Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

THE PROBLEM

OUR PROPOSAL

A FINAL WORD

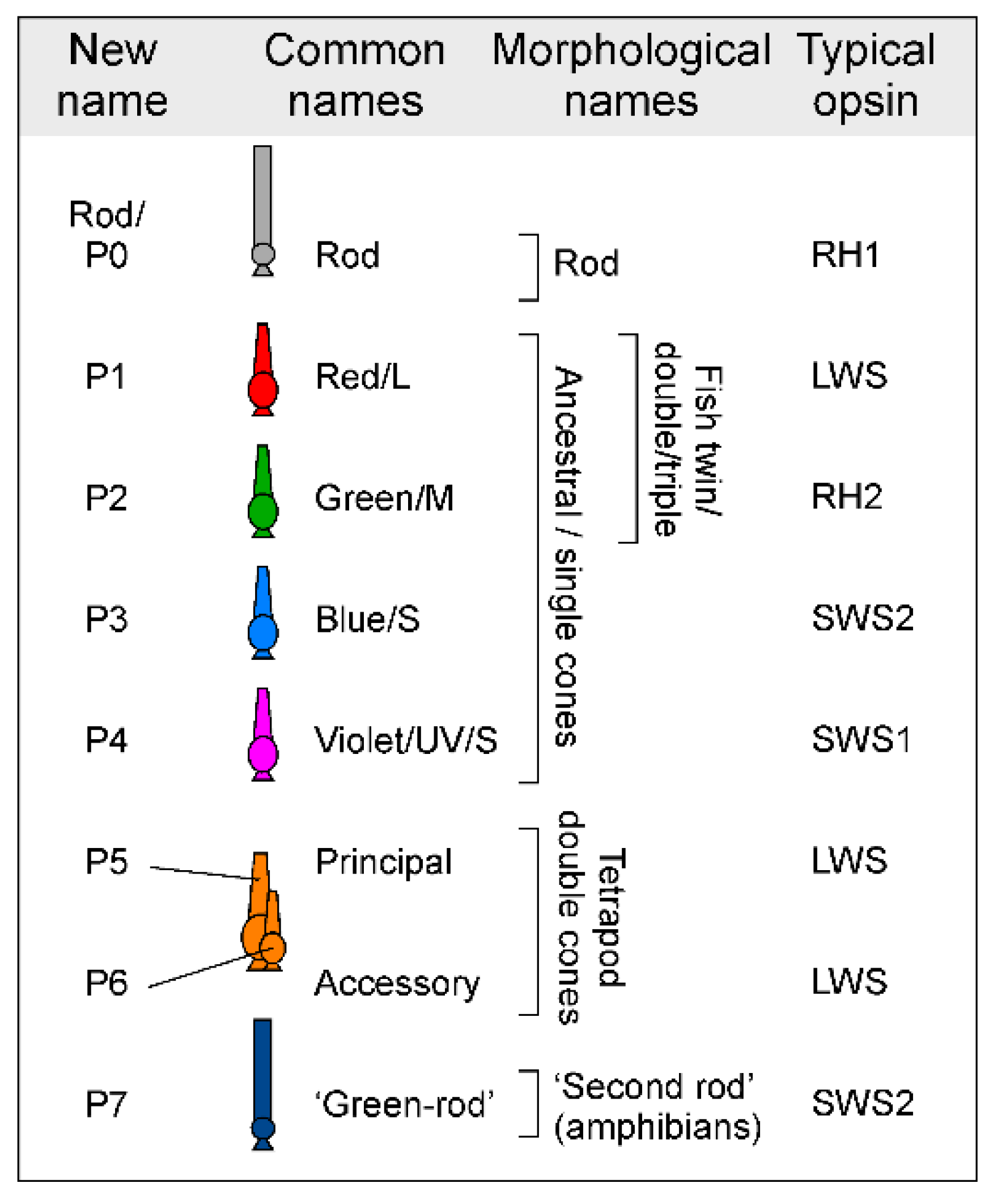

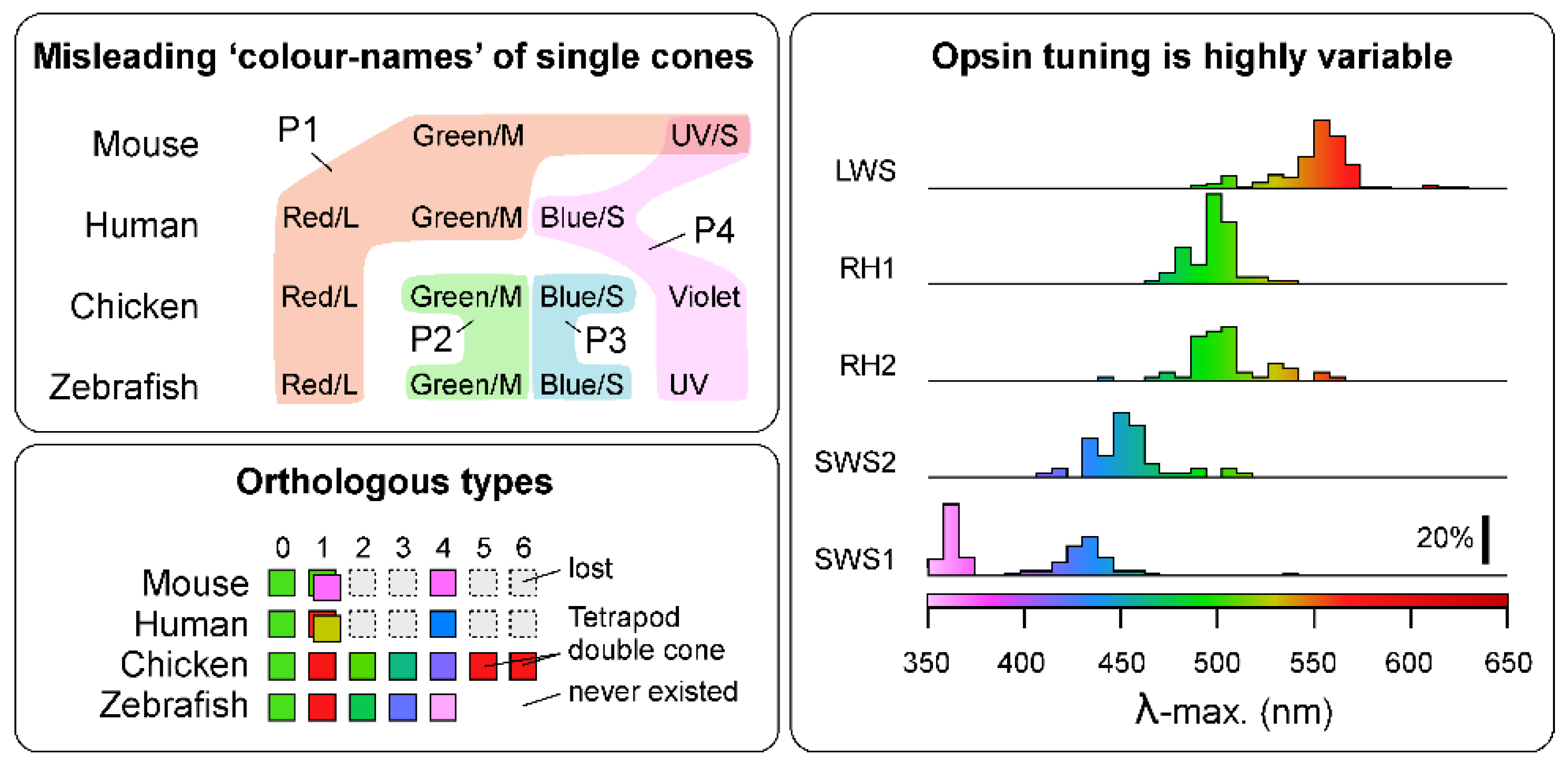

- Box 1. Opsins and their spectral properties are poor indicators of cone identity.

- Comparison of humans, zebrafish, and mice illustrates the central problem. Humans and zebrafish have ‘red/L’, ‘green/M’ and ‘blue/S’ cones, while zebrafish additionally have ultraviolet (UV) cones [4], but human ‘green/M’ and ‘blue/S’ cones are evolutionarily unrelated to zebrafish ‘green/M’ and ‘blue/S’ cones [17]. The opsins of human ‘green/M’ and ‘red/L’ cones are orthologous to zebrafish ‘red/L’ (all express LWS), and human ‘blue/S’ to zebrafish UV (both express SWS1). However, this match by opsins is fortuitous in the sense that both human and zebrafish cones, where present, consistently express variants of their ancestrally linked opsins: LWS, RH2, SWS2 and SWS1 for P1-4, respectively [2]. By contrast, the opsin scheme falls apart in mice because mouse P1 cones (which are often referred to as ‘green/M’ in reference to their ‘green-shifted’ LWS opsin) co-express the ancestral UV-opsin SWS1 in the ventral retina [51,52,53]. The same ancestral neuron type P1 therefore transitions from ‘functionally green’ to ‘functionally UV’ along the dorsal-ventral axis of the retina. Moreover mice retain the ancestral UV-cone P4, which like the SWS1-coexpressing P1 cones are more concentrated in the ventral retina [65]. Mice therefore have two types of UV-sensitive cones in direct proximity. Similarly, some fish species including cichlids and salmonids are known to switch opsin expression in individual cones, such that P1 cones may express LWS or RH2 opsins, and P4 cones may express SWS1 or SWS2 opsins depending on developmental stage or environmental cues [66,67,68]. While these examples illustrate the problem, they are not outliers in the vertebrate tree of life. The identity and wavelength specificity of expressed cone opsins is subject to routine variation [1,2], both across species (e.g., Ref [69]) as well as within species (including by retinal region [51,52], life stage [70], season [71,72,73], and environment [74]). It further depends on an opsin’s associated chromophore (A1 or A2) [75,76], which also varies seasonably and according to life stage. In fact, opsins and their properties are an evolutionary hotspot, varying as species enter new visual niches [2,77]. The identity or functional properties of opsins therefore do not reliably specify the identity of the neuron that expresses them.

- A second issue is that a definition by ‘colour’ implies that wavelength selectivity is the only important characteristic of a photoreceptor. This is misleading4, because beyond wavelength selectivity, cone types systematically differ in their basic cellular physiology including their spatio-temporal properties [78,79,80], as well as in their developmental postsynaptic wiring [22,36,81] – all of which directly feed into their distinct roles in vision [49].

