Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction:

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

- 1)

- Diagnosis of acute type 1 MI with rise and/or fall of troponin, and

- 2)

- Angiographic culprit with intervention, and

- 3)

-

One of the following:

- A)

- TIMI 0-2 flow, or

- B)

-

TIMI-3 flow or unknown flow with large acute infarct size, as determined by one of the following:

- i)

-

Very elevated troponin defined as

- a)

- peak high sensitivity troponin-I level > 5000 ng/L

- b)

- peak 4th generation troponin I > 10 ng/mL,

- c)

- peak high sensitivity troponin T > 1000 ng/L, or

- d)

- peak 4th generation troponin T > 1.0 ng/mL.

- ii)

- New regional wall motion abnormality (WMA) on echocardiography if peak troponin levels were not available or were below the very high threshold.

2.2. Data Elements

2.3. Artificial Intelligence Algorithm

2.4. Primary Outcome

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

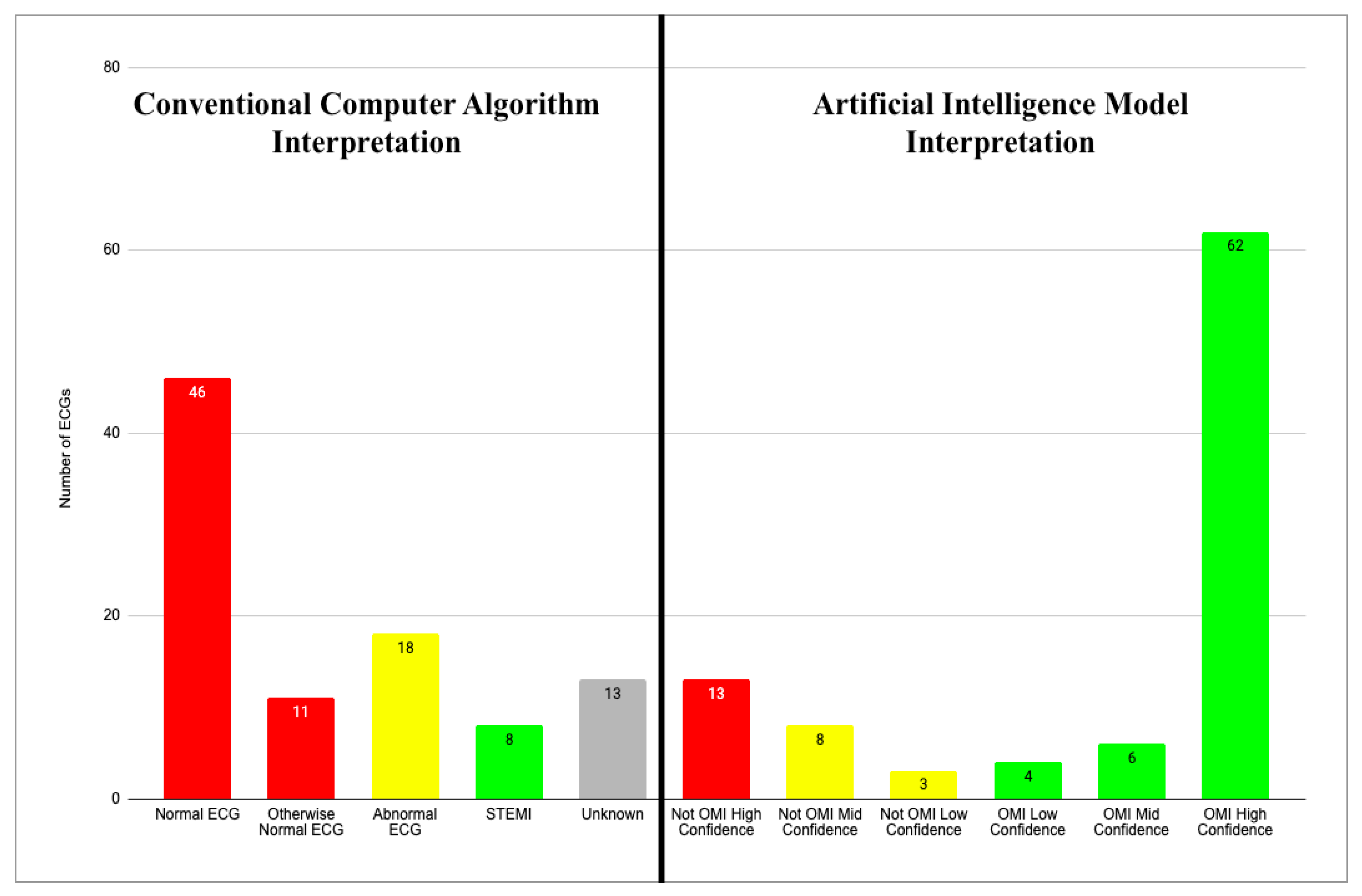

3.2. CCA Interpretations of the Initial ECG

3.3. AI Interpretations of the Initial ECG

3.4. Per-ECG Diagnostic Performance

4.5. AI Performance with CCA “Normal” ECGs

3.6. CCA vs AI, Case by Case

- Cases in which both the CCA and the AI system diagnosed acute MI.

