1. Introduction

The study and comprehension of placental development, function and adaptation to different environmental conditions are essential in the field of reproductive physiology. Placenta is a transitory organ that provides an interface for nutrient and gas exchange between the fetus and the dam. It is also an endocrine organ that secretes key hormones for pregnancy maintenance, such as progesterone and placental lactogen [

1,

2]. Given its central role in the success of mammalian reproduction, collecting high quality samples for the assessment of this organ is of great interest for the research community in this field. However, this is also challenging, as placental tissue rapidly degrades after parturition [

3], and collecting samples can be difficult when animal experiments are conducted under field conditions.

For ruminant reproductive physiology, the study of how the placenta responds to different environmental or nutrition managements is of high relevance in livestock raised under extensive conditions, because understanding this has a direct impact on animal production [

4]. Additionally, small ruminants such as sheep are valuable models for translational research [

5,

6], even though there are placental differences between species. Among the different laboratory techniques for placental assessment, transcriptomics appears as a powerful tool that provides valuable information regarding gene expression, allowing for rapid advances in the understanding of placental physiology [

7].

Most of the literature indicates that placental samples must be collected and preserved as soon as possible to avoid RNA degradation, because this tissue is enriched in RNase activity [

8,

9], RNA is labile outside the organism, and its integrity largely determines the precision of transcriptomic analysis [

3,

10]. Hence, the sampling techniques for placental tissues in ruminants -and particularly small ruminants such as sheep- are primarily postmortem via euthanasia [

11], or through surgical extraction of placentomes [

12]. This is due to the unknown impact that collecting a sample from a naturally delivered placenta may have on RNA quantity and quality, and the risk of contamination with feces or urine that would likely occur under field conditions.

An alternative collection method could be tissue preservation immediately postpartum after natural placental expulsion, avoiding environmental contamination of the sample. However, placental delivery timing in sheep is variable and may take up to 6 hours, [

13], and the RNA integrity could be affected within that window of time. To our knowledge, there is a lack of literature regarding RNA quantity and quality parameters, and also for different sample preservation methods for naturally delivered sheep placenta. The gold standard preservation method is freezing in liquid nitrogen (snap frozen or flash frozen)[

14]. However, the appearance of RNA preservation solutions, such as RNA

later®, provide a preserving method that can be used to collect samples at room temperature, which may be more convenient when working in field conditions. Currently, there is no information regarding which of these two preservation alternatives may give better results when working with naturally expelled ovine placenta. Hence our aims were to evaluate if it is possible to extract RNA from naturally delivered placentas in sheep, and to compare the effect of two different preservation methods (snap frozen versus RNA preservation solution) on placental RNA quantity and quality.

We aim to evaluate a sample collection approach that reaches a balance between quality research results and the application of the refinement principle of the three Rs approach (reduction, refinement, and replacement) for animals used in research. This principle refers to reducing the invasiveness of procedures applied to animals as much as possible without severely affecting research results [

15,

16].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

The study was carried out at the Regional Research Center INIA Kampenaike, located in Magallanes, Chile (Lat 52° 36’; Lon 70° 56’). A total of 55 Corriedale sheep of similar age (3 years old), weight (54.05 ± 0.78 kg), body condition score (2.39 ± 0.09 in a 1 to 5 scale) were selected for the study. Ewes were divided into five groups for estrus synchronization using two injections of prostaglandin F2α (Ciclase®, Zoetis, Parsippany-Troy Hills, NJ) administered 12 days apart. The synchronization protocol was applied to each of the five groups, leaving 1 day between each group. The purpose of this was to alleviate the expected number of parturitions per day to facilitate the post-delivery placental sampling. Ewes were artificially inseminated and pregnancy diagnosis via ultrasound scan was performed at gestational day (GD) 70. Dams carrying singleton pregnancies (n=27) were selected for the present study. Animals were maintained under natural grazing conditions during all pregnancy (CP 6.1%, ME 1.6 Mcal/Kg, stocking rate 0.9 ewes/hectare; DM 525 kg/hectare). On GD 140, animals were moved into 1.2 m2 individual pens inside a barn. Sheep remained there until 1 day after parturition to monitor the health status of the dam and its lamb. The pens allowed the animals to see each other. The barn had a slotted floor and was covered with a washable and permeable net, minimizing urine or other fluid contamination. Each animal received ad libitum water and was fed with hay and concentrate twice a day according to their nutritional requirements. The floor of each pen was cleaned daily to avoid accumulation of feces or hay. It was also cleaned once an animal showed early signs of parturition. Animals were under 24/7 surveillance by trained personnel from GD 140 until 1 day after parturition.

