Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

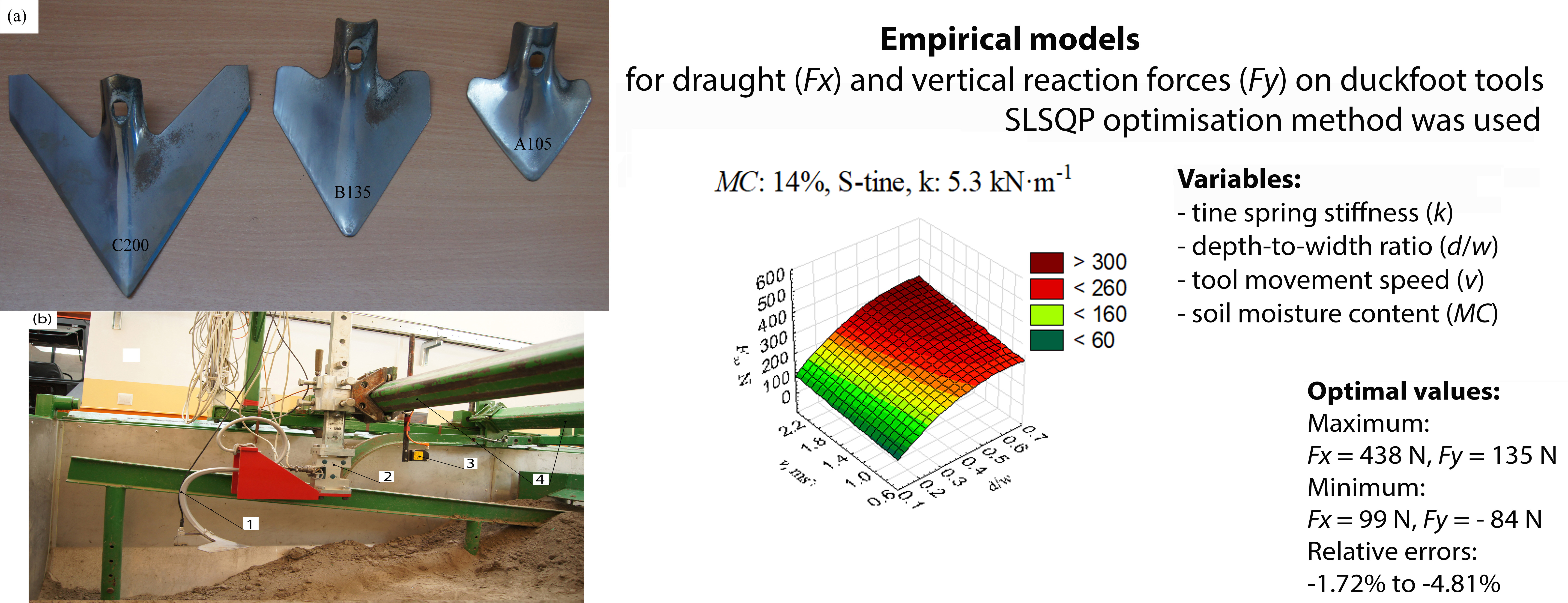

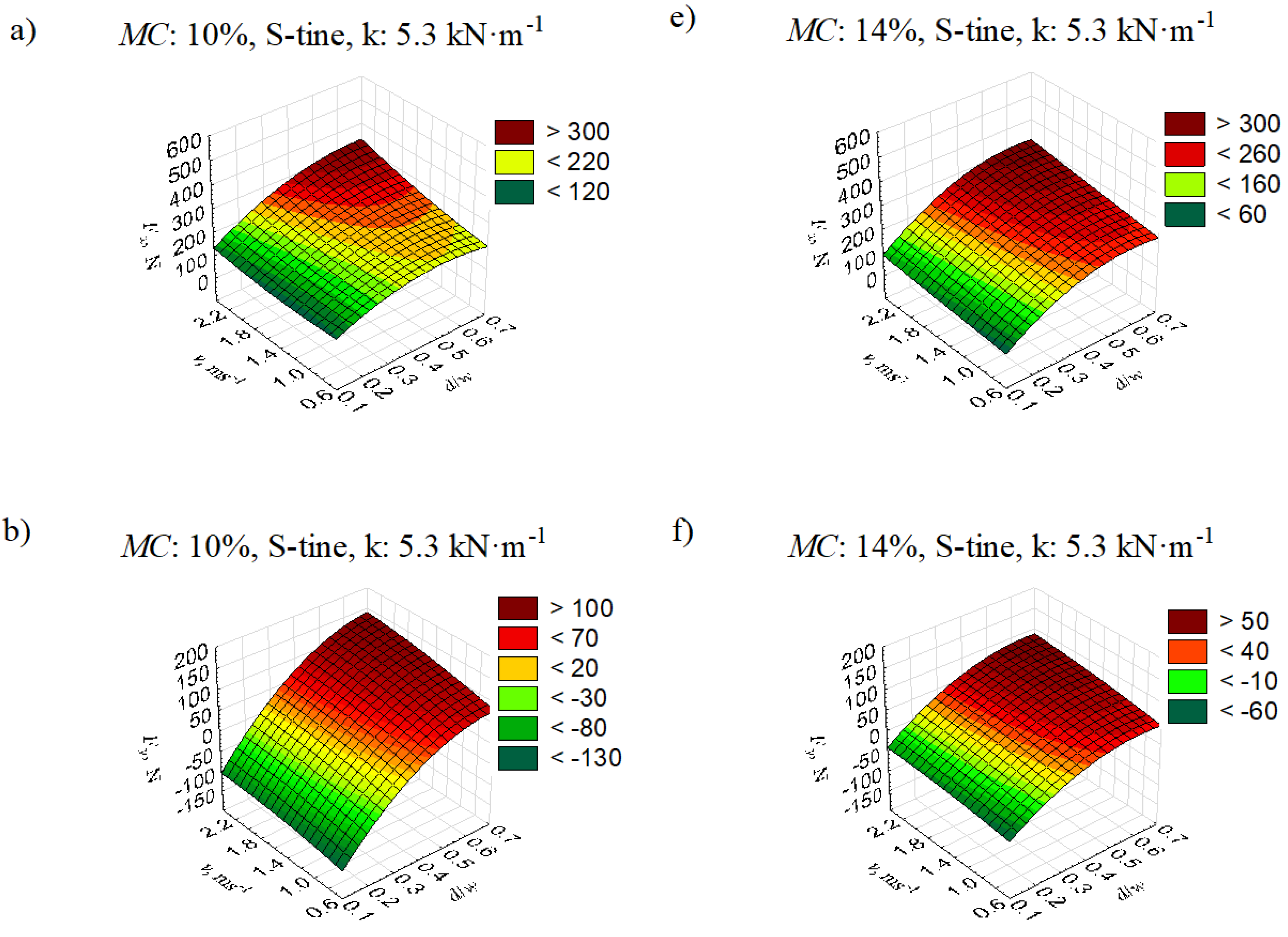

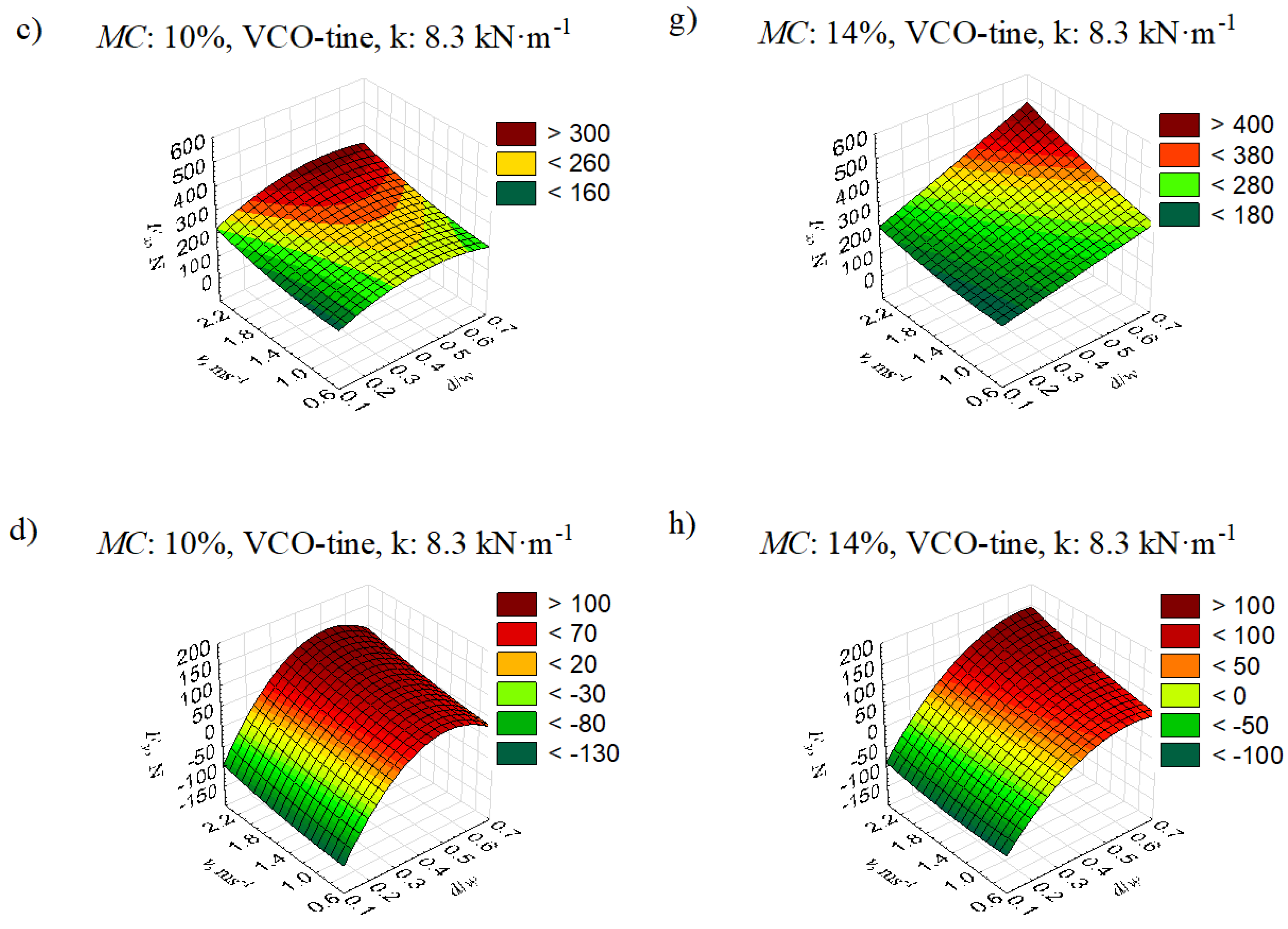

The paper presents the development of empirical mathematical models of draught force, Fx, and vertical force, Fy acting on duckfoots attached to the tines with different stiffness and working in various soil conditions. The models consider technical variables such as stiffness, k, tool depth-to-width ratio, d/w, tool movement speed, v, and soil moisture content, MC, which have not been thoroughly analysed in the literature. The correlation coefficients for predicting Fx and Fy values were 0.4996 and 0.6227, respectively. Statistical analysis confirmed the significant effect of these parameters on the forces acting on the tools, with the variables d/w and v having the most critical impact on Fx and Fy. The SLSQP (Sequential Least Squares Programming) optimisation method was used to determine the optimal values of technical variables. The maximum value of Fx was 438.55 N, and the minimum was 98.98 N, with variable values at the edges of the studied ranges. Similarly, Fy values of 135.25 N and -84.55 N, respectively, were obtained. Optimisation results showed good fitness with experimental results, and minor relative errors confirmed the accuracy of the model predictions. The justification of the research results allowed us to conclude that there is no basis for rejecting the explanatory hypotheses. The developed models have a generalisable value in the analysed ranges, and further research should focus on creating more universal, theoretical models of soil-tool interactions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

