2.3. Ion Optic System Modeling

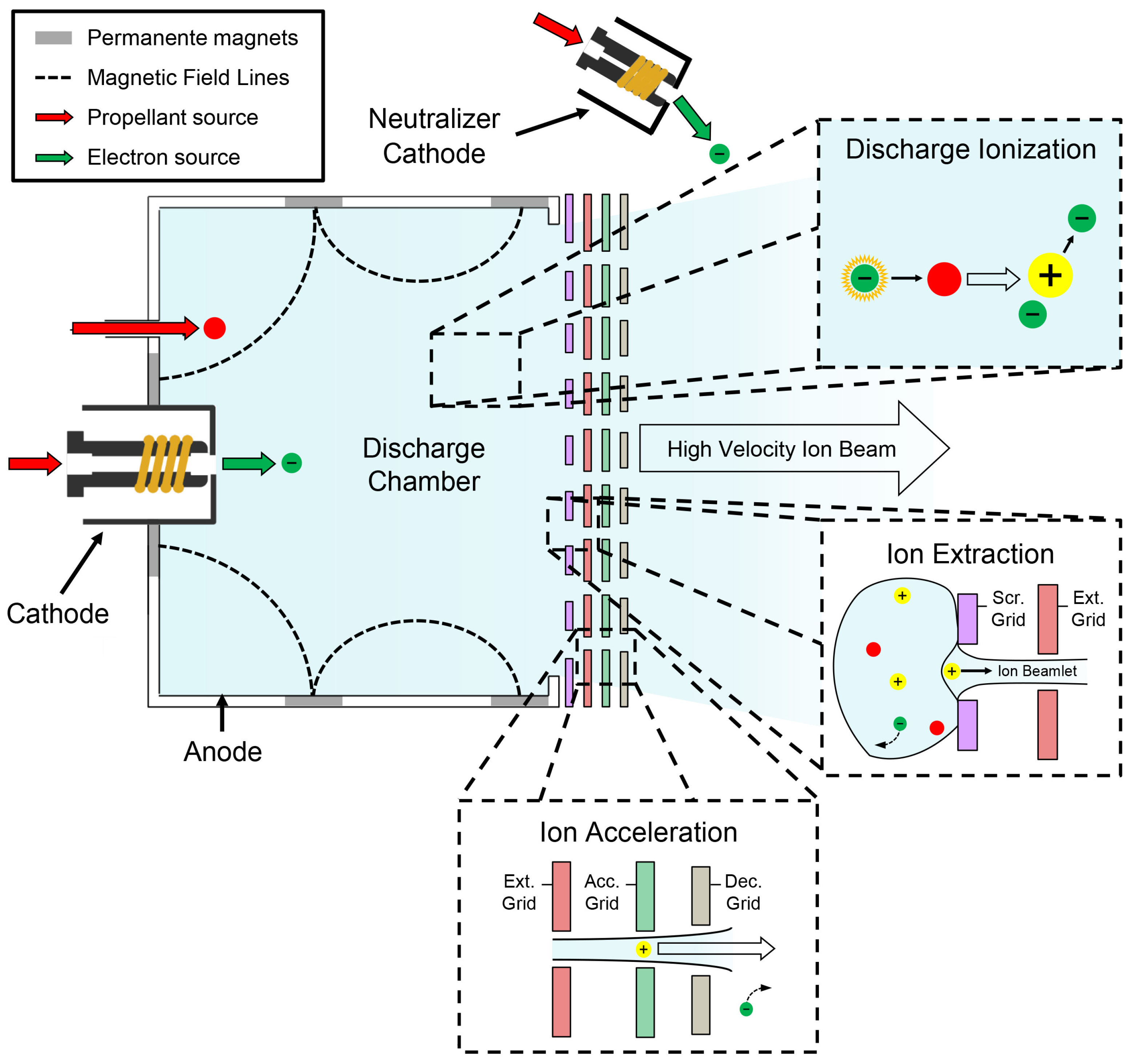

Ion acceleration and thrust production in a GIT occur through the use of electro-polarized grids. The design of such grids results from a trade-off between lifetime, size, and performance. In general, the main factor turns out to be durability, since ion thrusters must operate for months or years. The aim of the grids is to extract ions from the plasma and accelerate them, while minimizing the impacts of ions on the shielding grid and the loss of neutral atoms out of the chamber, in order to maximize the mass utilization efficiency, as described in the following sections.

The main parameters that define the grid geometry are the grid thickness, distance between grids, the diameter and number of holes. These parameters are expressed considering the confinement of neutrals and the minimization of impacts between ions and accelerating grid. In particular, one of the advantages of a Dual-Stage ion optics system is the possibility of obtaining highly focused ion beams with rather low divergence values. In DSGITs, although the extraction and acceleration processes occur in different regions (in the first and second grid gaps, respectively), if a well-collimated jet is desired, the magnitude of the acceleration process will influence the requirements of the extraction process in terms of the optimal perveance ratio

(Equations

7, Equations

8). This effect can be easily understood by representing the grids as electrical lenses. An electrode separating two regions with different electric field strengths is equivalent to an electrostatic lens with focal length

f explicated in Equation (

2).

In Equation (

2),

V is the ion energy at the position of the grids, while

and

are the electric fields in the extraction and acceleration gaps, respectively. Consequently, using Equation (

