Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The rapid advancements in large language models (LLMs) have propelled natural language processing but pose significant challenges related to extensive data requirements, high computational demands and more training times. While current approaches have demonstrated powerful capabilities, they often fall short of achieving an optimal balance between model size reduction and performance preservation, limiting their practicality in resource-constrained settings. We propose Synergized Efficiency and Compression (SEC) for Large Language Models, a novel framework that integrates data utilization and model compression techniques to enhance the efficiency and scalability of LLMs without compromising performance. Inside our framework, Synergy Controller could balance data optimization and model compression automatically during the training. The SEC could reduce data requirements by 30%, compress model size by 67.6%, and improve inference speed by 50%, with minimal performance degradation. Our results demonstrate that SEC enables high-performing LLM deployment with reduced resource demands, offering a path forward toward more sustainable and energy-efficient AI models in diverse applications.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

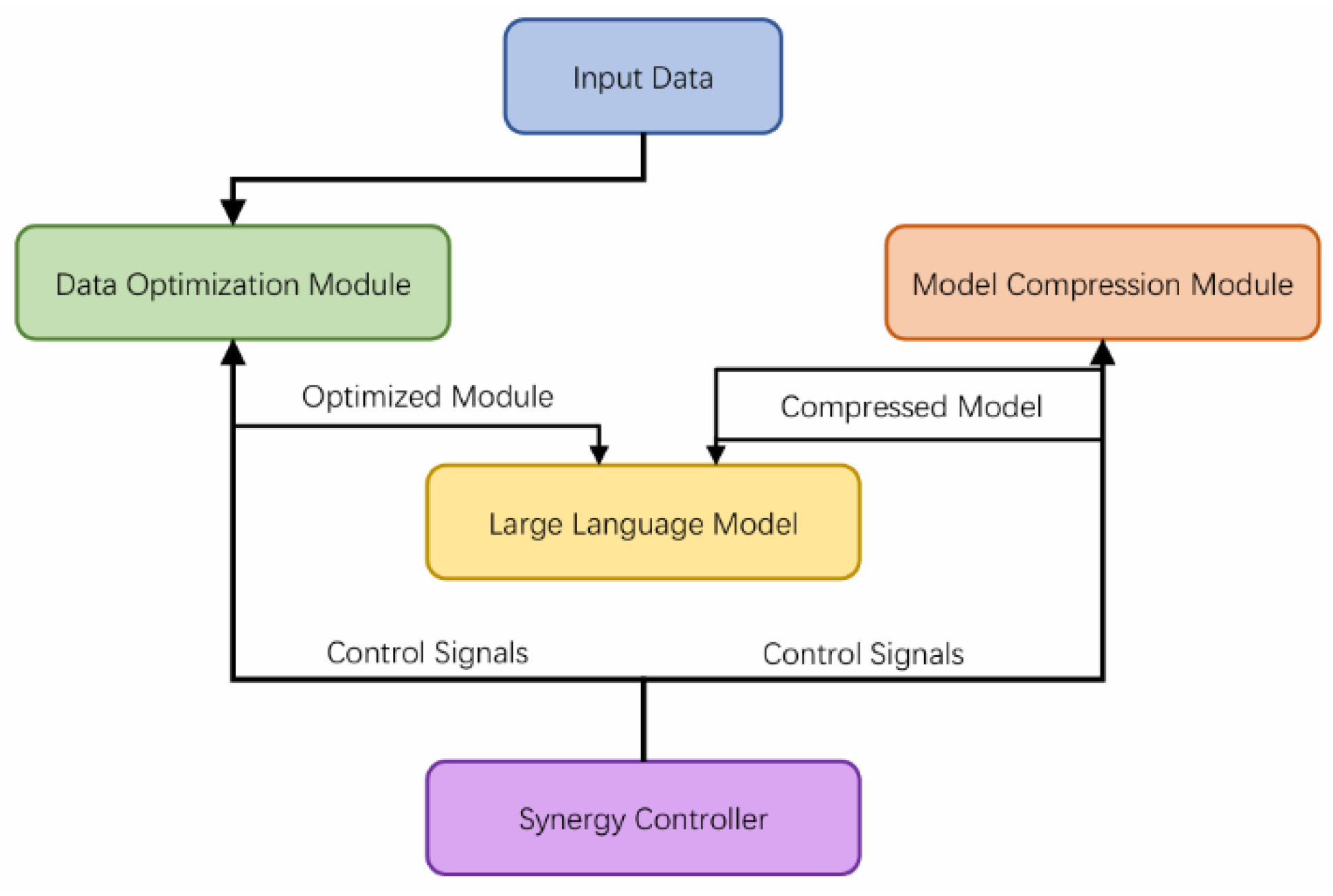

3. Synergized Efficiency and Compression Method

3.1. SEC Architecture and Components

3.2. Data Optimization Techniques

3.3. Model Compression Strategies

3.4. Synergy Controller

4. Experiments and Results Analysis

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Dataset Parameters

4.1.2. Model Parameters

4.1.3. Experiment Environment

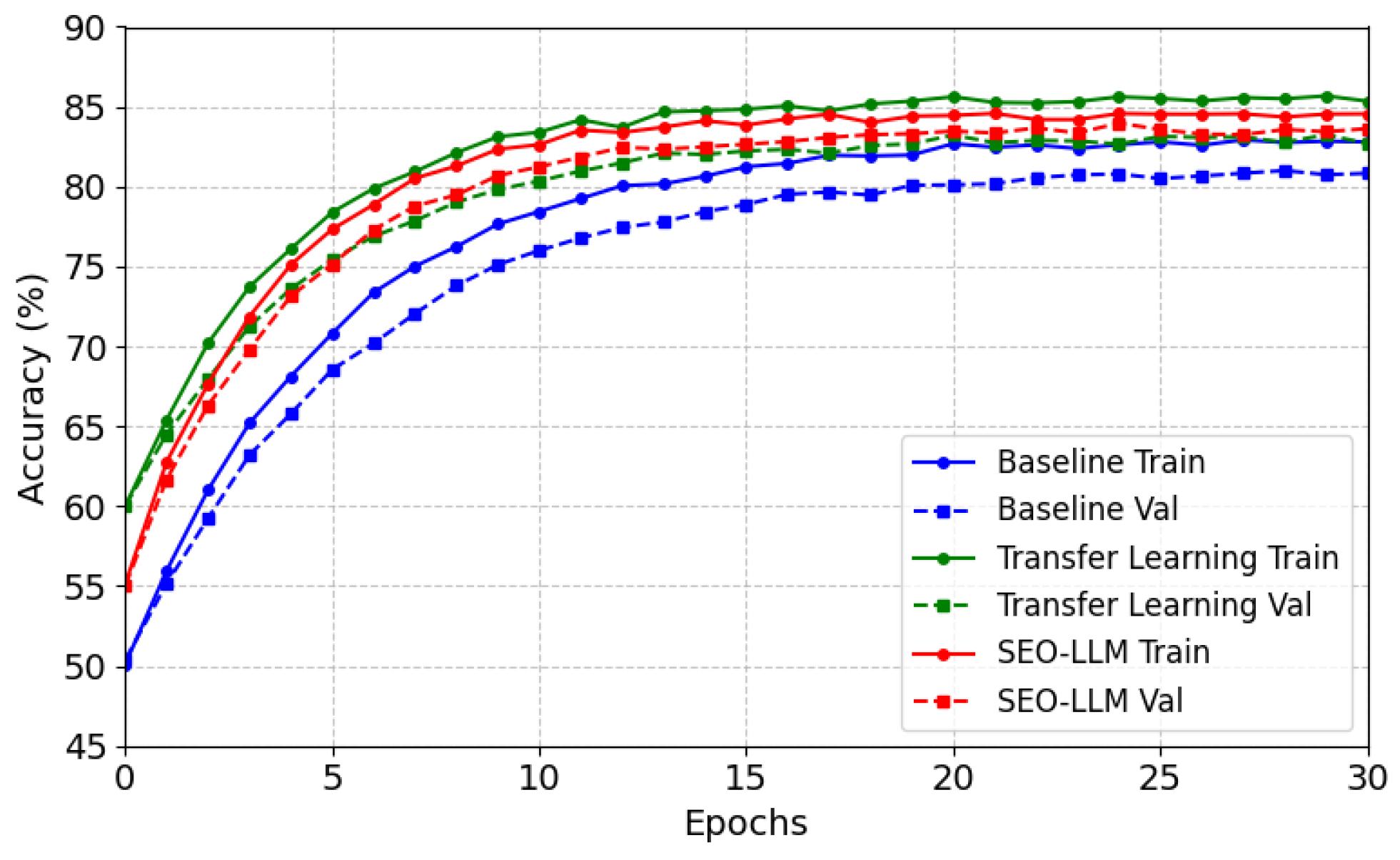

4.2. Model Accuracy with Each Epoch

4.3. Model Training Speed

4.4. Model Size

4.5. Model Inference Speed

4.6. Model Performance

5. Conclusions

References

- Achiam J, Adler S, Agarwal S, et al. Gpt-4 technical report[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, 2023.

