Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Location

2.2. Study Description

2.2.1. Principal growth stage: Germination, sprouting, bud development

- 00

- Winter dormancy or resting period (Aubert and Lossois scale: A) (Table 2).

- 01

- Swelling of the yolk begins.

- 03

- End of yolk swelling.

- 07

- The yolk begins to open or sprout.

- 09

- The bud shows green shoots.

2.2.2. Principal growth stage: Leaf development

- 12

- Development of the second leaf (Table 2).

- 13

- Development of the third leaf (Table 2).

- 14

- Development of the fourth leaf.

- 15

- Development of the fifth leaf.

- 16

- Development of the sixth leaf.

- 17

- Development of the sevent leaf.

- 18

- Development of the eighth leaf.

- 19

- Develpoment of nine leaves or more.

2.2.3. Principal growth stage: Emergence of the flowering organ

2.2.4. Principal growth stage: Flowering

2.2.5. Principal growth stage: Fruit formation

2.2.6. Principal growth stage: Ripening of fruit and seeds or fruit colouring.

2.2.7. Principal growth stage: Beginning of dormancy.

| Principal Stage | BBCH code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Germination, sprouting, bud development | 00 | Winter dormancy or resting period |

| 01 | Swelling of the yolk begins | |

| 03 | End of yolk swelling | |

| 07 | The yolk begins to open or sprout | |

| 09 | The bud shows green shoots | |

| Leaf development | 10 | First leaves separate from the shoot |

| 11 | Development of the first leaf | |

| 12 | Development of the second leaf | |

| 13 | Development of the third leaf | |

| 1… | Continuation of stages until ... | |

| 19 | Develpoment of nine leaves or more | |

| Side shoot formation | 21 | First visible side shoot |

| 22 | Second visible side shoot | |

| 23 | Third visible side shoot | |

| 2… | Continuation of stages until ... | |

| 29 | Nine or more visible side shoots | |

| Emergence of the flowering organ | 51 | Flower organs or flower buds visible |

| 55 | First individual buds and buds (florets) visible (unopened) | |

| 59 | First petals (flower leaves) visible | |

| Flowering | 60 | First flowers, open |

| 61 | Beginning of flowering: 10% of flowers open | |

| 62 | 20% of open flowers | |

| 63 | 30% of flowers open | |

| 64 | 40% of flowers open | |

| 65 | Full flowering: 50% of flowers open | |

| 67 | Flowering coming to an end: most petals fallen or dry. | |

| 69 | End of flowering: fruit set visible. | |

| Fruit formation | 70 | First visible fruits. |

| 71 | Fruits reach 10% of their final size | |

| 72 | Fruits reach 20% of their final size | |

| 73 | Fruits reach 30% of their final size | |

| 74 | Fruits reach 40% of their final size | |

| 75 | Fruits reach 50% of their final size | |

| 76 | Fruits reach 60% of their final size | |

| 77 | Fruits reach 70% of their final size | |

| 78 | Fruits reach 80% of their final size | |

| 79 | The fruits have reached the size appropriate to their species/variety | |

| Ripening of fruit and seeds or fruit colouring | 81 | Beginning of ripening or fruit colouring |

| 85 | Continuation of fruit colouring according to species/variety | |

| 88 | Decrease in fruit consistency | |

| 89 | Full or harvest maturity | |

| Beginning of dormancy | 91 | End of wood or shoot growth, but foliage remains green |

| 93 | Beginning of leaf discolouration or leaf drop | |

| 95 | 50% of leaves discoloured or fallen off | |

| 97 | End of leaf fall. The plant is in winter dormancy or vegetative rest |

3. Results and Discussion

| BBCH Code | Phenological Code | Photography |

|---|---|---|

|

00 Winter dormancy or resting period. |

A |  |

|

12 Development of the second leaf. |

- |  |

|

13 Development of the third leaf. |

- |  |

|

16 Development of the sixth leaf. |

- |  |

|

51 Flower organs or flower buds visible. |

C |  |

|

55 First individual buds and buds (florets) visible (unopened). |

D |  |

|

60 First flowers, open. |

E |  |

|

65 Full flowering: 50% of flowers open |

F |  |

|

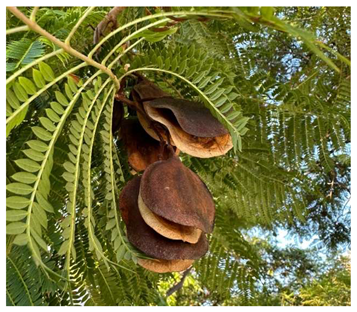

79 The fruits have reached the size appropriate to their species/variety.. |

H |  |

|

81 Beginning of ripening or fruit colouring. |

I |  |

|

85 Continuation of fruit colouring according to species/variety. |

- |  |

|

89 Full ripening or harvesting. End of the typical colouring depending on the species/variety. Fruit or infructescences detach relatively easily. |