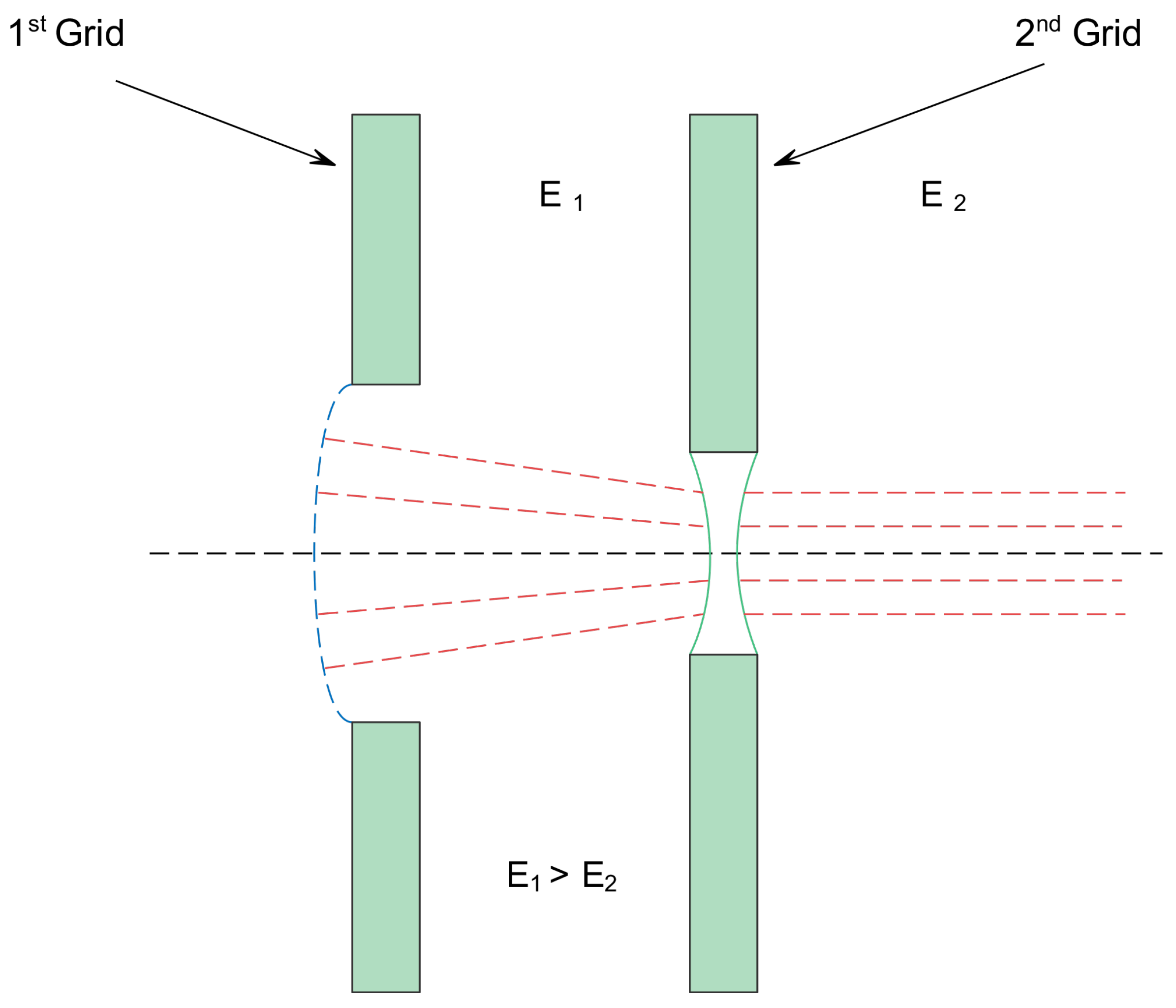

2), it can be seen that in a conventional GIT extraction system, as visible in

Figure 5, the divergent lens is the second grid that balances the effect of sheath shape, ideally producing a perfectly collimated ion beam.

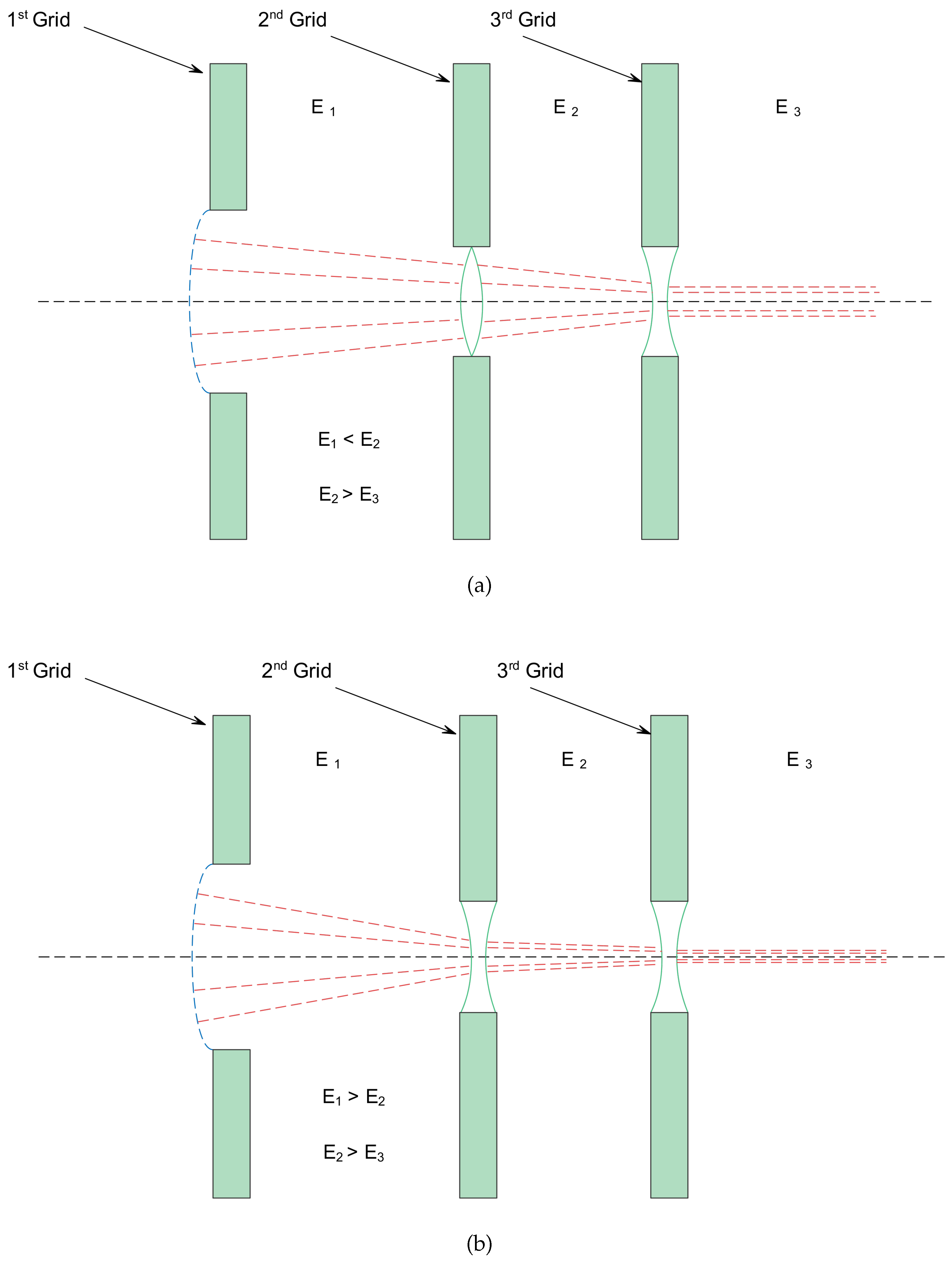

In a dual stage system, the lens corresponding to the second grid can be convergent or divergent according to the relative electric field strength in the first and second gaps, as shown in

Figure 6. When the electric field in the first gap,

, is weaker than the one in the second gap,

, the lens is convergent and a flatter shape of the plasma sheath can be tolerated (compared with a conventional extraction system), leading to higher perveance values and, therefore, higher extracted current densities. Instead, if the field in the first gap,

, is stronger than the one in the second gap,

, the second grid corresponds to a divergent lens. This results in the plasma sheath having to penetrate more into the plasma to have more convergent ion trajectories so as to compensate for the presence of two divergent lenses. As a consequence, there is a reduction in perveance and, therefore, a reduction in the total extracted current.