2.2. Placental Sampling and Preservation

Placentas were collected by trained personnel immediately after delivery. It was retrieved when still hanging from the vulva of the ewe, only if it could be extracted by minimal traction. In a few cases, the placenta was collected from the floor immediately after being delivered. Time between parturition and placental delivery was recorded for each animal. The entire placenta was collected into a clean bucket and carried to a sampling station mounted within the barn. After weighing, the placenta was extended in a clean tray and 5 cotyledons placed around the umbilicus insertion were selected for sampling. Samples from each placenta were preserved using the following methods: 1. Snap Frozen (SF, n=27): A small piece of each cotyledon was collected, all pieces were chopped and mixed to get a combined sample. The tissue was placed into a 1.5 ml cryogenic tube and immediately frozen into liquid nitrogen. Samples were stored in liquid nitrogen for 2 weeks, and then kept at -80 °C until further processing. 2. RNAlater® (LTR, n=27): A small piece was cut from the same cotyledons as in the SF sample. The five pieces (0.3 cm3 approximately) were placed into a 5 ml RNase free tube with 4 ml of RNAlater® (#AM721, Thermofisher, Waltham MA). Tubes were maintained at room temperature for 2 weeks, then at 4 °C for a month, and stored at -20 °C until further processing. RNAlater® was not removed from the samples before freezing. The preservation protocols used in SF and LTR samples were adjusted to the working possibilities of our field conditions, which did not provide access to refrigerators or freezers during the lambing period (2 weeks).

2.3. RNA Extraction

Approximately a month after collection, samples were shipped for RNA extraction and analysis from the Regional Research Center INIA Kampenaike in Punta Arenas, Magallanes Region, Chile to the Applied Morphology Laboratory, Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias of Universidad Austral de Chile (UACh), Valdivia, Los Ríos Region, Chile. The SF and LTR samples were shipped overnight on dry ice and ice respectively. Upon arrival, SF and LTR samples were immediately stored at -80 °C and -20 °C respectively. Samples from both preservation methods were processed in parallel and using the same protocol for RNA extraction. Briefly, all surfaces and implements were cleaned with anti-RNAse solution (RNaseZap® #AM9722, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). A portion of approximately 50 to 100 mg of tissue was collected and processed using an RNA extraction kit according to the fabricant recommendations and adding the optional treatment with DNases included in the kit (Quick-RNA mini prep® #R1054, Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). All samples were eluted in 50 uL of ultrapure RNAse free water.

