Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Agroecosystems support food production through ecosystem services, agricul- tural activities and socio-aspects such as traditional knowledge and technology. These agroecological practices benefit the agroecosystem such as biodiversity, pest control and soil conservation, water conservation and climate change mit-igation. The review aims to investigate the recent advances in sustainable crop production that have emerged over the years such as agroecological practices and precision agriculture. Some agroecological practices reviewed include co-ver crops, intercropping, crop rotations and agroforestry. The practices that were found to have advanced than others were intercropping followed by crop rotation and agroforestry. Factors influencing farmers' adoption or non-adop-tion of these practices such as farm or land size, age, sex, skills and knowledge are also explained. The farm size followed age, skills, and knowledge followed by age and sex were the dominant factors that were responsible for adoption and non-adoption. The various types of crop diversification had an impact on the environment, crop growth and yield.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Crop Diversification

2.1. Cover crops

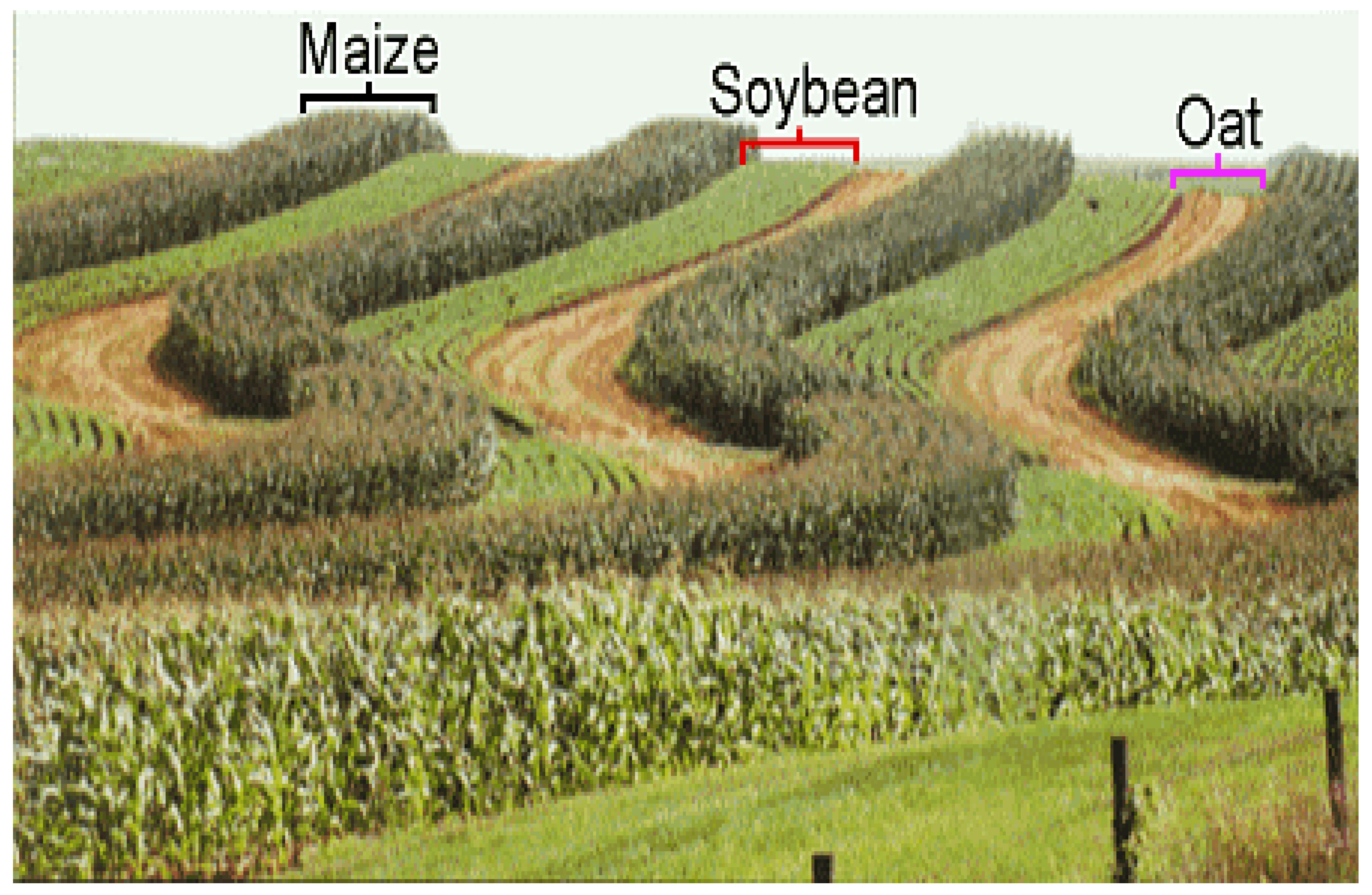

2.2. Intercropping

2.3. Crop rotation

2.4. Agroforestry

3. Sustainable soil management

4. Integrated Pest and Management

5. Sustainable water resource management

6. Precision Agriculture in Agroecosystem Management

7. Conclusions Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Semeraro, T.; Scarano, A.; Leggieri, A.; Calisi, A.; De Caroli, M. Impact of Climate Change on Agroecosystems and Potential Adaptation Strategies. Land 2023, 12, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, A.; Yadav, D.; Srivastava, P.; Babu, S.; Kumar, D.; Singh, D.; Vishwakarma, D. K.; Sharma, V. K.; Madhu, M. Restoration of agroecosystems with conservation agriculture for food security to achieve sustain-able development goals. Land Degrad Dev. 2023, 34, 3079–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarshan, S.; Niveditha, M.P.; Alekhya Gunturi, S.; Chethan Babu, R.T.; KB, C.K. Effects of intensive agricultural management practices on soil biodiversity and implications for ecosystem functioning: A review. Int. J. Res. Agron. 2024, 7, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Agriculture and climate change: challenges and opportunities at the global and local Level—collaboration on climate-smart agriculture. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization. 2019, p. 52.

