1. Introduction

Modern management of mares introduced to artificial insemination (AI) and other reproductive techniques requires the use of hormonal agents to induce estrus and ovulation (wojtysiak 2020, squires 2008, samper 2008). Due to the seasonal pattern of the estrus cycle in mares, different methods are used for estrus induction during the spring transition period compared to the breeding season. During the breeding season, the most commonly method used for estrus induction involve the administration of prostaglandin F2α or its analogues (prostaglandins) during the diestrus stage of the estrus cycle. Dinoprost is a natural prostaglandin F2α available on the market, while the most commonly used synthetic analogs of prostaglandin F2α in veterinary practice are cloprostenol and luprostiol. The effect of prostaglandins, measured as the time to ovulation, mainly depends on the diameter of the largest follicle present on the ovary at the time of drug administration. For follicles smaller than 25 mm in diameter, the time to ovulation ranges from 6 to 12 days (Coffman and Pinto 2016), though it can range from 2 to 16 days (Newcombe 2008, Curveo-Arango and Newcombe 2009). It can be said with high probability that the larger the follicle at the time of drug administration, the shorter the time to subsequent ovulation. Generally, the majority of mares will respond with luteolysis after a single administration of prostaglandins, starting from the 5th day after ovulation however, some mares may respond even earlier (Coffman and Pinto 2016). The effect of the treatment can also depend on the agent used (Kuhl et al. 2017) and the dose (Newcombe et al. 2008). The recommended dose of dinoprost is 5 mg per mare, while the recommended dose for d,l-cloprostenol is 250 µg per mare (Samper 2008). Regardless of the information presented above, it is easier to predict the effect of treatment if the genital tract is examined before drug administration, rather than when prostaglandins are administered blindly. Therefore, the first aim of this study was to assess the effect of prostaglandins given after ultrasonographic examination of the ovaries on estrus induction. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is another hormone widely used in horse reproduction. This hormone has a relatively long half-life and acts similarly to LH (Squires 2008). The effect of this hormone, manifested as the induction of ovulation, can be achieved after administration during estrus when a dominant follicle is present on the ovary. Ovulation usually occurs 24-48 hours after drug administration (Barbacini et al. 2000). The recommended dose ranges from 1500 to 6000 IU of hCG, however, 750 IU can also be successful (Davies Morel and Newcombe 2008). It has also been indicated that after hCG administration, the growth of the dominant follicle can be halted and the endometrial edema pattern can decreases (Gastal et al. 2006, Curveo-Arango and Newcombe 2008, Dolezel et al. 2012). Therefore, the second aim of this study was to assess the effect of hCG on the growth of the dominant follicle, changes in the endometrial edema pattern, and its direct effect on the timing of ovulation in relation to the progression of the breeding season. It is also suggested that hormonal manipulation of the estrous cycle and induction of ovulation may increase the frequency of double or even multiple ovulations (MO) (Veronesi et al. 2003, Ginther and Al-Mamun 2009). In our study in estruses induced after the administration of prostaglandins, hCG was routinely administered, which allows us to compare the effect of this drug on ovulation in spontaneous and induced estrus cycles. From the other perspective, we could estimate whether the administration of prostaglandins can increase the frequency of MO. Therefore, the third aim of this study was to assess the effect of prostaglandins and hCG on the induction of MO.

2. Materials and Methods

Data for analysis were collected from clinical records during the three breeding seasons from 2021 to 2023 at an artificial insemination centre located in the Wielkopolska region of Poland. All mares introduced for AI were Warmblood and were considered normal, as their owners did not report any reproductive problems. The majority of mares were multiparous. Additionally, all mares had normal perineal conformation (with over 80% of the labial length lying below the ischiadic arch of the pelvis).

Ultrasound examination of the reproductive tract was performed using ultrasound machine Honda HS-1600, equipped with a linear probe operating at a frequency of 5 MHz. During each ultrasound examination, the diameter of the dominant follicle(s) and the endometrial edema score were recorded. Endometrial edema was evaluated based on the schema described by Samper (2010) and modified by Rasmussen et al. (2015), where a score of 0 indicates no edema, a score of 1 indicates mild edema, a score of 2 indicates moderate edema, a score of 3 indicates strong edema, and a score of 4 indicates abnormal hyperedema (Grabowska and Kozdrowski, 2022).

