1. Introduction

Epinephrine or adrenaline (4-[(1R)-1-hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl]benzene-1,2-diol) (AD) is an important neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system. This catecholamine act as chemical mediator for transferring nerve impulses to different organs, thereby controlling its performance in biological reactions and nervous chemical processes. Epinephrine is biologically synthetized in the adrenal medulla and abnormal level concentrations may cause several diseases such as myocardial infarction and hypoglycaemia [

1]. It also plays a key role in the correct functioning of the central nervous and cardiovascular systems. Since catecholamines are redox active species, electrochemical methods are adequate to study their electron transfer oxidation reactions [

2]

,[

3]. In this context, the modification of electrodes by polymers, represents a powerful strategy to immobilize catalyst that extend their electrochemical capabilities to promote charge transport, avoid surface fouling and prevent undesirable reactions in the detection of biological systems. Perfluorinated-ionomer membranes are promising as matrixes to bound electroactive catalysts quite readily. The surface immobilization of redox catalyst in perfluorosulfonated polymers, is an excellent strategy to improve charge transport and to produce composite functional materials with suitable electrocatalytical and optical properties. The immobilization of redox species such as Ru(II) complexes has found possible applications as catalyst [

4], light-harvesting materials in hybrid photovoltaic cells [

5], electroluminescent materials [

6], selective and sensitive sensors for dopamine [

7],[

8] and histidine in living bodies [

9]. Recently a Ru(III) Schiff base complex was explored as adrenaline sensor [

10].

Among the family of perfluorinated membranes, Nafion

® has been extensively studied as an electrode modifier in voltammetric sensors [

11]

,[

12]. Nevertheless, it has one unfortunate drawback related to the slow diffusion process of some chemical species through it. Nafion

® has highly acidic sulfonic groups where inorganic phases can be grown [

13]. Considering this, Murata and Noyori [

14] first reported the silylation of Nafion (Nafion-TMS). By introducing the trimethylsilyl group, we found that the Naf-TMS polymer modified electrodes, display good ion permeation and faster diffusion for electroactive species [

15]. In electrochemical sensing, molecular and charge transport are fundamental and compulsory phenomena for an efficient performance.

In this work, we use the previous reported method to dissolve Naf-TMS solid polymer Error! Bookmark not defined., to prepare Naf-TMS modified electrodes for the electroanalytical detection of adrenaline in standard solutions. Additionally, composite membranes are prepared based on Naf-TMS and Ru-complex ([Ru(bpy)3]2+ and [Ru(phen)3]2+) to construct electrodes for adrenaline sensing. To the best of the authors knowledge, there is no report about the use of Naf-TMS and Naf-TMS/Ru-complex as sensor for adrenaline. Moreover, Naf-TMS represents a nice approach to develop composite hybrid materials for electrocatalysis in general. Further, during the last year, Nafion® a trademark from DuPontTM, has been less and less available from the common suppliers. Then, the need to find suitable alternatives for electrode modifiers and catalysts supports, calls for the research in this direction.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals

Adrenaline (Epinephrine, (R)-(−)-3,4-Dihydroxy-α-(methylaminomethyl) benzyl alcohol), dopamine hydrochloride (3-Hydroxytyramine hydrochloride), CH3CH2OH (Baker), H2SO4 (Merck), HNa2PO4·12H2O (Merck), H2NaPO4·H2O (Merck), H2SO4 (Merck) were all analytical reagent grade and used as received without any further purification. Naf-TMS was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich in the form of polymer beads. Ruthenium complexes, C36H24Cl2N6Ru·xH2O ([Ru(phen)3]2+, dichlorotris (1,10-phenanthroline) ruthenium(II) hydrate, 98 %), C30H24Cl2N6Ru·6H2O ([Ru(bpy)3]2+ Tris (2,2′-bipyridyl) ruthenium(II) chloride hexahydrate) were also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Solutions were prepared with Milli-Q (18.2 MΩ) deionized water just before each experiment. The corresponding working solutions were prepared from appropriate dilution in the corresponding electrolyte at a given pH (either H2SO4 or phosphate buffer solution).

2.2. Naf–TMS Dissolution Process and Preparation of Naf-TMS/Ru-Complexes Films

Previously, we have reported the dissolution of Naf-TMS Error! Bookmark not defined.. Accordingly, to prepare a 5 % Naf-TMS solution, corresponding amount of small pellets of the clean polymer was placed in a beaker containing a 50:50 ethanol–water mixture, then transferred to a containing solvent high-pressure reactor which was purged with Ar and heated at 250° C during 2 hours. The resulting solution was slightly viscous and transparent. Naf-TMS films were prepared by deposition of an aliquot of the polymeric solution onto an electrode or a glass substrate, and the solvent was allowed to evaporate at room temperature.

To incorporate Ru-complexes (Ru(phen)3]2+ and [Ru(bpy)3]2+) into the Naf-TMS polymer, two methods were used. Method 1 consisted of the incorporation of the Ru-complex through electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions by simply immersing the polymer into a 1 mM Ru-complex containing solution. Method 2 involved one-pot incorporation and was done using the same procedure for the dissolution process of Naf-TMS, but it was added 1 mM of Ru-complex to the high-pressure reactor. The insertion by the former method was followed by UV-vis spectroscopy.

2.3. Surface Characterization

Structural analysis of Naf-TMS was performed by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) employing a Nanosurf Naio-AFM microscope (Nanosurf, Liestal, Switzerland) provided with silicon carbide tips and the measurements were done in contact mode. The measurements were performed in air, under a static force operating mode with a set point of 55 nN.

2.4. Spectroscopic Measurements

The mechanism loading of the Ru-complex into the Naf-TMS polymer was followed by absorption spectroscopy. Surface bound UV-Vis spectra were recorded on a UV-Vis-NIR Cary Varian spectrophotometer employing a wavelength from 300 to 800 nm. All measurements were performed with a film at ambient conditions employing the transmission technique. The measurement were done under the absorption mode.

2.5. Electrode Preparation and Electrochemical Measurements

A glassy carbon (GC) electrode was used as substrate to deposit Naf-TMS or Naf-TMS/Ru-complex. Previous to the deposition, the electrode was polished using diamond paste of 3 and 0.5 μm diameter successively. After, it was rinsed with acetone and cleaned abundantly with Milli-Q (18 MΩ) deionized water for several times in an ultrasonic bath. After removed from water, it was coated by depositing a 10 μL aliquot of the corresponding Naf-TMS or Naf-TMS/Ru-complex solution and the solvent was evaporated at room temperature.

The electrochemical measurements were carried out with an Epsilon (Bioanalytical Systems) potentiostat–galvanostat and the BASi-Epsilon EC (ver. 2.13.77) software was used for control and data acquisition. All experiments were performed using a three-electrode glass cell with GC, GC/Naf–TMS or GC/Naf–TMS/Ru complex as working electrode, the counter electrode was a Pt coiled-wire and Ag/AgCl was used as the reference electrode.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Structure of Naf-TMS

One of the merits of Naf-TMS is its capability to insert certain amounts of catalysts by electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions

Error! Bookmark not defined..This capability could be related to its structural properties which are expected to be similar to those of its relative polymer, Nafion [

16]

