Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

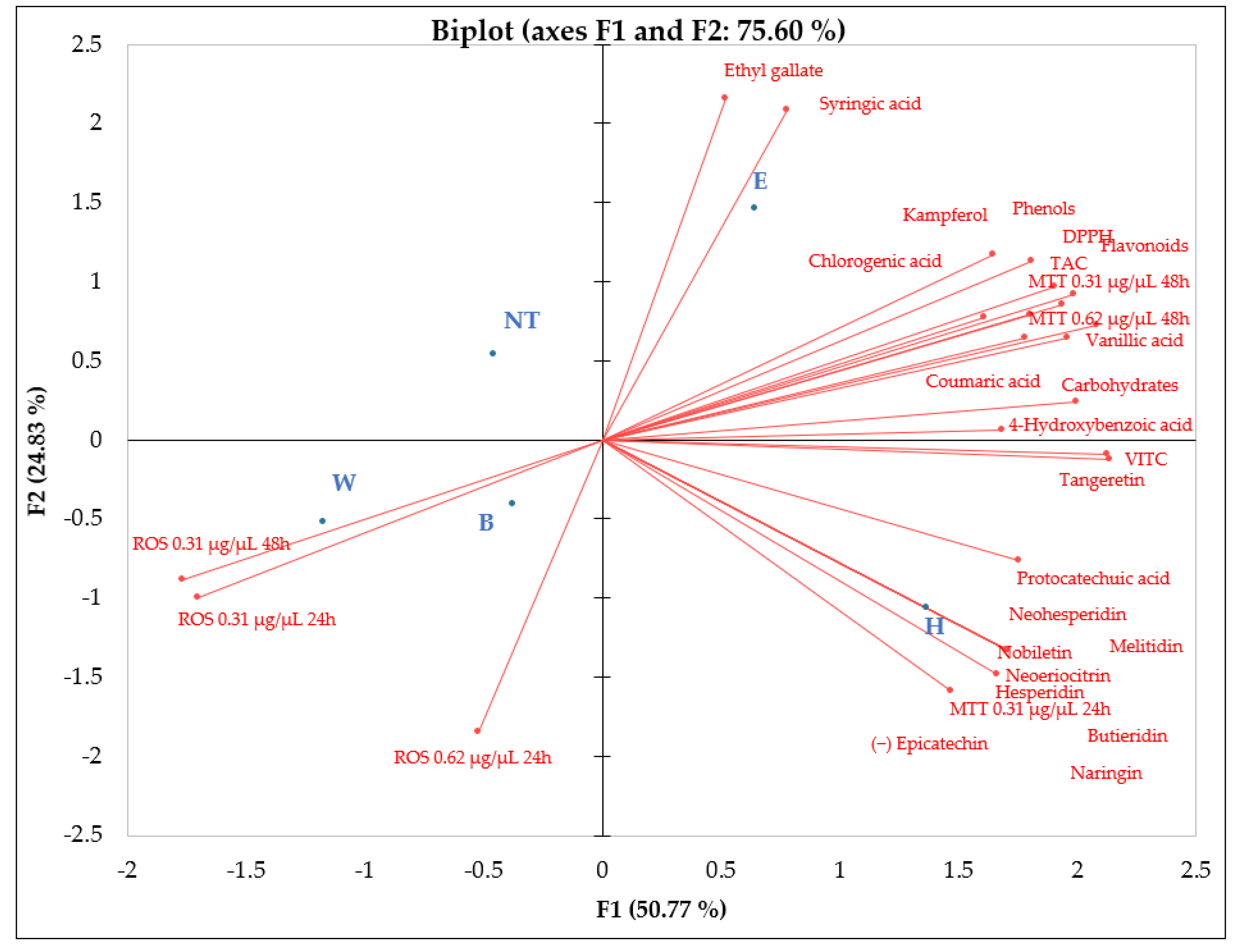

2. Results and Discussion

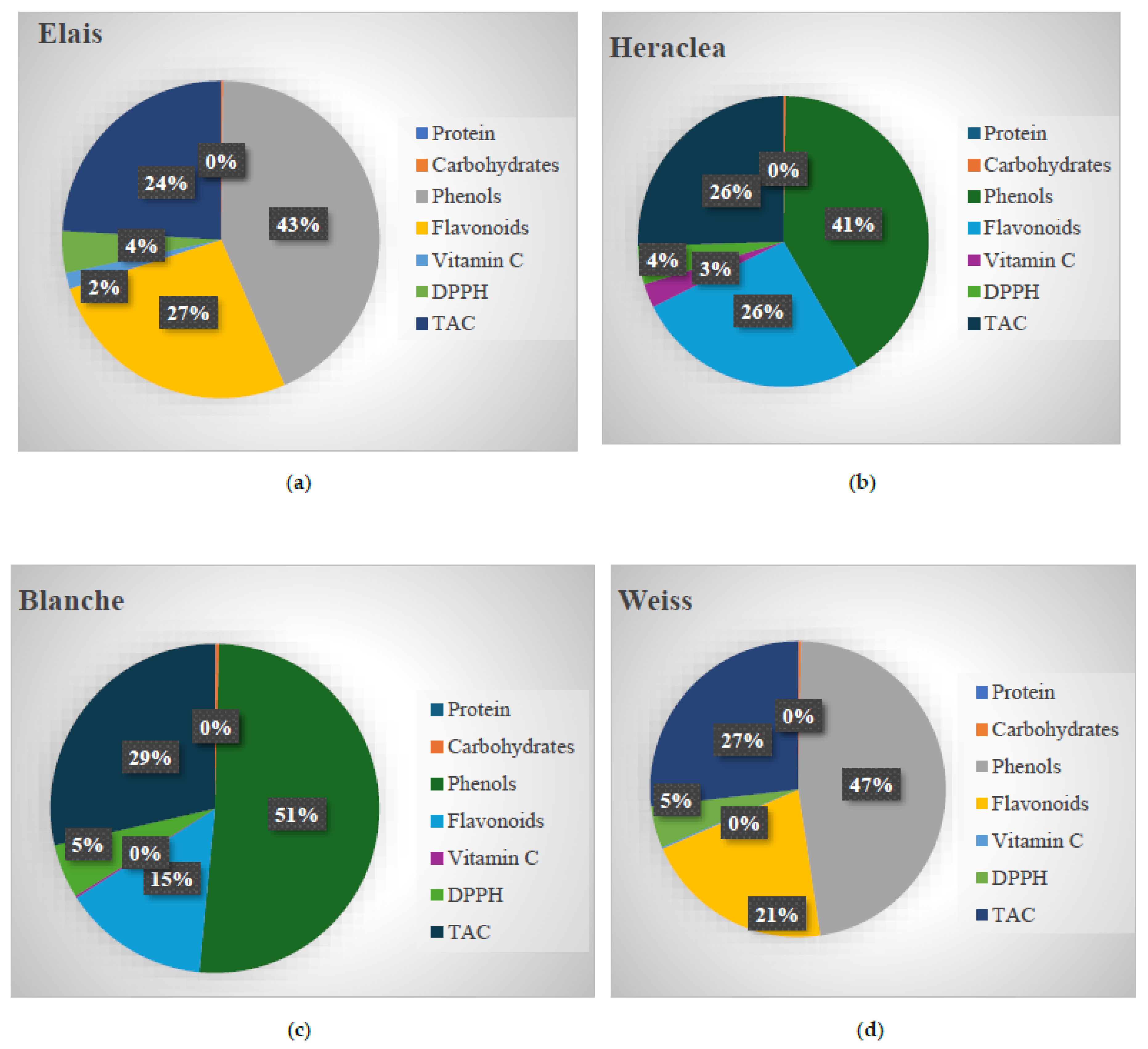

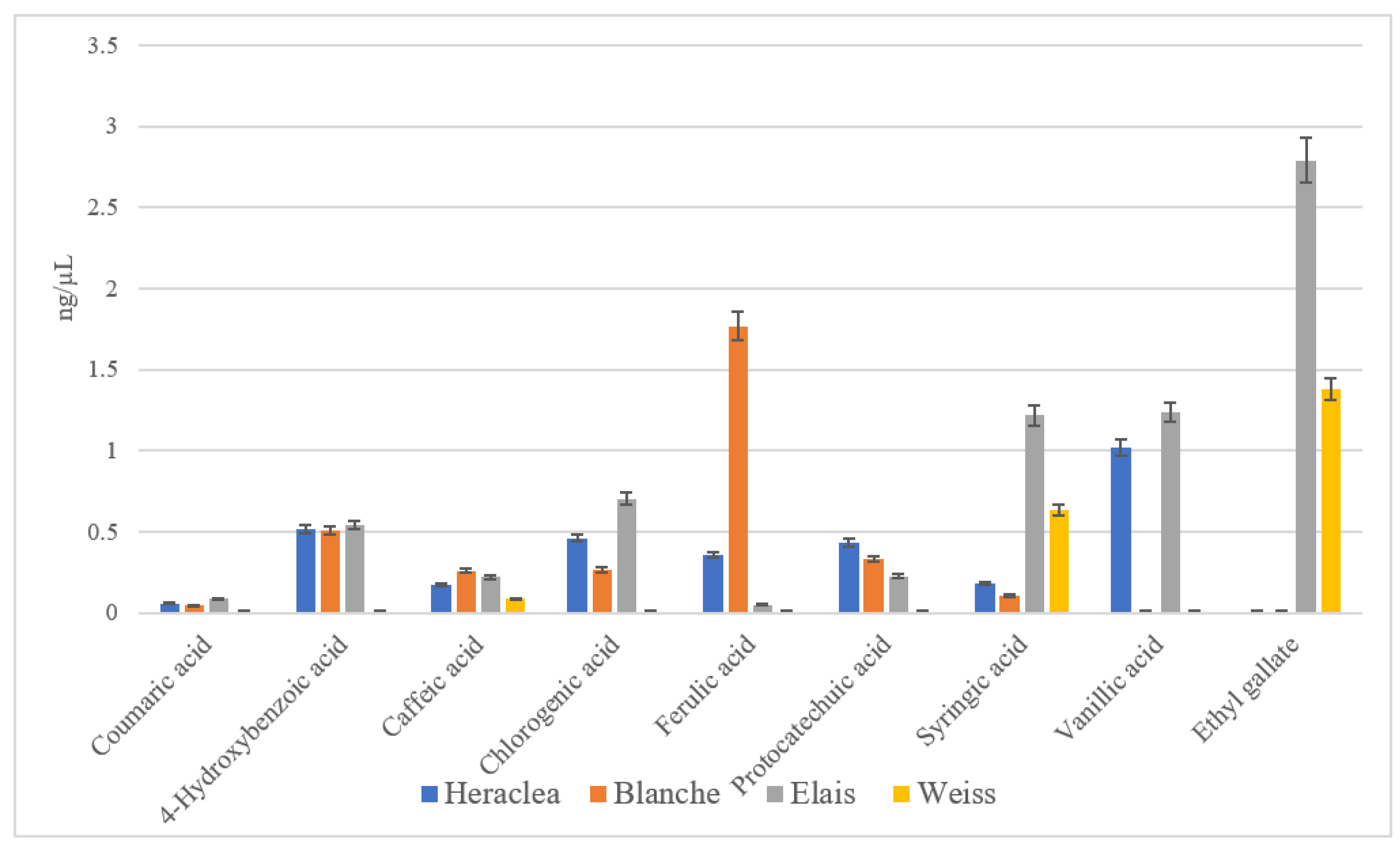

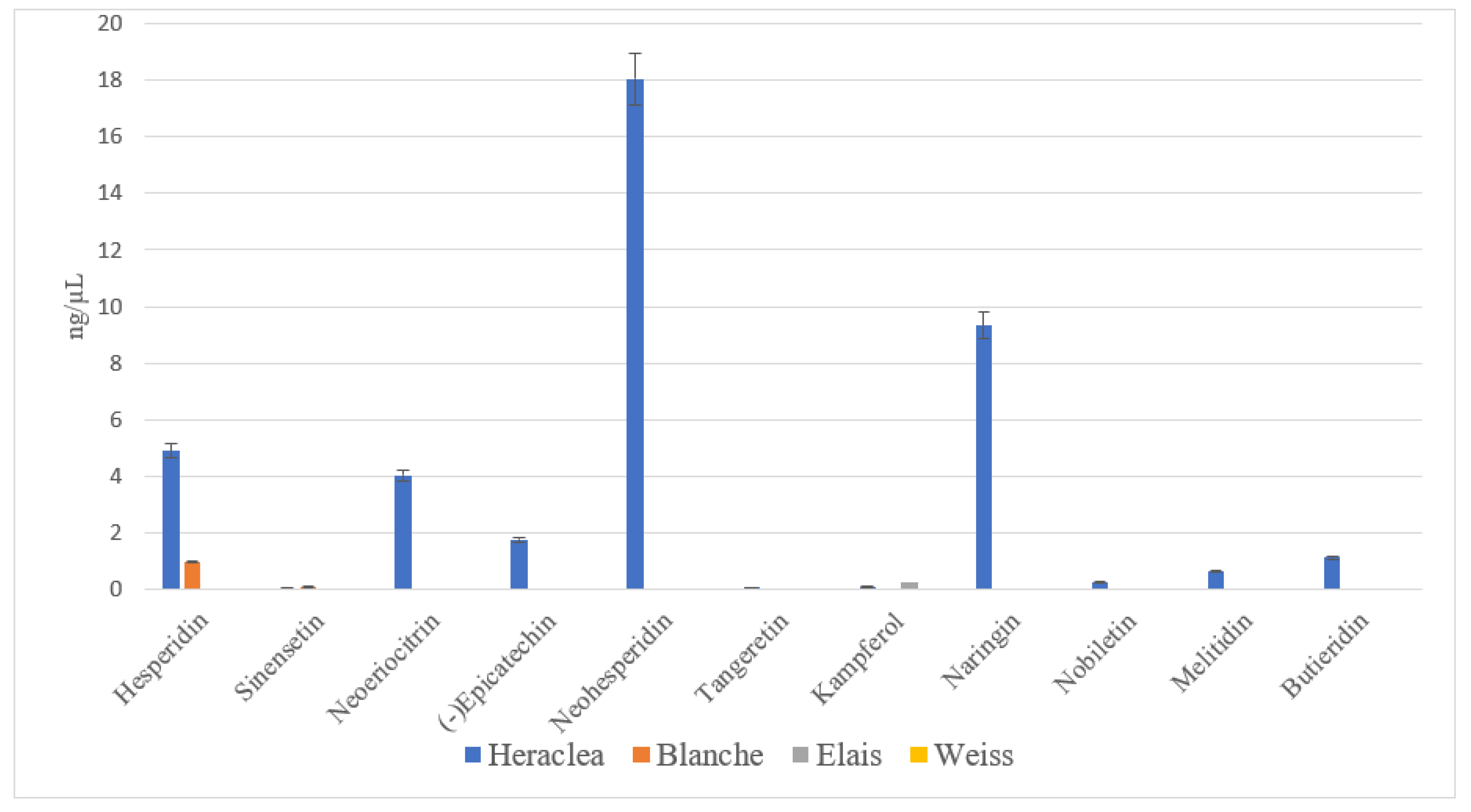

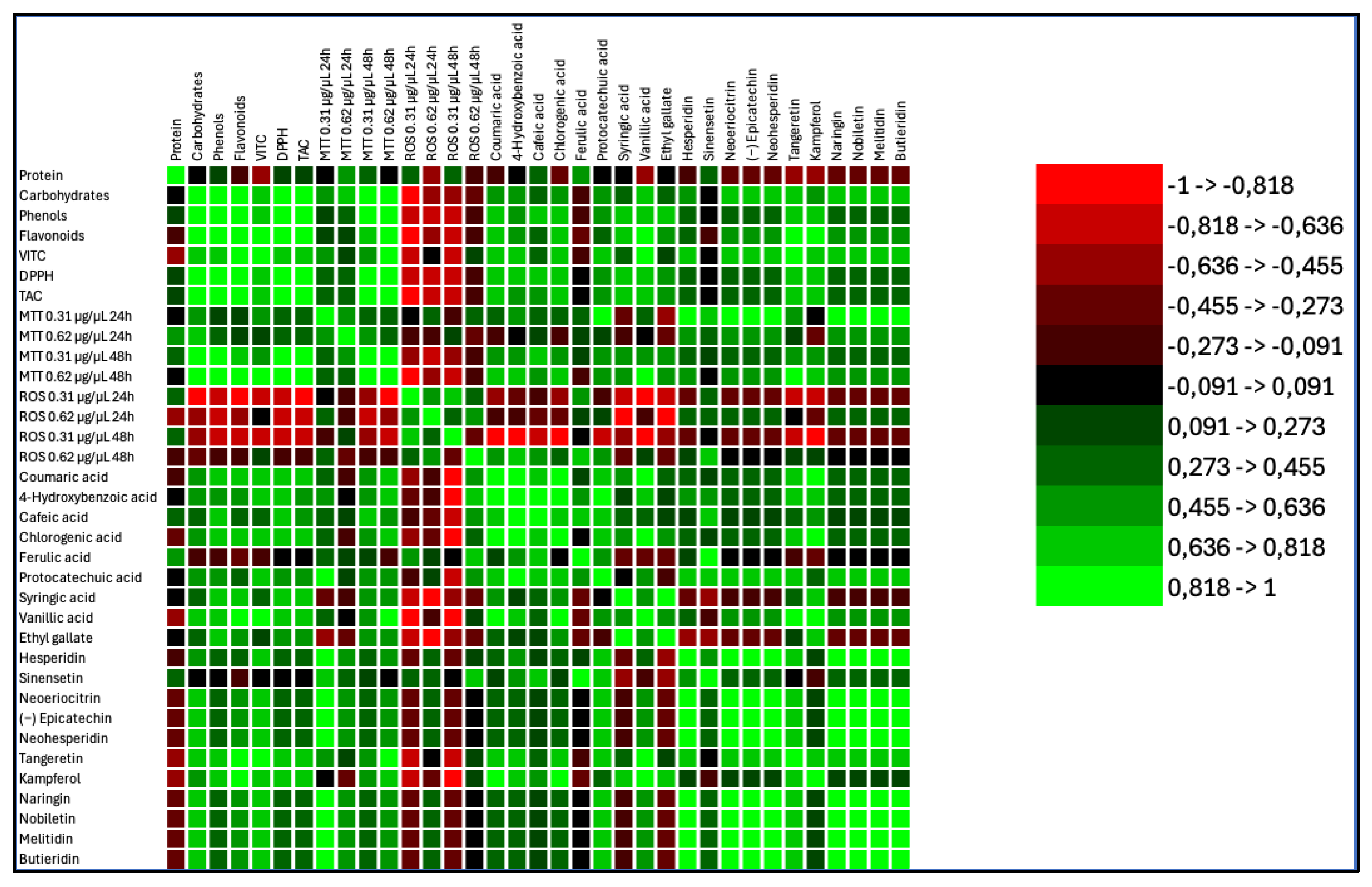