- Soria-Lopez, A.; Garcia-Perez, P.; Carpena, M.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Otero, P.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Cao, H.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Challenges for future food systems: From the Green Revolution to food supply chains with a special focus on sustainability. Food Front. 2022, 4, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnoi, S.; Goel, R.K. Climate smart agriculture for sustainable productivity and healthy landscapes. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volken, S.; Bottazzi, P. Sustainable farm work in agroecology: how do systemic factors matter? Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purakayastha, T.J.; Bhaduri, D.; Kumar, D.; Yadav, R.; Trivedi, A. Soil and Plant Nutrition. In: Ghosh, P.K., Das, A., Saxena, R., Banerjee, K., Kar, G., Vijay, D. (eds) Trajectory of 75 years of Indian Agriculture after Inde-pendence. Springer, Singapore. 2023.

- Velten, S.; Leventon, J.; Jager, N.; Newig, J. What Is Sustainable Agriculture? A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2015, 7, 7833–7865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathaei, A.; Štreimikienė, D. A Systematic Review of Agricultural Sustainability Indicators. Agriculture 2023, 13, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Herren, B.G.; Kerr, R.B.; Barrios, E.; Gonçalves, A.L.R.; Sinclair, F. Agroecological principles and elements and their implications for transitioning to sustainable food systems. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin-Kordick, R.; De, M.; Lopez, M. D.; Liebman, M.; Lauter, N.; Marino, J.; McDaniel, M.D. Com-prehensive impacts of diversified cropping on soil health and sustainability. Agroecol Sust Food Syst. 2022, 46, 331–363. [Google Scholar]

- Duguma, A.L.; Bai, X. Contribution of Internet of Things (IoT) in improving agricultural systems. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 21, 2195–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmakçı, R.; Haliloglu, K.; Türkoğlu, A.; Özkan, G.; Kutlu, M.; Varmazyari, A.; Molnar, Z.; Jamshidi, B.; Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Bocianowski, J. Effect of Different Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria on Biological Soil Properties, Growth, Yield and Quality of Oregano (Origanum onites L.). Agronomy 2023, 13, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, P.; Loos, J.; Barnes, A.D.; Batáry, P.; Bianchi, F.J.; Buchmann, N.; De Deyn, G.B.; Ebeling, A.; Eisenhauer, N.; Fischer, M.; et al.

