1. Introduction

Intrauterine adhesions (IUA), also known as Asherman Syndrome, involve the formation of scar tissue within the uterine cavity. This condition was first described by Heinrich Fritsch in 1894, and the term "Asherman Syndrome" was later coined by Josef Asherman in 1948 [

1,

2]. Since then, numerous cases and various treatment protocols have been reported. Patients with Asherman Syndrome exhibit a range of symptoms including infertility, hypomenorrhea, amenorrhea, menstrual irregularities, pregnancy loss, obstetric complications, and placental invasion anomalies [

4]. However, the diagnosis and treatment of Asherman Syndrome remain subjects of debate.

The incidence of Asherman Syndrome varies depending on the studied popullation, being 4.6% among infertile women, 37.6% following abortions, and 40% after recurrent curettage. The primary causes of IUA include trauma and infections affecting the basal layer of the endometrium. Risk factors include procedures such as curettage, myomectomy, surgeries for Mullerian anomalies, uterine embolization, B-lynch sutures, and conditions such as genital tuberculosis and schistosomiasis [

5,

7].

Diagnostic imaging techniques such as transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasonography, sonohysterography, and hysterosalpingography are valuable tools for detecting adhesions [

3,

5]. Hysteroscopy is considered the gold standard for both diagnosing and treating IUA [

8]. However, a significant challenge remains in preventing re-adhesion formation post-surgery. Minimally invasive approaches to prevent adhesions, such as using intrauterine devices, Foley catheters, and gel barriers, have been explored [

6,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The success rate of adhesiolysis for menstrual problems ranges from 52% to 88%, and live birth rates in infertile patients range from 25% to 35%. Re-adhesion rates for severe adhesions are reported to be between 52% and 62%, indicating the need for additional treatments post-surgery.

Trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-induced inflammation closely resembles the inflammation observed in Asherman syndrome, making it a suitable experimental model for studying intrauterine adhesions. Both conditions involve an initial acute inflammatory response that transitions into a chronic phase, ultimately leading to fibrosis.

In TCA-induced inflammation, the tissue damage caused by the chemical agent triggers a cascade of immune responses, beginning with polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) in the acute phase and transitioning to macrophages in the chronic phase. This inflammatory progression mirrors the pathways observed in Asherman syndrome. Similarly, in Asherman syndrome, retained products of conception act as irritants, initiating an immune response characterized by macrophage activity and fibroblast activation, which promotes fibrosis.

The shared outcome in both conditions is the development of fibrotic tissue within the uterus, disrupting its normal function. Therefore, the inflammatory and fibrotic responses observed in TCA-treated models provide a reliable framework for understanding the pathophysiology of Asherman syndrome and evaluating potential therapeutic interventions.

Steroids are utilized to suppress the initial inflammatory response, reduce vascular permeability, and inhibit fibroblast proliferation in response to tissue damage. They achieve this by inhibiting chemotactic factors, cytokine production, and release [

13]. Steroids can be administered intravenously, orally, or intraperitoneally. Corticosteroids are effective at both early and late stages of inflammation, targeting processes such as fibrin deposition, collagen formation, and fibroblast and capillary proliferation [

18]. By preventing fibrin and collagen buildup, steroids help reduce adhesion formation [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, the primary side effect of corticosteroid therapy aimed at preventing adhesion formation is delayed wound healing due to immune suppression and inhibited fibroblast proliferation [

13,

16,

17]. Although studies have investigated the use of hyaluronic acid (HA) and steroids to prevent intra-abdominal adhesions, no studies have directly compared the anti-adhesion effects of these two agents when used together. This study aims to investigate and compare the efficacy of hyaluronic acid and methylprednisolone in treating intrauterine adhesions in a rat model.

Hyaluronic acid is a linear polysaccharide made up of repeating units of sodium D-glucuronate and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, and plays a fundamental role in various body tissues and fluids, offering physical support and protection. It not only functions as a mechanical barrier but also promotes fibrin dissolution and mesothelial cell growth, while suppressing inflammatory responses and aiding wound healing.. Recent studies have shown that intraperitoneal administration of hyaluronic acid significantly reduces adhesions [

19]. Despite its widespread use to prevent adhesion formation after surgical adhesiolysis, the impact of hyaluronic acid gel on pregnancy rates remains debated.

