1. Introduction

The 2015 Paris Agreement established a global framework to limit the increase in global temperatures to well below 2°C, with a preferred target of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. To achieve this goal, countries commit to curbing the growth of greenhouse gas emissions as quickly as possible, followed by significant and sustained reductions. These efforts are guided by the best available scientific evidence, as well as considerations of economic and social feasibility [8]. The impacts of climate change, which are increasing globally, are also being recognized in Oman [8]. The Sultanate of Oman, in its Second Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), which extends until 2030, outlines the current and projected effects of climate change, as well as its planned mitigation and adaptation strategies submitted to the UN. Oman has set a goal to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 7% by 2030 [5].

Research by El Kenawy et al. [8] has documented an increase in both the frequency and intensity of droughts in Oman over the past four decades, particularly since 1997/98. Over the past forty years, the average temperature in Oman increased by 0.35 degrees Celsius [9], leading to an increase in the incidence and severity of droughts. Therefore, it is crucial to identify and address the root causes of droughts through a comprehensive review of existing policies and the implementation of effective adaptation strategies by relevant stakeholders, including government agencies, local communities, and researchers. El Kenawy et al. [6] stated that there is a clear lack of studies related to drought and water shortages in various regions of Oman, calling for more research in this field. Oman is considered an area of dry to semi-arid nature. The average annual rainfall in 2020 is 123 mm, which exacerbates this phenomenon [7].