The change in the optimal perveance can be investigated as a function of the ratio

between the voltage drop applied to the acceleration stage,

, and the voltage drop applied to the extraction stage,

, as can be seen in Equation (

4). For this purpose, the four-grid ion optics model developed in Ref. [

29] is used; this analytical model, based on the theory of linear optics, allows the calculation of the divergence of the ion beam as a function of grid geometry and applied voltages.

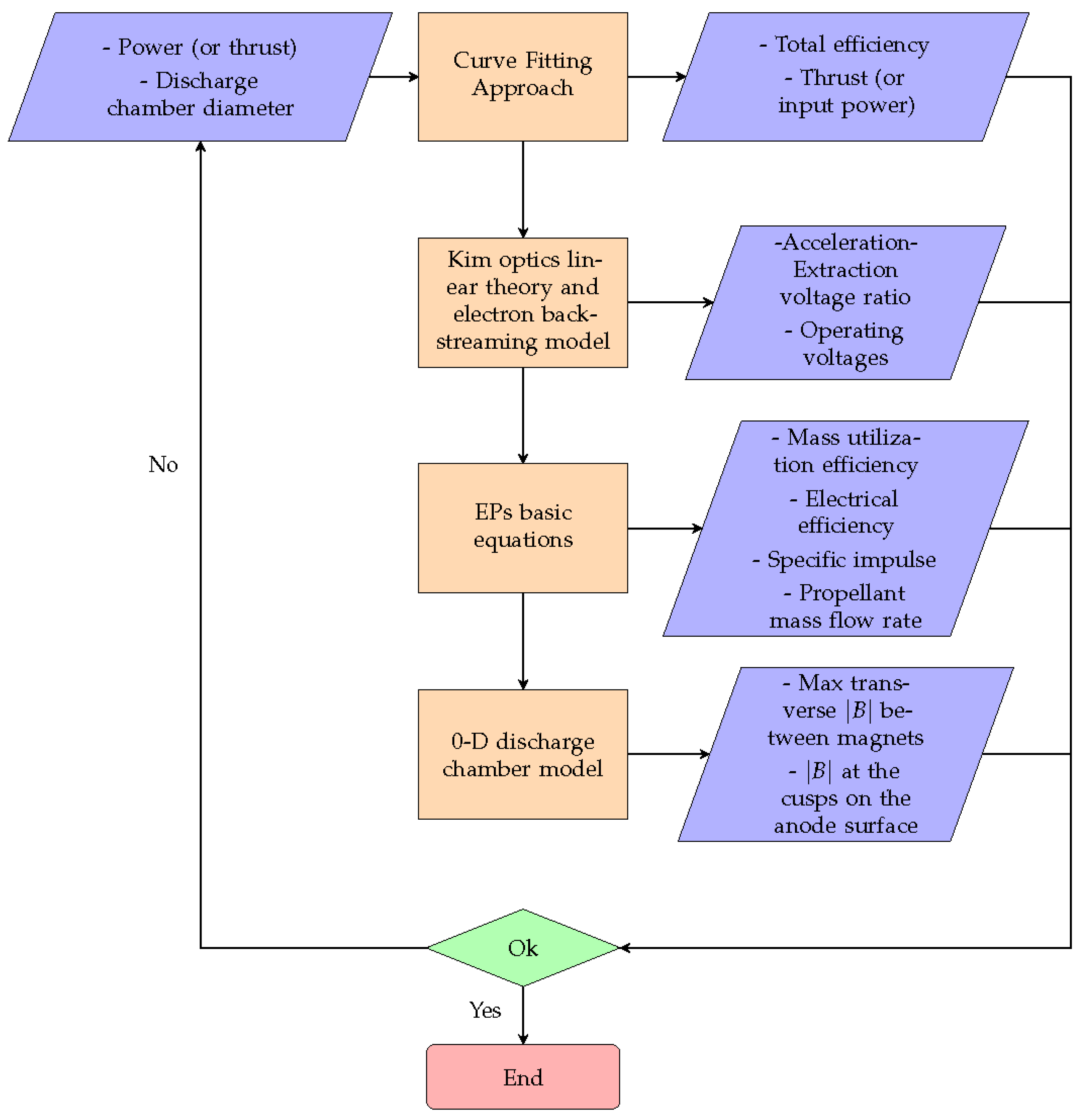

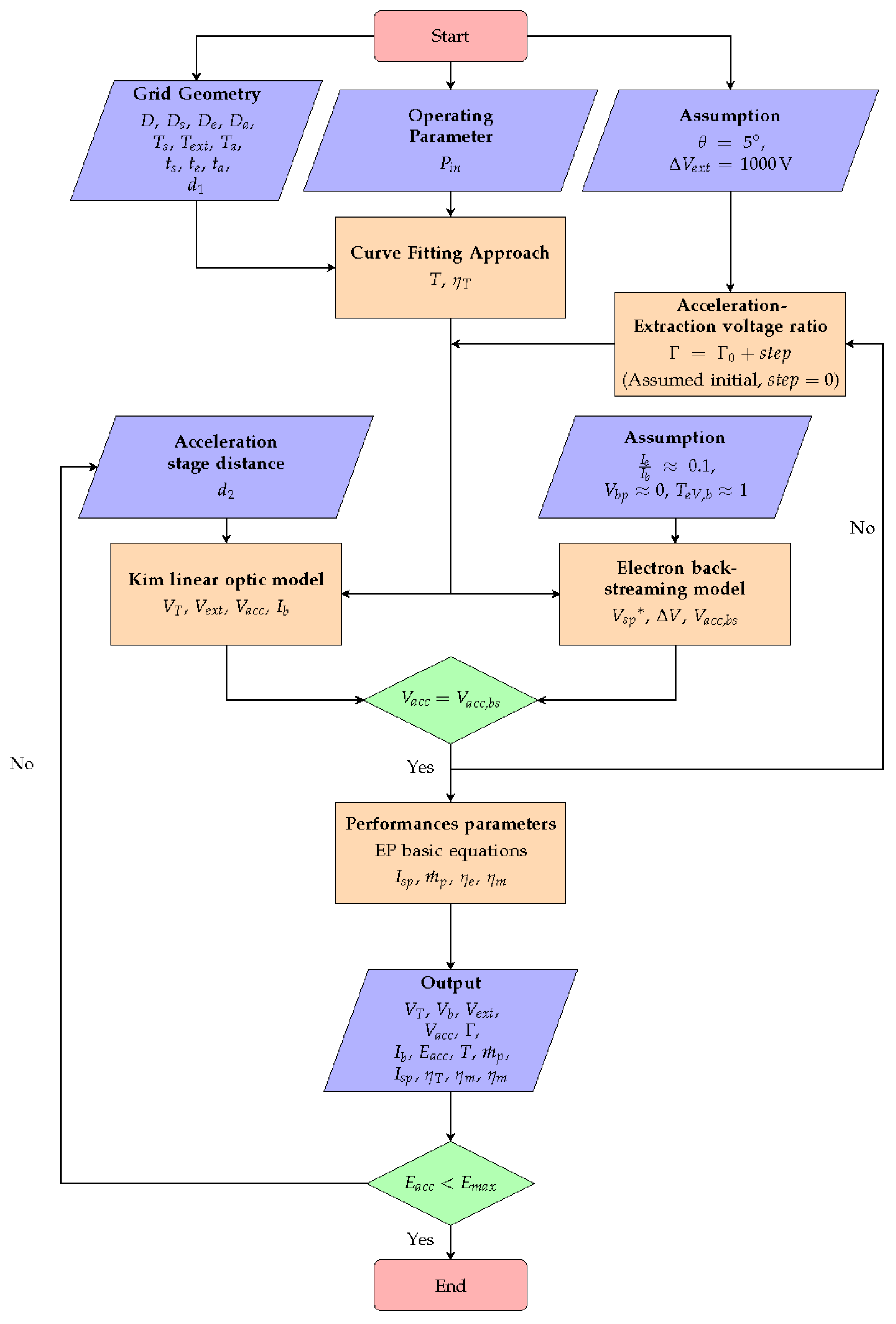

Figure 7 represents the flowchart showing the logic of ion optics’ parameters determination.

The linear optics model proposed in Ref. [

29], hence, allows the beam divergence to be defined by Equation (

3).

In Equation (

3),

is the ratio of the acceleration voltage

to the extraction voltage

,

the ratio of the acceleration gap to the extraction gap and

S the ratio of the screen grid aperture radius to the extraction gap.

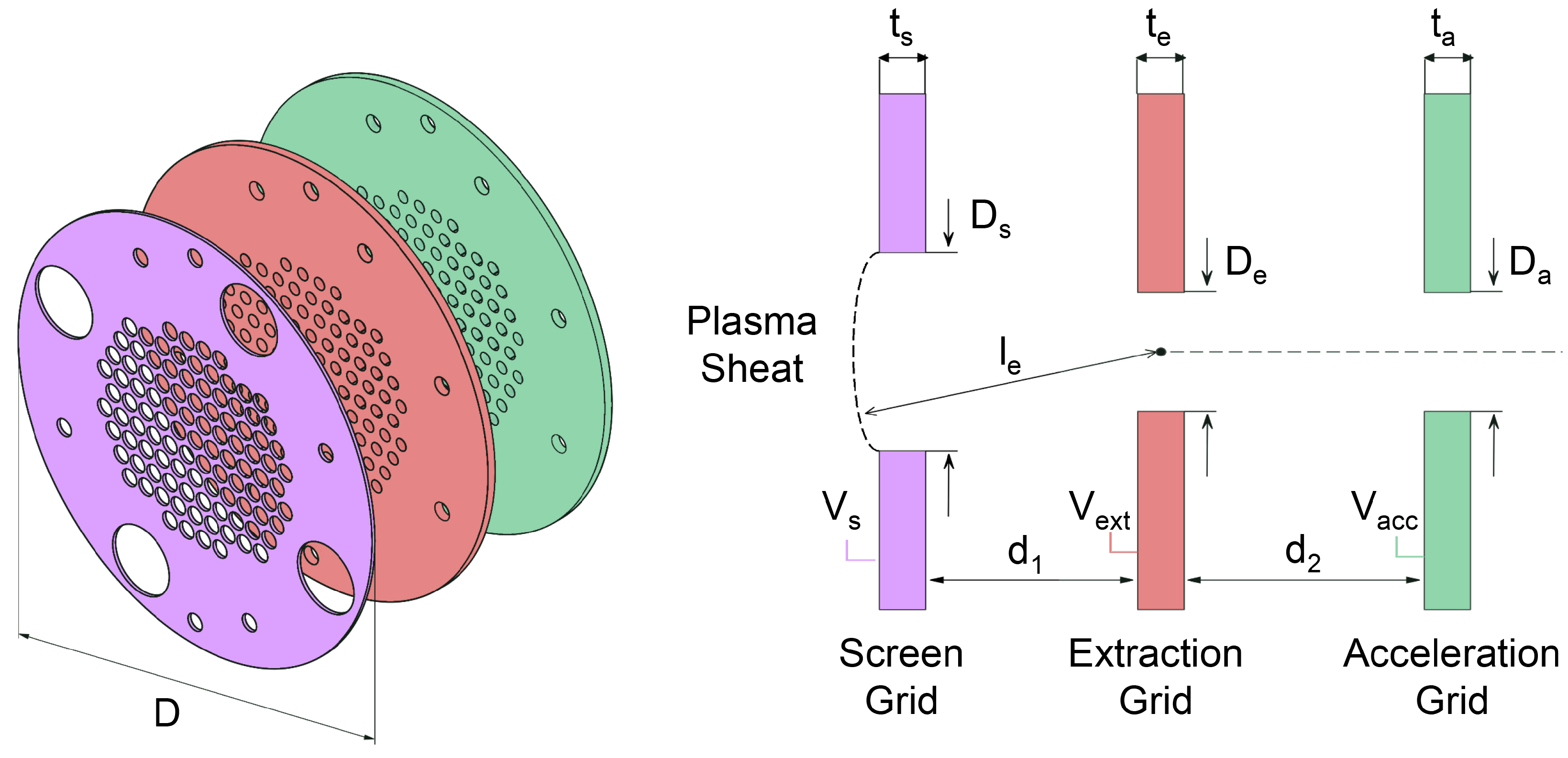

Given the grid geometry in

Figure 8, using Equation (

3), and varying

, it is possible to obtain the optimal perveance ratio (

) to produce a beam jet with almost zero divergence.

To be able to understand the ion extraction process and its influence on a GIT performance and lifetime, the perveance of an extraction system is defined in Equation (

7).

Where

I is the extraction current and

is the extraction voltage drop (

