Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Materials, Chemical Reagents, and Fairy Cake Ingredients

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Preparation, Extraction and Enrichment of Protein Hydrolysates from Chondrus crispus

2.4. Proximate Analysis

2.4.1. Ash Content

2.4.2. Protein Content

2.4.3. Lipid Content

2.4.4. Moisture Content

2.5. Colour Evaluation

2.6. Determination of pH and Water Activity (aW)

2.7. Technofunctional and Bioactive Properties

2.7.1. Water (WHC) and Oil Holding Capacity (OHC)

2.7.2. Emulsifying Activity and Emulsion Stability

2.7.3. Foaming Capacity and Stability

2.7.4. Mass Spectrometry in Tandem Analysis

2.7.5. Protein Identification

2.7.6. In silico Analysis of Identified Peptides to Predict Bioactivities

2.8. Preparation of Fairy Cakes

2.9. Cake Analysis

2.9.1. Baking loss (BL %)

2.9.2. Crust and Crumb Colour

2.9.3. Cake Density, Specific Volume and Volume Index

2.9.4. Moisture Content, Water Activity, and pH

2.9.5. Sensory Evaluation

3. Results

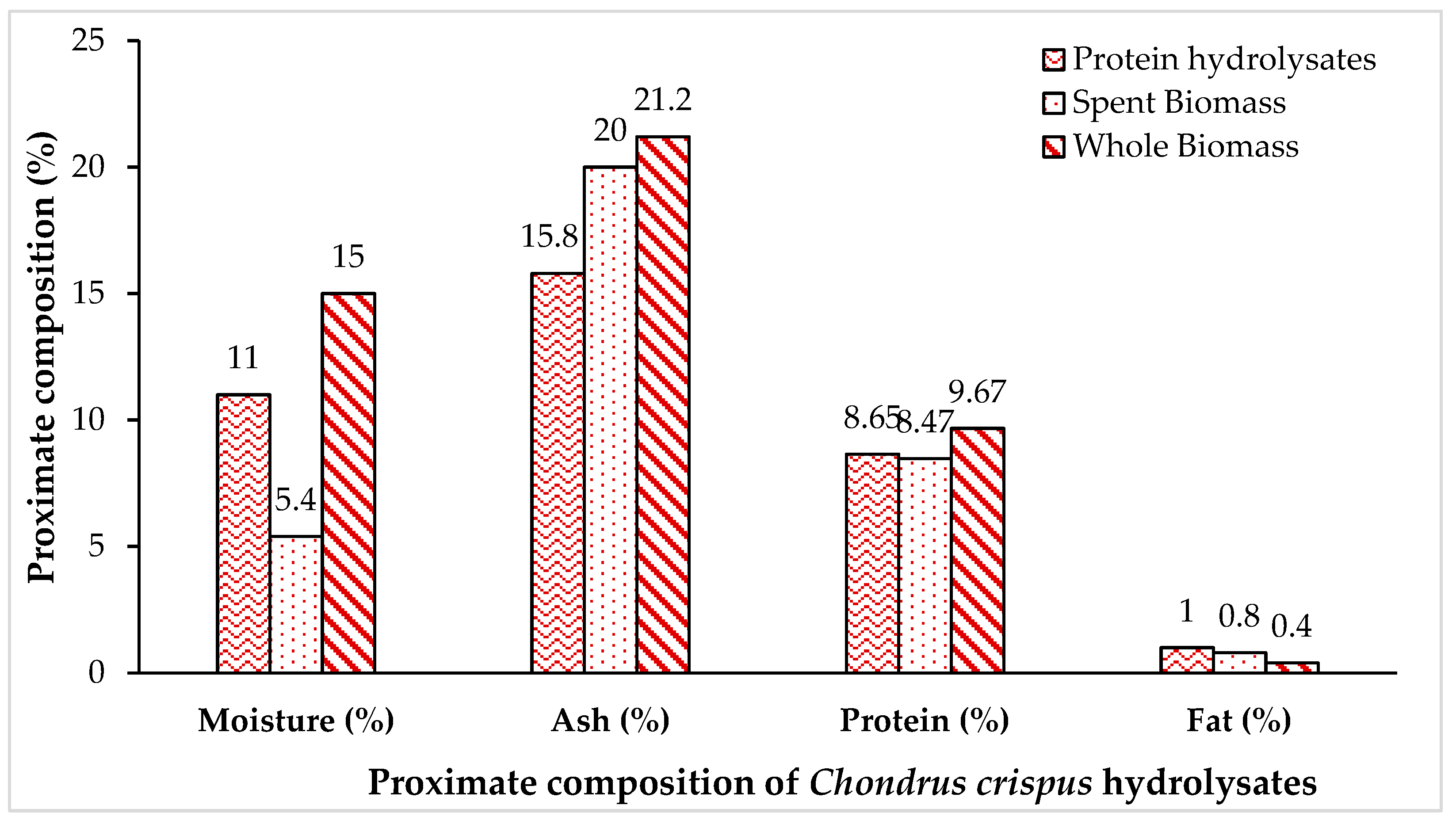

3.1. Extraction Yield and Proximate Composition of Protein Hydrolysates, Spent Biomass and Whole Biomass Fractions of Chondrus crispus