- Cases in which the CCA did not diagnose acute MI but the AI system did.

- Cases in which neither the CCA nor the AI system diagnosed acute MI.

- Cases in which the CCA diagnosed MI but the AI system did not.

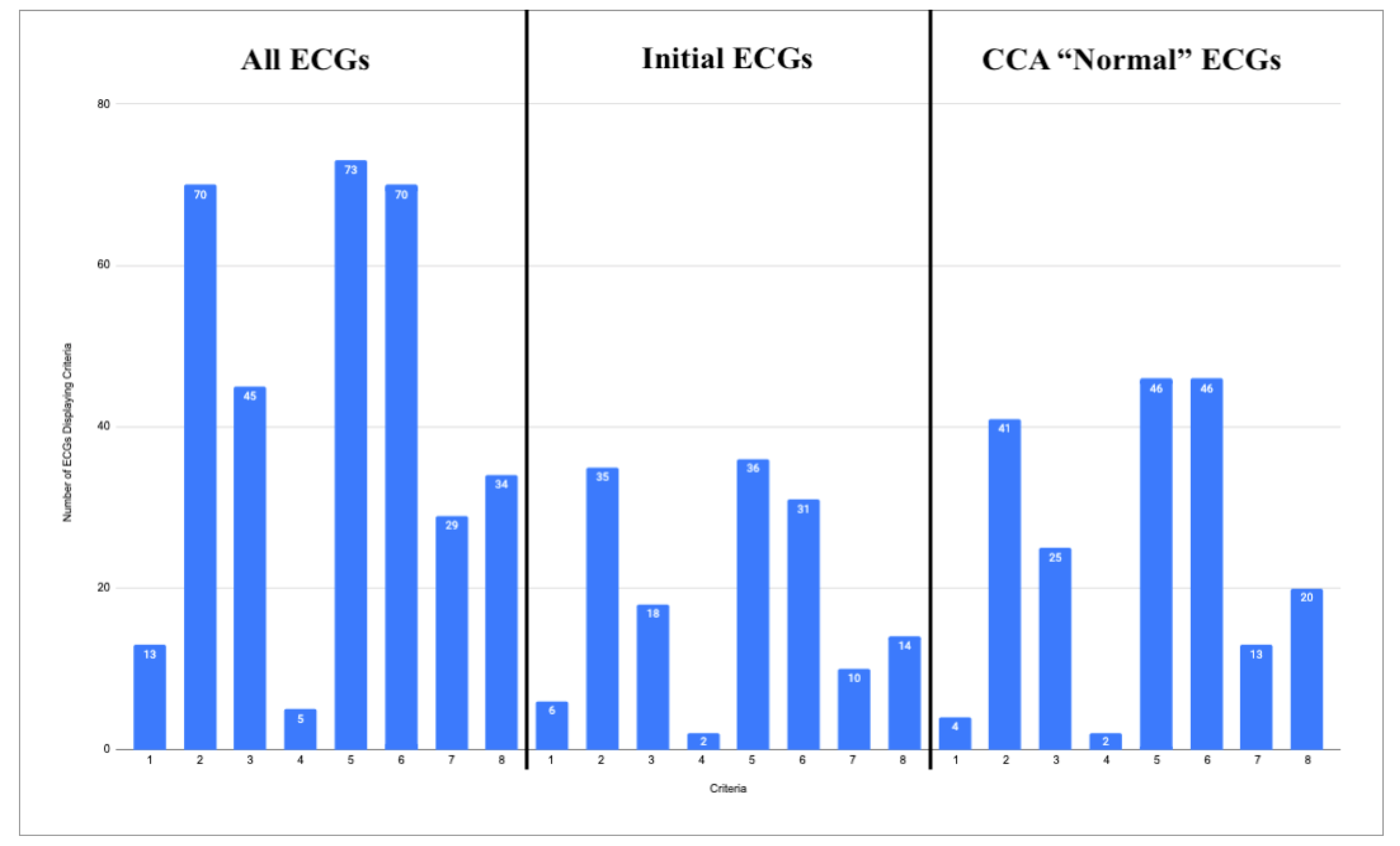

4. Common ECG Features

- STEMI criteria

- Hyperacute T waves

- Pathologic Q waves with ST elevation

- Terminal QRS Distortion

- Reciprocal changes, including ST depression, T wave inversion, horizontal ST segment flattening, or down-up T waves

