Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Consideration

2.2. Place of Experiment

2.3. Selection of Birds and Experimental Design

2.4. INH Preparation

2.5. LH plasma Concentration Measurement

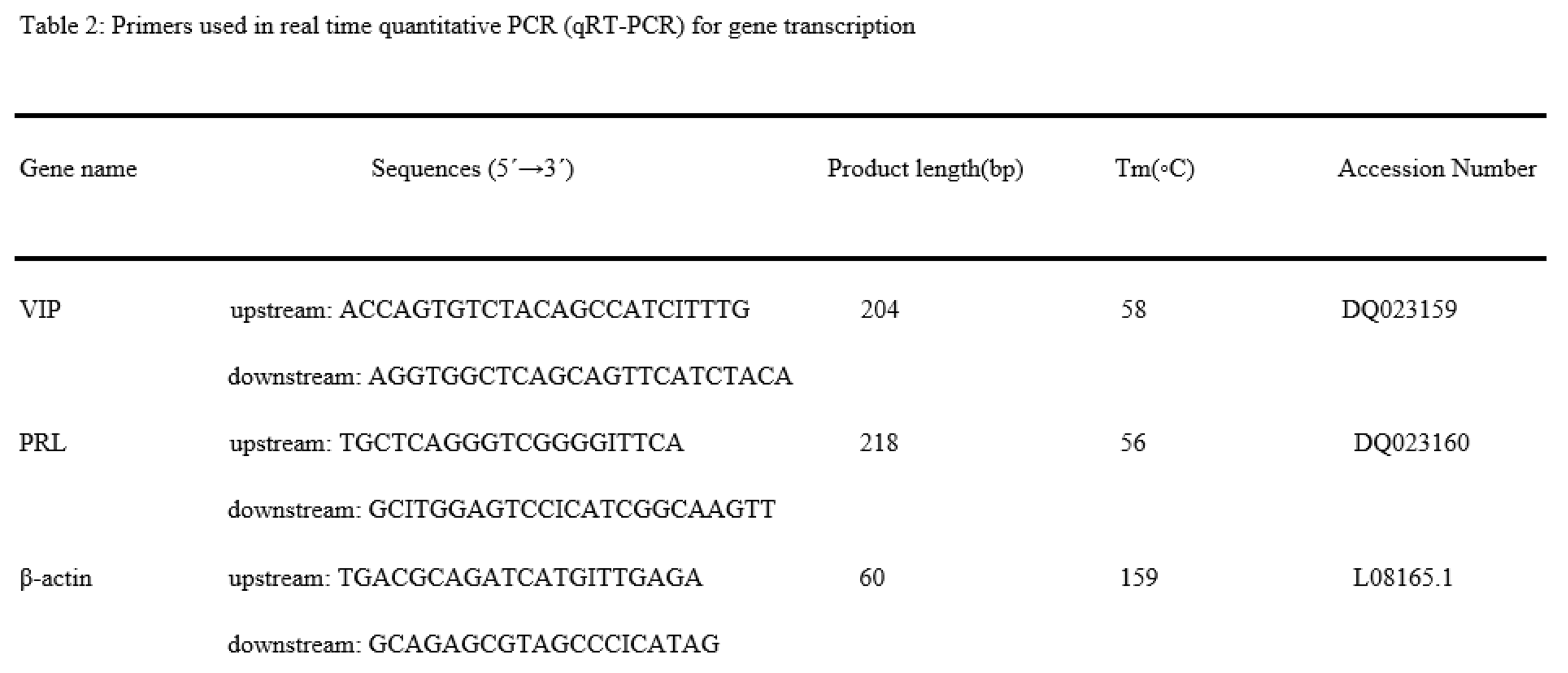

2.6. Isolation of, Synthesize Complementary DNA (cDNA) Synthesis, and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.7. Tissue Sample Collection

