Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

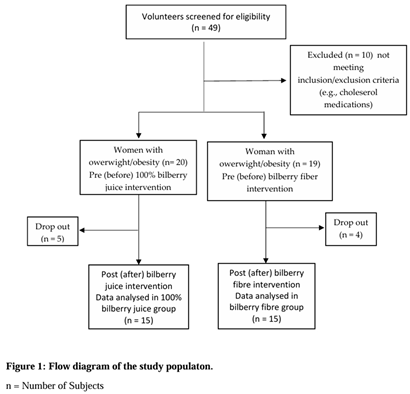

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Anthropometric Measurements

2.4. Preparation of Blood Samples

2.5. Clinical Parameters

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Bioactive Compounds in 100% Bilberry Juice and Dietary Fibre of Bilberry

3.2. Characteristics of Study Participants

3.2.1. Anthropometric Parameters and Blood Pressure Measurements

3.1.2. Changes in Basic Lipid Profile Parameters and Lipoprotein Indexes

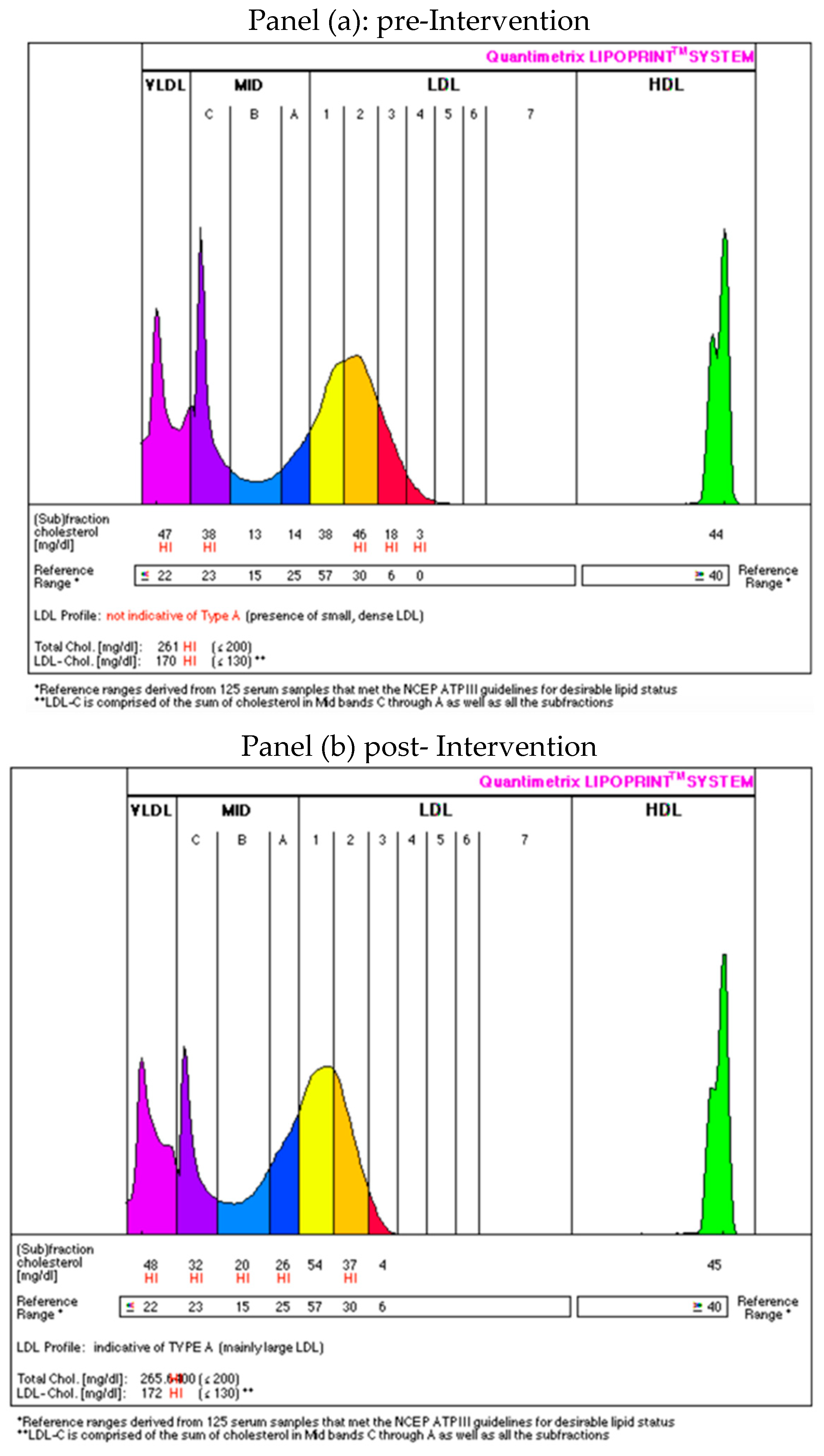

3.1.3. Changes in Lipoprotein Subfractions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BFM | Body Fat Mass |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid |

| FFM | Fat-Free Mass |

| GAE | Gallin Acid Equivalent |

| HDL | High Density Lipoprotein |

| HDL-C | High Density Cholesterol |

| IDL | Intermediate-Density Lipoprotein |

| LDL | Law Density Lipoprotein |

| LDL-C | Law Density Cholesterol |

| MFBIA | Multi-Frequency Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis |

| NCEP ATP III | National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III |

| TC | Total Cholesterol |

| LDL | Law Density Cholesterol |

| NFC | Not From Concentrate |

| PBF | Body Fat Percentage |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| sdLDL | Small-Dense Low-Density Cholesterol |

| SSM | Skeletal Muscle Mass |

| TC/HDL | Ratio of Total Cholesterol to High-Density Lipoprotein |

| TAG | Triacylglycerol |

| VFA | Visceral Fat Area |

| VLDL | Very-Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| WC | Waist Circumference |

| WHR | Waist-To-Hip Ratio |

References

- WHO. 2024. Obesity and overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 10 January, 2025).

- Saxena, I.; Preet Kaur, A.; Suman, S. et al. The Multiple Consequences of Obesity. In Weight Management - Challenges and Opportunities. IntechOpen. Anthem AZ, USA, 2022, 250 p. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.104764.

- Taylor, V.H.; Forhan, M.; Vigod, S.N.; McIntyre, R.S.; Morrison, K.M. The impact of obesity on quality of life. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2013, 27, 139-146. [CrossRef]

