1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer ranked third in incidence and second in mortality among malignant diseases worldwide in 2022 [

1]. Rectal cancer accounts for approximately 35% of all colorectal cancers. The standard treatment for locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) includes neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT), followed by surgery with or without adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) [

2].

Pathological complete regression (pCR) after nCRT is achieved in 10-30% of patients and is associated with better disease control and longer survival [

3]. To achieve a higher rate of complete response (CR) to neoadjuvant therapy, research has focused on prolonging the interval between neoadjuvant treatment completion and surgery, increasing radiotherapy (RT) doses, and modifying the type and regimen of CT administration [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Advances in RT techniques have enabled dose escalation to the area of macroscopically visible disease, while better sparing surrounding organs at risk. The introduction of 3D conformal radiation therapy (3D CRT) allowed for better adaptation (conformation) of the number and shape of radiation fields to the target volume. However, the anatomical proximity of the bladder and small intestine limited their maximal sparing. Simultaneous dose escalation within the tumor volume is achieved using intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) or volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) techniques. This approach shortens the duration of nCRT compared to the conventional method, which involves dose escalation in a second phase of radiotherapy (sequential dose escalation).

Studies have shown that dose-escalated RT achieves a higher pCR rate and improved local disease control [

11]. Yang et al. investigated the use of a daily dose per fraction of 2.35 Gy to a total tumor dose (TD) of 58.75 Gy in 25 fractions using VMAT for distally located LARC [

8]. The results demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach, with 32% pCR, 60% sphincter preservation, negative surgical margins in all patients, and downstaging in 92% of cases [

8]. Toxicity was mostly grade 1 and 2, with no grade 4 toxicity observed [

8]. A phase 2 study evaluating the efficacy and toxicity of the VMAT simultaneous integrated boost (SIB) technique, with a total dose of 57.5 Gy (2.3 Gy per fraction) in preoperative combined treatment of LARC patients, showed excellent pathological response [

11]. However, high-grade toxicity was observed in more than one-third of patients. The study included 18 patients, all of whom achieved negative resection margins, with one-year, three-year, and five-year disease-free survival (DFS) rates of 88.9%, 66.7%, and 66.7%, respectively [

11].

Only sporadic studies have compared standard 3D CRT with novel RT techniques in LARC treatment. A retrospective study comparing VMAT-SIB with 3D conformal therapy showed marginally improved pathological response rates (44% vs. 60%, p = 0.77) [

12]. Limitations of current research include small patient groups, often single-center designs, and heterogeneity in radiation doses and chemotherapy regimens. Furthermore, most published studies included simultaneous modifications to RT doses and chemotherapy regimens, making it difficult to isolate the therapeutic effects and safety of dose-escalated RT compared to the standard approach [

8].

The aim of our study was to compare the efficacy and toxicity of RT approaches using a total dose of 54 Gy in 25 fractions with VMAT and simultaneous integrated boost versus 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions with a 3D conformal technique and sequential boost.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at the Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia (IORS) from June 2020 to January 2022. The research included a group of 75 patients with LARC who were treated with nCRT using an escalated RT dose through the application of a SIB technique. The comparison group consisted of 62 patients treated with the standard nCRT regimen during the period from 2018 to 2019 at the IORS. Baseline characteristics of patients are presented in

Table 1.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the IORS (Approval No. 2211-01 from 11.06.2020.) and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade (Approval No. 1322/XII-17 from 03.12.2020.). All patients signed an informed consent.

