1. Introduction

Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were fundamental in revolutionizing the field of computer vision. Similarly, the pioneering induction of the Transformer [

1] architecture in Natural Language Processing [

2] has resulted in the AI revolution with Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT [

3], Bard [

4], Llama [

5,

6] among others have yielded impressive performances. The Transformer uses a simple similarity computation in the form of an inner product on the learnt positional encoded embeddings of a sequence of

n input words. If the matrix

Q and

K contain rows representing embedding of each word

, then

referred to as the “attention”, contains the dot product similarity of each input word with every other word in the input sequence. If there are

words being input, referred to as the context, then

, and

.

Like parallel feature maps in a CNN, each layer in the Transformer divides the attention calculation into parallel heads. The output from a Transformer layer has the same dimensionality as input and is obtained by a simple matrix computation of

where

V is similar to

K and contains rows of learnt position encoded embeddings of input words. For language models, where text generation is carried out based on a given context, the attention matrix is masked in a triangular fashion so that future tokens are not visible in the training process. Multiple layers of Transformer blocks are used before feeding the result of the last layer to a classification head. Because attention computation in each head is

, for long contexts, this becomes a computational bottleneck. Many approaches have been proposed in the past years to reduce the quadratic time complexity of attention to either linear or sub quadratic complexity. Some of the notable works include Transformer-XL [

7], Linformer [

8], Longformer [

9], Reformer [

10], Performer [

11], Perceiver-AR [

12], LaMemo [

13], ∞-former [

14] among others. We provide a brief background in the above-mentioned approaches used in reducing the attention complexity. Then we elaborate on the Transformer LS [

15] that we further enhance in this work.

Although Transformer LS performs efficient compression on the input sequence, but this compression results in segment fragmentation that leads to these key shortcomings.

It reduces the dimensionality of the input sequence resulting in a loss of context.

The input sequence is divided into smaller, potentially non-overlapping segments. Since information is isolated within segments, it disrupts the natural flow and continuity of information.

These two factors make it more challenging for the language model to capture overall context and relationships between distant elements in the sequence. Our architecture in CacheFormer alleviates some of the key constraints that can be summarized as:

We developed an innovative uncompressed attention mechanism where the highly attentive segments are dynamically cached in an uncompressed form.

Improved segment fragmentation of the projection mechanism followed in long attention. We achieved it by adding projections of segments that have an s/2 overlap where s is the segment size, with the existing segment-based projection mechanism as illustrated in

Figure 3.

We combine the existing short and long attention with our above two enhancements in an effective manner. This results in an architecture that can efficiently handle long attentions without causing much loss of attention information.

2. Background and Related Work

An important earlier work in handling long contexts was presented by Transformer-XL. The authors divided the context into segments and used segment level recurrence and a corresponding positional encoding to allow it to handle longer contexts. It achieved impressive results on the perplexity and BPC at that time. Linformer [

8] accomplished

O(n) complexity through linear self-attention. The authors demonstrate that the attention is typically low rank, and thus can be approximated by a low rank matrix. Here, from the original Q, K and V matrices

, K and V are projected to lower dimension matrices where K, V

where

k < n. Thus attention

. The output

, i.e., same as the original transformer. Since

k is fixed, the attention complexity is

O(n).

Although Linformer [

8] reduced the attention complexity significantly, especially if

, note that, it cannot be effectively used in autoregressive training and generation, as the projection of

compresses the information along the context, making the masking of attention for future tokens invalid. However, for classification problems where masking of attention is not needed, their architecture is effective in reducing complexity.

Another approach introduced by Longformer [

9] used sparse attention patterns instead of the full dense attention. The authors proposed sliding window attention, where tokens attended only to the nearby past, a dilated sliding window, and a mix of global and sliding window attention where some tokens attend to all tokens while others only attend to nearby tokens. For autoregressive modeling Longformer [

9] used dilated sliding window attention. Another notable work in reducing the attention complexity was performed by Reformer [

10]. The authors key idea was to use locality sensitive hashing which reduces the attention complexity to

. Note that because of the hashing process, the architecture is not suited for autoregressive modeling.

A different approach to reduce the attention complexity was taken by Performer [

11] where the attention is decomposed as a product of non-linear functions of original query and key matrices referred to as random features. This allows the attention to be encoded more efficiently via the transformer query and key matrices. Further efficient handling of long contexts accomplished by Perceiver AR [

12] divided the input sequence into smaller key/value and query components. These components underwent cross attention in the first layer with a latent

where

l is the size chosen in splitting the input sequence into the query part. The remaining layers operate on the

size instead of the usual

size as in a standard transformer. Although this cross attention on the partitioned input sequence results in efficient handling of long sequences, because of the reduced query size, the equivalent effect is more like a sliding window attention.

More recently, a different approach to handling long contexts was proposed via structure state space models. Structured State Space Sequence Model (SSMs) [

16] proposed an architecture that was based on a new parameterization that can be computed much more efficiently. A variation of the state space approach proposed by Mega [

17] uses single-head gated attention mechanism equipped with exponential moving average to incorporate inductive bias of position-aware local dependencies into the position-agnostic attention mechanism. They also present its variation with linear time complexity for handling long sequences. Further progression on the state space models yielded better results as demonstrated in Hungry hungry hippos [

18] and Mamba [

19] who achieved a very low perplexity score. Most recently xLSTM [

20] introduced exponential gating and parallelization in LSTMs to achieve extended memory. Some of the model sizes consisted of several billion parameters. We outperform the smaller version of these models with similar size as ours on the perplexity metric as shown in

Table 2.

An interesting concept in handling long sequences was presented by Transformer LS [

15]. Here a sliding window approach is used in handling near term attention, while a set of compressed segments for the entire past context is used as long-term attention. Both short and long attention are combined in the overall attention. The slight drawback of the approach is that the longer context is effectively used in compressed form and thus may lose some key contextual information in being able to generate the output in an autoregressive environment. We address this problem by further augmenting the long-short attention by using uncompressed highly attentive segments. Since long short attention divides the context into equal size segments before projecting each segment to a smaller size, there is potential for a loss in information due to segment fragmentation. We also improve this aspect by using overlapping segments and augment this to the existing long-short model. Thus, our enhanced long-short architecture involves four components in the overall attention, a sliding window attention, long attention based on compressed segments, long attention based on overlapping segments, and uncompressed segmented attention for few high attentive segments beyond the sliding window part. We describe the details of our design in the section 3. For completeness, we summarize the composition of a Transformer, followed by the ideas of long-short Transformer, that we build upon in our work.

3. Canonical Transformer

In normal multi-headed attention, if

are the query, key and value transformations of the input embeddings with sequence length of

n and embedding dimension of

d, then the scaled dot-product attention in the

-th Head

is given as:

where

is the dimension of each head. The output in each transformer layer is obtained by catenation of the output of all heads and transformed further via this projection matrix.

After feeding the embedding of a sequence of one hot encoded word,

x (with position encoding

PE added) through

p transformer layers, a classification layer is used at the output of the last layer to decide the output produced by the transformer. For autoregressive text generation, the classification layer’s final output is equal to the size of the dictionary of unique words in the corpus.

