1. Introduction

Climate change is one of the most pressing challenges of the 21st century, impacting environmental, social, and economic systems globally. Although human activity is shown to be the primary driver of climate change, significant uncertainties and controversies remain regarding how to address it effectively. These dilemmas need to be approached within the framework of a strong theory that embeds uncertainty, irreversibility, and the value of information into the policy-making process. This study helps provide a roadmap to strengthen climate governance and resilience by proposing a dynamic decision-making framework for renewable energy investments addressing these uncertainties.

Scientists have meticulously documented the rise in global temperatures and the melting of polar ice caps. (Barua et al., 2022), and the acidification of oceans (Findlay & Turley, 2021). They have identified the fingerprints of human activities on these changes, providing irrefutable evidence of our role in shaping the climate. Additionally, research has illuminated the interconnectedness of various climate phenomena, emphasizing the need for a holistic approach that integrates climatology, ecology, and socio-economic research to comprehend the complexities at play (Räsänen et al., 2016). However, climate change is not a distant, abstract concept confined to scientific journals. Its impacts are palpable and accelerating, implying urgent mitigation and adaptation action. Among the most critical methods to combat climate change is the transition to renewable energy investments, which would reduce dependency on fossil fuels and mitigate environmental damage.

Investments in renewable energy are one of the most crucial mechanisms for addressing climate change. However, these investments have considerable uncertainties, including cost variability, technological advancement, public acceptance, and environmental outcomes. This work contributes to renewable energy policy modeling by developing a dynamic decision-making framework that incorporates these uncertainties. The irreversibility of these investments and the changing nature of climate science demonstrate the need for decision-making to account for the value of information. Using the principles of irreversibility and the value of information, the study seeks to extract a valuable message for policymakers.

The manuscript rigorously explores the various dimensions of climate change, providing an extensive theoretical context on carbon development and prospective climate impact situations. This comprehensive examination aids in a rationalized vision of concerns and a better understanding of the issue. It also presents a comprehensive examination of climate models, illuminating the evolution and attendant reliability controversies over these tools and generating meaningful considerations on where they can go wrong or be modified so that model outputs more faithfully reflect real-world nature. In this regard, we present a rigorous exploration of the theory behind climate policy by reviewing principles from decision theory, charted by the early work of Von Neumann and Morgenstern, and their later developments by Savage. The paper conceptualizes a dynamic two-period decision-making process that directly informs renewable energy policy by examining elements like subjective probabilities, irreversibility, and quasi-option value. This framework allows policymakers a systematic guide to minimize investment risks and adjust their strategies with new information.

1.1. Potential Climate Change

The increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is mainly due to human activities other than natural processes; data about different climatic parameters illustrates a clear tendency for climate shift (IPCC, 2023). Current data shows a temperature rise of around 0.5 °C from 2000 to 2023, showing that this warming trend is worsening with time and heading towards catastrophic global conditions such as ocean acidification, leading to an unlivable planet for many species, including humans. The most significant jumps on record have been in the last several decades, and 2023 was among the warmest years ever. This is even more evidence of the effect of climate change, as the extent of snow cover has fallen by 10pc since records began back in 1960. At the same time, sea levels are increasing worldwide, with around an 80 mm rise noticed in the international standard ocean level from 2000 to 2023. This is mainly due to increasing global temperatures, which raise ocean volume by a change in the density of seawater caused when temperature and salinity variations come into play. Warming has also produced more de-glaciation, sending additional water to the oceans.

We have also witnessed other climatic changes: a rise in precipitation of 0.5% to 1% per decade during the last century, nearly all for snow and rain patterns across North America, North of Mexico, much of Russian Europe into Asia. On the other hand, there have been reductions in precipitation levels over parts of the Mediterranean regions (including southern Europe and western Asia), Southern Africa, and South Asia. The frequency and severity of extreme weather events, such as droughts and heat waves, have also escalated.

Recent data reveals that global climate change is part of temperature changes, sea level rises, and snow cover extent. Recent changes are summarized for the following:

In

Table 1, changes have been observed in (a) global average temperature, (b) global mean sea level (modeled data are in blue, and observed data are in red), and (c) snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere for the months of March-April. All changes are relative to averages for the base period 2000–2023. In Scenario A, sea levels are predicted to increase by 1.2 meters by 2100. This data underscores the necessity of reducing emissions to mitigate long-term risks.

1.2. Interpretation of the Relationship Between the Increase in GHGs of Anthropogenic Origin and Climate Change

Most greenhouse gases are identified. Their role in climate regulation is not controversial. However, the relationship between climate and the increase in the concentration of these gases is complex and has generated much controversy for a long time. The comparison of observations of the evolution of the gas content on the one hand and that of the climate on the other hand (see the two previous paragraphs) tends to confirm not only a causal relationship between the increase in gases greenhouse gases and climate change but also that human activities are the cause of the increase in these gases. Today, specialists authenticate the increase in greenhouse gases of anthropogenic origin as the primary source of climate change in addition to natural variability. They estimate that CO2, through its contribution of 65% to the total increase in the greenhouse effect, is known to be the leading cause of the temperature rise. The effect of CH4 is not negligible either; its increase contributes 26% to the total increase in the greenhouse effect. With a more significant effect, water vapor is responsible for a greenhouse effect, increasing the temperature of our ambient environment by more than 30%. To establish more detailed estimates of all possible climate system responses to greenhouse gas increases, climatologists use meteorological climate simulators to conduct numerical simulations of the combined or independent effects of natural and anthropogenic forcing. “Climate Models”.

1.3. Climate Models: Increase in Greenhouse Gases at the Origin of Climate Change

Climate models are essential for interpreting observations and interactions between climate components and estimating future developments. These numerical models integrate a series of physical interpretations of climatic components and their various essential interactions to reconstruct major climatic trends similar to actual observations. These models specify solar luminosity, atmospheric composition, and other radiative forcing agents. They make it possible to simulate all the possible responses of the atmosphere, the ocean, the land surface, and the sea ice to the different internal, natural, and anthropogenic variabilities. These models' inputs include natural variables (such as changes in solar radiation) and anthropogenic variables (such as greenhouse gas emissions).

The radiative forcing concept measures the influence of increases in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Thus, the increase in GHGs in the atmosphere produces a positive radiative forcing due to increased absorption and emission of infrared radiation. This effect is called the intensification of the greenhouse effect. Without any other interference, this phenomenon would lead to an increase in temperature.

These gases' contribution to the temperature increase is not made with the same intensity. It depends on the increase in their concentrations in the atmospheric reservoir, the relative properties of their molecules, their capacities (or radiative forcing) to absorb infrared radiation, and the time they spend in the atmosphere after emission. Nordhaus (1991) carried out a study on the contribution of GHGs to global warming. This is the instantaneous warming potential (i.e., the relative impact on warming per unit of concentration) and a total of the main GHGs around the middle of 1980. The result shows the dominance of the impact of CO2 in global warming compared to other GHGs.

In addition, the climate system is complex, and other phenomena superimpose the increase in the concentration of greenhouse gases, such as feedback, caused in particular by water vapor, the melting of the ice cap, and the behavior clouds. Indeed, if the radiative forcing corresponding to a possible doubling of the CO2 concentration were 4 Wm -2, the temperature would increase by 1.2 °C (with a confidence margin of 10%) without any other change. It would increase by 1.6 in the presence of feedback due to water vapor. In addition, the increase in temperature would cause the snow cover of continents or seas to change, which would lead to surface alteration, and becoming darker, the earth would absorb more heat, which would increase the greenhouse effect. If these feedbacks are added to those of water vapor, the temperature would increase by 2.5 °C. The total effect of these phenomena is estimated to increase the temperature by 1.5 to 4.5 °C.

