1. Introduction

Cyprinid herpesvirus 3 (CyHV-3), commonly known as koi herpesvirus (KHV), is a pathogen of koi and common carp (

Cyprinus carpio) that causes significant disease and mortality in young fry under 4 months of age [

1,

2]. The mortality of juveniles from CyHV-3 infection can reach 80-100% [

2,

3]. The acute CyHV-3 infection can cause necrosis and hemorrhage of the gills (red and white mottled gills), sunken eyes, pale patches or blisters on the skin, and external hemorrhages [

1,

2,

3]. The virus can also infect the kidney, spleen, fin, intestine, and brain [

4,

5]. CyHV-3 is a member of the family

Alloherpesviridae within the order of

Herpesvirales [

6]. Like other herpesviruses from

Herpesviridae, CyHV-3 can also become latent in recovered fish from either symptomatic or asymptomatic infections [

7,

8,

9]. Therefore, healthy-looking koi or common carp can harbor CyHV-3 latent infection without clinical signs [

9,

10]. CyHV-3 reactivation from latency under stress conditions can cause inflammation in various organs and death, and infectious viruses from reactivation can spread to naïve koi and cause disease [

11,

12]. Currently, no treatment or effective vaccine has been developed to control CyHV-3 infection in koi, one of the most popular ornamental fish. There is a need for anti-CyHV-3 drugs to be developed to protect CyHV-3 infection in koi.

Harmaline (HAL) and Harmine (HAR) are pharmacological β -carboline alkaloids with similar chemical structures that are widely distributed in plants,

Peganum harmala [

13]. They possess significant inhibitory activities against acetylcholinesterase (AChE), monoamine oxidase (MAO), and. myeloperoxidase (MPO) (14, 21). They are found to be potent antioxidants and have anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and anti-hypertensive effects [

14]. Both natural and synthetic β -carboline alkaloids were shown to have inhibitory effects against cancerous cells, parasites, fungi, bacteria, and viruses [

15]. HSV-1 was the first virus reported to be affected by certain βC alkaloids (Eudistomins) obtained from the colonial tunicate Eudistoma olivaceum [

16]. Since then, the 9-butyl-harmol, a β-carboline derivative, was demonstrated to be effective against paramyxoviruses [

17]; 9N-methylamine, another synthetic β-carboline derivative, was found to be effective against DENV-2 infection [

18]. HSV infection was shown to be affected by HAR and the 9,9'-norharmane dimers (nHo-dimer), which also belongs to the β-carboline group [

15,

19,

20]. It has been shown that HSV-2 infection can be blocked by HAR

in vitro with EC50 value at around 1.47μM and CC50 value at around 337.10μM [

19], which suggests that HAR has high potency against herpesviruses. Since HAR is potent against MAO and MPO [

21], it is speculated HAR may block HSV-induced ROS production via enhancing innate immunity against virus infection. Indeed, HAR was shown to able to reduce NF-κB activation, IκB-α degradation, and p65 nuclear translocation during HSV-2 infection [

19]. Therefore, HAR may have a broad anti-viral effect via boosting innate immune responses against viral infections [

22]. CyHV-3 is also a herpesvirus with similar replication strategies like HSV-1 and HSV-2. We hypothesized that CyHV-3 is also sensitive to β -carboline alkaloids during replication. HAL has a similar structure to HAR with better solubility than HAR and has not been tested against CyHV-3 infection. Therefore, in this study, HAL was evaluated against CyHV-3 infection

in vitro and

in vivo, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses, Cells, and Chemicals

The United States strain of CyHV-3 (CyHV-3-U) was a gift from Dr. Ronald Hedrick. The koi fin (KF-1) cell line (also a gift of Dr. Ronald Hedrick ) was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. St. Louis, MO) and incubated at 22°C. CyHV-3 viral stocks were prepared by infecting KF-1 cells in 75 cm

2 flasks with CyHV-3-U at 0.1 multiplicity of infection (MOI) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) and incubated at 22°C. As reported previously, the viral stock was titrated by a standard plaque assay [

8,

23]. Harmaline (cat no. 51330-1G, Sigma-Aldrich) and Acyclovir (ACV) was purchased from BioVision (Milptitas, CA)

2.2. CyHV-3 Plaque Reduction Assay Following Drug Treatment

KF-1 cells were seeded in 12.5 cm

2 tissue culture plates with approximately 2 × 10

5 cells/plate on the day before infection. Before the treatment, three replicate plates were infected with 300 µl of CyHV-3 at ~4 × 10

3 plaque-forming units (PFU)/ml. Following a 1-h viral absorption, the cells were cultured in the presence or absence of Harmaline (HAL) or ACV for different treatment times at different times post-infection, then washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cultured in 3 ml of 3% methylcellulose overlay media for 10 days at 22 °C in an incubator. The plates were then fixed in 20% methanol and stained with 1% crystal violet, and the plaques were counted [

8,

23].

2.3. Harmaline Cytotoxicity Assay In Vitro

Ninety-six-well plates were seeded with ~7 × 104 KF-1 cells per well and grown overnight at 22°C. The cells were washed once with PBS and treated in 100μl media containing HAL or ACV at indicated concentrations at 22°C for 24 h. The drug-treated cells were then washed once with PBS and replenished with fresh DMEM containing 5% FBS and antibiotics (as described above) and further incubated for 24 h. After incubation, cell viability was examined by using colorimetric cell viability kit III (XTT) (PromoKine, Huissen, Netherlands). Briefly, 50 μl of the XXT reaction solution was added to each well, and then the plate was incubated at 37 °C incubator for 3-4 h following the recommended protocols. Absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm was read on a microplate fluoresce reader (BioTek, Winoosk, VT) and recorded. Wells containing Harmaline or ACV at each concentration in media without cells served as a blank to ensure that the drugs themselves were not registering fluorescence.

2.4. Koi infection and Drug Treatment

Koi at 5-8 cm (3-4 months old), including both males and females, were acquired from a local distributor in Oregon, quarantined for 10 days, and tested free of CyHV-3 before infection. CyHV-3 infection was carried out by immersing koi in 1× PBS containing ~1 × 10

3 PFU/ml of CyHV-3 for 30 min and then returning CyHV-3 exposed koi to tanks with one-way flow-through water and air. All treatments were given via immersion in water containing 20µM ACV, or 10µM HAL, or 20 µM HAL or dilution media DMSO as vehicle control for 3 - 4 hours on days 1‒5 post-infection. Additional koi at similar ages served as uninfected controls. The koi were infected under stress temperature conditions as reported previously [

8,

24]. All koi were kept in 4-foot diameter tanks at the Oregon State University John L. Fryer Aquatic Animal Health Lab following Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines (IACUC-2021-0194). The koi were euthanized with 250mg/L (PPM) MS-222 at the end of the studies.

2.5. CyHV-3 Reactivation and Harmaline Treatment in CyHV-3 Latently Infected Koi

Koi at 8-12 inches (4–6-year-old) were infected with CyHV-3 approximately three years ago, and were all tested positive for CyHV-3 latency. CyHV-3

+ Koi were stressed as reported previously [

8]. Koi were given 100µL of 20µM Harmaline or 100µL of PBS daily for 5 days immediately after temperature increase. Four CyHV-3

+ koi were used as control and were not subjected to temperature stress or treatment. Blood samples from treated or untreated control groups were taken on days 1, 3, 6, and 9 post-temperature stress as shown in Fig. 6A.