,[

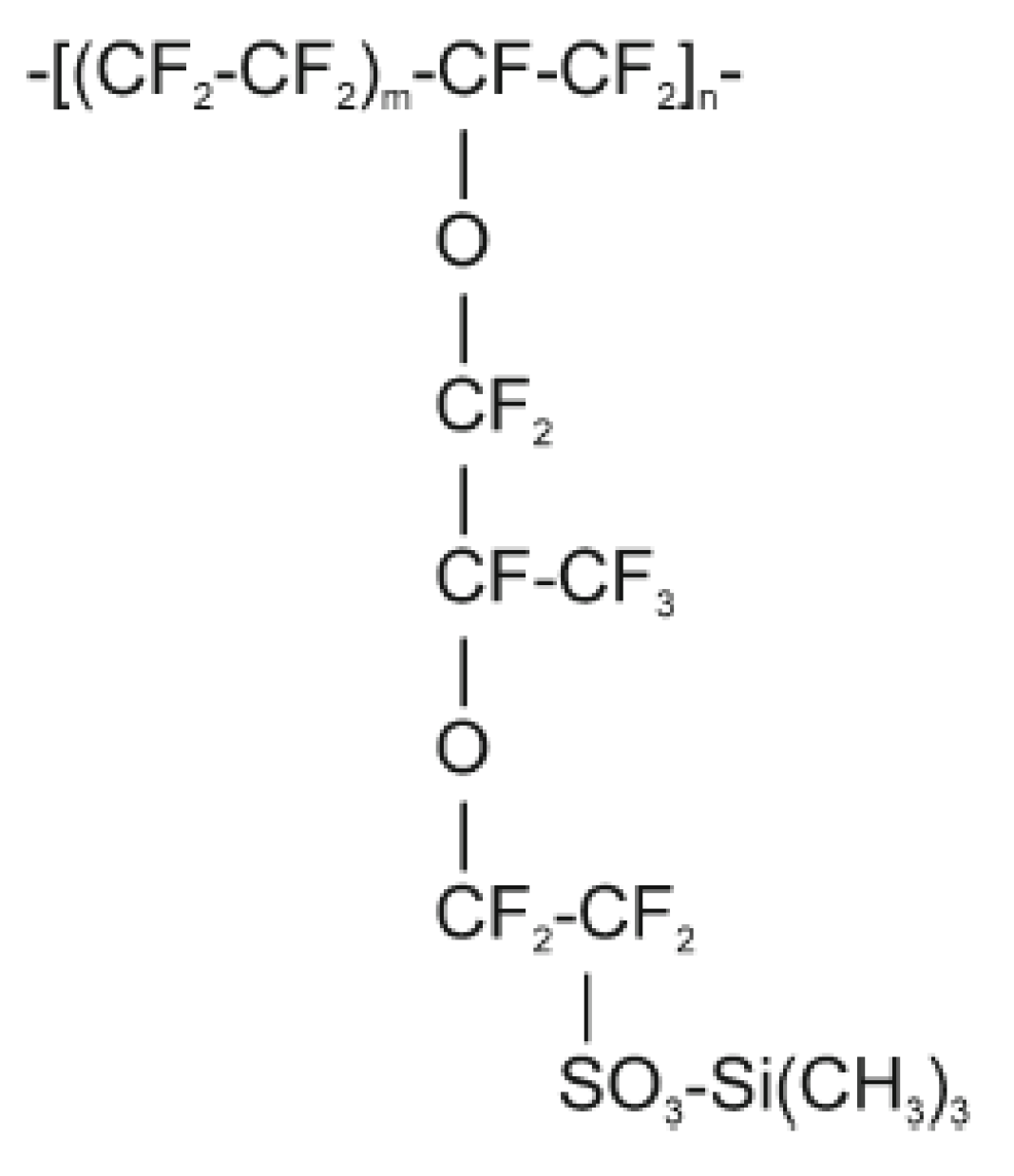

17]. The chemical structure (

Scheme 1) of Naf-TMS

Error! Bookmark not defined. shows a teflon-like backbone and an acidic side chain with a trimethylsilyl group. Then, it is anticipated that the morphological structure of Naf-TMS would be consistent with aggregated semi-crystalline type regions (hydrophilic) combined with non-crystalline areas (hydrophobic). These components phase-separate to form a network of hydrophilic channels imbedded in a hydrophobic fluorocarbon matrix at a nanometer scale.

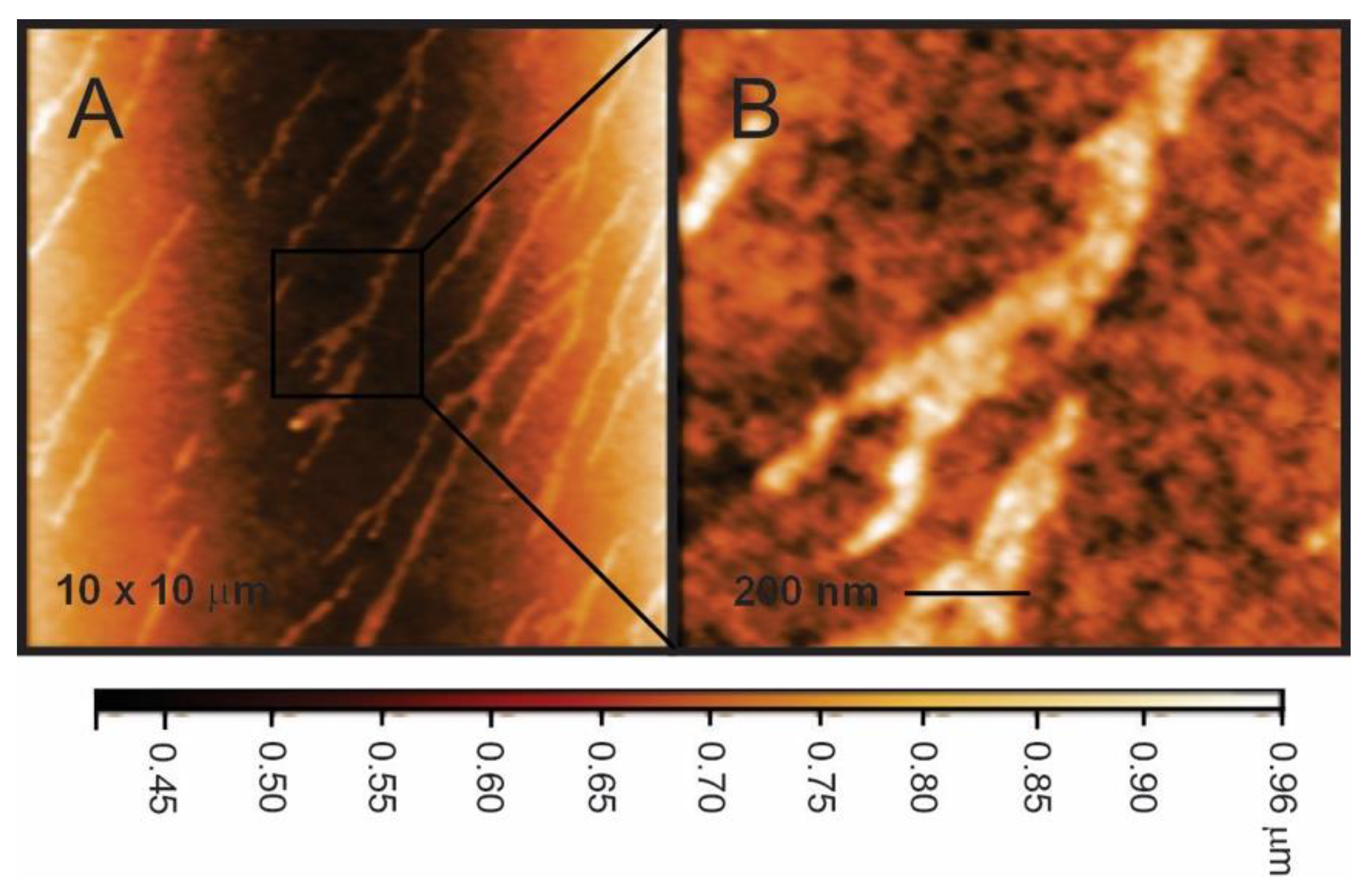

Figure 1 shows representative AFM images of Naf-TMS films deposited on glass substrates and dried in air during 24 hours. The morphology of Naf-TMS showed a 2D-type microstructure, whereby the polar microphase, composed of clustered ionic groups, exists as long-branched oriented channels (80-150 nm wide approximately) embedded in a continuous matrix. Some contrast can be derived from different stiffness in the material; dark regions would correspond to “softer” areas and bright regions would correspond to rich crystalline ionic domains. From the line fit (color intensity bar) at the bottom of figure 1 and from the height profiles, it can be inferred that the height of the clusters are about 400 nm. Currently, we are performing a detailed structural study of Naf-TMS and Naf-TMS/Ru-complex.

3.2. Insertion of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ and [Ru(phen)3]2+ Complexes in Naf-TMS

Immobilization of Ru-complex into Naf-TMS membranes was performed via a one-step method (see experimental part). However, in an effort to account for the interaction and mechanism involved in the immobilization process, we carried out a spectrophotometric study during the incorporation of [Ru(bpy)

3]

2+ and [Ru(phen)

3]

2+ complexes into Naf-TMS polymer with time.

