1. Introduction

The extracellular matrix (ECM) of echinoderms has been in the focus of research interests and intensively studied in the past 50 years, due to its unique mutable collagenous tissue (MCT). In the holothurian ECM, collagen fibers, composed of fibrillin-like proteins, proteoglycans, fucosylated chondroitin sulfate, tensilin, stiparin, novel stiffening factor (NSF), matrikines and various other small molecules have been reported [

1,

2]. Collagens and proteoglycans are the main structural groups, yielding together about 70% of the total body wall composition [

2]. The full composition of the body wall ECM for sea cucumber

Apostichopus japonicus, for which an annotated proteome already exists, has been reported [

3]. The most advanced microscopic analyses of sea cucumber ECM so far have been performed on

Holothuria scabra ([

4],

Apostichopus japonicus [

5],

Holothuria leucospilota and

Stichopus chloronotus [

6]. MCT has inspired the design of different biomimetic (mostly artificial, but biocompatible) materials and medical devices but still lacks deep molecular understanding of the mechanics behind the observed tensile changes in the holothurian body wall [

1].

On the other hand, small sea cucumber derived peptides offer broad functional property range [

7], have well demonstrated ability to self-assemble into larger structures (hydrogels) and are currently being used for the design and construction of specific biological materials - nanostructures, particle carriers, tissue culture scaffolds [

8,

9,

10]. Special research interest has been placed recently on matrikines (MKs) - bioactive molecules with peptide nature, obtained only after proteolytic/ autolytic degradation of the body wall proteins of sea cucumbers [

2]. Most anti-inflammatory MKs have been reported to have low molecular weights (≤ 1000 Da) and were rich in glycine, glutamate and aspartic acid. A recent study in the red sea cucumber

Parastichopus tremulus [

11] has reported antioxidant capacity of peptides obtained after different phases of simulated human digestion

in vitro, but without using a cell culture or tissue model for evaluation of the absorption of nutrients or bioactives.

Bioinformatics and computational (sequence-based molecular docking) methods like AlphaFold 3 [

12] have been increasingly used in the past years, both to model and predict the functionalities of the self-assembled structures, for ligand binding and targeted biodiscovery of novel functional molecules with enhanced bioactivity. A recent publication has focused on the

in-silico analysis of bioactive peptides from underutilized sea cucumber by-products (

Cucumaria frondosa mouth parts and internal organs) [

13]. The PEP-FOLD 3

de novo peptide structure prediction engine [

14], based on a new Hidden Markov Model sub-optimal conformation sampling approach, has shown high capacity to generate 3D structural models for peptides from 5 to 50 amino acids. This capacity of PEP-FOLD3 was already used by Wargasetia and colleagues [

15] for molecular docking and 3D structural estimation of sea cucumber

Cucumaria frondosa peptides’ fitness to block three different proteins important for breast cancer growth. However, experimental proof from a broad range of methodologies is still required to confirm the predictions of machine learning for unstudied organisms, and to enable novel food or biomedical product development.

Our study focuses on experimentally confirming the predicted in silico gelation properties (fibril formation) and bioactivities of four de novo peptide sequences with the highest predicted probability for self-assembly into hydrogels. We have thus, first, obtained the peptides in pure form through a synthetic approach; then, secondly, determined the limiting concentrations of the peptides for gel structure observation by microscopy; and, thirdly, tested the individual and combined peptide bioactivities in vitro, and in Caco-2 cell culture model. To our knowledge, no previous reports have experimentally explored the microscopic structures of peptide hydrogels, derived from the body wall collagen of North Atlantic sea cucumber species P. tremulus.

2. Results and Discussion

The four

de novo peptide sequences, chosen for this work (

Table 1) have already been aligned with existing evolutionarily related sea cucumber (

Apostichopus japonicus) and sea urchin sequences (

Strongylocentrotus purpuratus). Partial similarities have been found with sections from ECM fibrillar proteins [

16]. We started with the hypothesis that if the synthetic peptides, prepared on basis these sequences, could be efficiently combined in a dissolution, they could form fibrillar type, supramolecular structures above a critical concentration and in defined conditions. Additionally, if their expected bioactivity was confirmed, it could be preserved to a certain extent in the hydrogel system and impart increased cell survival support to the corresponding fibrillar structures, if used for scaffolding.

3.1. In Silico Modelling of the Expected 3D Structure of the Peptide Gel in Presence of Chelators

In silico modelling was carried out in conditions of neutral pH with two modelling software applications. Results for the most viable structural interaction models, predicted with the Galaxy Web server software, for all combinations of the selected sea cucumber peptide sequences, are summarized in

Figure 1a. Homomer (protein homo-oligomer structure prediction from a monomer sequence or structure) and heteromer (protein hetero-dimer structure prediction from sequences or structures of subunits) modelling options were tested for all sequence combinations. A fitting template was identified for seven out of all possible homomer peptide combinations and for four out of all heteromeric peptide combinations by the template-based docking (TBD) algorithm. The templates with which homologies were detected belong to sections of the active sites of known enzymes, with special interest in the alignment of combined four peptide sequences to sections of a cyanocobalamin complex, which supports the previously observed metal ion complexation capacity. Highest TBD score was yielded for the homodimeric combination of all peptides (987,30), followed by the heterodimeric structure formed by 1:1:1:1 ratio combination of all four peptide sequences (848,84). The Galaxy Web software did not allow for inclusion of metal chelating ions in the modelling process at the time of accession for our study.

The prediction for the random organization of the peptide complexes and the influence of the Ca

2+ ions on their 3D structure could be modeled by the recently validated for Open Science use AlphaFold 3 software. The result from this modelling effort is shown in

Figure 1B. The model presented in the figure is for a dimeric structure (two copies from each peptide sequence and two calcium ions) and its interface predicted template modeling score (ipTM) is of 0,57 - 0,59, derived from the template alignment measure for the accuracy of the interface predictions in the entire structure [

12]. ipTM values for the complex modelling we applied were below the high confidence threshold (0.8) since the structural information available for the proteins from which the selected peptides were derived was generally very limited. Also, the obtained lower modelling score could be due to the current lack of reliability in the predictions for the flexible regions of proteins in Alpha Fold 3 [

17] and the relatively small sizes of the studied peptides.

3.2. Experimental Solubility and Minimum Gelation Conditions

According to the manufacturer of the four custom peptides, the solubility of peptides with more than 25 % charged residues is expected to be generally good at neutral pH in aqueous systems (rule applying mainly to custom peptide 3, and partially – to peptide 2), while the peptides with sequences containing high or very high hydrophobic residue numbers (over 50 or 75 % of the total number), would have low or no solubility in aqueous buffers (peptides 1 and 4). For these highly hydrophobic peptides, addition of DMSO, acetonitrile or dimethylformamide (DMF) was advised (in a ratio of up to 50 % of the total volume of the solution) even if these agents could damage the residues sensitive to oxidation (C, M, W). These solubility conditions were taking into consideration the degree of purity of the different peptides after HPLC analysis by the producer. Therefore, we used these as basis for selection of the initial conditions in the gelation trials (

Table 2). After making charge calculations based on the sequences of the peptides (considering also the N-terminal acetylation), the net amino acid residues at pH 7 for most of the peptides (1, 3 and 4) corresponded to acidic charges, while peptide 2 was expected to behave with a net basic charge in such conditions. The solubility of the peptides was tested in the two selected neutral buffer systems (with and without Ca

2+ ions, which are normally abundant in sea cucumbers and known previously to cause chelation of sea cucumber peptides [

16,

20].

The individual peptide solubility of peptide 2 (sequence Ac - RAGQPITAFLVRD) was low in both buffers. DMSO had to be added in different concentrations to peptide 1, 2 and 4 solutions, when these were resuspended in the Ca2+ containing buffer (2,5% v/v, 5 % v/v and 2,5 % v/v, correspondingly). After 10 min at room temperature all the separate solutions of peptides 1, 2 and 4 (at 1 mM final concentration) in the Ca2+ containing buffer system formed gels with different optical characteristics: nontransparent, white cream-like gel (peptide 1), nontransparent (whitish yellow) solid gel (peptide 2) and transparent solid gel (peptide 4). Peptide 3 was fully soluble and did not form a gel in these conditions, but only after increasing the peptide concentration to 15 mM. A further targeted optimization of the gelation conditions (e.g. temperature rise, pH shift or higher Ca2+ ion concentrations) would be needed for the separate peptide dissolutions.