- Anthropic. (2024). Claude 3.5. Anthropic. Retrieved from https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-5-sonnet.

- Touvron H, Lavril T, Izacard G, et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971, 2023.

- Wei, J., Wang, J., Zhou, Y., & Chen, J. (2018). Data Augmentation with Rule-based and Neural Network-based Techniques for Text Classification. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 2365-2374).

- Zhu, X., & Goldberg, A. B. (2009). Introduction to Semi-Supervised Learning. Synthesis Lectures on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, 3(1), 1-130.

- Kalyan K S. A survey of GPT-3 family large language models including ChatGPT and GPT-4[J]. Natural Language Processing Journal, 2023: 100048. [CrossRef]

- Raiaan M A K, Mukta M S H, Fatema K, et al. A review on large Language Models: Architectures, applications, taxonomies, open issues and challenges[J]. IEEE Access, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., ... & Amodei, D. (2020). Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14165.

- Bai, Y., Jones, A., Ndousse, K., Askell, A., Chen, A., Goldie, A., ... & Amodei, D. (2022). Training a Helpful and Harmless Assistant with Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.05862.

- Han, S., Mao, H., & Dally, W. J. (2015). Deep Compression: Compressing Deep Neural Networks with Pruning, Trained Quantization, and Huffman Coding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1510.00149.

- Li, H., Kadav, A., Durdanovic, I., Samet, H., & Graf, H. P. (2016). Pruning Filters for Efficient ConvNets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1608.08710.

- Polino, A., Pascanu, R., & Alistarh, D. (2018). Model Compression via Distillation and Quantization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.05668.

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., ... & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is All you Need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30.

- Dai H, Liu Z, Liao W, et al. Auggpt: Leveraging chatgpt for text data augmentation[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13007, 2023.

- Pellicer L F A O, Ferreira T M, Costa A H R. Data augmentation techniques in natural language processing[J]. Applied Soft Computing, 2023, 132: 109803. [CrossRef]

- Bayer M, Kaufhold M A, Buchhold B, et al. Data augmentation in natural language processing: a novel text generation approach for long and short text classifiers[J]. International journal of machine learning and cybernetics, 2023, 14(1): 135-150. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Yu Y, Zhang Q, et al. Losparse: Structured compression of large language models based on low-rank and sparse approximation[C]//International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023: 20336-20350.

- Jiang H, Wu Q, Lin C Y, et al. Llmlingua: Compressing prompts for accelerated inference of large language models[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.05736, 2023.

- Ge T, Hu J, Wang L, et al. In-context autoencoder for context compression in a large language model[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.06945, 2023.

- Ding, B., Qin, C., Zhao, R., Luo, T., Li, X., Chen, G., Xia, W., Hu, J., Luu, A. T., & Joty, S. (2024). Data augmentation using LLMs: Data perspectives, learning paradigms, and challenges. In L.-W. Ku, A. Martins, & V. Srikumar (Eds.), Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024 (pp. 1679–1705). Association for Computational Linguistics. Doi: 10.18653.

- Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Hinton, G. E. (2012). Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 25.

- Z. Peng, W. Zhang, N. Han, X. Fang, P. Kang and L. Teng, "Active Transfer Learning," in IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 1022-1036, April 2020. [CrossRef]

- Margatina, K., Schick, T., Aletras, N., & Dwivedi-Yu, J. (2023). Active learning principles for in-context learning with large language models. In H. Bouamor, J. Pino, & K. Bali (Eds.), Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023 (pp. 5011–5034). Association for Computational Linguistics., doi: 10.18653.

- Ma, X., Fang, G., & Wang, X. (2023). LLM-Pruner: On the structural pruning of large language models. In A. Oh, T. Naumann, A. Globerson, K. Saenko, M. Hardt, & S. Levine (Eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (Vol. 36, pp. 21702–21720).

- Han, S., Mao, H., & Dally, W. J. (2015). Deep compression: Compressing deep neural networks with pruning, trained quantization and huffman coding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1510.00149.

- Hinton, G. (2015). Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. arXiv preprint arXiv:1503.02531.

