Submitted:

18 February 2024

Posted:

19 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

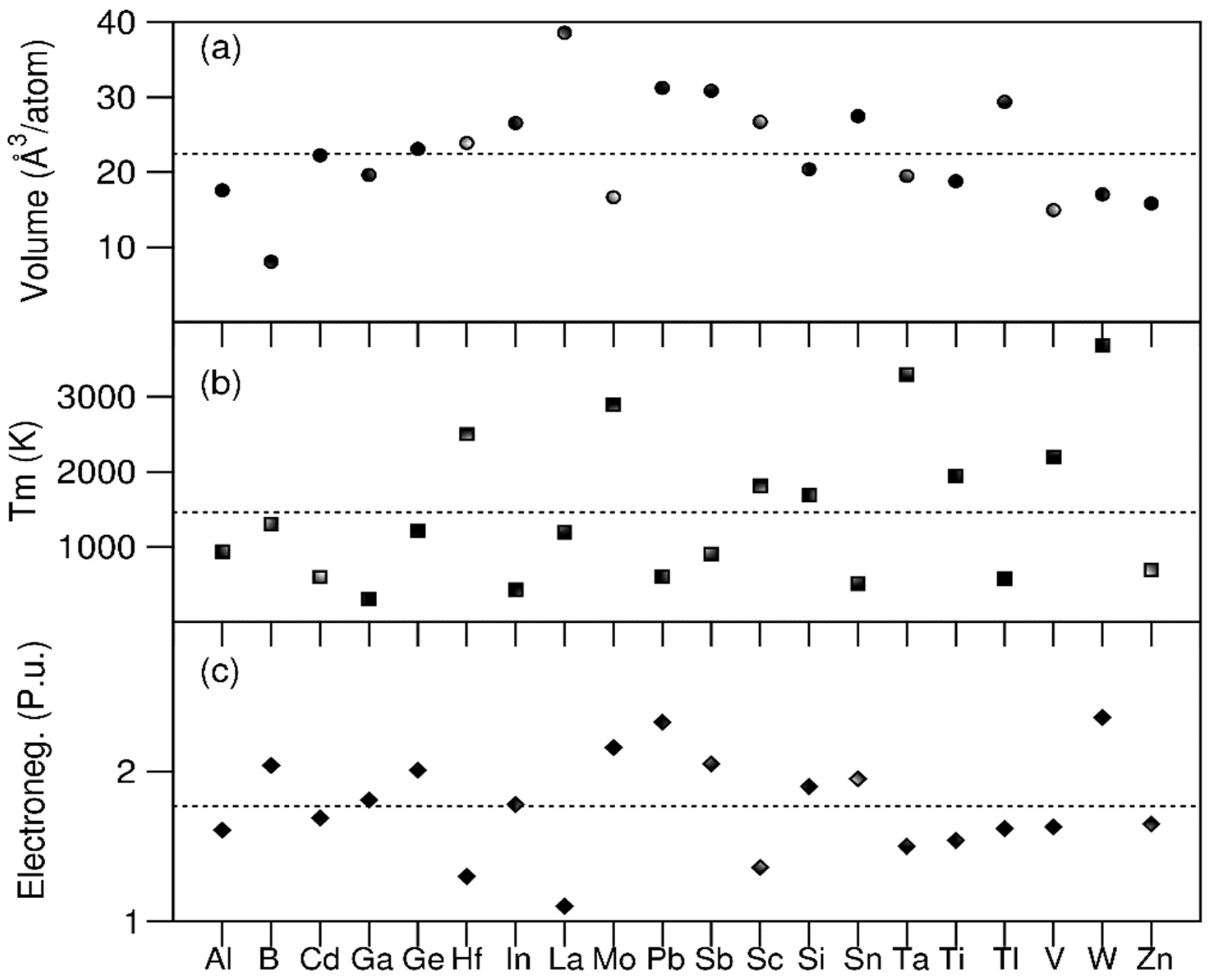

2. Basic and collective properties of the 20 elements

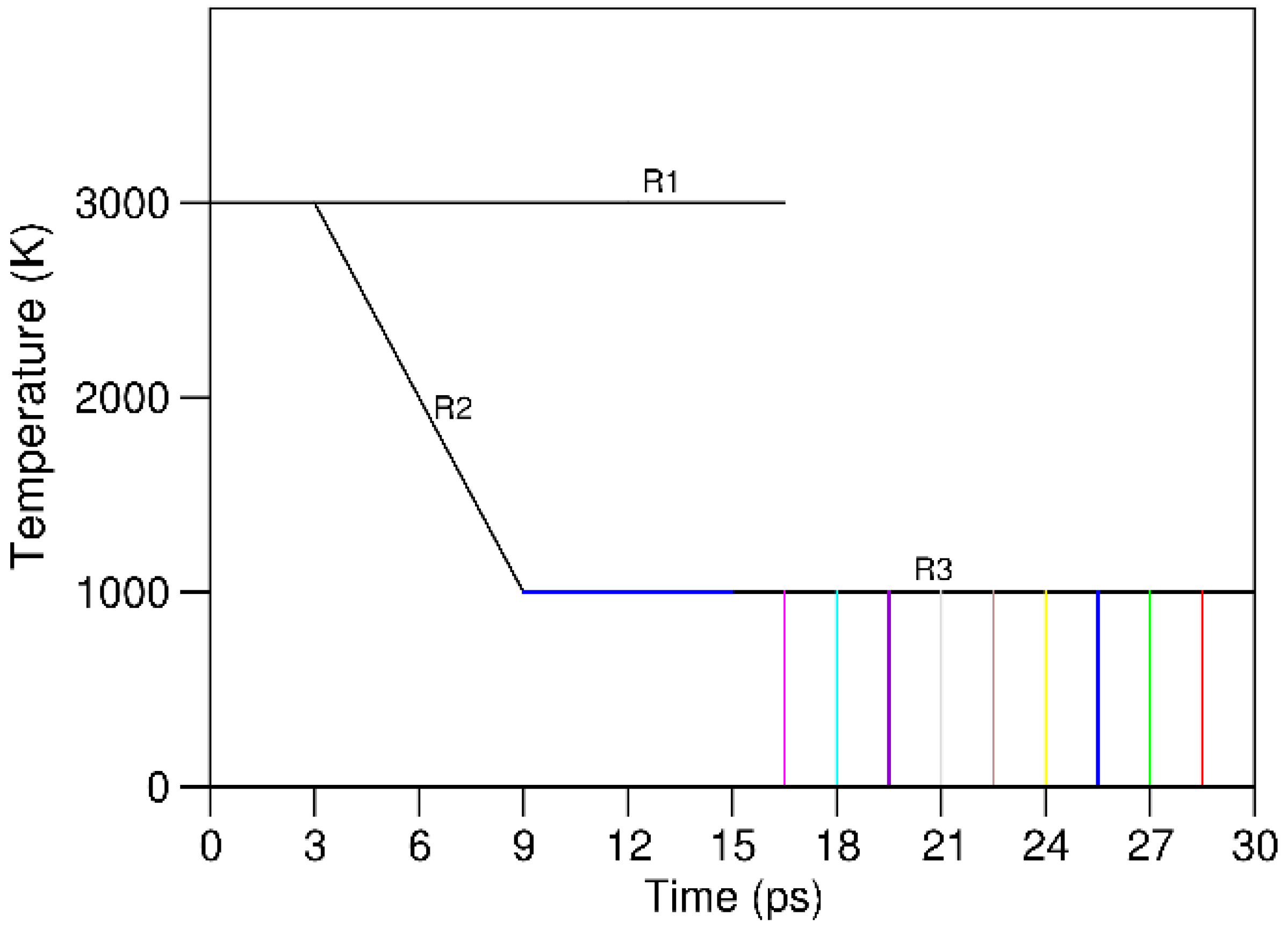

3. Details of ab initio molecular dynamics simulations

4. Results and discussions

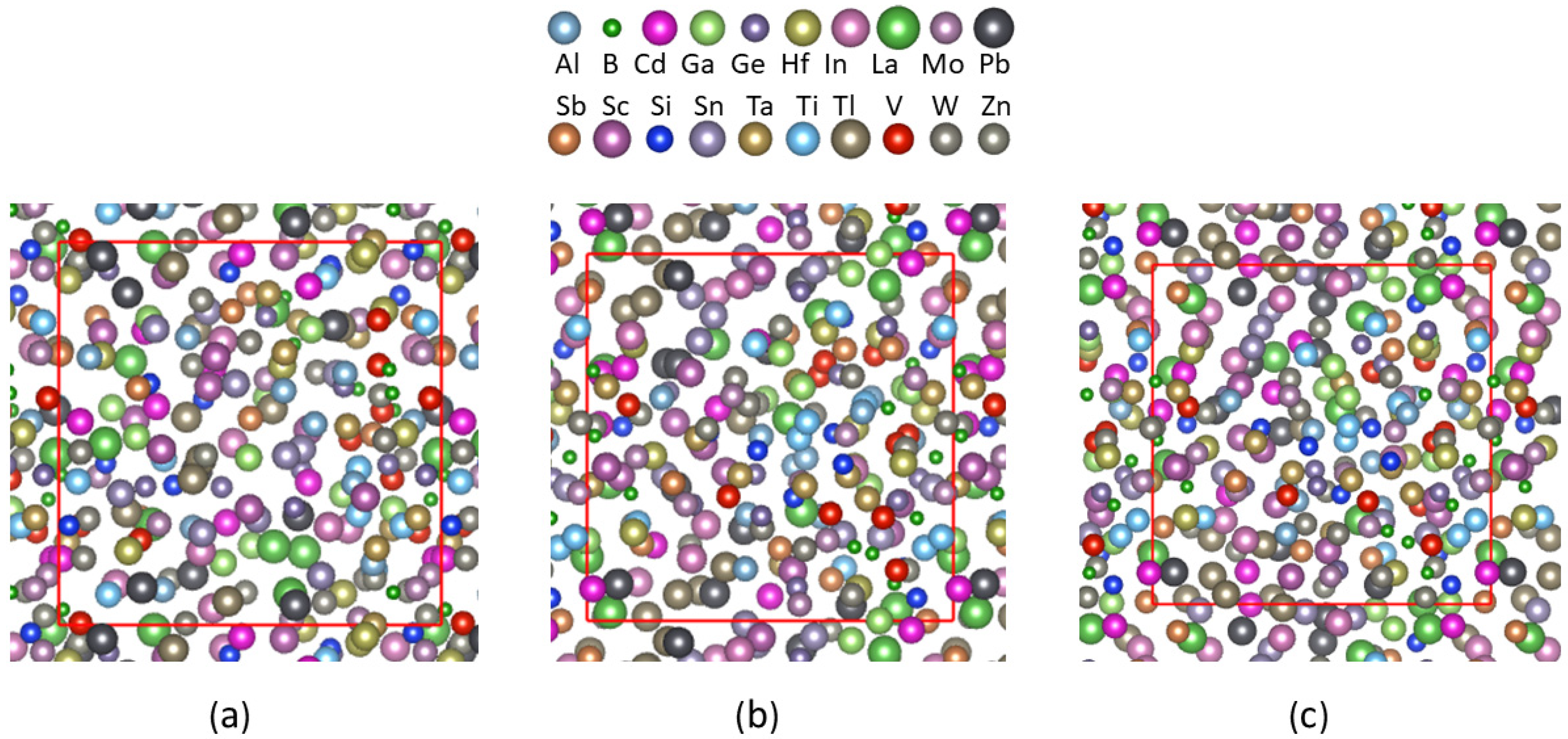

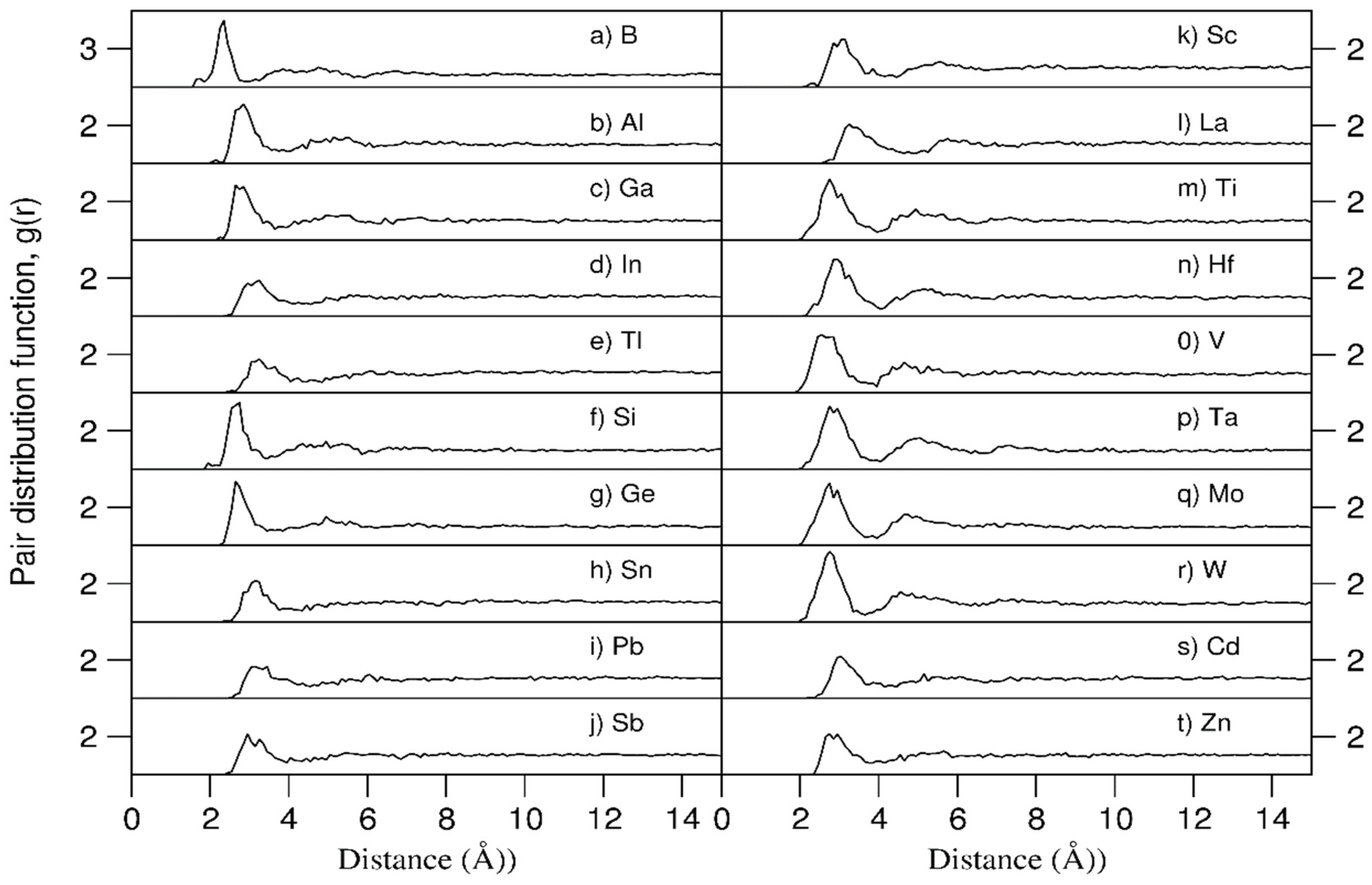

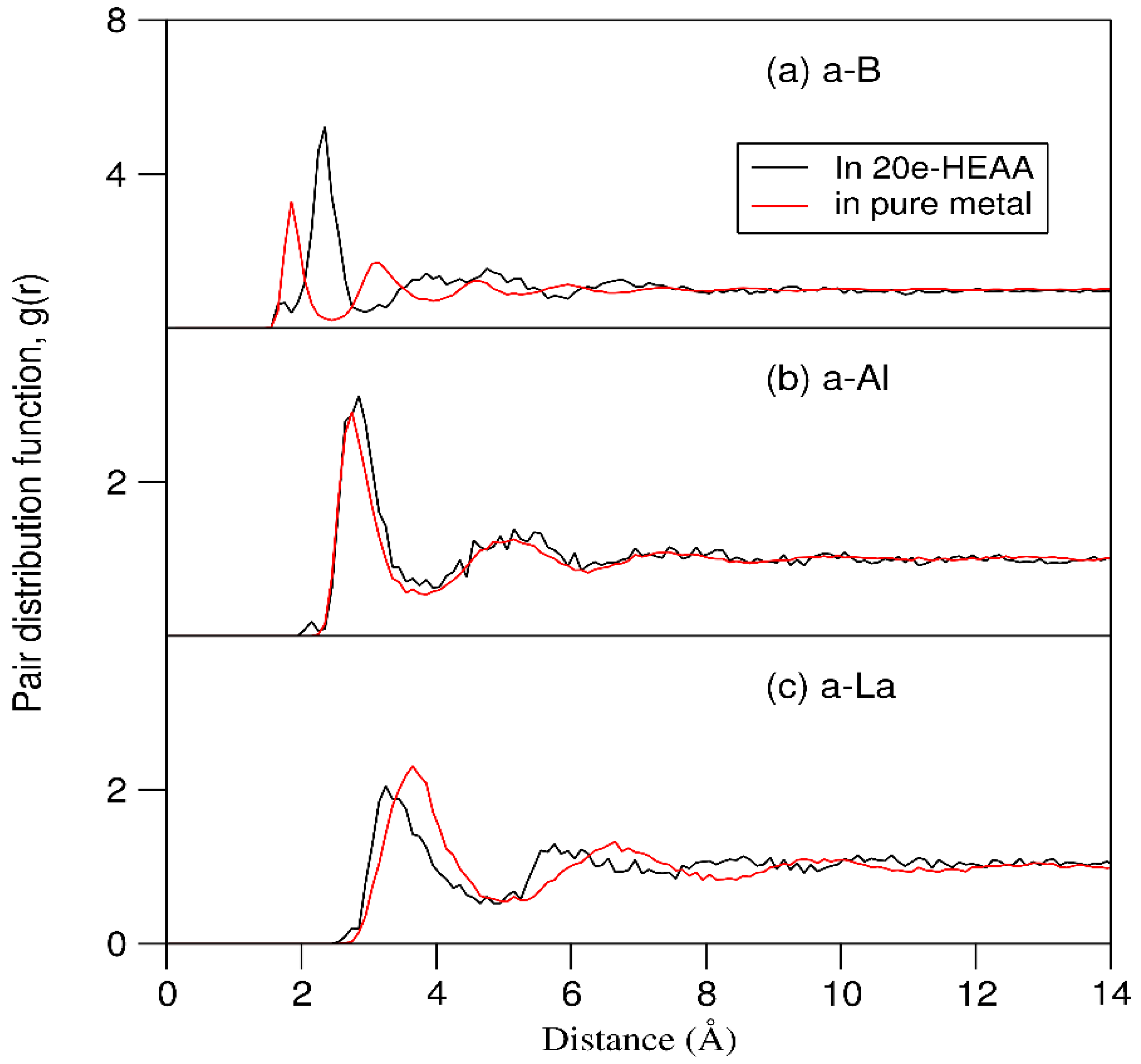

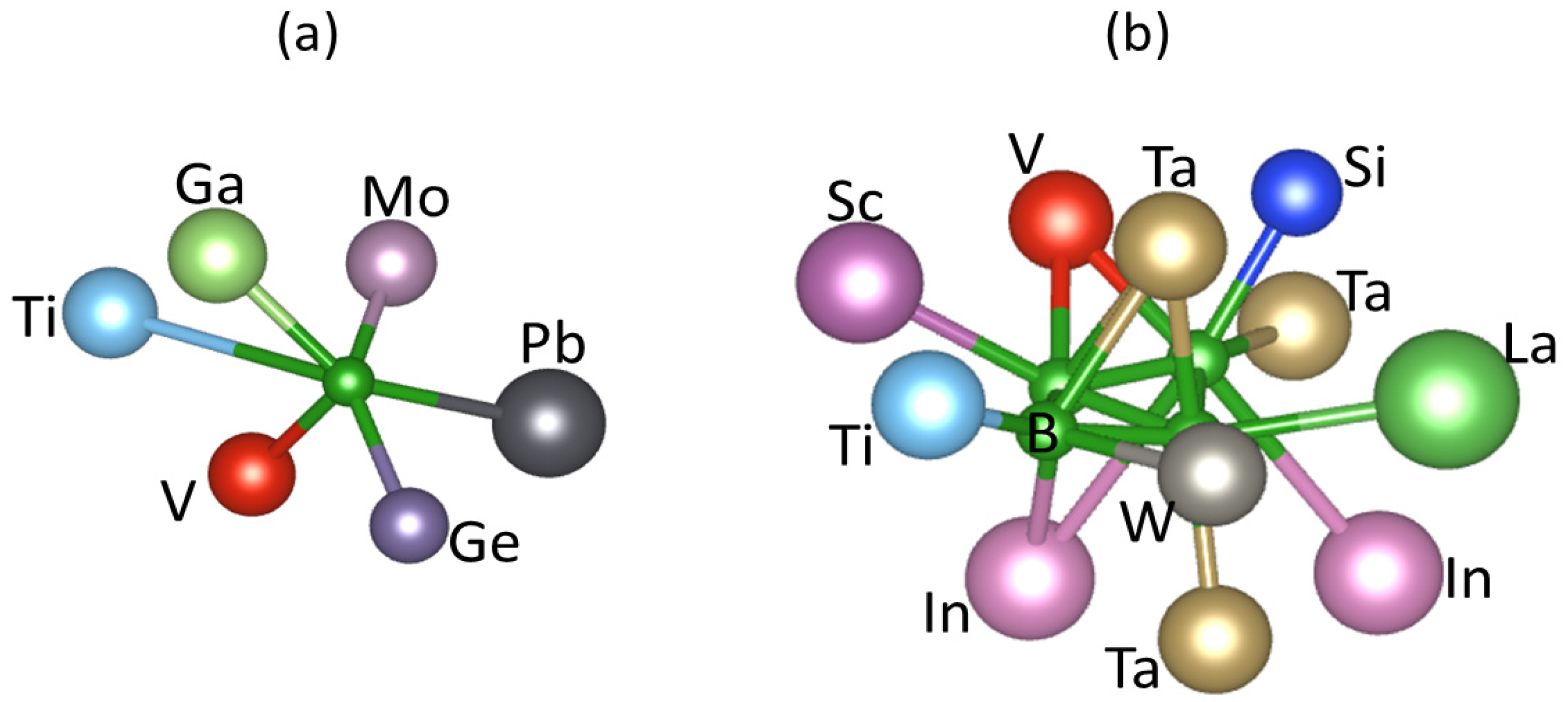

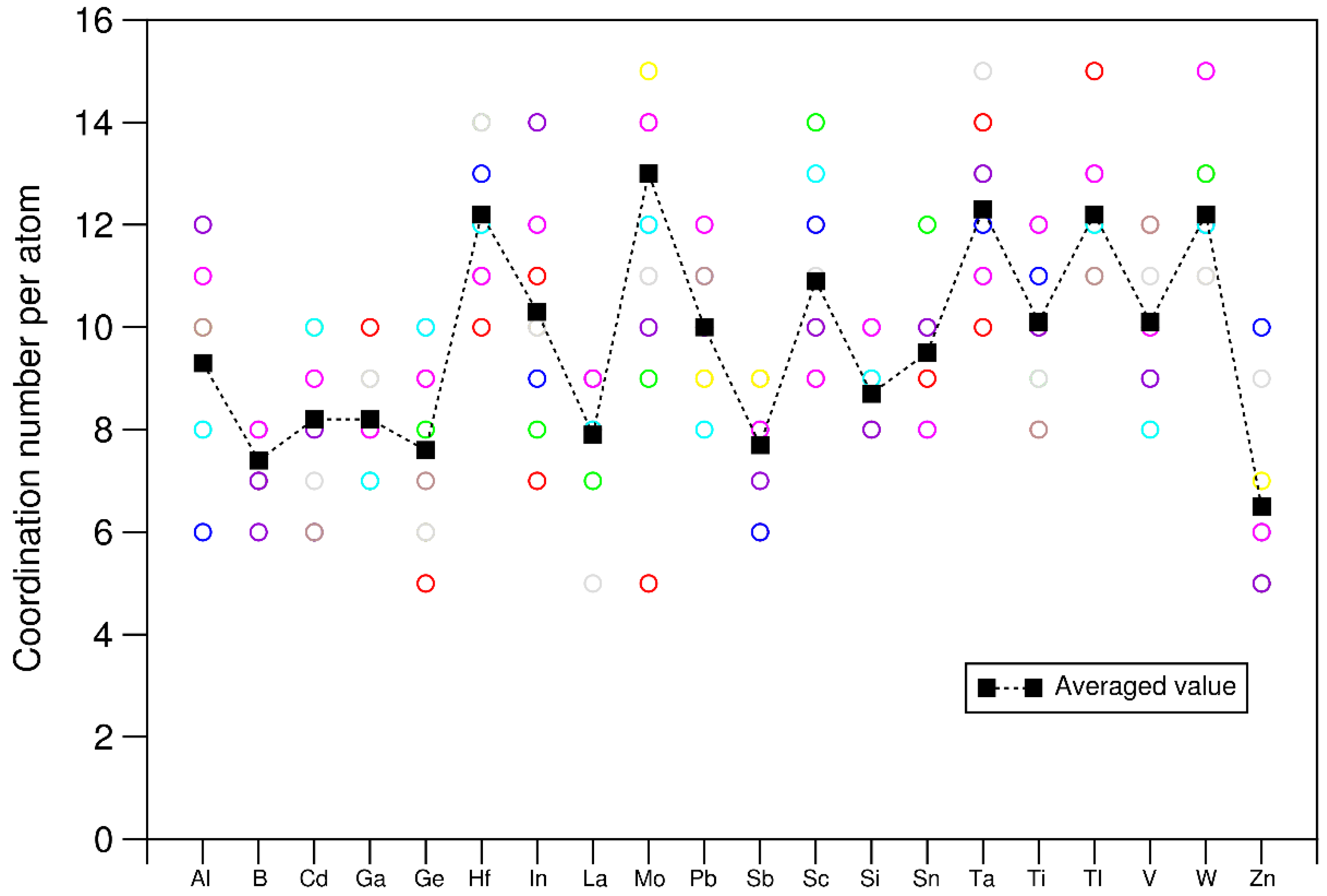

4.1. Structural properties of the 20e-HEAs

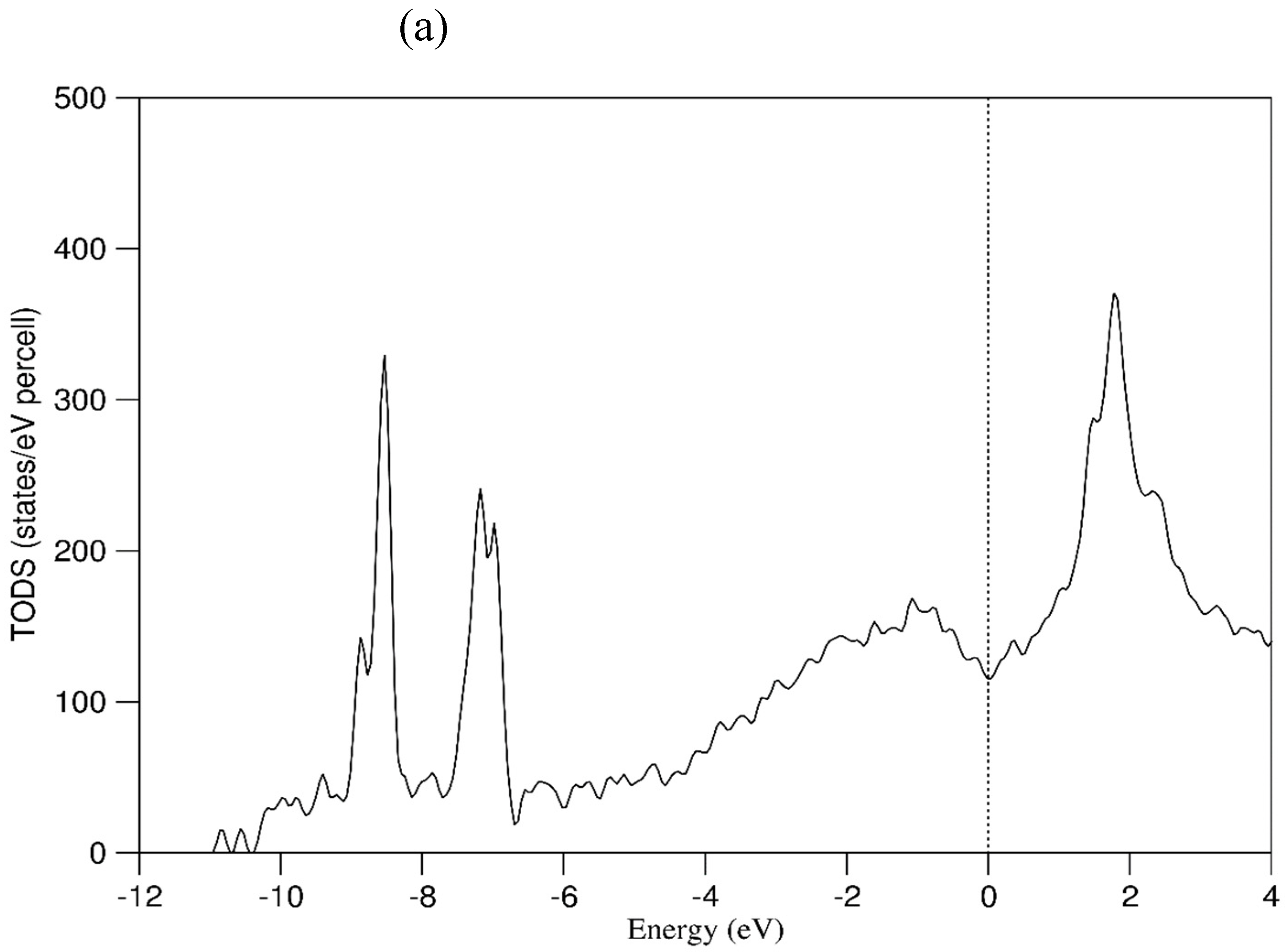

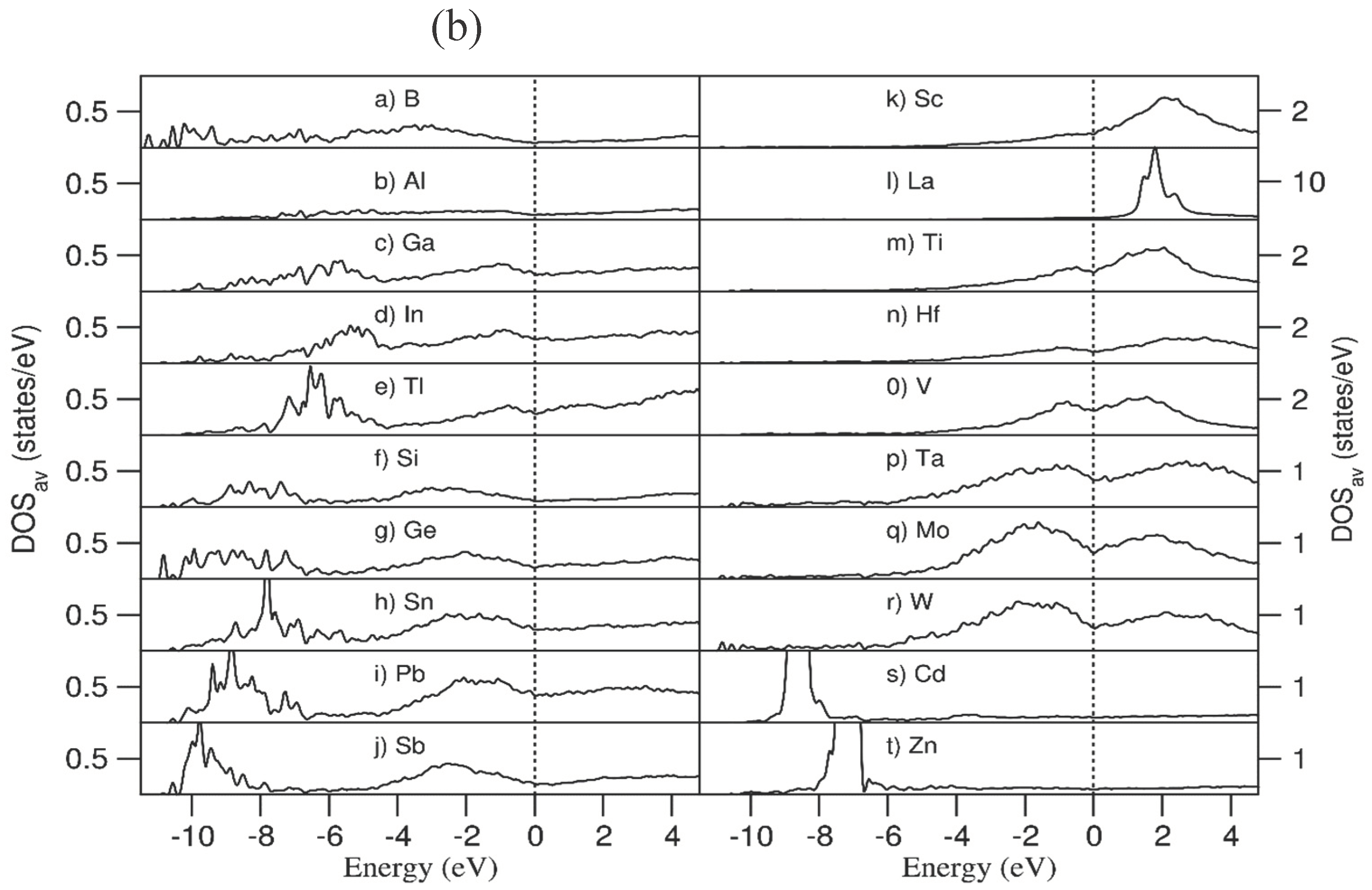

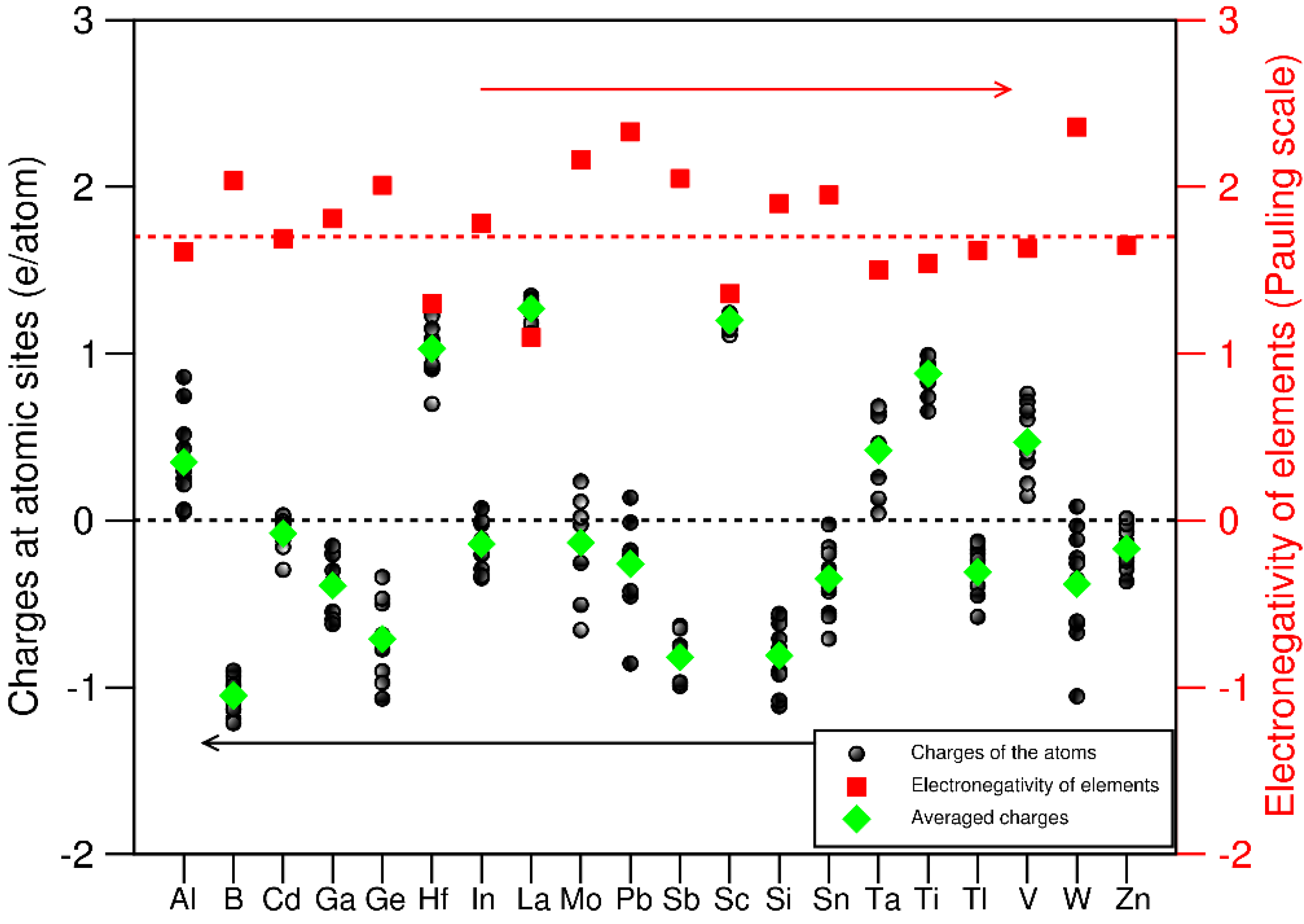

4.2. Electronic properties of the 20e-HEAAs