In sodium phosphate buffer (NaPB), at pH 7.4, peptides 1, 3 and 4 dissolved after gentle agitation without any need of DMSO addition, with experimentally determined pH 6.5 -7 in the concentration range 1 – 15 mM. Gelation for these three peptides would occur in the tested experimental conditions only at concentrations above 15 mM. P2 was insoluble in this system until initial resuspension in DMSO (for 7,5 % v/v final content), followed by the addition of the aqueous buffer. However, in this case, depending on the concentration of peptide 2, gelation would occur in DMSO during dissolution. The same applied to peptide 4, if initial resuspension in DMSO was attempted, prior to the addition of the phosphate buffer.

Equal ratios of the peptides were tested in the all-peptide mix, based on the results from the

in-silico modeling (section 3.1) and the model presented in

Figure 1, where the structure appears to be stabilized by the complexation of two molecules from each peptide (dimeric structures). The suspension of the mixed peptides was much easier to solubilize in both buffers than that of the individual peptides, not requiring DMSO for gelation in the Ca

2+ containing buffer, which occurred spontaneously after 1 min agitation.

Thus, the minimal gelation conditions for the four-peptide mix were defined as 15 mM peptide concentration, 1:1:1:1 ratio, the presence of Ca

2+ ions. These conditions yielded a solid transparent gel (

supplementary Figure S1), after vortexing at room temperature. The resulting gel was freeze-dried and submitted to Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and other structural analyses. By combining the studied peptides with some of the widely used polysaccharide biopolymers, the gelation conditions can be further optimized, to mimic the known ECM organization in the sea cucumber body wall [

1]. Similar gelation conditions (pH and Ca

2+ concentration dependent) have been also reported for a supramolecular polymer (SP) hydrogels based on sea cucumber dermis [

18] with differential mechanical properties (rigid and stable at pH 3/ high Ca

2+ concentration, or forming soft networks at alkaline pHs in the lack of Ca

2+ ions), which had autolytic capacity at physiological pH.

3.3. Structural Characterization

3.3.1. SEM Analysis

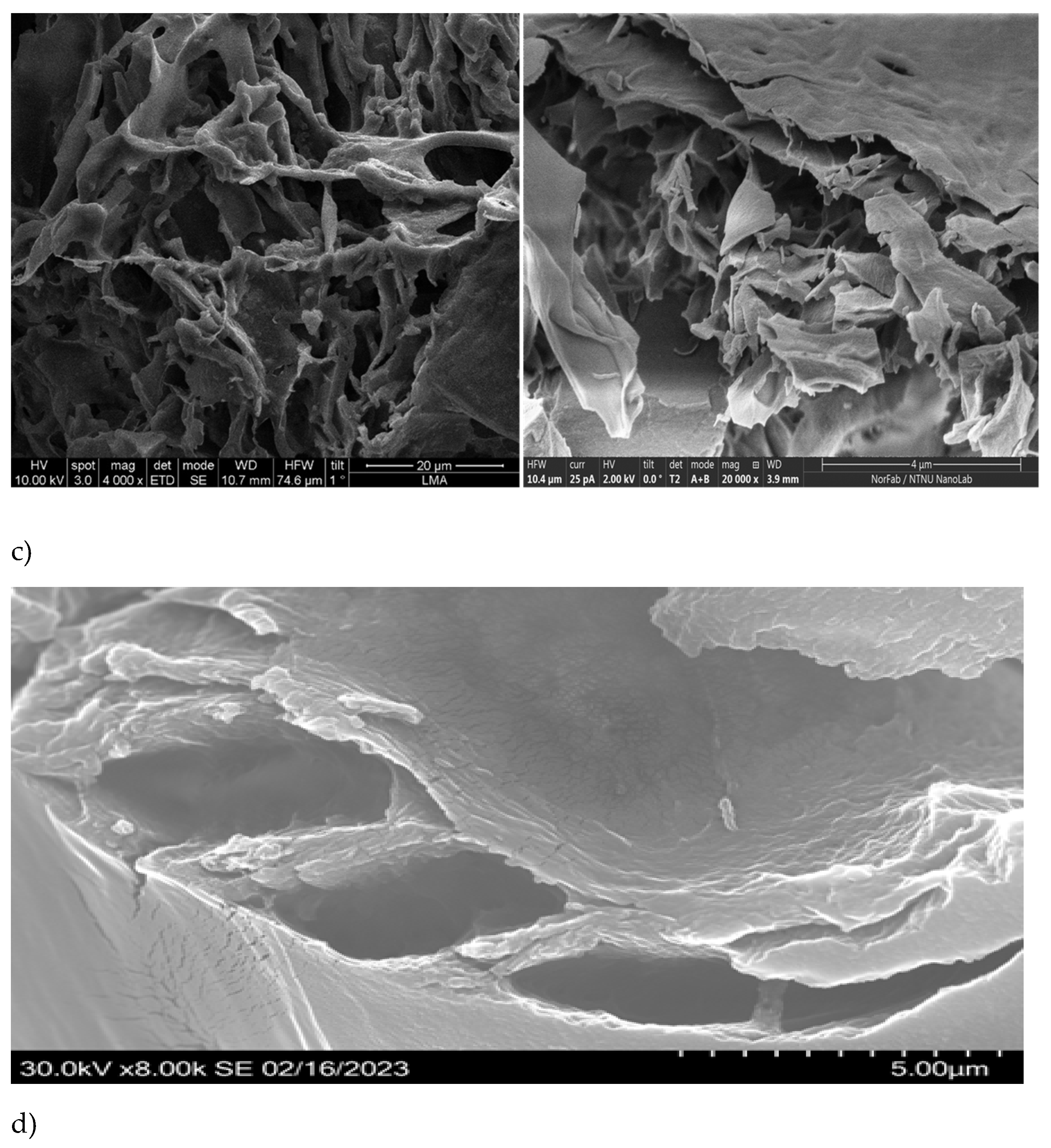

The SEM analysis of the initial (purified by FPLC, bioactive) fraction, isolated by us from sea cucumber hydrolysate, showed particles with variable sizes, ranging between 240 nm and 4.31 μm (

Figure 2a;

Supplementary Table S1) and nonhomologous morphology (amorphous structure). In contrast, the mixture of the four custom synthesized peptides after gelation showed definite fibrous structure (

Figure 2b), which could correspond to the linear complexation of subunits, similar to the model prediction in

Figure 1b. The gel with the four-peptide mixture contained long fibrillar formations with cross section of approx. 2.78 µm and length of 26.95 µm. The smaller particle sizes and forms, observed in the case of the initial complex fraction, isolated from the hydrolyzed sea cucumber biomass by FPLC, could be explained with the lack of fibril formation and the presence of many different peptides which influenced the supramolecular organization during lyophilization.

The particle morphology of each separate peptide gel after lyophilization was quite different (

Figure 2, c to f), although clear laminar organization was appreciated in the microstructure of all peptide gels. The sizes of the particles, formed at the same gelation conditions by the different peptides, were ranging between 4.3 and 17.7 µm length, while their cross section varied between 2.0 and 4.3 µm. Additionally, peptides 1, 2 and 4 showed fiber arrangements into ECM-like structures (

Figure 2, c and f; [

21]). In peptide 3, the arrangements of the particles also mimicked fibrillar structures, while peptide 2 showed non-homogeneous layered organization, similar to epidermal connective tissue in other sea cucumbers (e.g.

