Introduction

The brain's complex dynamics are inherently non-linear, with non-linearity arising even at the cellular level due to threshold and saturation phenomena in neuronal behavior (1). These non-linear properties extend to large-scale neural networks, where interactions among neurons give rise to emergent behaviors that cannot be fully captured by linear models. Electroencephalogram (EEG) signals are particularly valuable in neuroscience research due to their high temporal resolution, which enables the capture of rapid neural dynamics on the millisecond scale. This precision is crucial for studying the brain's non-linear and transient processes, as cognitive functions such as attention, memory, and sensory integration often unfold over very short time intervals (2). Historically, EEG analyses have heavily relied on linear methods focused on spectral power or averaged measures across time and frequency domains. While these approaches have provided critical insights into brain function, they often fail to capture the full complexity and temporal variability of neural processes, particularly those underlying cognitive tasks (3,4).

To address these limitations, non-linear methods have emerged as powerful tools for quantifying the irregularity and complexity of EEG signals. These measures are particularly adept at capturing dynamic changes in brain activity that occur during both physiological states and pathological conditions. For instance, fractal dimension analysis has been applied to study the spatiotemporal complexity of brain activity in Alzheimer's disease (5), epilepsy (6), and schizophrenia (4). Such methods provide unique insights into how neural networks adapt—or fail to adapt—to cognitive demands. Higuchi's Fractal Dimension (HFD), in particular, has proven effective for analyzing EEG signals due to its ability to quantify complexity directly in the time domain without requiring transformations into the frequency space (7,8).

In the context of schizophrenia, EEG studies have consistently highlighted widespread disruptions in neural connectivity and dynamic modulation, particularly during tasks requiring attention or memory retrieval (9,10). These disruptions are thought to stem from impairments in the brain's ability to dynamically reconfigure its functional networks in response to changing cognitive demands. However, many traditional EEG studies rely on static or averaged measures, which may obscure subtle but meaningful temporal fluctuations in neural complexity that are critical for understanding these impairments. For example, averaged power spectral analyses or event-related potentials (ERPs), while informative, often fail to capture the non-linear and transient nature of brain activity (2,11).

Recent advances in non-linear time-series analysis have provided powerful tools for exploring the temporal dynamics of brain activity. Unlike linear methods, which assume proportionality and constant relationships between variables, non-linear methods capture irregularities and emergent behaviors that are characteristic of brain activity (1). HFD quantifies the fractal complexity of EEG signals directly in the time domain, offering a sensitive measure of how neural complexity evolves dynamically over time (7). This method is particularly well-suited for studying schizophrenia, where abnormalities in neural complexity have been linked to core cognitive deficits, such as impaired working memory and attentional control (4,12). In a study, (13) showed that schizophrenic patients, when compared with control participants, exhibited less differentiated EEG complexity at different conscious states (external attention vs. mind wandering). This finding suggests that patients tend to show the same overall complexity pattern regardless of the specific mental state that they present. In the present study, we aim to explore whether this reduction of differentiation holds for attention and memory processes and whether a temporal evolution of complexity analysis adds new light on understanding EEG complexity patterns in schizophrenic patients.

The attention task consisted of presenting images with local landscapes to participants, and they needed to detect whether a small red dot appeared on the screen. In the memory task, the same type of images was presented, but in this case, participants were instructed to recall an event from their memory. Hence, our study builds on this growing body of research by applying HFD to analyze the temporal evolution of EEG complexity across different cortical regions during attentional (Dots) and memory-based (Remember) tasks in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia (SCZ) and healthy controls (CTRL). By focusing on temporal evolution rather than averaged measures, we aim to capture the dynamic modulation of neural networks underlying task-specific processing. We hypothesize that individuals with schizophrenia will exhibit reduced differentiation between tasks and less consistent patterns of neural complexity over time compared to controls. This approach highlights the importance of moving beyond traditional static analyses to better understand the disrupted dynamics of brain activity in schizophrenia.

The primary objective of this study was to identify significant differences in brain activity between the experimental conditions Dots and Remember using Higuchi's complexity metric. These differences were analyzed across temporal windows (Steps) and brain regions (Topologies) using a permutation-based Topographic Analysis of Variance (TANOVA). This approach was inspired in (14), allowing for robust statistical testing of differences while accounting for the spatial and temporal structure of EEG data.

Method

Participants

The sample included 21 individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia (SCZ) attending the Mental Health Day Unit at the University St. Agustin Hospital (Spain) and 17 healthy controls (HC).

In the SCZ group, 19% were women and 81% men. Mean of age was 36.476 (SD=8.256, Median: 34 [Min: 25 Max: 51]). For the SCZ participants the inclusion criteria were ICD-10 diagnosis of schizophrenia (F20) or psychotic disorder (F23). The educational level of the participants was categorized into three categories: Basic (Primary and Secondary Education), Medium (General Certificate of Education, Certificate of Higher Education), and High (University Degree). According to these categories, the sample of participants with SCZ included 57.1% participants with a basic educational level, 28.6% with a medium level and 14.3% with a high level.

In the HC group, 41% of participants were women and 59% were men. Mean of age was 41.7 (SD=13.1, Median: 38 [Min: 25 Max: 66]). This group included 35.3% with a basic educational level,41.2% with a medium level and 23.5% with a high level.