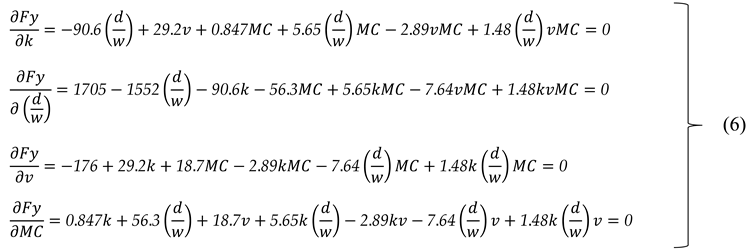

2.1. Soil Properties and Test Object

2.2. Soil Bin with Equipment and Measurement Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. General Formula of the Empirical Model

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of the Statistical Analysis

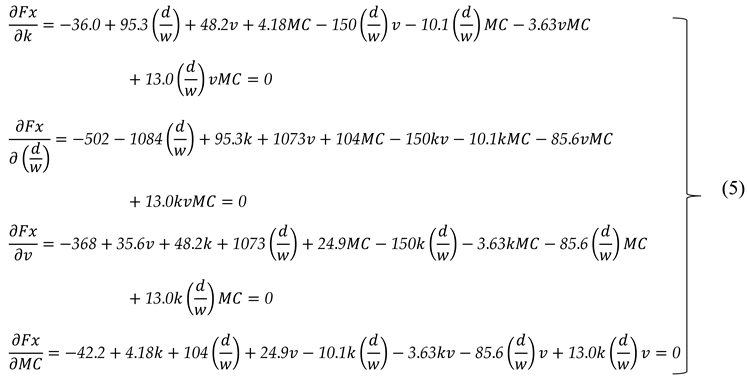

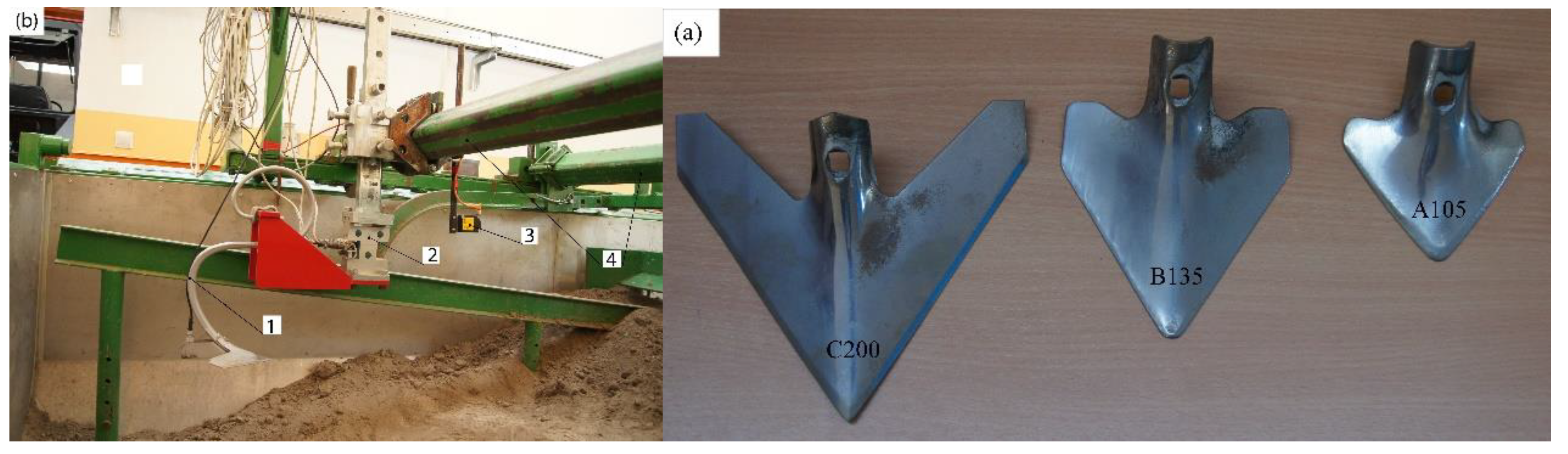

3.2. Mathematical Empirical Models

3.2.1. Detailed Model Description for Draught Force, Fx

3.2.2. Model Description for Vertical Force, Fy

3.3. Optimisation of Parameters and Values of Objective Functions Fx and Fy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| d | Working depth of the tool, duckfoot, mm |

