Introduction

A goal of geroscience is to reduce the risk of multiple age-related diseases simultaneously and improve healthspan by developing preventive approaches that target fundamental process of aging [

1,

2,

3]. However, a better understanding is needed of which age-related measures to select for aging intervention outcomes and predicting or monitoring clinical responses. Biomarkers of epigenetic aging have been proposed as potential surrogate measures of healthspan that may change rapidly over a short-term intervention and predict long-term clinical effects [

4]. A growing number of epigenetic aging biomarkers have been developed based on DNA methylation levels in blood that are predictive of chronological age differential morbidity and mortality risk, and phenotypic aging [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. While no standard measure of epigenetic “aging” has yet emerged, this tool offers promise as an objective measure of health status that may be measured across the life course with a simple blood test.

Nutrition impacts healthspan and may affect the rate of biological aging in humans [

11,

12]. A number of

a priori-defined dietary indices that capture the essential components of a healthy diet [

13] have been shown to be inversely associated with the risk of frailty, morbidity, and mortality, including the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), a measure of adherence to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, [

14] as well as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) [

15,

16] and alternate Mediterranean (aMED) [

17] diet indices [

13,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. However, controversy remains regarding the optimal dietary guidelines to promote healthy aging [

25]. For instance, dietary patterns including the original DASH diet recommend a low-fat diet [

26]. However, a low-fat diet had no significant effects on incidence of cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, HR, 0.98; 95% confidence interval, CI, 0.92-1.05) in the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial of 48,835 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years [

27]. Alternatively, consumption of foods higher in mono- and polyunsaturated fats including extra virgin olive oil and fish is hypothesized to underlie benefits associated with Mediterranean-style dietary interventions [

28,

29,

30,

31]. A better understanding of the impact of dietary factors on biological mechanisms of aging could help lay the foundation for development of precision nutrition approaches customized to increase healthspan.

Changes in epigenetic aging biomarkers may be useful indictors of the effects of diet on aging biology. Emerging evidence from dietary intervention studies support the potential to slow epigenetic aging through dietary modifications [

32,

33,

34]. Cross-sectional associations also suggest that higher diet quality is associated with slower epigenetic aging [

35,

36,

37]. However, the longitudinal effects of diet on epigenetic aging are not clear.

We hypothesize that a simple Mediterranean diet-inspired intervention involving daily tree nut and extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) supplementation will slow epigenetic aging and increase healthspan, particularly in individuals with advanced biological aging. Supporting our hypothesis, a five-year study in Spain (PREDIMED) evaluated the effects of the Mediterranean diet on primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in subjects at high risk of CVD [

30]. PREDIMED was a multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of 7,447 participants who were randomized to one of three diets: Mediterranean diet supplemented with EVOO, Mediterranean diet supplemented with mixed nuts, or a low-fat control diet. PREDIMED found a reduction in the cardiovascular event rates in both intervention groups compared to the low-fat control group. Additionally, post-hoc analysis of individuals meeting the criteria for metabolic syndrome (MetS) at baseline revealed EVOO and nut consumption was more likely to result in reversion of MetS compared to the low-fat control diet (HR = 1.35 95% CI: 1.15 – 1.58, p<0.001) [

38].

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of metabolic irregularities that significantly increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes (T2D) and CVD [

39]. The cluster of metabolic irregularities that comprise MetS includes several known CVD risk factors that typically increase with age, including hypertension, elevated fasting glucose levels, increased triglyceride levels, reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, and central adiposity. The presence of three of the five metabolic irregularities constitutes a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome [

40]. The prevalence of MetS is rising worldwide, and as of 2018, over half of adults 60 years and older met the criteria for MetS [

41,

42]. MetS and MetS components including abdominal obesity, reduced HDL cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, and elevated blood glucose have been associated with advanced biological aging [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47], including DNA methylation-based epigenetic aging measures [

48,

49]. Significant reductions in central obesity (p<0.001) were observed in PREDIMED participants with MetS in both the EVOO and mixed nut intervention groups compared to the low-fat control diet [

38]. Further, PREDIMED participants with MetS in the EVOO supplementation group were more likely to no longer meet the criterion of high fasting glucose levels compared to the low-fat control diet (p = 0.02). However, the effects of tree nut and EVOO supplementation on epigenetic aging is unknown.

Despite the potential benefit of EVOO supplementation and nut consumption for treatment of MetS, lower levels of adherence to the PREDIMED intervention was found in participants with a larger waist circumference, lower physical activity levels at baseline, and a higher number of CVD risk factors [

50]. We hypothesize that conveying potentially modifiable estimates of biological aging to participants at the onset of a dietary intervention will improve participant adherence to dietary interventions. In particular, epigenetic aging biomarkers have potential to be modifiable estimates of biological aging [

5,

7,

8,

9,

10] that could serve as a motivating factor for dietary changes to improve participant adherence to the intervention.

To provide support for the development of dietary approaches targeting fundamental biological processes of aging to increase healthspan, and translation of epigenetic aging biomarkers as tools to motivate behavior change, here we report results from a four-week pilot study of tree nut and EVOO supplementation in adults with MetS. The goals of this pilot study were to 1) determine the prevalence of advanced epigenetic aging among adults with MetS, 2) assess adherence to daily tree nut and EVOO consumption over the four-week intervention, 3) explore how participants’ experiences would impact the feasibility of a larger clinical intervention, and 4) qualitatively assess participants’ interest in knowing their epigenetic aging measures and potential for knowledge of epigenetic aging measures to motivate behavior change and improve intervention adherence. An exploratory aim was to examine early changes in epigenetic aging biomarkers associated with the four-week tree nut and EVOO intervention.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a prospective, longitudinal, two-arm feasibility pilot study. Men and women residing in and around Winston-Salem/Forsyth County, North Carolina were recruited to participate in this study. Inclusion criteria required participants to be at least 35 years of age and to meet the criteria for MetS, defined as at least three of the following: waist circumference >102 cm in men and >88cm in women, Triglyceride levels >150 mg/dL and/or drug treatment for elevated triglycerides, HDL cholesterol levels <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women and/or drug treatment for reduced HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure >130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure >85 mmHg and/or antihypertensive drug treatment, and fasting glucose >100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c > 5.6% and/or oral hypoglycemic medications. Participants were also required to be willing to comply with study visits, as outlined in the protocol, to be able to read and speak English, not have allergies or hypersensitivities to olive oil or nuts, and to have the ability to understand and the willingness to sign a written informed consent document. Exclusion Criteria included plans to move from the study area in the next 12 weeks, body mass index (BMI) > 40 kg/m2, dementia that is medically documented or suspected, or clinical evidence of cognitive impairment sufficient to impair protocol adherence, any dietary practice, behavior or attitude that would substantially limit ability to adhere to protocol, homebound for medical reasons, living in the same household with another participant, and insulin-dependent diabetes. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institution Review Board (IRB) of Wake Forest University Health Sciences (IRB00065273) and all participants signed an informed consent document prior to study commencement.