- Box 2. Cellular morphology is an imperfect indicator of photoreceptor identity.

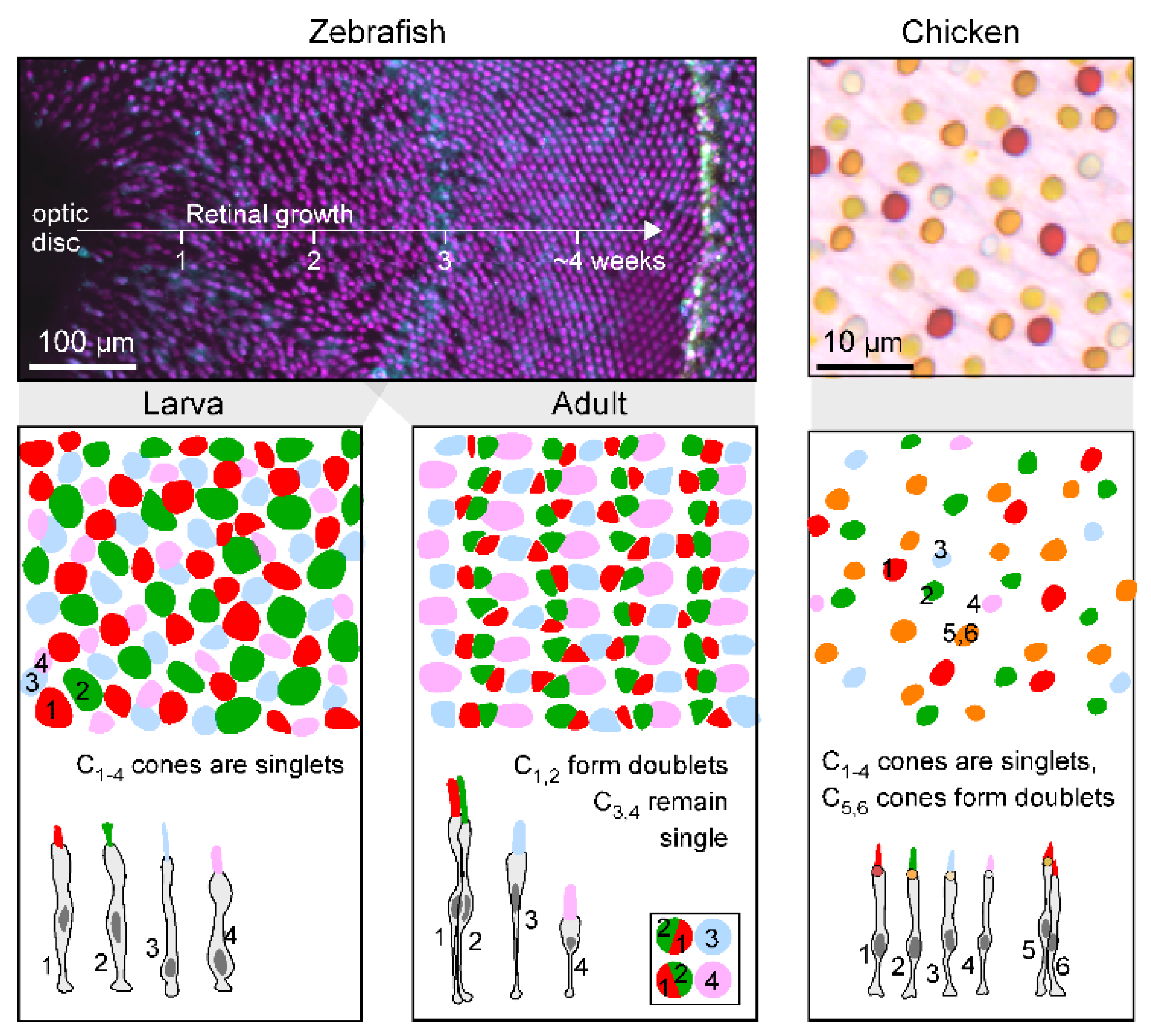

- Morphological definitions of photoreceptor types based on the shape of the outer segment (i.e., ‘rod’ vs. ‘cone’), association with other photoreceptors (e.g., ‘single’ vs. ‘double’ cones) or other cellular features are as problematic as opsin-based definitions. Photoreceptors can be grouped into ‘morphological types’, namely ‘single cones’ which tend to occur in isolation, ‘twin’ cones [3] which comprise pairs made up of morphologically identical partners, and ‘double/triple cones’ consisting of asymmetric groups, often with ‘principal’ and ‘accessory’ members [3,7,24,82]. Single cones are occasionally further identified by other descriptors such as ‘long’, ‘short’ [83], and miniature [84] in reference to their size and/or vertical location in the outer retina. However, there are many factors that influence the anatomical arrangement of photoreceptors, and like opsin or spectral identity, none are reliably stable across species, or within.

- Box 3. Naming yet-to-be-identified photoreceptor types.

