Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Rare-earth high-entropy oxides are a new promising class of multifunctional materials characterized by their ability to stabilize complex, multi-cationic compositions into single-phase structures through configurational entropy. This feature enables fine-tuning structural properties such as oxygen vacancies, lattice distortions, and defect chemistry, making them promising for advanced technological applications. While initial research primarily focused on their catalytic performance in energy and environmental applications, recent research demonstrated their potential in optoelectronics, photoluminescent materials, and aerospace technologies. Progress in synthesis techniques has provided control over particle morphology, composition, and defect engineering, enhancing electronic, thermal, and mechanical properties. Rare-earth high-entropy oxides exhibit tunable bandgaps, exceptional thermal stability, and superior resistance to phase degradation, positioning them as next-generation materials. Despite these advances, challenges remain in scaling up production, optimizing compositions for specific applications, and understanding the fundamental mechanisms governing their multifunctionality. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the recent developments in rare-earth high-entropy oxides as relatively new and still underrated material of the future.

Keywords:

1. High-Entropy Oxides

1.1. Desing of HEOs

2. Rare Earth Elements

2.1. Properties and Significance

2.2. Properties and Application of Ceria

2.2.1. Ceria Electronic Structure and Defect Chemistry

3. Synthesis Approach and Structural Features

4. Next Generation Technologies

4.1. Energy Conversion and Storage

4.1.1. Application in Solid Oxide Fuel Cells

4.1.2. Achievements in Hydrogen Production

4.2. Catalysis and Environmental Achievements

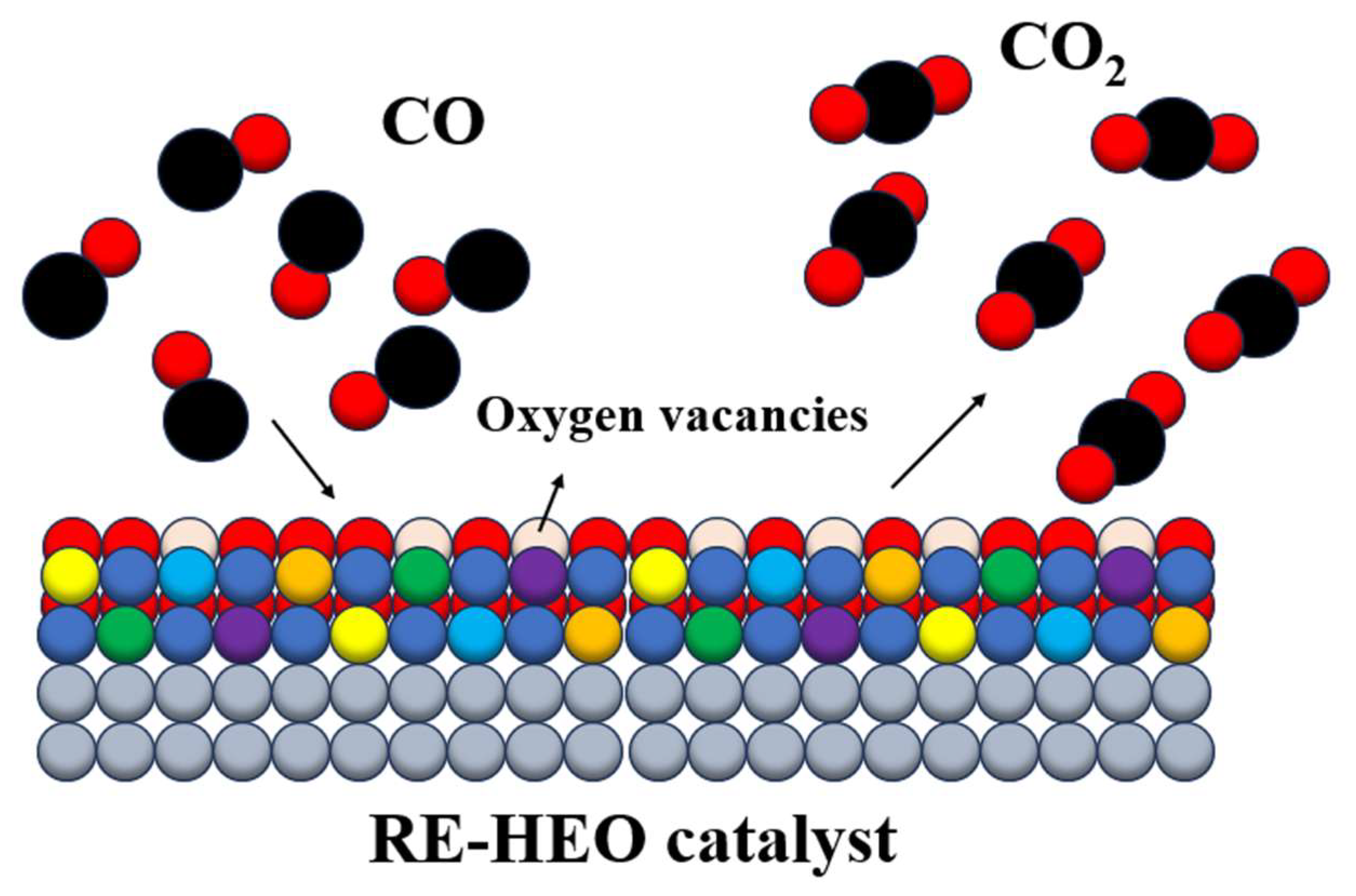

4.2.1. CO Oxidation

4.2.2. CO2 Reduction

4.3. Emerging Applications Beyond Energy and Environment

5. Future Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A.J.B. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375–377, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, C.M.; Sachet, E.; Borman, T.; Moballegh, A.; Dickey, E.C.; Hou, D.; Jones, J.L.; Curtarolo, S.; Maria, J.P. Entropy-stabilized oxides. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z.; Liang, J.; Dai, S. High-Entropy Perovskite Fluorides: A New Platform for Oxygen Evolution Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 4550–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.Z.; Gucci, F.; Zhu, H.; Chen, K.; Reece, M.J. Data-Driven Design of Ecofriendly Thermoelectric High-Entropy Sulfides. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 13027–13033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Sang, X.; Unocic, R.R.; Kinch, R.T.; Liu, X.; Hu, J.; Liu, H.; Dai, S. Mechanochemical-Assisted Synthesis of High-Entropy Metal Nitride via a Soft Urea Strategy. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z.; Gao, M.C.; Dahmen, K.A.; Liaw, P.K.; Lu, Z.P. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 61, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.W. Alloy design strategies and future trends in high-entropy alloys. Jom 2013, 65, 1759–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R. Recent progress of high-entropy materials for energy storage and conversion. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 782–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, C.M.; Rak, Z.; Brenner, D.W.; Maria, J.P. Local structure of the MgxNixCoxCuxZnxO(x=0.2) entropy-stabilized oxide: An EXAFS study. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 2732–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Wang, Q.; Schiele, A.; Chellali, M.R.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Wang, D.; Brezesinski, T.; Hahn, H.; Velasco, L.; Breitung, B. High-Entropy Oxides: Fundamental Aspects and Electrochemical Properties. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenadic, R.; Sarkar, A.; Clemens, O.; Loho, C.; Botros, M.; Chakravadhanula, V.S.K.; Kübel, C.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Gandhi, A.S.; Hahn, H. Multicomponent equiatomic rare earth oxides. Mater. Res. Lett. 2017, 5, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérardan, D.; Franger, S.; Dragoe, D.; Meena, A.K.; Dragoe, N. Colossal dielectric constant in high entropy oxides. Phys. Status Solidi - Rapid Res. Lett. 2016, 10, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesuz, M.; Spiridigliozzi, L.; Dell’Agli, G.; Bortolotti, M.; Sglavo, V.M. Synthesis and sintering of (Mg, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn)O entropy-stabilized oxides obtained by wet chemical methods. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 8074–8085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Du, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, W.; Chen, R.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Y.; et al. Low-temperature synthesis of small-sized high-entropy oxides for water oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 24211–24216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcerzak, M.; Kawamura, K.; Bobrowski, R.; Rutkowski, P.; Brylewski, T. Mechanochemical Synthesis of (Co,Cu,Mg,Ni,Zn)O High-Entropy Oxide and Its Physicochemical Properties. J. Electron. Mater. 2019, 48, 7105–7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassau, K. Handbook on the physics and chemistry of rare earths, vol. 14; 1993; Vol. 28; ISBN 9780444503466.

- Voncken, J.H.L. Physical and Chemical Properties of the Rare Earths. 2016, 53–72. [CrossRef]

- Balaram, V. Rare earth elements: A review of applications, occurrence, exploration, analysis, recycling, and environmental impact. Geosci. Front. 2019, 10, 1285–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, W.C. Magnetic properties of rare-earth metals and alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 1965, 36, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, H. Special Issue: Rare earth luminescent materials. Light Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Saji, S.E.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, H.; Du, Y.; Yan, C.H. Rare-Earth Incorporated Alloy Catalysts: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, D.; Ullah, H.; Yadav, M.; Kojčinović, J.; Šarić, S.; Szenti, I.; Skalar, T.; Finšgar, M.; Tian, M.; Kukovecz, Á.; et al. High-Entropy Oxides: A New Frontier in Photocatalytic CO2 Hydrogenation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 29946–29962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, R.; Nenning, A.; Kraynis, O.; Korobko, R.; Frenkel, A.I.; Lubomirsky, I.; Haile, S.M.; Rupp, J.L.M. A review of defect structure and chemistry in ceria and its solid solutions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 554–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coduri, M.; Checchia, S.; Longhi, M.; Ceresoli, D.; Scavini, M. Rare earth doped ceria: The complex connection between structure and properties. Front. Chem. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, S. C. Catalysis by Ceria and Related Materials Edited by Alessandro Trovarelli, vol. 2; 2002; ISBN: 1-86094-299-7. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 2, 12923–12924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Yasui, T. Crystal structure and the structural disorder of ceria from 40 to 1497 °c. Solid State Ionics 2006, 177, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. -J Lattice Parameters, Ionic Conductivities, and Solubility Limits in Fluorite-Structure MO2 Oxide [M = Hf4+, Zr4+, Ce4+, Th4+, U4+] Solid Solutions. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1989, 72, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshi, E.; Billinge, S.J.L. Underneath the Bragg Peaks: Structural Analysis of Complex Materials; 2012; Vol. 16; ISBN 9780080971339.