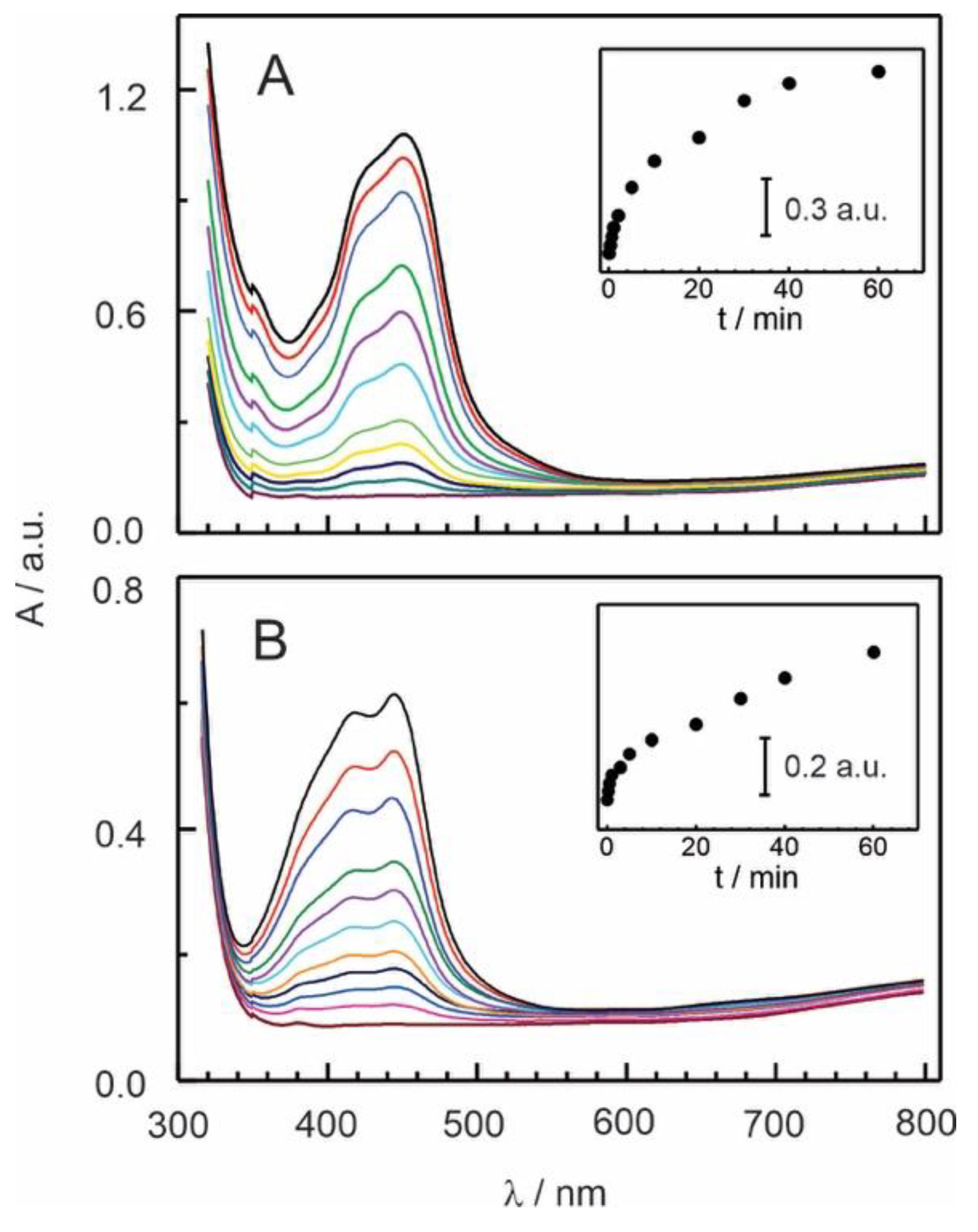

Figure 2 shows UV-Vis spectra of [Ru(bpy)

3]

2+ and [Ru(phen)

3]

2+ while being incorporated into Naf-TMS. The study was done with Naf-TMS membranes which were in contact with a 1 mM Ru-complex aqueous solution for a certain time. The UV-vis spectra show a low energy band positioned at approximately 455 nm which can be assigned to metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) transition[

18] by comparing the spectra to standard Ru complexes. As can be observed, the signal exhibited continuous increasing at longer immersion times as the complex was loaded into the film. The incorporation of [Ru(bpy)

3]

2+ is markedly faster and in greater quantities than the observed for [Ru(phen)

3]

2+ as its absorbance response was more rapid and much higher. This can be attributed to a faster diffusion of [Ru(bpy)

3]

2+ in comparison to [Ru(phen)

3]

2+ in the Naf-TMS polymer, which correlates well with its shape, size and hydrophobicity

Error! Bookmark not defined.,[

19,

20,

21]. As the ligand of the complex is more hydrophobic, its interaction with the polymer is stronger and therefore it diffuses slowly through the film. This strengths the assumption that interactions inside Naf-TMS are of both type, hydrophilic and hydrophobic.

3.3. Electrochemical Detection of Adrenaline at GC/Naf-TMS Modified Electrodes

The analytical properties of Naf-TMS as an electrode modifier were studied through the electrooxidation reaction of adrenaline (AD), by measuring the peak current as a function of concentration in standard analyte solutions at several pHs [

22].

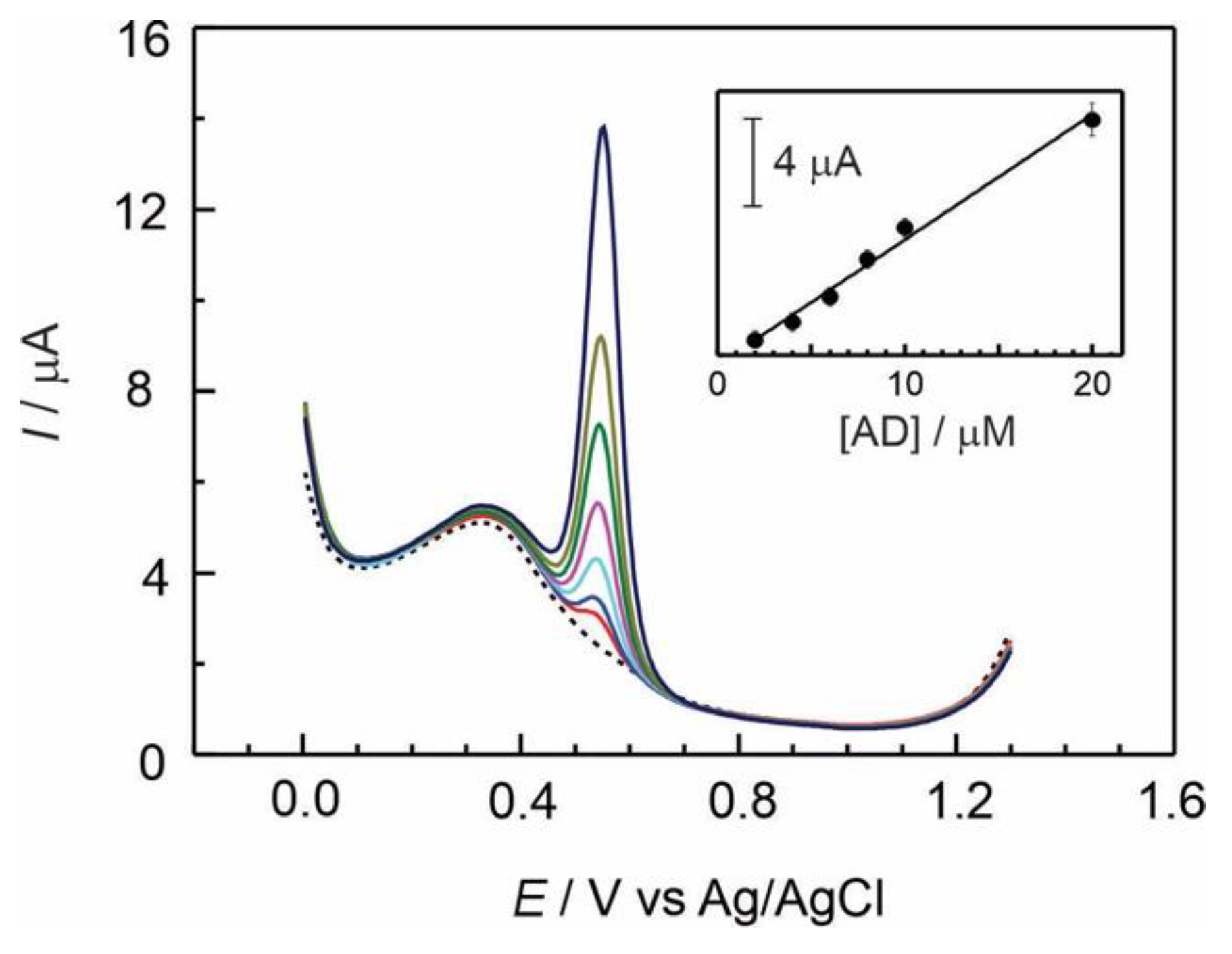

Figure 3 represents a series of differential pulse voltammograms registered at a GC/Naf-TMS modified electrode at micromolar concentrations of AD in 0.1 M sulphuric acid, in a potential window from 0 to 1.3 V versus Ag/AgCl reference electrode. A sharp well-defined redox signal was observed at about 550 mV which can be related to the redox reaction shown in

scheme 2. The electrode reaction involves a two-electron process, which is accompanied by a transfer of two protons, and is highly dependent on the pH solution. The inset of figure 3, presents the current linear response of ADR with increasing concentration in the range from 2 to 20 micromolar yielding a sensitivity of 0.57±0.027 μA/μM. The analytical parameters are reported in

Table 1.