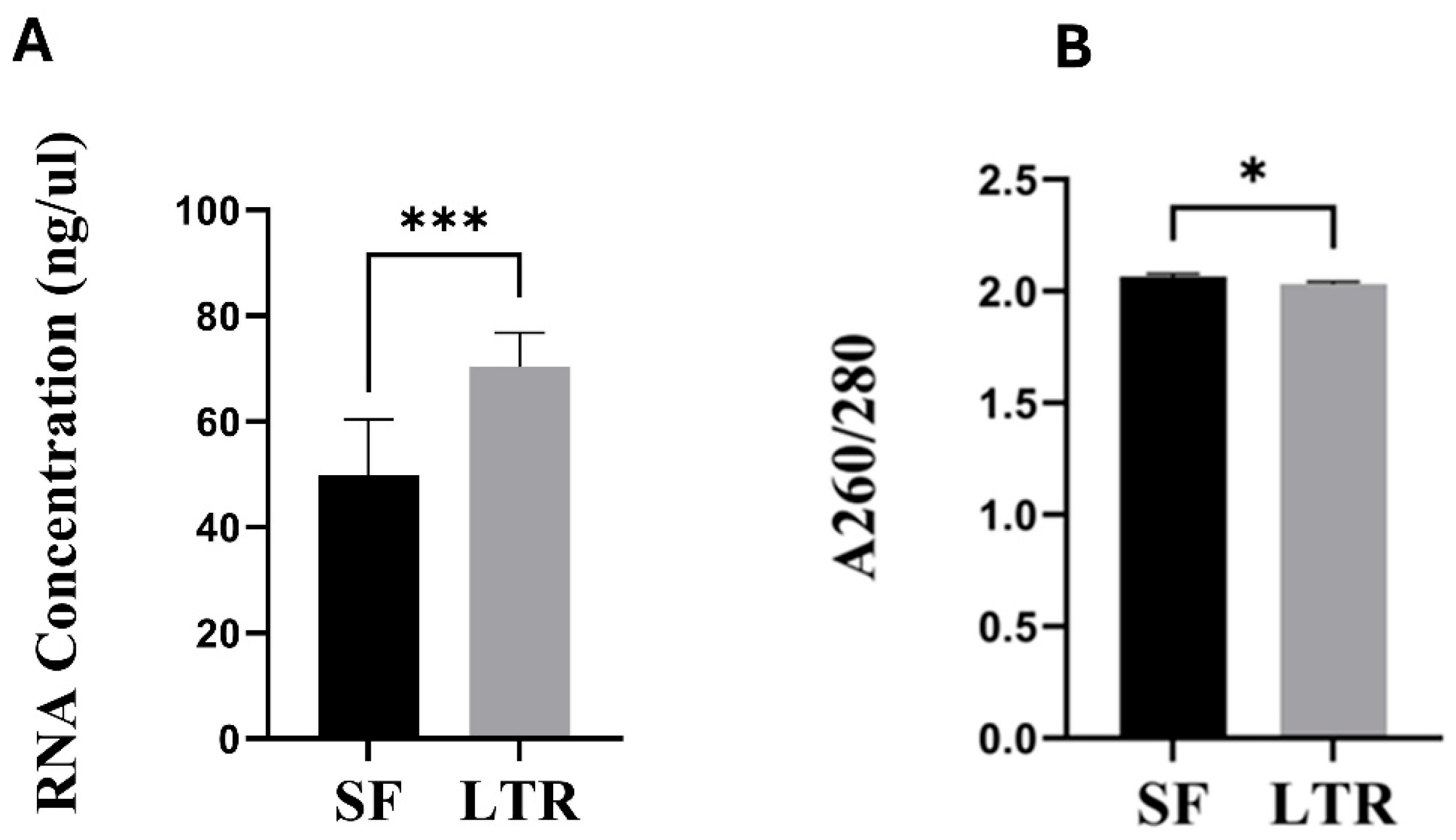

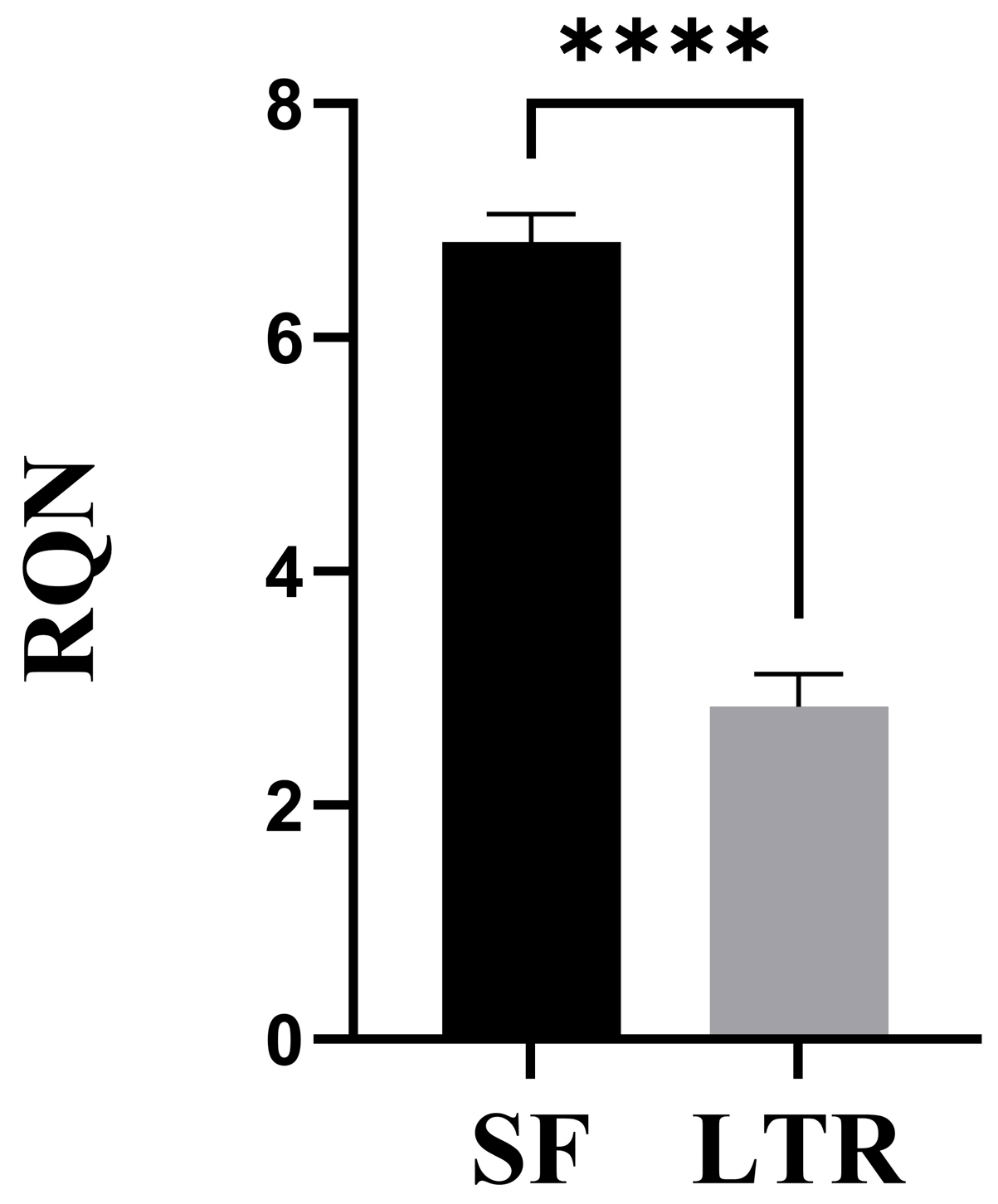

2.4. RNA Quantity and Quality Indicators

Concentration (ng/uL), A260/280 ratio, and RNA quality number (RQN) were used for quantity and quality assessment in SF and LTR samples. Concentration and A260/280 ratio were measured using a NanoDrop® (ND-LITE Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA). RQN was assessed using a Fragment Analyzer

TM Automated CE system (Advanced Analytical, North Brunswick, NJ, USA). An A260/280 value between 1.8 and 2.2 was considered as an ideal indicator for purity [

17], while RQN of 7 or above (scale of 1 to 10) was considered ideal for RNA integrity [

18].