2.8. Microscopy

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

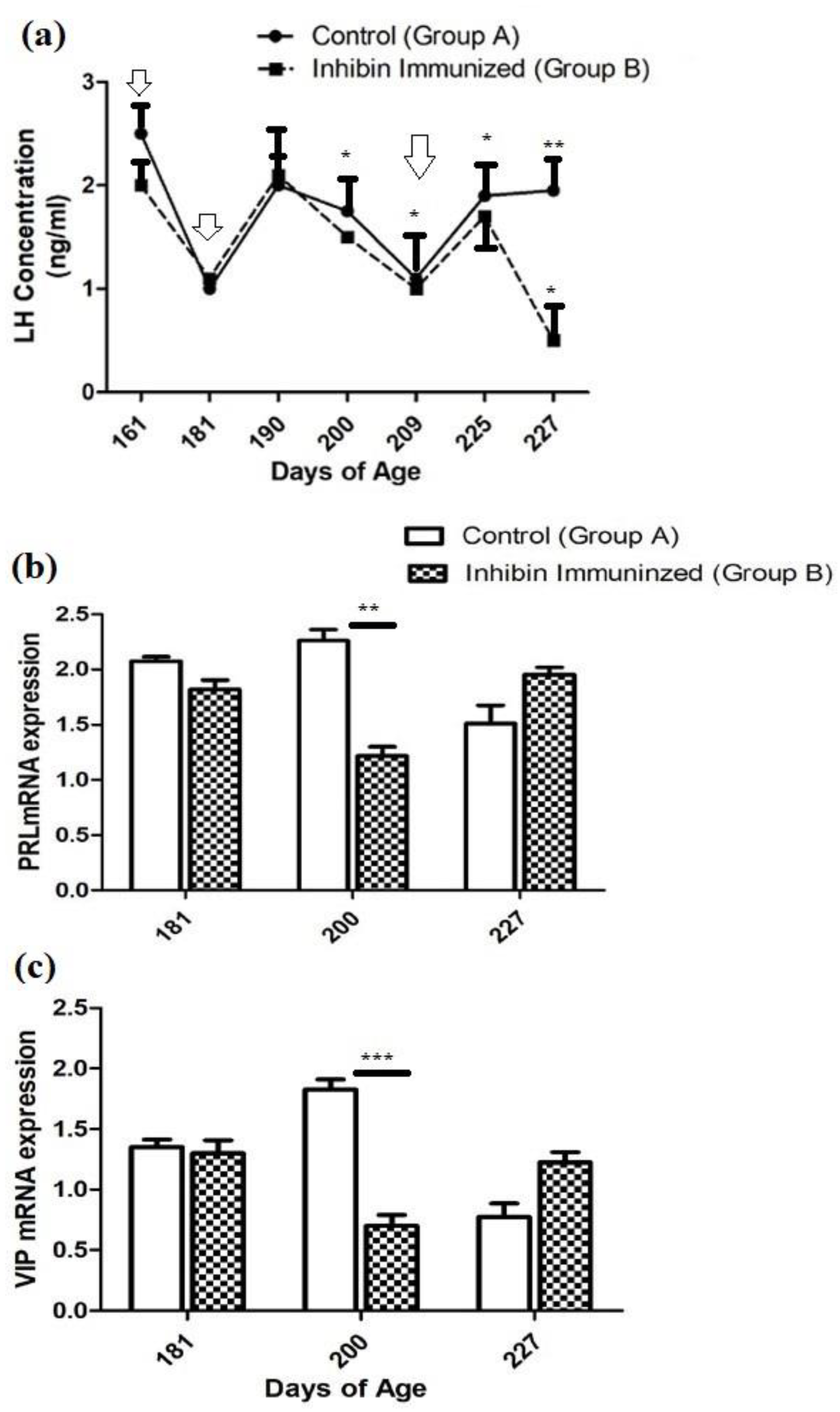

3.1. Plasma LH Concentrations

3.2. Pituitary Prolactin (PRL) mRNA Expression

3.3. Hypothalamic Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP) mRNA Expression

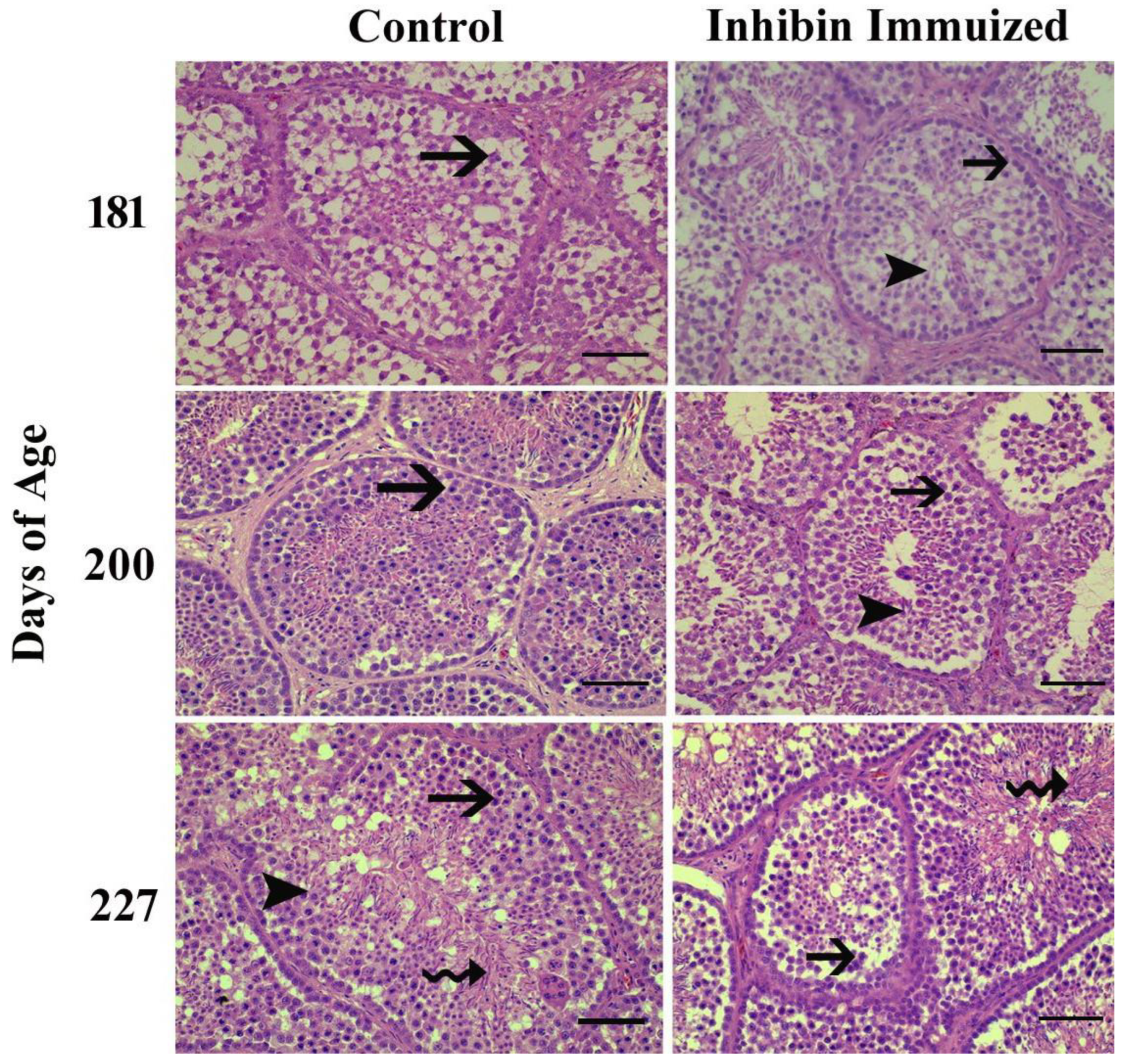

3.4. Histology of Testes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kubini, K.; Zachmann, M.; Albers, N.; Hiort, O.; Bettendorf, M.; Wölfle, J.; Bidlingmaier, F.; Klingmüller, D. Basal inhibin B and the testosterone response to human chorionic gonadotropin correlate in prepubertal boys. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2000, 85, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Luisi, S.; Florio, P.; Reis, F.M.; Petraglia, F. Inhibins in female and male reproductive physiology: role in gametogenesis, conception, implantation and early pregnancy. Human reproduction update 2005, 11, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laniyan, D.; Charles-Davies, M.; Fasanmade, A.; Olaniyi, J.; Oyewole, O.; Owolabi, M.; Adebusuyi, J.; Hassan, O.; Ajobo, B.; Ebesunun, M. Inhibin B levels in relation to obesity measures and lipids in males with different numbers of metabolic syndrome components. 2016.

- Weng, Q.; Medan, M.S.; Ren, L.; Watanabe, G.; Arai, K.Y.; Taya, K. Immunolocalization of inhibin/activin subunits in the Shiba goat fetal, neonatal, and adult testes. Journal of Reproduction and Development 2005, 51, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muttukrishna, S.; Farouk, A.; Sharma, S.; Evans, L.; Groome, N.; Ledger, W.; Sathanandan, M. Serum activin A and follistatin in disorders of spermatogenesis in men. European journal of endocrinology 2001, 144, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedqyar, M.; Weng, Q.; Watanabe, G.; Kandiel, M.M.; Takahashi, S.; Suzuki, A.K.; Taneda, S.; Taya, K. Secretion of inhibin in male Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) from one week of age to sexual maturity. Journal of Reproduction and Development 2008, 54, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avital-Cohen, N.; Heiblum, R.; Argov, N.; Rosenstrauch, A.; Chaiseha, Y.; Mobarkey, N.; Rozenboim, I. The effect of active immunization against vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and inhibin on reproductive performance of aging White Leghorn roosters. Poultry science 2012, 91, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L.I.; Fahrenkrug, J.; Schaffalitzky De Muckadell, O.; Sundler, F.; Håkanson, R.; Rehfeld, J.R. Localization of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) to central and peripheral neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1976, 73, 3197–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S.I.; Rosenberg, R.N. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide: abundant immunoreactivity in neural cell lines and normal nervous tissue. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1976, 192, 907–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosselin, G.; Maletti, M.; Besson, J.; Rostène, W. A new neuroregulator: the vasoactive intestinal peptide or VIP. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 1982, 27, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P.J.; Blache, D. A neuroendocrine model for prolactin as the key mediator of seasonal breeding in birds under long- and short-day photoperiods. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology 2003, 81, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnese, M.; Rosati, L.; Prisco, M.; Coraggio, F.; Valiante, S.; Scudiero, R.; Laforgia, V.; Andreuccetti, P. The VIP/VPACR system in the reproductive cycle of male lizard Podarcis sicula. General and comparative endocrinology 2014, 205, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosati, L.; Prisco, M.; Di Fiore, M.M.; Santillo, A.; Sciarrillo, R.; Valiante, S.; Laforgia, V.; Coraggio, F.; Andreuccetti, P.; Agnese, M. Sex steroid hormone secretion in the wall lizard Podarcis sicula testis: The involvement of VIP. Journal of experimental zoology. Part A, Ecological genetics and physiology 2015, 323, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnese, M.; Rosati, L.; Coraggio, F.; Valiante, S.; Prisco, M. Molecular cloning of VIP and distribution of VIP/VPACR system in the testis of Podarcis sicula. Journal of experimental zoology. Part A, Ecological genetics and physiology 2014, 321, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renthlei, Z.; Yatung, S.; Lalpekhlui, R.; Trivedi, A.K. Seasonality in tropical birds. Journal of experimental zoology. Part A, Ecological and integrative physiology 2022, 337, 952–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiseha, Y.; Halawani, M.E.E. Neuroendocrinology of the Female Turkey Reproductive Cycle. The Journal of Poultry Science 2005, 42, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumułka, M.; Rozenboim, I. Effect of breeding stage and photoperiod on gonadal and serotonergic axes in domestic ganders. Theriogenology 2015, 84, 1332–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumułka, M.; Rozenboim, I. Mating activity of domestic geese ganders (Anser anser f. domesticus) during breeding period in relation to age, testosterone and thyroid hormones. Anim Reprod Sci 2013, 142, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumułka, M.; Rozenboim, I. Breeding period-associated changes in semen quality, concentrations of LH, PRL, gonadal steroid and thyroid hormones in domestic goose ganders (Anser anser f. domesticus). Anim Reprod Sci 2015, 154, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.D.; Huang, Y.M.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.W.; Proudman, J.A.; Yu, R.C. Seasonal and photoperiodic regulation of secretion of hormones associated with reproduction in Magang goose ganders. Domestic animal endocrinology 2007, 32, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerysz, A.; Lukaszewicz, E. Effect of dietary selenium and vitamin E on ganders' response to semen collection and ejaculate characteristics. Biological trace element research 2013, 153, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Yu, J.