Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Design

2.2. Data and Sample Collection

2.3. Laboratory Analysis

2.3.1. Nutritional Composition

2.3.2. Serum Indices

2.3.3. Ruminal Fermentation Characteristics and Cellulases

2.3.4. Ruminal Flora Quantitative Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance

3.2. Thermal Stress Indicators

3.3. Serum Hormones and Metabolites

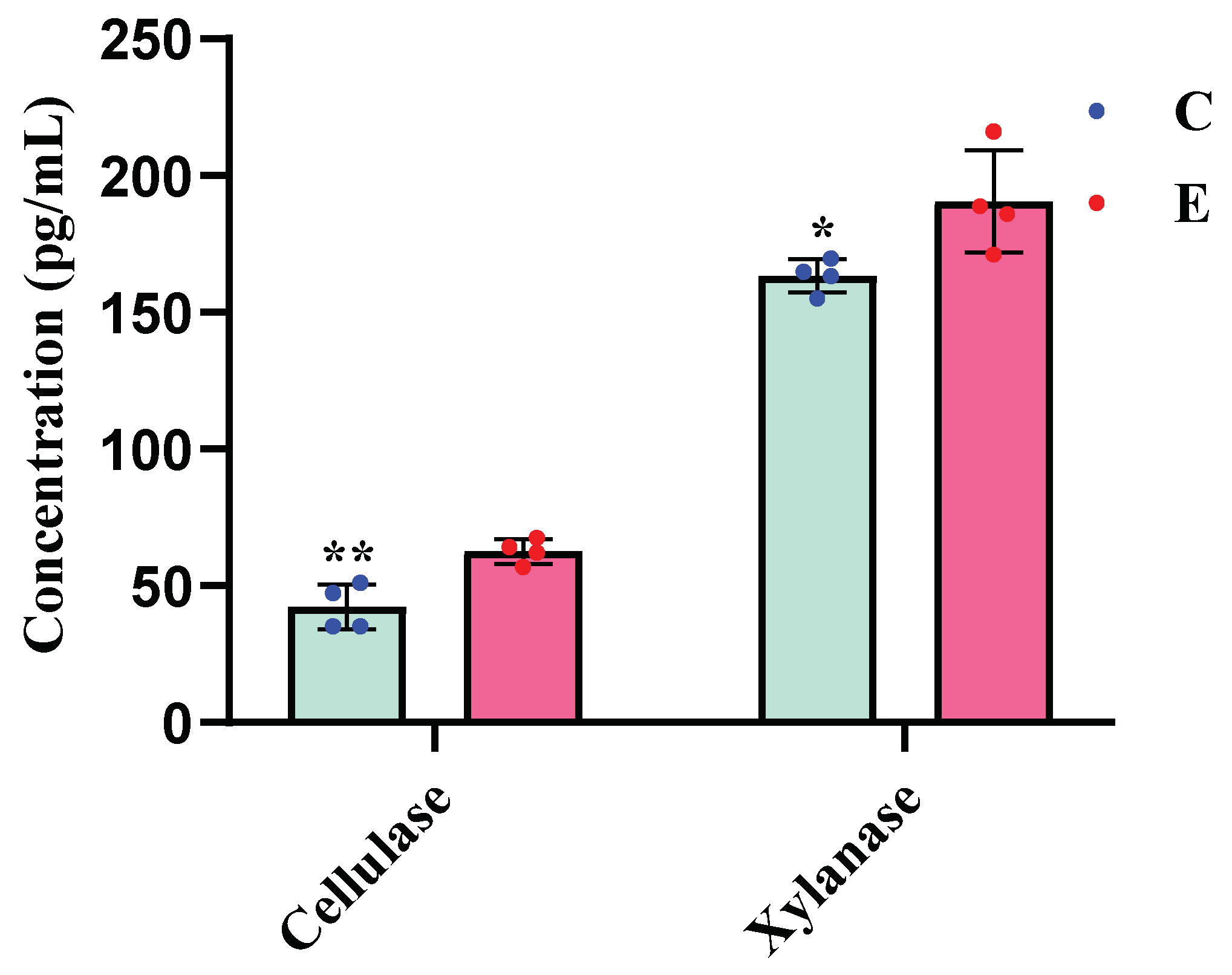

3.4. Ruminal Fermentation Characteristics and Fiber Enzyme Activity

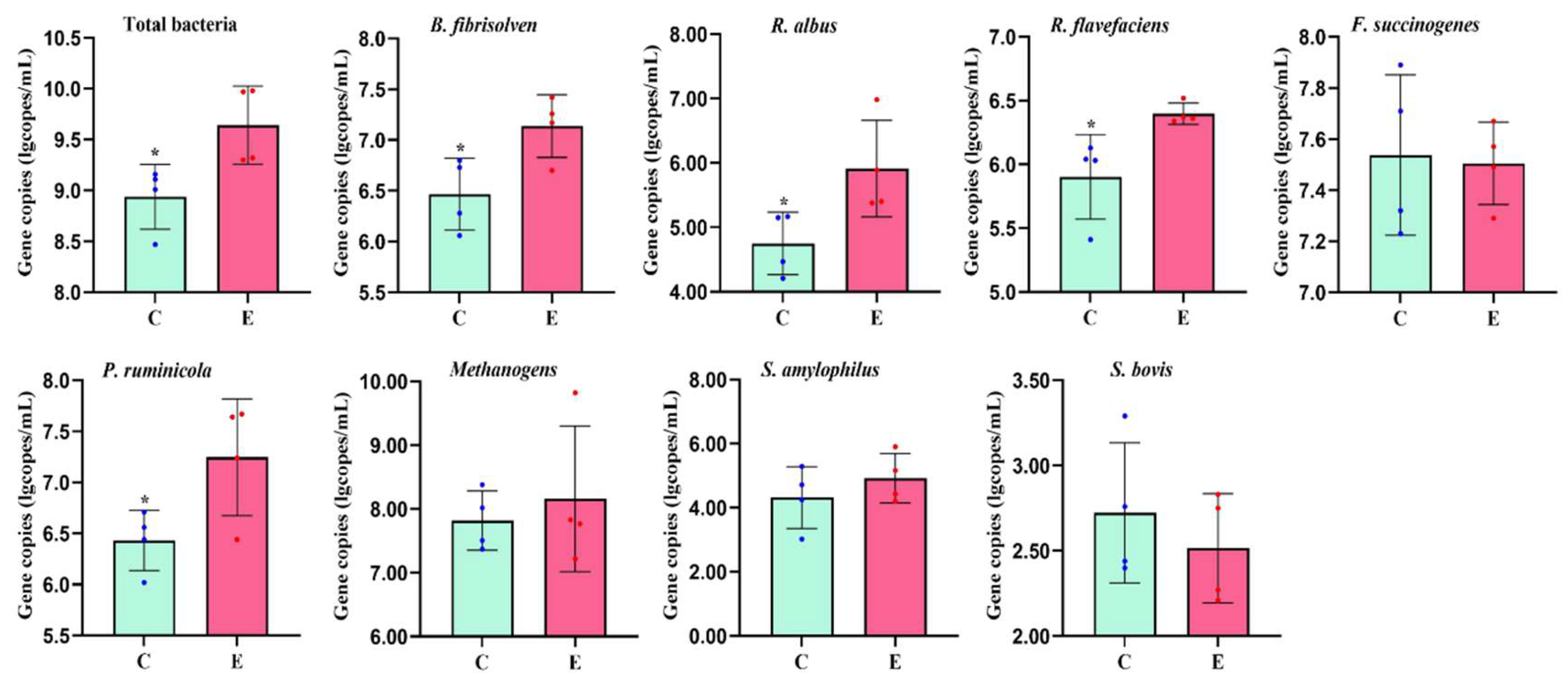

3.5. Rumen Bacterial Abundance

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth Performance

4.2. Thermal Stress Indicators

4.3. Serum Hormones and Metabolites

4.4. Ruminal Fermentation Characteristics and Cellulase

4.5. Rumen Bacterial Abundance

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gleason, C.B.; White, R.R. BEEF SPECIES-RUMINANT NUTRITION CACTUS BEEF SYMPOSIUM: A role for beef cattle in sustainable U.S. food production1. Journal of animal science, 2019, 97, 4010–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, G.B.; Fordyce, G.; Mcgowan, M.R.; et al. Perspectives for reproduction and production in grazing sheep and cattle in Australasia: The next 20 years. Theriogenology, 2024, 230, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbolini, S.; Bongiorni, S.; Cellesi, M.; et al. Genome wide association study on beef production traits in Marchigiana cattle breed. Journal of animal breeding and genetics = Zeitschrift fur Tierzuchtung und Zuchtungsbiologie, 2017, 134, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachut, M.; Šperanda, M.; DEAlmeida, A.M.; et al. Biomarkers of fitness and welfare in dairy cattle: healthy