2.1. Effect of Antioxidant Compounds

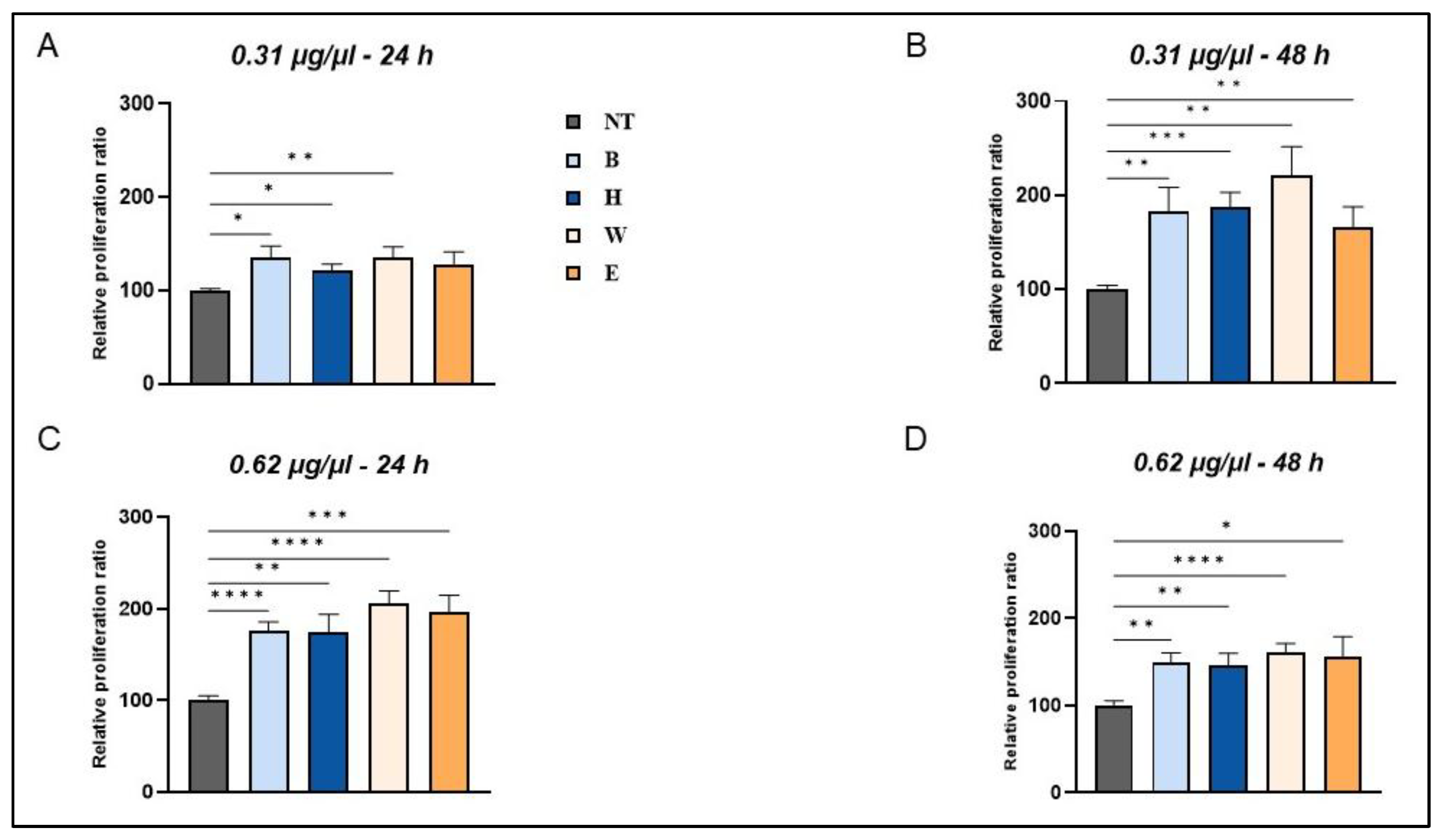

2.2. Effects of Lyophilized Beer Samples on Cell Viability

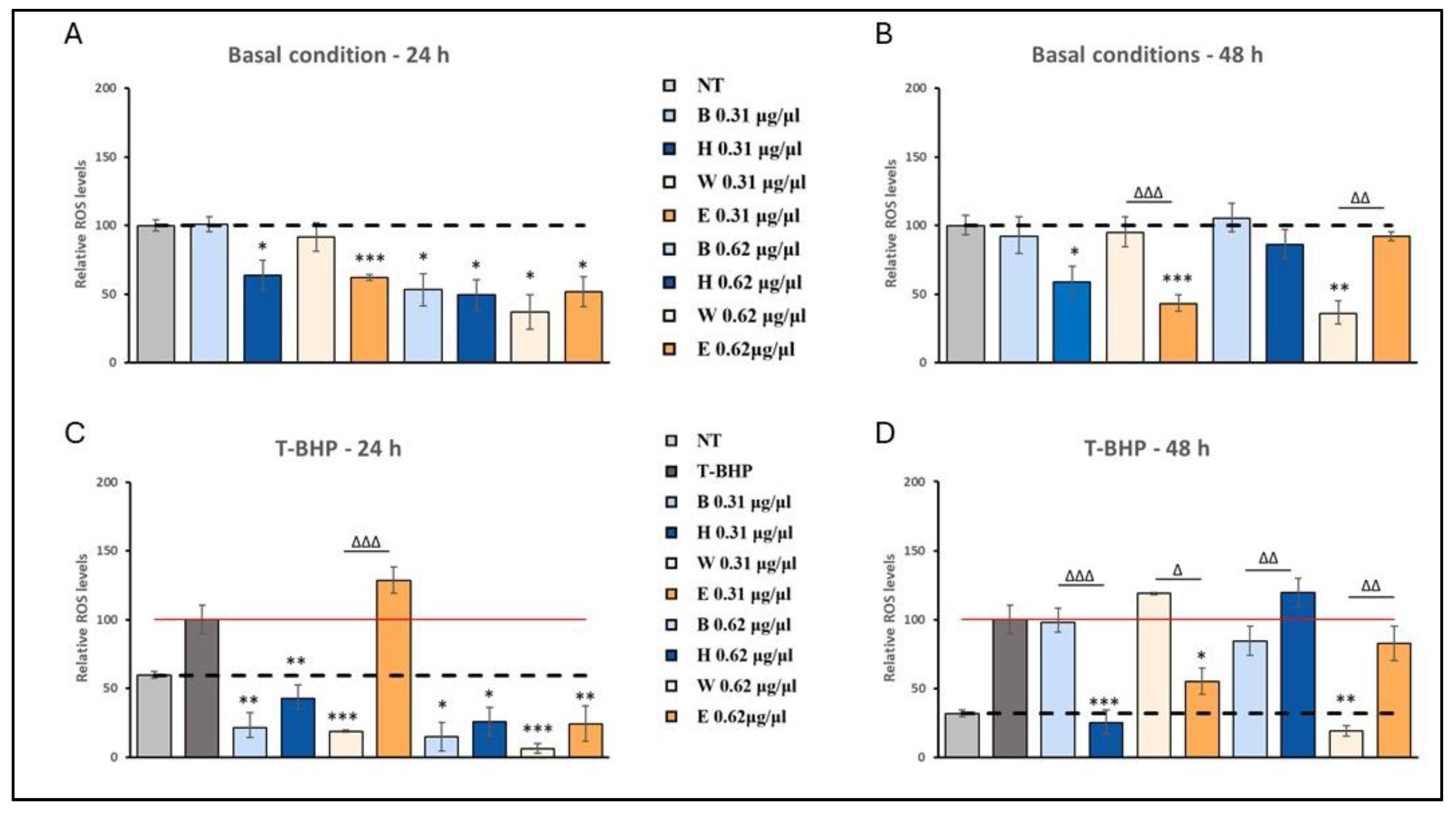

2.3. Effects of Lyophilized Beer Samples on Reactive Oxygen Species Level

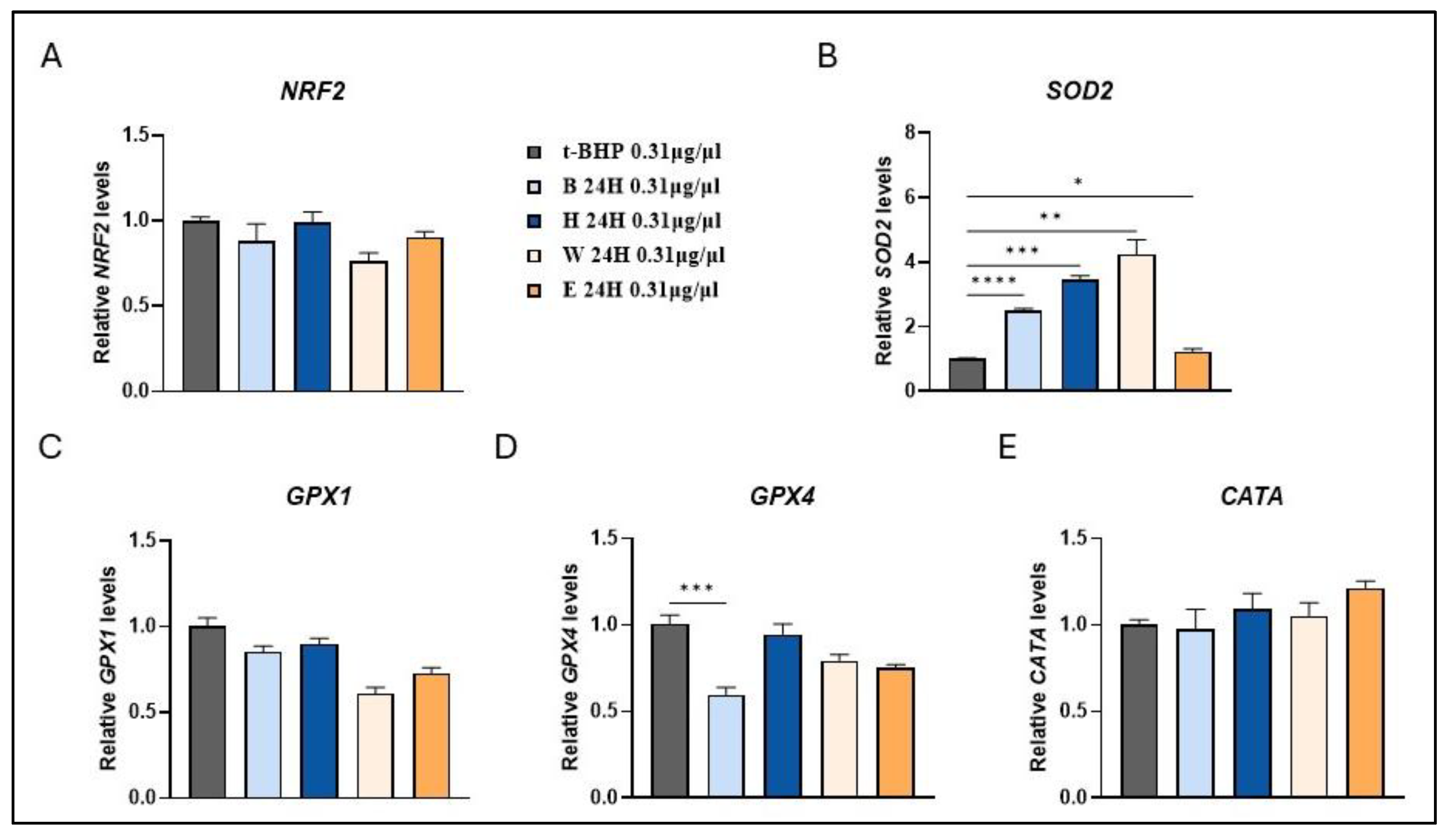