| df | Furrow depth, mm |

| Fx | Draught force, the horizontal component of the duckfoot pressure force on the soil in the XYZ system, N |

| Fy | vertical component of the duckfoot pressure force on the soil in the XYZ system, N |

| k | Spring constant, stiffness, kN·m–1 |

| MC | Soil moisture content, % |

| r | Pearson's partial correlation coefficient, – |

| R | Multiple correlation coefficient, – |

| v | Speed of tool movement, m·s–1 |

| w | Width of the working element, tools, mm |

References

- Shaheb, M.R.; Venkatesh, R.; Shearer, S.A. A Review on the Effect of Soil Compaction and its Management for Sustainable Crop Production. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 46, 417–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M.A.; Anderson, W.K. Soil compaction in cropping systems: A review of the nature, causes and possible solutions. Soil Tillage Res. 2005, 82, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.N.; Tanveer, M.; Shahzad, B.; Yang, G.; Fahad, S.; Ali, S.; Bukhari, M.A.; Tung, S.A.; Hafeez, A.; Souliyanonh, B. Soil compaction effects on soil health and crop productivity: an overview. Env. Sci Pollut Res 2017, 24, 10056–10067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, T.; Sandin, M.; Colombi, T.; Horn, R.; Or, D. Historical increase in agricultural machinery weights enhanced soil stress levels and adversely affected soil functioning. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 194, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Drewry, J.; Beare, M.; Eger, A.; Müller, K. Compaction induced soil structural degradation affects productivity and environmental outcomes: A review and New Zealand case study. Geoderma 2021, 395, 115035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavanti, R.F.R.; Freddi, O. da S.; Marchioro, V.; Tavanti, T.R.; Galindo, F.; Wruck, F.J.; Shiratsuchi, L.; Breda, C.C. Least limiting water as a soil indicator in an integrated crop-livestock systems of the Cerrado, Brazil. Geoderma Reg. 2019, 19, e00232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacomi, C.; Popescu, O. an Innovative Tool for in-Row Cultivation. Agrolife Sci. J. 2015, 4, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, J.; Mansuy, A.; Christina, M. Micro-Mechanization to Manage Weed in Sugar Cane. Sugar Tech 2024, 0–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mt Pleasant, J.; Burt, R.F.; Frisch, J.C. Integrating mechanical and chemical weed management in corn (Zea mays). Weed Technol. 1994, 8, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Gallandt, E.R. Evidence of synergy with ‘stacked’ intrarow cultivation tools. Weed Res. 2018, 58, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgujar, C.; Das, S.; Figueroa, D.M.; Flippo, D. Application of Computational Intelligence Methods in Agricultural Soil–Machine Interaction: A Review. Agric. 2023, 13, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makange, N.R.; Ji, C.; Torotwa, I. Prediction of cutting forces and soil behavior with discrete element simulation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 179, 105848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sishodia, R.P.; Ray, R.L.; Singh, S.K. Applications of remote sensing in precision agriculture: A review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkakini, S.O.; Vurasi, N.M. Effects of Moisture Content, Bulk Density and Tractor Forward Speeds on Energy Requirement of Disc Plough. Technology 2015, 6, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Obour, P.B.; Lamandé, M.; Edwards, G.; Sørensen, C.G.; Munkholm, L.J. Predicting soil workability and fragmentation in tillage: a review. Soil Use Manag. 2017, 33, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tim Chamen, W.C.; Moxey, A.P.; Towers, W.; Balana, B.; Hallett, P.D. Mitigating arable soil compaction: A review and analysis of available cost and benefit data. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 146, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Halfi, K.M.M. Evaluation of deep tillage in cohesive soils of Queensland, Australia. 2021.

