Introduction

Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) is a diverse clinical condition characterized by the presence of myocardial infarction (MI) without significant obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD). In contrast to conventional myocardial infarction, primarily caused by plaque rupture and thrombus formation in major coronary arteries, MINOCA involves a variety of mechanisms, such as coronary vasospasm, microvascular dysfunction, spontaneous coronary artery dissection, and thrombosis with spontaneous lysis [

1].

Despite advancements in cardiac imaging and biomarker assessment, the exact pathophysiological mechanisms of MINOCA remain incompletely understood, contributing to diagnostic uncertainty and therapeutic challenges [

2]. Distinguishing MINOCA from MINOCA mimickers — conditions that present similarly but lack true myocardial infarction, such as myocarditis and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy — is critical for appropriate management [

3]. Furthermore, understanding how MINOCA differs from MI with obstructive CAD (MI-CAD) is essential, as the latter follows well-established pathophysiological mechanisms with standardized treatment strategies, while MINOCA or MINOCA mimickers require a more nuanced diagnostic and therapeutic approach [

4].

Contemporary research studies suggest that MINOCA or MINOCA mimickers may arise in up to a 5-10% of the total MI population [

5,

6,

7,

8] and may be linked with a comparable prognosis with MI-CAD [

9]. Given the diverse etiologies underlying MINOCA and MINOCA mimickers along with their complex prognostic course, a systematic approach integrating multimodal imaging, laboratory markers, and clinical risk stratification is crucial for improving patient management. This real-world study aimed to add to the existing literature our diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic experience among a well-characterized MI cohort aiming to enhance the characterization of MINOCA and ultimately contribute to personalized therapeutic approaches.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

This was a retrospective, observational cohort study conducted at the First Cardiology Department of AHEPA University Hospital in Thessaloniki (Greece), including consecutive patients admitted with an initial diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction between 2012 and 2024. Data were extracted from the MINOCA-GR [

10] and CardioMining Databases [

11]. The final cohort was stratified into three groups based on diagnostic evaluation: 1: true MINOCA, 2: MI-CAD, and 3: MINOCA mimickers, defined as patients presenting with an initial working diagnosis of MINOCA but ultimately diagnosed with a non-ischemic condition including Takotsubo syndrome or myocarditis. All patients classified as “true MINOCA” or “MI-CAD” underwent coronary angiography during index hospitalization. Patients classified as “MINOCA mimickers” underwent angiography per physician preference.

Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years and hospitalization for acute MI. Exclusion criteria included patients that died during hospitalization, and thus there is no available discharge data. Diagnosis of MI was based on the Fourth Universal Definition, requiring detection of a rise and/or fall in cardiac biomarkers with at least one value above the 99th percentile upper reference limit, accompanied by evidence of myocardial ischemia (clinical symptoms, ECG changes, or imaging findings).

Classification of Groups

True MINOCA was defined according to the 2019 American Heart Association scientific statement, requiring the presence of acute myocardial infarction, non-obstructive coronary arteries (<50% stenosis in any major epicardial vessel), and the exclusion of alternative diagnoses such as myocarditis or Takotsubo syndrome.

MI-CAD included patients with myocardial infarction and obstructive CAD, defined as ≥50% stenosis in at least one major coronary artery.

MINOCA mimickers included patients who initially fulfilled criteria for MINOCA (acute MI with non-obstructive coronary arteries) but were subsequently diagnosed with non-ischemic etiologies based on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging or other diagnostic tools. These comprised Takotsubo syndrome and myocarditis.

Data Collection

Demographic characteristics, presenting symptoms, cardiovascular risk factors, medical history, laboratory findings at admission, electrocardiographic (ECG) features, echocardiographic parameters, diagnostic imaging studies, in-hospital management, and discharge medication were extracted from electronic medical records.

Diagnostic Imaging

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) was performed in a subset of patients with non-obstructive coronary arteries to evaluate for myocarditis, Takotsubo syndrome, infarction, or other structural abnormalities. The diagnosis of myocarditis was based on Lake Louise criteria, requiring the presence of myocardial edema and non-ischemic late gadolinium enhancement. Takotsubo syndrome was diagnosed based on established criteria, including transient wall motion abnormalities extending beyond a single coronary territory, absence of obstructive coronary disease or plaque rupture, new ECG abnormalities or modest troponin elevation, and exclusion of other causes.

Other imaging modalities, including coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and ambulatory ECG (Holter) monitoring, were performed at the discretion of the treating physicians.

Outcomes

The clinical outcome of interest was all-cause mortality. Mortality data were obtained from hospital records or national death registries.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Variables with non-normal distribution were summarized as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), and comparisons across the three groups were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis H test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.4.2) and SPSS (version 28).

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards or Ethics Committees. All patient data were anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis to ensure confidentiality. No personal patient information was collected or stored. Due to the retrospective design, the requirement for individual patient consent was waived by the ethics committee in compliance with Greek regulatory guidelines.

Results

Study Population and Group Distribution

A total of 1596 patients were hospitalized for acute MI in our Cardiology Department from 2012 until 2024 (median year of hospitalization: 2017). Among these, 111 (7.0%) were classified as true MINOCA, 1359 (85%) as MI-CAD, and 127 (8.0%) as MINOCA mimickers (

Table 1).