- Coles-Aldridge, A. V.; Baker, R.T. Oxygen ion conductivity in ceria-based electrolytes co-doped with samarium and gadolinium. Solid State Ionics 2020, 347, 115255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, S.J.; Kilner, J.A. Oxygen ion conductors. Mater. Today 2003, 6, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenda, J.; Świerczek, K.; Zajac, W. Functional materials for the IT-SOFC. J. Power Sources 2007, 173, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chueh, W.C.; McDaniel, A.H.; Grass, M.E.; Hao, Y.; Jabeen, N.; Liu, Z.; Haile, S.M.; McCarty, K.F.; Bluhm, H.; El Gabaly, F. Highly enhanced concentration and stability of reactive Ce 3+ on doped CeO 2 surface revealed in operando. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 1876–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kašpar, J.; Fornasiero, P.; Graziani, M. Use of CeO2-based oxides in the three-way catalysis. Catal. Today 1999, 50, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Ernst, J.; Kheradpour, P.; Bristow, C.A.; Lin, M.F.; Washietl, S.; Ay, F.; Meyer, P.E.; Stefano, L. Di; Candeias, R.; et al. High-Flux Solar-Driven Thermochemical Dissociation of CO2 and H2OUsing Nonstoichiometric Ceria. Science (80-. ). 2010, 330, 1797–1801. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M.; Bishop, S.R.; Rupp, J.L.M.; Tuller, H.L. Structural characterization and oxygen nonstoichiometry of ceria-zirconia (Ce1-xZrxO2-δ) solid solutions. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 4277–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Gillen, R.; Robertson, J. Study of CeO2 and its native defects by density functional theory with repulsive potential. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 24248–24256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhao, X.; An, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J. High-entropy (La0.2Nd0.2Sm0.2Eu0.2Gd0.2)2Ce2O7: A potential thermal barrier material with improved thermo-physical properties. J. Adv. Ceram. 2022, 11, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, D.; Kojčinović, J.; Marković, B.; Széchenyi, A.; Miletić, A.; Nagy, S.B.; Ziegenheim, S.; Szenti, I.; Sapi, A.; Kukovecz, Á.; et al. Sol-Gel Synthesis of Ceria-Zirconia-Based High-Entropy Oxides as High-Promotion Catalysts for the Synthesis of 1,2-Diketones from Aldehyde. Molecules 2021, 26, 6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