2.6. Total White Blood Cell (WBC) Isolation and Total DNA Extraction

WBCs were isolated from approximately 2mL of whole blood from each koi by Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare) as described previously [

25]. Total DNA of KHV-infected KF-1 cells and WBCs were isolated by EZNA Tissue DNA extraction kit (Omega Bio-tec), and the total DNA was eluted in 75μL of TE buffer (10 mM Tris–HCL [pH 8.0]–1 mM EDTA). The KHV genome within KHV-infected KF-1 cells and WBCs was estimated by real-time PCR using 5μL of the DNA extract as reported previously [

8].

2.7. CyHV-3 DNA Real-Time PCR

The standard curve of real-time PCR was made with a DNA template amplified from CyHV-3-U DNA that was cloned into a TOPO 2.1 PCR vector (Invitrogen), as reported previously [

8]. The copy number of CyHV-3 DNA was calculated from the equation derived from the standard curve, y = -1.267ln(x) + 37.202, where x is the Ct value. The PCR reaction was performed as previously described [

8]. The primers used in real-time PCR were CyHV-3 86F and CyHV-3 163R, and Taqman probe CyHV-3 109P as previously developed by Gilad et al. [

4].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Two-way ANOVA with multiple comparison tests was used to analyze virus titer, CyHV-3 genome copy numbers, and koi survival.