- Koskinas, K.C.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.M.; Antoniades, C.; Blüher, M.; Gorter, T.M.; Hanssen, H.; Marx, N.; McDonagh, T.A.; Mingrone, G.; Rosengren, A;, Prescott, E.B.; ESC Scientific Document Group. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: an ESC clinical consensus statement. European Heart Journal 2024, 45, 4063–4098. [CrossRef]

- Minglan, J.; Xiao, R.; Longyang, H.; Xiaowei, Z. Associations between sarcopenic obesity and risk of cardiovascular disease: A population-based cohort study among middle-aged and older adults using the CHARLS. Clinical Nutrition 2024, 43, 796-802, . [CrossRef]

- Perone, F.; Pingitore, A.; Conte, E.; Halasz, G.; Ambrosetti, M.; Peruzzi, M.; Cavarretta, E. Obesity and Cardiovascular Risk: Systematic Intervention Is the Key for Prevention. Healthcare 2023, 11, 902. [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Garvey, W.T. Cardiometabolic Disease Risk in Metabolically Healthy and Unhealthy Obesity: Stability of Metabolic Health Status in Adults. Obesity 2016, 24, 516-525. [CrossRef]

- Halland, H.; Lønnebakken, M.T.; Pristaj, N.; Saeed, S.; Midtbø, H.; Einarsen, E.; Gerdts, E. Sex differences in subclinical cardiac disease in overweight and obesity (the FATCOR study). Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2018, 28, 1054-1060. [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiyari, M.; Kazemian, E.; Kabir, K.; Hadaegh, F.; Aghajanian, S.; Mardi, P.; Ghahfarokhi, N.T.; Ghanbari, A.; Mansournia, M.A.; Azizi, F. Contribution of obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors in developing cardiovascular disease: A population-based cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1544. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Almahmeed, W.; Bays, H.; Cuevas, A.; Di Angelantonio, E.; le Roux, C.W.; Sattar, N.; Sun, M.C.; Wittert, G.; Pinto, F.J.; Wilding, J.P.H. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Mechanistic insights and management strategies. A joint position paper by the World Heart Federation and World Obesity Federation. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 2218–2237. [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.C.; Pang, J.; Watts, G.F. Dyslipidemia in Obesity. In Ahima, R.S. (eds) Metabolic Syndrome. 2016, Springer, Cham. Available at: . [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Ridker, P.M.; Maseri, A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002, 105, 1135–1143. [CrossRef]

