1. Introduction

Due to the similar origins of Schrödinger’s wave equation for wave function propagation and the propagation of light waves scalar diffraction theory (SDT), it has long been understood that these two theories share a common formalism.[

1] This common heritage allows one to treat time and space in a similar fashion, due to the existence of well-defined Fourier transforms and corresponding spectra for both spatial and temporal signals. Therefore, quantum wavefunction propagation can be formulated as a recursive Fourier transform in both space and time, similar to the image formation process in scalar diffraction theory.[

2]

Having established the Fourier transform at the foundation of wave function propagation, it is immediately evident that propagation intervals are irreducible. In particular, temporal irreducibility arises from the time-energy duality, where a temporal interval such as that corresponding to propagation of an optical signal through a fiber is encoded as a spectrum in the frequency domain. Such a spectrum corresponds to an entire interval, and not any subdivision of the interval. In fact, it’s readily shown that any attempt to define a smaller sub interval introduces spectral artifacts which uniquely define the geometry of the perturbation.

Irreducible time intervals have implications for both the foundations of quantum mechanics and interpreting experimental results, as well as suggesting new experimental setups. It should be noted that the words “irreducible” or “indivisible” don’t mean that one cannot make a measurement at an intermediate time. Rather, it means that making such a measurement fundamentally changes the interval of time, and the partial segments that are generated do not sum to make up the original whole. In other words, the whole is abandoned (the original state is altered) when the parts are defined.

Time evolution has been studied in quantum mechanics in contexts similar to space evolution, namely diffractive effects [

3], interference effects [

4], and entanglement [

5]. Applications include femtosecond laser pulses [

6][

7], high harmonic generation [

8], single photon generation [

9], spontaneous parametric down conversion, photon arrival time, quantum computing and quantum sensing,[

10] [

11] [

12] and solitons.[

13]

In

Section 2 a theoretical foundation is established for the remainder of the paper. In

Section 3 the main argument is conveyed for the irreducibility of temporal intervals, and illustrated through an example of time-bin measurements. In

Section 4 various well known experimental setups are analyzed with respect to irreducible temporal intervals. In

Section 5 foundational questions of ontology and philosophy are examined. In the closing sections a brief summary is provided as well as an appendix outlining the relationship of scalar diffraction theory and quantum wave function propagation.

2. Background

2.1. Definitions and Notation

The following definitions and notational conventions are used throughout the paper.

2.2. Representing Time in the Frequency Domain

We can gain an intuition for the effect of subdividing a temporal interval by considering the effect of truncating an audio signal at a sharp cut off time. The spectrum of the audio signal picks up oscillations known as Gibbs ringing. Alternately, in digital photography one can obtain the two-dimensional spectrum of a two-dimensional image, encoding the rapidity of change in the contrast of the image over space. Certain digital filters cut out regions of the spectrum for the purpose of modifying the entire digital image in space. In the simplest case, a sharp cut off in the spectrum causes oscillations or ripples in the contrast of the image in two dimensional space.

Similarly, in quantum wavefunction propagation, subdividing a temporal interval introduces oscillatory artifacts in the frequency domain, emphasizing the coherence of the whole. Conversely to the way in which interference effects in a double slit system depend upon indistinguishibility of paths of a photon, a time interval is irreducible if one cannot distinguish, even in principle, between two consecutive segments of a path allowing for coherence and interference effects.

Frequency space (parameterized by ) plays a central role in this perspective. The time evolution of a quantum system is governed by the phase structure of -space, rather than by explicit time parameters. This decentralization of time reinforces the spectral view of quantum dynamics, where discrete measurement intervals (rather than continuous evolution) define the system’s trajectory.

In this approach, there are two notions of time. The first is unitary time, which advances continuously, allowing us to calculate how a system will evolve into the future. However, unitary time is unmeasurable; it enters the theory as the parameter of integration in the Fourier transform, and thus has no definite value. Instead, what we can measure are discrete coordinates or durations, which are not variables but constant data points which have their relevance as oscillation frequencies in the frequency domain. Put another way, because time doesn’t exist as an explicit variable in the frequency domain, it (time) cannot evolve continuously because the spectrum of an instantaneous signal is not well-defined. The coordinates of an interaction, on the other hand, can readily be represented in the frequency domain, where they encode the frequency of oscillation of the spectrum.