Research on Asherman Syndrome using experimental models is limited. Notably, there are no studies in the literature that explore the combined use of methylprednisolone and hyaluronic acid for treating this condition. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of methylprednisolone alone and in combination with hyaluronic acid in an experimentally induced Asherman Syndrome in a rat model.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, the experimental induction of Asherman Syndrome (AS) and the subsequent treatment protocols were conducted according to previously established standardized methods. The surgical principles described by Jing et al. [

20] and Hunter et al. [

21] were followed for the creation of the AS model, while the trichloroacetic acid (TCA) application adhered to the protocol outlined by Kılıç et al. [

22].

2.1. Animals and Ethical Approval

A total of 26 non-pregnant female Sprague-Dawley rats (200-250 g) were used. Ethical approval was obtained from the Yeditepe University Animal Experiments Ethics Committee (HADYEK: 2022/01-2), and the study was conducted in accordance with international guidelines (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals).

2.2. Study Design and Estrous Cycle Assessment

All animals underwent a 1-week acclimatization period. During this time, vaginal cytology was performed to determine the estrous cycle phase, ensuring that surgical and experimental interventions were timed consistently across all animals.

2.3. Establishment of the Asherman Syndrome Model

The AS model was created following the principles reported by Jing et al. [

20] and Hunter et al. [

21]. For anesthesia, 6 mg/kg Xylazine-HCl (Rompun®, Bayer, Istanbul) and 85 mg/kg Ketamine-HCl (Keta-control®, Mefar Ilac, Istanbul) were administered intramuscularly. After shaving and disinfecting the abdominal area, a 2 cm laparotomy incision was made. The right uterine horn was gently clamped at the top and cervical levels. Following the Kılıç et al. [

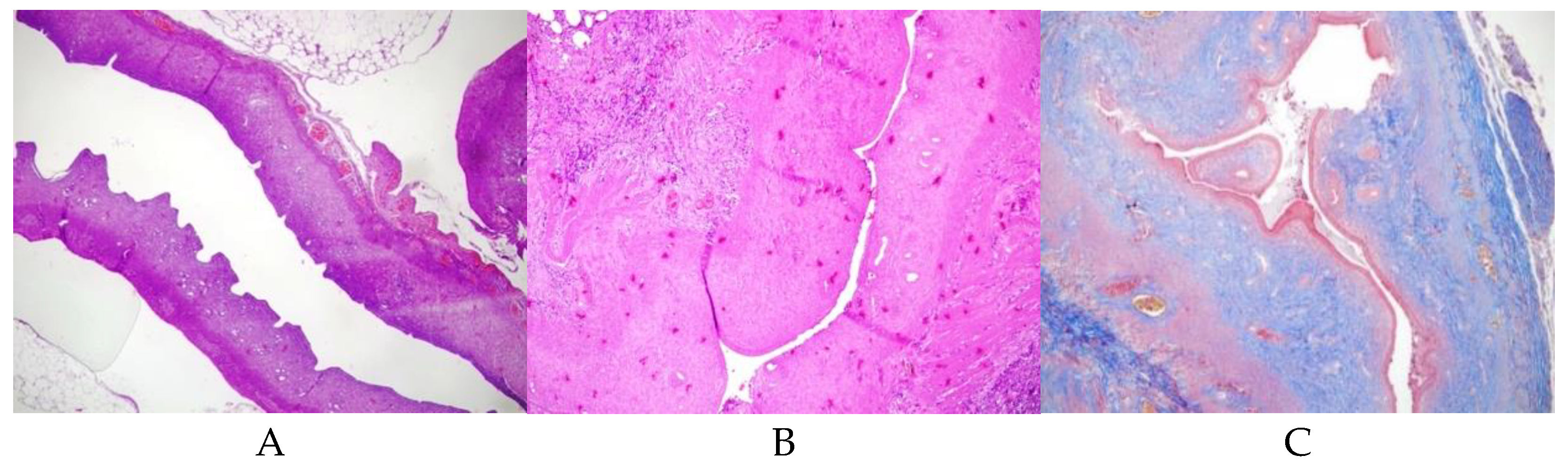

22] protocol, 0.1 ml of TCA (IL 33®, Istanbul Ilac Sanayi ve Ticaret AS, Istanbul) was injected into the right uterine horn with an insulin syringe. A sponge was used to prevent acid leakage, and the abdomen was irrigated with sterile saline before closure. The uterus was allowed to develop adhesions over 14 days. Initially, AS formation was confirmed histologically in 2 rats, and subsequently, the same procedure was applied to the remaining 24 rats (

Figure 1)After a postoperative loss of 4 rats, 22 rats remained and were randomly assigned to experimental groups.

