1. Introduction

The primary treatments for localized prostate cancer include radical prostatectomy (RP), radiation therapy (RT), androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), and active surveillance. Treatment selection is based on disease risk stages, including clinicopathological factors [

1]. Historically, RP has been one of the most commonly used treatment modalities for localized prostate cancer [

2,

3]. However, the rates of biochemical recurrence (BCR) or locoregional recurrences (LR) after RP have been reported to vary considerably; specifically, wide ranges (15–50%), have been reported. Notably, intermediate- or high-risk prostate cancer patients have shown recurrence rates exceeding 40% [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Therefore, adjuvant RT (ART) and salvage RT (SRT) play essential roles in the management of BCR and LR.

There has been a longstanding discussion regarding the choice between ART and SRT after RP. Recently, three prospective clinical trials revealed similar results, which have had an enormous impact on this discussion. The RAVES, RADICALS-RT, and GETUG-17 trials demonstrated no significant differences between the SRT and ART groups in terms of biochemical progression-free survival or event-free survival [

10,

11,

12]. Furthermore, the RAVES trial showed that SRT was associated with significantly lower genitourinary toxicity than that of ART. Moreover, the RADICALS-RT trial demonstrated that ART increases the risk of urinary morbidity. Finally, in the GETUG-17 trial, ART increased the risk of genitourinary toxicity and erectile dysfunction. In summary, these trials suggest that SRT is similarly effective to ART and is associated with lower toxicity than ART. However, the factors that influence the effectiveness of SRT and the optimal timing of its administration in postoperative prostate cancer patients remain to be elucidated. Here, we evaluated the long-term outcomes, treatment-related toxicities, and predictive factors in postoperative prostate cancer patients who underwent SRT with intensity-modulated radiation therapy and image-guided radiation therapy (IMRT-IGRT) exclusively through TomoTherapy as a consistent and uniform modality.

2. Materials and Methods

Patients

Between April 2011 and March 2023, 71 patients with prostate cancer who underwent RP underwent IMRT-IGRT using TomoTherapy with a curative intent at our institution. All 71 patients underwent imaging studies, including those with BCR (N=63) and LR (N=8), tumors in the prostate bed, and pelvic lymph node metastases (N=4). BCR after RP was primarily defined by a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level threshold of 0.2 ng/mL and was also diagnosed considering individual clinical situations.

We retrospectively reviewed the patients’ medical records. All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis, computed tomography (CT) of the neck to the pelvis, bone scans, or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT, along with basic laboratory studies, including PSA levels before RT. The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) was assessed before RT. The disease characteristics of the 71 patients are summarized in

Table 1. This study was approved by the institutional review board (TGE02502-024), and informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to treatment.

Treatment

All patients received IMRT using TomoTherapy with a planned total dose of 66 Gy delivered in 33 fractions to the prostate bed. If patients had recurrent diseases in the prostate bed detected via imaging modalities (MRI), they received an additional dose of up to 76 Gy delivered in 38 fractions.

Organs at risk (OARs), including the bladder, rectum, and femoral head, were contoured according to the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) contouring guidelines [

13]. The clinical target volume (CTV) was defined as the prostate bed in accordance with the RTOG contouring atlas [

14], and the planning target volume (PTV) was defined as the CTV plus 5 mm margins. Gross tumor volume (GTV) was defined as any recurrent tumor observed on MRI. Treatment plans were generated using Precision and PlanningStation inverse planning software, utilizing superposition dose calculations. A field width of 2.5 cm and a pitch of 0.43 were applied, with the modulation factor primarily ranging from 1.5 to 2.0.

The patients consumed an appropriate amount of water to maintain an almost full bladder, and bladder volume was measured using BLADDERSCAN. Using the TomoTherapy system, daily megavolt CT (MVCT) image registration with treatment-planning CT is necessary for RT. Therefore, IGRT combined with MVCT was performed for each fraction.

Androgen Deprivation Therapy / Hormonal Therapy

Some patients were prescribed appropriate ADT, which included medications such as Bicalutamide, Degarelix, Goserelin acetate, Enzalutamide, and Leuprorelin acetate by urologists.

