1. Introduction

The ubiquitous cellular protein cofilin attracted the interest of researchers almost 50 years ago [

1]. Since then, several cofilin homologues were identified. ADF/cofilins are a family of small, widely expressed actin-binding proteins, regulating actin dynamics in various cellular and physiological processes in all eukaryotes from yeasts to animals [

2,

3,

4,

5]. More precisely, cofilin depolymerizes filamentous actin (F-actin) producing monomeric, globular actin (G-actin). Mammals express all three members of the ADF/cofilin family: cofilin-1, cofilin-2, and ADF (actin depolymerizing factor, also called destrin) [

2]. Non-muscle cells and tissues mostly express both cofilin-1 and ADF, but their expression level may vary. Certain cell types express all three ADF/cofilins [

6,

7]. Cofilin-2 is found primarily in muscle [

8], but also in brain and liver [

9], oligodendrocytes and keratinocytes [

6,

7]. While the three ADF/cofilin proteins share some overlapping functions, each of them also performs unique functions in vivo. GWAS data analysis performed separately for cofilin-1, cofilin-2 and destrin, shows that all three proteins are associated with completely different phenotypes [

10]. Cofilin-1 deficient mice display early embryonic lethality and defects in actin-dependent morphogenic processes [

11]. Such mutants are also lethal in yeast. ADF inactivation leads to corneal defects [

11,

12]. Although ADF and cofilin-1 share 70% of sequence identity and share overlapping functions, cofilin-1 is the major non-muscle isoform of ADF/cofilin in various cell types [

6].

Cofilin-1 expression is regulated by microRNAs (miRNAs) as recently reviewed [

13]. MiR-342 targets cofilin in human breast cancer cells, miR-429 targets cofilin in colon cancer cells; miR-182-5p binds to cofilin mRNA in human bladder cancer cells. miR-134 was reported to suppress translation of cofilin [

14]. Other miRNAs, such as miR-138 and miR-384, modulate the activity and expression of cofilin in ovarian cancer [

15] and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by targeting LIMK1 kinase [

16]. All these miRNAs act as inhibitors of cofilin activity either by directly targeting cofilin or its upstream effector, LIMK1 kinase.

In the molecular structure of cofilin, two actin-binding sites are present. One site binds both monomeric (G) and filamentous (F) actin, the second site interacts only with F-actin. Binding of cofilin to the actin filament causes a change in the orientation of actin subunits, which results in actin filament severing [

17].

Changes in the expression of the ADF/cofilin family proteins have been demonstrated under various pathological conditions. Mutations in the cofilin-2 gene can cause a variety of pathologies in different organisms. In humans, it was shown to cause myopathies [

18]. In mice, its deficiency causes disruptive accumulation of F-actin in skeletal muscles [

4], and abnormalities of the sarcomeric architecture. The cofilin-1 gene is overexpressed in metabolic syndrome in humans [

19] and may be involved in neurodegeneration as was demonstrated in Aplysia [

20]. Cofilin activity was found to be changed in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases, spinal muscular atrophy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, prion diseases, and deletion-duplication syndromes [

21]. The mRNA levels and expression of cofilin-1 was higher in most tumor tissues as compared to normal in various types of cancer, such as non-small cell lung cancer, prostate cancer, vulvar squamous cell carcinoma, hepatoblastoma, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and bladder cancer [

22,

23,

24]. At the same time, an increased methylation level of the cofilin-1 promoter regions was present in colon and rectal adenocarcinoma tissues, according to the TCGA database [

25]. The overexpression of cofilin was shown to be correlated with proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and poor survival. However, tumor size, pathological stage and patient age were not found to be associated with the expression level of cofilin [

22,

26]. Downregulation of the cofilin-1 gene expression increases the percentage of apoptotic cells in the T24 and RT4 bladder cancer cell lines [

24]. The established role for cofilin in migration, invasion, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, apoptosis, radiotherapy and chemotherapy resistance, immune escape, and transcriptional dysregulation of malignant tumors [

13], is explained mainly by the cofilin-controlled mechanic activity of cells, like proliferation, cell migration, cell adhesion, and colony formation. As such, the cofilin gene might become a novel target in the strategy of diagnosis and even treatment of cancer, which warrants a careful study of all aspects of cofilin activity. For example, the involvement of cofilin-1/TEAD1/p27Kip1 signaling in senescence-related morphological change and growth arrest was recently described [

27].

Details of derailed cofilin signaling, leading to actin filament severing, depolymerization, nucleation, and bundling are currently under active investigation. The initial understanding that cofilin depolymerizes actin fibers has now undergone refinement. At low cofilin:actin ratios, cofilin severs F-actin and increases the ADP-actin monomer dissociation rate. At high cofilin:actin ratios, cofilin stabilizes F-actin where all the subunits have undergone cofilin-induced rotation. Cofilin exerts its highest actin severing activity when the cofilin:actin ratio is around 1:800 [

28]. Cofilin can also induce nucleation of actin. Inactive, phosphorylated cofilin (p-cofilin) does not significantly bind to F-actin, and its actin severing or depolymerization activity is low [

29].

Interestingly, although elevated cofilin expression is generally associated with increased cell motility, glioblastoma cells overproducing cofilin have decreased motility as compared to cells producing a moderate amount of cofilin [

30]. The ADF/cofilin complex is accumulated in confluent cells, and this causes G1 phase arrest in the cell cycle progression in a variety of cell lines [

31]. This may be because cofilin under some conditions is involved not only in actin filament reorganization but also in other functions.

2. Post-Translational Modifications of Cofilin

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) play important roles in regulating cofilin-1 function by allowing local control for enhanced versatility. Thus, the same ubiquitous cytoplasmic protein cofilin is involved in a multitude of cellular processes, sensing local pH, oxidative stress, etc. Cofilin activities are spatiotemporally orchestrated by numerous extra- and intra-cellular factors. The multitude of PTMs of cofilin such as phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, S-nitrosylation [

32], ISG15-ylation, etc. and their combinations [

29], in addition to the various expression levels of cofilin, is probably what allows this protein to transmit diverse signals to the cellular environment in very precise ways. Phosphorylation is a major type of PTMs. It regulates a variety of cellular signaling pathways in control of cell growth, division, differentiation, motility, and cell death [

33].

It should be mentioned that PTMs generate opportunities for cross-regulation. Interdependent PTMs can occur on different remote amino acids, for example, between phosphorylation, residing on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues, and ubiquitination, residing on lysine residues [

34]. This relation is known to occur widely in various biological processes, for example cellular events following epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulation, where strong correlations between ubiquitinated and phosphorylated modifications have been observed [

35]. Bioinformatic analyses have also demonstrated widespread functional connections/dependencies between several PTM groups [

36].

