bound to Tfn and ferritin packaged into exosomes, a modality recently described in the context of the BBB [

78]. It is interesting to note that a ferroxidase activity was found associated with exosomes isolated from mouse exposed to asbestos fibres and identified as part of a unique protein signature [

79]. Finally, iron could directly shuttle from endothelial cell to pericyte through gap junctions, membranous channels that directly join the cytoplasms of both cell types. This kind of contact, together with adhesion plaques and peg-socket junctions, was shown to allow pericytes to come in close contact with endothelial cells, providing a biochemical cross-talk necessary for the formation and maintenance of the BBB.

In summary, the novelty of our study relies upon having attributed to lung pericytes and fibroblasts a key role in sensing local iron request. We also extended the paradigm uncovered at the BBB to the pulmonary barrier, even though highlighting organ-specific peculiarities. In this framework, the protective activity exerted by the identified Heph genetic polymorphisms could be reliably interpreted. These findings altogether not only have advanced our understanding of genetic contributions to asbestos-dependent cancers, but have also underscored the importance of resident lung mesenchymal populations as targets for developing novel preventive approaches in asbestos-exposed individuals.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plasmids and Mutagenesis

The pCMV6 plasmid containing the entire sequence of the human HEPH ORF (NM_138737) with a C-terminal MYC-DDK tag [myc-DDK-HEPH1, hereafter WT (wild type)-HEPH] was obtained from Origene (RC215550, Origene Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA). Full-length HephWT with a C-terminal FLAG-tag and the point-mutant D568H, were generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and cloned into pcDNA3. A truncated soluble version of Heph comprising the extracellular enzymatically active domain (residues 1-1107) and lacking the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains was also produced and cloned into pCMV-Tag4b vector. For recombinant expression and purification, human HephWT and D568H full-length coding sequences were cloned in pOPINEneo-3C-TGP-His vector (MPL) by ligation independent cloning (ClonExpress®IIOne-Step Cloning kit). All PCR amplified products were fully sequenced to exclude the possibility of second site mutations. The plasmid for expression of human Fpn1 tagged with GFP is described in Bonaccorsi di Patti and colleagues (2014).

4.2. Chemicals and Antibodies

Apo-Tfn, holo-Tfn and cycloheximide (CHX) were purchased from Sigma (#T1147, #T4132, #C1988, respectively).

The following primary antibodies were used in western blot analysis: mouse monoclonal anti-Heph (1:1,000; #sc-365365, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), monoclonal anti-Fpn1 clone 31A5 kindly provided by Amgen (USA, 1:5,000), polyclonal anti-Transferrin (Tfn) antibody (1:1,000; #17435-1-AP, Proteintech), monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (1:1000, #MA5-15256, Invitrogen) and anti-beta actin HRP conjugated monoclonal antibody (1:5000; #sc-47778 HRP, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

4.3. Cell Culture and Transfections

TT1 cells, an immortal alveolar type 1(AT1)-like cell line [

55] were cultured in Hybridoma Serum Free Medium (#12045-084, Gibco) supplemented with 10% new-born calf serum (NCS, #N4762-500ML, Sigma) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin–glutamine (PSG).

Human mesothelial cells (MeT-5A) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, CRL-9444TM, USA). They were cultured in Medium 199 (M199, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 3.3 nM epidermal growth factor (EGF) 400 nM hydrocortisone. Human mesothelial primary cells (HMC, #36223-01, Celprogen) were grown in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml). Human Pulmonary Microvascular Endothelial Cells (HPMEC) were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories (3000-SC) and cultured in complete Endothelial Cell Medium (1001-SC) on bovine plasma fibronectin-coated culture vessel (2 μg/cm2, #8248-SC). Immortalized human lung pericytes [

56] were cultured in human Pericyte Medium (ScienCell) on gelatine (0.2%) pre-coated culture vessel. Primary human pulmonary fibroblasts were purchased from PromoCell (#C-12360) and cultured in Fibroblast Growth Medium 2 (#C-23020).

HEK293T cells were cultured at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml). They were transiently transfected with various plasmid constructs using the calcium phosphate method and collected 48h after transfection.

4.4. Recombinant Protein Expression and Purification

Expi293F cultures (2.5 x 106 cells/ml) were transfected by gently adding a transfection mixture consisting of plasmid DNA (1 µg/ml of culture), and PEI Max 40K diluted in Opti MEM medium (Gibco). After 8-10 h cultures were supplemented with 5 mM valproic acid, 6.5 mM sodium propionate, 0.9% (w/v) glucose, and 50 µM CuSO4 and placed in shaking humidified 8% CO2 incubator at 30 °C and 80 rpm. Cells were harvested after 72 h by centrifugation and washed with cold PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in base buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 0.5mM TCEP) supplemented with protease inhibitors (complete Roche) and disrupted using a cell disruptor (CF 2 model, Constant systems). Cell membranes were obtained by ultracentrifugation at 195.000g. Membrane proteins were solubilized in base buffer containing 1% (w/v) N-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM, Anatrace), 0.1% (w/v) cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS, Anatrace), for 1 h at 4°C and then ultracentrifuged again. Recombinant Heph was purified from the resulting supernatant with Co2+ charged-TALON resin (Takara Bio). After extensive washing, the protein was eluted with base buffer containing 300 mM imidazole and 0.03% DDM/0.003% CHS. Imidazole was removed using a desalting column (CentriPure100-Z25M, Emp Biotech), and the protein was incubated overnight with HRV 3C protease to remove the tag. After incubation with TALON resin, flowthrough containing cleaved protein was collected, concentrated, and further purified by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex G200 increase column, Cytiva). Protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE and concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm (ε280 200000 M -1 cm -1).