There was neither a significant association between group and education level (χ² (4, N = 38) = 6.209, p = .184), nor between sex and group (χ² (1, N = 38) = 2.237, p = .135), nor did the groups differ significantly with respect to age (t=1.500; p =.142).

Exclusion criteria for all groups were: concurrent diagnosis of neurological disorder, concurrent diagnosis of substance abuse, history of developmental disability, inability to sign informed consent or vision disorders (those vision disorders which, although corrected by glasses or contact lenses, suppose a loss of visual acuity, e.g., cataracts). In addition, an exclusion criterion for the HC group was the diagnosis of a mental disorder (according to verbal reports from participants). All participants gave their written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethics Committee on Human Research of the Hospital approved the study.

Procedure

The experiment was carried out in one session in the laboratory of the Mental Health Department at San Agustín Hospital in Linares. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study, in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the hospital. Participants were seated at a distance of approximately 70 cm from a computer screen. A set of 64 active electrodes was then placed on the participants' scalps, with electrode impedance maintained below 5 kΩ.

Participants in this study performed two tasks while their EEG activity was recorded with an AD rate of 500 Hz. The experimental tasks were carried out in the same order for all participants. First, they performed a sustained attention task, and subsequently, within the same experimental session and after a 5-minute break, they completed a recall task.

In the sustained attention task (Dots) participants were shown a series of neutral images (landscapes) on a computer screen. Each image was displayed for 10 seconds. In 50% of the trials, a red dot appeared randomly at any location on the screen. Participants were instructed to press a designated key as soon as they detected the red dot. The task comprised 40 trials in total: 20 trials in which the red dot was present and 20 trials without it. The trials with a dot and without a dot were presented in random order. Following the dot detection task, participants completed a memory task (Remember). During this phase, the same set of images was presented again on the screen, 10 seconds each. Participants were instructed to observe each image and allow their thoughts to wander freely to any memory, regardless of whether it was related to the content of the image. This task consisted of 20 trials.

Each trial was divided into 40 temporal windows of 2 seconds each one, referred henceforth to as steps. Each step overlapped the 90% of the time with the previous one. These steps represent consecutive time intervals during which Higuchi's fractal dimension (HFD) was calculated for EEG signals recorded from the 63 electrode channels referenced to the Cz electrode site. The trials were grouped by experimental conditions (Dots and Remember), and the electrodes were further categorized into five brain regions or topologies: Frontal, Central, Occipital, Parietal, and Temporal. Below is a detailed description of how the channels were assigned to each topology.

The Frontal topology included 16 electrodes positioned over the anterior region of the scalp. These regions have been associated with higher-order cognitive functions such as decision-making, attention, and working memory (15). The assigned electrodes were Fp1, Fp2, AF7, AF3, AFz, AF4, AF8, F7, F3, Fz, F4, F8, F1, F5, F6, and F2. This configuration provided comprehensive coverage of both lateralized and midline frontal activity.

The Central topology comprised 13 electrodes located near the central midline of the scalp. This region is primarily involved in motor control and somatosensory processing (16). The assigned electrodes were FC5, FC1, FCz, FC2, FC6, C3, C4, C1, C5, C2, FC3, C6, and FC4. This grouping ensured that activity from both hemispheres and the central sulcus was adequately represented.

The Parietal topology included 16 electrodes positioned over the parietal cortex, which is associated with sensory integration, spatial reasoning, and attention (17). The assigned electrodes were CP5, CP1, CPz, CP2, CP6, P3, P4, Pz, P1, P2, P5, P6, P7, P8, CP3, and CP4.

The Occipital topology consisted of 8 electrodes placed over the posterior region of the scalp, corresponding to areas responsible for visual processing (18). The assigned electrodes were O1, Oz, O2, PO7, PO3, POz, PO4, and PO8. These channels captured activity related to visual stimuli and integration.

The Temporal topology included 10 electrodes located over the lateral temporal regions of the scalp. These regions are involved in auditory processing, language comprehension, and memory functions (19,20). The assigned electrodes were T7, T8, TP9, TP10, FT9, FT10, FT7, FT8, TP7, and TP8. This grouping ensured bilateral coverage of temporal activity.

The assignment of channels to topologies was based on standard EEG electrode placement systems (e.g., the 10-20) and their correspondence to underlying cortical regions. This grouping facilitated region-specific analyses while maintaining consistency with established neuroanatomical landmarks (21).

Data Processing, Analysis, and Results

Data processing was conducted using Brain Vision Analyzer, EEGLAB, and MATLAB. Blinks and other artifacts were removed using infomax ICA. ICA components containing artifacts were identified by visual inspection of the scalp topography, power spectra and raw activity from all components. Once the noisy components were selected, they were removed from the original signals.

The cleaned EEG signals were then used as inputs for a custom MATLAB script developed to calculate Higuchi’s fractal dimension (HFD) as a measure of signal complexity over time. This non-linear approach provides insight into brain activity dynamics by capturing variations in signal complexity (7). HFD is computed by segmenting the time series at different scales and determining the fractal dimension based on the relationship between segment length and signal amplitude. Higher HFD values indicate greater EEG complexity, often associated with increased neural activity, greater neural network engagement, and higher cognitive demands. Conversely, lower HFD values reflect more regular or predictable activity, typically observed during resting states or under reduced cognitive load. For this experiment, we calculated a single HFD estimation for each trial using a sliding window procedure (n= 40 windows or steps).

