1. Introduction

Surgical castration has been a frequently used method in veterinary medicine to address problems associated with sexual maturity in animals. It has been employed to control animal overpopulation, reduce male aggressiveness, prevent sexual odor in pork, and improve body growth rates in production animals, among other uses. However, this practice presents several drawbacks, mainly related to animal welfare, such as the pain it causes to the castrated individual, particularly in intensive production systems where anesthesia is usually not applied, in addition to possible infections due to poor postoperative management and even the death of the animal.

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) is a decapeptide that plays a central role in mammalian reproduction [

1,

2,

3]. It is secreted from the mediobasal portion of the hypothalamus and transported via axons to the median eminence, where it is released into the hypothalamic-pituitary portal circulation, inducing the release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary [

4], which promote ovarian follicle maturation in females and spermatogenesis in males [

1].

For many years, efforts have been made to immunoneutralize GnRH, blocking its entry into the pituitary [

5]. This technique, known as immunocastration, allows blocking hormone's action through an immunological preparation, eliminating the production and release of the sex steroids responsible for reproductive capacity and sexual behavior [

6] (The mechanism of action involves preventing the interaction of GnRH with receptors on gonadotropic cells located in the pituitary by binding the hormone to specific antibodies, thereby inhibiting the entire subsequent hormonal cascade [

7,

8] .

GnRH is an ideal candidate for inducing immunocastration in animals because a single product is effective in both males and females, and its amino acid sequence is identical across all mammals [

7,

9] . However, the main challenge in inducing an immune response against this hormone lies in its low immunogenicity due to its small size, which is insufficient to act as an antigen [

1].

It is for this reason that, to effectively induce the production of neutralizing antibodies against GnRH, it must be coupled to carrier molecules [

10,

11] . To generate an effective immune response, it has been conjugated with highly immunogenic molecules such as bovine serum albumin, ovalbumin, and keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH). Additionally, some formulations include pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which stimulate antigen-presenting cells to generate an adaptive immune response of effective magnitude and duration [

12,

13].

Immunocastration has several implications in veterinary medicine. Primarily, it is used to replace surgical castration, a practice associated with pain and health risks in animals, especially in production settings where anesthesia is commonly not applied. This affects animal welfare and can lead to inflammation, bleeding, hernia predisposition, and significant economic losses [

14]. In contrast, immunocastration is considered an ethical, practical, cost-effective, and efficient procedure[

15,

16]. In the swine industry, immunocastration is used to eliminate sexual odor, a sensory defect affecting meat from intact males caused by two compounds: androstenone and skatole, which accumulate in male pig adipose tissue upon reaching puberty, imparting an unpleasant odor and flavor to the meat [

17,

18]. . In cattle raised for meat production, immunization against GnRH has been proposed as a late-stage strategic castration method for males, improving animal welfare while providing the benefits of surgical castration. It serves as a key management tool to enhance carcass quality through increased fat deposition and reduces aggressive and sexual behavior [

19,

20]. In other species, such as dogs and cats, immunocastration can be applied mainly as a method for controlling reproduction and reducing male aggression [

21]. In addition, control of aggressive behavior has also been seen in Holstein bulls [

22].

Currently, there are nine immunocastration vaccines on the market. Among these,

Improvac, also marketed as

Innosure and produced by Zoetis for use in pigs, stands out with an efficacy duration of eight to twelve weeks. This vaccine consists of a synthetic GnRH analog with an aqueous adjuvant [

23]. Another key product is

Bopriva, also from Zoetis, intended for cattle, containing a modified GnRH peptide in an aqueous adjuvant specific to livestock, with an efficacy duration of approximately fifteen weeks [

21]. All vaccines must be administered subcutaneously, which presents handling challenges in intensive production systems where numerous animals must be inoculated in a short time while ensuring operator safety and avoiding accidental self-inoculation. Therefore, there is a need for an alternative that facilitates administration, such as the formulation of an oral vaccine.

Oral vaccines offer several advantages over conventional injectable vaccines: they are easy to administer, safe to handle (since they do not require needles), suitable for mass immunization, stable without refrigeration (if lyophilized), and have relatively low production costs [

24,

25]. In this way, oral vaccines meet the criteria for an ideal vaccine which includes no use of syringes, no need for a cold chain for distribution, and the application of a single dose to exert its effect. Vaccines using attenuated live strains of

Salmonella as vectors, meet these requirements [

26]

Oral administration of

Salmonella results in colonization of Peyer's patches through M cells in the intestinal tract of mammals, and colonization of mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, and spleen, resulting in both local and systemic humoral and cellular immune responses[

27,

28] ). To interact with the host,

Salmonella has developed a strategic mechanism involving specialized macromolecular organelles called type III secretion systems (TTSS), whose central function is the translocation of bacterial proteins into eukaryotic cells. This system mediates the transfer of bacterial effector proteins capable of modulating cellular functions in the host cell [

29]

Salmonella enterica encodes two TTSS, located on different pathogenicity islands: one is found in pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1) and is responsible for the initial interaction of the bacteria with intestinal epithelial cells, inducing actin cytoskeleton reorganization and internalization of

S. enterica; the other TTSS is located in pathogenicity island 2 (SPI2) and allows the intracellular survival and replication of the bacteria required to produce a successful systemic infection [

29]. For these bacteria to be used as oral vaccine vectors, it is necessary to significantly reduce their virulence through various attenuation methods [

30,

31]. Thus, mutations in SPI2 result in significant attenuation of

Salmonella virulence and a defect in its ability to cause systemic infection due to its inability to survive within macrophages [

29].