4.5. Ferroxidase Activity Assay

Heph ferroxidase activity assays were performed at 25°C in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 0.02% DDM and 0.002% CHS. Upon addition of 60-300 µM FeSO4 to 0.3 µM Heph, Fe2+ oxidation was measured at 315 nm using UV-Vis microplate spectrophotometer (CLARIOstar plus, BMG labtech). Corrections for iron auto-oxidation was performed by subtraction of traces obtained in the absence of enzyme. All measurements in triplicate to generate the error bars.

4.6. Immunocytochemistry and Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA)

Human lung pericytes and HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmid DNAs (24h after transfection) were fixed with 3% PFA for 20 min at room temperature (RT). Permeabilization, quenching and blocking were performed by incubating the cells in 1% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 50 mM glycine in PBS, for 30 min at RT. Antibody staining was performed by standard procedures. GFP was visualised by autofluorescence. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, 1:1000) for 5 min. Coverslips were mounted with Fluorescence Mounting Medium (Dako).

For PLA cells were seeded onto glass coverslips and transfected with the indicated plasmid DNAs. One day after transfection the media was replaced with DMEM containing no FBS in order to remove exogenous Tfn. The next day cells were incubated with 0.25 µM apo-Tfn and holo-Tfn solutions for 30 min and then washed to proceed with PLA following the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich Duolink, #DUO92102). All images were acquired using Leica DM3000 microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and a Leica DFC320 digital camera.

4.7. Surface Biotinylation, Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis

Biotinylation assay was exploited to examine the expression and surface targeting of endogenous Heph in all human primary cell lines tested. Briefly, cells grown on 10 cm dishes were incubated with 0.5 mg/ml EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce) in PBS at 4°C for 30 min. To quench the reaction, cells were washed three times with cold PBS containing 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.4. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1,000g for 10 min and then lysed in RIPA buffer (25mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0,5% sodium deoxycholate, 0,1% SDS, 10% glycerol) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The collected lysates were then incubated with Neutravidin Agarose Resin (Pierce, #29200) for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were then washed three times with lysis buffer and eluted with SDS loading buffer.

In co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments transfected HEK293T cells grown in 10 cm Petri dishes were treated with two different crosslinkers before being harvested as previously described. The cross-linker Lomant's Reagent (DSP, Pierce) is a cell-permeable chemical crosslinker that reacts with amino groups such as those of lysine residues and it is able to crosslink Heph/Fpn1 complexes localized at different membrane compartments. The membrane-impermeant, Dithiobis-(sulfosuccinimidylpropionate) (DTSSP, Pierce) was used to evaluate the fraction of Heph/Fpn1 interaction selectively occurring at the plasma membrane. DSP was dissolved in DMSO at 10 mM, then mixed in PBS Plus to a final concentration of 0.5 mM; DTSSP was directly dissolved in the appropriate volume of PBS at the final concentration of 1.5mM. The DSP treatment was performed by incubating transfected cells for 30 min at 4oC; DTSSP treatment was performed upon 2 h incubation at 4oC. Quenching was done by washing the cells with 200 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7,6 solution 3 times, 5 min each. Cells were then harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer as previously described. 1/10 of the whole cell lysate volume was mixed with 2X Laemmli sample buffer and used as the reference input. The GFP-trap or DYKDDDDK Fab-Trap resin (Chromotech, #gta and #ffa respectively) were equilibrated in RIPA buffer and incubated with cell lysates in rotation end-over-end for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were then washed 3 times in lysis buffer and proteins were eluted by adding 2X Laemmli buffer with DTT. Samples derived from surface biotinylation and co-IP were fractioned by 8% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Primary antibodies diluted in 5% skimmed milk in TBST (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Tween 20) were incubated over-night and revealed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma) followed by ECL (Advansta).

4.8. Gene Expression Analysis

RNA was extracted using the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen. #12183018A) according to the supplier’s instructions. The RNA concentration and purity were determined spectrophotometrically with a 260/280 ratio above 1.8. 1µg of RNA was reverse transcripted to cDNA using SuperMix kit (Bioline) and qPCR was carried out on a Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett, Qiagen, Milan, Italy) using SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Milan, Italy). Each sample was analysed in triplicates, and non-reverse-transcribed RNA and water served as negative controls. The PCR conditions were 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. All primers (

Table S1) were designed using Primer3Plus software according to NCBI, Ensembl, and FANTOM-CAT sequence databases. For relative quantification, the GAPDH was used as internal standard reference. All experiments were performed at least in duplicate technical replicates. Analyses were done using CT method.