- Hoseinian, S.H.; Hemmat, A.; Esehaghbeygi, A.; Shahgoli, G.; Baghbanan, A. Development of a dual sideway-share subsurface tillage implement: Part 2. Effect of tool geometry on tillage forces and soil disturbance characteristics. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 215, 105200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanian-Koushkaki, H.; Mahmoodi-Eshkaftaki, M.; Azimi-Nejadian, H. Simulation of Draught Force During Chisel Ploughing Using Discrete Element Method. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 47, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, S.; Ozaslan, C. Evaluating the performance of rotary and tine inter-row cultivators at different working speeds. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2021, 23, 1255–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Vangessel, M.J.; Schweizer, E.E.; Wilson, R.G.; Wiles, L.J.; Westra, P. Impact of timing and frequency of in-row cultivation for weed control in dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Weed Technol. 1998, 12, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour-Gilandeh, Y.; Fazel-Niari, Z.; Shahgoli, G.; Bavafa, M. Design and construction of a high speed inter-row cultivator. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 110–116, 4914–4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, I.; Hudoba, Z.; Oldal, I.; Csatár, A.; Fenyvesi, L. Discrete element modeling of vibrating tillage tools. Eng. Comput. (Swansea, Wales) 2015, 32, 308–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuwa, S.I. Performance evaluation of tillage tines operating under different depths in a sandy clay loam soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2009, 103, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, E.; Legué, V.; Kolb, E.; Legué, V.; Phys-, M.B.P.R.I. Physical Root-Soil Interactions To cite this version : HAL Id : hal-01609984 Physical Root-Soil Interactions. 2017, 14.

- Aikins, K.A.; Barr, J.B.; Ucgul, M.; Jensen, T.A.; Antille, D.L.; Desbiolles, J.M.A. No-tillage furrow opener performance: A review of tool geometry, settings and interactions with soil and crop residue. Soil Res. 2020, 58, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwiti, F.M.; Gitau, A.N.; Mbuge, D.O. Effects of soil-tool interaction and mechanical pulverization of arable soils in tillage-a comprehensive review. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2023, 25, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walunj, A.; Chen, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zeng, Z. Modeling Soil–Plant–Machine Dynamics Using Discrete Element Method: A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J. Modeling of soil-claw interaction using the discrete element method (DEM). Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 158, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, R.J. A review of the effect of implement geometry on soil failure and implement forces. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 97, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanauskas, V.; Janulevičius, A. Effect of tillage implement (spring tine cultivator, disc harrow), soil texture, forward speed, and tillage depth on fuel consumption and tillage quality. J. Agric. Eng. 2022, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowski, A.; Klonowski, J.; Green, O.; Świetochowski, A.; Sypuła, M.; Struzyk, A.; Nowakowski, T.; Chlebowski, J.; Kamiński, J.; Kostyra, K.; et al. Duckfoot tools connected with flexible and stiff tines: Three components of resistances and soil disturbance. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 158, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurocode 1 Part 4: Basis of design and actions on structures. Actions in silos and tanks; European Committee for Standardization, Amsterdam, 2006.

- Hegge, B.J.; Masselink, G. Spectral analysis of geomorphic time series: Auto-spectrum. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 1996, 21, 1021–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G. A New View of Statistics. Sportscience 2000, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Moré, J.J.; Sorensen, D.C. Computing a Trust-Region Step. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 1983, 4, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luth, H.; Wismer, R. Performance of plane soil cutting blades in sand. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 1971, 14, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejman, K.; Owsiak, Z.; Pieczarka, K.; Sekutowski, T. Vertical Forces Acting on Cultivator Tines in the Aspect of Shearing Speed and Flexibility of Tines. Agric. Eng. 2018, 22, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, R.K.; Raheman, H. Draught Prediction of Agricultural Implements using Reference Tillage Tools in Sandy Clay Loam Soil. Biosyst. Eng. 2006, 94, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, R.L.; Zhang, Z.X. Evaluation of factors and current approaches related to computerized design of tillage tools: A review. J. Terramechanics 1998, 35, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmulevich, I.; Asaf, Z.; Rubinstein, D. Interaction between soil and a wide cutting blade using the discrete element method. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 97, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Fundamentals of Hierarchical Linear and Multilevel Modeling. Hierarchical Linear Model. Guid. Appl. 2014, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKyes, E.; Desir, F.L. Prediction and field measurements of tillage tool draft forces and efficiency in cohesive soils. Soil Tillage Res. 1984, 4, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielke, J.M. Interactions of the cutting edge of tillage implements with soil. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1996, 63, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogrekci, I.; Godwin, R.J. Development of a mechanical transducer for real-time soil tilth sensing. Biosyst. Eng. 2007, 98, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwualu, A.P.; Watts, K.C. Draught and vertical forces obtained from dynamic soil cutting by plane tillage tools. Soil Tillage Res. 1998, 48, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, J. V. The performance of a rigid tine in relation to soil properties and speed. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1979, 24, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoor, G.; Godwin, R.J. An experimental investigation into the deep loosening of soil by rigid tines. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1978, 23, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Force | Fx | Fy | |||||||