Mares were divided into two groups based on the status of estrus (spontaneous or induced). The first group (hCG group, n=77, aged 8.04±5.56 years) consisted of mares with spontaneous estrus (either they arrived at the insemination center already in estrus, or they waited there until estrus occurred). In this group, ovulation was induced by the administration of 1500 IU of hCG (Chorulon®, Intervet, Holland) intravenously when the dominant follicle was at least 4 cm in diameter and endometrial edema was pronounced. The second group (PGF/hCG group, n=40, aged 10.13±5.26 years) consisted of mares with induced estrus via intramuscular injection of 250 µg of cloprostenol (Estrumate®, Intervet, Holland). Administration of cloprostenol was preceded by transrectal palpation and ultrasonography of the genital tract. The injection was performed if the endometrial edema score was 0, a corpus luteum or hemorrhagic anovulatory follicle was visible on the ovary, and the diameter of the follicles was no greater than 30 mm. Three to four days after the cloprostenol injection, a genital tract examination was performed, and if necessary, it was continued daily until estrus detection. In this group, hCG was also administered in the same manner and under the same conditions as described for the hCG group.

In the hCG group, 67 cases of first inseminations and 10 cases of second inseminations during the breeding season were analyzed, while in the PGF/hCG group, 33 cases of first inseminations and 7 cases of second inseminations were analyzed.

Mares inseminated with frozen/thawed semen (all mares from hCG group, and six mares from PGF/hCG group) were examined ultrasonographically after hCG treatment at intervals of 4-6 hours (usually starting 12-24 hours after hCG administration) until ovulation occurred, and again 24 and 48 hours after AI. Mares inseminated with cooled semen (34 mares from PGF/hCG gropu) were examined ultrasonographically after hCG treatment at intervals of 24 hours (usually starting 12-24 hours after hCG administration) until ovulation occurred, and again 24 and 48 hours after AI. After hCG administration, in both groups, changes in the diameter of the dominant follicle(s), changes in endometrial edema, and the time of ovulation were recorded. Additionally, in the PGF/hCG group, the time from cloprostenol administration to estrus detection, to hCG administration, and to ovulation was recorded. In both groups, the frequency of multiple ovulations and twin pregnancies were recorded and compared between groups.

AI with cooled semen was performed approximately 24 hours after hCG treatment, while AI with frozen/thawed semen was performed 4-6 hours after ovulation. AI was preceded by tail protection with a glove, and the perineum and vulva were washed with warm soapy water, scrubbed with povidone, and dried with a paper towel. Cooled semen was imported from various European centres from stallions with proven fertility. Each dose of cooled semen contained more than 500 × 106 spermatozoa with motility above 75%. The dose of frozen/thawed semen varied from one to six straws with motility ranging from 20-60%, but the number of spermatozoa was unknown. Cooled semen was deposited into the uterine body, while frozen/thawed semen was deposited near the uterine papilla using a sterile flexible catheter introduced into the uterus via the vagina, with a gloved hand. Ultrasound examination for pregnancy diagnosis was performed 14-16 days after ovulation.

To address the research questions, statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 13 software (TIBCO Software Inc., 2017). Descriptive statistics were calculated, followed by the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality, the Mann-Whitney test, and the Kruskal-Wallis test. To determine differences between groups, a post-hoc Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction was conducted. Additionally, relationships between categorical variables were analyzed using contingency tables with the chi-square independence test. Correlations between variables were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted.

3. Results

In the hCG group, 43 mares were pregnant (55.8% pregnancy rate), while in the PGF/hCG group, 26 mares were pregnant (65% pregnancy rate); however, the differences were not statistically significant (p<0.073). The interval from the administration of cloprostenol to estrus detection was 5.03±1.94 days, the time from cloprostenol administration to hCG injection was 6.28±2.01 days, and the time from cloprostenol administration to ovulation was 8.06±2.14 days. During the first examination after the cloprostenol injection, 57.5% (23/40) of the mares were in estrus.