Effect of pH

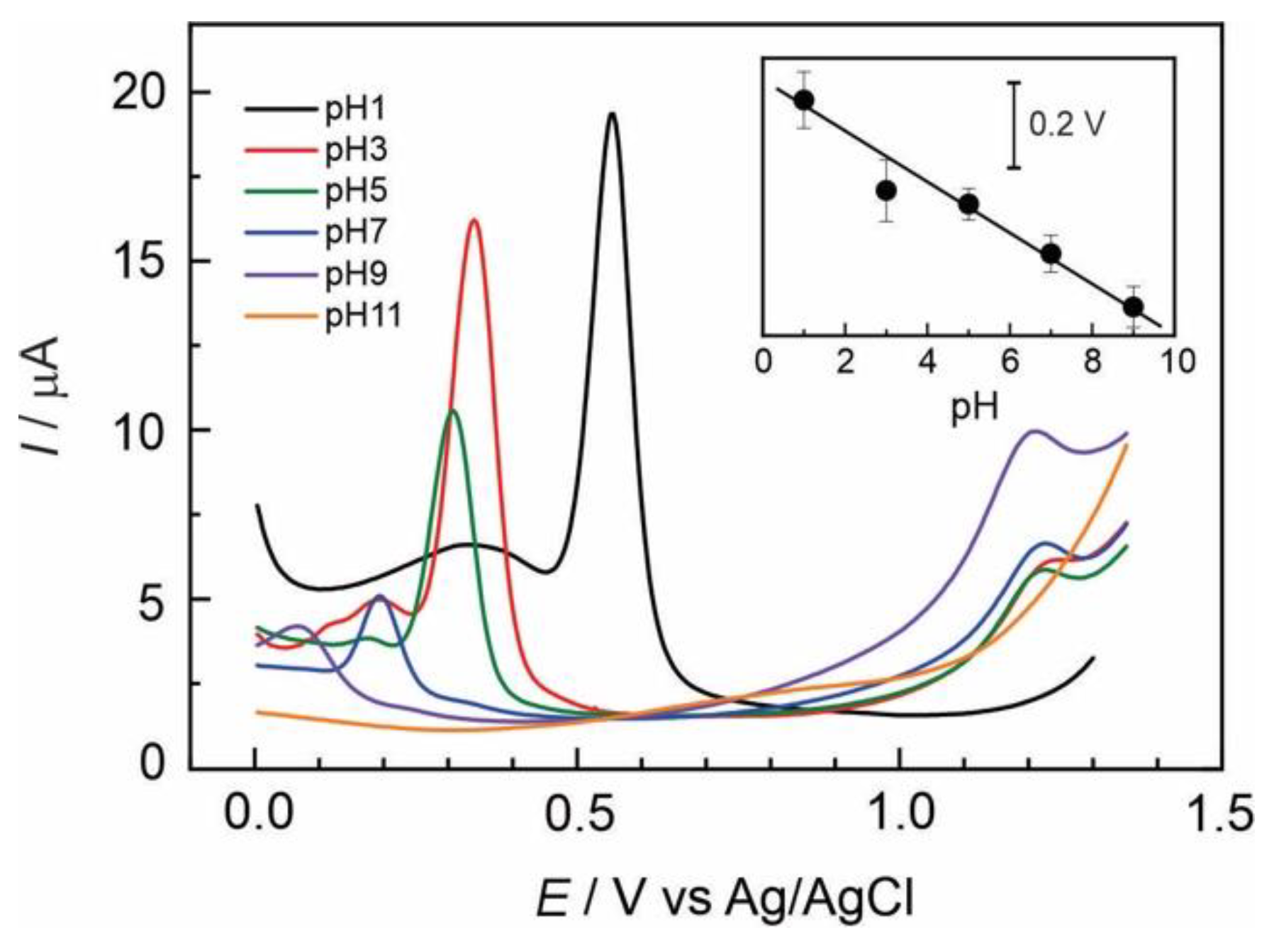

It is well-known that electrochemical characteristics of catecholamines are highly dependent on pH. The effect of the pH on the voltammetric determination of AD was examined over various pH values ranging from 1 to 11.

Figure 4 shows a series of differential pulse voltammograms recorded for 2×10

-5 mol L

-1 AD at several pH values using a GC/Naf-TMS modified electrode. The peak potential of adrenaline oxidation presents a linear dependence with pH. A negative shifting in the oxidation peak potential occurred with increasing pH, following a Nernstian behaviour as evidenced by the slope of the linear dependence shown in the inset of figure 4. This slope was -56

mV/pH-unit, very close to the ideal Nernstian behaviour (-59

mV/pH), and similar to the performance registered for dopamine at several pH´s

Error! Bookmark not defined.. Usually, this phenomenon is due to pure thermodynamic conditions, but also it could indicate that electron transfer reaction occurs in tandem with proton transfer and depends on proton concentration.

In the pH interval from 3 to 9 it was observed a small oxidation peak, appearing about 1.22 V which current increases with pH values. Usually above pH 3, the presence of the unprotonated form of adrenaline quinone allows for the cyclization reaction of adrenaline to further form the adrenochrome [

23]. Under either strongly acidic (pH 1) or basic conditions (pH 11), the oxidation peak at 1.22 V completely disappeared. Also the mean oxidation peak of adrenaline is not observed at high pH values, this is understandable since adrenaline tends to be totally oxidized in aqueous solution at pH higher than 10 [

24]. This study is helpful at the time one considerates the analytical conditions for adrenaline sensing under physiological conditions.