). The perveance results to be strongly related to space charge effects on the extraction of a ionic current and its maximum value is governed by the Child-Langmuir equation, reported in Equation (

8).

Consequently, in Equation (

8)

refers to the Child-Langmuir limit perveance, while

,

e and

M are, respectively, the vacuum dielectric constant, the electron charge and the mass of the extracted ions,

is the first grid aperture diameter and

the gap between the first two grids of the extraction system. Assuming a constant extraction voltage

(

), the lower the specific impulse

is, the lower the optimal work perveance and the extracted current are. In particular, the optimal value of

for a Dual Stage ion engine decreases below the one of a conventional GIT for values of

less than 0.7-1.5. This reduction in working perveance could be balanced by reducing the ratio

between the distance of the first and second stages. However, decreasing the value of

means either increasing the gap of the first stage, causing a decrease in the maximum perveance

, or decreasing the grid spacing in the acceleration stage. It should be noted, however, how the minimum grid gap is limited by the maximum electric field

(≈ 4

/

for Molybdenum) that can be applied between two grids before the arcing occurs [

30]. These two limitations discussed above are applied in the identical manner to both extraction stage (screen and extraction grid) and acceleration stage (extraction and acceleration grid), so it is possible to verify the value of the relative electric fields by Equations (

9) and (

10).