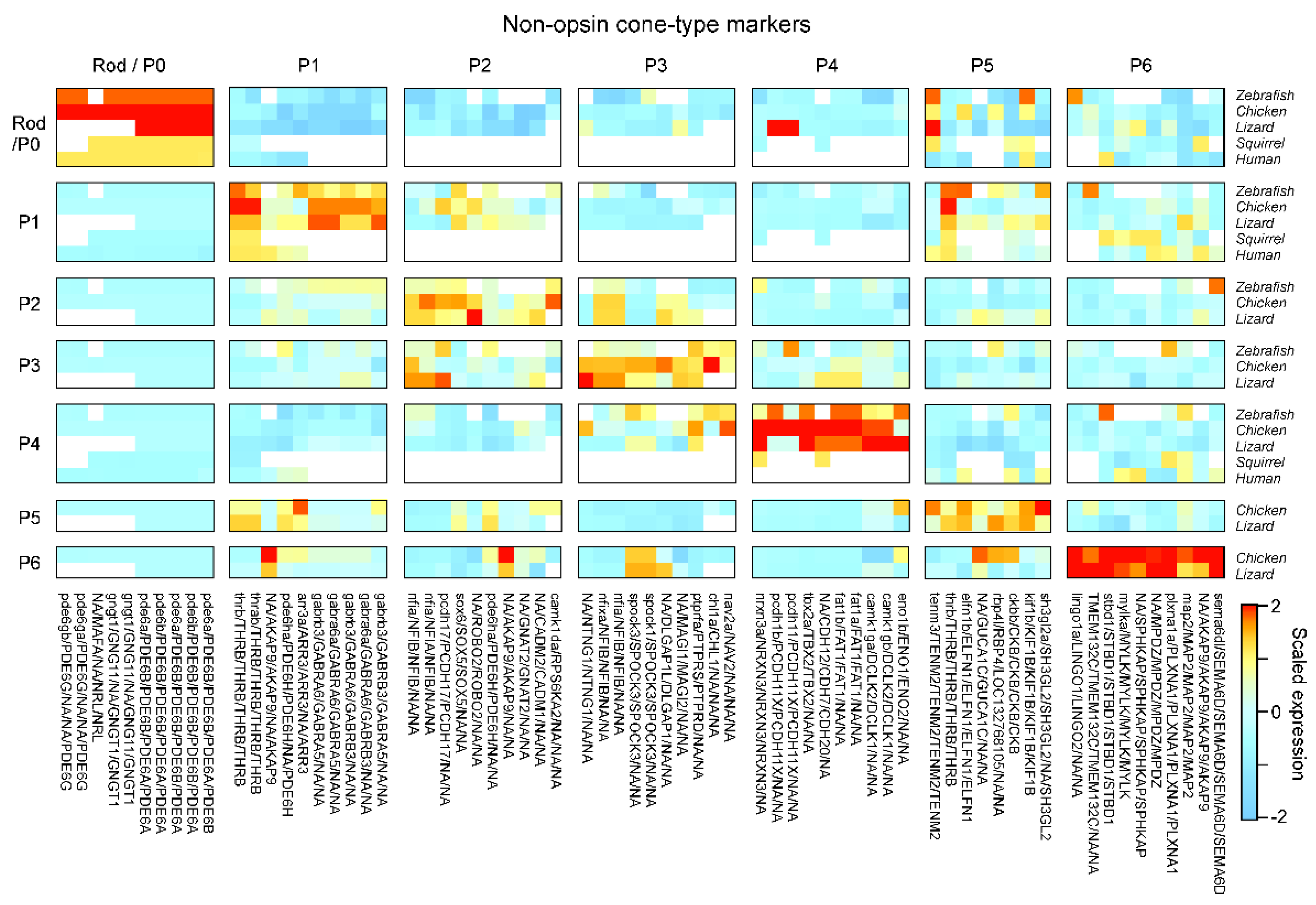

- Generation of P5 depends on THRB; and similar to P1, P5 also expresses SAMD7.

- P6 expresses FOXQ2 and SKOR1, similar to P3 and P3,4, respectively.

- Numerical abundance is usually P1≥P2>P3≥P4. If present, P5,6 is usually P1>P5/6>P4, except in birds, where the more typical pattern is P5/6>P1.

- If cone types are missing, the likely order of loss is P2=P3>P4>P1. In non-eutherian tetrapods, P5,6 is usually present. P5,6 are not known to occur individually.

- Postsynaptic wiring appears to conform to ‘spectral blocks’ in the sense that ‘intermediate’ cones, if present, do not tend to be skipped. For example, a bipolar cell is unlikely to connect with P1 and P3 without also contacting P2. In this order, rods and P5,6 appear to group with P1 (i.e., P0/P5,6-P1-P2-P3-P4). In birds, P6 appears to additionally group with P3 [45].

- The spectral appearance of pigmented oil droplets, if present, generally correlates with cone-type identity, with P1-P4 exhibiting long to short-wavelength filtering properties, respectively, matching the spectral sensitivity of the corresponding opsins. P4 usually has a clear oil droplet, devoid of light-absorbing carotenoid pigments. P5 tend to have spectrally intermediate oil droplets and P6 tend to have either absent or minute droplets, while frequently retaining carotenoid pigmentation in the mitochondrial aggregates of the ellipsoid13.