- Yang, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, L. INTERCROPPING: FEED MORE PEOPLE AND BUILD MORE SUSTAINABLE AGROECOSYSTEMS. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ochoa, I.M.; Gaiser, T.; Kersebaum, K.C.; Webber, H.; Seidel, S.J.; Grahmann, K.; Ewert, F. Model-based design of crop diversification through new field arrangements in spatially heterogeneous land-scapes. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Yang, H.; Xing, X.; Zhang, W.; Lambers, H. Belowground processes and sustainability in agroecosys-tems with intercropping. Plant Soil. 2022, 476, 263–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudahe, K.; Allen, S.C.; Djaman, K. Critical review of the impact of cover crops on soil properties. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2022, 10, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Niles, M.T. An adoption spectrum for sustainable agriculture practices: A new framework applied to cover crop adoption. Agric. Syst. 2023, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesch-McNally, G.E.; Basche, A.D.; Arbuckle, J.; Tyndall, J.C.; Miguez, F.E.; Bowman, T.; Clay, R. The trouble with cover crops: Farmers’ experiences with overcoming barriers to adoption. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2017, 33, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eerd, L.L.; Chahal, I.; Peng, Y.; Awrey, J.C. Influence of cover crops at the four spheres: A review of ecosystem services, potential barriers, and future directions for North America. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 858, 159990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H. Cover crops and carbon sequestration: Lessons from U.S. studies. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2022, 86, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaque, A. US farmers’ adaptations to climate change: a systematic review of adaptation-focused studies in the US agriculture context. Environ. Res. Clim. 2023, 2, 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, S.C.; Paustian, K.; Schipanski, M.E. Management of cover crops in temperate climates influences soil organic carbon stocks: a meta-analysis. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 31, e2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintarelli, V.; Radicetti, E.; Allevato, E.; Stazi, S.R.; Haider, G.; Abideen, Z.; Bibi, S.; Jamal, A.; Mancinelli, R. Cover Crops for Sustainable Cropping Systems: A Review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apio, A.T.; Thiam, D.R.; Dinar, A. Farming Under Drought: An Analysis of the Factors Influencing Farmers’ Multiple Adoption of Water Conservation Practices to Mitigate Farm-Level Water Scarcity. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2023, 55, 432–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, J.F.; Latournerie-Moreno, L.; Garruña, R.; Jacobsen, K.L.; Laboski, C.A.M.; Us-Santamaría, R.; Ruiz-Sánchez, E. Effect of Maize–Legume Intercropping on Maize Physio-Agronomic Parameters and Beneficial Insect Abundance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.R.; Eskandari, H. A General Overview on Intercropping and Its Advantages in Sustainable Agriculture. JAEBS. 2011, 1, 482–486. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, W.; Ge, J.; Rodríguez, A.R.S.; Zhao, B.; Wang, X.; Peixoto, L.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Zang, H. Oat/soybean strip intercrop-ping benefits crop yield and stability in semi-arid regions: A multi-site and multi-year assessment. Field Crops Res. 2024, 318, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Z. Interspecific interaction and productivity in a dryland wheat/alfalfa strip intercropping. Field Crop. Res. 2024, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Segura, V.; Grass, I.; Breustedt, G.; Rohlfs, M.; Tscharntke, T. Strip intercropping of wheat and oilseed rape enhances biodiversity and biological pest control in a conventionally managed farm scenario. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 59, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DU, J.-B.; Han, T.-F.; Gai, J.-Y.; Yong, T.-W.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.-C.; Yang, F.; Liu, J.; Shu, K.; Liu, W.-G.; et al. Maize-soybean strip intercropping: Achieved a balance between high productivity and sustainability. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, B.; Liu, J.; Dai, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xu, S.; Nie, J.; Wan, S.; Li, C.; Dong, H. Alternate intercropping of cotton and peanut increases productivity by increasing canopy photosynthesis and nutrient uptake under the influence of rhi-zobacteria. Field Crops Res. 2023, 302, 109059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prepp By Collegdunia. Strip Intercropping—Agriculture Notes. Available online: https://prepp.in/news/e-492-strip-intercropping-agriculture-notes (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Lv, Q.; Chi, B.; He, N.; Zhang, D.; Dai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, H. Cotton-based rotation, intercropping, and alternate intercropping increase yields by improving root–shoot relations. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.; Modi, A. T.; Nciizah, A. D. Weeding Frequency Effects on Growth and Yield of Dry Bean Inter-cropped with Sweet Sorghum and Cowpea under a Dryland Area. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.-X.; Shi, P.-X.; Zhang, C.-J.; Si, T.; Wang, Y.-F.; Zhang, X.-J.; Yu, X.-N.; Wang, H.-X.; Wang, M.-L. Rotational strip intercropping of maize and peanuts has multiple benefits for agricultural production in the northern agropastoral ecotone region of China. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, M.; Li, F.; Si, T.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Shi, P. Rotational strip intercropping of maize and peanut enhances productivity by improving crop photosynthetic production and optimizing soil nutrients and bacterial communities. Field Crop. Res. 2022, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Zhou, J.; Luo, B.; Dai, H.; Hu, Y.; Ren, C.; Peixoto, L.; Guo, L.; Wang, C.; Zamanian, K.; et al. Yield advantage and carbon footprint of oat/sunflower relay strip intercropping depending on nitrogen fertilization. Plant Soil 2022, 481, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhou, J.; Ge, J.; Nie, J.; Zhao, J.; Xue, Z.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Peixoto, L.; Zang, H.; et al. Intercropping improves soil ecosystem multifunctionality through enhanced available nutrients but depends on regional factors. Plant Soil 2022, 480, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, J.; Zhao, C.J.; Khan, R.; Gul, H.; Gitari, H.; Shao, Z.; Abbas, G.; Haider, I.; Iqbal, Z.; Ahmed, W.; et al. Maize-soybean intercropping at optimal N fertilization increases the N uptake, N yield and N use efficiency of maize crop by regulating the N assimilatory enzymes. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1077948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Q.; Yan, B.; Fei, J.; Xiangmin, R.; Peng, J.; Luo, G. Intercropping regulation of soil phosphorus composition and microbially-driven dynamics facilitates maize phosphorus uptake and produc-tivity improvement. Field Crops Res. 2022, 287, 108666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basalirwa, D.; Wacal, C.; Murongo, M.F.; Tsubo, M.; Nishihara, E. Agronomic potential of maize stover biochar under cowpea–maize sequential cropping in Northern Uganda. Discov. Agric. 2024, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, S.; Jnana Bharati Palai, J.B.; Manasa, P.; Kumar, D.P. Potential of Intercropping System in Sustaining Crop Productivity. IJAEB. 2019, 12, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librán-Embid, F.; Olagoke, A.; Martin, E.A. Combining Milpa and Push-Pull Technology for sustainable food production in smallholder agriculture. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 43, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J. Push–pull plants in wheat intercropping system to manage Spodoptera frugiperda. J. Pest Sci. 2023, 96, 1579–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdei, A.L.; David, A.B.; Savvidou, E.C.; Džemedžionaitė, V.; Chakravarthy, A.; Molnár, B.P.; Dekker, T. The push–pull intercrop Desmodium does not repel, but intercepts and kills pests. eLife 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Ramos, S.E.; Reichert, L.; Amboka, G.M.; Apel, C.; Chidawanyika, F.; Detebo, A.; Librán-Embid, F.; Meinhof, D.; Bigler, L.; et al. Push–Pull Intercropping Increases the Antiherbivore Benzoxazinoid Glycoside Content in Maize Leaf Tissue. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe). Available online: https://www.icipe.org/news/icipe-push-pull-technology-halts-fall-armyworm-rampage (accessed on 20 Janu-ary 2025).

- Maitra, S.; Sahoo, U.; Sairam, M.; Gitari, H.I.; Rezaei-Chiyaneh, E.; Battaglia, M.L.; Hossain5, A. Cultivating sustainability: A comprehensive review on intercropping in a changing climate. Res. Crop. 2023, UME 24, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mehy, A.A.; Shehata, M.A.; Mohamed, A.S.; Saleh, S.A.; Suliman, A.A. Relay intercropping of maize with common dry beans to rationalize nitrogen fertilizer. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Hamid, A.; Ahmad, T.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Hussain, I.; Ali, S.; Ali, A.; Ahmad, Z. Forage sor-ghum-legumes intercropping effect on growth, yields, nutritional quality and economic returns. Bragantia. 2018, 78, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, L.; Liu, T.; Wei, W.; Zhang, S.; Tuerti, T.; Li, L.; Zhang, W. Juvenile plumcot tree can improve fruit quality and economic benefits by intercropping with alfalfa in semi-arid areas. Agric. Syst. 2022, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yang, H.; Zhang, W.; Bezemer, T.M.; Liang, W.; Li, Q.; Li, L. Interspecific interactions between crops influence soil functional groups and networks in a maize/soybean intercropping system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauggaard-Nielsen, H.; Jørnsgaard, B.; Kinane, J.; Jensen, E. S. Grain legume–cereal intercropping: The practical application of diversity, competition and facilitation in arable and organic cropping systems. Renew Agr Food Syst. 2008, 23, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Zhiqi, W.; Yasin, H.S.; Gul, H.; Qin, R.; Rehman, S.U.; Mahmood, A.; Iqbal, Z.; Ahmed, Z.; Luo, S.; et al. Effect of crop combination on yield performance, nutrient uptake, and land use advantage of cereal/legume intercropping systems. Field Crop. Res. 2023, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwebaze, P.; Macfadyen, S.; De Barro, P.; Bua, A.; Kalyebi, A.; Bayiyana, I.; Tairo, F.; Colvin, J. Adoption determinants of improved cassava varieties and intercropping among East and Central African smallholder farmers. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. Assoc. 2024, 3, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toker, P.; Canci, H.; Turhan, I.; Isci, A.; Scherzinger, M.; Kordrostami, M.; Yol, E. The advantages of intercropping to improve productivity in food and forage production—a review. Plant Prod. Sci. 2024, 27, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.M.; Manevska-Tasevska, G.; Jäck, O.; Weih, M.; Hansson, H. Farmers’ intention towards intercropping adoption: the role of socioeconomic and behavioural drivers. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, A.; Ikram, R.M.; Ali, H.H.