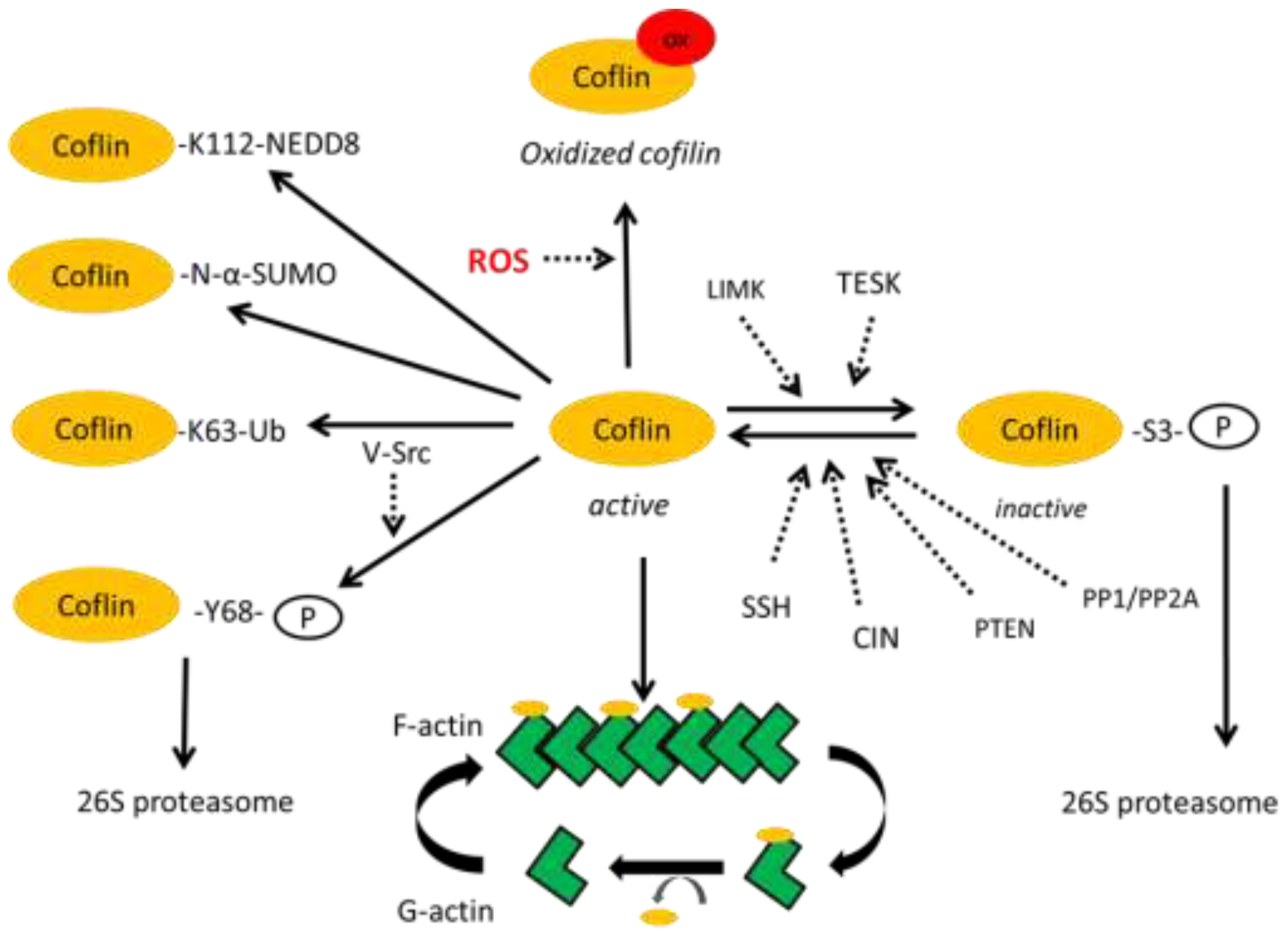

The best studied PTM of cofilin is its phosphorylation leading to its degradation as the main outcome. Cofilin is phosphorylated at the S3 position by the LIM and TES kinases. They can indirectly control F-actin stability through changing the level of cofilin phosphorylation, thereby decreasing the stability of active cofilin, as their overexpression in cells led to F-actin accumulation [

37,

38]. Chronophin (CIN) and Slingshot (SSH) are specific cofilin phosphatases that dephosphorylate cofilin at the S3 position, thus protecting it from degradation [

39]. The more generic serine/threonine phosphatases type 1 (PP1) and type 2A (PP2A) have also been reported to dephosphorylate cofilin [

40]. Moreover, it was established that phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) can directly dephosphorylate and activate cofilin-1, leading to depolymerization of F-actin [

41] (

Figure 1).

Additionally, cofilin is phosphorylated at T63, Y82 and S108 [

42]. Phosphorylation of Y68 and Y140 has also been demonstrated [

43]. Phosphorylation at Y68 triggers degradation of cofilin via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and consequently counteracts the cellular functions of cofilin in reducing cellular F-actin contents and cell spreading.

Like other cellular molecules which participate in inactivation of reactive oxygen species (glutathione, lipoic acid, thioredoxin), cofilin contains several thiol (SH) groups which, under conditions of oxidative stress, mediate oxidation of cysteine residues leading to the appearance of cofilin dimers due to formation of disulfide bridges, which can cross-link actin filaments. Stable actin-cofilin rods save cellular ATP, which is not used during the active polymerization process. This facilitates faster cell recovery from stress. The intermolecular disulfide bonds mediate dimers, trimers and oligomers of cofilin [

44].

Ubiquitin modifications of cofilin are not fully understood, especially in terms of specifying which specific lysine in cofilin can covalently bind ubiquitin molecules in specific cells, under specific conditions. Recently, a lysine-less mutant cofilin-1

25KR was created where all lysine were mutated [

45].

It was shown that K112 of cofilin binds NEDD8, a ubiquitin like molecule [

46]. The putative sites of cofilin ubiquitination have been suggested as K45,53,144,164 [

47]. Obviously, the proximity of the ubiquitination and phosphorylation sites suggests that modification may take place competitively. However, to resolve this question, a 3D structure will be required.

Thus, modifications of cofilin, especially, the ubiquitination and the sequential, coupled modifications (for example, phosphorylation and ubiquitination and vice versa), still await further exploration at the molecular level to gain insights in the dynamic regulation of cofilin activity.

Many post-translational modifications of cofilin are discussed considering the premise of such modification for its sequential phosphorylation at the S3 position to generate inactive phospho-cofilin, for recognition by the proteasome system to undergo degradation.

The significance of PTMs of cofilin unrelated to its degradation still awaits further exploration. The K63 ubiquitin-branched modification of cofilin is one such post-translational modification, probably mediated by the AIP4 ubiquitin ligase [

48]. The K63 ubiquitinated proteins usually mediate the formation of inducible protein complexes that convey a variety of signals depending on the protein composition in the complexes [

49,

50,

51].

The use of mass spectrometry-based proteomics has greatly accelerated the discovery of new PTMs and their sites of action on various proteins [

52]. The most recent cofilin-1 modification reported describes N-terminal α-amino SUMOylation of cofilin-1, which is critical for its regulation of actin depolymerization [

45].

However, cofilin-mediated actin dynamics can drive motility without post-translational regulation [

3,

45].

3. The Mitochondrial Localization of Cofilin

The localization of cofilin in mitochondria was reported several years ago, when its increased expression was noticed in connection with the Warburg effect in tumor cells [

53]. In the following years many papers have documented the translocation of cofilin to mitochondria upon treatments that initiate apoptotic or necrotic cell death, as recently reviewed [

3].

Moreover, regions in cofilin were identified, which are critical for mitochondrial localization (in mammalian cells, specific amino acids at position 15–30 at the N-terminus and on position 106–166 at the C-terminus), which suggests that cofilin-1 indeed can bind to mitochondria directly [

54]. It is therefore perplexing that cofilin still is not included in the Inventory of Mammalian Mitochondrial Proteins [

55].

Since then, the functional consequences of cofilin involvement in mitochondrial dysfunction have become a focus of active studies as cofilin affects many aspects of mitochondrial homeostasis. Cofilin found in the mitochondrial fraction of cells, was characterized as unphosphorylated [

54], oxidized [

54,

56], or modified with the K63 branched ubiquitin chains [

57]. In general, cofilin expression in pathological conditions has been associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, mediating cell death or cell division.

Most of the published data up to now on the association of cofilin with mitochondria attribute the cofilin-mediated effect on mitochondria and, in general, on cells, mainly, to actin reorganization. Cofilin controls mitochondrial traffic along the microtubules and actin [

3]. Cofilin regulates mitochondrial morphology and function via redistribution of phospho-cofilin, cofilin, and its ubiquitinated proteoforms between the cytoplasm and mitochondria. This has been shown to correlate with changes in tissue respiration activity and mitophagy in mouse brain nerve cells [

57].