2.4. Groups and Treatment Protocols

Group 1 (Control, n=2): AS model induced, no further treatment (

Figure 1). This group was conducted solely to confirm the induction of Asherman Syndrome using TCA, and in subsequent groups, it was accepted that Asherman Syndrome was induced with TC.

Group 2 (Hyaluronic Acid, n=7): Fourteen days (approximately 3 estrous cycles) post-AS induction, a second laparotomy was performed, and 0.01 ml of low molecular weight hyaluronic acid was injected into the right uterine horn.

Group 3 (Methylprednisolone, n=6): Fourteen days post-AS induction, 1 mg/kg p.o. methylprednisolone was administered daily for 2 weeks.

Group 4 (Combined Treatment, n=7): Fourteen days post-AS induction, a second laparotomy was performed for intrauterine injection of 0.01 ml hyaluronic acid, and 1 mg/kg p.o. methylprednisolone was given daily for 2 weeks.

All procedures were performed under similar conditions and within the same timeframe to maintain experimental parallelism and ensure that all animals were exposed to comparable environmental, physiological, and hormonal conditions.

By referencing these established protocols [

20,

21,

22,

23] and clearly detailing the experimental steps, the methodology is both standardized and transparent, increasing the study’s reproducibility, reliability, and clarity for the readers.

2.5. Pathological Evaluation

Hematoxylin and eosin staining: The shape of the endometrial epithelium, gland structure and number, uterine wall diameters, uterine cavity lumen, and inflammation level were evaluated with semi-quantitative inflammation scoring using hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Masson's trichrome staining: The severity and extent of fibrosis in the uterus and the fibrosis area ratio (fibrosis area / analyzed uterine area x100) were evaluated. Fibrosis areas were determined as a percentage. Grade 0: no fibrosis; Grade 1: minimal fibrous tissue increase; Grade 2: irregular fibrous tissue increase; Grade 3: concentric fibrosis, hyalinization was present.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed by ThermoScientific Immunostaining for anti-VEGF (PB9071 Boster Bio). The degree of staining for VEGF was scored as positively stained glandular or stromal cells in the selected area. Negative staining was defined as the absence of VEGF signal in stromal or glandular cells (immunohistochemical [IHC] score: 0). Staining in <20% (IHC score: 1). VEGF staining in 20-60% (IHC score: 2). VEGF(+)in >60% (IHC score:3) [

23].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

This study used SPSS 24.0 IBM statistical package program. The data was analyzed at 95% confidence intervals. Descriptive statistics are given as mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum values. We used Shapiro-Wilk's test for normality testing. Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskall Wallis test analyzed pairwise group comparisons that did not show a normal distribution. The analysis used p<0.05 for statistical significance.

3. Results

Adhesion formation was confirmed histologically after trichloroacetic acid use (

Figure 1). The uterine wall thickness of the right uterine horn was significantly reduced in Group 1 (p:0.004), and Group 2(p:0.035). Group 3 and Group 4 had similar uterine wall thickness in the right and left horns.

Table 1 shows the uterine wall thickness of the right and left horns.