We have structured our analyses and results into two main sections. First, we present dynamic analyses that explicitly consider the temporal dimension of complexity differences between experimental tasks for controls. Second, we introduce the equivalent analyses for participants with schizophrenia.

Control Participants

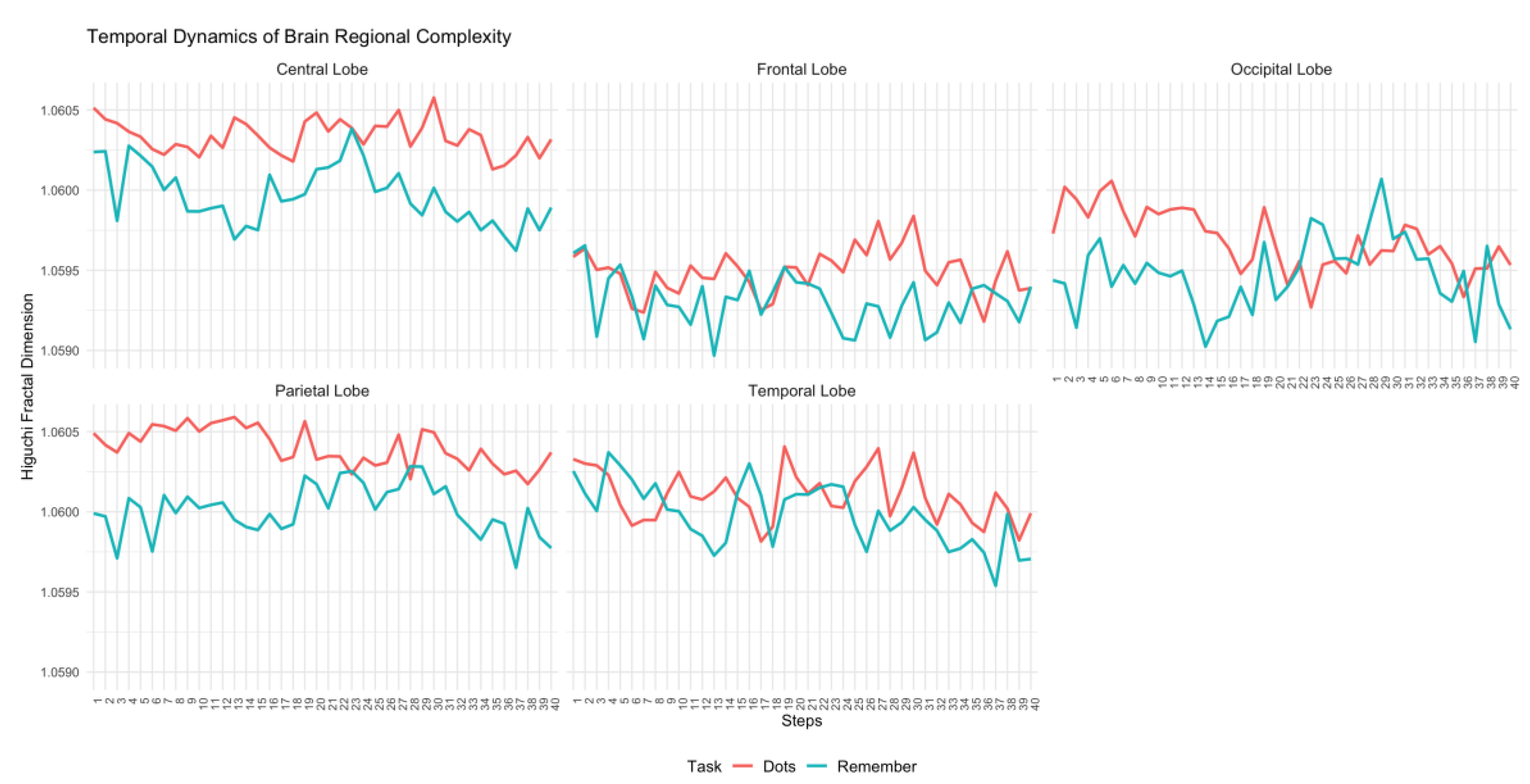

For each topology, we computed the mean Higuchi fractal dimension across all subjects and trials for each task (Dots and Remember). These mean values illustrate the temporal evolution of complexity within a typical trial. The results are shown in

Figure 1.