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baden, T.; Osorio, D. The Retinal Basis of Vertebrate Color Vision. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2019, 5, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, J.F.; Roberts, N.S.; Johnston, R.J. The evolutionary history and spectral tuning of vertebrate visual opsins. Dev. Biol. 2022, 493, 40–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M.; et al. Retinal twin cones or retinal double cones in fish: misnomer or different morphological forms? Int. J. Neurosci. 2005, 115, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, T. Ancestral photoreceptor diversity as the basis of visual behaviour. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, S.P.; Knight, M.A.; Davies, W.L.; Potter, I.C.; Hunt, D.M.; Trezise, A.E. Ancient colour vision: multiple opsin genes in the ancestral vertebrates. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, R864–R865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrington, R.E.; Davies, W.I.L.; Hemmi, J.M.; Hart, N.S.; Potter, I.C.; Collin, S.P.; Hunt, D.M. Visual opsin expression and morphological characterization of retinal photoreceptors in the pouched lamprey (Geotria australis, Gray). J. Comp. Neurol. 2020, 529, 2265–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kram, Y.A.; Mantey, S.; Corbo, J.C. Avian Cone Photoreceptors Tile the Retina as Five Independent, Self-Organizing Mosaics. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e8992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Hisatomi, O.; Sakakibara, S.; Tokunaga, F.; Tsukahara, Y. Distribution of blue-sensitive photoreceptors in amphibian retinas. FEBS Lett. 2001, 501, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baden, T. Circuit mechanisms for colour vision in zebrafish. 2021, 31, R807–R820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, M.; Baden, T.; Osorio, D. The retinal basis of vision in chicken. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 106, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.-R.; Shekhar, K.; Yan, W.; Herrmann, D.; Sappington, A.; Bryman, G.S.; van Zyl, T.; Do, M.T.H.; Regev, A.; Sanes, J.R. Molecular Classification and Comparative Taxonomics of Foveal and Peripheral Cells in Primate Retina. Cell 2019, 176, 1222–1237.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brainard, D.H. Color and the Cone Mosaic. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2015, 1, 519–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toomey, M.B.; Corbo, J.C. Evolution, Development and Function of Vertebrate Cone Oil Droplets. Front. Neural Circuits 2017, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, T.; Kojima, D.; Fukada, Y.; Shichida, Y.; Yoshizawa, T. Primary structures of chicken cone visual pigments: vertebrate rhodopsins have evolved out of cone visual pigments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992, 89, 5932–5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, S.; Yokoyama, R. ADAPTIVE EVOLUTION OF PHOTORECEPTORS AND VISUAL PIGMENTS IN VERTEBRATES. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1996, 27, 543–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowmaker, J.K. Evolution of vertebrate visual pigments. Vis. Res. 2008, 48, 2022–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasini, D.; Yoshimatsu, T.; Baden, T.; Shekhar, K. Comparative transcriptomic insights into the evolutionary origin of the tetrapod double cone. 2024, arXiv:2024.11.04.621990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, K. Cone Types and Cone Arrangements in Teleost Retinae1. Acta Zoöl. 1963, 44, 179–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyall, A.H. Cone Arrangements in Teleost Retinae. J. Cell Sci. 1957, S3-98, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, T. From water to land: Evolution of photoreceptor circuits for vision in air. PLOS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, M.; Yan, W.; Sanes, J.R.; Biology, C.; States, U. A cell atlas of the chick retina based on single-cell transcriptomics. eLife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, A.; Haverkamp, S.; Irsen, S.; Watkins, P.V.; Dedek, K.; Mouritsen, H.; Briggman, K.L. Species–specific circuitry of double cone photoreceptors in two avian retinas. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, A.; Dedek, K.; Haverkamp, S.; Irsen, S.; Briggman, K.L.; Mouritsen, H. Double Cones and the Diverse Connectivity of Photoreceptors and Bipolar Cells in an Avian Retina. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 5015–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelber, A. Bird colour vision – from cones to perception. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2019, 30, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H. What is a cell type and how to define it? Cell 2022, 185, 2739–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, J.; Jessen, Z.F.; Jacobi, A.; Mani, A.; Cooler, S.; Greer, D.; Kadri, S.; Segal, J.; Shekhar, K.; Sanes, J.R.; et al. Unified classification of mouse retinal ganglion cells using function, morphology, and gene expression. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111040–111040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Xu, Q.; Su, J.; Tang, L.; Hao, Z.-Z.; Xu, C.; Liu, R.; Shen, Y.; Sang, X.; Xu, N.; et al. Linking transcriptomes with morphological and functional phenotypes in mammalian retinal ganglion cells. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.A.; Mu, S.; Kim, J.S.; Turner, N.L.; Tartavull, I.; Kemnitz, N.; Jordan, C.S.; Norton, A.D.; Silversmith, W.M.; Prentki, R.; et al. Digital Museum of Retinal Ganglion Cells with Dense Anatomy and Physiology. Cell 2018, 173, 1293–1306.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baden, T.; Berens, P.; Franke, K.; Rosón, M.R.; Bethge, M.; Euler, T. The functional diversity of retinal ganglion cells in the mouse. Nature 2016, 529, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Avian photoreceptor homologies and the origin of double cones. Curr. Biol. 2025, in press.