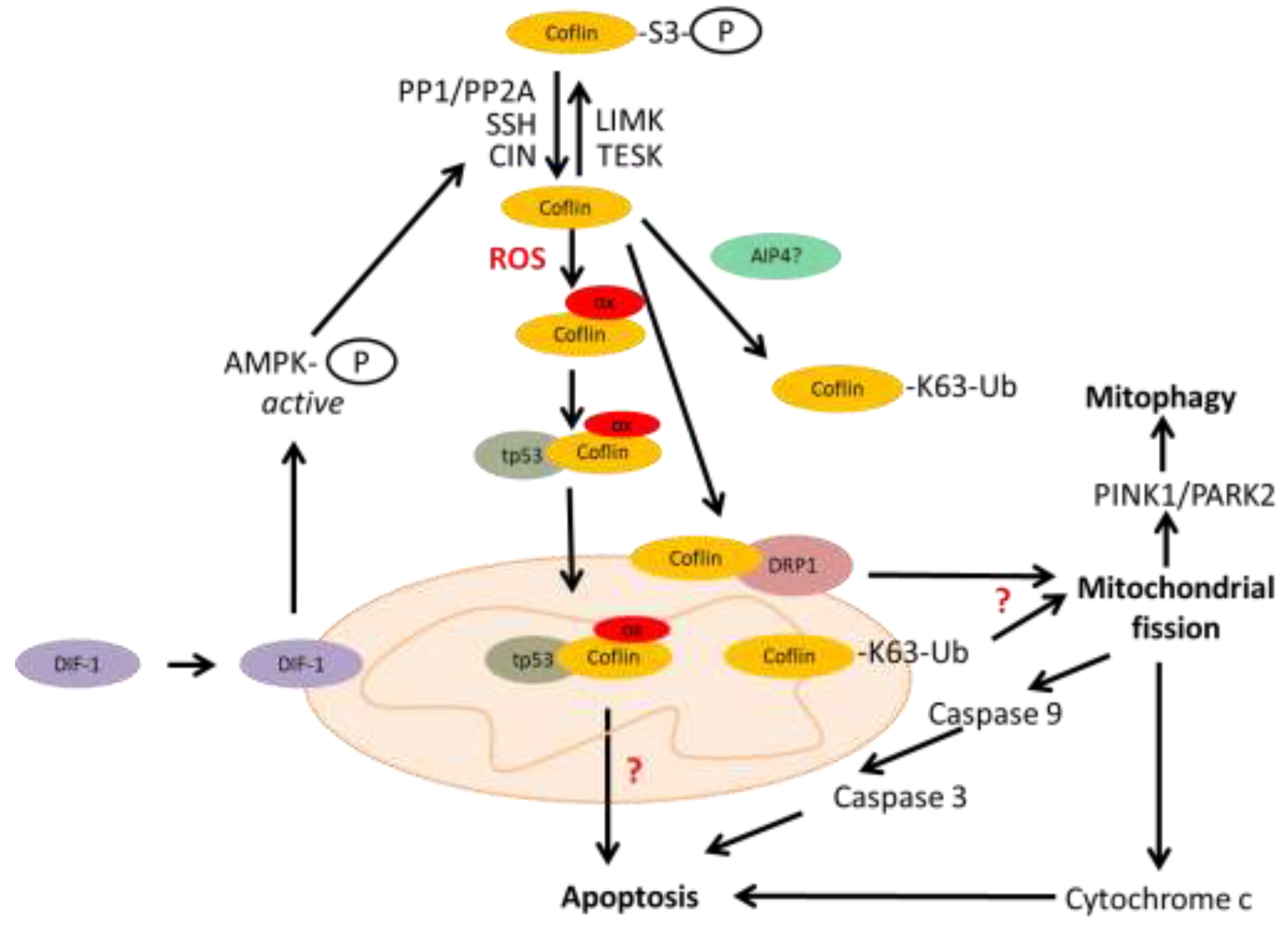

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles, and permanent fission and fusion is essential to maintain their function in energy metabolism, calcium homeostasis, regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and apoptosis. Under oxidative stress, active and oxidized cofilin can be translocated into the mitochondria [

58]. By regulating the actin cytoskeleton, cofilin induces mitochondrial fission, the first step in mitophagy. The molecular mechanism of cofilin-induced mitochondrial fission is being elucidated. First of all, cofilin itself is recruited to mitochondria in the mitochondrial fission process [

17,

59,

60,

61]. Cofilin recruits to mitochondria the dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), a key factor in the mitochondrial fission machinery [

62]. Cofilin is activated in this process by differentiation-inducing factor 1 (DIF-1) as it activates pyridoxal phosphatase (or CIN) via AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). Cofilin could be activated by two other phosphatases, by PP1/PP2A via Src-Akt-mTOR and PTEN-PI3K pathways, and by SSH. Cofilin knockdown inhibits mitochondrial fission and decreases mitofusin 2 (MFN2) protein levels, a crucial factor required for mitophagy [

63]. Cofilin potentiates mitochondrial fission as well as PINK1/ PARK2-dependent mitophagy [

60]. Mitochondrial fission may activate the release of cytochrome c, and caspase-9 resulting in apoptosis. Moreover, cofilin-1 was shown to participate directly in the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and releasing cytochrome с, and to apoptosis progression, independently of its role in mitochondrial dynamics [

64]. Apoptosis can also be initiated by the cofilin/p53 pathway (

Figure 2).

Thus, it has now become clear that cofilin in addition to its actin depolymerizing activity, also affects several metabolic functions. Interestingly, in response to environmental challenges, cofilin uses its actin filament disassembly activity and mitochondrial activity independently of each other [

65]. Cofilin localizes on the mitochondria and enters the mitochondria. The functional consequences of these processes are under active investigation now. One of the most speculative issues discussed currently is how actin enters into mitochondria and the role it plays there [

3]. Cofilin may serve to deliver G-actin into mitochondria.

4. Cofilin Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction During Neurodegeneration

Effects of deregulated cofilin activity on mitochondria were reported in neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease (AD) [

20], and were characterized by neuronal degeneration and death, as well as by distorted synapse formation, oxidative stress etc. [

6,

29,

58,

59].

This deregulated cofilin activity mainly resulted in the generation of abnormal cytoplasmic structures. In neurons, these structures caused abnormal distribution of cellular organelles, such as mitochondria or early endosomes, loss of pre- and postsynaptic compartments and, therefore, reduced synaptic transmission and impaired neuronal plasticity [

66]. A complex relationship between mitochondrial function (ATP synthesis, ROS level, autophagy) and cofilin ubiquitination was shown in the nerve cells [

67].

In Parkinson’s disease (PD) cofilin-1 binds to α-synuclein and promotes its aggregation. These aggregates are observed at the onset and progression of PD. Cofilin facilitates the prion-like transmission of α-synuclein fibrils into neurons [

68]. Apart from general distortion of cytoskeletal organization by these aggregates, these structures cause mitochondrial dysfunction [

69].

In Alzheimer’s disease, which is characterized by proteinopathies like rod shaped actin bundles (rods), amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide and hyperphosphorylated tau, cofilin translocates to mitochondria promoting neurotoxicity. Activated cofilin (not phosphorylated at the S3 position) acts as a bridge between actin and microtubule dynamics by displacing tau from microtubules, thereby destabilizing tau-induced microtubule assembly, missorting tau, and promoting tauopathy [

70]. K63-dependent ubiquitination of cofilin was suggested to influence the level of cofilin, autophagy activation, actin dynamics and bundle organization in the nerve cells. K63 ubiquitin decorated cofilin was shown to activate autophagy, actin dynamics and bundle organization in the mouse nerve cells, an activity not coupled to its degradation [

57].

Under AD pathological conditions, cellular ROS leads to oxidation of cysteine residues of cofilin at positions 39, 80, 139 and 147 and of the methionine residue at position 115. At the same time, four cysteines at these positions are important sites in cofilin for oxidation-mediated regulation of mitochondrial translocation [

64]. Under these circumstances and concomitant with dephosphorylation of S3, cofilin is prone to form cofilin-actin rods. ATP depletion is a major trigger for cofilin-actin rod formation at a stoichiometric proportion of 1:1 [

71].

Cofilin-actin rods have also been suggested to possess protective properties under stress conditions [

72]. They may protect against loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential and decline of cellular ATP level. Through rod formation, actin dynamics is alleviated, and energy can be used for other processes enhancing the cellular resilience during stress exposure [

73]. At later stages of the stress response, however, disrupted actin dynamics may counteract this positive energy-saving effect.

Mitochondrial translocation of cofilin was also observed in paradigms of apoptosis, as cofilin colocalization with mitochondria and subsequent induction of cytochrome c release was an early step in the cell death cascade [

54,

74]. It is the oxidized cofilin that is recruited to mitochondria in this case. The mechanism of cell death is described as oxidative cell death, more precisely, oxytosis and ferroptosis, at least in neurons [

59]. ROS overproduction is induced by the formation of Aβ plaques, which is promoted by the scaffolding protein RanBP9. This protein also delays clearance of cytosolic Ca

2+ in a process involving the translocation of cofilin into mitochondria and oxidative mechanisms. This leads to neurodegenerative changes reminiscent of those seen in AD. RanBP9, cofilin, and Aβ mimic and potentiate each other in AD pathology [

61].

The molecular mechanisms of cofilin-mediated distortion of mitochondrial function are beginning to unravel further. In neurons, cofilin depletion can enhance Drp1 accumulation at mitochondria [

62], cofilin-Drp1 interaction at the mitochondrial membrane and mitochondrial division [

75]. Thus, maturation and activation of Drp1 oligomers at the mitochondrial surface, induced by cofilin depletion, increased mitochondrial fragmentation without deteriorating mitochondrial function in mouse embryonic fibroblasts [

76]. Dephosphorylation at S3 led to mitochondrial transactivation of cofilin and an interplay with Drp1 to enhance fragmentation of the organelle [

62]. In yeast, it was demonstrated that cofilin mutants, deficient in actin binding, can enhance mitochondrial respiration, indicating that cofilin may also exert actin-independent effects on mitochondrial function [

65].

5. Cofilin Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction During Tumorigenesis

ADF/cofilin family members are expressed at elevated levels in most tumor tissues and are thus regarded as oncogenes [

13,

77,

78,

79], comprehensively reviewed as such recently [

13]. Elevated levels of dephosphorylated cofilin were detected in different cancers.