productivity. The Journal of dairy research, 2020, 87, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.S.; Rashamol, V.P.; Bagath, M.; et al. Impacts of heat stress on immune responses and oxidative stress in farm animals and nutritional strategies for amelioration. International journal of biometeorology, 2021, 65, 1231–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylander, B.L.; Repasky, E.A. Temperature as a modulator of the gut microbiome: what are the implications and opportunities for thermal medicine? International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group 2019, 36, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, J.W.; Tipton, M.J. Cold Stress Effects on Exposure Tolerance and Exercise Performance. Comprehensive Physiology, 2015, 6, 443–469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Cui, Z.; Wei, M.; et al. Omics analysis of the effect of cold normal saline stress through gastric gavage on LPS induced mice. Frontiers in microbiology, 2023, 14, 1256748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, S.; Xu, B.; Wang, D.; et al. Possible mechanisms of prenatal cold stress induced-anxiety-like behavior depression in offspring rats. Behavioural brain research, 2019, 359, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.G.; et al. Research and application of a new multilevel fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method for cold stress in dairy cows. Journal of dairy science, 2022, 105, 9137–9161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Peng, J.; et al. Effects of Long-Term Cold Stress on Growth Performance, Behavior, Physiological Parameters, and Energy Metabolism in Growing Beef Cattle. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Jia, D.; Sun, Y.; et al. Microbiota: A key factor affecting and regulating the efficacy of immunotherapy. Clinical and translational medicine, 2023, 13, e1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, L.; et al. Impact of Gut Microbiota and Microbiota-Related Metabolites on Hyperlipidemia. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 2021, 11, 634780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomaa, E.Z. Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: a review. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 2020, 113, 2019–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, K.; Nishida, A.; Inoue, R.; et al. Analysis of endoscopic brush samples identified mucosa-associated dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of gastroenterology, 2018, 53, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xia, S.; Jiang, X.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Diarrhea: An Updated Review. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 2021, 11, 625210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szóstak, N.; Figlerowicz, M.; Philips, A. The emerging role of the gut mycobiome in liver diseases. Gut microbes, 2023, 15, 2211922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brod, D.L.; Bolsen, K.K.; Brent, B.E. Effect of water temperature on rumen temperature, digestion and rumen fermentation in sheep. Journal of animal science, 1982, 54, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclean, J.; Tobin, G. Animal and human calorimetry; Cambridge university press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Berbert, Queiroz D M, Melo E C. AOAC. 2005. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. 18th Ed. USA.