2.1. Patient Selection

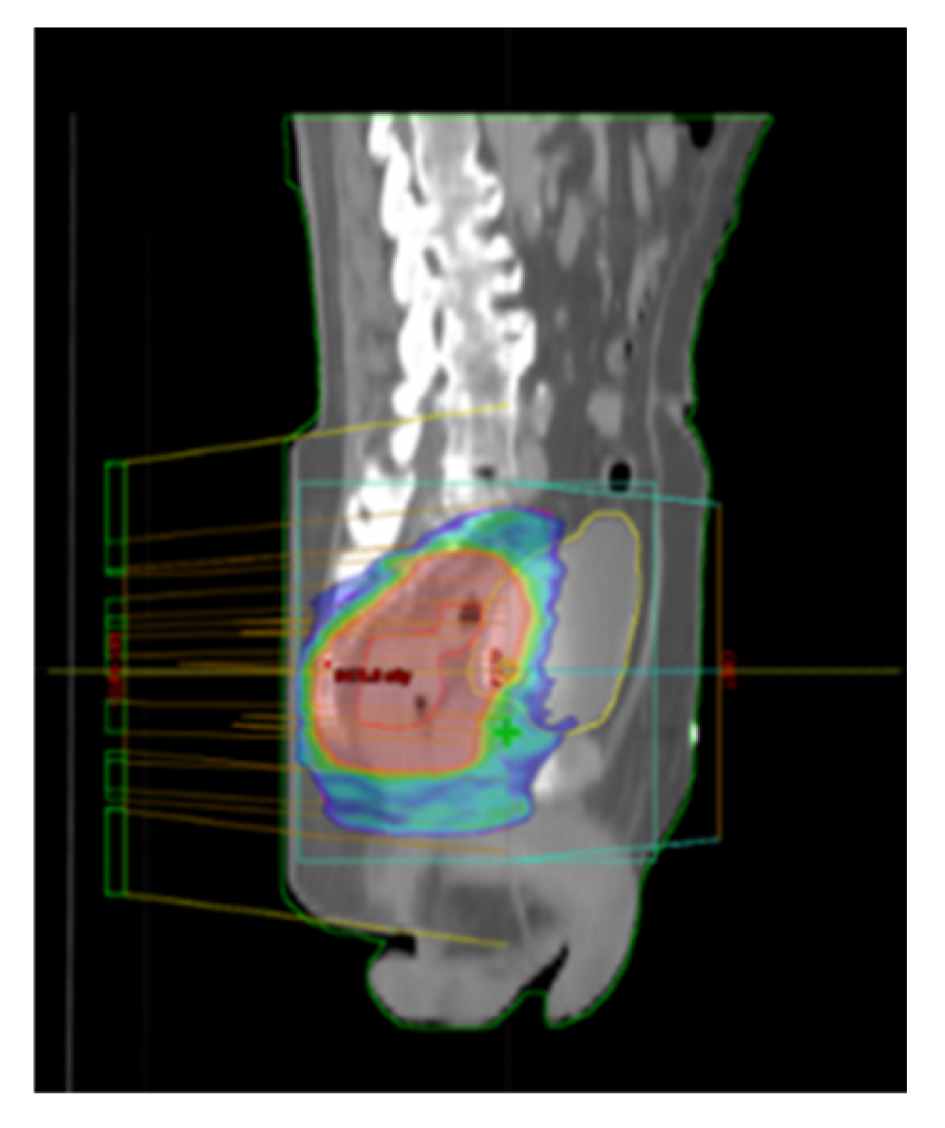

Patients included in the study were those with LARC who underwent nCRT using VMAT-SIB technique (

Figure 1), representing the prospective group treated with a novel RT technique. The total RT dose delivered was 54 Gy in 25 fractions, accompanied by concurrent CT following the 5-fluorouracil-leucovorin (5-FU-LV) protocol during the first and fifth weeks of RT. Inclusion criteria for the study were age over 18 years, clinically and histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of rectal adenocarcinoma, locally advanced disease stage (Stage II (T3/4N0M0) and III (T1-4N+M0) according to the UICC TNM classification, 8th edition) [

13], tumor distal pole located within 12 cm from the anal verge, patients undergoing initial specific oncological treatment for rectal cancer (excluding colostomy, which was performed only in cases of intraluminal bowel obstruction), ECOG performance status of 0, 1, or 2 [

14], adequate bone marrow function (leukocytes > 3.5 × 10⁹/L, neutrophils > 1.5 × 10⁹/L, platelets > 100 × 10⁹/L, hemoglobin > 80 g/L), satisfactory liver function (AST, ALT, bilirubin ≤ three times the upper limit of normal), creatinine clearance > 30 mL/min, understanding of the study protocol, and signed informed consent for participation. Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of another malignancy within the last five years, previous treatment for rectal cancer, prior pelvic RT, allergy to fluoropyrimidines, active inflammatory bowel disease, uncontrolled hypertension, pregnancy or breastfeeding, failure to sign the informed consent, or not meeting the inclusion criteria.

To compare treatment outcomes and toxicity between the approach involving an escalated RT dose with SIB and the standard nCRT, a group of patients treated with standard therapy was also observed. The standard RT approach involved treatment planning with 3D CRT. The total RT dose was 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions, with concurrent CT following the 5-FU-LV protocol during the first and fifth weeks of RT. The CT protocol was identical for both groups, with the difference between the two groups being the RT planning technique and the total delivered RT dose. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the group treated with the standard approach were identical to those for the group treated with the novel RT technique.

