Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

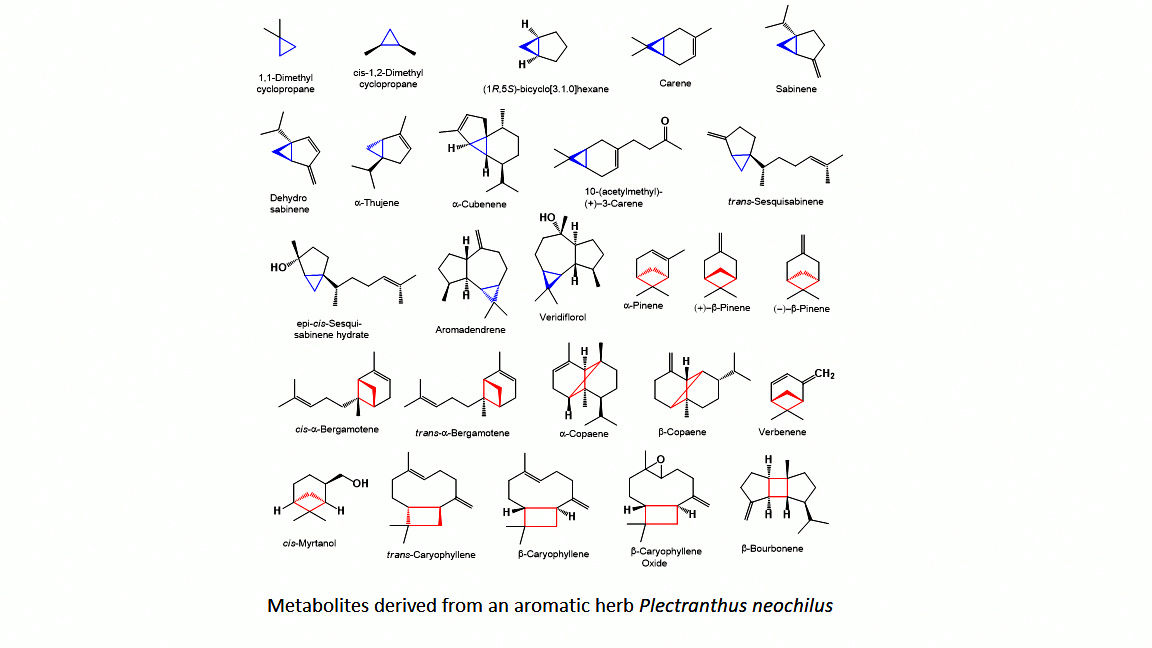

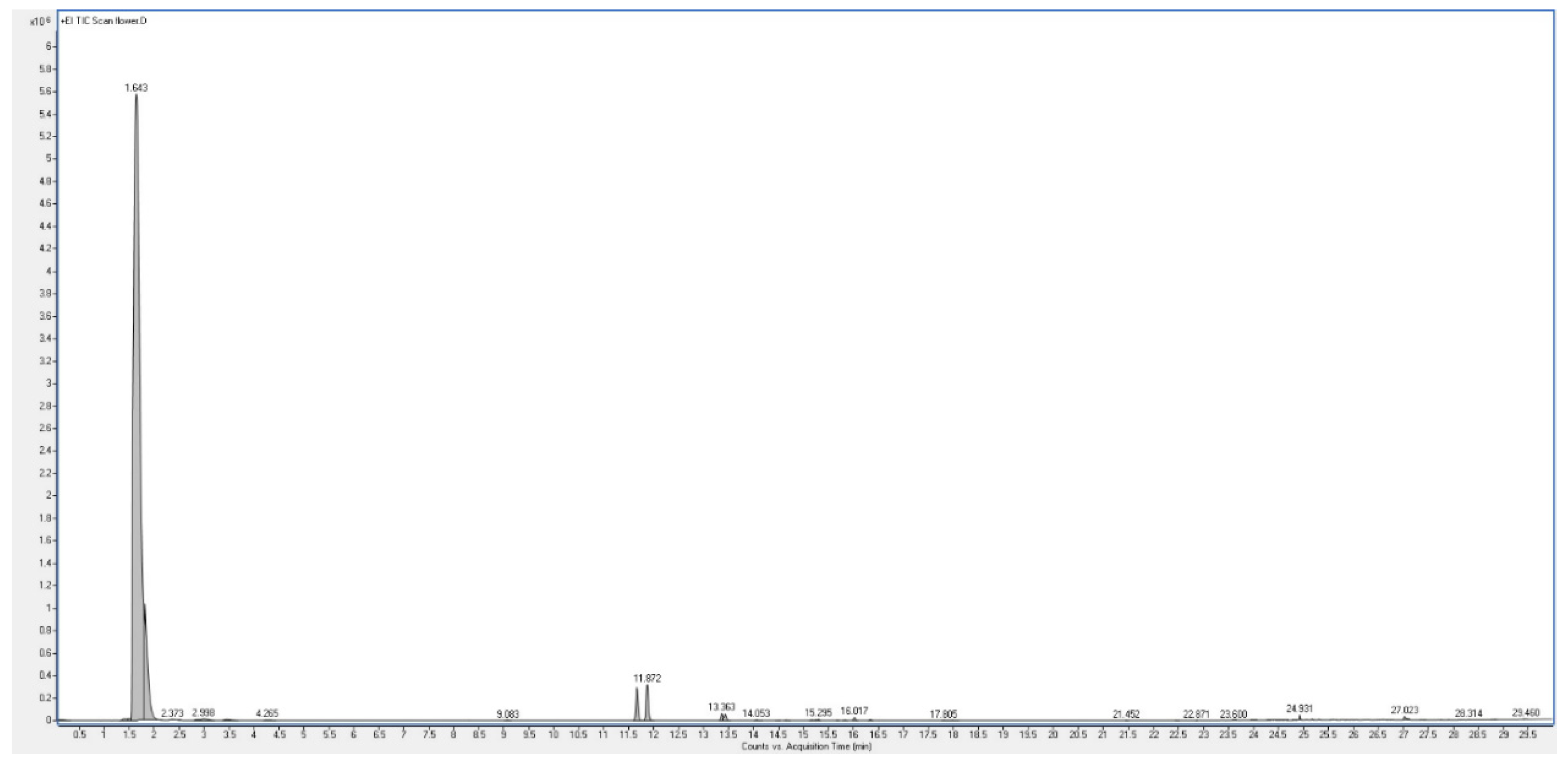

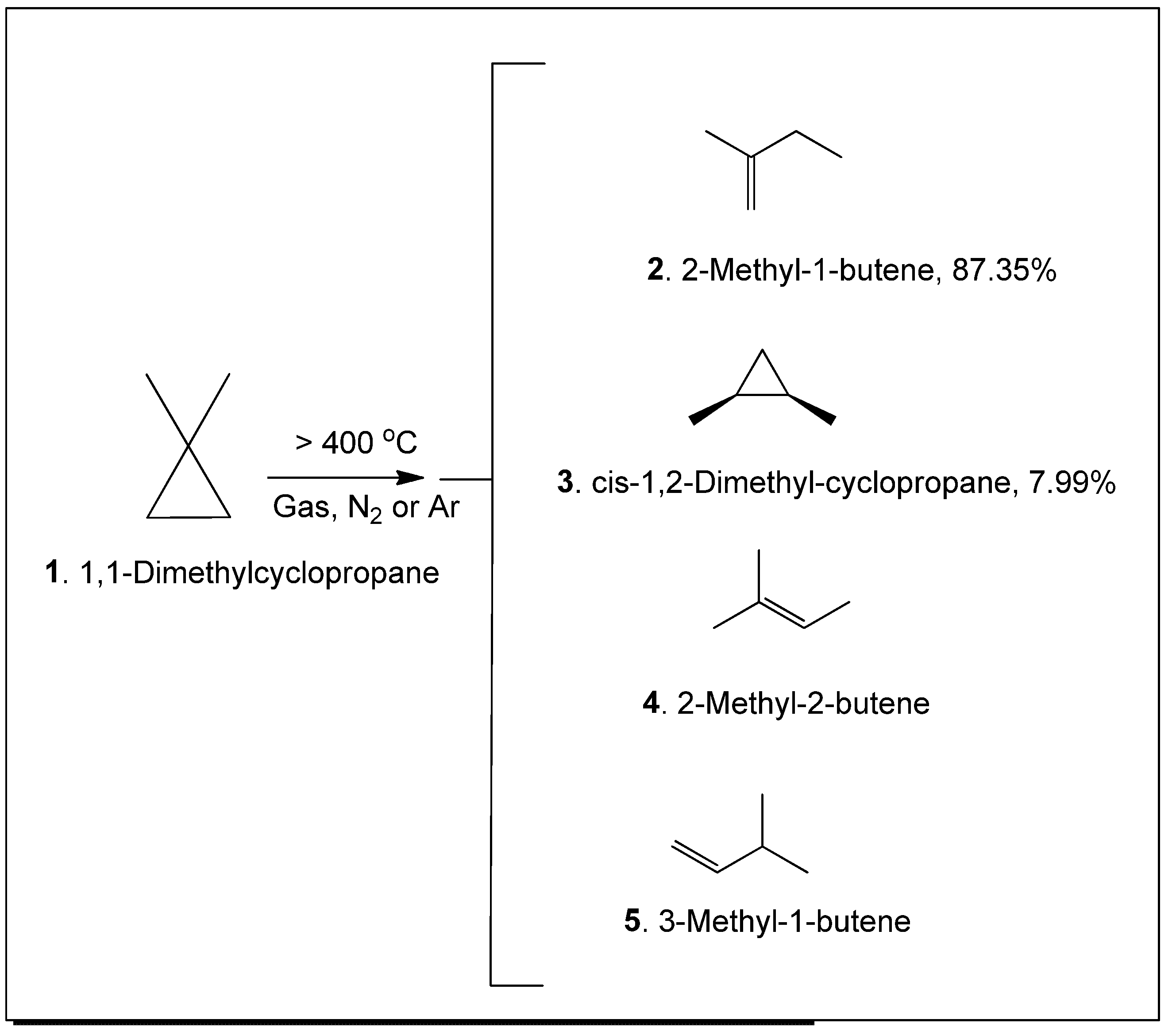

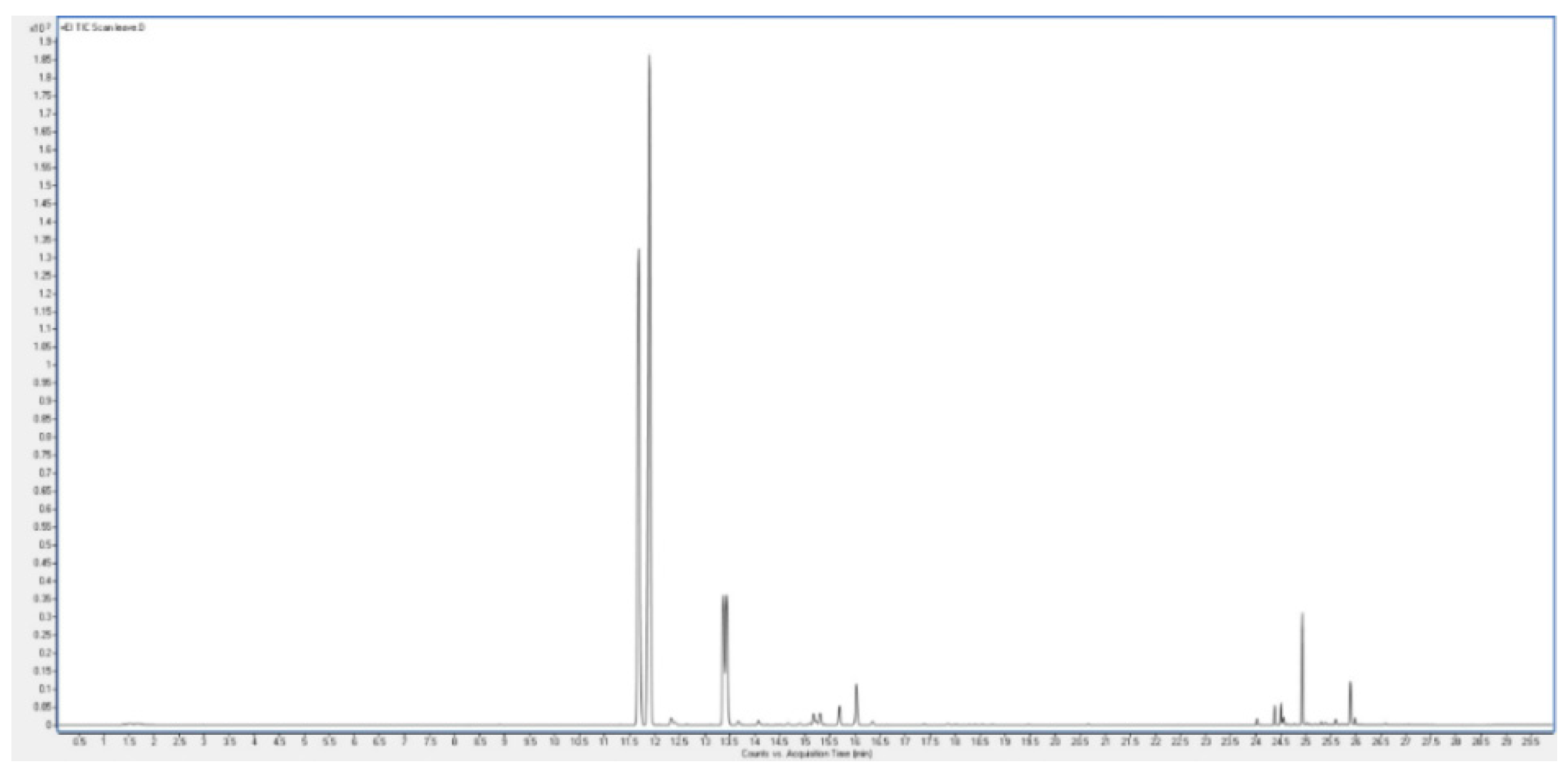

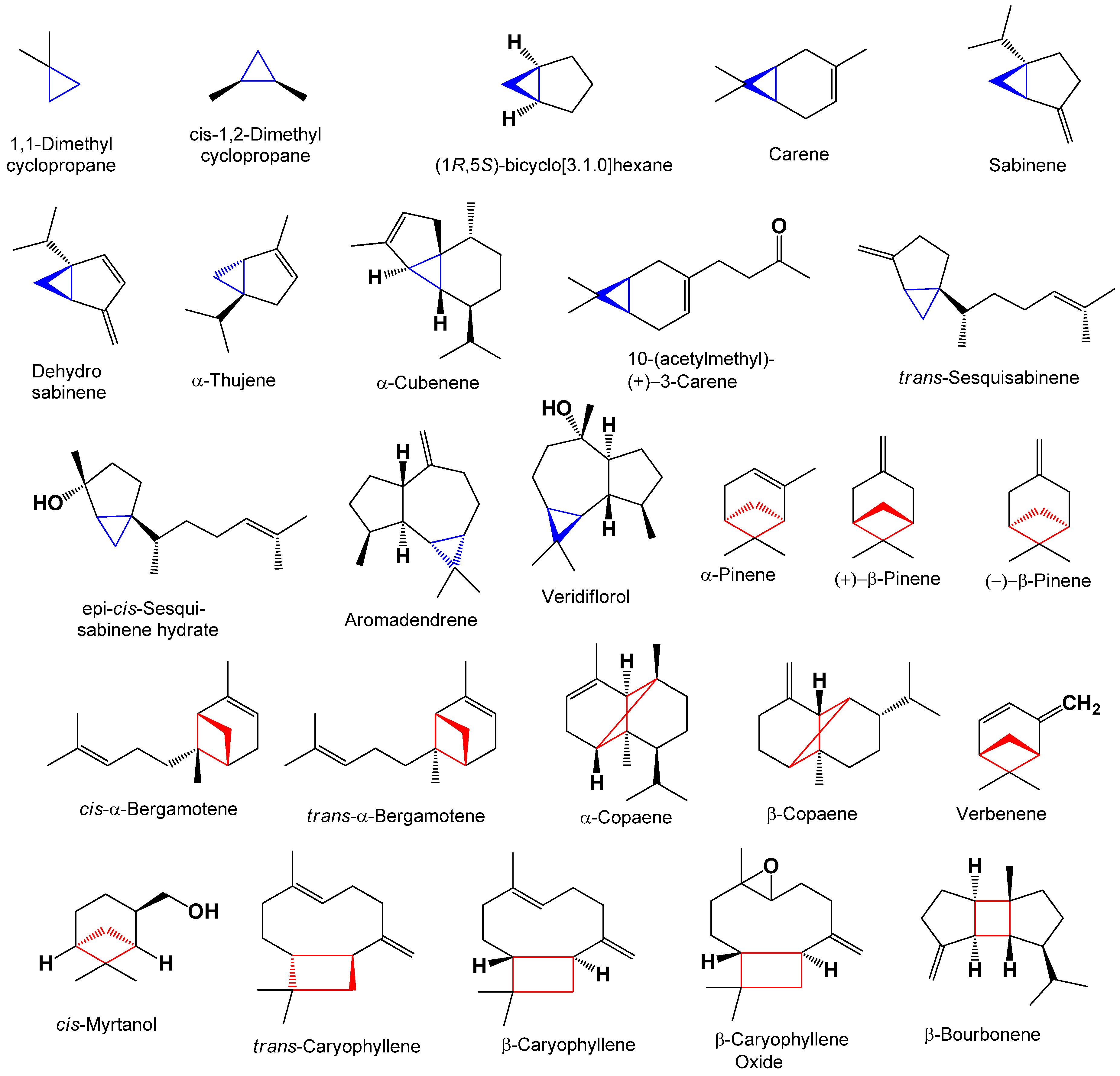

The aromatic herb Plectranthus neochilus with a cannabis smell, widely used in folk medicine, has become the subject of a study of its essential oils of flowers and leaves. GC-MS analysis revealed a unique composition, the oils of flowers, the main component of which is 2-methyl-1-butene, its concentration exceeds 87 percent. On the one hand, this is very unusual data, although, on the other hand, it is known that 2-methyl-1-butene can be a product of thermal decomposition of 1,1-dimethyl-cyclopropane. However from a microbiological point of view, 2-methyl-1-butene can be a product of bacterial reduction of isoprene by a mixture of Comamonas