3. Results

3.1. HAL Reduces CyHV-3 Replication In Vitro

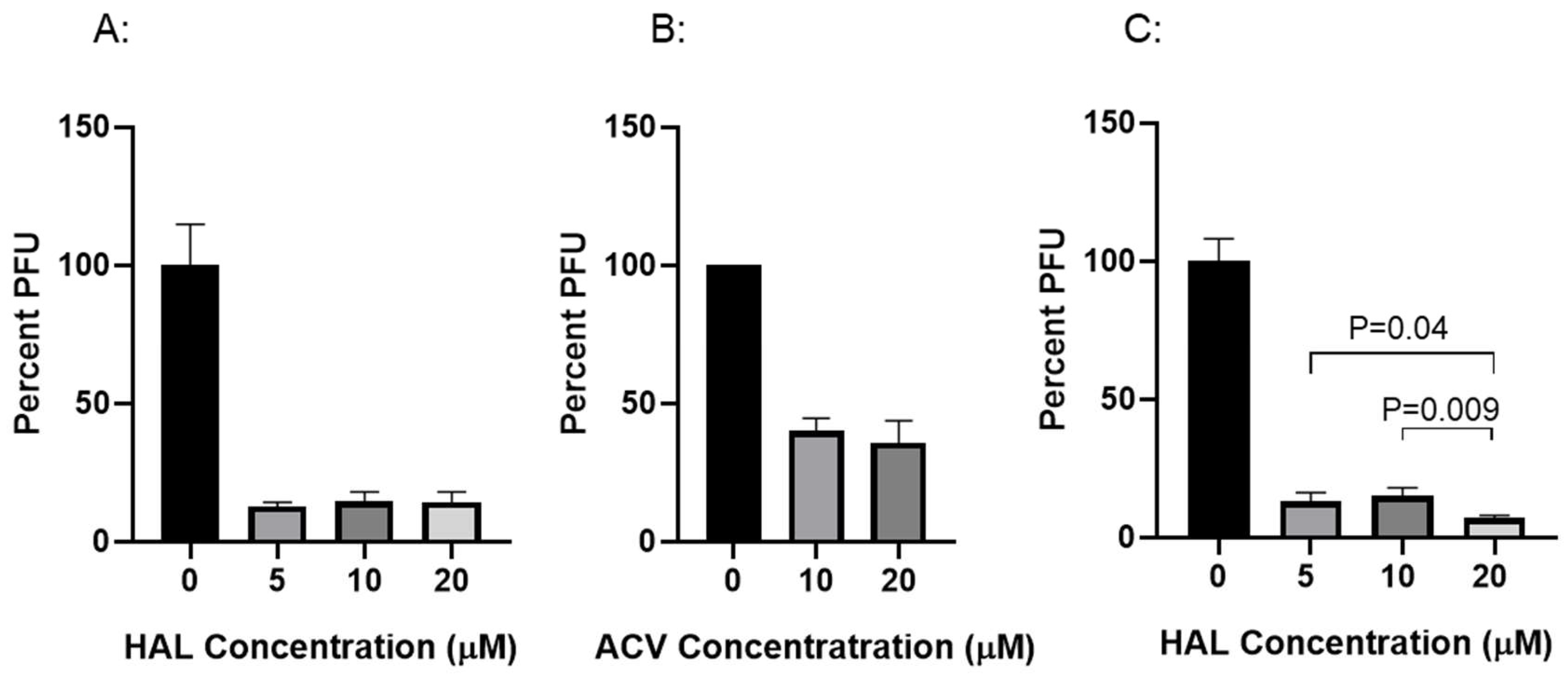

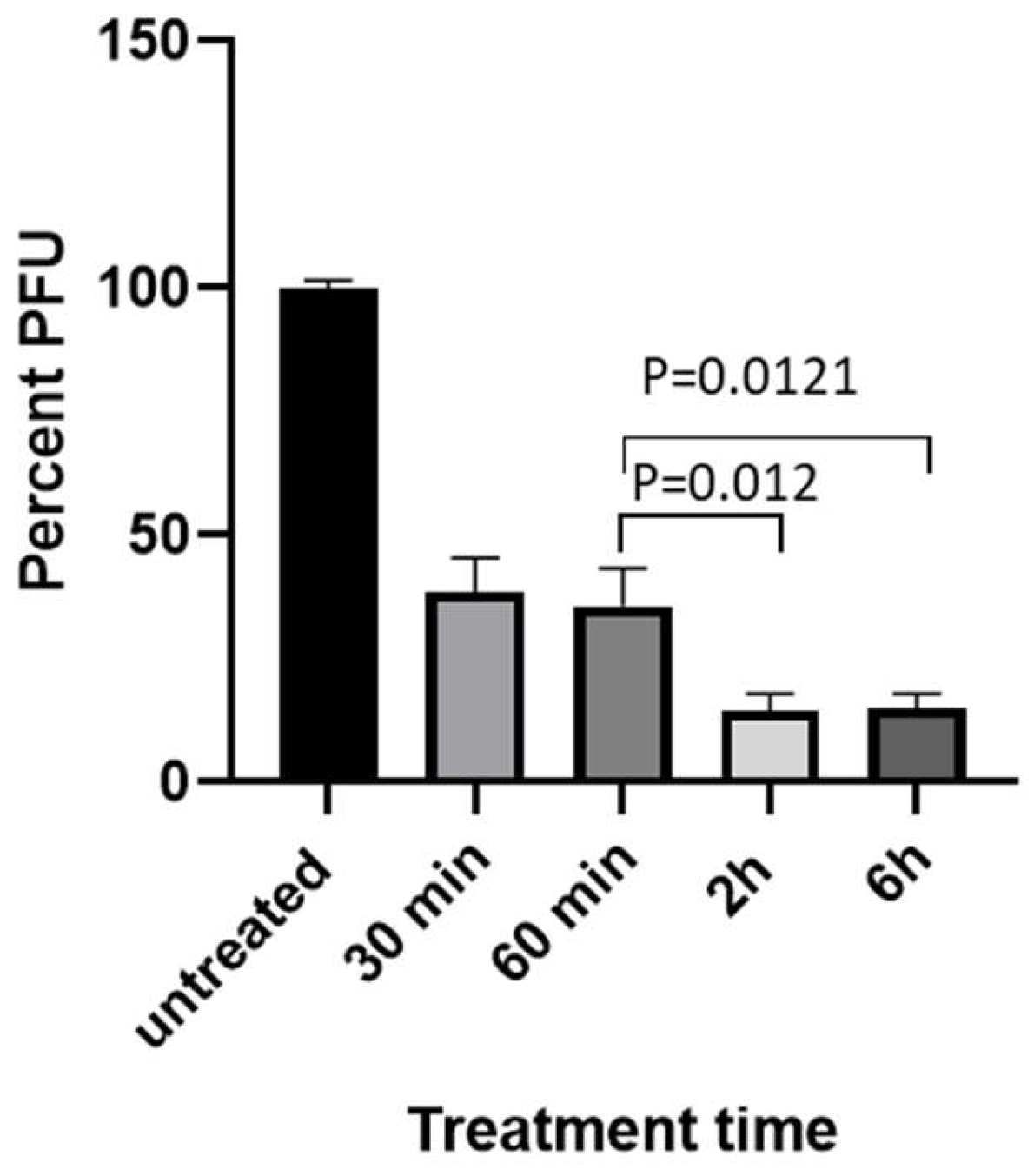

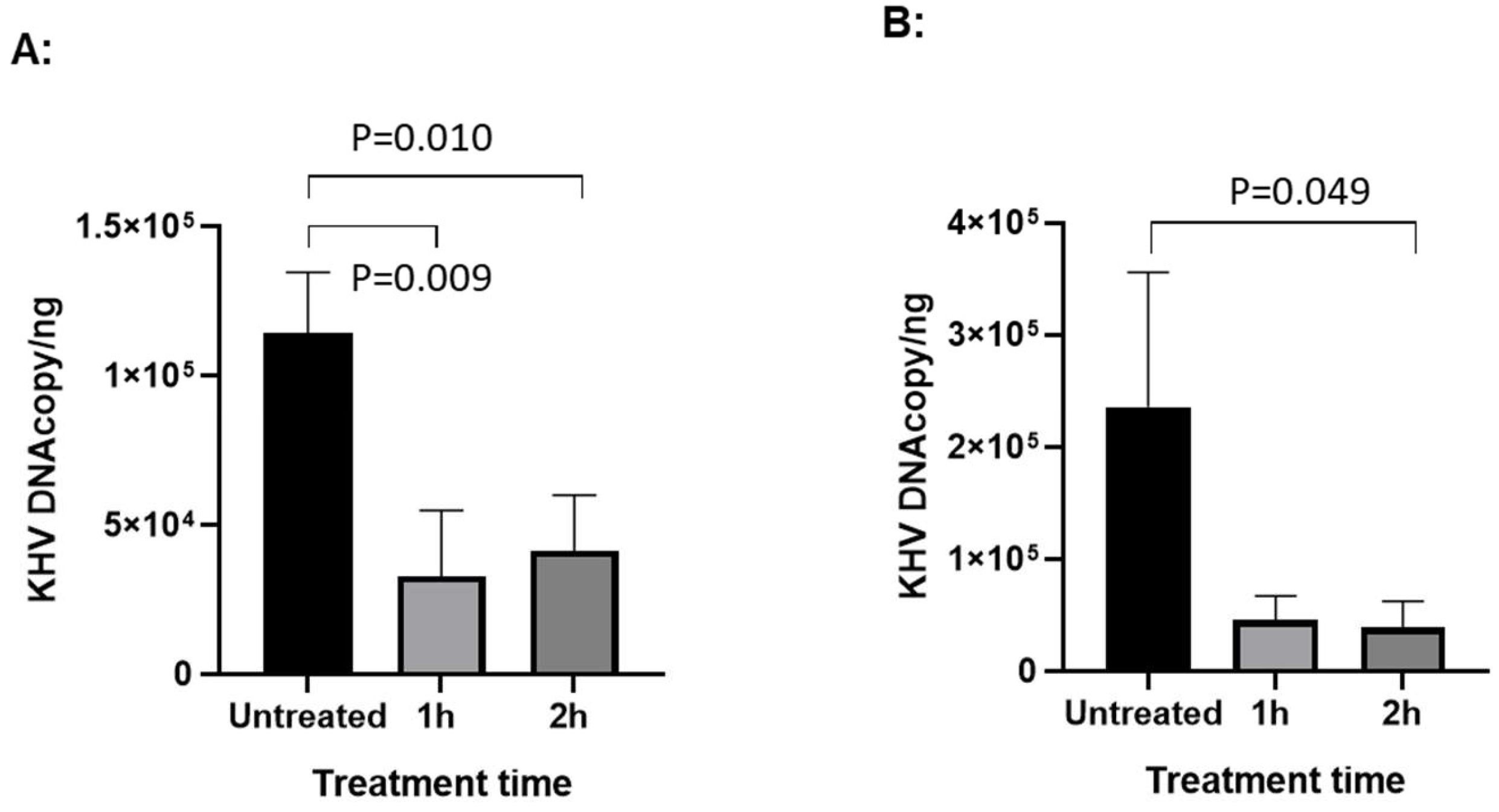

To determine whether HAL has anti-viral effect against CyHV-3 replication in vitro, koi fin cells (KF-1) were infected with CyHV-3-U at ~1 × 103 PFU/plate for 1 h; then the infected cells were treated with HAL at 5µM, 10µM, 20µM for 2 h, respectively. The PFU was counted on day 10 post-infection. As shown in Fig. 1A, nearly 90% inhibition of CyHV-3 plaque formation was observed in cells treated with 5µM, 10µM, 20µM for 2h. Around 50% inhibition was observed in cells treated with ACV at 10 or 20 µM for 2h following 1h post-infection (Fig. 1B). In addition, infected cells treated for 6h at 5µM or 10µM, did not significantly enhance HAL antiviral activity, except infected cells treated with 20 µM (Fig. 1C). Cells treated with 20µM HAL for 6h reduced CyHV-3 PFU significantly than those treated with 5µM and 10µM with p value at 0.04 and 0.009, respectively (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that HAL at 5 µM is as effective as 20 µM against CyHV-3 replication within 2h treatment time. To determine the minimal treatment time needed for blocking CyHV-3 replication, KF-1 cells were infected similarly as above and treated with 10 µM HAL for 30 min, 60 min, 2h, and 6h respectively, immediately after CyHV-3 absorption. As shown in Fig 2, the 30, 60 min, 2h, and 6 h treatments all significantly reduced virus replication. There was no difference between 30 min vs 60 min, and 2h vs 6h, but there were significant differences between the 60 min and 2h treatment, 60 min and 6h treatment, with p values at 0.012 and 0.0121, respectively. Therefore, HAL treatment at 2h provided the optimal antiviral activity. To find when the treatment is still effective after CyHV-3 exposure, HAL was introduced to the CyHV-3 infected cells at 3 and 5 dpi, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, HAL treatment at 10µM was only effective when the drug was given before 3 dpi (Fig. 3A), while the HAL treatment at 20µM for 2h was effective when the drug was given before 5 dpi (Fig. 3B). Similar HAL treatment given at 7dpi was no longer effective when the drug was given at 7 dpi (data not shown). These results indicate that HAL is only effective against CyHV-3 during the early phase of infection.

Figure 1.

Percentage of CyHV-3 plaque formation units (PFU) in the presence of HAL and ACV at different treatment concentrations. Plates seeded with KF-1 cells were treated with HAL (A and C) and ACV (B) in triplicates following an hour absorption with CyHV-3-U at 1000-2000 PFU/plate. Each set was treated with HAL at 5 µM, 10 µM, and 20 µM or ACV at 10 µM and 20 µM for 2h (A and B) or 6h (C), respectively. After the treatment, each plate was washed once with PBS and covered with 3% methylcellulose overlay media. Plaque formation units (PFU) were counted on day 10 post-infection. A significant statistical difference treatment concentration is marked with a p-value calculated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

Figure 1.