Clinical Profile of True MINOCA Patients

The median age of patients with MINOCA was 63 years, and approximately half were male. The median duration of hospitalization was 6 days. Most MINOCA cases presented as non-ST elevation myocardial infarction, with chest pain being the predominant symptom. Common cardiovascular risk factors included smoking in nearly half of the patients, arterial hypertension in over 40%, and dyslipidemia in almost 30%. Electrocardiographic abnormalities comprised mainly negative T waves in nearly 40% of patients. Discharge medications were largely guideline-directed, with antiplatelets used in over 93%, beta-blockers in 75%, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in just over half of the patients. However, dual antiplatelet therapy was prescribed in only 7 out of 10 patients with true MINOCA. Imaging and laboratory evaluations revealed a preserved median left ventricular ejection fraction, normal chamber dimensions, and moderate elevations in cardiac biomarkers such as high-sensitivity troponin T and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide. In-hospital management universally included coronary angiography, while additional imaging such as CMR and CCTA was performed in more than half of patients (

Table 1).

Comparison of MINOCA with MI-CAD and MINOCA Mimickers

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Patients with MINOCA mimickers were significantly younger compared to those with true MINOCA or MI-CAD (median age 38 [38] vs. 63 [22] and 64 [21], respectively, p < 0.001). Male sex was less prevalent in the true MINOCA and MINOCA mimicker groups (53.2% and 67.7%, respectively) than in the MI-CAD group (77.5%, p < 0.001). Hospitalization duration did not differ significantly across groups.

ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was observed in 59.0% of MI-CAD cases, 5.4% of true MINOCA, and 0.8% of mimickers (p < 0.001). NSTEMI presentation was absent among mimickers but present in 55.0% of true MINOCA and 41.1% of MI-CAD (p < 0.001).

Chest pain was the predominant symptom at presentation in all groups. Fever was notably more common in MINOCA mimickers (28.3%) compared to other groups (p < 0.001). Dyspnea and palpitations showed no significant inter-group differences.

Medical history and cardiovascular risk factors

Smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus were significantly more common in the MI-CAD group. Conversely, a history of myocarditis was exclusively observed in the MINOCA mimicker group (5.5%, p < 0.001). Chronic kidney disease was predominantly associated with MI-CAD (7.9%, p < 0.001). Connective tissue disease was more prevalent among mimickers and true MINOCA compared to MI-CAD (p = 0.035).

Electrocardiographic findings

ST-segment elevation at admission was most frequent in MI-CAD (39.7%) and lowest in true MINOCA (10.8%, p < 0.001). ST depression and pathological Q waves were similarly more common in MI-CAD. Negative T waves were significantly more prevalent in true MINOCA (39.6%) compared to MI-CAD (19.0%) and mimickers (22.0%, p < 0.001).

Laboratory values

Peak high-sensitivity troponin T levels were highest in MI-CAD (median 1314 [2963]), followed by true MINOCA (197 [699]) and mimickers (232 [766]) (p < 0.001). White blood cell counts, blood glucose, creatinine, CPK, and NT-proBNP levels differed significantly across groups, with higher inflammatory and metabolic markers observed in MI-CAD.

Echocardiographic parameters

LVEF was higher in true MINOCA (59 [11]) and mimickers (60 [15]) compared to MI-CAD (52 [17], p < 0.001). The E/E′ ratio was significantly lower in mimickers (6.3 [

2]) than in MI-CAD and true MINOCA (p = 0.003). No significant differences were observed in left atrial volume or LVED diameter.

Pharmaceutical therapies

Antiplatelet therapy and dual antiplatelet therapy were predominantly used in MI-CAD (97.6% and 89.8%, respectively), while significantly less frequent in MINOCA mimickers (18.9% and 1.6%, respectively, p < 0.001). Beta-blockers, RAAS inhibitors, and statins were also more frequently prescribed in MI-CAD.

CMR and CCTA imaging

Advanced imaging modalities, particularly CMR and CCTA, were extensively utilized in patients with MINOCA and significantly contributed to diagnostic clarification. Among the 244 patients classified as either true MINOCA (n = 117) or MINOCA mimickers (n = 127), CMR was performed in 145 patients (59.4%) and CCTA in 72 patients (29.5%).

CMR was performed in 75 of 117 true MINOCA patients (64.1%), all of whom demonstrated findings consistent with an ischemic etiology. Specifically, all patients exhibited subendocardial or transmural late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in a coronary distribution, confirming acute myocardial infarction. In the MINOCA mimicker group, CMR was performed in 61 of 127 patients (48.0%). Among these, 36 patients (59.0%) were diagnosed with myocarditis based on typical mid-wall or subepicardial LGE patterns, 21 patients (34.4%) with Takotsubo syndrome based on regional wall motion abnormalities and myocardial edema without LGE, and 4 patients (6.6%) had normal CMR findings. Thus, CMR contributed to a specific diagnosis in 93.4% of mimicker cases in which it was performed. In contrast, CMR was used in only 9 of 1,359 MI-CAD patients (0.7%) (p < 0.001).

