Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2.1. Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

2.2. Theory of Consumption Value (TCV)

2.3. Linking TPB and TCV Constructs

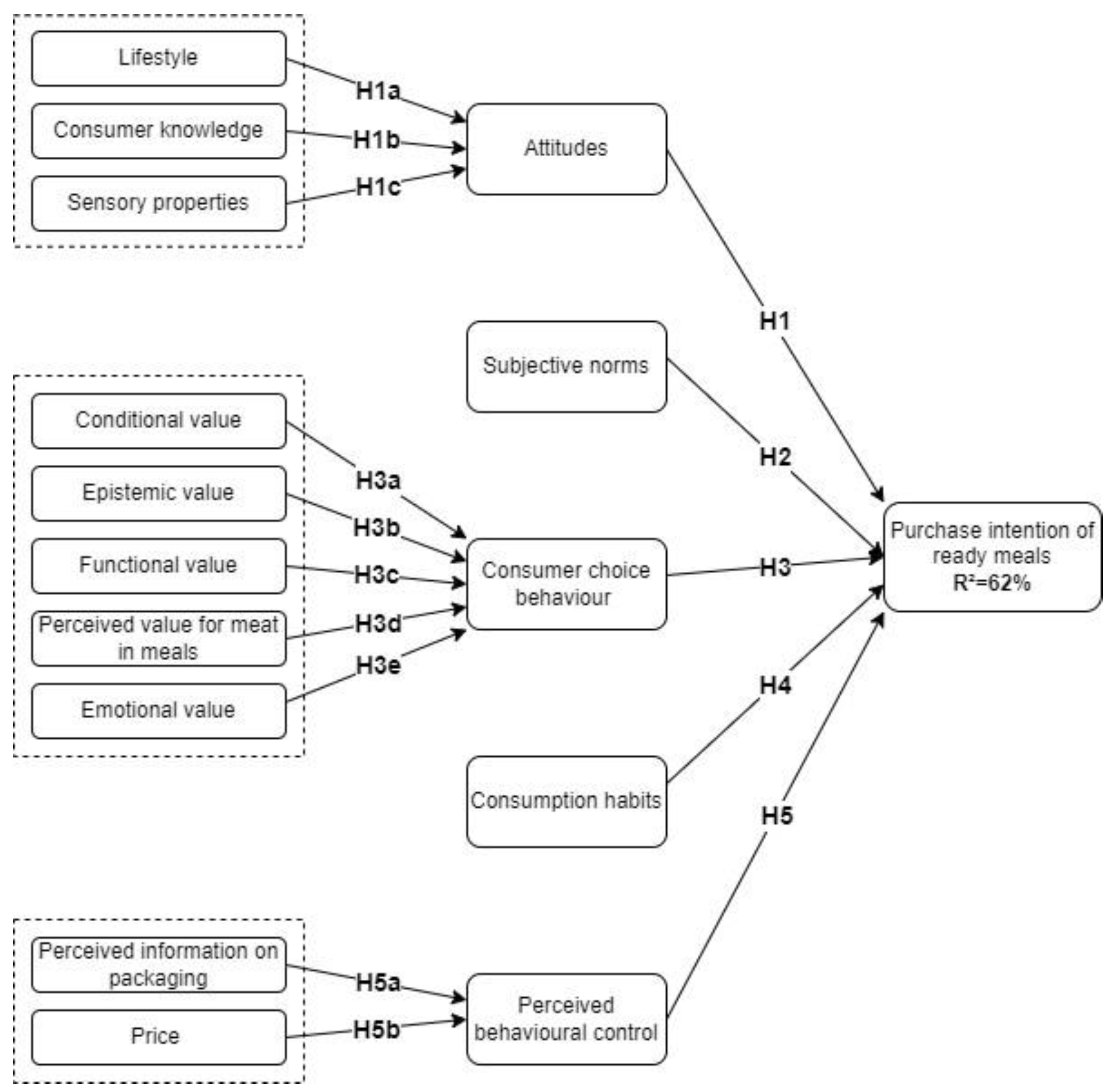

2.4. Hypotheses Development and Proposed Research Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.2. Sampling and Survey Distribution

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Measurement Model Analysis: Reliability and Validity

4.2. Structural Model Analysis: Goodness of Fit

4.3. Path Analysis and Hypotheses Testing

4.3.1. Attitudes

4.3.2. Subjective Norms

4.3.3. Consumer Choice Behaviour of Meat-Based Chilled Ready Meals

4.3.4. Consumption Habits

4.3.5. Perceived Behavioural Control

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TPB | Theory of planned behaviour |

| TCV | Theory of consumption values |

| PLSPM | Partial least squares path modelling |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Construct | Manifest variables | Question statements (seven-point Likert scale) | Source of adoption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional Value (CON) | CON1 | I can save time in the shop when I purchase chilled ready meals. | [60,67] |

| CON2 | Chilled ready meals are a good back up to have in the home when I have little time to prepare meals. | [6] | |