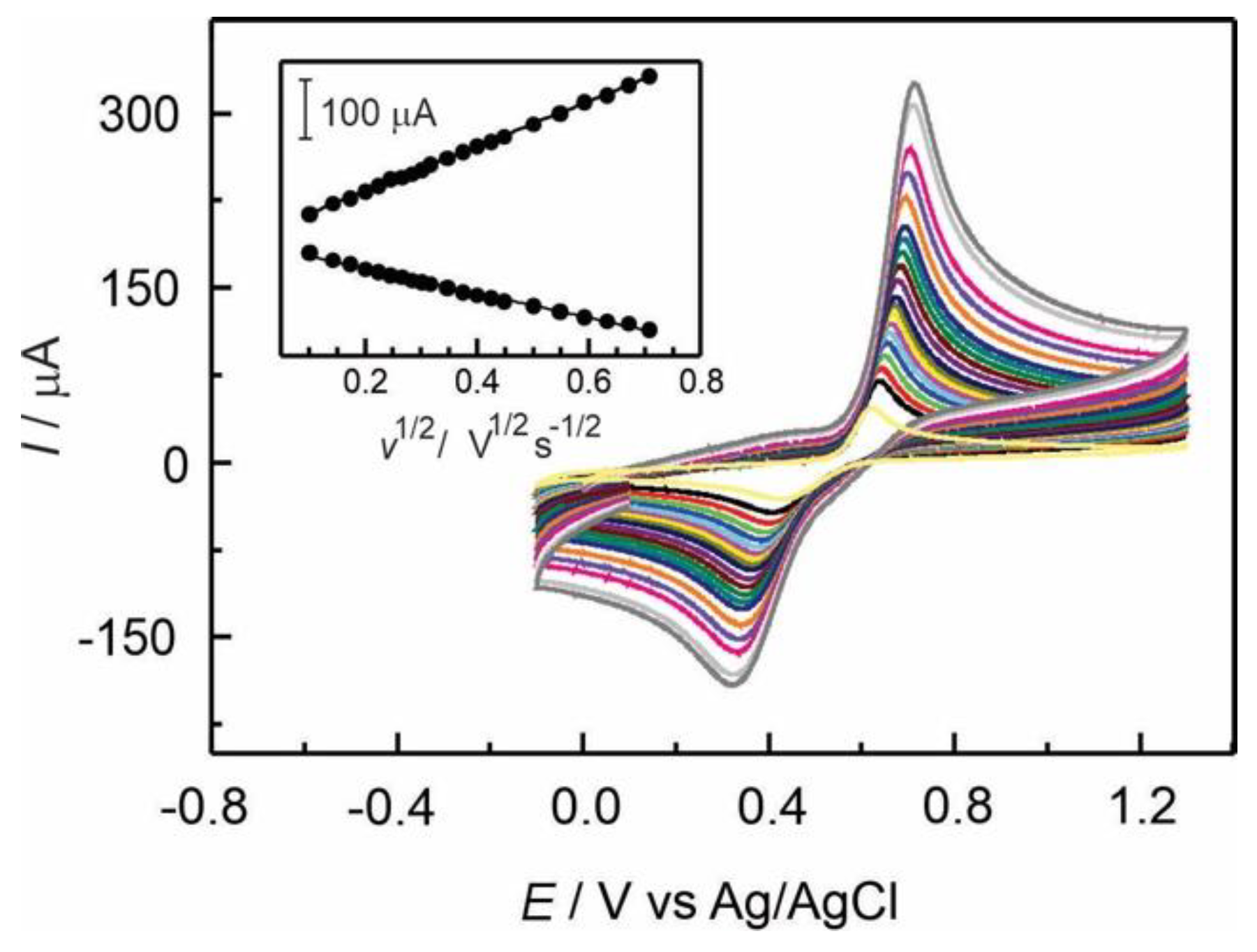

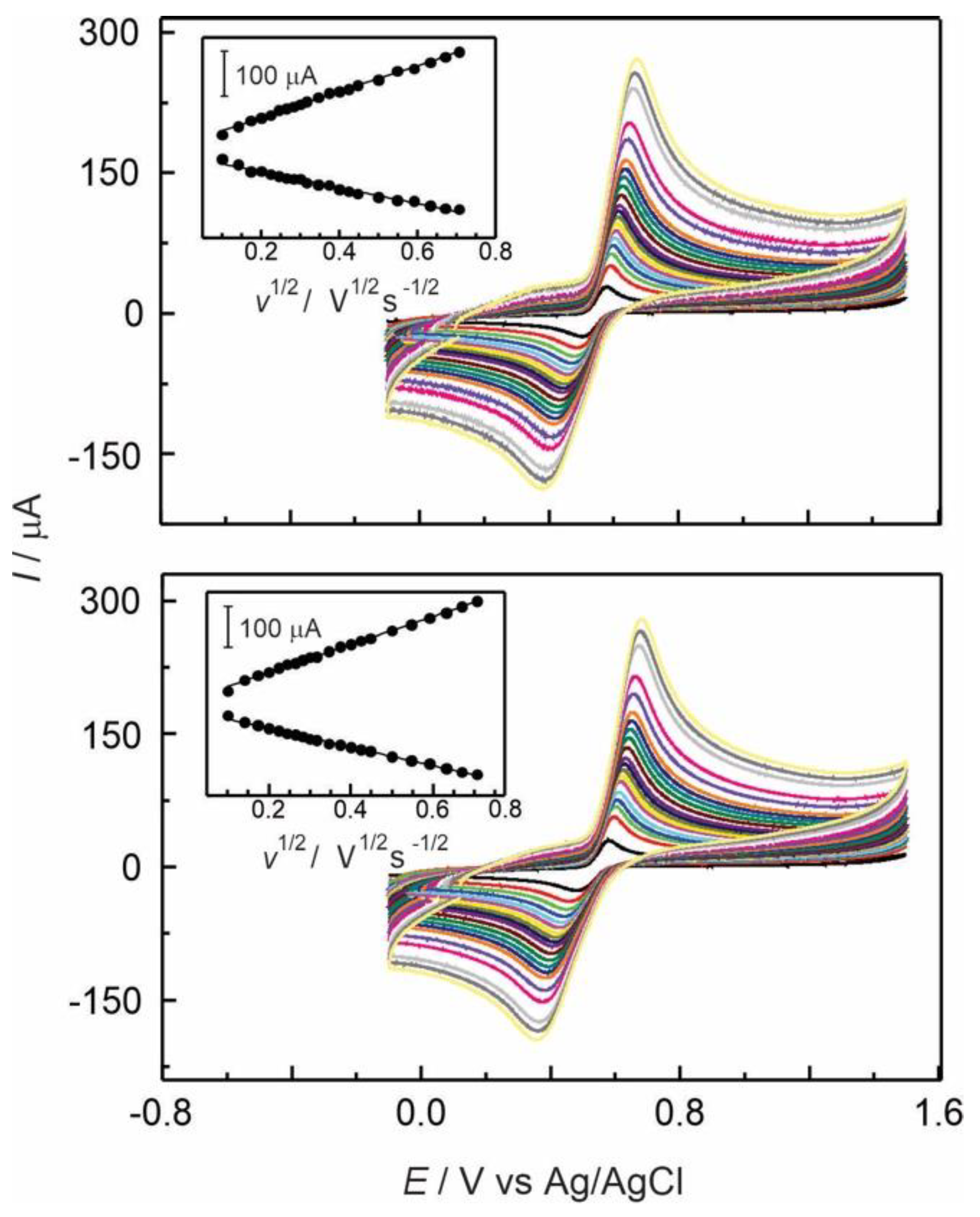

The effect of scan rate on adrenaline oxidation was studied by cyclic voltammetry using a GC/Naf-TMS modified electrode at a concentration of 2×10

-4 mol L

-1 AD in 0.1 M H

2SO

4. As can be seen in figure 5, both the anodic and cathodic peak currents increase linearly with square root of the scan rate (

v1/2) indicating that diffusion was the main mass transport mechanism through the layer. By using the Randles-Sevcik equation (Eq. 1) [

25] and from the slope of the inset shown in figure 5, the diffusion coefficient was calculated providing a value of 7.9(±0.5)×10

-5 cm

2 s

-1 as reported in

table 1.

The results suggest that the electrochemical behaviour of AD is predominantly a diffusion-controlled process on Naf-TMS modified electrodes [

26]

, [

27].

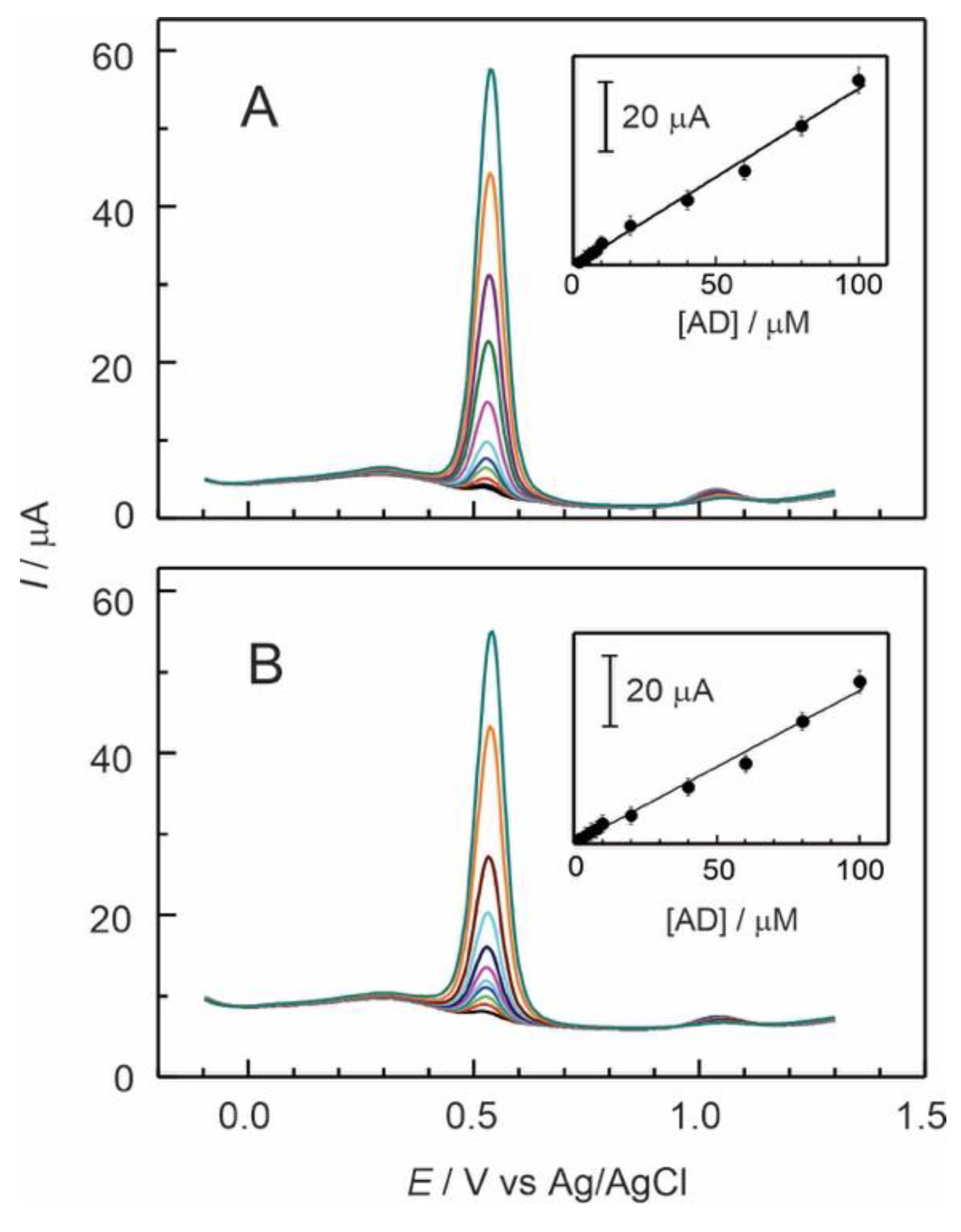

3.4. Electrochemical Detection of Adrenaline Using GC/Naf-TMS-Ru-Complex Modified Electrodes

By combining the features of polymers and electrocatalyst, as Ru-complex, composite membranes help to improve the kinetics of electrochemical reactions and the characteristics of electrode surfaces to develop successful electrochemical sensors. The analytical capabilities of GC/Naf-TMS/Ru-complex modified electrodes were evaluated by measuring the peak current as a function of adrenaline concentration in standard solutions.