4.9. Statistics

Statistical analyses co-IP and qRT-PCR were conducted using GraphPad Prism software. Differences between diverse groups were evaluated using one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by appropriate post hoc tests for multiple comparisons. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were expressed as ± Standard Error of the mean (SEM). All experiments were performed in at least triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

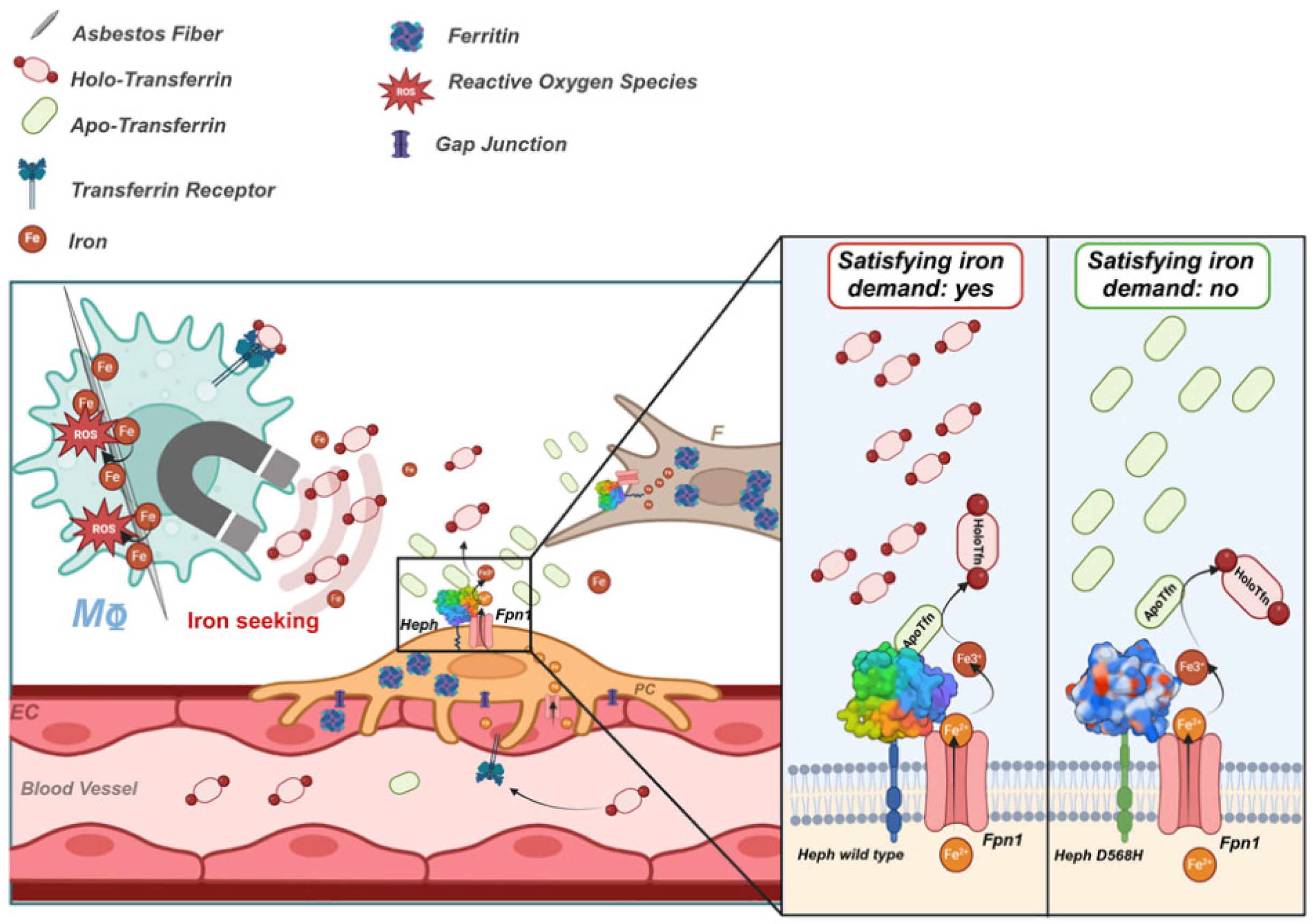

Figure 1.

Schema summarizing the mechanism of asbestos fibers induced iron overload and consequent oxidative damage. Asbestos fibers reaching the alveoli and the pleural district is intercepted by alveolar macrophages. Once phagocytosed, asbestos fibers start to adsorb the host metal, making the cell to develop an iron seeking phenotype. EC=Endothelial cell, F=Human lung Fibroblast, PC=pericyte, TT1=alveolar type 1 cell, TT2=alveolar type 2 cell, Mφ=macrophage, MC=mesothelial cell, ROS=radical oxygen species, apo-Tfn=iron free transferrin, holo-Tfn=iron bound transferrin, TfnR=Transferrin Receptor, AF= asbestos fiber. Created in BioRender. Longo, F. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/r43w726.

Figure 1.