| CON3 | Chilled ready meals are fast to prepare at home. | [6] | |

| CON4 | It is easier for me to purchase a meat-based chilled ready meal than cooking a meal from scratch. | [68,69] | |

| Epistemic Value (EPV) | EPV1 | I would be more likely purchase a meat-based chilled ready meal if it’s labelled as less salt and less fat. | [70] |

| EPV2 | When I purchase a meat-based chilled ready meal, I always look at nutritional information. | ||

| EPV 3 | I like meat-based chilled ready meals if those promote my wellbeing and healthy lifestyle. | [71,72] | |

| Perceived value of meat in meals (PMTV) | PMTV1 | I would be more likely to purchase a chilled ready meal if it contains meat and vegetables as it provides me with better nutrition. | [71] |

| PMTV2 | I would be more likely to purchase a meat-based chilled ready meal as it promotes my health and well-being. | [67] | |

| PMTV3 | I would expect chilled ready meals containing meat to be healthier and more nutritious than those without meat. | ||

| PMTV3 | I would pay more if the chilled ready meals contain meat. | ||

| Attitudes (ATU) | ATU1 | Meat-based chilled ready meals are well balanced meals | |

| ATU2 | Meat-based chilled ready meals can provide my daily nutritional requirements. | ||

| ATU3 | I would be happy to purchase meat-based chilled ready meals that would give sustained energy. | [73] | |

| ATU4 | I think chilled ready meals containing meat would boost my mood over those without meat. | [73] | |

| Functional value (FUN) | FUN1 | It is great if the meat-based chilled ready meal has its own functional benefits (for example, weight loss, muscle gain, digestibility, fast absorption of nutrients, etc.). | |

| FUN2 | I prefer if the meat-based chilled ready meals have higher protein content. | ||

| FUN3 | I prefer if the meat-based chilled ready meals are easy to digest. | ||

| FUN4 | I will prioritize the functional benefits over other attributes of the meal when I am purchasing a chilled ready meal contain meat. | ||

| Consumer knowledge on ready meals (CNKW) | CKNW1 | I feel that I have clear understanding and knowledge of meat-based chilled ready meals. | [71] |

| CKNW2 | Most meat-based chilled ready meals have an acceptable standard of quality. | [18] | |

| CKNW3 | I am knowledgeable about meat-based chilled ready meals I eat and how they can meet my nutritional need. | [71] | |

| Consumer Choice behaviour (CCB) | CCB1 | Meat-based chilled ready meals can be good value for money when reasonably priced. | [6] |

| CCB2 | Meat-based chilled ready meals have acceptable standard of quality for paid price. | [18] | |

| CCB3 | Meat-based chilled ready meals can be an economical meal. | ||

| CCB3 | When I buy meat-based chilled ready meals, I would ensure that I am getting my money’s worth | [74] | |

| Subjective Norms (SUBN) | SUBN1 | I’m happy to tell people in my social circle that I purchase meat-based chilled ready meals. | |

| SUBN2 | If people in my social circle recommend that I purchase meat-based chilled ready meals, I would purchase meat-based chilled ready meals. | [12,47] | |

| SUBN3 | If people whose opinion I value recommend that I purchase chilled ready meals containing meat, I would purchase chilled ready meals containing meat. | [68] | |

| Emotional Value (EMV) | EMV1 | Meat-based chilled ready meals that look fresh and appealing would positively influence my purchasing intention. | [70] |

| EMV2 | Meat-based chilled ready meals that have a “freshly cooked” appearance would positively influence my purchasing intention. | ||

| EMV3 | Ready meal package design and graphics would positively influence my purchasing intention. | [47] | |

| EMV4 | I expect the meat-based chilled ready meal inside the packaging to look the same as displayed on the packaging | ||

| Perceived information on package (PINF) | PINF1 | I would like to know nutrition facts, shelf life and ingredients before purchasing meat-based chilled ready meals. | [70] |

| PINF2 | I’m more likely to purchase a meat-based chilled ready meal that has a clear image of the meal on the packaging. | ||

| PINF3 | When I purchase, I look for graphics that indicate meals contain low fat and salt. | ||

| PINF4 | When I purchase, I look for health star ratings on the package. | ||

| Sensory appeal (SEAP) | SEAP1 | The taste of the meat-based chilled ready meal is very important for me | [72] |

| SEAP2 | The texture of the meat-based chilled ready meal is very important for me | [60,72] | |

| SEAP3 | The aroma of the meat-based chilled ready meal is very important for me | ||

| SEAP4 | The appearance of the meat-based chilled ready meal is very important for me | ||

| SEAP5 | The fresh cooked quality of the meat-based chilled ready meal is very important for me. | ||

| Consumption habits (CHAB) | CHAB1 | I usually consume meat-based chilled ready meals as my main meal. | [6] |

| CHAB2 | I eat meat-based chilled ready meal at least once a week | [6] | |

| CHAB3 | I regularly purchase meat-based chilled ready meals during my weekly shopping. | [75] | |