We thus show that the increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere tends to warm the globe's surface. This warming would cause climate changes for all climate parameters because it triggers a modification of atmospheric circulations and other subsystems of the climate system.

1.4. Controversies Over Climate Models

The results of the climate models are discussed. Like most numerical models, climate model simulations are considered not robust even by those who created them. On the one hand, they depend on the level of understanding of the physical, geophysical, chemical, and biological phenomena and processes responsible for the natural variability of the climate system, as well as sudden future changes such as the variability of solar activity or volcanic eruptions. However, these aspects are complex, uncertain, unstable, and present great difficulty in their modeling. Elucidating these uncertainties would require a good understanding of the phenomena present within the atmospheric reservoir as well as the different components of the climate system. Nevertheless, experts recognize that climate models omit specific components, such as the effects of clouds and their interactions with radiation and aerosols, the exclusion of specific regulatory effects from the balance of global balances, or the difficulties of estimating the absorption capacities of the oceans.

On the other hand, they are limited by the extent of their calculations and the difficulty of interpreting their results. The simulations present fundamental circulation on a planetary scale, seasonal variability, and temperature structures with qualitative validity, but certain contradictions remain.

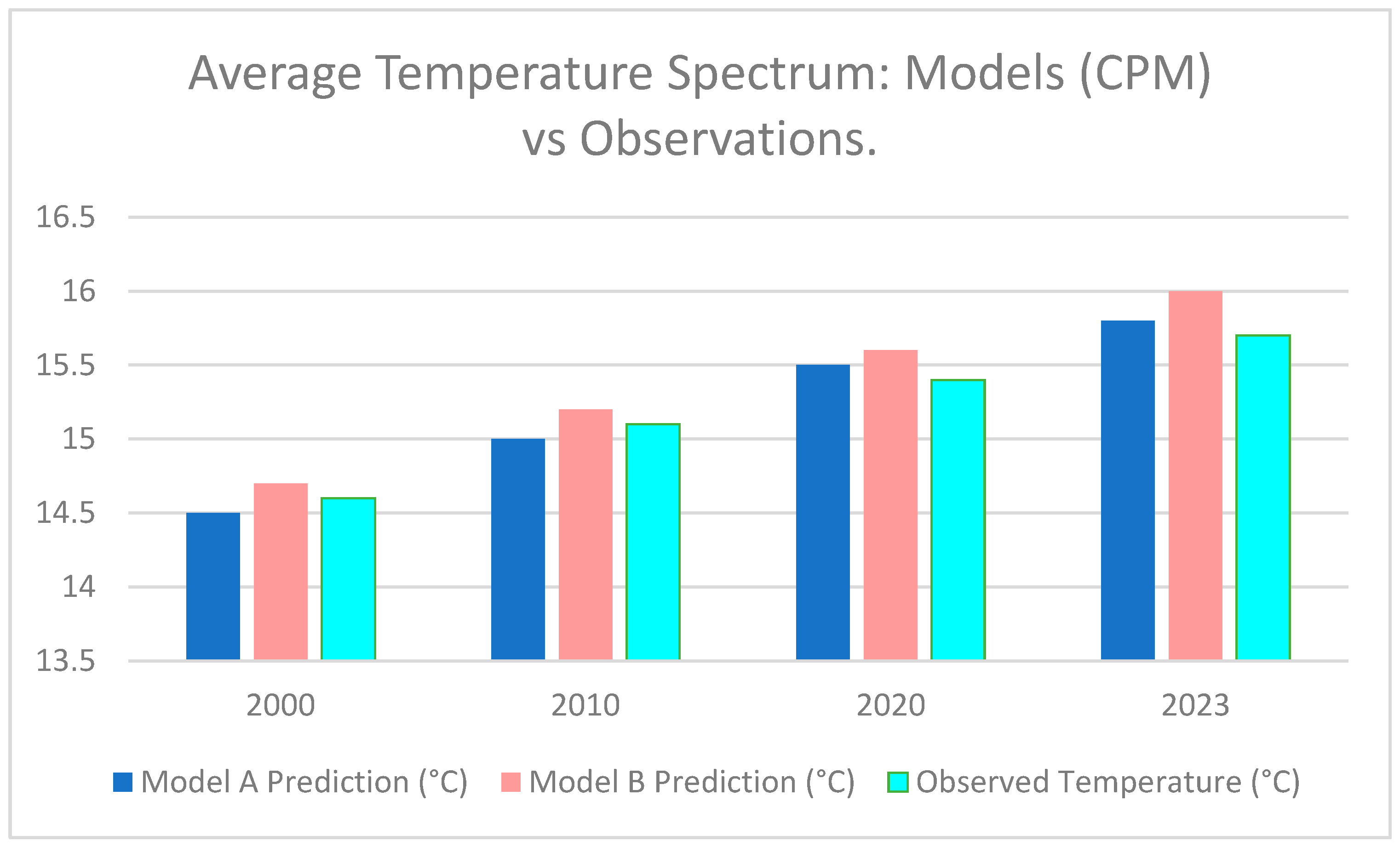

Although the models still require adjustments, they allow a stable balance between the different components over very long periods (of the order of a millennium) with free exchange of heat and water. They expose the dominant aspects of intrinsic variability in a manner comparable to actual observations (

Figure 1). They show that the responses of average global temperature to forcing correspond approximately to measurements recorded throughout the last century.

Scientists continue to develop weather simulators or climate models by studying, among other things, the many complexities that generate inevitable uncertainties. Current models include more parameters and make it possible to develop increasingly reliable simulations. Confidence in these models is growing but inherent uncertainties remain.

1.5. Methodology for Developing Future Climate Data

In order to develop climate projections, the IPCC relies on projection scenarios and climate models, general circulation models (GCMs) in particular, which we have explained above. Models make it possible to generate future climate data using projection scenarios.

1.5.1. Projection Scenarios

The difficulty of predicting future greenhouse gas emissions (climate model inputs) is behind the development of these scenarios. As the IPCC underlined in its first report in 1990, these emissions that induce climate change result from very complex dynamic systems and the conjunction of several driving forces, such as demographic, socio-economic, and technological development, which influence greenhouse gas emissions. To remedy this difficulty, we use the SRES scenarios developed by the IPCC and published in the “Special Reports on Emission Scenarios” (IPCC, 2000). These scenarios replace those developed in 1990 and 1992 (IS92) following an assessment made by the IPCC in 1995 showing these failures and suggesting the need to integrate the modifications acquired into understanding the driving forces of emissions. The IPCC defines SRES scenarios as “alternative images of how the future will unfold that are an appropriate tool for analyzing how driving forces may influence future emissions and for assessing associated uncertainties” (IPCC, 2000). These scenarios are based on plausible narrative hypotheses describing the relationships between different forces, their developments, and the decision-making scale. The hypotheses are broken down into four lines: A1, A2, B1, and B2, which explore the evolution of the world population, environmental protection, economic development and of energy technologies and integration, globalization of the economy; group A1 includes three references scenarios A1F, A1B, A1T which are broken down according to the degree of use of fossil fuels. Since the hypotheses describe facts that are unpredictable and difficult to verify over a long period, the IPCC uses a broad and diverse range of scenarios reflecting different trajectories in order to take into account the high degree of uncertainty linked to forces and GHG emissions. Indeed, several scenarios (40 SRES scenarios) were developed from each lineage using models representative of the integrated assessment method. Each resulting scenario represents a quantitative interpretation of one of the four lineages. The IPCC uses SRES scenarios to determine GHG emissions levels that parameterize carbon cycle models.

