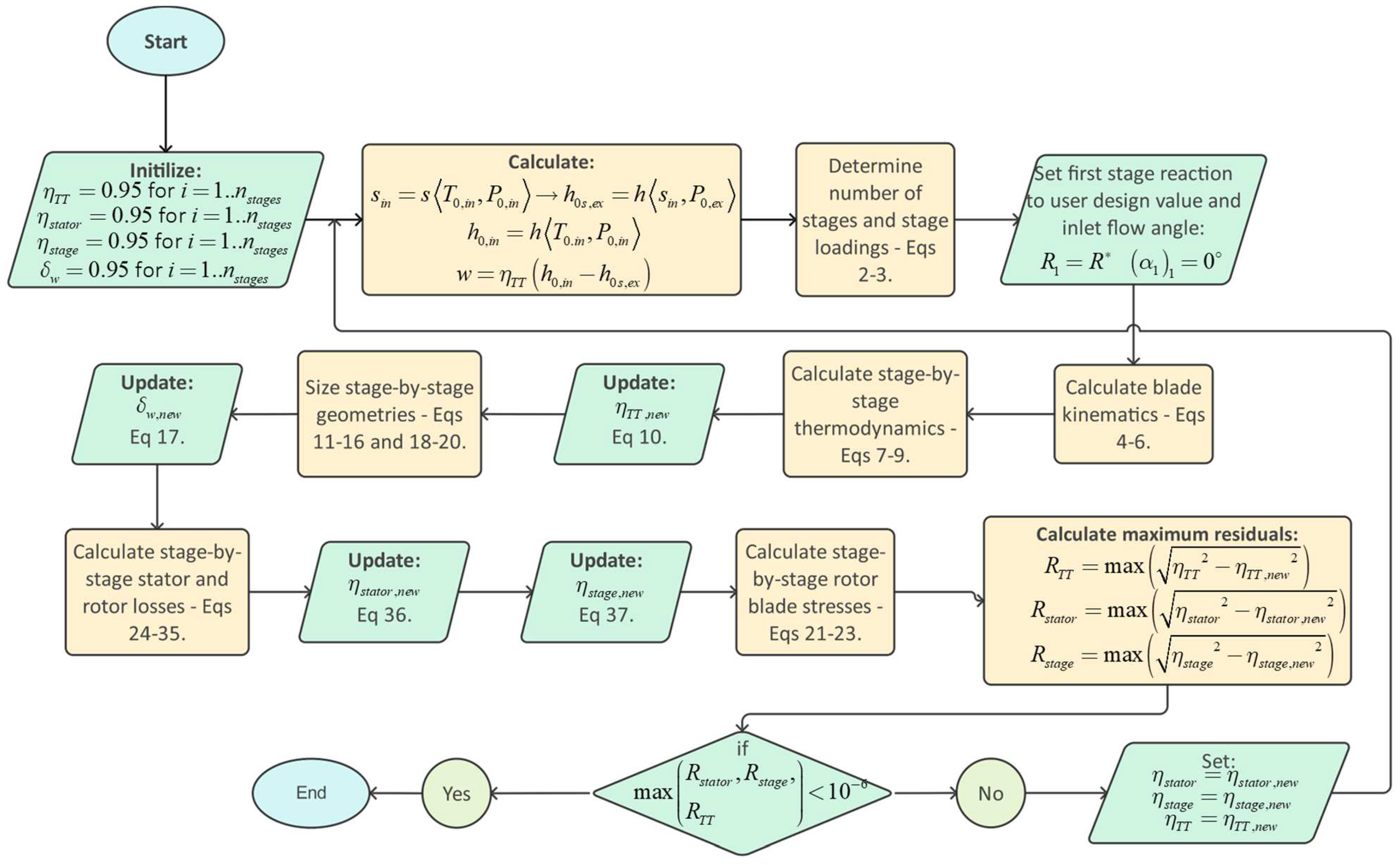

3.1. High-pressure turbine mean line design results

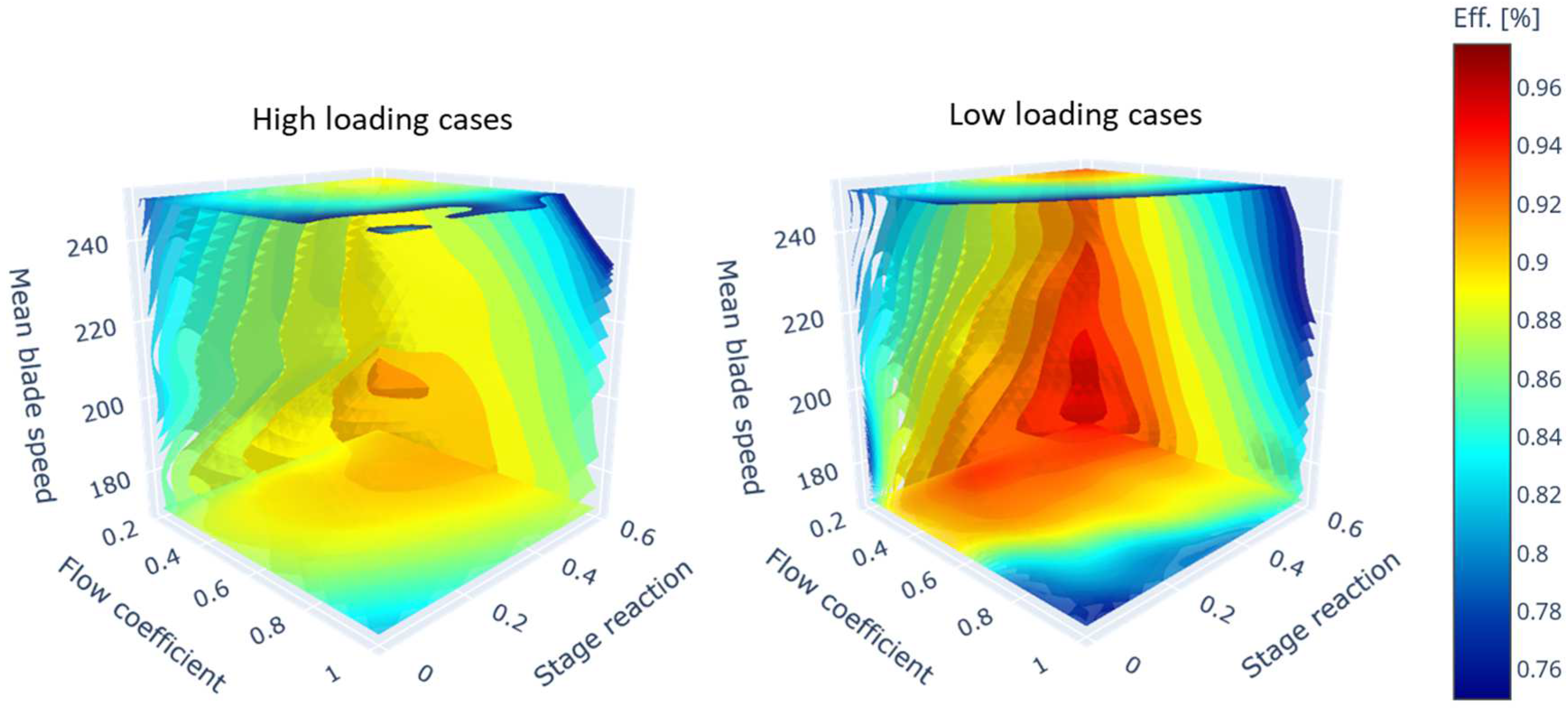

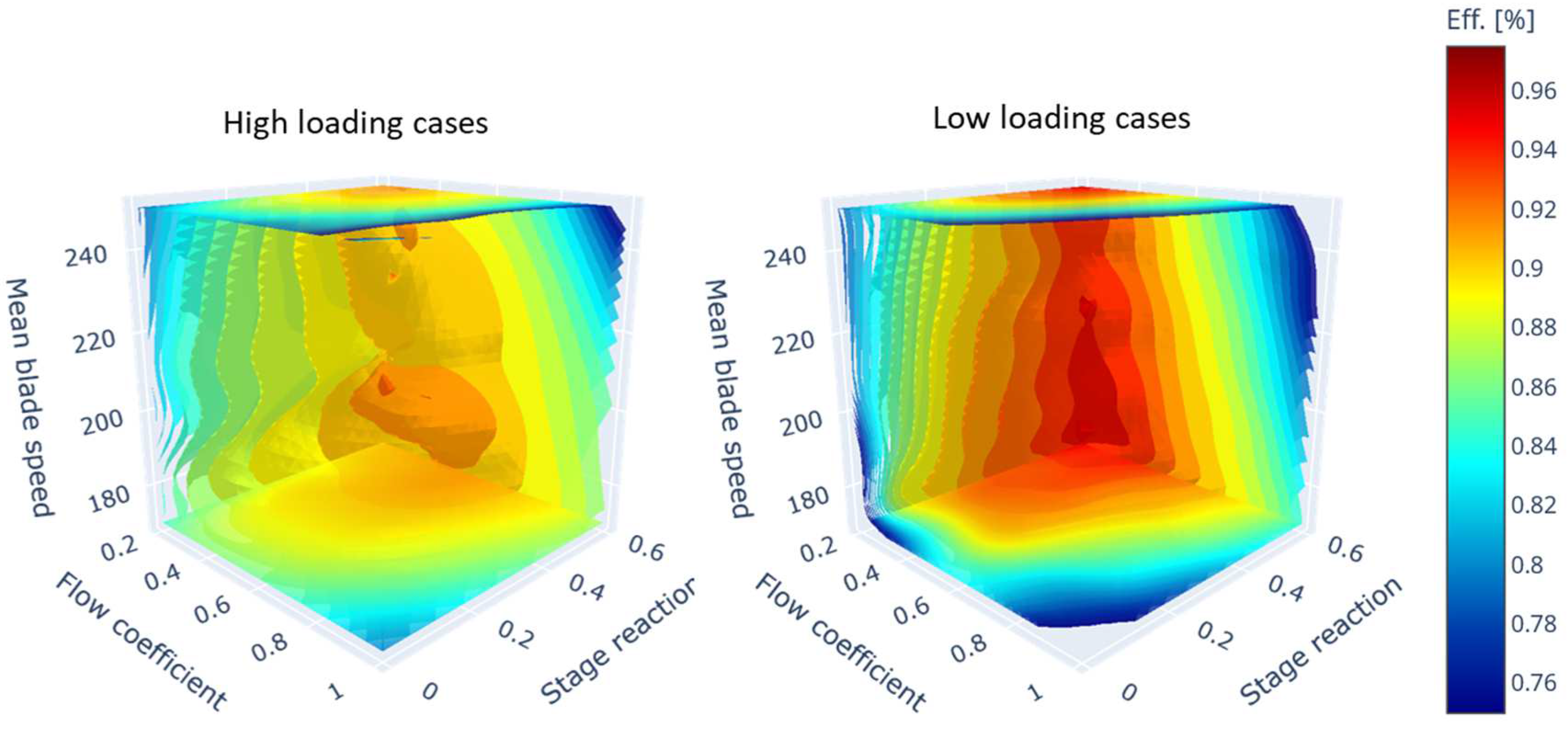

Figure 4 presents iso-surface contour plots of isentropic efficiency as a function of stage reaction, flow coefficient, and mean blade speed. These plots are based on the outputs of the Kriging surrogate model constructed using the design of experiments dataset for the high- and low-loading HP turbines. Comparing the ranges of the calculated efficiencies, it is seen that the low loading turbines have higher achievable efficiency values compared to the high loading machines, specifically in the stage reaction range of 0.4-0.6, flow coefficient range of 0.2-0.5 and blade speed range of 170-240 m/s. These ranges will be referred to as the

high efficiency ranges from here on. Within these ranges, the average rotor total pressure loss coefficient for the high-loading cases is

. For the highly loaded designs within the mentioned range, the highest average loss contribution is the tip clearance loss,

, followed by the secondary loss coefficient,

. For the low-loading cases within the high efficiency ranges the average total rotor pressure loss coefficient is

. For the low-loading turbines the highest average loss contribution is the secondary loss,

, closely followed by the tip clearance loss,

.