- Chary, A.; Tohidi, M.; Hedayati, M. Association of LDL-cholesterol subfractions with cardiovascular disorders: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023, 23, 533. [CrossRef]

- Deza, S.; Colina, I.; Beloqui, O.; Monreal, J. I.; Martínez-Chávez, E.; Maroto-García, J.; Mugueta, C.; González, A.; Varo, N. Evaluation of measured and calculated small dense low-density lipoprotein in capillary blood and association with the metabolic syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2024, 557, 117897. [CrossRef]

- Sikand, G.; Severson, T. Top 10 dietary strategies for atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk reduction. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 4, 100106. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, I.; Wilairatana, P.; Saqib, F.; Nasir, B.; Wahid, M.; Latif, M. F.; Iqbal, A.; Naz, R.; Mubarak, M. S. Plant Polyphenols and Their Potential Benefits on Cardiovascular Health: A Review. Molecules. 2023, 28, 6403. [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.; Dordevic, A.L.; Ryan, L.; Bonham, M.P. An emerging trend in functional foods for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: Marine algal polyphenols. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1342–1358. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Kortesniemi, M. Clinical evidence on potential health benefits of berries. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 2, 36-42. [CrossRef]

- Habanova, M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Haban, M.; Schwarzova, M.; Chlebo, P.; Predna, L; Gažo, J.; Wyka, J. Intake of bilberries (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) reduced risk factors for cardiovascular disease by inducing favorable changes in lipoprotein profiles. Nutr Res. 2016, 36, 1415-1422. [CrossRef]

- Habanova, M.; Holovicova, M.; Scepankova, H.; Lorkova, M.; Gazo, J.; Gazarova, M.; Pinto, C.A.; Saraiva, J.A.; Estevinho, L.M. Modulation of Lipid Profile and Lipoprotein Subfractions in Overweight/Obese Women at Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases through the Consumption of Apple/Berry Juice. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022, 11, 2239. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Muscat, J.E.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Al-Shaar, L.; Richie, J.P. The Epidemiology of Berry Consumption and Association of Berry Consumption with Diet Quality and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in United States Adults: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2018. J Nutr. 2024, 154, 1014-1026. [CrossRef]

- Donno, D.; Neirotti, G.; Fioccardi, A.; Razafindrakoto, Z.R.; Tombozara, N.; Mellano, M.G.; Beccaro, G.L.; Gamba, G. Freeze-Drying for the Reduction of Fruit and Vegetable Chain Losses: A Sustainable Solution to Produce Potential Health-Promoting Food Applications. Plants 2025, 14, 168. [CrossRef]

- Yousdefizadeh, S.; Farkhondeh, T.; Almzadeh, E.; Samarghandian, S. A Systematic Study on the Impact of Blueberry Supplementation on Metabolic Syndrome Components. Curr Nutr Food Sci. 2025, 21, 333–340. [CrossRef]

- Pires, T.C.S.P.; Caleja, C.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Vaccinium myrtillus L. Fruits as a Novel Source of Phenolic Compounds with Health Benefits and Industrial Applications - A Review. Curr Pharm Des. 2020, 26, 1917-1928. [CrossRef]

- Thiese, M.S. Observational and interventional study design types; an overview. Lessons Biostat. 2014, 24, 199–210. [CrossRef]

- Lachman, J.; Hamouz, K.; Čepl J.; Pivec, V.; Šulc, M.; Dvořák, P. The Effect of Selected Factors on Polyphenol Content and Antioxidant Activity in Potato Tubers. Chem. Listy. 2006, 100, 522-527. http://www.chemicke-listy.cz/ojs3/index.php/chemicke-listy/article/view/1916/1916.