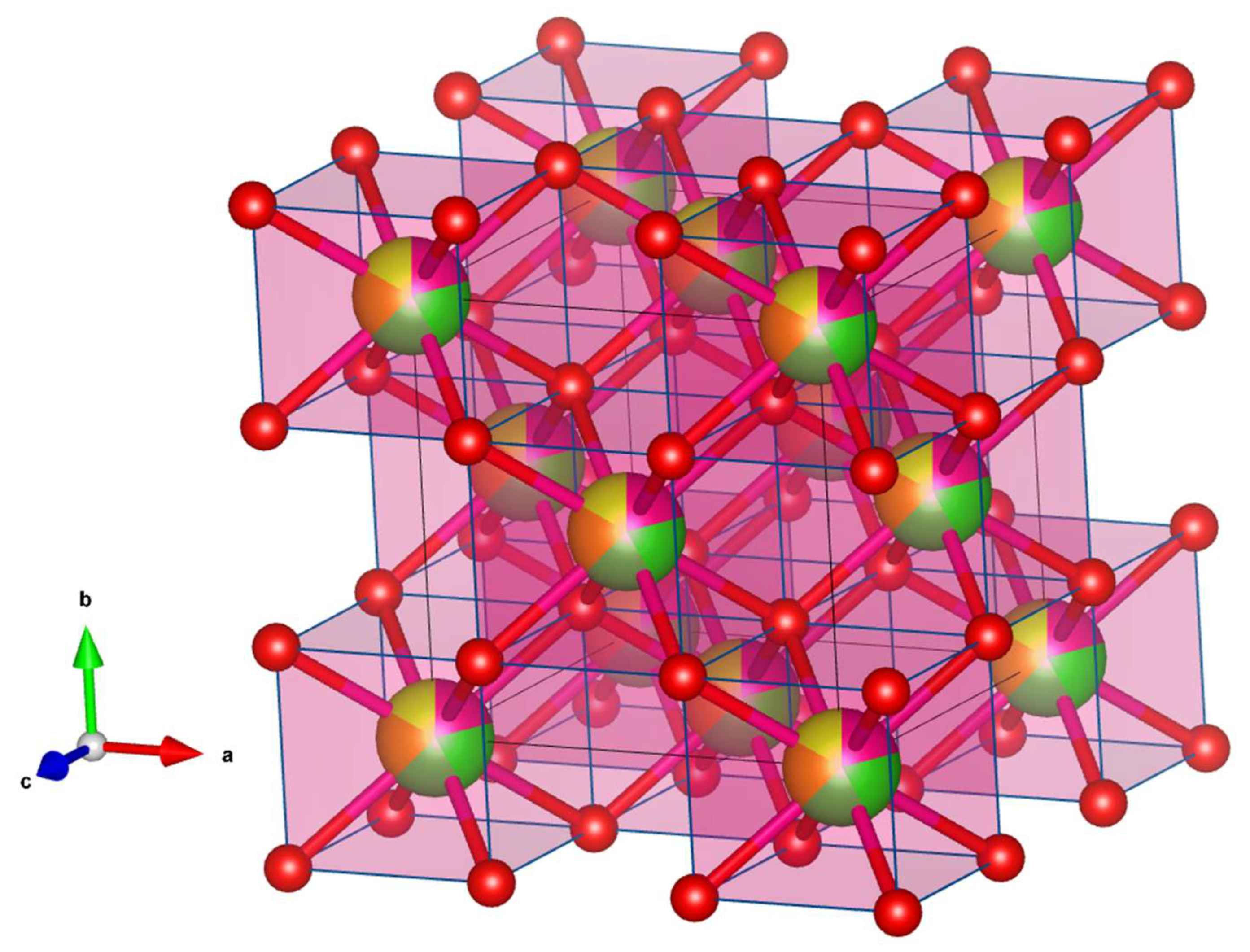

- Nundy, S.; Tatar, D.; Kojčinović, J.; Ullah, H.; Ghosh, A.; Mallick, T.K.; Meinusch, R.; Smarsly, B.M.; Tahir, A.A.; Djerdj, I. Bandgap Engineering in Novel Fluorite-Type Rare Earth High-Entropy Oxides (RE-HEOs) with Computational and Experimental Validation for Photocatalytic Water Splitting Applications. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2022, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Yang, T.; He, W.; Yang, W.; Wang, N.; Ma, S.; Shih, K.; Liao, C. Solution combustion synthesis of Ce-free high entropy fluorite oxides: Formation, oxygen vacancy and long-term thermal stability. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 7431–7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Mao, Y.; Shi, S.; Wang, J.; Zong, R. Solution combustion synthesis of high-entropy rare earth oxide Ce0.2La0.2Gd0.2Y0.2Lu0.2O1.6:Eu3+phosphor with intense blue-light excitable red emission for solid-state lighting. J. Adv. Ceram. 2024, 13, 1852–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Loho, C.; Velasco, L.; Thomas, T.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Hahn, H.; Djenadic, R. Multicomponent equiatomic rare earth oxides with a narrow band gap and associated praseodymium multivalency. Dalt. Trans. 2017, 46, 12167–12176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nundy, S.; Tatar, D.; Kojčinović, J.; Ullah, H.; Ghosh, A.; Mallick, T.K.; Meinusch, R.; Smarsly, B.M.; Tahir, A.A.; Djerdj, I. Bandgap Engineering in Novel Fluorite-Type Rare Earth High-Entropy Oxides (RE-HEOs) with Computational and Experimental Validation for Photocatalytic Water Splitting Applications. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2022, 2200067, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Chem, W.; Hou, K.; Duan, X.; Liu, L.; Xu, J. Phases, Electrical Properties, and Stability of High-Entropy Pyrochlores [(La0. 25Nd0.25Sm0.25Eu0.25)1−xCax]2Zr2O7−δ Oxides. Phys. Status Solidi A, 2024, 221, 2300753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, R.; Windsor, D.; Drewry, S.; Page, K.; Xu, H.; Keppens, V.; Weber, W.J. Synthesis and properties of rare-earth high-entropy perovskite, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 124, 214101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Ganguly, D.; Sundara, R.; Bhattacharya, S. Noble Metal-Free High Entropy Perovskite Oxide with High Cationic Dispersion Enhanced Oxygen Redox Reactivity, ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202401836. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xuan, Y.; Gao, K.; Sun, C.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; Chang, S.; Liu, X. High-entropy perovskite oxides for direct solar-driven thermochemical CO2 splitting. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 1564–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.Y.; Wang, M.F.; Ni, J.J.; He, Y.Z.; Ji, H.Q.; Liu, S.S.; Qian, T.; Yan, C.L. High-entropy alloys for accessing hydrogen economy via sustainable production of fuels and direct application in fuel cells. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 3553–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.R.; Guo, R.F.; Cao, Y.; Jin, S.B.; Qiu, X.M.; Shen, P. Ultrafast densification of high-entropy oxide (La0.2Nd0.2Sm0.2Eu0.2Gd0.2)2Zr2O7 by reactive flash sintering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 2855–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shijie, Z.; Na, L.; Liping, S.; Qiang, L.; Lihua, H.; Hui, Z. A novel high-entropy cathode with the A2BO4-type structure for solid oxide fuel cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 895, 162548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F. ; Xu, K; He, F. ; Xu, Y.; Du, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Ding, D.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y. An Active and Contaminants-Tolerant High-Entropy Electrode for Ceramic Fuel Cells, ACS Energy Lett. 2024, 9, 2, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Liu, Z.; Di, H.; Bai, Y.; Yang, G.; Medvedev, D.A.; Luo, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhou, W.; Ran, R.; et al. High-entropy materials for solid oxide cells : Synthesis, applications, and prospects. J. Energy Chem. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, T.; Kumar, R.; Khan, S.; Singh, K.; Kolte, J. Structural and Electrical Properties of Gd Doped CeO2 (GDC) Nanoceramics for Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Applications. Transactions of the Indian Ceramic Society, 81, 127–132.

- Zhang, S.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Luo, L.; Cheng, L.; Xu, X.; Yu, J. Insight into the effect of Gd-doping on conductance and thermal matching of CeO2 for solid oxide fuel cell. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 55190–55200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, L.A.; Bosetti, A.; Malavasi, L. High-Entropy Perovskite Oxides for Thermochemical Solar Fuel Production. Energy Technol. 2024, 2401199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, Z.J.; Lu, P.; Zhang, G.; Sharma, Y.; Rutherford, B.X.; Dhole, S.; Roy, P.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Structural and Optical Properties of High Entropy (La,Lu,Y,Gd,Ce)AlO3 Perovskite Thin Films. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- YILDIZ, İ. Synthesis and characterization of b-site controlled la-based high entropy perovskite oxides. J. Sci. Reports-A, 2023; 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Walczak, K.; Milewska, A.; Płotek, J.; Budziak, A.; Molenda, J. Electrochemical performance of different high-entropy cathode materials for Na-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 968, 172316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Saleem, M.; Sattar, T.; Khan, M.Z.; Koh, J.H.; Gohar, O.; Hussain, I.; Zhang, Y.; Hanif, M.B.; Ali, G.; et al. High-entropy battery materials: Revolutionizing energy storage with structural complexity and entropy-driven stabilization. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Reports 2025, 163, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tio, L.O.; Wo, N.O.; Asri, M. Investigation of optical properties of high-entropy oxide glasses. 2024, 3.