J |  |

|

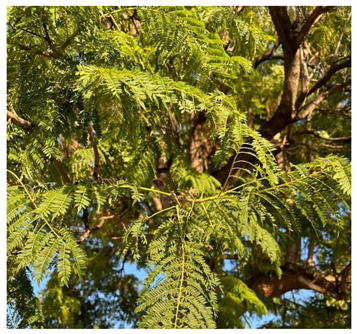

91 End of growth of wood or shoots (sprouts), but foliage remains green. |

- |  |

Author Contributions

References

- ACOSTA-QUEZADA, P.G.; RIOFRÍO-CUENCA, T.; ROJAS, J.; VILANOVA, S.; PLAZAS, M.; PROHENS, J. ; 2016. Phenological growth stages of tree tomatos (Solanum betaceum Cav.) an emerging fruit crop, according to the basic and extended BBCH scales. Scientia Horticulturae, 199, 216–233.

- AGUIRRE, Z. ; 2015. Pasado, presente y futuro de los “guayacanes” Handroanthus chrysanthus (Jacq.) S. O. Grose y Handroanthus billbergii (Bureau & K. Schum.) S. O. Grose, de los bosques secos de Loja, Ecuador. Arnaldoa, 22, 85–104.

- AGUIRRE-BECERRA, H.; PINEDA-NIETO, S.A.; GARCÍA-TREJO, J.F.; GUEVARA-GONZÁLEZ, R.G.; FEREGRINO-PÉREZ, A.A.; ÁLVAREZ-MAYORGA, B.L.; RIVERA, D.M. ; 2020. Jacaranda flower (Jacaranda mimosifolia) as an alternative for antioxidant and antimicrobial use. Heliyon, 6, 1–9.

- AGUSTÍ, M.; ZARAGOZA, S.; BLEIHOLDER, H.; BUHR, L.; HACK, H.; KLOSE, R.; STAUB, R. ; 1995. Escala BBCH para la descripción de estadios fenológicos del desarrollo de los agrios (Gén. Citrus). Levante Agrícola, 3, 189–199.

- ALCARAZ, M.L.; THORP, T.G.; HORMAZA, J.I. ; 2013. Phenological growth stages of avocado (Persea americana) according to the BBCH scale. Scientia Horticulturae, 164, 434–439.

- ALVARADO, A.M.; FOROUGHBAKHCH, R.; JURADO, E.; ROCHA, A. ; 2002. El cambio climático y la fenología de las plantas. Ciencia UANL, 4, 493–500.

- AUBERT, B.; LOSSOIS, P. ; 1972. Considérations sur le phènologie des espèces fruitières arbustives. Fruits, 27, 269–286.

- BAGGIOLINI, M. ; 1952. Les stades repères dans le développement annuel de la vigne et leur utilisation practique. Rev. Rom. Agric. 1952, 8-10.

- BLEIHOLDER, H.; VAN DEN BOOM, T.; LANGELÜDDEKE, P.; STAUSS, R. ; 1989. Einheitliche Codierung der phänologischen Stadien bei Kultur- und Schadpflanzen. Gesunde Pflanzen, 41, 381–384.