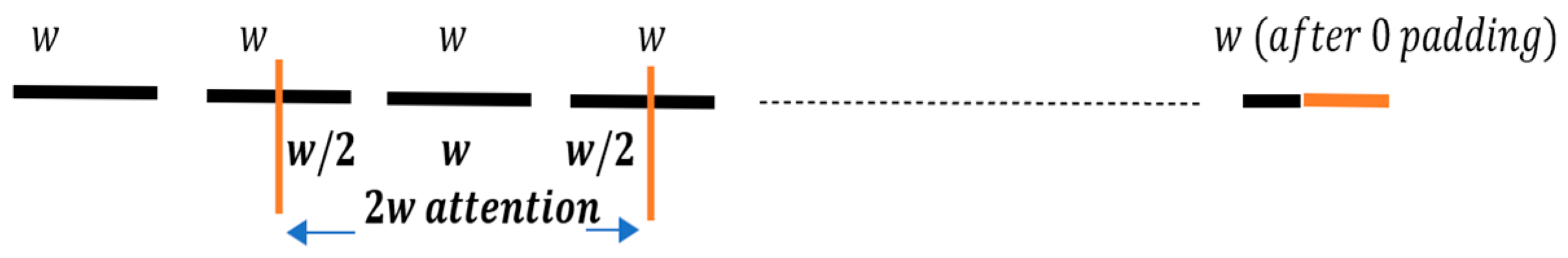

4. Long Short Transformer

Transformer-LS [

15] aggregated the local attention around a smaller window (sliding window), with a projection of the full sequence attention to a smaller size, so that we can efficiently handle long sequences without the quadratic attention complexity. For short attention, the approach here is to use a segment level sliding window attention, where the input sequence is divided into disjoint segments with length

w (e.g.,

w=128 and sequence length is 1024). For non-autoregressive applications, all tokens within a segment attend to all tokens within its home segment, as well as w/2 consecutive tokens on the left and right side of its home segment (zero-padding when necessary), resulting in an attention span over a total of 2

w key-value pairs. This is depicted in

Figure 1.

For each query

at the position

t within the

head, the 2

w key-value pairs within its window are:

. The short attention

is then given by the following equation:

Execution wise the segment-level sliding window attention (referred to as short attention) is more time efficient than the per-token sliding window attention where each token attends to itself and w tokens to its left and right, and its memory consumption scales linearly with sequence length. For auto-regressive applications, the future tokens in the current segment are masked, and only the previous segment is used.

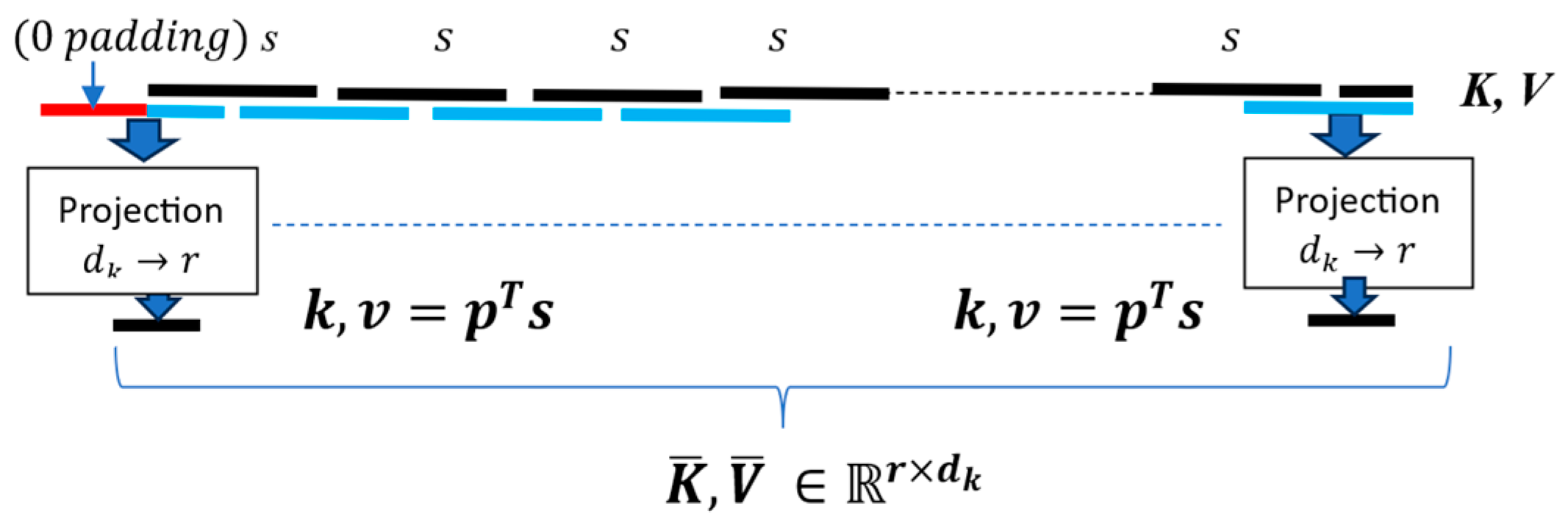

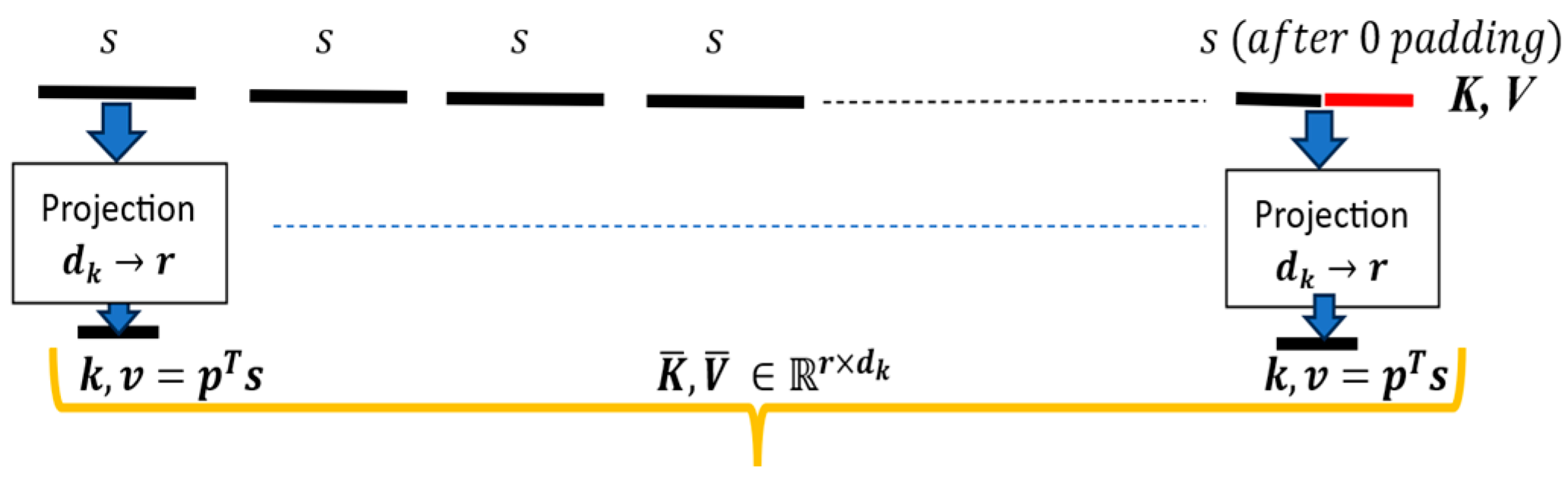

The compression is performed on the feature dimension initially through a projection weight matrix with dimensions, → ( ) where is the embedding dimensionality and is the target length. The projection matrix is computed by multiplying it with length Query () → () where ()

i.e.

. This product results to

with dimensions

. The transpose of this projection matrix

is applied to the Query vector →

. This product results to a modified Query

, with dimensionality →

thereby compressing its sequence length. This is a standard dimensionality reduction technique illustrated in

Figure 2 and is used in popular models like Performer and Transformer LS.

For long attention, the key and value transformations for the input sequence are first divided into segments of fixed size

s, and then projected to a smaller dimension

r, where the projection

. Mathematically, the long attention

(in each head

) as followed by the long-short Transformer can be described as:

The output of in the

head is:

Note that the long attention is effectively done on a compressed form of K and V, as the projection causes the input sequence of size n to be compressed to size r. This results in full attention to now be replaced with the implicit product of two low-rank matrices and , and thus the computational complexity is of long attention is reduced from to .

Long-Short Transformer [

15] integrates the short and long attentions into a single attention. While the short attention can attend to most recent input, the long attention is in compressed form. Further, the long attention is based on segmentation of the input sequence that may suffer from segment fragmentation as the information in each segment is compressed via the projection mechanism.