The best studied mechanisms of cofilin involvement in tumorigenic processes are the cofilin-controlled turnover of cell surface receptors leading to the increased oncogenic signaling, like EGFR, and the cofilin controlled actin turnover leading to the increased migration of tumor cells. It was demonstrated that in cofilin-knockout cells, the cell cycle was arrested in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, lamellipodia formation was impaired, and invasion and metastasis were reduced [

80]. Another study found that the serum levels of cofilin immune complexes were significantly higher in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients than in healthy controls [

81].

Cofilin localization at the mitochondria deserves more detailed investigation, especially its involvement in interaction with lipid droplets. It is dephosphorylated [

54] and oxidized cofilin that can translocate to the mitochondria and participate in the regulation of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. C39, C80, C139 and C147 are the four important sites of cofilin for oxidation-mediated regulation of mitochondrial translocation [

64] and for its participation in the regulation of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis [

82].

Mitochondrial homeostasis is one of the areas of focus in the development of cofilin-targeted drugs to target cancer cells and induce tumor cell apoptosis. Mitochondrial processes targeted by drugs include reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial fission and mitochondrial autophagy processes.

The factors controlling cofilin and Drp1 activities, being the main mediators of these processes, are in the focus for the development of anti-cancer drugs. As PTEN/PI3K [

21] and Src/Akt/mTOR [

83] signaling pathways control PP1/PP2A phosphatases that act upon cofilin [

84], inhibitors of PI3K and Akt activities are used to inactivate cofilin. As a result, dephosphorylated cofilin translocates to the outer membrane of the mitochondria where it binds directly to F-actin, depolymerizes it producing G-actin. The G-actin bound to cofilin enters the mitochondria and causes cytochrome c leakage into the cytoplasm [

62]. This leads to activation of apoptosis inducing proteases, starting from caspase 9 [

85].

The interaction of Drp1 and cofilin is a target for drug development, as it mediates mitochondrial fission. Drugs have been developed to target the PINK1/Park2 pathway, which regulates the Drp1 phosphorylation and the GDP/GTP status of this GTPase [

86]. The PINK1/Park2 pathway is the key pathway that regulates mitochondrial autophagy [

87]. As cofilin is involved in mitochondrial autophagy induction [

88], drugs affecting the PINK1/Park2 pathway are investigated with the prospect to suppress mitophagy in tumor cells.

6. Cofilin and Lipid Metabolism

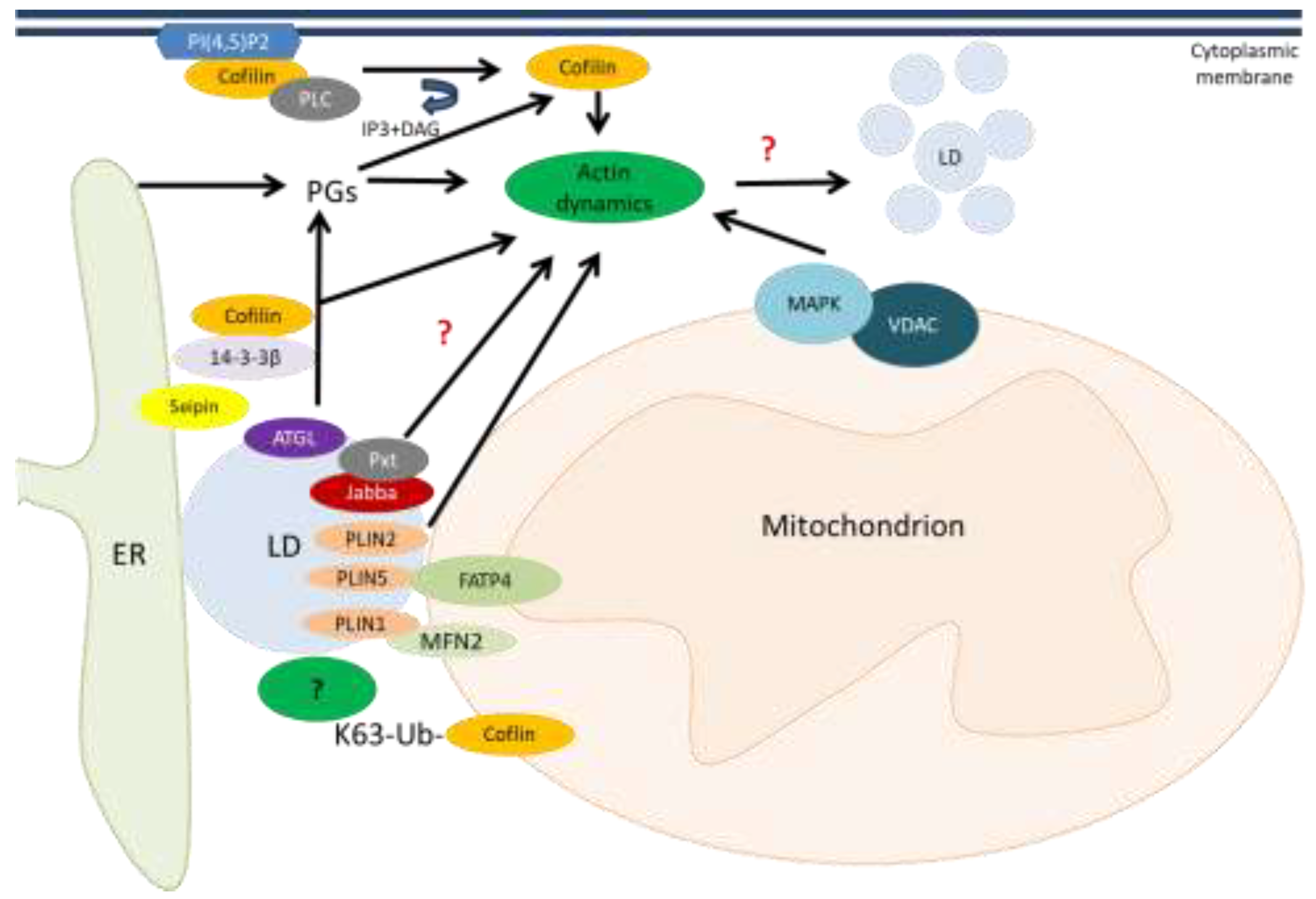

Cofilin, in addition to affecting the morphology and movement of mitochondria, can affect their interorganelle interactions. One of these is the interaction of mitochondria with lipid droplets (LDs) which has currently gained attention [

89] and our preliminary data suggest. In general, evidence is accumulating about the involvement of cofilin in lipid metabolism. As has been shown in yeast, cofilin-regulated actin dynamics lead to disruption of lipid homeostasis, accumulation of LDs, and development of necrosis along with disruption of cell wall integrity and vacuole fragmentation. Briefly, cofilin activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase Slt complex with a voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) located in the mitochondrial outer membrane, which in yeast is called Porin 1. This also provides evidence for a link between actin regulation and mitochondrial signaling [

90] (

Figure 3).

The members of the perilipin (PLIN) family PLIN1 and PLIN5 were shown to be involved in mitochondria-LD interactions. MFN2 specifically interacts with PLIN1 to form a protein complex tethering mitochondria to LDs. The acyl-CoA synthetase, FATP4 (ACSVL4) was identified as a novel mitochondrial interactor of PLIN5 for channelling fatty acids from LDs to mitochondria and subsequent oxidation [

91,

92]. The LD protein perilipin PLIN2 was shown to regulate actin remodeling by a prostaglandin (PG)-independent pathway. Other LD proteins Jabba and Pxt act together and modulate actin dynamics (by an unknown mechanism), adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) liberates arachidonic acid from triacylglycerols (TAGs) stored in LDs, providing the substrate for Pxt and prostaglandin production [

93]. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) was identified as an inhibitor of actin polymerization by activation of cofilin-1. This process is mediated by the protein phosphatase activity of PTEN [

94].

Scaffolding protein 14-3-3β was identified to serve as a link between endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident protein seipin which mediates lipid storage signals during adipogenesis and cofilin-1-mediated cytoskeleton remodeling [

95].

In addition, membrane-bound dephosphorylated cofilin can be activated through the cleavage of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P

2) by phospholipase C (PLC). As a result, active cofilin alters actin remodeling in the cytoplasm [

96]. There is an intriguing possibility that ubiquitinated cofilin K63 may also affect lipid droplet levels by mediating their contacts with mitochondria through an as yet unknown cellular factor that ensures fatty acid entry into mitochondria [

97]. In general, cofilin-1 depletion was reported to disrupt adipogenesis and lipid storage by inhibiting actin dynamics [

98].