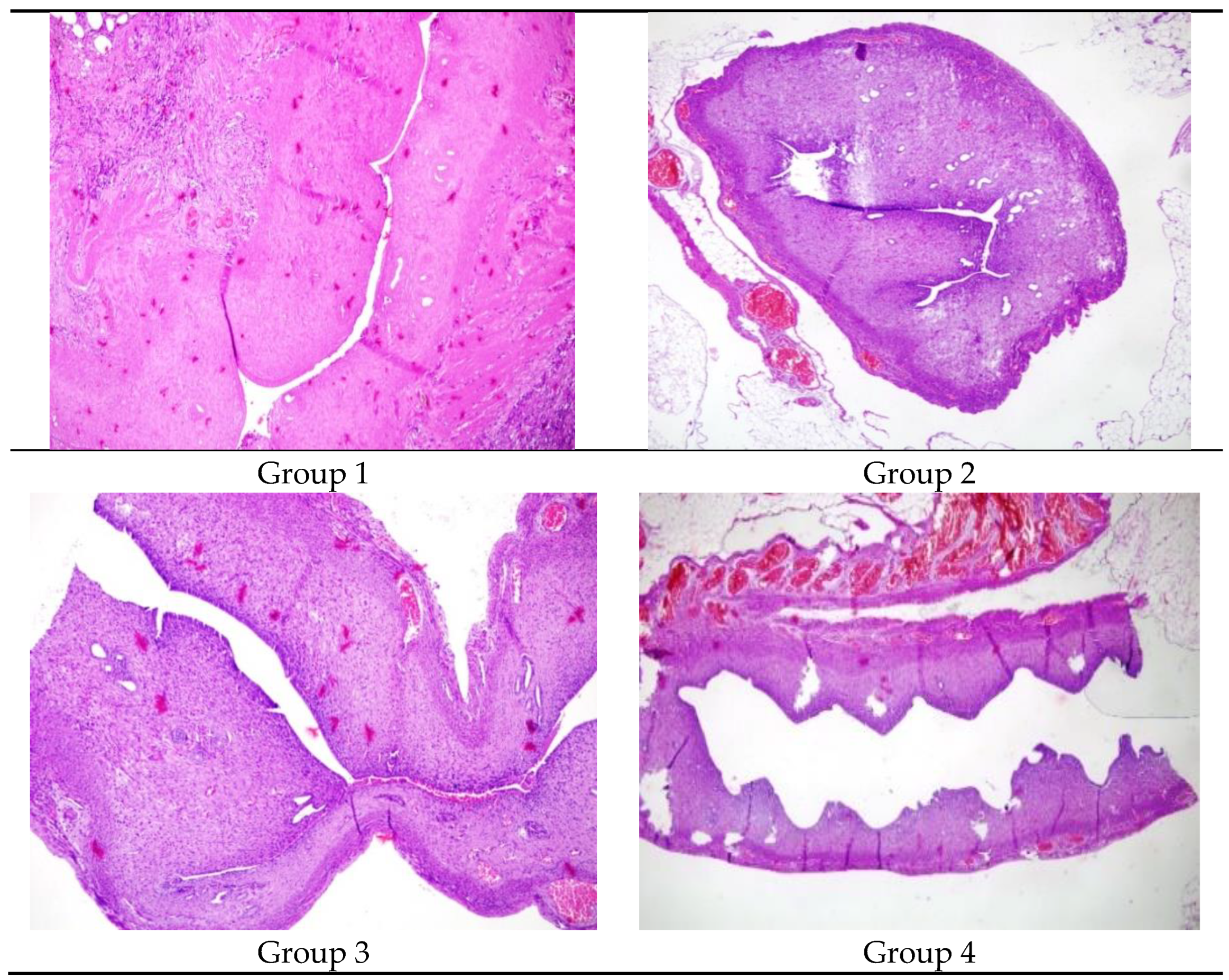

Figure 2 The comparison of the lumen dimater in Group 1, Group 2, Group 3 and Group 4 X100 Hemotoxylene& Eosine)

Table 2 shows the comparison of the right and left uterine cavity. Group 1 had a significantly decreased lumen diameter in the right uterine horn compared to the left (p:0.04). The uterine lumen diameters of the right and left horns were similar in Group 2, Group 3, and Group 4 (p>0.05).

Group 1 (p:0.029) and Group 2 (p:0.039) had a decreased glandular count in the right horn compared to the left. Group 3 and Group 4 had similar glandular counts in the right and left uterine cavities (p:0.077 and 0.847 respectively).

Table 3 shows the glandular counts of the right and left uterine cavities.

The right uterine cavity of Group 1 and Group 2 had increased inflammation compared to the left. Group 3 and Group 4 had similar inflammation levels in the right and left uterine cavity. Group 1 and Group 2 had significantly increased fibrosis in the right uterine cavity (p:0.007 and 0.024 respectively). Group 3 and Group 4 had similar fibrosis in the right and left uterine cavity.

Table 4 demonstrates inflammation and fibrosis.

Group 1 and Group 3 had significantly decreased VEGF staining in the right uterine cavity (p:0.011). Group 2 and Group 4 had similar VEGF staining levels in the right and left uterine cavities.

Table 5 shows the immunohistochemical results of VEGF level.