2.2. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy

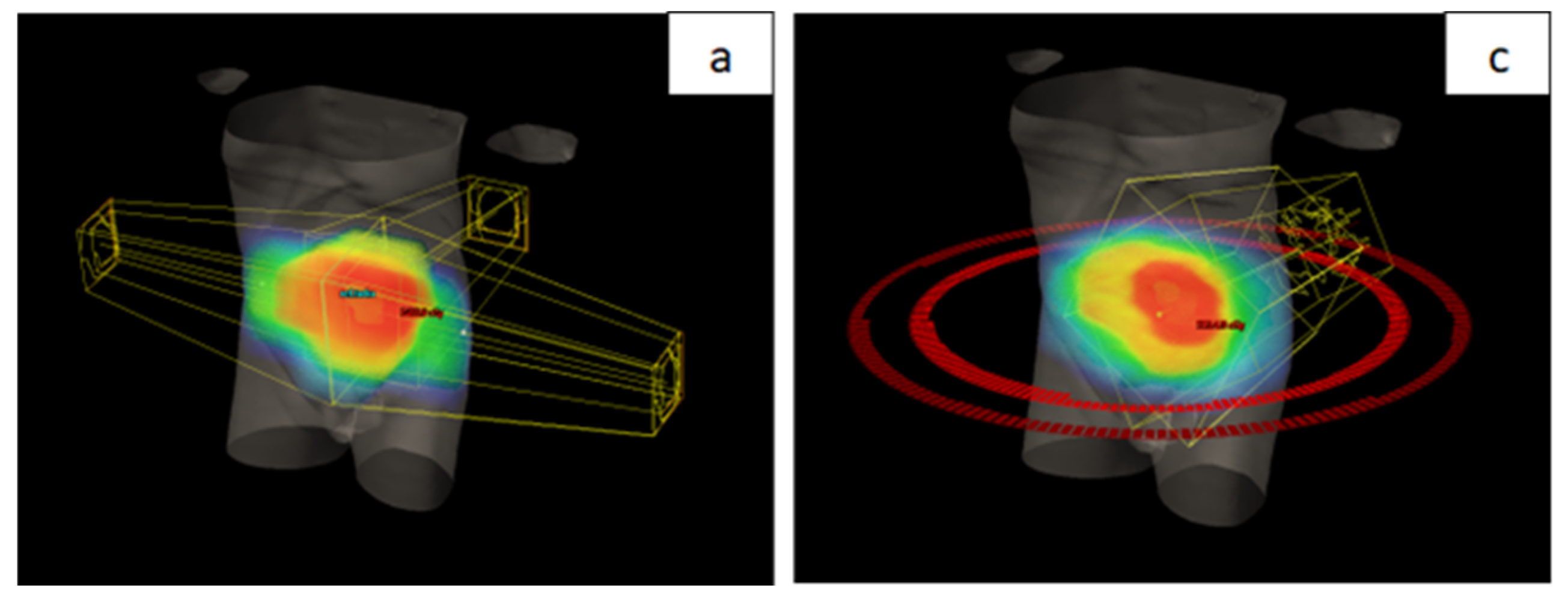

All patients were treated using a long-course RT regimen. Radiotherapy planning for the group treated with the novel RT technique was performed using VMAT-SIB (

Figure 2). Radiotherapy was delivered in 25 fractions over a period of five weeks. A tumor dose of 45 Gy (1.8 Gy per fraction) was applied to the mesorectal area and regional lymph nodes. A SIB was delivered to the area of macroscopic disease visible on imaging, with a 2 cm margin in all directions, to a total dose of 54 Gy (2.16 Gy per fraction). Concurrent CT included 5-FU at a dose of 350 mg/m² and LV at a dose of 25 mg/m². Chemotherapy was administered during the first and fifth weeks of RT.

In contrast to the group treated with the VMAT-SIB technique, where a higher RT dose was applied to the macroscopic disease volume, the group of patients treated with standard nCRT underwent a sequential boost technique. In this approach, after delivering a TD of 45 Gy in 25 fractions (1.8 Gy per fraction), an additional RT dose of 5.4 Gy in three fractions (1.8 Gy per fraction) was applied to the volume of macroscopic disease. Planning was performed using 3D CRT technique (

Figure 2) with three or four radiation fields.

2.3. Acute Treatment-Related Complications

During the course of neoadjuvant treatment, the occurrence of acute complications was recorded. Acute gastrointestinal, urinary, dermatological, and hematological toxicities were monitored. The grading of complications was performed according to version 5.0 of the NCI CTCAE – NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [

15].

2.4. Analyzed Treatment Outcomes

The analysis of surgical treatment characteristics included a comparison of the two study groups in terms of the percentage of patients who underwent surgery after completing nCRT, the timing of surgery following the conclusion of neoadjuvant treatment, the percentage of sphincter-preserving surgeries, and the status of resection margins. The groups were also compared regarding the histopathological characteristics of the tumor after surgery, including the grade of differentiation, presence and percentage of mucinous tumor component, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI), vascular invasion (VI), and perineural invasion (PNI).

Definitive pathological staging of the disease (T category, N category, and disease stage) was also assessed for both treatment approaches. Patients with a good response to neoadjuvant treatment were defined as those with T0, T1, or T2 in the postoperative T category, and those with localized disease (stages 0, 1, or 2) in the postoperative stage. Additionally, differences in the N category, including the total number of lymph nodes examined and the number of positive lymph nodes, were analyzed. The groups were compared using Dukes and Astler-Coller disease staging systems. In both groups, pathological response to treatment was assessed using the Tumor Regression Grade (TRG) classification by Mandard and the Rectal Cancer Regression Grade (RCRG) classification. Differences between the two groups in relation to these outcomes were analyzed. Some patients with clinical complete response (cCR) and initially distantly located tumors were managed non-surgically and enrolled in a strict follow-up program as part of the “watch and wait“ approach.

Reduction in T and N categories, as well as disease stage, was calculated based on initial parameters before starting neoadjuvant treatment and the definitive pathological stage of the disease. As measures of treatment efficacy, the two groups were compared in terms of reduction in the T category, reduction in the N category, reduction in either the T or N category, and reduction in disease stage.