CCTA was performed in 65 of 117 true MINOCA patients (55.5%), in 7 of 127 mimicker patients (5.5%), and in only 3 of 1359 MI-CAD patients (0.2%) (p < 0.001). Among true MINOCA cases, CCTA identified non-obstructive coronary atherosclerosis in 49 of 65 patients (75.4%). Notably, 21 of these 49 patients (42.9%) exhibited high-risk plaque features, including positive remodeling and low-attenuation plaque, which are commonly associated with plaque vulnerability and rupture. In many of these cases, the location of the high-risk plaques anatomically corresponded with the infarct-related myocardial territory identified on CMR, reinforcing a diagnosis of type 1 myocardial infarction due to plaque disruption despite the absence of obstructive stenosis on invasive angiography. In the remaining 16 patients (24.6%), CCTA demonstrated completely normal coronary arteries, increasing the likelihood of functional ischemic mechanisms such as epicardial vasospasm or microvascular dysfunction.

Importantly, CCTA provided incremental value beyond CMR in 38 of 72 patients (52.8%) who underwent both modalities. In true MINOCA, CCTA confirmed the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis or high-risk plaque in patients with infarction-confirmed CMR and angiographically unobstructed arteries, directly impacting management decisions such as the initiation or intensification of antiplatelet and lipid-lowering therapies. In contrast, among mimicker patients, CCTA revealed completely normal coronary anatomy in 6 of 7 patients (85.7%), corroborating the non-ischemic diagnoses established by CMR and helping exclude subtle coronary abnormalities that could have confounded the clinical picture.

In total, among the 244 patients with non-obstructive coronary arteries, advanced imaging with either CMR or CCTA was performed in 181 patients (74.2%), contributing to diagnostic clarification in 170 patients (69.7%). CMR enabled definitive characterization of myocardial tissue injury, distinguishing ischemic infarction from myocarditis and Takotsubo syndrome. CCTA added unique anatomical and plaque-specific information, identifying high-risk but non-obstructive coronary lesions in ischemic MINOCA and confirming normal coronary anatomy in mimicker cases.