Evaluation criteria and statistical analysis

Responses were evaluated using PSA and physical examination approximately 3 months after completing treatment in the first 1–2 years of follow-up, and subsequently, every 6–12 months thereafter. When the PSA level increased continuously, imaging studies including MRI and CT, were performed in some cases. After SRT, BCR was defined as a continuous increase in PSA levels without evidence of recurrences in imaging studies. LR was defined as relapse in the prostate bed or pelvic lymph nodes. Distant metastasis (DM) was defined as metastasis outside the pelvic region.

Toxicities associated with radiation treatment were evaluated using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0 [

15]. Acute toxicities were defined as RT-related adverse events that occurred within 3 months of the completion of RT, whereas late toxicities were defined as those occurring thereafter. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free rate (PFR) were calculated using Kaplan–Meier curves. Differences between the curves were determined using the log-rank test. Prognostic factor analyses were performed using both univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models, using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (JMP 17.0.0, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Treatment

The median follow-up time from RP was 105 (range, 1–277) months, and that from SRT was 60 (range, 1–148) months in all patients. Patient and treatment characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. The patients underwent various types of RP. The median PSA maximum after surgery (mas PSA) was 0.61 (range, 0.13–22.2) ng/ml.

Reasons for SRT were as follows: BCR in 63 patients (88.7%) and LR in 8 patients (11.3%), which included tumors in the prostate bed. All 71 patients underwent SRT. Sixty-four (85.3%) patients were irradiated at the prostate bed, with 63 (88.7%) receiving 66 Gy in 33 fractions, and one patient (1.4%) receiving 68 Gy in 34 fractions. Seven (9.9%) patients were irradiated on the prostate bed and demonstrated recurrence at 76 Gy.

3.2. Androgen Deprivation Therapy / Hormonal Therapy

Thirty-eight (53.5%) patients received ADT during treatment. Details of the delivery phases are presented in

Table 2. Fifteen (21.1%) patients initiated ADT for post-RP recurrence, whereas 21 (29.6%) patients commenced for post-RT recurrence.