The involvement of lipid metabolism in tumor progression has been noted before and has been recently reviewed [

99,

100]. Moreover, the view that altered metabolism may be a driving force behind tumor initiation has now gained acceptance [

100]. The tumor promoting role of altered lipid metabolism in cancers is now widely accepted as a favored means by which cancer cells may obtain energy, components for membranes, and a means of hijacking signaling molecules needed for proliferation, survival, invasion and metastasis, all of which may determine the response to cancer therapy.

Disturbed lipid metabolism in tumor cells is often characterized by the accumulation of lipid droplets. Lipid droplets are now recognized as cellular organelles and are the subject of current studies [

101]. However, the functions of lipid droplets in cellular homeostasis and inflammatory signaling are far from being clear and require further research. This field of research is rapidly expanding and was already summarized in the reviews the last years [

102,

103,

104].

The presence and function of LDs in the central nervous system has recently gained attention, especially in the context of neurodegeneration. LDs are promising targets for novel investigations of neurological disease diagnosis and therapeutics. Further study on LDs and lipid metabolism will be essential in advancing the knowledge of cerebral metabolism, as well as the multifaceted etiologies of neurological disease. Therapeutic treatments could be targeted at restoring lipid balance, decreasing droplet levels, or improving other aspects of lipid metabolic pathways [

105,

106].

The dynamic contacts that tether lipid droplets to mitochondria are mediated through protein complexes, the identification of which is in urgent demand [

89]. LDs not only bind organelles in a dynamic mode but also actively move [

98] along actin networks and microtubules, apparently requiring the cofilin activity. This movement also requires tight regulation to be functional. The loss of proper contacts between mitochondria and lipid droplets is directly involved in tumorigenesis [

101].

How contacts between lipid droplet and mitochondria affect the inflammatory response is an open question. Data obtained so far suggests that lipid droplets, as cell organelles and sources of lipid derivatives, can play opposite roles in inflammation, either promoting it or protecting against it, depending on cell type, cellular context etc. [

102,

103]. Thus, it is a promising direction to study the involvement of cofilin in lipid metabolism and inflammatory processes.

The ubiquitous expression of cofilin and its involvement in many signaling pathways are reasons that viruses have highjacked cofilin signaling [

48,

107,

108].

Deregulated expression and functions of cofilins are currently best studied in neurodegenerative pathologies and during tumorigenesis. However, a role of cofilin in metabolic disorders is now beginning to emerge, which is not surprising considering the control exercised by cofilin over mitochondrial traffic, mitochondrial division (fission), and mitochondrial membrane permeabilization.

Despite a great deal of knowledge about the functions of cofilin, some of its mechanisms of action remain a mystery and require further study. In this regard, it is relevant to elucidate the underlying mechanism of cofilin binding to mitochondria, and how cofilin may control contacts between mitochondria and other organelles.

5. Conclusions

Cofilin has emerged as a biomarker which is often targeted in different pathological conditions. Specifically, its functional involvement in mitochondrial fission makes it interesting to investigate in connection with wound healing processes, as it requires mitochondrial activity, initiated by the fission processes.

All this motivates to focus on the involvement of cofilin in metabolic processes occurring in different pathologies.

To elucidate the mechanics of altered metabolism in various pathologies, the proteome of the lipid droplet-mitochondria complex and, particularly, cofilin modified with K63 ubiquitin elongated chains deserves careful investigation in light of the proposed molecular mechanism linking lipid droplets and mitochondria [

109]. An even more important task would be to reveal the dynamics of cofilin-mediated changes in mitochondrial metabolism.

The elucidation of inducible protein complexes on the mitochondrial membrane, at the interface between mitochondria and lipid droplets, and other preconditions for the formation of such complexes, can help create new drugs against malignant tumors. For example, our unpublished results suggest that the K63 ubiquitinated cofilin may serve as an adaptor in an inducible protein complex linking lipid droplets and mitochondria, leading to the disappearance of lipid droplets and hence normalization of lipid metabolism.

The functional effects of inducible cofilin translocations from the cytoplasm are gaining attention. It is now known that translocation of cofilin into mitochondria leads to a decrease in membrane potential [

85], and if into the nucleus, it may affect DNA repair [

110], and if to the cell surface, it may function as an autoantigen [

111]. Thus, the role of cofilin in mediating mitochondrial contacts with lipid droplets deserves further investigation.

Deciphering how cofilin may control mitochondrial functions may reveal mechanisms, that will help protect cells from unwanted signal rearrangement and metabolic changes and substantiate metabolically induced restoration of mitochondrial functions, i.e., through nutritional manipulation, used as an anti-cancer treatment.

The numerous controversies surrounding the involvement of cofilin in pathological processes have yet to be resolved. For example, cofilin is overexpressed in malignancies, but still, induction of cofilin activities and/or its increased expression is suggested as a treatment of cancers or a means to inhibit migration of tumor cells [

112]. However, cofilin expression in malignant tissues has also been reported as decreased [

25]. Cells are arrested in G1 phase both when cofilin is knocked out and when its levels are elevated in confluent cells. These discrepancies may arise, possibly, due to yet unknown mechanisms of cofilin expression regulation and/or use of different cell lines in the studies.

Recent advances in experimental techniques (mass spectrometry, microscopy, bioinformatics analysis) will certainly help to delineate the pleiotropic actions of cofilin, aid in identifying new post-translational modifications of cofilin and further elucidate the role of known ones in the dynamic regulation of cellular homeostasis under stress. It will help to discover other proteins mediating mitochondria-lipid droplet contacts in addition to the very few, known currently.

Drugs, peptides or other substances targeting the critical amino acid residues of cofilin, which are in control of the interactions between mitochondria and lipid droplets might offer new potential therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative disorders and tumors.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, L.M., T.K.; writing—review and editing, L.M., T.K., M.G.; editing the final version of the manuscript, T.K., L.M., M.G., I.M., and V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was conducted within the framework of the program “Priority-2030” of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| ADF |

Actin depolymerizing factor |

| AMPK |

AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ATGL |

Adipose triglyceride lipase |

| CIN |

Сhronophin |

| DIF-1 |

Differentiation-inducing factor 1 |

| Drp1 |

Dynamin-related protein 1 |

| EGF |

Epidermal growth factor |

| ER |

Endoplasmic reticulum |

| F-actin |

Filamentous actin |

| G-actin |

Globular actin |

| LD |

Lipid droplet |

| LIMK |

LIM kinase |

| MFN2 |

Mitofusin 2 |

| PD |

Parkinson’s disease |

| PG |

Prostaglandin |

| PI(4,5)P2 |

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate |

| PLC |

Phospholipase C |

| PLIN |

Perilipin |

| PP1 |

Serine/threonine phosphatase type 1 |

| PP2A |

Serine/threonine phosphatase type 2A |

| PTEN |

Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| PTM |

Post-translational modification |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| SSH |

Slingshot phosphatase |

| TESK |

TES kinase |

| VDAC |

Voltage-dependent anion channel |

References

- Nishida, E.; Maekawa, S.; Sakai, H. Cofilin, a Protein in Porcine Brain That Binds to Actin Filaments and Inhibits Their Interactions with Myosin and Tropomyosin. Biochemistry 1984, 23, 5307–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsegiani, A.; Shah, Z. The Role of Cofilin in Age-Related Neuroinflammation. Neural Regen Res 2020, 15, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamburg, J.; Minamide, L.; Wiggan, O.; Tahtamouni, L.; Kuhn, T. Cofilin and Actin Dynamics: Multiple Modes of Regulation and Their Impacts in Neuronal Development and Degeneration. Cells 2021, 10, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremneva, E.; Makkonen, M.H.; Skwarek-Maruszewska, A.; Gateva, G.; Michelot, A.; Dominguez, R.; Lappalainen, P. Cofilin-2 Controls Actin Filament Length in Muscle Sarcomeres. Developmental Cell 2014, 31, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, S. Cofilin-Induced Structural Changes in Actin Filaments Stay Local. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 3349–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellos, G.; Frame, M.C. Cellular Functions of the ADF/Cofilin Family at a Glance. Journal of Cell Science 2016, jcs.187849. [CrossRef]