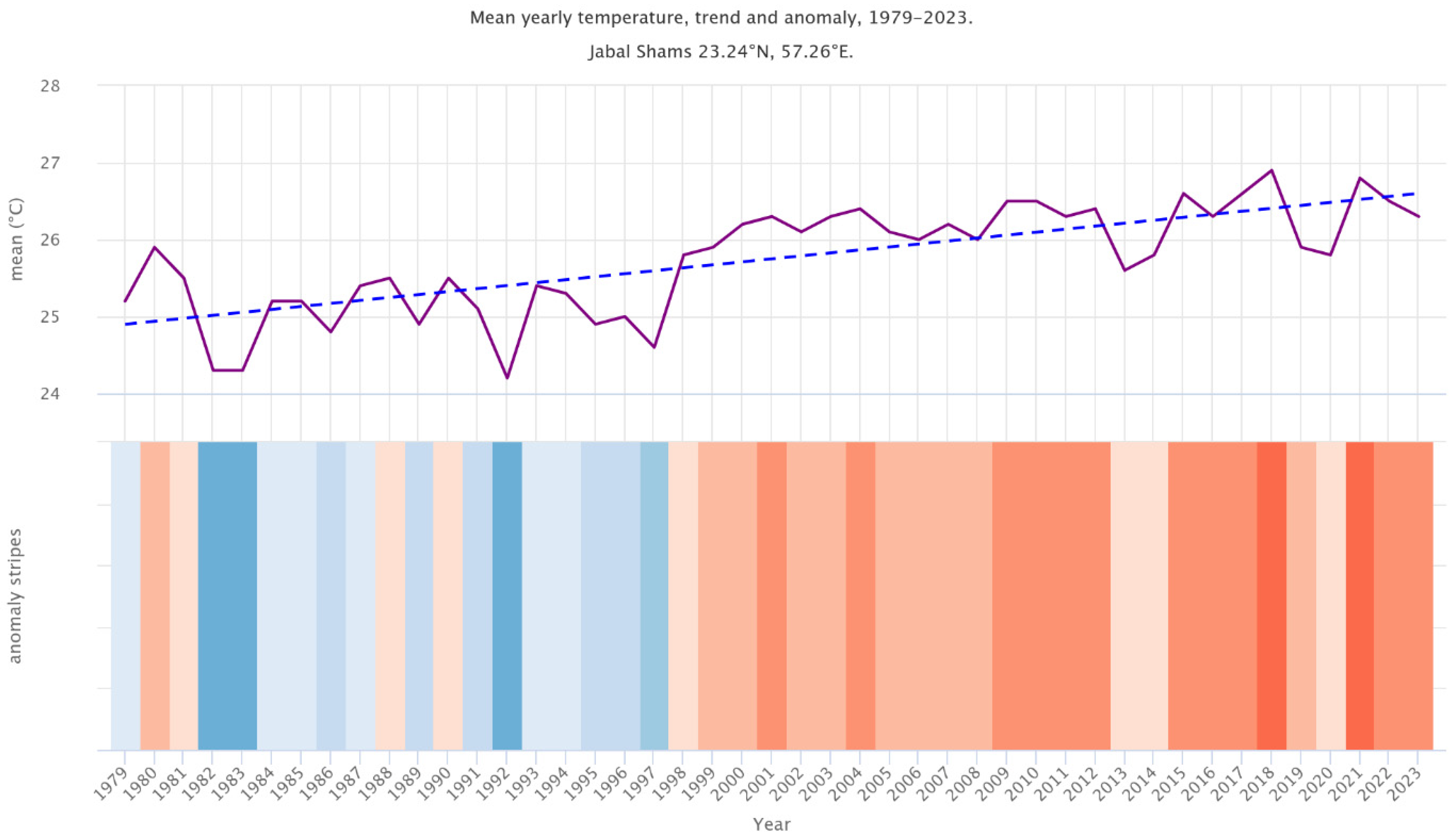

Jabal Shams and Jabal Al Akhdar, extensions of the Hajar mountain chain in Al Dakhiliyah Governorate, face severe water shortages compared to previous years. This region suffers severely from climate change, high temperatures, and unstable precipitation patterns, which exacerbate the drought phenomenon [9]. Luedeling and Buerkert [8] describe climatic conditions as extremely dry in northern Oman. Mohammed Al-Kalbani, Martin Price, and Abahussain [8] conducted a vulnerability assessment to understand the impact of climate change on both the ecosystem and local people in the mountainous areas of Oman. One of the results of their study shows an increase in temperature by 0.27 degrees Celsius per decade and a decrease in precipitation by 9.42 mm per decade from 1979 to 2012. The average rainfall in this region reached 296.7 mm during the same period, as measured at the meteorological station located in Jabal Al Akhdar in 2012. One of the main indicators for understanding climate change is changes in temperature and rainfall [6].

Figure 1, sourced from Meteoblue [7], illustrates a warming trend over the past four decades in the Jabal Shams region. The upward trajectory of the temperature line highlights a consistent overall increase, with temperatures after the year 2000 exceeding the historical average. This pattern serves as a clear indication of climate change in the region.

One of the contributing factors to the ongoing climate change is the increasing pressure on freshwater resources, especially in areas with an arid to semi-arid climate, which has caused water scarcity [10]. Water scarcity is defined as the annual per capita share of freshwater being less than 1,000 cubic meters per year, while absolute water scarcity is defined as an annual per capita share of less than 500 cubic meters per person, covering domestic, agricultural, industrial, and other needs. Oman faces absolute water scarcity, which results in an increase in absolute water stress, as rising temperatures and decreased rainfall exacerbate this problem, presenting a challenge for decision-makers in Oman [10]. These challenges have had a direct impact on the residents of the Hajar Mountains, particularly the areas of Jabal Al-Shams, such as Dar Al-Sawda, Khatim, and Karb. These areas are relatively small in terms of population and size, relying primarily on livestock raising and agriculture. However, this region is also surrounded by impressive tourist destinations that attract many visitors annually, leading to the construction of multiple international resorts around it [12].

It is also considered a national reserve called “Starlights,” aimed at reducing light pollution to enable stargazing at night [9]. However, current studies indicate the displacement of residents from these areas to major cities like Nazwa and Muscat due to economic reasons, lack of services, and the effects of climate change. These challenges necessitate a comprehensive understanding of the region’s climate and the development of sustainable solutions to ensure the well-being of its inhabitants. These factors have impacted water availability, leading to decreased agricultural and livestock production [5]. In recognition of these challenges, a collaborative research project was launched in March 2022 between the Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg in Germany and the German University of Technology in Oman, under the title “Climate Change and Sustainable Resource Management in Oman (Rosin-Oman) - II.” This project, funded by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), aims to study the climatic, social, and economic conditions and challenges in three regions: Dar Al Souda, Karb, and Khatim in Jebel Shams.

1.1. Objectives

The main objective of this project is to develop a sustainable integrated resource management plan for the “Green Village” in Dar as Sawda, addressing critical challenges in agriculture, wastewater treatment, and renewable energy. The project aligns with Oman Vision 2040 and contributes to selected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Especially, the goals no poverty (targets 1.1, 1.4), clean water and sanitation (targets 6.3, 6.4; a, b), clean and affordable energy (target 7.2), and sustainable communities (target 11.b) have been identified as relevant (SDGs, 2015). This project aims to improve water security, food production, and energy access while mitigating the impacts of climate change.

1.2. Dar as Sawda as a Case Study

Dar Al Sawda is a village located in Jabal Shams, within the Wilayat of Al Hamra in the Al Dakhiliyah Governorate of the Sultanate of Oman. Jabal Shams, meaning “Mountain of the Sun,” derives its name from being the first point to witness sunrise and the last to see sunset in the region. The area is characterized by a unique climate, with moderate summer temperatures averaging around 25°C and cold winters where temperatures drop below 7°C, occasionally accompanied by snowfall. These climatic conditions are primarily attributed to its elevation, which reaches up to 3,000 meters above sea level [14]. Dar Al Sawda (23.24° N, 57.19° E) is situated in the Jabal Shams region of Oman, approximately 240 kilometers from the capital city of Muscat and 36 kilometers from the town of Al Hamra. Located within the Ad Dakhiliya Governorate, this village stands out for its remote yet striking natural environment, which makes it a significant cultural and ecological site in Oman..

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive and integrated methodology was utilized to achieve the objectives and appropriately present the findings of this study. The methodology combined qualitative interviews, focus group discussions, and stakeholder meetings to gather in-depth information necessary for the Green Village project. This scientific paper reports on a field research trip conducted by a team of researchers and students from Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg (BTU) on March 16, 2022, to the Al Jabal Al Akhdar mountain range in Oman.

