1. Introduction

The family Birnaviridae includes seven genera. Among these, the Aquabirnavirus, Avibirnavirus and Blosnavirus infect vertebrates, while the remaining genera, Dronavirus, Entomobirnavirus, Ronavirus and Telnavirus infect insects, rotifers, or mollusks (International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, Virus Taxonomy: 2023 Release). Notably, infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV, genus Aquabirnavirus) and infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV, genus Avibirnavirus) are extensively studied birnaviruses that primarily affect salmonids and poultry, respectively.

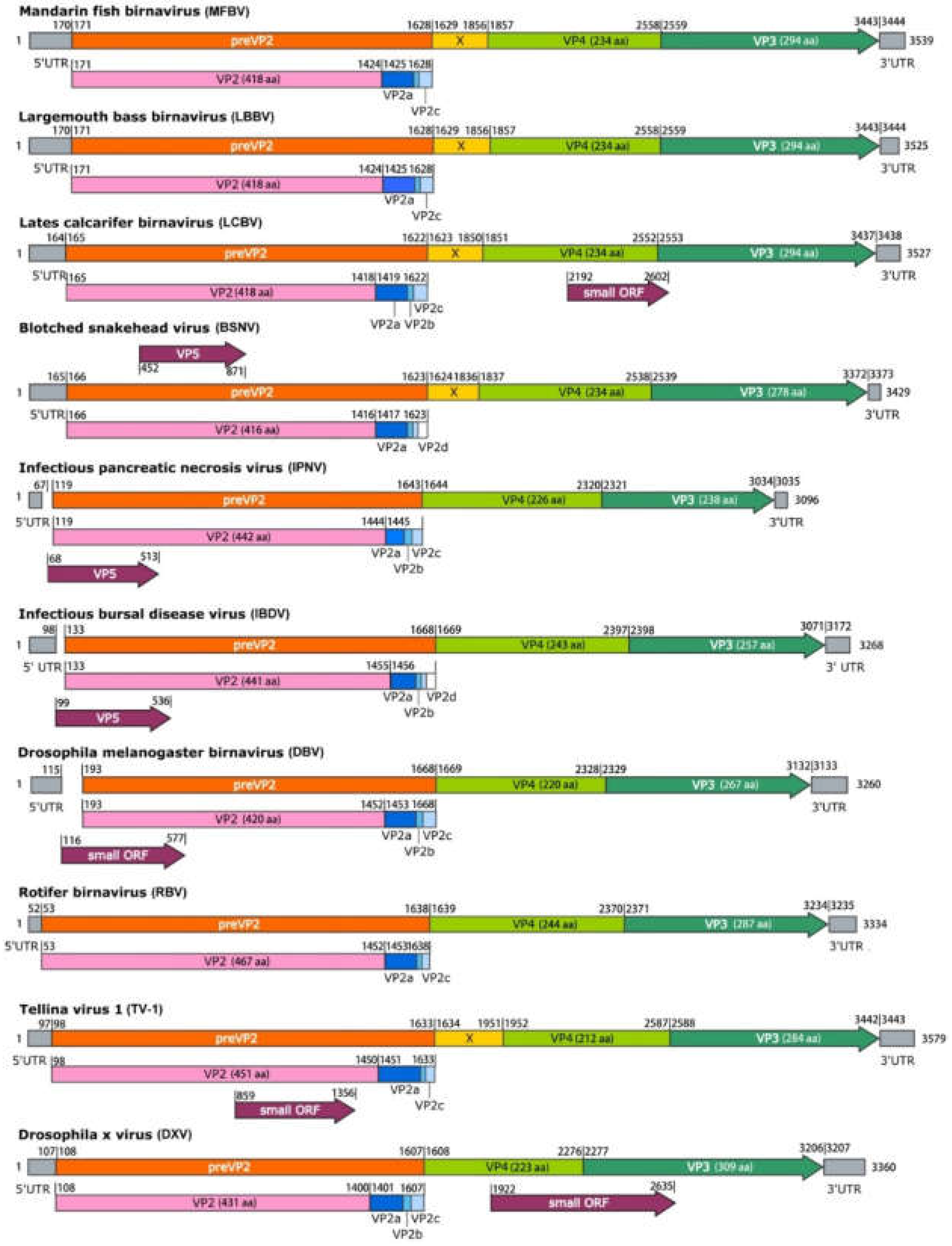

Birnaviruses have bisegmented double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genomes with a total of about 6 kbp. Segment A, approximately 3.1-3.5 kbp in length, encodes a polyprotein of VP2- (X)-VP4-VP3. The segment B, around 2.7 kbp in length, encodes the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp, VP1). The polyprotein undergoes autocatalytic cleavage by the VP4 protease, yielding in precursor VP2 (preVP2), VP4, and VP3. The preVP2 is subsequently matured by cleaving the C-terminal small peptides and then matured VP2 constitutes the capsid. While VP3 is a ribonucleoprotein [

1,

2].

Birnaviruses are non-enveloped, single-layered capsid dsRNA viruses, distinct from the double-layered capsid of most dsRNA viruses. Their capsid is icosahedron, clustered as 260 outer trimers, arranged with a triangulation number of T=13, and has a diameter of approximately 60-70nm, as observed in representative birnaviruses such as IBDV and IPNV [

3,

4].

In recent years, two novel fish birnaviruses, namely largemouth bass birnavirus (LBBV) reported in 2022 and Lates calcarifer birnavirus (LCBV) identified in 2019, have been described. LBBV has been associated with high virulence results in massive mortality in largemouth bass (

Micropterus salmoides), whereas LCBV infection has only been linked to mild clinical signs in seabass (

Lates calcarifer) [

5,

6]. These findings suggested that birnaviruses may have become prevalent in farmed fish in southeast Asia in recent years. Although several novel birnavirus genomes have been sequenced in recent years [

5,

6,

7], there is still a lack of updated information on the gene structure of the Birnaviridae family.

In this study, we isolated a highly pathogenic birnavirus from mandarin fish, an economically important fish species in southern China. We obtained the complete genome of this virus and characterized its replication dynamics and virulence. We also conducted a detailed analysis of the genome structure of MFBV and other birnaviruses. The inactivation efficiency of the disinfectant on MFBV was also tested.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Cells

Healthy juvenile mandarin fish weighing 10 ± 2 g and fry mandarin fish weighing 0.02 g were obtained from Foshan, Guangdong Province, China. The

Siniperca chuatsi kidney cell (SCK) were isolated and maintained in our laboratory [

8].

2.2. Isolation of the Viral Strain

In the original case, part of mandarin fish (weighing 15-20 g) in the pond can be seen floating on the water and dead within a few hours. Spleen and kidney tissues from cases were underwent sampling. Ten times the volume of PBS was added, and the tissues were thoroughly homogenized. The homogenate was filtered through a 0.45 μm filter (Millipore, USA) to remove bacterial contamination, and then inoculated into SCK cells at a ratio of 1:100 (v/v) and incubated at 27 °C. Cytopathic effect (CPE)-positive cells were identified using phase-contrast microscopy. Infected cells underwent three freeze-thaw cycles and were vortexed for 10 seconds to homogenize. The yielded virus was regarded as the first passage virus. Following subsequent rounds of infection in SCK cells, the viral progeny generated is sequentially referred to as the second passage, third passage, and so forth. Viral culture medium was harvested as the virus stock and stored at −80 °C. The isolated virus strain was designated as MFBV-22TIE (Accession:PP786692.1; PP786693.1).

2.3. Library Construction, Sequencing, and Genome Assembly

Extracting RNA from MFBV-infected SCK cells, and then RNA library was constructed by using the RNA library prep kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The library was sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq platform (Illumina, USA) at Majorbio (Shanghai, China), generating 150-bp paired-end reads. The raw sequencing reads were filtered and quality-trimmed using fastp (version 0.21.0) to remove low-quality bases and adapters. The resulting high-quality reads were de novo assembled using SPAdes (v3.15.4) in metagenomic mode ('-meta') with default settings. Contigs longer than 1000 bp were annotated against the NCBI nonredundant protein (nr) database using DIAMOND (blastx, version 2.0.11) with a stringent E value of 1E-5 to eliminate false-positive results.

2.4. Amplification of Genome Terminal Sequence

Viral RNA was extracted from MFBV-infected cell cultures using a Monarch Total RNA Miniprep Kit (New England Biolabs). Poly (A) tailing of viral genome RNA using E. coli Poly (A) polymerase (New England Biolabs). The SMARTer RACE kit (Takara, Japan) was employed to amplify the terminal sequences of genome. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using a modified oligo (dT) primer with an adapter sequence at the 5' end. The 5' and 3' ends of the cDNA were then amplified using nested specific primers of and the universal primer mix provided in the kit. The amplified products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis, and bands of interest were purified and sequenced using Sanger sequencing technology. The obtained sequences were then assembled and analyzed to determine the terminal sequences of the RNA virus genome. The specific primers used are list below:

SegmentA-3'-outer CCCTCACCCAGAGGAGCACCAAACT

SegmentA-3'-inner CAAGCCCCTGCACCACCAGAGTTTG

SegmentA-5'-outer CGGAGAGTACCCTGCTGACCAGTCT

SegmentA-5'-inner AGGCCTTCTTCAGGTCCTGTGAGGT

SegmentB-3'-outer AAAGAAGCAGAAGCAGCAGCCGACC

SegmentB-3'-inner ACCGACGACTGGGGAGAAGCATCAG

SegmentB-5'-outer GCTCGGGCTTGTGCATGGGGTAGTA

SegmentB-5'-inner CGACGAGTACAGCCAGACTGGGGAG

2.5. Analysis of the MFBV Genome

Phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA (Version 4.0) software by maximum likelihood method with default parameters. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using Kalign [

9]. The birnavirus sequences used in phylogenetic analysis were: Largemouth bass birnavirus (LBBV), MW727622.1 and MW727622.1; Lates calcarifer birnavirus (LCBV), MK103419.1 and MK103420.1; Blotched snakehead virus (BSNV), AJ459382.1 and AJ459383.1; Infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV), AJ622822.1 and AJ622823.1; Infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV), MZ888508.1 and MZ888507.1; Drosophila melanogaster birnavirus (DBV), GQ342962.1 and GQ342963.1; Rotifer birnavirus (RBV), FM995220.1 and FM995221.1; Tellina virus 1 (TV-1), AJ920335.1 and AJ920336.1; Drosophila x virus (DXV, U60650.1 and NC_004169.1.