The average tip clearance loss for the high-loading cases within the mentioned high-efficiency ranges is 77% higher than in low-loading designs, primarily due to the higher gas deflection angles within the high loading designs. The average gas deflection angle within the low loading rotors is 22 degrees compared to 49.5 degrees for the highly loaded machines. This leads to the theoretical blade lift coefficient [Equation (32)] being significantly larger for highly loaded machines, and in turn the tip loss coefficients. For the secondary losses between the two loading set points, the calculated quantities for the high- and low-loaded designs are relatively similar with a 12% relative difference.

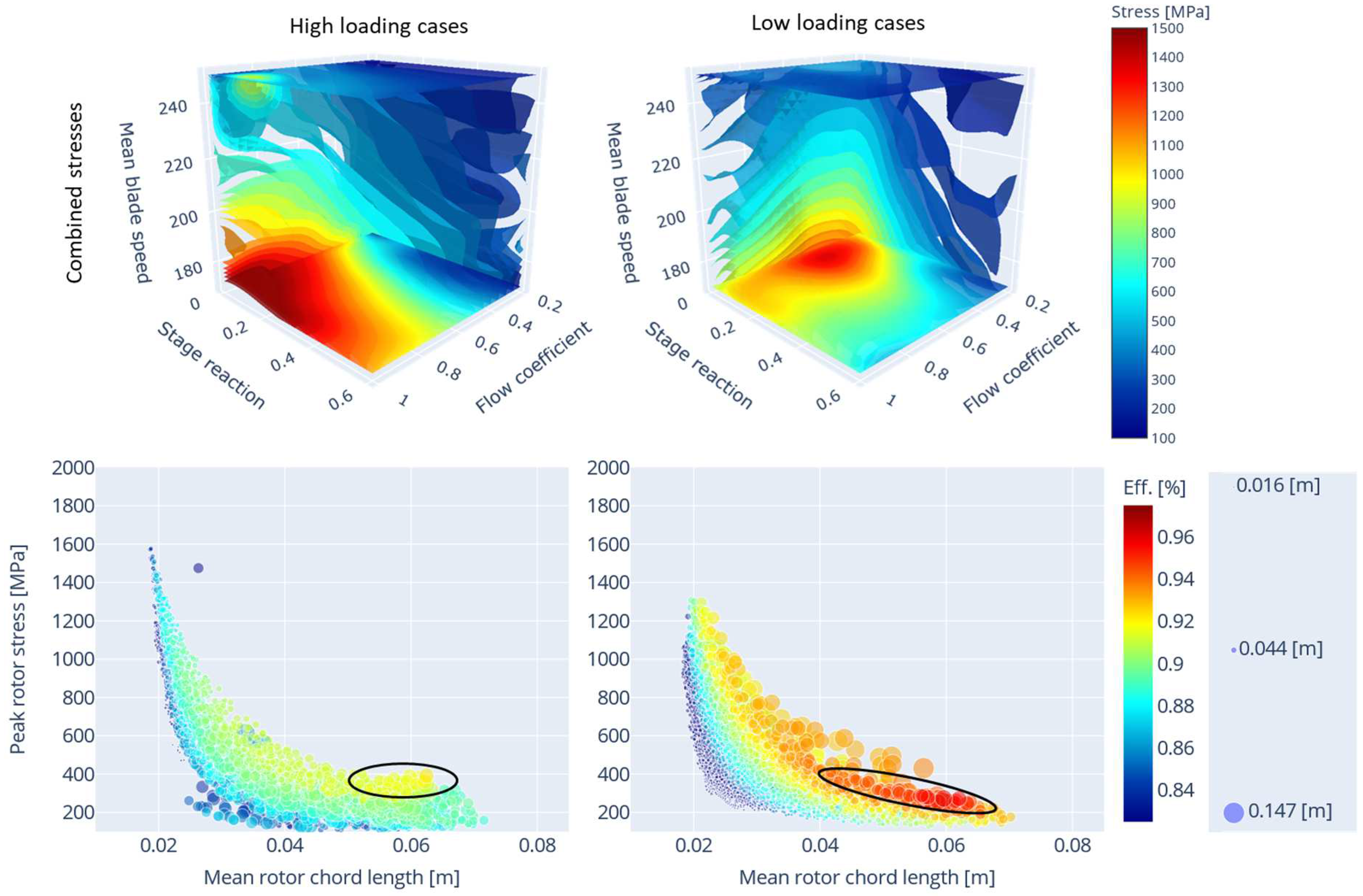

Figure 5 (top) shows the iso-surface contour plots for the peak stage combined rotor stresses [

] within the various designed turbines for both the high- and low-loaded conditions.

Figure 5 (bot) shows the total-to-total isentropic efficiency of the designs as a function peak rotor stress, chord length and mean rotor blade height (marker size).