3.2. Colour of Protein Hydrolysates and Whole Biomass Fractions of Chondrus crispus

3.3. Water Activity and pH of Chondrus crispus Protein Hydrolysates

3.4. Water (WHC) and Oil Holding Capacity (OHC)

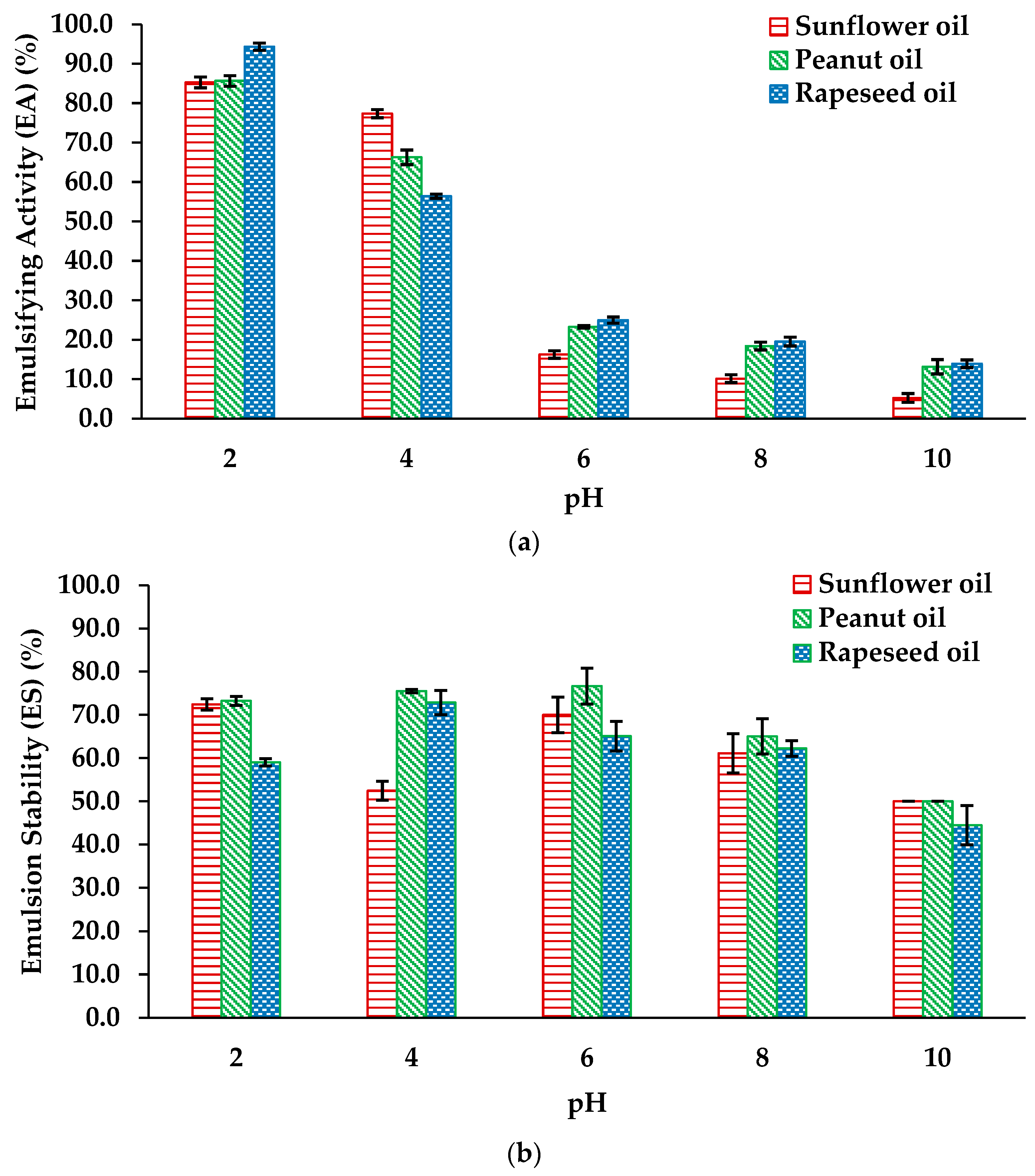

3.5. Emulsifying Activity (EA) and Emulsion Stability (ES)

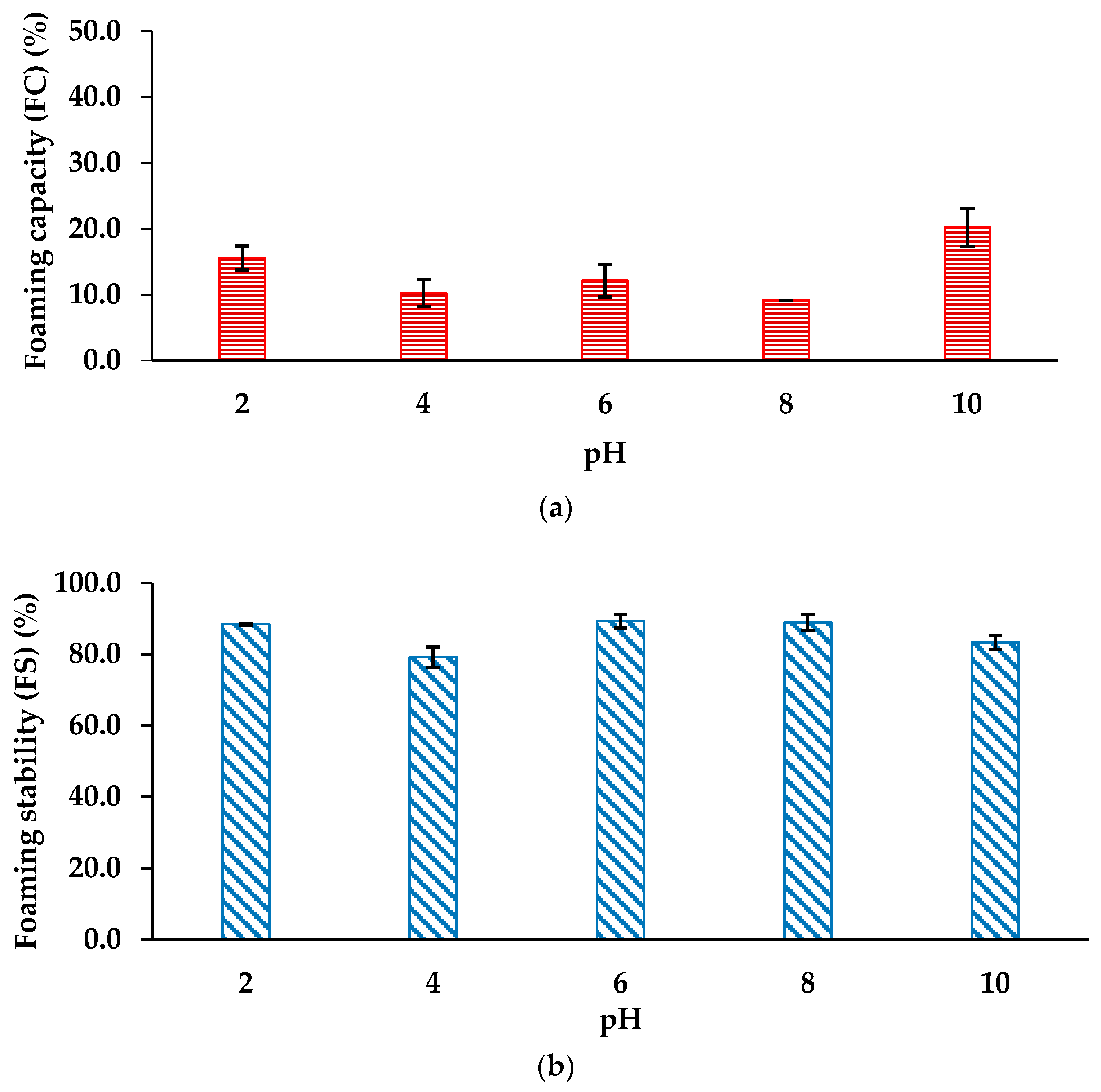

3.6. Foaming Capacity (FC) and Stability (FS)

3.7. Predicted Bioactivities of C. crispus Hydrolysate Peptides

3.8. Baking Loss and Colour of the Developed Vegan Cakes

3.9. Density, Specific Volume and Volume Index of the Developed Vegan Cakes

3.10. Moisture Content, Water Activity and pH of the Developed Vegan Cakes

3.11. Sensory evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. Outcome of Extraction Yield and Proximate Composition of Protein Hydrolysates, Spent Biomass and Whole Biomass Fractions of Chondrus crispus

4.2. Colour of Protein Hydrolysates and Whole Biomass Fractions of Chondrus crispus

4.3. Water activity and pH of Chondrus crispus protein hydrolysates