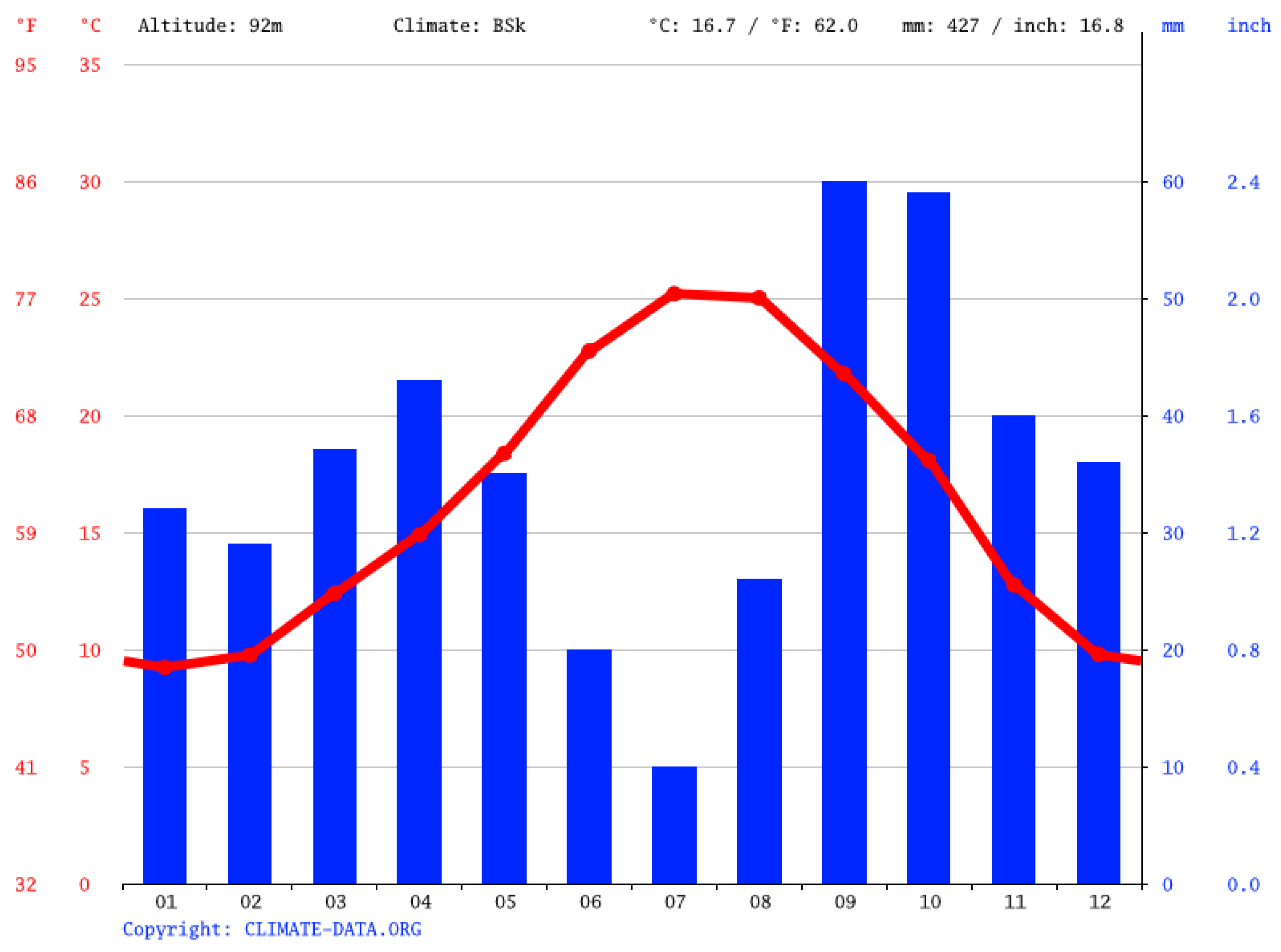

- CLIMATE DATA, 2024. Available online: https://es.climate-data.org/europe/espana/comunidad-valenciana/betera-56926/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- DUBÉ, P.A.; PERRY, L.P.; VITTUM, M.T. ; 1984. Instructions for phenological observations: Lilac and honeysuckle. Vermort Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin, 692.

- DIMITRI, M.J.; LEONARDIS, R.F.J.; BILONI, J.S. ; 1977. Especies Forestales de la Argentina Occidental, en: Libro del Árbol, Ed. El Ateneo. 35-44.

- FABRIS H., A. ; 1959. Bignoniáceas. Las plantas cultivadas en la República Argentina, 10, 1–57.

- FABRIS, H. A. ; 1965. Flora Argentina: Bignoniaceae. Rev. Mus. La Plata, 9, 273–419.