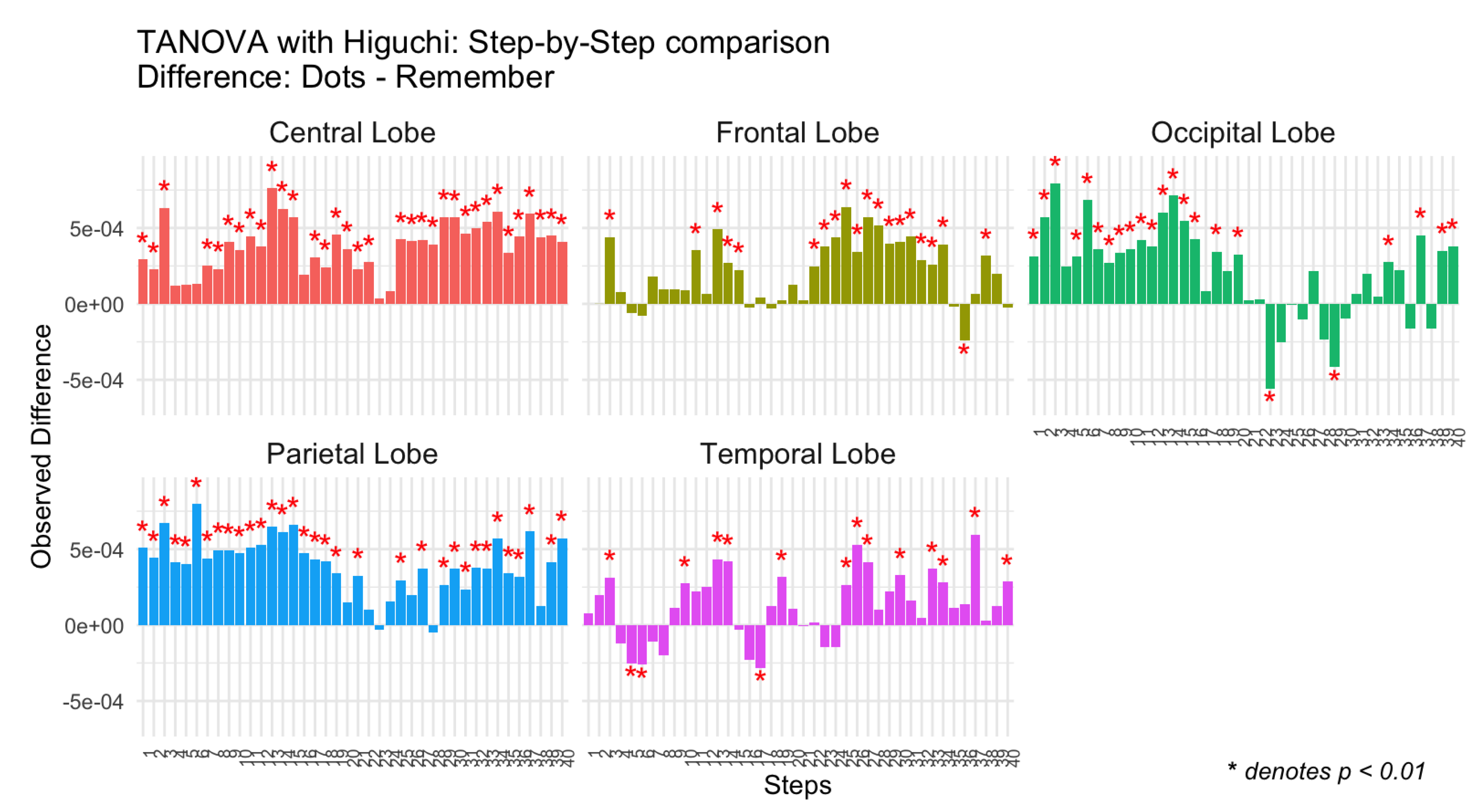

Next, for each combination of Step and Topology, the mean difference in Higuchi complexity between the conditions (Dots and Remember) was calculated. These differences provided a measure of the observed effect size for each temporal window and brain region.

A permutation-based approach was employed to test the statistical significance of the observed differences. Condition labels (Dots and Remember) were randomly shuffled within each experimental condition (Step and Topology). For each permutation, the mean difference was recalculated. This process was repeated 1,000 times to generate a null distribution of differences. The null distribution allowed us to estimate the likelihood that the observed differences occurred by chance.

For each combination of Step and Topology, p-values were calculated as the proportion of permuted differences, that were greater than or equal to the absolute value of the observed difference. To control for Type I error due to multiple comparisons, False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction was applied using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (22).

The results can be visualized as bar plots, with each bar representing the observed difference for a specific combination of Step and Topology (See

Figure 2). Significant differences were highlighted with red asterisks above or below, depending on the sign, the corresponding bars. The visualization included separate panels for each brain region (Topology).

As can be seen in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, control participants exhibited a consistent temporal pattern of higher complexity during the attentional task, compared to the memory task. This is especially evident in central, frontal and parietal regions. In the occipital and temporal regions, there were a few specific moments when complexity was higher during the memory task, but for most periods of time, complexity was higher in the attentional task.