2.5. Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using statistical software R (R version 4.3.0). Normality was evaluated using Shapiro-Wilk test. Treatments were compared using a matched pairs analysis for concentration, A260/280 ratio, and RQN. Within each treatment, a correlation analysis was applied between all the described variables and time of placental expulsion. Statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05. Data is presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of extracting high quality RNA from naturally delivered placenta in sheep, and to compare two preservation methods in order to identify the most adequate protocol for further transcriptomic analysis. Major findings are that RNA can be extracted from expelled ovine placental tissue, regardless of the preservation method. However, RNA integrity is higher in the tissue preserved by the snap frozen method.

Our results indicate that the concentration of RNA was higher in the LTR than SF treatments. This may be due to actual variation between methods, but it could also be an artifact. A precise amount of tissue was harder to get from SF than LTR samples, given the difficulty of cutting the sample without letting it thaw. As a result, it is possible that bigger pieces of tissue were obtained from SF than LTR samples, thus creating an unintended artifact effect in RNA concentration, since all samples were eluted in the same final volume. Hence, even when there are significant differences in RNA concentration between methods, we cannot assume that one method is better than the other in this aspect. Regardless, RNA concentration is less relevant than other parameters such as RNA integrity when performing transcriptomics analysis [

19], so it is not the most relevant indicator to recommend one preservation method over the other. In terms of purity, even when A260/280 ratio was slightly higher in SF than in LTR samples, both groups showed average values above 2, which are in the desired range to consider the extracted RNA to be free of contaminants such as proteins or other solvents derived from the extraction protocol [

20].

The most relevant difference between the two methods was RNA quality. As mentioned before, RQN is a value that ranges from 1 to 10, being 1 the worst quality indicating a fully degraded molecule, and 10 the best quality, or intact RNA [

21]. This value is obtained using a Fragment Analyzer system. It is based on the analysis of an electropherogram which in undegraded samples shows two clear peaks, associated to the 18S and 28S ribosomal subunits respectively, which normally appear in undegraded eukaryotic RNA [

22]. The RQN value is calculated based on the area under the 18S and 28S peaks, and the ratio between the peaks. This value is equivalent to RNA integrity number (RIN), which is more broadly used, and it is also based on an electropherogram analysis, but performed in a Bioanalyzer System [

23]. Values of RQN above 7 are representative of well-preserved and high-quality RNA, which is suitable for analysis such as qPCR, RNA-seq, or other transcriptomic techniques [

18]. RNA integrity is the most important parameter to consider when performing transcriptomics analysis, because a degraded molecule will lead to erroneous results [

24,

25]. For example, Huang et al. (2013) [

26] showed that degraded RNA differentially affected the expression of endogenous reference genes in the human placenta. Other studies have also reported that, as RIN values decreased, the expression of genes in human placenta appeared falsely increased [

27]. According to this, the only preservation method that achieved acceptable results was SF, at least under the protocol and conditions in which this study was performed. To our knowledge, this is the first report indicating that it is possible to obtain high quality RNA from naturally expelled ovine placenta. We expect that this will serve as a basis for other research groups to consider the application of this non-invasive sampling approach.

Regardless of our results, we cannot obviate the possibility that RNA

later® could provide better results using a different protocol. The fabricant recommends different alternatives to preserve tissue using RNA

later®[

28], which includes the one used in this study, except for the fact that we left the submerged samples at room temperature for two weeks. The reasons for this choice have been stated before and are related to the field conditions in which the study was conducted, which did not allow access to freezers or refrigerators during the lambing period, which lasted for 2 weeks. We found a severe RNA degradation when using RNA

later® as preservation method under the described conditions. Other studies report similar results, indicating that a better preservation of tissue is achieved using the snap frozen technique [

29], even when leaving samples in RNA

later® at 4°C for just one day, and then freezing them, which fully complies with the fabricant recommendations.

By contrast, a time course study analysis of RNA quality in the human placenta found that preservation in RNA

later® yielded a higher RIN than the snap frozen technique in long-term stored samples, while there were no differences between methods when stored for short time before transcriptomics analysis [

25]. However, in this study samples preserved in RNA

later® were immediately frozen. Similarly, another study reported that RIN values were higher in human placental tissue collected up to two hours after delivery [

30] when preserving them in RNA

later® (4°C overnight, -80°C for long-term storage) compared to snap frozen technique. Currently, the literature for human placenta is still not clear on which preservation method is more suitable for extraction of high quality RNA [

3], and to our knowledge a guidance in this regard is inexistent for the ovine placenta. Most likely, the best preservation method would be dependent on the particular conditions in which each experiment is conducted and the resources that the investigator has access to.