1.5.2. Climate Models

General circulation models (GCMs) make it possible to generate future climate data at a global level. However, since climate impacts are generally felt locally, future climate data should be available at a regional level. The regional climate is defined as being a random process constrained, at the same time, to circulations on global and local scales both at the atmospheric and oceanic levels and to conditions specific to the regions.

The problem is that climate models have a low-resolution scale of around 200 to 300 km. To study climate change at a regional level, climate simulations should be carried out at a high-resolution scale, generally between 20 and 50 km.

Several approaches are used to regionalize climate simulations, such as dynamic downscaling (making it possible to obtain, for example, regional climate models – RCMs), which consists of using physical-dynamic models to explicitly resolve the physics and dynamics of the climate system on a regional scale, and the statistical downscaling method which establishes, based on observations, a statistical relationship between fine-scale and large-scale variables (predictors).

In the IPCC work, the regional climate change projections presented are evaluated based on available information regarding the history of recent climate change, understanding of the processes governing regional responses, and data available from GCGAM simulations and disaggregating these data using techniques that highlight regional details.

1.5.3. The Inherent Uncertainties

The process of developing future climate data is fraught with uncertainty. Indeed, from the moment we seek to integrate the values of the concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere into climate models, an arbitrary choice of a projection scenario must be made. Thus, the accuracy of the chosen emissions trajectory would depend on the realization of the scenario. However, this is linked to society's unpredictable and complex behavior.

Considering the simulation stage requires estimating the values of expected future GHG emissions and modeling interactions between atmospheric and oceanic circulations. However, these are subject to several uncertainties due to the lack of knowledge on the chaotic components of the climate and terrestrial system (such as clouds) and their interactions. Indeed, the models are based on strong hypotheses on physical phenomena and significant simplifications of the processes governing the climate. The transition to regionalizing data predicted by climate models is an even more delicate process. This appears from the very choice of the regionalization methodology. In addition, this step requires correctly modeling the topography of the regions concerned and precise knowledge of the regional climate.

1.6. Determination and Anticipation of Issues: Controversies Over Methods

As confirmed by IPCC experts, determining and anticipating climate change's impacts on natural and human systems requires using several physical, biological, and social disciplines and, subsequently, various methods and tools. Although a wide range of tools and methods have been developed, certain questions remain at the center of scientists' concerns to this day from the stage of detection and attribution of impacts to climate change.

Climate change and the effects observed on natural and human systems are linked using detection and attribution methods. Extending the methods used on changes observed in climate systems to changes observed in physical, biological, and human systems is more complex. The IPCC recognizes that the responses of these systems to climate change may be so dampened or completely confounded with other factors that it would be impossible to detect them. To face these difficulties, the IPCC experts start from the obvious: “(…) the effects of climate change are very transparent in systems where human manipulations are ephemeral” to suggest that: “systems Who _ contain an excellent coherent {basic process} of the effects of climate and weather events, and where human intervention is minimal, can serve as indicators of the more general effects of climate change in the systems and sectors where they are easily studied.” (Mitchell et al., 2001).

The choice of such indicators is complicated. Most existing studies considered by the IPCC reports relating to estimates of possible damages tend to focus on the more firmly established warming consequences, such as extreme temperatures on health, agricultural productivity quality, and water availability. Studies of the relationship between warming and observed changes in natural and human systems use climate models or spatial analysis. The first consists of comparing the observed changes to the changes resulting from three modeling stages by taking into account natural forcing factors and anthropogenic forcing factors separately and then combining them. The second establishes a comparison between data series consistent with warming and those not; collected in cells of five degrees of latitude and longitude around the globe showing significant warming and/or cooling.

Thus, the determination of the consequences of climate change on natural and human systems is marked by uncertainty from the moment we decide on the indicator we will designate. Indeed, the choice of temperature as an indicator is widely discussed in the literature. Nordhaus (1993), for example, emphasizes that the global average temperature, the statistic on which these approaches are based, is of little economic interest. Per him, one cannot analyze the impact of varying warming rates on agriculture without knowing about regional precipitation and soil moisture changes. He, therefore, suggests using variables that accompany or are the result of changes in temperature, such as precipitation, water levels, extreme droughts, or frosts, and which will, according to him, lead to socio-economic impacts.

Similarly, anticipating the impacts of climate change on natural and human systems includes methodological gaps that the IPCC often raises in its assessment reports regarding data scales, validation, and integration of adaptation and human dimensions of climate change. This is although a wide range of methods and tools are available and are undergoing continuous improvement with greater emphasis on the use of models based on the use of transient climate change scenarios, the refinement of socio-economic references basic economics, as well as the spatial and temporal scales of assessments and the integration of adaptation, which the IPCC describes in its latest report. However, these models have been tested on all continents at sectoral, regional, and global scales. The IPCC credits their results and considers them in its assessment reports.

1.7. Potential Issues to Take Action

1.7.1. Skepticism About IPCC Conclusions

The conclusions of the IPCC are not often unanimous. There are scientists {Mike Hulme (December 2009), Vincent Courtillot (October 2009), Marcel Leroux, etc.} who especially contest the fact that the greenhouse effect caused by man is responsible for global warming. The media sometimes supports these protests, which tend to emphasize controversial aspects. We like, for example, to present a duality where we emphasize the disagreements between two significant ideologies while sometimes forgetting to compare their scale, support, and real credibility. Yet the scientific basis of the problem is much less controversial. As seen previously, the available scientific data justifies current concerns about climate change and its potential effects. The international community marginalizes these controversies. Almost all governments have joined the scientific consensus established in the fourth assessment meeting of the International Group on the importance of human responsibility over natural factors in global warming through greenhouse gas emissions. The Stern Report on the economics of climate change confirms the conclusions of the IPCC.

Overall, scientists and the international community have confidence in the scientific validity of the reasons given for concern about climate change and the potential for feared risks. They recognize that uncertainties mainly lie in the detailed effects of climate change, primarily the magnitude and rate of change. This is also why they recommended the immediate adoption of preventive measures to slow the rate of climate change. As early as the 1995 IPCC report, scientists made a similar assertion: "Although we cannot accurately quantify the nature and extent of climate change and its impacts, it appears obvious that changes and impacts have already begun and will continue. "We must act now to limit the damage while considering a range of uncertainty scientists expect to reduce over the coming years."

1.7.2. Problem of Climate Change Through the Lens of the International Community

The problem was officially recognized, and the international community laid the foundations for coordinated international action against the greenhouse effect by creating the Climate Convention. Although this international response may not seem tangible since it does not provide for any penalties against countries that do not achieve the common objective set, it constitutes a significant turning point in international awareness of the risks associated with climate change.