This offers a fresh perspective for interpreting physical phenomena, such as attosecond light pulses or quantum coherence, and could have implications in fields like ultrafast optics, quantum mechanics, and even cosmology.

2.3. The Interaction of Signals

The close parallels between the formulation of quantum mechanics and scalar diffraction theory is reviewed in

Appendix A. This equivalence can be readily seen (in one spatial dimension) using the propagator formulation to translate a free particle wavefunction,

where

is the momentum operator, so that the transition amplitude is

where

is a phase. It is evident that space translation via Fourier transform is the result of a phase factor being applied in

k-space, which can also be written as convolution in the

x domain,

, where

h is the impulse response of the `system’.

Relatedly, in signal processing, translation (shifting) of temporal signals in the physical domain corresponds to multiplication in the frequency domain, as described by the convolution theorem. This relationship is expressed in Equation (5):

Any interaction that alters the temporal properties of a signal can be represented as multiplication in -space.

In an analogous manner, a filter represents a non-local interaction in

-space, achieved by multiplying two signals in

t-space, as shown in Equation (6):

This relationship reflects the dual nature of convolution and multiplication: an operation in one domain has a complementary effect in the other. For example, could represent a carrier signal, and a modulation function applied to the signal. The resulting product in t-space (amplitude modulation) corresponds to a convolution of their spectra in -space.

Combining Equations (5) and (6), a general interaction involves simultaneous effects in both t- and -spaces, reflecting the symmetry of Fourier duality. Shifts in one domain correspond to phase changes in the dual domain, encapsulating the interplay between time and frequency.

As discussed in [

2], given the prevalence of Fourier duality in quantum mechanics, we can take this as an interesting starting point for generalizing the Schrodinger equation and developing a relativistic quantum theory of spacetime wavefunction propagation, unique from quantum field theory. One can develop

wave distributions,

and

, such that unitary evolution takes the form

where

is a function of the potential. This is beyond the scope of this paper.

3. Temporal Irreducibility

Consider the evolution of the energy eigenstates of a particle under a small perturbing potential. Using the time-dependent Schrödinger equation, evolve the initial spectrum

to a new time

,

where the initial state

could be, for instance, a gaussian.

Use the following method to evaluate the expression in Equation (9):

The new expression is

Next, the Fourier transform can be evaluated exactly, using the convolution as in Equation (

2),

where

Here, we started with a photon in the state

parameterized by the initial frequency variable,

. We then reverse engineered the integrand of the time integral into the frequency domain parameterized by

, transformed it into a convolution parameterized by

using the convolution theorem, evaluated that distribution at the measurable value

, and finally integrated over the initial states (

), which amounts to a convolution over that variable. This process is described in [

14].