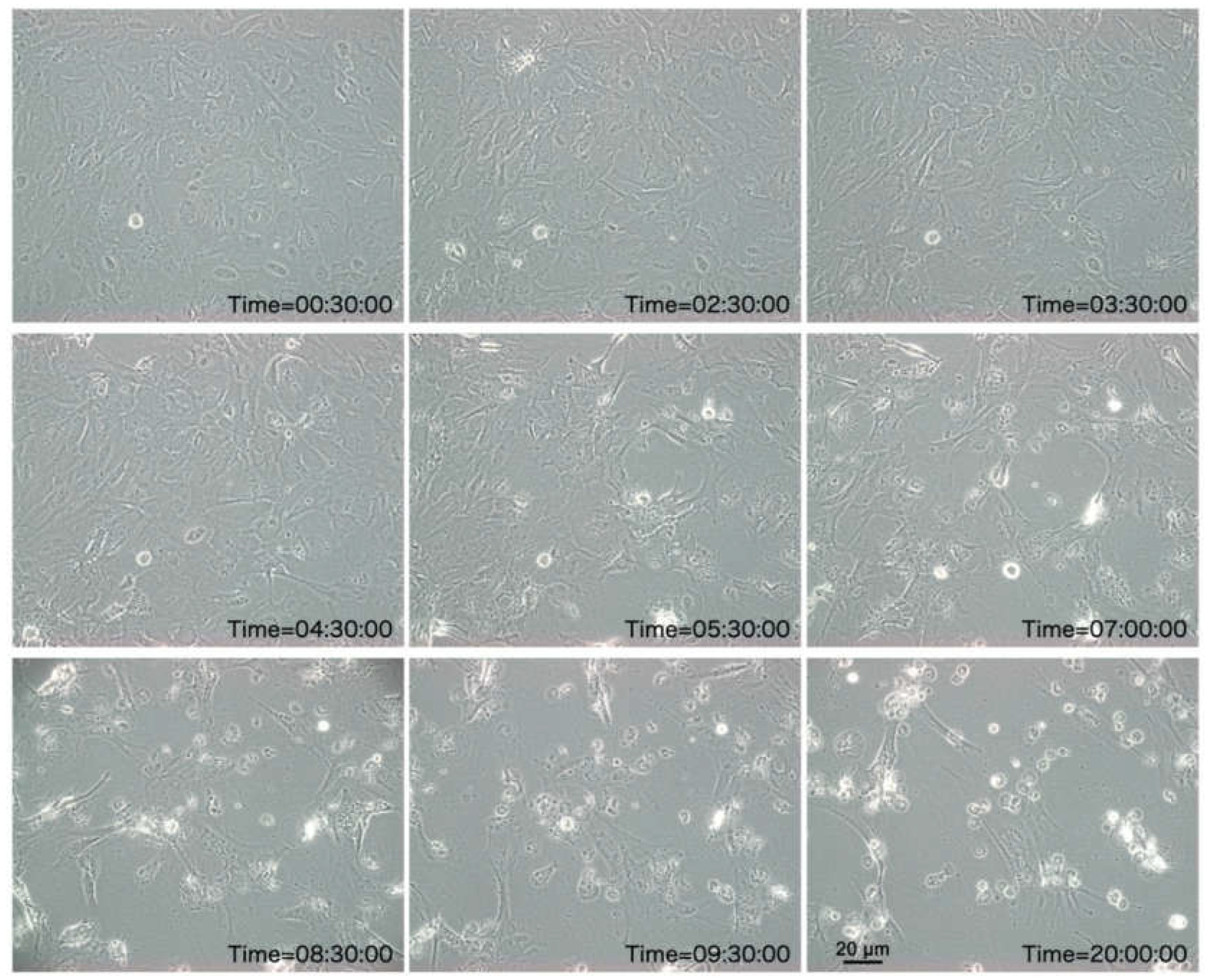

2.6. Assessment of Cytopathic Effect

SCK cells were employed to assess the CPE induced by MFBV. Cells were passaged at an appropriate ratio, in triplicate, in 25 cm2 flasks to ensure a confluent monolayer, and then infected with MFBV. The initial infectious dose was established at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3. Phase-contrast images were captured using a ZEISS Observer.Z1 inverted microscope at indicated time points.

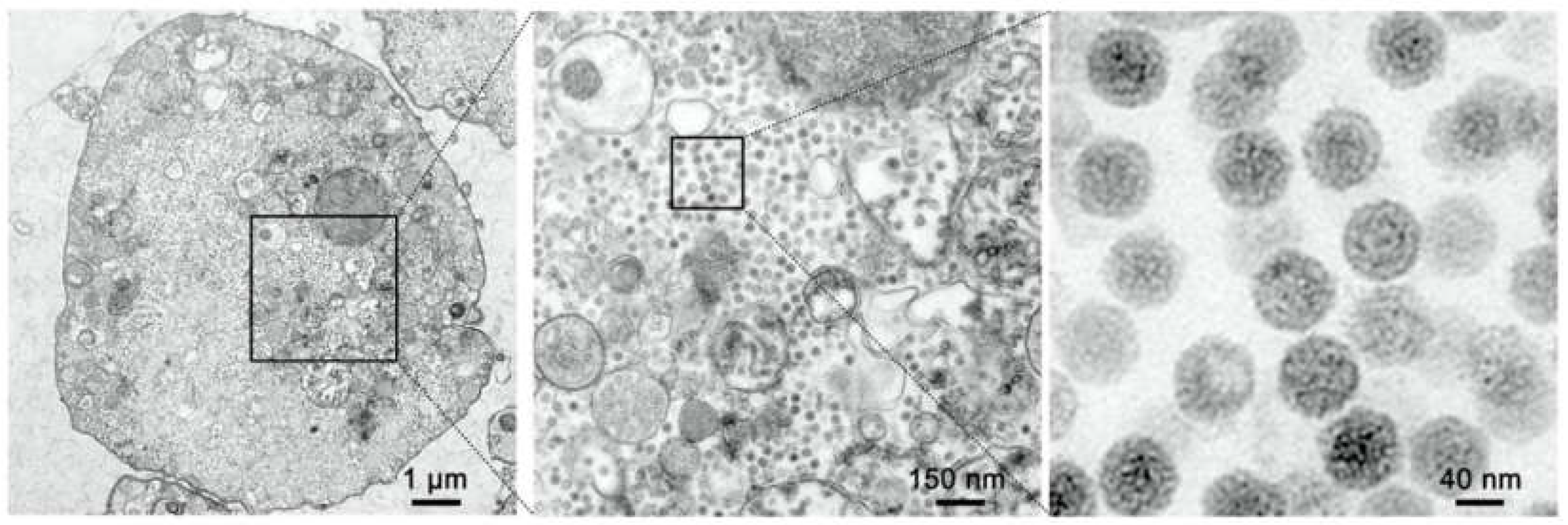

2.7. Transmission Electron Microscopy

SCK cells were inoculated with MFBV at an MOI of 5. At 16 hours post-infection (hpi), cells were gently scraped, centrifuged at 500× g for 3 minutes, and then fixed using 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Following osmium tetroxide post fixation, uranyl acetate was applied to enhance membrane contrast. Epoxy resin served as the embedding medium. The ultrathin sections were visualized using a Hitachi HT7800 transmission electron microscope.