From

Figure 5 (top) it is interesting to note that the peak stresses for the highly loaded design cases occurs at high flow coefficients and low stage reactions, whereas for the low-loading machines the peak stresses are found at low stage reactions and moderate flow coefficients between 0.3-0.6. This is since at lower stage loadings the gas deflection angles are smaller compared to the highly loaded designs. This in turn results in lower stagger angles and smaller chord lengths, which [as seen in Equation (22)] results in higher gas bending stresses. For both stage loading design setpoints, the minimum stresses are observed within flow coefficient ranges of 0.2–0.5, stage reaction ranges of 0.4–0.6, and high mean blade speeds above 180 m/s. These design parameters align closely with the high efficiency ranges. Within these high efficiency ranges, the high-loading designs exhibit peak rotor stresses ranging from 125 MPa to 810 MPa, while the low-loading designs show peak rotor stresses between 150 MPa and 850 MPa. The higher peak rotor stress range in low-loading cases are generally attributed to increased gas bending stresses for certain design parameter combinations that result in smaller chords and lower stagger angles. However, within the subsets of design parameters that yield the highest efficiencies the low-loading designs exhibit lower peak rotor stresses compared to the highest efficiency high loading designs. The reduced stresses at high mean blade speeds for both stage loading designs are attributed to the increased meridional velocity for a given flow coefficient through the turbine [as seen in Equation (1)]. This results in shorter blades and smaller flow areas, thereby decreasing centrifugal and gas bending stress. Thus to lower blade stresses, higher mean blades speed are required, but at very high blade speeds turbine efficiencies can suffer.

Figure 5 (bot), shows that for both the high and low loaded designs, as the average rotor chord length (x-axis) reduces the peak combined rotor stresses increases. For high-loaded designs, peak efficiency values are achieved with chord lengths between 55 mm and 65 mm, while for low-loaded designs, peak efficiency values are observed across a broader range of chord lengths, from 40 mm to 65 mm. Within these peak efficiency zones (circled in black), low-loading designs demonstrate the ability to achieve not only higher efficiencies but also lower peak stresses. This can be ascribed to the smaller change in absolute tangential velocities,

, across the rotors in combination with relatively large chord lengths which are achieved for high rotor boss ratios and tall rotor blades.

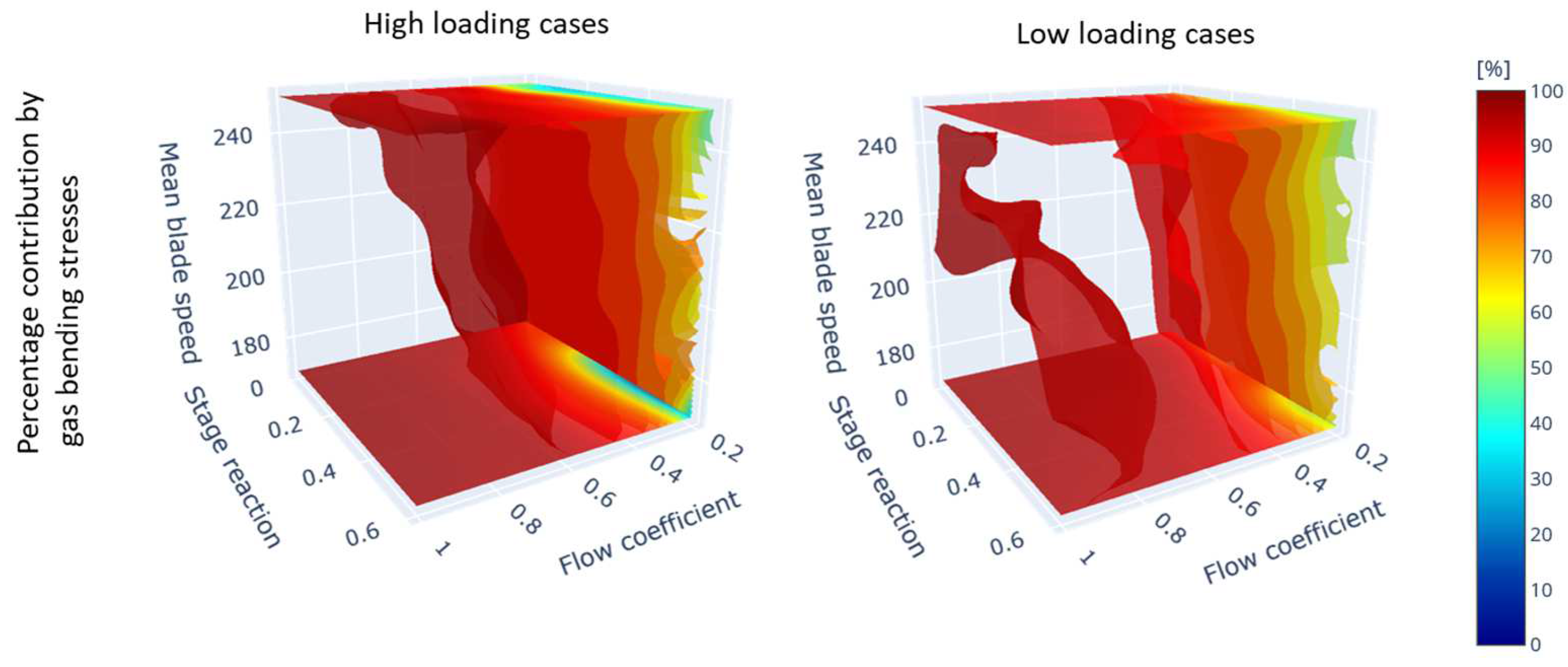

As seen in

Figure 6 for the design parameter inputs outside the high efficiency ranges, the gas bending stresses dominate. This is mainly since at these design specifications the chord lengths of the rotor blade rows become small, resulting in high gas bending stresses. It should be noted that even inside the high efficiency ranges the gas bending stresses also play a significant role as observed by [

5]. An additional factor that contributes to these high gas bending stresses is the high mass flow rate combined with significant change in absolute tangential velocity through the rotor that results in large stresses.

The generated mean line analysis data enabled the identification of design parameter combinations for both high- and low-loading cases that satisfy specific user-defined requirements. Specifically, the parameters were determined for the individual design achieving the lowest peak rotor stress and separately for the individual design achieving the highest isentropic efficiency. These design points are shown in

Table 3.