The parameter

in Equation (

9) is the sheath thickness or gap equivalent of the extraction stage which can be defined by Equation (

11).

It should be noted from the Equation (

12) that the maximum current density of the extractable beam is found to be related to the electric field in the extraction stage gap

.

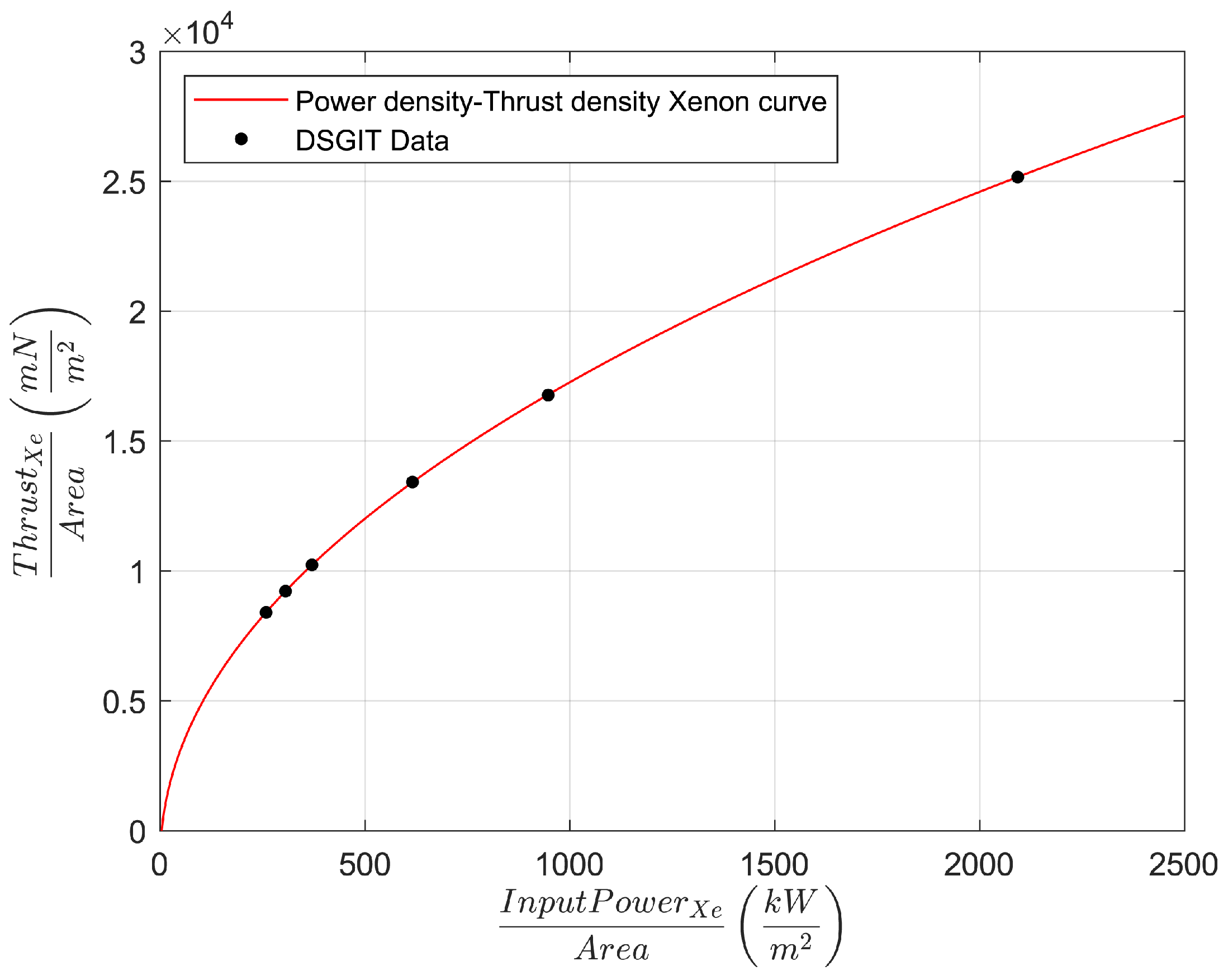

The thrust density is likewise proportional to the electric field of the DSGIT extraction stage, as can be observed from Equation (

13).

In Equation (

13), the term

is the ion acceleration potential in the dual stage system, which corresponds to the difference between the beam voltage

and twice the absolute value of the acceleration grid potential

.

Hence, given the thrust density

and the ratio of voltages

, it is possible to obtain the extraction grid voltage

and the screen grid voltage

, respectively.

The acceleration grid voltage, calculated by the voltage ratio

and the potential difference of the extraction stage

, must be compared iteratively in order to determine the optimal value of perveance with analytical model of electron backstreaming for ion thrusters [

3,

31]. This analytical model, shown in Equation (

17), enables the explication of the backstreaming limit, coinciding with the minimum potential of the acceleration grid, which allows the backstreaming current to be reduced to a specific percentage of the beam current

.

In Equation (

17),

is the minimum local potential (or “saddle-point” voltage) required for the electronic backstreaming limit. It is quantified in terms of the ratio of the backstreaming current to the beam current. The term

represents the potential difference between the beam axis and acceleration aperture wall, while

B is a geometric factor that considers the acceleration grid geometry, as shown in Equation (

20).

In Equation (

18),

corresponds to the plasma potential into the beam, which, as a first approximation, can be set equal to 0

;

is the beam plasma electronic temperature in eV (usually of the order of 1-2 eV). In Equation (

19),

represents the beam diameter obtained through the analytical model developed in Ref. [

29]. With this model the beam radius can be estimated along the ion beam trajectory.

In Equation (

21),

is the radius of the ion beam at the exit of the last grid and

is the radius of the initial beam. In Equations (

22)-(

24) are reported, respectively, the

U term, related to the Acceleration-Extraction voltage ratio

,

corresponding to the measurement of boundary curvature and

to the effect of plasma boundary curvature in extraction stage [

30].

The comparison of the acceleration grid voltage, obtained from Equations (

4) and (

17), allows to determine the optimal value of perveance,

, and the ratio of voltages,

, for a given input power and a fixed value of beam divergence.

2.4. Performances Calculation

Once the grid voltages have been obtained by Kim’s linear optics model [

29] and the electron backstreaming model [

31], it is possible, through the general equations of electric propulsion, to determine the performances of the thruster.