- Salian, A.; K, A.P.; Mandal, S. Phase stabilized solution combustion processed (Ce0.2La0.2Pr0.2Sm0.2Y0.2)O1.6-δ: An exploration of the dielectric properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 960, 170786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.S.; Patil, A. V.; Dighavkar, C.G.; Adole, V.A.; Tupe, U.J. Synthesis techniques and applications of rare earth metal oxides semiconductors: A review. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2022, 796, 139555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhu, S.; Luo, X.; Ma, X.; Shi, C.; Song, H.; Sun, Z.; Guo, Y.; Dedkov, Y.; Kang, B.; et al. Magnetic phase transition and continuous spin switching in a high-entropy orthoferrite single crystal. Front. Phys. 2024, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, R.; Sarkar, A.; Velasco, L.; Kruk, R.; Brand, R.A.; Eggert, B.; Ollefs, K.; Weschke, E.; Wende, H.; Hahn, H. Magnetic properties of rare-earth and transition metal based perovskite type high entropy oxides. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Bérardan, D.; Dragoe, D.; Riviere, E.; Takayama, T.; Takagi, H.; Dragoe, N. Magnetic and electrical properties of high-entropy rare-earth manganites. Mater. Today Phys. 2023, 32, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikalova, E.Y.; Kalinina, E.G.; Pikalova, N.S.; Filonova, E.A. High-Entropy Materials in SOFC Technology: Theoretical Foundations for Their Creation, Features of Synthesis, and Recent Achievements. Materials (Basel). 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Kee, R.; Zhu, H.; Sullivan, N.; Zhu, L.; Bian, L.; Jennings, D.; O’Hayre, R. Highly efficient reversible protonic ceramic electrochemical cells for power generation and fuel production. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, L.; Jeon, S.Y.; Namgung, Y.; Hanantyo, M.P.G.; Park, J.; Islam, M.S.; Sengodan, S.; Song, S.J. Ternary co-doped ytterbium-scandium stabilized zirconia electrolyte for solid oxide fuel cells. Solid State Ionics 2024, 408, 116507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhigachev, A.O.; Rodaev, V. V.; Zhigacheva, D. V.; Lyskov, N. V.; Shchukina, M.A. Doping of scandia-stabilized zirconia electrolytes for intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cell: A review. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 32490–32504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, L.; Hou, N.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y. Solid oxide fuel cell with a spin-coated yttria stabilized zirconia/gadolinia doped ceria bi-layer electrolyte. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 13220–13227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellon, O.; Sammes, N.M.; Staniforth, J. Mechanical properties and electrochemical characterisation of extruded doped cerium oxide for use as an electrolyte for solid oxide fuel cells. J. Power Sources 1998, 75, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omeiza, L.A.; Kabyshev, A.; Bekmyrza, K.; Kuterbekov, K.A.; Kubenova, M.; Zhumadilova, Z.A.; Subramanian, Y.; Ali, M.; Aidarbekov, N.; Azad, A.K. Constraints in sustainable electrode materials development for solid oxide fuel cell: A brief review. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2025, 8, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyev, A.; Shipilova, A.; Smolyanskiy, E.; Rabotkin, S.; Semenov, V. The Properties of Intermediate-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells with Thin Film Gadolinium-Doped Ceria Electrolyte. Membranes (Basel). 2022, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Liu, C.; Lei, Z.; Chen, F.; Peng, S. Progress report on the catalyst layers for hydrocarbon-fueled SOFCs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 39369–39386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, W.G.; Miao, H.; Li, T.; Xu, C. Evaluation of carbon deposition behavior on the nickel/yttrium-stabilized zirconia anode-supported fuel cell fueled with simulated syngas. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Ni, N.; Ding, Q.; Zhao, X. Tailoring high-temperature stability and electrical conductivity of high entropy lanthanum manganite for solid oxide fuel cell cathodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 2256–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Du, C.; Zhou, R.; Li, D.; Wang, S.; Tian, C.; Chen, C. Synthesis and characterization of Ce1–x(Gd1/5Sm1/5Er1/5Y1/5Bi1/5)xO2–δ solid electrolyte for SOFCs. J. Rare Earths 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, E.; Grenier, J.C.; Bassat, J.M.; Jacob, A.; Delatouche, B.; Bourdais, S. On the ionic conductivity of some zirconia-derived high-entropy oxides. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 4505–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowa, J.; Stępień, A.; Szymczak, M.; Zajusz, M.; Czaja, P.; Świerczek, K. High-entropy approach to double perovskite cathode materials for solid oxide fuel cells: Is multicomponent occupancy in (La,Pr,Nd,Sm,Gd)BaCo2O5+δ affecting physicochemical and electrocatalytic properties? Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunjiao, L.; Liping, S.; Qiang, L.; Lihua, H.; Hui, Z. Doping effects of alkaline earth element on oxygen reduction property of high-entropy perovskite cathode for solid oxide fuel cells. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 941, 117546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Mori, T.; Jiang, S.P. Development of nickel based cermet anode materials in solid oxide fuel cells – Now and future. Mater. Reports Energy 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Kishimoto, H.; Ishiyama, T.; Develos-Bagarinao, K.; Yamaji, K.; Horita, T.; Yokokawa, H. A review of sulfur poisoning of solid oxide fuel cell cathode materials for solid oxide fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2020, 478, 228763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, M.; Yang, G.; Wang, W.; Ran, R.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Z. Infiltrated NiCo Alloy Nanoparticle Decorated Perovskite Oxide: A Highly Active, Stable, and Antisintering Anode for Direct-Ammonia Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Small 2020, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, G.; Wu, H.; Beshiwork, B.A.; Tian, D.; Zhu, S.; Yang, Y.; Lu, X.; Ding, Y.; Ling, Y.; et al. A high-entropy perovskite cathode for solid oxide fuel cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 872, 159633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabuni, M.F.; Li, T.; Othman, M.H.D.; Adnan, F.H.; Li, K. Progress in Solid Oxide Fuel Cells with Hydrocarbon Fuels. Energies 2023, 16, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Ling, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ga, Y.; Wei, B.; Lv, Z. Utilizing High Entropy Effects for Developing Chromium-Tolerance Cobalt-Free Cathode for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2304728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Hossain, M.D.; Mukherjee, P.; Lee, J.; Winther, K.T.; Leem, J.; Jiang, Y.; Chueh, W.C.; Bajdich, M.; Zheng, X. Synergistic effects of mixing and strain in high entropy spinel oxides for oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