For the two highest efficiency designs, it is seen that the low loading turbine design achieves not only a 3.8% higher efficiency compared to the high loading design, but also a 43% lower combined peak rotor stresses. In both high and low-loading designs, high stage reaction and low flow coefficients are preferred. Additionally, lower mean blade speeds are desirable, as they lead to larger blade heights, which reduce secondary loss effects and improve isentropic efficiency. Due to the lower stage loading in the low-loading design, the number of stages is significantly greater compared to the high-loading design. This results in nearly a 50% increase in turbine volume of the low-loading design compared to the high-loading design. The turbine volumes are estimated as truncated cones, based on the casing diameters of the first and last stages.

For the two designs with the lowest stress values, both scenarios favor high mean blade speeds to reduce centrifugal stresses by shortening rotor blade heights and thus flow areas. The high-loading design achieves a lower peak rotor stress compared to the low-loading design. This is due to reduced gas bending stresses in high-loading configurations at higher mean blade speeds, where taller rotor blades result in larger chords. In contrast to the highest-efficiency designs, the lowest-stress designs exhibit significant differences in flow coefficients and stage reactions between the high- and low-loading configurations, emphasizing the distinct factors influencing peak rotor stresses. Lastly, both low stress designs suffer approximately 5.5% reduction in efficiency compared to the highest efficiency designs.

Due to the differences in isentropic efficiencies and peak rotor stresses among the previously discussed design options, optimal designs were identified for both high- and low-loading turbine configurations. These optimized designs are listed in the last two rows of

Table 3. The optimized designs for both high- and low-loading configurations favor stage reactions and flow coefficients of approximately 0.59 and 0.2, respectively. The primary input variable that differs significantly between the two loading designs is the mean blade speed. This difference arises because the low-loading design inherently tends to experience higher gas bending stresses. To combat this, the optimization algorithm increases the mean blade speed which increases the boss ratio and in turn the chord lengths, which drives down the bending stresses. Although the low-loading optimal design is a larger turbine compared to its high-loading counterpart, it achieves higher isentropic efficiency and lower peak rotor stresses, making it the more desirable option under the design operating conditions. When comparing the optimal designs to other design scenarios, it is observed that, on average, the optimal designs result in a 3% reduction in efficiency compared to the highest efficiency designs. In contrast, when compared to the lowest stress designs, the optimal designs show a 29% increase in peak rotor stress. This represents a well-balanced trade-off between stress reduction and efficiency maximization.

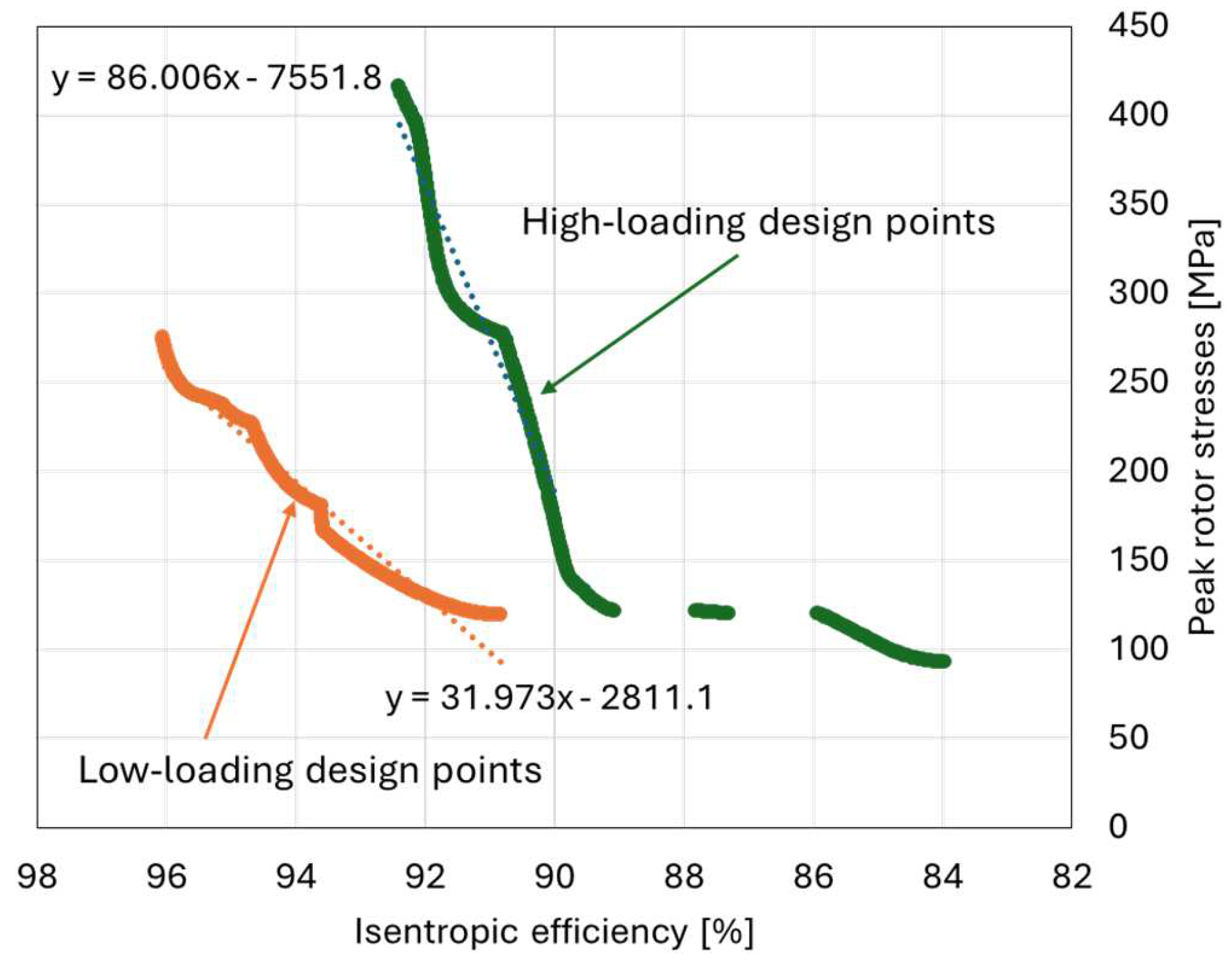

To gain further insights into the optimization of the two loading design options, the Pareto fronts of non-dominating optimal solutions are plotted and shown in