Schema summarizing the mechanism of asbestos fibers induced iron overload and consequent oxidative damage. Asbestos fibers reaching the alveoli and the pleural district is intercepted by alveolar macrophages. Once phagocytosed, asbestos fibers start to adsorb the host metal, making the cell to develop an iron seeking phenotype. EC=Endothelial cell, F=Human lung Fibroblast, PC=pericyte, TT1=alveolar type 1 cell, TT2=alveolar type 2 cell, Mφ=macrophage, MC=mesothelial cell, ROS=radical oxygen species, apo-Tfn=iron free transferrin, holo-Tfn=iron bound transferrin, TfnR=Transferrin Receptor, AF= asbestos fiber. Created in BioRender. Longo, F. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/r43w726.

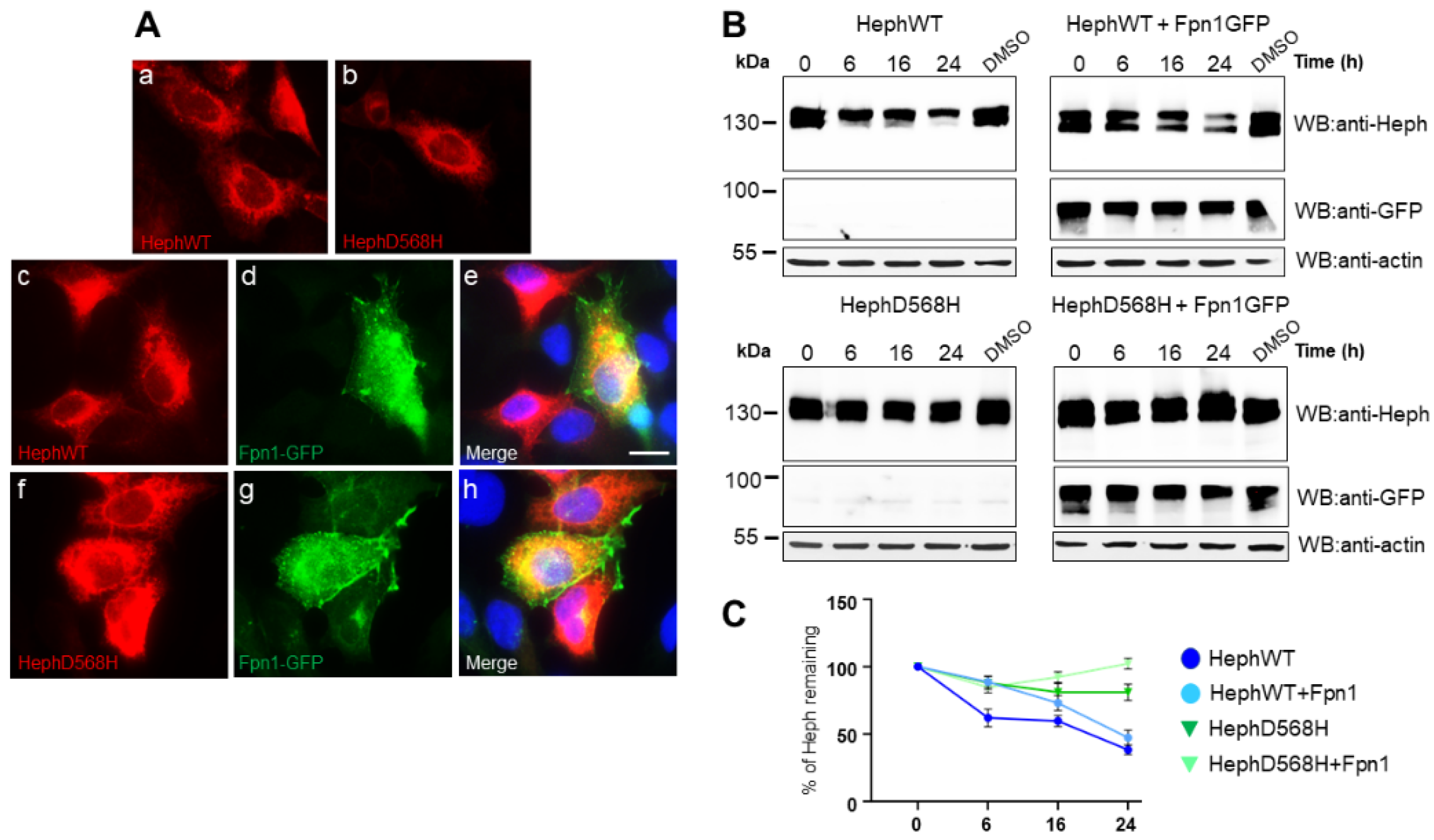

Figure 2.

HephWT and D568H distribute similarly in HEK283T cells but are characterized by different half-life. A) Representative images of HEK293T cells transfected with HephWT and D568H either alone (panel a and b) or together with Fpn1-GFP (HephWT, panels c-e; HephD568H, panels f-h). Heph distribution was analysed using a monoclonal anti-Heph antibody followed by Alexa595-conjugated secondary antibody while Fpn1-GFP was detected by the intrinsic green fluorescence of GFP. Scale bar= 10 µm; B) HEK293T cells were transfected with 100ng of HephWT or HephD568H either alone or in co-transfection with 100ng Fpn1-GFP. 24h post-transfection protein synthesis was blocked with cycloheximide (CHX) and cells were harvested at the indicated time points. The amount of Heph protein remaining was analyzed by western blot and densitometric scanning. Anti-actin was used as loading control. C) The results of three independent experiments are summarized in the graph, where the amount of HephWT or HephD568H proteins at time 0 was set as 100%. Standard deviations are indicated.