Percentage of CyHV-3 plaque formation units (PFU) in the presence of HAL and ACV at different treatment concentrations. Plates seeded with KF-1 cells were treated with HAL (A and C) and ACV (B) in triplicates following an hour absorption with CyHV-3-U at 1000-2000 PFU/plate. Each set was treated with HAL at 5 µM, 10 µM, and 20 µM or ACV at 10 µM and 20 µM for 2h (A and B) or 6h (C), respectively. After the treatment, each plate was washed once with PBS and covered with 3% methylcellulose overlay media. Plaque formation units (PFU) were counted on day 10 post-infection. A significant statistical difference treatment concentration is marked with a p-value calculated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

Figure 2.

Percentage of CyHV-3 PFU in the presence of HAL for different time. KF-1 cells were infected as described in Fig. 1 and then treated with 10 µM for 30, 60 min, 2h and 6, respectively, immediately after one hour virus absorption. After the treatment, each plate was washed once with PBS and covered with 3% methylcellulose overlay media. Each treatment time was repeated in triplicates (n=3). PFU was counted on day 10 post-infection. A significant statistical difference between different treatment times is marked with a p-value calculated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

Figure 2.

Percentage of CyHV-3 PFU in the presence of HAL for different time. KF-1 cells were infected as described in Fig. 1 and then treated with 10 µM for 30, 60 min, 2h and 6, respectively, immediately after one hour virus absorption. After the treatment, each plate was washed once with PBS and covered with 3% methylcellulose overlay media. Each treatment time was repeated in triplicates (n=3). PFU was counted on day 10 post-infection. A significant statistical difference between different treatment times is marked with a p-value calculated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

Figure 3.

qPCR of CyHV-3 in KF-1 cells treated with HAL on different days post-infection (dpi). KF-1 cells were infected as above and then treated with HAL at 10µM for 1h and 2h on 3 dpi (A) and 5dpi (B), respectively. CyHV-3 genome copy number was estimated by qPCR using total DNA isolated from infected cells on day 10 post-infection as described previously (11). A significant statistical difference between different treatments is marked with a p-value calculated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

Figure 3.

qPCR of CyHV-3 in KF-1 cells treated with HAL on different days post-infection (dpi). KF-1 cells were infected as above and then treated with HAL at 10µM for 1h and 2h on 3 dpi (A) and 5dpi (B), respectively. CyHV-3 genome copy number was estimated by qPCR using total DNA isolated from infected cells on day 10 post-infection as described previously (11). A significant statistical difference between different treatments is marked with a p-value calculated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

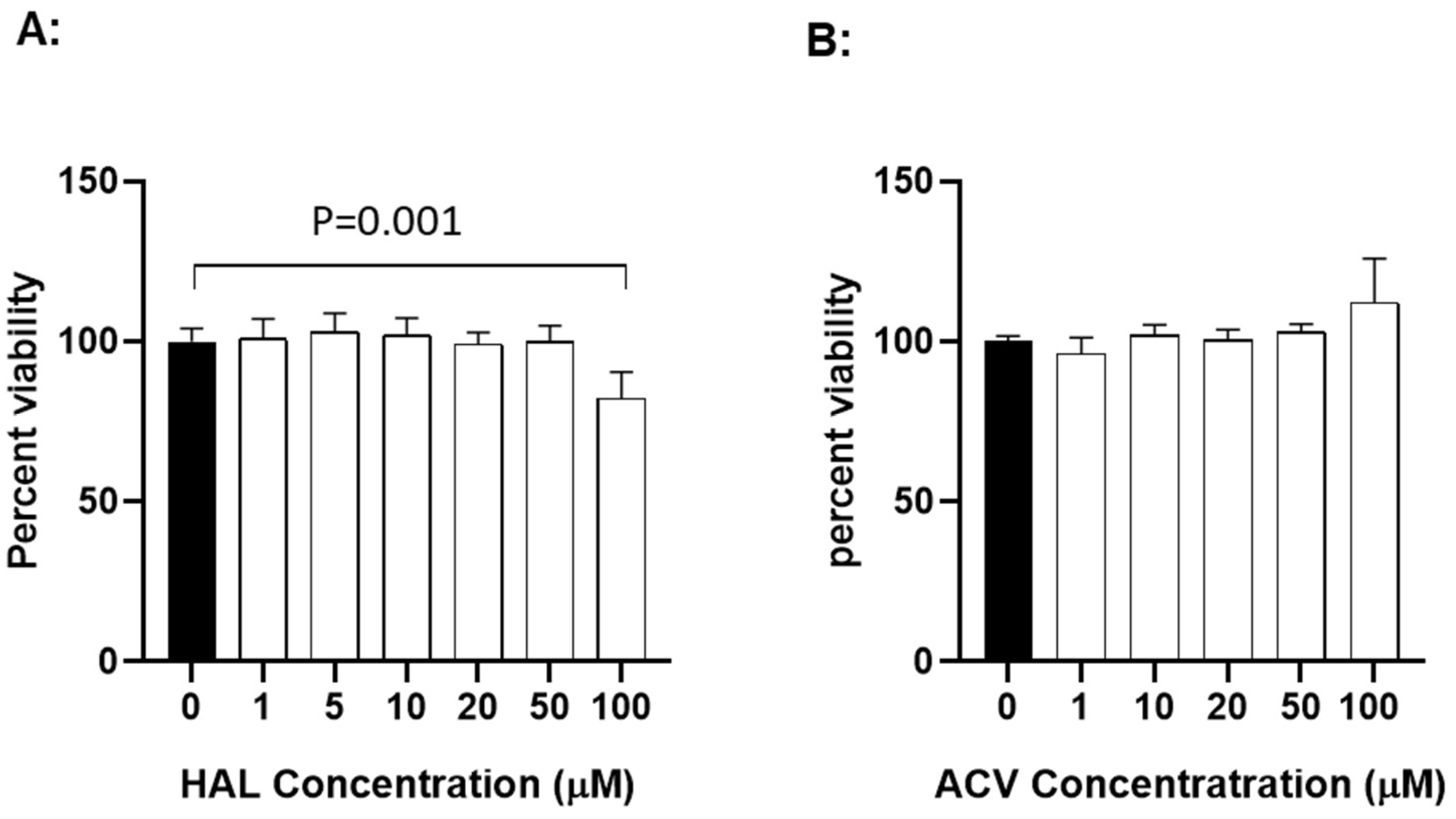

3.2. Cytotoxicity of HAL

To determine whether HAL is cytotoxic to KF-1 cells, the cell viability was evaluated after exposure to HAL at different concentrations for 24 h. Fig. 4A shows viability results from KF-1 cells treated with HAL over a concentration of 1 to 100 µM for 24 h. No significant difference in viability was apparent between mock-treated and 24 h treated cells with up to 50 µM HAL in KF-1 cells. However, a statistically significant difference was noticeable between mock-treated and 100 µM HAL-treated KF-1 cells (p=0.001). Since 10 µM and 20 µM HAL is non-toxic to KF-1 cells and can block about 90% of 1 × 103 PFU CyHV-3/plate infection in vitro, these two concentrations were selected for the in vivo study. ACV cytotoxicity was measured similarly to HAL in KF1 cells. No apparent cytotoxicity was observed in KF-1 cells treated with ACV at 1-100µM for 24 h (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

The cytotoxicity of HAL (A) and ACV (B) in vitro. KF-1 cells were incubated with the indicated concentration of HAL or ACV for 24h. The treatment was then removed, and the cells were washed once with PBS and further incubated for 24 h in tissue culture media with 5% FBS and antibiotics as described in the materials and methods. Cell viability was evaluated with XTT cell viability kit III (PromoKine) and expressed as a percentage of the mock-treated control (n = 3). A significant statistical difference between the mock-treated control (0) and 100 µM HAL is marked above the line with a p-value calculated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

Figure 4.