Figure 7. The results indicate that for the high-loading design, any efficiency increase beyond approximately 90% incurs a significant penalty in peak rotor stresses. Specifically, the gradient of the Pareto front above 90% is 86 MPa per percentage point of efficiency, meaning a 1% increase in efficiency results in an 86 MPa rise in peak rotor stress. In contrast, the low-loading design exhibits a less steep gradient of 31.9 MPa per percentage point of efficiency at higher efficiency levels, again highlighting the favorability of the low-loading design.

Generally, it can be seen assessing all the design scenarios in

Table 3 that the high-loading designs result in significantly more compact turbines, but at the cost of lower efficiency. High-loading designs achieve a 10–55% reduction in turbine volume, depending on the design scenario (highest efficiency vs. lowest rotor stress), with a corresponding decrease in isentropic efficiency of 2.9–4%. However, from the perspective of peak rotor stresses, high-loading designs offer no distinct advantage over low-loading designs. Typically the peak stress for Ni-Cr-Co alloy is taken as 303 MPa [

5] and often it is desirable to keep the peak stress below 260 MPa [

1]. Therefore, the peak rotor stresses of the two highest efficiency designs are outside the allowable stress limit.

3.2. Low-pressure turbine mean line design results

Figure 8 shows the iso-surface contour plots of isentropic efficiency as a function of stage reaction, flow coefficient, and mean blade speed for the LP turbine designs. Similar trends are seen for the LP turbines as for the HP turbine trends in

Figure 4, where the highest efficiencies are found for flow coefficients between 0.2-0.5, stage reaction between 0.4-0.6 and mean blade speeds above 170 m/s. The LP turbine designs achieve higher efficiencies compared to the HP turbine designs within the specified ranges. The average isentropic efficiency is 89.6% for high-loading HP turbines, compared to 90.6% for high-loading LP turbines within the high efficiency ranges. Similarly, for low-loading designs, HP turbines achieve an average efficiency of 91.2%, while LP turbines reach 93.1% within the high efficiency ranges. As previously mentioned, within both LP and HP turbine design datasets, the low-loading configurations achieve the highest isentropic efficiencies.

Within the above-mentioned high efficiency ranges the average total rotor pressure loss coefficients for the high- and low-loading LP designs are and respectively. For the high-loading designs within the above-mentioned ranges, the highest aerodynamic loss is the tip clearance loss with an average value of followed by the secondary loss with an average value of . For the low loading designs the main losses are and .

Similar to the HPT designs, the primary difference in tip loss coefficients between the high- and low-loading designs arises from variations in mean gas deflection angles, which significantly impact the blade lift coefficients. The mean high-loading rotor gas deflection angle within the mentioned ranges is 49 degrees and for the low-loading designs it is 21.8 degrees. As with the HPT designs, the secondary loss coefficients remain similar across the different loading configurations. An interesting observation is that the calculated profile loss coefficients, , are notably small (between 0.0-0.005) for the high- and low-loading HP turbine designs, as well as the low-loading LP turbine designs. However, for the high-loading LP turbine designs, within the specified high efficiency ranges, the mean profile loss coefficient is comparatively higher, . This observation is most likely due to the higher gas velocities within the highly loaded LP turbine due to the lower gas densities.

Figure 9 (top) shows the iso-surface contour plots of combined peak rotor stress for the high- and low-loading LP turbine designs and

Figure 9 (bot) isentropic efficiencies as a function of mean rotor chord length (x-axis), peak rotor stress (y-axis) and mean rotor blade height (marker size).

The combined peak rotor stresses plots for the LP turbines have very similar trends to that of the HP turbines (

Figure 5), the main difference being the magnitude of the peak rotor stresses. As seen in the figure below, the LP turbines have significantly higher rotor stresses compared to the HP turbines. Within the high efficiency ranges, the average high-loading HP turbine stress is 332 MPa, whereas the average high-loading LP turbine stress is 431 MPa. For the low-loading designs, the HP turbines have an average stress value of 333 MPa and the low-loading turbine an average value of 478 MPa. The main reason for the increase in stresses from the HP to LP turbines, is the reduction in fluid density that results in larger flow areas and blade heights which in turn increases the centrifugal stresses as seen in Equation (21). The minimum and maximum peak rotor stresses within the high efficiency ranges for the high-loading LP turbines are 191 MPa and 1064 MPa respectively. For the low-loading LP turbines the minimum and maximum values are 237 MPa and 1150 MPa respectively.

Figure 9 (bot) further shows that for the low-loading designs, the high efficiency design points (circled in black) cover a larger vertical zone compared to the high efficiency high-loading design points, which results in larger variation in peak rotor stresses. For chord lengths between 40–80 mm, where high-efficiency designs are located, low-loading designs have taller rotor blades, leading to higher centrifugal stresses. This is attributed to the increased flow areas at similar chord lengths compared to high-loading designs.

The percentage contribution of gas bending stresses to the combined peak rotor stresses, as illustrated in

Figure 6 for HP turbines, was also calculated for LP turbines. However, it is omitted here for brevity, as the LP turbines exhibited similar trends to the HP turbines.

Table 4 contains the high- and low-loading LP turbine designs that exhibit the overall highest efficiency and the lowest peak rotor stress. For the highest efficiency design scenarios, both the high- and low-loading turbines preferred relatively low flow coefficients and high stage reactions. Furthermore, both designs preferred relatively low mean blade speeds to boost the isentropic efficiency. The low-loading design has a 3% higher efficiency compared to the high-loading design, but the latter has a 6.1% reduction in peak rotor stress compared to the former.