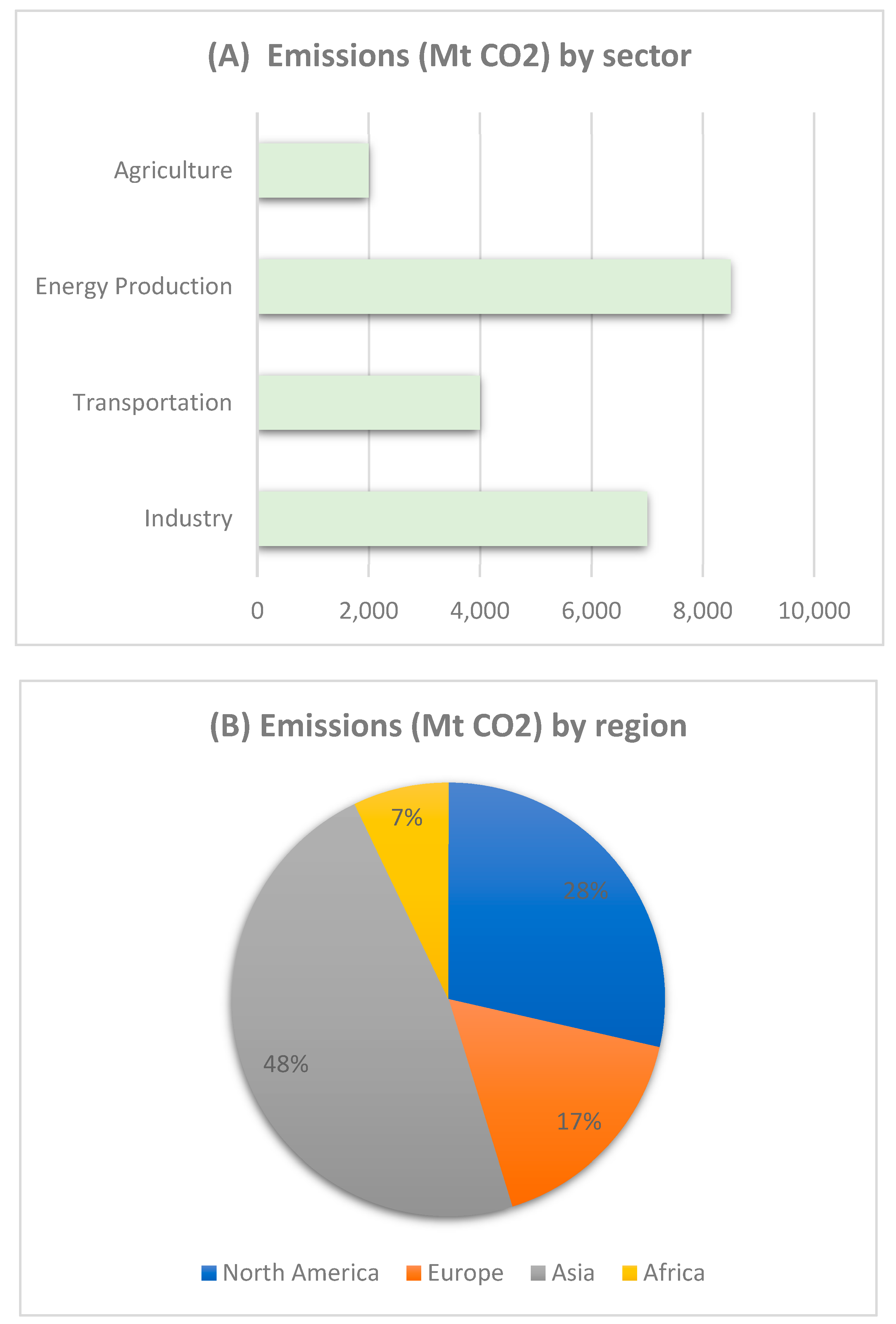

Since then, the process of diplomatic negotiations has continued around its ultimate objective, "the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions," in order to make it a reality, punctuated by the annual Conferences of the Parties, also called United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP), on the one hand, and the scientific reports of the IPCC, on the other. In December 1997, during the third conference of the parties (COP3) in Kyoto, we created the Kyoto Protocol. This requires the industrialized countries grouped in Annex B of the Protocol (38 industrialized countries: United States, Canada, Japan, EU countries, and countries of the former communist bloc) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Greenhouse gas emissions by 5.2% on average by 2012, compared to the 1990 level. Recognizing their responsibility for the accumulation of GHGs in the atmosphere by ratifying the Convention, most of these countries have committed to the protocol. However, a group of countries led by the United States, recognized as the state emitting the most GHGs (see Figure 4), demanded the creation of an international market for tradable emissions quotas. Such a market would allow each industrialized country to satisfy its needs not by limiting its emissions but by purchasing a surplus of rights to emit abroad.

Figure 3.

Contribution of Regions and Sectors to CO2 Emissions by 2020 (A) Sectoral Contribution to CO2 Emission by 2020. (B) Regional Contribution to CO2 Emission by 2020.

Figure 3.

Contribution of Regions and Sectors to CO2 Emissions by 2020 (A) Sectoral Contribution to CO2 Emission by 2020. (B) Regional Contribution to CO2 Emission by 2020.

Implementing this protocol proved more difficult than creating it. The allocation of emission permits is confounded by various inequalities in past and current emissions, population growth, technical capacity, and vulnerability to impacts. Furthermore, in March 2001, the President of the United States announced that he would not submit the Kyoto Protocol for ratification by the Senate. His objections to the Kyoto Protocol revolved around the non-participation of developing countries in reducing emissions and the level of reduction commitment made by the administration in Kyoto. Furthermore, the reduction objective has become insignificant. The protocol obtained after a decade of negotiations in which the international community invested substantial resources risked failure.

On 16 February 2005, the Kyoto Protocol finally took effect after being ratified by numerous countries during the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP 11) (UNFCCC, 2023). This meeting in Montreal in 2005 resulted in a constructive outcome that opened the door for new momentum in climate talks. (Velders et al., 2007). This led to key technical decisions and an agreement to hold separate talks to discuss the future of the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol. (Wittneben et al., 2006). Thus, industrialized countries, except for the United States and Australia, which account for more than a third of the industrialized world's greenhouse gases but have not ratified the protocol, are required to reduce their emissions of CO2 and five other gases warming the atmosphere. The 107 developing countries that have ratified the protocol will have simple polluting emissions inventory obligations. Thus, it was the first step towards reducing GHG emissions, which was undoubtedly modest due to the non-participation of the United States and Australia but obtained after long and difficult negotiations. Australia ratified the protocol on 12 December 2007, following Labor's coming to power.

The climate convention marks the symbolic starting point for a possible change in the preferences and behavior of economic agents. However, the progress of the negotiations has not reached a breakthrough despite the pessimistic data on the future evolution of the climate and related issues (IPCC, 2007).

A more recent decisive COP for climate change took place in Paris in December 2015 (Lane, 2017, 2018; Pan, 2022; Rhodes, 2016)The conference resulted in the Paris Agreement, which is highly commended by all parties involved. The agreement is significant because it ensures that the global climate architecture will not be demolished or replaced with a completely new framework. It is considered a major diplomatic success and has regenerated faith in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as a forum for multilateral action. (Christoff, 2016). The conference also sparked discussions and debates among key players, such as the USA, EU, China, and India, regarding the practical arguments and values underlying global climate change policy-making. (Lewiński & Mohammed, 2019) However, there are concerns about the agreement's implementation and the lack of binding emission reduction targets. Global coordination is seen as crucial in achieving the goals of the COP21 project and managing the rapid decarbonization needed to avoid climate chaos. (Lane, 2018; Wang et al., 2020).