| Effect | DF* | SS | MS | F | p-value | SS | MS | F | p-value |

| k | 1 | 1.49E+07 | 1.49E+07 | 5288.0 | <0.0001 | 876803 | 876803 | 399.2 | <0.0001 |

| MC | 1 | 9.03E+05 | 9.03E+05 | 321.5 | <0.0001 | 31339 | 31339 | 14.3 | 0.0002 |

| d/w | 8 | 1.80E+08 | 2.25E+07 | 8007.0 | <0.0001 | 80128455 | 10016057 | 4559.3 | <0.0001 |

| v | 2 | 2.26E+07 | 1.13E+07 | 4019.7 | <0.0001 | 5281953 | 2640976 | 1202.2 | <0.0001 |

| k × MC | 1 | 1.12E+06 | 1.12E+06 | 397.7 | <0.0001 | 108663 | 108663 | 49.5 | <0.0001 |

| k × d/w | 8 | 2.49E+06 | 3.12E+05 | 110.9 | <0.0001 | 10755764 | 1344471 | 612.0 | <0.0001 |

| MC × d/w | 8 | 4.97E+06 | 6.21E+05 | 221.3 | <0.0001 | 2644064 | 330508 | 150.5 | <0.0001 |

| k × v | 2 | 1.34E+06 | 6.72E+05 | 239.1 | <0.0001 | 248686 | 124343 | 56.6 | <0.0001 |

| MC × v | 2 | 3.49E+05 | 1.74E+05 | 62.1 | <0.0001 | 20131 | 10066 | 4.6 | 0.0102 |

| d/w × v | 16 | 4.78E+06 | 2.99E+05 | 106.5 | <0.0001 | 1144510 | 71532 | 32.7 | <0.0001 |

| k × MC × d/w | 8 | 3.88E+06 | 4.84E+05 | 172.5 | <0.0001 | 4609706 | 576213 | 262.3 | <0.0001 |

| k × MC × v | 2 | 1.93E+05 | 9.64E+04 | 34.3 | <0.0001 | 22809 | 11404 | 5.2 | 0.0056 |

| k × d/w × v | 16 | 5.39E+05 | 3.37E+04 | 12.0 | <0.0001 | 302541 | 18909 | 8.6 | <0.0001 |

| MC × d/w × v | 16 | 4.05E+05 | 2.53E+04 | 9.0 | <0.0001 | 142454 | 8903 | 4.1 | <0.0001 |

| k × MC × d/w × v | 16 | 7.39E+05 | 4.62E+04 | 16.4 | <0.0001 | 109099 | 6819 | 3.1 | <0.0001 |