The groups with treated right uterine horns (Groups 2, 3, 4) were compared to the group with only Asherman Syndrome induced (Group 1) regarding lumen diameter, uterine wall thickness, gland count, inflammation (VEGF), and fibrosis (MT) levels using the Kruskal-Wallis test. According to the test results, a statistically significant difference was observed in inflammation levels and lumen diameter between the treated groups and the untreated group with induced Asherman Syndrome (p < 0.05).

Post-hoc analyses following the Kruskal-Wallis test indicated that this significant difference was associated with the hyaluronic acid treatment. Hyaluronic acid treatment resulted in a significant difference in increased lumen diameterand reduced inflammation levels in Asherman Syndrome. These findings suggest that hyaluronic acid has beneficial effects in the treatment of Asherman Syndrome, particularly in preserving uterine lumen diameter and reducing inflammation.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the role of intrauterine hyaluronic acid and oral steroid usage in the treatment of Asherman Syndrome in an experimental rat model. Hyaluronic acid treatment facilitated uterine cavity expansion, while combined hyaluronic acid and steroid treatment resulted in increased uterine cavity expansion and VEGF levels, along with a significant reduction in fibrosis and inflammation. The results of this study indicated that both methylprednisolone and hyaluronic acid treatments significantly improved uterine healing in a rat model of Asherman Syndrome.

Corticosteroids are used in the treatment of many inflammatory and immune dysfunction diseases due to their significant anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects. It modulates immune function through a variety of effects in the nuclei of numerous cells.

Steroids are used in many entities such as reducing keloid scars, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and preventing fibrosis in autoimmune hepatitis. However, it is not used in gynecology, especially to prevent intrauterine adhesion formation. This study investigated the effects of methylprednisolone use on the uterine cavity with Asherman syndrome.Methylprednisolone treatment alone increased uterine wall thickness, lumen diameter, gland count, and VEGF levels while reducing fibrosis and inflammation scores. Hyaluronic acid treatment primarily increased lumen diameter and VEGF levels.

Asherman Syndrome presents with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations such as menstrual irregularities, oligo-hypomenorrhea, infertility, or recurrent pregnancy losses, making it a challenging condition for clinicians to treat. There is still no consensus on the optimal method to prevent Asherman Syndrome after intrauterine surgeries. Currently, there are many alternative approaches for the treatment of Asherman Syndrome. A commonly used method has been dilation and curettage. However, this blind procedure has a low treatment success rate and increases the risk of uterine perforation [

24]. Today, hysteroscopy has replaced this methods. Hysteroscopy not only confirms the diagnosis of intrauterine adhesions but also provides a means of treatment. However, complications such as recurrent adhesion formation, uterine perforation, hemorrhage, and infection can occur during hysteroscopy [

24,

25]. The increasing rates of cesarean sections and intrauterine surgeries have made Asherman Syndrome an incirising problem, necessitating the search for new treatments.

In a study by Kilic et al., an experimental Asherman model was created in 2 rats by injecting trichloroacetic acid into the uterine horns. Intrauterine adhesions were observed 2 weeks later using light microscopy [

22]. Similarly, we used trichloroacetic acid to induce Asherman Syndrome and histopathologically confirmed it as an effective method.

In a double-blind randomized clinical trial by Tafti et al., 65 women who underwent uterine septum resection were divided into 2 groups. One group received 1 cc of hyaluronic acid gel immediately after the septal resection, while the control group received 1 cc of normal saline solution as a placebo injected into the uterine cavity. Two months later, the presence of intrauterine adhesions was examined by hysteroscopy in both groups. The study found that hyaluronic acid treatment significantly reduced the risk of developing Asherman Syndrome in women with endometrial damage after septal resection surgery [

26]. Alponat et al. used physical barriers such as hyaluronic acid to prevent almost inevitable adhesion formation after incisional hernia repair with prosthetic mesh. These barriers were reported to reduce intra-abdominal adhesions [

27]. Human studies with hyaluronic acid have shown that intrauterine hyaluronic acid administered postoperatively reduces adhesions and has a positive effect on the endometrium [

27].

Corticosteroids inhibit cytokine formation and release, reducing fibroblast proliferation and thereby preventing fibrosis formation [

9]. Additionally, steroids inhibit early stages of inflammation and collagen deposition, providing anti-inflammatory effects. We hypothesized that by administering steroid therapy, we could prevent adhesion formation by reducing inflammation and fibrosis formation. In our study, significant reductions in fibrosis and inflammation were observed in the steroid-treated group.