2.5. Comparability of the Two Study Groups

As an initial step, a comparison was made between the group of patients treated with the new RT technique and the group treated with the standard approach. This comparison focused on patient characteristics (sex, age, ECOG performance status, body mass index (BMI)), tumor characteristics (localization, length of the affected intestinal segment, differentiation grade, T and N category, disease stage), and baseline tumor marker values (CEA, CA 19-9). By eliminating significant differences, conditions were established for a valid comparison and accurate interpretation of differences in recorded acute toxicity and treatment outcomes between the two study groups.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

For testing normal data distribution, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were used. Descriptive statistical methods (frequencies, percentages, mean, median, standard deviation (SD), and range) were applied to summarize the data. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05. To compare disease characteristics, treatment details, toxicities, and outcomes between the two patient groups, depending on data type and distribution the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Pearson’s chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact test were used. All statistical analyses were conducted using the R programming environment (version 3.3.2, released on October 31, 2016 – "Sincere Pumpkin Patch"; Copyright © 2016 The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Platform: x86_64-w64-mingw32/x64 (64-bit); downloaded on June 21, 2024).

3. Results

Comparing baseline characteristics of the two patient groups revealed no statistically significant differences in sex, age, or BMI (

Table 1). Both groups comprised patients in good general condition before treatment initiation (ECOG PS 0 or 1). A higher proportion of patients with ECOG PS 0 status was observed in the standard nCRT group. Regarding tumor characteristics, a significantly higher number of patients in the VMAT-SIB group had distally located rectal cancer (p < 0.01). No statistically significant differences were found in the initial tumor marker levels between the groups.

The comparison of acute toxicity observed in the two groups is presented in

Table 2. Urinary toxicity was significantly more frequent in the group of patients treated with the new RT technique compared to the group treated with the standard approach (p < 0.01). Other complications were similarly distributed between the two treatment approaches. Regarding the timing of acute toxicity onset, it occurred earlier in the group of patients treated with the new RT technique (p < 0.01).

In the group of patients treated with the novel RT technique, the average time to surgery after nCRT was 14.1 weeks, compared to 12.3 weeks in the group treated with the standard approach. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01,

Table 3). No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups regarding other surgical characteristics.

Comparison of tumor characteristics after surgical treatment revealed a significantly higher presence of perineural invasion in the group of patients treated with the standard approach (

Table 4).

In terms of the final pathohistological stage of disease, a significantly higher prevalence of lower T categories (T0, T1, T2; p < 0.01), N-negative categories (p < 0.05), and lower disease stages (I, II; p < 0.05) was observed in the group of patients treated with the new RT technique (

Table 5). A comparison of the number of examined lymph nodes revealed a statistically significant higher number of examined lymph nodes in the group of patients treated with the standard approach (p < 0.05).

A statistically significant difference in response was observed between the two treatment methods (

Table 6). A significantly higher representation of lower TRG and RCRG scores was found in the group of patients treated with the new radiation therapy technique. However, when comparing pathological complete response (TRG1) with all other categories, a positive trend was noted (p = 0.06), but without statistical significance.

A statistically significantly higher percentage of reduction in T category of disease, as well as disease stage (p < 0.01), was observed in the group of patients treated with the new radiation therapy technique (

Table 7).

4. Discussion

Optimal chemoradiotherapy approaches, the appropriate timing for response evaluation of LARC after nCRT, the ideal timing for surgery, and the criteria for selecting the best candidates for delaying surgery with intensive follow-up (“watch and wait approach”), remain unclear. In our previous studies, we explored potential predictors of response to nCRT based on clinical, radiological, and molecular [

16,

17,

18] The aim of our study was to compare a group of patients treated with a new radiation therapy technique and a group treated with standard CRT as part of neoadjuvant treatment for LARC, with the goal of evaluating the benefits of dose escalation using a SIB technique. In the standard treatment group, RT involved a sequential boost to the area of macroscopic disease, achieving a total dose of 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions using 3D CRT technique. In contrast, the new technique employed VMAT with SIB to the area of macroscopic disease, delivering a total dose of 54 Gy in 25 fractions. It is important to note that both groups received the same CT regimen. Before analyzing differences in toxicity and treatment outcomes, a comparison of the two groups was conducted based on their demographic and disease characteristics. As no significant differences were observed, comparability between the groups was ensured.

Our results showed a significantly higher number of non-hematological toxicities in the group of patients treated with the new radiation therapy technique. However, when toxicities were classified as low-grade (Grade 1 and 2) or high-grade (Grade 3), no significant differences were observed between the groups. Despite the use of the VMAT technique, known for its superior conformality and ability to spare surrounding organs at risk (OAR), toxicity rates were similar between the two groups of patients. This unexpected outcome may be attributed to several factors. First, the higher dose per fraction (2.16 Gy) and the greater total RT dose (54 Gy vs. 50.4 Gy) in the group of patients treated with the new technique could have offset the benefits of the more conformal approach regarding toxicity rates. Additionally, the prospective nature of the group treated with the new technique and stricter assessment of low-grade toxicities may have revealed adverse effects that were not documented in the group treated with the standard approach.