- FABRIS, H. A. ; 1979. Bignoniaceae, in Burkart A. Fl. Il. Entre Ríos, Colec. Ci. Inst. Nac. Tecnol. Agropecu. 6, 504–526.

- FABRIS, H. A. ; 1993. Bignoniaceae, in Cabrera, A.L. Fl. Prov. Jujuy, Colec. Ci. Inst. Nac. Tecnol. Agropecu. 13, 226–262.

- FITTER, A.H.; FITTER, R.S.; 2002. Rapid changes in flowering time in British plants. Science 296( 5573), 1689–1691. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FLECKINGER, J. ; 1946. Notations phénologiques et représentations du développement des bourgeons floraux du porier. Fruit Belge, 14, 41–54.

- FLECKINGER, J. 1948. Les stades vegétatifs des arbres fruitiers, en raport avec les traitements. Pomologie Francaise Supplément, 81-93.

- FONT QUER, P. 1953. Diccionario de Botánica. Ed. Labor, Barcelona, España. 642 pp.

- GACHET, M.S.; SCHÜHLY, W. ; 2009. Jacaranda—An ehtnopharmacological and phytochemical review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 121, 14–27.

- GILMAN, E.F.; WATSON, D.G. 1993. Jacaranda mimosifolia. Fact sheet ST-317.

- HACK, H.; BLEIHOLDER, H.; BUHR, U.; MEIER, U.; SCHNOCK-FRICKE, U.; WEBER, E.; WITZENBERGER, A. ; 1992. A uniform code for phenological growth stages of mono-and dicotyledonous plants—Extended BBCH scale, general. Nachr. Des. Dtsch. Pflan-Zenschutzd, 44, 265–270.

- HACK, H.; GALL, H.; KLEMKE, T.; KLOSE, R.; MEIER, R.; STAUSS, R.; WITZENBERGER, A. 1993. The BBCH scale for phenological growth stages of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.), in: Growth Stages of Mono and Dicotyledonous BBCH Monograph, Federal Biological Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry.

- HERNÁNDEZ DELGADO, P.M.; ARANGUREN, M.; REIG, C.; FERNÁNDEZ GALVÁN, D.; MESEJO, C.; MARTÍNEZ FUENTES, A.; GALÁN SAÚCO, V.; AGUSTÍ, M. 2011. Phenological growth stages of mango (Mangifera indica L.) according to the BBCH scale. Scientia Horticulturae 130, 536-540.

- HERRAIZ, F.J.; VILANOVA, S.; PLAZAS, M.; GRAMAZIO, P.; ANDÚJAR, I.; RODRÍGUEZ-BURRUEZO, A.; FITA, A.; ANDERSON, G.J.; PROHENS, J. ; 2015. Phenological growth stages of pepino (Solanum muricatum) according to the BBCH scale. Scientia Horticulturae, 183, 1–7.

- INSTITUTO VALENCIANO DE INVESTIGACIONES AGRARIAS (IVIA). Available online: http://riegos.ivia.es/datos-meteorologicos (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- LAHITTE, H.J.; HURRELL, J.; BELGRANO, M.; JANKOWSKI, L.; HELOVA, P.; MEHLTRETE, K. 1998. Plantas medicinales Rioplatenses. Buenos Aires: Ed. L.O.L.A. 240 pp.

- LANCASHIRE, P.D.; VAN DEN BOOM, T.; LANGELÜDDEKE, P.; STAUSS, R.; WEBER, E.; WITZENBERGER, A. ; 1991. A uniform decimal code for growth stages of crops and weeds. Ann. Appl. Biol. 119, 561–601.