H. scabra [

22];

A. japonicus [

23]). The size measurements both for length and cross section (

Table S1) showed statistically significant differences among all samples (single factor ANOVA for cross section with p ≤ 0.008 and for length – with p ≤ 8.7075E-13). Comparison between the particle sizes in the initial FPLC fraction and in all the samples prepared with the synthesized peptides showed significant differences (

Table S1b) while there were no significate differences in the particle cross section (diameter) between the mix of the four peptides and the individual peptide preparations. The lengths of the fiber structures in the samples were significantly different, except in the case of peptides 2, 3 and 4, which showed clustered length size values (

Table S1b). The size of the collagen fibrils in sea cucumbers will generally depend on the state of the connective tissue (stiffened/softened) and on the type of connective tissue, the structure of which varies depending on originating organs and species [

24]. The collagen fibers in the various sea cucumber body wall dermal layers are usually arranged in laminar superstructures, with alternating orientation of the fibrils, so these are seen sometimes as round cross sections and sometimes, as longitudinal views. Such laminar structures have been reported for

Screrodactyla briareus,

Eupentacta quinquesemita or

Holothuria forskali [

25]. Our measurements for the cross-section (diameter) of the fibers, formed in the gel of the four peptides together, show higher values in comparison to the previously reported ones for both stiffened and softened states. For example, in dense connective tissue layers (DCT) in sea cucumber

E. quinquesemita, the collagen fibrils with diameters 20 – 160 nm, organized in small bundles or as single fibrils have been reported [

26]. The collagen fibrils in the loose connective tissue (LCT) of the same species have 40-60 nm diameter. In muscle tendon, the collagen fibrils have diameter of about 30-40 nm and the microfibrils – of 10 to 15 nm. The mean length measured by us in the combined peptide gel, however, is comparable with the TEM-measured collagen fibril length in the body wall of

E. quintesemita [

25].

The morphology of the initial FPLC fraction with multiple peptide composition has clear similarities with that of the sea cucumber powder from

H. scabra, obtained after thermal treatment (10 min at 80 °C) and air-drying [

27]. The microstructures observed by us for the mix of the four synthesized peptides, as well as for peptides 2, 3 and 4 were also similar to the ones obtained by SEM for the collagens from the body wall of sea cucumber

H. scabra (

Figure 3a, [

4]), as well as for the soluble collagen fraction from

A. japonicus body wall (treated by endogenous complex protease) (

Figure 3b, [

28]). Overall similarities can also be observed to the microstructure of the collagen matrix fibrils (collagen bundles under the coelomic epithelium) in sea urchin

Paracentrotus lividus (

Figure 3c, [

29,

30]). Finally, from the microstructural study of the gel, formed by the mixture of the four synthesized peptides (at 15mM and in 1:1 ratio), we see that self-assembly occurs spontaneously and results in tubules, even if the process is apparently random. The possible covalent crosslinking effects of DMSO or methanol (besides the non-covalent interactions introduced by Ca

2+) should not be disregarded but could have contributed to the formed structures only in the case of the individual peptide gels. For the resuspension of the peptides in the four-peptide mix no addition of DMSO or other agents was necessary. Further studies are needed to finetune the conditions for targeted assembly, with controlled structure-function relationships, for example, for 3D printable food bioink development.

3.3.2. UV Spectroscopic Analysis

UV spectroscopy is widely used for the analysis of peptide structures due to the ability of the side chain groups of specific amino acids to absorb UV light in a certain wavelength range. The knowledge of the peptide composition assists the estimation of the expected spectra, although the interactions among the peptides in the solution would also influence the peak of the measured spectra. The luminescent amino acids in proteins are mainly phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan, with the fluorescence peaks at around 282 nm, 303 nm, and 348 nm, respectively [

31]. The sea cucumber peptides presented maximum absorption peaks at wavelengths of 281 nm (P1), 235 nm (P2), 233 nm (P3) and 283 nm (P4), which was aligned with the corresponding fluorescent amino acid composition per peptide. The mix of the four peptides at concentration below the minimum gelation concentration (5 mg/ml) showed similarity with the single peptides in the wavelength range of 233 - 365 nm. However, the maximum absorbance intensity increased slightly in the peptide mixture (recorded peak at 366 nm), which proved that the secondary structure of the peptides had changed due to new bond formation and possible aggregation interactions. The region of the UV spectrum of 200 -230 nm is known to be related to peptide bonds, while the higher wavelengths are related more to the aromatic regions of the amino acids and intermolecular hydrogen bond complexation (310 nm and above) [

31].

3.4. Experimentally Determined Bioactivities

The synthetic peptides are expected to have a significant physiological role in any supramolecular constructs for enhanced cell viability or food hydrocolloid systems, and thus, their bioactivity required further screening. Based on the predicted bioactivity types for the peptide sequences and the previous antioxidant activity results in the complex FPLC fraction from P. tremulus hydrolysate, we have screened for antioxidant and Angiotensin-I converting enzyme-inhibitory activities in vitro.

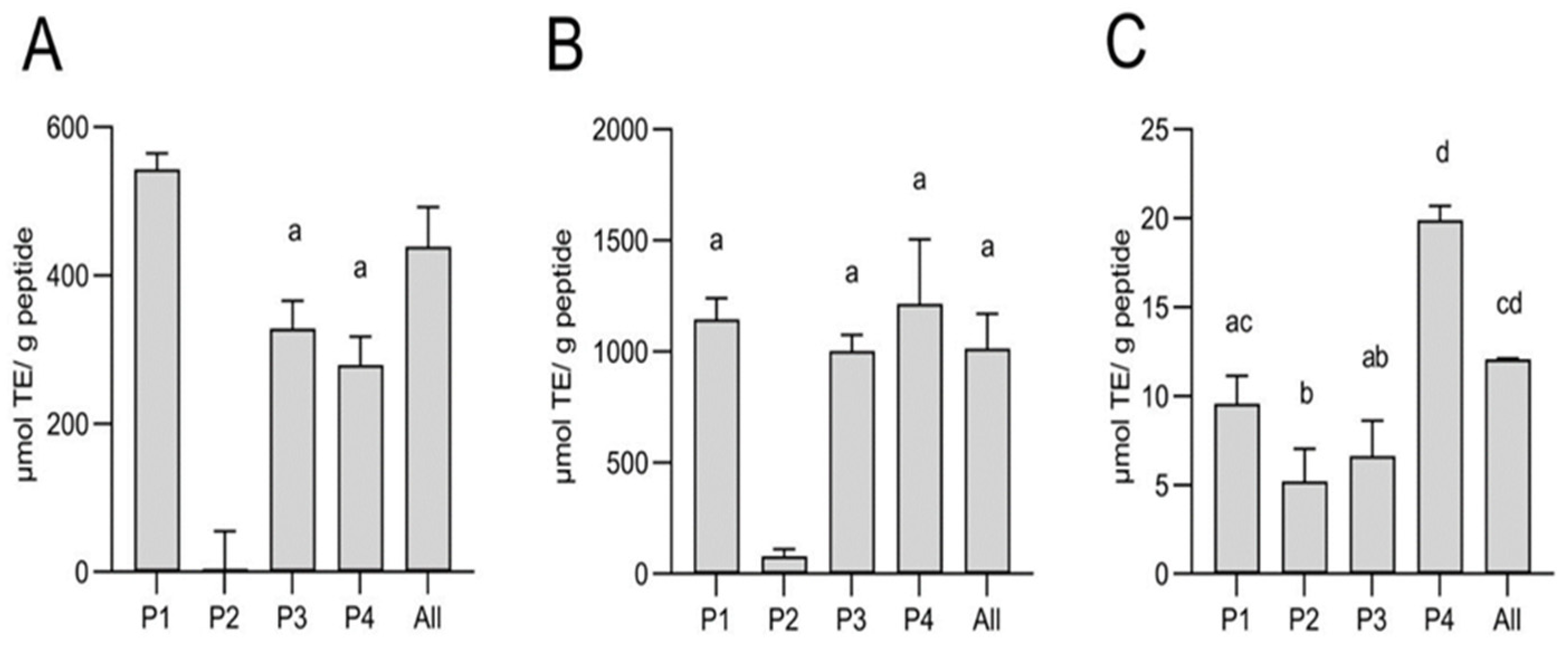

3.4.1. Measurement of the Antioxidant Capacity

In the ORAC assay, all peptides except peptide 2 showed antioxidative capacity, which was significantly higher for P1 with 543 µmol TE/g protein and comparable for P3 and P4 (328.5 and 279 µmol TE/g protein, respectively) (

Figure 4 A). For P2, which was dissolved in DMSO due to insolubility in the aqueous ORAC buffer, no activity could be detected at the necessary dilution to overcome interference of DMSO in the assay. The activity observed for P1, P3 and P4 at this concentration is much less than previously reported for the initial