In a study conducted by Bae et al., comparing the use of a boost dose delivered sequentially with the 3D conformal technique and simultaneously with the IMRT technique, a significantly lower rate of urinary toxicity was observed in the IMRT-SIB group (patients with no toxicity or Grade 1 toxicity were compared to those with Grade 3 toxicity). However, no significant differences were found in other parameters [

19]. The difference compared to our study lies in the absence of an increased RT dose in the IMRT-SIB group, enabling a comparison of techniques without the confounding effect of the total RT dose.

Previous studies aiming to determine gastrointestinal toxicity rates also did not report reduced toxicity with the use of newer RT planning techniques. Gastrointestinal toxicity was observed in 52.5% of patients, which aligns with the findings of our study [

20]. In a study comparing conventional and VMAT-SIB techniques with a RT dose of 45 Gy and a boost to a total dose of 55 Gy, Grade 2 urinary toxicity was reported in 49% of patients, while Grade 2 diarrhea was reported in 42% of patients [

12]. Similar toxicity results were observed in a study conducted by Yang et al., which utilized the VMAT-SIB technique (50 Gy / 58.75 Gy in 25 fractions). Most patients experienced some form of acute toxicity, with a high-grade toxicity rate (Grade 3) of 7.7% [

8].

Further investigation into specific types of toxicities in our study revealed significant differences in urinary system toxicities, with a higher incidence of dysuria and frequent urination observed in the group of patients treated with the new RT technique. The predominant localization of tumors in the distal rectum in this group was associated with higher doses delivered to the urethra due to its close proximity to the mesorectum in this region.

Analysis of toxicity onset during treatment showed significantly earlier occurrence in the group of patients treated with the new RT technique. This difference may be attributed to the higher dose per fraction (2.16 Gy) delivered to the macroscopic tumor area. Notably, this analysis was not part of the data reported in the literature, making our findings a valuable contribution to understanding the timing of toxicity onset. These insights allow for the timely implementation of supportive measures to minimize adverse reactions.

Among the operated patients, sphincter-preserving surgery was achieved in 49 out of 63 patients, representing a higher percentage in the group treated with the new RT technique (77.8%) compared to 35 out of 56 patients in the standard approach (62.5%). However, statistical significance was not achieved. The lack of statistical significance could be attributed to the higher proportion of distally located tumors in the group treated with the new RT technique. Importantly, in 12 patients with distal tumor localization, achieving a cCR allowed for a non-operative management approach, resulting in sphincter preservation. Our findings align with existing literature, where a study utilizing the VMAT-SIB technique (45 Gy/55 Gy) reported a sphincter preservation rate of 88%. However, that study had a higher initial prevalence of stage II disease (42%) compared to our study [

12].

Comparison of the two patient groups revealed a statistically significant lower incidence of PNI in postoperative specimens from patients treated with the new RT technique (p < 0.01). This finding is important given the well-established negative prognostic impact of PNI in colorectal cancer. A meta-analysis of 58 studies involving 22,900 colorectal cancer patients demonstrated that PNI is associated with worse five-year overall survival (OS) (relative risk [RR], 2.09; 95% confidence interval, 1.68–2.61) and DFS (RR, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.66–3.31) [

21].

Analysis of definitive postoperative staging showed significantly higher rates of lower T categories (T0-2), negative nodal status (N0), and earlier stages (I+II) in the group treated with the new RT technique. Literature comparisons suggest that a change in RT technique alone, without dose escalation, does not result in significant improvements in these parameters [

19]. The observed improvements in our study likely reflect the combined effect of VMAT-SIB and increased RT dose.

Literature data indicate that pCR is associated with improved outcomes, regardless of initial clinical T and N categories, highlighting its importance in assessing LARC response to nCRT [

22]. In our study, among operated patients, pCR was achieved in 13 out of 63 patients (20.6%) treated with the new RT technique, compared to 5 out of 56 patients (8.9%) treated with the standard approach, showing a positive trend without statistical significance (p = 0.06). The lack of significance may be attributed to the 16% of patients in the new technique group who, due to cCR, did not undergo surgery. A study of 385 LARC patients treated with nCRT (50.4 Gy) followed by surgery after six weeks reported a pCR rate of 10.4% [

23]. Similarly, a study employing the VMAT-SIB technique with dose escalation, like ours, observed a pCR rate of 17% [

12], demonstrating the comparability of our results with the literature.

Tumor regression grade (TRG) is an important prognostic factor for assessing the risk of local recurrence, DFS, and OS in patients with LARC [

24]. When comparing individual TRG statuses, significantly better treatment responses were noted in the group treated with the new RT technique. For RCRG classification, statistical significance was observed both for individual categories and when comparing patients with favorable (RCRG1) versus poor responses (RCRG2-3). The divergence between classifications arises from the lack of standardized response alignment in the literature. Extended follow-up will help determine which classification has greater prognostic value in our patient cohort. Research indicates that ypN status and TRG status are independent predictors of OS and recurrence-free survival (RFS). A large study of 237 LARC patients treated with nCRT highlighted the importance of these predictors [

25]. In our comparison of two groups, a statistically significant lower percentage of N-negative cases was observed in the group treated with the new RT technique. Understanding the prognostic value of N status after neoadjuvant treatment can support an individualized approach to intensifying adjuvant chemotherapy in high-risk patient groups.