Participants who met the eligibility criteria were invited to participate in a four-week tree nut and extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) intervention. Participants were randomized to learn about epigenetic aging or not to learn about epigenetic aging in a 1:1 allocation at the intervention visit. Those in the intervention arm learning about epigenetic aging received educational materials (see Supplemental Information) and a brief description of epigenetic aging. All participants provided blood samples to determine epigenetic aging estimates.

Intervention Foods: Tree Nuts and Extra Virgin Olive Oil

All participants received a four-week supply of EVOO and tree nuts, including individual daily servings (1 oz. each) of unsalted English walnuts, almonds or pistachios (approximately 10-day supply of each type). Participants were asked to consume one ounce of tree nuts per day and two tablespoons of EVOO per day by incorporating these foods into their diet. Participants were provided recipes and other information to help them to replace other foods with the nuts and oil. Dietary adherence diaries were given to measure incorporation of the study foods.

Study Measures

Participants had in person study-related measurements collected at baseline and at the end of the four-week intervention. For the baseline visit, participants were asked to fast and complete study questionnaires to measure demographics, health history Mediterranean diet adherence [

51,

52] to assess their baseline diet including consumption of olive oil and nuts (see Supplemental Information). Blood pressure was measured after resting five minutes and sitting upright. Body weight was measured in kilograms using a beam scale with movable weights with participant wearing indoor clothing with no shoes. Height and waist circumference were measured in centimeters. Participants had a fasting blood collection, and triglyceride levels, HDL cholesterol levels, and fasting glucose measurements were performed in a local LabCorp facility. Blood was collected in Vacutainer tubes (with EDTA) for DNA methylation analyses, performed at Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

A telephone visit was conducted at the end of week 1 after the intervention visit to assess safety/potential side effects, to collect adherence diaries, and for additional diet counseling. A follow-up phone call for compliance assessment and to answer participant questions was also conducted at the end of week 2.

At the final visit at the end of week 4, participants were asked to be fasting, complete a Mediterranean diet screener, and adherence diaries were collected. Blood pressure, body weight, height, and waist circumference were assessed as in the Baseline visit, and fasting blood was collected. All participants were administered an Intervention Experience Assessment to explore how participants’ experiences would impact the feasibility of a larger clinical intervention in terms of challenges and motivators. Participants in the intervention arm educated about epigenetic aging were also asked to complete a self-administered exit questionnaire to qualitatively explore participants’ perception of epigenetic aging as a potential motivator for behavior change.

Epigenetic Aging

DNA was extracted from fasting blood samples, and was bisulfite-converted using the EZ DNA Methylation Gold kit (Zymo, Irvine, CA). The Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip, which targets over 850,000 CpG sites, and the Illumina iScan Reader were used to determine the proportion of DNA methylation at each site. Quality control measures included the cumulative fluorescent signal being significantly greater than the negative controls included for each sample, and a threshold of detection p-value of ≤0.05 in at least 90% of the samples. The BioConductor R package ChAMP [

53] was used for quality control, including a BMIQ adjusted for the different assays performed (i.e., Infinium I and Infinium II). After filtering for poorly-performing assays, 720,027 methylation values passed quality control. Adjustment for slide (each BeadChip) was performed using Combat [

54].

Epigenetic aging measures were calculated from DNA methylation profiles (beta-value) using the DunedinPACE [

10] and GrimAge [

9] biomarkers. For DunedinPACE, 173 DNA methylation profiles were utilized to calculate an epigenetic biomarker of ‘Pace of Aging’ [

10], with an additional 19,827 DNA methylation profiles used for the normalization process [

10]. DunedinPACE was designed to be interpreted with a reference to an average rate of one year of biological aging per year of chronological aging, with values greater than 1 representing a faster rate of aging, or advanced epigenetic aging. For GrimAge, 1,030 DNA methylation profiles were utilized to calculate the GrimAge biomarker [

9]. GrimAge was designed as an epigenetic predictor of time-to-death [

9]. GrimAge values were regressed on chronological age to produce estimates of epigenetic aging relative to chronological age (AgeAccelGrim), with values greater than zero representing advanced epigenetic aging.