Regardless of the preservation method, the literature usually suggests that placental samples must be collected as soon as possible [

3], as this tissue is high in RNase activity [

8], and it also rapidly degrades after parturition. In naturally expelled ovine placenta, the time of collection is a major concern because this organ may take up to 6 hours to be delivered [

13]. There is also considerable inter-animal variability in time of placental expulsion, which in the present study ranged between 2 and 5 hours. Although successful RNA extraction from postpartum placenta has been described in the bovine [

31] and equine [

32], in those studies samples were collected trans cervically at 30 min and 2 hours postpartum, respectively. Here we largely exceed those times, and the inter-animal variation was impossible to control by the investigator, being critical as it may differentially impact RNA quality. For example, a study in human placenta described that RNA RIN has an inverse correlation with sampling delay [

27], but in this case placental collection was delayed while the organ was already outside the maternal body. In our study, placenta remained inside the body of the animal and was immediately sampled once expelled, so the sampling delay period did not occur under environmental conditions. This may be associated with the fact that we did not find a significant correlation between the time of placental expulsion and RNA concentration, A260/280 ratio or, most importantly, RQN in both SF and LTR samples. This is also supported by other studies that have found no association between a 24 h sampling delay and RNA yield or quality in postmortem reproductive bovine tissues [

33]. Research from the human placenta also states that storing placental tissue a 4°C up to 48 hours does not affect RNA quality [

34]. The findings of those studies, and the ones of the present research, are relevant to support the applicability of post-delivery ovine placental collection, which opens possibilities to perform transcriptomics studies in an organ that is hard to collect without applying invasive procedures.

Although time for placental expulsion does not affect RNA quality, it is unknown if this could have an effect on gene expression, in the event that gene expression patterns change over time from parturition to natural placental delivery. This has not been evaluated in the ovine placenta, and it warrants further investigation. However, data from studies in bovine reproductive tissue indicates that there is no impact on expression on genes such as β-actin, GAPDH, and transforming growth factor β in samples collected up to 96 h postmortem [

33]. Also, studies from the human placenta indicate that meaningful gene expression analysis can be performed from RNA extracted from placentas stored at 4°C or even at room temperature for up to 48 hours, as long as RNA integrity was preserved [

34]. These results indicate that the time of tissue collection does not affect gene expression in samples with preserved RNA integrity. However, a recent study from the human placenta suggests that some mRNA transcripts may change as placental collection time increases, regardless of RNA quality [

35]. This is an issue that requires further investigation in samples from naturally expelled sheep placenta, as available literature is still contradictory and mostly from human.

Other limitations of obtaining RNA from expelled ovine placenta, regardless of sample quality, are associated with the fact that this method allows for collection of cotyledonary tissue (fetal portion of the sheep placenta), but not caruncular tissue (maternal portion of the sheep placenta), which is not expulsed. Additionally, since gestation is not intervened, this method does not allow for performing time-course studies of placental gene expression throughout pregnancy. The investigator must evaluate how much these limitations may impact on the required data according to the purpose of the research, while also considering that the method validated through this research aligns with the refinement principle for animals used in research as it significantly reduces the invasiveness of the sampling method [

15,

16].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S., J.B., F.A., F.S., C.U., M.R.; methodology, C.S., J.B., F.A.; formal analysis, C.S., J.B.; investigation, C.S., J.B., F.A., M.A., F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S, F.A., J.B.; writing—review and editing, C.S, J.B., F.A., M.A., F.S., C.U., M.R.; supervision, C.S., J.B.; project administration, C.S.; funding acquisition, C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.