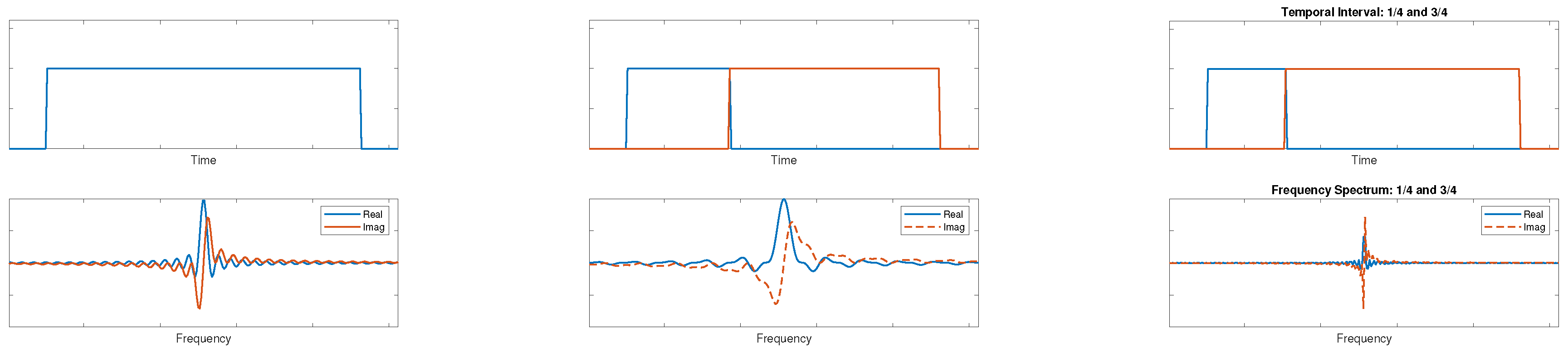

We now divide the time integral in equation into two unequal segments of duration 1/3 and 2/3 respectively. Due to the nature of the Fourier transform and multiplier operator theory, evaluating the time integral into contiguous segments is not the same as a single unbroken interval.

where

The oscillating integrand

is plotted in

Figure 1. Equation (12) should be compared to Equation (11).

The result of reducing the whole interval from 0 to T to two intervals of unequal duration is to introduce oscillations in the spectrum. This represents a measurable distinction between the two cases in the spectrum associated with the path. Interestingly, we have said nothing of the cause of the segmentation or the nature of physical measurement. All we have done is identified potential subsections of a region. Apparently, the very act of identifying or defining such a subdivision affects the spectrum of the particle.

These two cases can be distinguished from each other by their spectral fingerprint. Except for a special case noted below, one can determine whether any sort of disturbance has happened along the journey of duration T by checking if these extra oscillations exist in the spectrum of the detected photons.

Note that in the special case that one divides the temporal interval exactly in half, the spectrum is unaltered.

where a trigonometric identity was used in the last step. This expression matches the result for the undivided interval in Equation (12). We can therefore subdivide an interval exactly in half and have no effect on the spectrum.

3.1. Demonstrating Temporal Irreducibility in a Time-Entangled State

To demonstrate this empirically we can arrange to subdivide a time interval through the use of time bins. In the initial configuration we create one sole time bin, of duration T. This represents a temporal interval of travel for a photon. In a secondary configuration we create two consecutive time bins of the same total duration. All the time bins are represented by rect functions in time. We can readily show that the latter condition generates extra spectral oscillations, distinguishing it from the primary condition. The only difference between these two cases is our ability to distinguish between early arrival and late arrival within that window.

In a typical time-energy entanglement experiment, two identical photons (signal and idler) are generated from a single higher energy photon through the process of spontaneous parametric down conversion (SPDC). The photons are correlated, in that they share a common joint spectral amplitude (JSA), .

Let’s examine the frequency space wave function for the two distinct cases. The time bins will define the basis functions for our representation of the frequency space wave function. Using the standard process we project the JSA onto the time bins in order to determine the coefficients,

. Once those are known, the momentum space wave function is calculated as,

In the first case, with

we have a single bin of duration

which begins at

, so the expression above simplifies to,

Compare this with Equations (11) and (13) for the single photon case.

The spectral distribution of the signal and idler photons is a simple sinusoid with a period of oscillation , decaying away from the origin. This can be measured by counting the number of photons detected at each frequency.

In the second case, we define the early bin from

and the late bin from

, so that

and

. Now there are four combinations for either of the two photons to arrive in either of two time bins. The momentum space wave function becomes

where factors of the form

are included to normalize each

function.

Equation (16) is the extension of Equation (12) to the case of two entangled particles. Comparing Equations (15) and (16) we see that the consequence of dividing the interval into parts is to remove the fundamental oscillation at and introduce harmonics at and in the spectral domain.

By expressing quantum wavefunction propagation in terms of the Fourier transform, we leverage our understanding of dual spaces, namely that the spectrum changes when the domain of integration changes. Because the physical principles of quantum wave function propagation can be derived from the physics of these dual spaces, subdividing the integration domain has a physical effect, and thus the time bin intervals should be considered irreducible.