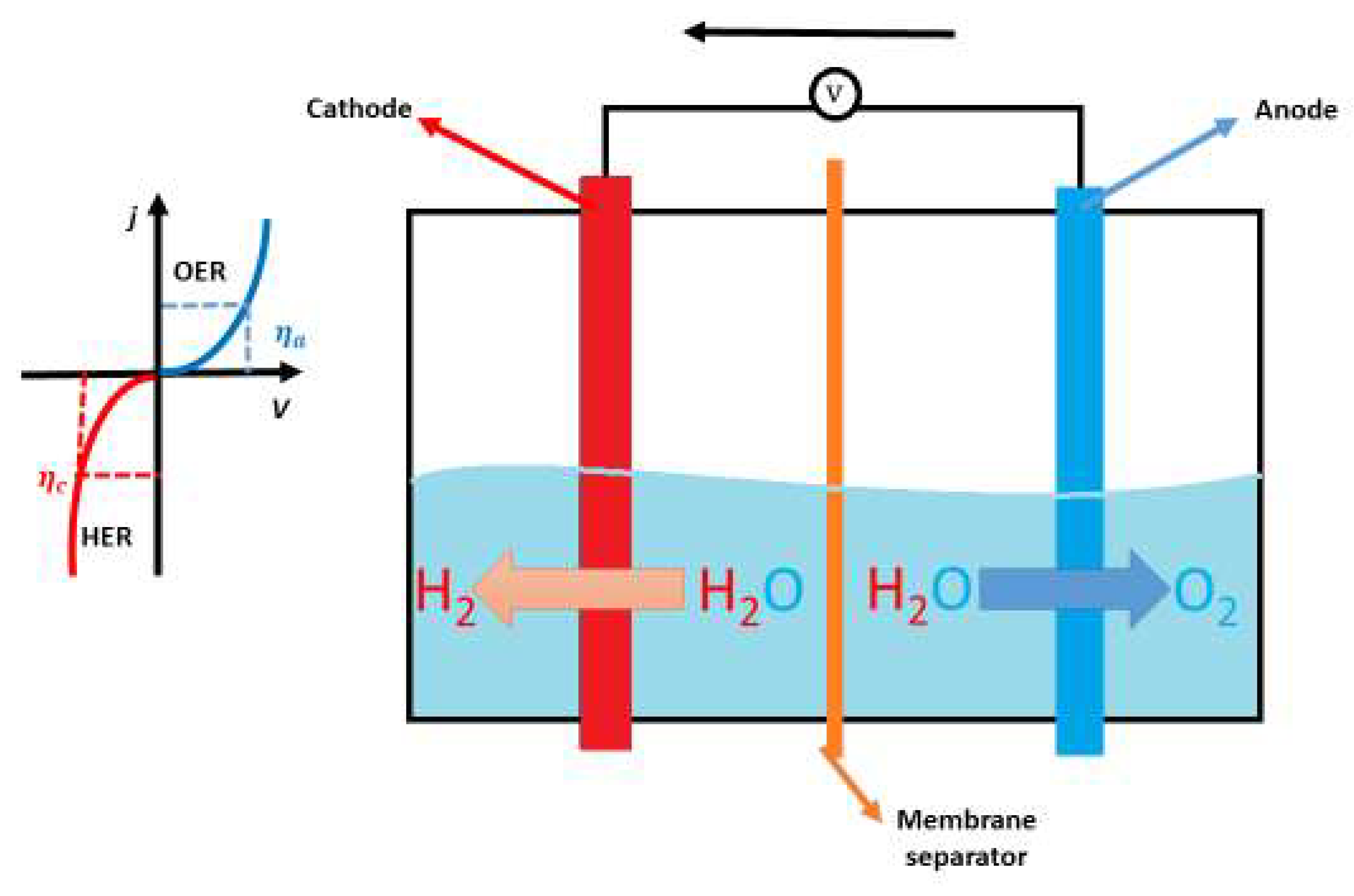

- Jiao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Jaroniec, M.; Qiao, S.Z. Design of electrocatalysts for oxygen- and hydrogen-involving energy conversion reactions, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2015, 44, 2060–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Vasileff, A.; Qiao, S.-Z. he Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Alkaline Solution: From Theory, Single Crystal Models, to Practical Electrocatalysts, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Zhang, Y. Noble metal-free hydrogen evolution catalysts for water splitting, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2015, 44, 5148–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Guio, C. G.; Stern, L.A. ; Hu. X. Nanostructured hydrotreating catalysts for electrochemical hydrogen evolution, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2014, 43, 6555–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petel, R.K.; Jenjeti, R. N.; Kumar, R.; Bhattacharya, N.; Kumar, S.; Ojha, S.K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Qu, K.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Klewe, C.; Shafer, P.; Sampath, S.; Middey, S. Thickness dependent OER electrocatalysis of epitaxial thin film of high entropy oxide, 2023, Appl. Phys. Rev. 10, 031407; [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.K.; Jenjeti, R.N.; Kumar, R.; Bhattacharya, N.; Klewe, C.; Shafer, P.; Sampath, S.; Middey, S. Epitaxial thin film of high entropy oxide as electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. 2022, 1–19.

- Liu, Z.; Tang, Z.; Song, Y.; Yang, G.; Qian, W.; Yang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Ran, R.; Wang, W.; Zhou, W.; et al. High-Entropy Perovskite Oxide: A New Opportunity for Developing Highly Active and Durable Air Electrode for Reversible Protonic Ceramic Electrochemical Cells. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.Y.; Wang, J.J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Ma, T.Y.; Han, X.P.; Hu, W. Bin High-entropy oxide-supported platinum nanoparticles for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 1537–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Fu, H.; Sun, M.; Wang, S.; Huang, B.; Du, Y. Pt-Modified High Entropy Rare Earth Oxide for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution in pH-Universal Environments, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 13, 9012–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C. Perspective on CO oxidation over Pd-based catalysts, Catal. Sci. Technol., 2015, 5, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, H.; Türkan, H.; Vucinic, S.; Naqvi, S.; Bedair, R.; Rezaee, R.; Tsatsakis, A. Carbon monoxide poisoning. Toxicol. Reports 2020, 7, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierhals, J. Carbon Monoxide, 2001, In Ullmanns Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley.

- Soliman, N.K. Factors affecting CO oxidation reaction over nanosized materials: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 2395–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, H.-J.; Meijer, G.; Scheffler, M.; Schlogl, R.; Wolf, M. CO Oxidation as a Prototypical Reaction for Heterogeneous Processes, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 50, 10064-10094. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mi, J.; Wu, Z.S. Recent status and challenging perspective of high entropy oxides for chemical catalysis. Chem Catal. 2022, 2, 1624–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, P.A.; Wyrwa, J.; Kubiak, W.W. Synthesis and Catalytic Performance of High-Entropy Rare-Earth. 2024.

- Riley, C; De La Riva, A.; Park, J. E.; Percival ,S. J.; Benacidez, A.; Coker, E. N.; Aidun, R. E.; Paisleyy, E.A.; Datye, A.; Chou, S. S. A High Entropy Oxide Designed to Catalyze CO Oxidation Without Precious Metals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 7, 8120–8128. [CrossRef]

- Haruta, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Sano, H.; Yamada, N. Novel Gold Catalysts for the Oxidation of Carbon Monoxide at a Temperature far Below 0 °C, Chemistry Letters, 1987, 16, 405–408. [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.H.; Sasirekha, N.; Rajesh, B.; Chen, Y.W. CO oxidation on ceria- and manganese oxide-supported gold catalysts. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007, 58, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Halim, K.S.; Khedr, M.H.; Nasr, M.I.; El-Mansy, A.M. Factors affecting CO oxidation over nanosized Fe2O3. Mater. Res. Bull. 2007, 42, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Tan, C.S. A review: CO2 utilization. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2014, 14, 480–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweku, D.; Bismark, O.; Maxwell, A.; Desmond, K.; Danso, K.; Oti-Mensah, E.; Quachie, A.; Adormaa, B. Greenhouse Effect: Greenhouse Gases and Their Impact on Global Warming. J. Sci. Res. Reports 2018, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raciti, D.; Wang, C. Recent Advances in CO2 Reduction Electrocatalysis on Copper, ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 7, 1545–1556. [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Rahaman, M.; Bharti, J.; Reisner, E.; Robert, M.; Ozin, G. A.; Hu, Y. H. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction, Nat Rev Methods Primers 2023, 3. [CrossRef]