The distribution of ovulations over time after hCG administration is presented in

Table 1. The majority of ovulations in both groups occurred up to 48 hours after hCG injection, with no significant differences between the groups (p = 0.09). In the hCG group, 97.4% of ovulations occurred within 48 hours after hCG administration, while in the PGF/hCG group, 95.0% of ovulations occurred within the same timeframe.

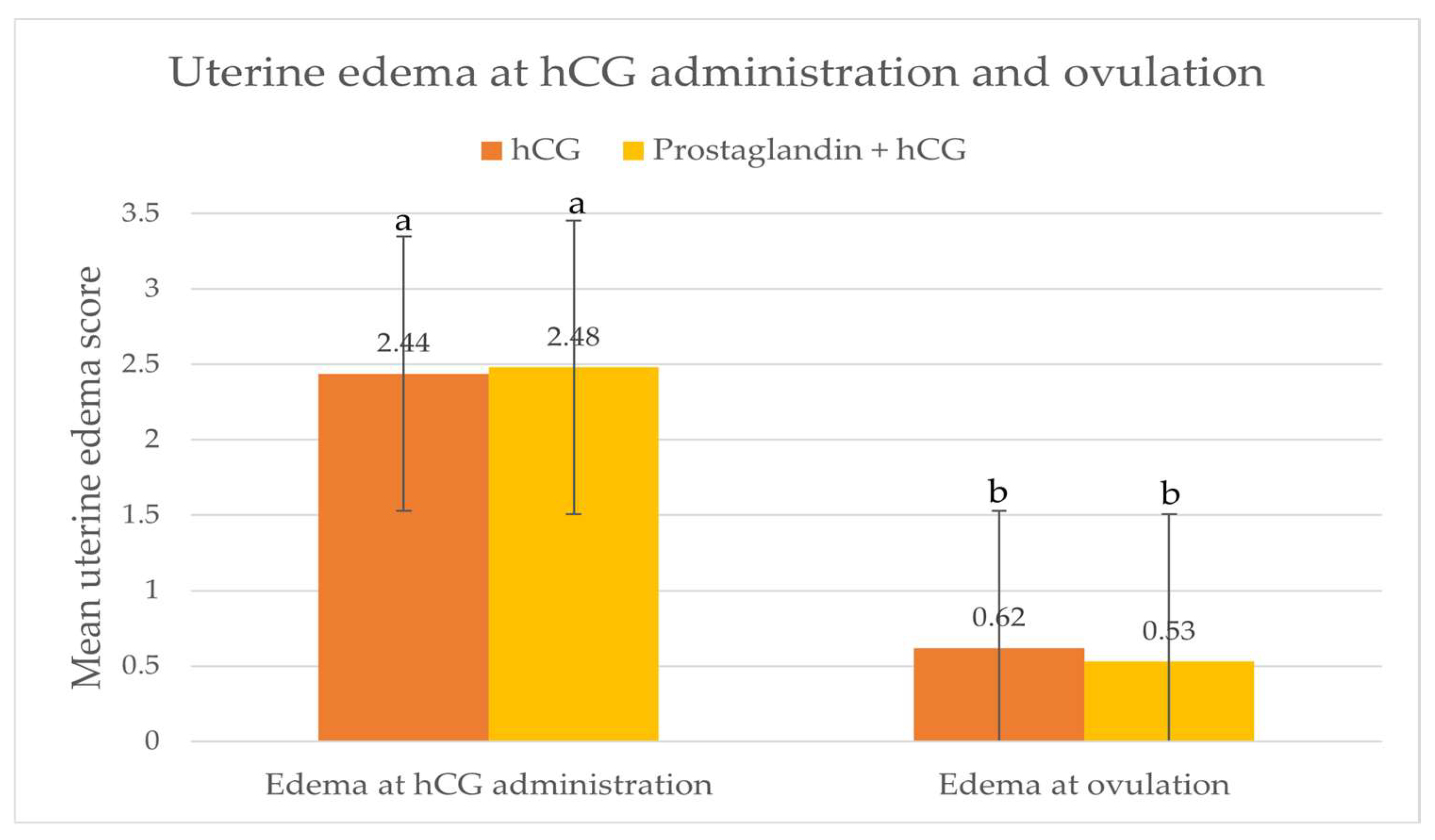

The frequency of MO was statistically higher in the PGF/hCG group, with 11 out of 40 mares (27.5%) having MO, compared to only 3 out of 77 mares (3.9%) in the hCG group (p<0.0006). However, hormonal treatment did not affect the frequency of MP (one twin pregnancy in the hCG group and two twin pregnancies in the PGF/hCG group, i.e., 1.3% and 4.88%, respectively, in the hCG and PGF/hCG groups). Endometrial edema scores at the time of hCG administration and at ovulation did not differ between groups, but they significantly decreased over the time in both groups (

Figure 1).