For the two design scenarios with the lowest peak rotor stress, both the low- and high-loading turbines favor high mean blade speeds to minimize centrifugal stresses. The high-loading turbine achieves its stress reduction with moderate stage reaction and low flow coefficient settings, whereas the low-loading turbine achieves its lowest stress with a high stage reaction and high flow coefficient. The high-loading design achieves a 14.6% stress reduction compared to the low-loading design.

Both optimal design scenarios favor high stage reactions and low flow coefficients and similar to the HP turbines, the high-loading design has a lower mean blade speed compared to the low-loading design. The optimal low-loading design has a 3.1% higher isentropic efficiency compared to the high-loading design, conversely the low-loading design has a 1.8% higher peak rotor stress and a 42% greater truncated cone volume. In general, the optimal designs strike a balance between reduced isentropic efficiency and lower peak rotor stresses. From the perspective of efficiency and stress optimization, the low-loading optimal design is preferred over other design scenarios under the design operating conditions.

Figure 10 below shows the Pareto front solutions taking from the optimization procedure of the LP turbines. It can be observed that for high-loading designs, the optimal solutions within the 82-90% efficiency range show no significant increase in peak rotor stress. However, beyond approximately 90%, a noticeable rise in peak rotor stress occurs with each percentage point increase in efficiency. In this region, the gradient of peak rotor stress with respect to isentropic efficiency is 31.11 MPa per percent. Low-loading optimal design points exhibit an exponential increase in peak rotor stress when the isentropic efficiency exceeds approximately 96%. Feasible design points are found within the 91-96% efficiency range. In this region, the peak rotor stress increases with efficiency at a gradient of 19.23 MPa per percent. Therefore, for the optimal design point regions of interest, the low-loading design efficiencies is less sensitive to peak rotor stress.

An examination of all design scenarios in

Table 4 shows that, similar to HP turbines, the high-loading approach significantly reduces turbine volume by 17–71%, depending on the design scenario (lowest rotor stress or optimal design balancing efficiency and stress). For the different design scenarios, the isentropic efficiency drop between the high- and low-loading turbine designs is between 1.8-3.1%. In contrast to HP turbines, opting for a high-loading turbine design scenario can result in a 1.8–14.6% reduction in peak rotor stress. Except for the two highest efficiency design scenarios, all the remaining designs have peak rotor stresses below the desired stress limit of 260 MPa.

3.3. Validation of selected designs using CFD simulations

To validate the optimal designs for the HPTs and LPTs, CFD simulations of the high- and low-loading LP and HP turbines are performed at the design operating conditions (

Table 1). Therefore, in total 4 simulations were performed corresponding to the optimal design scenarios presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4. Selected turbine geometric parameters are provided below in

Table 5.

Table 6 contains the overall results from the CFD simulations of the selected optimal turbines. Overall, the CFD predictions align reasonably well with the mean line analysis design code predictions. However, the CFD simulations consistently underpredict the pressure ratio compared to the mean line analysis, with the largest discrepancy observed in the HPT high-loading case. The pressure ratio prediction errors range from -6.5% to -1.36%. The largest efficiency error is also observed in the HPT low-loading case, with efficiency prediction relative errors ranging between -0.74% and 2.3% across the other cases.

Figure 11 shows the relative Ma number contour plots for the first and final stages of the selected HP high- and low-loading turbines. Comparing the high- and low-loading results, it is seen that generally the Ma numbers are noticeably higher for the latter, specifically in the throat region of the rotor. This is because the low-loading turbine have significantly shorter blades than the high-loading turbine, resulting in smaller flow areas in the throat zones. Further investigation of the contour plots reveals areas of slight flow separation on the pressure surfaces of both final stage rotors. This can be ascribed to the significant concavity of the pressure surface which is a result of the geometry generation which ensures the user-specified throat width, maximum blade thickness, leading edge thickness, trailing edge thickness and blade angles are satisfied. From the high loading mean line analysis the predicted first and final stage rotor exit relative Ma numbers are 0.42 and 0.44 respectively whereas the CFD predicted values are 0.43 and 0.39, respectively. For the low loading turbine the mean line analysis predictions for the rotor exit Ma numbers are 0.45 and 0.48 respectively and the CFD predictions for these Ma numbers are 0.45 and 0.44, respectively.