Attenuated strains of

Salmonella expressing heterologous antigens offer a valuable alternative to conventional vaccines, as they induce effective adaptive humoral, cellular, and mucosal immune responses, as demonstrated in various animal models, including rats, mice, rabbits, and pigs [

24,

26,

32] and even in human volunteers [

33]. Moreover, the existence of the Ty21a vaccine, developed with live attenuated

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, against typhoid fever, which has been approved by the United States FDA for human use, serves as an important safety benchmark for future research in this area [

34] Furthermore,

Salmonella has been shown to be useful for delivering DNA vaccines, where the attenuated bacteria carry a plasmid encoding eukaryotic antigens, which, although not expressed in the bacteria, can be delivered to the host macrophage, resulting in the expression and presentation of the antigen by the host's immune system very efficiently [

32,

35].

In this work, the concept of oral immunization against GnRH was tested in a murine model. An attenuated S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain lacking SPI2 (S. Typhimurium ΔSPI2), carrying the recombinant GnRXG/Q antigen, was used as a vector, under two different formulations: one as a constitutive producer of the recombinant antigen and the other as a carrier of the GnRXG/Q gene under a eukaryotic replication system. The proof of concept for these two formulations was conducted by evaluating the adaptive immune response generated in male mice by measuring antibodies against the antigen, testosterone levels, and testicular changes after oral administration of two doses of the formulation. Although still largely in the experimental stage, the use of oral vaccines for immunocastration could represent a breakthrough in animal welfare, providing a humane, cost-effective, and efficient alternative to surgical castration and injectable immunocastration. This study provided relevant data on adaptive immunity against GnRH under an oral immunization scheme. Moreover, the efficacy and safety of this proof of concept allow for the projection of these results toward future preclinical trials.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at the Veterinary Biotechnology Center, Biovetec, Faculty of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, University of Chile.

Intracellular Survival Assay of S. Typhimurium in Murine Macrophages RAW264.7

An intracellular survival assay in macrophages was performed to verify vector attenuation. The assay was based on the one described by[

36]. RAW264.7 cells (provided by Dr. Gonzalo Cabrera, Faculty of Medicine, University of Chile) were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO

2 in RPMI medium enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% L-glutamine, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% streptomycin and penicillin. The cells were transferred to 24-well culture plates until reaching 80% confluence. For the assay, the wild-type

S. Typhimurium 14028s strain (from Dr. Stanley Maloy’s strain collection, University of San Diego, California) was used as the control, and the mutant strain

S. TyphimuriumΔSPI2/pJEX was grown in LB-broth under anaerobic conditions at 37°C until an OD600 of 0.2 units was reached. A total of 200 µL of this culture was centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was discarded. The bacterial sediment was resuspended in 1 mL of enriched RPMI. Next, 50 µL of the bacterial suspension was added to each well, aiming for a multiplicity of infection of 50 bacteria per cell. Nine wells with cell monolayers were used for each bacterial strain. The culture plate was incubated in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere at 37°C for 1 hour to allow bacterial entry into the cells (invasion). Immediately afterward, the monolayers were washed twice with sterile PBS, and 100 µL of enriched RPMI supplemented with 200 µg/mL gentamicin was added to each well. The plate was incubated for 2 hours to eliminate extracellular bacteria. The medium was removed, and the monolayers were washed twice with sterile PBS. Three wells were treated with 0.5% sodium deoxycholate in sterile PBS to lyse the cells. The number of intracellular bacteria (CFU at t

0) was determined by serial dilution and seeding of the cell lysate on LB agar plates. For the remaining six wells of each bacterial strain, fresh RPMI medium with 25 µg/mL gentamicin was added, and the plates were incubated for 24 and 48 hours to allow intracellular proliferation. The monolayers were lysed, and the recovered bacteria (CFU at t

24-48h) were counted. The survival percentage of each strain was calculated using the following equation:

Antigen Expression and Detection via Western Blot Analysis

To demonstrate the expression of the GnRXG/Q antigen in the recombinant strain S. Typhimurium ΔSPI2/pJEX (prokaryotic expression plasmid), a Western blot analysis was performed using the purified GnRXG/Q antigen as a positive control. An isolated colony of the recombinant strain S. Typhimurium ΔSPI2/pJEX was cultured in 10 mL of LB broth and incubated with vigorous shaking for 18 hours at 37°C. The bacteria was then reinoculated into 90 mL of LB broth and incubated at 37°C until an OD600> 0.6 was reached. Once the optical density was achieved, 1 mM IPTG was added to induce protein synthesis, and the culture was incubated at 37°C with shaking for 18 hours. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 x g for 15 minutes at 20°C, resuspended in binding buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 M NaCl2, 40 mM imidazole, pH 7.4) (4 mL per gram of pellet), and lysed by sonication for 8 cycles of 15 seconds with 15-second intervals, at an amplitude of 40%. The cells were then centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 10 minutes at 20°C and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mM EDTA) with urea (2 mL per gram of pellet).