1.7.3. Difficulties of Monetary Evaluation of the Consequences

A monetary evaluation of these impacts can be beneficial, especially for comparing the costs of preventing climate change to the expected benefits. In fact, with the evolution of recognition of the phenomenon and the multitude of projects proposed, action is confronted with the conflicts of the different actors involved (public authorities, citizens, industrialists, and experts) in the decision. Such projects involve huge investments. Choosing one project among others would require evaluating the costs and benefits of all projects. Although assessments of expenses may not be controversial, those of benefits that relate to conditions in the distant future would be controversial. On the one hand, costs can be defined as opportunity costs (associated with restricting industrial or commercial activities, for example). At the same time, benefits are described, including their effects on improvements in the well-being of individuals or the impacts of avoided climate change.

Therefore, a monetary assessment of the damages linked to climate change would be necessary. Damage assessment techniques are numerous and varied in the literature. The evaluation of the economic impact of climate change, generally used, is equal to the amount by which the climate of a given period would affect the production or GDP of that period. The specific components included in these studies are, primarily, sea level rise, temperature changes related to heating and cooling demand, health consequences of extreme temperatures, and estimated changes in agricultural productivity and water quality and availability.

To assess the damage, we must separate market damage, which refers to impacts on activities or sectors producing market goods and services, from non-market damage, that is, impacts on the environment, biodiversity, and health…In the case of tradable goods, monetary valuation is generally based on market prices adjusted (to correct market distortions) using simple methods. A traditional impact estimation approach relies on the empirical production function to predict economic damage. This approach takes a specific production function and assesses impacts by varying one or more variables, such as temperature, precipitation, and carbon dioxide levels. On the other hand, valuing non-market goods in a common metric, usually monetary, is very difficult. Much literature on the issue reveals procedures that rely on individuals' willingness to pay for an environmental good or service. (Baker & Ruting, 2014). This approach can lead to bias since it asserts that damage does not have the same price depending on whether you are rich or poor. Indeed, the individual's willingness to pay depends on the income of the agent considered.

The evaluation of non-market damages raises the problem of evaluating the direct effects on the individual's well-being. Indeed, there is certainly an interaction between the climate and the individual's well-being. Maddison and Bigano (2003), for example, show that higher summer temperatures reduce the well-being of Italians. A monetary assessment of the impact of climate change on individual well-being would be instrumental in determining whether the benefits justified the costs of preventing climate change. Aggregating multiple damages into a single assessment, suitable for providing information about the magnitude of expected damage on an overall scale, could be particularly interesting to policymakers (IPCC, 2022). In most studies, effects are estimated and valued sector by sector and grouped to estimate all changes in social well-being, known as the “enumerative” approach (Cline, 1994; Fankhauser & Tol, 2005). The studies presented by the second IPCC report and its current references (Cline, 1992; Nordhaus, 1991, etc) predict that the potential damage will be between 1.5% and 2.5% of world GDP for a doubling atmospheric concentration. Although they serve as a reference, these figures are questionable. Indeed, the range of 1.5% to 2.5% of GDP does not include the risks of climatic surprises and non-linearity in the adaptations of societies to climate change. Finally, all the attempts at estimation made using the "enumerative" approach recognize that developing countries will be the main victims of climate change because their economies are more fragile and more dependent on natural environments. In contrast, certain countries could benefit from increased agricultural yields. A stream of recently developed research shows that these results are inconsistent. This research is based on the weaknesses of the “enumerative” method.

In this context, Fankhauser and Tol (2005), criticize this method, stating that it ignores “dynamic interactions” in their work. They explain that enumerative studies look at a single period and how the observed climate affects social well-being in that particular period. Thus, they ignore intertemporal effects and neglect to provide information on how climate change may affect production in the longer term. This work draws attention to some dynamic effects of climate change on economic growth and future production. The authors explore, in particular, the direction of the two variables, savings and capital accumulation, following climate change based on an integrated assessment model developed by Nordhaus (2004). They distinguish the following two dynamic effects:

- -

With a constant savings rate, lower production due to climate change will lead to a proportional reduction in investment, reducing future production (capital accumulation effect).

- -

If the saving rate is flexible, early agents can change their saving behavior to accommodate future impacts of climate change. This will also change growth prospects (savings effect).

All the simulations carried out in this paper suggest that:

- -

The capital accumulation effect and the savings effect are both negative. Faced with climate change, households increase current consumption rather than savings to compensate for future damage, which will affect the economic growth rate.

- -

Indirect effects are relatively more significant than minor direct effects; the indirect effects are thus relatively more significant for the most frequent growth mechanisms in the wealthiest countries. Thus, Enumerative studies underestimate the impacts of climate change, especially in the case of rich countries.

1.7.4. Irreversibility and Option Value in Renewable Energy Policy

In renewable energy investments, irreversibility plays a central role in decision-making. Like environmental management, irreversibility has a dual character regarding energy transitions.(Pindyck & Pindyck, 2000) On one hand, delaying investment in renewable energy can lead to irreversible ecological damage. For example, continued reliance on fossil fuels increases greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, contributing to long-lasting or permanent climate impacts, such as rising sea levels and biodiversity loss. These changes reduce the flexibility of future generations to mitigate or adapt to climate change, as the accumulated greenhouse gases (13–17% of which, according to the IPCC, remain irremediable) would be exceedingly difficult to remove by artificial methods. This ensures the need to take action now to minimize all risks, following the precautionary principle determined by the international community.

In contrast, investing in renewable energy infrastructure requires heavy up-front investment that, in most cases, cannot be recovered. For example, constructing a solar or wind farm involves up-front sunk costs if later evidence shows these have become economically unviable or technologically outdated. This uncertainty disincentivizes decision-making and data accumulation, particularly regarding technology, market dynamics, and regional energy requirements.(Tankov, 2023) However, such delays may be at odds with the precautionary principle, as the chance to avoid environmental harm is lost as time passes.

These two aspects of irreversibility—environmental and economic—are closely tied to the uncertainties inherent in renewable energy transitions. Uncertainty arises from the extent of future ecological damage caused by inaction and the potential benefits of investing in renewable energy. For example, uncertainty about the future costs of renewable energy technologies or their long-term efficiency can impact decision-making.

The concept of option value is particularly relevant in renewable energy policy. Preserving flexibility allows policymakers to defer decisions until new information becomes available, reducing the risks associated with irreversible commitments. As Arrow and Fisher (1974) note, “Maintaining a unique environmental asset in its present state allows us to change our minds later. Changing it irreversibly does not.” Renewable energy could entail field-testing smaller projects or focusing on adaptive investments that allow for more careful birds-eye tweaks, depending on future conditions.

The quasi-option value, which stresses the value of sequential decision-making under uncertainty, is even more applicable. As an illustration, delaying complete investment in a specific renewable technology until more research is conducted to verify that it is a reliable option will allow generations in the future to turn to alternative and possibly more efficient solutions. This is analogous to the loss of possible opportunities resulting from a missing (Henry, 1974). These quasi-option values favor delay in renewable energy, but it is not delaying alone; it is balanced with proactiveness to ensure the energy switchover can make economic sense and benefit the environment.

In short, investments in renewable energy technologies should be characterized by a commitment to acting urgently to avoid irreversible environmental damage and a long-term investment design that maintains the option value of successfully reacting to economic uncertainties. The balance between taking action now and preserving options for the future is delicate. Still, decision-makers can avoid common pitfalls by embedding these principles into the renewable-energy policy process.

1.7.5. Obstacles in Transitioning to Renewables

While necessary for achieving climate change mitigation and sustainable development, the transition towards renewable energy encounters multiple key barriers. These hurdles can be classified as financial, technological, and socio-political.