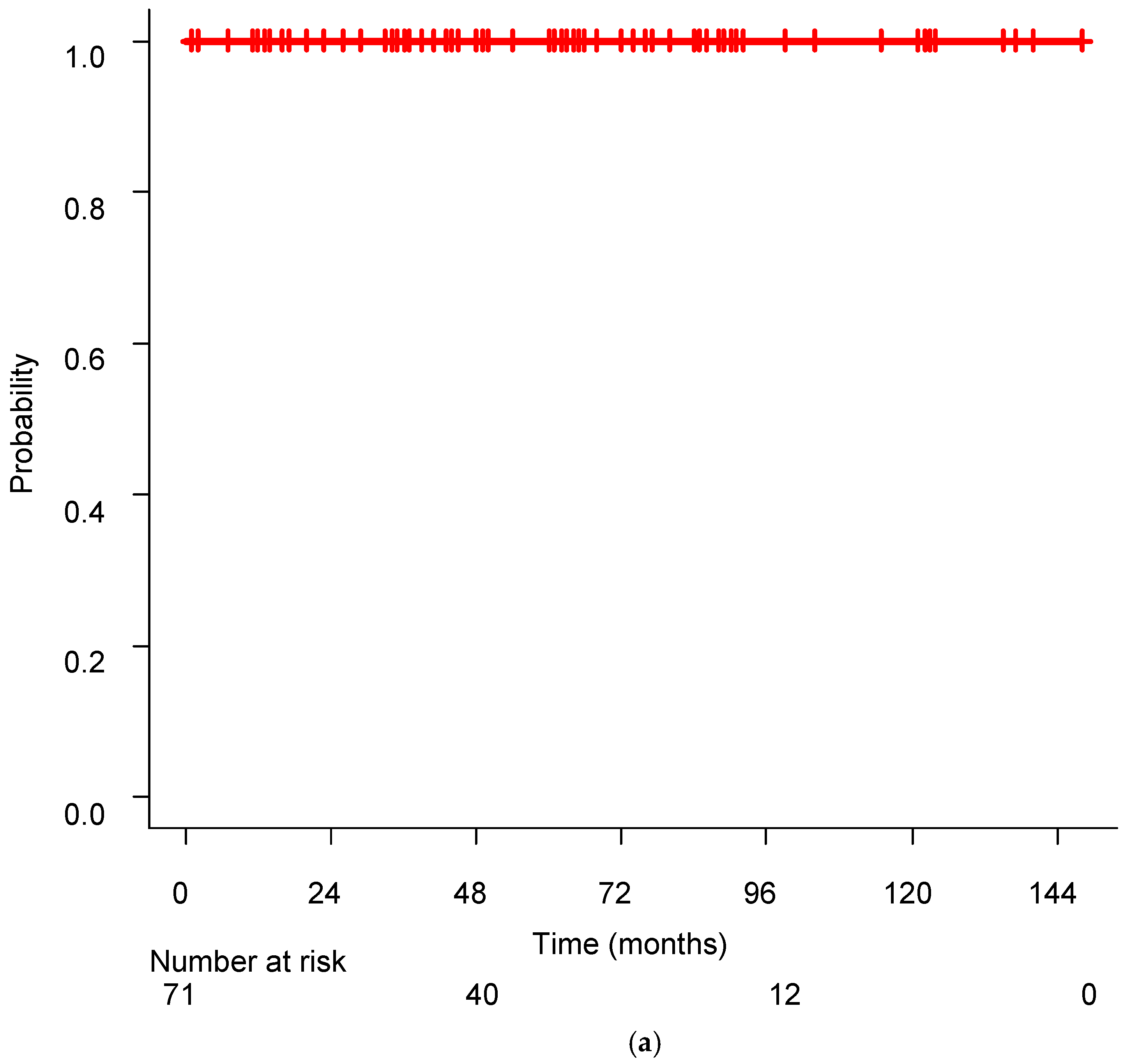

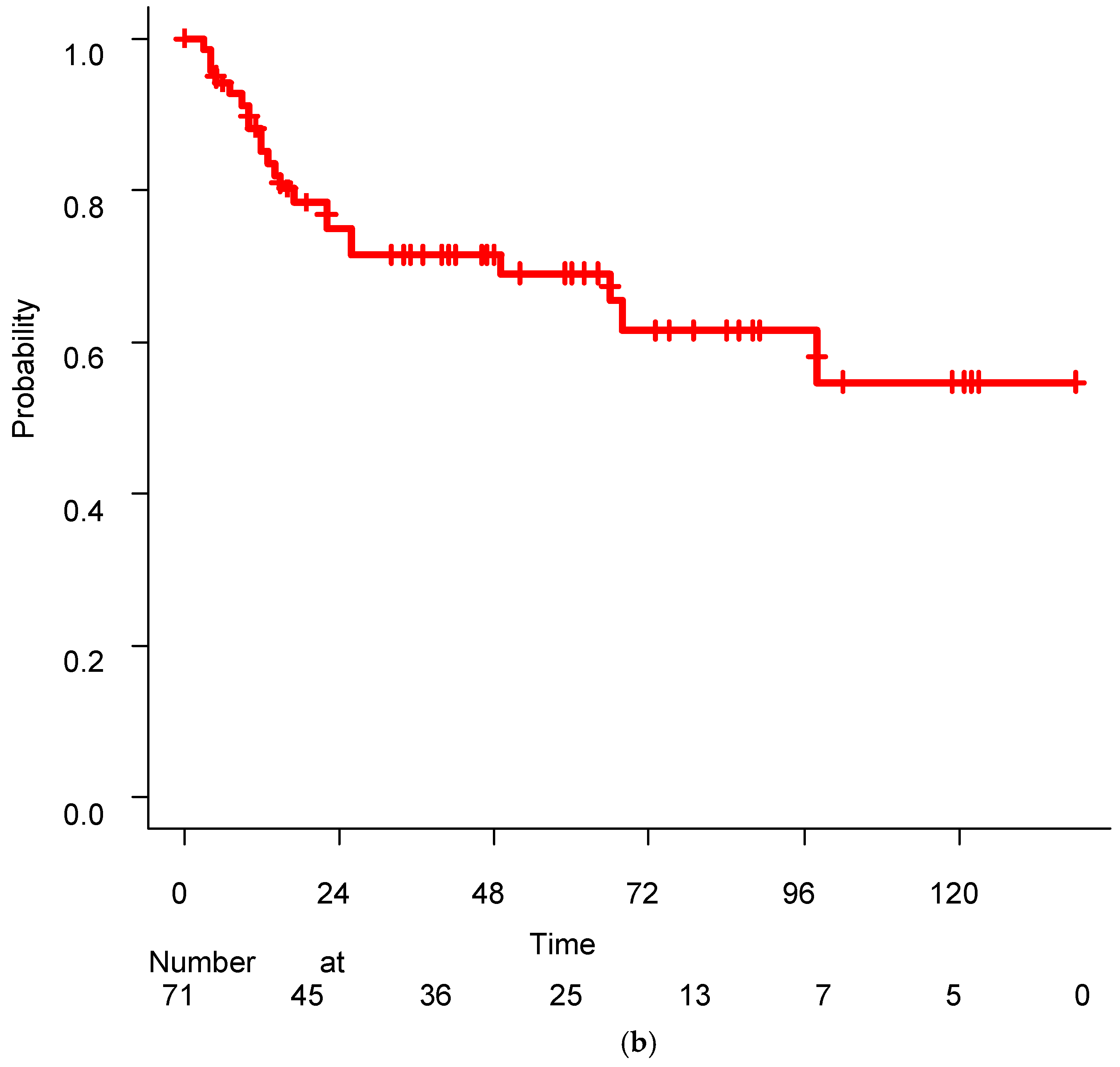

3.3. Disease Control

Figure 1 shows the Kaplan–Meier curves for PFR and OS. Twenty-two patients (31.0%) experienced disease progression, and the 5-year and 10-year PFR were 69.05% and 54.73%, respectively. The median control rate was not achieved during the observation period. Twenty-one of the 22 patients with recurrence after SRT received ADT, and their disease was successfully controlled with this treatment. All patients were alive at the final evaluation, resulting in a 10-year survival rate of 100%.

Twenty of the 22 patients who experienced disease progression after SRT underwent imaging studies, including CT. The median PSA at the time of recurrence after SRT was 2.48 (range: 0.31–10.77) ng/mL. Among these, one patient developed LR, specifically pelvic lymph node recurrence. Additionally, one patient developed DM with multiple bone metastases. No instances of disease relapse were observed in the irradiated field.

Patients who underwent LR after RP (N=8) were scheduled to receive a prescribed dose > 70 Gy. However, seven patients received ≥70 Gy, and one received only 66 Gy due to individual reasons. The patient who received only 66 Gy of radiation subsequently developed disease progression after SRT. Among the population receiving ≥70 Gy (N=7), two patients experienced disease progression, with one developing distant metastasis, resulting in a 5-year PFR of 85.71%.