Figures 5A and

5B show the first scan of differential pulse voltammograms recorded at GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(bpy)

3]

2+ and GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(phen)

3]

2+ modified electrodes respectively, for several adrenaline concentrations ranging from 2×10

-6 to 1×10

-4 mol L

-1 in 0.1 M H

2SO

4. It was observed an oxidation signal at approximately 0.53 V, corresponding with the electrooxidation of adrenaline, for both Ru-complex modified electrodes. The large oxidation currents exhibited by these electrodes suggest that the Ru-complexes have enhanced electrocatalytic behaviour towards oxidation of adrenaline. Even the sensitivity and the detection limit were similar to that for Naf-TMS electrodes (

Table 1), it was observed a sharper and well-defined peak with a considerable improvement in linear dependence along a wider interval concentration for Ru-complex modified Naf-TMS. All this characteristics can be attributed to fast electron transfer [

28] mediated by Ru, as also observed from cyclic voltammetry (see below).

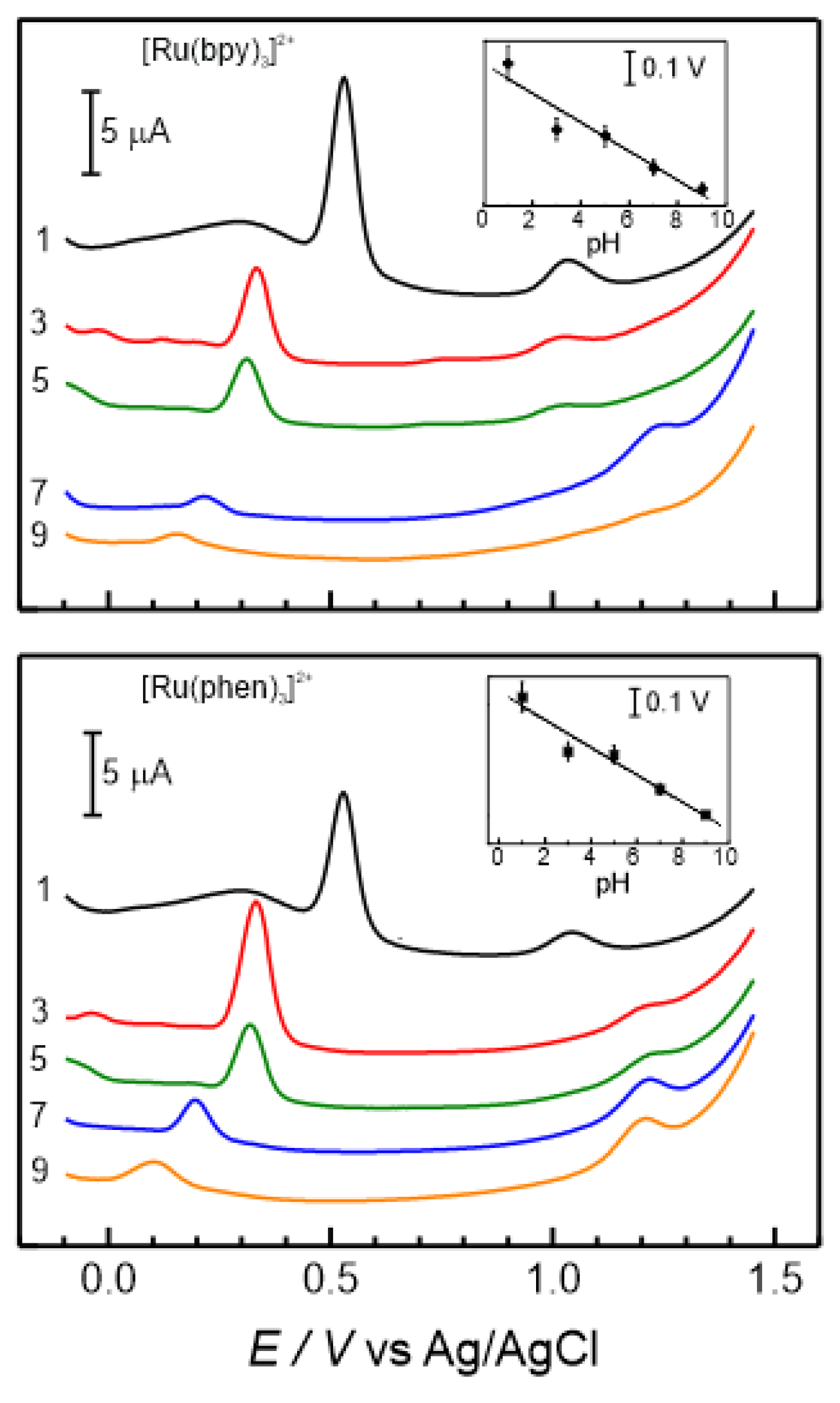

It was found that the oxidation potential values, as well as the peak current, largely depend on the pH of the electrolyte.

Figure 6 shows the electrochemical responses measured at different pH values with GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(bpy)

3]

2+ and GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(phen)

3]

2+ modified electrodes in presence of 2×10

-5 M adrenaline. For both electrodes, the adrenaline oxidation current decreases, the peak potential shifts to more negative values and presents a quasi-linear dependence with increasing pH (insets of figure 7) of the solution. Although the plots of potential versus pH for both electrodes, show a small deviation from the thermodynamic Nernstian behaviour with corresponding slopes values of -44

mV/pH-unit and -49

mV/pH-unit respectively, this suggest a proton-dependent rate limiting process. An issue that draws attention is the fact that at pH 3, either for Naf-TMS and Naf-TMS/Ru-complex modified electrodes, the adrenaline oxidation potential shifts to more negative values than the expected for a Nernstian dependence (insets of figure 4 and 7). It seems that at this pH the oxidation reaction presents a major influence from proton gradients [

29] and the energy needed for the oxidation reaction is slightly optimized in a mildly acidic solution. This is important to find out the best analytical conditions for the electrochemical sensing of biologically significant catecholamines.

At pH 1, the redox signal for Ru

2+ to Ru

3+ oxidation reaction is observed around 1.03 V for both Ru modified electrodes (

Figure 7). Nevertheless, for the [Ru(bpy)

3]

2+ electrode, it remains up to pH 5, but not for the [Ru(phen)

3]

2+ modified electrode. This is understandable since phenantroline ligand is more basic than bipyridine ligand at room temperature [

30]. Another important point to note is that the peak originally appearing at 1.23 V, corresponding to the unprotonated form of the adrenaline quinone, is not observed at pHs 3 and 5 on the electrode modified with [Ru(bpy)

3]

2+, but it does appear for [Ru(phen)

3]

2+. These facts provides an idea of pH-controlled cross-linking between adrenaline and [Ru(bpy)

3]

2+. Nevertheless, this issue is out of the scope of this work and we will further study it because it represents a good approach for the formation of self-healing polymer composite networks [

31] and one can explore the possibility to maintain the activity of the composite Naf-TMS/Ru-complex polymer at acidic pHs.

The nature of the electrochemical oxidation of adrenaline on GC/Naf-TMS/Ru-complex electrodes in H

2SO

4, was studied by cyclic voltammetry at different scan rates. It is worth to note that for Naf-TMS electrodes, the difference in potential between oxidation and reduction signals obtained by cyclic voltammetry, is far (approximately 312 mV,

Figure 5) from an expected Nernst reversible behaviour. However, for the Ru-complex modified electrodes this difference is much smaller (see

Table 1), which reflects a faster electron transfer and greatly different kinetic values for the redox reaction.