| CHAB4 | A large proportion of my weekly food consumption is meat-based chilled ready meals. | [74] | |

| Perceived behavioural control (PBCN) | PBCN1 | I make most of the decisions around what myself and my household consume. | [47] |

| PBCN2 | I do most of the household food shopping. | ||

| PBCN3 | I am in control of the number of meat-based chilled ready meals I consume. | [12,68,70] | |

| PBCN4 | I think it’s easy for me to buy meat-based chilled ready meals. | [12,68,70] | |

| PBCN5 | I believe that I have the money resources and the ability to buy meat-based chilled ready meals. | [47] | |

| Price (PRIC) | PRIC1 | Price of the meat-based chilled ready meal is important to me. | [70] |

| PRIC2 | I am willing to pay a premium price if the meat-based chilled ready meals meet my nutritional needs. | [76] | |

| PRIC3 | I am happy to pay a premium price if the meat-based chilled ready meal is excellent quality. | ||

| Lifestyle (LFST) | LFST1 | I purchase meat-based chilled ready meals for consumption when I finish work late. | [14,71,77] |

| LFST2 | Meat-based chilled ready meals are less stressful than preparing cooked meal from scratch and help me lead a relaxed lifestyle. | ||

| Purchase Intension (PINT) | PINT1 | I am willing to purchase meat-based chilled ready meals within next 4 weeks. | [47,68] |

| PINT2 | I intend to purchase meat-based chilled ready meals within next 4 weeks. | [47,68] | |

| PINT3 | I plan to purchase meat-based chilled ready meals within next 4 weeks. | [47,68] |

Appendix A.2

| Latent variable | Manifest variables | Mean | S.D. | Standardized loadings | Loadings | Communalities | Standardized loadings (Bootstrap) | Standard error | Lower bound (95%) | Upper bound (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase intention | PINT1 | 4.155 | 1.895 | 0.901 | 0.058 | 0.812 | 0.902 | 0.010 | 0.882 | 0.923 |

| PINT2 | 3.517 | 1.859 | 0.976 | 0.061 | 0.953 | 0.976 | 0.003 | 0.966 | 0.982 | |

| PINT3 | 3.310 | 1.888 | 0.944 | 0.060 | 0.891 | 0.944 | 0.007 | 0.924 | 0.958 | |

| Attitudes | ATTU1 | 4.709 | 1.426 | 0.809 | 0.058 | 0.655 | 0.809 | 0.028 | 0.745 | 0.859 |

| ATTU2 | 3.744 | 1.672 | 0.780 | 0.058 | 0.609 | 0.777 | 0.032 | 0.705 | 0.839 | |

| ATTU3 | 3.862 | 1.294 | 0.684 | 0.054 | 0.468 | 0.680 | 0.043 | 0.592 | 0.766 | |

| ATTU4 | 4.144 | 1.351 | 0.776 | 0.071 | 0.603 | 0.774 | 0.034 | 0.696 | 0.840 | |

| Subjective norms | SUBN1 | 4.446 | 1.551 | 0.743 | 0.054 | 0.552 | 0.743 | 0.037 | 0.649 | 0.813 |

| SUBN2 | 3.972 | 1.470 | 0.917 | 0.063 | 0.840 | 0.916 | 0.013 | 0.869 | 0.934 | |

| SUBN3 | 4.313 | 1.481 | 0.883 | 0.062 | 0.780 | 0.881 | 0.021 | 0.827 | 0.912 | |

| Perceived behavioural control | PBCN1 | 5.642 | 1.385 | 0.549 | 0.047 | 0.302 | 0.547 | 0.098 | 0.330 | 0.738 |

| PBCN2 | 5.478 | 1.709 | 0.590 | 0.062 | 0.348 | 0.579 | 0.109 | 0.332 | 0.777 | |

| PBCN3 | 6.183 | 1.086 | 0.503 | 0.033 | 0.253 | 0.496 | 0.082 | 0.289 | 0.633 | |

| PBCN4 | 4.767 | 1.551 | 0.810 | 0.077 | 0.655 | 0.803 | 0.054 | 0.664 | 0.881 | |

| PBCN5 | 5.401 | 1.377 | 0.553 | 0.047 | 0.305 | 0.551 | 0.068 | 0.418 | 0.714 | |

| Emotional value | EMV1 | 5.310 | 1.214 | 0.871 | 0.060 | 0.758 | 0.873 | 0.026 | 0.805 | 0.918 |

| EMV 2 | 5.397 | 1.206 | 0.849 | 0.058 | 0.720 | 0.851 | 0.029 | 0.770 | 0.908 | |

| EMV 3 | 4.836 | 1.377 | 0.837 | 0.066 | 0.700 | 0.840 | 0.027 | 0.764 | 0.892 | |

| EMV 4 | 5.356 | 1.442 | 0.645 | 0.053 | 0.416 | 0.633 | 0.063 | 0.480 | 0.751 | |

| Conditional value | CON1 | 4.675 | 1.547 | 0.729 | 0.055 | 0.531 | 0.725 | 0.041 | 0.636 | 0.804 |