- Wang, A., Singh, A., Michael, J., Hill, F., Levy, O., & Bowman, S. R. (2019). GLUE: A multi-task benchmark and analysis platform for natural language understanding. Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

- Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S., Tu, Y., Han, X., He, C., Cui, G., Long, X., … & Zhao, W. (2024). Minicpm: Unveiling the potential of small language models with scalable training strategies. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.06395.

- Viswanathan, V., Zhao, C., Bertsch, A., Wu, T., & Neubig, G. (2023). Prompt2model: Generating deployable models from natural language instructions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.12261.

- He, N., Lai, H., Zhao, C., Cheng, Z., Pan, J., Qin, R., Lu, R., Lu, R., Zhang, Y., Zhao, G. (2023). Teacherlm: Teaching to fish rather than giving the fish, language modeling likewise. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.19019.

- Zhao, C., Jia, X., Viswanathan, V., Wu, T., & Neubig, G. (2024). SELF-GUIDE: Better Task-Specific Instruction Following via Self-Synthetic Finetuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.12874.

- Yang, Y., Zhou, J., Wong, N., & Zhang, Z. (2024). LoRETTA: Low-Rank Economic Tensor-Train Adaptation for Ultra-Low-Parameter Fine-Tuning of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), 3161-3176.

- Yang, Y., Zhen, K., Banijamal, E., Mouchtaris, A., & Zhang, Z. (2024). AdaZeta: Adaptive Zeroth-Order Tensor-Train Adaption for Memory-Efficient Large Language Models Fine-Tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.18060.

- Tan, Z., Dong, D., Zhao, X., Peng, J., & Cheng, Y. (2024). DLO: Dynamic Layer Operation for Efficient Vertical Scaling of LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.11030.

- Xiong, J., Li, Z., Zheng, C., Guo, Z., Yin, Y., Xie, E., Yang, Z., Cao, Q., Wang, H., Han, X. (2023). Dq-lore: Dual queries with low rank approximation re-ranking for in-context learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.02954.

- Fan, X., & Tao, C. (2024). Towards Resilient and Efficient LLMs: A Comparative Study of Efficiency, Performance, and Adversarial Robustness. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04585.

- Li, D., Tan, Z., & Chen, T. (2024). Contextualization distillation from large language model for knowledge graph completion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.01729.

- Tan, Z., Chen, T., Zhang, Z., & Liu, H. (2024). Sparsity-Guided Holistic Explanation for LLMs with Interpretable Inference-Time Intervention. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 38(19), 21619-21627. [CrossRef]

- Dou, J., Yu, C., Jiang, Y., Wang, Z., Fu, Q., Han, Y. (2023). Coreset Optimization by Memory Constraints, For Memory Constraints. Unpublished manuscript.

- Dou, J. X., Mao, H., Bao, R., Liang, P. P., Tan, X., Zhang, S., Jia, M., Zhou, P., & Mao, Z. (2023). Decomposable Sparse Tensor on Tensor Regression. In Proceedings of the AAAI 2023 Workshop on Representation Learning for Responsible Human-Centric AI (R2HCAI).

- Xiong, J., Wan, Z., Hu, X., Yang, M., & Li, C. (2022). Self-consistent reasoning for solving math word problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.15373.

- Xie, C., Chen, C., Jia, F., Ye, Z., Shu, K., Bibi, A., Hu, Z., Torr, P., Ghanem, B., & Li, G. (2024). Can Large Language Model Agents Simulate Human Trust Behaviors?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.04559.

- Chen, C., Huang, B., Li, Z., Chen, Z., Lai, S., Xu, X., Gu, J.C., Gu, J., Yao, H., Xiao, C., & others (2024). Can Editing LLMs Inject Harm?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.20224.

- Liu, W., Cheng, S., Zeng, D., Qu, H. (2023). Enhancing document-level event argument extraction with contextual clues and role relevance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.05991.

- Liu, W., Zhou, L., Zeng, D., Xiao, Y., Cheng, S., Zhang, C., Lee, G., Zhang, M., Chen, W. (2024). Beyond Single-Event Extraction: Towards Efficient Document-Level Multi-Event Argument Extraction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.01884.

- Fan, X., Tao, C., & Zhao, J. (2024). Advanced Stock Price Prediction with xLSTM-Based Models: Improving Long-Term Forecasting. Preprints, 2024082109.