The bacterial whole cell extracts, equivalent to 30 µg of protein,were subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis on 10% acrylamide gels at 150 V for 1 hour. Subsequently, the gel was wet transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for 30 minutes at 250 mA. After the transfer, the membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in 1X PBS, for 18 hours at room temperature. The membrane were incubated with primary antibody against GnRXG/Q antigen before washing twice with TBST (1X TBS, 0.05% Tween 20) and incubate with anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated to peroxidase enzyme (Jackson Immunoresearch™) diluted in ELISA buffer (1X PBS, 3% BSA). The membrane was washed five times with TBST and developed with the development buffer (5 mL phosphatase buffer, 33 µL BCIP, 16.5 µL NBT). Once the color developed, the membrane was washed with distilled water, and the band was photographed under a transilluminator.

Preparation of Inoculum for Immunization

The bacterial strains

S. Typhimurium 14028s ΔSPI2/pJEX and

S. Typhimurium 14028s ΔSPI2/pDNAX3 were cultured in 10 mL of LB broth with 50 µg/mL kanamycin and 10 mL of LB broth with 100 µg/mL ampicillin, respectively, for 18 hours at 37°C. They were then reinoculated into 90 mL of LB broth with 50 µg/mL kanamycin and 90 mL of LB broth with 100 µg/mL ampicillin, respectively, and incubated at 37°C to an OD

600 of 0.6-1.0. The

S. Typhimurium 14028s ΔSPI2/pJEX culture was induced with 1 mM IPTG at 37°C with shaking for 18 hours. The cultures were serially diluted in LB broth to reach a concentration of 10

9 CFU per inoculum. They were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 10,000 x g, and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in 4 parts PBS and 1 part of 7.5% sodium bicarbonate at pH 8.5 in a total volume of 200 µL, before inoculating mice as described by [

37]

Mouse Immunization

Twelve male BALB/c mice were housed in the animal maintenance unit at Biovetec laboratory, feed ad libitum with food and water, in a controlled environment (23±1°C, indirect light 12h on/12h off). The animals were housed in specially designed polycarbonate cages equipped with stainless steel tops containing feeders and water bottles. Care was taken to ensure adequate space and ventilation for each animal. The feeding, hydration, and cleaning of the mice were supervised daily as part of this research project.

The animals were randomly divided into four experimental groups, each consisting of three mice. Group A was orally inoculated with 109 CFU of the live attenuated bacterial strain S. Typhimurium 14028s ΔSPI2/pJEX, which expressed the GnRXG/Q antigen. Group B was orally inoculated with 109 CFU of the live attenuated bacterial strain S. Typhimurium 14028s ΔSPI2/pDNAX3, which carried the GnRXG/Q gene. Group C served as the positive control and was subcutaneously inoculated with 100 µg of affinity-purified GnRXG/Q protein, plus aluminum as an adjuvant. Group D received 200 µL of PBS orally and served as the negative control. The mice were fasted for 4 hours before immunization. The inoculum was administered orally using a plastic pipette. A booster was administered to all groups 30 days after the first immunization.

Blood samples (200 µL) were collected from the external saphenous vein on days 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 post-inoculation. Blood samples were collected, allowed to coagulate at room temperature, and stored at 4°C overnight before being centrifuged at 2,500 x g for 20 minutes at 4°C. The resulting sera were collected and stored at -20°C until use.

The clinical trials with mice were monitored to evaluate any potential side effects that could compromise the welfare of the experimental animals. The initial reference for clinical trial monitoring was based on the guidelines for choosing endpoint criteria for experimental animals as described by the Canadian Council on Animal Care [

38].

Measurement of Antibody Levels Against GnRXG/Q

The IgG anti-GnRXG/Q antibody titers were determined by ELISA using the following protocol: ELISA plates (96 wells) were coated with the GnRXG/Q antigen diluted in Coating Buffer (0.15 M Na2CO3 - 0.35 M NaHCO3, pH 9.6). A total of 50 µL of the diluted antigen was added to each well, except for the controls. The plates were incubated for 18 hours at 4°C without shaking. The solution was then removed, and the wells were washed twice with 200 µL of Washing Buffer (1X PBS and 0.02% Triton 100X). To block nonspecific binding sites, 200 µL of Blocking Buffer (5% skimmed milk diluted in Washing Buffer) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 18 hours at 4°C without shaking. The solution was then removed, and the plates were washed twice with 200 µL of Washing Buffer per well. For the antigen-antibody reaction, 100 µL of mouse serum diluted 1:250 in ELISA Diluent Buffer (0.5% skimmed milk plus Washing Buffer) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C without shaking. The plates were then washed five times with Washing Buffer. To detect the antigen-antibody complex, 100 µL of anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated to peroxidase (Jackson Immunoresearch) diluted 1:5000 in ELISA Diluent Buffer was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C without shaking. Finally, the plates were washed five times with 200 µL of Washing Buffer per well. The reaction was detected by adding 100 µL of Tetramethylbenzidine TMB-ELISA substrate solution to each well, and the plates were incubated for an additional 10 minutes at 37°C without shaking. The reaction was stopped with 100 µL of Stop Solution (1.5 M H2SO4 in deionized water at room temperature). The absorbance was read at 450 nm in an ELISA microplate reader (Bio-rad Laboratories, Inc.). All samples were analyzed in duplicate. The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of absorbances measured at 450 nm.