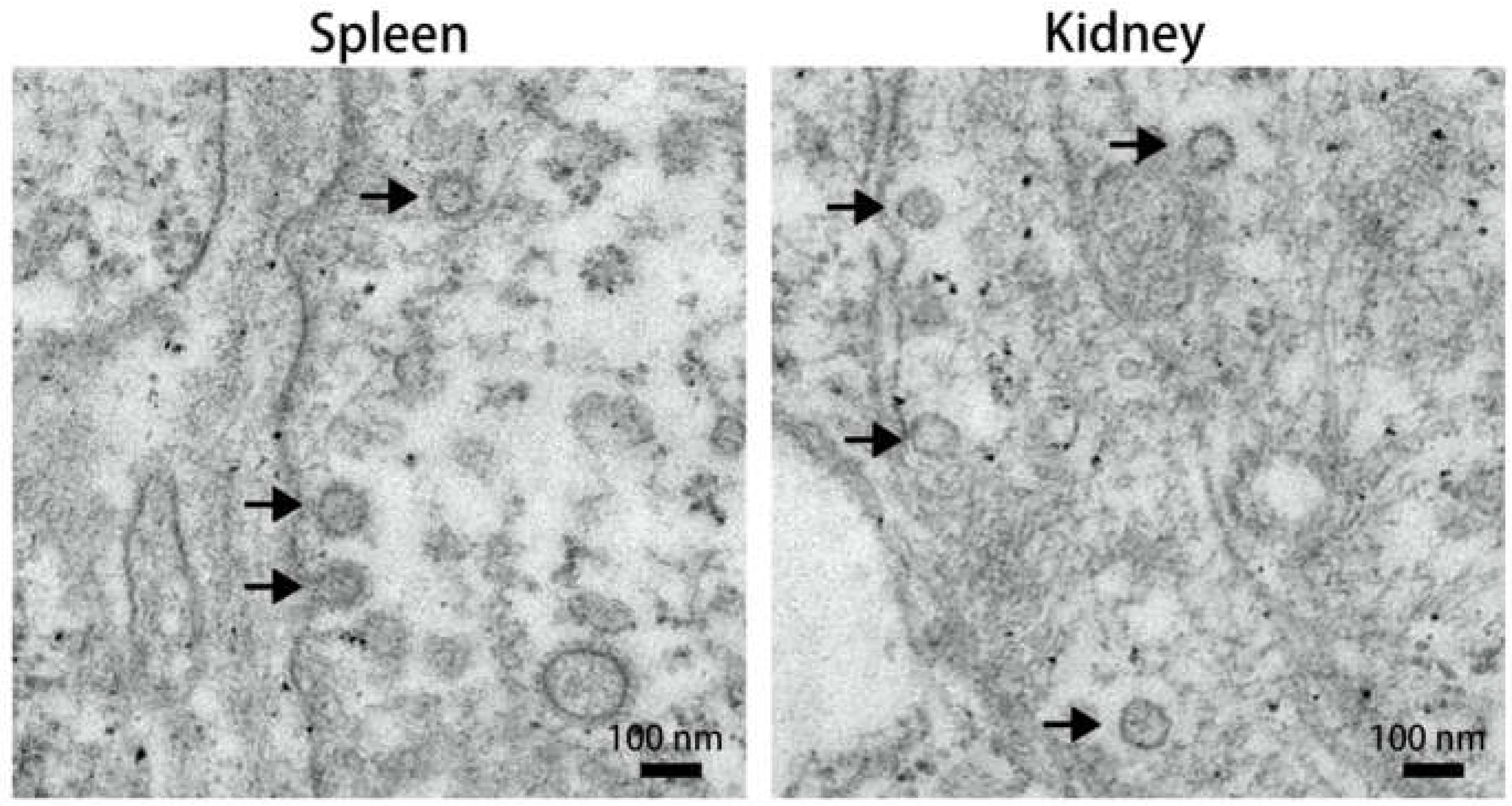

The fish spleen and kidney tissues were cut into 1 mm³ pieces and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Secondary fixation was performed with osmium tetroxide. The fixed specimens were dehydrated by incubation in a series of ethanol solutions (30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 95%, and 100%) followed by 100% acetone. After resin infiltration and embedding, the samples were sectioned to 80 nm thickness, mounted on copper mesh, and post-stained with lead citrate. The ultrathin sections were visualized using a Hitachi HT7800 transmission electron microscope.

2.8. Virus Titer Assays

SCK cells were seeded in 48-well plates with 200 μl of medium in each well. The 3rd-passage MFBV samples collected at indicated time points underwent 3 freeze-thaw cycles and were vortexed for 10 s for homogenization. Samples were then titrated using 10-fold serial dilutions, with six wells being inoculated with 200 μl of each dilution. Wells were designated as positive if typical CPE was observed at 7 dpi. The 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID

50) values were computed using the TCID

50 calculator (Marco binder, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany) based on the Spearman–Kärber method [

10]. Virus titer values represent mean ± SE for three biological replicates of MFBV samples.

2.9. Artificial Challenge

In juvenile mandarin fish intraperitoneal injection challenge study, groups of 15 fish were kept in 150 L tanks at temperatures ranging from 28 to 30 °C. Each fish received an intraperitoneal injection of 109 TCID50 3rd-passage MFBV suspended in 0.2 ml cell culture medium. Additionally, ten fish were administered the same volume of untreated cell cultures to serve as controls. Fish mortality was monitored daily for three weeks, with cumulative mortality data collated from the three separate experiments.

In the juvenile and fry mandarin fish immersion challenge study, fish were immersed in water with a virus concentration of 107 TCID50/ml for 20 minutes, then transferred to 150 L tanks at 28 to 30 °C. For fry fish, the study concluded on 3 dpi.

2.10. Absolute Quantitative RT-PCR

Nine fish were sampled per treatment group, 14 tissues and intestinal content samples were collected at 16 hpi, including spleen, pronephros, mesonephros, metanephros, pyloric caeca, intestine, intestinal contents, stomach, thymus, heart, skin, gill, liver, gonad and brain. RNA of samples were isolated using a Monarch Total RNA Miniprep Kit. RNA was incubated at 65 °C for 5 minutes and promptly placed on ice to denature RNA double strands and secondary structures. Reverse transcription was performed using Induro Reverse Transcriptase (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Absolute quantitative PCR with primers for MFBV segment A was performed (Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR System) to quantify the total copies of viral genome and mRNA. The standard samples consist of a series of tenfold dilutions of segment A PCR amplification products with known concentrations. RT-qPCR was performed in a total reaction volume of 20 μl containing 0.2 μM primers, 1 μl of cDNA, 10 μl of 2 × SYBR Green Premix (Takara, Japan), and 7.2 μl of RNase-free water. The following settings were used: 40 cycles of amplification for 10 seconds at 95 °C and 30 seconds at 65 °C. Each sample was run in technical triplicates. Primers used were: MFBVsegA-qPCR-F: CTGGATAGCCAGGAACGACC; MFBVsegA-qPCR-R: GTTGTCGGCGTACACTTCCT

2.11. Histopathological Sectioning and H&E Staining

Intestine, spleen and metanephros tissues were fixed with formalin and acetic acid fixative overnight, and preserved with 70% ethanol. Dehydration was sequentially performed using 70%, 80%, 95%, and anhydrous ethanol. Then, these samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned. The slices were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and prepared as permanent slides after they were dried, dewaxed, and hydrated. The slices were then observed under the microscope.

2.12. Determine the Inactivation Efficiency of Disinfectants

All disinfectants were diluted to the appropriate concentrations using sterile ultrapure water and added to the virus suspension (11 Log10 TCID50/ml). The mixture was immediately vortexed for 10 seconds for homogenization and centrifuged at 100 × g for 3 seconds to collect the liquid from the tube lid. After incubation at 25°C for 30 minutes, the viral titer was immediately assayed using the method described above. The cells were incubated with the same concentration of disinfectant as a control to exclude the effect on cell activity by disinfectant.

2.13. Determination of the Stability of MFBV Suspension

MFBV infected SCK cell culture (at 24 hours post infection with a titer of 11.73 Log10 TCID50/ml) was incubated for up to 90 days at room temperature and dark conditions, and tested for its infectivity. Briefly, at desired time-points, the inoculated objects were vortexed for 3 seconds to homogenize the precipitate and retrieved, then immediately assayed titers in SCK cells using the method described above.