- Lapornik, B.; Prošek, M.; Golc Wondraet, A. Comparison of extracts prepared from plant by-products using different solvents and extraction time. J. Food Eng. 2005, 71, 214-222. [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, M.; Pucci, L.; Árvay, J.; Longo V. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect of fermented whole wheat on TNFα-stimulated HT-29 and NF-κB signalling pathway activation. J Functional Foods. 2018, 48, 392-400. [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, Y.; Lobo, M.G.; Gonzálezet, M. Determination of vitamin C in tropical fruits: A comparative evaluation of methods. Food Chem. 2006, 96, 654-664. [CrossRef]

- Skrzypczak, M.; Szwed, A.; Pawli, R.; Skrzypulec, V. Assessment of the BMI, WHR and W/Ht in pre- and postmenopausal women. Anthropol. Rev. 2007, 70, 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; MacLaughlin, E.J.; Muntner, P.; Ovbiagele, B.; Smith, S.C.; Spencer, C.C.; Stafford, R.S.; Taler, S.J.; Thomas, R.J.; Williams, K.A.; Williamson, J.D.; Wright, J. T. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018, 71, 1269-1324. [CrossRef]

- NCEP ATP III. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001, 285, 2486-2497. [CrossRef]

- Millán, J.; Pintó, X.; Muñoz, A.; Zúñiga, M.; Rubiés-Prat, J.; Pallardo, L.F.; Masana, L.; Mangas, A.; Hernández-Mijares, A.; González-Santos, P.; Ascaso, J.F.; Pedro-Botet, J. Lipoprotein ratios: Physiological significance and clinical usefulness in cardiovascular prevention. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 757-765.

- Dobiásová, M. AIP-atherogenic index of plasma as a significant predictor of cardiovascular risk: from research to practice. Vnitr Lek. 2006, 52, 64-71. https://www.casopisvnitrnilekarstvi.cz/pdfs/vnl/2006/01/14.pdf.

- Zitnanova, I.; Oravec, S.; Janubova, M.; Konarikova, K.; Dvorakova, M.; Laubertova, L.; Kralova, M.; Simko, M.; Muchova, J. Gender differences in LDL and HDL subfractions in atherogenic and nonatherogenic phenotypes. Clin Biochem. 2020, 79, 9-13. [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.D.; McGregor, J.C.; Perencevich, E.N.; Furuno, J.P.; Zhu, J.; Peterso, D.E.; Finkelstein, J. The Use and Interpretation of Quasi-Experimental Studies in Medical Informatics. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2006, 13, 16–23. [CrossRef]

- Lavefve, L.; Howard, L.R; Carboneroi, F. Berry polyphenols metabolism and impact on human gut microbiota and health. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 45-65. [CrossRef]

- Vaneková, Z.; Rollinger, J.M. Bilberries: Curative and Miraculous - A Review on Bioactive Constituents and Clinical Research. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 909914. [CrossRef]

- Brezoiu, A.M.; Deaconu, M.; Mitran, R.-A.; Sedky, N.K.; Schiets, F.; Marote, P.; Voicu, I.-S.; Matei, C.; Ziko, L.; Berger, D. The Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Wild Bilberry Fruit Extracts Embedded in Mesoporous Silica-Type Supports: A Stability Study. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 250. [CrossRef]

- Kalt, W.; Cassidy, A.; Howard, L.R.; Krikorian, R.; Stull, A.J.; Tremblay, F.; Zamora-Ros, R. Recent Research on the Health Benefits of Blueberries and Their Anthocyanins. Adv Nutr. 2020, 11, 224-236. [CrossRef]

- Yaqiong, W.; Tianyu, H.; Hao, Y.; Lianfei, Lyu.; Weilin, L., Wenlong Wu. Known and potential health benefits and mechanisms of blueberry anthocyanins: A review. Food Bioscience 2023, 55, 103050. [CrossRef]