- Smith, M.E.; Vico, G.; Costa, A.; Bowles, T.; Gaudin, A.C.M.; Hallin, S.; Watson, C.A.; Alarcòn, R.; Berti, A.; Blecharczyk, A.; et al. Increasing crop rotational diversity can enhance cereal yields. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Sui, P. Changes in soil microbial biomass, diversity, and activity with crop rotation in cropping systems: A global synthesis. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruyn, M.; Nel, A.; van Niekerk, J. The effect of crop rotation on agricultural sustainability in the North-Western Free State, South Africa. AJSAD. 2024, 5, 32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mwila, M.; Silva, J.V.; Kalala, K.; Simutowe, E.; Ngoma, H.; Nyagumbo, I.; Mataa, M.; Thierfelder, C. Do rotations and intercrops matter? Opportunities for intensification and diversification of maize-based cropping systems in Zambia. Field Crop. Res. 2024, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Du, G.; Faye, B. The influence of cultivated land transfer and Internet use on crop rotation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Feng, S. Crop Rotation and Diversification in China: Enhancing Sustainable Agriculture and Resilience. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xiong, J.; Du, T.; Ju, X.; Gan, Y.; Li, S.; Xia, L.; Shen, Y.; Pacenka, S.; Steenhuis, T.S.; et al. Diversifying crop rotation increases food production, reduces net greenhouse gas emissions and improves soil health. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, T.; Kao, N. PLA Based Biopolymer Reinforced with Natural Fibre: A Review. J. Polym. Environ. 2011, 19, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, L.; Zhang, J.; Coulter, J.A.; Li, L.; Gan, Y. Diversifying crop rotation improves system robustness. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.K.; Modi, B.; Pandey, H.P.; Subedi, A.; Aryal, G.; Pandey, M.; Shrestha, J. Diversified Crop Rotation: An Approach for Sustainable Agriculture Production. Adv. Agric. 2021, 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Chavan, S.B.; Chichaghare, A.R.; Uthappa, A.R.; Kumar, M.; Kakade, V.; Pradhan, A.; Jinger, D.; Rawale, G.; Yadav, D.K.; et al. Agroforestry Systems for Soil Health Improvement and Maintenance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, D.E.T.; Yeo, S.; Almaraz, M.; Beillouin, D.; Cardinael, R.; Garcia, E.; Kay, S.; Lovell, S.T.; Rosenstock, T.S.; Sprenkle-Hyppolite, S.; et al. Priority science can accelerate agroforestry as a natural climate solution. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2023, 13, 1179–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpoviwanou, M.R.J.H.; Sourou, B.N.K.; Ouinsavi, C.A.I.N. Challenges in adoption and wide use of agroforestry technologies in Africa and pathways for improvement: A systematic review. Trees, For. People 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogale, G.A.; Bekele, S.E. Sustainability of Agroforestry Practices and their Resilience to Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review. Ekologia 2023, 42, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, P.; Behera, B.; Rahut, D.B. India's approach to agroforestry as an effective strategy in the context of climate change: An evaluation of 28 state climate change action plans. Agric. Syst. 2023, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, M.; Khanal, A.; Bhatt, D.; Dahal, D.; Giri, S. Agroforestry systems in Nepal: Enhancing food security and rural livelihoods—a comprehensive review. Food Energy Secur. 2024, 13, e524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Coffee Report. Agroforestry steps into the light. Available online: https://www.gcrmag.com/agroforestry-steps-into-the-light/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Thiesmeier, A.; Zander, P. Can agroforestry compete? A scoping review of the economic performance of agroforestry practices in Europe and North America. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibalya, J.Y.; Chiputwaa, B.; Nakelseb, T.; Kundhland, G. Adoption of agroforestry and the impact on household food security among farmers in Malawi. Agric. Syst. 2017, 155, 52–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Xu, H.; Ekanayake, E.M.B.P. Socioeconomic Determinants and Perceptions of Smallholder Farmers towards Agroforestry Adoption in Northern Irrigated Plain, Pakistan. Land 2023, 12, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tega, M.; Bojago, E. Determinants of smallholder farmers’ adoption of agroforestry practices: Sodo Zuriya District, southern Ethiopia. Agrofor. Syst. 2024, 98, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubblefield, K.; Smith, M.; Lovell, S.; Wilson, K.; Hendrickson, M.; Cai, Z. Factors affecting Missouri land managers’ willingness-to-adopt agroforestry practices. Agrofor. Syst. 2024, 99, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaca, F.N.; Ngidi, M.S.C.; Chipfupa, U.; Ojo, T.O.; Managa, L.R. Factors influencing the uptake of agroforestry practices among rural households: Empirical Evidence from the KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Forests. 2023, 2, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappa, L.R.; Nungula, E.Z.; Makwinja, Y.H.; Ranjan, S.; Sow, S.; Alnemari, A.M.; Maitra, S.; Seleiman, M.F.; Mwadalu, R.; Gitari, H.I.