5. Enhanced Long Short Transformer

The long-term attention in the existing Long-Short Transformer is done at a compressed level (projection to r causes an effective compression of the input context). Therefore, one of our enhancements is to augment the long attention with an attention that is based on a subset of highly attentive uncompressed segments.

5.1. Enhanced Long Attention with Segment Caching

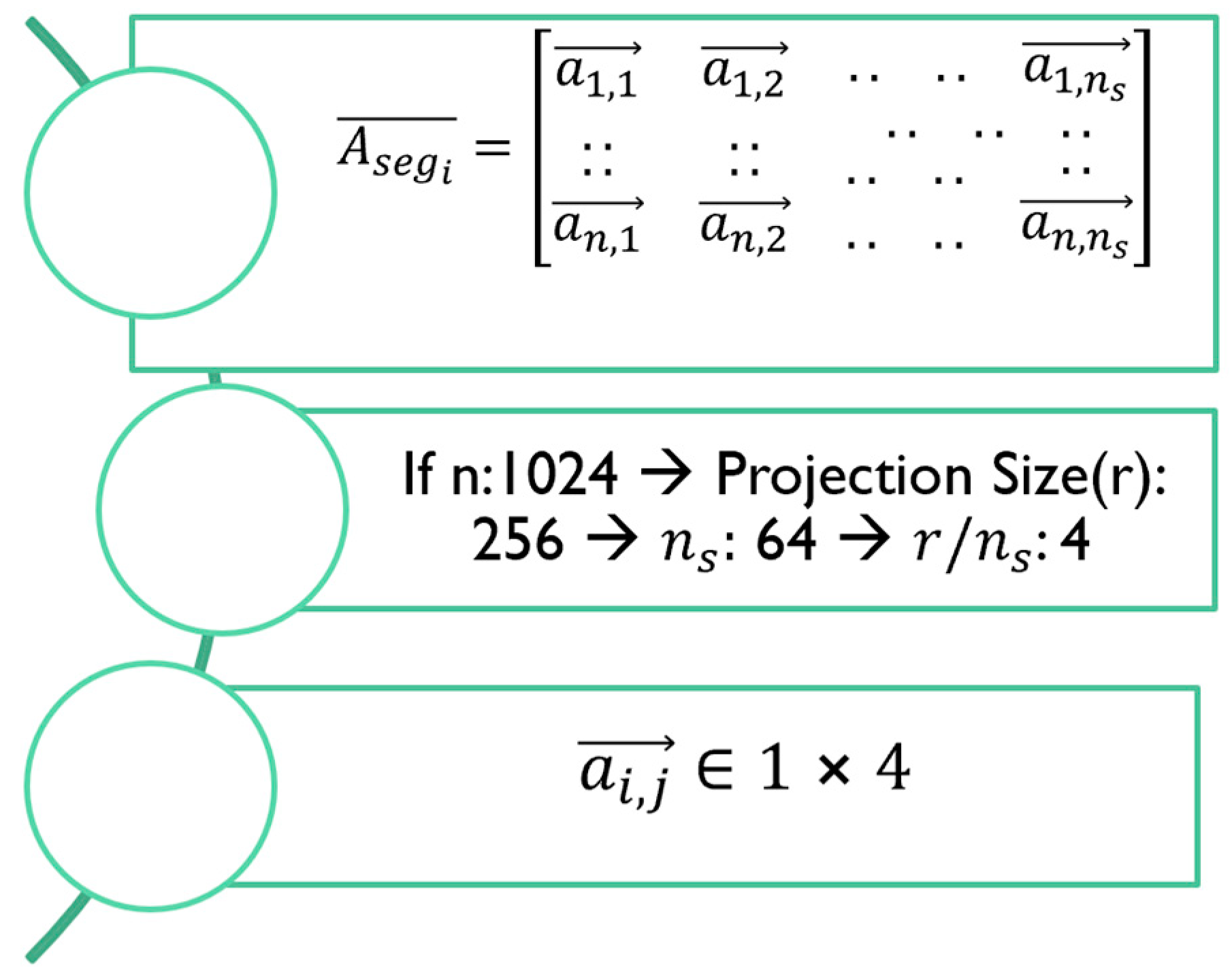

The subset of segments that are selected for attention at the uncompressed level is completely dynamic and obtained by the vector magnitude of the compressed segment-wise attention. In simple words, we examine the segment-wise long attention

as given by Equation 6. Since

, and if there are

segments, then each row in

contains a set of row vectors of size

, as denoted by segmented attention

in Equation 8. Magnitude of each vector

in Equation 8, indicates the attention of word

to the

segment in the long attention. This phenomenon is also explained in the

Appendix A.1.

For execution efficiency, we average the segment attention vectors in

p consecutive rows resulting in a segment attention matrix

where

m = n/p. Then we choose top

k segments by magnitude of each vector in each row of the segment attention matrix

. Note that each entry in the segment attention matrix,

, indicates the segment number that has high attention to the sequence of

p words positioned from

to (

)] in the input context as shown in Equation 9. Rather than using these attentive segments in compressed form, we extract them from the segmented

K and

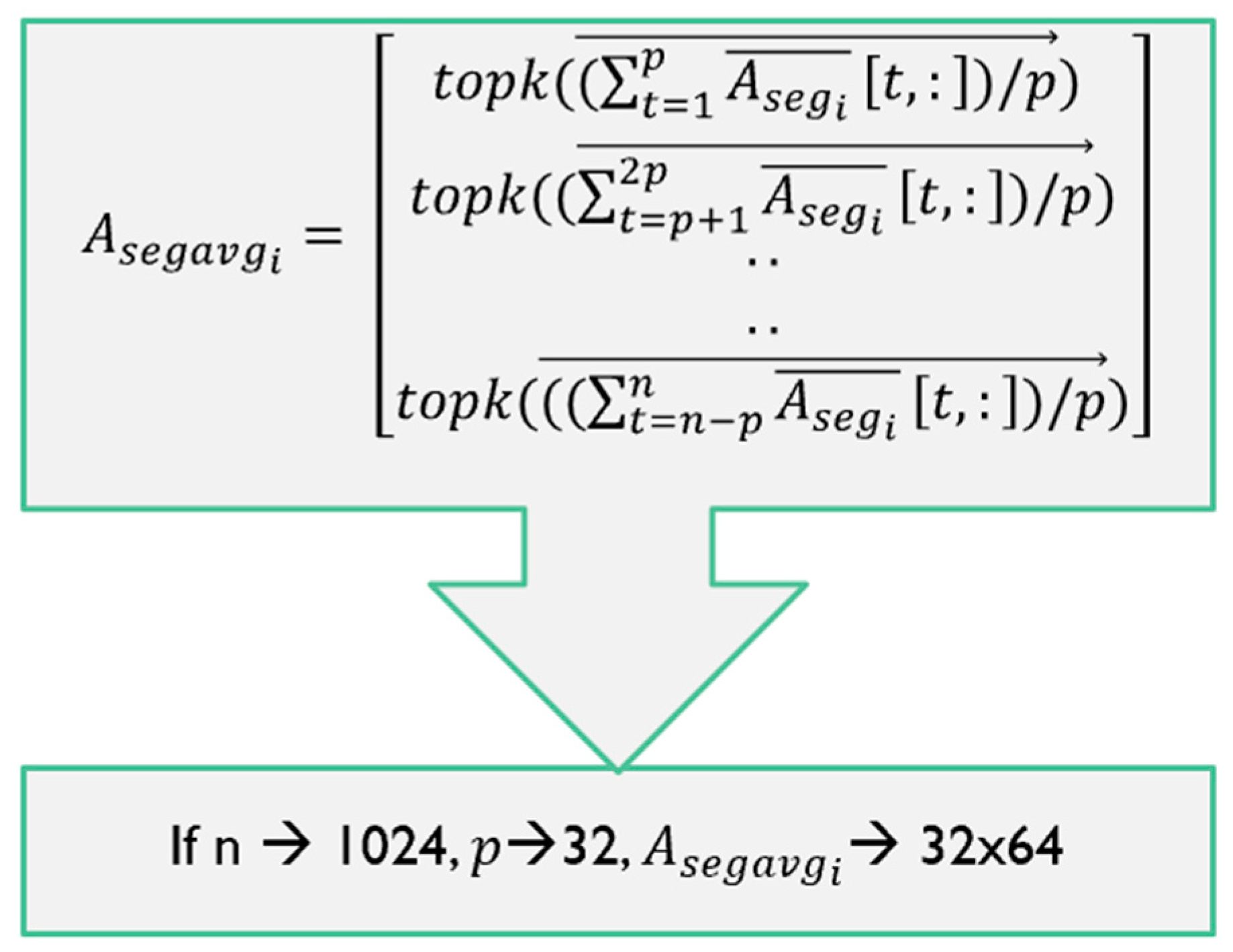

V matrices before doing any compression on these. The example in the

Appendix A.2 can be accessed for further explanation.