| CON2 | 5.231 | 1.552 | 0.845 | 0.064 | 0.713 | 0.844 | 0.021 | 0.800 | 0.887 | |

| CON3 | 5.707 | 1.143 | 0.677 | 0.038 | 0.459 | 0.675 | 0.045 | 0.562 | 0.754 | |

| CON4 | 4.690 | 1.764 | 0.826 | 0.071 | 0.683 | 0.826 | 0.028 | 0.745 | 0.886 | |

| Epistemic value | EPV1 | 4.552 | 1.601 | 0.783 | 0.066 | 0.614 | 0.787 | 0.051 | 0.664 | 0.903 |

| EPV 2 | 4.606 | 1.791 | 0.662 | 0.062 | 0.439 | 0.648 | 0.084 | 0.450 | 0.830 | |

| EPV 3 | 4.972 | 1.577 | 0.608 | 0.050 | 0.370 | 0.598 | 0.092 | 0.377 | 0.750 | |

| Functional value | FUN1 | 4.636 | 1.465 | 0.823 | 0.070 | 0.677 | 0.826 | 0.031 | 0.743 | 0.888 |

| FUN2 | 4.780 | 1.324 | 0.677 | 0.052 | 0.459 | 0.672 | 0.057 | 0.520 | 0.779 | |

| FUN3 | 4.860 | 1.283 | 0.738 | 0.055 | 0.545 | 0.745 | 0.044 | 0.639 | 0.827 | |

| FUN5 | 3.897 | 1.481 | 0.682 | 0.059 | 0.466 | 0.667 | 0.076 | 0.467 | 0.807 | |

| Consumption habits | CHAB1 | 2.269 | 1.634 | 0.763 | 0.049 | 0.582 | 0.765 | 0.029 | 0.704 | 0.822 |

| CHAB2 | 2.558 | 1.906 | 0.927 | 0.070 | 0.859 | 0.927 | 0.009 | 0.907 | 0.946 | |

| CHAB3 | 2.537 | 1.826 | 0.935 | 0.067 | 0.875 | 0.935 | 0.008 | 0.914 | 0.950 | |

| CHAB4 | 1.804 | 1.319 | 0.812 | 0.042 | 0.660 | 0.812 | 0.023 | 0.766 | 0.859 | |

| Sensory properties | SEAP1 | 6.252 | 0.935 | 0.756 | 0.050 | 0.572 | 0.733 | 0.103 | 0.401 | 0.854 |

| SEAP2 | 6.086 | 0.961 | 0.821 | 0.055 | 0.674 | 0.808 | 0.060 | 0.666 | 0.904 | |

| SEAP3 | 5.940 | 1.007 | 0.857 | 0.061 | 0.735 | 0.843 | 0.045 | 0.700 | 0.905 | |

| SEAP4 | 5.897 | 1.035 | 0.892 | 0.065 | 0.796 | 0.891 | 0.023 | 0.827 | 0.939 | |

| SEAP5 | 6.073 | 0.999 | 0.838 | 0.059 | 0.702 | 0.828 | 0.056 | 0.633 | 0.894 | |

| Perceived info on package | PINF1 | 5.825 | 1.113 | 0.644 | 0.046 | 0.415 | 0.634 | 0.065 | 0.472 | 0.752 |

| PINF2 | 5.711 | 1.113 | 0.618 | 0.044 | 0.381 | 0.621 | 0.076 | 0.462 | 0.760 | |

| PINF3 | 4.724 | 1.421 | 0.851 | 0.077 | 0.725 | 0.846 | 0.039 | 0.769 | 0.923 | |

| PINF4 | 5.358 | 1.317 | 0.769 | 0.065 | 0.591 | 0.757 | 0.065 | 0.564 | 0.859 | |

| Lifestyle | LFST1 | 4.647 | 1.786 | 0.840 | 0.057 | 0.706 | 0.837 | 0.034 | 0.749 | 0.900 |

| LFST2 | 4.168 | 1.779 | 0.910 | 0.062 | 0.829 | 0.910 | 0.024 | 0.859 | 0.950 | |

| Consumer knowledge | CKNW1 | 4.088 | 1.514 | 0.713 | 0.057 | 0.508 | 0.686 | 0.089 | 0.419 | 0.835 |

| CKNW2 | 4.190 | 1.510 | 0.624 | 0.050 | 0.389 | 0.598 | 0.107 | 0.348 | 0.806 | |

| CKNW3 | 3.853 | 1.334 | 0.900 | 0.064 | 0.811 | 0.906 | 0.047 | 0.805 | 0.997 | |

| Perceived value of meat in meals | PMTV1 | 4.959 | 1.584 | 0.769 | 0.058 | 0.592 | 0.767 | 0.035 | 0.666 | 0.825 |