The values for the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (rs) calculated in both the hCG and PGF/hCG groups between pregnancy rates and mare age, endometrial edema at the time of hCG administration, and ovulation are shown in

Table 2. Only the endometrial edema score measured at the time of hCG administration in the hCG group showed a positive correlation with fertility.

4. Discussion

Typically, the pregnancy rate after AI with frozen semen is lower than after AI with cooled semen (Katila 2003). A higher, though not statistically significant, pregnancy rate in mares in the PGF/hCG group can be partially explained by the fact that the majority of mares in this group were inseminated with cooled semen. However, some studies suggest that fertility rates after the use of frozen/thawed semen can sometimes exceed those achieved with cooled semen (Crowe et al. 2008). In our study, all mares were under careful veterinary supervision, and it can be concluded that proper management can lead to satisfactory and comparable pregnancy rates after AI with either frozen/thawed or cooled semen.

It has been shown that induction of estrus or ovulation does not affect fertility in artificial insemination programs or in natural mating (Barbacini et al. 2000, Morris and Allen 2002, Allen et al. 2007, Metcalf and Thompson 2010). Thus, hormonal manipulation of the estrus cycle during the breeding season or induction of ovulation can guarantee similar reproductive efficacy to that of spontaneous estrus without ovulation induction. Undoubtedly, the use of prostaglandins to induce estrus facilitates the management of the mare. Similarly, induction of ovulation with hCG improves the prediction of the best time for AI.

The first examination for estrus detection was performed three to four days after cloprostenol administration, as the onset of estrus typically occurs 3-4 days after treatment (Samper 2008). At that time, more than 50% of mares were in estrus. It has been shown that the interval from induction of luteolysis using cloprostenol to induction of ovulation and to ovulation itself is on average 5.1 and 7.2 days, respectively (Kuhl et al. 2017). In our study, induction of ovulation, and next ovulation occurred about one day later than in the study by Kuhl et al. (2017). After induction of luteolysis using prostaglandins, fertility rates are better when ovulation occurs more than eight days after hormone injection, compared to ovulations occurring up to six days or between six to eight days (Cuervo-Arango et al. 2015). In our study, the mean time to ovulation was longer than eight days, and the fertility rate was also high, reaching 65%. Conclusions from other studies also support the idea that earlier ovulation after prostaglandin treatment results in poorer fertility (Cuervo-Arango and Newcombe, 2007). The high fertility rate in our study may be partially explained by the fact that the majority of mares ovulated within two days after hCG treatment. Samper et al. (2002) showed that the ovulation rate after inducing luteolysis with prostaglandins and subsequent i.v. injection of 2500 IU of hCG was 83.3% at 48 hours, 91.6% at 72 hours, and 100% at 96 hours. Treatment with hCG is considered satisfactory if ovulation occurs up to 48 hours after drug administration. Within this time frame, ovulations occurred in 73.8% of cycles in the study by Green et al. (2007), in 78.4% of cycles in the study by McCue et al. (2004), and in 91% of cycles in the study by Barbacini et al. (2000). In our study, hCG was administered only when a high endometrial edema score was measured, and more than 95.0% of ovulations occurred within 48 hours after drug administration. This finding fully corresponds with the results obtained by Sieme et al. (2003), who used the same dose of hCG as in our study. Additionally, administering hCG when the endometrial edema score is high can guarantee a response to this agent in over 95% of cases during the first two cycles (Samper, 1997).