4. Discussion

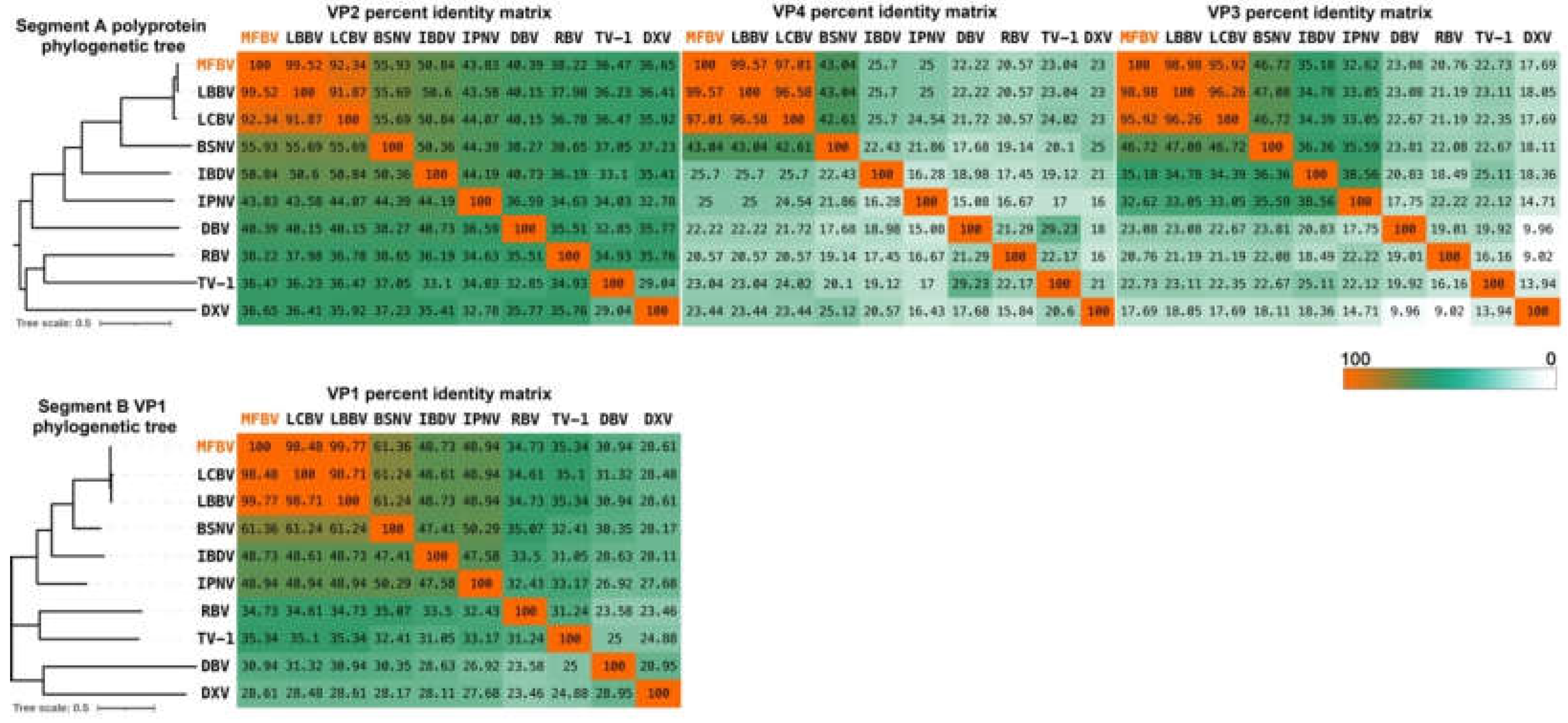

In this study, we report the detection and characterization of a novel mandarin fish birnavirus, named MFBV. Furthermore, we validated through Koch's postulates that MFBV is a novel causative agent for mandarin fish. The full-length sequences of MFBV segments A and B were obtained through RACE and molecular cloning and were used for in-depth phylogenetic analyses between MFBV and other RNA viruses. MFBV, LBBV, and LCBV formed a distinct branch with the closest phylogenetic relationship, while other birnaviruses classified by ICTV and newly discovered strains were more distantly related (based on RdRp amino acid sequence analysis: Rocky Mountain birnavirus, 47.94% identity; Wenling jack mackerels birnavirus, 48.05% identity; Wenling Japanese topeshark birnavirus, 50.12% identity).

MFBV VP4 protease and its polyprotein substrate, both exhibit low homology with the other members of the

Birnaviridae family, raising questions about whether they follow the same cleavage mechanism. To address this, we analyzed the amino acid sequences of MFBV and other birnaviruses VP4 proteins. Alignment of VP4 proteins revealed that the two coordinated amino acids, serine and lysine, are conserved in

Birnaviridae members. The Ser-Lys catalytic dyad active site in IPNV, IBDV, and BSNV VP4 has been experimentally identified and is considered a serine protease [

13,

16,

22,

23], suggesting that MFBV VP4 utilizes a Ser (701)-Lys (738) catalytic dyad (

Figure S1A).

Furthermore, we examined the P7-P7' amino acid residues flanking the cleavage sites of MFBV polyprotein. The analysis was based on the cleavage sites of TV-1 polyprotein, which have been experimentally validated [

20]. The results revealed that the conserved motif of cleavage site is an alanine (Ala) at position P1 (with the exception of the serine (Ser) in DXV), and no other conserved motifs were found. Additionally, the P1'-P3' sites of the small peptide cleavage sites exhibit conserved ASG amino acid residues, the function of which remains unknown (

Figure S1B). These analyses suggest that although there is significant divergence in birnavirus sequences, the MFBV protease cleavage mechanism is conserved.

RdRp self-guanylylation has been demonstrated in multiple birnaviruses, such as DXV [

24], IBDV [

25], and IPNV [

26]. Specifically, the 5′ ends of the dsRNA genome of birnaviruses are bound to a genome-linked protein (VPg, another form of RdRp) by a Ser-5′-GMP phosphodiester bond at self-guanylylation site [

27]. The guanylylation site of IPNV has been determined to be S163 using peptide digestion and site-directed mutagenesis [

28]. Additionally, the IBDV guanylylation site residue was putatively identified as S166 [

25], and there have been no other analyses of birnaviruses self-guanylylation sites. We used the IPNV guanylylation site amino acid sequence as a reference to predict the guanylylation site in other birnaviruses through homology comparison. Ser residues were found at the corresponding position or at position -2 in all aligned sequences. These residues are also approximately 80 amino acids away from the conserved motif G, suggesting a topological and functional conservation. Based on these findings, we predict S164 as the site for self-guanylylation in MFBV RdRp (

Figure S2).

Another feature of the MFBV or other birnaviruses was that RdRp has the unique catalytic core motifs. The prototypic RNA virus RdRp domain harbors seven motifs, which are arranged in the order G, F, A, B, C, D and E from amino- to carboxy-terminus. The only exception to this scheme can be found in some ssRNA (+) non-segmented virus and birnavirus [

25,

29,

30], which is exactly the case with MFBV, it was G-F-C-A-B-D-E. (

Figure S3A).

Motifs C and A are the most essential catalytic core motifs in RdRp, housed in the palm subdomain of a right-hand architecture [

30,

31,

32]. Within motif C, the DD amino acid residues are in the RNA polymerase active site, allowing catalysis to occur via a two-metal mechanism [

30,

33]. The DD amino acid motif is conserved across most RNA viruses, including positive strand RNA viruses (+RNA), segmented negative strand RNA viruses (seg −RNA), double strand RNA viruses of the reovirus family (Reo dsRNA), and reverse transcriptases (RT). However, the DD amino acid motif is not found in MFBV, instead, it is replaced by the DN motif (

Figure S3A). Furthermore, we conducted multiple sequence alignment analysis on representative RdRp sequences from all eleven families within order

Mononegavirales (negative-sense genome single-stranded RNA viruses, including

Artoviridae, Bornaviridae, Filoviridae, Lispiviridae. Mymonaviridae, Nyamiviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Pneumoviridae, Rhabdoviridae, Sunviridae and

Xinmoviridae; ICTV Virus Taxonomy 2023 Release) to examine the conservation of motif C catalytic core. The results indicate that MFBV employs a DN catalytic core consistent with other birnaviruses and

Mononegavirales viruses (

Figure S3A, B) [

24,

30], for instance, in Ebolavirus [

34], respiratory syncytial virus [

35], and rabies virus [

36]. The DD amino acid residues in RddRp motif C are involved in coordinating interactions with divalent metal ions, which are essential for the phosphoryl transfer reaction [

33]. Some suggest that the distinct evolution of the catalytic core in Birnavirus and

Mononegavirales, from DD to DN, may have enhanced RdRp adaptability to divalent metal ions. The IBDV DN motif has been shown to exhibit greater activity for nucleotide polymerization when utilizing Mn

2+, while replaced with DD leads to more efficient coordination with Mg

2+ [

25,

37]. However, the DN motif remains a minority in RNA viruses [

30]. Whether this feature confers a survival advantage to birnaviruses such as MFBV in natural environments requires further investigation.

Another highly conserved RdRp motif is the DX2-4D amino acid residues in motif A [

30,

31]. However, in MFBV, this catalytic motif is replaced by DX2K, a pattern unique to segmented negative-strand RNA viruses (seg −RNA) and non-segmented negative-strand RNA (−RNA) viruses [

30]. Furthermore, we found that the DX2K motif of MFBV is completely consistent with that of most birnaviruses and the family

Filoviridae of order

Mononegavirales, specifically DLEK motif. This family includes well-known viruses such as Ebola virus and Marburg virus, as well as fish filoviruses discovered through virus metagenomic studies (Wenling frogfish filovirus strain, MG599980.1; Wenling thamnaconus septentrionalis filovirus, MG599981.1). Both the DN and DLEK catalytic motifs are rare among RNA viruses, the concurrent utilization of these two motifs by both birnaviruses and filoviruses may suggest a potential evolutionary relationship between the two (

Figure S3A,B). However, based on capsid topology analysis, the jelly roll structure of IBDV VP2 (within segment A) and its inserted domain were respectively linked to two different categories of RNA viruses: Black Beetle virus (Nodaviridae, non-enveloped positive-strand RNA viruses, T=3) and rotavirus (Reoviridae, non-enveloped double-stranded RNA viruses, external and intermediate layer, T=13) [

21]. Along with our discovery of the phylogenetic relationship between segment B and filoviruses in this study, this supports the hypothesis that birnavirus segments A and B have undergone reassortment and followed distinct evolutionary pathways [

14,

38].

The untranslated regions (UTRs)of birnavirus genome are essential for replication and translation processes [

37,

39]. The 5'UTR serves as a binding site for VPg [

40,

41] and the 3'UTR cytosines allow protein-primed initiation of second strand RNA synthesis [

26,

37]. The precise sequences of 5'UTR and 3'UTR have been experimentally determined for some birnaviruses, such as LBBV [

6], BSNV [

13], IPNV [

11], IBDV [

12] and TV-1 [

20]. Multiple sequence alignment analysis of MFBV and these birnaviruses revealed a conserved starting motif of GGAAA (except for IBDV's GGAUA) (

Figure S4). Additionally, the two constitutive cytosines at 3' terminus (except for LBBV and TV-1 segment B) form a small stem-loop secondary structure, which is crucial for virus replication or virulence [

42]. However, the position and length of the 3'UTR stem-loop end are not fixed in birnaviruses (

Figure S4).