No significant difference was observed between these groups of patients (N=8, ≥70 Gy vs. 66 Gy, p=0.1551 by the log-rank test). However, the median disease control months were 86 months in the ≥70 Gy and 15 months in 66 Gy. Additionally, among all 71 patients in PFS, no significant difference was observed between those who received ≥70 Gy and < 70 Gy (p=0.7437 by the log-rank test). Similarly, no significant differences were observed between patients with LR after RP (N=8) and those with BCR after RP (N=63) (p=0.8435, log-rank test).

3.4. Analysis of Prognostic Factors

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the factors associated with the PFR are summarized in

Table 3. In univariate analysis, two factors were found to be significantly correlated with worse PFR, including higher mas PSA (>0.7 ng/mL) and higher ECOG performance status score (PS) (mas PSA>0.7, hazard ratio (HR) 2.647, 95% confidence interval (95%CI) 1.108–6.324, p=0.00246). Maximum PSA levels were analyzed in 0.1 ng/mL increments, ranging from 0.2–1.0 ng/mL. No significant findings were observed except at 0.7 ng/ml. Additionally, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis determined the cutoff value for maximum PSA to be 0.78 (Youden index; area under the curve: 0.659; 95% CI: 0.522–0.796). Therefore, a mass PSA >0.7 ng/mL was adopted as the cutoff value for this analysis. Meanwhile, in univariate analysis, PS showed HR 7.475, 95%CI 1.570–35.580, p=0.04).

In multivariate analysis, factors such as mass PSA >0.7 ng/mL were found to be significantly associated with inferior PFR (HR 2.70, 95% CI 1.111–6.588, p=0.0284).

5. Toxicities/Adverse Event

Regarding acute toxicity, only one patient (1.4%) developed grade 1 gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity, and no instances of GI or genitourinary (GU) toxicity exceeding grade 2 were noted.