Qualitative interviews were conducted to explore the challenges faced by the community in detail and to gather additional information on issues such as water scarcity, renewable energy adoption, and waste management that were not extensively covered in previous research and studies [3,12]. This approach was chosen because it allowed for deeper conversations and richer insights. The study is considered qualitative rather than quantitative because the interviews were lengthy and involved a small group of carefully selected participants. These participants included village representatives, government decision-makers, and experts from companies specializing in innovative and sustainable solutions for the unique challenges of this region [3,11]. The questions and guidelines used during the interviews are provided in

Appendix A. Additionally, focus group discussions with key village representatives provided a platform for more comprehensive dialogue. These interviews and focus group discussions form the basis of this research, allowing for the emergence of unplanned but crucial information, which is supported by Kvale and Brinkmann in their structured framework for conducting interviews [7] and by Rubin and Rubin in their seven-step Responsive Interviewing Model [13]. On the other hand, this type of interview may be considered unreliable, given that some of the respondents’ answers may be inaccurate in order to serve their personal interests. This approach is supported by Herbert J. Rubin and Irene S. Rubin’s critique of positivism, where they assert that quantitative data-gathering methods, such as surveys, “intellectually dominate” respondents, highlighting the limitations of such methods for this type of research [13]. The interviews included village representatives and key decision-makers in government and specialized companies, thus capturing a diverse range of perspectives.

The interviews were conducted on March 16, 2022, in three villages in Jabal Al-Akhdar: Al-Khaytam (23.19 N, 57.12 E), Karb (23.27 N, 57.21 E), and Dar Al-Sawda (23.24 N, 57.19 E). The official spoken language in these villages is Arabic, and to overcome the language barrier, a group of scholars from German University of Technology in Oman (GUtech) assisted with translation between Arabic and English. Interviews were used to collect information on current living conditions, population size, general awareness about climate change, renewable energy, and waste management, as well as current land use practices and attitudes towards tourism. Due to cultural reasons, interviews were conducted in two groups, males and females. These interviews took place in family homes or in communal spaces used by the residents for meetings, known as the “Majlis”. Incorporating cultural norms into research interviews is crucial for several reasons: respect and sensitivity, building trust, improving data quality, and ethical considerations. As Bahira Sherif-Trask stated, “Without proper cultural sensitivity, misunderstandings or (worse) racist attitudes can arise that can jeopardize the progress of your research or, at an extreme level, end your project” [2]. This highlights the importance of cultural awareness to prevent negative outcomes and ensure the smooth progress of research projects.

In addition, a stakeholder meeting was held on March 20, 2022, where the proposed Green Village project was presented. The stakeholders included regional leaders from the three selected villages. A third component of this research involved a direct consultation with the German company Bauer Nimr in Muscat, which specializes in biological wastewater treatment technologies. Their expertise was sought regarding the feasibility of implementing their ReedBox® system in the study area [16].

3. Results and Discussion

The results of the interviews, summarized in Table 2.1, provide critical insights into the Dar Al-Sawda region, selected as the case study for this research. This region was chosen due to its relatively large population, consisting of approximately 120 residents living in 12 households. Focusing on this area ensures that the study benefits the maximum number of citizens, aligning with the objectives of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1: No Poverty (specifically targets 1.1 and 1.4) and SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities (target 11.3) (UN, 2015). A detailed list of the SDGs referenced is included in

Table A2. The community faces significant challenges with water availability, largely due to inconsistent rainfall patterns. The local well often holds limited water, making a reliable supply a persistent issue. Despite these challenges, residents of Dar Al-Sawda exhibit a strong understanding and belief in the benefits of renewable energy. Their adoption of solar batteries highlights their awareness of sustainable practices, distinguishing them from other villages in the region.

The sewage management system in the village relies on underground tanks for individual households. When these tanks reach capacity, sewage trucks are employed to remove the waste. However, some tanks lack proper fortification at the base, leading to sewage leakage into the ground. This issue not only contributes to pollution but also risks contamination of water wells. General waste is collected daily in large government-provided tanks located near clusters of homes. These are subsequently emptied by government trucks and transported to designated landfills for disposal. Electricity in the region is supplied by local electricity companies, while water is sourced from underground wells. Livestock farming serves as a primary source of income for many families. Residents sell meat, milk, and cheese in a local market in the main city of Al-Hamra. The region’s unique climate, characterized by cooler temperatures due to its mountainous location, supports the cultivation of various crops such as olives, pomegranates, peaches, apples, and others. Based on the analysis of these findings, this study proposes a comprehensive green village management plan. The plan will include targeted solutions addressing the identified challenges, framed within the context of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Table 1.

Information on living situation collected in interviews.

Table 1.

Information on living situation collected in interviews.

| Village |

No. of Houses

(People)

|

Water Availability |

Attitude Towards Renewable Energies |

| Al-Khitaym |

3 (approx. 30) |

Water sourced from transport tanks; lack of rainwater in recent years; little to no irrigation possible. |

Open to renewable energy but not very familiar; financial support needed. |

| Krub |

8 (approx. 80) |

Water from dam and transport tanks; only 12 liters per person per day reported. |