- Daneel, M.; Engelbrecht, E.; Fourie, H.; Ahuja, P. The host status of Brassicaceae to Meloidogyne and their effects as cover and biofumigant crops on root-knot nematode populations associated with potato and tomato under South African field conditions. Crop. Prot. 2018, 110, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, I.I.; Bell, L.W.; Chauhan, B.S.; Williams, A. Optimizing ecosystem function multifunctionality with cover crops for improved agronomic and environmental outcomes in dryland cropping systems. Agric. Syst. 2023, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torun, H. The use of cover crop for weed suppression and competition in limited-irrigation vineyards. Phytoparasitica 2024, 52, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, E.H.; Strauss, J.A.; Swanepoel, P.A. Utilisation of cover crops: implications for conservation agriculture systems in a mediterranean climate region of South Africa. Plant Soil 2021, 462, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ghimire, R.; Acharya, P. Soil profile carbon sequestration and nutrient responses varied with cover crops in irrigated forage rotations. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Sainju, U.M.; Zhang, S.; Tan, G.; Wen, M.; Dou, Y.; Yang, R.; Chen, J.; Zhao, F.; Wang, J. Cover cropping promotes soil carbon sequestration by enhancing microaggregate-protected and mineral-associated carbon. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 908, 168330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, W.; Goodwin, P.H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, S.-J.; Li, X. Effect of cover crop on soil fertility and bacterial diversity in a banana plantation in southwestern China. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Din, A.M.U.; Shah, G.A.; Zhiqi, W.; Feng, L.Y.; Gul, H.; Yasin, H.S.; Rahman, M.S.U.; Juan, C.; Liang, X.; et al. Legume choice and planting configuration influence intercrop nutrient and yield gains through complementarity and selection effects in legume-based wheat intercropping systems. Agric. Syst. 2024, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buakong, W.; Suwanmanee, P.; Ruttajorn, K.; Asawatreratanakul, K.; Leake, J.E. Sustainable Rubber Production Intercrop with Mixed Fruits to Improve Physiological Factors, Productivity, and Income. ASEAN J. Sci. Technol. Rep. 2024, 27, e254945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinyua, M.; Kihara, J.; Bekunda, M.; Bolo, P.; Mairura, F.; Fischer, G.; Mucheru-Muna, M. Agronomic and economic performance of legume-legume and cereal-legume intercropping systems in Northern Tanzania. Agric. Syst. 2022, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Ramos, S.E.; Reichert, L.; Amboka, G.M.; Apel, C.; Chidawanyika, F.; Detebo, A.; Librán-Embid, F.; Meinhof, D.; Bigler, L.; et al. Push–Pull Intercropping Increases the Antiherbivore Benzoxazinoid Glycoside Content in Maize Leaf Tissue. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Huertas, J.; Parras-Alcántara, L.; González-Rosado, M.; Lozano-García, B. Intercropping in rainfed Mediterranean olive groves contributes to improving soil quality and soil organic carbon storage. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogale, T.E.; Ayisi,K.K.; Munjonji, L.; Kifle, Y.G.; Mabitsela, K.E. Understanding the Impact of the Intercrop-ping System on Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions and Soil Carbon Stocks in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Hindawi Int. J. Agron. 2023, Article ID 6307673. [CrossRef]

- Sanfo, A.; Zampaligre’, N.; Kulo, A.E.; Some’, S.; Traore’, K.; Rios, E.F.; Dubeux, J.C.B.; Boote, K.J.; Adesogan, A. Performance of food–feed maize and cowpea cultivars under monoculture and intercropping systems: Grain yield, fodder biomass, and nutritive value. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 3, 998012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimande, P.; Arrobas, M.; Rodrigues, M.Â. Intercropped Maize and Cowpea Increased the Land Equivalent Ratio and Enhanced Crop Access to More Nitrogen and Phosphorus Compared to Cultivation as Sole Crops. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurgi, N.; Tana, T.; Dechassa, N.; Tesso, B.; Alemayehu, Y. Effect of spatial arrangement of faba bean variety intercropping with maize on yield and yield components of the crops. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yin, M.; Duan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wan, H.; Kang, Y.; Qi, G.; Jia, Q. Enhancing Water and Soil Resources Utilization via Wolfberry–Alfalfa Intercropping. Plants 2024, 13, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, F.; Carlesi, S.; Triacca, A.; Koskey, G.; Croceri, G.; Antichi, D.; Moonen, A.-C. A three-stage approach for co-designing diversified cropping systems with farmers: the case study of lentil-wheat intercropping. Ital. J. Agron. 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaddar, S.; Schmidt, R.; Tautges, N.E.; Scow, K. Adding alfalfa to an annual crop rotation shifts the composition and functional responses of tomato rhizosphere microbial communities. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 167, 104102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pofu, K.M.; Mashela, P.W.; Venter, S.L. Dry bean cultivars with the potential for use in potato–dry bean crop rotation systems for managing root-knot nematodes in South Africa. South Afr. J. Plant Soil 2019, 36, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yang, C.; Fu, J.; Song, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Ma, C. Effects of crop rotation on sugar beet growth through improving soil physicochemical properties and microbiome. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Wu, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Fu, Q. Integrative cultivation pattern, distribution, yield and potential benefit of rubber based agroforestry system in China. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaupel, A.; Küsters, M.; Toups, J.; Herwig, N.; Bösel, B.; Beule, L. Trees shape the soil microbiome of a temperate agrosilvopastoral and syntropic agroforestry system. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilinti, B.; Negash, M.; Asfaw, Z.; Woldeamanuel, T. Variations in carbon stocks across traditional and improved agroforestry in reference to agroforestry and households’ characteristics in Southeastern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimaro, O.D.; Desie, E.; Verbist, B.; Kimaro, D.N.; Vancampenhout, K.; Feger, K.-H. Soil organic carbon stocks and fertility in smallholder indigenous agroforestry systems of the North-Eastern mountains, Tanzania. Geoderma Reg. 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M.d.S.; Barreto-Garcia, P.A.B.; Monroe, P.H.M.; Pereira, M.G.; Barros, W.T.; Nunes, M.R. Carbon in soil macroaggregates under coffee agroforestry systems: Modeling the effect of edaphic fauna and residue input. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahalvi, H.N.; Rafiya, L.; Rashid, S.; Nisar, B.; Kamili, A.N. Chemical Fertilizers and Their Impact on Soil Health. In: Dar, G.H., Bhat, R.A., Mehmood, M.A., Hakeem, K.R. (eds) Microbiota and Biofertilizers, Vol 2. Springer, Cham. 2021.