Outcomes

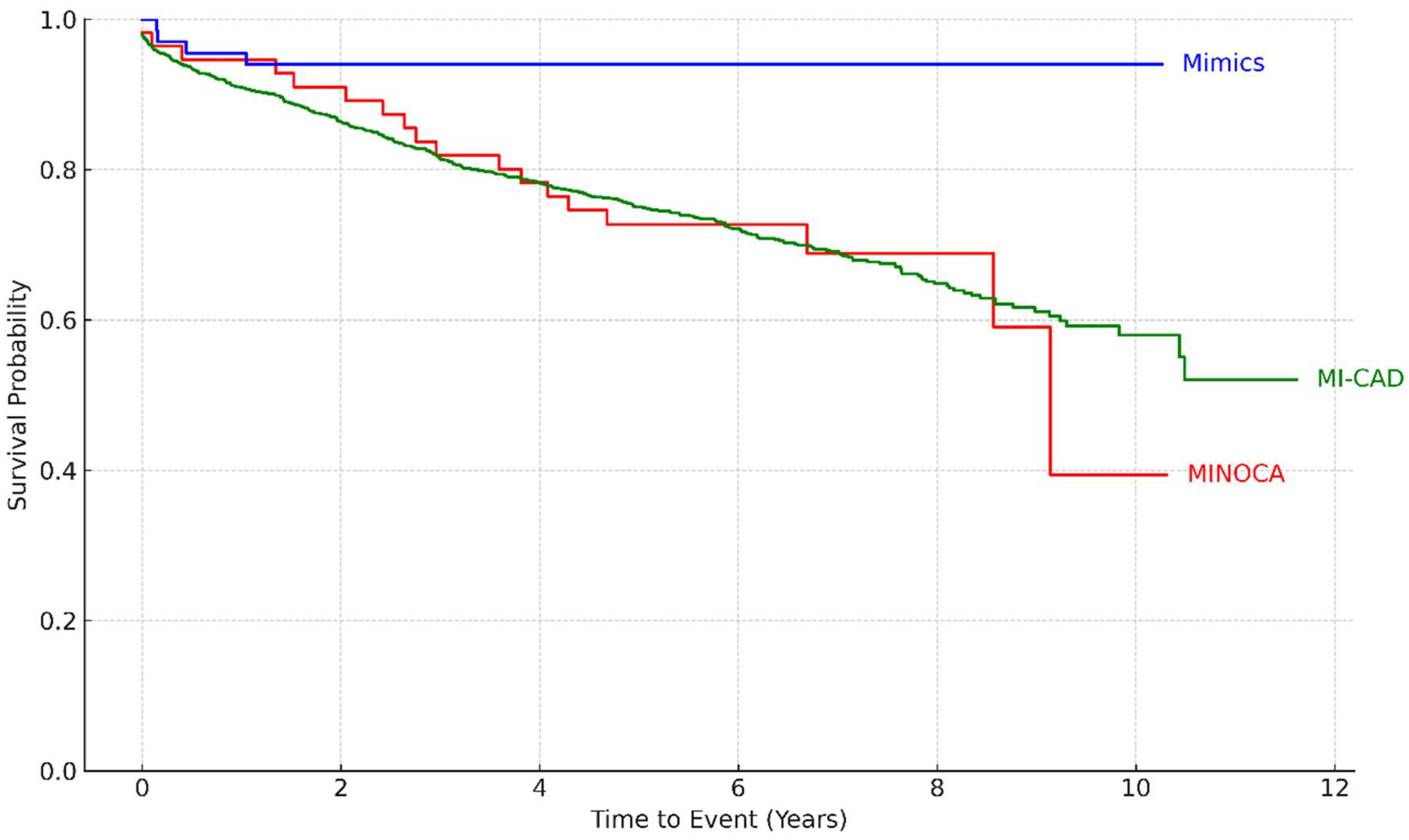

Follow-up data were available for 1434 patients (90% of the total) (

Table 1). During a median follow-up of 6 years, 427 patients (26.8%) died from any cause. All-cause mortality was significantly higher among patients with MI-CAD (30.9%) and those with true MINOCA (32.1%) compared to patients with MINOCA mimickers (5.9%) (p < 0.001). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (

Figure 1) highlighted the most favorable long-term survival in the MINOCA mimics group, whereas patients with true MINOCA had the poorest survival trajectory over time (log-rank p-value = 0.002).

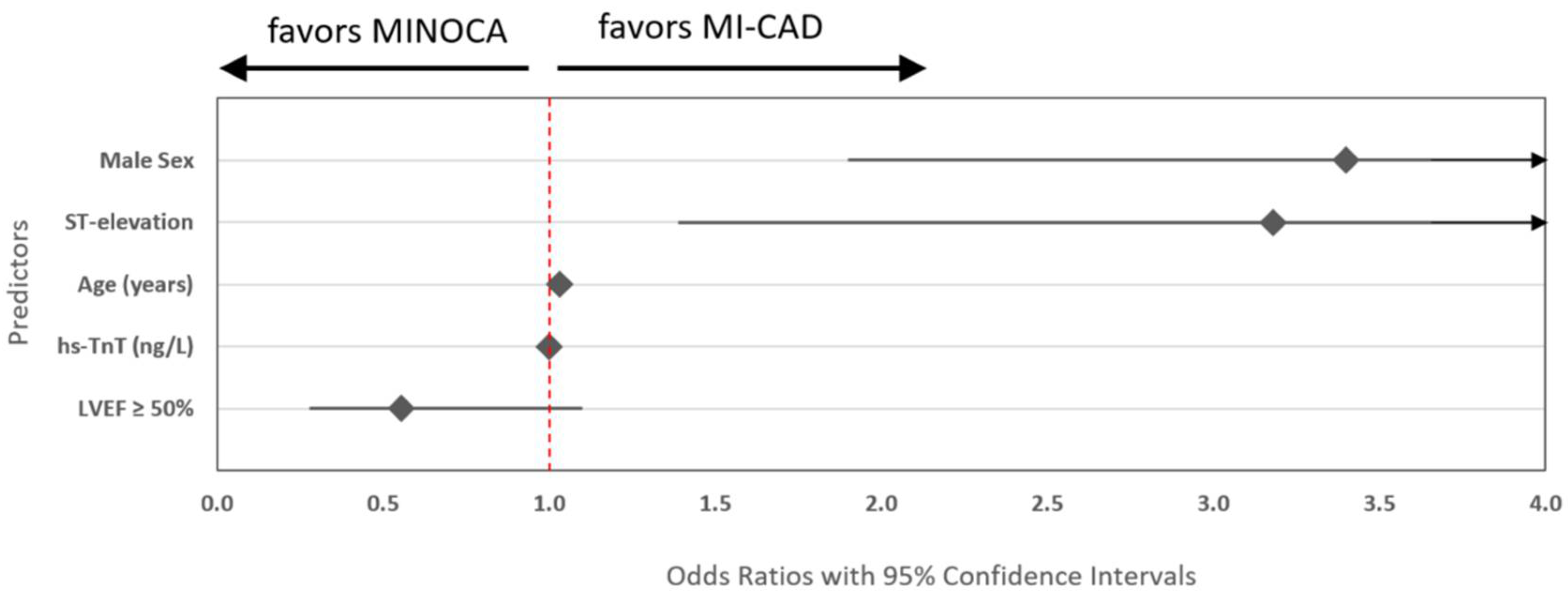

Diagnostic Predictors Between True MINOCA and MI-CAD

In multivariable logistic regression analysis evaluating distinct diagnostic features between true MINOCA vs MI-CAD, five variables were independently associated with diagnostic classification (

Table 2). Male sex and ST-segment elevation at admission were strongly associated with more than 3-fold odds of MI-CAD compared with MINOCA. Older age and higher admission levels of hs-TnT were also positively associated with obstructive MI. In contrast, preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF ≥ 50%) was associated with increased odds of true MINOCA (

Figure 2).