Financial Barriers can rise because of High Initial Capital Expenditure. Renewable energy projects, including wind farms, solar arrays, and geothermal plants, entail large initial capital expenditures. Often inaccessible in poorer areas, these costs and financing discourage many stakeholders. (Emetere et al., 2022) Also, there is a lack of access to funding. Given the world's perception of the risk of investing, it is challenging for developing countries to find low-cost financing for renewable energy. (Emetere et al., 2022) Moreover, few financial institutions are eager to offer loans or investments for this purpose, leading to many renewable energy projects stalling due to a lack of funds. (Butu et al., 2021) On the other hand, due to the volatility of fossil fuels, investments in renewable energy remain uncompetitive in the short run, even when they benefit in the long run. This funding gap stifles the emergence of renewable energy projects and continues dependence on fossil fuels, hindering the transition to a more sustainable energy future. (Zhang et al., 2020) Furthermore, much of the world still subsidizes fossil fuel industries, which makes renewable energy technologies a competitive disadvantage. (Qiang & Yuanpan, 2015) Governments should realize that the ground needs to be even with subsidies and investment incentives in opposite directions; this is where policy reform is urgently needed. Models that bridge the gap between policy - utilizing sunshine and wind- need to be harmonized with the benefits and costs of utility suppliers and green energy producers. (Steinhilber, 2013)

Moreover, the transition to renewable energies faces technological barriers. Technologies like solar and wind are subject to variations in energy production, presenting challenges for inclusion in established energy grids. (Notton et al., 2018) Also, technologies for energy storage, essential to mitigating intermittency's impact, are still very costly and rarely deployed (Swain & Shyamaprasad, 2022) The existing grid infrastructure cannot effectively transmit and distribute renewable energy, particularly in rural or underdeveloped areas. (Sarma et al., 2017) Besides, Lack of R&D (Research and Development) funding slows technological progress that could enhance efficiency and lower costs. (Park & Shin, 2018)

Additionally, Socio-Political Barriers challenge investing in renewable energy. First, the absence of durable frameworks for renewable energy policy dissuades investment. (Alonso-Travesset et al., 2023) Second, local communities resist large, primarily industrial projects, often due to concerns about land use, aesthetics, and ecological impacts. (He et al., 2018) Additionally, dependence on rare earth elements and other critical raw materials for renewable energy technologies can create vulnerabilities in the supply chain and geopolitical conflicts.(Sweidan, 2021) Furthermore, uneven political support for renewable energy projects undermines progress, especially in areas with significant fossil fuel-based industries.

1.8. Dynamic Decision-Making Framework for Investments in Renewable Energy

Based on the discussion in this paper, this is a suggested dynamic decision-making framework. The structure will consider probabilistic scenarios, irreversibility, and option value in examining uncertainties and controversies. The framework seeks to capture renewable energy investments under uncertainty subject to economic, environmental, and policy constraints. It combines the principles of irreversibility, quasi-option value, and adaptive decision-making to guide resilient policymaking.

1.8.1. Theoretical background

Decision criteria

The usefulness of Von Neumann and Morgenstern

It is now indisputable that the decision model of the expected utility of Von Neumann and Morgenstern (VNM) is a reference in all areas of economics. Expected utility was the first classical theory that integrates all decision elements in an uncertain environment to allow a decision on the most advantageous action. The VNM model considers the object of analysis and decides the probability distributions on a possible set of results. To establish this decision criterion, VNM proposes a priori three axioms. The first is the ability of the decision maker to give a complete and transitive order of preference to all possible consequences of the chosen actions. The second is that of independence: the two acts do not have the same consequences. The third is continuity: the order of preferences is continuous; this axiom ensures that sufficiently small perturbations of the probability distributions do not modify their ranking. Under these conditions, the decision-maker must be able to associate a utility u(c) with each consequence and an expected utility with each action:

The choice between the two decisions comes down to comparing their expected utilities. Classically, the selection will be made in favor of the greatest possible expected utility.

Savage's Contribution

In the context of utility function maximization, VNM theory models, as we have just seen, have uncertain prospects in the form of probability distributions over a given set of consequences. The probabilities are, therefore, given exogenously: these probabilities are objective. By analogy with the distinction made by Knight between risk and uncertainty, Von Neumann and Morgenstern consider the situation where the individual makes his choices in a risky universe. However, in our problem case, we assumed that risk and uncertainty are synonymous, and the decision-maker makes choices based on subjective probabilities. Furthermore, the decision-maker does not know the probabilities of occurrence of the different possible states of nature, and his choice depends on his subjective evaluation of these probabilities.

Several decision criteria in uncertain universes in the literature are based on statistical decision theory. However, these approaches have quickly shown their limits – especially when we seek to apply them systematically to collective choices.

We will focus on formalizing the uncertainty situation established by Savage (1954). We are in the same frame of reference as maximizing expected utility. Analogously to the decision under risk, there exists a set of consequences C and a set of states of nature S.

We assume that the states of S are:

- -

Mutually exclusive: the realization of one state of nature automatically prevents the realization of another

- -

Exhaustive: the set of states of the world contains absolutely all external events likely to occur.

From C and S, the decision maker constructs the set of actions to choose, which we denote by X. Formally, X is the set of all functions from C to S, the axiomatic developed by Savage (Luce and Raifa, 1957) allows the decision maker to form a probability law on the events affecting the consequences and to compare the utility expectations according to this law. Savage's theorem is an extension of the theory of Von Neumann and Morgenstern. Indeed, the representation of the preference relation is similar to that developed by VNM, except that the probability distributions of the different states of nature are evaluated subjectively.

The Limits of Individual Rationality

Many authors have criticized the expected utility rule advocated by Von Neumann–Morgenstern supplemented by Savage. First, these criticisms have summer bets in light below the shape of what has been called "paradoxes" (first by Allais, then by Ellsberg). The presentation of these criticisms goes well beyond the scope of this work. However, it is essential to point out that there are a certain number of theoretical reasons which lead to the existence of these criticisms. These reasons arise from the models of microeconomic theory used in applications; it is often assumed that the individual's behavior conforms to this model while only a limited domain of the set of consumer decision problems is modeled. We are particularly interested in the difficulty of applying the Von Neumann and Morgenstern representation theorem to temporal distribution lotteries.

Time resolution

Spence and Zechauser (1972) demonstrate the inconsistency of utility functions when the timing of uncertainty resolution matters, that is when importance is attached to the temporal resolution of uncertainty. Starting from an example with a horizon of four steps, one of which represents the resolution of uncertainty, they show that when we swap the step of resolving uncertainty with another, the expected utility changes, contrary to the hypothesis of Von Neumann and Morgenstern. At the end of this work, the two authors note that time is absent from the VNM hypotheses while insisting on its importance in any decision-making problem. This leads to the conclusion that using the expected utility criterion to represent preferences obeying certain axioms is not legitimate. However, starting from an example of temporal income distribution, Porteus and Kreps (1979a) show that it is justified to return to the theorem of Von Neumann and Morgenstern by fixing specific a priori hypotheses: the probability distribution of the second-period income is given, and the order of resolution of the uncertainty is fixed.

By admitting this result, we can construct a helpful framework for dealing with the decision on climate change: We can consider that the probability distribution on the physical impacts of climate change is given once and for all. If, in addition, we assume that this distribution is known, that is to say, that we are in a risky universe and that the date of the information is also known. Nevertheless, the work of Kreps and Porteus warns that it is essential to be cautious about any attempt to extend this scheme to cases where the probability distribution over future states of nature and the first-period decision would not be independent.