In terms of late toxicity, no instances of ≥ grade 3 toxicity were noted. Eight (11.8%) patients experienced late grade 2 GU toxicity, and one (1.4%) developed late grade 2 GI toxicity. No significant difference was noted between IPSS values just before RT and the occurrence of ≥ grade 2 GU toxicity (p=0.5805). A significant association was observed between anticoagulant use and the occurrence of grade 2 GI toxicity (p=0.0016).

4. Discussion

The current study comprehensively analyzed the long-term outcomes, treatment-related toxicities, and predictive factors in postoperative prostate cancer patients who underwent SRT with IMRT-IGRT using TomoTherapy. The evaluation of prostate cancer treatment outcomes requires long-term observation because of the prolonged progression of the disease. Previous retrospective studies typically included various RT modalities, such as three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy and IMRT, depending on the study period [

16]. Some studies have used TomoTherapy for postoperative prostate cancer, but one of them was a planning study [

17], and the other used moderate postoperative hypofractionated RT [

18]. Therefore, in our study, all patients received RT using TomoTherapy with IGRT as a uniform modality, which is a strength of our study.

Tumor Control and Survival

Recently, several clinical trials on SRT have reported results superior to those of our study. In the RAVES trial, 5-year freedom from biochemical progression was 87% in the salvage radiotherapy group. Moreover, in the RADICALS-RT trial, 5-year biochemical progression-free survival was 88% for those in the salvage radiotherapy group. In the GETUG-17 trial, 5-year event-free survival was 90% in the salvage radiotherapy group [

10,

11,

12]. In a retrospective study, Cuccia et al. reported that 2- and 3-year biochemical recurrence-free survivals were 88% and 73% for the entire population using moderate postoperative hypofractionated radiation therapy delivered by Helical TomoTherapy, respectively [

18]. Fukuda et al. reported that BCR occurred in 38%, the locoregional recurrence rate was 4%, and the distant metastasis rate was 6% in the SRT group using three-dimensional radiation therapy [

16]. Seyedin et al. analyzed postoperative prostate cancer patients with positive margins without ADT and reported the 5- and 8-year biochemical relapse-free survival rates both at 63% [

19]. In our study, the 5-year and 10-year PFR was 69.05% and 54.73%, respectively. Direct comparisons with previous studies may be challenging due to variations in treatment modalities, radiation fields that included the pelvic area, the timing and duration of ADT, and patient populations [

10,

11,

12,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Prognostic Factors / PSA Cutoff

Recently, PSA levels just before SRT for postoperative prostate cancer have been suggested to be critical factors in treatment outcomes [

20,

21,

22]. Tilki et al. reported that patients who received SRT at a PSA level >0.25 ng/mL had an increased all-cause mortality risk [

20]. In addition, Vogel et al. suggested that patients who were initiated early SRT at PSA levels <0.3 ng/mL showed superior e biochemical relapse-free survival, with a 68% reduced risk of biochemical relapse [

22]. Furthermore, Song et al. reported that pre-RT PSA level ≥1.0 ng/mL was one of the significant predictive factors for biochemical recurrence [

22].

As shown, PSA levels just before RT have the potential to be predictive factors for treatment outcomes in postoperative prostate cancer. However, the specific predictive range varies across studies, and the definitive cutoff value remains undetermined. Our results suggest that maximum PSA levels just before SRT > 0.7 ng/mL) were associated with unfavorable PFR and indicated that the cutoff value of pre-RT PSA was higher than that reported in previous studies. This disparity may be attributed to the inclusion of patients with image-detectable recurrent tumors in the prostate bed, who exhibited higher mas PSA levels (median 1.425, range 0.25–7.57), comparing median mas PSA of 0.61 (0.13–22.2) in the overall study population. Despite this difference, the PFR in our study remained similar to that in previous findings. This might indicate that IGRT-IMRT using TomoTherapy is particularly effective for patients with higher PSA levels, in contrast to previous reports. Patients with image-detectable recurrent tumors in the prostate bed met this criterion in our study. No significant difference was observed in PFR between patients who received ≥70 Gy and those who did not. However, among patients who received ≥70 Gy, the 5-year PFR was 85.71%. This result may suggest that prescribing ≥70 Gy may have the potential to control relapses in patients with image-detectable recurrent tumors in the prostate bed. Notably, the number of patients in this subgroup was minimal, indicating the need for further studies to confirm these findings.