Guidelines recommend examining at least 12 lymph nodes for accurate staging of rectal cancer [

26]. However, when treatment begins with nCRT, achieving this benchmark can be challenging, as neoadjuvant therapy often reduces both the size and number of lymph nodes in the treated area. Our findings align with the literature, where intensified neoadjuvant treatment in the group treated with the new RT technique was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the number of isolated lymph nodes. A study comparing outcomes based on lymph node evaluation (fewer than 12 vs. 12 or more examined) found a higher percentage of pCR in patients with fewer than 12 isolated lymph nodes [

27]. The exact number of lymph nodes needed for staging in nCRT-treated patients remains undefined. Additional studies show that the number of isolated lymph nodes can vary with factors such as gender, age, initial disease stage, and the presence of LVI. Interestingly, a smaller number of isolated lymph nodes is often associated with better tumor response and improved prognosis [

28].

Data from the literature indicate that response to neoadjuvant therapy strongly correlates with long-term treatment outcomes. Following neoadjuvant treatment, disease downstaging is achieved in 50–60% of patients, while approximately 20% achieve pCR [

29,

30]. Unlike most studies that evaluate the pathological response to neoadjuvant treatment independently of ypTN staging, some approaches emphasize incorporating disease stage into the assessment. It has been demonstrated that the prognostic value of response is particularly significant in patients with ypIII disease. In this group, those with a good response to nCRT and a ypIII stage show survival rates comparable to those with ypII disease (five-year OS: 67% vs. 74%, p = 0.89). Conversely, in patients with a poor pathological response within the ypIII stage, survival outcomes resemble those of patients with stage IV disease (five-year OS: 27% vs. 18%, p = 0.09) [

31].

The study has certain limitations. The sample size is relatively small but meets the minimum criteria for patients with LARC, considering its prevalence and the population size in Serbia (95% confidence level) [

32]. In comparing the approach involving dose escalation with SIB using the VMAT technique against the standard treatment group, limitations include the retrospective nature of the comparator group, leading to incomplete data on toxicity and treatment outcomes. Additionally, the study's single-institution design may limit the generalizability of the findings. Other limitations may include potential selection bias due to the retrospective analysis and the lack of long-term follow-up data, which would provide a more comprehensive understanding of survival and recurrence outcomes. Future multi-institutional, prospective studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to confirm these findings and further validate the results.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential benefits of dose-escalated RT using the VMAT-SIB technique in the treatment of patients with LARC. Improved treatment outcomes, including higher rates of pCR and favorable TRG responses, were observed in the group of patients treated with the novel technique. Overall, this study supports the integration of dose-escalated VMAT-SIB into clinical practice as a feasible and effective approach for managing LARC, contributing to a more personalized and effective therapeutic strategy. However, further prospective, multi-center studies are needed to validate these results and assess long-term outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization (M.M., M.C., D.G., S.S.R., A.S.); Data curation (M.M., M.C., S.S.R.); Formal analysis (M.M., M.C., S.S.R., D.G., N.M., A.S.); Funding acquisition (A.T., P.P., M.C.); Investigation (M.M., M.C., S.S.R., A.S.); Methodology (M.M., M.C., A.S., D.G., S.S.R., N.M., A.T.); Project administration (M.M., M.C., R.J.); Resources (M.M., M.C., S.S.R., A.S., D.G., P.P., R.J.); Software (D.G., M.M., M.C.); Supervision (M.C., S.S.R., N.M., R.J., P.P., A.T.); Validation (M.M., M.C., A.S.); Visualization (M.C., M.M., S.S.R., D.G., A.S.); Writing – original draft (M.M,. S.S.R., A.S., D.G., R.J., N.M., S.R., P.P., A.T., M.C.); Writing – review & editing (M.M., S.S.R., A.S., D.G., R.J., N.M., S.R., P.P., A.T., M.C.). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Horizon Europe STEPUPIORS Project (HORIZON-WIDERA-2021-ACCESS-03, European Commission, Agreement No. 101079217) and the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Agreement No. 451-03-66/2024-03/200043).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia (Approval No. 2211-01 from 11 June 2020) and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade (Approval No. 1322/XII-17 from 3 December 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethics restrictions as their containing information could compromise the privacy of patients.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LARC |