P. tremulus hydrolysate (up to 791 μmol TE/μg protein) and derived FLPC fractions (about 400 μmol TE/mg protein) [

16]. Peptide fractions from

A. japonicus selected for high antioxidative capacity have been reported with ORAC values of 17.48 μmol TE/mg peptides [

32]. It must be noted that the synthesized peptides were primarily chosen for our study due to their prediction of high self-assembling capacity rather than for their bioactivities. The antioxidative capacity assessed by ABTS assay was similar for P1, P3 and P4 with 1003 - 1215 µmol TE/g protein. The activity of P2 was significantly lower, with 80.4 µmol TE/g, which could again be due to solubility differences (

Figure 4 B). Overall activity was lowest in the DPPH assay, ranging from 5.2 to 19.9 µmol TE/g for all peptides, with P4 having significantly higher activity. There was no synergistic effect detected in the combination of all peptides in any of the tested antioxidant assays. The observed lack of synergy among the peptides in the mixture could be partially explained by the observed solubility differences among the peptides in the buffered systems, used for in vitro antioxidant activity evaluation. On the other hand, the expected interactions among the peptides in the solutions (even if not at minimal gelation concentration) could also be responsible for the bioactivity reduction. Structural reassembly and blocking of bioactivity responsible molecular sections during protein-protein interactions at physiological conditions is well-documented [

33].

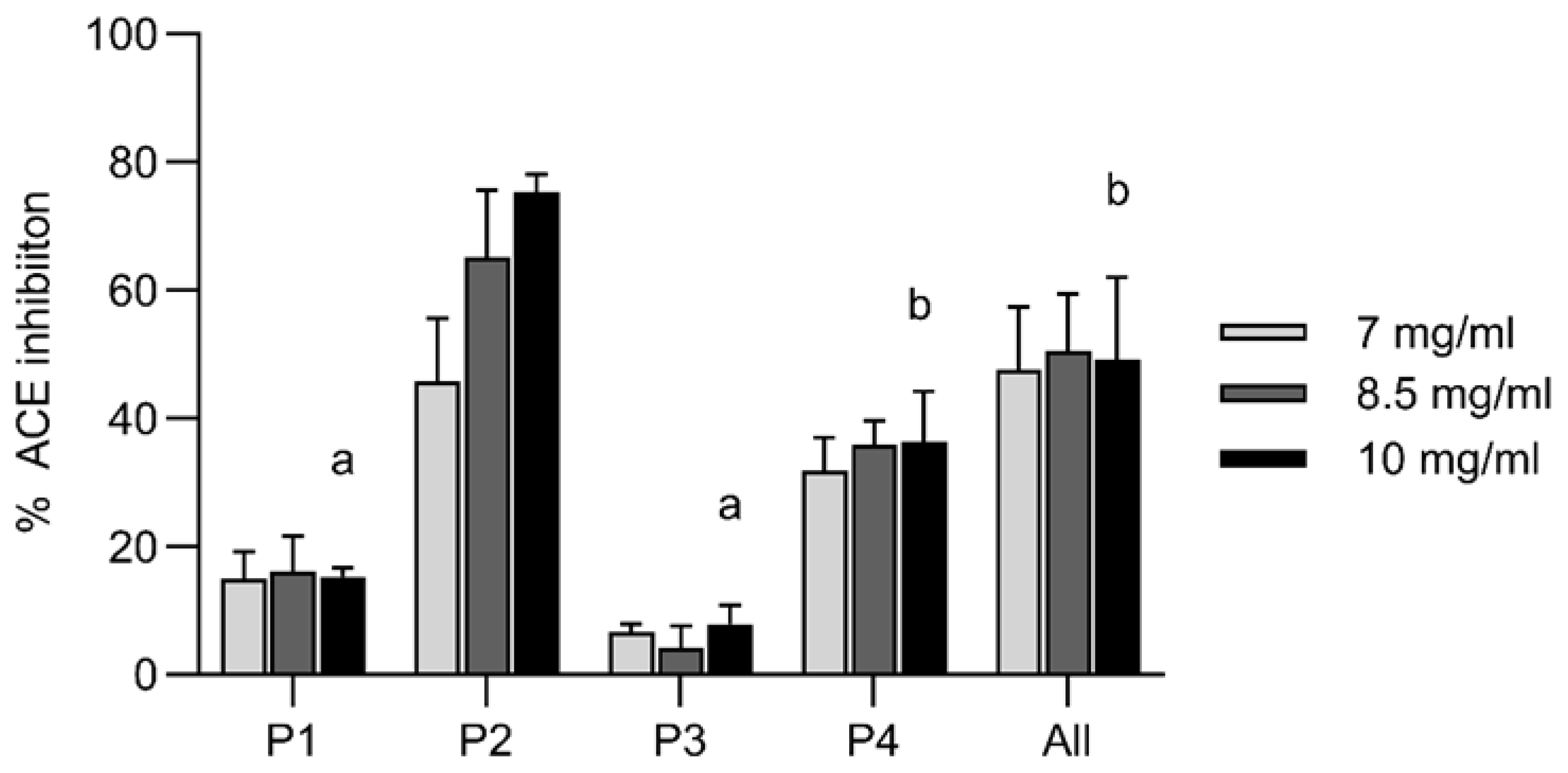

3.4.2. Measurement of the Angiotensin-I Converting Enzyme-Inhibitory Capacity

In silico modelling had also predicted anti-hypertensive activity of the synthesized peptides, which was experimentally assessed as their ability to inhibit the ACE I-catalyzed cleavage of the substrate FA-PGG. Only for P2 and P4 a positive linear regression line could be obtained based on their ACE I inhibition (%) at the assessed concentrations. Their IC 50 values were calculated as 7.1 ± 0.8 mg/ml (4.5 ± 0.5 mM) and 26.3 ± 20.0 mg/ml (8.57 ± 6.5 mM), respectively (

Figure 5 A). P2 showed by far the strongest ACE I inhibition with 75 % at 10 mg/ml (

Figure 5 B). This ACE I inhibition is slightly weaker than the reported for a

C. frondosa body wall hydrolysate with IC50 of 1.66 mg/ml [

13] or a

Holothuria atra hydrolysate with IC50 of 0.32 mg/ml [

34]. An isolated peptide from hydrolysed

A. japonicus gonads has shown ACE I inhibition with an IC50 of 260.2 ± 3.7 μM [

35] and an isolated Angiotensin-I converting enzyme-inhibitory peptide from

Acaudina molpadioidea gelatin had an IC50 of 14.2 µg/ml [

36]. Although there was no synergistic effect of the combination of all peptides seen in the bioactivity assays, their combination is still interesting in terms of their complementary behavior. Likewise, the peptide P2 with the overall lowest antioxidative capacity in the tested systems, had the highest anti-hypertensive activity. It has still to be considered that all of these

in vitro assessments have a rather low correlation to assessment in actual cell cultures

in vitro or

in vivo [

37]. Also, a protective matrix might be needed if these effects are intended to be preserved in food applications. On the other hand, it has been shown that antioxidative capacities might increase during digestion and fermentation [

38,

39]. Thus, it could be interesting to further assess the bioactivities from peptide fragments after simulated human digestion, which might also be released in such conditions from the derived gel structures of a food product [

11].