The cytotoxicity of HAL (A) and ACV (B) in vitro. KF-1 cells were incubated with the indicated concentration of HAL or ACV for 24h. The treatment was then removed, and the cells were washed once with PBS and further incubated for 24 h in tissue culture media with 5% FBS and antibiotics as described in the materials and methods. Cell viability was evaluated with XTT cell viability kit III (PromoKine) and expressed as a percentage of the mock-treated control (n = 3). A significant statistical difference between the mock-treated control (0) and 100 µM HAL is marked above the line with a p-value calculated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

3.3. HAL Reduced Mortality in CyHV-3 Infected Younger Koi

To determine whether a HAL immersion bath treatment could reduce mortality in 3-4-month-old koi, four groups of koi were infected with ~1 × 10

3 PFU/ml of CyHV-3-U for 30 min in an immersion bath. Following CyHV-3 exposure, the tank temperature was increased at 2°C per day from day 1 post-infection up to 22°C on day 5 post-infection; the tank temperature was maintained at 22 °C for two days, then was decreased 2°C per day until 14 °C. CyHV-3- infected koi at 3-4 month old will have 80-90% mortality under those temperature changes [

26]. From days 1 to 5 post-infection, 20 koi per group were treated daily in an immersion bath containing 10µM HAL, 20µM HAL, 20µM ACV, or dilution media (DMSO) for 3-4 hours, respectively. Koi were considered dead when floating without gill movement in the water or sunken to the bottom of the tank. The DMSO-treated group had ~80% mortality by day 15 post-infections, and mortality started as early as day 5 post-infection (Fig. 5). However, the 10µM HAL-treated group had only about ~40% mortality by day 15 post-infection and mortality started two days later than those in the DMSO-treated group. The ACV-treated group had about 78% mortality by day 15 post-infection, slightly lower than the DMSO-treated group, but no significant reduction in mortality at the end of the experiment (Fig 5). ACV treatment resulted in a one-day delay in mortality compared with the DMSO-treated group. Interestingly, the 20uM HAL-treated group had a similar outcome as those treated with ACV.

Figure 5.

Schematic of the infection-treatment protocol and survival of Koi infected with CyHV-3 in different groups. A: 3-4-month-old koi were infected with 1 × 103 PFU/ml for 30 min, followed by water temperature change on different dpi and treatment for five consecutive days with HAL, ACV, and dilution medium (DMSO) as indicated. The “+” stands for days that Koi were treated with 10µM HAL, 20µM HAL, 20µM ACV, or DMSO (control), respectively. B: The percentage survival of koi infected with CyHV-3 in four different treatment tanks with 10µM HAL, 20µM HAL, 20µM ACV, or DMSO (control), respectively. A significant statistical difference between the DMSO-treated and 10µM HAL-treated is marked with a p-value calculated using a two-way ANOVA.

Figure 5.

Schematic of the infection-treatment protocol and survival of Koi infected with CyHV-3 in different groups. A: 3-4-month-old koi were infected with 1 × 103 PFU/ml for 30 min, followed by water temperature change on different dpi and treatment for five consecutive days with HAL, ACV, and dilution medium (DMSO) as indicated. The “+” stands for days that Koi were treated with 10µM HAL, 20µM HAL, 20µM ACV, or DMSO (control), respectively. B: The percentage survival of koi infected with CyHV-3 in four different treatment tanks with 10µM HAL, 20µM HAL, 20µM ACV, or DMSO (control), respectively. A significant statistical difference between the DMSO-treated and 10µM HAL-treated is marked with a p-value calculated using a two-way ANOVA.

3.4. HAL Reduced CyHV-3 Reactivation from Temperature Stress

As we reported previously, CyHV-3 reactivation in latently infected Koi can be induced by temperature stress [