sp. and Acetobacterium wieringae bacteria. This issue is extremely interesting and requires further careful study, although a preliminary discussion is given in the discussion of this phenomenon. Analysis of the oil from the leaves showed that the main products are α-thujene and α-pinene, the content of which exceeds 75 percent. According to a detailed analysis of the species Plectranthus, it was found that this species is a producer of volatile metabolites containing cyclopropane and cyclobutane rings. It is assumed that the compounds of essential oils containing cyclopropane and cyclobutane rings may be the main biologically active substances in this species or genus of plants. Data on the biological activity of the main identified compounds of this aromatic plant are presented.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Column

2.5. Standards

2.6. Experimental Conditions for Head Space Analysis

2.7. Identification

3. Results

3.1. Plant Flowers Analysis

3.2. Products of Bacterial Action

3.3. Plant Leaves Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barbosa, M.D.O.; Wilairatana, P.; Leite, G.M.D.L.; Delmondes, G.D.A.; Silva, L.Y.S.D.; Júnior, S.C.A.; Kerntopf Mendonça, M.R. Plectranthus species with anti-inflammatory and analgesic potential: A systematic review on ethnobotanical and pharmacological findings. Molecules 2023, 28, 5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos da Silva, L.R.; Ferreira, O.O.; Cruz, J.N.; de Jesus Pereira Franco, C.; Oliveira dos Anjos, T.; Cascaes, M.M.; Santana de Oliveira, M. Lamiaceae essential oils, phytochemical profile, antioxidant, and biological activities. Evidence-Based Complem. Alternative Med. 2021, 1, 6748052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambrechts, I.A.; Lall, N. Plectranthus neochilus. In Underexplored Medicinal Plants from Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Academic Press, 2020, p. 235.