4. Irreducible Time Intervals in Experiment

The notion of irreducible time intervals fits well within existing experimental results, and also leads to the prediction of new effects.

4.1. Measuring Stellar Distance Using Spectral Oscillations

Perhaps most surprising is the possibility of detecting the duration of travel of light from an astronomical source, by analyzing oscillations in the spectrum of the light emitted from it. When light from a star reaches Earth, Equation (12) predicts that the spectral signature is influenced by the path it has traveled, with oscillatory features in the frequency domain encoding information about the light’s duration of propagation. These oscillations could potentially serve as a unique “temporal fingerprint.” To test the theory, one can perform high resolution spectral analysis of starlight and look for oscillations with a periodicity dependent on the propagation distance, i.e. duration of propagation.

For instance, to detect spectral oscillations of our nearest neighbor, Alpha Proxima (

light seconds away), search for oscillations in the spectrum corresponding to that time window,

In order to measure this effect, spectrographs must be used which achieve a frequency resolution on this order.

Optical frequency combs can provide high resolution measurements in the frequency domain. Early technology could resolve wavelengths up to one part in

, and today’s technology improves that to one part in

.[

15]

This approach, while challenging, offers a novel method for stellar distance measurement using spectral oscillations, and can be compared to traditional methods such as parallax or redshift techniques to verify the theoretical predictions.

4.2. Temporal Modulation of Laser Pulses

In recent decades the creation of chains of very short light pulses has become possible through high harmonic generation in the frequency domain. Attosecond light pulses provide a very short scale application of irreducibility in time.[

6]

It is interesting to think of a train of discrete attosecond pulses instead as a single entity with a temporal structure defined in the frequency domain. In our usual conception, a series of events are considered distinct and causal, i.e. the past pulses can affect the future pulses, but not the reverse. But in this case a series of pulses of extremely short duration in the time domain are generated from a comb in the frequency domain. The temporal characteristics are encoded as a whole within the phase structure of the frequency spectrum, set up more like a standing wave than a series of individual events. One can stretch the definition of the present moment to include a series of events, separated in time and yet occurring, in some sense, during the same moment.

4.3. Temporal Double-Slit

The theory distinguishes between a single contiguous spacetime interval and subdivided intervals. In the temporal domain, this can be tested by splitting a photon’s temporal path into two discrete segments. One can pursue this further by extending the attosecond double-slit experiment performed by Lindner, et al.[

4] Following their procedure, create two high-probability ionization windows within a single laser pulse by subjecting argon gas to femtosecond laser fields. Ionization of the argon atoms is allowed to occur within precisely two short time windows, separated by a brief duration where ionization is certain not to occur. The two time windows act as a double slit in time, producing fringes in the energy spectrum of the ejected electrons.

One can then modify the experiment by introducing a controlled disturbance to the photons prior to ionization (e.g., a weak laser pulse), which has the effect of localizing the photons at a point partway along their path before ejecting the electrons. Because the distribution of kinetic energies for ejected electrons will correspond to the spectral oscillations in the incoming photons, one is predicted to find oscillations in the electronic energy caused by partially localizing the original photon had an intermediate time.[

8].

4.4. HOM Effect

In the HOM effect, two indistinguishable photons are arranged to interfere such that, when the arrival time of the photons match, both photons exit the interferometer through the same output port, reducing the coincidence detection rate between the output ports. The coherence is measured in the so called “HOM dip”, which depends on simultaneous arrival times of the photons with matching spectral characteristics.

Because of the dependency on arrival time, the HOM effect could be a useful way to confirm the relationship between the spectrum of a photon and the temporal subdivisions along its path. Since the temporal characteristics of the photons are encoded in their spectral phases, these phases can be measured by tracking the photon arrival time through the HOM dip.[

16]

Introducing spectral artifacts by subdividing the path of the incoming photons would result in variations of the time of arrival of the photons. The timing could be precisely correlated to the HOM dip in coincidence counts.