4.3. Discussions: Perspectives of MC-HEAAs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atherton, J. Declaration by the metals industry on recycling principles, Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2007, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, C. Steel’s recyclability: demonstrating the benefits of recycling steel to achieve a circular economy, Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1658–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.; Hultink, E. The Circular Economy – A new sustainability paradigm? J. Cleaner Production, 2017, 143, 757-768.

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Pieroni, M. P. P.; Pigoss, D. C. A.; Soufani, K. Circular business model: A review, J. Cleaner Production, 2020, 277, 123741.

- Reuter, M. A.; van Schaik, A.; Gutzmer, J.; Bartie, N.; Abadías-Liamas, A. Challenges of the circular economy: A materials, Metallurgical, and Product design perspective, Ann. Rev. Mater. Res., 2019, 49, 253-274.

- L. F. Zhang, L. F.; J. W. Gao, J. W.; L. Nana, L.; W. Damoah, W.;and D. G. Robertson, D. G. Removal of iron aluminum: A review, Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2012, 33, 99–157.

- Raabe, D.; Ponge, D.; Uggowitzer, P. J.; Roscher, M.; Paolantonio, M.; Liu, C. L.; Antreckowitsch, H.; Kozenschnik, E.; Seidmann, D.; Gault, B.; De Geuser, F.; Deschamps, A.; Hutchinson, C.; Liu, C. H.; Li, Z. M.; Prangnell, P.; Robson, J.; Shanthraj, P.; Cakili, S.; Sinclair, C.; Pogatscher, S. Making sustainable aluminum by recycling scrap: The science of ’dirty alloys’, Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 128, 100947.