Birnavirus mRNA is known to lack a cap, thus relying on cap-independent mechanisms for translation initiation. However, the relatively short 5'UTR of birnaviruses appears insufficient to form a typical internal ribosome entry site (IRES) for translation initiation (a cap-independent mechanism) [

42]. While there are reports of IPNV segment A having IRES within the 120bp 5'UTR [

43], whether this critical IRES secondary structure is conserved in MFBV remains unknown. We used MXfold2 (

http://www.dna.bio.keio.ac.jp/mxfold2/) [

44] to predict the MFBV 5'UTR secondary structure. The result revealed the stem-loop structures at the 5' ends of segments A and B of MFBV, albeit simpler compared to known IRES structures of four classes [

45,

46]. Furthermore, MFBV's segment A 5'UTR is only 170 bp, and segment B 5'UTR is only 96 bp, significantly shorter than compact typical Class III (332 bp) [

45,

47] or Class IV intergenic region IRES (191 bp, KP974706.1) structures [

45]. Therefore, it is speculated that IRES may not be universally present in birnaviruses, at least not in MFBV, suggesting that MFBV may initiate translation through alternative pathways (

Figure S5).

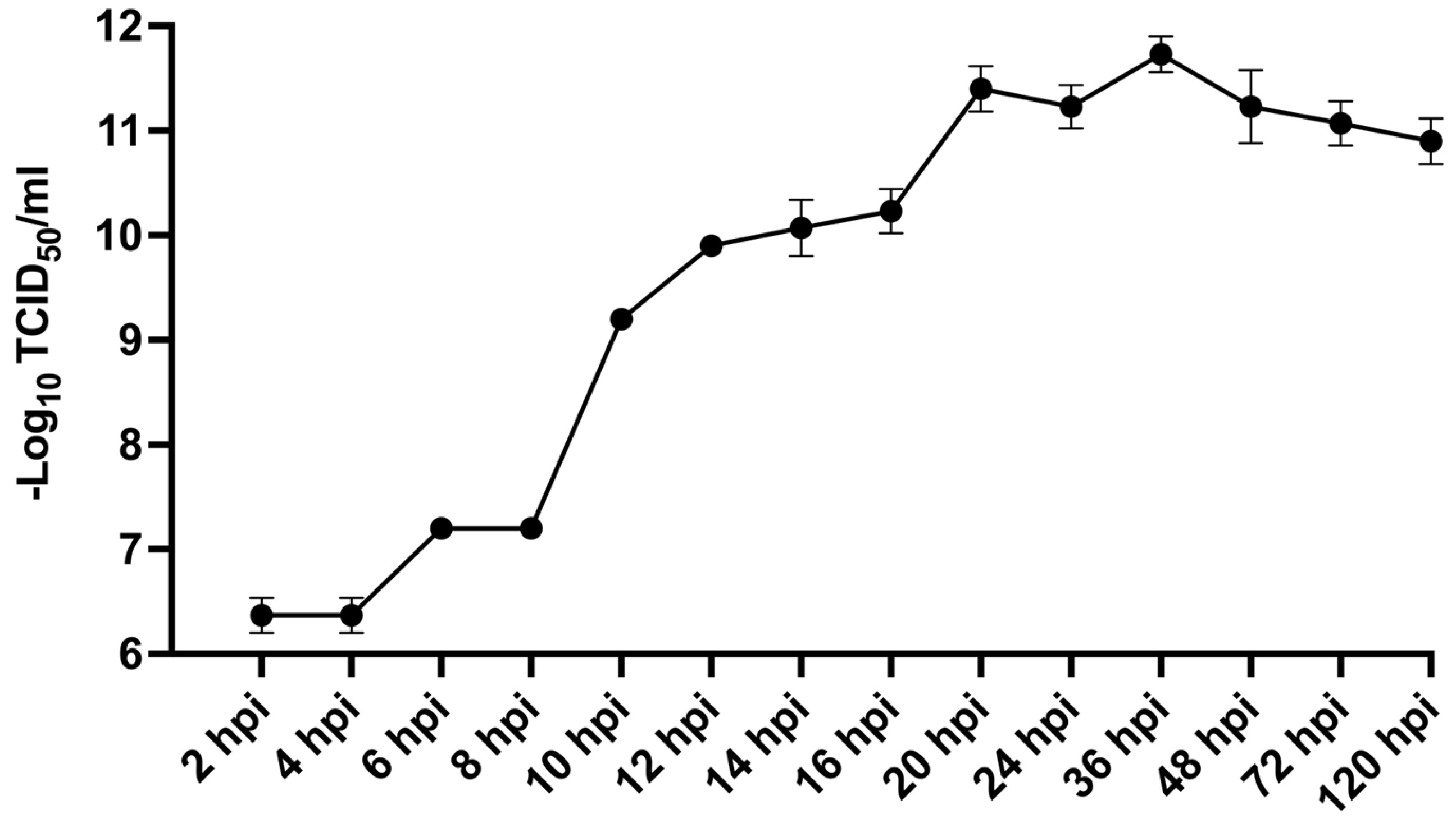

For IPNV, the complete replication cycle takes about 24 hours at 15°C, but is shortened to 16-20 hours at 22°C in salmon embryo (CHSE-214) cells, with replication ceasing at 28°C [

48,

49,

50]. MFBV exhibits a replication cycle of 8-10 hours at 27°C in SCK cells. At their respective suitable replication temperatures, MFBV replicates significantly faster than IPNV. Furthermore, approximately 10

7.9 MFBV RNA copies per μg total RNA can be detected in the spleen as early as 16 hpi, which means MFBV replication is also notably faster than other pathogens of mandarin fish, such as ISKNV [

51] and MRV [

8]. The rapid replication kinetics may explain why severe symptoms, including mortality, occur as early as 6 hours post-infection in mandarin fish. In contrast, other mandarin fish viral pathogens such as ISKNV and MRV typically require 3-5 days to induce mortality even at high inoculum doses [

8,

51]. Further, in all fourteen tissues, the MFBV RNA copies per μg total RNA exceeded 10