Skeptical; concerns about reliable supply. |

| Dar Al Sawda’a |

12 (approx. 120) |

Unreliable precipitation patterns; well occasionally provides limited water. |

Strongly supportive; already using solar battery. |

| Village |

No. of Houses (People) |

Water Availability |

Attitude Towards Renewable Energies |

3.1. Wastewater treatment

The ReedBox® technology, developed by Bauer Nimr, a German company based in Muscat specializing in natural-based wastewater treatment solutions, has been introduced for wastewater management in Dar Al Sawda. ReedBox offers an innovative approach to treating domestic wastewater and sludge sustainably and eco-friendly, using constructed wetlands. This biological treatment method employs natural components, including water, plants, microorganisms, filter media, and oxygen, without the use of chemicals. The system operates through gravity flow, which eliminates the need for pumps, significantly reducing energy consumption and CO₂ emissions. ReedBox is available in two sizes: a smaller unit designed to serve up to 30 people with a capacity of 7 m3 per day and a larger unit capable of treating 15 m3 per day, catering to up to 70 people [16]. These scalable solutions align with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 6.3 (Improving water quality), SDG 6.4 (Increasing water-use efficiency), and SDG 7.2 (Promoting renewable energy) [19]. The ReedBox system begins by collecting wastewater, which is introduced into the primary drainage system inside the box via a pump. The wastewater then flows into specially designed reed beds filled with gravel, where a combination of plants and microorganisms naturally decompose organic materials, absorb nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphate, and filter pollutants. The gravel and plant roots act as a natural filtration system, purifying the water as it passes through. This innovative method has been supported by research and similar studies, including works by Stefanakis [16], OnePetro [10], and Pala [11], highlighting its effectiveness and sustainability in wastewater treatment. The size of the ReedBox system depends on the average wastewater generated per person. Based on the standards provided by the Ministry of Regional Municipality and Water Resources, the per capita water demand in Oman is approximately 270 liters per capita per day (lpcd). Around 80% of this is converted to wastewater, equivalent to 216 lpcd, as highlighted by Al-Harthi in the study A Study on Usage of Treated Wastewater as Resource Management for the Sustainable Development of Al Amerat [1]. Using the document Reed Beds: Design, Construction, and Maintenance by Griggs and Grant [4], the following data are derived:

3.2. Agri Photovoltaic (PV)

Agri-photovoltaic (agri-PV) systems offer a promising solution for integrating renewable energy generation with agriculture, particularly in arid regions characterized by high solar irradiance, such as Oman. This study presents the design, simulation results, and performance analysis of a grid-connected agri-PV system implemented in Dar as Sawdah, Oman, focusing on its impact on energy production, water conservation, and agricultural productivity. PVSyst simulations, based on Meteonorm 8.1 data, predicted an annual energy yield of 147,708 kWh, with a specific yield of 1969 kWh/kWp/year. The summary results of the simulation are presented in

Table 3. The installed system comprises 300 photovoltaic modules (75.0 kWp nominal power) and five inverters, designed to power a ReedBox wastewater treatment system and support local energy needs, including the equivalent of 10 homes.