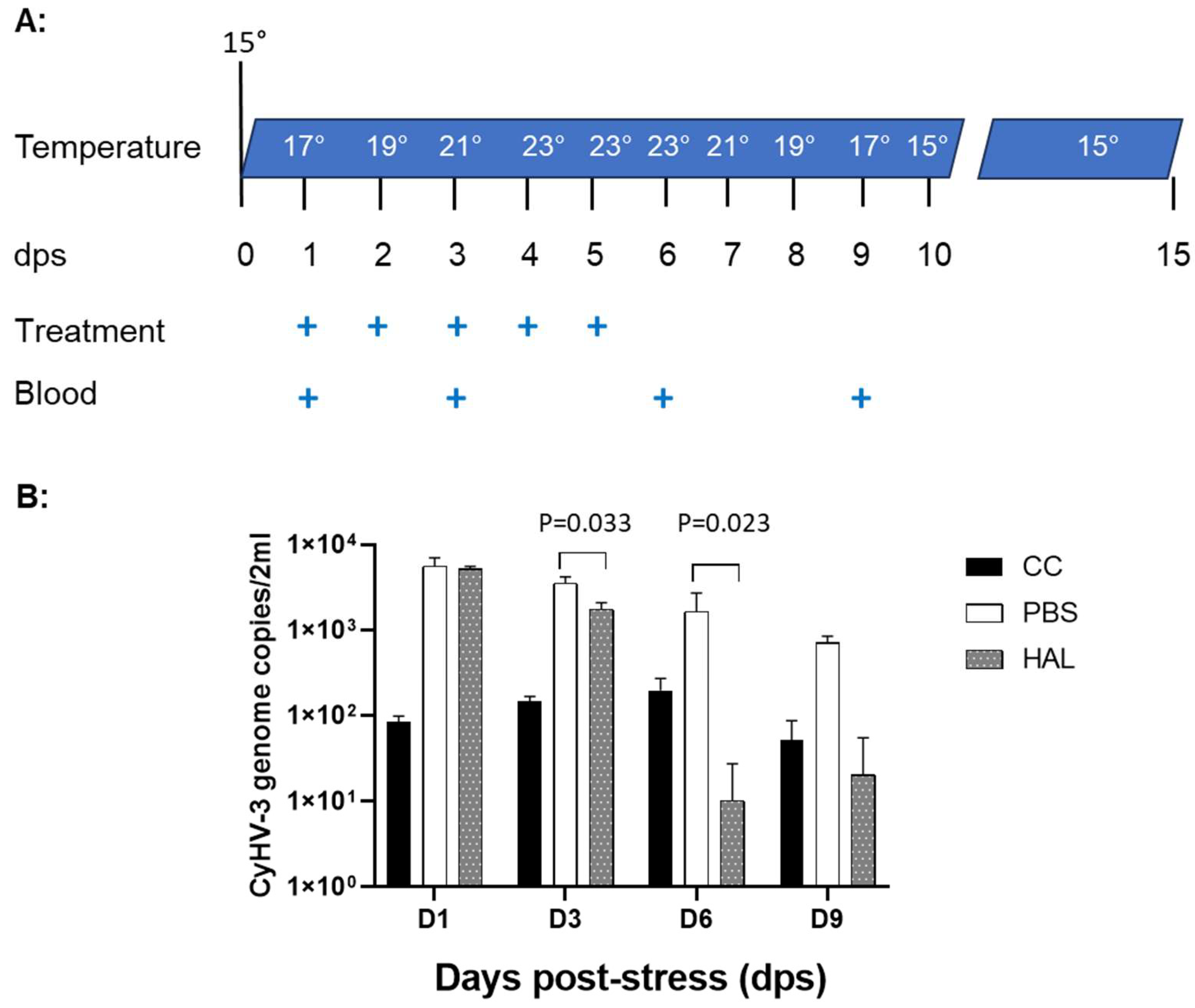

8]. CyHV-3 DNA replication in the peripheral white blood cells can be detected between day 1 and 10 post-temperature stresses. To determine whether HAL can reduce CyHV-3 reactivation from latency, CyHV-3 latently infected Koi, at 8-12 inches (4-6 years old), were treated with HAL intramuscularly (IM) during temperature stress (Fig 6A). Four koi per group were injected IM with 100µL of 20µM Harmaline or 100µL of PBS (treatment control) daily for 5 days on day 1 post-temperature stress, respectively. Another four-control koi were not stressed or treated. Blood samples of treated or untreated koi were taken on days 1, 3, 6, and 9 post-temperature stress (Fig. 6A). CyHV-3 normally becomes latent in B cells; low levels of CyHV-3 DNA can be detected by qPCR in the total peripheral white blood cells (WBC) during latency. Following 24h post-temperature stress, there was a significant CyHV-3 DNA increase in both PBS and HAL-treated koi (Fig. 6B). However, CyHV-3 DNA levels were significantly lower on days 3 and 6 post-temperature stress in groups treated with HAL than those treated with PBS with p value at 0.033 on 3 dps, and 0.023 on 6 dps respectively. There were no significant differences in CyHV-3 genome copies in the WBC from stressed and non-stressed groups by day 9 post-stress. These results suggest HAL can lower the CyHV-3 reactivation rate in latently infected Koi.

Figure 6.

Schematic of treatment protocol during temperature stress and CyHV-3 genome copy numbers in peripheral white blood cells. A. The water temperature changes as indicated on different days post-stress (dps). The “+” stands for dps when treatment was given or blood was sampled. The treatment was given IM at 100µL of 20µM HAL or 100µL of PBS. B: CyHV-3 genome copy numbers were estimated by qPCR using total DNA of WBCs collected on days 1, 3, 6, and 9 post-stress. The number represents the average CyHV-3 genome copies per 2ml from each group. The “cc” stands for koi that were not stressed or treated. A significant statistical difference between the HAL-treated and PBS-treated groups on 3 and 6 dps is marked with a p-value calculated using a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

Figure 6.

Schematic of treatment protocol during temperature stress and CyHV-3 genome copy numbers in peripheral white blood cells. A. The water temperature changes as indicated on different days post-stress (dps). The “+” stands for dps when treatment was given or blood was sampled. The treatment was given IM at 100µL of 20µM HAL or 100µL of PBS. B: CyHV-3 genome copy numbers were estimated by qPCR using total DNA of WBCs collected on days 1, 3, 6, and 9 post-stress. The number represents the average CyHV-3 genome copies per 2ml from each group. The “cc” stands for koi that were not stressed or treated. A significant statistical difference between the HAL-treated and PBS-treated groups on 3 and 6 dps is marked with a p-value calculated using a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

4. Discussion

Koi are colored variants of carp, valuable ornamental fish collected by many koi hobbyists throughout the world. CyHV-3 is the most pathogenic virus in koi and common carp, especially in younger koi [

27,

28,

29]. Currently, no effective antiviral drugs or vaccines have been developed against CyHV-3 infection in koi [

30,

31,

32]. Anti-herpesvirus drugs, such as acyclovir (ACV), acyclovir monophosphate (ACV-MP), and Arthrospira platensis, have been investigated against CyHV-3 and were found to have limited effects against CyHV-3 infection

in vitro and in

vivo [

33,

34,

35]. Our study also demonstrated that ACV has limited protection against KHV infection

in vitro and

in vivo (Fig. 1B, Fig. 5). Therefore, antiviral drugs or alternative medicines are needed to control CyHV-3 infection in koi. The analogous β-carboline alkaloids, such as harmaline (HAL), and harmine (HAR) possess a variety of biological properties that have inhibitory activity against acetylcholinesterase (AChE), monoamine oxidase (MAO), and myeloperoxidase (MPO). HAR has been shown to be neuroprotective, anticancer, antimicrobial, and antiviral [

13,

36]. HAR, isolated from the seeds of the medicinal plant Peganum harmala L., has been used for thousands of years in the Middle East and China. Recently, HAR derivatives have been reported to have antiviral activities against various viruses, such as HSV-1, HSV-2, Newcastle disease virus, Dengue virus, and polio virus [

19,

20,

22,

37,

38,

39]. Here, we demonstrated that HAL, which is similar to HAR in structure, also has anti-viral activities against CyHV-3

in vitro and

in vivo.

Both HAR and HAL can be found in various plants, such as Syrian rue and ayahuasca, which have been used in traditional medicine for centuries. Previous studies have shown HAR has antiviral properties against HSV-1 and HSV-2, HIV, and coronavirus [

19,

22,

38]. Although HAL has not been tested directly against herpesvirus

in vitro, it has a similar structure to HAR and has better bioavailability and solubility than HAR [

14]; therefore, HAL was tested in this study. Our study found HAL is more soluble than HAR and has anti-KHV activity at relatively low concentrations, such as 5, 10, and 20µM,

in vitro (Fig. 1A). Those concentrations were all below the toxic concentration (Fig. 4). Another interesting finding is when infected KF-1 cells were treated with 5µM HAL for 30 min, HAL has relative higher antiviral activity than those treated with 10µM or 20µM (Supplemental Fig. 1). The difference between 5µM and 10µM is statistically significant, while KF-1 cells treated with 20µM HAL has no significant difference to KF-1 cells treated with 5µM HAL. This suggests that the treatment time and HAL concentration may have different effects during CyHV-3 replication.

It was reported that HSV-1 infection induces the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

40,

41], and oxidative stress was found to favor herpesvirus replication during early stage of replication [

42]. Therefore, antioxidants were shown to have antiviral activities against HSV-1 infections [

43]. It is reasonable to speculate that HAL may interfere with oxidative stress during viral replication since HAL, like HAR, is an inhibitor of MAO and MPO that are associated with ROS production [

21]. Here, we found that the most effective treatment time is between 2h and 6h following 1-hour post-infection; longer treatment duration seems to have no significant effect against KHV replication (Fig. 2). It suggests HAL may interfere with viral replication by decreasing oxidative stress during the early phase of the infection.

Mortality associated with KHV infection in koi is age- and temperature-dependent [

26]. Koi, at younger ages are more susceptible to KHV infection (2). Our previous study found that the infection of around 6-month-old Koi with CyHV-3 at about 1 × 10

3 PFU/mL via immersion did not cause any mortality [

26]. However, Infection of the same age groups of koi with the same infection dose by increasing water temperature daily at 2°C per day from 15°C to 23°C could lead to 80-90% mortality within 10 days post-infection (26). In this study, we infected similar age group of Koi and exposed them to similar heat stress as reported previously (26), we found 10µM HAL-treated Koi had significant higher survival rate than the rate in control group (MDSO-treated group) (Fig. 5). No significant protection was observed in Koi treated with ACV, which is in agreement with our previous report [

26]. Another interesting finding is that the 20µM HAL-treated group had similar survival as those treated with the 20µM ACV-treated group. This could be a similar effect seen in Supplemental Fig. 1. The HAL antiviral treatment effect is complicated by treatment time and treatment concentration. More studies will be needed to determine optimal concentration and treatment time. This could mean that HAL bioactivity is limited to 10µM, and an extra amount or longer treatment time may have a negative effect on the host. However, this study demonstrated HAL at 10µM can decrease KHV replication and reduce mortality associated with the infection.