- Szymańska, M.; Gubiec, W.; Smreczak, B.; Ukalska-Jaruga, A.; Sosulski, T. How Does Specialization in Agricultural Production Affect Soil Health? Agriculture 2024, 14, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Asyakina, L.K.; Serazetdinova, Y.R.; Frolova, A.S.; Velichkovich, N.S.; Prosekov, A.Y. Microorganisms for Bioremediation of Soils Contaminated with Heavy Metals. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jote, C. A. The impacts of using inorganic chemical fertilizers on the environment and human health. Organ Med Chem Int J. 2023, 13, 555864. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.; Khan, M.S.; Singh, U.B. Pesticide-tolerant microbial consortia: Potential candidates for remedia-tion/clean-up of pesticide-contaminated agricultural soil Environ. Res. 2023, 236, 116724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadu, C.O.; Ezema, C.A.; Ekwueme, B.N.; Onu, C.E.; Onoh, I.M.; Adejoh, T.; Ezeorba, T.P.C.; Ogbonna, C.C.; Otuh, P.I.; Okoye, J.O.; et al. Enhanced efficiency fertilizers: Overview of production methods, materials used, nutrients release mechanisms, benefits and considerations. J. Environ. Pollut. Manag. 2024, 1, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Schievano, A.; Bosco, S.; Montero-Castaño, A.; Tamburini, G.; Pérez-Soba, M.; Makowski, D. Evidence map of the benefits of enhanced-efficiency fertilisers for the environment, nutrient use efficiency, soil fertility, and crop production. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 043005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.; Rashid, G. Biofertilisers and Biopesticides: Approaches Towards Sustainable Development. In: Dar, G.H., Bhat, R.A., Mehmood, M.A. (eds) Microbiomes for the Management of Agricultural Sustainability. Springer, Cham. 2023.

- Rafeeq, H.; Riaz, Z.; Shahzadi, A.; Gul, S.; Idress, F.; Ashraf, S.; Hussain, A.

- Mokrani, S.; Houali, K.; Yadav, K.K.; Arabi, A.I.A.; Eltayeb, L.B.; AwjanAlreshidi, M.; Benguerba, Y.; Cabral-Pinto, M.M.; Nabti, E.-H. Bioremediation techniques for soil organic pollution: Mechanisms, microorganisms, and technologies - A comprehensive review. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, F.; Marini, E.; De Bernardi, A.; Vischetti, C.; Casucci, C. A Systematic Review on Earthworms in Soil Bioremediation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, P.; Chandran, S.S. Nano-Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals from Soil: A Critical Review. Pollutants. 2023, 3, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Singh, G.; Santal, A.R.; Singh, N.P. Omics approaches in effective selection and generation of potential plants for phytoremediation of heavy metal from contaminated resources. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 336, 117730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dara, S.K. The New Integrated Pest Management Paradigm for the Modern Age. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraban, G.M.; Hlihor, R.-M.; Suteu, D. Pesticides vs. Biopesticides: From Pest Management to Toxicity and Impacts on the Environment and Human Health. Toxics 2023, 11, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratti, I.; Korres, N.E.; Cordeau, S. Knowledge of Cover Crop Seed Traits and Treatments to Enhance Weed Suppression: A Narrative Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, C.P.; Singh, R.G.; Choudhary, V.K.; Datta, D.; Nandan, R.; Singh, S.S. Challenges and Alternatives of Herbicide-Based Weed Management. Agronomy 2024, 14, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, J.A.; Fan, R.; Naz, H.; Bamisile, B.S.; Hafeez, M.; Ghani, M.I.; Wei, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X. Insights into insecticide-resistance mechanisms in invasive species: Challenges and control strategies. Front. Physiol. 2023, 13, 1112278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendžić, S.; Zovko, M.; Živković, I.P.; Lešić, V.; Lemić, D. The impact of climate change on agricultural insects pests. Insects 2021, 12, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Riat, A.K.; Bhat, K.A.; Ganie, S.A.; Endarto, O.; Nugroho, C.; Handoko, H.; Wani, A.K. Adapting to climate extremes: Implications for insect populations and sustainable solutions. J. Nat. Conserv. 2024, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, B.; Poudel, A.; Aryal, S. The impact of climate change on insect pest biology and ecology: Implications for pest management strategies, crop production, and food security. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Adeleke, B.S.; Akinola, S.A.; Fayose, C.A.; Adeyemi, U.T.; Gbadegesin, L.A.; Omole, R.K.; Johnson, R.M.; Uthman, Q.O.; Babalola, O.O. Biopesticides as a promising alternative to synthetic pesticides: A case for microbial pesticides, phytopesticides, and nanobiopesticides. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1040901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smagghe, F.; Spooner-Hart, R.; Chen, Z.-H.; Donovan-Mak, M. Biological control of arthropod pests in protected cropping by employing entomopathogens: Efficiency, production and safety. Biol. Control. 2023, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, H.A.; Fahmy, H.M.; Arafa, F.N.; Abd Allah, M.Y.; Tawfik, Y.M.; El Halwany, K.K.; El-Ashmanty, B.A.; Al-Anany, F.S.; Mohamed, M.A.; Bassily, M.E. Nanotechnology in pest management: advantages, applications, and challenges. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2023, 43, 1387–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofuya, T.I.; Okunlola, A.I.; Mbata, G.N. A Review of Insect Pest Management in Vegetable Crop Production in Nigeria. Insects 2023, 14, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouhan, S.; Kumari, S.; Kumar, R.; Chaudhary, P.L. Climate Resilient Water Management for Sustainable Agriculture. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2023, 13, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David L. Hoover, Lori J. Abendroth, Dawn M. Browning, Amartya Saha, Keirith Snyder, Pradeep Wagle, Lindsey Witthaus, Claire Baffaut, Joel A. Biederman, David D. Bosch, Rosvel Bracho, Dennis Busch, Patrick Clark, Patrick Ellsworth, Philip A. Fay, Gerald Flerchinger, Sean Kearney, Lucia Levers, Nicanor Saliendra, Marty Schmer, Harry Schomberg, Russell L. Scott,Indicators of water use efficiency across diverse agroecosystems and spatiotemporal scales,Science of The Total Environment,Volume 864,2023,160992,ISSN 0048-9697. [CrossRef]