Measurement of Serum Testosterone Levels

The quantitative determination of testosterone in the serum samples obtained from the study animals was performed using the commercial ELISA kit for testosterone (IBL-America, Inc.). The reagents included in the kit were allowed to reach room temperature before starting the assay. The washing solution was prepared with deionized water according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

A total of 25 µL of each sample was dispensed into each well, in parallel with the standard and control reagents provided with the kit. Then, 200 µL of the enzyme-conjugated reagent was added to each well and mixed for 10 seconds. The plate was incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature, after which the wells were emptied, and the unbound conjugate was removed by washing the plates three times with 400 µL of Washing Buffer per well.

For the development reaction, 200 µL of substrate solution was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature. The enzymatic reaction was stopped by adding 100 µL of Stop Solution to each well. The absorbance was read at 450 nm in an ELISA microplate reader (Bio-rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Histological Evaluation of Testes

The mice were euthanized by CO2 exposure after the last blood samples were collected. Testicles were extracted and fixed in 10% formalin. In the facilities of the Pathology Department of the Faculty of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, University of Chile, the testes were sectioned at 5 µm thickness, stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin, and analyzed by optical microscopy to observe the transverse tubular diameter of the seminiferous tubules and the number of cell layers. The transverse tubular diameter corresponds to the average of two measurements taken diametrically opposed.

Statistical Analysis

To analyze the data obtained, one- and two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using GraphPad Prism software. The sample means of antibody and testosterone levels between the two vaccine formulations under study and the positive and negative control groups were compared, as well as the transverse tubular diameters of the seminiferous tubules and the number of seminiferous epithelial layers in both testicles of the mice. Immunization was considered effective if there were statistically significant differences with the control groups. The statistical analyses of the survival assays were similarly performed using GraphPad Prism software®, with Student's t-test used to analyze significant differences between the mutant strains and the wild-type strain.

Results.1 Intracellular Survival Assay of S. Typhimurium in Murine Macrophages RAW264.7

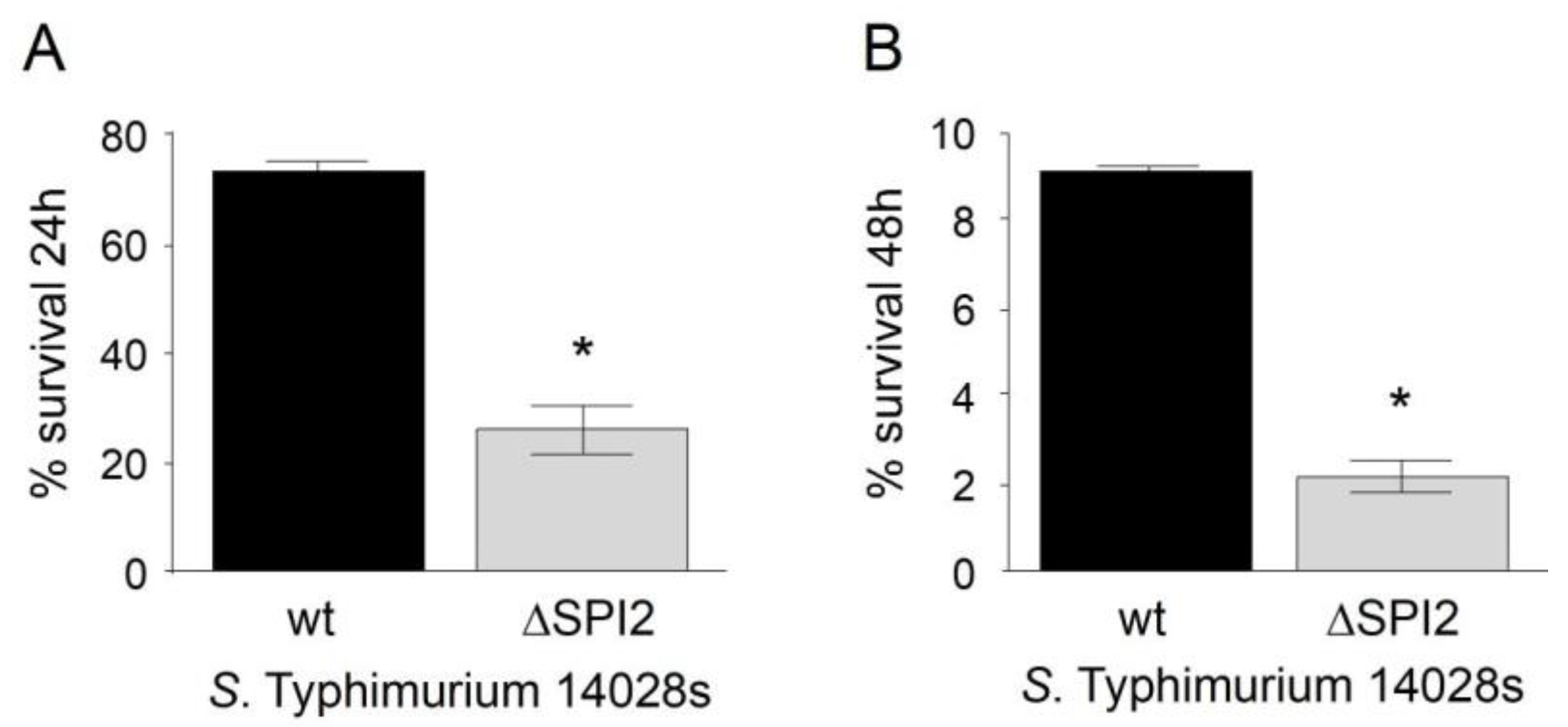

An in vitro assay was conducted to evaluate the survival of S. Typhimurium 14028s ∆SPI2 and verify the attenuation of its virulence, as this pathogenicity island is required for the intracellular survival and replication of the bacteria necessary to cause systemic infection. Mutations in SPI2 result in a significant attenuation of Salmonella virulence and impair its ability to produce systemic infection due to its inability to survive within macrophages (Galán, 2001). As shown in

Figure 1, the survival of S. Typhimurium 14028s ∆SPI2 within murine RAW264.7 macrophages was significantly reduced at 24 and 48 hours postinfection, compared to the wild-type S. Typhimurium 14028 strain.