Similar to how in cache memory design (in computer architecture), in case of a cache miss, we not only retrieve the needed data from the RAM, but also bring a few consecutive following words, as there is high probability that these may be needed in the near future. In case of segments that we determine most attentive (by the top k order), we also retrieve u consecutive segments.

To clarify our approach, if the sequence length is

n = 1024, and long attention segment size = 16, then there will be 64 segments in the uncompressed

K and

V matrices. If the projection size

r = 256 (ratio of 1024/256=4), then each segment of size 16 will be compressed to size of 4, resulting in long attention matrix

of size 1024x(64x4) i.e., 1024x256. If we choose to average

p=32 consecutive rows in

, and take the magnitude of each of the 1x4 vectors in each row (corresponding to the 64 segments), then the segment attention matrix

will be 32x64. Taking the index of top

k entries in each row of

will give us the index of most attentive

k segments to the corresponding set of 32 words in the input sequence. Assembling these top

k attentive segments, and one segment before and one segment after the attentive segment (if

u=3), will result in 15 segments per row. If

k=5 is chosen in

top-k and

u=3 which indicates using of

u-1 many nearby segments for each attentive segment. Thus, the cache

K, V matrices

(e.g., 32x(15x16) = 32x240 in this case) contain the most attentive 15 segments in uncompressed form. Note that we stack the

‘

p’ times to match the dimensionality with

Q. From the most attentive

ku segments in

, we can obtain the cache attention

as:

Further pictorial representation is available in the

Appendix A.3

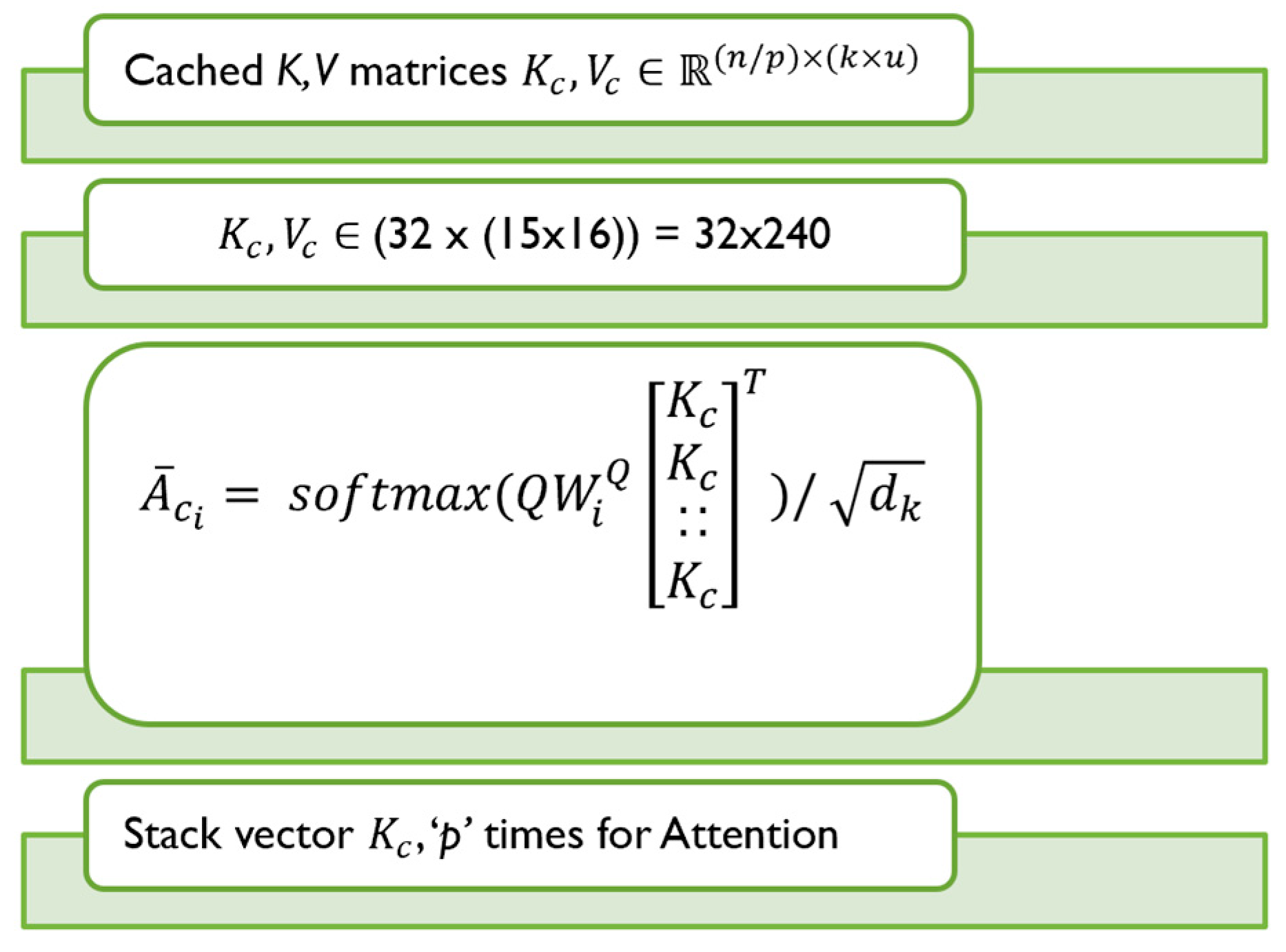

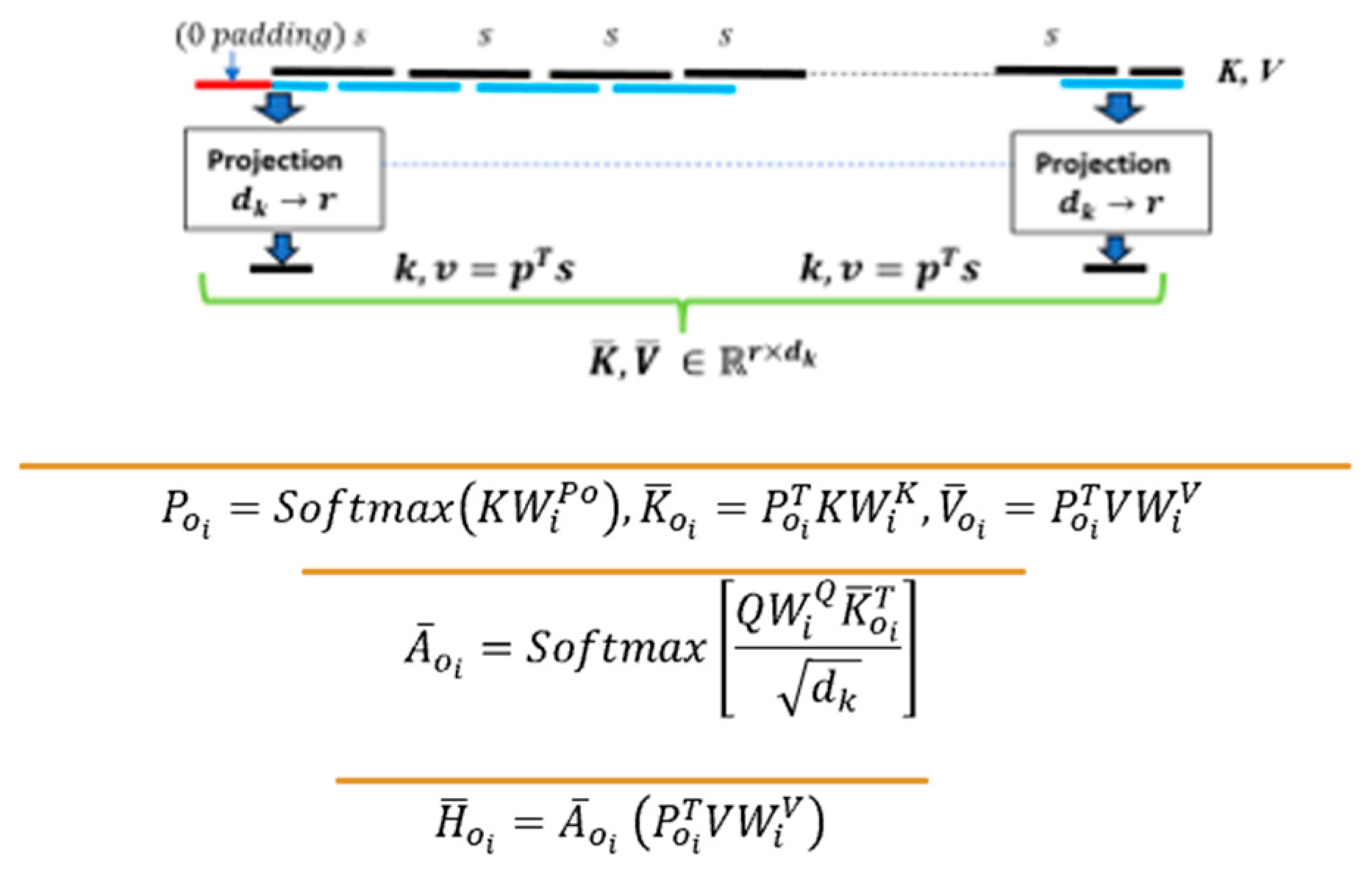

5.2. Enhanced Long Attention with Overlapping Segments

In addition to the original long attention in the Long-Short Transformer that uses the projections on each segment, we augment the existing long attention by using overlapping segments (with 50% overlap in augmented long attention) as shown in

Figure 3. The motivation behind the overlap is to provide context continuity and reduce the effect of segment fragmentation that occurs in long attention. Zero padding in the beginning segment is added to ensure the same dimensionality for the overlapped long segment attention. The overlapped long segment attention

similar to Equation 5 is given below and is further explained in the

Appendix A.4

Figure 3.

Overlapping Segmented Long Attention with Compressed Segments.

Figure 3.

Overlapping Segmented Long Attention with Compressed Segments.