The curve-fitting approach has enabled the determination of the main performance parameters, such as thrust

T (or input power

) and total efficiency

. In GITs there are different energy loss mechanisms that can be summarized in three main coefficients

,

and

. The first is the mass utilization efficiency

, which takes into account the amount of neutrals that escape from the discharge chamber without being ionized and can be expressed by using Equation (

25).

In Equation (

25),

is the total propellant mass flux and

is the mass flux of ions, thus the mass utilization efficiency represents the fraction of the total ionized propellant flux. This expression is valid in the case of singly ionized particles, but in the presence of many multi-ionized particles, Equation (

25) must be redefined with a correction factor. Sometimes it is useful to define a discharge chamber propellant utilization efficiency

by dividing

by the fraction of propellant injected into the chamber, as shown in Equation (

26).

In Equation (

26),

represents the neutralizer propellant flow rate outside the chamber and is assumed, as a first approximation, around 10% of the total mass flow rate of the thruster,

. The second efficiency is the electrical one

, defined in Equation (

27) as the ratio of the beam power to the total input power.

Equation (

29) provides the last efficiency, the total thruster one

, denoted as the jet power divided by the total power. In this expression

is a correction factor related to beam divergence and double ionization in the thruster; its value can be estimated experimentally with Equation (

28) or by codes that calculate the beam divergence and consider the propellant multi-ionization.

Combining the previous relations Equation (

30) can be easily obtained. It can be observed that, for a given input power and total efficiency, an increase in specific impulse results in a decrease in thrust of the same amount.

As Equation (

30) shows, a trade-off between thrust and specific impulse must be achieved in the development of an ion thruster, thus the efficiency needs to be increased. It is also important to compute the power loss in Equation (

31), which is not exactly an efficiency but still represents a power loss.

The discharge loss

indicates the cost of ion production, specifically it represents the power required to generate unit ion beam current. Since it is a power loss, it should be as small as possible. In Equation (

32), it is reported the discharge current

, produced inside the discharge chamber, in which it can be seen the dependence on net beam voltage

, discharge voltage

and electrical efficiency

.

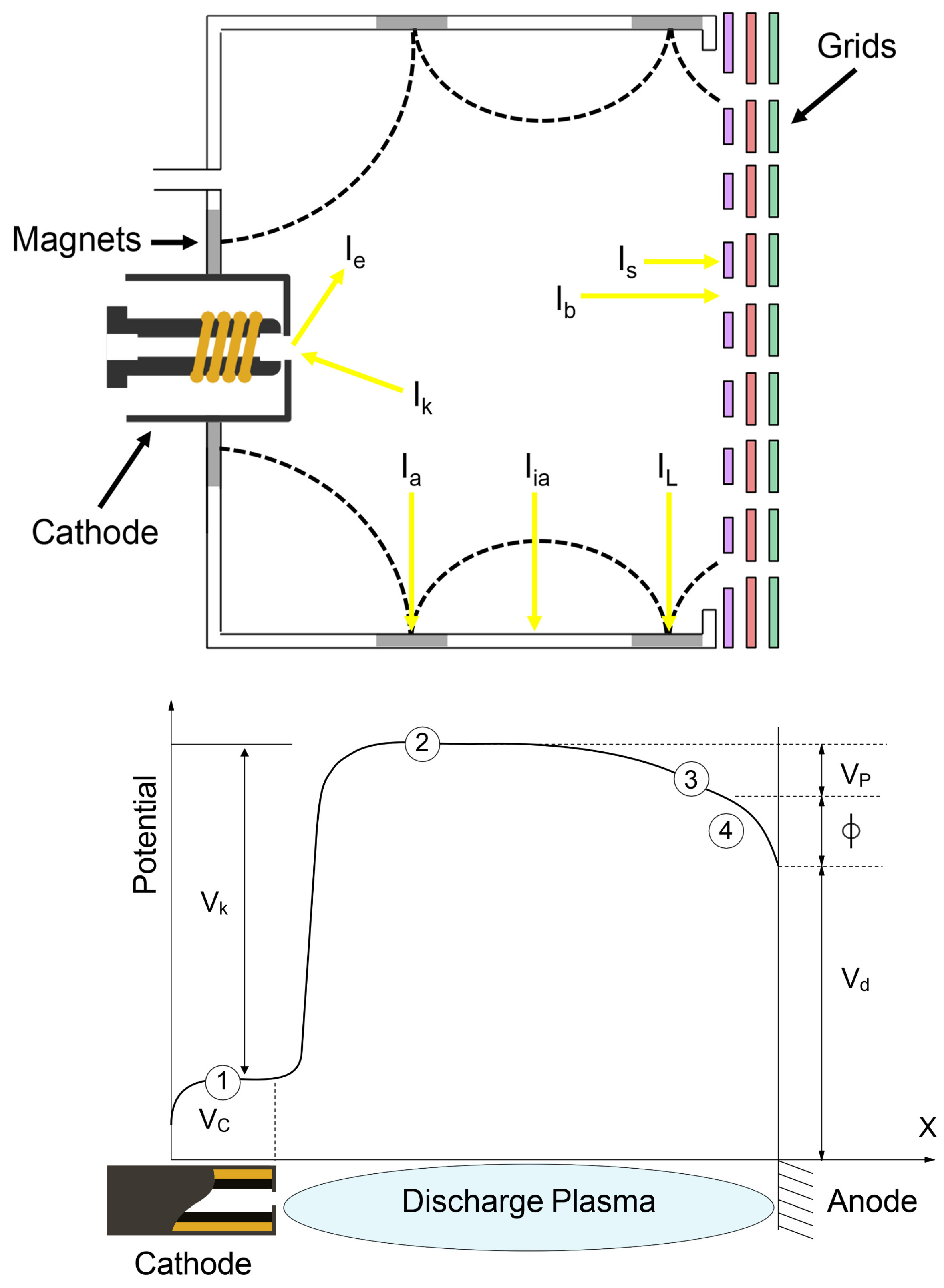

2.5. Discharge Chamber Model

Analytical equations, derived from Goebel and Katz 0-D model [

3], allow the determination of the maximum transverse magnetic field between magnetic rings and magnetic field strength in the cusps along the anode wall. These values are used to size magnets arranged in a ring cusp magnetic field configuration, which is one of the most effective solutions for electron and ion confinement [

32,

33].

In the model, a homogeneous plasma is assumed within the volume confined by the magnetic field, an assumption that is generally valid except for the area near the cathode plume. Therefore, the predictions of the model is expected to deviate only marginally from the experimental results.

The main equations are given by the power balance in the discharge chamber and in the overall thruster expressed respectively in Equations (

33) and (

34).

In Equation (

33), the term

represents the power in the discharge chamber. This power, as shown in Equation (

35), depends on the current emitted by the hollow cathode and the voltage to which the electrons inside it are subjected. The second term,

, given by Equation (

36), represents the output power of the ionization chamber, considering the phenomena of ion production and neutral excitation, as well as electrode losses, related to the power

. Equation (

34) considers the energy balance of the entire thruster, where

represents the input power of the thruster, assumed to be the model DoF. On the other hand,

, defined in Equation (

37), includes not only the power required for the ionization chamber, but also the power destined for the electrodes.