4.4. Water (WHC) and Oil Holding Capacity (OHC)

4.5. Emulsifying Activity (EA) and Emulsion Stability (ES)

4.6. Foaming Capacity (FC) and Foam Stability (FS)

4.7. Predicted Bioactivities

4.8. Baking Loss and Colour of the Developed Vegan Cakes

4.9. Density, Specific Volume and Volume Index of the Developed Vegan Cakes

4.10. Moisture Content, Water Activity and pH of the Developed Vegan Cakes

4.11. Sensory Evaluation

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHC | Water Holding Capacity |

| OHC | Oil Holding Capacity |

| EA | Emulsifying Activity |

| ES | Emulsion Stability |

| FC | Foaming Capacity |

| FS | Foaming Stability |

References

- Ogunwolu, S.O.; Henshaw, F.O.; Mock, H.P.; Santros, A.; Awon Orin, S.O. Functional properties of protein concentrates and isolates produced from cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.) nut. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 852–858. [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.H.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Han, I.K. Comparative efficacy of plant and animal protein sources on the growth performance, nutrient digestibility, morphology, and caecal microbiology of early-weaned pigs. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 18, 1285–1293. [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.H.; Cheung, P.C.; Ang, P.O. Nutritional evaluation of protein concentrates isolated from two red seaweeds: Hypnea charoides and Hypnea japonica in growing rats. Hydrobiologia 2004, 512, 271–278. [CrossRef]

- Slaski, R.J.; Franklin, P.T. A review of the status of the use and potential to use micro and macroalgae as commercially viable raw material sources for aquaculture diets. Report commissioned by Scottish Aquaculture Research Forum (SARF), 94 pp. Available online: http://www.sarf.org.uk/cms-assets/documents/29524-222388.sarf077.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Kumar, V.; Kaladharan, P. Amino acids in the seaweeds as an alternate source of protein for animal feed. Food Rev. Int. 1989, 5, 101–104.