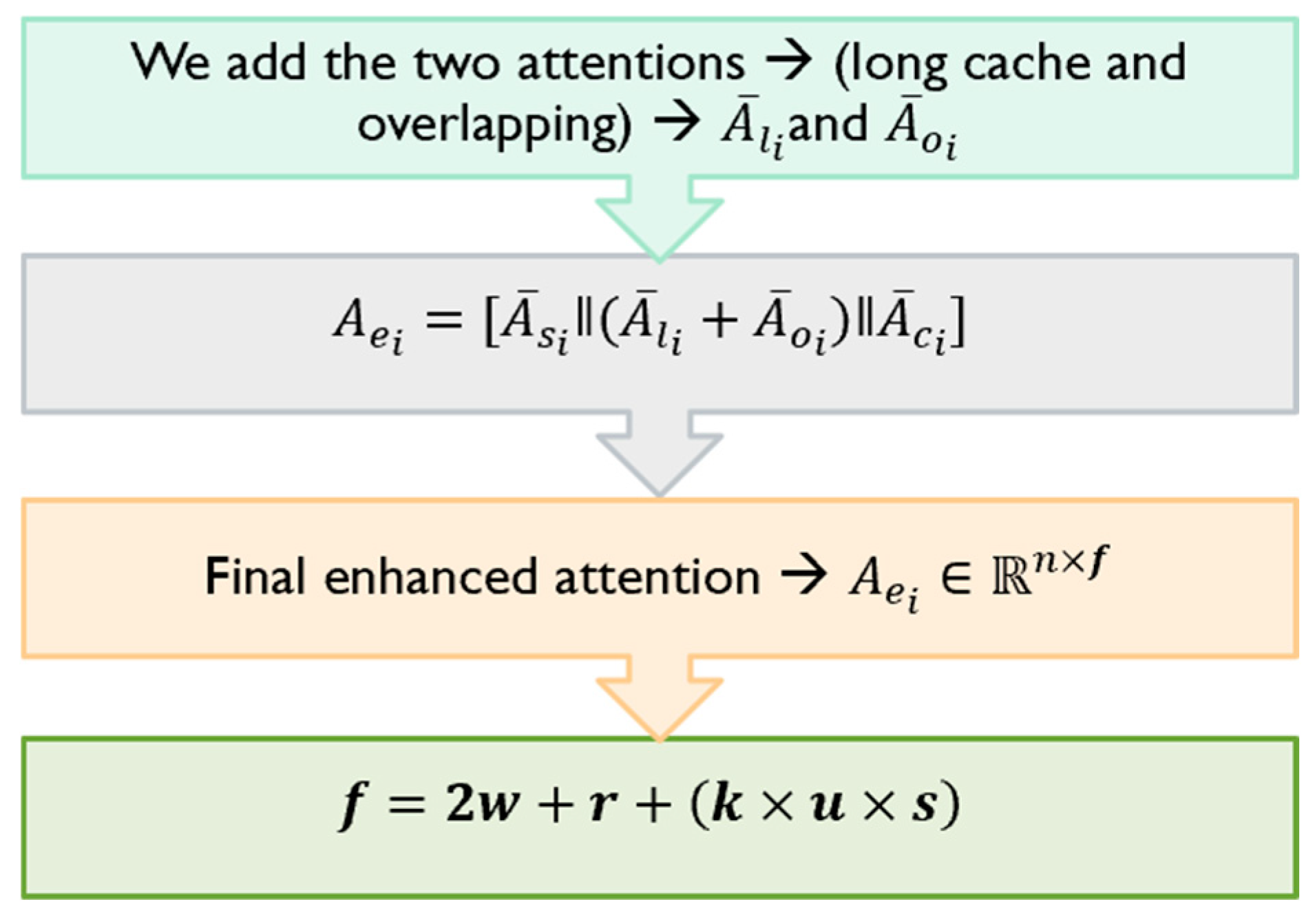

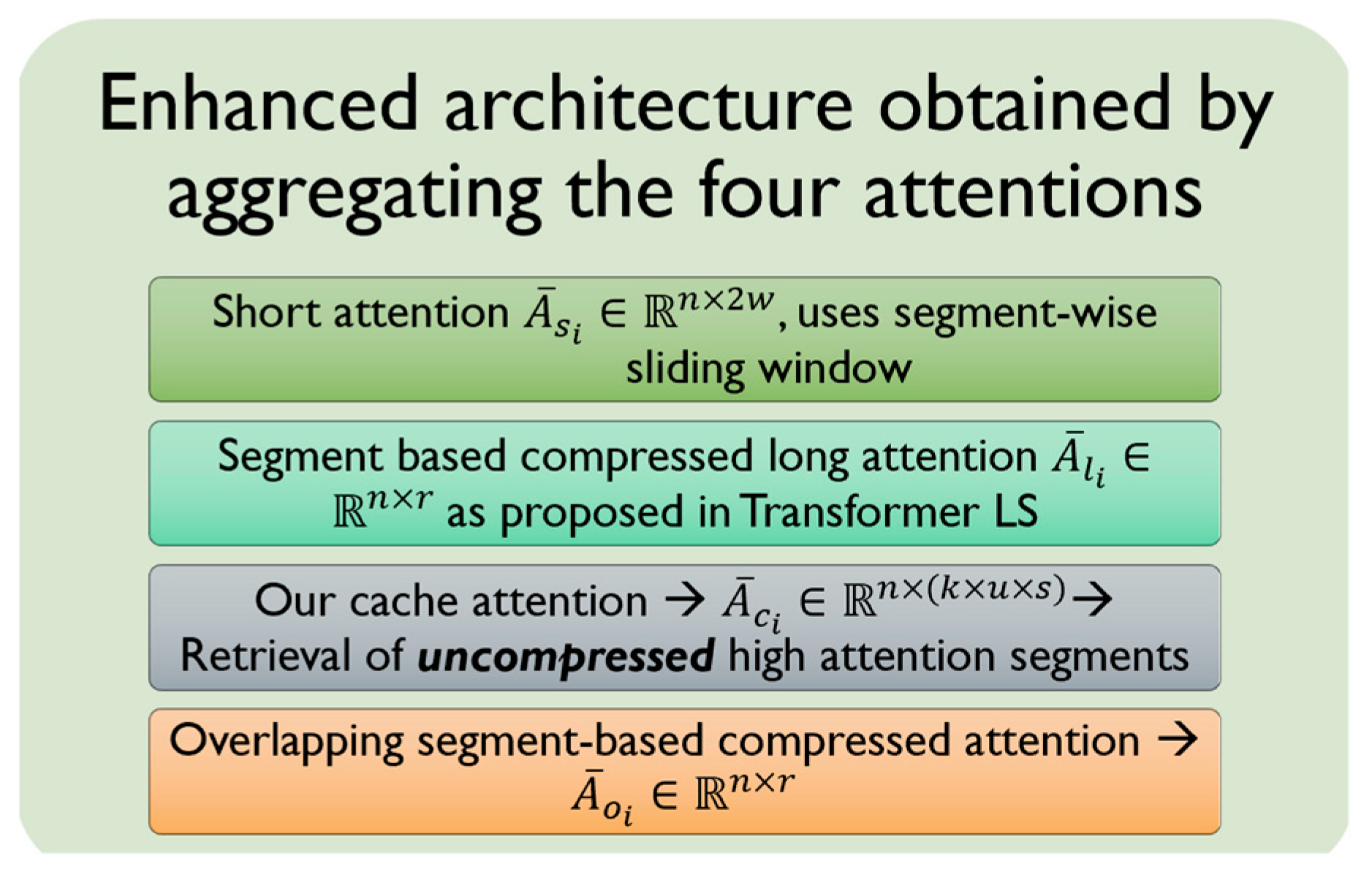

5.3. Aggregated Long-Short Attention

The final attention in our enhanced architecture is obtained by aggregating the four attentions as discussed earlier:

- 1)

The short attention, that uses segment-wise sliding window in Transformer LS

- 2)

The segment based compressed long attention, as proposed in Transformer LS

- 3)

Our cache attention based on dynamic retrieving of uncompressed high attention segments,

- 4)

Our overlapping segment-based compressed attention, .

We add the two similar sized long and overlapping attentions,

and

, and

indicates the catenation of different sized attentions,

and

. Thus, the final enhanced attention

where

is expressed as:

w is the window size in short i.e., sliding window attention.

r is the compressed projection target size in the long attention.

factor is for retrieving top k attentive segments.

u-1 is the number of neighboring segments to retrieve for cache attention

is the segment size in long attention.

For example, in = 5; u = 3; segment size in short attention, w = 128; segment size in long attention, s = 16; compression target length, r = 256. Hence, for an input sequence length of 2048, the size of our combined attention matrix is 2048x752. The time complexity of the different components in our Enhanced Long-Short attention is as follows:

For the short attention → , where is the sliding window size.

For both long and overlapping long attentions i.e., , → , where is the compressed output size from each of the long segments

For cached attention , → , where is the number of the top attentive segments, and is the long attention segment size.

Since the dominant term in the above four components is the long attention, the overall time complexity of our enhanced attention is

. Effectively, this is very close to the sliding window attention. To further elaborate on our attention computation in Equation 14, note that the dimensionality of short sliding attention

in the LS Transformer is

and its compressed long attention’s,

dimensionality is

. During our caching mechanism, we augment attentions

and

with dimensionalities

and

respectively to the Long Short attention. Since

and

deal with sequence lengths compressed to similar dimensions, they have similar shapes. Therefore, we can sum up the two attention matrices along the similar dimensions to conserve size and overall attention complexity. Whereas our caching attention

and

have different shapes, hence they cannot be summed up and concatenation is the only choice. One can refer to the

Appendix A.5 for pictorial representation

6. Results

We use the long-short transformer as the baseline architecture. Instead of focusing on the absolute best results for perplexity and BPC, which often are achieved through extremely refined training schedules and large model sizes, we focus on the improvements over the baseline. Therefore, the results we show are more accurate reflection of the architectural improvements of our design. The baseline architecture is also programmed by us, and the enhancements we propose are programmed in the same implementation and can be selectively turned on or off to see the contribution of each enhancement. We also use similar training schedules for the different architectures being compared.

Table 1 shows the perplexity results for wikitext-103 dataset. It uses sequence length of 1024, short attention segment size of 128, long attention segment size of 16, compression of the long sequence by a factor of 4, i.e.,

r=256, and different values of

k in top k cache attention, and neighboring segments retrieval u of 1 or 3 (which indicates the segment before the attentive segment, and the one after it is also retrieved.

Note that our enhanced architecture does not cause any increase in the number of model parameters over the baseline long short Transformer. The models used for results in

Table 1 have 12 layers, 12 heads, and an embedding size of 768 (for all architectural variations). For a sequence length of 1024 (which is same as used in GPT-2), using 7 segments (

k=7,

u=1) yielded considerable improvement in perplexity. Increasing k beyond 7 did not seem to considerably reduce perplexity further. Since we have two major enhancements of cache attention and overlapping segment-based attention over the baseline,

Table 2 shows an ablation study of the effects of each architectural improvement.

Table 2.

Ablation Study of Architectural Enhancements.

Table 2.

Ablation Study of Architectural Enhancements.

| Architecture |

Model Size (Millions) |

Perplexity |

| Long-Short (Baseline-Ours) |

122.52 |

23.74 |

| Transformer-XL (Standard) |

151 |

24 |

| ∞-former |

160 |

24.22 |

| LaMemo |

151 |

23.77 |

| H3 (Hungry Hungry Hippos) |

125 |

23.7 |

| Llama |

125 |

23.16 |

| Mamba |

125 |

22.49 |

| xLSTM [7:1] |

125 |

21.47 |

| Enhanced Long Short with overlapping segments only |

122.52 |

23.47 |

| Enhanced Long Short with cache attention only (k=7, u=1)

|

122.52 |

21.67 |

| Enhanced Long Short with overlapping segments and cache attention (k=7, u=1)