In Equation (

35),

is the electron current,

the discharge voltage,

the cathode voltage drop,

the sheath potential relative to the anode wall,

the plasma potential drop related to the electron temperature

(see Equation (

38)).

In Equations (

36) and (

37), the first term

represents the power to produce ions, where

is the ion production rate and

is the ionization potential. The second term

refers to the power to excite neutrals, where

is the neutral excitation rate and

is the average excitation potential (

and

, for Xenon, are respectively

eV and 10 eV). As for the production rate of ions

and the neutral excitation rate

are described respectively in Equations (

39) and (

40).

In these last two Equations,

is the neutral density,

the electron density,

the primary electron density,

e the electron charge and

V the plasma volume inside the discharge chamber. The first terms within the brackets,

in Equation (

39) and

in Equation (

40), represent respectively the ionization and the excitation reaction rate coefficients, i.e., the cross section averaged over the Maxwellian electron velocity distribution function.

The second terms within the brackets,

and

, are respectively the ionization and excitation cross section averaged over the primary electron velocity, depending on the electron temperature. By assuming mono-energetic electrons, the second term in brackets can be expressed as a product of the cross section

and the primary velocity

, considered constant [

3].

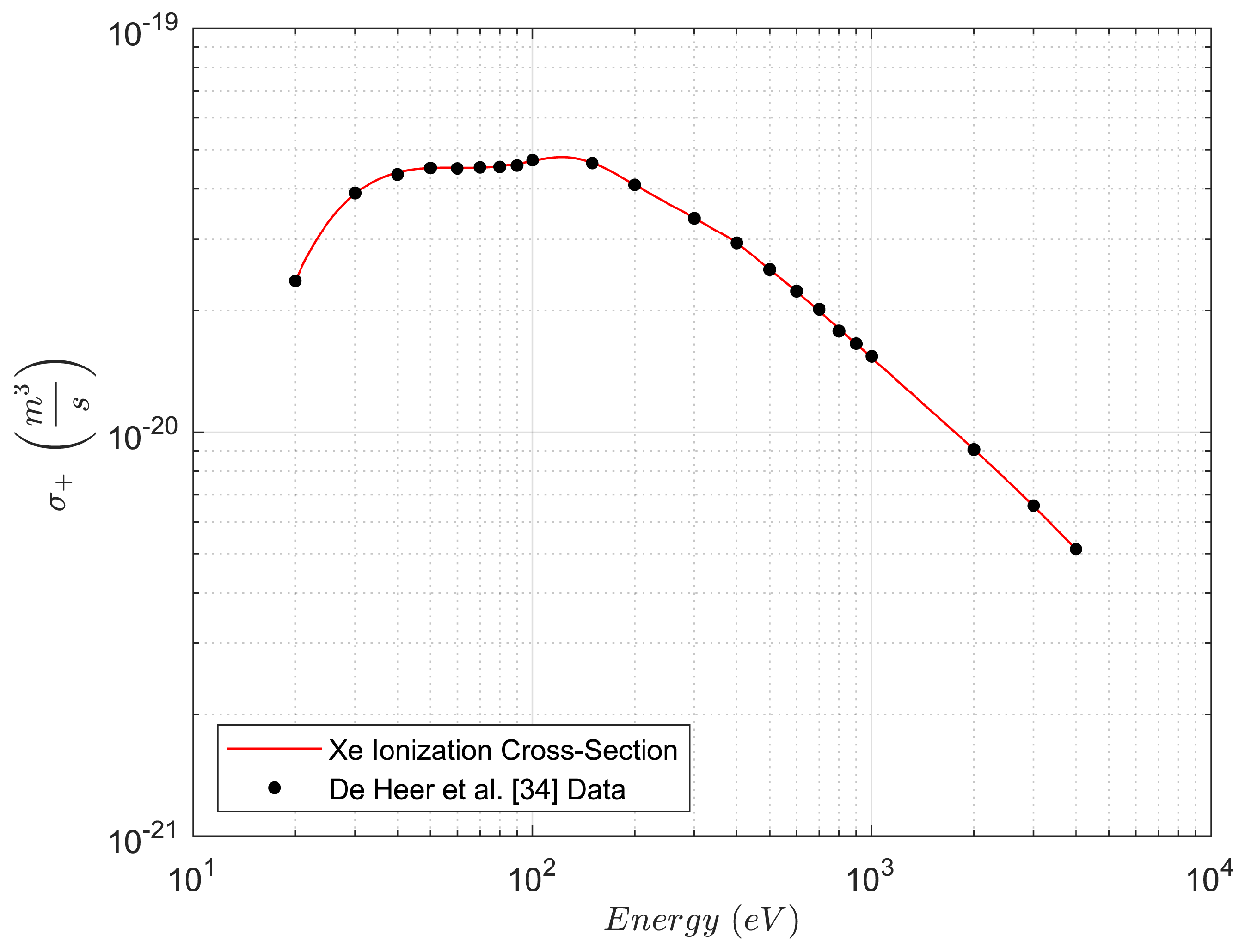

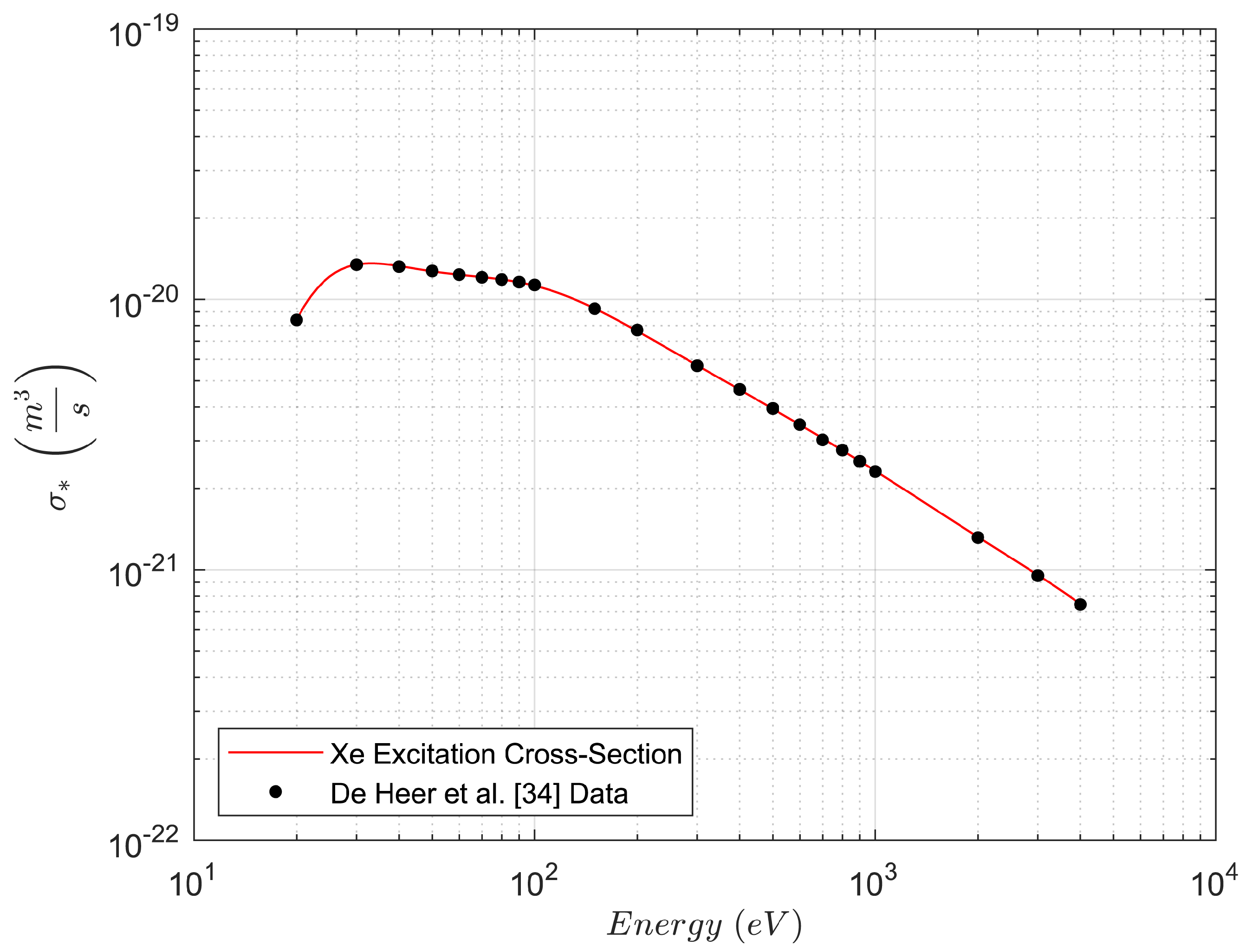

In the case of DSGIT Xenon-fed:

The ionization and excitation reaction coefficients expressed as a function of electronic temperature, can be computed by the fits reported in Ref. [

3];

Ionization and excitation cross-sections are obtained as a function of the primary electron energy

. Equation (

41) is a seventh-order Gaussian fit, derived from the study of De Heer et al. [

34] and using the coefficients given in

Table 2 and

Table 3. These curve fits, shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, are in accordance with experimental data, yielding an R-squared value of 1, and operate in the energy range 20-4000 eV.

For the calculation hereinafter, the energy of the primary electron,

, is set to 20 eV, thus the values of cross sections are calculated at the same energy level,

E, by using Equation (

41).

The remaining terms in the Equations (

36) and (

37), describe the power lost to the electrodes and to the anode wall due to ions recombination and electrons loss.

the ions on the screen grid,

the ions back to the cathode,

the ions beam current,

the ion current lost to the anode,

the electron current from the plasma that go to the anode,

the primary electron current lost to the anode and

the plasma electron energy lost to the wall, expressed as

. Furthermore, in the Equation (

37),

corresponds to the ion beam voltage and

to the potential drop in the extraction stage. The term

is added, compared with the conventional GIT equations [

3], in the power balance of the overall thruster to consider the decoupling effect of the extraction and acceleration process in the DSGIT.

As concerns the currents, they have to satisfy the balance Equations (

42)-(

45).

Regarding magnetic confinement, it is decided to focus on the currents

,

and

, found in Equations (

42)-(

45), due to their dependence on the magnetic field. Equations (

42) and (

43) represent the conservation of particles flowing to the anode and the current emitted from the hollow cathode, respectively, while Equations (

44) and (

45) express the rate of ion production. The

term is put equal to zero, given the negligible values it generally assumes.