- Pereira, M.; Matias, D.; Pereira, F.; Reis, C.P. , Simões, M.F., Rijo, P. Antimicrobial screening of Plectranthus madagascariensis and P. neochilus extracts. Biomed. Biopharm. Res. 2015, 12, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Mota, L.; Figueiredo, A.C.; Pedro, L.G.; Barroso, J.G.; Miguel, M.G.; Faleiro, M.L.; Ascensao, L. Volatile-oils composition, and bioactivity of the essential oils of Plectranthus barbatus, P. neochilus, and P. ornatus grown in Portugal. Chem. Biodiver. 2014, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, G.A.; Ferreira, J.F.; Elias, S.T.; Guerra, E.N.S.; Simeoni, L.A. Cytotoxic effect of Plectranthus neochilus extracts in head and neck carcinoma cell lines. African J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016, 10, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, D.; Nicolai, M.; Fernandes, A.S.; Saraiva, N.; Almeida, J.; Saraiva, L.; Rijo, P. Comparison study of different extracts of Plectranthus madagascariensis, P. neochilus and the rare P. porcatus (Lamiaceae): Chemical characterization, antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caixeta, S.C.; Magalhães, L.G.; de Melo, N.I.; Wakabayashi, K.A.; de, P. Aguiar, G.; de P. Aguiar, D.; Crotti, A.E. Chemical composition and in vitro schistosomicidal activity of the essential oil of Plectranthus neochilus grown in Southeast Brazil. Chem. Biodiver. 2011, 8, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crevelin, E.J.; Caixeta, S.C.; Dias, H.J.; Groppo, M.; Cunha, W.R.; Martins, C.H.G.; Crotti, A.E.M. Antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Plectranthus neochilus against cariogenic bacteria. Evidence-Based Complement. Alternative Med. 2015, 1, 102317. [Google Scholar]