- Zuchero, J.B.; Fu, M.; Sloan, S.A.; Ibrahim, A.; Olson, A.; Zaremba, A.; Dugas, J.C.; Wienbar, S.; Caprariello, A.V.; Kantor, C.; et al. CNS Myelin Wrapping Is Driven by Actin Disassembly. Developmental Cell 2015, 34, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, S.; Minami, N.; Abe, H.; Obinata, T. Characterization of a Novel Cofilin Isoform That Is Predominantly Expressed in Mammalian Skeletal Muscle. J Biol Chem 1994, 269, 15280–15286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamburg, J.R. Proteins of the ADF/Cofilin Family: Essential Regulators of Actin Dynamics. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1999, 15, 185–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollis, E.; Mosaku, A.; Abid, A.; Buniello, A.; Cerezo, M.; Gil, L.; Groza, T.; Güneş, O.; Hall, P.; Hayhurst, J.; et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog: Knowledgebase and Deposition Resource. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, D977–D985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellenchi, G.C.; Gurniak, C.B.; Perlas, E.; Middei, S.; Ammassari-Teule, M.; Witke, W. N-Cofilin Is Associated with Neuronal Migration Disorders and Cell Cycle Control in the Cerebral Cortex. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 2347–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, A.L.; Janmey, P.A.; Louie, K.A.; Drubin, D.G. Cofilin Is an Essential Component of the Yeast Cortical Cytoskeleton. The Journal of cell biology 1993, 120, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, L.; Qi, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Wu, H. Cofilin: A Promising Protein Implicated in Cancer Metastasis and Apoptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 599065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schratt, G.M.; Tuebing, F.; Nigh, E.A.; Kane, C.G.; Sabatini, M.E.; Kiebler, M.; Greenberg, M.E. A Brain-Specific microRNA Regulates Dendritic Spine Development. Nature 2006, 439, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Zeng, M.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, X. Upregulation of Limk1 Caused by microRNA-138 Loss Aggravates the Metastasis of Ovarian Cancer by Activation of Limk1/Cofilin Signaling. Oncology Reports 2014, 32, 2070–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.-X.; Wang, X.-L.; Zhang, L.-N.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W. MicroRNA-384 Inhibits the Progression of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma through Blockade of the LIMK1/Cofilin Signaling Pathway by Binding to LIMK1. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 109, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Ji, Q.; Tang, Y.; Chen, T.; Pan, G.; Hu, S.; Bao, Y.; Peng, W.; Yin, P. Mitochondrial Translocation of Cofilin-1 Promotes Apoptosis of Gastric Cancer BGC-823 Cells Induced by Ursolic Acid. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 2451–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockeloen, C.W.; Gilhuis, H.J.; Pfundt, R.; Kamsteeg, E.J.; Agrawal, P.B.; Beggs, A.H.; Dara Hama-Amin, A.; Diekstra, A.; Knoers, N.V.A.M.; Lammens, M.; et al. Congenital Myopathy Caused by a Novel Missense Mutation in the CFL2 Gene. Neuromuscular Disorders 2012, 22, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabur, S.; Oztuzcu, S.; Oguz, E.; Demiryürek, S.; Dagli, H.; Alasehirli, B.; Ozkaya, M.; Demiryürek, A.T. Evidence for Elevated (LIMK2 and CFL1) and Suppressed (ICAM1, EZR, MAP2K2, and NOS3) Gene Expressions in Metabolic Syndrome. Endocrine 2016, 53, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.-H.; Han, J.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, Y.-S.; Park, H.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, H.; Kaang, B.-K. Cofilin Expression Induces Cofilin-Actin Rod Formation and Disrupts Synaptic Structure and Function in Aplysia Synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102, 16072–16077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamburg, J.R.; Bernstein, B.W. Actin Dynamics and Cofilin-actin Rods in Alzheimer Disease. Cytoskeleton 2016, 73, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Fu, N.; Luo, X.; Li, X.-Y.; Li, X.-P. Overexpression of Cofilin 1 in Prostate Cancer and the Corresponding Clinical Implications. Oncology Letters 2015, 9, 2757–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Wu, D.; He, F.; Fu, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, W. Study on the Significance of Cofilin 1 Overexpression in Human Bladder Cancer. Tumori 2017, 103, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wu, D.; Fu, H.; He, F.; Xu, C.; Zhou, J.; Li, D.; Li, G.; Xu, J.; Wu, Q.; et al. Cofilin 1 Promotes Bladder Cancer and Is Regulated by TCF7L2. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 92043–92054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa-Squiavinato, A.C.M.; Rocha, M.R.; Barcellos-de-Souza, P.; De Souza, W.F.; Morgado-Diaz, J.A. Cofilin-1 Signaling Mediates Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition by Promoting Actin Cytoskeleton Reorganization and Cell-Cell Adhesion Regulation in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2019, 1866, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, R.; Li, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, H. Expression of Cofilin-1 and Transgelin in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Med Sci Monit 2015, 21, 2659–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.; Chang, C.; Lin, B.; Wu, Y.; Wu, M.; Lin, L.; Huang, W.; Holz, J.D.; Sheu, T.; Lee, J.; et al. Up-regulation of Cofilin-1 in Cell Senescence Associates with Morphological Change and P27 kip1 -mediated Growth Delay. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrianantoandro, E.; Pollard, T.D. Mechanism of Actin Filament Turnover by Severing and Nucleation at Different Concentrations of ADF/Cofilin. Molecular Cell 2006, 24, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namme, J.N.; Bepari, A.K.; Takebayashi, H. Cofilin Signaling in the CNS Physiology and Neurodegeneration. IJMS 2021, 22, 10727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.T.; Simpson, T.I.; Pratt, T.; Price, D.J.; Maciver, S.K. The Motility of Glioblastoma Tumour Cells Is Modulated by Intracellular Cofilin Expression in a Concentration-Dependent Manner. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 2005, 60, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-H.; Chiu, S.-J.; Liu, C.-C.; Sheu, T.-J.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Keng, P.C.; Lee, Y.-J. Regulated Expression of Cofilin and the Consequent Regulation of P27kip1 Are Essential for G1 Phase Progression. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 2365–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lechuga, T.J.; Tith, T.; Wang, W.; Wing, D.A.; Chen, D. S-Nitrosylation of Cofilin-1 Mediates Estradiol-17β-Stimulated Endothelial Cytoskeleton Remodeling. Molecular Endocrinology 2015, 29, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée, B.; Doudeau, M.; Godin, F.; Bénédetti, H. Characterization at the Molecular Level Using Robust Biochemical Approaches of a New Kinase Protein. JoVE 2019, 59820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, T. The Age of Crosstalk: Phosphorylation, Ubiquitination, and Beyond. Molecular Cell 2007, 28, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimov, V.; Rigbolt, K.T.G.; Nielsen, M.M.; Blagoev, B. Characterization of Ubiquitination Dependent Dynamics in Growth Factor Receptor Signaling by Quantitative Proteomics. Mol. BioSyst. 2011, 7, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrao, P.; Albanèse, V.; Kenner, L.R.; Swaney, D.L.; Burlingame, A.; Villén, J.; Lim, W.A.; Fraser, J.S.; Frydman, J.; Krogan, N.J. Systematic Functional Prioritization of Protein Posttranslational Modifications. Cell 2012, 150, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.Y.; DerMardirossian, C.; Bokoch, G.M. Cofilin Phosphatases and Regulation of Actin Dynamics. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2006, 18, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toshima, J.; Toshima, J.Y.; Amano, T.; Yang, N.; Narumiya, S.; Mizuno, K. Cofilin Phosphorylation by Protein Kinase Testicular Protein Kinase 1 and Its Role in Integrin-Mediated Actin Reorganization and Focal Adhesion Formation. MBoC 2001, 12, 1131–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, M.; Hutterer, M.; Sabo, A.; Hoja, S.; Lorenz, J.; Rothhammer-Hampl, T.; Herold-Mende, C.; Floßbach, L.; Monoranu, C.; Riemenschneider, M.J. Chronophin Regulates Active Vitamin B6 Levels and Transcriptomic Features of Glioblastoma Cell Lines Cultured under Non-Adherent, Serum-Free Conditions. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleinik, N.V.; Krupenko, N.I.; Krupenko, S.A. ALDH1L1 Inhibits Cell Motility via Dephosphorylation of Cofilin by PP1 and PP2A. Oncogene 2010, 29, 6233–6244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolo, M.I.; Boggs, A.E.; Whipple, R.A.; Yoon, J.R.; Thompson, K.; Matrone, M.A.; Cho, E.H.; Balzer, E.M.; Martin, S.S. Loss of PTEN Induces Microtentacles through PI3K-Independent Activation of Cofilin. Oncogene 2013, 32, 2200–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudent, R.; Demoncheaux, N.; Diemer, H.; Collin-Faure, V.; Kapur, R.; Paublant, F.; Lafanechère, L.; Cianférani, S.; Rabilloud, T. A Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of Cofilin Phosphorylation in Myeloid Cells and Its Modulation Using the LIM Kinase Inhibitor Pyr1. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, Y.; Ho, H.J.; Wang, C.; Guan, J.-L. Tyrosine Phosphorylation of Cofilin at Y68 by V-Src Leads to Its Degradation through Ubiquitin–Proteasome Pathway. Oncogene 2010, 29, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfannstiel, J.; Cyrklaff, M.; Habermann, A.; Stoeva, S.; Griffiths, G.; Shoeman, R.; Faulstich, H. Human Cofilin Forms Oligomers Exhibiting Actin Bundling Activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 49476–49484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Gu, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, Q.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, M.X.; Feng, J.; Huang, O.; et al. N-Terminal α-Amino SUMOylation of Cofilin-1 Is Critical for Its Regulation of Actin Depolymerization. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogl, A.M.; Phu, L.; Becerra, R.; Giusti, S.A.; Verschueren, E.; Hinkle, T.B.; Bordenave, M.D.; Adrian, M.; Heidersbach, A.; Yankilevich, P.; et al. Global Site-Specific Neddylation Profiling Reveals That NEDDylated Cofilin Regulates Actin Dynamics. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2020, 27, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, R. Towards Computational Models of Identifying Protein Ubiquitination Sites. CDT 2019, 20, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainullin, M.R.; Zhukov, I.Y.; Zhou, X.; Mo, Y.; Astakhova, L.; Ernberg, I.; Matskova, L. Degradation of Cofilin Is Regulated by Cbl, AIP4 and Syk Resulting in Increased Migration of LMP2A Positive Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cells. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 9012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buneeva, O.; Medvedev, A. Atypical Ubiquitination and Parkinson’s Disease. IJMS 2022, 23, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Liu, X.; Zheng, B.; Xing, C.; Liu, J. Role of K63-Linked Ubiquitination in Cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madiraju, C.; Novack, J.P.; Reed, J.C.; Matsuzawa, S. K63 Ubiquitination in Immune Signaling. Trends in Immunology 2022, 43, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Weng, W.; Guo, R.; Zhou, J.; Xue, J.; Zhong, S.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, M.X.; Pan, S.-J.; Li, Y. Olig2 SUMOylation Protects against Genotoxic Damage Response by Antagonizing P53 Gene Targeting. Cell Death Differ 2020, 27, 3146–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwin, R.D.; Craven, R.A.; Harnden, P.; Hanrahan, S.; Totty, N.; Knowles, M.; Eardley, I.; Selby, P.J.; Banks, R.E. Proteomic Changes in Renal Cancer and Co-ordinate Demonstration of Both the Glycolytic and Mitochondrial Aspects of the Warburg Effect. Proteomics 2003, 3, 1620–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, B.T.; Volbracht, C.; Tan, K.O.; Li, R.; Yu, V.C.; Li, P. Mitochondrial Translocation of Cofilin Is an Early Step in Apoptosis Induction. Nat Cell Biol 2003, 5, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.; Sharma, R.; Gupta, R.; Ast, T.; Chan, C.; Durham, T.J.; Goodman, R.P.; Grabarek, Z.; Haas, M.E.; Hung, W.H.W.; et al. MitoCarta3.0: An Updated Mitochondrial Proteome Now with Sub-Organelle Localization and Pathway Annotations. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, D1541–D1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, L.; Waclawczyk, M.S.; Tang, S.; Hanschmann, E.-M.; Gellert, M.; Rust, M.B.; Culmsee, C. Cofilin1 Oxidation Links Oxidative Distress to Mitochondrial Demise and Neuronal Cell Death. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovaleva, T.F.; Maksimova, N.S.; Pchelin, P.V.; Pershin, V.I.; Tkachenko, N.M.; Gainullin, M.R.; Mukhina, I.V. A New Cofilin-Dependent Mechanism for the Regulation of Brain Mitochondria Biogenesis and Degradation. Sovrem Tehnol Med 2020, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapeña-Luzón, T.; Rodríguez, L.R.; Beltran-Beltran, V.; Benetó, N.; Pallardó, F.V.; Gonzalez-Cabo, P. Cofilin and Neurodegeneration: New Functions for an Old but Gold Protein. Brain Sciences 2021, 11, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, L.; Rust, M.B.; Culmsee, C. Actin(g) on Mitochondria – a Role for Cofilin1 in Neuronal Cell Death Pathways. Biological Chemistry 2019, 400, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-B.; Zhang, H.-W.; Fu, R.-Q.; Hu, X.-Y.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.-N.; Liu, Y.-X.; Liu, X.; Hu, J.-J.; Deng, Q.; et al. Mitochondrial Fission and Mitophagy Depend on Cofilin-Mediated Actin Depolymerization Activity at the Mitochondrial Fission Site. Oncogene 2018, 37, 1485–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, S.; Woo, J.A.; Lakshmana, M.K.; Uhlar, C.; Ankala, V.; Boggess, T.; Liu, T.; Hong, Y.; Mook-Jung, I.; Kim, S.J.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Calcium Deregulation by the RanBP9-cofilin Pathway. FASEB j. 2013, 27, 4776–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhou, J.; Budhraja, A.; Hu, X.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhou, T.; Li, P.; Liu, E.; et al. Mitochondrial Translocation and Interaction of Cofilin and Drp1 Are Required for Erucin-Induced Mitochondrial Fission and Apoptosis. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 1834–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, T.; Miura, K.; Han, R.; Seto-Tetsuo, F.; Arioka, M.; Igawa, K.; Tomooka, K.; Sasaguri, T. Differentiation-Inducing Factor 1 Activates Cofilin through Pyridoxal Phosphatase and AMP-Activated Protein Kinase, Resulting in Mitochondrial Fission. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 2023, 152, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, F.; Zdanov, S.; Levine, R.L.; Pariser, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yu, L.-R.; Veenstra, T.D.; Shacter, E. Oxidant-Induced Apoptosis Is Mediated by Oxidation of the Actin-Regulatory Protein Cofilin. Nat Cell Biol 2009, 11, 1241–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotiadis, V.N.; Leadsham, J.E.; Bastow, E.L.; Gheeraert, A.; Whybrew, J.M.; Bard, M.; Lappalainen, P.; Gourlay, C.W. Identification of New Surfaces of Cofilin That Link Mitochondrial Function to the Control of Multi-Drug Resistance. Journal of Cell Science 2012, jcs.099390. [CrossRef]