Participants with Schizophrenia

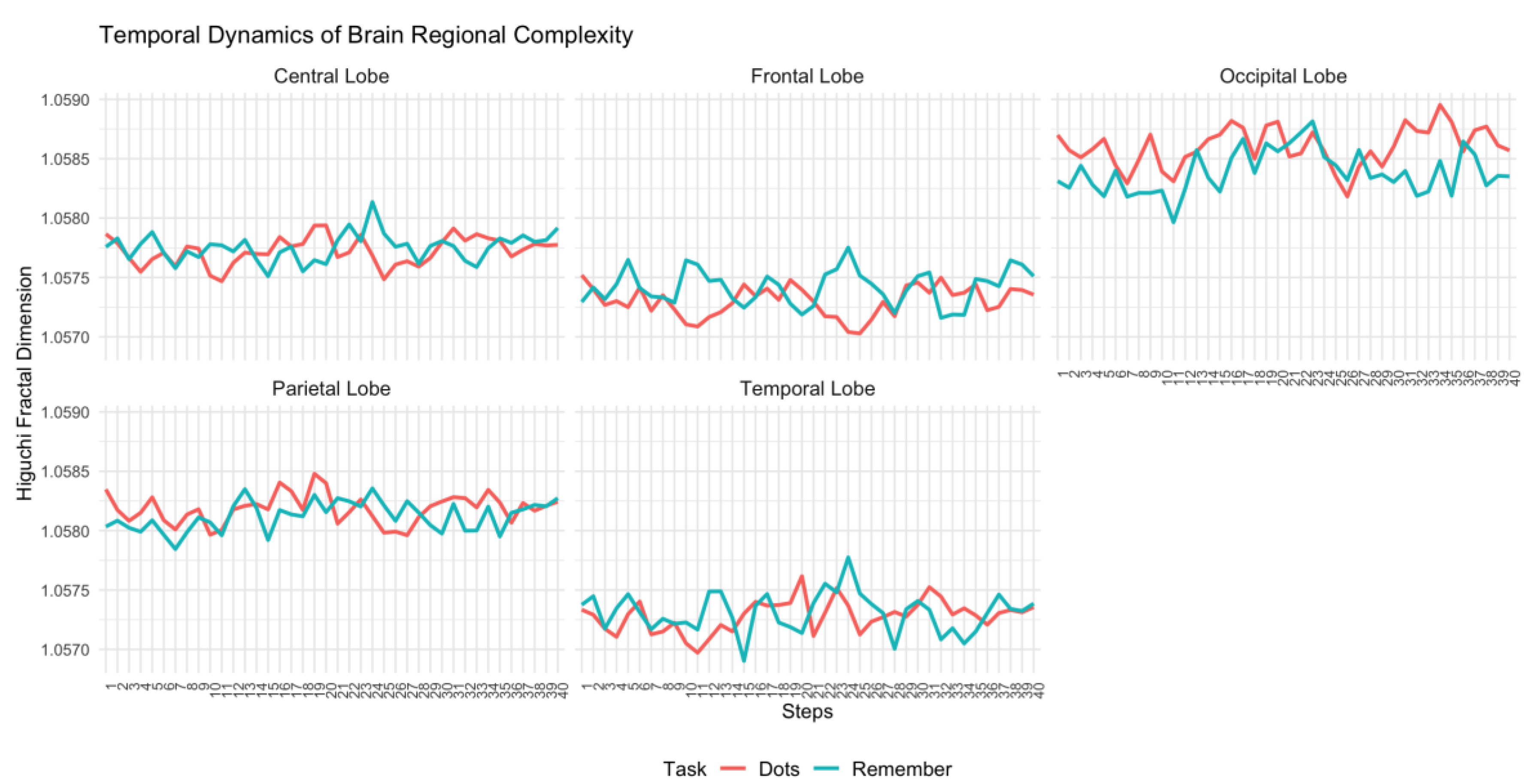

For the sample of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, the same analyses were conducted to examine the temporal evolution of complexity during task performance. Specifically, for each topology, the mean Higuchi fractal dimension across all subjects and trials was computed for each task (Dots and Remember). The results for this sample are presented in

Figure 3.