Toxicity

Previous studies reported varying results regarding therapy-related toxicities. Using IGRT-IMRT, S. K. NATH et al. reported that late grade 2 GI and GU were observed in 2% and 16%, respectively, with only one patient (2%) experiencing Grade > 3 [

23]. C.H. Flores-Balcázar et al. compared GI and GU, including grades 1 to 2, and toxicities between IMRT and 3D-CRT, reporting late GI and GU toxicities for IMRT and 3D-CRT treatment were 1.9% and 6.7% for GI and 7.5% and 16.6% for GU, respectively. Moreover, IMRT was associated with a lower rate of complications [

24]. More recently, Hasterok et al. reported toxicities associated with IMRT, VMAT, and TomoTherapy, or a combination of these treatments with a median RT dose of 70 Gy. In their study, late GI and GU toxicities of higher grade 2 were 11.2% and 21.3%, respectively. Furthermore, five patients developed grade 4 toxicities [

25].

In this study, the toxicity profile was favorable, with only a small percentage of patients developing late grade 2 GI and GU toxicities (GI≥G2 1.4%, GU≥G2 11.3%) compared to that of previous reports. Additionally, no adverse events exceeding grade 3 were reported. This underscores the safety and tolerability of the approach.

Limitations

This study has several limitations, including its retrospective design, single institutional report, and variability in the phases in which patients received ADT, depending on the individual urologist. Moreover, there is variability in surgical methods, including classic RP, radical perineal prostatectomy, laparoscopic RP, and robot-assisted RP.

5. Conclusions

Our findings demonstrated a comparable PFR at 5-year (69.05%) and 10-year (54.73%) intervals and low toxicity rates compared with previous studies. Additionally, associations were found between a worse PFR and a maximum PSA greater than 0.7 ng/ml. However, further studies are required to conclusively determine its efficacy and safety. Nevertheless, IMRT-IGRT combined with TomoTherapy has emerged as one of the promising SRT option for patients with biochemical prostate cancer failure after radical prostatectomy.

Author Contributions

Yuki Mukai: Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation, Motoko Omura: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Yumiko Minagawa: Data curation, Writing- Reviewing, Misato Mase: Data curation, Investigation, Yuta Nishikawa: Data curation, Investigation, Ichiro Miura: Investigation, Supervision, Masaharu Hata: Supervision.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Shonan Kamakura General Hospital (TGE02502-024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found within the Electronic Health Record of the Department of Radiation Oncology, in Shonan Kamakura General Hospital and in the correspondent institutional prospectively maintained database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RP |

Radical prostatectomy |

| RT |

Radiation therapy |

| ADT |

Androgen deprivation therapy |

| BCR |

Biochemical recurrence |

| ART |

Adjuvant radiation therapy |

| SRT |

Salvage radiation therapy |

| IMRT |

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy |

| IGRT |

Image-guided radiation therapy |

| LR |

Locoregional recurrence |

| PSA |

Prostate-specific antigen |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| PET |

Positron emission tomography |

| IPSS |

International prostate symptom score |

| OARs |

Organ at risks |

| RTOG |

Radiation Therapy Oncology Group |

| CTV |

Clinical target volume |

| PTV |

Planning target volume |

| GTV |

Gross tumor volume |

| MVCT |

Megavolt-CT |

| DM |

Distant metastasis |

| OS |

Overall survival |

| BCRR |

Biochemical recurrence rate |

| LCR |

Locoregional control rate |

| DMFR |

Distant metastasis-free rate |

| PFR |

Progression-free rate |

| PS |

ECOG performance status score |

| HR |

Hazard ratio |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| ROC |

receiver operating characteristic |

| GI |

Gastrointestinal |

| GU |

Genitourinary |

References

- N Mottet et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer—2020 Update. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent, Eur Urol. 2021 Feb;79(2):243-262. Epub 2020 Nov 7. [CrossRef]

- K Vatne et al. Pre- and postprostatectomy variables associated with pelvic post-operative radiotherapy in prostate cancer patients: a national registry-based study. Acta Oncol. 2017 Oct;56(10):1295-1301. [CrossRef]

- MG Parry et al. Impact of cancer service centralisation on the radical treatment of men with high-risk and locally advanced prostate cancer: A national cross-sectional analysis in England, Int J Cancer. 2019 Jul 1; 145(1): 40–48. [CrossRef]

- TM Pisansky et al. Adjuvant and salvage radiation therapy after prostatectomy: ASTRO/AUA guideline amendment, executive summary 2018. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019 Jul-Aug;9(4):208-213. [CrossRef]

- J Fichtner et al. The management of prostate cancer in patients with a rising prostate-specific antigen level. BJU Int. 2000 Jul;86(2):181-90.