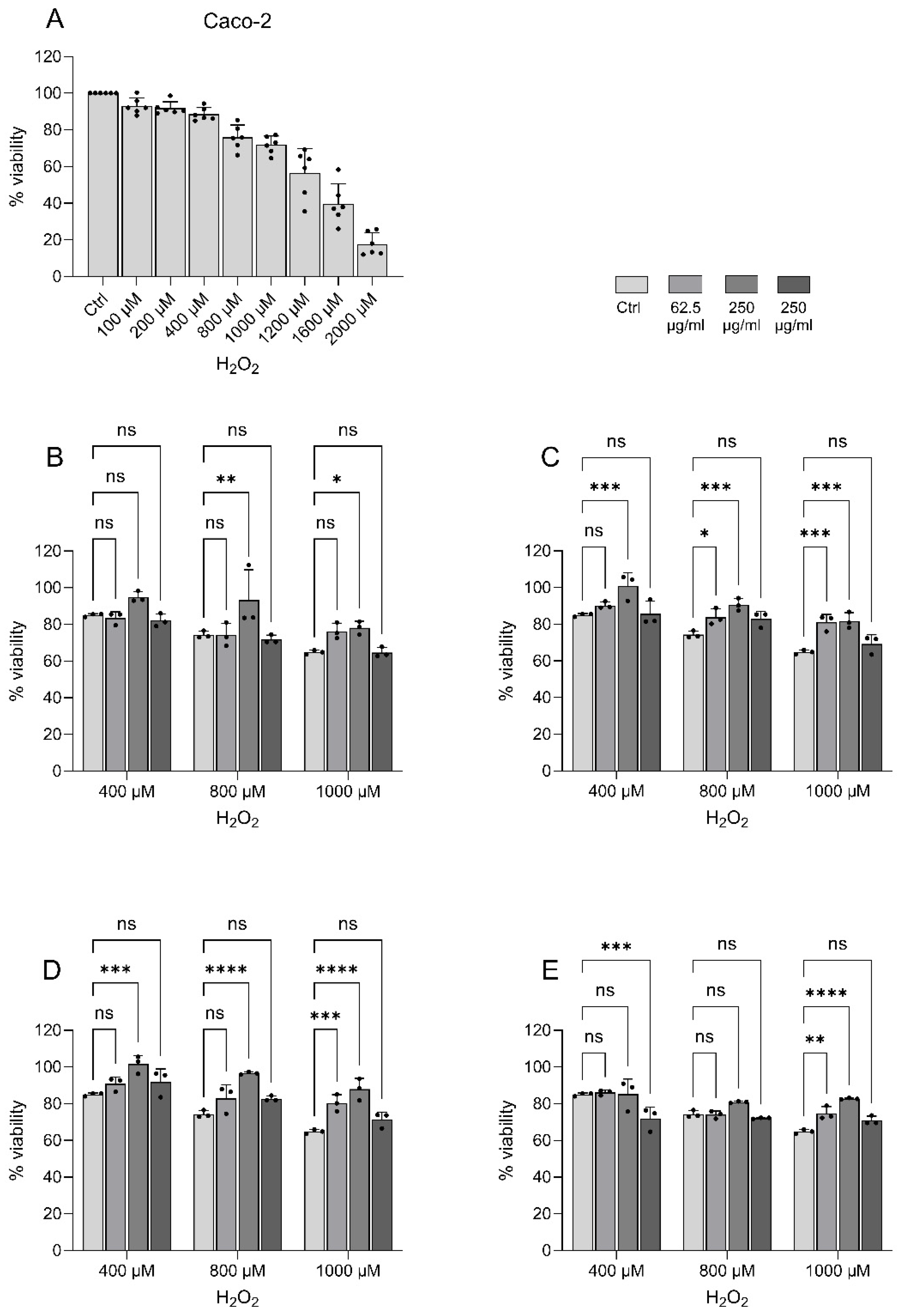

3.4.3. Oxidative Stress Protection Capacity Testing in a Caco-2 Cell Culture Model

The capacity of the peptides from

P. tremulus to protect from oxidative stress-induced cell death was evaluated in H

2O

2-stimulated Caco-2 cells. First, different concentrations of H

2O

2 (100 µM - 2000 µM) were added to the cells for 20 hours prior to cell viability analysis to determine at which concentration the hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death is evident. The optimal range was found to be between 400 µM and 1000 µM (

Figure 6A) and was used in the successive experiments. All the peptides protected the cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death compared to cells treated with H

2O

2 alone (

Figure 6B-E). For all the peptides, 250 µg/ml was the concentration that had the highest overall protective effect against H

2O

2-induced oxidative stress. For peptide 3, a dose-dependent protective effect was observed in the cells treated with 1000 µM H

2O

2, where 250 µg/ml of P3 yielded a stronger protective effect than 62.5 µg/ml of peptide 3. Of note, P2 (as noted previously) and P4 were dissolved in DMSO due to insolubility in the aqueous cell culture medium. DMSO alone without peptides were tested to rule out the possible antioxidant effect of DMSO (data not shown). Overall, these experiments demonstrate a significant oxidative stress protection capacity of all the tested peptides despite not being chosen for their bioactivities. This is in line with other studies performed in Caco-2 cells demonstrating bioactive peptides with antioxidant activity and oxidative stress protection capacity [

40].

Modelling of secondary and tertiary protein structures is considered more accurate if based on experimentally confirmed molecular templates,

e.g. the ones obtained from crystallography, X-Ray diffraction, Electron Microscopy (EM), Small-Angle Scattering (SAS), solid-state Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) or 3D Fourier transform spectroscopy [

18,

19]. However, such detailed structural information is usually obtained after complex analytical studies, which are not available for most proteins from generally understudied organisms. As an example, in the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB) and the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB) archive, there are currently deposited only 16 experimental structures of proteins derived from holothurians, 6 for proteins from sea urchin

Paracentrotus lividus and 13 – for those from

Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, compared to a really high number of proteins derived from

Homo sapiens or bacteria (statistics accessed in November 2023). Interestingly, no homologies were automatically detected by the used-by-us web-based software tools with the known structures in related marine echinoderm species. Since there is a lack of publicly available biological information at molecular level for sea cucumber

P. tremulus, we selected the ones derived from the highest TBD score models as the most probable interactions, i.e. the homo- & heteromer complexes to be formed by all peptides in 1:1:1:1 ratio combination. These interaction models were further used as basis for the preparation of gels (section 3.2) and their further structural analysis by SEM.

4. Conclusions

This study has advanced further the knowledge on marine natural peptide-based hydrogels, which could have potential for upscaling to food or pharmaceutical product development. As initial steps of the hydrogel structural characterization, we have microscopically confirmed the formation of fibrillar/ laminar structures by the mixture of four peptides from sea cucumber P. tremulus body wall. This is the first report providing experimental data on these four P. tremulus peptides, which could be successfully biosynthesized, were stable for up to one year in frozen conditions and could self-form (separately or in a mixture of four) gel structures. No application of additional treatment or incorporation of high concentrations of chemicals was proven necessary. We have established some critical gelation conditions such as minimal peptide concentrations, presence of ligands, and have experimentally confirmed some of the bioactivities of the peptides in vitro, on a human intestinal epithelium cell culture. More research is needed to define the exact calcium binding capacity of each peptide and the structures of the formed multimeric complexes, the necessary modifications to allow for controlled physico-mechanical properties (depending on the sought-after application), or the bioavailability of the different possible peptide complexes for food hydrocolloid formulations. Potential de novo allergenicity of the sea cucumber peptide-based hydrogels should also be studied in the future.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Peptide Synthesis

The four peptide sequences from sea cucumber

P. tremulus selected for custom synthesis are presented in

Table 1. The peptide synthesis was carried out by ProteoGenix SAS, followed by acetate N-terminal blocking and chromatography purification (LC-MS purity chromatograms per peptide are included in the supplementary materials). Thus, 1 g lyophilized powder at 80 % or higher purity (technical grade) in sterile plastic bottles was provided by ProteoGenix for further research. The peptides were stored at -20 °C, opened only prior to dissolution preparation and used within 2 years from the date of provision. The accompanying manufacturer information advised resuspension with DMSO for peptides 1 and 4, due to poor water solubility.

5.2. Molecular Structure Modelling of the Peptide Complexes

Three different web-based software solutions were initially compared for structure folding prediction of the complexes to be formed in solution among the studied peptide sequences, at neutral pH. The peptide sequences were thus analyzed with the GalaxyHomomer/ GalaxyHeteromer services of GalaxyWEB (accessed in October 2022 and June 2023;

https://galaxy.seoklab.org, [

14]), the MOLSOFT LLC ICM-Browser v.3.9 (

https://www.molsoft.com/icm_browser.html; accessed last in October 2023 [

41]) and the Alpha Fold 3.0 (

https://alphafoldserver.com, accessed on 27/10/2024 [

12]). Structural visualization was first done through Galaxy and MOLSOFT. Prediction quality assessment for further model selection was done on basis of average cluster size, TongDock/DockQ-score or lowest stabilization energy index (sOPEP), through long-range stabilized amino acid interactions [

14,

42]. Only the top-highest score or first clustering option from each prediction case was thus taken into further account. The predicted 2D and 3D structural models were compared among different software tools, on the basis of their scores. Individual peptide charges were calculated by Pep-Calc.com’s online Peptide Calculator [

43] and compared with the previously obtained most probable Mass Spectrometry ion peaks [

16]. Most probable structures from Galaxy/ MOLSOFT (in the lack of stabilizing external compounds or metal ions) were summarized and compared with the prediction of the AlphaFold 3 modelling software.