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, Z.; Ning, Z.; Qu, L. Origins, timing and introgression of domestic geese revealed by whole genome data. Journal of animal science and biotechnology 2023, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Smitz, J. Luteinizing hormone and human chorionic gonadotropin: origins of difference. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 2014, 383, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Rodriguez, A.; Kauffman, A.S.; Cherrington, B.D.; Borges, C.S.; Roepke, T.A.; Laconi, M. Emerging insights into hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis regulation and interaction with stress signalling. Journal of neuroendocrinology 2018, 30, e12590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avital-Cohen, N.; Heiblum, R.; Argov, N.; Rosenstrauch, A.; Chaiseha, Y.; Mobarkey, N.; Rozenboim, I. The effect of active immunization against vasoactive intestinal peptide and inhibin on reproductive performance of young White Leghorn roosters. Poultry science 2011, 90, 2321–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhu, Y.L.; Xue, J.H.; Zhang, S.L.; Ma, Z.; Shi, Z.D. Immunization against inhibin enhances both embryo quantity and quality in Holstein heifers after superovulation and insemination with sex-sorted semen. Theriogenology 2009, 71, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovell, T.M.; Knight, P.G.; Groome, N.P.; Gladwell, R.T. Measurement of dimeric inhibins and effects of active immunization against inhibin alpha-subunit on plasma hormones and testis morphology in the developing cockerel. Biol Reprod 2000, 63, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, H.; El Sayed, M.A.; Nagaoka, K.; Sasaki, K.; El-Maaty, A.M.A.; Karen, A.; Abou-Ahmed, M.M.; Watanabe, G. Passive immunization against inhibin increases testicular blood flow in male goats. Theriogenology 2020, 147, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.F.; Shafiq, M.; Ali, I. Improving gander reproductive efficacy in the context of globally sustainable goose production. Animals 2021, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