- Subtle ST elevation

- Any amount of ST depression in V1-V4

- Any inferior ST elevation with any reciprocal change

5. Culprit Artery Analysis

| Culprit Artery | Number of Cases |

|---|---|

| LAD | 18 |

| Diagonal | 4 |

| Circumflex | 2 |

| Obtuse Marginal | 7 |

| RCA | 12 |

| PDA | 2 |

| Ramus | 1 |

6. Discussion

7. Limitations

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest Disclosures

References

- Writing Committee, Kontos MC, de Lemos JA, et al. 2022 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the evaluation and disposition of acute chest pain in the emergency department: A report of the American college of cardiology solution set oversight committee. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet] 2022;80(20):1925–60. Available from: https://www.jacc.org/doi/abs/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.08.

- McLaren J, de Alencar JN, Aslanger EK, Pendell Meyers H, Smith SW. From ST-Segment Elevation MI to Occlusion MI: The New Paradigm Shift in Acute Myocardial Infarction. 2024;3(11):101314. Available from: https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&citation_for_view=ZBKuiKwAAAAJ:QjNCP7ux8QYC.

- Aslanger EK, Meyers PH, Smith SW. STEMI: A transitional fossil in MI classification? J Electrocardiol [Internet] 2021;65:163–9. [CrossRef]

- Ricci F, Martini C, Scordo DM, et al. ECG Patterns of Occlusion Myocardial Infarction: A Narrative Review. 2025;Available from: https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&citation_for_view=ZBKuiKwAAAAJ:-1WLWRmjvKAC.

- Smith SW, Meyers HP. ST Elevation is a poor surrogate for acute coronary occlusion. Let’s Replace STEMI with Occlusion MI (OMI)!! Int J Cardiol [Internet] 2024;131980. [CrossRef]

- Jollis JG, Granger CB, Zègre-Hemsey JK, et al. Treatment Time and In-Hospital Mortality Among Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction, 2018-2021. JAMA [Internet] 2022;328(20):2033–40. [CrossRef]

- Tabner A, Jones M, Fakis A, Johnson G. Can an ECG performed during emergency department triage and interpreted as normal by computer analysis safely wait for clinician review until the time of patient assessment? A pilot study. J Electrocardiol [Internet] 2021;68:145–9. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022073621001710.

- Hughes KE, Lewis SM, Katz L, Jones J. Safety of computer interpretation of normal triage electrocardiograms. Acad Emerg Med [Internet] 2017;24(1):120–4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27519772/.

- Deutsch A, Poroksy K, Westafer L, Visintainer P, Mader T. Validity of computer-interpreted “normal” and “otherwise normal” ECG in emergency department triage patients. West J Emerg Med [Internet] 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 26];25(1):3–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10777178/.

- Langlois-Carbonneau V, Dufresne F, Labbé È, Hamelin K, Berbiche D, Gosselin S. Safety and accuracy of the computer interpretation of normal ECGs at triage. CJEM [Internet] 2024;26(12):857–64. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43678-024-00790-5.

- Noll S, Alvey H, Jayaprakash N, et al. The utility of the triage electrocardiogram for the detection of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Emerg Med [Internet] 2018;36(10):1771–4. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735675718300974.

- Litell JM, Meyers HP, Smith SW. Emergency physicians should be shown all triage ECGs, even those with a computer interpretation of “Normal.” J Electrocardiol [Internet] 2019;54:79–81. [CrossRef]

- Bracey A, Meyers HP, Smith SW. Emergency physicians should interpret every triage ECG, including those with a computer interpretation of “normal.” Am J Emerg Med [Internet] 2022;55:180–2. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/35361516.

- Miranda DF, Lobo AS, Walsh B, Sandoval Y, Smith SW. New Insights Into the Use of the 12-Lead Electrocardiogram for Diagnosing Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Emergency Department. Can J Cardiol [Internet] 2018;34(2):132–45. [CrossRef]

- Aslanger EK, Meyers HP, Smith SW. Recognizing electrocardiographically subtle occlusion myocardial infarction and differentiating it from mimics: Ten steps to or away from cath lab. Archives of the Turkish Society of Cardiology 2021;49(6):488–500.