- Villalba, G.; Segarra, M.; Fernández, A. I.; Chimenos, J. M.; Espiell, F. A proposal for quantifying the recyclability of material, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2022, 37, 39-53.

- Yeh, J. W.; Chen, S. K.; Lin, S. J.; Gan, J. Y.; Chin, T. S.; Shun, T. T.; Tsau, C. H.; Chang, S. Y. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: novel alloy design concepts and outcomes, Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303.

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I. T. H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A. J. B. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys, Mater. Sci. Engin. A, 2004, 375-377, 213-281.

- Cantor, B. Multicomponent high-entropy cantor alloys, Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 120, 100754. [Google Scholar]

- George, E. P.; Raabe, D.; Ritchie, R. O. High-entropy alloys, Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D. B.; Senkov, O. N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts, Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448-511.

- Chen, M. W. A brief overview of bulk metallic glasses, NPG Asia Mater. 2011, 3, 82-90.

- Sastry, S. The relationship between fragility, configurational entropy and the potential energy landscape of glass-forming liquids, Nature, 2001, 409, 164–167.

- Novák, L.; Potocký, L.; Kisdi-Kosozó, É.; Lovas, A.; Takács, J. Induced magnetic anisotropy of Fe-X-B glassy alloys, J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1984, 46, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, A. L. Materials science—confusion by design, Nature, 1993, 366, 303–304.

- Fowler, R.; Guggenheim, E. A. Statistical Thermodynamics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1960.

- Henchman, R. H. Partition function for a simple liquid using cell theory parameterized by computer simulation, J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 400–406. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, C.; Guo, S.; Luan, J. H.; Shi, S. Q.; Liu, C. T. Entropy-driven phase stability and slow diffusion kinetics in an Al0.5CoCrCuFeNi high entropy alloy, Intermetallics, 2012, 31, 165–172.