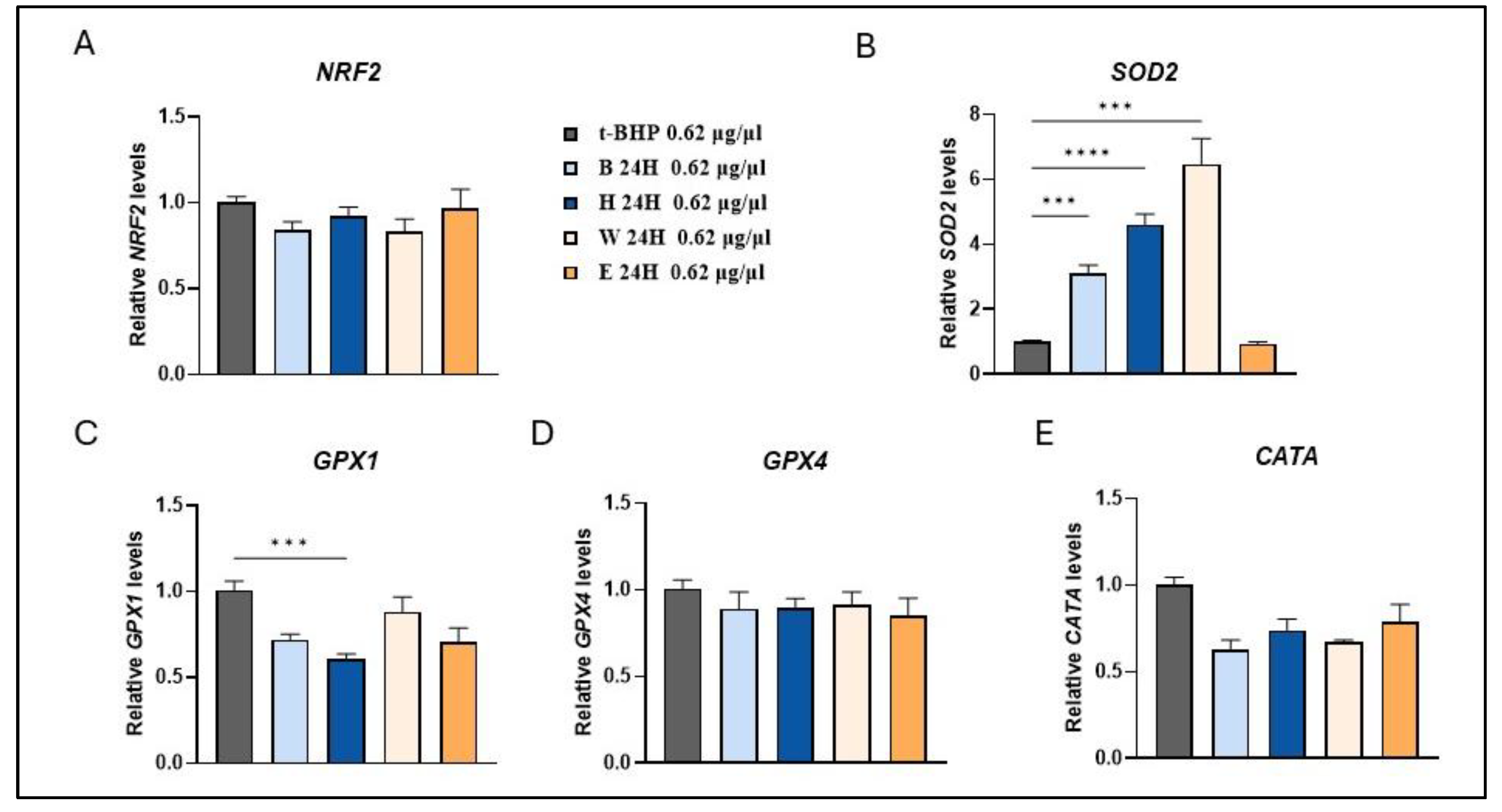

2.4. Effects of Lyophilized Beer Samples on RNA Levels of Antioxidant Enzymes

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Preparation

3.2. Determination of Antioxidant Compounds

3.2.1. Total Phenolic Content (TP)

3.2.2. Total Flavonoid Content (TF)

3.2.3. Total Carbohydrates and Ascorbic Acid Detection

3.2.4. Antioxidant Activity Assays

3.2.5. Polyphenolic Profile Determination

3.2.6. Validation Method for Polyphenols

3.3. Lyophilized Sample Preparation for Cell Culture Treatments

3.4. Cells and Culture Conditions

3.5. Cell Viability

3.6. Determination of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

3.7. RNA Isolation Reverse Transcription and Quantitative PCR

3.8. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poelmans, E.; Swinnen, J.F.M. 1 A brief economic history of beer. In Oxford University Press eBooks; 2011; pp 3–28. [CrossRef]