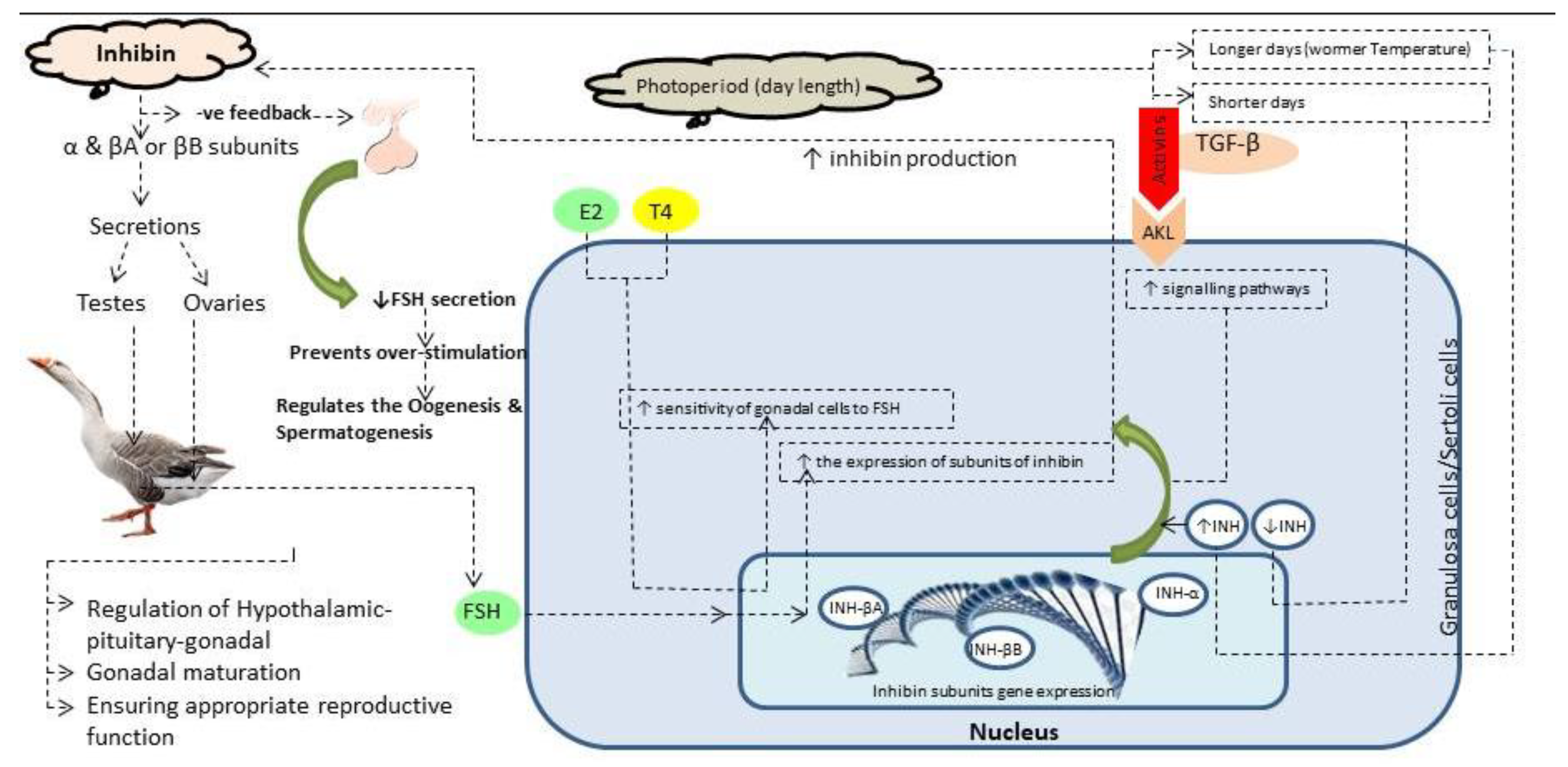

- Han, Y.; Jiang, T.; Shi, J.; Liu, A.; Liu, L. Review: Role and regulatory mechanism of inhibin in animal reproductive system. Theriogenology 2023, 202, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Li, Z.F.; Yang, W.X.; Tan, F.Q. Follicle-stimulating hormone signaling in Sertoli cells: a licence to the early stages of spermatogenesis. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E 2022, 20, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themmen, A.P.; Huhtaniemi, I.T. Mutations of gonadotropins and gonadotropin receptors: elucidating the physiology and pathophysiology of pituitary-gonadal function. Endocrine reviews 2000, 21, 551–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R.T.; O’Hara, L.; Smith, L.B. Gonadotropin and steroid hormone control of spermatogonial differentiation. The Biology of Mammalian Spermatogonia 2017, 147–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.-L.; Han, L.; Ahmad, S.; Cao, S.-X.; Xue, L.-Q.; Xing, Z.-F.; Feng, J.-Z.; Liang, A.-X.; Yang, L.-G. Effect of a DNA vaccine harboring two copies of inhibin α (1-32) fragments on immune response, hormone concentrations and reproductive performance in rats. Theriogenology 2012, 78, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D.A.; Cui, X.; Schmittling, R.J.; Sanchez-Perez, L.; Snyder, D.J.; Congdon, K.L.; Archer, G.E.; Desjardins, A.; Friedman, A.H.; Friedman, H.S. Monoclonal antibody blockade of IL-2 receptor α during lymphopenia selectively depletes regulatory T cells in mice and humans. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2011, 118, 3003–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Tian, Y.; Wu, W.; Wang, Z. Controlling reproductive seasonality in the geese: a review. World's Poultry Science Journal 2008, 64, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolla, E.; Pérez, J.H.; Dunn, I.C.; Meddle, S.L.; Stevenson, T.J. Neuroendocrine Regulation of Seasonal Reproduction. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Neuroscience; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.; Reed, S.; Kimmitt, A.; Alford, K.; Stricker, C.; Ketterson, E. Breeding at higher latitude as measured by stable isotope is associated with higher photoperiod threshold and delayed reproductive development in a songbird. bioRxiv 2019, 789008. [Google Scholar]