- Cichon, J.; Sun, C.; Chen, B.; Jiang, M.; Chen, X.A.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G. Cofilin Aggregation Blocks Intracellular Trafficking and Induces Synaptic Loss in Hippocampal Neurons. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 3919–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovaleva, T.F.; Maksimova, N.S.; Zhukov, I.Yu.; Pershin, V.I.; Mukhina, I.V.; Gainullin, M.R. Cofilin: Molecular and Cellular Functions and Its Role in the Functioning of the Nervous System. Neurochem. J. 2019, 13, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Meng, L.; Dai, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Zheng, Y.; Zha, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Z. Cofilin 1 Promotes the Aggregation and Cell-to-Cell Transmission of α-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2020, 529, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez, D.G.; Lee, M.K.; Feany, M.B. α-Synuclein Induces Mitochondrial Dysfunction through Spectrin and the Actin Cytoskeleton. Neuron 2018, 97, 108–124.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.E.; Woo, J.A. Cofilin, a Master Node Regulating Cytoskeletal Pathogenesis in Alzheimer’s Disease. JAD 2019, 72, S131–S144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minamide, L.S.; Maiti, S.; Boyle, J.A.; Davis, R.C.; Coppinger, J.A.; Bao, Y.; Huang, T.Y.; Yates, J.; Bokoch, G.M.; Bamburg, J.R. Isolation and Characterization of Cytoplasmic Cofilin-Actin Rods. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 5450–5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsie, L.N.; Desmond, C.R.; Truant, R. Cofilin Nuclear-Cytoplasmic Shuttling Affects Cofilin-Actin Rod Formation During Stress. Journal of Cell Science 2012, jcs.097667. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, B.W.; Chen, H.; Boyle, J.A.; Bamburg, J.R. Formation of Actin-ADF/Cofilin Rods Transiently Retards Decline of Mitochondrial Potential and ATP in Stressed Neurons. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2006, 291, C828–C839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehklau, K.; Gurniak, C.B.; Conrad, M.; Friauf, E.; Ott, M.; Rust, M.B. ADF/Cofilin Proteins Translocate to Mitochondria during Apoptosis but Are Not Generally Required for Cell Death Signaling. Cell Death Differ 2012, 19, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Shen, L.; Shi, J.; Gao, N. ROCK1 Activation-Mediated Mitochondrial Translocation of Drp1 and Cofilin Are Required for Arnidiol-Induced Mitochondrial Fission and Apoptosis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2020, 39, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehklau, K.; Hoffmann, L.; Gurniak, C.B.; Ott, M.; Witke, W.; Scorrano, L.; Culmsee, C.; Rust, M.B. Cofilin1-Dependent Actin Dynamics Control DRP1-Mediated Mitochondrial Fission. Cell Death Dis 2017, 8, e3063–e3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Miao, R.; Wei, J.; Wu, H.; Tian, J. Advances in Multi-Omics Study of Biomarkers of Glycolipid Metabolism Disorder. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2022, 20, 5935–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izdebska, M.; Zielińska, W.; Hałas-Wiśniewska, M.; Grzanka, A. Involvement of Actin and Actin-Binding Proteins in Carcinogenesis. Cells 2020, 9, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Chen, Z.; Mi, H.; Yu, X. Cofilin Acts as a Booster for Progression of Malignant Tumors Represented by Glioma. Cancer Manag Res 2022, 14, 3245–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Chen, J. Cofilin-Mediated Actin Dynamics Promotes Actin Bundle Formation during Drosophila Bristle Development. MBoC 2016, 27, 2554–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M.; Takano, S.; Sogawa, K.; Noda, K.; Yoshitomi, H.; Ishibashi, M.; Mogushi, K.; Takizawa, H.; Otsuka, M.; Shimizu, H.; et al. Immune-complex Level of Cofilin-1 in Sera Is Associated with Cancer Progression and Poor Prognosis in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Science 2017, 108, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wang, A.; Cao, J.; Chen, L. Apelin/APJ System: An Emerging Therapeutic Target for Respiratory Diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2919–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, R.; Yang, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Yang, S.; Feng, Z.; Bi, J. NCAM Regulates the Proliferation, Apoptosis, Autophagy, EMT, and Migration of Human Melanoma Cells via the Src/Akt/mTOR/Cofilin Signaling Pathway. J of Cellular Biochemistry 2020, 121, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Pu, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, L.; Xiao, J.; Liu, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Ni, M.; et al. ATG16L1 Phosphorylation Is Oppositely Regulated by CSNK2/Casein Kinase 2 and PPP1/Protein Phosphatase 1 Which Determines the Fate of Cardiomyocytes during Hypoxia/Reoxygenation. Autophagy 2015, 11, 1308–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celeste Morley, S.; Sun, G.; Bierer, B.E. Inhibition of Actin Polymerization Enhances Commitment to and Execution of Apoptosis Induced by Withdrawal of Trophic Support. J of Cellular Biochemistry 2003, 88, 1066–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Youle, R.J. The Role of Mitochondria in Apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009, 43, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, W.; Kahle, P.J. Regulation of PINK1-Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy. Autophagy 2011, 7, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorowicz, M.A.; De Vries-Schneider, R.L.A.; Rüb, C.; Becker, D.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Alessi Wolken, D.M.; Voos, W.; Liu, Y.; Przedborski, S. Cytosolic Cleaved PINK 1 Represses P Arkin Translocation to Mitochondria and Mitophagy. EMBO Reports 2014, 15, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Tan, Y. Lipid Droplet–Mitochondria Contacts in Health and Disease. IJMS 2024, 25, 6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Meyer, T.; Smethurst, D.; Neuhaus, L.; Heyden, J.; Broeskamp, F.; Edrich, E.; Knittelfelder, O.; Smolnig, M.; Kolb, D.; et al. Loss of Actin Dynamics Leads to VDAC Dependent MAPK Signalling and Altered Lipid Homeostasis That Promotes Cell Death in Yeast Cells 2022.