- Paiva, R. a. M.; Mutz, Y.S.; Conte-Junior, C.A. A review on the obtaining of functional beers by addition of Non-Cereal adjuncts rich in antioxidant compounds. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habschied, K.; Živković, A.; Krstanović, V.; Mastanjević, K. Functional Beer—A review on possibilities. Beverages 2020, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscolo, A.; Marra, F.; Salafia, F.; Andronaco, P.; Di Sanzo, R.; Carabetta, S.; Russo, Mt. Bergamot and olive extracts as beer ingredients: their influence on nutraceutical and sensory properties. European Food Research and Technology 2022, 248, 2067–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruca, N.G.; Laghetti, N.G.; Mafrica, N.R.; Turiano, N.D.; Hammer, N.K. The Fascinating History of Bergamot (Citrus Bergamia Risso & Poiteau), The Exclusive Essence of Calabria: a review. Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering - A 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattuso, A.; Mafrica, R.; Cannavò, S.; Mafrica, D.; De Bruno, A.; Poiana, M. Quality evaluation of bergamot juice produced in different areas of Calabria region. Foods 2024, 13, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorisio, S.; Muscari, I.; Fierabracci, A.; Thuy, T.T.; Marchetti, M.C.; Ayroldi, E.; Delfino, D.V. Biological effects of bergamot and its potential therapeutic use as an anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer agent. Pharmaceutical Biology 2023, 61, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Arigò, A.; Calabrò, M.L.; Farnetti, S.; Mondello, L.; Dugo, P. Bergamot ( Citrus bergamia Risso ) as a source of nutraceuticals: Limonoids and flavonoids. Journal of Functional Foods 2015, 20, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, I.; Alghamdi, S.; Rajab, B.S.; Babalghith, A.O.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Islam, S.; Islam, Md. R. Flavonoids a Bioactive Com-pound from Medicinal Plants and Its Therapeutic Applications. BioMed Research International 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maria, G.A.; Riccardo, N. Citrus bergamia, Risso: the peel, the juice and the seed oil of the bergamot fruit of Reggio Calabria (South Italy). Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture 2020, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzynik-Debicka, M.; Przychodzen, P.; Cappello, F.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Gammazza, A.M.; Knap, N.; Wozniak, M.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M. Potential health benefits of olive oil and plant polyphenols. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullo, M.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.; Salas-Salvado, J. Mediterranean diet and oxidation: Nuts and olive oil as important sources of fat and antioxidants. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 2011, 11, 1797–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selim, S.; Albqmi, M.; Al-Sanea, M.M.; Alnusaire, T.S.; Almuhayawi, M.S.; AbdElgawad, H.; Jaouni, S.K.A.; Elkelish, A.; Hussein, S.; Warrad, M.; El-Saadony, M.T. Valorizing the usage of olive leaves, bioactive compounds, biological activities, and food applications: A comprehensive review. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruno, A.; Zappia, A.; Piscopo, A.; Poiana, M. Qualitative evaluation of fermented olives grown in Southern Italy (cvs. Carolea, Grossa of Gerace and Nocellara Messinese). Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture 2019, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychoudhury, S.; Sinha, B.; Choudhury, B.P.; Jha, N.K.; Palit, P.; Kundu, S.; Mandal, S.C.; Kolesarova, A.; Yousef, M.I.; Ruokolainen, J.; Slama, P.; Kesari, K.K. Scavenging properties of Plant-Derived natural biomolecule Para-Coumaric acid in the prevention of oxidative Stress-Induced diseases. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.J.; Prince, P.S.M. Preventive effects of p-coumaric acid on cardiac hypertrophy and alterations in electrocardiogram, lipids, and lipoproteins in experimentally induced myocardial infarcted rats. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 60, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehami, W.; Nani, A.; Khan, N.A.; Hichami, A. New insights into the anticancer effects of P-Coumaric acid: Focus on colorectal cancer. Dose-Response 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziółkiewicz, A.; Kasprzak-Drozd, K.; Rusinek, R.; Markut-Miotła, E.; Oniszczuk, A. The influence of polyphenols on atherosclerosis development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Sharma, A.; Iqbal, M.S.; Srivastava, J.K. Therapeutic Promises of Chlorogenic Acid with Special Emphasis on its Anti-Obesity Property. Current Molecular Pharmacology 2019, 13, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, I.; Mandryk, I.; Horbańczuk, J.O.; Wierzbicka, A.; Koszarska, M. Nutraceutical Properties of Syringic Acid in Civilization Diseases—Review. Nutrients 2023, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotes, J.; Kasian, K.; Jacobs, H.; Cheng, Z.-Q.; Mink, S.N. Benefits of ethyl gallate versus norepinephrine in the treatment of cardiovascular collapse in Pseudomonas aeruginosa septic shock in dogs*. Critical Care Medicine 2011, 40, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Paz, I.; Valle-Jiménez, X.; Brunauer, R.; Alavez, S. Vanillic Acid Improves Stress Resistance and Substantially Extends Life Span in Caenorhabditis elegans. The Journals of Gerontology Series A 2023, 78, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; He, Y.; Luo, C.; Feng, B.; Ran, F.; Xu, H.; Ci, Z.; Xu, R.; Han, L.; Zhang, D. New progress in the pharmacology of protocatechuic acid: A compound ingested in daily foods and herbs frequently and heavily. Pharmacological Research 2020, 161, 105109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Munir, S.; Badshah, S.L.; Khan, N.; Ghani, L.; Poulson, B.G.; Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, M. Important flavonoids and their role as a therapeutic agent. Molecules 2020, 25, 5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopoldini, M.; Malaj, N.; Toscano, M.; Sindona, G.; Russo, N. On the Inhibitor Effects of Bergamot Juice Flavonoids Binding to the 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase (HMGR) Enzyme. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2010, 58, 10768–10773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Tocmo, R.; Nauman, M.C.; Haughan, M.A.; Johnson, J.J. Defining the Cholesterol Lowering Mechanism of Bergamot (Citrus bergamia) Extract in HepG2 and Caco-2 Cells. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrella, M.L.; Valletti, A.; Marra, F.; Mallamaci, C.; Cocco, T.; Muscolo, A. Phytochemicals from Red Onion, Grown with Eco-Sustainable Fertilizers, Protect Mammalian Cells from Oxidative Stress, Increasing Their Viability. Molecules 2022, 27, 6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebadi, P.; Fazeli, M. Evaluation of the potential in vitro effects of propolis and honey on wound healing in human dermal fibroblast cells. South African Journal of Botany 2021, 137, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatullo, M.; Simone, G.M.; Tarullo, F.; et al. Antioxidant and antitumor activity of a bioactive polyphenolic fraction isolated from the brewing process. Scientific Reports. 2016, 6, 36042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardini, M. An Overview of Bioactive Phenolic Molecules and Antioxidant Properties of Beer: Emerging Trends. Molecules. 2023, 28, 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A.B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights Into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 806470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, H.; Schuck, A.G.; Weisburg, J.H.; Zuckerbraun, H.L. (2011). Research Strategies in the Study of the Pro-oxidant Nature of Polyphenol Nutraceuticals. J. Toxicol 2011, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivonne, M.C.M. 33. Ivonne M.C.M. Rietjens, Marelle G. Boersma, Laura de Haan, Bert Spenkelink, Hanem M. Awad, Nicole H.P. Cnubben, Jelmer J. van Zanden, Hester van der Woude, Gerrit M. Alink, Jan H. Koeman, The pro-oxidant chemistry of the natural antioxidants vitamin C, vitamin E, carotenoids and flavonoids. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2002, 11, 321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Eghbaliferiz, S.; Iranshahi, M. Prooxidant Activity of Polyphenols, Flavonoids, Anthocyanins and Carotenoids: Updated Review of Mechanisms and Catalyzing Metals. Phytother Res. 2016, 30, 1379–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecci, R.M.; D'Antuono, I.; Cardinali, A.; Garbetta, A.; Linsalata, V.; Logrieco, A.F.; Leone, A. Antioxidant and Pro-Oxidant Capacities as Mechanisms of Photoprotection of Olive Polyphenols on UVA-Damaged Human Keratinocytes. Molecules. 2021, 26, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Luo, G.; Giannelli, S.; Szeto, H.H. Mitochondria-targeted peptide prevents mitochondrial depolarization and apoptosis induced by tert-butyl hydroperoxide in neuronal cell lines. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005, 70, 1796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; et al. Several lines of antioxidant defense against oxidative stress: antioxidant enzymes, nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch Toxicol 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marzo, N.; Chisci, E.; Giovannoni, R. The Role of Hydrogen Peroxide in Redox-Dependent Signaling: Homeostatic and Pathological Responses in Mammalian Cells. Cells. 2018, 7, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmijewski, J.W.; Banerjee, S.; Bae, H.; Friggeri, A.; Lazarowski, E.R.; Abraham, E. Exposure to hydrogen peroxide induces oxidation and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2010, 285, 33154–33164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auciello, F.R.; Ross, F.A.; Ikematsu, N.; Hardie, D.G. Oxidative stress activates AMPK in cultured cells primarily by increasing cellular AMP and/or ADP. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 3361–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.M. Regulation and function of AMPK in physiology and diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2016, 48, e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Yang, M.H.; Wen, H.M.; Chern, J.C. Estimation of total favonoid content in propolis by two complementary colorimetric methods. J Food Drug Anal 2002, 10, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Muscolo, A.; Calderaro, A.; Papalia, T.; Settineri, G.; Mallamaci, C.; Panuccio, M.R. Soil salinity improves nutritional and health promoting compounds in three varieties of lentil (Lens culinaris Med.). Food Bioscience 2020, 35, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalia, T.; Barreca, D.; Panuccio, M. Assessment of Antioxidant and Cytoprotective Potential of Jatropha (Jatropha curcas) Grown in Southern Italy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacelli, C.; De Rasmo, D.; Signorile, A.; Grattagliano, I.; Di Tullio, G.; D’Orazio, A.; Nico, B.; Pietro Comi, G.; Ronchi, D.; Ferranini, E.; Pirolo, D.; Seibel, P.; Schubert, S.; Gaballo, A.; Villani, G.; Cocco, T. Mitochondrial defect and PGC-1α dysfunction in parkin-associated familial Parkinson’s disease. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2011, 1812, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, D.; Gaballo, A.; Signorile, A.; Ferretta, A.; Tanzarella, P.; Pacelli, C.; Di Paola, M.; Cocco, T.; Maffia, M. Resveratrol Modulation of protein expression in parkin-Mutant human skin fibroblasts: A proteomic approach. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanzarella, P.; Ferretta, A.; Barile, S.N.; Ancona, M.; De Rasmo, D.; Signorile, A.; Papa, S.; Capitanio, N.; Pacelli, C.; Cocco, T. Increased levels of CAMP by the Calcium-Dependent activation of soluble adenylyl cyclase in Parkin-Mutant fibroblasts. Cells 2019, 8, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Loosdrecht, A.A.; Beelen, R.H.J.; Ossenkoppele, G.J.; Broekhoven, M.G.; Langenhuijsen, M.M.A.C. A tetrazolium-based colorimetric MTT assay to quantitate human monocyte mediated cytotoxicity against leukemic cells from cell lines and patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Journal of Immunological Methods 1994, 174, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compounds | Rt | ±SD | RSD% | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coumaric acid | 12.396 | 0.008 | 0.496 | 102.1 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 4.060 | 0.014 | 1.310 | 103.8 |