Consistency of the criterion for maximizing expected utility

The difficulty of applying the principle of maximizing expected utility to situations where the probabilities of realization are subjective. The absence of time in the VNM and Savage models developed within the framework of this principle leads to questioning the prospect of resorting to a choice criterion other than maximizing expected utility. Such a criterion should help reduce the number of still undetermined parameters, exceptionally subjective probabilities. However, this solution has significant flaws; we cite, in particular, that the uncertainty about the likelihood of occurrence is irreducible given the problem of climate change and, consequently, that such a solution would be incompatible with the framework of the problem we are dealing with. In recent years, we have witnessed the development of new models within the theory of choices in uncertain situations. These models have contributed mainly to improving the so-called Non-Expected Utility theory. We can cite in particular the concept of ambiguity aversion of Gilboa and Shmeidler (1989); which stipulates that agents act in anticipation of the worst, by opting for the most unfavorable probability distribution. However, these models systematically produce inconsistencies when we consider temporal situations.

1.9. The Role of the Discount Rate in Environmental Decisions

The discount rate plays a critical role in evaluating environmental issues, renewable energy investment projects, where the costs of mitigating greenhouse gas emissions are incurred today while the benefits are realized in the distant future.

In a pure and perfect market, the discount rate reflects:

The subjective preference for the present—individuals' inclination to prioritize immediate benefits over future ones.

The productivity of capital—the market’s capacity to convert present resources into greater future goods through investments.

These rates are harmonized in an ideal market, ensuring the exchange rate between present and future values aligns with the opportunity cost of capital. However, debates persist about selecting an appropriate discount rate for long-term environmental investments.

The ethical discourse on discounting dates back to Pigou (1920) and Ramsey (1928). Ramsey argued for a zero-utility discount rate, emphasizing intergenerational equity and equal treatment across generations. However, critics like Koopmans (1960) and Mirrlees (1967) pointed out that a zero rate could lead to unrealistic policies, where the current generation sacrifices excessively for future gains. Conversely, a high discount rate disproportionately undervalues long-term benefits, jeopardizing investments with extended payback periods, such as renewable energy projects.

Arrow (1996) extended this debate by proposing a more balanced approach:

where:

- -

d: Preference for the present.

- -

g: Projected economic growth rate.

- -

n: Intertemporal elasticity of marginal utility of consumption (equal to 1 for logarithmic utility functions).

This formulation bridges ethical considerations and practical implications, balancing intergenerational fairness with present-day feasibility.

Empirical evidence suggests that individual preferences often deviate from standard economic models. Observations indicate that:

Hyperbolic discounting: Individuals tend to apply a declining discount rate over longer time horizons, reacting more strongly to near-term changes than distant ones.

Logarithmic discounting: This approach, formalized as: δ(t)=k⋅log(t) better reflects individuals' proportional, rather than absolute, sensitivity to time.

These findings highlight the need to move beyond classical exponential discounting to capture the nuances of real-world behavior.

When it comes to assessing long term projects such as a renewable energy transition, an appropriate discount rate is essential. A high discount rate reduces the present value of future benefits, making it less likely to invest in clean energy infrastructure. A low or declining discount rate, on the other hand, ensures that future benefits (like reduced greenhouse gas emissions) receive their due prioritization. Ethically attractive, zero-discount rate is not pragmatically appealing and economics, growth, intergenerational equity and market imperfections need to be factored in for pragmatic approach. This differentiated perspective is critical in structuring policies that underpin sustainable energy capital and climate change adaptation approaches.

Formalization of the concept of option value

Returning to option value, we are interested in formalizing it in the economic framework of managing climate change. We are situated within the framework of the theory of utility maximization. We propose to analyze the elementary formal model of the decision theory in uncertainty. The example that we consider in this paragraph (according to the work of Dasgupta and Heal, 1979) allows us to present this model.

Consider a two-period planning horizon of a decision situation about whether or not to conserve a system. Let t = 0 and t = 1, the two dates representing the time origins of the first and second periods, respectively. The decision taken by the planner at the beginning of the first period (t = 0) will allow the system to evolve between two states. The concept of irreversibility can characterize the transition from one state to another.

1.9.1. Modeling the renewable energy investment Management Problem

So far, we have been interested in the extent of the controversies raised by the design of policies for managing renewable energy investment. We now propose to explore this field of research by developing a simple model whose objective is to articulate the different elements of the renewable energy investment problem into a single object. In the literature, most analyses of behavior under uncertainty place the decision maker in a binary choice framework. In the simplest approach, two periods represent short-term and long-term choices. The decision is assumed to be made in the first period and to be subject to uncertainty about the environment that will prevail in the second period. In the simplest approach, two states of the world are possible. At the beginning of the second period, information arrives in one block, the true state of the environment becomes known, and probably several other decisions will be made. We propose to analyze the elementary formal model of the theory. We will try to situate ourselves within the framework of classical economics by imposing simplifying hypotheses on the different elements constituting the problem of renewable energy investment.

Consider a producer whose income of a representative individual is I. The benefit produced by this income is represented by the producer's utility function u(I), an increasing function of I at a decreasing rate. This function is assumed to be doubly continuous derivable. The occurrence of renewable energy investment and the events that may follow will brutally and definitively affect the well-being of this society. Let C be the date of occurrence of this event; we have assumed that this date is perfectly known by the planner. As a result, the planning period is naturally divided into two periods. Chronologically, the first period corresponds to the one preceding date C, during which the planner has only partial information. At the beginning of the second period, information will be revealed and the uncertainty about the state of nature will be dissipated. This framework will also assumes the availability of advanced technologies to transition quickly to renewable energy, mitigating the adverse impacts of delays on the investment. The key variabes are:

- -

I: Income remains the same but reflects the financial resources allocated to renewable energy investments.

- -

x: Represents the cost of investing in renewable energy infrastructure, such as solar panels, wind turbines, or smart grids.

- -

-

w, W: Potential losses under low (w) and high (W) adoption scenarios, where w<W. they reflect the financial losses associated with two states of nature:

- o

e₁ (low uptake of renewable energy): Corresponds to lower returns or slow adoption of renewable technologies.

- o

e₂ (high uptake of renewable energy): Corresponds to higher adoption rates but possibly higher technological or societal challenges.

- -

p: The probability of high adoption (e2)

- -

δ: The discount rate, reflecting the weight assigned to future costs and benefits.

The planner's choice is framed around renewable energy policy decisions:

"Do nothing and wait for more information," delaying the investment decision.

"Invest immediately in renewable energy infrastructure," committing to upfront costs.

Let’s Define utility as u(I), where u is an increasing and concave function representing the societal preference for wealth distribution. The Expected utility after investment in renewable energy is:

Here, p represents the subjective probability of high uptake (e2), and 1−p represents the probability of low uptake (e1).

The irreversibility of investment is captured by the upfront cost x, which cannot be recovered if uptake is low.

Value of information (VOI) quantifies the benefit of delaying investment until better data on adoption rates becomes available:

Investments should be made if the expected utility gain outweighs the cost of delay:

The discount rate (δ) serves as a crucial parameter in evaluating the costs and benefits of long-term investments in renewable energy, particularly under uncertainty. It represents the weight given to future costs or benefits relative to the present.

Formally: 0 ≤ δ ≤ 10

The parameter δt−1 assigns a weight to benefits or costs at time t, relative to time 1. The term (1−δ)×100 corresponds to the discount rate expressed as a percentage. This discounting process is instrumental in achieving the twin goals of equity and efficiency in intertemporal resource allocation.