- Pendell Meyers H, Bracey A, Lee D, et al. Accuracy of OMI ECG findings versus STEMI criteria for diagnosis of acute coronary occlusion myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc [Internet] 2021;33:100767. [CrossRef]

- McLaren JTT, Meyers HP, Smith SW, Chartier LB. Emergency department Code STEMI patients with initial electrocardiogram labeled “normal” by computer interpretation: A 7-year retrospective review. Acad Emerg Med [Internet] 2023;Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acem.14795.

- Smith SW. Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog. http://hqmeded-ecg.blogspot.com/ [Internet] 2008-2025;Available from: https://hqmeded-ecg.blogspot.com/.

- Al-Zaiti SS, Martin-Gill C, Zègre-Hemsey JK, et al. Machine learning for ECG diagnosis and risk stratification of occlusion myocardial infarction. Nat Med [Internet] 2023;29(7):1804–13. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zaiti S, Macleod R, Van Dam P, Smith SW, Birnbaum Y. Emerging ECG methods for acute coronary syndrome detection: Recommendations & future opportunities. J Electrocardiol [Internet] 2022;74:65–72. [CrossRef]

- Herman R, Meyers HP, Smith SW, et al. International evaluation of an artificial intelligence-powered ecg model detecting acute coronary occlusion myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Digit Health [Internet] 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 3];ztad074. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ehjdh/advance-article/doi/10.1093/ehjdh/ztad074/7453297.

- Gupta S, Kashou AH, Herman R, et al. Computer-Interpreted Electrocardiograms: Impact on Cardiology Practice. Computer-Interpreted Electrocardiograms: Impact on Cardiology Practice [Internet] 2024 [cited 2024 Jun 28];37:-. Available from: https://ijcscardiol.org/pt-br/article/computer-interpreted-electrocardiograms-impact-on-cardiology-practice/.

- Dodd KW, Zvosec DL, Hart MA, et al. Electrocardiographic Diagnosis of Acute Coronary Occlusion Myocardial Infarction in Ventricular Paced Rhythm Using the Modified Sgarbossa Criteria. Ann Emerg Med [Internet] 2021;Available from. [CrossRef]

- Meyers HP, Limkakeng AT Jr, Jaffa EJ, et al. Validation of the modified Sgarbossa criteria for acute coronary occlusion in the setting of left bundle branch block: A retrospective case-control study. Am Heart J [Internet] 2015;170(6):1255–64. [CrossRef]

- Smith SW, Dodd KW, Henry TD, Dvorak DM, Pearce LA. Diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the presence of left bundle branch block with the ST-elevation to S-wave ratio in a modified Sgarbossa rule. Ann Emerg Med [Internet] 2012;60(6):766–76. [CrossRef]

- Aslanger EK, Yıldırımtürk Ö, Şimşek B, et al. DIagnostic accuracy oF electrocardiogram for acute coronary OCClUsion resuLTing in myocardial infarction (DIFOCCULT Study). Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc [Internet] 2020;30:100603. [CrossRef]

- Kristian Thygesen, Joseph S Alpert, Allan S Jaffe, Bernard R Chaitman, Jeroen J Bax, David A Morrow, Harvey D White, Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Rev Esp Cardiol [Internet] 2019;72(1):72. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Brown MD, Wolf SJ, Byyny R, et al. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Emergency Department Patients With Suspected Non–ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes. Ann Emerg Med [Internet] 2018;72(5):e65–106. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Garvey JL, Zegre-Hemsey J, Gregg RE, Studnek JR. Electrocardiographic diagnosis of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: An evaluation of three automated interpretation algorithms. J Electrocardiol 2016;49(5):728–32.

- de Alencar Neto JN, Scheffer MK, Correia BP, Franchini KG, Felicioni SP, De Marchi MFN. Systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy of ST-segment elevation for acute coronary occlusion. Int J Cardiol [Internet] 2024;131889. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167527324003358.

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. 2024 Heart Disease and stroke statistics: A report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation [Internet] 2024;149(8):e347–913. Available from: https://www.heart.org/-/media/PHD-Files-2/Science-News/2/2024-Heart-and-Stroke-Stat-Update/2024-Statistics-At-A-Glance-final_2024.pdf.

- Hung C-S, Chen Y-H, Huang C-C, et al. Prevalence and outcome of patients with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with occluded “culprit” artery–a systemic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care [Internet] 2018;22(1):34. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13054-018-1944-x.