Discussion

This real-world study, the first relevant cohort study in Greece, provided a comprehensive analysis of MINOCA, highlighting key etiological contributors and their prognostic implications. Our findings indicate that patients with true MINOCA exhibit distinct clinical and imaging characteristics compared to those with MI-CAD and MINOCA mimickers. True MINOCA accounted for 7% of MI cases, while MI-CAD remained the predominant etiology (85%). MINOCA mimickers (8% of the total population) were significantly younger compared to true MINOCA and MI-CAD, with a lower prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors. Patients with MINOCA appeared to have a distinct clinical phenotype, including fewer cardiovascular risk factors, lower biomarker levels, and more favorable echocardiographic parameters compared to those with obstructive CAD. However, long-term all-cause mortality in patients with true MINOCA was comparable to those with MI-CAD (32.1% vs 30.9%) and significantly higher than in MINOCA mimickers (5.9%). Furthermore, advanced imaging modalities, including CMR and CCTA, were crucial for diagnostic clarification, with CMR distinguishing ischemic infarction from alternative diagnoses in 93% of MINOCA mimickers. High-risk plaque features were identified in 43% of true MINOCA patients using CCTA. Management strategies differed significantly, with dual antiplatelet therapy and PCI primarily used in MI-CAD, while conservative management was more common in MINOCA and mimicker cases.

Prevalence

MINOCA prevalence seems to vary significantly across studies due to differing definitions and diagnostic criteria [

12]. For instance, a most recent study reported that among 8560 STEMI patients, 4.8% of them had non-obstructive CAD, including 1.4% with true MINOCA and 3.4% with MINOCA mimickers [

8]. Other large cohort studies, published during the last 5 years, indicate a prevalence rate of 1% to 4% for MINOCA among acute MI patients [

5,

6,

7,

13]. Specific global prevalence data for MINOCA mimickers are limited, as their identification heavily relies on the availability and application of comprehensive diagnostic evaluations, including CMR.

Diagnostic Yield of CMR and CCTA in Suspected MINOCA

The diagnosis of MINOCA remains a challenge due to its heterogeneous pathophysiology, which includes coronary plaque disruption, coronary vasospasm, coronary embolism, microvascular dysfunction, and myocardial disorders such as Takotsubo syndrome or myocarditis. Studies emphasize the importance of multimodal imaging, including coronary angiography with intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography (OCT), to detect plaque rupture, erosion, or thrombus, which may not be visible on conventional angiography. A study by Reynolds et al. highlighted that nearly 40% of MINOCA patients had evidence of plaque disruption on IVUS, underscoring the role of intravascular imaging in identifying underlying mechanisms [

14]. Another study demonstrated that OCT identified culprit lesions in 77.5% of MINOCA cases, with 12.5% of patients displaying multiple hyperenhanced myocardial lesions, suggesting coronary embolization as a potential mechanism [

15]. Similarly, CMR has been shown to be a pivotal tool in distinguishing between ischemic and non-ischemic causes, such as myocarditis or stress cardiomyopathy, which can mimic MINOCA. CMR can detect infarct-related edema via T2-weighted imaging and identify fibrosis using LGE and, thereby, differentiate MINOCA from myocarditis, stress cardiomyopathy, or other non-ischemic causes [

16]. Notably, the combined use of OCT and CMR has been shown to result in a diagnosis for 100% of patients classified as MINOCA, highlighting the powerful synergy between intracoronary and cardiac imaging in elucidating the underlying etiology [

17]. The integration of OCT with CMR significantly enhances diagnostic accuracy, achieving a yield of 85% compared to 44% with OCT alone and 74% with CMR alone [

17].

CCTA has emerged as a valuable non-invasive imaging modality in the diagnostic work-up of patients with suspected MINOCA, particularly in distinguishing ischemic mechanisms from non-ischemic mimickers. CCTA offers high-resolution visualization of coronary anatomy, enabling the detection of non-obstructive atherosclerotic plaque that may be underestimated or missed by invasive coronary angiography [

18]. Such plaques may represent the substrate for plaque rupture or erosion—mechanisms increasingly recognized in the pathophysiology of MINOCA [

19]. In particular, CCTA can identify high-risk plaque features, including positive remodeling, low-attenuation plaque, and napkin-ring sign, all of which are associated with coronary instability even in the absence of significant luminal stenosis [

20,

21]. In studies involving MINOCA patients with infarction confirmed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR), CCTA has uncovered culprit plaques not visualized on angiography, often located within the infarct-related artery and exhibiting expansive remodeling and larger plaque burden, supporting a diagnosis of type 1 myocardial infarction. Conversely, CCTA can confirm entirely normal coronary arteries in patients ultimately diagnosed with non-ischemic conditions such as Takotsubo syndrome or myocarditis. In this context, CCTA serves as a gatekeeper by excluding obstructive or high-risk coronary lesions, thereby justifying a reclassification of the clinical event. Additionally, although CCTA does not directly assess microvascular function, its ability to rule out significant epicardial coronary disease supports the use of downstream functional testing (e.g., myocardial perfusion imaging or invasive coronary physiology) when microvascular dysfunction is suspected [

22]. Emerging CCTA-based tools, such as fractional flow reserve derived from CT (FFR-CT) and the pericoronary fat attenuation index (pFAI), are being investigated for their potential to identify functional ischemia or coronary inflammation [

23,

24]. Overall, CCTA complements CMR by elucidating the coronary substrate of MINOCA, refining diagnostic classification, and informing therapeutic decisions—whether through the identification of subclinical yet high-risk atherosclerosis requiring secondary prevention or by reinforcing a non-ischemic diagnosis when coronary arteries appear truly normal.