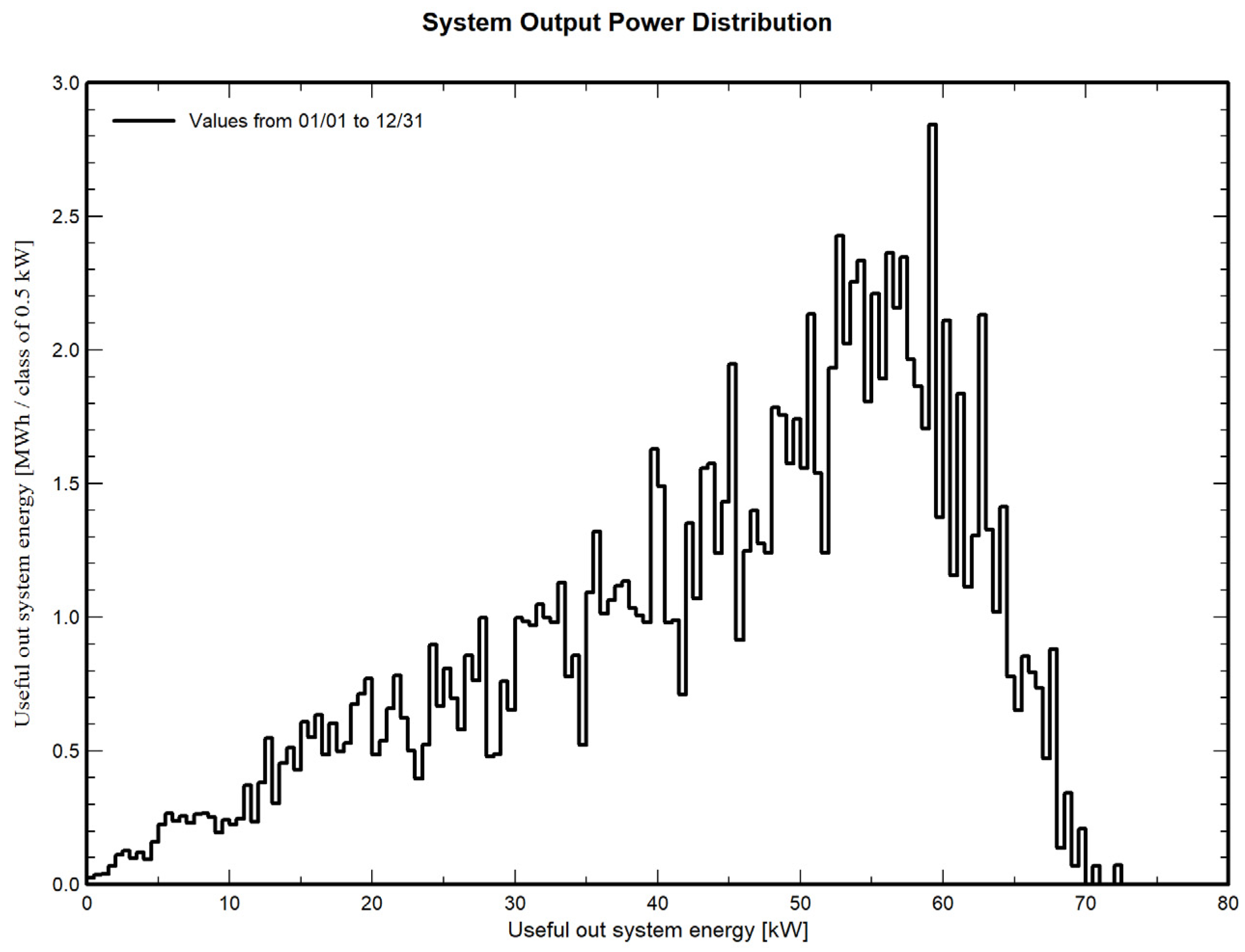

The energy output profile, consistent with minimal production at extreme values, peaks between 50–60 kW, as shown in

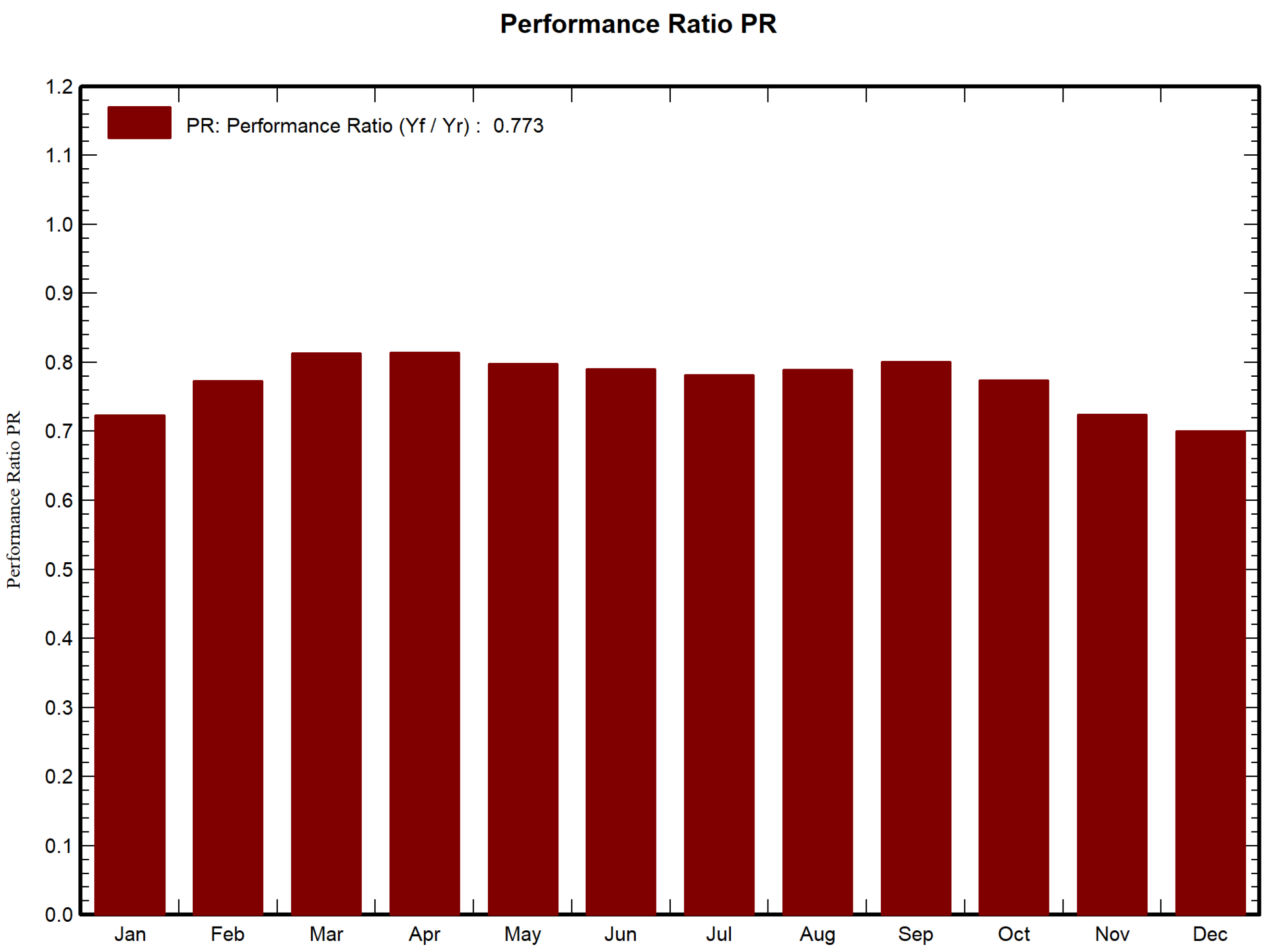

Figure 4. The system’s adaptability to seasonal variations is reflected in its performance ratio (PR), which averages 85.24% annually, with monthly variations ranging from 0.700 in December to 0.814 in April, as depicted in