Figure 11 shows the defined currents and potentials in the discharge chamber.

Equation (

46) allows to define the primary electron current lost directly to the anode wall at the cusps of the magnetic field, since the magnetic field lines are perpendicular to the surface.

The term

is the primary electron density,

the primary electron velocity and

the loss area at anode expressed in the Equation (

47).

As reported in Equation (

48),

is the total length of the magnetic cusps in the azimuthal direction given by the sum of the single length of the cusps.

The value

is the Larmor radius shown in the Equation (

49) and influenced by

, which is the magnetic field strength at the cusp of the anode wall.

As can be seen,

and

are inversely proportional, thus the higher the magnetic field, the lower the loss area; therefore, the probability,

P, that a primary electron undergoes a collision without being lost at the anode is higher, in agreement with the Equation (

50).

The term

is the neutral density,

the total inelastic collision cross-section for the primary electrons and

V the discharge chamber volume. Typically, most of the electrons lost at the anode magnetic cusps are plasma electrons, the so-called secondary electrons. The plasma electrons current lost to the anode magnetic cusps can be expressed by the Equation (

51).

In this expression,

is the electron density in the plasma,

the electron temperature,

m the electron mass,

the anode sheath potential and

a hybrid anode area reported in Equation (

52).

In Equation (

52),

represents the hybrid Larmor radius, which depends on the magnetic field strength

B at the magnetic cusps on the anode wall; while

and

are respectively the electron Larmor radius and the ion Larmor radius, explicated in the Equations (

53) and (

54).

The ion current to the anode wall is expressed in the Equation

55, where

is the total surface area of the anode exposed to the plasma and

the confinement factor.

The factor

is related to the presence of magnetized electrons that influence the motion of ions, causing a reduction of the Bohm current toward the wall area between the cusps.

The confinement factor

corresponds to the ratio of the transverse ion velocity

to the Bohm velocity

, as reported in Equation (

56). Furthermore, it depends primarily on the magnetic field configuration since the transverse ion velocity

is expressed, as seen in Equation (

57), as a function of the maximum transverse magnetic field

. The latter induces a reduction in the expected ion flux to the anode, which also directly affects the ion velocity. As a result, ions are conserved because those that do not flow to the anode wall, due to the transverse magnetic field, impact toward the grids, i.e. in a region of no confinement.

In Equation (

57),

represents the electron-ion collision frequency,

is the sum of the electron-neutral collision frequency

and the electron-ion one

,

the electron mobility and

l the diffusion length. The latter term, corresponding to the transverse location of the maximum magnetic field magnitude between magnets, in the case of the ring cusp magnetic field, can be determined with good approximation as

, where

d is the distance of the magnets.

Equations (

58)-(

60) describe the collision frequencies and electron mobility.

The term

represents the Average Maxwellian inelastic cross-section, i.e. the measure of the probability of a particle interaction in a gas or plasma. This cross-section is determined as a function of the electronic temperature

and depends on the selected propellant. Curve fits valid in the electronic temperature range 0.1-100 eV, can be found in Ref. [

35] .