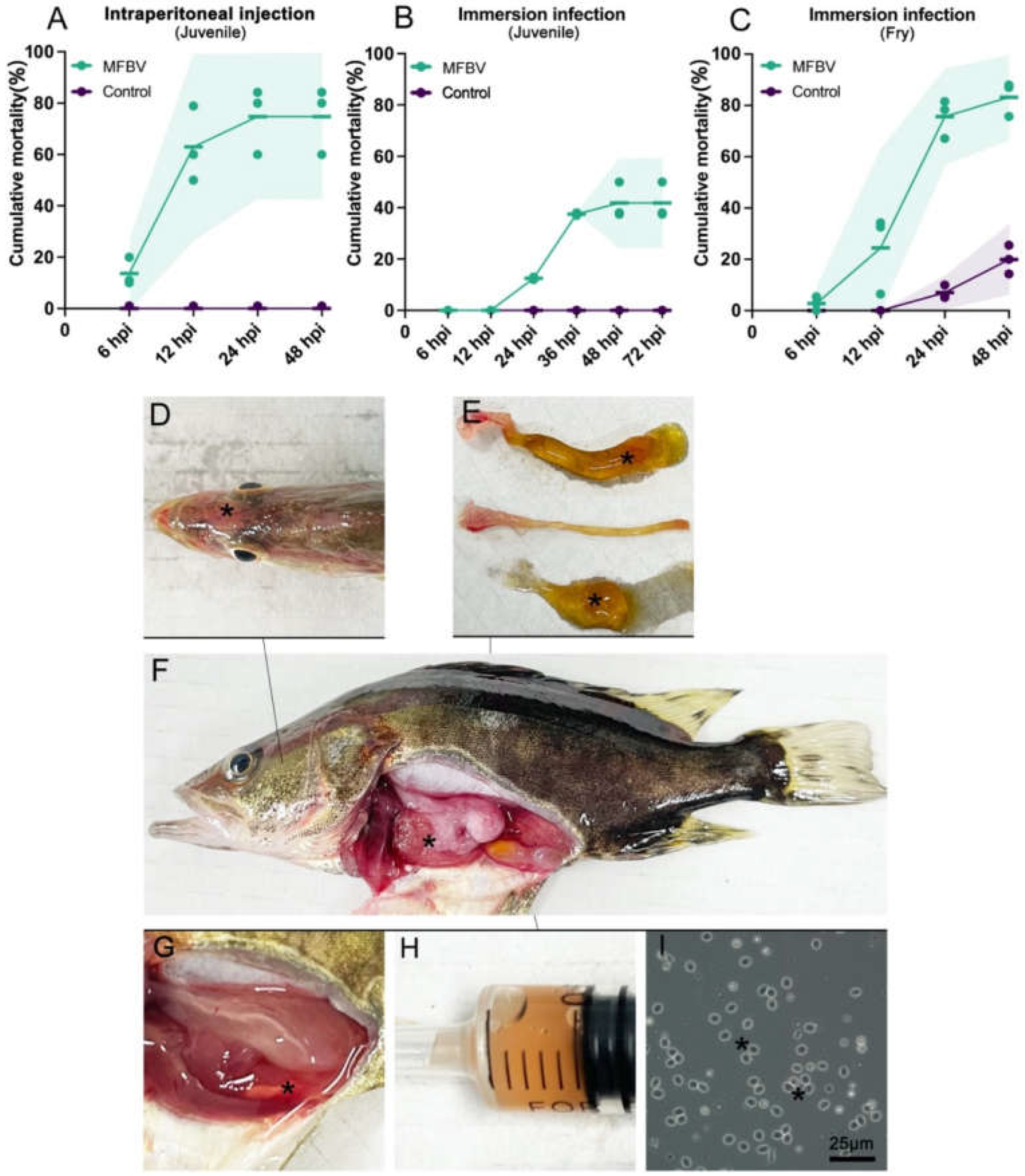

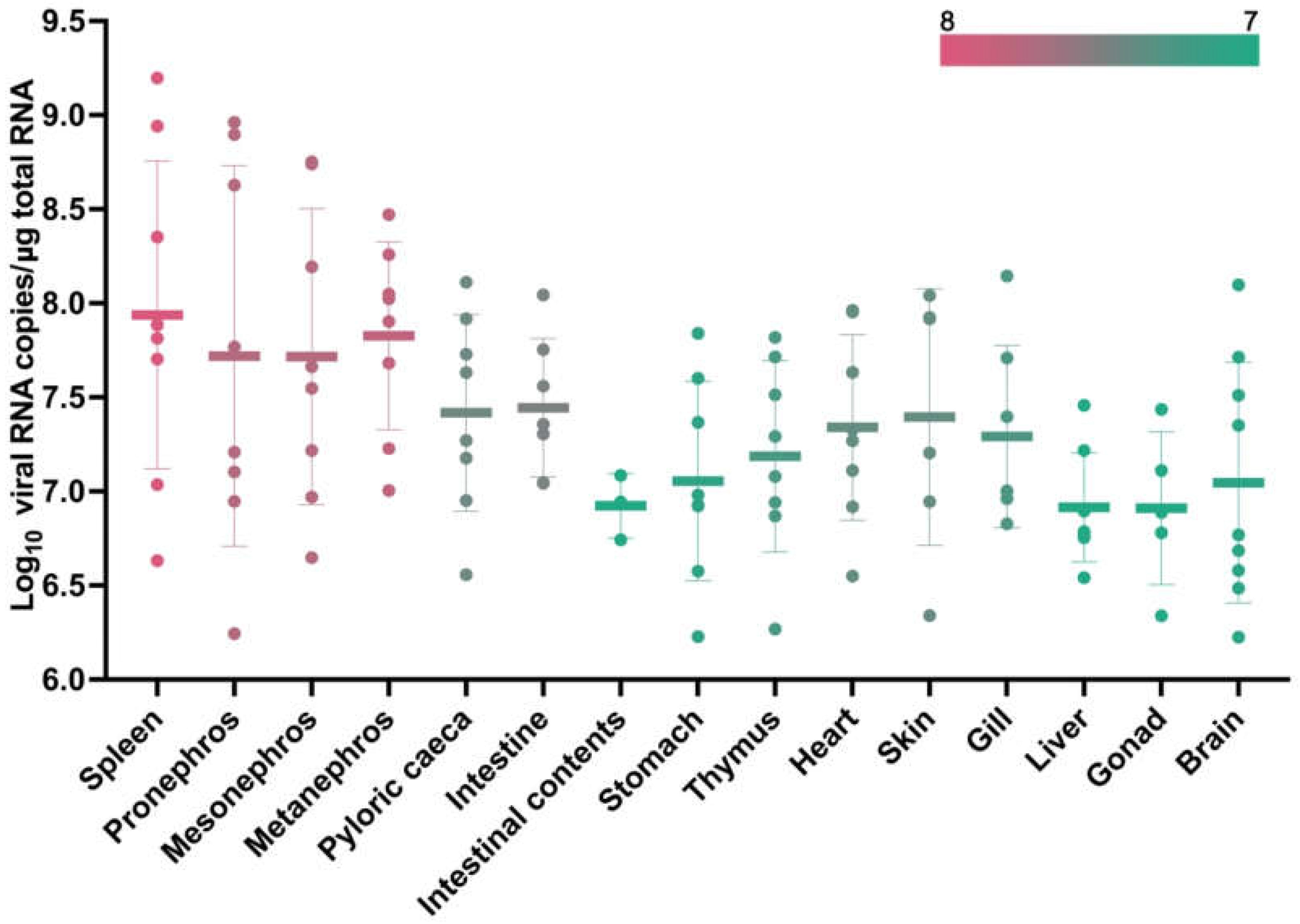

6.9, with only a tenfold difference between the tissue with the highest (spleen) and the lowest (gonad). This suggests that MFBV does not show significant tissue tropism and is capable of causing systemic multi-organ infections. It is speculated that severe systemic infection is another factor contributing to the rapid mortality. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the threat of MFBV to fry is greater than that to juveniles, as evidenced by the higher mortality rate of fry (approximately 30%-40% higher). This corresponds to the birnavirus outbreak in a mandarin fish fry factory in Yangchun City in May 2023, when millions of week-old fry died within 48 hours, with a mortality rate of nearly 100%.

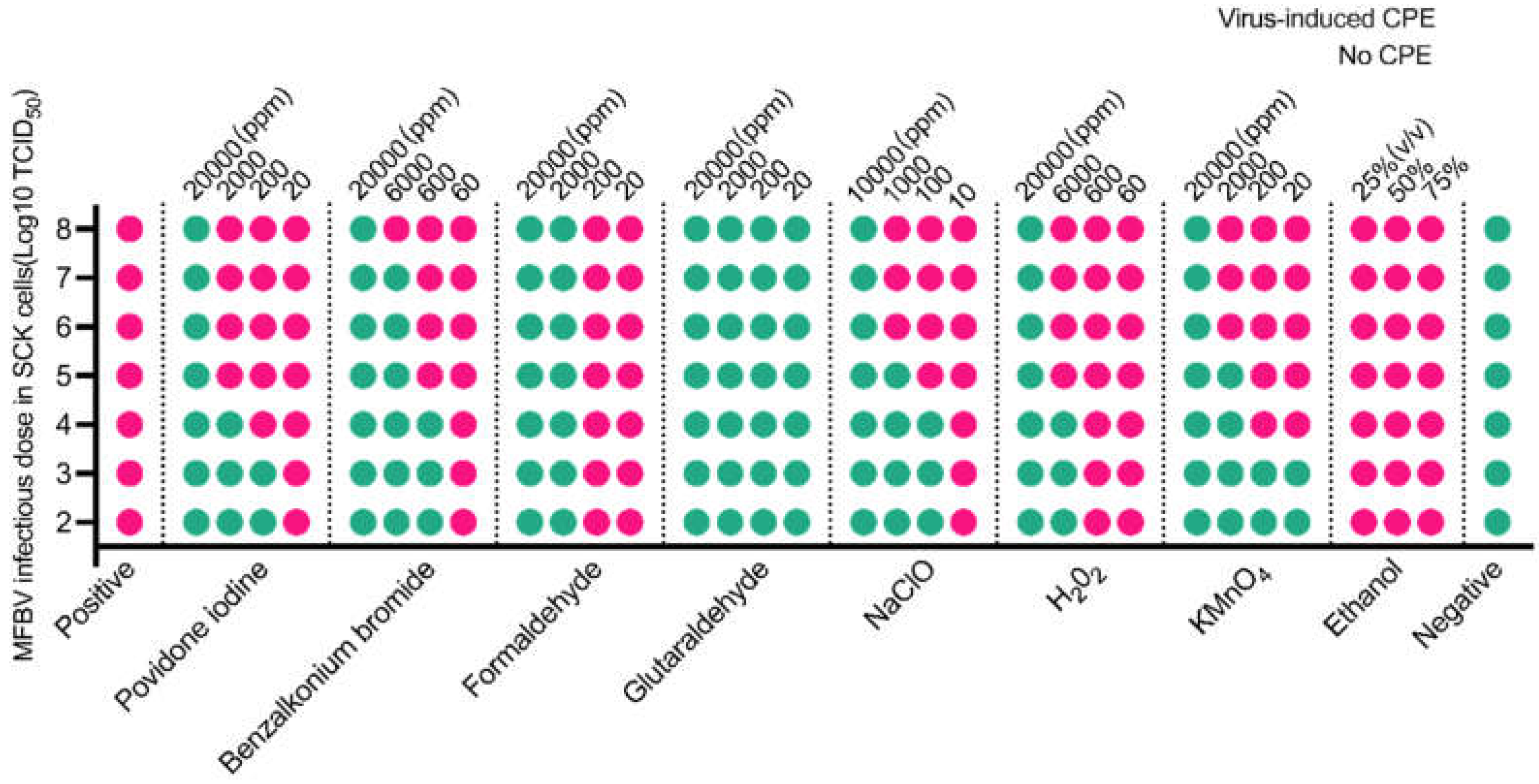

To mitigate MFBV outbreaks, we tested its sensitivity to various disinfectants. The experimental concentration ranges of disinfectants in this study were determined based on the study on ISKNV, and

Micropterus salmoides rhabdovirus. ISKNV can be inactivated by sodium hypochlorite (1000 ppm for 30 minutes) and benzalkonium chloride (650 ppm for 10 minutes) [