| Error | 30222 | 8.49E+07 | 2.81E+03 | 66392971 | 2197 | ||||

| Parameter | k | MC | d/w | v | Fx | Fy |

| k | 1.000 | |||||

| MC | -0.123a | 1.000 | ||||

| d/w | -0.057a | -0.010 | 1.000 | |||

| v | -0.033a | -0.009 | 0.008 | 1.000 | ||

| Fx | 0.165a | -0.019a | 0.326a | 0.257a | 1.000 | |

| Fy | 0.031a | -0.032a | 0.547a | 0.168a | 0.566a | 1.000 |

| Force | Fx | Fy | ||||||

| Sign of βi | βi | SE* | t-test | p | βi | SE | t-test | p |

| β0 | 486 | 99.57 | 4.88 | <0.0001 | -267 | 7.14 | -37.35 | <0.0001 |

| β1 | -36.0 | 14.19 | -2.54 | 0.0112 | ||||

| β2 | -502 | 245.97 | -2.04 | 0.0412 | 1705 | 51.15 | 33.34 | <0.0001 |

| β3 | -368 | 65.94 | -5.58 | <0.0001 | -176 | 13.17 | -13.36 | <0.0001 |

| β4 | -42.2 | 8.31 | -5.08 | <0.0001 | ||||

| β5 | ||||||||

| β6 | -542 | 22.57 | -24.01 | <0.0001 | -776 | 15.79 | -49.14 | <0.0001 |

| β7 | 17.8 | 2.27 | 7.81 | <0.0001 | ||||

| β8 | ||||||||

| β9 | 95.3 | 35.34 | 2.70 | 0.0070 | -90.6 | 7.03 | -12.87 | <0.0001 |

| β10 | 48.2 | 9.43 | 5.11 | <0.0001 | 29.2 | 1.88 | 15.56 | <0.0001 |

| β11 | 4.18 | 1.20 | 3.49 | 0.0005 | 0.847 | 0.08 | 9.97 | <0.0001 |

| β12 | 1073 | 161.44 | 6.65 | <0.0001 | ||||

| β13 | 104 | 20.53 | 5.05 | <0.0001 | -56.3 | 4.15 | -13.56 | <0.0001 |

| β14 | 24.9 | 5.51 | 4.52 | <0.0001 | 18.7 | 1.12 | 16.73 | <0.0001 |

| β15 | -150 | 23.45 | -6.41 | <0.0001 | ||||

| β16 | -10.1 | 2.99 | -3.40 | 0.0007 | 5.65 | 0.63 | 8.97 | <0.0001 |

| β17 | -3.63 | 0.80 | -4.53 | <0.0001 | -2.89 | 0.17 | -16.97 | <0.0001 |

| β18 | -85.6 | 13.65 | -6.28 | <0.0001 | -7.64 | 1.11 | -6.89 | <0.0001 |

| β19 | 13.0 | 1.99 | 6.53 | <0.0001 | 1.48 | 0.17 | 8.93 | <0.0001 |

| R | 0.4996 | 0.6227 | ||||||

| Force | Fx | Fy | ||||||||

| Effect | SS* | DF | MS | F-test | p | SS | DF | MS | F-test | p |

| Regression | 1.68E+09 | 18 | 93089696 | 11216 | <0.0001 | 110665024 | 13 | 8512694 | 2093 | <0.0001 |

| Residual | 2.52E+08 | 30312 | 8300 | 123326543 | 30317 | 4068 | ||||

| Total | 1.93E+09 | 30330 | 233991567 | 30330 | ||||||

| Grand total | 3.35E+08 | 30329 | 201439848 | 30329 | ||||||

| Adjusted regression | 1.68E+09 | 18 | 93089696 | 8421 | <0.0001 | 110665024 | 13 | 8512694 | 1282 | <0.0001 |

| Variables | Fxmin | Fxmax | Fymin | Fymax |

| Tine stiffness k, kN·m⁻¹ | 5.3 | 8.3 | 5.3 | 8.3 |

| Tool depth to width ratio d/w, – | 0.15 | 0.67 | 0.15 | 0.62 |

| Tool speed v, m·s⁻¹ | 0.84 | 2.31 | 0.84 | 2.31 |

| Soil moisture, MC, | 14 | 14 | 10 | 14 |

| Optimum force value, N | 98.98 | 438.55 | -84.55 | 135.25 |

| Value of measured force, N | 102.88 | 431.15 | -80.67 | 132.74 |

| Model Error, % | 3.79 | -1.72 | -4.81 | -1.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).