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. Journal of dairy science, 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, G.A.; Kang, J.H. Automated simultaneous determination of ammonia and total amino acids in ruminal fluid and in vitro media. Journal of dairy science, 1980, 63, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, S.; et al. Tilapia head glycolipids reduce inflammation by regulating the gut microbiota in dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis mice. Food Funct, 2020, 11, 3245–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Cao, Y.; Liu, N.; et al. Subacute ruminal acidosis challenge changed in situ degradability of feedstuffs in dairy goats. Journal of dairy science, 2014, 97, 5101–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, T.; Long, S.; Yi, G.; et al. Heating Drinking Water in Cold Season Improves Growth Performance via Enhancing Antioxidant Capacity and Rumen Fermentation Function of Beef Cattle. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.Q.; Zhang, Z.W.; Qu, J.P.; et al. Cold stress induces antioxidants and Hsps in chicken immune organs. Cell stress & chaperones, 2014, 19, 635–648. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H.; et al. Effects of Drinking Water Temperature and Flow Rate during Cold Season on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility and Cecum Microflora of Weaned Piglets. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, Q.; Gao, C.; et al. Drinking Warm Water Promotes Performance by Regulating Ruminal Microbial Composition and Serum Metabolites in Yak Calves. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callet, T.; Dupont-Nivet, M.; Cluzeaud, M.; et al. Detection of new pathways involved in the acceptance and the utilisation of a plant-based diet in isogenic lines of rainbow trout fry. PloS one, 2018, 13, e0201462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, F.; Borchardt, S.; Schuenemann, G.M.; et al. Evaluation of 2 different treatment procedures after calving to improve harvesting of high-quantity and high-quality colostrum. Journal of dairy science, 2019, 102, 9370–9381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.M.; Milligan, L.P. Effects of cold exposure on digestion, microbial synthesis and nitrogen transformations in sheep. The British journal of nutrition, 1978, 39, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, H.; Ran, T.; et al. Influence of yeast culture and feed antibiotics on ruminal fermentation and site and extent of digestion in beef heifers fed high grain rations1. Journal of animal science, 2018, 96, 3916–3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serviento, A.M.; He, T.; Ma, X.; et al. Modeling the effect of ambient temperature on reticulorumen temperature, and drinking and eating behaviors of late-lactation dairy cows during colder seasons. Animal : an international journal of animal bioscience, 2024, 18, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, J.J.; Engle, T.E. Invited Review: Water consumption, and drinking behavior of beef cattle, and effects of water quality. Applied Animal Science, 2021, 37, 418–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, S.; Park, K.; Lee, S. Evaluation of thermal sensitivity is of potential clinical utility for the predictive, preventive, and personalized approach advancing metabolic syndrome management. The EPMA journal, 2022, 13, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brcko, C.C.; Da Silva JA, R.; Martorano, L.G.; et al. Infrared Thermography to Assess Thermoregulatory Reactions of Female Buffaloes in a Humid Tropical Environment. Frontiers in veterinary science, 2020, 7, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HUSVéTH F J D U, UNIVERSITY OF WEST HUNGARY, PANNON UNIVERSITY. P3. Physiological and reproductional aspects of animal production. 2011.

- Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, M.; et al. HOXA9 inhibits HIF-1α-mediated glycolysis through interacting with CRIP2 to repress cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma development. Nat Commun, 2018, 9, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, A.L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Effects of light regime on the hatching performance, body development and serum biochemical indexes in Beijing You Chicken. Poultry science, 2021, 100, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocalis, H.E.; Hagan, S.L.; George, L.; et al. Rictor/mTORC2 facilitates central regulation of energy and glucose homeostasis. Molecular metabolism, 2014, 3, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Shakhnovich, E.I. Is there an en route folding intermediate for Cold shock proteins? . Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society, 2012, 21, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, P.; Shen, L.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Association with Signalling Pathways in Inflammation, Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada Venegas, D.; De La Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; et al. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Frontiers in immunology, 2019, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; et al. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell, 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erny, D.; Dokalis, N.; Mezö, C.; et al. Microbiota-derived acetate enables the metabolic fitness of the brain innate immune system during health and disease. Cell metabolism, 2021, 33, 2260–2276.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghikia, A.; Zimmermann, F.; Schumann, P.; et al. Propionate attenuates atherosclerosis by immune-dependent regulation of intestinal cholesterol metabolism. European heart journal, 2022, 43, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, R.; et al. Propionate promotes ferroptosis and apoptosis through mitophagy and ACSL4-mediated ferroptosis elicits anti-leukemia immunity. Free radical biology & medicine, 2024, 213, 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- Luise, D.; Correa, F.; Stefanelli, C.; et al. Productive and physiological implications of top-dress addition of branched-chain amino acids and arginine on lactating sows and offspring. Journal of animal science and biotechnology, 2023, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hmad, I.; Mokni Ghribi, A.; Bouassida, M.; et al. Combined effects of α-amylase, xylanase, and cellulase coproduced by Stachybotrys microspora on dough properties and bread quality as a bread improver. International journal of biological macromolecules, 2024, 277, 134391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabee, A.E.; Forster, R.; Sabra, E.A. Lignocelluloytic activities and composition of bacterial community in the camel rumen. AIMS microbiology, 2021, 7, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoman, C.J.; Fields, C.J.; Lepercq, P.; et al. In Vivo Competitions between Fibrobacter succinogenes, Ruminococcus flavefaciens, and Ruminoccus albus in a Gnotobiotic Sheep Model Revealed by Multi-Omic Analyses. mBio 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, N.; et al. Effects of housing systems and glucose oxidase on growth performance and intestinal health of Beijing You Chickens. Poultry science, 2021, 100, 100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.K.; Muscha, J.M.; Mulliniks, J.T.; et al. Water temperature impacts water consumption by range cattle in winter. Journal of animal science, 2016, 94, 4297–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanuma, N.; Kawato, M.; Hino, T. Presence of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens in the digestive tract of dogs and cats, and its contribution to butyrate production. The Journal of general and applied microbiology, 2001, 47, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, J.; Yeom, Z.; et al. Neuroprotective effect of Ruminococcus albus on oxidatively stressed SH-SY5Y cells and animals. Scientific reports, 2017, 7, 14520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Præsteng, K.E.; Pope, P.B.; Cann, I.K.; et al. Probiotic dosing of Ruminococcus flavefaciens affects rumen microbiome structure and function in reindeer. Microbial ecology, 2013, 66, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; Gado, H.; Anele, U.Y.; et al. Influence of dietary probiotic inclusion on growth performance, nutrient utilization, ruminal fermentation activities and methane production in growing lambs. Animal biotechnology, 2020, 31, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; et al. Effects of riboflavin supplementation on performance, nutrient digestion, rumen microbiota composition and activities of Holstein bulls. The British journal of nutrition, 2021, 126, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Chen, L.; Zhou, C.; et al. Application of different proportions of sweet sorghum silage as a substitute for corn silage in dairy cows. Food science & nutrition, 2023, 11, 3575–3587. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Content |

| Ingredients, % | |

| Corn silage | 85.50 |

| Dry straw | 4.50 |

| Ground corn | 7.00 |

| Soybean meal | 2.50 |

| Calcium carbonate | 0.04 |

| Calcium hydrogen phosphate | 0.06 |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 0.10 |

| Sodium chloride | 0.08 |

| Limestone | 0.13 |

| Premix1 | 0.09 |

| Chemical composition, % of DM | |

| Dry matter | 87.26 |

| Organic matter | 94.47 |

| Crude protein | 8.14 |

| Ether extract | 6.53 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 61.95 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 34.24 |

| Calcium | 0.83 |

| Phosphorus | 0.27 |

| Metabolic energy (MJ kg-1)2 | 7.30 |

| Target gene | Primers | Primer sequence(5’→3’) | Size(bp) |

| Total bacteria | F | CGGCAACGAGCGCAACCC | 130 |

| R | CCATTGTAGCACGTGTGTAGCC | ||

| Ruminococcus albus | F | CCCTAAAAGCAGTCTTAGTTCG | 176 |

| R | CCTCCTTGCGGTTAGAACA | ||

| Ruminococcus flavus | F | CGAACGGAGATAATTTGAGTTTACTTAGG | 132 |

| R | CGGTCTCTGTATGTTATGAGGTATTACC | ||

| Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens | F | GCCTCAGCGTCAGTAATCG | 121 |