- Drobniak, S.M.; Gudowska, A. Seasonality, diet, and physiology as a predominant control factors of the moult dynamics in birds–a meta-analysis. 2020.

- Meng, J.; Feng, J.H.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, H.; Lan, X.; Wang, S. Active immunization with inhibin DNA vaccine promotes spermatogenesis and testicular development in rats. Journal of Applied Animal Research 2024, 52, 2360408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VAN DISSEL-EMILIANI, F.M.; GROOTENHUIS, A.J.; JONG, F.H.D.; ROOIJ, D.G.D. Inhibin reduces spermatogonial numbers in testes of adult mice and Chinese hamsters. Endocrinology 1989, 125, 1898–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.F.; Ahmad, E.; Ali, I.; Shafiq, M.; Chen, Z. The Effect of Inhibin Immunization in Seminiferous Epithelium of Yangzhou Goose Ganders: A Histological Study. Animals 2021, 11, 2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Chaturvedi, C.M. Testicular atrophy and reproductive quiescence in photorefractory and scotosensitive quail: involvement of hypothalamic deep brain photoreceptors and GnRH-GnIH system. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2017, 175, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.F.; Wei, Q.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Z.; Ahmad, E.; Zhendan, S.; Shi, F. The role of active immunization against inhibin α-subunit on testicular development, testosterone concentration and relevant genes expressions in testis, hypothalamus and pituitary glands in Yangzhou goose ganders. Theriogenology 2019, 128, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voge, J.; Wheaton, J. Effects of immunization against two inhibin antigens on daily sperm production and hormone concentrations in ram lambs. Journal of animal science 2007, 85, 3249–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivinski, J. Sperm in competition. Sperm competition and the evolution of animal mating systems 1984, 85–115. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, K.; Hua, G.; Ahmad, S.; Liang, A.; Han, L.; Wu, C.; Yang, F.; Yang, L. Action mechanism of inhibin α-subunit on the development of Sertoli cells and first wave of spermatogenesis in mice. PLoS One 2011, 6, e25585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, Z.; Shao, X.; Yu, J.; Wei, C.; Dai, Z.; Shi, Z. Reproductive axis gene regulation during photostimulation and photorefractoriness in Yangzhou goose ganders. Frontiers in zoology 2017, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Bai, W.; Hui, F.; Yang, L.; Cao, S.; Xu, Y. Effect of inhibin gene immunization on antibody production and reproductive performance in Partridge Shank hens. Theriogenology 2016, 85, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumułka, M.; Rozenboim, I. Breeding period-associated changes in semen quality, concentrations of LH, PRL, gonadal steroid and thyroid hormones in domestic goose ganders (Anser anser f. domesticus). Animal reproduction science 2015, 154, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Day of Age | Control (Kg) | INH Immunized (Kg) |

|---|---|---|

| 181 | 4.73 | 4.68 |

| 200 | 4.41 | 4.54 |

| 227 | 4.56 | 4.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).