- Welch RD, Zalenski RJ, Frederick PD, et al. Prognostic value of a normal or nonspecific initial electrocardiogram in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA [Internet] 2001;286(16):1977–84. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=11667934.

- Welch RD, Zalenski RJ, Frederick PD, et al. Prognostic value of a normal or nonspecific initial electrocardiogram in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA [Internet] 2001;286(16):1977–84. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=11667934.

- Martini C, Scordo DM, Rossi D, Gallina S, Fedorowski A, Sciarra L, Chahal AA, Meyers P, Herman R, Ricci F, Smith SW. ECG Patterns of Occlusion Myocardial Infarction: Ready for Prime Time? Annals of Emergency Medicine In Press.

- Kontos MC, Kurz MC, Roberts CS, et al. An Evaluation of the Accuracy of Emergency Physician Activation of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory for Patients With Suspected ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Ann Emerg Med [Internet] 2010;55(5):423–30. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0196064409014371.

- Larson DM, Menssen KM, Sharkey SW, et al. “False-Positive” Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory Activation Among Patients with Suspected ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JAMA 2007;298(23):2754–60.

- McCabe JM, Armstrong EJ, Kulkarni A, et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated With False-Positive ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Diagnoses at Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention-Capable Centers: A Report From the Activate-SF Registry. Arch Intern Med [Internet] 2012;Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=22566489.

- Garvey JL, Monk L, Granger CB, et al. Rates of Cardiac Catheterization Cancelation for ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction After Activation by Emergency Medical Services or Emergency Physicians. Circulation [Internet] 2012;125(2):308–13. [CrossRef]

- Sharkey S, Herman R, Larson D, Henry TD, Aguirre F, Murthy A, Rohm H, Smith SW, Yildiz M, Belzer W, Chambers J, Bergstedt S, Kerola G, Farmer D, Willett A, Bartunek J, Meyers HP, Barbato E, Harris J, Witt D. Performance of Artificial Intelligence Powered ECG Analysis in Suspected ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction.

| Otherwise Normal ECG Reads | Total | Abnormal ECG Reads | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sinus Bradycardia | 7 | Nonspecific ST-T Wave Abnormality | 7 |

| Sinus Tachycardia | 1 | Consider Subendocardial Injury | 3 |

| Marked Sinus Arrhythmia | 1 | Moderate ST Depression | 2 |

| Frequent PVCs | 1 | Right Bundle Branch Block | 2 |

| Early Repolarization | 1 | Anterior MI of Indeterminate Age | 1 |

| - | - | Possible Acute Pericarditis | 1 |

| - | - | Possible Left Atrial Enlargement | 1 |

| - | - | Prolonged QT | 1 |

| Total “Otherwise Normal” | 11 | Total “Abnormal” | 18 |

| Case Number | Interpretation Software | ECG 1 | ECG 2 | ECG 3 | ECG 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unknown CCA | Normal | Unknown | STEMI (Assumed) | |

| QoH | OMI Mid | (+ 150 Min) | |||

| 3 | Unknown CCA | Normal | Unknown | STEMI (Assumed) | |

| QoH | Not OMI High | OMI High | (+ 40 Min) | ||

| 11 | Zoll Algorithm | STEMI (Assumed) | |||

| QoH | OMI High | ||||

| 14 | Marquette 12 SL | Normal | Normal | Abnormal | STEMI |

| QoH | Not OMI High | OMI High | (+ 120 Min) | ||

| 21 | Unknown CCA | Normal | STEMI (Assumed) | ||

| QoH | OMI High | (Unknown time) | |||

| 30 | Marquette 12 SL | STEMI | |||

| QoH | OMI High | ||||

| 41 | Marquette 12 SL | Normal | STEMI | ||

| QoH | OMI High | (+ 125 Min) | |||

| 42 | Marquette 12 SL | Normal | STEMI (Assumed) | ||

| QoH | OMI High | (+ 45 Min) |

| Case Number | Interpretation Software | ECG 1 | ECG 2 | ECG 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Unknown CCA | Normal | ||

| QoH | Not OMI Mid | |||

| 8 | Marquette 12 SL | Otherwise Normal | ||

| QoH | Not OMI Mid | |||

| 16 | Marquette 12 SL | Normal | Otherwise Normal | Normal |

| QoH | Not OMI High | Not OMI High | Not OMI High | |

| 31 | Unknown CCA | Normal | ||

| QoH | Nor OMI Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).