For both Ru-complex modified electrodes, the anodic and cathodic current followed a linear dependence with the square root of scan rate in a range from 10 to 500 mV s

-1 at 2×10

-4 mol L

-1 adrenaline constant concentration. This correlates well with a process that is limited by the molecular diffusion of the reactant from the bulk solution to the electrode. The apparent diffusion coefficient of adrenaline through Naf-TMS/Ru-complex films was estimated from the peak current of the voltammograms using the Randles-Sevcik equation

Error! Bookmark not defined.. It is worth to note that the diffusion coefficient of adrenaline obtained with GC/Naf-TMS/Ru-complex is in the same order of magnitude that the one found for GC/Naf-TMS. It is evident that the presence of cationic species does not hinder the diffusion of cationic adrenaline [

32], even when exist a high possibility of electrostatic repulsion. This provides an idea of charge-hopping mediated by Ru-complex redox species. Electron transfer from adrenaline to the electrode seems to be particularly promoted by the Ru-complexes, which might be related to the delocalization of pi electrons from the ligands. As expected, this results indicate that the diffusion of adrenaline is slightly slower in the presence of the more voluminous [Ru(phen)

3]

2+ ion compared to [Ru(bpy)

3]

2+, but its motion inside the film is fast enough for the adrenaline charge transfer to be improved with respect to Naf-TMS. In

Table 1, are reported the potential differences between anodic and cathodic peaks (ΔE values) for all modified electrodes obtained from

Figure 5 and

Figure 8 at a scan rate of 100 mV s

-1. This provides the idea that the mechanism of diffusion through the film, involves hydrophobic as well as electrostatic interactions. It can be concluded that the electron transfer process of adrenaline electrooxidation is accelerated by Ru-complex modified Naf-TMS polymer, maintaining a Nerstian behaviour at several pH values.

4. Conclusions

The structural and ionic transport properties of Naf-TMS are similar to its relative more commercial and expensive Nafion® polymer. Currently, the availability of commercial solution of Nafion® polymer is limited or non-available from the usual suppliers, then Naf-TMS represents an excellent alternative strategy for applications in electrochemical sensors. Hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions play an important role in the ionic properties of Naf-TMS as evidenced from the way how it inserts different ions into its structure. The electrodes modified with Naf-TMS and Naf-TMS/Ru-complex exhibited high sensitivity for the detection of adrenaline. Due to a strong effect of pH in the redox reaction of adrenaline, there exists a wide possibility to tune and tailor the catalytic and analytical properties of polymer/Ru-complex composites by simply changing the pH. Ru-complexes accelerate the charge transfer redox reaction of adrenaline as demonstrated by a decrease in the difference between oxidation and reduction potential values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.S.; methodology, R.A.S. S.L.C.H. and D.A.D.T.; validation, S.L.C.H.; formal analysis, R.A.S. and D.A.D.T. investigation, R.A.S.; writing original—review and editing, R.A.S., S.L.C.H., J.L.G.M.; project administration, R.A.S., J.L.G.M;, funding acquisition, R.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge VIEP-BUAP for the financial support of the project 100467499-VIEP 2025. This work was funded by CONACyT-México through the projects 243030 and 104361.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

R.A.S. acknowledges CONAHCyT Mexico for the Research Fellowship “Estancia Sabática al Extranjero 2024-Reference 121841”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- N. Schweigert, A. J. B. Zehnder and R. I. L. Eggen. Chemical properties of catechols and their molecular modes of toxic action in cells, from microorganisms to mammals. Environ. Microbiol. 3, 2 (2001) 81-91. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Özel. A. Hayat and S. Andreescu. Recent developments in electrochemical sensors for the detection of neurotransmitters for applications in biomedicine. Anal. Lett. 48, 7 (2015) 1044–1069. [CrossRef]

- S. Madhurantakama, K. J.Babua, J. B. B. Rayappana, U. M. Krishnan. Nanotechnology-based electrochemical detection strategies for hypertension markers. Biosen. and Bioelectron. 116 (2018) 67–80. [CrossRef]

- V. S. Thirunavukkarasu, S. I. Kozhushkov and L. Ackermann. C–H nitrogenation and oxygenation by ruthenium catalysis. Chem. Commun. 50 (2014) 29-39. [CrossRef]

- Z. Feng, J. Zhou, Y. Xi, B. Lan, H. Guo, H. Chen, Q. Zhang and Z. Lin. Solid-state hybrid photovoltaic cells with a novel redox polymer and nanostructured inorganic semiconductors. J Power Sources 194, 2 (2009) 1142–1149. [CrossRef]

- M. Cai, Q. R. Loague, J. Zhu, S. Lin, P. M. Usov and A. J. Morris. Ruthenium(II)-polypyridyl doped zirconium (IV) metal–organic frameworks for solid-state electrochemiluminescence. Dalton Trans. 47, 46 (2018) 16807-16812. [CrossRef]

- S. Sheth, M. Li, Q. Song. New luminescent probe for the selective detection of dopamine based on in situ prepared Ru(II) complex-sodium dodecyl benzyl sulfonate assembly. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chemistry 371 (2019) 128–135. [CrossRef]

- Li Tian, X. Wang, K. Wu, Y. Hu, Y. Wang, J. Lu. Ultrasensitive electrochemiluminescence biosensor for dopamine based on ZnSe, graphene oxide@multi walled carbon nanotube and Ru(bpy)32+. Sensors and Actuators: B. Chemical. 286 (2019) 266–271. [CrossRef]

- Q. Gao, B. Song, Z. Ye, L. Yang, R. Liu and J. Yuan. A highly selective phosphorescence probe for histidine in living bodies. Dalton Trans. 44 (2015) 18671-18676. [CrossRef]

- E. Turkušić, S. Redžić, E. Kahrović, A. Zahirović. Electrochemical Determination of Adrenaline at Ru(III) Schiff Base Complex Modified Carbon Electrodes. Croat. Chem. Acta 90, 2 (2017) 345–352. [CrossRef]

- W. S. Ruifang, G. K. Jiao. Electrochemistry and Electrocatalysis of Hemoglobin in Nafion/nano-CaCO3 Film on a New Ionic Liquid BPPF6 Modified Carbon Paste Electrode. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 17 (2007) 4560–4567. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Toh, W. K. Peng, J. Han, M. Pumera. Direct In Vivo Electrochemical Detection of Haemoglobin in Red Blood Cells. Sci. Rep. 4 (2014) 6209. [CrossRef]

- K.A.Mauritz, J.T. Payne. [Perfluorosulfonate ionomer]/silicate hybrid membranes via base-catalyzed in situ sol–gel processes for tetraethylorthosilicate. J. Membrane Sci. 168, 1-2 (2000) 39-51. [CrossRef]

- S. Murata, R. Noyori Silylation with a perfluorinated resinsulfonic acid trimethylsilyl ester. Tetrahedron Lett. 21, 8 (1980) 767-768. [CrossRef]

- R. Aguilar-Sánchez, R.J. Díaz-Caballeros, J. A. Méndez-Bermúdez, J. L. Gárate-Morales, G. Domínguez-Meneses. Electrochemical studies of nafion–trimethylsilyl and nafion–trimethylsilyl/Ru complex-modified electrodes. J. Solid State Electrochem. 16 (2012) 2867–2876. [CrossRef]

- H.L. Yeager, A. Steck. Cation and water diffusion in Nafion ion-exchange membranes: Influence of polymer structure. J. Electrochem. Soc. 128 (1981) 1880–1884. [CrossRef]

- W. Y. Hsu and T. D. Gierke. Ion transport and clustering in nafion perfluorinated membranes. J. Membrane Science. 13, 3 (1983) 307-326. [CrossRef]

- Juris A, Balzani V, Barigelletti F, Campagna S, Belser P, Von Zelewsky A. Ru(II) polypyridine complexes: photophysics, photochemistry, eletrochemistry, and chemiluminescence. Coordin Chem Rev. 84 (1988) 85–277. [CrossRef]

- J.K. Barton, J.M. Goldberg, C.V. Kumar, N.J. Turro. Binding modes and base specificity of tris (phenanroline) ruthenium (II) enantiomers with nucleic acids: tuning the stereoselectivity. J Am Chem Soc 108, 8 (1986) 2081–2088. [CrossRef]

- E.H. Yonemoto, GB Saupe, RH Schmeh, SM Hubig, RL Riley, BL Iverson, TE Mallouk. Electron-Transfer Reactions of Ruthenium Trisbipyridyl-Viologen Donor-Acceptor Molecules: Comparison of the Distance Dependence of Electron Transfer-Rates in the Normal and Marcus Inverted Regions. J Am Chem Soc 116, 11 (1994) 4786–4795. [CrossRef]

- Y Jenkins, AE Friedman, NJ Turro, JK Barton. Characterization of dipyridophenazine complexes of ruthenium(II): The light switch effect as a function of nucleic acid sequence and conformation. Biochemistry 31, 44 (1992) 10809–10816. [CrossRef]

- R. Aguilar Sánchez, D.A. Durán Tlachino, S. L.Cabrera Hilerio, J.L. Gárate Morales, J.R. Cerna Cortez. Tend. Doc. Inv. Quim. 4 (2018) 421-425.