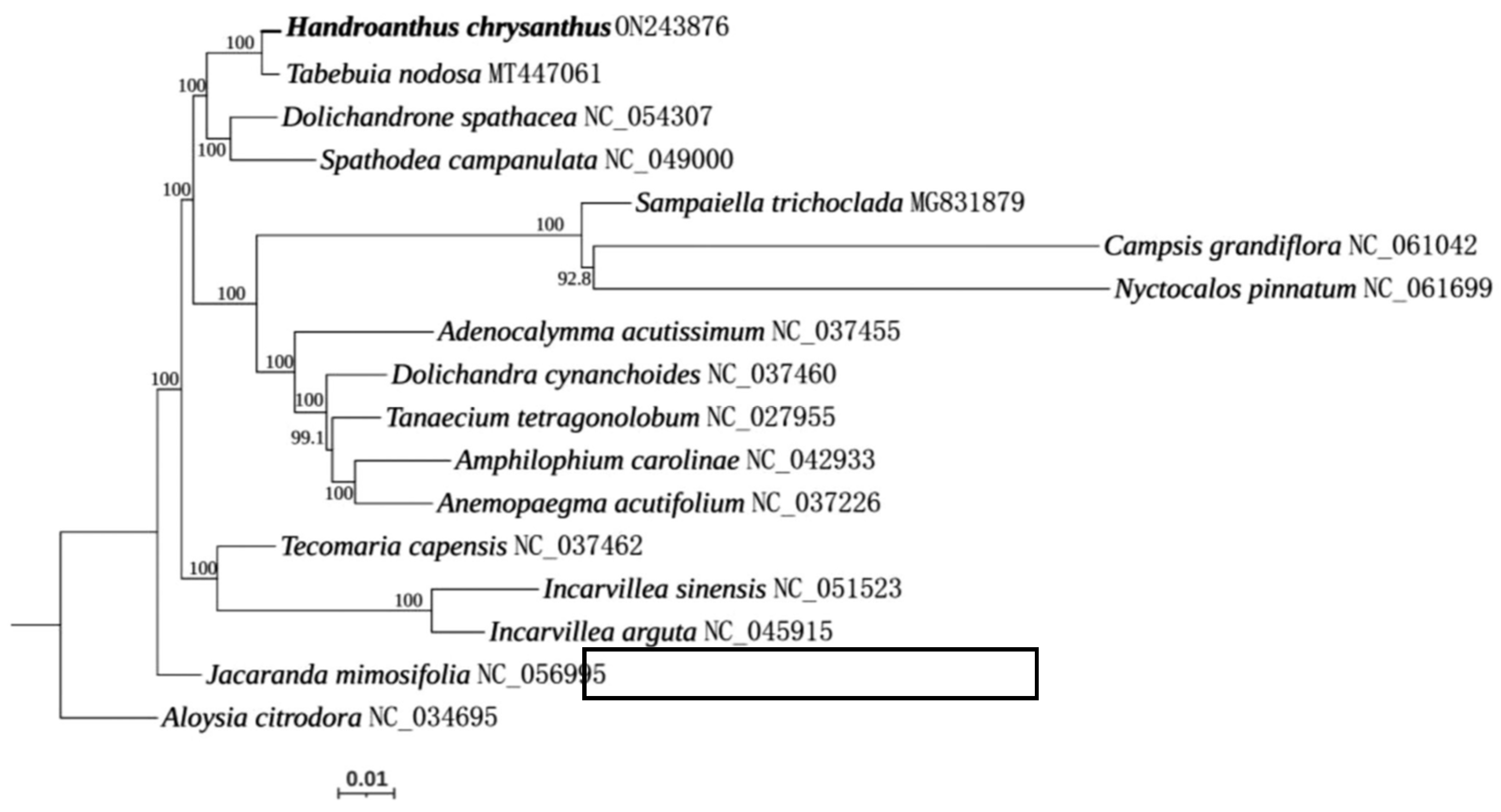

- LIAO, H.; MAN-MAN, S.; ZHOU, H.; LIU, X. ; 2022. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Handroanthus chrysanthus (Bignonaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 7, 1479–1480.

- LÓPEZ, I.; SALAZAR, D.M.; RECIO, D. ; 2004. Fenología del Olivo. Comparación de distintas notaciones fenológicas. Fruticultura Profesional, 145, 35–49.

- LÓPEZ GONZÁLEZ, G. 2006. Los árboles y arbustos de la Península Ibérica e Islas Baleares. Mundi-Prensa. 1731 pp.

- MACOUZET, M.; CASTILLÓN, E.; JIMÉNEZ, J.; VILLAREAL, J.; HERRERA, M. 2013. Plantas medicinales de Miquihuana, Tamaulipas. México: Universidad Autónoma de Nueva León. 146 pp.

- MEIER, U. ; 1985. Die Merkblattserie 27 «Entwicklungsstadien von Pflanzen» der Biologischen Bundesanstalt fúr Land- und Forstwirtschaft. Nachrichtenbl. Deut Pflanzenschutzd, 37, 76–77.