Barbacini et al. (2000) claim that repeated injections of hCG during the breeding season do not negatively impact the efficacy of this drug, as measured by the occurrence of ovulation up to 48 hours after hormone administration. In contrast, McCue et al. (2004) and Green et al. (2007) showed that the efficacy of hCG declines as the number of treatments increases during the breeding season. In our study, the majority of observations were made after the first hCG administration during the breeding season, which may explain the high ovulation rate in both groups within two days of drug administration. It must be noted that different doses of hCG and different routes of drug administration were used in the studies. For example, 1500 IU s.c. (Cuervo-Arango and Newcombe, 2008), 1500 IU i.v. (Kuhl et al., 2017), 2500 IU i.v. (Samper et al., 2002), 750 and 1500 IU s.c. (Morel and Newcombe, 2008), 2000 IU i.v. (Barbacini et al., 2000), and 3000 IU i.v. (Dolezel et al., 2012). These variations may partially explain the differences observed among studies. In our study, we used 1500 IU, which is a relatively small dose, but the obtained results confirm the effectiveness of this dose. This treatment is cost-effective, and smaller doses of hCG may have a lesser negative impact on the success of treatment with additional hCG doses later in the breeding season, for mares requiring repeated AI to become pregnant. However, this hypothesis should be critically evaluated. It was even shown that a dose of 750 IU is as effective as a dose of 1500 IU (Morel and Newcombe, 2008).

Generally, a decrease in endometrial edema before ovulation is a good prognostic factor for ovulation and pregnancy. In our observations, a significant reduction in endometrial edema was noted in both groups after hCG administration. Green et al. (2007) showed that an increase in endometrial edema score measured to 24 h after hCG administration was noted in 17.0% of cycles, a decrease in edema score was observed in 44.7% of cycles, and no change in edema score was noted 38.3% of cycles. Increasing in endometrial edema at that time is less likely to ovulate from 24 to 48 h than in mares where endometrial edema decreased. So decreasing of endometrial edema after hCG administration is good prognostic indicator for occurrence of ovulation within 24-48 h after drug administration. Generally, as ovulation approach the uterine edema is decreased (Gastal et al. 1998; Cuervo-Arango and Newcombe 2008, Dolezal et al., 2012), but in induced cycles endometrial edema may be slightly higher than in non-induced cycles (Cuervo-Arango and Newcombe 2008). However, Gastal et al., (2006) showed that endometrial edema in the period 24-36h after treatment with hCG is lower than in non-treated mares, and corresponds to changes in systemic oestradiol concentration. Dolezal et al., (2012) showed that decreasing of endometrial oedema was higher in mares treated with hCG given when dominant follicle had diameter 35-40 mm than in mares treated with hCG when dominant follicle had diameter more than 40 mm and in mares with spontaneous ovulation however, but degree of endometrial oedema before ovulation was not different among groups.

Twin or multiple pregnancies are associated in horses with several serious complications as abortion, dystocia, and neonatal death, and direct reason of MP is MO. Occurrence of MP in mares oscillate in the range of few percentage, and is more likely to occur in Thoroughbred mares, in older mares, in some family lines, as well as some studies report that hormonal manipulation of the estrus cycle and ovulation can promote MO and frequency of twins (Allen et al., 2007; Ginter 1995; Veronesi et al. 2003). Veronesi et al. (2003) showed that hormonal manipulation of estrus cycle and induction of ovulation provide an increasing of twin pregnancies from 6.5 to 16.6%. Comparisons among treatments showed that occurrence of twin pregnancy increases to 17.4% after treatment with cloprostenol, to 13.1% after treatment with hCG and to 30.6% after combined treatment using cloprostenol and hCG (Veronesi et al. 2003). In our observations, the frequency of MP was low compared to other studies. This may be partially explained by unknown factors, possibly the low genetic predisposition of the mares included in the study to MP, or because in most cases of MO, spontaneous reduction of the twin to a singleton occurred before the first pregnancy examination.