52] , while

M. salmoides rhabdovirus can be inactivated by 500 ppm povidone-iodine and 500 ppm glutaraldehyde within 30 minutes [

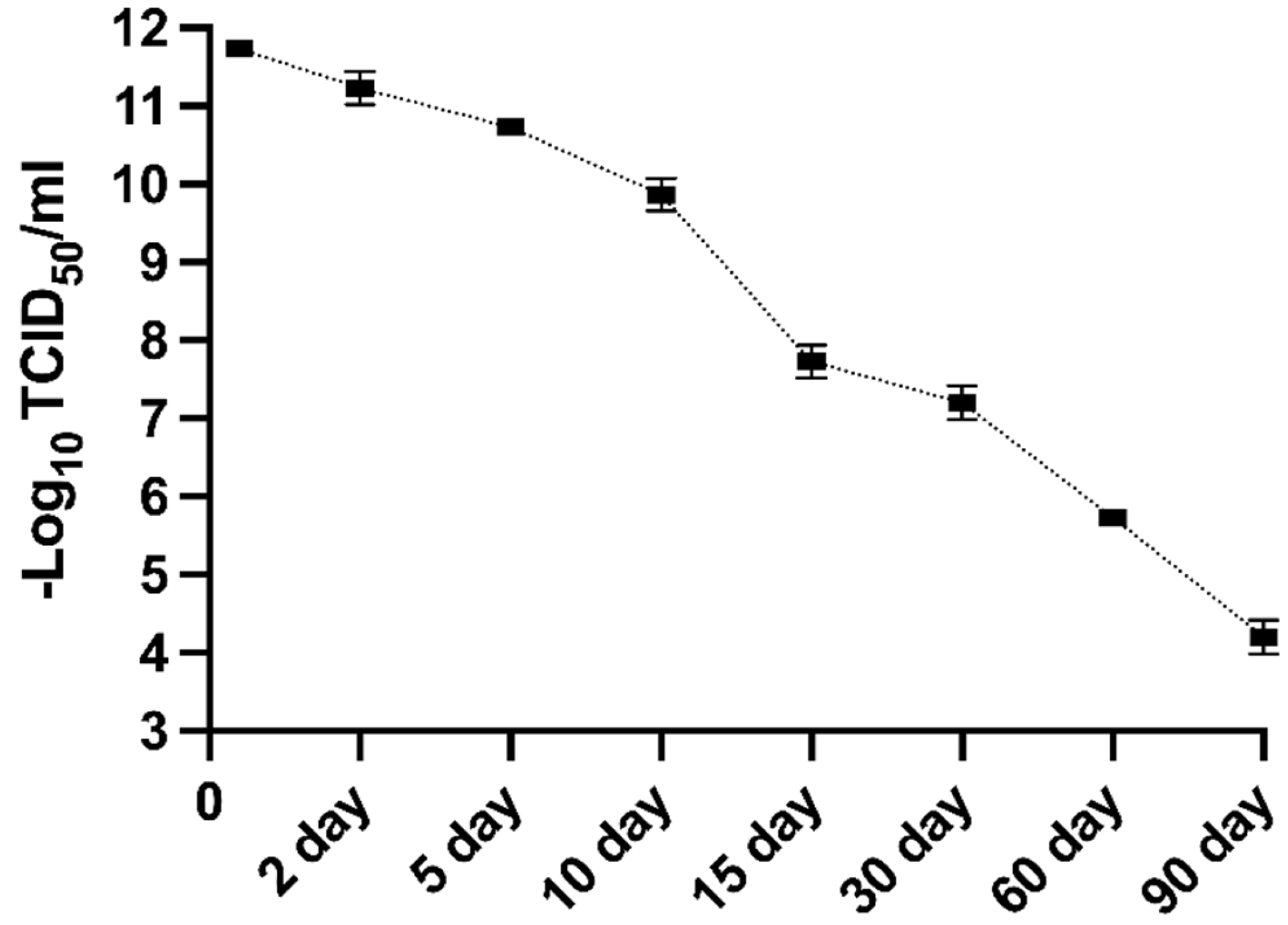

53]. Based on these results presented, one or more disinfectants can be chosen for different epidemic outbreaks. Additionally, in the laboratory, a 15-day storage reduced MFBV infectivity by 99.9%, suggesting natural decay could be an alternative in the absence of disinfection. However, organic and inorganic substances in natural water may affect decay rates [

54], requiring further optimization.

Taken together, this research may have important implications for exploring the MFBV replication mechanism and developing disease containment strategies.

Figure 1.

TEM micrographs of spleen and kidney tissue from the dead fish. Arrows indicate virus-like particles with a polyhedral morphology.

Figure 1.

TEM micrographs of spleen and kidney tissue from the dead fish. Arrows indicate virus-like particles with a polyhedral morphology.

Figure 2.

Phase contrast microscopic images depicting CPE in SCK cells elicited by the 3rd passage of MFBV at different hpi. All images were obtained within the same field of view.

Figure 2.

Phase contrast microscopic images depicting CPE in SCK cells elicited by the 3rd passage of MFBV at different hpi. All images were obtained within the same field of view.

Figure 3.

TEM micrographs of MFBV-infected SCK cells. The images on the right side are magnified views from the boxed region in adjacent left images.

Figure 3.

TEM micrographs of MFBV-infected SCK cells. The images on the right side are magnified views from the boxed region in adjacent left images.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the segment A genome organization of MFBV and other representative birnaviruses. The additional pink graphics illustrating processing of preVP2. Polyprotein cleavage sites are indicated by vertical bars and identified by nucleotide positions. Numbers at the 3′-ends indicate the full length of segment A.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the segment A genome organization of MFBV and other representative birnaviruses. The additional pink graphics illustrating processing of preVP2. Polyprotein cleavage sites are indicated by vertical bars and identified by nucleotide positions. Numbers at the 3′-ends indicate the full length of segment A.

Figure 5.

Distance tree representing the phylogenetic relationships of the polyprotein and VP1 within the Birnaviridae family. The percent identity matrices are generated based on VP2, VP3, VP4 and VP1 amino acid sequences.

Figure 5.

Distance tree representing the phylogenetic relationships of the polyprotein and VP1 within the Birnaviridae family. The percent identity matrices are generated based on VP2, VP3, VP4 and VP1 amino acid sequences.

Figure 6.

Infectious dynamics of MFBV in SCK cells. Viral titers of the 3rd passage of MFBV at indicated time points were measured and expressed as TCID50/ml. Each titer value represents the mean ± SE derived from three biological replicates. Partial SE is hidden within the data points.

Figure 6.

Infectious dynamics of MFBV in SCK cells. Viral titers of the 3rd passage of MFBV at indicated time points were measured and expressed as TCID50/ml. Each titer value represents the mean ± SE derived from three biological replicates. Partial SE is hidden within the data points.

Figure 7.

(A–C) The cumulative mortality rates in MFBV-infected mandarin fish; mean ± SD from three independent experiments, with the shadow representing the 95% confidence interval. (A) Juvenile mandarin fish as the experimental subjects, challenged via intraperitoneal injection. (B) Juvenile mandarin fish as the experimental subjects, challenged via immersion. (C) Fry mandarin fish as the experimental subjects, challenged via immersion. (D–I) Symptoms of MFBV-infected mandarin fish. (D) Congestion of the head skin (denoted by asterisks) (E) From top to bottom, the intestine filled with mucus, the intestine after removing the mucus, and the mucus itself. Asterisks indicate the yellow mucus. (F) Anatomical view of MFBV-infected mandarin fish. Asterisks indicate visceral congestion. (G–H) Asterisks indicate pale red ascites. All ascites (~0.5 ml) account for approximately 5% of body weight. (I) Asterisks indicate red blood cells observed in the ascitic fluid smear.

Figure 7.

(A–C) The cumulative mortality rates in MFBV-infected mandarin fish; mean ± SD from three independent experiments, with the shadow representing the 95% confidence interval. (A) Juvenile mandarin fish as the experimental subjects, challenged via intraperitoneal injection. (B) Juvenile mandarin fish as the experimental subjects, challenged via immersion. (C) Fry mandarin fish as the experimental subjects, challenged via immersion. (D–I) Symptoms of MFBV-infected mandarin fish. (D) Congestion of the head skin (denoted by asterisks) (E) From top to bottom, the intestine filled with mucus, the intestine after removing the mucus, and the mucus itself. Asterisks indicate the yellow mucus. (F) Anatomical view of MFBV-infected mandarin fish. Asterisks indicate visceral congestion. (G–H) Asterisks indicate pale red ascites. All ascites (~0.5 ml) account for approximately 5% of body weight. (I) Asterisks indicate red blood cells observed in the ascitic fluid smear.

Figure 8.

RT-qPCR measured the copy number of MFBV segment A RNA in 14 tissues and intestinal content of MFBV-infected mandarin fish. The color scale indicates the level of viral copy numbers. Mean ± SD from tissues of nine fish.

Figure 8.

RT-qPCR measured the copy number of MFBV segment A RNA in 14 tissues and intestinal content of MFBV-infected mandarin fish. The color scale indicates the level of viral copy numbers. Mean ± SD from tissues of nine fish.