4.5. Quantum Cryptography

In this theory, the entire spacetime path contributes to the observed spectrum, meaning the artifacts reflect not just the current state but also the history of interactions. If this is the case, then spectral artifacts caused by the geometry of a signal’s spacetime path can provide direct evidence of tampering, as intermediate measurements or interactions along the path introduce measurable oscillatory patterns or phase distortions in the frequency domain. Unlike traditional methods that rely on probabilistic disruptions or statistical deviations in quantum systems, this approach ties evidence of tampering to spectral signatures that encode the history of spacetime interactions. This fundamentally differs from the traditional approach by emphasizing the role of spacetime geometry in preserving and altering information, offering a direct way to detect interference with signals, potentially bridging quantum and classical regimes. However, experimental validation would require extremely high-resolution instrumentation and robust methods to distinguish such artifacts from natural spectral variations.

This principle can also be applied in a more traditional quantum encryption application. Quantum computing logic gates typically use the HOM dip as criteria turn on and off, so precise control of the arrival time of photons is crucial.[

10] This theory predicts that the spectral envelope of a photon can be shaped through deliberate perturbations along its duration of flight.

4.6. Testing the relationship between time and frequency domains

In this theory, the relationship between time and frequency space is leveraged as a foundation for quantum dynamics. For instance, changes to the spectrum of laser light in an appropriate medium can generate a chain of laser pulses (mode-locked lasers) or an organized series of higher frequency modes (high harmonic generation). Given that a finite spectrum corresponds to a non-instantaneous temporal interval, how do such changes in the spectrum translate to changes in the physical domain? Is this relationship causal? Is it dual in the sense that the temporal form is a direct and instantaneous manifestation of the spectral changes? Do laser pulse chains arise or disintegrate as a group or individually?

The emergence of standing wave patterns in a medium is generally thought of as a causal process, due to the interference of waves being generated in the current moment with waves originating in the past that have reflected off the boundaries of the medium. In the theory presented here, one could more carefully investigate the detailed process of formation or disintegration of a chain of pulses, or the lasing process within a laser when it is first turned on or turned off.

5. Ontological Concerns

The irreducible nature of spacetime intervals does not imply fixed, discrete chunks but rather any interval of arbitrary size between measurements. Theoretically, such intervals can range from atomic scales to interstellar distances.

This irreducibility avoids the need to abstract an additional `meta-time’ parameter in order to accommodate the Many Worlds or Multiverse perspective. Evolution through time is described by a spectrum in -space, which does not evolve or depend on a time parameter. Between measurements, time is represented by an unmeasurable unitary parameter (distinct from the measurable coordinates which describe discrete interactions). The role of meta-time is played by the ordering of branching events, not by any continuous variable.

A multi-block universe is essential to this description, as it allows multiple trajectories to evolve simultaneously while forgot what the fuck is going onalso accommodating free choices by an outside experimenter. The difference between a whole trajectory (e.g., from Sun to Earth) and a broken trajectory (e.g., from Sun to satellite to Earth) is described by distinct phase maps in the multi-block universe.

The multi-block universe is informational rather than directly measurable. Each block represents alternate possibilities rather than alternate realities. Evolution within a block is unitary and deterministic, maintaining coherence within the segment. The duration of a block is defined by branching events, giving each block a dual nature: it is both independent and part of a larger whole.

5.1. Predeterminism

The notion of predeterminism naturally arises when temporal segments are described by their Spectra. If time cannot continuously evolve and the spectral signature encodes the entire interval from beginning to end, it implies that all possible outcomes for a system must be accessible until a measurement defines the observed path.

In this view, predeterminism is finite, suggesting that sequential paths of finite duration are encoded as possibilities, with the observer playing a role in determining which path becomes realized.

The spectral signature of a photon is invariant and represents the entire journey, including the start and endpoints. Thus the spectral signature most determine not just one but all possible evolutions.

In this model, we live in a Multiverse which doesn’t evolve. Rather it gets progressively smaller as it trims off branches.