Prognosis and Management

The prognosis of patients with MINOCA depends on the underlying cause and is currently under active investigation [

4]. While some studies suggest that MINOCA patients may have a better short-term prognosis compared to those with MI-CAD [

5,

13,

25], the long-term outcomes are concerning, with significant risks of mortality and adverse cardiovascular events that might even exceed the risk of MI-CAD patients [

13,

26,

27,

28]. A meta-analysis of MINOCA studies demonstrated similar results, with a pooled in-hospital mortality rate of 0.9% but a pooled 12-month mortality rate of 4.7% [

25]. The prognosis of MINOCA mimickers appears to be comparable to or slightly better than that of MINOCA patients [

27], though further research is needed to elucidate these differences fully.

Since the underlying cause of MINOCA is identified, management strategies must be tailored accordingly. For cases where an ischemic mechanism is confirmed—such as plaque rupture, coronary spasm, or thrombus—treatment aligns with standard MI guidelines, similar to patients with MI-CAD. These individuals should receive secondary prevention strategies, including antiplatelet therapy, statins, ACE inhibitors, and beta-blockers, in line with established cardioprotective measures [

4]. The American Heart Association specifically recommends that when plaque disruption or another ischemic etiology is detected, post-MI treatment should mirror that of MI-CAD [

4]. However, real-world data suggest that patients with MINOCA often receive less intensive pharmacologic therapy at discharge compared to those with MI-CAD [

29]. Registry data indicate that standard MI treatments such as aspirin, beta-blockers, and statins are prescribed less frequently to MINOCA patients, likely reflecting uncertainty in diagnosis or the heterogeneous nature of the condition [

27]. On the other hand, traditional post-discharge therapies used in acute MI, such as DAPT, appear to have a neutral prognostic effect in patients with a generic diagnosis of “MINOCA” [

30]. These discrepancies emphasize the importance of precise diagnostic workup to guide appropriate management.

For conditions that mimic MINOCA but do not involve a primary ischemic mechanism, management diverges significantly. In Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, the treatment is primarily supportive, focusing on hemodynamic stabilization and addressing potential complications such as heart failure or arrhythmias [

31]. Long-term, beta-blockers have been considered for recurrence prevention, although evidence remains inconclusive regarding their efficacy [

31]. Similarly, myocarditis management varies depending on the subtype. Importantly, in myocarditis, antithrombotic and ischemia-directed therapies are generally unwarranted unless there is another clear indication, distinguishing it from true ischemic injury. These key differences highlight the risk of broadly categorizing MINOCA mimickers with ischemic MINOCA, as a one-size-fits-all approach could lead to inappropriate treatment.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that warrant consideration. First, its retrospective, single-center design may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings to other healthcare settings or populations. Second, the classification of patients into true myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries, myocardial infarction with obstructive coronary artery disease, and myocardial infarction mimickers relied on the availability and interpretation of advanced imaging, which was not systematically performed in all patients and may have led to misclassification in a subset of cases. Third, the absence of intracoronary imaging modalities such as optical coherence tomography or intravascular ultrasound during coronary angiography may have limited the detection of subtle plaque disruption or thrombus, particularly in patients with angiographically non-obstructive disease. Fourth, data on cause-specific mortality and non-fatal cardiovascular events were not uniformly available, precluding a more granular assessment of clinical outcomes. Lastly, although discharge medication use was reported, data on adherence, dose titration, and long-term medical management were not captured, which may have influenced the observed outcomes.

Conclusions

In this single-center cohort study, true MINOCA accounted for 7% of total acute MI cases and was associated with a distinct clinical profile, in terms of traditional risk factors, biomarker levels, and cardiac function, compared to MI-CAD. Despite these features, long-term all-cause mortality in patients with MINOCA was comparable to that of MI-CAD but significantly higher than that of patients with MINOCA mimickers. Advanced imaging with CMR and CCTA was essential for confirming ischemic injury, identifying high-risk plaques, and distinguishing non-ischemic mimickers. These findings highlight the prognostic significance of true MINOCA and the need for comprehensive diagnostic evaluation to guide personalized management and improve long-term outcomes.

Author Contributions

All individuals listed as authors qualify for authorship and have participated sufficiently in the work, meeting all the conditions specified in the guidelines of the ICJME. Specifically all authors: made substantial contributions to the conception and design (AS), acquisition of data (AS, DVM, ASP, GPR, KB, AB, CK), or analysis and interpretation of data (AS, DVM, ASP, GPR, KB, AB, CK, EK, BF, GK, AT, AZ, NF, KK, VV, GG) AND; drafted the article (AS, DVM, ASP) or revised it critically for important intellectual content (AS, DVM, ASP, GPR, KB, AB, CK, EK, BF, GK, AT, AZ, NF, KK, VV, GG) AND; given final approval of the version to be published (AS, DVM, ASP, GPR, KB, AB, CK, EK, BF, GK, AT, AZ, NF, KK, VV, GG) AND; agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved (AS, DVM, ASP, GPR, KB, AB, CK, EK, BF, GK, AT, AZ, NF, KK, VV, GG).