- Yan, Chao & Wang, Jinyin & Zou, Yuelin & Weng, Yijie & Zhao, Yang & Li, Zhuoying. (2024). Enhancing Credit Card Fraud Detection Through Adaptive Model Optimization. [CrossRef]

- Xidong Wu, Feihu Huang, Zhengmian Hu, & Heng Huang. (2023). Faster Adaptive Federated Learning. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Li, Z., Yang, W., & Liu, C. (2023). Rt-lm: Uncertainty-aware resource management for real-time inference of language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.06619.

- Li, Y., Yu, X., Liu, Y., Chen, H., & Liu, C. (2023). Uncertainty-aware bootstrap learning for joint extraction on distantly-supervised data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.03827.

- Li, Z., Wang, B., & Chen, Y. (2024). A Contrastive Deep Learning Approach to Cryptocurrency Portfolio with US Treasuries. Journal of Computer Technology and Applied Mathematics, 1(3), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W. (2022). Optimizing distributed networking with big data scheduling and cloud computing. In International Conference on Cloud Computing, Internet of Things, and Computer Applications (CICA 2022) (pp. 23-28). SPIE.

- Li, D., Tan, Z., & Liu, H. (2024). Exploring Large Language Models for Feature Selection: A Data-centric Perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.12025.

- Liu, D., Wang, H., Qi, C., Zhao, P., & Wang, J. (2016). Hierarchical task network-based emergency task planning with incomplete information, concurrency and uncertain duration. Knowledge-Based Systems, 112, 67-79. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Qi, W., Zheng, H., & Shen, X. (2024). CU-Net: a U-Net architecture for efficient brain-tumor segmentation on BraTS 2019 dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.13113.

- Tan, Z., Beigi, A., Wang, S., Guo, R., Bhattacharjee, A., Jiang, B., ... & Liu, H. (2024). Large language models for data annotation: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.13446.

- Zhan, Q., Sun, D., Gao, E., Ma, Y., Liang, Y., & Yang, H. (2024). Advancements in Feature Extraction Recognition of Medical Imaging Systems Through Deep Learning Technique. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.18549.

- Dong, Z., Liu, X., Chen, B., Polak, P., & Zhang, P. (2024). Musechat: A conversational music recommendation system for videos. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 12775-12785).

- Dan, H. C., Lu, B., & Li, M. (2024). Evaluation of asphalt pavement texture using multiview stereo reconstruction based on deep learning. Construction and Building Materials, 412, 134837. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y., Gu, X., Feng, Z., Li, Z., & Sun, M. (2024). Feature Extraction and Model Optimization of Deep Learning in Stock Market Prediction. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 3(4). [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., You, Z., Li, R., Guan, Y., Qian, C., Zhao, C., Yang, C., Xie, R., Liu, Z., Sun, M. (2024). Internet of Agents: Weaving a Web of Heterogeneous Agents for Collaborative Intelligence. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.07061.

- Sanh, V., Debut, L., Chaumond, J., & Wolf, T. (2019). DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.01108.

- Liu, W., Cheng, S., Qu, H. (2024). Enhancing Credit Card Fraud Detection Through Adaptive Model Optimization. Unpublished manuscript.

| Model | Training Hours |

|---|---|

| BERT-base (baseline) | 48 |

| BERT-base + Data Augmentation | 43 |

| BERT-base + Transfer Learning | 39 |

| BERT-base + Active Learning | 36 |

| BERT-base + Semi-Supervised Learning | 37 |

| Model | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|

| BERT-base (baseline) | 420 |

| BERT-base + Pruning | 364 |

| BERT-base + Quantization | 150 |

| BERT-base + Knowledge Distillation | 201 |

| SEC (Combined approach) | 136 |

| Model | Inference Speed(ms/batch) |

|---|---|

| BERT-base (baseline) | 150 |

| BERT-base + Pruning | 130 |

| BERT-base + Quantization | 90 |

| BERT-base + Knowledge Distillation | 110 |

| SEC (Combined approach) | 80 |

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Perplexity |

|---|---|---|

| BERT-base (baseline) | 84.5 | 9.8 |

| BERT-base + Data Augmentation | 86.3 | 9.4 |

| BERT-base + Transfer Learning | 87.1 | 9.2 |

| BERT-base + Active Learning | 85.6 | 9.5 |

| BERT-base + Semi-Supervised Learning | 86.0 | 9.3 |

| BERT-base + Pruning | 83.5 | 10.1 |

| BERT-base + Quantization | 82.8 | 10.5 |

| BERT-base + Knowledge Distillation | 85.0 | 9.9 |

| SEC (Combined approach) | 86.2 | 9.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).