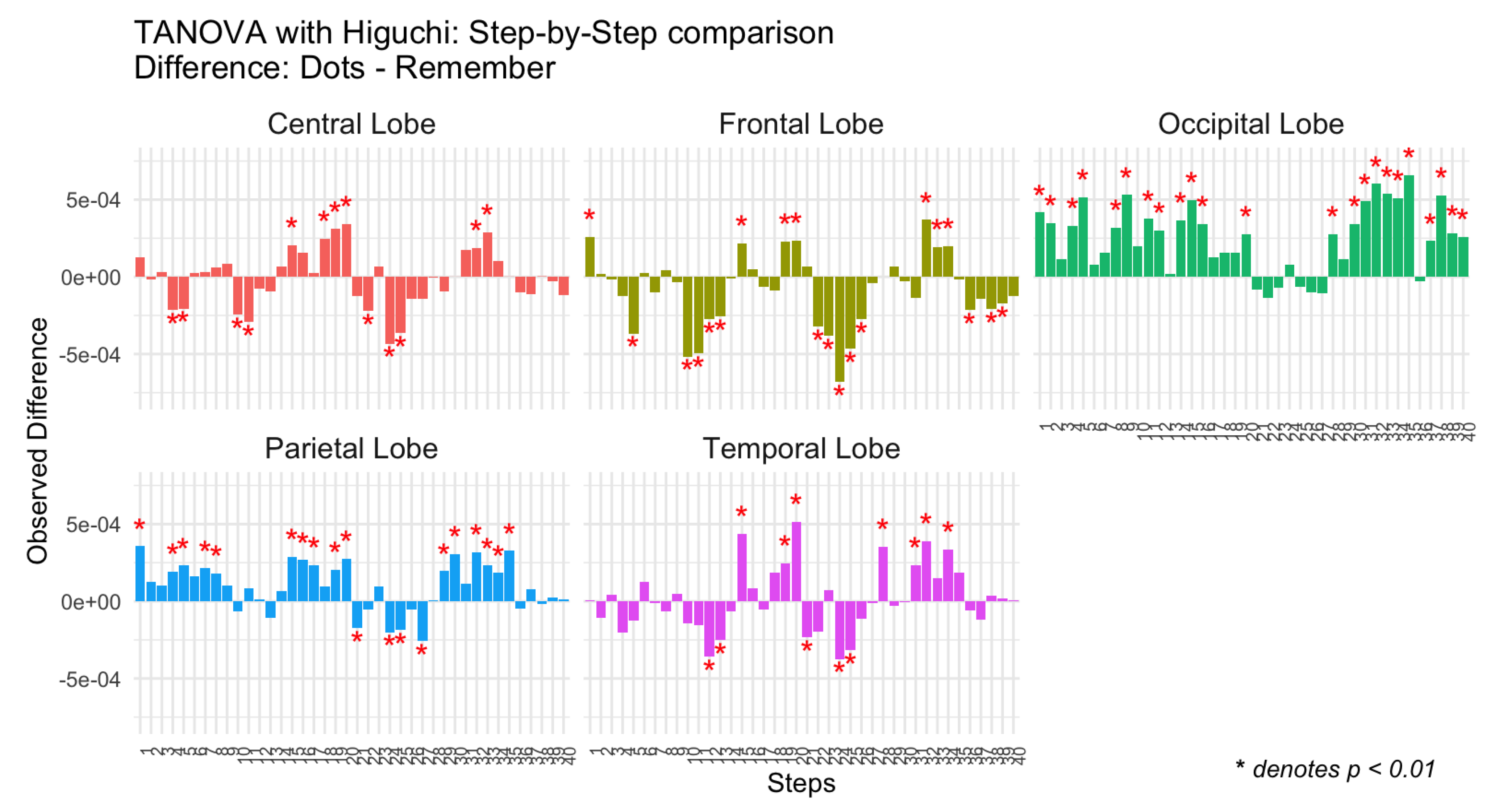

Next, for each combination of Step and Topology, the mean difference in Higuchi complexity between the two conditions (Dots and Remember) was calculated.

The results are presented in bar plots (

Figure 4), where each bar represents the observed difference for a specific combination of Step and Topology. Significant differences are marked with red asterisks. As with the control group, separate panels are included for each brain region (Topology) to facilitate comparison. Positive differences indicate greater complexity during the attentional task (Dots), while negative differences reflect greater complexity during the memory task (Remember).

As can be seen in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, in the group of patients, the pattern of differences in complexity between tasks is much more inconsistent. In all brain regions, complexity was higher during the attentional task in some temporal steps and lower during the attentional task in other temporal steps; and this temporal variability does not seem to adjust to any significant pattern. Temporal inconsistency is specially marked in central, frontal and temporal regions.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the temporal dynamics of EEG complexity during an attentional and memory task in healthy controls and patients with schizophrenia. Previous research has shown a reduced differentiation of EEG complexity between cognitive tasks in patients with schizophrenia compared to controls (13). These findings suggest that patients exhibit a diminished ability of the brain to dynamically adjust its functioning to meet the cognitive demands of the task. In this experimental design, we aimed to further explore brain dynamics by analyzing the temporal evolution of complexity across different cognitive tasks.

Consistent with our hypothesis, patients and controls showed differences in the temporal patterns of EEG complexity. Healthy controls exhibited a highly regular temporal pattern, showing increased complexity during the attentional task consistently over time. However, in the group of patients, differences in complexity between tasks varied inconsistently over time. This variability likely accounts for the reduced complexity differences between tasks reported in previous research: unpredictable fluctuations in patients' EEG complexity levels (sometimes higher, sometimes lower) result in a smaller average difference between tasks.

To our knowledge, this finding of high temporal inconsistency in complexity among patients is entirely novel. It supports the notion that patients with schizophrenia have impaired modulation of brain complexity in response to task demands and struggle to adjust brain dynamics to the task at hand.

Now, we will discuss this differences between patients and controls according to brain regions of interest (central, frontal, occipital, parietal, and temporal lobes).

Central, Parietal and Frontal Lobe

We have grouped the discussion of results in these regions, since findings are similar across them both in controls and in patients. The CTRL group consistently shows significant positive differences favoring the attentional task. This result may be reflecting efficient somatosensory integration and motor control, as well as executive high order processes, necessary for attentional tasks (23). In contrast, the SCZ group exhibits inconsistent patterns of neural complexity differences between tasks, with both positive and negative differences observed. The presence of negative differences in the SCZ group, which are absent in the CTRL group, suggests that individuals with schizophrenia may struggle to maintain stable neural complexity across tasks. This variability could reflect compensatory mechanisms or disruptions in connectivity that impair their ability to dynamically adapt to cognitive demands (9,12). The presence of negative differences in the SCZ group is particularly intriguing because it indicates greater neural complexity during the memory compared to the attentional task, an atypical pattern not observed in the CTRL group. This may suggest that individuals with schizophrenia require additional neural engagement during memory-based tasks to compensate for deficits in episodic memory retrieval or sensory integration. Such findings align with prior research indicating that schizophrenia is associated with altered connectivity and reduced efficiency in neural networks responsible for attention and memory (9,16). As we have mentioned before, these findings support the idea that in schizophrenia there is a disruption in neural modulation, leading to both reduced differentiation between tasks and unexpected shifts in cortical complexity. Further investigation into these negative differences could provide valuable insights into the compensatory mechanisms at play in schizophrenia and how they influence cognitive performance.

Occipital and Temporal Lobes

In Occipital and Temporal Lobes, the temporal pattern of differences was more similar in controls and patients. In the control group, negative and positive differences in complexity could be observed, especially in temporal regions. That is, in some temporal steps there was higher complexity in the attentional task and in some others, there was higher complexity in the memory task, possibly reflecting the role of temporal regions in episodic memory retrieval through interactions with the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (24,27). Patients with schizophrenia showed also negative and positive difference, although again the pattern was more irregular and variable.

On the whole, our findings support prior research indicating that schizophrenia is associated with deficits in sensory integration and attentional control (9,21,25). It is reasonable to think that this inability to modulate brain activity on function of task contributes to difficulties prioritizing external stimuli versus internal representations which are key deficits observed in schizophrenia (25).