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of AHEPA University of Thessaloniki, Greece (protocol code – 27283/24.6.2020 and date of approval – 24.6.2020).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Abbreviations

AMI – Acute myocardial infarction

CAD – Coronary artery disease

CMR – Cardiac magnetic resonance

CCTA – Coronary computed tomography angiography

CTPA – Computed tomography pulmonary angiography

DAPT – Dual antiplatelet therapy

ECG – Electrocardiogram

HDL – High-density lipoprotein

HFmrEF – Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction

HFpEF – Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

HFrEF – Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

hs-TnT – High-sensitivity troponin T

IVUS – Intravascular ultrasound

LGE – Late gadolinium enhancement

LVEF – Left ventricular ejection fraction

LVEDd – Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter

MI – Myocardial infarction

MI-CAD – Myocardial infarction with obstructive coronary artery disease

MINOCA – Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries

MRA – Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

NT-proBNP – N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

OCT – Optical coherence tomography

PCI – Percutaneous coronary intervention

RAASi – Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitor

SPECT – Single-photon emission computed tomography

STEMI – ST-elevation myocardial infarction

TG – Triglycerides

WBC – White blood cell count

References

- Pasupathy S, Tavella R, Beltrame JF. Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA): The Past, Present, and Future Management. Vol. 135, Circulation. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2017. p. 1490–3.

- Samaras A, Moysidis D V., Papazoglou AS, Rampidis G, Kampaktsis PN, Kouskouras K, et al. Diagnostic Puzzles and Cause-Targeted Treatment Strategies in Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries: An Updated Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, Vol 12, Page 6198 [Internet]. 2023 Sep 26 [cited 2025 Apr 2];12(19):6198. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/12/19/6198/htm¶.

- Ciliberti G, Montone R, Pasupathy S, Lentini L, De Oliveira H, Correia M, et al. MINOCA: One Size Fits All? Probably Not—A Review of Etiology, Investigation, and Treatment. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, Vol 11, Page 5497 [Internet]. 2022 Sep 20 [cited 2025 Apr 3];11(19):5497. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/11/19/5497/htm.

- Tamis-Holland JE, Jneid H, Reynolds HR, Agewall S, Brilakis ES, Brown TM, et al. Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Myocardial Infarction in the Absence of Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation [Internet]. 2019 Apr 30 [cited 2025 Apr 2];139(18):E891–908. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000670.

- Hao K, Takahashi J, Sato K, Fukui K, Shindo T, Oyama K, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcome of Patients With Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries in Japan: Insights From the Miyagi Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry Study. Journal of the American Heart Association [Internet]. 2025 Mar 4 [cited 2025 Apr 2];14(5):36802. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.124.036802.

- Onuma S, Takahashi J, Shiroto T, Godo S, Hao K, Honda S, et al. Characteristics and In-Hospital Outcomes of Patients With Myocardial Infarction With Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries ― Insights From the Real-World JAMIR Database ―. Circulation Journal. 2025 Feb 25;89(3):382–90.

- Gasior P, Desperak A, Gierlotka M, Milewski K, Wita K, Kalarus Z, et al. Clinical Characteristics, Treatments, and Outcomes of Patients with Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA): Results from a Multicenter National Registry. J Clin Med [Internet]. 2020 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];9(9):2779. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7564426/.

- Yildiz M, Pico M, Henry TD, Bergstedt S, Stanberry L, Chambers J, et al. Sex Differences in Patients Presenting With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions [Internet]. 2025 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];105(5):1204–13. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ccd.31438.

- Kang WY, Jeong MH, Ahn YK, Kim JH, Chae SC, Kim YJ, et al. Are patients with angiographically near-normal coronary arteries who present as acute myocardial infarction actually safe? Int J Cardiol. 2011 Jan 21;146(2):207–12.

- Rampidis GP, Kampaktsis PN, Kouskouras K, Samaras A, Benetos G, Giannopoulos AI, et al. Role of cardiac CT in the diagnostic evaluation and risk stratification of patients with myocardial infarction and non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA): rationale and design of the MINOCA-GR study. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2022 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];12(2):e054698. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/12/2/e054698.

- Samaras A, Bekiaridou A, Papazoglou AS, Moysidis D V., Tsoumakas G, Bamidis P, et al. Artificial intelligence-based mining of electronic health record data to accelerate the digital transformation of the national cardiovascular ecosystem: design protocol of the CardioMining study. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2023 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];13(4):e068698. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/13/4/e068698.

- Pasupathy S, Tavella R, Beltrame JF. Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA): The Past, Present, and Future Management. Circulation [Internet]. 2017 Apr 18 [cited 2025 Apr 2];135(16):1490–3. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027666.

- Wong CJ, Yap J, Gao F, Lau YH, Huang W, Jaufeerally F, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of MI with Non-obstructive Coronary Arteries in a South-east Asian Cohort. Journal of Asian Pacific Society of Cardiology. 2022 Jan 13;1.