| PMTV2 | 3.944 | 1.659 | 0.792 | 0.063 | 0.627 | 0.793 | 0.032 | 0.681 | 0.842 | |

| PMTV3 | 3.377 | 1.639 | 0.812 | 0.064 | 0.659 | 0.811 | 0.030 | 0.739 | 0.864 | |

| PMTV4 | 4.050 | 1.573 | 0.734 | 0.055 | 0.539 | 0.740 | 0.039 | 0.656 | 0.807 | |

| Consumer choice behaviour | CCB1 | 4.332 | 1.521 | 0.879 | 0.070 | 0.773 | 0.880 | 0.013 | 0.846 | 0.902 |

| CCB2 | 3.966 | 1.367 | 0.830 | 0.059 | 0.689 | 0.827 | 0.019 | 0.769 | 0.859 | |

| CCB3 | 3.821 | 1.503 | 0.808 | 0.063 | 0.653 | 0.805 | 0.021 | 0.746 | 0.837 | |

| CCB4 | 4.922 | 1.335 | 0.540 | 0.038 | 0.292 | 0.542 | 0.050 | 0.447 | 0.657 | |

| Price | PRIC1 | 4.636 | 1.412 | 0.505 | 0.028 | 0.164 | 0.412 | 0.098 | 0.209 | 0.583 |

| PRIC2 | 5.220 | 1.355 | 0.709 | 0.061 | 0.503 | 0.698 | 0.070 | 0.488 | 0.806 | |

| PRIC3 | 5.817 | 1.110 | 0.907 | 0.075 | 0.823 | 0.901 | 0.028 | 0.835 | 0.948 |

References

- Van der Horst, K., T.A. Brunner, and M. Siegrist, Ready-meal consumption: associations with weight status and cooking skills. Public health nutrition, 2011. 14(2): p. 239-245. [CrossRef]

- Prepared Meals Market, 2022-2029. 2022, Fortune Business Insights. p. 156. https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/prepared-meals-market-105002.

- StatsNZ, Kiwis eating more food on the go. 2017, Statistics New Zealand.

- StatsNZ, Kiwis growing taste for takeaways and eating out. 2020, Statistics New Zealand.

- Geeroms, N., W. Verbeke, and P. Van Kenhove, Consumers’ health-related motive orientations and ready meal consumption behaviour. Appetite, 2008. 51(3): p. 704-712. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, D., C. Cowan, and M. McCarthy, The role of attitudes, subjective norm, perceived control and habit in the consumption of ready meals and takeaways in Great Britain. Food Quality and Preference, 2006. 17(6): p. 474-481. [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.I.d.A., et al., A consumer-oriented classification system for home meal replacements. Food Quality and Preference, 2001. 12(4): p. 229-242. [CrossRef]

- Verlegh, P.W.J. and M.J.J.M. Candel, The consumption of convenience foods: reference groups and eating situations. Food Quality and Preference, 1999. 10(6): p. 457-464. [CrossRef]

- Calderón, L.A., et al., The utility of Life Cycle Assessment in the ready meal food industry. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2010. 54(12): p. 1196-1207. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, N.V., et al., Likelihood of buying healthy convenience food: An at-home testing procedure for ready-to-heat meals. Food quality and preference, 2012. 24(1): p. 171-178. [CrossRef]

- Raj, S. and B. Mishra, Socio-demographic factor and selected buying behavioral attributes of purchasing convenience food: Multiple correspondence analyses to explore the relationship. Parikalpana: KIIT Journal of Management, 2020. 16(1and2): p. 84-107. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, N.V., S.J. Sijtsema, and G. Hall, Predicting consumers’ intention to consume ready-to-eat meals. The role of moral attitude. Appetite, 2010. 55(3): p. 534-539. [CrossRef]

- Botonaki, A. and K. Mattas, Revealing the values behind convenience food consumption. Appetite, 2010. 55(3): p. 629-638. [CrossRef]

- Ana, I.d.A., et al., To cook or not to cook: a means-end study of motives for choice of meal solutions. Food quality and preference, 2007. 18(1): p. 77-88. [CrossRef]

- Gofton, L., Convenience and the moral status of consumer practices, in Food choice and the consumer., D. Marshall, Editor. 1995, Blackie Academic & Professional: Glasgow, United Kingdom. p. 152-181.

- Fishbein, M. and I. Ajzen, Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 1977. 10(2): p. 130-132.

- Sheth, J.N., B.I. Newman, and B.L. Gross, Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research, 1991. 22(2): p. 159-170. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C. and G.N. Soutar, Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of Retailing, 2001. 77(2): p. 203-220. [CrossRef]

- Amin, S. and M.T. Tarun, Effect of consumption values on customers’ green purchase intention: a mediating role of green trust. Social Responsibility Journal, 2021. 17(8): p. 1320-1336. [CrossRef]