Outcomes

To characterize the relationship between MetS and epigenetic aging, we examined the prevalence of advanced epigenetic aging among participants. To assess adherence to daily tree nut and EVOO consumption over the four-week intervention, we calculated the proportion of days for which tree nuts were taken, the proportion of days for which EVOO was taken, and the proportion of days for which tree nuts and EVOO were taken, based on the daily adherence diaries. To assess participant experiences and gauge feasibility of a long-term tree nut and EVOO intervention, we asked participants: “How difficult did you find it to eat the tree nuts and olive oil every day?” reported on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being “not difficult at all”, 5 being “moderately difficult”, and 10 being “very difficult”, “Will you continue to eat tree nuts and olive oil daily after completing the research study?” reported as “very unlikely”, “unlikely”,” neutral”, “somewhat likely”, “very likely”, and “Do you think that you would be able to participate in a study like this one that lasted 3-4 years? In other words, would you be able to continue eating the tree nuts and olive oil for 3-4 years?” reported as” yes” or “no”. Participants in the epigenetic aging intervention group were additionally asked, “Using the scale below, indicate how much you want to know your epigenetic age: “Not at all”, “not much”, “neutral”, “somewhat”, “very much”, “Before beginning this study, if you were told your epigenetic age appeared more advanced than your chronological age, do you think you would be more or less motivated to eat the nuts and olive oil every day?” reported as: “not motivated at all”, “less motivated”, “neutral”, “more motivated”, and “very motivated”; and “If eating tree nuts and olive oil slowed biological aging, how likely would you be to continue to eat tree nuts and olive oil daily?” reported as: “very unlikely”, “unlikely neutral”, “somewhat likely”, “very likely”. As an exploratory outcome we compared epigenetic aging measures, DunedinPACE and GrimAge, and MetS component measures, at the baseline visit and the final four-week visit.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies, etc.) were used to summarize participant characteristics and outcomes. Participants were tested for advanced epigenetic aging using a one-sided nonparametric Wilcoxon test against one for DunedinPACE and against zero for AgeAccelGrim. Change in epigenetic aging measures, DunedinPACE and GrimAge, and MetS component measures [waist circumference, triglyceride levels, HDL cholesterol levels, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, fasting glucose levels, and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels] were compared from the baseline visit and the final four-week visit using a paired sample t-test.

Results

Participants were enrolled from July 2021 to February 2022. Of the 54 individuals that attended the in-person screening, 53 individuals provided informed consent and one individual refused to participate. 34 of the 53 participants (63%) were found to be eligible for the intervention. Among excluded participants, 17 did not meet the criteria for MetS, and two had a BMI > 40 kg/m

2. Participants were between 48 and 81 years (mean age: 68 ± 9 years), and were randomized to either the epigenetic aging knowledge arm or the active comparator group (

Table 1). One participant withdrew before study completion, with 33 participants completing the four-week tree nut and EVOO intervention. The majority of participants were women (59%), White (56%), and reported a non-Hispanic ethnicity (100%). Participants had a low to moderate level of adherence to a Mediterranean-like diet on average (mean MedDiet Screener score = 6.7 ± 1.9). Olive oil was reported as main culinary fat by 45% of participants, with average daily consumption of 0.9 ± 3.5 tablespoons of olive oil. Average nut consumption, including peanut consumption, per week was 6.2 ± 4.5 servings at baseline.

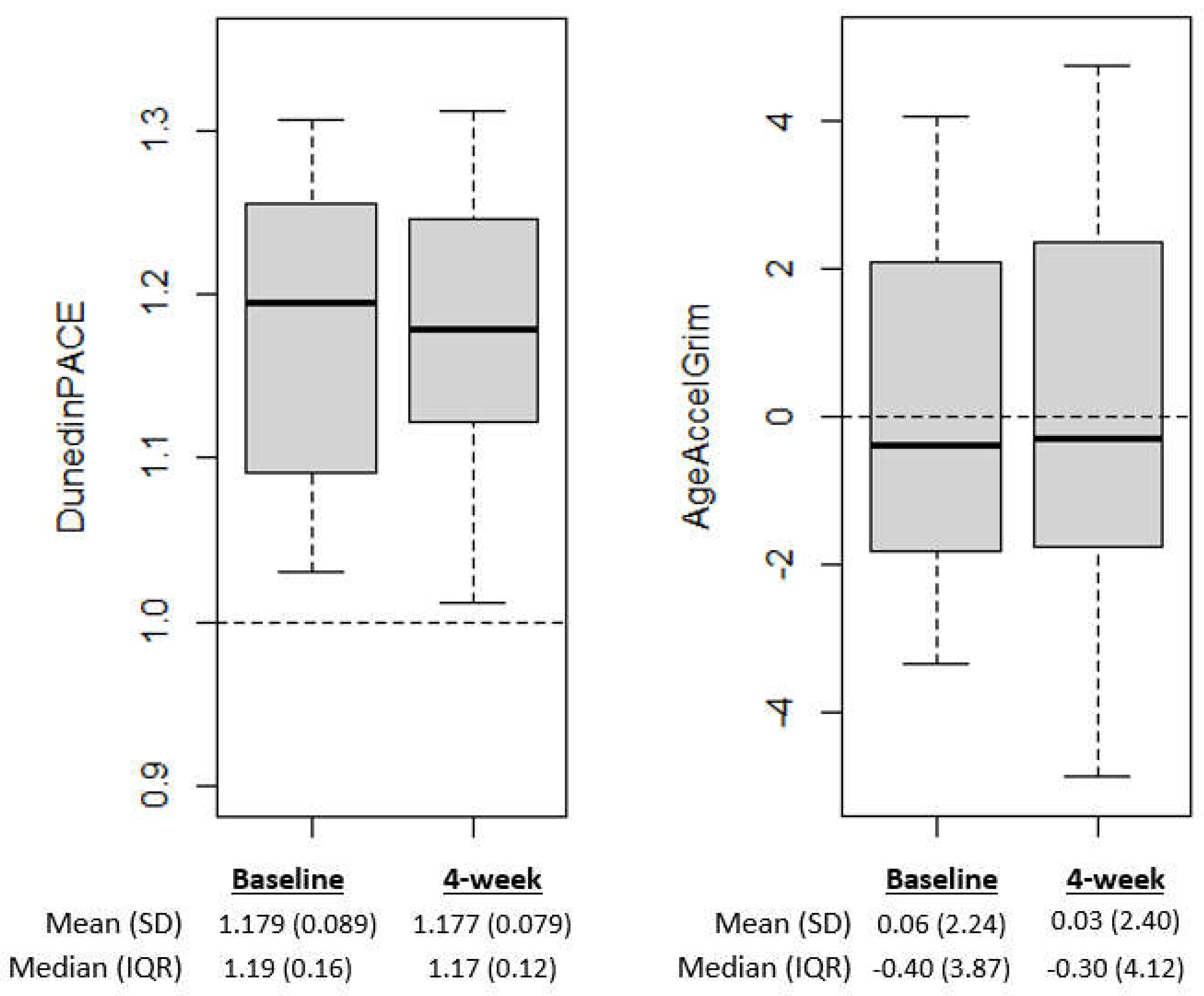

At baseline, advanced epigenetic aging was observed using the DunedinPACE biomarker of pace of aging, with 100% of participants having DunedinPACE faster than one year of biological aging per year of chronological aging (Wilcoxon test > 1, p=3.73E-9; DunedinPACE mean ± SD = mean 1.18 ± 0.09, see