|

122.52 |

21.32 |

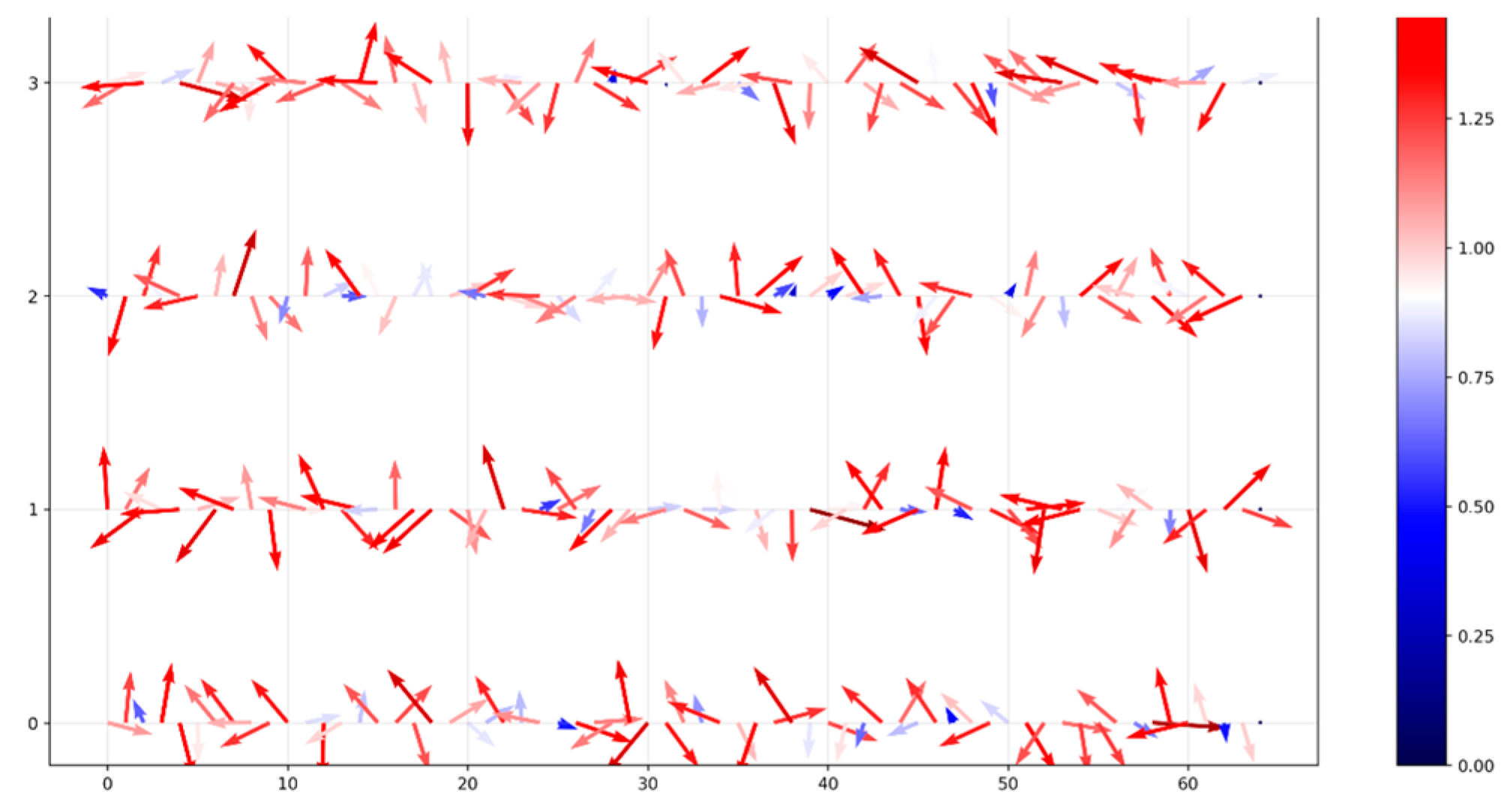

Figure 4 depicts the 64 attention vectors for each segment (from compressed long attention, after averaging

p=256 rows) corresponding to the 64 segments during the beginning of training. The highest top

k magnitude vectors then determine the segment to use in uncompressed form for our cache attention.

Table 3 shows the BPC results on the enwik-8 benchmark. The 23 million model uses 8 layers, 8 heads and embedding size of 512. The 34.88 million models used 12 layers. It is interesting to note that the relative improvement in BPC by our enhanced architecture is less pronounced as compared to the perplexity improvements. This could be attributed to the fact that majority of improvements are attributed to cache attention which uses a few highly attentive uncompressed segments in long attention. While this benefits the perplexity which is a measure of the model’s prediction capability, but BPC not as much, as BPC is more of a compression efficiency measure of the model.

7. Discussion

Since the uncompressed segments to be used in our cache attention design are dynamically decided based on the input sequence, the execution time increases as more segments (i.e., higher k) are used. When we use, sequence length of 1024, compression r = 256, k = 7, u = 1, short attention segment size of 128, then the size of aggregated attention (short, long, cache, overlapping) is 1024x624. Since our cache attention mechanism as explained in section 3.1 is completely dynamic, and uses the most attentive segments in uncompressed form, we average the attention vectors over p rows (to improve efficiency of execution) as given by Equation 9.

If we use a sequence length of 1024, and average over 256 rows, then the segments determined by our cache attention mechanism part way through the training of the model appears as shown in

Table 4. Note that to implement the autoregressive behavior, the input sequence cannot attend to a future segment. Our implementation guarantees that the input sequence can only attend to a previous segment. For example, when attending to words 768-1023 in the input sequence, the maximum segment that the cache attention can use is 47 (if the long segment size is 16, then there are 64 segments in the 1024 size sequence).

Lost in the middle [

21] is one of the important recent papers in handling long contexts has indicated that current language models do not robustly make use of information in long input contexts. They studied different models and concluded that “performance is often highest when relevant information occurs at the beginning or at the end of the input context, and significantly degrades when models must access relevant information in the middle of long contexts.”

Note that our cache attention model addresses this aspect nicely in the sense it uses attentive segments dynamically regardless they are needed in the beginning or the middle of input context. For example, the last row in

Table 4 indicates the highest attentive segments that are used. Segments 32, 35, 37 are relatively in the middle of the input context. When we determine the most attentive segment to use in our cache attention, if the neighboring segment parameter count

u>1, then as we look at the segment index of the next or previous index, a duplicate may occur as the next segment may already be one of the high attentive segments. Similarly, if the high attentive segments belong to a future segment, we replace them by one of the allowed segments. Since information segmentation should not occur, the segment we select to be added is the one that is contiguous to an existing high attention segment.

8. Conclusions

Handling long contexts in an efficient manner without loss of performance is an important area of research in language models. Although many approaches have been recently proposed to address this problem, we present a new innovative solution that is motivated by the cache and virtual memory concepts in computer architecture. In such designs, if there is a cache or page miss, the needed data is retrieved from the disk or RAM. We handle long contexts by diving them into small segments. By the magnitude of the compressed attention vectors, we determine the most attentive segments, and then use these in uncompressed form.

Similar to the cache memory design, we also use consecutive segments near to the high attention segments to improve the language model predictive performance. Our results on the perplexity indicate significant improvement over the baseline architecture that uses short and long compressed attention.

For the BPC, the cache attention mechanism does not show remarkable improvement on the baseline. We conjecture that the BPC that favors compression capability is not benefited by the relevant segment usage that our model provides which is helpful in model prediction capability. Another advantage of our approach is that the use of high attention segments is dynamic and depends on the input sequence. Thus, if the model needs to use information in the middle or anywhere in the input context, it is provided in uncompressed form via the high attention determination on the compressed segments.

9. Limitations

The only shortcoming of our approach we feel is that the dynamic segment attention is relatively slow during training. We partially overcome this by initially pretraining the model without dynamic attention, and then fine tune it on our dynamic cached attention. Our future work involves in applying the cache attention to reduce the model complexity of large language models. Further we are in the process to create a hierarchical cache design such that very long contexts can be efficiently handled.

Further, our model sizes and datasets were constrained by computational resources available to us. We used GPU RTX 4090 and therefore could not use larger datasets such as PG-19 and run larger models with larger embedding size, layers, and heads.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and A.M.; methodology, S.S.; software, S.S.; validation, S.S. and A.M.; formal analysis, S.S. and A.M.; investigation, S.S. and A.M.; resources, S.S.; data curation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and A.M.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Further Details on our Enhanced Caching Transformer

In our caching protocol we compress and dynamically retrieve the most relevant compressed segments for any given input. Based on the design constraints an appropriate amount of input sequence compression is performed. Thereafter the sequence is split into the desired segments, and we choose the most similar segments for each query and retrieve them in the original uncompressed form. It ensures only the most relevant information is being picked. This not only helps in reducing the context size, but it also enables in preserving key information. This enhanced caching attention technique is explained in greater detail in the subsequent sections.

Appendix A.1. Enhanced Caching Attention

Figure A1.