- Al-Waseti, L. and M. ve İrfanoğlu, The effect of consumption value on organic food purchase intention with the mediating role of consumer involvement. Turkish Online Journal of Design Art and Communication, 2022. 12(1): p. 177-191. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D. and G. Dash, Using the consumption values to investigate consumer purchase intentions towards natural food products. British Food Journal, 2022. 125(2): p. 551-569. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H., H. Kim, and K. Severt, Predicting college students’ intention to purchase local food using the theory of consumption values. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 2021. 24(3): p. 286-309. [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J. and S.S. Kim, Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. International journal of hospitality management, 2018. 71: p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.J. and S. Zou, Consumption value in food tourism: the effects on purchase involvement and post-travel behaviours. Tourism Recreation Research, 2023: p. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Sussman, R. and R. Gifford, Causality in the Theory of Planned Behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2018. 45(6): p. 920-933. [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M., H. Ramkissoon, and M. Fekete-Farkas, Green purchase and sustainable consumption: A comparative study between European and non-European tourists. Tourism Management Perspectives, 2022. 43: p. 100980. [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.Y., C.W. Cheah, and N. Ganesan, The rise of the food truck phenomenon: an integrated model of consumers' intentions to visit food trucks. British Food Journal, 2023. 125(9): p. 3288-3303. [CrossRef]

- Huriah, T., et al., Understanding the purchasing behaviors of halal cosmetics of teenagers in Indonesia using the theory of planned behavior and theory of consumption value. Bali Medical Journal, 2022. 11(3): p. 1608-1613. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., et al., Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour. 1980: Prentice Hall PTR.

- Ajzen, I., The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 1991. 50(2): p. 179-211. [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. and G. Armstrong, Principles of marketing. 17 ed. 2018, United Kingdom: Pearson Education Limited. 736.

- De Boer, M., et al., The influence of lifestyle characteristics and beliefs about convenience food on the demand for convenience foods in the Irish market. Food quality and preference, 2004. 15(2): p. 155-165. [CrossRef]

- Veenma, K., C. Kistemaker, and M. Lowik, Socio-demographic, psycho-social and life-style factors affecting consumption of convenience food. ACR European Advances, 1995.

- Remnant, J. and J. Adams, The nutritional content and cost of supermarket ready-meals. Cross-sectional analysis. Appetite, 2015. 92: p. 36-42. [CrossRef]

- Costell, E., A. Tárrega, and S. Bayarri, Food acceptance: The role of consumer perception and attitudes. Chemosensory perception, 2010. 3: p. 42-50. [CrossRef]

- Laguna, L., et al., Do Consumers Change Their Perception of Liking, Expected Satiety, and Healthiness of a Product If They Know It Is a Ready-to Eat Meal? Foods, 2020. 9(9): p. 1257. [CrossRef]

- Kalafatis, S., L. Ledden, and A. Mathioudakis, Re-specification of the theory of consumption values. 2010.

- Sheth, J., B. Newman, and B. Gross, Consumption Values and Market Choices: Theory and Applications. 1991: South Western Publishing Co.

- Macdiarmid, J.I., et al., How important is healthiness, carbon footprint and meat content when purchasing a ready meal? Evidence from a non-hypothetical discrete choice experiment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021. 282: p. 124510. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.R. and N.J. Rabolt, Consumer behavior: In fashion. 2004, Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

- Ajzen, I. and T.J. Madden, Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 1986. 22(5): p. 453-474. [CrossRef]

- Heckathorn, D.D., Comment: Snowball versus respondent-driven sampling. Sociological methodology, 2011. 41(1): p. 355-366. [CrossRef]

- Browne, K., Snowball sampling: using social networks to research non-heterosexual women. International journal of social research methodology, 2005. 8(1): p. 47-60. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2 ed. 2013, New York: Academic press.

- Hair, J.F., et al., When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 2019. 31(1): p. 2-24. [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M., M. Sarstedt, and D.W. Straub, Editor's comments: a critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in" MIS Quarterly". MIS quarterly, 2012. 36(1): p. iii-xiv. [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.-L., C.-C. Hsu, and H.-S. Chen, To buy or not to buy? Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions for suboptimal food. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2018. 15(7): p. 1431. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, G., PLS path modeling with R. Berkeley: Trowchez Editions, 2013. 383: p. 2013.

- Hair Jr., J.F., et al., Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. International Journal of Research & Method in Education. Vol. 38. 2021: Springer Nature. 197.

- Chin, W.W. and P.R. Newsted, Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. Statistical strategies for small sample research, 1999. 1(1): p. 307-341.

- Cheung, G.W., et al., Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dirsehan, T. and E. Cankat, Role of mobile food-ordering applications in developing restaurants’ brand satisfaction and loyalty in the pandemic period. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 2021. 62: p. 102608. [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F. and N.B. Miller, A primer for soft modeling. 1992: University of Akron Press.

- Chin, W.W., The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling, in Modern methods for business research. 1998, Psycology Press: 605 Thrid Avenue, New York, NY10017, USA. p. 295-336.

- Olobatuyi, M.E., A user's guide to path analysis. 2006, 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706: University Press of America. 168.

- Reed, Z., H. McIlveen-Farley, and C. Strugnell, Factors affecting consumer acceptance of chilled ready meals on the island of Ireland. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 2003. 27(1): p. 2-10. [CrossRef]

- Niosi, A., Introduction to consumer behaviour. 2021: BCcampus Open Education.