Figure 1A). There was not significant advanced epigenetic aging relative to chronological age at baseline based on the GrimAge biomarker, with 11 of the 29 participants with DNA methylation at baseline having AgeAccelGrim>0 (Wilcoxon test > 0, p=0.48).

Self-reported adherence to daily tree nut and EVOO consumption over the four-week intervention was high. On average participants reported it was “not difficult at all” to consume one oz. of tree nuts every day (average adherence 98.6%), and that it was between “not difficult at all” and “moderately difficult” to consume two tablespoons of olive oil every day (average adherence 96.4%). The average adherence to daily nut supplementation was 98.6% overall, with 99.7% for epigenetic aging arm and 97.7% for active comparator arm, with no significant (p<0.05) statistical difference by intervention arm (p=0.10). The average adherence to daily EVOO supplementation was 96.4%, with no significant statistical difference by intervention arm (95.6% for epigenetic aging arm, 97.2% for the active comparator arm, p=0.51).

The majority of participants in this pilot study (84%) reported they would be able to continue eating tree nuts and EVOO in a study like this lasting three to four years (76% of the epigenetic aging arm and 93% of the active comparator arm (t =-1.3, p =0.19). Results from the participant experiences survey conducted after the 4-week intervention are included in the Supplemental Information.

The majority (77%) of participants in the epigenetic aging arm reported they “very much” wanted to know their epigenetic age. Also 82% reported that if they were told their epigenetic age appeared more advanced than chronological age, they would be “more motivated” or “very motivated” to consume the tree nuts and EVOO every day. Results from the participant epigenetic aging survey are included in the Supplemental Information.