5.2. The Role of Phase

The central aim of this analysis is to highlight the importance of the frequency domain spectrum—and particularly phase information—in temporal translation for both quantum wavefunction propagation (QWP) and scalar diffraction theory (SDT). While phase information is often ignored in signal processing (e.g., due to the limitations of photographic film or the focus on magnitude spectra), it plays a critical role in interference effects and system dynamics.

In Fourier analysis, phase information in k-space encodes spatial information in x-space. This insight motivates a D formulation of quantum wavefunction propagation, where the same properties apply to space and time. For example, an auditory tone can be shifted in time by via the transformation , and similarly, a spatial feature in a digital image can be shifted by via .

Modeling quantum dynamics after scalar diffraction theory provides a framework for symmetry between space and time, where the phase structure governs evolution. This approach reinforces the view of spacetime as fundamentally spectral, with phase information central to understanding quantum interactions and coherence.

5.3. Quantum Evolution in Dimensions

It is common in formulations of dynamics to treat dynamical variables such as displacement, velocity or acceleration as dependent variables, parameterized by an unconstrained time parameter. Yet even in the non-relativistic quantum formalism, a more sophisticated notion of time exists, namely in the distinction between parameters and coordinate intervals. Parameters, such as x and , or t and , are unmeasurable dummy variables used in Fourier integrations to convert between dual domains. In contrast, coordinates and represent measurable intervals in space and time, while and correspond to distinct jumps in momentum states or energy levels. This distinction clarifies the static yet dynamically encoded nature of 3+1D distributions in -space proposed here.

For example, a Fourier transform integrates out explicit time dependency, leaving a static distribution that cannot evolve in time but encodes dynamical information through its phase structure. This is analogous to a hologram, where 2D interference patterns encode apparent 3D coordinates. In this framework, motion is represented as discrete updates in coordinate intervals during interactions, rather than continuous evolution, highlighting the encoded dynamical constraints within frequency space.

It was shown in

Section 2.3 that the propagator can be represented as a discrete forward and inverse Fourier transform. Therefore any propagation is done over finite, rather than infinitesimal distances and durations. Points in time or space in between the starting point and ending point of integration of the propagator are not individually defined. Distinguishing between parameters (of integration) which vary smoothly over the interval and the coordinates at the endpoints of the interval is a natural consequence of this approach. The latter are measurable and distinctly defined, whereas the former are not.

If we accept that the geometry of spacetime intervals and their spectra can be used to track dynamical interactions, and that expressions of the form Equation (7) (a propagator) can be applied to interactions in both space and time, we must conclude that intervals of space and time are discrete and irreducible. The resulting description is symmetric in these variables, providing a possible connection between the quantum formalism and special relativity.

6. Discussion

In this study it was shown that time intervals are encoded as a whole in the spectral fingerprint of a particle, e.g. photon. Emphasizing the similarity between quantum wave function propagation and scalar diffraction theory, it was shown that any subdivision or intermediate measurement along a temporal interval will result in spectral artifacts, making it evident that the whole interval and the partial interval are fundamentally different, and that they are to be considered as distinct, discreet wave function branches. As a corollary, it is predicted that photons of cosmic origin should retain a spectral fingerprint encoding their duration of travel, potentially providing a novel method for measuring astronomical distances.

Appendix A. Similarities between Scalar Diffraction Theory and Quantum Wavefunction Propagation

Scalar diffraction theory (SDT) describes how an optical wavefront in two spatial dimensions changes as it propagates in a third spatial dimension. It utilizes both x-space and k-space to do so.

In SDT, an optical wavefront is propagated by multiplying its k-space representation by an amplitude transfer function. More generally, any filter can be applied to a signal by convolution in x-space or multiplication in k-space.

Similarly, in quantum mechanics (QM) the propagation of a wavefunction (or quantum wavefunction propagation, QWP) is encapsulated in the propagator, also defined in k-space. In both instances, propagation of a signal in spacetime involves multiplication by a phase factor in k-space.