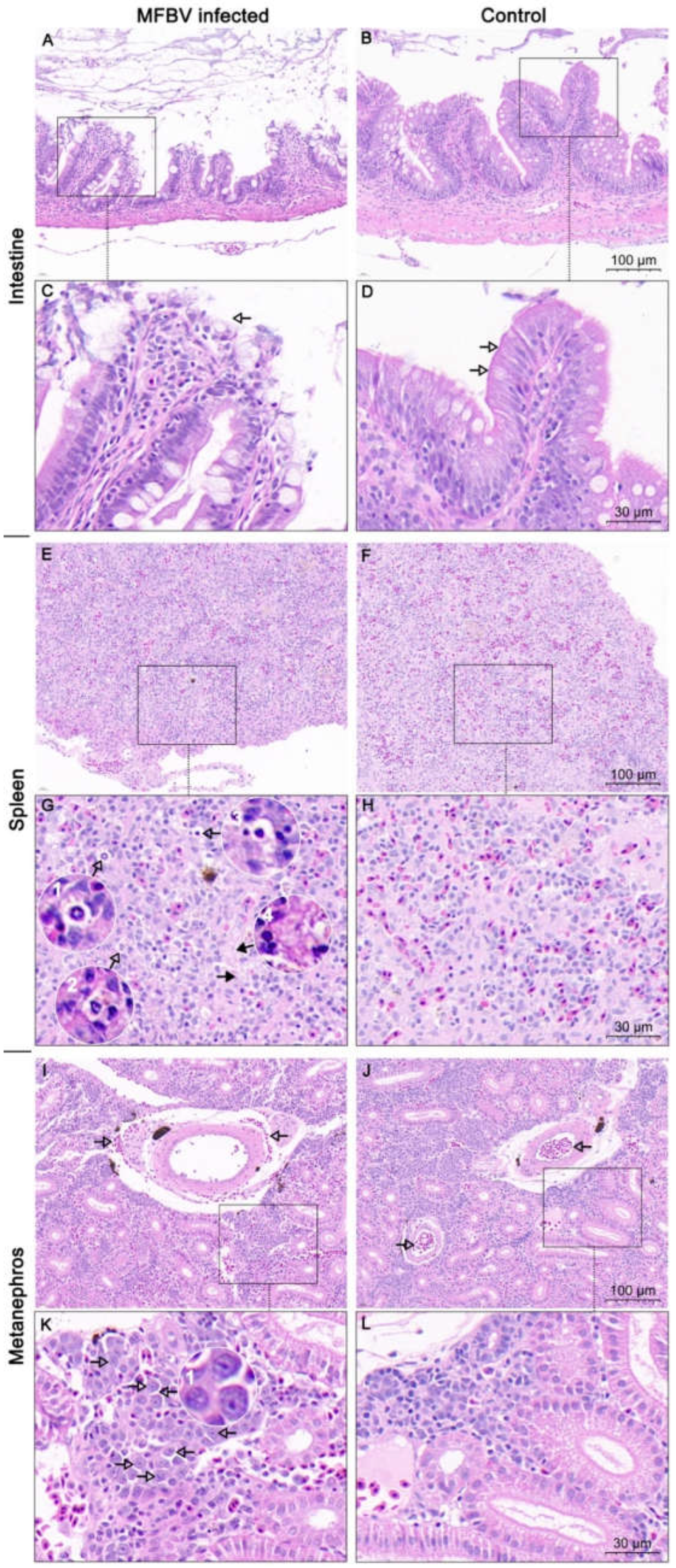

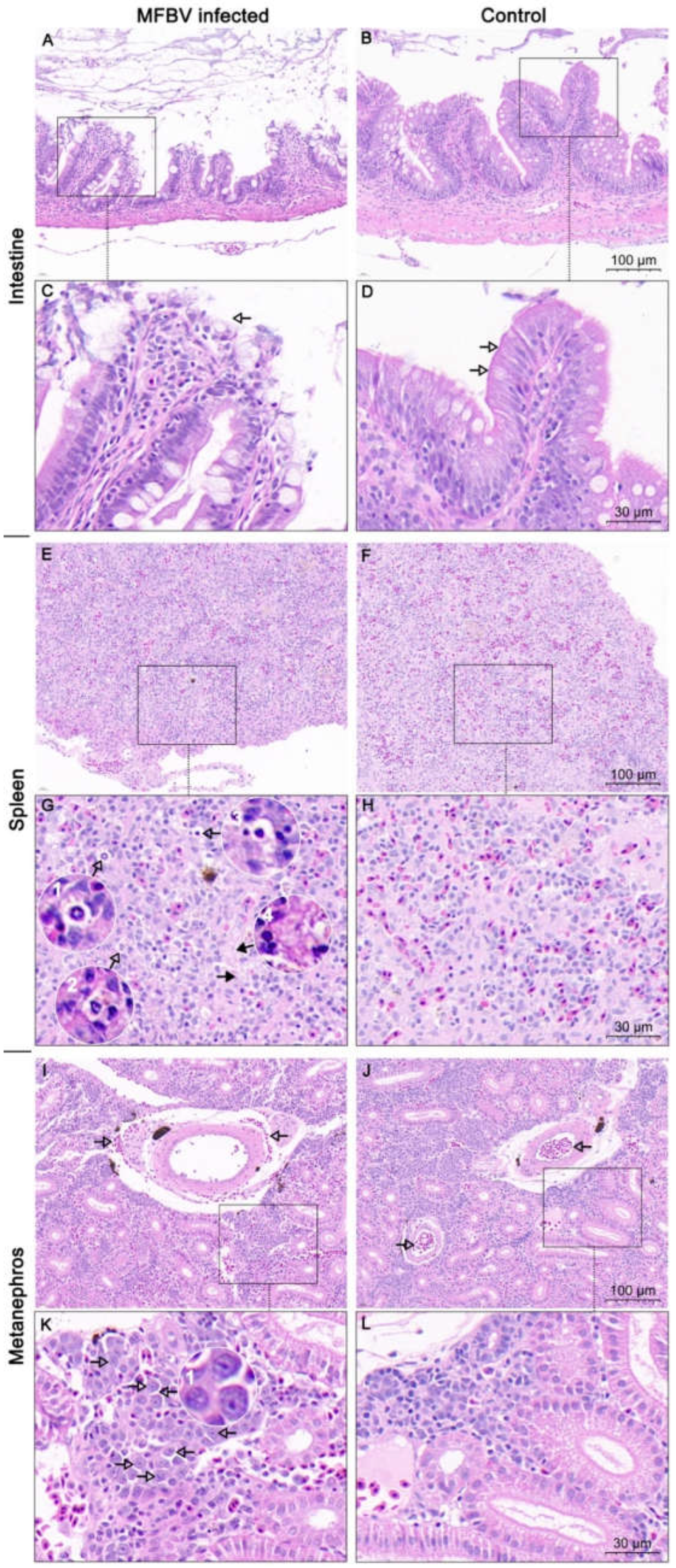

Figure 9.

H&E staining analysis of MFBV-infected or healthy mandarin fish tissue sections. (A,C) Intestinal tissue of MFBV-infected mandarin fish, where arrows indicate damage to the simple columnar epithelium layer and rupture of goblet cells. (B,D) Intestinal tissue of control mandarin fish, displaying a complete mucosal layer, simple columnar epithelial cell layer, and visible goblet cell vacuoles. (E,G) Spleen tissue of MFBV-infected mandarin fish. The hollow arrow and magnified view (G1–G3) indicate nuclear condensation (pyknosis), while the solid arrow and image (G4) show nuclear loss and vague cellular outlines (karyolysis and cell death) and the areas that loss structure detail. (F,H) Control mandarin fish spleen tissue. (I,K) Arrows in (I) indicate red blood cells surrounding the artery. Arrows in (K) and magnified view (K1) indicate abnormal chromatin condensation. (J,L) Control kidney tissue, where blood cells are contained within the arteries (arrow) and nuclei morphology appears normal.

Figure 9.

H&E staining analysis of MFBV-infected or healthy mandarin fish tissue sections. (A,C) Intestinal tissue of MFBV-infected mandarin fish, where arrows indicate damage to the simple columnar epithelium layer and rupture of goblet cells. (B,D) Intestinal tissue of control mandarin fish, displaying a complete mucosal layer, simple columnar epithelial cell layer, and visible goblet cell vacuoles. (E,G) Spleen tissue of MFBV-infected mandarin fish. The hollow arrow and magnified view (G1–G3) indicate nuclear condensation (pyknosis), while the solid arrow and image (G4) show nuclear loss and vague cellular outlines (karyolysis and cell death) and the areas that loss structure detail. (F,H) Control mandarin fish spleen tissue. (I,K) Arrows in (I) indicate red blood cells surrounding the artery. Arrows in (K) and magnified view (K1) indicate abnormal chromatin condensation. (J,L) Control kidney tissue, where blood cells are contained within the arteries (arrow) and nuclei morphology appears normal.

Figure 10.

Titer determination of disinfectants treated MFBV virus suspension within SCK cells. Virus-induced CPE positivity is indicated by pink dots, while negativity is indicated by green dots. The data were obtained from three biological replicates, and the results were consistent across experiments.

Figure 10.

Titer determination of disinfectants treated MFBV virus suspension within SCK cells. Virus-induced CPE positivity is indicated by pink dots, while negativity is indicated by green dots. The data were obtained from three biological replicates, and the results were consistent across experiments.

Figure 11.

The MFBV suspension was incubated for 90 days, and viral titers were measured at various time points to evaluate the stability of MFBV. Viral titers are expressed as TCID50/ml. Each titer value represents the mean ± SE derived from three biological replicates. Partial SE is hidden within the data points.

Figure 11.

The MFBV suspension was incubated for 90 days, and viral titers were measured at various time points to evaluate the stability of MFBV. Viral titers are expressed as TCID50/ml. Each titer value represents the mean ± SE derived from three biological replicates. Partial SE is hidden within the data points.