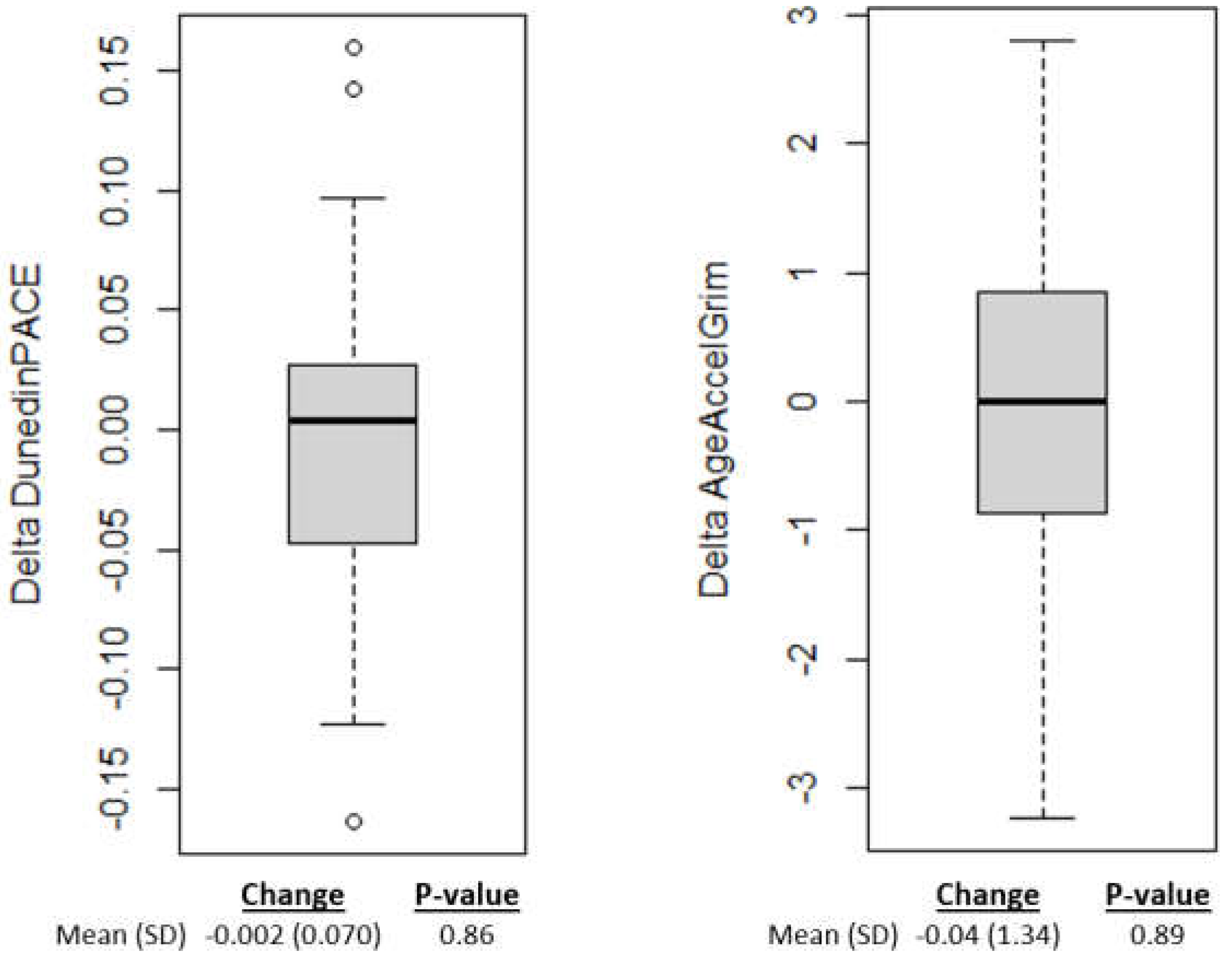

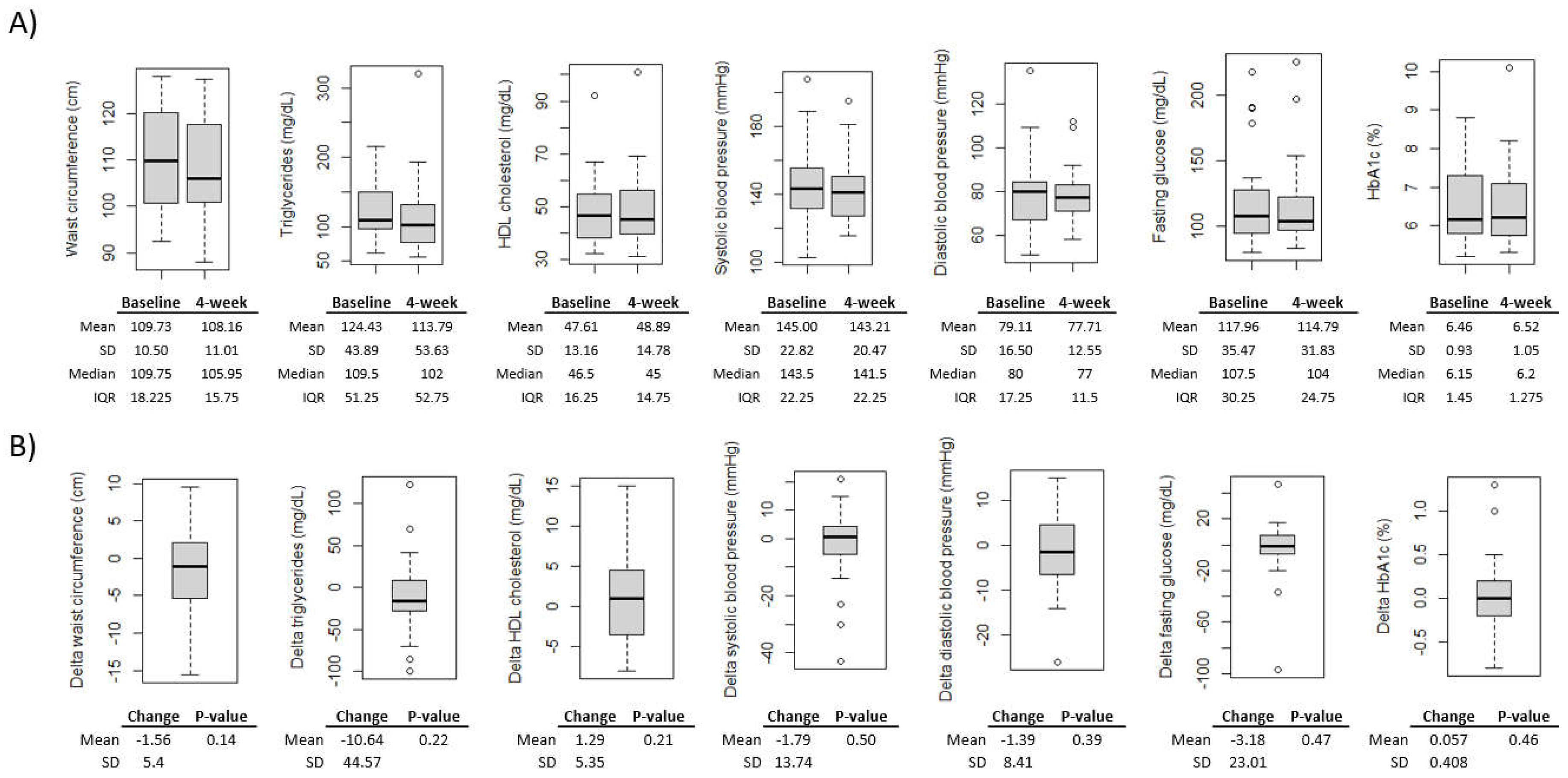

On average epigenetic aging scores decreased from baseline to after the 4-week intervention; however, the changes were not significant (p<0.05) for either epigenetic aging measure (

Figure 2). Additionally, all MetS component measures changed in the expected direction of improvement, with the exception of HbA1c; however, the changes were not significant (p<0.05) for any MetS component measures (

Figure 3).

Discussion

This feasibility study, incorporating a tree nut and EVOO intervention and epigenetic aging estimates for individuals with MetS, is an initial step to support future studies testing the potential for a simple dietary intervention to slow epigenetic aging. This pilot intervention study also provides preliminary support for the translation of epigenetic aging biomarkers from a research concept towards a tool to meaningfully promote healthy lifestyle changes to improve cardiometabolic health among individuals at high risk for cardiovascular disease. The preliminary data generated by this pilot study will be used to inform the design of a larger, long-term dietary intervention aiming to slow epigenetic aging and support epigenetic aging markers as surrogate measures of healthspan that can predict long-term clinical effects on cardiometabolic health.

A key preliminary finding from this pilot study is the potential for epigenetic aging biomarkers as to serve as motivating factors for behavior change among adults with MetS. It is not well known if biological age, estimated using epigenetic markers, is a motivating factor for behavior change. As participants of the PREDIMED intervention with many CVD risk factors were found to have lower levels of adherence to the intervention than participants with fewer CVD risk factors [

50], finding ways to motivate behavior change particularly among adults with many CVD risk factors is significant as it could improve adherence to dietary interventions aiming to reduce CVD risk. We qualitatively explored how participants perceived epigenetic age, and found the majority of participants reported “very much” wanting to know their epigenetic aging measures and felt that knowledge of epigenetic aging measures could serve as a motivating factor for behavior change. Epigenetic aging estimates also hold great promise to improve patient-centered care and screening for risk of disease and mortality. Although advanced epigenetic aging is strongly predictive for the risk of morbidity and mortality, our understanding of epigenetic age acceleration is in its infancy. Preliminary data generated by this pilot study supports the need for future larger studies to better understand the potential for using personalized epigenetic-based risk scores as a motivating factor for behavior change.