The starting point for scalar diffraction theory is the Huygens-Fresnel equation, describing the propagation and consequent image formation due to an incoming wavefront affected by an aperture that propagates to a screen. If

and

correspond to the horizontal and vertical directions on the aperture of the imaging device, an integral is performed over the entire aperture for each point

on the viewing screen. Labeling the original waveform

, the Huygens-Fresnel equation is[?]

When combined with Fresnel’s quadratic wavefront curvature approximation, the image on a screen under Fresnel diffraction is proportional to

where a quadratic constant phase factor of the form

has been pulled out of the integral and omitted for the sake of clarity.

Note that when light passes through an aperture in

space, the spatial parameters

and

describing the aperture become scaled frequency parameters in

k-space,

where

z is the distance to the screen, Equation (

A2) can be written

where

is the Fourier transform of the incoming wavefront, and the convolution kernel

is called the impulse response, which is the inverse Fourier transform of the amplitude transfer function.

References

- Marte, M.A.M.; Stenholm, S. Paraxial light and atom optics: The optical Schrödinger equation and beyond. Physical Review A 1997, 56, 2940–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson-Isaacs, S.E. Spacetime Paths as a Whole. Quantum reports 2021, 3, 13–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshinsky, M. Diffraction in Time. Phys. Rev. 1952, 88, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, F.; Schätzel, M.G.; Walther, H.; Baltuška, A.; Goulielmakis, E.; Krausz, F.; Milošević, D.B.; Bauer, D.; Becker, W.; Paulus, G.G. Attosecond Double-Slit Experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 040401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, S.J.U.; Polino, E.; Ghafari, F.; Joch, D.J.; Villegas-Aguilar, L.; Shalm, L.K.; Verma, V.B.; Huber, M.; Tischler, N. A robust approach for time-bin encoded photonic quantum information protocols. npj Quantum Information 2019, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzallas, P.; Charalambidis, D.; Papadogiannis, N.A.; Witte, K.; Tsakiris, G.D. Direct observation of attosecond light bunching. Nature 2003, 426, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, P.; DiMauro, L.F. The physics of attosecond light pulses. Reports on Progress in Physics 2004, 67, 813–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, J.; Auguste, T.; Muller, H.G.; Salières, P.; Agostini, P.; DiMauro, L.F. Scaling of wave-packet dynamics in an intense midinfrared field. Physical Review Letters 2007, 98, 013901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, J.J.M.; Lasa-Alonso, J.; Molezuelas-Ferreras, M.; Tischler, N.; Molina-Terriza, G. Bandwidth control of the biphoton wavefunction exploiting spatio-temporal correlations. Optica 2015, 2, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Tomita, A.; Okamoto, A.; Ogawa, K. Reduction of the two-photon temporal distinguishability for measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution. Opt. Lett. 2024, 49, 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franson, J.D.; Jacobs, B.C.; Pittman, T.B. Quantum computing using single photons and the Zeno effect. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 70, 062302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, M.; Röhlicke, T.; Kulisch, S.; Rohilla, S.; Krämer, B.; Hocke, A.C. Photon arrival time tagging with many channels, sub-nanosecond deadtime, very high throughput, and fiber optic remote synchronization. Review of Scientific Instruments 2020, 91, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahms, C.; Travers, J.C. HISOL: High-energy soliton dynamics enable ultrafast far-ultraviolet laser sources. APL Photonics 2024, 9, 050901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson-Isaacs, S. Eliminating the Second-Order Time Dependence from the Time Dependent Schrödinger Equation Using Recursive Fourier Transforms. Quantum Reports 2024, 6, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, T.; Baumann, E. 20 years of developments in optical frequency comb technology and applications. Communications Physics 2019, 2, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, J.; Voss, P.; Sharping, J.; Kumar, P. All-fiber photon-pair source for quantum communications: Improved generation of correlated photons. Optics Express 2004, 12, 3737–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 |

Here, rect(x) is the rectangular function, defined as 1 for and 0 otherwise. Subtracting the fraction 1/2 from its argument moves its left edge to the origin, for convenience. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).