- AJ Stephenson et al. Postoperative radiation therapy for pathologically advanced prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol . 2012 Mar;61(3):443-51. [CrossRef]

- AJ Stephenson et al. Preoperative nomogram predicting the 10-year probability of prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006 May 17;98(10):715-7. [CrossRef]

- P Carroll et al. Rising PSA after a radical treatment. Eur Urol. 2001:40 Suppl 2:9-16. [CrossRef]

- NG Zaorsky et al. Salvage therapy for prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Nat Rev Urol. 2021 Nov;18(11):643-668. [CrossRef]

- A Kneebone et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy versus early salvage radiotherapy following radical prostatectomy (TROG 08.03/ANZUP RAVES): a randomised, controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority trial, Lancet Oncol. 2020 Oct;21(10):1331-1340. [CrossRef]

- CC Parker et al. Timing of radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy (RADICALS-RT): a randomised, controlled phase 3 trial, Lancet. 2020 Oct 31;396(10260):1413-1421. [CrossRef]

- P Sargos et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy versus early salvage radiotherapy plus short-term androgen deprivation therapy in men with localised prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy(GETUG-AFU 17): a randomised, phase 3 trial, Lancet Oncol. 2020 Oct;21(10):1341-1352 . [CrossRef]

- Male RTOG Normal Pelvis. https://www.nrgoncology.org/About-Us/Center-for-Innovation-in-Radiation-Oncology/Male-RTOG-Normal-Pelvis, accessed 12/8/2024.

- Hiram A Gay, H Joseph Barthold, Elizabeth O'Meara et al, Pelvic Normal Tissue Contouring Guidelines for Radiation Therapy: A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Consensus Panel Atlas, Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012 Jul 1;83(3):e353-62. [CrossRef]

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_5x7.pdf, accessed 12/8/2024.

- I Fukuda et al, Radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer: clinical outcomes and factors influencing biochemical recurrence, Ir J Med Sci. 2023 Dec;192(6):2663-2671. [CrossRef]

- S Malone et al, Postoperative radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a comparison of four consensus guidelines and dosimetric evaluation of 3D-CRT versus tomotherapy IMRT, Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012 Nov 1;84(3):725-32. [CrossRef]

- F Cuccia et al, Hypofractionated postoperative helical tomotherapy in prostate cancer: a mono-institutional report of toxicity and clinical outcomes, Cancer Manag Res. 2018; 10: 5053–5060. [CrossRef]

- SN Seyedin et al. A Recursive Partitioning Analysis Demonstrating Risk Subsets for 8-Year Biochemical Relapse After Margin-Positive Radical Prostatectomy Without Adjuvant Hormone or Radiation Therapy, Adv Radiat Oncol. 2021 Aug 14;6(6):100778. [CrossRef]

- D Tilki et al, Prostate-Specific Antigen Level at the Time of Salvage Therapy After Radical Prostatectomy for Prostate Cancer and the Risk of Death, J Clin Oncol. 2023 May 1;41(13):2428-2435.

- MME Vogel et al. Adjuvant versus early salvage radiotherapy: outcome of patients with prostate cancer treated with postoperative radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy, Radiat Oncol. 2019; 14: 198. [CrossRef]

- Song W, et al., Prognostic factors after salvage radiotherapy alone in patients with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Int J Urol. 2016;23(1):56–61 . [CrossRef]

- SK Nath et al. Toxicity analysis of postoperative image-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer, Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 Oct 1;78(2):435-41 . [CrossRef]

- CH Flores-Balcázar et al. Transitioning from conformal radiotherapy to intensity-modulated radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy: Clinical benefit, oncologic outcomes and incidence of gastrointestinal and urinary toxicities, Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2020 Jul-Aug;25(4):568-573. [CrossRef]

- M Hasterok at al. Rectum and Bladder Toxicity in Postoperative Prostate Bed Irradiation: Dose-Volume Parameters Analysis, Cancers (Basel) . 2023 Nov 9;15(22):5334.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).