Figure 2.

HephWT and D568H distribute similarly in HEK283T cells but are characterized by different half-life. A) Representative images of HEK293T cells transfected with HephWT and D568H either alone (panel a and b) or together with Fpn1-GFP (HephWT, panels c-e; HephD568H, panels f-h). Heph distribution was analysed using a monoclonal anti-Heph antibody followed by Alexa595-conjugated secondary antibody while Fpn1-GFP was detected by the intrinsic green fluorescence of GFP. Scale bar= 10 µm; B) HEK293T cells were transfected with 100ng of HephWT or HephD568H either alone or in co-transfection with 100ng Fpn1-GFP. 24h post-transfection protein synthesis was blocked with cycloheximide (CHX) and cells were harvested at the indicated time points. The amount of Heph protein remaining was analyzed by western blot and densitometric scanning. Anti-actin was used as loading control. C) The results of three independent experiments are summarized in the graph, where the amount of HephWT or HephD568H proteins at time 0 was set as 100%. Standard deviations are indicated.

Figure 3.

HephD568H/Fpn1 complexes are enriched at the plasma membrane. A) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with either HephWT or HephD568H together with Fpn1-GFP. 24h after transfection, cells were cross-linked as indicated. Cell lysates were incubated with GFP-trap agarose beads. Immunoprecipitate (IP) and 10% of cell lysate (input) were processed for immunoblotting. Immunoprecipitation of Fpn1-GFP shows that both HephWT and HephD568H are pulled down along with the Fpn1 complex upon DSP treatment, while DTSSP surface cross-linking indicates that HephD568H/Fpn1 complexes are enriched at the surface as compared to HephWT. Western blots were performed with anti-GFP monoclonal and anti-Heph monoclonal antibodies (n=4). B) HEK293T cells were only transfected with HephWT or HephD568H alone and processed as described in (A). In the absence of Fpn1-GFP co-transfection both over-expressed HephWT and HephD568H are not aspecifically pulled-down by GFP-Trap agarose (n=4).

Figure 3.

HephD568H/Fpn1 complexes are enriched at the plasma membrane. A) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with either HephWT or HephD568H together with Fpn1-GFP. 24h after transfection, cells were cross-linked as indicated. Cell lysates were incubated with GFP-trap agarose beads. Immunoprecipitate (IP) and 10% of cell lysate (input) were processed for immunoblotting. Immunoprecipitation of Fpn1-GFP shows that both HephWT and HephD568H are pulled down along with the Fpn1 complex upon DSP treatment, while DTSSP surface cross-linking indicates that HephD568H/Fpn1 complexes are enriched at the surface as compared to HephWT. Western blots were performed with anti-GFP monoclonal and anti-Heph monoclonal antibodies (n=4). B) HEK293T cells were only transfected with HephWT or HephD568H alone and processed as described in (A). In the absence of Fpn1-GFP co-transfection both over-expressed HephWT and HephD568H are not aspecifically pulled-down by GFP-Trap agarose (n=4).

Figure 4.

The ferroxidase activity is not affected in HephD568H. A) Alphafold structural model of human Heph, residue D568 is colored in red and the Cu atoms are in orange. B) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified human Heph WT and HephD568H. The gel was stained with Coomassie Blue. C) Time-course of ferroxidase activity measured at 315 nm with 60 µM Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 and 0,3 µM recombinant protein.

Figure 4.

The ferroxidase activity is not affected in HephD568H. A) Alphafold structural model of human Heph, residue D568 is colored in red and the Cu atoms are in orange. B) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified human Heph WT and HephD568H. The gel was stained with Coomassie Blue. C) Time-course of ferroxidase activity measured at 315 nm with 60 µM Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 and 0,3 µM recombinant protein.

Figure 5.

HephD568H variant is hampered in apo-Tfn recruitment. Duolink proximity ligation assay (PLA) was exploited for detecting apo-Tfn and holo-Tfn interaction with HephWT and HephD568H. HEK293T cells co-transfected with Fpn1-GFP and HephWT or HephD568H were treated with 0,25 μM apo-Tfn or holo-Tfn for 30 min prior to fixation. PLA detects HephWT ability to interact with apo-Tfn while HephD568H is strongly impaired. PLA signal detected upon holo-Tfn incubation is attributed to Fpn1 vicinity to Heph. Nuclei were stained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenyl indole (DAPI) in blue. Scale bar: 10 µm. Representative images are shown from three independent experiments.

Figure 5.

HephD568H variant is hampered in apo-Tfn recruitment. Duolink proximity ligation assay (PLA) was exploited for detecting apo-Tfn and holo-Tfn interaction with HephWT and HephD568H. HEK293T cells co-transfected with Fpn1-GFP and HephWT or HephD568H were treated with 0,25 μM apo-Tfn or holo-Tfn for 30 min prior to fixation. PLA detects HephWT ability to interact with apo-Tfn while HephD568H is strongly impaired. PLA signal detected upon holo-Tfn incubation is attributed to Fpn1 vicinity to Heph. Nuclei were stained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenyl indole (DAPI) in blue. Scale bar: 10 µm. Representative images are shown from three independent experiments.