- Fleurence, J. Seaweed proteins: biochemical, nutritional aspects, and potential uses. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1999, 10, 25–28. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Agregán, R.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Domínguez, R.; Franco, D.; Simal-Gándara, J. Proximate composition and nutritional value of three macroalgae: Ascophyllum nodosum, Fucus vesiculosus, and Bifurcaria bifurcata. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 360. [CrossRef]

- Gamero-Vega, G.; Palacios-Palacios, M.; Quitral, V. Nutritional composition and bioactive compounds of red seaweed: A mini-review. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 8, 431–436. [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Hori, K. Seaweed: Chemical composition and potential food uses. Food Rev. Int. 1989, 5, 101–104. [CrossRef]

- Pliego-Cortés, H.; Wijesekara, I.; Lang, M.; Bourgougnon, N.; Bedoux, G. Current knowledge and challenges in extraction, characterisation, and bioactivity of seaweed protein and seaweed-derived proteins. In Advances in Botanical Research, 1st ed.; Lang, M., Bourgougnon, N., Bedoux, G., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2020; Volume 95, pp. 289–326.

- Ohanenye, I.C.; Tsopmo, A.; Ejike, C.E.C.C.; Udenigwe, C.C. Germination as a bioprocess for enhancing the quality and nutritional prospects of legume proteins. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 101, 213–222. [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.H.; Cheung, P.C.K.; Ang, P.O. Nutritional evaluation of protein concentrates isolated from two red seaweeds: Hypnea charoides and Hypnea japonica in growing rats. In Asian Pacific Phycology in the 21st Century: Prospects and Challenges; Ang, P.O., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2004; pp. 577–582.

- Ragan, M.A.; Glombitza, K.W. Phlorotannins, Brown Algal Polyphenols. Prog. Phycol. Res. 1986, 4, 129–241.

- Fleurence, J.; Le Coeur, C.; Mabeau, S.; Maurice, M.; Landrein, A. Comparison of different extractive procedures for proteins from the edible seaweeds Ulva rigida and Ulva rotundata. J. Appl. Phycol. 1995, 7, 577–582. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.; Vilter, H. Extraction of proteins from material rich in anionic mucilages: Partition and fractionation of vanadate-dependent bromoperoxidases from the brown algae Laminaria digitata and L. saccharina in aqueous polymer two-phase system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991, 1073, 98–106. [CrossRef]

- Loomis, W.D.; Battaile, J. Plant phenolic compounds and the isolation of plant enzymes. Phytochemistry 1966, 5, 423–438. [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, Y.; Katsuragi, T.; Hashimoto, K. Proteins in three seaweeds: “Aosa” Ulva lactuca, “Arame” Eisenia bicyclis, and “Makusa” Gelidium amansii. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Sci. Fish. 1987, 53, 1051–1055.

- Abeer, M.M.; Trajkovic, S.; Brayden, D.J. Measuring the oral bioavailability of protein hydrolysates derived from food sources: A critical review of current bioassays. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 144, 112275. [CrossRef]

- Echave, J.; Fraga-Corral, M.; García-Oliveira, P.; Carpena, M.; Pereira, A.G.; Xiao, J.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gándara, J. Seaweed Protein Hydrolysates and Bioactive Peptides: Extraction, Purification, and Applications. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 500. [CrossRef]

- Mirzapour-Kouhdasht, A.; McClements, D.J.; Taghizadeh, M.S.; Niazi, A.; Garcia-Vaquero, M. Strategies for oral delivery of bioactive peptides with focus on debittering and masking. NPJ Sci. Food 2023, 7, 22. [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, L.; Weiss, J. Alternative Protein Sources as Technofunctional Food Ingredients. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 12, 93–117. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.M.; McLachlan, J. The life history of Chondrus crispus in culture. Can. J. Bot. 1972, 50, 1055–1060. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K. Seaweed: A Global History; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 2017.