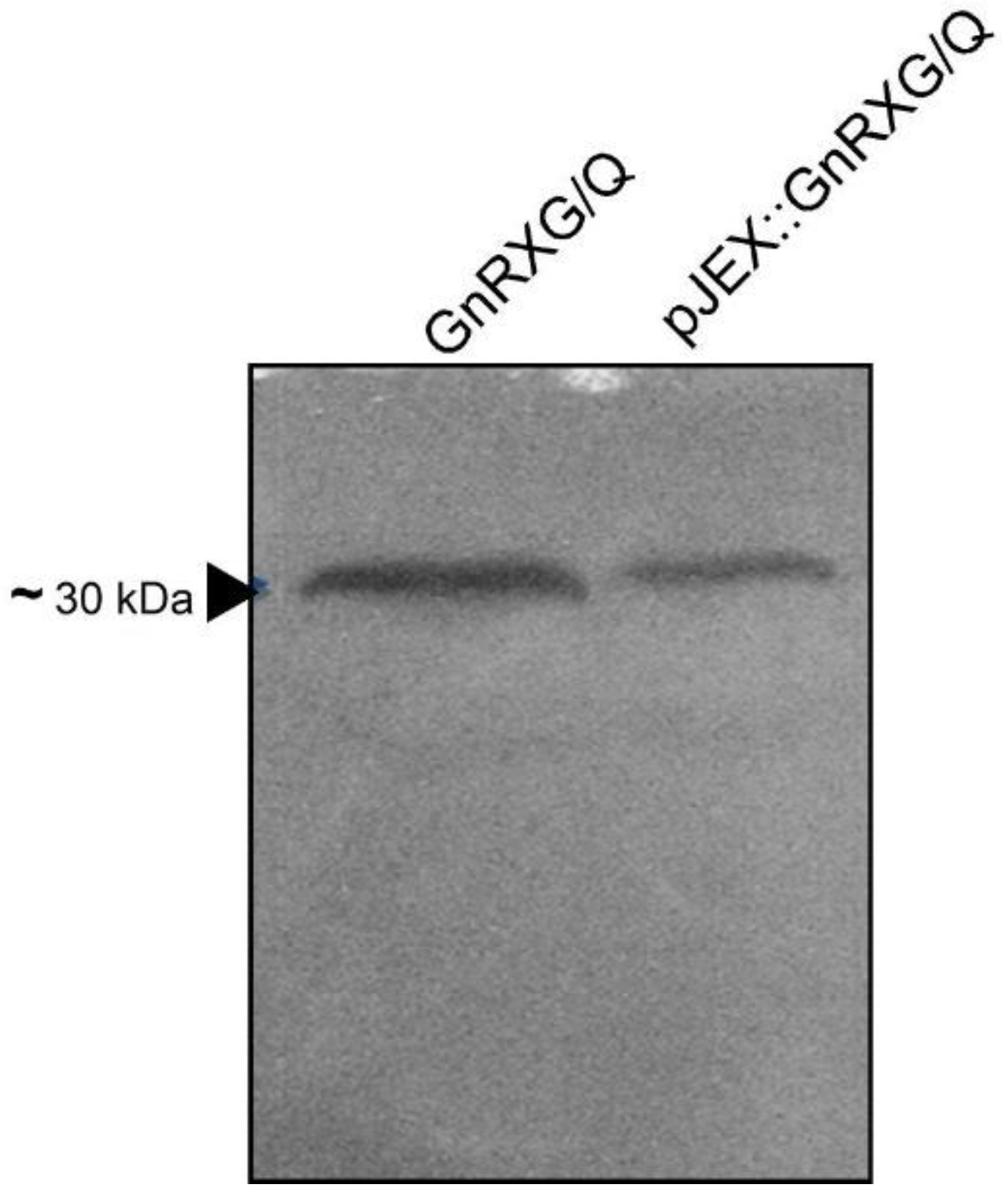

Antigen Expression Detection via Western Blot Analysis

To detect the expression of the GnRXG/Q antigen in the recombinant strain S. Typhimurium 14028s ∆SPI2/pJEX, a Western blot analysis was performed. This technique relies on the recognition of proteins separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, by specific antibodies after their transfer into nitrocellulose membranes.

Figure 2 shows the correspondence of the GnRXG/Q antigen with the protein detected in the analysis.