Limitations

The study has certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The relatively small sample size, may limit the generalizability of the results to broader populations. Future studies with larger and more diverse samples could provide additional insights and strengthen the conclusions drawn here. Additionally, the experimental tasks were performed in a fixed order for all participants, which might introduce potential order effects, such as fatigue or learning (although the temporal pattern during each task did not show fatigue or learning effects). While Higuchi’s Fractal Dimension (HFD) is a robust tool for analyzing EEG complexity, it is worth noting that it provides an overall measure of signal complexity without distinguishing between specific neural processes. The division of trials into 40 temporal windows allowed for detailed temporal analysis but may not fully capture rapid fluctuations in neural complexity at finer scales. Exploring alternative methods with even higher temporal resolution could complement these findings in future research. Finally, EEG inherently has limited spatial resolution compared to imaging techniques like fMRI. Although this study focused on cortical regions using well-established electrode groupings, future investigations combining EEG with other neuroimaging modalities could provide a more comprehensive understanding of neural dynamics. Despite these considerations, the study’s innovative use of HFD to explore temporal dynamics in schizophrenia offers valuable insights into neural complexity and task-specific modulation. In addition to HFD, future studies could benefit from incorporating other nonlinear and dynamic measures to analyze EEG complexity in schizophrenia. For instance, indices such as approximate entropy, multiscale entropy, or nonlinear correlation coefficients may provide complementary insights into the underlying neural dynamics.

Conclusions

Our results highlight significant differences in the dynamics of cortical activity between the CTRL and SCZ groups across various brain regions, emphasizing how schizophrenia disrupts task-specific neural modulation. In the CTRL group, cortical regions such as the central, frontal, occipital, parietal, and temporal lobes demonstrate dynamic and efficient neural responses tailored to the demands of the attention-focused and memory-based tasks. These findings align with prior research indicating that healthy individuals exhibit robust neural flexibility, allowing them to allocate resources appropriately for sensory integration, attentional control, and episodic memory retrieval (23,24,27).

In contrast, the SCZ group shows reduced differentiation between tasks across all cortical regions analyzed. This diminished task-specific modulation reflects impairments in sensory integration, attentional control, and memory retrieval—core cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia. For example, the parietal lobe shows fewer significant differences between tasks in patients with schizophrenia, suggesting difficulties in integrating multisensory information and directing attention effectively (10,26). The frontal lobe also exhibits reduced modulation in SCZ participants, likely due to disrupted connectivity with other cortical regions such as the hippocampus, key for episodic memory retrieval and contextual integration (24,25).

Overall, these findings underscore widespread disruptions in neural networks in schizophrenia, highlighting the critical role of connectivity impairments in cognitive dysfunctions observed in this population.

The findings of this study could have significant clinical implications. Temporal differences in cortical activity may serve as neurophysiological biomarkers for the diagnosis of schizophrenia, the assessment of disease progression, and the evaluation of treatment response (28,29). Identifying reliable biomarkers is essential for improving early detection and personalized treatment approaches. Therefore, future research should focus on integrating multimodal biomarkers to enhance diagnostic accuracy and optimize therapeutic strategies for schizophrenia. Likewise, these findings could serve as a starting point for future studies on other mental disorders, expanding the understanding of neurophysiological mechanisms beyond schizophrenia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rosa Molina, Yasmina Crespo-Cobo, Francisco J. Esteban, Ana Victoria Arias, Javier Rodríguez-Árbol, Maria Felipa Soriano, Antonio J. Ibañez-Molina and Sergio Iglesias-Parro; Data curation, Rosa Molina, Yasmina Crespo-Cobo, Francisco J. Esteban, Ana Victoria Arias, Javier Rodríguez-Árbol, Maria Felipa Soriano, Antonio J. Ibañez-Molina and Sergio Iglesias-Parro; Formal analysis, Rosa Molina, Yasmina Crespo-Cobo, Francisco J. Esteban, Ana Victoria Arias, Javier Rodríguez-Árbol, Maria Felipa Soriano, Antonio J. Ibañez-Molina and Sergio Iglesias-Parro; Funding acquisition, Maria Felipa Soriano and Sergio Iglesias-Parro; Investigation, Rosa Molina, Yasmina Crespo-Cobo, Francisco J. Esteban, Ana Victoria Arias, Javier Rodríguez-Árbol, Maria Felipa Soriano, Antonio J. Ibañez-Molina and Sergio Iglesias-Parro; Methodology, Rosa Molina, Yasmina Crespo-Cobo, Francisco J. Esteban, Ana Victoria Arias, Javier Rodríguez-Árbol, Maria Felipa Soriano, Antonio J. Ibañez-Molina and Sergio Iglesias-Parro; Project administration, Antonio J. Ibañez-Molina; Resources, Rosa Molina, Yasmina Crespo-Cobo, Francisco J. Esteban, Ana Victoria Arias, Javier Rodríguez-Árbol, Maria Felipa Soriano, Antonio J. Ibañez-Molina and Sergio Iglesias-Parro; Software, Rosa Molina, Yasmina Crespo-Cobo, Francisco J. Esteban, Ana Victoria Arias, Javier Rodríguez-Árbol, Maria Felipa Soriano, Antonio J. Ibañez-Molina and Sergio Iglesias-Parro; Supervision, Antonio J. Ibañez-Molina and Sergio Iglesias-Parro; Validation, Rosa Molina, Yasmina Crespo-Cobo, Francisco J. Esteban, Ana Victoria Arias, Javier Rodríguez-Árbol, Maria Felipa Soriano, Antonio J. Ibañez-Molina and Sergio Iglesias-Parro; Visualization, Rosa Molina and Yasmina Crespo-Cobo; Writing – original draft, Rosa Molina and Yasmina Crespo-Cobo; Writing – review & editing, Francisco J. Esteban and Antonio J. Ibañez-Molina.