- Rudtanatip, T.; Lynch, S.A.; Wongprasert, K.; Culloty, S.C. Assessment of the effects of sulfated polysaccharides extracted from the red seaweed Irish moss Chondrus crispus on the immune-stimulant activity in mussels Mytilus spp. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 75, 284–290. [CrossRef]

- Kulshreshtha, G.; Burlot, A.S.; Marty, C.; Critchley, A.; Hafting, J.; Bedoux, G.; Bourgougnon, N. Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactive material from Chondrus crispus and Codium fragile and its effect on herpes simplex virus (HSV-1). Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 558–578. [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists International (AOAC). Official Methods of Analysis of Association of Official Analytical Chemists International; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; 1, p. 870.

- López-Hortas, L., Caleja, C., Pinela, J., Petrović, J., Soković, M., Ferreira, I.C.F.R., To M.D. Domínguez, H., Pereira, E., Barros, L. Comparative evaluation of physicochemical profile and bioactive properties of red edible seaweed Chondrus crispus subjected to different drying methods, Food Chemistry, 383, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Samarakoon, Y.M.; Gunawardena, N. Knowledge and self-reported practices regarding leptospirosis among adolescent school children in a highly endemic rural area in Sri Lanka. Rural Remote Health 2013, 13, 8–19.

- Purcell, D., Packer, M. A., & Hayes, M. Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitory activity of protein hydrolysates generated from the macroalga Laminaria digitata (Hudson) J.V. Lamouroux 1813. Foods 2022, 11, 1792. [CrossRef]

- Bencini, M. C. Functional properties of drum-dried chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) flours. J. Food Sci. 1986, 51, 1518–1521. [CrossRef]

- Naczk, M., Diosady, L. L., & Rubin, L. J. Functional properties of canola meals produced by a two-phase solvent extraction system. J. Food Sci. 1985, 50, 1685–1688. [CrossRef]

- Poole, S., West, S. I., & Walters, C. L. Protein–protein interactions: Their importance in the foaming of heterogeneous protein systems. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1984, 35, 701–711. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Aurino, E.; Mora, L. Generation of Bioactive Peptides from Porphyridium sp. and Assessment of Their Potential for Use in the Prevention of Hypertension, Inflammation and Pain. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 422. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.; Naik, A.; Mora, L.; Iñarra, B.; Ibarruri, J.; Bald, C.; Cariou, T.; Reid, D.; Gallagher, M.; Dragøy, R.; et al. Generation, Characterisation and Identification of Bioactive Peptides from Mesopelagic Fish Protein Hydrolysates Using In Silico and In Vitro Approaches. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 297. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, D., Packer, M. A., Hayes, M. Identification of Bioactive Peptides from a Laminaria digitata Protein Hydrolysate Using In Silico and In Vitro Methods to Identify Angiotensin-1-Converting Enzyme (ACE-1) Inhibitory Peptides. Mar Drugs. 2023 Jan 27;21(2):90. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khatun MS, Hasan MM, Kurata H. PreAIP: Computational Prediction of Anti-inflammatory Peptides by Integrating Multiple Complementary Features. Front Genet. 2019 Mar 5;10:129. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qi, L., Du, J., Sun, Y., Xiong, Y., Zhao, X., Pan, D, Zhi, Y, Dang, Y., Gao, X. Umami-MRNN: Deep learning-based prediction of umami peptide using RNN and MLP, Food Chemistry, 405, Part A, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Huang, J., He, B. AntiDMPpred: a web service for identifying anti-diabetic peptides. PeerJ. 2022 Jun 14;10:e13581. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Syed, S. J., Gadhe, K. S., & Shaikh, R. P. Studies on quality evaluation of oat milk. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 2275–2277.