locally advanced rectal cancer |

| nCRT |

neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy |

| RT |

radiotherapy |

| CT |

chemotherapy |

| pCR |

pathological complete regression |

| CR |

complete response |

| 3D CRT |

3D conformal radiation therapy |

| IMRT |

intensity-modulated radiotherapy |

| VMAT |

volumetric modulated arc therapy |

| TD |

tumor dose |

| DFS |

disease-free survival |

| SIB |

simultaneous integrated boost |

| IORS |

Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia |

| 5-FU-LV - |

5-fluorouracil-leucovorin |

| LVI |

lymphovascular invasion |

| VI |

vascular invasion |

| PNI |

perineural invasion |

| TRG |

Tumor Regression Grade |

| RCRG |

Rectal Cancer Regression Grade |

| cCR |

clinical complete response |

| SD |

standard deviation |

| BMI |

body mass index |

| OAR |

organs at risk |

| OS |

overall survival |

| RR |

relative risk |

| RFS |

recurrence-free survival |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glynne-Jones, R.; Wyrwicz, L.; Tiret, E.; Brown, G.; Rödel, C.; Cervantes, A.; Arnold, D. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up† Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, iv22–iv40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorcolo, L.; Rosman, A.S.; Restivo, A.; Pisano, M.; Nigri, G.R.; Fancellu, A.; Melis, M. Complete pathologic response after combined modality treatment for rectal cancer and long-term survival: a meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 2822–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macchia, G.; Gambacorta, M.A.; Masciocchi, C.; Chiloiro, G.; Mantello, G.; di Benedetto, M.; Lupattelli, M.; Palazzari, E.; Belgioia, L.; Bacigalupo, A.; et al. Time to surgery and pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal cancer: A population study on 2094 patients. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 4, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Valk, M.J.M.; Hilling, D.E.; Bastiaannet, E.; Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg, E.; Beets, G.L.; Figueiredo, N.L.; Habr-Gama, A.; Perez, R.O.; Renehan, A.G.; van de Velde, C.J.H. Long-term outcomes of clinical complete responders after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer in the International Watch & Wait Database (IWWD): an international multicentre registry study. Lancet (London, England) 2018, 391, 2537–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, T.; Bosset, J.-F.; Etienne, P.-L.; Rio, E.; François, É.; Mesgouez-Nebout, N.; Vendrely, V.; Artignan, X.; Bouché, O.; Gargot, D.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX and preoperative chemoradiotherapy for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (UNICANCER-PRODIGE 23): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. Oncol. 2021, 22, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoer, R.R.; Dijkstra, E.A.; van Etten, B.; Marijnen, C.A.M.; Putter, H.; Kranenbarg, E.M.-K.; Roodvoets, A.G.H.; Nagtegaal, I.D.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Blomqvist, L.K.; et al. Short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy before total mesorectal excision (TME) versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy, TME, and optional adjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer (RAPIDO): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. Oncol. 2021, 22, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jia, B.; Du, X.; Dai, G.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Zeng, M.; Wen, K.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Preoperative Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy With Simultaneous Integrated Boost for Locally Advanced Distal Rectal Cancer. Technol. cancer Res. & Treat. 2019, 18, 1533033818824367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, J.-P.; Barbet, N.; Schiappa, R.; Magné, N.; Martel, I.; Mineur, L.; Deberne, M.; Zilli, T.; Dhadda, A.; Myint, A.S. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with radiation dose escalation with contact x-ray brachytherapy boost or external beam radiotherapy boost for organ preservation in early cT2-cT3 rectal adenocarcinoma (OPERA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. lancet. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, M.E.; Tanaka, M.D.; Kensen, C.M.; van der Heide, U.A.; Marijnen, C.A.M.; Janssen, T.; Vijlbrief, T.; van Grevenstein, W.M.U.; Moons, L.M.G.; Koopman, M.; et al. Towards Response ADAptive Radiotherapy for organ preservation for intermediate-risk rectal cancer (preRADAR): protocol of a phase I dose-escalation trial. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e065010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardi, V.; Macchia, G.; Guido, A.; Giaccherini, L.; Deodato, F.; Farioli, A.; Cilla, S.; Compagnone, G.; Ardizzoni, A.; Cuicchi, D.; et al. Preoperative Chemoradiation With VMAT-SIB in Rectal Cancer: A Phase II Study. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 2017, 16, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, H.; Ishihara, S.; Nozawa, H.; Kawai, K.; Kiyomatsu, T.; Okuma, K.; Abe, O.; Watanabe, T.; Nakagawa, K. Comparison of volumetric-modulated arc therapy using simultaneous integrated boosts (SIB-VMAT) of 45 Gy/55 Gy in 25 fractions with conventional radiotherapy in preoperative chemoradiation for rectal cancers: a propensity score case-matched analysis. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, B.; Brierley, J.; Byrd, D.; Bosman, F.; Kehoe, S.; Kossary, C.; Piñeros, M.; Van Eycken, E.; Weir, H.K.; Gospodarowicz, M. The TNM classification of malignant tumours-towards common understanding and reasonable expectations. Lancet. Oncol. 2017, 18, 849–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oken, M.M.; Creech, R.H.; Tormey, D.C.; Horton, J.; Davis, T.E.; McFadden, E.T.; Carbone, P.P. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 1982, 5, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Health and Human Services Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.