- Negrușier, C.; Colișar, A.; Rózsa, S.; Chiș, M.S.; Sîngeorzan, S.-M.; Borsai, O.; Negrean, O.-R. Bilberries vs. Blueberries: A Comprehensive Review. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1343. [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.L.; Peterson, J.J.; Patel, R.; Jacques, P.F.; Shah, R.; Dwyer, J.T. Flavonoid intake and cardiovascular disease mortality in a prospective cohort of US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 95, 454-64. [CrossRef]

- Habauzit, V.; Verny, M.A.; Milenkovic, D.; Barber-Chamoux, N.; Mazur, A.; Dubray, C.; Morand, C. Flavanones protect from arterial stiffness in postmenopausal women consuming grapefruit juice for 6 mo: a randomized, controlled, crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015, 102, 66-74. [CrossRef]

- Michalska, A.; Łysiak, G. Bioactive Compounds of Blueberries: Post-Harvest Factors Influencing the Nutritional Value of Products. Int J Mol Sci. 2015, 16, 18642-18663. [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, S.; Kunz, C.; Rudloff, S. Inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell migration by plasma anthocyanins isolated from healthy volunteers receiving an anthocyanin-rich berry juice. Eur J Nutr. 2017, 56, 203-214. [CrossRef]

- Mendelová, A.; Mendel, Ľ.; Fikselová, M.; Czako, P. Evaluation of anthocynin changes in blueberries and in blueberry jam after the processing and storage. Potravinarstvo Slovak Journal of Food Sciences 2013, 7, 130–135. http://dx.doi.org/10.5219/293.

- Wu, X.; Beecher, G.R.; Holden, J.M.; Haytowitz, D.B.; Gebhardt, S.E.; Prior, R.L. Concentrations of anthocyanins in common foods in the United States and estimation of normal consumption. J Agric Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4069-4975. [CrossRef]

- Skrovankova, S.; Sumczynski, D.; Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T.; Sochor, J. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Different Types of Berries. Int J Mol Sci. 2015, 16, 24673-706. [CrossRef]

- Casas-Forero, N.; Orellana-Palma, P.; Petzold, G. Comparative Study of the Structural Properties, Color, Bioactive Compounds Content and Antioxidant Capacity of Aerated Gelatin Gels Enriched with Cryoconcentrated Blueberry Juice during Storage. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 2769. [CrossRef]

- Zorzi, M.; Gai, F.; Medana, C.; Aigotti, R.; Morello, S.; Peiretti, P.G. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Small Berries. Foods 2020, 9, 623. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.Y.; Zhang, H.C.; Liu, W.X.; Li, C.Y. Survey of antioxidant capacity and phenolic composition of blueberry, blackberry, and strawberry in Nanjing. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2012, 13, 94-102. [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.; Hein, S.; Heiss, C.; Williams, C.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A. Blueberries and cardiovascular disease prevention. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 7621-7633. [CrossRef]

- Azari, H.; Morovati, A.; Pourghassem Gargari, B.; Sarbakhsh, P. Beneficial effects of blueberry supplementation on the components of metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 4875-4900. [CrossRef]

- Kolehmainen, M.; Mykkänen, O.; Kirjavainen, P.V.; Leppänen, T.; Moilanen, E.; Adriaens, M. et al. Bilberries reduce low-grade inflammation in individuals with features of metabolic syndrome. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2012, 56, 1501-1510. [CrossRef]

- Stull, A.J.; Cash, K.C.; Johnson, W.D.; Champagne, C.M.; Cefalu, W.T. Bioactives in blueberries improve insulin sensitivity in obese, insulin-resistant men and women. J Nutr. 2010, 140, 1764-1768. [CrossRef]

- Niroumand, S.; Khajedaluee, M.; Khadem-Rezaiyan, M.; Abrishami, M.; Juya, M.; Khodaee, G.; Dadgarmoghaddam, M. Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP): A marker of cardiovascular disease. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2015, 29, 240. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4715400/.