| Caffeic acid | 7.751 | 0.011 | 0.601 | 102.0 |

| Ethylgallate | 9.836 | 0.020 | 1.396 | 102.7 |

| Ferulic acid | 11.323 | 0.007 | 0.258 | 101.9 |

| Kampferol | 18.551 | 0.014 | 0.767 | 100.8 |

| Protocatechuic acid | 2.157 | 0.009 | 0.769 | 102.3 |

| Syringic acid | 8.996 | 0.008 | 0.283 | 97.3 |

| Vanillic acid | 7.344 | 0.015 | 1.172 | 95.9 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 8.637 | 0.015 | 0.837 | 95.9 |

| Naringin | 14.125 | 0.010 | 0.358 | 93.2 |

| Hesperidin | 14.531 | 0.007 | 0.321 | 95.8 |

| Sinensetin | 21.488 | 0.006 | 0.385 | 108.2 |

| Neoeriocitrin | 12.986 | 0.011 | 0.772 | 95.1 |

| (-)Epicatechin | 9.880 | 0.013 | 0.868 | 93.9 |

| Neohesperidin | 14.925 | 0.042 | 0.604 | 100.8 |

| Tangeretin | 23.290 | 0.019 | 0.964 | 104.4 |

| Melitidin | 11.422 | 0.009 | 0.655 | 102.8 |

| Nobiletin | 22.432 | 0.006 | 0.077 | 99.7 |

| Butieridin | 11.611 | 0.011 | 0.101 | 99.6 |

| Gene | Forward Primer Sequence | Reverse Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| NRF2 | 5'-AGCCCAGCACATCCAGTCA-3' | 5'-TGTGGGCAACCTGGGAGTAG-3' |

| SOD2 | 5'-CTGGACAAACCTCAGCCCT-3' | 5'-CTGATTTGGACAAGCAGCAA-3' |

| GPX1 | 5'-AGAACGCCAAGAAGCAGAAGA-3' | 5'-CATGAAGTTGGGCTCGAACC-3' |

| GPX4 | 5'-AACTACACTCAGCTGCTGC-3' | 5'-GCAGGTCTTCTCTCATCACC-3' |

| CATA | 5'-TGGAAAGAAGACTCCCATCG-3' | 5'-CCAGAGATCCCAGACCATGT-3' |

| GAPDH | 5'-CAACTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGGAC-3' | 5'-ACAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTG-3' |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).