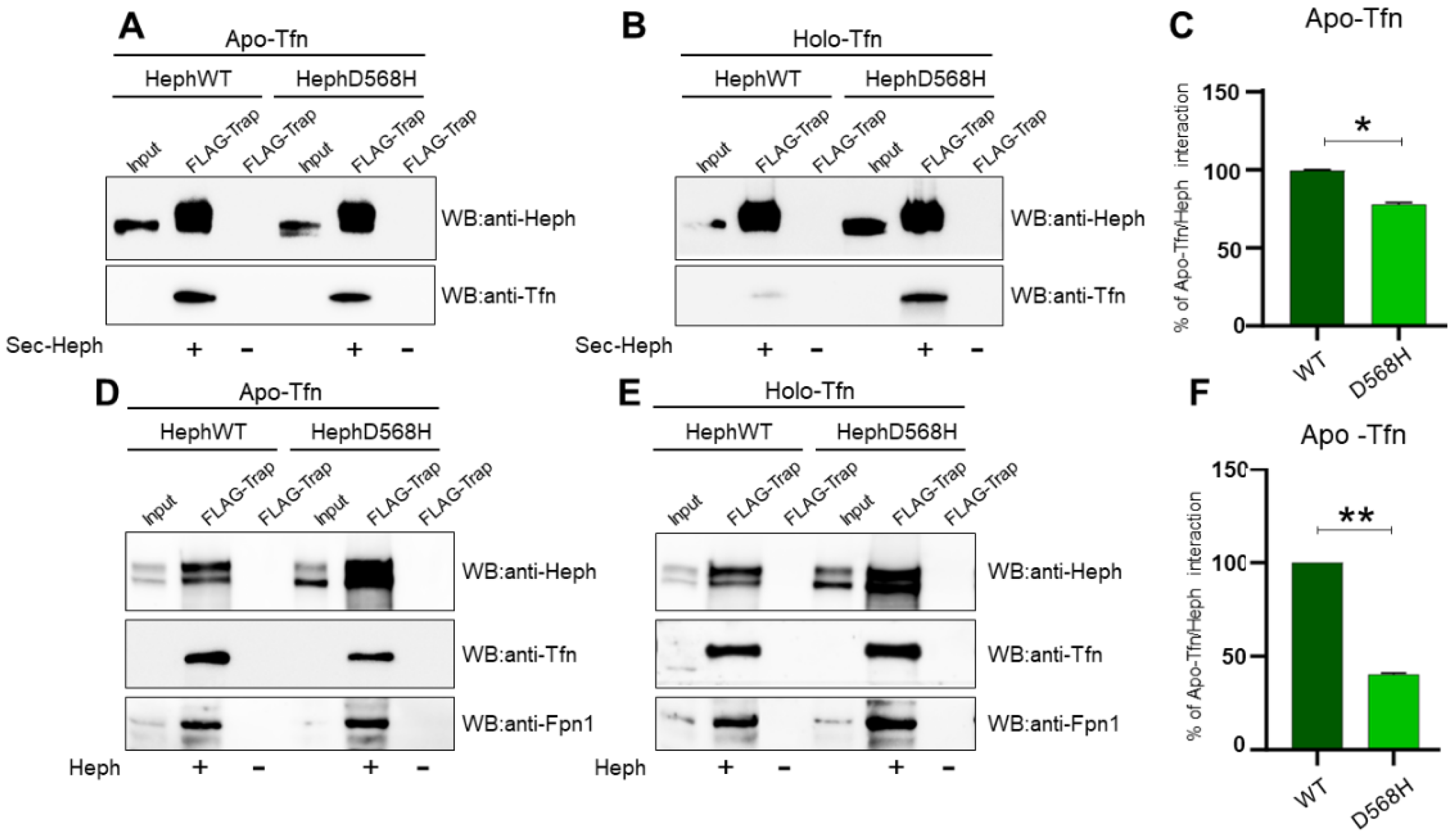

Figure 6.

Apo-Tfn is poorly recruited by HephD568H as compared to HephWT. A-B) Representative IP of FLAG epitopes from medium of HEK293T cells expressing the secreted extracellular domain of HephWT and HephD568H. Each affinity resin has been splitted to be further incubated with apo-Tfn and holo-Tfn. Nitrocellulose membranes were probed with anti-Heph and anti-Tfn antibodies. C) The histogram on the right shows the relative amount of apo-Tfn co-precipitated by HephWT and HephD568H (n=4, data are expressed as mean ± SEM; * p < 0,05, and **p < 0,01). D-E) Representative co-IP of FLAG epitopes of HEK293T cells transfected with HephWT and D568H and undergone DSP cross-liking before lysis. The immunoprecipitated Heph/Fpn1 complexes were splitted to be further incubated with apo-Tfn or holo-Tfn. F) The histogram on the right shows the relative amount of apo-Tfn co-precipitated by HephWT and HephD568H (n=5, data are expressed as mean ± SEM; * p < 0,05, and **p < 0,01). The amount of apo-Tfn co-precipitated by HephWT and HephD568H, either secreted or inserted into the plasma membrane, was quantified by densitometric scanning of western blot. The amount of apo-Tfn interacting with HephWT was set as 100% interaction.