- Reynolds HR, Srichai MB, Iqbal SN, Slater JN, Mancini GBJ, Feit F, et al. Mechanisms of myocardial infarction in women without angiographically obstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation [Internet]. 2011 Sep 27 [cited 2025 Apr 2];124(13):1414–25. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.026542.

- Gerbaud E, Arabucki F, Nivet H, Barbey C, Cetran L, Chassaing S, et al. OCT and CMR for the Diagnosis of Patients Presenting With MINOCA and Suspected Epicardial Causes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Dec 1;13(12):2619–31.

- Abdel-Aty H, Zagrosek A, Schulz-Menger J, Taylor AJ, Messroghli D, Kumar A, et al. Delayed enhancement and T2-weighted cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging differentiate acute from chronic myocardial infarction. Circulation [Internet]. 2004 May 25 [cited 2025 Apr 2];109(20):2411–6. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.CIR.0000127428.10985.C6.

- Reynolds HR, Maehara A, Kwong RY, Sedlak T, Saw J, Smilowitz NR, et al. Coronary Optical Coherence Tomography and Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Determine Underlying Causes of Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries in Women. Circulation [Internet]. 2021 Feb 16 [cited 2025 Apr 2];143(7):624–40. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052008.

- Serruys PW, Kotoku N, Nørgaard B, Garg S, Nieman K, Dweck M, et al. Computed tomographic angiography in coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. 2023 Apr 1;18(16):E1307–27.

- Rampidis G, Rafailidis V, Kouskouras K, Davidhi A, Papachristodoulou A, Samaras A, et al. Relationship between Coronary Arterial Geometry and the Presence and Extend of Atherosclerotic Plaque Burden: A Review Discussing Methodology and Findings in the Era of Cardiac Computed Tomography Angiography. Diagnostics 2022, Vol 12, Page 2178 [Internet]. 2022 Sep 9 [cited 2025 Apr 2];12(9):2178. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/12/9/2178/htm.

- Eitel I, Von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Bernhardt P, Carbone I, Muellerleile K, Aldrovandi A, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Findings in Stress (Takotsubo) Cardiomyopathy. JAMA [Internet]. 2011 Jul 20 [cited 2025 Apr 2];306(3):277–86. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1104115.

- Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (Tako-Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): A mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2008 Mar 1;155(3):408–17.

- Smilowitz NR, Toleva O, Chieffo A, Perera D, Berry C. Coronary Microvascular Disease in Contemporary Clinical Practice. Circ Cardiovasc Interv [Internet]. 2023 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];16(6):E012568. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.122.012568.

- Gaibazzi N, Martini C, Botti A, Pinazzi A, Bottazzi B, Palumbo AA. Coronary inflammation by computed tomography pericoronary fat attenuation in MINOCA and Tako-Tsubo syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc [Internet]. 2019 Sep 3 [cited 2025 Apr 2];8(17). Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.119.013235.

- Meier D, Andreini D, Cosyns B, Skalidis I, Storozhenko T, Mahendiran T, et al. Usefulness of FFR-CT to exclude haemodynamically significant lesions in high-risk NSTE-ACS. EuroIntervention. 2025 Jan 6;21(1):73–81.

- Pasupathy S, Air T, Dreyer RP, Tavella R, Beltrame JF. Systematic review of patients presenting with suspected myocardial infarction and nonobstructive coronary arteries. Circulation [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Apr 2];131(10):861–70. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011201.

- Dreyer RP, Tavella R, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Pauspathy S, Messenger J, et al. Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries as compared with myocardial infarction and obstructive coronary disease: outcomes in a Medicare population. Eur Heart J [Internet]. 2020 Feb 14 [cited 2025 Apr 2];41(7):870–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31222249/.

- Quesada O, Yildiz M, Henry TD, Bergstedt S, Chambers J, Shah A, et al. Mortality in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries and Mimickers. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. 2023 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];6(11):e2343402–e2343402. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2811941.

- Gasior P, Desperak A, Gierlotka M, Milewski K, Wita K, Kalarus Z, et al. Clinical Characteristics, Treatments, and Outcomes of Patients with Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA): Results from a Multicenter National Registry. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, Vol 9, Page 2779 [Internet]. 2020 Aug 27 [cited 2025 Apr 2];9(9):2779. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/9/9/2779/htm.

- Adams C, Sawhney G, Singh K. Comparing pharmacotherapy in MINOCA versus medically managed obstructive acute coronary syndrome. Heart Vessels [Internet]. 2022 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];37(4):705–10. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00380-021-01956-2.

- Samaras A, Papazoglou AS, Balomenakis C, Bekiaridou A, Moysidis D V., Rampidis GP, et al. Prognostic impact of secondary prevention medical therapy following myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries: a Bayesian and frequentist meta-analysis. European Heart Journal Open [Internet]. 2022 Nov 21 [cited 2025 Apr 2];2(6):1–10. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ehjopen/oeac077.

- Medina de Chazal H, Del Buono MG, Keyser-Marcus L, Ma L, Moeller FG, Berrocal D, et al. Stress Cardiomyopathy Diagnosis and Treatment: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2018 Oct 16 [cited 2025 Apr 2];72(16):1955–71. Available from: https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.072.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).