- Huang, H.; Chen, G.; Liao, D.; Zhu, Y.; Xue, X. Effects of Berries Consumption on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Meta-analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 23625. [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, T.; Litts, C.; Horgan, G.; Zhang, X.; Hoggard, N.; Russell, W.; de Roos, B. Efficacy of Bilberry and Grape Seed Extract Supplement Interventions to Improve Glucose and Cholesterol Metabolism and Blood Pressure in Different Populations-A Systematic Review of the Literature. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 1692. [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Rifai, N.; Rose, L.; Buring, J.E.; Cook, N.R. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347, 1557-1565. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wang, D.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z. Comparison of lipoprotein derived indices for evaluating cardio-metabolic risk factors and subclinical organ damage in middle-aged Chinese adults. Clin Chim Acta. 2017, 475, 22-27. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Aparicio, Á.; Perona, J.S.; Schmidt-RioValle, J.; Padez, C.; González-Jiménez, E. Assessment of Different Atherogenic Indices as Predictors of Metabolic Syndrome in Spanish Adolescents. Biol Res Nurs. 2022, 24, 163-171. [CrossRef]

- Calling, S.; Johansson, S.E.; Wolff, M.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. The ratio of total cholesterol to high density lipoprotein cholesterol and myocardial infarction in Women's health in the Lund area (WHILA): a 17-year follow-up cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019, 19, 239. [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Chen, M.; Shen, H.; PingYin, Fan, L.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J. Predictive value of LDL/HDL ratio in coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022, 22, 273. [CrossRef]

- Oravec, S.; Dukat, A.; Gavornik, P.; Kucera, M.; Gruber, K.; Gaspar, L.; Rizzo, M.; Toth, P.P.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Banach, M. Atherogenic versus non-atherogenic lipoprotein profiles in healthy individuals. is there a need to change our approach to diagnosing dyslipidemia? Curr Med Chem. 2014, 21, 2892-901. [CrossRef]

- Kasko, M.; Gaspar, L.; Dukát, A.; Gavorník, P.; Oravec, S. High-density lipoprotein profile in newly-diagnosed lower extremity artery disease in Slovak population without diabetes mellitus. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2014, 35, 531-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25433844/.

- Vekic, J.; Zeljkovic, A.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Janez, A.; Stoian, A.P.; Sonmez, A.; Rizzo, M. Atherosclerosis Development and Progression: The Role of Atherogenic Small, Dense LDL. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022, 58, 299. [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Fu, D.X.; Wilkinson, M.; Simmons, B.; Wu, M.; Betts, N.M.; Du, M.; Lyons, T.J. Strawberries decrease atherosclerotic markers in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res. 2010, 30, 462-9. [CrossRef]

- Habanova, M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Holovicova, M.; Moreira, S.A.; Fidalgo, L.G.; Haban, M.; Gazo, J.; Schwarzova, M.; Chlebo, P.; Bronkowska, M. Effect of berries/apple mixed juice consumption on the positive modulation of human lipid profile. J. Funct. Foods. 2019, 60, 103417. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | 100% Bilberry Juice | Dietary Fibre of Bilberry |

| Total phenolic content (mg GAE*/g) | 2.29±0.01 | 32.81±0.15 |

| Total anthocyanins (mg/g) | 1.48±0.03 | 6.82±0.06 |

| Caffeic acid (mg/L) | 24.87±0.41 | 85.47±0.31 |

| Coumaric acid (mg/L) | 28.59±1.57 | 125.35±0.26 |

| Ferulic acid (mg/L) | 123.11±0.83 | 77.94±0.21 |

| Rutin (mg/L) | 309.95±1.27 | 24.21±0.08 |

| Myricetin (mg/L) | 34.66±1.73 | 52.79±0.44 |

| Resveratrol (mg/L) | 9.50±0.74 | 30.15±0.39 |

| Quercetin (mg/L) | 5.44±0.04 | 53.45±1.05 |

| Antioxidant activity (%) | 49.30±0.56 | 67.20±0.41 |

| Vitamin C (µg/g) | 126.40±0.13 | 1.44±0.12 |

| Parameter | 100% bilberry juice (n=15) | Dietary fibre of bilberry (n=15) | ||||

| pre | post | p | pre | post | p | |

| Bodyweight (kg) | 80.14±11.86 | 80.17±11.97 | 0.853 | 80.56±8.68 | 81,09±9,12 | 0,116 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.89±3.75 | 29.90±3.81 | 0.842 | 29.52±3.06 | 29,71±3,13 | 0,125 |