Figure 6.

Apo-Tfn is poorly recruited by HephD568H as compared to HephWT. A-B) Representative IP of FLAG epitopes from medium of HEK293T cells expressing the secreted extracellular domain of HephWT and HephD568H. Each affinity resin has been splitted to be further incubated with apo-Tfn and holo-Tfn. Nitrocellulose membranes were probed with anti-Heph and anti-Tfn antibodies. C) The histogram on the right shows the relative amount of apo-Tfn co-precipitated by HephWT and HephD568H (n=4, data are expressed as mean ± SEM; * p < 0,05, and **p < 0,01). D-E) Representative co-IP of FLAG epitopes of HEK293T cells transfected with HephWT and D568H and undergone DSP cross-liking before lysis. The immunoprecipitated Heph/Fpn1 complexes were splitted to be further incubated with apo-Tfn or holo-Tfn. F) The histogram on the right shows the relative amount of apo-Tfn co-precipitated by HephWT and HephD568H (n=5, data are expressed as mean ± SEM; * p < 0,05, and **p < 0,01). The amount of apo-Tfn co-precipitated by HephWT and HephD568H, either secreted or inserted into the plasma membrane, was quantified by densitometric scanning of western blot. The amount of apo-Tfn interacting with HephWT was set as 100% interaction.

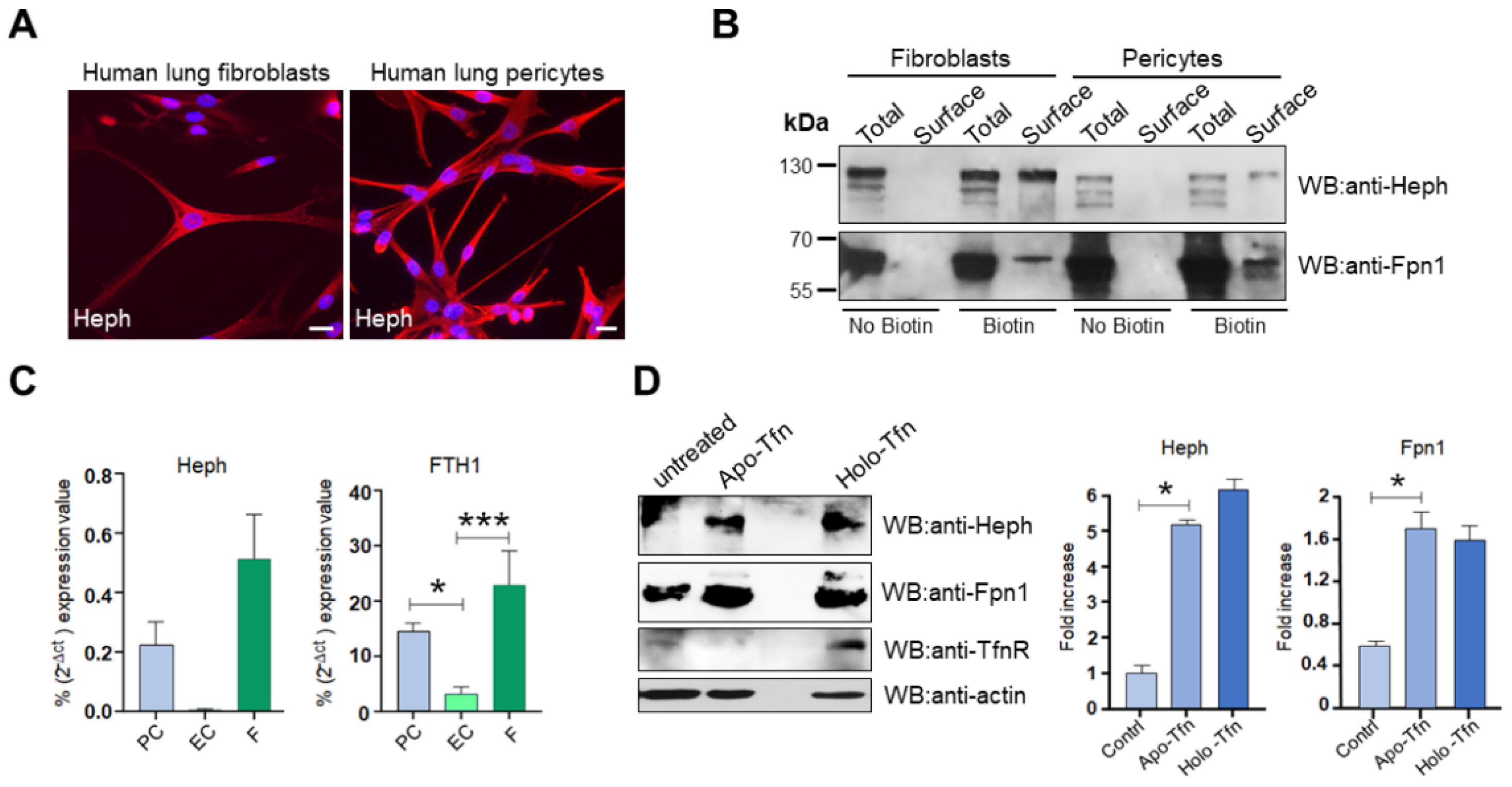

Figure 7.