Our previous studies have demonstrated that CyHV-3 becomes latent in WBC, especially the IgM+ positive B cells [

25]. CyHV-3 reactivation can be induced by daily temperature increasing at 2°C per day from 15°C to 23°C, then maintained at 23°C for 3-5 days [

8]. A two- to three-fold KHV genome copy increase can be detected between day 3 and 9 post-temperature stress [

11]. Similarly, a 2-3-fold CyHV-3 DNA increase was detected between days 1 and 6 post-temperature stress in koi treated with PBS (Fig. 6B). However, CyHV-3 DNA increase was only observed between day 1 and 3 post-temperature stress in those treated HAL. By day 6 post-temperature stress, HAL treated koi had a significant lower CyHV-3 DNA in total WBC. The HAL treatment effect was noticeable on days 3 and 6 post-temperature stress. This suggests HAL treatment can lower CyHV-3 reactivation if they were treated with HAL via IM. This treatment could be used in koi shipping to prevent CyHV-3 from reactivating due to shipping stress.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Percentage of CyHV-3 PFU in the presence of HAL at different concentrations. KF-1 cells treated with HAL for 30 min at the indicated concentration. For each treatment, three plates were infected with CyHV-3-U at 1000-2000 PFU/plate first, and then each plate was treated with HAL at 5 µM, 10 µM and 20 µM for 30 min, respectively. PFU was quantified on day 10 post-infection. A significant statistical difference between different treatment concentration is marked with a p-value calculated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test

Author Contributions

C.M. and K.L made equal contributions to this paper. Conceptualization, L.J; methodology, L.J., X.W. and R.M.-C.; software, L.J.; validation, C.M., K.L. and S.M..; formal analysis, L.J., C. M.. and K.L.; investigation, C.M., K.L., S.M., X.W., and R.M.C.; resources, L.J.; data curation, K.L. and L.J.; writing—original draft preparation, L.J.; writing—review and editing, K.L. and L.J.; visualization, L.J.; supervision, L.J.; project administration, L.J.; funding acquisition, C.M., K.L., and L.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Associated Koi Clubs of America and CCVM DVM summer research grant at Oregon State University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines (IACUC), and approved by the IACUC Review Board of Oregon State University (protocol code IACUC-2021-0194 on 2 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

We thank the Associated Koi Clubs of America for funding this study. C.M., K.L. and S.M. were supported by CCVM DVM summer research grant. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Associated Koi Clubs of America.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Gilad, O.; Yun, S.; Andree, K.B.; Adkison, M.A.; Zlotkin, A.; Bercovier, H.; Eldar, A.; Hedrick, R.P. Initial characteristics of koi herpesvirus and development of a polymerase chain reaction assay to detect the virus in koi, Cyprinus carpio koi. Dis Aquat Organ 2002, 48, 101-108. [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, R.P.; Gilad, O.; Yun, S.; Spangenberg, J.V.; Marty, G.D.; Nordhausen, R.W.; Kebus, M.J.; Bercovier, H.; Eldar, A. A Herpesvirus Associated with Mass Mortality of Juvenile and Adult Koi, a Strain of Common Carp. J Aquat Anim Health 2000, 12, 44-57. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Chen, C.Y.; Tsai, M.A.; Wang, P.C.; Hsu, J.P.; Chern, R.S.; Chen, S.C. Koi herpesvirus epizootic in cultured carp and koi, Cyprinus carpio L., in Taiwan. J Fish Dis 2011, 34, 547-554. [CrossRef]

- Gilad, O.; Yun, S.; Zagmutt-Vergara, F.J.; Leutenegger, C.M.; Bercovier, H.; Hedrick, R.P. Concentrations of a Koi herpesvirus (KHV) in tissues of experimentally infected Cyprinus carpio koi as assessed by real-time TaqMan PCR. Dis Aquat Organ 2004, 60, 179-187. [CrossRef]

- Eide, K.; Miller-Morgan, T.; Heidel, J.; Bildfell, R.; Jin, L. Results of total DNA measurement in koi tissue by Koi Herpes Virus real-time PCR. Journal of virological methods 2011, 172(1-2):81-84. [CrossRef]

- Waltzek, T.B.; Kelley, G.O.; Stone, D.M.; Way, K.; Hanson, L.; Fukuda, H.; Hirono, I.; Aoki, T.; Davison, A.J.; Hedrick, R.P. Koi herpesvirus represents a third cyprinid herpesvirus (CyHV-3) in the family Herpesviridae. J Gen Virol 2005, 86(Pt 6):1659-1667. [CrossRef]

- St-Hilaire, S.; Beevers, N.; Joiner, C.; Hedrick, R.P.; Way, K. Antibody response of two populations of common carp, Cyprinus carpio L., exposed to koi herpesvirus. J Fish Dis 2009, 32, 311-320. [CrossRef]

- Eide, K.E.; Miller-Morgan, T.; Heidel, J.R.; Kent, M.L.; Bildfell, R.J.; Lapatra, S.; Watson, G.; Jin, L. Investigation of koi herpesvirus latency in koi. Journal of virology 2011, 85, 4954-4962. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.R.; Bently, J.; Beck, L.; Reed, A.; Miller-Morgan, T.; Heidel, J.R.; Kent, M.L.; Rockey, D.D.; Jin, L. Analysis of koi herpesvirus latency in wild common carp and ornamental koi in Oregon, USA. J Virol Methods 2013, 187, 372-379. [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Adrianti, D.N.; Lasmika, N.L.A.; Ali, M. Detection of koi herpesvirus in healthy common carps, Cyprinus carpio L. Virusdisease 2018, 29, 445-452. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chen, S.; Russell, D.S.; Lohr, C.V.; Milston-Clements, R.; Song, T.; Miller-Morgan, T.; Jin, L. Analysis of stress factors associated with KHV reactivation and pathological effects from KHV reactivation. Virus research 2017, 240, 200-206. [CrossRef]

- Eide, K.E.; Miller-Morgan, T.; Heidel, J.R.; Kent, M.L.; Bildfell, R.J.; Lapatra, S.; Watson, G.; Jin, L. Investigation of koi herpesvirus latency in koi. Journal of virology 2011, 85, 4954-4962. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Teng, L.; Liu, W.; Cheng, X.; Jiang, B.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C. Interspecies metabolic diversity of harmaline and harmine in in vitro 11 mammalian liver microsomes. Drug Test Anal 2017, 9, 754-768. [CrossRef]

- Li SP, Wang YW, Qi SL, Zhang YP, Deng G, Ding WZ, Ma C, Lin QY, Guan HD, Liu W et al. Analogous beta-Carboline Alkaloids Harmaline and Harmine Ameliorate Scopolamine-Induced Cognition Dysfunction by Attenuating Acetylcholinesterase Activity, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Mice. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 346.

- Gonzalez, M.M.; Vizoso-Pinto, M.G.; Erra-Balsells, R.; Gensch, T.; Cabrerizo, F.M. In Vitro Effect of 9,9'-Norharmane Dimer against Herpes Simplex Viruses. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25(9).