Findings from this pilot study, and other recent findings support the association between MetS and advanced epigenetic aging, particularly as measured by the DunedinPACE epigenetic biomarker [

48]. Fohr et al. reported the association between MetS and epigenetic aging to be independent of physical activity, smoking or alcohol consumption, and may be explained by genetics [

48]. While genetics may be a major confounder in the association between MetS and epigenetic aging, Fohr et al. did not examine diet as a lifestyle factor potentially influencing the relationship between MetS and epigenetic aging. Our previous cross-sectional analyses in a subset of participants of the Women’s Health Initiative using baseline data indicate that higher diet quality is more strongly associated with lower DunedinPACE, that other epigenetic aging measures (i.e., Hannum, [

5] Horvath, [

6] PhenoAge, [

8] GrimAge, [

9]). Together, these results demonstrate the differences between various epigenetic aging biomarkers and suggest DunedinPACE may be a leading choice of current epigenetic biomarkers for predicting or monitoring clinical responses to dietary aging interventions. DunedinPACE is distinct from the other epigenetic aging measures in the method of its design that allows for distinguishing aging from cohort effects and from disease processes. DunedinPACE was built to predict pace of aging, based on within-individual longitudinal changes in 19 indicators of organ-system integrity across two decades in a cohort of individuals born in 1972 – 1973. DunedinPACE appears to be a sensitive epigenetic aging marker to both cardiometabolic health and diet; however, longitudinal studies are needed to test DunedinPACE as a molecular mediator of the effect of dietary intake on cardiometabolic health.

Integration of dietary interventions and epigenetic data could be a powerful technique for understanding the impact of diet on the biological mechanisms of aging. Although this four-week study did not result in significant changes in epigenetic aging biomarkers, the pilot study was not powered to answer this question. Rather, this pilot study was intended to gauge participant interest in wanting to know their epigenetic aging scores, and to provide estimates of epigenetic aging biomarker variability to inform power calculations and design of a future intervention study. Emerging evidence from intervention studies supports the ability for diet to slow epigenetic aging longer than 18 months. For instance, a two-year diet intervention in 57 women counselled to adopt a plant-based diet with a low glycemic load, low in saturated and

trans-fats and alcohol, and rich in antioxidants was associated with slowing of GrimAge compared to the 58 women in the control group [estimate: -0.66 (-1.15, -0.17, p=0.01)] [

33]. Additionally, findings from the Comprehensive Assessment of Long-term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy (CALERIE) trial, a two-year randomized controlled trial of 25% caloric restriction, reported caloric restriction (n=117) was associated with a slower epigenetic aging measure (DunedinPACE) [

10], compared to the control condition (n=68) [

11]. Cross-sectional associations suggest that higher diet quality measured by the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), a measure of how well a person adheres to the US Dietary Guidelines[

14], is associated with slower epigenetic aging (e.g., DunedinPACE) [

35,

36,

37,

49].

This feasibility study, incorporating epigenetic aging biomarkers in a tree nut and EVOO intervention in individuals with MetS, is an initial step in building our understanding of the relationship between diet, epigenetic aging, and MetS, and how epigenetic aging biomarkers may be perceived by individuals at high risk for CVD. Results from this study will be used to design a future longer, larger trial powered to test for changes in epigenetic aging. There are a number of limitations to interpretation of the preliminary findings from this pilot study, including the short time window of the intervention and small sample size. Additionally, the absence of a placebo control group makes it difficult to isolate the specific effects of the tree nut and EVOO intervention from potential placebo effects. Overall, findings from this pilot study demonstrate an advanced pace of aging among individuals with MetS, and interest among individuals with MetS in knowing their epigenetic aging measures. Further, the pilot study findings provide support for the potential for biological aging measures to motivate behavior change. These findings provide critical information to inform the development of future aging intervention studies aiming to test the ability of a simple dietary intervention involving supplementation of tree nuts and EVOO to slow biological aging.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Epigenetic Aging Educational Information, Modified 14-Item Questionnaire of Mediterranean diet adherence, Participant Experiences Interview, and Epigenetic Aging Exit Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.R and M.Z.V.; methodology, L.M.R, T.D.H, C.D.L., and M.Z.V.; analysis, T.D.H and L.M.R; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.R.; writing—review and editing, L.M.R, T.D.H, C.D.L., and M.Z.V.; funding acquisition, L.M.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wake Forest University Health Sciences (protocol code IRB00065273 and date of approval 6/11/2020). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants for their contributions to the study. We also thank the Clinical Research Unit Registered Dietitians for their contributions implementing the intervention. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR001420, and by the Cardiovascular Sciences Center Pilot Funding, Wake Forest University School of Medicine. We would like to acknowledge the start up, regulatory maintenance, participant visit and participant management, screen/recruit/consenting, and data management services of the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute (WF CTSI), which is supported by the NCATS, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR001420. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Statements and Declarations