- Senkov, O. N.; Miracle, D. B.; Chaput, K. J.; Couzinie, J.-P. Development and exploration of refractory high entropy alloys—A review, J. Mater. Res., 2018, 33, 3092–3128.

- Zeng, Q. S.; Sheng, H. W.; Ding, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, W. G.; Jiang, J.-Z.; Mao, W. L.; Mao, H.-K. Long-range topological order in metallic glass, Science, 2011, 332, 1404–1406.

- Wei, R.; Tao, J.; Sun, H.; Chen, C.; Sun, G. W.; Li, F. S. Soft magnetic Fe26.7Co26.7Ni26.6Si9B11 high entropy metallic glass with good bending ductility, Mater. Lett., 2017, 197, 87-89.

- Tong, Y.; Qiao, J. C.; Zhang, C.; Pelletier, J. M.; Yao, Y. Mechanical properties of Ti16.7Zr16.7Hf16.7Cu16.7Ni16.7Be16.7 high-entropy bulk metallic glass, J. Non-crystal. Solids, 2016, 452, 57-61.

- Luan, H. W.; Zhang, X.; Ding, H. Y.; Zhang, F.; Luan, J. H.; Jiao, Z. B.; Yang, Y.-C.; Bu, H. T.; Wang, R. B.; Gu, J. L.; Shao, C. L.; Yu, Q.; Shao, Y.; Zeng, Q. S.; Chen, N.; Liu, C. T.; Yao, K.-F. High-entropy induced a glass-to-glass transition in a metallic glass, Nature Commun., 2022, 13, 2183.

- Cao, P. Y.; Ni, X. D.; Tian, F. Y.;. Varga, L. K.; Vitos, L. Ab initio study of AlxMoNbTiV high-entropy alloys, J. Phys. Condes. Matter, 2015, 27, 075401.

- Li, Z. M.; Körmann, F.; Grabowski, B.; Neugebauer, J.; Raabe, D. Ab initio assisted design of quinary dual-phase high-entropy alloys with transformation-induced plasticity, Acta Mater., 2017, 136, 262-270.

- Yang, S.G.; Liu, G.C.; Zhong,Y. Revisit the VEC criterion in high entropy alloys (HEAs) with high-throughput ab initio calculations: A case study with Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Ni system, J. Alloys Compds., 2022, 916 ,165477.

- Parmar, A. D. S.; Ozawa, M.; Berthier, L. Ultrastable metallic glasses in Silico, Phys. Rev. Lett., 2020, 125, 085505.

- Callister, W. D.; Rethwisch, D. G. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction, (10th ed.), Wiley, 2018.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y. J.; Lin, J. P.; Liang, G.; Liaw, P. Solid-solution phase formation rules for multi-component alloys, Adv. Engin. Mater., 2008, 10, 534-538.

- Guo, S.; Liu, C. T. Phase stability in high entropy alloys: Formation of solid-solution phase or amorphous phase, Prog. Nat. Sci: Mater. Intern., 2011, 21, 433-446.

- Takeuchi, A.; Inoue, A. Classification of bulk metallic glasses by atomic size difference, heat of mixing and periodic of constituent elements and its application to characterization of the main alloying element, Mater. Trans., 2005, 46, 2817-2829.

- Arblaster, J. Selected values of the crystallographic properties of the elements, ASM International, Materials Park, Ohio, 2018.

- Pauling, L. The Nature of the Chemical Bond, Cornell University Press, Ithaca/New York, 1960.

- Timberlake, K. C. Chemistry: An introduction to general, Pearson, London, England, 2014.

- Fang, C. M.; de Wijs, G. A.; Orhan, E.; de With, G.; de Groot, R. A.; Hintzen, H. T.; Marchand, R. Local structure and electronic properties of BaTaO2N with perovskite-type structure, J. Phys. Chem. Solids, 2003, 64, 281-286.

- Brostow, W.; Hagg Lodbland, H. E. Materials: Introduction and Applications, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2017.

- Hintzsche, L. E.; Fang, C. M.; Watts, T.; Marsman, M.; Jordan, G.; Lamers, M. W. P. E.; Weeber, A. W.; Kresse, G. Density functional theory study of the structural and electronic properties of amorphous silicon nitrides: Si3N4-x:H, Phys. Rev. B, 2012, 86, 235204.

- Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A. Crystal structure and pair potentials: A molecular -dynamics study, Phys. Rev. Lett., 1980, 45, 1196-1999.

- Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A.; Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method, J. Applied Phys., 1981, 52, 7182-7190.

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B, 1994, 49, 14251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set, Comp. Mater. Sci., 1996, 6,15-50.

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method, Phys. Rev. B, 1994, 50, 17953-79.

- Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple, Phys. Rev. Lett., 1996, 77, 3865-3868.

- Fang, C. M.; van Huis, M. A.; Sluiter, M. H. F.; Zandbergen, H. W., Stability, structure and electronic properties of γ-Fe23C6 from first-principles study, Acta Mater., 2010, 58, 2968-2977.

- Monkhorst, H. J.; Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin zone integrations, Phys. Rev. B, 1976, 13 , 5188-5192.

- Wang, X. L.; Tan, S.; Yang, X.-Q.; Hu, E. Y. Pair distribution function analysis: Fundamentals and application to battery materials. Chin. Phys. B, 2020, 29, 028802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halet, J.-F.; in Contemporary Boron Chemistry, M.G. Davidson, A.K. Hugues, T.B. Marder, K. Wade (Eds.), Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, 2000.

- Brown, I. D.; Shannon, R. D. Empirical Bond-Strength-Bond-Length Curves for Oxides, Acta Crystallographica, A, 1973, 29, 266-282.

- Brown, I. D. The Chemical Bond in Inorganic Chemistry: The Bond Valence Model, Oxford University Press, 2002. ,.

- Kittel, C. Introduction to Solid State Physics, 8th ed. Wiley, 2004. ,.

- Fang, P. X. W.; Nihtianov, S.; Sberna, P.; Fang, C. M. Interfaces between crystalline Si and amorphous B: interfacial interactions and charge barriers, Phys. Rev. B, 2021, 103, 075301.

- Wyckoff, R. W. G. The structure of Crystals, 2nd Ed., Reinhold Publishing Corporation, New York, USA, 1935. ,.

- Bader, R. F. W. A. A quantum-theory of molecular-structure and its applications, Chem. Rev., 1991, 91, 893-928.

- Bader, R. F. W. A bonded path: A universal indicator of bonded interactions, J. Phys. Chem. A, 1998, 102 (1998) 7314-7323.

- Henkelman, G.; Arnaldsson, A.; Jónsson, H. A fast and robust algorithm for Bader decomposition of charge density, Comp. Mater. Sci., 2006, 36, 254-360.

- Kelton, K. F.; Greer, A. L. Nucleation in condensed matter: applications in materials and biology, Pergamon Materials Series, Elsevier Ltd. Oxford/Amsterdam, 2010. 2010.