Downsized Compression of Attention Matrix along

Figure A1.

Downsized Compression of Attention Matrix along

Consider the length of the input sequence to be 1024 tokens that need to be compressed and down projected to 256 tokens. Here we choose to divide the row into 64 segments. This will yield to a compression ratio of 4. The attention matrix will be of size . Therefore for segments, each row in will consist of row vectors with size .

Further, the magnitude of the vector will represent the attention of the word token to the compressed segment in the long attention as shown in Figure 5. Thereafter, we compute the root mean square for each of the sized attention vectors , hence the dimension across each row is downsized from 256 to 64. We use this size for the subsequent attention processing steps as demonstrated in the following section

Appendix A.2. Averaging in Segment Caching

Attention computation and top-k segment retrieval across all 1024 rows turned out to be computationally cumbersome and time intensive. Therefore, to achieve execution efficiency, we averaged all 1024 input vectors across consecutive rows for the previous attention matrix where is a hyperparameter.

Figure A2.

Averaged Compression of Attention Matrix along the Input Length.

Figure A2.

Averaged Compression of Attention Matrix along the Input Length.

This segment attention matrix is further reshaped and compressed into

, where

m = n/p=32 as shown in

Figure A2. This implementation was key for our model to achieve superior results outperforming other popular language models of similar size as mentioned in

Table 2 and resulted in a faster run time as well.

Appendix A.3. Top-k Retrieval in Segment Caching

Post the compression and averaging, the top

most similar segments were chosen to be retrieved by the order of the attention magnitude betweeen the modified input and key/value matrices. These segments were picked corresponding to each row

, which is an averaged input sequence of 32 consecutive words (averaged down from 1024) from the segment attention matrix

. The hyperparameter

is chosen based on the performance needs and based on that value along with the

segment, we also extract one segment before and after the

attentive segment. Therefore, we define

as the hyperparameter that regulates the number of adjacent segments around

that need to be retrieved from the sequence. For instance, with

and

will result in a total of 15 uncompressed extracted segments of length 16 from each row as shown in

Figure A3.

Figure A3.

Enhanced Attention Matrix after top-k retrieval.

Figure A3.

Enhanced Attention Matrix after top-k retrieval.

Appendix A.4. Overlapping Segments in Long Attention

Figure A4.

Long Attention with Overlapping Segments.

Figure A4.

Long Attention with Overlapping Segments.

As discussed earlier that the segmentation of input into chunks leads to fragmentation of long-term information. This becomes a challenge in building long term dependency. This issue hasn’t been addressed in prior Transformer based language models. Therefore, we augment the long attention with segments with a 50% overlap to maintain the continuity of data as shown in

Figure A4. The model is trained with the overlapping data as the query that needs to learn the original chunks as key and values.

Appendix A.5. Aggregated Enhanced Long Short Attention

Thereafter we add the overlapping attention

to the long cache attention

who have similar shapes. The sliding window (short) attention

and our caching attention

are concatinated to the above summed attention as pictorially demonstrated in

Figure A5.

Here indicates the catenation of different attentions, w is the window size in short i.e., sliding window attention, r is the projection size in compressing the long attention, k is the factor in retrieving high attention top k segments, is the segment size in long attention, determines the number of segments to be retrieved adjacent to the top one.

Figure A5.

Complexity of the Enhanced Attention.

Figure A5.

Complexity of the Enhanced Attention.

Finally, the figure below illustrates the four attention mechanisms that are simultaneously aggregated and successfully inducted in our model architecture.

Figure A6.

Aggregated Enhanced Attention.

Figure A6.

Aggregated Enhanced Attention.

References

- Vaswani, Ashish, Noam M. Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser and Illia Polosukhin. “Attention is All you Need.” NIPS, (2017).

- Singh, Sushant, and Ausif Mahmood. "The NLP cookbook: modern recipes for transformer based deep learning architectures." IEEE Access 9, (2021), 68675-68702.

- Achiam, Josh, Steven Adler, Sandhini Agarwal, Lama Ahmad, Ilge Akkaya, Florencia Leoni Aleman, Diogo Almeida et al. "Gpt-4 technical report." arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, (2023).

- Team, Gemini, Rohan Anil, Sebastian Borgeaud, Jean-Baptiste Alayrac, Jiahui Yu, Radu Soricut, Johan Schalkwyk et al. "Gemini: a family of highly capable multimodal models." arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.11805, (2023).

- Touvron, Hugo, Thibaut Lavril, Gautier Izacard, Xavier Martinet, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Timothée Lacroix, Baptiste Rozière et al. "Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models." arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971, (2023).

- Touvron, Hugo, Louis Martin, Kevin Stone, Peter Albert, Amjad Almahairi, Yasmine Babaei, Nikolay Bashlykov et al. "Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models." arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288, (2023).

- Dai, Zihang, Zhilin Yang, Yiming Yang, Jaime G. Carbonell, Quoc V. Le and Ruslan Salakhutdinov. “Transformer-XL: Attentive Language Models beyond a Fixed-Length Context.”, ACL, (2019).

- Wang, Sinong, Belinda Z. Li, Madian Khabsa, Han Fang and Hao Ma. “Linformer: Self-Attention with Linear Complexity.” ArXiv abs/2006.04768, (2020): n. pag.

- Beltagy, Iz, Matthew E. Peters, and Arman Cohan. "Longformer: The long-document transformer." arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.05150, (2020).

- Kitaev, Nikita, Lukasz Kaiser and Anselm Levskaya. “Reformer: The Efficient Transformer.” ArXiv abs/2001.04451, (2020): n. pag.

- Choromanski, Krzysztof, Valerii Likhosherstov, David Dohan, Xingyou Song, Andreea Gane, Tamas Sarlos, Peter Hawkins et al. "Rethinking attention with performers." arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.14794, (2020).

- Hawthorne, Curtis, Andrew Jaegle, Cătălina Cangea, Sebastian Borgeaud, Charlie Nash, Mateusz Malinowski, Sander Dieleman et al. "General-purpose, long-context autoregressive modeling with Perceiver AR." ICML, (2022), pp. 8535-8558. PMLR.

- Ji, Haozhe, Rongsheng Zhang, Zhenyu Yang, Zhipeng Hu, and Minlie Huang. "LaMemo: Language modeling with look-ahead memory." arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.07341, (2022).

- Pedro Henrique Martins, Zita Marinho, and Andre Martins. “∞-former: Infinite Memory Transformer”. ACL, (2022) (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 5468–5485.

- Zhu, Chen, Wei Ping, Chaowei Xiao, Mohammad Shoeybi, Tom Goldstein, Anima Anandkumar, and Bryan Catanzaro. "Long-short transformer: Efficient transformers for language and vision.", NIPS, (2021): 17723-17736.

- Gu, Albert, Karan Goel, and Christopher Ré. "Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces." arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.00396, (2021).

- Ma, Xuezhe, Chunting Zhou, Xiang Kong, Junxian He, Liangke Gui, Graham Neubig, Jonathan May, and Luke Zettlemoyer. "Mega: moving average equipped gated attention.", arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.10655, (2022).

- Fu, Daniel Y., Tri Dao, Khaled K. Saab, Armin W. Thomas, Atri Rudra, and Christopher Ré. "Hungry hungry hippos: Towards language modeling with state space models.", arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.14052, (2022).

- Gu, Albert, and Tri Dao. "Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces.", arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.00752, (2023).

- Beck, Maximilian, Korbinian Pöppel, Markus Spanring, Andreas Auer, Oleksandra Prudnikova, Michael Kopp, Günter Klambauer, Johannes Brandstetter, and Sepp Hochreiter. "xLSTM: Extended Long Short-Term Memory.", arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.04517, (2024).

- Liu, Nelson F., Kevin Lin, John Hewitt, Ashwin Paranjape, Michele Bevilacqua, Fabio Petroni, and Percy Liang. "Lost in the middle: How language models use long contexts." ACL, (2024): 157-173.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).