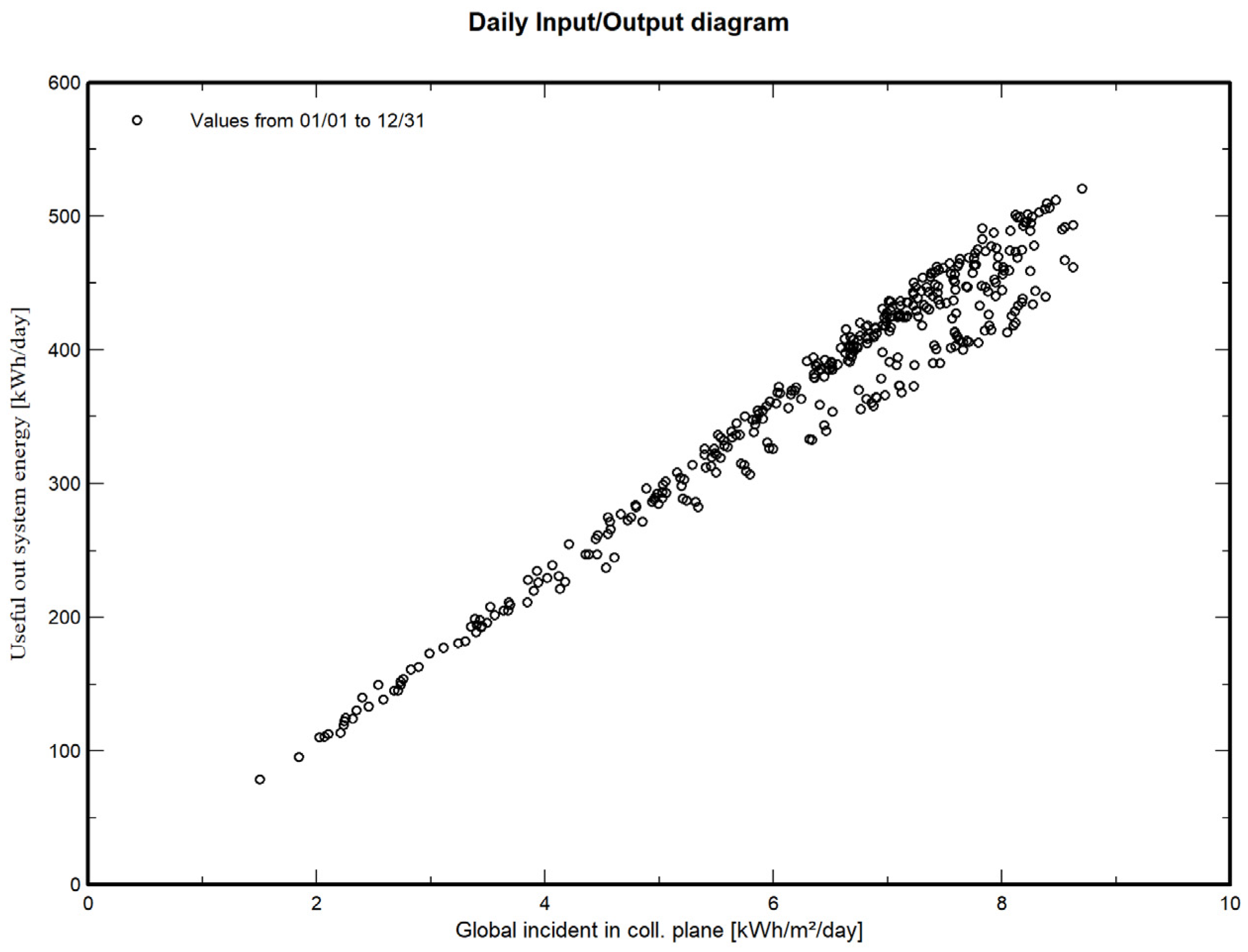

Figure 5. Additionally, the strong linear relationship between solar radiation and energy output confirms efficient energy conversion, as illustrated in

Figure 6.

3.2.1. Olive Trees

Beyond energy generation, the agri-PV system incorporates 300 olive trees (Olea europaea) planted beneath the elevated solar panels. This dual-land-use strategy creates a favorable microclimate for olive cultivation by providing shade, reducing evaporation, and lowering soil temperatures, which enhances agricultural productivity and water-use efficiency. The selection of olive trees was based on their regional adaptability, economic value, and the local population’s cultivation expertise. The solar panels are mounted on long poles, allowing sufficient space and light for the olive trees to thrive.