- Turnbull, D. Kinetics of heterogeneous nucleation, J. Chem. Phys., 1950, 18, 198-203.

- Suryanarayana, C.; Inoue, A. Iro-based bulk metallic glasses, Intern. Mater. Rev., 2013, 58, 131-166.

- Descristofaro, N.; Freilich, A.; Fish, G. Formation and magnetic properties of Fe-B-Si metallic glasses, J. Mater. Sci., 1982, 17, 2365-70.

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.-T.; Fan, Z. Oxidation of aluminium alloy melt and inoculation by oxide particles, Trans. Indian Inst. Met., 2012, 65, 653-661.

- Fang, C. M.; Fan, Z. Atomic ordering at the interfaces between liquid aluminum and polar AlN{0 0 0 1} substrates, Metal. Mater. Trans. A, 2022, 53, 2040-2047.

- Fan, Z. Heterogeneous nucleation, grain initiation and grain refinement of Mg-alloys, Proc. The 11th international conference on magnesium alloys and their applications, 24-27 July 2018, Beaumont Estate, Old Windsor, UK. Ed. By Z. Fan and C. Mendis, 2018.

- Fang, C. M.; Fan, Z. Ab initio molecular dynamics investigation of prenucleation at liquid- Metal/Oxide Interfaces: An overview, Metals, 2022, 12, 1618.

- Stoner, E. C. Collective electron ferromagnetism, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A, 1938, 165, 272-414.

| M | Latt. [34] | Mass (Da) |

VEC(e/at.) E. C. [32] |

r0(Å) [32,34] |

χ(P.u.) [32] |

Tm [34] (K) |

ΔHmix(i) (kJ/mol) |

Selected Δmix(AB)[33] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Rho. | 10.811 | 3 2s2 2p1 |

0.820 | 2.04 | 1300 | -13.82 | B-: Hf(-66), Ti(-58), Sc(-55); B-: Tl(27), Pb(31), Sb(23), In(18). |

| Al | FCC | 26.981 | 3 3s2 3p1 |

1.432 | 1.61 | 933.5 | -11.24 | Al-: Hf(-39), Sc(-38), La(-38); Al-: Tl(11), Pb(10), In(7) |

| Ga | Orth. | 68.723 | 3 4s2 4p1 |

1.393 | 1.81 | 303 | -8.08 | Ga-: La(-41), Sc (-38), Hf(-34); Ga-: Mo(6), B(6), Tl(6), Pb(5). |

| In | Tetra. | 114.820 | 3 5s2 5p1 |

1.659 | 1.78 | 430 | +0.39 | In-: La(-39), Sc(-30), Hf(-18); In-: W(38), Mo(33), B(18). |

| Tl | Hex. | 204.380 | 3 6s2 6p1 |

1.716 | 1.62 | 577 | +5.66 | Tl-: La(-38), Sc(-28), Hf(-11); Tl-: W(52), Ta(24), Mo(46), B(27). |

| Si | FCC | 28.085 | 4 3s2 3p2 |

1.153 | 1.90 | 1690 | -31.08 | Si-: Hf(-77), Sc(-74), La(-73); Si-: Tl(-4), Pb(-2) |

| Ge | FCC | 72.610 | 4 4s2 4p2 |

1.240 | 2.01 | 1211 | -25.18 | Ge-: La(-73.5),Sc(-69.5),Hf(-65.5); Ge-: B(-0.5) |

| Sn | Tetra. | 118.710 | 4 5s2 5p2 |

1.620 | 1.96 | 505 | -5.66 | Sn-: La(-53), Sc(-45), Hf(-35); Sn-: W(27), B(18), Mo(20). |

| Pb | FCC | 207.200 | 4 6s2 6p2 |

1.750 | 2.33 | 600.6 | +2.24 | Pb-: La(-51), Sc(-40), Hf(-23); Pb-: W(49), B(30), Mo(42). |

| Sb | Trig. | 121.750 | 5 6s2 6p3 |

1.453[2] | 2.05 | 904 | -10.34 | Sb-: La(-71), Sc(-61), Hf(-50); Sb-: W(25), B(18), Mo(17). |

| Sc | Hex. | 44.956 | 3 3d1 4s2 4p0 |

1.641 | 1.36 | 1814 | -25.24 | Sc-: Si(-74), Ge(-69.5), Sb(-61); Sc-: Ta(16), Mo(11), W(9), Ti(8) |

| La | Hex. | 138.900 | 3 4f0 5d1 6s2 6p0 |

1.879 | 1.10 | 1191 | -22.97 | La-: Ge(-73.5), Si(-73), Sb(-71); La-: Ta(33), W(32), Mo(31), |

| Ti | HCP | 47.880 | 4 3d2 4s2 4p0 |

1.462 | 1.54 | 1943 | -15.45 | Ti-: Si(-66), B(-58), Ge(-51.5) Ti-: La(20), Sc(8), Tl(2). |

| Hf | Hex. | 178.490 | 4 5d2 6s2 6p0 |

1.578 | 1.30 | 2502 | -23.71 | Hf-: Si(-77), B(-66), Ge(-65.5); Hf-: La(15), Sc(5), Ta(3). |

| V | BCC | 50.941 | 5 3d3 4s2 4p0 |

1.316 | 1.63 | 2201 | -3.97 | V-: Si(-48), B(-42), Ge(-31.5); V-: Tl(22), La(22), Pb(15), In(12). |

| Ta | BCC | 180.948 | 5 5d3 6s2 6p0 |

1.430 | 1.50 | 3293 | -5.50 | Ta-: Si(-56), B(-54), Ge(-37.5); Ta-: La(33), Tl(24), Sc(16) |

| Mo | BCC | 95.940 | 6 5d4 6s2 6p0 |

1.363 | 2.16 | 2895 | +7.71 | Mo-: Si(-35), B(-34), Ge(-13.5) Mo-:Tl(46), Pb(42), In(33) |

| W | BCC | 183.850 | 6 6d1 7s2 7p0 |

1.367 | 2.36 | 3687 | +10.50 | W-: Si(-31), B(-31), Ge(-7.5); W-: Tl(52), Pb(49), In(38). |

| Zn | HCP | 65.390 | 12 3d10 4s2 4p0 |

1.395 | 1.65 | 693 | -4.82 | Zn-: Sc(-29), La(-31),Hf(-24) Zn-: W(15), Tl(6), Pb(5); |

| Cd | Hex. | 112.411 | 12 4d10 5s2 5p0 |

1.568 | 1.69 | 594 | -0.27 | Cd-: La(-36), Sc(-30), Hf(-19); Cd-: W(33), Mo(28), B(13). |

| Av. dev. |

- - |

103.739 |

4.8 - |

1.462 δ:14.6% |

1.77 Δχ:0.324 |

1463 - |

-9.52 - |

s, p elements prefer: La, Hf, Sc; d-elements prefer: Si, B, Ge; Zn and Cd prefer La, Sc and Hf. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).