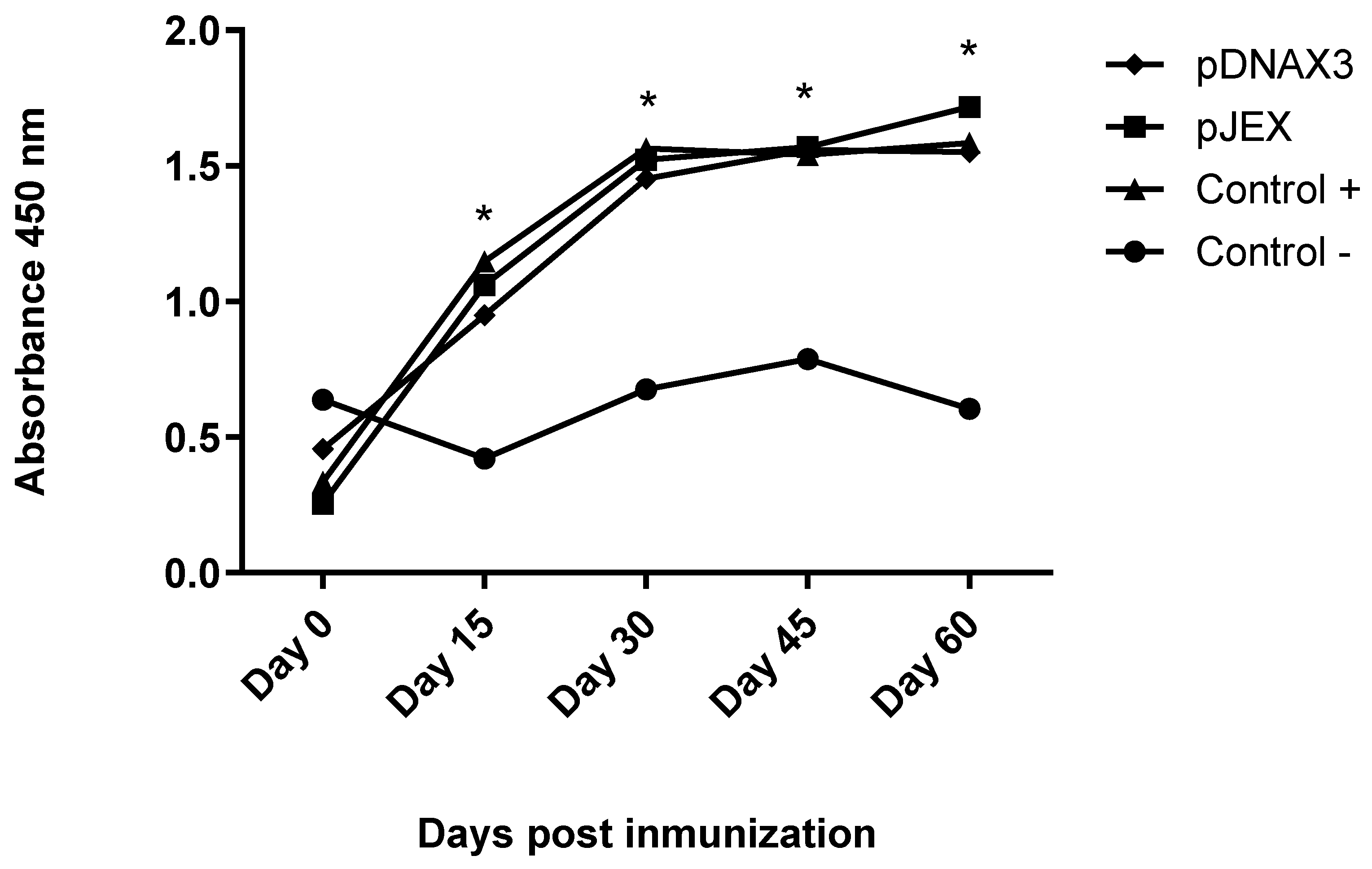

Measurement of Antibody Levels Against GnRXG/Q

IgG anti-GnRXG/Q antibody titers were determined by an ELISA assay using the GnRXG/Q protein in 96-well ELISA plates. The antigen-antibody complex was detected using anti-mouse IgG conjugated to peroxidase (Jackson Immunoresearch). The groups vaccinated with strain S. Typhimurium 14028s ∆SPI2/pJEX, S. Typhimurium 14028s∆SPI2/pDNAX3, and the positive control group showed a significant increase in antibody levels on days 15, 30, 45, and 60 post-immunization compared to the negative control group. Additionally, no significant differences were observed between the first three groups (

Figure 3).