| R | GGAGCGTAGGCGGTTTTAC | ||

| Fibrobacter succinogenes | F | GTTCGGAATTACTGGGCGTAAA | 121 |

| R | CGCCTGCCCCTGAACTATC | ||

| Methanogens | F | TTCGGTGGATCDCARAGRGC | 232 |

| R | GBARGTCGWAWCCGTAGAATCC | ||

| Succinimonas amylolytica | F | CGTTGGGCGGTCATTTGAAAC | 139 |

| R | CCTGAGCGTCAGTTACTATCCAGA | ||

| Streptococcus bovis | F | ATGTTAGATGCTTGAAAGGAGCAA | 127 |

| R | CGCCTTGGTGAGCCGTTA | ||

| Prevotella ruminicola | F | GAAAGTCGGATTAATGCTCTATGTTG | 102 |

| R | CATCCTATAGCGGTAAACCTTTGG |

| Group2 | |||

| Item1 | C | E | P-value |

| IBW, kg | 359.34±10.62 | 371.57±14.56 | 0.523 |

| FBW, kg | 399.98±8.54 | 420.08±16.11 | 0.313 |

| ADG, kg/d | 0.95±0.05 | 1.15±0.03 | 0.024 |

| DMI, kg/d | 6.45±0.92 | 6.76±0.08 | 0.046 |

| F:G, ratio | 6.71±0.26 | 5.89±0.22 | 0.047 |

| Group1 | |||

| Item | C | E | P-value |

| Heat production, MJ/W0.75 h-1 | 29.64±6.95 | 25.76±4.52 | 0.385 |

| Respiratory rate, min-1 | 8.94±2.38 | 10.44±2.25 | 0.395 |

| Body surface temperature, ℃ | |||

| Spatial temperature 5-9℃ | 15.97±1.49 | 16.19±1.83 | 0.746 |

| Spatial temperature 9-11℃ | 20.67±1.64 | 21.06±0.43 | 0.673 |

| Spatial temperature 14-16℃ | 23.00±1.89 | 23.96±1.12 | 0.416 |

| Rectal temperature, ℃ | 38.00±0.50 | 38.24±0.23 | 0.417 |

| Group1 | |||

| Item | C | E | P-value |

| Triiodothyronine, ng/mL | 1.53±0.09 | 1.22±0.09 | 0.058 |

| Thyroxine, ng/mL | 134.28±1.04 | 128.99±1.35 | 0.021 |

| Growth hormone, ng/mL | 5.26±0.15 | 5.38±0.26 | 0.688 |

| Serum urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 6.79±0.40 | 5.55±0.13 | 0.025 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 4.85±0.09 | 4.40±0.08 | 0.011 |

| Total protein, g/L | 58.82±3.61 | 54.07±2.45 | 0.063 |

| Group2 | |||

| Item | C | E | P-value |

| Rumen pH | 7.27±0.04 | 7.19±0.03 | 0.061 |

| NH3-N, mg/dL | 4.67±0.19 | 5.23±0.11 | 0.048 |

| Total VFA, mM | 60.52±2.19 | 78.61±4.34 | 0.010 |

| Acetate, mM | 41.92±1.62 | 55.14±3.04 | 0.009 |

| Propionate, mM | 10.26±0.40 | 13.49±0.75 | 0.009 |

| Butyrate, mM | 4.53±0.18 | 5.30±0.29 | 0.066 |

| Iso-butyrate, mM | 0.88±0.08 | 1.09±0.06 | 0.074 |

| Valerate, mM | 1.19±0.11 | 1.47±0.08 | 0.091 |

| Iso-valerate, mM | 1.25±0.17 | 2.11±0.21 | 0.139 |

| A:P, ratio1 | 4.36±0.08 | 4.48±0.17 | 0.539 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).