- Lawal, H.; Ado, A.M.; Usman, M.; Garba, U.S. Antihyperlipidemic activity of Plectranthus neochilus leaf ethanolic extract on fat-fed male wistar rats. Int. J. Sci. Global Sustainability 2024, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codd, L.E. South African Labiatae. Bothalia 1961, 7, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirton, C.H. Broad-spectrum pollination of Plectranthus neochilus. Bothalia 1977, 12, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mogib, M.; Albar, H.A.; Batterjee, S.M. Chemistry of the genus Plectranthus. Molecules 2002, 7, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, M.C.; Frey, H.M. The thermal unimolecular isomerization of 1, 1-dimethyl-cyclopropane at low pressures. J. Chem. Soc. 1962, 18, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, M.C. , Frey, H.M. The thermal isomerization of 1, 1-dimethylcyclopropane. J. Chem. Soc. 1959, 26, 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, J.E.; Shukla, R. Thermal isomerizations of 1,1-dimethyl-2, 2-D-2-cyclopropane. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 7821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGenity, T.J.; Crombie, A.T.; Murrell, J.C. Microbial cycling of isoprene, the most abundantly produced biological volatile organic compound on Earth. ISME J. 2018, 12, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, R.A.; Crombie, A.T.; Pichon, P.; Steinke, M.; McGenity, T.J.; Murrell, J.C. The microbiology of isoprene cycling in aquatic ecosystems. Aquatic Microbial Ecol. 2021, 87, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, R.A.; Crombie, A.T.; Jansen, R.S.; Smith, T.J.; Nichol, T.; Murrell, C. Peering down the sink: a review of isoprene metabolism by bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 25, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jin, H.; Li, X.; Yan, J. Biohydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene to 1-butene under acetogenic conditions by Acetobacterium wieringae. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 1637–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrell, J.C.; McGenity, T.J.; Crombie, A.T. Microbial metabolism of isoprene: a much-neglected climate-active gas. Microbiology (Reading) 2020, 166, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronen, M.; Lee, M.; Jones, Z.L.; Manefield, M.J. Reductive metabolism of the important atmospheric gas isoprene by homoacetogens. ISME J. 2019, 13, 1168–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronen, M. Anaerobic microbial metabolism of isoprene (Doctoral Dissertation, UNSW Sydney), 2019.

- Kronen, M.; Vázquez-Campos, X.; Wilkins, M.R.; Lee, M.; Manefield, M.J. Evidence for a putative isoprene reductase in Acetobacterium wieringae. Msystems 2023, 8, e00119-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Cápiro, N.L.; Li, X.; Löffler, F.E.; Yang, Y. Anaerobic biohydrogenation of isoprene by Acetobacterium wieringae strain Y. Mbio 2022, 13, e02086-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Gottschalk, G. Acetobacterium wieringae sp. nov., a new species producing acetic acid from molecular hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Zbl. Bakt. Hyg. I Abt. Orig. C 1982, 3, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.; Crombie, A.T.; McNamara, N.P.; Murrell, J.C. Isoprene-degrading bacteria associated with the phyllosphere of Salix fragilis, a high isoprene-emitting willow of the Northern Hemisphere. Environ Microbiome 2021, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khawand, M.; Crombie, A.T.; Johnston, A.; Vavlline, D.V.; McAuliffe, J.C. Isolation of isoprene degrading bacteria from soils, development of isoA gene probes and identification of the active isoprene-degrading soil community using DNA-stable isotope probing. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 2743–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.R.R.; Correia, Z.A.; Gurgel, E.S.C.; Ribeiro, O.; Silva, S.G.; Ferreira, O.O. Morphoanatomical, histochemical, and essential oil composition of the Plectranthus ornatus Codd.(Lamiaceae). Molecules 2023, 28, 6482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sako, K.B.; Makhafola, T.J.; Antonissen, R.; Pieters, L.; Verschaeve, L.; Elgorashi, E.E. Antioxidant, antimutagenic and antigenotoxic properties of Plectranthus species. South Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 161, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pounina, T.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Savidov, N.; Dembitsky, V.M. Sulfated and sulfur-containing steroids and their pharmacological profile. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtunik-Kulesza, K.A. Toxicity of selected monoterpenes and essential oils rich in these compounds. Molecules 2022, 27, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, C.; Fuentes, A.; Barat, J.M.; Ruiz, M.J. Relevant essential oil components: a mini-review on increasing applications and potential toxicity. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 2021, 31, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, A. Essential oil poisoning. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raguso, R.A. Why do flowers smell? The chemical ecology of fragrance-driven pollination. Adv. Insect Chem. Ecol. 2004, 11, 151–178. [Google Scholar]