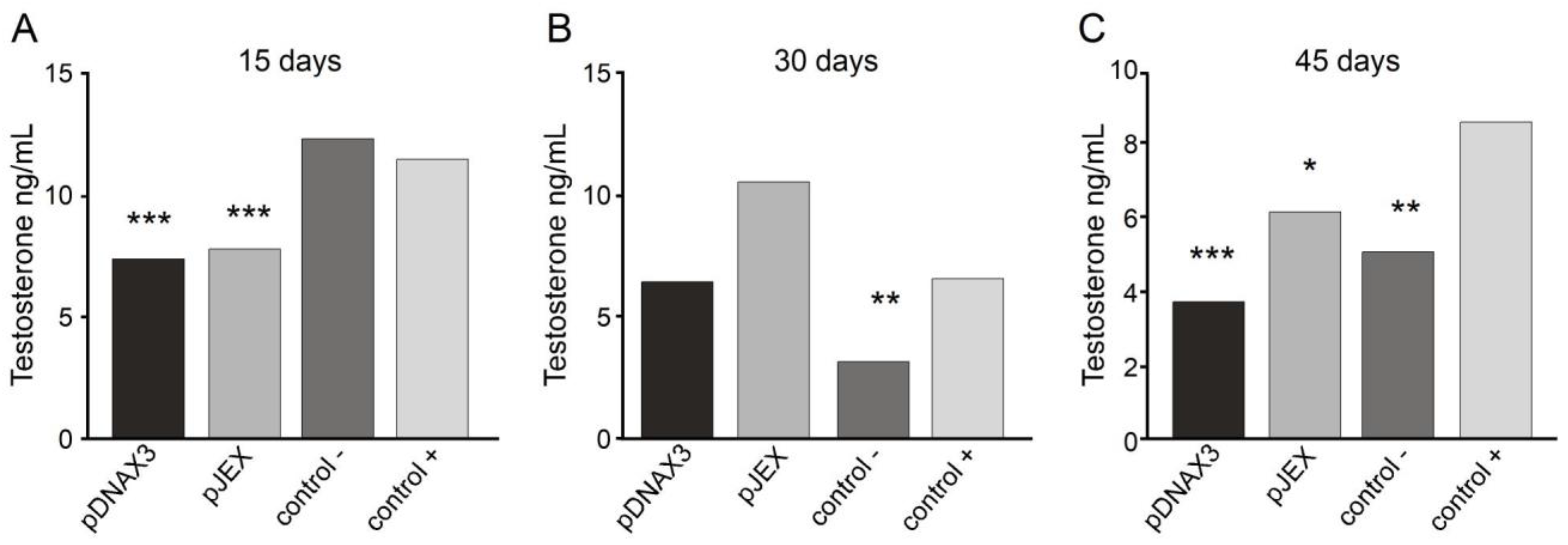

Measurement of Serum Testosterone Levels

Testosterone concentration in the serum of the study animals was measured using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit for testosterone (IBL-AMERICA) on days 15, 30, and 45 post-immunization. This solid-phase immunoassay is based on the principle of competitive binding, where an unknown amount of antigen in the samples competes with a fixed amount of enzyme-labeled antigen for the antibody binding sites. The wells were coated with a monoclonal antibody directed against a testosterone epitope, allowing the hormone in the serum samples to compete with a testosterone–peroxidase conjugate for binding to the immobilized antibody. After obtaining the absorbance of the known concentration standards and the serum samples, a standard curve was constructed with the mean absorbance of each standard and its concentration. The concentration for each sample was then determined using the standard curve, as presented in

Figure 4.

Serum testosterone levels measured on day 15 post-immunization (

Figure 4A) showed a significant decrease in both experimental groups compared to the negative control group. However, no differences were observed compared with the positive control group. On day 30 (

Figure 4B), only the positive control group showed a significant decrease compared to the negative control group, with no differences in the experimental groups. However, on day 45 (

Figure 4C), both experimental groups and the positive control group showed a significant reduction in serum testosterone levels compared with the negative control group.