- L.G. De Pelichy, E.T. Smith, A study of the oxidation pathway of adrenaline by cyclic voltammetry: an undergraduate analytical chemistry laboratory exercise. The Chem. Educ. 2 (1997) 1–13. [CrossRef]

- C. Bretti, R. Maria Cigala, F. Crea, C. de Stefano, G. Vianelli. Solubility and modeling acid–base properties of adrenaline in NaCl aqueous solutions at different ionic strengths and temperatures. Eur. J. Pharmac. Sci. 78 (2015) 37-46. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Bard, L.R. Faulkner. Electrochemical Methods. Fundamentals and Applications. 2nd Ed. Wiley, New York. (1980) p. 218.

- F. Cui, X. Zhang. Electrochemical sensor for epinephrine based on a glassy carbon electrode modified with graphene/gold nanocomposites. J. Electroanal. Chem. 669 (2012) 35–41. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, M. Chen, X. Ma. Selective determination of epinephrine in the presence of ascorbic acid using a glassy carbon electrode modified with graphene. Anal. Sci. 28 (2012) 147–151. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, G. Wang, M. Liu, Y. Feng, Z. Zhang, B. Fang. Hydroxylamine electrochemical sensor based on electrodeposition of porous ZnO nanofilms onto carbon nanotubes films modified electrode. Electrochim. Acta 55, 8 2835–2840 (2010). [CrossRef]

- W. K. Adeniyi, A. R. Wright. Novel fluorimetric assay of trace analysis of epinephrine in human serum. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 74, 5 (2009) 1001–1004. [CrossRef]

- C. Bretti, F. Crea, C. De Stefano, S. Sammartano. Solubility and activity coefficients of 2,2-bipyridyl, 1,10-phenanthroline and 2,2´,6´,2´´-terpyridine in NaCl(aq) at different ionic strengths and T=298.15K. Fluid Phase Equilibria 272, 1-2 (2008) 47–52. [CrossRef]

- N. Holten-Andersen, M. J. Harrington, H. Birkedal, B. P. Lee, P. B. Messersmith, K. Yee C. Lee, and J. H.Waite. pH-induced metal-ligand cross-links inspired by mussel yield self-healing polymer networks with near-covalent elastic moduli. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 108, 7 (2011) 2651–2655. [CrossRef]

- R. Álvarez-Diduk and A. Galano. Adrenaline and Noradrenaline: Protectors against Oxidative Stress or Molecular Targets?. J. Phys. Chem. B 119 (2015) 3479−3491. [CrossRef]

Scheme 1.

Chemical structure of Naf-TMS polymer Error! Bookmark not defined., Error! Bookmark not defined..

Scheme 1.

Chemical structure of Naf-TMS polymer Error! Bookmark not defined., Error! Bookmark not defined..

Figure 1.

Representative height-mode atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of Naf-TMS a) at low and b) higher resolution. Line fit (color intensity) shows the vertical profile of the sample. The lightest region is the highest point.

Figure 1.

Representative height-mode atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of Naf-TMS a) at low and b) higher resolution. Line fit (color intensity) shows the vertical profile of the sample. The lightest region is the highest point.

Figure 2.

Series of visible absorption spectral change at different immersion times of Naf-TMS membranes in 1 mM of A) [Ru(bpy)3]2+ and B) [Ru(phen)3]2+ complexes. Insets show the dependence of absorbance with immersion times.

Figure 2.

Series of visible absorption spectral change at different immersion times of Naf-TMS membranes in 1 mM of A) [Ru(bpy)3]2+ and B) [Ru(phen)3]2+ complexes. Insets show the dependence of absorbance with immersion times.

Figure 3.

Differential pulse response obtained at several concentrations (1×10-6 to 2×10-5 mol L-1) of adrenaline recorded in 0.1 M H2SO4 at a GC/Naf-TMS modified electrode. Scan rate 20 mV s-1; pulse amplitude, 50 mV; pulse duration, 200 ms. Inset: linear dependence of peak current on AD concentration.

Figure 3.

Differential pulse response obtained at several concentrations (1×10-6 to 2×10-5 mol L-1) of adrenaline recorded in 0.1 M H2SO4 at a GC/Naf-TMS modified electrode. Scan rate 20 mV s-1; pulse amplitude, 50 mV; pulse duration, 200 ms. Inset: linear dependence of peak current on AD concentration.

Scheme 2.

Electrooxidation reaction of adrenaline.

Scheme 2.

Electrooxidation reaction of adrenaline.

Figure 4.

Differential pulse voltammograms recorded at 2×10-5 mol L-1 adrenaline at several pH values (indicated in figure), using a modified GC/Naf-TMS modified electrode. Scan rate, 20 mV s-1; pulse amplitude, 50 mV; pulse duration, 200 ms. Inset: Dependence of the anodic peak potential versus pH of the electrolyte.

Figure 4.

Differential pulse voltammograms recorded at 2×10-5 mol L-1 adrenaline at several pH values (indicated in figure), using a modified GC/Naf-TMS modified electrode. Scan rate, 20 mV s-1; pulse amplitude, 50 mV; pulse duration, 200 ms. Inset: Dependence of the anodic peak potential versus pH of the electrolyte.

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltammograms of the scan rate dependence versus current, recorded for 2×10-4 mol L-1 adrenaline a GC/Naf-TMS electrodes in 0.1 M H2SO4. Inset: Linear dependence.

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltammograms of the scan rate dependence versus current, recorded for 2×10-4 mol L-1 adrenaline a GC/Naf-TMS electrodes in 0.1 M H2SO4. Inset: Linear dependence.

Figure 6.

Differential pulse voltammograms recorded at 2×10-5 M adrenaline at several pH values ranging from 1 to 9, using GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(bpy)3]2+ and GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(phen)3]2+ modified electrodes. Scan rate, 20 mV s-1; pulse amplitude, 50 mV; pulse duration, 200 ms. Insets: Dependence of the anodic peak potential versus pH of the electrolyte.

Figure 6.

Differential pulse voltammograms recorded at 2×10-5 M adrenaline at several pH values ranging from 1 to 9, using GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(bpy)3]2+ and GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(phen)3]2+ modified electrodes. Scan rate, 20 mV s-1; pulse amplitude, 50 mV; pulse duration, 200 ms. Insets: Dependence of the anodic peak potential versus pH of the electrolyte.

Figure 7.

Differential pulse voltammograms at several concentrations of adrenaline ranging from 2×10-6 to 1×10-4 M using A) GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(bpy)3]2+ and B) GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(phen)3]2+ modified electrodes in 0.1 M H2SO4. Inset: Linear response of current versus adrenaline concentration.

Figure 7.

Differential pulse voltammograms at several concentrations of adrenaline ranging from 2×10-6 to 1×10-4 M using A) GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(bpy)3]2+ and B) GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(phen)3]2+ modified electrodes in 0.1 M H2SO4. Inset: Linear response of current versus adrenaline concentration.

Figure 8.

Cyclic voltammograms at several scan rates (10 to 500 mV s-1) in presence of 2×10-4 M AD, using a) GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(bpy)3]2+ and b) GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(phen)3]2+ modified electrodes in 0.1 M H2SO4. Inset: Linear dependence of current versus square root of scan rate.

Figure 8.

Cyclic voltammograms at several scan rates (10 to 500 mV s-1) in presence of 2×10-4 M AD, using a) GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(bpy)3]2+ and b) GC/Naf-TMS/[Ru(phen)3]2+ modified electrodes in 0.1 M H2SO4. Inset: Linear dependence of current versus square root of scan rate.

Table 1.

Analytical parameters obtained from differential pulse and cyclic voltammetry for Naf-TMS and Naf-TMS/Ru-complex modified glassy carbon electrodes in presence of adrenaline in 0.1 M H2SO4.

Table 1.

Analytical parameters obtained from differential pulse and cyclic voltammetry for Naf-TMS and Naf-TMS/Ru-complex modified glassy carbon electrodes in presence of adrenaline in 0.1 M H2SO4.

| Electrode modifier |

[AD]

10-6 M |

Sensitivity

µA/µM |

Detection Limit

µM |

ΔEa

mV |

D

cm2 s-1

|

| Naf-TMS |

1 – 20 |

0.57±0.02 |

0.52±0.02 |

312±8 |

(7.9±0.5)×10-5

|

| Naf-TMS/[Ru(bpy)3]2+

|

1 – 100 |

0.51±0.01 |

0.58±0.04 |

178±5 |

(4.6±0.4)×10-5

|

| Naf-TMS/[Ru(phen)3]2+

|

1 – 100 |

0.45±0.01 |

0.68±0.05 |

225±5 |

(5.1±0.4)×10-5

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).