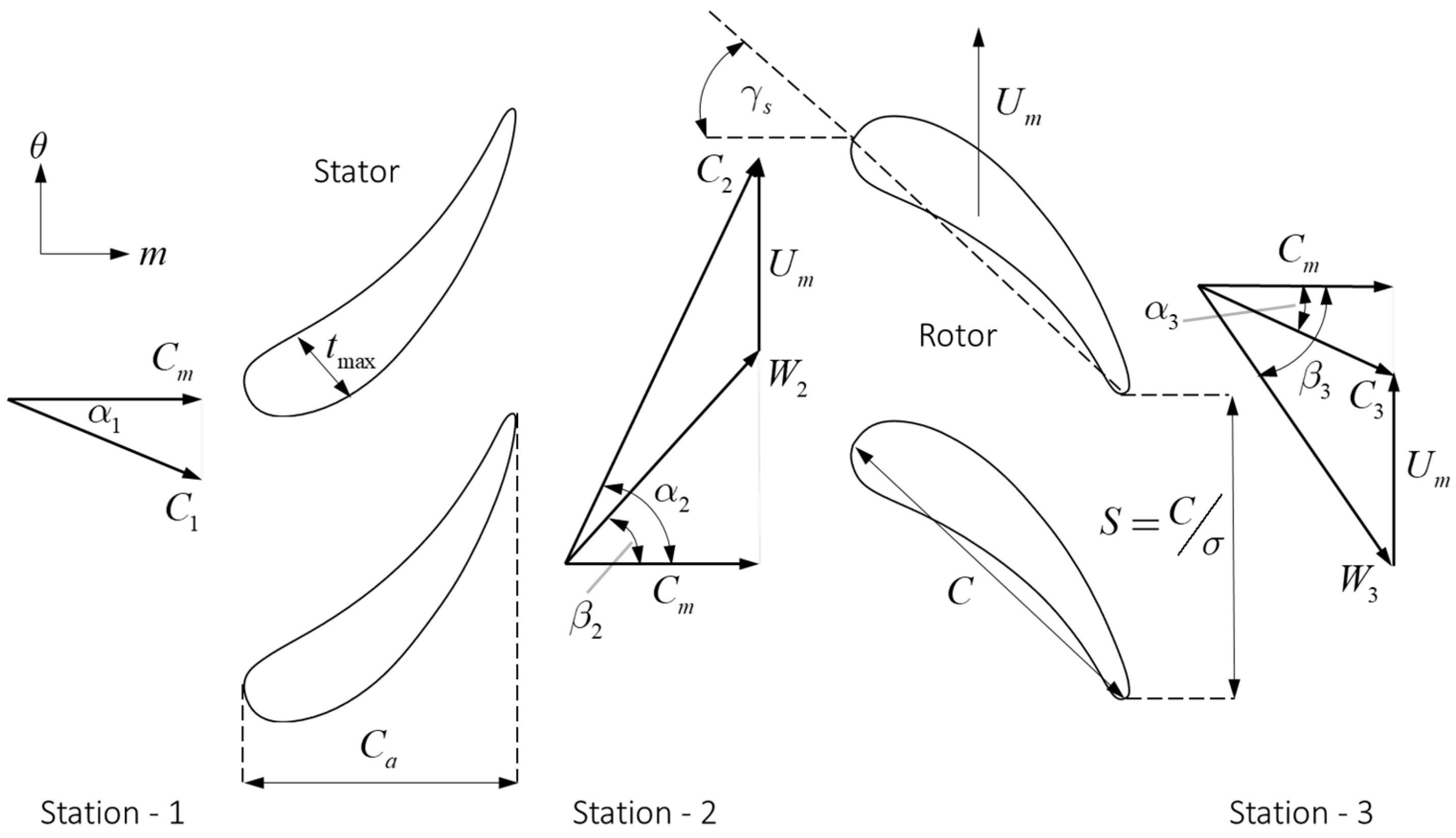

From

Table 5 it is noted that the gas deflection angles within the HP low loading turbine design are comparatively small compared to those of the high loading turbine design. Small gas deflection angles at design operating point could potentially be detrimental to performance at lower loads for a single shaft arrangement. That is because at lower loads the tangential blade speed component

(see

Figure 2) remains constant but the meridional velocity component

reduces as the mass flow rate through the turbine is reduced. For low gas deflection angles, this could lead to the outlet absolute tangential velocity component

at the rotor exit to swap direction (from pointing downward to pointing upward in

Figure 2) which leads to significant reduction in turbine efficiency. But for higher loaded machines where the gas deflection angles are larger, the reduction in mass flow rate would not necessarily lead to the tangential velocity component to swap direction. This was briefly checked with the CFD turbine models, and it was indeed the case. Please note that for the sake of brevity these results are not shown. For the highly loaded HPT the turbine successfully turned down to approximately 70% of the non-dimensional design mass flow rate, with a resultant isentropic efficiency of

(

). The simulations showed that the low loaded HP turbine design cannot effectively operate at 80% of the design non-dimensional mass flow rate, as they indicated a negative shaft power output. This is attributed to the low-loading turbine design philosophy, which, under the high mass flow rates typical of sCO₂ Brayton cycles (due to large fluid densities), results in low deflection angles. This, in turn, restricts the turbine’s turn down capabilities. Nevertheless, the low loading design could run adequately at 85% of the design non-dimensional mass flow, which resulted in an isentropic efficiency of

(

). To circumvent this reduced turn down capacity a more effective design approach would involve adopting a design parameter selection strategy that strikes a balance between the efficiency, rotor stresses, turbine size and turn down capabilities.

Figure 12 shows the contour plots of relative Ma numbers for the first and final stages of the LPT selected optimal designs. The first stage of the high loading design shows higher Mach numbers compared to the low loading design. However, in the final stage, the low loading design exhibits noticeably higher Mach numbers than the high loading design. The specific areas of interest are the Mach numbers at the throats of the first-stage stator and the final-stage rotor of the turbine. Furthermore, a significant amount of flow separation is observed on the pressure surface of the final stage high loading rotor, whereas the flow separation on the pressure side of the final stage low loading turbine design is more subtle. The high loading turbine mean line analysis predicts the exit relative Mach numbers of the first and final stage rotors to be 0.47 and 0.48, respectively. In comparison, the CFD predictions for the first and final stage rotor exit Mach numbers are 0.51 and 0.43, respectively. For the low loading turbine design the mean line analysis predicts first and final state rotor exit Ma numbers of 0.47 and 0.49 respectively. The corresponding CFD predictions for the first and final stages are 0.48 and 0.475, respectively.

An analysis of the figures in

Table 5, reveals that, similar to HPTs, the rotor gas deflection angles for the low loading design are relatively low. This again leads to limited turn down range. For the low loading LPT CFD simulations showed that the machine cannot be effectively turned down to 85% of the design non-dimensional mass flow rate. At 90% of the design mass flow rate the machine operated successfully with turbine isentropic efficiency and pressure ratio values of

and

respectively. As seen in

Table 5, for the high loading LPT, the rotor stages following the first stage also have relatively low gas deflection angles (14.9 degrees), which results in the machine not being able to turn down to 80% of design non-dimensional mass flow rate before large parts of the turbine starts to transfer work into the fluid. At 85% mass flow rate operation is achievable with resultant isentropic efficiency and pressure ratio values of

and

respectively.