A study by Zheng et al. demonstrated that hyaluronic acid gels can significantly reduce the incidence of intrauterine adhesions after intrauterine surgery. The study also demonstrated that hyaluronic acid gels significantly improved pregnancy rates following intrauterine surgery. However, the small sample sizes and short follow-up periods of the study may have influenced the overall analysis. Therefore, longer follow-up periods and larger sample sizes are necessary to fully evaluate the efficacy of hyaluronic acid gels in preventing adhesions following intrauterine surgery [

28]. In this study, the effects of hyaluronic acid (HA) on fibrosis were investigated. Our findings indicated that the application of HA alone does not significantly reduce fibrosis. However, when HA is combined with steroids, a significant reduction in fibrosis was observed. In the literature, the role of HA in fibrosis development remains controversial. Some studies suggest that high molecular weight forms of HA possess anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic properties, while others propose that HA may exhibit pro-fibrotic effects. These conflicting results indicate that the effects of HA on fibrosis are complex and context-dependent. Our findings suggest that HA alone is insufficient to reduce fibrosis, but when used in combination with steroids, it can produce a synergistic effect. This highlights the potential role of HA in fibrosis management when combined with anti-inflammatory therapies.

Regarding the limitations of our experimental model, the first and most important limitation is that animal experiments may not directly translate to humans. A second important limitation is the duration of the experiment. Although the 15-day treatment period corresponds to a 3-4 month cycle in humans considering the estrous cycle of rats is 4-5 days, the long-term effects on the endometrium cannot be definitively stated. Another significant limitation is the relatively small number of rats. Despite the median values of all parameters being parallel, the statistical significance could not be achieved in some parameters due to the small number of rats in the various groups.

5. Conclusion

Hyaluronic acid treatment is one of the prominent therapeutic methods today. The most important result obtained from our study model was that the combined treatment of hyaluronic acid and steroids statistically significantly improved the histopathological findings of Asherman Syndrome. These findings suggest that the combined treatment of hyaluronic acid and steroids may hold promise for clinical use in Asherman Syndrome. There is a need for future clinical studies on this topic. New therapeutic approaches that prevent fibrosis resulting from IUA and causing infertility could be promising in treating Asherman-induced infertility.

Author Contributions

Mehmet Genco, Fisun Vural, and Merve Genco conceptualized and designed the research study. Mehmet Genco and Merve Genco performed the experiments and acquired the data. Mehmet Genco, Merve Genco, and Nermin Koç provided technical guidance and advice on data analysis. All authors contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Yeditepe University Animal Ethics Committee (HADYEK: 2022/01-2).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available upon request. The materials used in the study are also accessible upon request for research purposes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. We also appreciate the contributions of the reviewers and the editor for their valuable feedback during the evaluation process. We sincerely thank everyone who supported us in completing this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fritsch, H. (1894). Ein fall von volligem schwund der gebormutterhohle nach auskratzung. Zentral Gynaekol, 18, 1337-1342.

- Asherman, J.G. (1948). Amenorrhoea traumatica (atretica). BJOG: An International.

- Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 55, 23-30. [CrossRef]

- Myers, E.M., and Hurst, B.S. (2012). Comprehensive management of severe.

- Asherman syndrome and amenorrhea. Fertility and Sterility, 97, 160-164. [CrossRef]

- Asherman, J.G. (1950). Traumatic intra-uterine adhesions. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 57, 892-896. [CrossRef]

- International Asherman's Association. (2018). What is Asherman's Syndrome. IAA. URL: http://www.webcitation.org/query?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ashermans.org&date=2018-01-17.

- Gordon, A. G. (2018). Complications of hysteroscopy. GFMER. URL: http://www.webcitation.org/query?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.gfmer.ch%2FBooks%2FEndoscopy_book%2FCh24_Complications_hyster.html&date=2018-01-17.