- Marinkovic, M.; Stojanovic-Rundic, S.; Stanojevic, A.; Ostojic, M.; Gavrilovic, D.; Jankovic, R.; Maksimovic, N.; Stroggilos, R.; Zoidakis, J.; Castellví-Bel, S.; et al. Exploring novel genetic and hematological predictors of response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Front. Genet. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, A.; Samiotaki, M.; Lygirou, V.; Marinkovic, M.; Nikolic, V.; Stojanovic-Rundic, S.; Jankovic, R.; Vlahou, A.; Panayotou, G.; Fijneman, R.J.A.; et al. Data-Independent Acquisition Mass Spectrometry Analysis of FFPE Rectal Cancer Samples Offers In-Depth Proteomics Characterization of the Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2023.05–12.23289671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinkovic, M.; Stojanovic-Rundic, S.; Stanojevic, A.; Tomasevic, A.; Jankovic, R.; Zoidakis, J.; Castellví-Bel, S.; Fijneman, R.J.A.; Cavic, M.; Radulovic, M. Performance and Dimensionality of Pretreatment MRI Radiomics in Rectal Carcinoma Chemoradiotherapy Prediction. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, B.K.; Kang, M.K.; Kim, J.-C.; Kim, M.Y.; Choi, G.-S.; Kim, J.G.; Kang, B.W.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.Y. Simultaneous integrated boost intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy in preoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Radiat. Oncol. J. 2017, 35, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.S.; Moughan, J.; Garofalo, M.C.; Bendell, J.; Berger, A.C.; Oldenburg, N.B.E.; Anne, P.R.; Perera, F.; Lee, R.J.; Jabbour, S.K.; et al. NRG Oncology Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0822: A Phase 2 Study of Preoperative Chemoradiation Therapy Using Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy in Combination With Capecitabine and Oxaliplatin for Patients With Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2015, 93, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knijn, N.; Mogk, S.C.; Teerenstra, S.; Simmer, F.; Nagtegaal, I.D. Perineural Invasion is a Strong Prognostic Factor in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, M.; Nelemans, P.J.; Valentini, V.; Das, P.; Rödel, C.; Kuo, L.-J.; Calvo, F.A.; García-Aguilar, J.; Glynne-Jones, R.; Haustermans, K.; et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. Oncol. 2010, 11, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rödel, C.; Martus, P.; Papadoupolos, T.; Füzesi, L.; Klimpfinger, M.; Fietkau, R.; Liersch, T.; Hohenberger, W.; Raab, R.; Sauer, R.; et al. Prognostic significance of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 8688–8696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchio, F.M.; Valentini, V.; Minsky, B.D.; Padula, G.D.A.; Venkatraman, E.S.; Balducci, M.; Miccichè, F.; Ricci, R.; Morganti, A.G.; Gambacorta, M.A.; et al. The relationship of pathologic tumor regression grade (TRG) and outcomes after preoperative therapy in rectal cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2005, 62, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huebner, M.; Wolff, B.G.; Smyrk, T.C.; Aakre, J.; Larson, D.W. Partial pathologic response and nodal status as most significant prognostic factors for advanced rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy. World J. Surg. 2012, 36, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washington, M.K.; Berlin, J.; Branton, P.; Burgart, L.J.; Carter, D.K.; Fitzgibbons, P.L.; Halling, K.; Frankel, W.; Jessup, J.; Kakar, S.; et al. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with primary carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2009, 133, 1539–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurawalia, J.; Dev, K.; Nayak, S.P.; Kurpad, V.; Pandey, A. Less than 12 lymph nodes in the surgical specimen after neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy: an indicator of tumor regression in locally advanced rectal cancer? J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 7. [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, F.A.; Wagh, M.; Muralee, M.; Mathew, A.P.; Bharath, V.M.; Renu, S.; George, P.S. Prognostic Implications of Nodal Yield in Rectal Cancer After Neoadjuvant Therapy: Is Nodal Yield Still Relevant Post Neoadjuvant Therapy? Indian J. Surg. 2022, 84, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokas, E.; Ströbel, P.; Fietkau, R.; Ghadimi, M.; Liersch, T.; Grabenbauer, G.G.; Hartmann, A.; Kaufmann, M.; Sauer, R.; Graeven, U.; et al. Tumor Regression Grading After Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy as a Prognostic Factor and Individual-Level Surrogate for Disease-Free Survival in Rectal Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokas, E.; Liersch, T.; Fietkau, R.; Hohenberger, W.; Beissbarth, T.; Hess, C.; Becker, H.; Ghadimi, M.; Mrak, K.; Merkel, S.; et al. Tumor regression grading after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal carcinoma revisited: updated results of the CAO/ARO/AIO-94 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1554–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagkounis, G.; Thai, L.; Mace, A.G.; Wiland, H.; Pai, R.K.; Steele, S.R.; Church, J.M.; Kalady, M.F. Prognostic Implications of Pathological Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation in Pathologic Stage III Rectal Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flikkema, R.M.; Toledo-Pereyra, L.H. Sample size determination in medical and surgical research. J. Investig. Surg. Off. J. Acad. Surg. Res. 2012, 25, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).