- Rheaume, B.A.; Jereen, A.; Bolisetty, M.; Sajid, M.S.; Yang, Y.; Renna, K.; Sun, L.; Robson, P.; Trakhtenberg, E.F. Single cell transcriptome profiling of retinal ganglion cells identifies cellular subtypes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeley, P.W.; Eglen, S.J.; Reese, B.E. Author response for "From Random to Regular: Variation in the Patterning of Retinal Mosaics". 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wässle, H.; Puller, C.; Müller, F.; Haverkamp, S. Cone Contacts, Mosaics, and Territories of Bipolar Cells in the Mouse Retina. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, G.D.; Gauthier, J.L.; Sher, A.; Greschner, M.; Machado, T.A.; Jepson, L.H.; Shlens, J.; Gunning, D.E.; Mathieson, K.; Dabrowski, W.; et al. Functional connectivity in the retina at the resolution of photoreceptors. Nature 2010, 467, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmstaedter, M.; Briggman, K.L.; Turaga, S.C.; Jain, V.; Seung, H.S.; Denk, W. Connectomic reconstruction of the inner plexiform layer in the mouse retina. Nature 2013, 500, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, C.; Schubert, T.; Haverkamp, S.; Euler, T.; Berens, P. ; Germany Connectivity map of bipolar cells and photoreceptors in the mouse retina. eLife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, K.; Lapan, S.W.; Whitney, I.E.; Tran, N.M.; Macosko, E.Z.; Kowalczyk, M.; Adiconis, X.; Levin, J.Z.; Nemesh, J.; Goldman, M.; et al. Comprehensive Classification of Retinal Bipolar Neurons by Single-Cell Transcriptomics. Cell 2016, 166, 1308–1323.e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Laboulaye, M.A.; Tran, N.M.; Whitney, I.E.; Benhar, I.; Sanes, J.R. Mouse Retinal Cell Atlas: Molecular Identification of over Sixty Amacrine Cell Types. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 5177–5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, J.; Monavarfeshani, A.; Qiao, M.; Kao, A.H.; Kölsch, Y.; Kumar, A.; Kunze, V.P.; Rasys, A.M.; Richardson, R.; Wekselblatt, J.B.; et al. Evolution of neuronal cell classes and types in the vertebrate retina. Nature 2023, 624, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, K.; Berens, P.; Schubert, T.; Bethge, M.; Euler, T.; Baden, T. Inhibition decorrelates visual feature representations in the inner retina. Nature 2017, 542, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Santina, L.; Kuo, S.P.; Yoshimatsu, T.; Okawa, H.; Suzuki, S.C.; Hoon, M.; Tsuboyama, K.; Rieke, F.; Wong, R.O. Glutamatergic Monopolar Interneurons Provide a Novel Pathway of Excitation in the Mouse Retina. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 2070–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapot, C. A.; Euler, T. & Schubert, T. How do horizontal cells ‘talk’ to cone photoreceptors? Different levels of complexity at the cone-horizontal cell synapse. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 5495–5506. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Cavallini, M.; Pahlevan, A.; Sun, J.; Morshedian, A.; Fain, G.L.; Sampath, A.P.; Peng, Y.-R. Molecular characterization of the sea lamprey retina illuminates the evolutionary origin of retinal cell types. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimatsu, T.; Bartel, P.; Schröder, C.; Janiak, F.K.; St-Pierre, F.; Berens, P.; Baden, T. Ancestral circuits for vertebrate color vision emerge at the first retinal synapse. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, A.; et al. Morphology and connectivity of retinal horizontal cells in two avian species. 2025.01.27. 2025, arXiv:2025.01.27.634460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron Cowan, A.S.; Renner, M.; De Gennaro, M.; Roma, G.; Nigsch, F.; Roska Correspondence, B.; Cowan, C.S.; Gross-Scherf, B.; Goldblum, D.; Hou, Y.; et al. Cell Types of the Human Retina and Its Organoids at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell 2020, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, L.I.; Ogawa, Y.; Somjee, R.; Vedder, H.E.; Powell, H.E.; Poria, D.; Meiselman, S.; Kefalov, V.J.; Corbo, J.C. Samd7 represses short-wavelength cone genes to preserve long-wavelength cone and rod photoreceptor identity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angueyra, J.M.; Kunze, V.P.; Patak, L.K.; Kim, H.; Kindt, K.; Li, W.; Neurophysiology, U.O.R.; Function; Disorders, O. C.; States, U. Transcription factors underlying photoreceptor diversity. eLife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornetto, C.; Euler, T.; Baden, T. Vertebrate vision is ancestrally based on competing cone circuits. 2024.11.19. 2024, arXiv:2024.11.19.624320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, H.; Carroll, J.; Neitz, J.; Neitz, M.; Williams, D.R. Organization of the Human Trichromatic Cone Mosaic. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 9669–9679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applebury, M. L.; et al. The Murine Cone Photoreceptor: A Single Cone Type Expresses Both S and M Opsins with Retinal Spatial Patterning. Neuron 2000, 27, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, T.; Schubert, T.; Chang, L.; Wei, T.; Zaichuk, M.; Wissinger, B.; Euler, T. A Tale of Two Retinal Domains: Near-Optimal Sampling of Achromatic Contrasts in Natural Scenes through Asymmetric Photoreceptor Distribution. Neuron 2013, 80, 1206–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szél, Á.; Röhlich, P.; Gaffé, A.R.; Juliusson, B.; Aguirre, G.; Van Veen, T. Unique topographic separation of two spectral classes of cones in the mouse retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992, 325, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagman, D.; Callado-Pérez, A.; Franzén, I.E.; Larhammar, D.; Abalo, X.M. Transducin Duplicates in the Zebrafish Retina and Pineal Complex: Differential Specialisation after the Teleost Tetraploidisation. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0121330–e0121330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, M.; Roberts, P.A.; Kafetzis, G.; Osorio, D.; Baden, T. Birds multiplex spectral and temporal visual information via retinal On- and Off-channels. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-Y.; Hassin, G.; Witkovsky, P. Blue-sensitive rod input to bipolar and ganglion cells of theXenopus retina. Vis. Res. 1983, 23, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozenblit, F.; Gollisch, T. What the salamander eye has been telling the vision scientist's brain. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 106, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donner, K.; Yovanovich, C.A. A frog’s eye view: Foundational revelations and future promises. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 106, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Cowing, J.; A Arrese, C.; Davies, W.L.; Beazley, L.D.; Hunt, D.M. Cone visual pigments in two marsupial species: the fat-tailed dunnart (Sminthopsis crassicaudata) and the honey possum (Tarsipes rostratus). Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2008, 275, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauzman, E. Adaptations and evolutionary trajectories of the snake rod and cone photoreceptors. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 106, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.F. Studies on the retina of the gecko Coleonyx variegatus. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1966, 16, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, K.; Matsutani, Y.; Yanagawa, M.; Imamoto, Y.; Yamano, Y.; Wada, A.; Shichida, Y.; Yamashita, T. Evolutionary adaptation of visual pigments in geckos for their photic environment. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabj1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röll, B. Gecko vision—retinal organization, foveae and implications for binocular vision. Vis. Res. 2001, 41, 2043–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fain, G.L. Lamprey vision: Photoreceptors and organization of the retina. 2019, 106, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal-Nicolás, F.M.; Kunze, V.P.; Ball, J.M.; Peng, B.T.; Krishnan, A.; Zhou, G.; Dong, L.; Li, W.; Section, R.N.; States, U. True S-cones are concentrated in the ventral mouse retina and wired for color detection in the upper visual field. eLife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carleton, K.L.; Yourick, M.R. Axes of visual adaptation in the ecologically diverse family Cichlidae. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 106, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.L.; Gan, K.J.; Flamarique, I.N. Thyroid Hormone Induces a Time-Dependent Opsin Switch in the Retina of Salmonid Fishes. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 3024–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandamuri, S.P.; Yourick, M.R.; Carleton, K.L. Adult plasticity in African cichlids: Rapid changes in opsin expression in response to environmental light differences. Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 6036–6052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortesi, F.; Mitchell, L.J.; Tettamanti, V.; Fogg, L.G.; de Busserolles, F.; Cheney, K.L.; Marshall, N.J. Visual system diversity in coral reef fishes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 106, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frau, S.; Novales Flamarique, I.; Keeley, P.; Muñoz-Cueto, J. & Reese, B. Straying from the flatfish retinal plan: Cone photoreceptor patterning in the common sole (Solea solea) and the Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis). J. Comp. Neurol. 2020, 528. [Google Scholar]