- Stolan, D.; Medina, F.; Urakawa, A. Improving the Stability of CeO2 Catalyst by Rare Earth Metal Promotion and Molecular Insights in the Dimethyl Carbonate Synthesis from CO2 and Methanol with 2-Cyanopyridine, ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4, 3181–3193. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Direct Synthesis of Dimethyl Carbonate from Methanol and Carbon Dioxide Catalyzed by Cerium-Based High-Entropy Oxides. Catal. Letters 2024, 154, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulska, E.; Breczko, J.; Basa, A.; Dubis, A.T. Rare-earth metals-doped nickel aluminate spinels for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, A.R.; Skoropata, E.; Sharma, Y.; Lapano, J.; Heitmann, T.W.; Musico, B.L.; Keppens, V.; Gai, Z.; Freeland, J.W.; Charlton, T.R.; et al. Designing Magnetism in High Entropy Oxides (Adv. Sci. 10/2022). Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2200391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocconcelli, M.; Miertschin, D.; Regmi, B.; Crater, D.; Stramaglia, F.; Yao, L.; Bertacco, R.; Piamonteze, C.; Van Dijken, S.; Farhan, A. Spin reorientation in Dy-based high-entropy oxide perovskite thin films. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, 134422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Kruk, R.; Hahn, H. Magnetic properties of high entropy oxides. Dalt. Trans. 2021, 50, 1973–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Xiang, X.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Z.Y. High-entropy oxides as energy materials: from complexity to rational design. Mater. Futur. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bererdan, D.; Franger, S.; Dragoe, D.; Meedna, A.K.; Dragoe, N. Colossal dielectric constant in high entropy oxides, Phys. Status Solidi 2016, 10, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Eggert, B.; Velasco, L.; Mu, X.; Lill, J.; Ollefs, K.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Wende, H.; Kruk, R.; Brand, R.A.; et al. Role of intermediate 4 f states in tuning the band structure of high entropy oxides. APL Mater. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhakar, M.; Khandelwal, A.; Jha, S.K.; Kante, M.V.; Keßler, P.; Lemmer, U.; Hahn, H.; Aghassi-Hagmann, J.; Colsmann, A.; Breitung, B.; et al. High-Throughput Screening of High-Entropy Fluorite-Type Oxides as Potential Candidates for Photovoltaic Applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandilya, P.K.; Lake, D.P.; Mitchell, M.J.; Sukachev, D.D.; Barclay, P.E. Optomechanical interface between telecom photons and spin quantum memory. Nat. Phys. 2021, 17, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Roy, A.; Rai, S.B. Photoluminescence behavior of rare earth doped self-activated phosphors (i.e., niobate and vanadate) and their applications. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 16260–16271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surendran, M.; Rollag, J.R.; Stevens, C.E.; Fu, C.-T.-; Kamarasubramanian, H.; Wang, Z.; Schlom, D. G.; Gibson, R.; Hendrickson, J.R.; Ravichandran, J. Epitaxial Rare-Earth-Doped Complex Oxide Thin Films for Infrared Application, ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 3539–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothi, P.R.; Liyanage, W.; Jiang, B.; Paladugu, S.; Olds, D.; Gilbert, D.A.; Page, K. Persistent Structure and Frustrated Magnetism in High Entropy Rare-Earth Zirconates, Small 2022, 18, 2101323. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, K.; Dai, M.; Xu, H.; Wei, Y.; Wang, R.; Fu, Z. oward Ultra-High Sensitivity Optical Thermometers and Bright Yellow LEDs Based on Phonon-Assisted Energy Transfer in Rare Earth-Doped La2ZnTiO6 Double Perovskite, Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 30, 14142–14151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćirić, A.; Stojadinović, S.; Dramićanin, M.D. An extension of the Judd-Ofelt theory to the field of lanthanide thermometry. J. Lumin. 2019, 216, 116749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Luo, B.; Peng, T.; Wang, J. High-Entropy Perovskite Oxide Photonic Synapses, Adv. Optical Mater. 2024, 12, 2303248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, T.B.; Ryadun, A.A.; Rashchenko, S. V.; Davydov, A. V.; Baykalova, E.B.; Solntsev, V.P. A Photoluminescence Study of Eu3+, Tb3+, Ce3+ Emission in Doped Crystals of Strontium-Barium Fluoride Borate Solid Solution Ba4−xSr3+x(BO3)4−yF2+3y (BSBF). Materials (Basel). 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, V.V.; Dhoble, S.J.; Yerpude, A.N. Photoluminescence properties of Pb5(PO4)3Br:RE (RE = Dy3+, Eu3+ and Tb3+) phosphor synthesised using solid-state method, Luminescence 2024, 39, e4751. [CrossRef]

- Lü, W.; Wang, H.; Jia, C.; Kang, X. Generating green and yellow lines in Y6Si3O9N4:Ce3+,Tb3+/Dy3+ oxynitrides phosphor. J. Lumin. 2019, 213, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, E.; Kalaycioglu Ozpozan, N.; Kalem, V. The Investigation of the Effect of La3+, Eu3+, and Sm3+ Ions on Photoluminescence and Piezoelectric Behavior of RE1.90Y0.10Zr2O7 (RE: Eu, Sm and Y: La, Sm, Eu) Pyrochlore-Based Multifunctional Smart Advanced Materials. Luminescence 2024, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaßen, R.; Mack, D.E.; Tandler, M.; Sohn, Y.J.; Sebold, D.; Guillon, O. Unique performance of thermal barrier coatings made of yttria-stabilized zirconia at extreme temperatures (>1500°C). J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Han, C.; Chen, Y.; Guo, F.; Lu, J.; Zhou, M.; Luo, L.; Zhao, X. Interfacial Stability between High-Entropy (La0.2Yb0.2Sm0.2Eu0.2Gd0.2)2Zr2O7 and Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia for Advanced Thermal Barrier Coating Applications. Coatings 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; zhang, S.; Gu, S.; Li, W. Thermophysical properties of a novel high entropy hafnate ceramic. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 85, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).