Heph is expressed by lung fibroblasts and pericytes and is up-regulated in response to apo-Tfn. A) Representative epifluorescence images of primary lung fibroblasts and pericytes stained for Heph expression. Nuclei were stained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenyl indole (DAPI) in blue. Scale bar= 10 µm. B) Heph and Fpn1 derived from cultured lung fibroblasts and pericytes were detected upon surface biotinylation assay and detected by anti-Heph and anti-Fpn1 monoclonal antibodies. Non-biotinylated cells were processed in parallel to evaluate unspecific Heph and Fpn1 binding to neutravidin beads (n=4). C) Heph and ferritin heavy chain (FTH1) expression in lung pericytes (PC), lung endothelial cells (EC) and lung fibroblasts (F) were analysed by qRT-PCR. Glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as internal reference gene (n=4, data are expressed as mean ± SEM; * p < 0,05, ***p<0,001). D) Cultured lung pericytes were treated with 0,25 µM apo-Tfn or holo-Tfn of left untreated. Cells were harvested 72h after treatment and equal amount of total protein was run on an 8% SDS gel. Protein lysates were analysed by western blot for Heph, Fpn1 and TfnR expression. E) The histograms on the right show the up-regulation of Heph and Fpn1 expression observed upon apo-Tfn and holo-Tfn treatment. Western blot bands were quantified by densitometric scanning and expressed as fold increase respect to untreated cells (n=3, data are expressed as mean ± SEM; * p < 0,05).

Figure 7.

Heph is expressed by lung fibroblasts and pericytes and is up-regulated in response to apo-Tfn. A) Representative epifluorescence images of primary lung fibroblasts and pericytes stained for Heph expression. Nuclei were stained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenyl indole (DAPI) in blue. Scale bar= 10 µm. B) Heph and Fpn1 derived from cultured lung fibroblasts and pericytes were detected upon surface biotinylation assay and detected by anti-Heph and anti-Fpn1 monoclonal antibodies. Non-biotinylated cells were processed in parallel to evaluate unspecific Heph and Fpn1 binding to neutravidin beads (n=4). C) Heph and ferritin heavy chain (FTH1) expression in lung pericytes (PC), lung endothelial cells (EC) and lung fibroblasts (F) were analysed by qRT-PCR. Glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as internal reference gene (n=4, data are expressed as mean ± SEM; * p < 0,05, ***p<0,001). D) Cultured lung pericytes were treated with 0,25 µM apo-Tfn or holo-Tfn of left untreated. Cells were harvested 72h after treatment and equal amount of total protein was run on an 8% SDS gel. Protein lysates were analysed by western blot for Heph, Fpn1 and TfnR expression. E) The histograms on the right show the up-regulation of Heph and Fpn1 expression observed upon apo-Tfn and holo-Tfn treatment. Western blot bands were quantified by densitometric scanning and expressed as fold increase respect to untreated cells (n=3, data are expressed as mean ± SEM; * p < 0,05).

Figure 8.

Model of how HephWT and D568H respond to iron demand. Asbestos fibres endocytosed by macrophages (Mφ) actively subtract host iron, thus provoking a homeostatic response aimed at re-establishing the appropriate cellular iron concentration. This iron seeking phenotype depletes holo-Tfn and increases apo-Tfn levels. This iron demand is expected to be intercepted by nearby pericytes and fibroblasts which are equipped to appropriately sense it. HephD568H impaired in the apo-Tfn interaction will respond inefficiently to the increased iron demand, thus hindering the development of a dangerous iron overload condition. EC=Endothelial cell, F=Human lung Fibroblast, PC=pericyte, Mφ=macrophage, ROS=radical oxygen species, Heph=Hephaestin and Fpn1=Ferroportin. Created in BioRender. Longo, F. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/g34l832.

Figure 8.

Model of how HephWT and D568H respond to iron demand. Asbestos fibres endocytosed by macrophages (Mφ) actively subtract host iron, thus provoking a homeostatic response aimed at re-establishing the appropriate cellular iron concentration. This iron seeking phenotype depletes holo-Tfn and increases apo-Tfn levels. This iron demand is expected to be intercepted by nearby pericytes and fibroblasts which are equipped to appropriately sense it. HephD568H impaired in the apo-Tfn interaction will respond inefficiently to the increased iron demand, thus hindering the development of a dangerous iron overload condition. EC=Endothelial cell, F=Human lung Fibroblast, PC=pericyte, Mφ=macrophage, ROS=radical oxygen species, Heph=Hephaestin and Fpn1=Ferroportin. Created in BioRender. Longo, F. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/g34l832.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for Heph ferroxidase activity.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for Heph ferroxidase activity.

| Hephaestin |

Km

|

SEM |

Vmax (µM/min) |

SEM |

| WT |

7.71 |

1.55 |

10.60 |

0.80 |

| D568H |

5.38 |

0.97 |

10.30 |

0.60 |