- Arbogast, P.; Flamant, F.; Godement, P.; Glösmann, M. & Peichl, L. Thyroid Hormone Signaling in the Mouse Retina. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168003. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.R.; Srinivas, M.; Forrest, D.; de Escobar, G.M.; Reh, T.A. Making the gradient: Thyroid hormone regulates cone opsin expression in the developing mouse retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 6218–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, T. Thyroid hormone and seasonal regulation of reproduction. 2013, 34, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, B.E.; Lu, J.; Leips, J.; Cronin, T.W.; Carleton, K.L. Variable light environments induce plastic spectral tuning by regional opsin coexpression in the African cichlid fish, Metriaclima zebra. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 4193–4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshedian, A.; et al. Cambrian origin of the CYP27C1-mediated vitamin A1-to-A2 switch, a key mechanism of vertebrate sensory plasticity. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enright, J.M.; Toomey, M.B.; Sato, S.-Y.; Temple, S.E.; Allen, J.R.; Fujiwara, R.; Kramlinger, V.M.; Nagy, L.D.; Johnson, K.M.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Cyp27c1 Red-Shifts the Spectral Sensitivity of Photoreceptors by Converting Vitamin A1 into A2. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, 3048–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, K.L.; Escobar-Camacho, D.; Stieb, S.M.; Cortesi, F.; Marshall, N.J. Seeing the rainbow: mechanisms underlying spectral sensitivity in teleost fishes. J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.; et al. A heterogeneous population code at the first synapse of vision. 2024, arXiv:2024.05.03.592379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimatsu, T.; Schröder, C.; Nevala, N.E.; Berens, P.; Baden, T. Fovea-like Photoreceptor Specializations Underlie Single UV Cone Driven Prey-Capture Behavior in Zebrafish. Neuron 2020, 107, 320–337.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudin, J.; Angueyra, J.M.; Sinha, R.; Rieke, F.; States, U. S-cone photoreceptors in the primate retina are functionally distinct from L and M cones. eLife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.N.; Tsujimura, T.; Kawamura, S.; Dowling, J.E. Bipolar cell–photoreceptor connectivity in the zebrafish (Danio rerio) retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2012, 520, 3786–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.-Ather. & Anctil, Michel. Retinas of Fishes : An Atlas. Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 1976.