- Biswas, A. and M. Roy, Leveraging factors for sustained green consumption behavior based on consumption value perceptions: testing the structural model. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2015. 95: p. 332-340. [CrossRef]

- Wales, M.-E., Understanding the role of convenience in consumer food choices: a review article. SURG Journal, 2009. 2(2): p. 40-48. [CrossRef]

- Candel, M.J., Consumers' convenience orientation towards meal preparation: conceptualization and measurement. Appetite, 2001. 36(1): p. 15-28. [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, M., et al., Global and local diet popularity rankings, their secular trends, and seasonal variation in Google Trends data. Nutrition, 2020. 79-80: p. 110759. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D.M., J.C. Beaulieu, and R. Shewfelt, Color, Flavor, Texture, and Nutritional Quality of Fresh-Cut Fruits and Vegetables: Desirable Levels, Instrumental and Sensory Measurement, and the Effects of Processing. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2010. 50(5): p. 369-389. [CrossRef]

- Basaran, U. and R. Aksoy, The effect of perceived value on behavioural intentions. Journal of Management Marketing and Logistics, 2017. 4(1): p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Siekierski, P., M.C. Ponchio, and V.I. Strehlau, Influence of lifestyles related to eating habits in ready meal consumption: comparative study between São Paulo and Rome. Revista Brasileira de Gestão de Negócios, 2013. 15: p. 325-342. [CrossRef]

- Contini, C., et al., Food habits and the increase in ready-to-eat and easy-to-prepare products, in Food hygiene and toxicology in ready-to-eat foods. 2016, Elsevier. p. 3-14.

- Weatherell, C., A. Tregear, and J. Allinson, In search of the concerned consumer: UK public perceptions of food, farming and buying local. Journal of rural studies, 2003. 19(2): p. 233-244. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W., H.J. Sung, and H.M. Jeon, Determinants of continuous intention on food delivery apps: Extending UTAUT2 with Information Quality. Sustainability, 2019. 11(11): p. 3141. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 2002. 32(4): p. 665-683. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Understanding the purchase intention towards remanufactured product in closed-loop supply chains. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 2013. 43(10): p. 866-888. [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A., T.M. Pollard, and J. Wardle, Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: the food choice questionnaire. Appetite, 1995. 25(3): p. 267-284. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, B. and A. Recker, The Effects of Consumer Knowledge and Values on Attitudes and Purchase Intentions: A Quantitative Study of Organic Personal Care Products Among German Female Consumers, in Umeå School of Business and Economics. 2014, Umeå University.

- Gómez-Luciano, C.A., et al., Consumers’ willingness to purchase three alternatives to meat proteins in the United Kingdom, Spain, Brazil and the Dominican Republic. Food Quality and Preference, 2019. 78: p. 103732. [CrossRef]

- Urala, N. and L. Lähteenmäki, Consumers’ changing attitudes towards functional foods. Food Quality and Preference, 2007. 18(1): p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, S.N., P.E. Lalp, and M.M. Naba, Consumers’ perceptions, attitudes and purchase intention towards private label food products in Malaysia. Asian Journal of Business and Management Sciences, 2012. 2(8): p. 73-90. [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A. and M. Fygenson, Understanding and predicting electronic commerce adoption: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. MIS quarterly, 2006. 30(1): p. 115-143. [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, B., Assessment of the impacts of the consumers’ awareness of organic food on consumption behavior. Food Science and Technology, 2019. 39(4): p. 881-888. [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J., Health consciousness and health behavior: the application of a new health consciousness scale. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 1990. 6(4): p. 228-237. [CrossRef]

| Variable\Statistic | Categories | Frequencies | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 321 | 69.2 |

| Male | 143 | 30.8 | |

| Age range | Below 20 | 9 | 1.9 |

| 20-29 | 107 | 23.1 | |

| 30-39 | 118 | 25.4 | |

| 40-49 | 92 | 19.8 | |

| 50-59 | 75 | 16.2 | |

| 60 or more | 63 | 13.5 | |

| Highest level of education | Secondary school qualification-Not completed | 13 | 2.8 |

| Secondary school qualification-Completed | 55 | 11.9 | |

| Certificate/Diploma | 54 | 11.6 | |

| Bachelors degree | 135 | 29.1 | |

| Postgraduate cert/diploma | 8 | 1.7 | |

| Masters degree | 104 | 22.4 | |

| PhD | 95 | 20.5 | |

| Working status | Casual | 15 | 3.2 |

| Full time | 286 | 61.6 | |

| Part-time | 83 | 17.9 | |

| Retired | 12 | 2.6 | |

| Self-employed | 17 | 3.6 | |

| Studying | 44 | 9.5 | |

| Unemployed | 7 | 1.5 | |

| Occupation | Accommodation and Food Services | 22 | 4.7 |

| Administrative and Support Services | 34 | 7.3 | |

| Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 49 | 10.6 | |

| Art, Sport and Recreation | 7 | 1.5 | |

| Construction | 4 | 0.9 | |

| Education and Training | 107 | 23.1 | |

| Electricity, Gas, Water and Waste services | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Financial and Insurance Services | 5 | 1.1 | |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 14 | 3.0 | |