- Pichersky, E.; Dudareva, N. Scent engineering: toward the goal of controlling how flowers smell. Trends Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrar, I.; Hervé, M.; Mantel, M.; Bony, A.; Thévenet, M.; Boachon, B.; Mandairon, N. Why do we like so much the smell of roses: the recipe for the perfect flower. iScience 2024, 1, 111635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainstein, A.; Lewinsohn, E.; Pichersky, E.; Weiss, D. Floral fragrance. New inroads into an old commodity. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 1383–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, J.T.; Gershenzon, J. The chemical diversity of floral scent. Biol. Plant Volatiles 2020, 1, 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, H.S.; Park, J.Y.; Park, S.Y. Isolation of off-flavors and odors from tuna fish oil using supercritical carbon dioxide. Biotechnol. Bioproc. E 2006, 11, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, B.; Durance, T. Headspace volatiles of sockeye and pink salmon as affected by retort process. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colibaba, C.; Lacureanu, G.; Cotea, V.V.; Tudose-Sandu-Ville, S.; Nechita, B. Identification of Tamaioasa Romaneasca and Busuioaca de Bohotin wines’ aromatic compounds from Pietroasa vineyard. Bull. UASVM Horticulture 2009, 66, 309–314. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, H.; Fujita, A.; Steinhaus, M.; Takahisa, E.; Watanabe, H.; Schieberle, P. Identification of novel aroma-active thiols in pan-roasted white sesame seeds. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 7368–7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, H. Identification of new key aroma compounds in roasted sesame seeds with emphasis on sulfur components. Doctoral Dissertation, Technische Universität München, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, M.; Singh, R. Volatile self-inhibitor of spore germination in pathogenic Mucorale Rhizopus arrhizus. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladeiras, D.; Monteiro, C.M.; Pereira, F.; Reis, C.P.; Afonso, C.A.M.; Rijo, P. Reactivity of diterpenoid quinones: Royleanones. Curr. Pharm. Design 2016, 22, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, A.N.; Yaser, S.M.; Idhris, S.M.; Padusha, M.S.A.; Sherif, N.A. Phytochemical and pharmacological potential of the genus Plectranthus - A review. South Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 154, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forzato, C.; Nitti, P. New diterpenes with potential antitumoral activity isolated from plants in the years 2017–2022. Plants 2022, 11, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, L.S.F.; Matos, T.S.; do Nascimento Ávila, F.; da Silva Batista, A.; Moura, A.F.; de Moraes, M.O.; da Silva, M.C.M.; Ferreira, T.L.A.; Nascimento, N.R.F.; Monteiro, N.K.V.; Pessoa, O.D.L. Diterpenoids from leaves of cultivated Plectranthus ornatus. Planta Med. 2021, 87, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, M. Rhodococcus globerulus colonizing the medicinal plant Plectranthus. Int. J. Cur. Res. Rev. 2017, 9, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Murugappan, R.M.; Benazir-Begun, S.; Usha, C.; Lok-Kirubahar, S.; Karthikeyan, M. Growth promoting and probiotic potential of the endophytic bacterium Rhodococcus globerulus colonizing the medicinal plant Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng. Int. J. Curr. Res. Rev. 2017, 9, 7. [Google Scholar]

- El-Deeb, B.; Fayez, K.; Gherbawy, Y. Isolation and characterization of endophytic bacteria from Plectranthus tenuiflorus medicinal plant in Saudi Arabia desert and their antimicrobial activities. J. Plant Interact. 2013, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, K.; Sharma, S.; Kalra, R. Isolation, identification and characterisation of fungal endophytes from Plectranthus amboinicus L. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett. 2021, 44, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temina, M.; Levitsky, D.O.; Dembitsky, V.M. Chemical constituents of the epiphytic and lithophilic lichens of the genus Collema. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2010, 4, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Hanuš, L.O.; Temina, M.; Dembitsky, V. Biodiversity of the chemical constituents in the epiphytic lichenized ascomycete Ramalina lacera grown on difference substrates Crataegus sinaicus, Pinus halepensis, and Quercus calliprinos. Biomed. Papers 2008, 152, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Dor, I.; Rotem, J.; Srebnik, M.; Dembitsky, V.M. Characterization of surface n-alkanes and fatty acids of the epiphytic lichen Xanthoria parietina, its photobiont a green alga Trebouxia sp., and its mycobiont, from the Jerusalem hills. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003, 270, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, D.W.; Cronan, Jr, J. E. Cyclopropane ring formation in membrane lipids of bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997, 61, 429. [Google Scholar]