- Lankford, B.; Pringle, C.; McCosh, J.; Shabalala, M.; Hess, T.; Knox, J.W. Irrigation area, efficiency and water storage mediate the drought resilience of irrigated agriculture in a semi-arid catchment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 859, 160263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmulthum, N.A.; Zeineldin, F.I.; Al-Khateeb, S.A.; Al-Barrak, K.M.; Mohammed, T.A.; Sattar, M.N.; Mohmand, A.S. Water Use Efficiency and Economic Evaluation of the Hydroponic versus Conventional Cul-tivation Systems for Green Fodder Production in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2023, 15, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togneri, R.; Prati, R.; Nagano, H.; Kamienski, C. Data-driven water need estimation for IoT-based smart irrigation: A survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 225. 120194. [CrossRef]

- Petrović, B.; Bumbálek, R.; Zoubek, T.; Kuneš, R.; Smutný, L.; Bartoš, P. Application of precision agriculture technologies in Central Europe-review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.V.; Magulur, L.P.S.; Priya, G.; Kaur, A.; Singh, G.; Boopathi, S. Handbook of Research on Data Science and Cybersecurity Innovations in Industry 4.0 Technologies. 2023. pp 524-540.

- Artificial Intelligence Tools and Technologies for Smart Farming and Agriculture Practices; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, United States, 2023; ISBN: 9781466641778.

- Akintuyi, O.B. Adaptive AI in precision agriculture: A review: Investigating the use of self-learning algorithms in optimizing farm operations based on real-time data. Open Access Res. J. Sci. Technol. 2024, 7, 016–030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, B.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Y. A Review of RGB Image-Based Internet of Things in Smart Agriculture. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 23, 24107–24122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasera, R.K.; Gour, S.; Acharjee, T. A. comprehensive survey on IoT and AI-based applications in different pre-harvest, during-harvest and post-harvest activities of smart agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 216, 108522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kganyago, M.; Adjorlolo, C.; Mhangara, P.; Tsoeleng, L. Optical remote sensing of crop biophysical and biochemical parameters: An overview of advances in sensor technologies and machine learning algorithms for precision agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, G.; Porras, R.; Florencia, R.; Sánchez-Solís, J.P. LiDAR applications in precision agriculture for cultivating crops: A review of recent advances. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Chung, Y.S. A short review of RGB sensor applications for accessible high-throughput phenotyping. J. Crop. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 24, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, S.K.B.; Mani, P.; Maheshwari, V.; Jayagopal, P.; Kumar, M.S.; Allayear, S.M. Design and Analysis of Multilayered Neural Network-Based Intrusion Detection System in the Internet of Things Network. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erekalo, K.T.; Pedersen, S.M.; Christensen, T.; Denver, S.; Gemtou, M.; Fountas, S.; Isakhanyan, G. Review on the contribution of farming practices and technologies towards climate-smart agricultural outcomes in a Eu-ropean context. Smart Agricultural Technology. 2024, 7, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunathilake, E.M.B.M.; Le, A.T.; Heo, S.; Chung, Y.S.; Mansoor, S. The Path to Smart Farming: Innovations and Opportunities in Precision Agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamides, G.; Kalatzis, N.; Stylianou, A.; Marianos, N.; Chatzipapadopoulos, F.; Giannakopoulou, M.; Papadavid, G.; Vassiliou, V.; Neocleous, D. Smart Farming Techniques for Climate Change Adaptation in Cyprus. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaouia, M.; Hajji, B.; Rabhi, A.; Benzaouia, S.; Mellit, A. Real-time Super Twisting Algorithm based fuzzy logic dynamic power management strategy for Hybrid Power Generation System. J. Energy Storage 2023, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, P.P.; Momi, S.; Chizema, T.; Van Grenuen, D. Implementing a cost-effective soil monitoring system using wireless sensor networks to enhance farming practices for small-scale farmers in developing economy countries. WJAFS. 2024, ISSN: 2960-0227.

- Langa, R.M.; Moeti, M.N. “An IoT-Based Automated Farming Irrigation System for Farmers in Limpopo Province,” JINITA. 2024, 6, 12–27. [CrossRef]

- Mogale, T.E.; Ayisi, K.K.; Munjonji, L.; Kifle, Y.G.; Mabitsela, K.E. Understanding the Impact of the Inter-cropping System on Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions and Soil Carbon Stocks in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Hindawi Int. J. Agron. 2023, Article ID 6307673. [CrossRef]

- Kihoma, L.L.; Churi, A.J.; Sanga, C.A.; Tisselli, E. Examining the continued intention of using the Ugunduzi app in farmer-led research of agro-ecological practices among smallholder farmers in selected areas, Tanzania. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2023, 15, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Practices | Countries | Impact on agroecosystem | Impact on crop production | Contribution to climate change mitigation | References |

| Cover cropping potatoes and tomatoes with Brassicaceae plants such as oil seed radish and rocket salad | S. Africa | Reduced population densities of the root-knot nematodes M. incognita and M. javanica | Increase in crop biomass | Not specified | Daneel et al. [86] |

| Cover cropping legume or oat crops incomplete | Australia | N cycling and fixation, C cycling, water conservation, pest reduction | Cover crop biomass production and food production profitability | Reduced pesticides | Garba et al. [87] Torun [88] |

| Cover cropping wheat with legume | S. Africa | Soil quality was improved and N fixation | Increased wheat grain quality | Decreased use of N fertilizers after improved N fixation | Smit et al. [89] |