4. Conclusions

The Sultanate of Oman, like many arid regions, faces severe climate change impacts, particularly water scarcity, declining agricultural productivity, and rural depopulation. In areas such as Dar Al Sawda, reduced rainfall has led to deteriorating soil quality and declining livestock and crop yields, forcing many residents to migrate to urban centers. Addressing these challenges requires integrated, sustainable solutions that align with Oman Vision 2040 and national climate adaptation strategies. This study proposes a comprehensive Green Village model, integrating renewable energy, wastewater treatment, and agroforestry to enhance water efficiency, food security, and energy sustainability. The system treats 26 m3 of wastewater per day using two ReedBox units, repurposing the treated water for irrigation of 300 olive trees cultivated under agri-photovoltaic structures. The solar energy system generates 147,708 kWh annually, ensuring a reliable power supply for both wastewater treatment and local households. This model demonstrates how renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and efficient water management can be integrated to support rural communities in adapting to climate change. Beyond environmental benefits, this initiative is expected to revitalize the local economy, creating employment opportunities and new income streams through olive farming, trade, and ecotourism. By fostering energy independence, agricultural resilience, and water security, this project provides a scalable framework for sustainable development in arid regions. The findings of this study reinforce the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in tackling climate-related challenges. Future research should focus on long-term system performance, economic viability, and scalability, ensuring that similar models can be effectively adapted to other water-scarce regions worldwide.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Sultan Al Maskari and Prof. Bachar; methodology, Sultan Al Maskari; software, Sultan Al Maskari; validation, Sultan Al Maskari, Prof. Bachar, and Steven Karma; formal analysis, Sultan Al Maskari; investigation, Sultan Al Maskari; resources, Sultan Al Maskari; data curation, Sultan Al Maskari; writing—original draft preparation, Sultan Al Maskari; writing—review and editing, Sultan Al Maskari and Steven Karma; visualization, Sultan Al Maskari; supervision, Prof. Bachar; project administration, Prof. Bachar. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study were generated using the PVSyst simulator and are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg for providing the academic and technical support necessary for this research. Special thanks to the German University of Technology in Oman (GUtech) for facilitating field research and translation support during interviews with local communities. The authors also acknowledge Bauer Nimr for their insights into wastewater treatment solutions and the application of ReedBox technology. Lastly, appreciation is extended to the residents of Dar Al Sawda, Karb, and Al-Khitaym, whose cooperation and participation in interviews provided invaluable information for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Definition |

| BTU |

Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg |

| GUtech |

German University of Technology in Oman |

| PV |

Photovoltaic |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| HLR |

Hydraulic Loading Rate |

| BOD |

Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| PR |

Performance Ratio |

| APV |

Agri-Photovoltaics |

| PVsyst |

Photovoltaic System Simulation Software |

| NDC |

Nationally Determined Contribution |

| ReedBox |

Natural-based wastewater treatment system by Bauer Nimr |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Green Village Interview Guide: Key Topics and Questions.

Table A1.

Green Village Interview Guide: Key Topics and Questions.

| Green Village Interview Guide |

Questions |

| 1. General Questions |

- Age, educational background, employment status, living situation |

| 2. Climate Change |

- Were changes recognized?

- What changes/symptoms? |

| 3. Waste Management |

- Is waste separated?

- How is waste disposed of, and where does it go? |

| 4. Electricity Supply |

- What is electricity currently sourced from?

- Knowledge about renewable energy (e.g., solar panels)?

- Opinion on renewable options? |

| 5. Land Use |

- How are private lands used? |

| 6. Water Management |

- Where is the water sourced from? How does it reach households?

- How much water is available? Is it sufficient?

- If there is a shortage, what is the reason (physical availability, price, quality, etc.)? |

| 7. Tourism |

- Experiences and relationship with tourists

- Opinion on tourists – are more or less desired? |

| 8. Ending Questions |

- Any other important topics/aspects?

- Wishes and expectations for the future- Opinion on Green Village Project (active or passive participation wanted, special conditions, etc.) |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Targets and Descriptions.

Table A2.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Targets and Descriptions.

| SDG Target |

Description |

| 1.1 |

By 2030, eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere, currently measured as people living on less than $1.25 a day. |

| 1.4 |

By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology, and financial services, including microfinance. |

| 6.3 |

By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing the release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater, and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally. |

| 6.4 |

By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity. |

| 6.a |

By 2030, expand international cooperation and capacity-building support to developing countries in water- and sanitation-related activities and programmes, including water harvesting, desalination, water efficiency, wastewater treatment, recycling, and reuse technologies. |

| 6.b |

Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management. |

| 7.2 |

By 2030, increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix. |

| 11.3 |

By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated, and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries. |

| 11.b |

By 2020, substantially increase the number of cities and human settlements adopting and implementing integrated policies and plans towards inclusion, resource efficiency, mitigation and adaptation to climate change, resilience to disasters, and develop and implement, in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, holistic disaster risk management at all levels. |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Energy Balance and Performance Indicators Extracted from PVsyst.

Table A3.