The frequency of double ovulations significantly increased after treatment with prostaglandin to 17% when compared to control (3%) (Ginther and Al-Mamun 2009). Cuervo-Arango and Newcombe (2010) showed that frequency of multiple ovulation can increase after treatment using cloprostenol in mares that ovulate later than 7 days after treatment, but this treatment have not influenced the increasing frequency of multiple pregnancies. Another study also showed that the frequency of MO increases after prostaglandin treatment, but not after hCG treatment, without impacting MP (Katila). It was also shown that the administration of prostaglandins does not increase the frequency of twin pregnancies (Lindeberg et al. 2020). Our results fully align with these observations. In another study induction of estrus with prostaglandins, and interval from treatment to ovulation had no significant impact on frequency of multiple ovulation (Cuervo-Arango et al., 2015). Also some studies do not confirm influence of hCG treatment on occurrence of multiple ovulation and multiple pregnancy (Morel and Newcombe 2008). In one study when estrus was induced by lupristiol or cloprostenol or estrus was spontaneous and subsequently hCG was used, double ovulations, and twin pregnancies occurred in 8.2 and 7,9; 14.9 and 8.1; 15.2 and 2.6% of cycles respectively, without significant differences among groups (Kuhl et al. 2017).

Summing up, hCG administration in a dose of 1500 IU during high endometrial edema can guarantee a response to this agent in more than 95% of cases in both spontaneous and induced estruses. Our results also indicate that the induction of ovulation using hCG does not influence the frequency of MO. However, treatment with prostaglandins followed by hCG significantly increases the frequency of MO, although this treatment may not affect the frequency of MP. Thus, prostaglandins may facilitate the development of more than one dominant follicle, while hCG does not appear to increase the development of additional follicles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.K.; investigation, data collection and analysis: W.R., N.K., K.M-P. and R.K.; data analysis: N.S; writing—original draft W.R. and R.K.; writing—review and editing, N.S. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed on these mares did not go beyond the routine veterinarian procedures performed on mares introduced to AI and management of early pregnancy.

Informed Consent Statement

All procedures performed on these mares were approved by the owners.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data generated during the study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial insemination |

| MO |

Multiple ovulations |

| MP |

Multiple pregnancies |

| |

|

References

- Allen, W.R.; Brown, L.; Wright, M.: Wilsher, S. Reproductive efficiency of Flat race and National Hunt Thoroughbred mares and stallions in England. Equine Vet. J. 2077, 39, 438-45. [CrossRef]

- Barbacini, S.; Zavaglia, G.; Gulden, P.; Marchi, V.; Necchi D. Retrospective study on the efficacy of hCG in an equine artificial insemination programme using frozen semen. Equine Vet. Educ. 2000, 12, 312-317.

- Coffman, E.A.; Pinto, C.R. A review on the use of prostaglandin F2α for controlling the estrous cycle in mares. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2016, 40, 34–40.

- Crowe, C.A.; Ravenhill, P.J.; Hepburn, R.J.; Shepherd C.H. A retrospective study of artificial insemination of 251 mares using chilled and fixed time frozen-thawed semen. Equine Vet. J. 2008, 40, 572-676.

- Cuervo-Arango J.; Newcombe J.R. Repeatability of preovulatory follicular diameter and uterine edema pattern in two consecutive cycles in the mare and how they are influenced by ovulation inductors. Theriogenology 2008, 69, 681-687. [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Arango J.; Newcombe J.R. Cloprostenol in equine reproductive practice: something more than a luteolytic drug. Reprod. Domest. Anim .2010, 4, 8-11.

- Cuervo-Arango, J.; Mateu-Sánchez, S.; Aguilar, J.J.; Nielsen J.M.; Etcharren, V.; Vettorazzi, M.L.; Newcombe J.R. The effect of the interval from PGF treatment to ovulation on embryo recovery and pregnancy rate in the mare. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 1272-1278. [CrossRef]

- Davies Morel, M.C.; Newcombe, J.R. The efficacy of different hCG dose rates and the effect of hCG treatment on ovarian activity: ovulation, multiple ovulation, pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, synchrony of multiple ovulation; in the mare. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2008, 09, 189-199.

- Dolezel1, R.; Ruzickova, K.; Maceckova, G. Growth of the dominant follicle and endometrial folding after administration of hCG in mares during oestrus. Vet. Med. 2012, 57, 36–41.

- Gastal, E.L.; Gastal, M.O.; Ginther, O.J. Relationships of changes in B-mode echotexture and colour-Doppler signals in the wall of the preovulatory follicle to changes in systemic oestradiol concentrations and the effects of human chorionic gonadotrophin in mares. Reproduction 2006, 131, 699-709.