- Salaün, J. Cyclopropane derivatives and their diverse biological activities. Small Ring Comp. Organic Synthesis 2000, VI, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Shkrob, I.; Dor, I. Separation and identification of hydrocarbons and other volatile compounds from cultured blue-green alga Nostoc sp. by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry using serially coupled capillary columns with consecutive nonpolar and semipolar stationary phases. J. Chromatogr. A 1999, 862, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Poroikov, V.V. Antitumor profile of carbon-bridged steroids (CBS) and triterpenoids. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Hydrobiological aspects of saturated, methyl-branched, and cyclic fatty acids derived from aquatic ecosystems: Origin, distribution, and biological activity. Hydrobiology 2022, 1, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakov, I.A.; Babushkin, A.S.; Yablokov, A.S.; Nawrozkij, M.B.; Vostrikova, O.V.; Shejkin, D.S.; Mkrtchyan, A.S.; Balakin, K.V. Synthesis and structure—activity relationships of cyclopropane-containing analogs of pharmacologically active compounds. Russian Chem. Bull. 2018, 67, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulinkovich, O.G. The chemistry of cyclopropanols. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Bioactive cyclobutane-containing alkaloids. J. Nat. Med. 2008, 62, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Naturally occurring bioactive Cyclobutane-containing (CBC) alkaloids in fungi, fungal endophytes, and plants. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kolk, M.R.; Janssen, M.A.; Rutjes, F.P.; Blanco-Ania, D. Cyclobutanes in small-molecule drug candidates. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202200020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergeiko, A.; Poroikov, V.V.; Hanuš, L.O.; Dembitsky, V.M. Cyclobutane-containing alkaloids: origin, synthesis, and biological activities. Open Med. Chem. J. 2008, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortuno, R.M.; Moglioni, A.G.; Moltrasio, G.Y. Cyclobutane biomolecules: synthetic approaches to amino acids, peptides and nucleosides. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenspach, M.; Steuer, C. α-Pinene: A never-ending story. Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, A.T.; Ribeiro, M.; Judas, F.; Salgueiro, L.; Lopes, M.C.; Cavaleiro, C.; Mendes, A.F. Anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective activity of (+)-α-pinene: structural and enantiomeric selectivity. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameur, S. , Toumi, M., Bendif, H., Derbak, L., Yildiz, I., Rebbas, K., Demirtas, I., Flamini, G., Bruno, M., Garzoli, S. Cistus libanotis from Algeria: Phytochemical analysis by GC/MS, HS-SPME-GC/MS, LC–MS/MS and its anticancer activity. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2024, 136, 106747. [Google Scholar]

| Peak | RT | % | Compound | RI |

| 1 | 1.643 | 87.35 | 2-methyl-1-butene | 488 |

| 2 | 1.820 | 7.99 | cis-1,2-dimethyl-cyclopropane | 516 |

| 3 | 2.373 | 0.10 | 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol | 614 |

| 4 | 2.870 | 0.07 | 3-methyl-butanal | 652 |

| 5 | 2.998 | 0.21 | 2-methyl-butanal | 662 |

| 6 | 11.664 | 1.58 | alpha-thujene | 931 |

| 7 | 11.872 | 1.77 | alpha-pinene | 937 |

| 8 | 13.363 | 0.29 | sabinene | 976 |

| 9 | 13.428 | 0.29 | beta-pinene | 980 |

| 10 | 14.654 | 0.01 | delta-3-carene | 1011 |

| 11 | 15.167 | 0.02 | p-cymene | 1022 |

| 12 | 15.295 | 0.04 | limonene | 1030 |

| 13 | 15.680 | 0.01 | cis-beta-ocimene | 1035 |

| 14 | 16.017 | 0.12 | trans-beta-ocimene | 1037 |

| 15 | 16.337 | 0.03 | gamma-terpinene | 1060 |

| 16 | 24.931 | 0.12 | caryophyllene | 1419 |

| Peak | RT | % | Compound | RI |

| 1 | 11.68 | 31.90 | α-thujene | 931 |

| 2 | 11.888 | 42.82 | α-pinene | 937 |

| 3 | 12.329 | 0.44 | dehydrosabinene | 947 |

| 4 | 13.371 | 6.91 | sabinene | 976 |

| 5 | 13.436 | 7.29 | β-pinene | 980 |

| 6 | 14.069 | 0.27 | β-myrcene | 991 |

| 7 | 15.167 | 0.59 | p-cymene | 1022 |

| 8 | 15.303 | 0.64 | limonene | 1030 |

| 9 | 15.688 | 0.90 | cis-β-ocimene | 1040 |

| 10 | 16.025 | 2.12 | trans-β-ocimene | 1050 |

| 11 | 16.346 | 0.21 | γ-terpinene | 1060 |

| 12 | 24.017 | 0.21 | α-cubebene | 1351 |

| 13 | 24.378 | 0.55 | copaene | 1376 |

| 14 | 24.506 | 0.61 | β-bourbonene | 1384 |

| 15 | 24.554 | 0.26 | β-copaene | 1418 |

| 16 | 24.931 | 3.04 | caryophyllene | 1419 |

| 17 | 25.885 | 1.29 | aromadendrene | 1440 |

| 18 | 25.981 | 0.01 | β-cadinene | 1520 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).