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Rolland, Y.; Sierra, F.; Ferrucci, L.; Barzilai, N.; De Cabo, R.; Mannick, J.; Oliva, A.; Evans, W.; Angioni, D.; De Souto Barreto, P.; et al. Challenges in developing Geroscience trials. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVito, L.M.; Barzilai, N.; Cuervo, A.M.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Milman, S.; Levine, M.; Promislow, D.; Ferrucci, L.; Kuchel, G.A.; Mannick, J.; et al. Extending human healthspan and longevity: a symposium report. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2022, 1507, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, B.K.; Berger, S.L.; Brunet, A.; Campisi, J.; Cuervo, A.M.; Epel, E.S.; Franceschi, C.; Lithgow, G.J.; Morimoto, R.I.; Pessin, J.E.; et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell 2014, 159, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, S.R.; Kritchevsky, S.B. Endpoints for geroscience clinical trials: health outcomes, biomarkers, and biologic age. GeroScience 2022, 44, 2925–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannum, G.; Guinney, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Hughes, G.; Sadda, S.; Klotzle, B.; Bibikova, M.; Fan, J.B.; Gao, Y.; et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol 2013, 14, R115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wilson, R.; Heiss, J.; Breitling, L.P.; Saum, K.-U.; Schöttker, B.; Holleczek, B.; Waldenberger, M.; Peters, A.; Brenner, H. DNA methylation signatures in peripheral blood strongly predict all-cause mortality. Nature communications 2017, 8, 14617–14617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Chen, B.H.; Assimes, T.L.; Bandinelli, S.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Stewart, J.D.; Li, Y.; et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 2018, 10, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Wilson, J.G.; Reiner, A.P.; Aviv, A.; Raj, K.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Li, Y.; Stewart, J.D.; et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, D.W.; Caspi, A.; Corcoran, D.L.; Sugden, K.; Poulton, R.; Arseneault, L.; Baccarelli, A.; Chamarti, K.; Gao, X.; Hannon, E.; et al. DunedinPACE, a DNA methylation biomarker of the pace of aging. Elife 2022, 11, e73420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waziry, R.; Ryan, C.P.; Corcoran, D.L.; Huffman, K.M.; Kobor, M.S.; Kothari, M.; Graf, G.H.; Kraus, V.B.; Kraus, W.E.; Lin, D.T.S.; et al. Effect of long-term caloric restriction on DNA methylation measures of biological aging in healthy adults from the CALERIE trial. Nature Aging 2023, 3, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, L.; Houston, D.; Skiba, M.; Whitsel, E.; Stewart, J.; Li, Y.; Zannas, A.; Assimes, T.; Horvath, S.; Bhatti, P.; et al. PTFS07-06-23 Dietary Patterns and Epigenetic Aging in the Women’s Health Initiative. Current Developments in Nutrition 2023, 7, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liese, A.D.; Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Subar, A.F.; George, S.M.; Harmon, B.E.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Boushey, C.J.; Schap, T.E.; Reedy, J. The Dietary Patterns Methods Project: synthesis of findings across cohorts and relevance to dietary guidance. J Nutr 2015, 145, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Pannucci, T.E.; Subar, A.F.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Lerman, J.L.; Tooze, J.A.; Wilson, M.M.; Reedy, J. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2015. J Acad Nutr Diet 2018, 118, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.T.; Chiuve, S.E.; McCullough, M.L.; Rexrode, K.M.; Logroscino, G.; Hu, F.B. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med 2008, 168, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Van Horn, L.; Tinker, L.F.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Carbone, L.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Thomas, F.; Prentice, R.L. Measurement error corrected sodium and potassium intake estimation using 24-hour urinary excretion. Hypertension 2014, 63, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.T.; Rexrode, K.M.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Mediterranean diet and incidence of and mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Circulation 2009, 119, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liese, A.D.; Wambogo, E.; Lerman, J.L.; Boushey, C.J.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Wang, S.; Harmon, B.E.; Tinker, L.F. Variations in Dietary Patterns Defined by the Healthy Eating Index 2015 and Associations with Mortality: Findings from the Dietary Patterns Methods Project. J Nutr 2022, 152, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, C.; Li, X.; Fan, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, L. Healthy Eating Index-2015 and Predicted 10-Year Cardiovascular Disease Risk, as Well as Heart Age. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 888966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Y.R.; Robbins, J.M.; Gaziano, J.M.; Djoussé, L. Mediterranean, DASH, and Alternate Healthy Eating Index Dietary Patterns and Risk of Death in the Physicians’ Health Study. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.A.; Steffen, L.M.; Coresh, J.; Appel, L.J.; Rebholz, C.M. Adherence to the Healthy Eating Index-2015 and Other Dietary Patterns May Reduce Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, Cardiovascular Mortality, and All-Cause Mortality. J Nutr 2020, 150, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wu, H.; He, G.; Li, S.; Chen, B. Association between Dietary Patterns and Frailty Prevalence in Shanghai Suburban Elders: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengeveld, L.M.; Wijnhoven, H.A.H.; Olthof, M.R.; Brouwer, I.A.; Simonsick, E.M.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Houston, D.K.; Newman, A.B.; Visser, M. Prospective Associations of Diet Quality With Incident Frailty in Older Adults: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2019, 67, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergul, F.; Sackan, F.; Koc, A.; Guney, I.; Kizilarslanoglu, M.C. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in Turkish hospitalized older adults and its association with hospital clinical outcomes. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2021, 99, 104602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, M.W.; Chyun, D.A.; Skolnick, A.H.; Alexander, K.P.; Forman, D.E.; Kitzman, D.W.; Maurer, M.S.; McClurken, J.B.; Resnick, B.M.; Shen, W.K.; et al. Knowledge Gaps in Cardiovascular Care of the Older Adult Population. Circulation 2016, 133, 2103–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, L.J.; Moore, T.J.; Obarzanek, E.; Vollmer, W.M.; Svetkey, L.P.; Sacks, F.M.; Bray, G.A.; Vogt, T.M.; Cutler, J.A.; Windhauser, M.M.; et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 1997, 336, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, B.V.; Van Horn, L.; Hsia, J.; Manson, J.E.; Stefanick, M.L.; Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Kuller, L.H.; LaCroix, A.Z.; Langer, R.D.; Lasser, N.L.; et al. Low-Fat Dietary Pattern and Risk of Cardiovascular DiseaseThe Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA 2006, 295, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckland, G.; Mayén, A.L.; Agudo, A.; Travier, N.; Navarro, C.; Huerta, J.M.; Chirlaque, M.D.; Barricarte, A.; Ardanaz, E.; Moreno-Iribas, C.; et al. Olive oil intake and mortality within the Spanish population (EPIC-Spain). Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 96, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farras, M.; Valls, R.M.; Fernandez-Castillejo, S.; Giralt, M.; Sola, R.; Subirana, I.; Motilva, M.J.; Konstantinidou, V.; Covas, M.I.; Fito, M. Olive oil polyphenols enhance the expression of cholesterol efflux related genes in vivo in humans. A randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Biochem 2013, 24, 1334–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Aros, F.; Gomez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutierrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Li, J.; Hu, F.B.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Tobias, D.K. Effects of walnut consumption on blood lipids and other cardiovascular risk factors: an updated meta-analysis and systematic review of controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018, 108, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gensous, N.; Garagnani, P.; Santoro, A.; Giuliani, C.; Ostan, R.; Fabbri, C.; Milazzo, M.; Gentilini, D.; di Blasio, A.M.; Pietruszka, B.; et al. One-year Mediterranean diet promotes epigenetic rejuvenation with country- and sex-specific effects: a pilot study from the NU-AGE project. Geroscience, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorito, G.; Caini, S.; Palli, D.; Bendinelli, B.; Saieva, C.; Ermini, I.; Valentini, V.; Assedi, M.; Rizzolo, P.; Ambrogetti, D.; et al. DNA methylation-based biomarkers of aging were slowed down in a two-year diet and physical activity intervention trial: the DAMA study. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Dong, Y.; Bhagatwala, J.; Raed, A.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, H. Effects of Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Epigenetic Aging in Overweight and Obese African Americans With Suboptimal Vitamin D Status: A Randomized Clinical Trial. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 2019, 74, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Huan, T.; Joehanes, R.; McKeown, N.M.; Horvath, S.; Levy, D.; Ma, J. Higher diet quality relates to decelerated epigenetic aging. Am J Clin Nutr 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresovich, J.K.; Park, Y.M.; Keller, J.A.; Sandler, D.P.; Taylor, J.A. Healthy eating patterns and epigenetic measures of biological age. Am J Clin Nutr 2022, 115, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L.M.; Houston, D.K.; Skiba, M.B.; Whitsel, E.A.; Stewart, J.D.; Li, Y.; Zannas, A.S.; Assimes, T.L.; Horvath, S.; Bhatti, P.; et al. Diet Quality and Epigenetic Aging in the Women’s Health Initiative. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babio, N.; Toledo, E.; Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Castaner, O.; Bullo, M.; Corella, D.; Aros, F.; Gomez-Gracia, E.; et al. Mediterranean diets and metabolic syndrome status in the PREDIMED randomized trial. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne 2014, 186, E649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M. Pre-diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012, 59, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.G.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.C.; James, W.P.; Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C., Jr. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Or, B.; Tsoi, M.F.; Cheung, C.L.; Cheung, B.M.Y. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–18. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2023, 99, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.X.; Chaudhary, N.; Akinyemiju, T. Metabolic Syndrome Prevalence by Race/Ethnicity and Sex in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-2012. Preventing chronic disease 2017, 14, E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Barbagallo, M. The biology of the metabolic syndrome and aging. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2016, 19, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmannova, D.; Borsky, P.; Andrys, C.; Kremlacek, J.; Fiala, Z.; Parova, H.; Rehacek, V.; Esterkova, M.; Poctova, G.; Maresova, T.; et al. The Influence of Metabolic Syndrome on Potential Aging Biomarkers in Participants with Metabolic Syndrome Compared to Healthy Controls. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, C.; Bacos, K.; Rönn, T. Epigenetics of type 2 diabetes mellitus and weight change — a tool for precision medicine? Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2022, 18, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, D.G.A.; Faragher, R.G.A. Obesity and type-2 diabetes as inducers of premature cellular senescence and ageing. Biogerontology 2018, 19, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, A.E.; Bollati, V.; Favero, C.; Albetti, B.; Caroli, D.; Abbruzzese, L.; Cella, S.G.; Sartorio, A. Effect of a 3-Week Multidisciplinary Body Weight Reduction Program on the Epigenetic Age Acceleration in Obese Adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Föhr, T.; Hendrix, A.; Kankaanpää, A.; Laakkonen, E.K.; Kujala, U.; Pietiläinen, K.H.; Lehtimäki, T.; Kähönen, M.; Raitakari, O.; Wang, X.; et al. Metabolic syndrome and epigenetic aging: a twin study. International Journal of Obesity 2024, 48, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, A.; Levine, M.E.; Tanaka, T.; Lu, A.T.; Chen, B.H.; Ferrucci, L.; Ritz, B.; Bandinelli, S.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Beasley, J.M.; et al. Epigenetic clock analysis of diet, exercise, education, and lifestyle factors. Aging (Albany NY) 2017, 9, 419–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downer, M.K.; Gea, A.; Stampfer, M.; Sanchez-Tainta, A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Ros, E.; Estruch, R.; Fito, M.; Gomez-Gracia, E.; et al. Predictors of short- and long-term adherence with a Mediterranean-type diet intervention: the PREDIMED randomized trial. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 2016, 13, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Garcia-Arellano, A.; Toledo, E.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Corella, D.; Covas, M.I.; Schroder, H.; Aros, F.; Gomez-Gracia, E.; et al. A 14-item Mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: the PREDIMED trial. PLoS One 2012, 7, e43134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Conesa, M.T.; Philippou, E.; Pafilas, C.; Massaro, M.; Quarta, S.; Andrade, V.; Jorge, R.; Chervenkov, M.; Ivanova, T.; Dimitrova, D.; et al. Exploring the Validity of the 14-Item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS): A Cross-National Study in Seven European Countries around the Mediterranean Region. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, T.J.; Butcher, L.M.; Feber, A.; Teschendorff, A.E.; Chakravarthy, A.R.; Wojdacz, T.K.; Beck, S. ChAMP: 450k Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, W.E.; Li, C.; Rabinovic, A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 2007, 8, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).