- Cui, L.; Liu, P. Two Types of Contact Between Lipid Droplets and Mitochondria. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 618322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, G.E.; So, C.M.; Edwards, W.; Herring, L.E.; Coleman, R.A.; Klett, E.L.; Cohen, S. Perilipin 5 Interacts with Fatp4 at Membrane Contact Sites to Promote Lipid Droplet-to-Mitochondria Fatty Acid Transport; Cell Biology, 2022.

- Giedt, M.S.; Thomalla, J.M.; Johnson, M.R.; Lai, Z.W.; Tootle, T.L.; Welte, M.A. Adipose Triglyceride Lipase Promotes Prostaglandin-Dependent Actin Remodeling by Regulating Substrate Release from Lipid Droplets; Cell Biology, 2021.

- Serezani, C.H.; Kane, S.; Medeiros, A.I.; Cornett, A.M.; Kim, S.-H.; Marques, M.M.; Lee, S.-P.; Lewis, C.; Bourdonnay, E.; Ballinger, M.N.; et al. PTEN Directly Activates the Actin Depolymerization Factor Cofilin-1 During PGE 2 -Mediated Inhibition of Phagocytosis of Fungi. Sci. Signal. 2012, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Thein, S.; Wang, X.; Bi, X.; Ericksen, R.E.; Xu, F.; Han, W. BSCL2/Seipin Regulates Adipogenesis through Actin Cytoskeleton Remodelling. Human Molecular Genetics 2014, 23, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samstag, Y.; John, I.; Wabnitz, G.H. Cofilin: A Redox Sensitive Mediator of Actin Dynamics during T-cell Activation and Migration. Immunological Reviews 2013, 256, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fang, N.; Xiong, J.; Du, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ji, W.-K. An ESCRT-Dependent Step in Fatty Acid Transfer from Lipid Droplets to Mitochondria through VPS13D−TSG101 Interactions. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfisterer, S.G.; Gateva, G.; Horvath, P.; Pirhonen, J.; Salo, V.T.; Karhinen, L.; Varjosalo, M.; Ryhänen, S.J.; Lappalainen, P.; Ikonen, E. Role for Formin-like 1-Dependent Acto-Myosin Assembly in Lipid Droplet Dynamics and Lipid Storage. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Man, S.; Tao, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Guo, L.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.; Gao, W. The Lipid Droplet in Cancer: From Being a Tumor-supporting Hallmark to Clinical Therapy. Acta Physiologica 2024, e14087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safi, R.; Menéndez, P.; Pol, A. Lipid Droplets Provide Metabolic Flexibility for Cancer Progression. FEBS Letters 2024, 598, 1301–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petan, T. Lipid Droplets in Cancer. In Organelles in Disease; Pedersen, S.H.F., Barber, D.L., Eds.; Reviews of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; Vol. 185, pp. 53–86 ISBN 978-3-031-22594-9.

- Jarc, E.; Petan, T. A Twist of FATe: Lipid Droplets and Inflammatory Lipid Mediators. Biochimie 2020, 169, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Dutra, F.S.; Bozza, P.T. Lipid Droplets Diversity and Functions in Inflammation and Immune Response. Expert Review of Proteomics 2021, 18, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadoorian, A.; Du, X.; Yang, H. Lipid Droplet Biogenesis and Functions in Health and Disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2023, 19, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, B.C.; Walsh, A.E.; Kluemper, J.C.; Johnson, L.A. Lipid Droplets in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F. Lipid Metabolism and Alzheimer’s Disease: Clinical Evidence, Mechanistic Link and Therapeutic Promise. The FEBS Journal 2023, 290, 1420–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Luo, W.; Li, F.; Qin, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wu, Y.; et al. Dysregulation of Cofilin-1 Activity—the Missing Link between Herpes Simplex Virus Type-1 Infection and Alzheimer’s Disease. Critical Reviews in Microbiology 2020, 46, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.K.; Babcock, I.W.; Minamide, L.S.; Shaw, A.E.; Bamburg, J.R.; Kuhn, T.B. Direct Interaction of HIV Gp120 with Neuronal CXCR4 and CCR5 Receptors Induces Cofilin-Actin Rod Pathology via a Cellular Prion Protein- and NOX-Dependent Mechanism. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huo, C.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, P.; Na, H.; Zhang, H.; et al. The Proteomics of Lipid Droplets: Structure, Dynamics, and Functions of the Organelle Conserved from Bacteria to Humans. J Lipid Res 2012, 53, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Leu, J.-D.; Lee, Y.-J. The Actin Depolymerizing Factor (ADF)/Cofilin Signaling Pathway and DNA Damage Responses in Cancer. IJMS 2015, 16, 4095–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Elzakra, N.; Xu, S.; Xiao, G.G.; Yang, Y.; Hu, S. Investigation of Three Potential Autoantibodies in Sjogren’s Syndrome and Associated MALT Lymphoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 30039–30049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Liu, X.; Cao, J.; Chen, B. SEPT7 Overexpression Inhibits Glioma Cell Migration by Targeting the Actin Cytoskeleton Pathway. Oncology Reports 2016, 35, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).