- Ginther, O.J. Twins: origin and development. In: Ginther OJ (ed); Ultrasonic imaging and animal reproduction; Cross Plains, WI: Equiservices. 1995, pp. 249–306.

- Ginther, O.J.; Al-Mamun, M. Increased frequency of double ovulations after induction of luteolysis with exogenous prostaglandin F2α. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2009, 29, 581-583. [CrossRef]

- Grabowska, A.; Kozdrowski, R. Relationship between estrus endometrial edema and progesterone production in pregnant mares two weeks after ovulation. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 414. [CrossRef]

- Green, J.M.; Raz, T.; Epp, T.; Carley, S.; Card, C.E. Relationships between utero-ovarian parameters in the ovulatory response to human chorioni gonadotropin in mares. AAEP Proc. 2007, 53, 563–567.

- Kuhl, J.; Aurich, J.; Aurich, C. Effects of the prostaglandin F2α analogues cloprostenol and luprostiol in combination with hCG on synchronization of estrus and ovulation in mares. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2017, 57, 67-70. [CrossRef]

- McCue, P.M.; Hudson, J.J.; Bruemmer, J.E.; Squires, E.L. Efficacy of hCG at inducing ovulation: a new look at an old issue. AAEP Proc. 2004, 50, 510–513.

- Metcalf, E.S.; Thompson, M.M. The effect of PGF2α-induction of estrus on pregnancy rates in mares. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2010, 30, 196-199. [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.H.; Allen, W.R. Reproductive efficiency of intensively managed Thoroughbred mares in Newmarket. Equine Vet. J. 2020, 34, 51-60. [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, J.R.; Jöchle, W.; Cuervo-Arango, J. Effect of dose of cloprostenol on the interval to ovulation in the diestrous mare: a retrospective study. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2008, 28, 532-539. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.D.; Petersen, M.R.; Bojesen, A.M.; Pedersen, H.G.; Lehn-Jensen, H.; Christoffersen, M. Equine infectious endometritis – clinical and subclinical cases. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2015, 35, 95–104. [CrossRef]

- Samper, J.C. Ultrasonographic appearance and the pattern of uterine edema to time ovulation in mares. AAEP Proc. 1997, 43, 189-191.

- Samper, J.C. Induction of estrus and ovulation: why some mares respond and others do not. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 445-447. [CrossRef]

- Samper, J.C. A review of a practitioner’s perspective on endometrial edema. Pferdeheilkunde 2010, 26, 14–8. [CrossRef]

- Samper, J.C.; Jensen, S.; Sergeant, J.; Estrada, A. Timing of induction of ovulation in mares treated with ovuplant or chorulon. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2002, 22, 320-323. [CrossRef]

- Squires, E.L. Hormonal manipulation of the mare: a review. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2008, 28, 627-634. [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, M.C.; Battocchio, M.; Faustini, M.; Gandini, M.; Cairoli, F. Relationship between pharmacological induction of estrous and/or ovulation and twin pregnancy in the Thoroughbred mares. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2003, 25, 133-140. [CrossRef]

- Wojtysiak, K.; Ryszka, W.; Stefaniak, T.; Król, J.; Kozdrowski, R. Changes in the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines and acute-phase proteins in the uterus after artificial insemination in the mare. Animals 2020, 10, 2438. [CrossRef]

- Samper, J.C. Induction of estrus and ovulation: why some mares respond and others do not. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 445-447. [CrossRef]

- Katila, T. Effects of hormone treatments, season, age and type of mares on ovulation, twinning and pregnancy rates of mares inseminated with fresh and frozen semen. Pferdeheilkunde 2003, 19, 6, 619-624. [CrossRef]

- Lindeberg, H.; Koskinen, E.; Huhtinen, M.; Reilas, T.; Perttula, H.; Katila, T. Influence of PG administration and follicle status on the number of conceptuses. Theriogenology 2002, 58, 571-574.

- Sieme, H,; Schäfer, T.; Stout, T.A.; Klug, E.; Waberski, D. The effects of different insemination regimes on fertility in mares. Theriogenology 2003, 60, 1153-1164. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).