| Housewife/Househusband | 8 | 1.7 | |

| Information, Media and Telecommunication | 12 | 2.6 | |

| Manufacturing | 18 | 3.9 | |

| Professional, Scientific and Technical Services | 150 | 32.3 | |

| Public administration and Safety | 6 | 1.3 | |

| Transport, Postal and Warehousing | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Wholesale and Retail Trade | 21 | 4.5 | |

| Other Services | 4 | 0.9 | |

| Annual income before tax (NZD) | Below 10,000 | 52 | 11.2 |

| 10,001-30,000 | 72 | 15.6 | |

| 30,001-50,000 | 60 | 12.9 | |

| 50,001-70,000 | 99 | 21.3 | |

| 70,001-100,000 | 115 | 24.8 | |

| Above 100,001 | 66 | 14.2 | |

| Type of household | Single person residing alone | 62 | 13.4 |

| Shared house with siblings | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Shared house with unrelated individuals | 77 | 16.6 | |

| Family home-one parent with child(ren) | 11 | 2.4 | |

| Family home-couple with no children | 134 | 28.9 | |

| Family home-couple with child(ren) | 150 | 32.3 | |

| Extended family/multi-generation home | 28 | 6.0 | |

| European (including NZ European) | 318 | 68.5 | |

| Ethnic group | Māori | 18 | 3.9 |

| Pacific | 8 | 1.7 | |

| Asian | 99 | 21.3 | |

| Middle Eastern/ Latin American/ African | 17 | 3.7 | |

| American | 4 | 0.9 |

| Latent variable | Dimensions | Cronbach’s alpha | D.G. rho (PCA)† | Condition number | AVE‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory properties | 5 | 0.897 | 0.924 | 3.822 | 0.696 |

| Lifestyle | 2 | 0.702 | 0.870 | 1.832 | 0.768 |

| Consumer knowledge | 3 | 0.710 | 0.844 | 2.322 | 0.569 |

| Attitudes | 4 | 0.754 | 0.847 | 3.024 | 0.584 |

| Subjective norms | 3 | 0.801 | 0.884 | 3.543 | 0.724 |

| Perceived information on package | 4 | 0.709 | 0.827 | 2.255 | 0.528 |

| Price | 3 | 0.501 | 0.759 | 1.718 | 0.497 |

| Perceived behavioural control | 5 | 0.645 | 0.777 | 2.579 | 0.373 |

| Consumption habits | 4 | 0.885 | 0.927 | 3.962 | 0.744 |

| Emotional value | 4 | 0.804 | 0.872 | 4.240 | 0.649 |

| Conditional value | 4 | 0.778 | 0.864 | 2.759 | 0.596 |

| Epistemic value | 3 | 0.445 | 0.728 | 1.435 | 0.474 |

| Functional value | 4 | 0.713 | 0.824 | 2.187 | 0.537 |

| Perceived value of meat in meals | 4 | 0.781 | 0.860 | 2.479 | 0.604 |

| Consumer choice behaviour | 4 | 0.775 | 0.860 | 2.669 | 0.602 |

| Purchase intention | 3 | 0.934 | 0.958 | 6.587 | 0.885 |

| GoF | GoF (Bootstrap) | Standard error | Lower bound (95%) | Upper bound (95%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute | 0.435 | 0.445 | 0.014 | 0.414 | 0.477 |

| Relative | 0.870 | 0.856 | 0.014 | 0.829 | 0.884 |

| Outer model | 0.987 | 0.984 | 0.004 | 0.972 | 0.991 |

| Inner model | 0.881 | 0.870 | 0.014 | 0.847 | 0.898 |

| Hypotheses | Hypothesised Path | Path Coefficients | Path Coefficients (Bootstrap) | Pr > |t| | Testing results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Lifestyle → Attitudes | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1b | Consumer knowledge →Attitudes | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1c | Sensory properties → Attitudes | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.028 | Supported |

| H3a | Conditional value → Consumer choice behaviour | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3b | Epistemic value → Consumer choice behaviour | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.027 | Supported |

| H3c | Functional value → Consumer choice behaviour | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.064 | Not supported |

| H3d | Perceived value of meat in meals → Consumer choice behaviour | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3e | Emotional value → Consumer choice behaviour | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5a | Perceived info on package → Perceived Behavioural Control | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.149 | Not supported |

| H5b | Price → Perceived Behavioural Control | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1 | Attitudes →Purchase intention | -0.07 | -0.08 | 0.028 | Supported |

| H2 | Subjective norms →Purchase intention | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | Consumer choice behaviour→ Purchase intention | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.009 | Supported |

| H4 | Consumption habits → Purchase intention | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | Perceived behavioural control → Purchase intention | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.000 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).