| Cover cropping sorghum and maize with annual ryegrass, winter triticale, turnip, daikon radish and pea | Mexico | Improved organic carbon and nitrogen in the soil and increased soil fertility | Improved crop yields | Increased carbon sequestration | Singh et al. [90] |

| Cover crops such as soybean, sudangrass and soybean-sudangrass mixture before wheat planting each year. | China | Improved soil minerals, soil carbon stabilisation and enhanced soil aggregation | Not specified | Increased carbon sequestration | Zhu et al. [91] |

| Bananas grown with goosegrass and siratro cover crops | China | Soil organic increase, total nitrogen and total phosphorus increase and increased phosphatase, catalase, invertase and urease activities from soil bacteria communities | Not specified | Not specified | Xu et al. [92] |

| Wheat and chickpea intercropping | Pakistan | N and P increase in the soil | Wheat and chickpea grain quality improved and biomass increased | Not specified | Raza et al. [93] |

| Intercropping rubber, timber fruit, and shrub trees |

Thailand | Improved the soil quality | Higher fruit production | Reduced temperature (lowered light intensity) and increased humidity | Buakong et al. [94] |

| Cowpea and wheat intercropping | Tanzania | Improved soil fertility, weed control, decrease in pests and crop diseases | Improved crop yield | Higher radiation interception | Kinyua et al. [95] |

| Desmodium spp. employed as intercrop and Brachiaria or Napier grass employed as border crops with maize | Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda | Increased maize resistance to herbivore attacks, insect and weed pests’ control and increased N fixation by Desmodium | Improved maize yields | Not specified | Lang et al. [96] |

| Intercropping olive with Crocus sativus, Vicia sativa, Avena sativa in and Lavandula intermedia with olive orchards | Spain | Soil-improved carbon storage, N fixation | No effects on crop yield detected | Increased carbon sequestration in the soil | Aguilera-Huerts et al. [97] |

| Sorghum-cowpea intercropping in a no-tillage system | S. Africa | Reduced carbon emissions and improved carbon storage in the soil | N-fixation in the soil, C storage in the soil |

Less CO2 emissions in the atmosphere | Mogale et al. [98] |

| Maize and Cowpea intercropping | Burkina Faso, Mozambique | Weed reduction increased N fixation, increased phosphorous in the soil | Increased maize production, increased maize and fodder production | Not specified | Sanfo et al. [99] Dimande et al. [100] |

| Maize and faba bean intercropping | Ethiopia | Not specified | Maize grain yield increase and biomass increase | Not specified | Nurgi et al. [101] |

| Wolfberry intercropped with alfalfa | China | Improved water use efficiency (WUE) by the tree leaves, reduced soil water loss | Increase in Wolfberry biomass | Not specified | Wang et al. [102] |

| Relay intercropping of winter durum wheat with lentil | Italy | Weed suppression, increased nutrient availability and improved soil microbial matter |

Increase in wheat and lentil yields | Not specified | Leoni et al. [103] |

| Tomato and alfalfa crop rotation | America | Enhanced soil nutrient availability, pest suppression | Improved quality yield of tomato crops | N and C soil fixation reducing atmospheric N and C | Samaddar et al. [104] |

| Crop rotation of potato cultivars with dry bean cultivars | South Africa | Reduced levels of Meloidogyne pest | Increase in yields Reduced infestation by Meloidogyne spp in one cultivar |

Not specified | Pofu et al. [105] |

| Rubber dandelion and sugar beet crop rotation | China | Enhanced soil microbiome and increased abundance of Actinobacteria and Streptomyces. | Increased sugar beet biomass, increased urease activity in the soil, N fixation, phosphorous and potassium increase | Not specified | Guo et al. [106] |

| Agroforestry practice of planting rubber trees with different types of trees and fruit trees | China | Water and soil conservation increased light-use efficiency | Increase in the fruit yield in fruit trees | Not specified | Qi et al. [107] |

| Agrosilvopastoral system of trees, crops, and livestock and a syntropic agroforestry system of trees, shrub species, and forage crops. | Germany | Improved soil microbiome and a reduction in plant diseases | Not specified | Soil organic carbon storage increases under syntropic agroforestry | Vaupel et al. [108] |

| Homegarden agroforestry | Ethiopia | Improved soil properties such as pH and improved soil density | Fruit yield not specified but improvement in stem density and tree height | The home gardens act as carbon sinks | Tilinti et al. [109] |

| Ginger and mixed spices agroforestry | Tanzania | Improved soil fertility | Soil organic carbon sequestration | Kimaro et al. [110] | |

| Coffee agroforestry systems | Brazil | Improved soil microfauna and improved organic matter | Not specified | Soil organic carbon storage | dos Santos Nascimento et al. [111] |

| Technological advancement | Application approach | Country |

Contribution to agroecosystem |

References |

| Data collection using sensors in the field using the Gaiasense system | Automatic field stations | Cyprus | Detection of soil moisture, temperature, humidity, wind, precipitation and atmospheric pressure | Adamides et al. [154] |

| Fuzzy logic (FL) controller, and long-range data transmission and monitoring via the LoRa protocol | Smart precision irrigation | Morocco | Saving water and energy | Benzaouia et al. [155] |

| Wireless Sensor Networks (WSN) using Arduino UNO WiFi Rev2 board server |

Soil monitoring system | South Africa | Monitoring of soil conditions, weather patterns, and crop development | Dlamini et al. [156] |

| Data collection technology using Arduino ESP Wi-Fi technology | Automated irrigation | South Africa | Detects soil moisture and assists in water-use efficiency | Langa et al. [157] |

| GMP343 used with MI70 data logger | Measurement of CO2 emissions | South Africa | Determination of carbon stocks between intercropping and monocropping systems | Mogale et al. [158] |

| Ugunduzi Mobile App | To conduct field research | Tanzania | Monitoring maize and cassava crops through gathering, visualization & statistical analysis of soil fertility, conservation and biodiversity | Kihoma et al. [159] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).