| WC (cm) | 103.39±10.49 | 104.21±9.85 | 0.084 | 100.93±7.11 | 101,66±7,52 | 0,083 |

| WHR index | 1.00±0.06 | 1.01±0.05 | 0.073 | 0.97±0.05 | 0,98±0,05 | 0,086 |

| SMM (kg) | 24.99±2.57 | 25.12±2.51 | 0.151 | 26.76±3.33 | 26,86±3,30 | 0,388 |

| FFM (kg) | 45.78±4.48 | 45,.6±4.41 | 0.334 | 48.59±5.61 | 48,77±5,54 | 0,313 |

| FFM (%) | 57.39±4.10 | 57.66±4.26 | 0.256 | 60.48±4.83 | 60,33±4,73 | 0,516 |

| BFM (kg) | 34.08±8.40 | 33.98±8.62 | 0.614 | 31.97±5,92 | 32,32±6,11 | 0,237 |

| PBF (%) | 42.44±4.18 | 42.20±4.39 | 0.274 | 39.53±4,83 | 39,66±4,74 | 0,561 |

| VFA (cm2) | 134.18±26.46 | 134.56±25.24 | 0.596 | 124.64±18,99 | 126,59±20,26 | 0,071 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 126.93±13.83 | 124.67±11.73 | 0.271 | 129.80±12,23 | 128,07±11,93 | 0,508 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 83.80±6.93 | 82.20±4.65 | 0.244 | 87.53±6,52 | 86,87±6,51 | 0,692 |

| Parameter | 100% Bilberry Juice (n=15) | Dietary Fibre of Bilberry (n=15) | |||||

| pre | post | p | pre | post | p | RV | |

| TC (mmol/L) | 6.41±1.23 | 6.94±1.30 | <0.001 | 6.06±1.39 | 6.43±1.05 | 0.046 | 3-5.2 |

| TAG (mmol/L) | 1.34±0.50 | 1.38±0.47 | 0.721 | 1.41±0.65 | 1.39±0.68 | 0.880 | <1.7 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.70±0.94 | 3.42±1.00 | 0.010 | 3.56±0.81 | 3.08±0.62 | 0.001 | <2.6 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.78±0.32 | 2.11±0.38 | <0.001 | 1.60±0.43 | 1.92±0.52 | <0.001 | >1.3 |

| TC/HDL | 3.69±0.92 | 3.33±0.63 | 0.006 | 3.92±0.90 | 3.48±0.72 | <0.001 | <4 |

| LDL/HDL | 2.15±0.71 | 1.65±0.49 | <0.001 | 2.34±0.71 | 1.69±0.49 | <0.001 | <2.5 |

| AIP index | -0.14±0.21 | -0.20±0.18 | 0.152 | -0.08±0.25 | -0.17±0.26 | 0.061 | -0.3-0.1 |

| Parameter | 100% Bilberry Juice (n=12) | Dietary Fibre of Bilberry (n=9) | ||||

| pre | post | p | pre | post | p | |

| LDL subfractions | ||||||

| VLDL (mmol/L) | 1.04±0.20 | 1.19±0.25 | 0.011 | 1.12±0.30 | 1.25±0.41 | 0.098 |

| IDL A (mmol/L) | 0.47±0.22 | 0.75±0.18 | <0.001 | 0.49±0.27 | 0.60±0.23 | 0.168 |

| IDL B (mmol/L) | 0.40±0.16 | 0.51±0.12 | 0.008 | 0.41±5.15 | 0.51±0.09 | 0.084 |

| IDL C (mmol/L) | 0.85±0.24 | 0.63±0.45 | 0.041 | 0.81±0.23 | 0.70±0.15 | 0.246 |

| LDL 1 (mmol/L) | 1.07±0.32 | 1.35±0.35 | 0.009 | 1.04±0.36 | 1.13±0.18 | 0.430 |

| LDL 2 (mmol/L) | 0.87±0.35 | 0.75±0.42 | 0.088 | 0.90±0.28 | 0.84±0.43 | 0.937 |

| LDL 3-7 (mmol/L) | 0.26±0.23 | 0.11±0.16 | 0.016 | 0.31±0.32 | 0.24±0.31 | 0.261 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).