5.3. Establishing Minimal Gelation Conditions

For the gelation study, dissolution was tested in modified artificial sea water with pH 7.74 (composition as per [

44], all salts at “for analysis” grade, from Merck Sigma), due to its content of Ca

2+ ions (final concentration in the buffer is 11 mM; Ca

2+ previously established as key gelation factor [

16]) and its closeness to the native physico-chemical environment of the sea cucumber body wall proteins. Also, due to preference for aqueous buffer systems for bioactivity testing (section 5.5) and comments from the custom peptide producer, the solubility of the peptides was checked in 75 mM sodium phosphate buffer (NaPB), pH 7.4. All buffers were autoclaved for 20 min at 120 °C, in a VAPOUR-LINE Lite autoclave (VWR Chemicals International), prior to use. A range of concentrations of the peptides between 1.5 and 30 mM was tested for establishing minimal gelation concentrations, for each of the peptides, and in a combination of all four (1:1:1:1 ratio). DMSO (Sigma Aldrich, D8418) was used for better solubilization and effect upon gelation. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (21 °C), in three repetitions. Optical solution (sol)-gel transitions were observed and documented. The resulting gels were further freeze-dried in a Labconco FreeZone 12 Liter equipment and submitted to SEM analysis as per the protocols detailed in the next section of this methodology.

5.4. Structural Characterization of Sea Cucumber Peptide Gels

5.4.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy Analyses

The initial peptide fraction from

P. tremulus hydrolysate after FPLC purification [

16], was freeze-dried and used as control for Cryo-Scanning Electron Microscopy (cryo-SEM) analysis on FEI Quanta FEG 250 equipment (FEI Europe, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at the Laboratory of Advanced Microscopy, University of Zaragoza, Spain. The mixture of the four custom synthesized peptides, selected for this study, at ratio 1:1, was prepared at minimal gelation conditions (15 mM final concentration, in presence of 11 mM Ca

2+ ions) and then lyophilized. This mixed peptide fraction was analyzed with the same SEM equipment, after palladium coating. Image J software [

45] was used in parallel with the SEM analysis software, for measurement of the particle sizes on all micrographs.

The solutions of the individual peptides (at 15 mM final concentration, in Ca2+ containing buffer, with addition of DMSO for improved solubility were prepared and then freeze dried. SEM analysis of these samples was done at the NTNU NanoFab facility, Trondheim, Norway, on a FEI Apreo Field Emission equipment, after coating with gold. Image J was used in parallel with the SEM equipment software’s measurements, for determination of the particle sizes on all micrographs.

5.4.2. Ultraviolet–Visible (UV) Absorption Spectrum of the Gel

The four sea cucumber peptides, separately and as a mixture of all four in 1:1:1:1 ratio, were suspended in artificial sea water (VWR, pH 8) at 5 mg/mL final concentration. The UV absorption spectroscopy of the samples was scanned with ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-Vis spectrophotometer UV Mini 1240) in the wavelength range of 190-400 nm, with artificial marine water (VWR) used as a blank for background adjustment. The corresponding peaks were recorded in the equipment and used for further comparison and analysis.

5.5. Experimental Bioactivity Confirmation

5.5.1. Antioxidant Capacity

ORAC assay was performed according to the BioTek Application Note [

46]. The peptides were initially dissolved at 10 mg/ml in three separate replicates. According to their solubility, peptides P1 and P3 were dissolved in 75 mM NaPB, pH 7.4, whereas P2 was dissolved in 100 % DMSO and P4 in 30 % DMSO in NaPB. For the combination of all peptides, equal molar amounts were combined, resulting in a final concentration of 0.96 mM of each peptide. The peptides were further diluted 1:100 in NaPB. Trolox® (6-hydroxy-2, 5, 7, 8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) (Sigma Aldrich #238813) standards (100–6.25 µM), Sodium fluorescein (SoF, Sigma Aldrich #F6377) working solution at 0.04 µM and AAPH (2,2′ -azobis (2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (Sigma Aldrich #440914) at 153 mM were prepared in NaPB. In a black microplate, 25 μl of standards, samples or blanks, and 150 μl SoF working solution were incubated at 37 ◦C for 30 min in the dark, followed by the addition of 25 μl AAPH solution and fluorescence measurements (485/20 ex., 528/20 em.) at 37 ◦C every 10 min for a total of 60 min in a Synergy HTX S1LFA plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Agilent Technologies, USA). Antioxidative activity was calculated as Trolox equivalents (TE) according to a standard curve based on the area under the curve (AUC). AUC values were calculated by the following formula and AUC values from blank measurements for each buffer were subtracted:

AUC = 0.5 + (R2/R1) + (R3/R1) + (R4/R1) + … + 0.5*(Rn/R1), where R1 is the first and Rn is the last fluorescence reading.

For ABTS assay [

47], the initial peptide solutions at 10 mg/ml as described for ORAC assay were further diluted 1:100 in 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS). 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS salt; Sigma Aldrich A1888) and potassium persulfate (K2S2O8; Sigma Aldrich 379824) were dissolved at 7 mM and 2.44 mM respectively in 50 ml 0.01 M PBS at room temperature in the dark for 16 – 24 h. The formed ABTS•+ radical was diluted with PBS to an absorbance of 0.7 ± 0.05 at 734 nm in a Synergy HTX S1LFA plate reader. Trolox was prepared at 1 mM in PBS and diluted to 300, 250, 200, 150, 100, 50, 20 µM for the standard curve. 10 µl of all samples and 190 µl of ABTS•+ working solution were combined and absorbance at 734 nm measured after 30 min. The activity of the samples was calculated as TE based on the standard curve.

For DPPH assay (according to [

48]) all four peptides were dissolved in three independent replicates at 10 mg/ml in DMSO and combined at 0.96 mM of each peptide as described for ORAC assay. 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, Sigma Aldrich D9132) was dissolved at 0.15 mM in methanol. Trolox was chosen as standard in similarity to the assessment of peptide samples and prepared at 100 mM in 75mM NaPB and further diluted to 300, 250, 200, 150, 100, 50, 20 µM in dH2O for the standard curve. The peptide solutions were assessed as 2-times dilutions in dH2O and 20 µl of all samples was combined with 180 μl of the 0.15 mM DPPH working solution, incubated for 30 min in the dark at room temperature and absorbance was measured at 540 nm in a Synergy HTX S1LFA plate reader. The activity of the peptides was calculated as TE based on the standard curve.

5.5.2. Angiotensin-I Converting Enzyme-Inhibitory Activity Measurement

For Angiotensin-I converting enzyme (ACE I)-inhibitory activity measurements the peptides were dissolved as described for ORAC assay [

49]. As the highest possible concentration of the peptides without gel formation was 10 mg/ml and no activity could be detected at 5 mg/ml, the peptides were assessed at 7, 8.5 and 10 mg/ml in three independent replicates. The substrate N-[3-(2-furyl) acryloyl]-L-phenylalanyl- glycylglycine (FA-PGG; Sigma Aldrich F7131) was prepared at 0.88 mM in 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5 and 0.3 M NaCl. In 96-well plates, 10 µl of the samples and their respective buffers as control were combined with 10 µl of ACE I, (ACE; Sigma Aldrich A6778) at 0.25 U/ml and 150 µl preheated substrate solution. Absorbance was continuously measured every minute at 340 nm for 30 min in a Synergy HTX S1LFA plate reader. Linear regression curves were obtained for the decrease in absorbance over time for every sample and % ACE I inhibition was calculated as:

% ACE I inhibition = (1 – (ΔA340 nm protein solution /ΔA340 nm negative control)) *100

Captopril was used to verify the functionality of the assay and a logarithmic inhibition curve was obtained by 340, 34, 17, 8.5 µM Captopril. IC 50 values were calculated for the peptides for which a positive linear regression line could be obtained based on their ACE inhibition (%) at the assessed concentrations.