- Meier, A.; Nelson, R.; Connaughton, V.P. Color Processing in Zebrafish Retina. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stell, W.K.; Hárosi, F.I. Cone structure and visual pigment content in the retina of the goldfish. Vis. Res. 1976, 16, 647–IN4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, W.T.; Barthel, L.K.; Skebo, K.M.; Takechi, M.; Kawamura, S.; Raymond, P.A. Ontogeny of cone photoreceptor mosaics in zebrafish. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010, 518, 4182–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamarique, I.N.; Hawryshyn, C.W. No Evidence of Polarization Sensitivity in Freshwater Sunfish from Multi-unit Optic Nerve Recordings. Vis. Res. 1997, 37, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.J.; Nevala, N.E.; Yoshimatsu, T.; Osorio, D.; Nilsson, D.-E.; Berens, P.; Baden, T. Zebrafish Differentially Process Color across Visual Space to Match Natural Scenes. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 2018–2032.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shand, J.; Archer, M.A.; Collin, S.P. Ontogenetic changes in the retinal photoreceptor mosaic in a fish, the black bream,Acanthopagrus butcheri. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999, 412, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Corbo, J.C. Partitioning of gene expression among zebrafish photoreceptor subtypes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, O.; Chavez, J.; Kelber, A. The contribution of single and double cones to spectral sensitivity in budgerigars during changing light conditions. Journal of Comparative Physiology A 2013, 200, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, J.M.; Lawrence, K.A.; Hadzic, T.; Corbo, J.C. Transcriptome profiling of developing photoreceptor subtypes reveals candidate genes involved in avian photoreceptor diversification. J. Comp. Neurol. 2014, 523, 649–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, P.A.; Barthel, L.K. A moving wave patterns the cone photoreceptor mosaic array in the zebrafish retina. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2004, 48, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; et al. Conservation of cis-regulatory codes over half a billion years of evolution. 2024, arXiv:2024.11.13.623372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.J.V.; Pop, S.; Prieto-Godino, L.L. Evolution of central neural circuits: state of the art and perspectives. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 23, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaroop, A.; Kim, D.; Forrest, D. Transcriptional regulation of photoreceptor development and homeostasis in the mammalian retina. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; et al. Knockout of Nr2e3 prevents rod photoreceptor differentiation and leads to selective L-/M-cone photoreceptor degeneration in zebrafish. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, L.G.; Santon, J.B.; Glass, C.K.; Gill, G.N. Ligand-activated thyroid hormone and retinoic acid receptors inhibit growth factor receptor promoter expression. Cell 1990, 62, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.; Hurley, J.B.; Dierks, B.; Srinivas, M.; Saltó, C.; Vennström, B.; Reh, T.A.; Forrest, D. A thyroid hormone receptor that is required for the development of green cone photoreceptors. Nat. Genet. 2001, 27, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.C.; Bleckert, A.; Williams, P.R.; Takechi, M.; Kawamura, S.; Wong, R.O.L. Cone photoreceptor types in zebrafish are generated by symmetric terminal divisions of dedicated precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 15109–15114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Shiraki, T.; Asano, Y.; Muto, A.; Kawakami, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Kojima, D.; Fukada, Y. Six6 and Six7 coordinately regulate expression of middle-wavelength opsins in zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 4651–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Shiraki, T.; Kojima, D.; Fukada, Y. Homeobox transcription factor Six7 governs expression of green opsin genes in zebrafish. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20150659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Shiraki, T.; Fukada, Y.; Kojima, D. Foxq2 determines blue cone identity in zebrafish. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, A.; Yamamoto, A.; Yaguchi, J. & Yaguchi, S. cis-Regulatory analysis for later phase of anterior neuroectoderm-specific foxQ2 expression in sea urchin embryos. genesis 2019, 57, e23302. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, M.J.; Anderson, M.; Chang, E.; Wei, K.-J.; Kaul, R.; Graves, J.A.M.; Grützner, F.; Deeb, S.S. Cone visual pigments of monotremes: Filling the phylogenetic gap. Vis. Neurosci. 2008, 25, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, W.L.; Carvalho, L.S.; Cowing, J.A.; Beazley, L.D.; Hunt, D.M.; Arrese, C.A. Visual pigments of the platypus: A novel route to mammalian colour vision. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, R161–R163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Delfin, K.; Morris, A.C.; Snelson, C.D.; Gamse, J.T.; Gupta, T.; Marlow, F.L.; Mullins, M.C.; Burgess, H.A.; Granato, M.; Fadool, J.M. Tbx2b is required for ultraviolet photoreceptor cell specification during zebrafish retinal development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 2023–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).