- Friedler, S., Margalioth, E.J., Kafka, I., and Yaffe, H. (1993). Incidence of postabortion intra-uterine adhesions evaluated by hysteroscopy-a prospective study. Human Reproduction, 8, 442-444. [CrossRef]

- Alviggi, C., Mollo, A., De Placido, G., and Magos, A. (2013). The management of Asherman syndrome: a review of literature. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 11, 118. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D., Wong, Y.M., Cheong, Y., Xia, E., and Li, T.C. (2008). Asherman syndromeone century later. Fertility and Sterility, 89, 759-779. 1. [CrossRef]

- İnternet: Gordon, A. G. Complications of hysteroscopy. GFMER. URL: http://www.webcitation.org/query?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.gfmer.ch%2FBooks.

- %2FEndoscopy_book%2FCh24_Complications_hyster.html&date=2018-01-17, Son Erişim Tarihi: 17.01.2018.

- Yang, J.H., Chen, C.D., Chen, S.U., Yang, Y.S., and Chen, M.J. (2016). The influence of the location and extent of intrauterine adhesions on recurrence after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 123, 618-623. 94. [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, H. and Adeghe, J. (2004). Severe early-onset intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) in a woman with Asherman's syndrome. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 24, 312-314. [CrossRef]

- Cai Y, Wu F, Yu Y, et al. Porous scaffolds from droplet microfluidics for prevention of intrauterine adhesion. Acta biomaterialia. 2019;84:222-30. [CrossRef]

- Boland GM, Weigel RJ. Formation and prevention of postoperative abdominal adhesions. J Surg Res 2006; 132: 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Haynes RC Jr. Adrenocorticotropic hormone; adrenocortical steroids and their synthesis and action of adrenocortical hormones. In: Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 8th Edition, New York: Oxford Pergomon Press 1990: 1431-1462.

- Rein DT, Schmidt T, Bauerschmitz G, Hampl M, Beyer IM, Paupoo AAV, vd. Treatment of endometriosis with a VEGF-targeted conditionally replicative adenovirus. Fertility and Sterility. Mayıs 2010;93(8):2687-94. [CrossRef]

- Anaf V. Relationship between endometriotic foci and nerves in rectovaginal endometriotic nodules. Human Reproduction. 01 Ağustos 2000;15(8):1744-50. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Sun J, Li X, et al. Antifibrotic Effects of Decellularized and Lyophilized Human Amniotic Membrane Transplant on the Formation of Intrauterine Adhesion. Experimental and clinical transplantation: official journal of the Middle East Society for Organ Transplantation. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Buckley C. Normal endometrium and non-proliferative conditions of the endometrium. Obstetrical and gynaecological pathology. 2003;5:391-442.

- Jing Z, Qiong Z, Yonggang W, Yanping L. Rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells improve regeneration of thin endometrium in rat. Fertile Steril 2014; 101:587-94. [CrossRef]

- Hunter II RK, Nevitt CD, Gaskins JT, Keller BB, Bohler HC Jr, LeBlanc AJ. Adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction cell effects on a rodent model of thin endometrium. Plos One 2015; 10(12):E0144823. [CrossRef]

- Kilic S, Yuksel B, Pinarli F, et al. Effect of stem cell application on Asherman syndrome, an.

- Seval Yılmaz Ergani, Berna Dilbaz, Hasan Murat Ergani , Özlem Moraloğlu Özdemir Effect of intrauterine ozone therapy on Asherman syndrome, an experimental rat model r J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2022 Oct:277:90-96. experimental rat model. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2014;31(8):975-82.

- Conforti A, Alviggi C, Mollo A, De Placido G, Magos A. The management of Asherman syndrome: a review of literature. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology.2013;11(1):118. [CrossRef]

- Roge P, D'ercole C, Cravello L, Boubli L, Blanc B. Hysteroscopic management of uterine synechiae: a series of 102 observations. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1996;65(2):189-93. [CrossRef]

- 29. Seiede Zahra Ghanadzadeh Tafti 1, Atiye Javaheri 1, Razieh Dehghani Firoozabadi 2, Samane Kabirpour Ashkezar 1, Hossein Falahzadeh Abarghouei 3.

- Alponat A, Lakshminarasappa SR, Yavuz N, Goh PM. Prevention of adhesions by Seprafilm, an absorbable adhesion barrier: an incisional hernia model in rats. Am Surg 1997; 63: 818- 819.

- Fei Zheng Xin Xin Fei He Jianyong Liu Yuechong Cui Meta-analysis on the use of hyaluronic acid gel to prevent intrauterine adhesion after intrauterine operations Am J Obstet Gynecol. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).