- MEIER, U.; BLEIHOLDER, H.; BUHR, L.; FELLER, C.; HACK, H.; HEB, M.; LANCASHIRE, P.; SCHNOCK, U.; STAUB, R.; VAN DE BOOM, T.; WEBER, E.; ZWERGER, P. ; 2009. The BBCH system to coding the phenological growth stages of plants -history and publications-. Journal für Kulturpflanzen, 61, 41–52.

- MOSTAFA, N.M.; ELDAHSHAN, O.A.; SINGAB, A.N. ; 2014. The genus Jacaranda (Bignoniaceae): An updated review. Pharmacognosy communications, 4, 1–9.

- NAVARRO, E. ; 1966. Evolución de los cultivos en Bétera. Tesis Doctoral en Filosofía y Letras. U. de Valencia.

- RANA, A.; BHANGALIA, S.; PRATAP SINGH, H. 2012. A new phenylethanoid glucoside from Jacaranda mimosifolia. Formerly Natural Product Letters 27(13), 1167-1173.

- SCHWARTZ, M.D. ; 2013. Phenology: An integrative environmental science. Ed. Springer. New York. 610 pp.

- SIDJUI, L.; PLACIDE, O.; NGOSONG, G.; MENKEM, E.; KOUIPOU, R.M.; MAHIOU-LEDDET, V.; HERBETTE, G.; BOYOM, F.; OLLIVIER, E. 2014. Secondary metabolites from Jacaranda mimosifolia and Kigelia africana (Bignonaceae) and their anticandidal activity. Records of natural products 8(3), 307-311.

- SMITH-RAMÍREZ, C.; ARMESTO, J.J.; FIGUEROA, J. 1998. Flowering, fruiting and seed germination in Chilean rain forest myrtaceae: ecological and phylogenetic constraints. Plant Ecology 136, 119-131.

- STAUSS, R. 1994. Compendium of growth stage identificación keys for mono and dicotyledonous plants. Extended BBCH scale. Postfach, Basel: CibaGeigy AG. ISBN 3-9520749-0-x.

- TORRICO, G.; PECA, C.; GARCIA, E. 1994. Leñosas útiles de Potosí. Potosí. 469 pp.

- VAVILOV, N. 1992. Origin and geography of cultivated plants. Cambridge University. 498 pp.

- WOLKOVICH, E.M.; COOK, B.I.; ALLEN, J.M.; CRIMMINS, T.M.; BETANCOURT, J.L.; TRAVERS, S.E.; PAU, S.; REGETZ, J.; DAVIES, T.J.; KRAFT, N.J.B.; AULT, T.R.; BOLMGREM, K.; MAZER, S.J.; McCABE, G.J.; McGILL, B.J.; PARMESAN, C.; SALAMIN, N.; SCHWARTZ, M.D.; CLELAND, E.E. 2012. Warming experiments underpredict plant phenological responses to climate change. Nature 485, 494-497.

- ZADOKS, J.C.; CHANG, T.T.; KONZAK, C.F. 1974. A decimal code for the growth stages of cereals. Weed Research 14, 415-421.

| Phenological Stage | Accumulated Degree Days | Difference Degrees Day |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (A) - Winter dormancy or resting period | 0 | 0 |

| 12 - Development of the second leaf | 394 | 394 |

| 13 - Development of the third leaf | 463 | 69 |

| 16 - Development of the sixth leaf | 650 | 581 |

| 51 (C) - Flower organs or flower buds visible | 705 | 124 |

| 55 (D) - First individual buds and flower buds (florets) visible (unopened) | 840 | 716 |

| 60 (E) - First flowers, open | 992 | 276 |

| 65 (F) - Full flowering: 50% of flowers open; first petals fall off or dry up | 1186 | 910 |

| 79 (H) - Fruits have reached the size appropriate to their species/ variety | 1771 | 861 |

| 81 (I) - Beginning of ripening or fruit colouring | 3348 | 2487 |

| 85 - Continuation of fruit colouring according to species/ variety | 3534 | 1047 |

| 89 (J) - Full ripening or harvesting. End of species-typical colouring. | 3720 | 2673 |

| 91 - End of wood or shoot growth (shoots), green foliage | 3800 | 1127 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).