5.5.3. Oxidative Stress Protection Capacity Testing in a Caco-2 Cell Culture Model

Cells of the human colon adenocarcinoma cell line Caco-2 were obtained from the American Type Cell Culture Collection (ATCC) and used for the testing of the protection capacity of the sea cucumber peptides against oxidative stress generated by hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) [

40]. Caco-2 cells were maintained in complete medium; Eagle’s medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100U penicillin+100µg streptomycin (Sigma), 1mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma) and 1x non-essential amino acids (Gibco) and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO

2. The cells were passaged every 3rd day.

For experiments, the concentration of Caco-2 cells was adjusted to 1×104 cells/mL in complete medium, seeded into 96-well plates with 100 µl per well, and cultured in high humidity at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The following day, cells were pre-protected with different concentrations of the sea cucumber peptides at concentrations 62.5, 250, and 1000 µg/ml diluted in complete medium for 24 hrs. Peptide 2 and 4 were dissolved in 100 % DMSO prior to further dilution in complete medium. Thereafter, different concentrations of H2O2 were tested (in the range 100, 200, 400, 800, 1000, 1200, 1600, and 2000 µM) for 20 hrs, and cell viability was determined at all these conditions, compared to non-treated Caco-2 cells. Cell viability was determined by the Presto Blue assay (Thermo Fischer Scientific), as per the instructions of the manufacturer. Absorbance was measured at 570 and 600 nm.

5.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism Software v.9.5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., Ca, USA), as well as using the Excel Stat data analysis tools of Microsoft Excel® for Microsoft 365. Results are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation if nothing else is stated. Differences were tested with ordinary one-way ANOVA, followed by t-test and/or Holm-Šídák method for multiple comparisons. Superscripts were generated by the online tool by Gerard E. Dallal Copyright © 2001.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: The gel formed by the combination of the four peptides at 15mM concentration and in presence of Ca2+ ions, at room temperature; Table S1: Summary of the size measurements done by SEM microscopy software and ImageJ on at least 5 photos per sample, with at least 5 measurements per photo for both parameters’ length and cross section..

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A..; methodology, M.A., J.M. and M.D.H.; validation, all authors.; formal analysis, M.A., J.M. and M.D.H.; investigation, M.A., J.M. and M.D.H.; resources, M.A.; data curation, J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A., J.M. and M.D.H..; writing—critical review and editing, T.T..; visualization, all authors.; supervision and project administration, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The experimental work carried out by us was kindly supported through an internal Møreforsking competence development grant [project 55013/2022]. The authors acknowledge the use of instrumentation as well as the technical advice provided by the National Facility ELECMI ICTS node "Laboratorio de Microscopías Avanzadas" at the University of Zaragoza, Spain for the SEM imaging of the initial FPLC fraction and of the mixed four-peptide sample from P. tremulus. The authors also acknowledge the use of the instrumentation as well as the technical support provided by the researchers at the Nanotechnology Laboratory of the Norwegian Technical University (NTNU) in Trondheim, Norway (special thanks goes to Jens Høvik and Jakob Vinje), for the SEM analysis of the gel samples from the individual peptides from P. tremulus.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided upon requirement.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Candia Carnevali, M.D.; Sugni, M.; Bonasoro, F.; Wilkie, I.C. Mutable Collagenous Tissue: A Concept Generator for Biomimetic Materials and Devices. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 37. [CrossRef]

- Popov A, Kozlovskaya E, Rutckova T, Styshova O, Makhankov V, Vakhrushev A, Hushpulian D, Gazaryan I, Son O, Tekutyeva L. Matrikines of Sea Cucumbers: Structure, Biological Activity and Mechanisms of Action. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Nov 10;25(22):12068. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Tian M, Chang Y, Xue C, Li Z. Investigation of structural proteins in sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) body wall. Sci Rep. 2020 Oct 30;10(1):18744. [CrossRef]

- Saallah, S.; Roslan, J.; Julius, F.S.; Saallah, S.; Mohamad Razali, U.H.; Pindi, W.; Sulaiman, M.R.; Pa’ee, K.F.; Mustapa Kamal, S.M. Comparative Study of The Yield and Physicochemical Properties of Collagen from Sea Cucumber (Holothuria scabra), Obtained through Dialysis and the Ultrafiltration Membrane. Molecules 2021, 26, 2564. [CrossRef]

- Long-Jie Yan, Le-Chang Sun, Kai-Yuan Cao, Yu-Lei Chen, Ling-Jing Zhang, Guang-Ming Liu, Tengchuan Jin, Min-Jie Cao. Type I collagen from sea cucumber (Stichopus japonicus) and the role of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in autolysis, Food Bioscience, Vol. 41, 2021, 100959. [CrossRef]

- Bonneel, M., Hennebert, E., Aranko, A.S., Hwang, D.S., Lefevre, M., Pommier, V., Wattiez, R., Delroisse, J., Flammang, P. Molecular mechanisms mediating stiffening in the mechanically adaptable connective tissues of sea cucumbers, Matrix Biology, Vol. 108, 2022, pp. 39-54. [CrossRef]

- Man, J., Abd El-Aty, A. M., Wang, Z., & Tan, M. (2023). Recent advances in sea cucumber peptide: Production, bioactive properties, and prospects. Food Frontiers, 4, 131–163. [CrossRef]

- Xu Z, Han S, Guan S, Zhang R, Chen H, Zhang L, Han L, Tan Z, Du M, Li T. Preparation, design, identification and application of self-assembly peptides from seafood: A review. Food Chem X. 2024 Jun 14;23:101557. [CrossRef]

- Cui, P., Lin, S., Han, W., Jiang, P., Zhu, B., Sun, N., 2019. Calcium delivery system assembled by a nanostructured peptide derived from the sea cucumber ovum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67 (44), 12283–12292.

- Nie, C., Zou, Y., Liao, S., Gao, Q., Li, Q., Peptides as carriers of active ingredients. Review Article. Current Res Food Sci, 2023, Vol. 7: 100592. [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.T.; Kletthagen, M.C.; Elvevoll, E.O.; Falch, E.; Jensen, I.-J. Simulated Digestion of Red Sea Cucumber (Parastichopus tremulus): A Study of Protein Quality and Antioxidant Activity. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3267. [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J., Adler, J., Dunger, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Senadheera, T. R. L., Hossain, A., Dave, D., & Shahidi, F. (2023). Antioxidant and ACE-Inhibitory Activity of Protein Hydrolysates Produced from Atlantic Sea Cucumber (Cucumaria frondosa). Molecules 2023, Vol. 28, Page 5263, 28(13), 5263. [CrossRef]

- Lamiable A, Thévenet P, Rey J, Vavrusa M, Derreumaux P, Tufféry P. PEP-FOLD3: faster de novo structure prediction for linear peptides in solution and in complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 Jul 8;44(W1):W449-54. [CrossRef]

- Wargasetia TL, Ratnawati H, Widodo N, Widyananda MH. (2021) Bioinformatics Study of Sea Cucumber Peptides as Antibreast Cancer Through Inhibiting the Activity of Overexpressed Protein (EGFR, PI3K, AKT1, and CDK4). Cancer Informatics, Vol. 20, pp. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Mildenberger, J., Remm, M., Atanassova, M. (2021) Self-assembly potential of bioactive peptides from Norwegian sea cucumber Parastichopus tremulus for development of functional hydrogels. LWT, Vol. 148, 111678. [CrossRef]

- Wee, J. and Wei, G.W. Evaluation of AlphaFold 3’s Protein–Protein Complexes for Predicting Binding Free Energy Changes upon Mutation. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2024 64 (16), 6676-6683. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F., Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Xu, B., Cao, Z., Liu, W. (2016) Sea Cucumber-Inspired Autolytic Hydrogels Exhibiting Tunable High Mechanical Performances, Repairability, and Reusability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 14, 8956–8966. [CrossRef]

- Prior C, Davies OR, Bruce D, Pohl E. Obtaining Tertiary Protein Structures by the ab Initio Interpretation of Small Angle X-ray Scattering Data. J Chem Theory Comput. 2020 Mar 10;16(3):1985-2001. [CrossRef]