Funding

This research receives funding from the University of Jaén (PAIUJA-EI_CTS02_2023) and the Regional Government of Andalusia (RH-0055-2021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Province of Jaén (Protocol number: AP-0033-2020-C1-F2 / 0032-N-21, approved on February 25, 2021). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all participants provided written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting this study has been deposited in FigShare and is publicly available for other researchers. The dataset can be accessed via the following DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.28304096 (

https://figshare.com/ndownloader/files/52005371).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kantz H, Schreiber T. Nonlinear Time Series Analysis. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [CrossRef]

- Pfurtscheller G, Lopes Da Silva FH. Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: Basic principles. Vol. 110, Clinical Neurophysiology. 1999. [CrossRef]

- Pincus, SM. Approximate entropy as a measure of system complexity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(6). [CrossRef]

- Ruiz de Miras J, Ibáñez-Molina AJ, Soriano MF, Iglesias-Parro S. Fractal dimension analysis of resting state functional networks in schizophrenia from EEG signals. Front Hum Neurosci. 2023;17. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J. EEG dynamics in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Neurophysiol [Internet]. 2004;115(7):1490–505. [CrossRef]

- Babloyantz A, Destexhe A. Low-dimensional chaos in an instance of epilepsy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(10). [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T. Approach to an irregular time series on the basis of the fractal theory. Physica D. 1988;31(2):277–83. [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra BS, Dutt DN, Halahalli HN, John JP. Complexity analysis of EEG in patients with schizophrenia using fractal dimension. Physiol Meas. 2009;30(8). [CrossRef]

- Barch DM, Ceaser A. Cognition in schizophrenia: Core psychological and neural mechanisms. Vol. 16, Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Fornito A, Zalesky A, Breakspear M. The connectomics of brain disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015 Mar;16(3):159–72. [CrossRef]

- Jeong J, Chae JH, Kim SY, Han SH. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of the EEG in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2001;18(1). [CrossRef]

- Kristensen TD, Ambrosen KS, Raghava JM, Syeda WT, Dhollander T, Lemvigh CK, et al. Structural and functional connectivity in relation to executive functions in antipsychotic-naïve patients with first episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia 2024 10:1 [Internet]. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Parro S, Soriano MF, Prieto M, Rodríguez I, Aznarte JI, Ibáñez-Molina AJ. Introspective and Neurophysiological Measures of Mind Wandering in Schizophrenia. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):4833. [CrossRef]

- Murray MM, Brunet D, Michel CM. Topographic ERP analyses: A step-by-step tutorial review. Vol. 20, Brain Topography. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Vol. 24, Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Fornia L, Leonetti A, Puglisi G, Rossi M, Viganò L, Della Santa B, et al. The parietal architecture binding cognition to sensorimotor integration: a multimodal causal study. Brain. 2024;147(1). [CrossRef]

- Culham JC, Kanwisher NG. Neuroimaging of cognitive functions in human parietal cortex. Vol. 11, Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Grill-Spector K, Malach R. The human visual cortex. Vol. 27, Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Binder JR, Desai RH. The neurobiology of semantic memory. Vol. 15, Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011. PMID: 22001867.

- Bonilha L, Hillis AE, Hickok G, Den Ouden DB, Rorden C, Fridriksson J. Temporal lobe networks supporting the comprehension of spoken words. Brain. 2017;140(9). [CrossRef]

- Koessler L, Maillard L, Benhadid A, Vignal JP, Felblinger J, Vespignani H, et al. Automated cortical projection of EEG sensors: Anatomical correlation via the international 10-10 system. Neuroimage. 2009;46(1). [CrossRef]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling The False Discovery Rate - A Practical And Powerful Approach To Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal statistical Society Series B (Methodological). 1995;57(1):289–300. [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, M. Dynamical complexity in small-world networks of spiking neurons. Phys Rev E [Internet]. 2008;78(4):41924. [CrossRef]

- Gazzaley A, Nobre AC. Top-down modulation: Bridging selective attention and working memory. Vol. 16, Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Ragland JD, Ranganath C, Harms MP, Barch DM, Gold JM, Layher E, et al. Functional and Neuroanatomic Specificity of Episodic Memory Dysfunction in Schizophrenia: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of the Relational and Item-Specific Encoding Task. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Bisley JW, Goldberg ME. Attention, intention, and priority in the parietal lobe. Vol. 33, Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Squire LR, Wixted JT. The cognitive neuroscience of human memory since H.M. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34. PMID: 21456960.

- Kim HK, Blumberger DM, Daskalakis ZJ. Neurophysiological Biomarkers in Schizophrenia-P50, Mismatch Negativity, and TMS-EMG and TMS-EEG. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Aug 7;11:795. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Light GA, Swerdlow NR. Future clinical uses of neurophysiological biomarkers to predict and monitor treatment response for schizophrenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015 May;1344(1):105-19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).