The expected utility after adopting renewable energy is expressed as:

or equivalently:

where:

- -

u(I)Utility of income.

- -

p: Probability of high adoption.

- -

W,w: Costs under different adoption scenarios, with w<W.

The expected value of utility loss over one year due to delayed action on renewable energy investment is:

or:

The total discounted utility loss over T years is calculated as:

Additionally, the utility loss incurred annually when paying xxx, the cost of investment, is: Δ Ux=u(I)−u(I−x)

and its cumulative value up to time CCC is:

These expressions highlight the interplay between discount rates, utility, and investment costs in renewable energy decisions. For instance:

- -

A higher δ (lower discount rate) favors immediate investment by assigning greater weight to future benefits.

- -

A lower δ (higher discount rate) prioritizes present costs, potentially delaying action.

Discussion: Policy implications

Incentivize Early Adoption:

- -

Utilize subsidies, tax breaks, or feed-in tariffs that reduce the cost of renewable energy investments costs (x), thus incentivizing earlier adoption of renewable energy transistions. For example, Germany’s feed-in tarp model was a key factor for the solar uptake (Nuñez-Jimenez et al., 2022)

Encourage Research and Development: Encourage long-term contracts to mitigate perceived uncertainties (p) by ensuring stable returns to investors. Test innovations in battery storage and offshore wind technologies to drive down irreversibility costs and scale. By doing so, it becomes possible to generate cleaner energy and have a more resilient grid, both of which are vital to transition to more sustainable energy future. (Ventrelli, 2022)

- -

Support research and development to reduce technological and financial irreversibilities in renewable energy systems.

- -

Encourage breakthroughs that reduce the cost of entry (x) in emerging technologies such as battery storage or offshore wind.

Enabling Sharing of Information: Update renewable energy objectives on a regular basis to reflect new information and market developments.

- -

To enhance decision-making accuracy, create open-access data platforms for renewable energy potential, adoption rates, and technology costs.

- -

Funding studies with high value of information (VOI) Ensuring reliable forecasts about energy markets and climate impacts.

Implement Flexible Policies:

- -

Instituting adaptive policies incorporating new information as it becomes available, such as periodic reassessment of renewable energy goals and incentives.

- -

Develop policies that exploit uncertainty, like emissions pricing mechanisms that vary rates by emission reduction models.

Advocate Public-Private Partnerships:

- -

Promote public-private partnerships for risk sharing and lowering uncertainties in renewable energy projects.

- -

Use public financing to de-risk large-scale renewables, making them more confidence-inducing for private capital.

Such strategic partnership not only brings in the required investment but also speeds the creation and deployment of innovative energy solutions needed to achieve global climate objectives.

- 2.

For Private Investors

Utilize Scenario Analysis:

- -

The framework can be used to model alternative investments with different probabilities (p), costs (x), and discount rates (δ).

- -

Focus investments on areas VOI shows will yield the highest expected utility for the fund and society, building long-term returns in conjunction with societal value creation.

Hedge Against Risks:

- -

Reduce the risk of exposure to local uncertainty by diversifying renewable energy portfolios across technologies and regions.

- -

Use of insurance and financial instruments to mitigate risks of potential losses in low adoption scenarios (e1).

Implement Real Options Analysis:

- -

Apply the framework to projects with high irreversibility costs for optimal investment time.

- -

Before committing to large-scale projects, wait until further information is revealed, lessening risk exposure.

Invest in Innovation:

- -

Redirect capital toward next-generation renewable energy technologies that drive down long-term costs and improve scalability.

- -

Embrace governments and research institutions to use shared intelligence and public money.

- 3.

Broader Impacts

Socio-Economic Development:

- -

Governments can direct much-needed renewable energy investments in underprivileged areas, creating jobs and boosting access to energy.

- -

This will lead to equitable benefits from renewable projects and improve public acceptance of renewable energy transitions.

Global Climate Goals:

- -

Coordinate national renewable energy policies with international commitments, such as the Paris Agreement, to enhance collective impact.

- -

Finally, the framework will be utilized to define scientifically-based targets in terms of reductions in emissions and additions in renewable energy capacity.

2. Conclusion

Since the 20th century, environmental concerns have increasingly revolved around climate issues. As a highly intricate and nonlinear adaptive system, the climate exhibits extensive interconnections among its components. Numerous intergovernmental conferences and United Nations summits have focused on this complex system, leading to heightened global awareness about potential atmospheric disruptions and climate mechanisms. This has resulted in the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and an ongoing treaty that stabilizes anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, known to be responsible for these disruptions according to IPCC assessment reports.

This paper aims to address this debate by providing a comprehensive explanatory framework that connects the natural pathways and expected progression of greenhouse gases to improve the understanding of climate change scenarios. It also underscores the crucial need to improve climate models to introduce more layers of realism, which will guide more informed policy decisions. The historical context this work provides emphasizes the fundamental political difficulty of international negotiations, giving insight for future climate accords.

With the escalation of global warming, regional changes in average climate conditions and extreme weather events have become more pronounced. Climate change poses threats such as sea level rise, indicating an increased likelihood of coastal flooding events. It is concerning that climate-related hazards can trigger a cascade of risks across various sectors, spreading through interconnected natural and societal channels across regions. For instance, the simultaneous occurrence of a heat wave and drought affecting an agricultural area exemplifies the interlinked nature of multiple risks, resulting in cascading effects on biophysical, economic, and societal dimensions, extending even to distant regions. These cascading effects significantly impact vulnerable demographic groups, including smallholder farmers, children, and pregnant women.

The primary focus is on the anticipated global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the current decade resulting from Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) declared before COP26. These projections are expected to increase the likelihood of surpassing the 1.5 °C temperature limit. Moreover, the projections pose additional challenges beyond 2030, making it more difficult to constrain the temperature rise to below 2 °C. Thus, immediate actions are crucial to address this challenge effectively.

In summary, the complex response of the climate to the rise in greenhouse gas concentrations depends on intricate interactions within the atmospheric reservoir and with other natural and human systems. Estimating future climate change and its global consequences often overlooks local considerations, leading to rough, uneven, and incomplete economic assessments. The economic question arising in the face of exogenous and endogenous uncertainties revolves around the imprecision justifying decisions to prevent and combat climate change. Such regulatory policies require credible and firm commitments. Despite nations' intentions to combat climate change, action could be hindered without plausible information on its magnitude and consequences. Therefore, sophisticated assessments are essential to comprehensively understand the effects of climate change in different regions. Moreover, international organizations (UNFCCC) shall continue conducting global negotiations on climate change and provide financial and technical resources to developing countries. National governments must tighten up on climate laws, invest in green technologies, and support sectors in switching to low-carbon models. Supply chain sustainability needs to focus on private sector investments in clean technologies and climate risk disclosures through financial reports. Finally, sustainable practices and climate adaptation should be implemented with the support of local communities to help build resilience.

To address climate change, we need more than scientific breakthroughs; we need collaboration across disciplines and borders. This paper highlights the importance of breaking down barriers, between science, policy, and practice. Lessons learned from past agreements and the cutting-edge science of the latest developments provide a roadmap to tighten up climate laws, invest in green technologies, and build resilience through local adaptation work. In order to mitigate the impacts of climate change, action at the global level needs to be both decisive and inclusive, ensuring that no community is left behind on the road to a greener, sustainable future. We advocate for governance frameworks emphasizing equity, mainly supporting vulnerable regions and collaboration between scientists, policymakers, and communities.