- Sun,N.,Cui,P.,Lin,S.,Yu,C.,Tang,Y.,Wei,Y.,&Wu,H.(2017).Characterization of sea cucumber (Stichopus japonicus) ovum hydrolysates: Calcium chelation, solubility and absorption into intestinal epithelial cells. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, Vol. 97 (No. 13), pp. 4604–4611. [CrossRef]

- Pace CN, Fu H, Lee Fryar K, Landua J, Trevino SR, Schell D, Thurlkill RL, Imura S, Scholtz JM, Gajiwala K, Sevcik J, Urbanikova L, Myers JK, Takano K, Hebert EJ, Shirley BA, Grimsley GR. Contribution of hydrogen bonds to protein stability. Protein Sci. 2014 May;23(5):652-61. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.M. (2019) Collagen of extracellular matrix from marine invertebrates and its medical applications. Review. Marine Drugs, Vol. 17 (2), 118. [CrossRef]

- Delroisse, J., Van Wayneberghe, K., Flammang, P. et al. Epidemiology of a SKin Ulceration Disease (SKUD) in the sea cucumber Holothuria scabra with a review on the SKUDs in Holothuroidea (Echinodermata). Sci Rep 10, 22150 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Tian, M., Chang, Y. et al. (2020) Investigation of structural proteins in sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) body wall. Sci Rep 10, 18744. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M. (2024) Chapter 19 - Autotomy, evisceration, and regeneration in dendrochirotid holothuroids. Editor(s): Annie Mercier, Jean-François Hamel, Andrew D. Suhrbier, Christopher M. Pearce, The World of Sea Cucumbers, Academic Press, pp. 309-327, ISBN 9780323953771. [CrossRef]

- Byrne M. Morphological, Physiological and Mechanical Features of the Mutable Collagenous Tissues Associated with Autotomy and Evisceration in Dendrochirotid Holothuroids. Mar Drugs. 2023 Feb 21;21(3):134. [CrossRef]

- Bonneel, M., Hennebert, E., Byrne, M., Flammang, P. (2024) Chapter 36 - Mutable collagenous tissues in sea cucumbers. In: The World of Sea Cucumbers. Editor(s): Annie Mercier, Jean-François Hamel, Andrew D. Suhrbier, Christopher M. Pearce, Academic Press, pp. 573-584. [CrossRef]

- Ansharullah, A, Tamarin, A., Patadjai, B., Asranuddin (2020) Powder production of sea cucumber (Holothuria scabra): effect of processing methods on the antioxidant activities and physico-chemical characteristics. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 443: 012024. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-q., Liu, Y.-x., Zhou, D.-y., Liu, X.-y., Dong, X.-p., Li, D.-m. and Shahidi, F. (2019), The role of matrix metalloprotease (MMP) to the autolysis of sea cucumber (Stichopus japonicus). J. Sci. Food Agric., 99: 5752-5759. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro AR, Barbaglio A, Benedetto CD, Ribeiro CC, Wilkie IC, Carnevali MDC, et al. (2011) New Insights into Mutable Collagenous Tissue: Correlations between the Microstructure and Mechanical State of a Sea-Urchin Ligament. PLoS ONE 6(9): e24822. [CrossRef]

- Ferrario C, Leggio L, Leone R, Di Benedetto C, Guidetti L, Coccè V, Ascagni M, Bonasoro F, La Porta CAM, Candia Carnevali MD, Sugni M. Marine-derived collagen biomaterials from echinoderm connective tissues. Mar Environ Res. 2017 Jul;128:46-57. [CrossRef]

- Lavrinenko, I.A., Holyavka, M.G., Chernov, V.E., Artyukhov, V.G. Second derivative analysis of synthesized spectra for resolution and identification of overlapped absorption bands of amino acid residues in proteins: Bromelain and ficin spectra in the 240–320 nm range. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, Vol. 27, 2020, 117722. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X., Yao, M., Lu, J.H., Wang, Y., Yin, X., Liang, M., Yuan, E., Ren, J. Identification of novel oligopeptides from the simulated digestion of sea cucumber (Stichopus japonicus) to alleviate Aβ aggregation progression. Journal of Functional Foods, Vol. 60, 2019, 103412. [CrossRef]

- Purohit, K.; Reddy, N.; Sunna, A. (2024) Exploring the Potential of Bioactive Peptides: From Natural Sources to Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci., Vol. 25, 1391. [CrossRef]

- Dewi, A. S., Patantis, G., Fawzya, Y. N., Irianto, H. E., & Sa’diah, S. (2020). Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Activities of Protein Hydrolysates from Indonesian Sea Cucumbers. International Journal of Peptide Research and Therapeutics, 26(4), 2485–2493. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C., Sun, L. C., Yan, L. J., Lin, Y. C., Liu, G. M., & Cao, M. J. (2018). Production, optimisation and characterisation of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from sea cucumber (Stichopus japonicus) gonad. Food & Function, 9(1), 594–603. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Li, B., Liu, Z., Dong, S., Zhao, X., & Zeng, M. (2007). Antihypertensive effect and purification of an ACE inhibitory peptide from sea cucumber gelatin hydrolysate. Process Biochemistry, 42(12), 1586–1591. [CrossRef]

- Sadowska-Bartosz, I.; Bartosz, G. Evaluation of The Antioxidant Capacity of Food Products: Methods, Applications and Limitations. Processes 2022, 10, 2031. [CrossRef]

- Navajas-Porras, B.; Pérez-Burillo, S.; Valverde-Moya, Á.; Hinojosa-Nogueira, D.; Pastoriza, S.; Rufián-Henares, J.Á. (2021) Effect of Cooking Methods on the Antioxidant Capacity of Foods of Animal Origin Submitted to In Vitro Digestion-Fermentation. Antioxidants, 10, 445. [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z.X., Rosman, N.F. In vitro digestion and domestic cooking improved the total antioxidant activity and carbohydrate-digestive enzymes inhibitory potential of selected edible mushrooms. J Food Sci Technol 56, 865–877 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M., Mirdamadi, S. & Safavi, M. Antioxidant activity and protective effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae peptide fractions against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in Caco-2 cells. Food Measure 13, 2654–2662 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Seok C, Baek M, Steinegger M, Park H, Lee GR, Won J. (2021) Accurate protein structure prediction: what comes next? BIODESIGN, Vol. 9:47-50. [CrossRef]

- Pozzati, G, Kundrotas, P, Elofsson, A. Scoring of protein–protein docking models utilizing predicted interface residues. Proteins. 2022; 90( 7): 1493- 1505. [CrossRef]

- Lear S, Cobb SL. Pep-Calc.com: a set of web utilities for the calculation of peptide and peptoid properties and automatic mass spectral peak assignment. J Comput. Aided Mol Des. 2016 Mar;30(3):271-7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Su, X., Shan, L., Liu, Y., Zhang, P., Jia, Y. (2019) Preparation and tribocorrosion performance of CrCN coatings in artificial seawater on different substrates with different bias voltages, Ceramics International, Vol. 45 (8), pp. 9901-9911. [CrossRef]

- Rueden, C. T.; Schindelin, J. & Hiner, M. C. et al. (2017), "ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data", BMC Bioinformatics 18:529, PMID 29187165. [CrossRef]

- Held P (2006). Performing oxygen radical absorbance capacity assays with SynergyTMHT. Application Note. Bio, 9. http://www.biotek.com/resources/docs/ORAC_Assay_Application_Note.pdf.

- Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C (1999). Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, Vol. 26 (9–10). [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Gallardo JM, Osuna-Ruiz I, Martínez-Montaño E, Hernández C, Hurtado-Oliva MÁ, Valdez-Ortiz Á, Rios-Herrera GD, Salazar-Leyva JA, Ramírez-Pérez JS (2020). Influence of enzymatic hydrolysis conditions on biochemical and antioxidant properties of pacific thread herring (Ophistonema libertate) hydrolysates. Vol 18(1), 392–400. [CrossRef]

- Ween O, Stangeland JK, Fylling TS, Aas GH (2017). Nutritional and functional properties of fishmeal produced from fresh by-products of cod (Gadus morhua L.) and saithe (Pollachius virens). Heliyon. Vol 3(7), e00343. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).