Energy Balance and Performance Indicators Extracted from PVsyst.

| Balances and main results |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

GlobHor |

DiffHor |

T_Amb |

GlobInc |

GlobEff |

EArray |

E_Grid |

PR |

| |

kWh/m² |

kWh/m² |

°C |

kWh/m² |

kWh/m² |

kWh |

kWh |

ratio |

| January |

139.6 |

41.3 |

8.52 |

194.5 |

152.2 |

11008 |

10550 |

0.723 |

| February |

148.5 |

40.18 |

10.83 |

187 |

159.7 |

11309 |

10849 |

0.773 |

| March |

179.2 |

61.75 |

15.17 |

197.2 |

181.3 |

12542 |

12025 |

0.813 |

| April |

201.6 |

63.51 |

19.29 |

196.1 |

183.5 |

12495 |

11977 |

0.814 |

| May |

218.6 |

71.62 |

23.54 |

194.2 |

180.4 |

12140 |

11622 |

0.798 |

| June |

212.4 |

78.08 |

25.45 |

181.8 |

168.2 |

11272 |

10776 |

0.79 |

| July |

200.7 |

90.51 |

25.69 |

176.9 |

162.3 |

10866 |

10371 |

0.782 |

| August |

192.6 |

87.77 |

24.29 |

182.7 |

168.9 |

11322 |

10823 |

0.79 |

| September |

183.3 |

57.21 |

21.38 |

193.3 |

180.5 |

12116 |

11609 |

0.801 |

| October |

174.8 |

45.42 |

17.81 |

207.9 |

184.9 |

12586 |

12069 |

0.774 |

| November |

149.3 |

37.81 |

12.78 |

203.1 |

163 |

11492 |

11029 |

0.724 |

| December |

131.4 |

37.16 |

9.89 |

189.2 |

143.9 |

10369 |

9931 |

0.7 |

| Year |

2131.9 |

712.32 |

17.92 |

2303.9 |

2028.8 |

139515 |

133630 |

0.773 |

References

-

Al-Harthi, R.; Al-Maqbali, S.; Al-Balushi, Z.; Al-Maani, A. A Study on Usage of Treated Wastewater as Resource Management for the Sustainable Development of Al Amerat. ResearchGate 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381675244_A_Study_on_Usage_of_Treated_Wastewater_as_Resource_Management_for_the_Sustainable_Development_of_Al_Amerat (accessed on 5 August 2024).

-

Al-Kalbani, M.; Price, M.; O’Higgins, T.; Ahmed, M.; Abahussain, A. Integrated environmental assessment to explore water resources management in Al Jabal Al Akhdar, Sultanate of Oman. Reg. Environ. Change 2016, 16, 1345–1361. [CrossRef]

-

Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013.

-

Griggs, J.; Grant, N. Reed beds: design, construction and maintenance. Good Building Guide 42 Part 2, BRE, 2000. Available online: https://cis.ihs.com/cis/document/250722 (accessed on 5 August 2024).

-

International Energy Agency (IEA). Climate Resilience for Energy Transition in Oman; IEA, 2021. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/climate-resilience-for-energy-transition-in-oman (accessed on 5 August 2024).

-

Johnson, L. Sustainable Management Practices in Arid Regions. J. Environ. Stud. 2020.

-

Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009.

-

Meteoblue. Mean yearly temperature, trend, and anomaly, 1979–2023 in Al Jabal Al Shams area. Available online: https://www.meteoblue.com/en/weather/historyclimate/climatemodelled/jabal-shams_oman_286476 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

-

Oman Observer. Stargazers’ haven: Jabal Shams is now a protected reserve. Oman Observer 2017. Available online: https://www.omanobserver.om/article/32028/Main/stargazers-haven-jabal-shams-is-now-a-protected-reserve (accessed on 5 August 2024).

-

OnePetro. Sustainable Treatment of Wastewater Generated by Oil & Gas Operations. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, Abu Dhabi, UAE, November 2022. Available online: https://onepetro.org/SPEADIP/proceedings-abstract/22ADIP/4-22ADIP/513404 (accessed on 5 August 2024).

-

Pala, K. Participants’ Motivations for International Sporting Events in Oman: A Comparative Study between Muscat Marathon, Iron Man, and Spartan Race. ResearchGate 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373271453_Participants_’Motivations_for_International_Sporting_Events_in_Oman_A_Comparative_Study_between_Muscat_Marathon_Iron_Man_and_Spartan_Race (accessed on 5 August 2024).

-

Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015.

-

Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, I.S. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012.

-

Searle, M.P. Jebel al-Akhdar. In Geology of the Oman Mountains, Eastern Arabia; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 235–277. [CrossRef]

-

Smith, A. Environmental Sustainability and Management. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018.

-

Stefanakis, A.I. Reedbox®: An innovative compact mobile Constructed Wetland unit for wastewater treatment. ResearchGate 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333310121_ReedboxR_an_innovative_compact_mobile_Constructed_Wetland_unit_for_wastewater_treatment (accessed on 5 August 2024).

-

Times News Service. Oman to set up new ’star-light’ reserve. Times of Oman 2019, 12 May. Available online: https://timesofoman.com/article/76313-oman-to-set-up-new-star-light-reserve (accessed on 5 August 2024).

-

Times of Oman. Travel Oman: Jabal Shams – Oman’s Grand Canyon. Times of Oman 2019. Available online: https://timesofoman.com/article/2136085/oman/tourism/travel-oman-jabal-shams-omans-grand-canyon (accessed on 5 August 2024).

-

Trask, B.S. The ambiguity of boundaries in the fieldwork experience: Establishing rapport and negotiating insider/outsider status. In Performing Qualitative Cross-Cultural Research; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 86–108.

-

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN). Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 5 August 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).