- Kobayashi JH, G.C.; Gilmore, J.; Rinehart, K.L., Jr.. Eudistomins A, D, G, H, I, J, M, N, O, P, and Q, bromo, hydroxy, pyrrolyl and iminoazepino. beta.-carbolines from the antiviral Caribbean tunicate Eudistoma olivaceum. J Am Chem Soc 1984, 106, 1526-1528.

- Wang C, Wang T, Hu R, Duan L, Hou Q, Han Y, Dai J, Wang W, Ren S, Liu H et al. 9-Butyl-Harmol Exerts Antiviral Activity against Newcastle Disease Virus through Targeting GSK-3beta and HSP90beta. Journal of virology 2023, 97, e0198422.

- Quintana, V.M.; Piccini, L.E.; Panozzo Zenere, J.D.; Damonte, E.B.; Ponce, M.A.; Castilla, V. Antiviral activity of natural and synthetic beta-carbolines against dengue virus. Antiviral research 2016, 134, 26-33.

- Chen, D.; Su, A.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Lv, X.; Xu, W.; Xu, S.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z. Harmine blocks herpes simplex virus infection through downregulating cellular NF-kappaB and MAPK pathways induced by oxidative stress. Antiviral research 2015, 123, 27-38.

- Chen, D.; Tian, X.; Zou, X.; Xu, S.; Wang, H.; Zheng, N.; Wu, Z. Harmine, a small molecule derived from natural sources, inhibits enterovirus 71 replication by targeting NF-kappaB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2018, 60, 111-120.

- Herraiz, T.; Guillen, H. Monoamine Oxidase-A Inhibition and Associated Antioxidant Activity in Plant Extracts with Potential Antidepressant Actions. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018, 4810394. [CrossRef]

- Dahal S, Clayton K, Cabral T, Cheng R, Jahanshahi S, Ahmed C, Koirala A, Villasmil Ocando A, Malty R, Been T et al. On a path toward a broad-spectrum anti-viral: inhibition of HIV-1 and coronavirus replication by SR kinase inhibitor harmine. Journal of virology 2023, 97, e0039623. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.K.; Smyth, G.K.; Greenfield, P.F. Accuracy of the endpoint assay for virus titration. Cytotechnology 1992, 8, 231-236. [CrossRef]

- St-Hilaire, S.; Beevers, N.; Way, K.; Le Deuff, R.M.; Martin, P.; Joiner, C. Reactivation of koi herpesvirus infections in common carp Cyprinus carpio. Dis Aquat Organ 2005, 67(1-2):15-23. [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.N.; Izume, S.; Dolan, B.P.; LaPatra, S.; Kent, M.; Dong, J.; Jin, L. Identification of B cells as a major site for cyprinid herpesvirus 3 latency. Journal of virology 2014, 88, 9297-9309. [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka S, Petri G, Larson K, Behnke A, Wang X, Peng M, Spagnoli S, Lohr C, Milston-Clements R, Divilov K et al. Evaluation of Histone Demethylase Inhibitor ML324 and Acyclovir against Cyprinid herpesvirus 3 Infection. Viruses 2023, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.L.; Sohn, S.G.; Bang, J.D.; Do, J.W.; Park, M.S. Ultrastructural identification of a herpes-like virus infection in common carp Cyprinus carpio in Korea. Dis Aquat Organ 2004, 61(1-2):165-168. [CrossRef]

- Minamoto, T.; Honjo, M.N.; Uchii, K.; Yamanaka, H.; Suzuki, A.A.; Kohmatsu, Y.; Iida, T.; Kawabata, Z. Detection of cyprinid herpesvirus 3 DNA in river water during and after an outbreak. Vet Microbiol 2009, 135(3-4):261-266. [CrossRef]

- Minamoto, T.; Honjo, M.N.; Kawabata, Z. Seasonal distribution of cyprinid herpesvirus 3 in Lake Biwa, Japan. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009, 75, 6900-6904. [CrossRef]

- Boutier, M.; Gao, Y.; Donohoe, O.; Vanderplasschen, A. Current knowledge and future prospects of vaccines against cyprinid herpesvirus 3 (CyHV-3). Fish Shellfish Immunol 2019, 93, 531-541. [CrossRef]

- Perelberg, A.; Ilouze, M.; Kotler, M.; Steinitz, M. Antibody response and resistance of Cyprinus carpio immunized with cyprinid herpes virus 3 (CyHV-3). Vaccine 2008, 26(29-30):3750-3756. [CrossRef]

- Embregts, C.W.E.; Tadmor-Levi, R.; Vesely, T.; Pokorova, D.; David, L.; Wiegertjes, G.F.; Forlenza, M. Intra-muscular and oral vaccination using a Koi Herpesvirus ORF25 DNA vaccine does not confer protection in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol 2019, 85, 90-98.

- Quijano Carde, E.M.; Yazdi, Z.; Yun, S.; Hu, R.; Knych, H.; Imai, D.M.; Soto, E. Pharmacokinetic and Efficacy Study of Acyclovir Against Cyprinid Herpesvirus 3 in Cyprinus carpio. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 587952. [CrossRef]

- Troszok A, Kolek L, Szczygiel J, Wawrzeczko J, Borzym E, Reichert M, Kaminska T, Ostrowski T, Jurecka P, Adamek M et al. Acyclovir inhibits Cyprinid herpesvirus 3 multiplication in vitro. J Fish Dis 2018, 41, 1709-1718. [CrossRef]

- Troszok, A.; Kolek, L.; Szczygiel, J.; Ostrowski, T.; Adamek, M.; Irnazarow, I. Anti-CyHV-3 Effect of Fluorescent, Tricyclic Derivative of Acyclovir 6-(4-MeOPh)-TACV in vitro. J Vet Res 2019, 63, 513-518.

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Yu, S. Pharmacological effects of harmine and its derivatives: a review. Arch Pharm Res 2020, 43, 1259-1275. [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, A.; Mahmoud, S.H.; Elshaier, Y.; Shama, N.M.A.; Nasr, N.F.; Ali, M.A.; El-Shazly, A.M.; Mostafa, I.; Mostafa, A. Antiviral activities of plant-derived indole and beta-carboline alkaloids against human and avian influenza viruses. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 1612.

- Benzekri, R.; Bouslama, L.; Papetti, A.; Hammami, M.; Smaoui, A.; Limam, F. Anti HSV-2 activity of Peganum harmala (L.) and isolation of the active compound. Microb Pathog 2018, 114, 291-298. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.B.; Graham, E.A.; Towers, G.H. Antiviral effect of harmine, a photoactive beta-carboline alkaloid. Photochem Photobiol 1986, 43, 21-26.

- Kavouras, J.H.; Prandovszky, E.; Valyi-Nagy, K.; Kovacs, S.K.; Tiwari, V.; Kovacs, M.; Shukla, D.; Valyi-Nagy, T. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection induces oxidative stress and the release of bioactive lipid peroxidation by-products in mouse P19N neural cell cultures. J Neurovirol 2007, 13, 416-425. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Yuan C, Zhang D, Ma Y, Ding X, Zhu G. BHV-1 induced oxidative stress contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction in MDBK cells. Vet Res 2016, 47, 47. [CrossRef]

- Arima, K.; Kakinuma, A.; Tamura, G. Surfactin, a crystalline peptidelipid surfactant produced by Bacillus subtilis: isolation, characterization and its inhibition of fibrin clot formation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 1968, 31, 488-494.

- Sutter, J.; Bruggeman, P.J.; Wigdahl, B.; Krebs, F.C.; Miller, V. Manipulation of Oxidative Stress Responses by Non-Thermal Plasma to Treat Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Infection and Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(5). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).