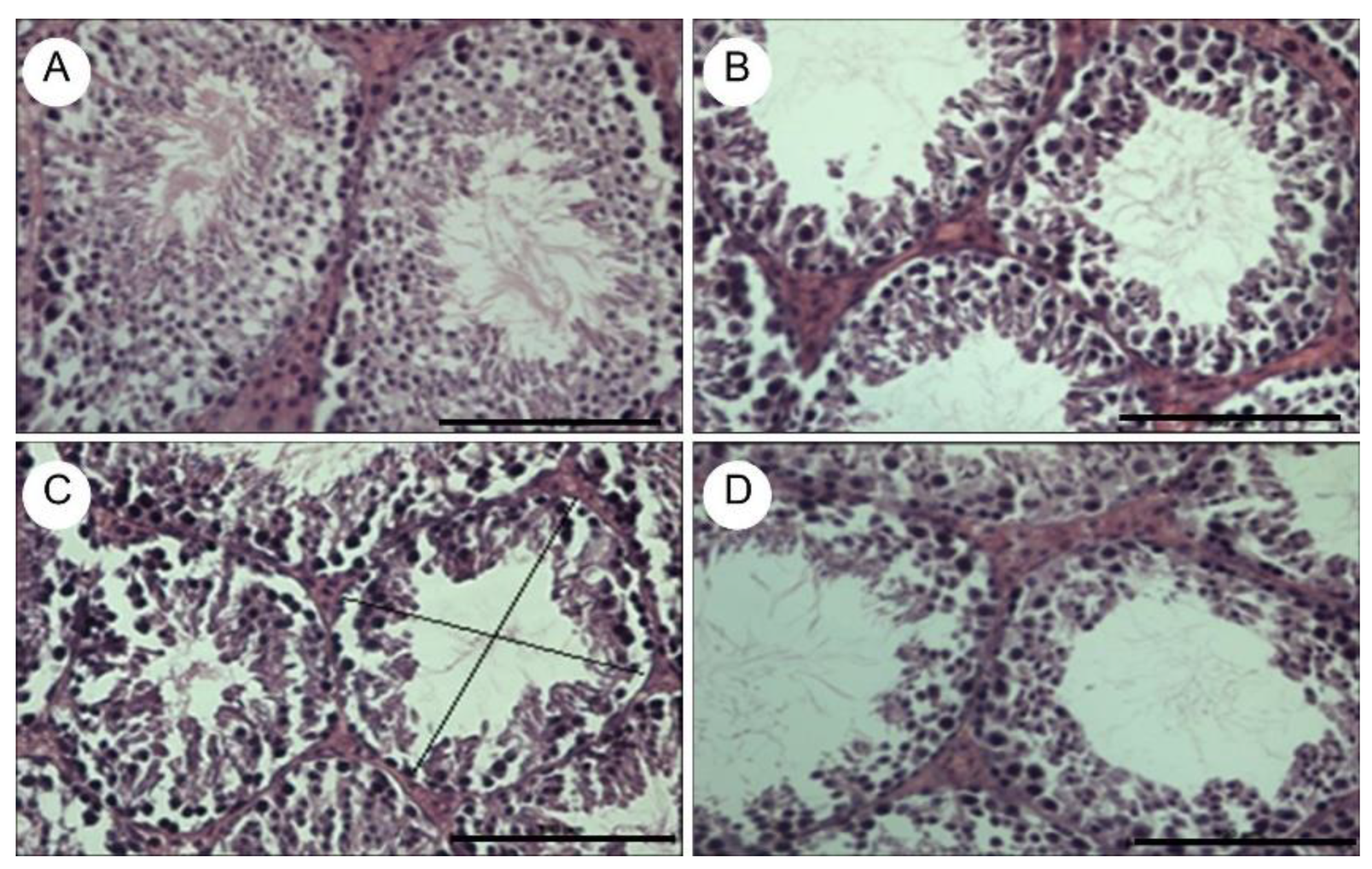

Histological Testicular Evaluation

The testes of the mice were extracted and fixed in 10% formalin, then sectioned at 5 µm thickness, stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin, and analyzed by optical microscopy. The images were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse E400 optical microscope and Image-Pro Plus morphometric software. To demonstrate testicular tissue atrophy, the transverse tubular diameter of 10 seminiferous tubules and the number of epithelial cell layers in 10 seminiferous tubules were measured in each group (

Table 1). Testicular tissue from the negative control group showed no signs of atrophy (

Figure 5a). The experimental groups and the positive control group exhibited a significant reduction in the transverse tubular diameter of the seminiferous tubules, as well as a significant decrease in the number of seminiferous epithelial cell layers (

Table 1 and

Figure 5b–d).

4. Discussion

Previous studies have developed various strategies to induce an effective and safe immune response against GnRH in different animal species, with varying results. However, oral immunization had not been explored before. Oral vaccine formulations offers several advantages, such as ease of administration, safety since no needles are required, and relatively low production costs [

24,

39]

In this work, attenuated S. Typhimurium was used as an antigenic vector, which proved to be safe for animals due to deletional SPI2 mutation. SPI2 is responsible for survival within macrophages, while maintaining an intact SPI1, which preserves its invasive capacity to deliver heterologous genes into mammalian cells. Thus, this vector can be used for the development of oral vaccines, facilitating animal management and vaccine administration.

Attenuated

Salmonella Typhimurium was conjugated with two plasmids containing a tandem-repeated of modified GnRH gene (

GnRXG/Q), one for prokaryotic expression (

pJEX) and one for eukaryotic expression (

pDNAX3). Both groups showed a significant increase in IgG anti-

GnRXG/Q antibody levels, similar to the increase observed in the positive control group inoculated subcutaneously, compared with the negative control group. This confirms the effectiveness of

Salmonella as a vector for producing an effective humoral immune response, as previously demonstrated [

24,

24,

40]

Regarding testosterone levels, they significantly decreased on day 15 post-immunization in both experimental groups but increased on day 30. After the booster was applied, testosterone levels significantly decreased again on day 45 in both groups. This increase on day 30 could be attributed to the positive feedback that the decrease in serum testosterone has on the secretion of GnRH by the hypothalamus, which stimulates the increased secretion of this decapeptide, inducing the release of LH from the anterior pituitary, which in turn stimulates Leydig cells in the testes to produce more testosterone [

41]( The booster applied on day 30 neutralized GnRH once again, significantly reducing testosterone levels by day 45. It is necessary to evaluate the application of a booster before day 30 post-immunization to test if serum testosterone levels remain low.

The experimental groups, as well as the positive control, exhibited atrophy of the seminiferous epithelium, with a significant reduction in the transverse tubular diameter of the seminiferous tubules and in the number of epithelial cell layers, compared to the negative control group, which is consistent with the decrease in serum testosterone. This implies that fertility should be considerably reduced, as the success of spermatogenesis depends on testosterone levels and the maintenance of seminiferous tubule morphology. A decrease in transverse tubular diameter causes a reduction in the number of Sertoli cells, which support the epithelium and secrete androgen-binding protein, concentrating testosterone inside the seminiferous tubule and allowing the maintenance of normal spermatogenesis. Thus, the reduction in these cell types leads to spermatogenesis alterations and subsequent subfertility [

42,

43]. However, fertility studies are needed to confirm effectiveness.

The results demonstrate that oral induction of antibodies against a GnRH analogue leads to decreased testosterone synthesis and subsequent seminiferous epithelium atrophy in male mice, as previously demonstrated through parenteral inoculation [

1,

5,

44,

45].

Moreover, it is shown that S. Typhimurium ΔSPI2 is a feasible, safe, and simple system to produce an oral immunological preparation against GnRH, and that oral antigen delivery mediated by Salmonella is a novel alternative to efficiently induce an immune response against GnRH in a mouse model, which deserves further investigation in other animal species.

The findings might have a great impact on veterinary medicine, as it would provide the same benefits as surgical castration and injectable immunocastration, but at a lower economic cost and with a significant contribution to animal welfare.