- Lin, M., Tay, S. H., Yang, H., Yang, B., & Li, H. Replacement of eggs with soybean protein isolates and polysaccharides to prepare yellow cakes suitable for vegetarians. Food Chem. 2017a, 229, 663–673. [CrossRef]

- Baixauli, R.; Salvador, A.; Fiszman, S. M. Textural and colour changes during storage and sensory shelf life of muffins containing resistant starch. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 226, 523–530. [CrossRef]

- American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC). Approved Methods of the AACC. Methods 10–91; AACC: St Paul, MN, USA, 1983.

- Milner, L., Kerry, J. P., O'Sullivan, M. G., & Gallagher, E. Physical, textural, and sensory characteristics of reduced sucrose cakes incorporated with clean-label sugar-replacing alternative ingredients. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 59, 102235. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y. Y., Lin, K. H., & Chen, Y. H. Batter and product quality of eggless cakes made of different types of flours and gums. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 2959–2968. [CrossRef]

- Aziah, A. N., & Komathi, C. A. Physicochemical and functional properties of peeled and unpeeled pumpkin flour. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, S328–S333. [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, L., Sirois, M., & Tamigneaux, É. Evaluation of the in vitro biological activity of protein hydrolysates of the edible red alga, Palmaria palmata (Dulse), harvested from the Gaspe coast and cultivated in tanks. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 3101–3115. [CrossRef]

- Habibie, A., Raharjo, T. J., Swasono, R. D., & Retnaningrum, E. Antibacterial activity of active peptide from marine macroalgae Chondrus crispus protein hydrolysate against Staphylococcus aureus. Pharmacia 2023, 70, 983–992. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E. F., et al. Seaweeds from the Portuguese coast as a source of proteinaceous material: Total and free amino acid composition profile. Food Chem. 2018, 269, 264–275. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Aguilar, D. M.; Ortega-Regules, A. E.; Lozada-Ramírez, J. D.; Pérez-Pérez, M. C. I.; Vernon-Carter, E. J.; Welti-Chanes, J; Color and chemical stability of spray-dried blueberry extract using mesquite gum as wall material. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 889–894. [CrossRef]

- Combet, S.; Pieper, J.; Coneggo, F.; Ambroise, J. P.; Bellissent-Funel, M. C.; Zanotti, J. M.; Coupling of laser excitation and inelastic neutron scattering: Attempt to probe the dynamics of light-induced C-phycocyanin dynamics. Eur. Biophys. J. 2008, 37, 693–700. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T., Zhang, J. P., Chang, W. R., & Liang, D. C. Crystal structure of R-phycocyanin and possible energy transfer pathways in the phycobilisome. Biophys. J. 2001, 81, 1171–1179. [CrossRef]

- Murray, J. W., Maghlaoui, K., & Barber, J. The structure of allophycocyanin from Thermosynechococcus elongatus at 3.5 Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2007, 63, 998–1002. [CrossRef]

- Shi, F., Qin, S., & Wang, Y. C. The coevolution of phycobilisomes: Molecular structure adapting to functional evolution. Int. J. Genomics 2011, 2011, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Básaca-Loya, G., Valdez, M., Enríquez-Guevara, E., Gutierrez-Millán, L., & Burboa, M. Extraction and purification of B-phycoerythrin from the red microalga Rhodosorus marinus. Cienc. Mar. 2009, 35, 359–368. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. K.; Shrivastav, A.; Maurya, R. R.; Patidar, S. K.; Haldar, S.; Mishra, S. Effect of light quality on the C-phycoerythrin production in marine cyanobacteria Pseudanabaena sp. isolated from Gujarat coast, India. Protein Expr. Purif. 2012, 81, 5–10. [CrossRef]

- Sablani, S., Kasapis, S., & Rahman, M. Evaluating water activity and glass transition concepts for food stability. J. Food Eng. 2007, 78, 266–271. [CrossRef]

- Hemker, A. K., Nguyen, L. T., Karwe, M., & Salvi, D. Effects of pressure-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis on functional and bioactive properties of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) by-product protein hydrolysates. LWT 2020, 122, 109003. [CrossRef]

- Suresh Kumar, K., Ganesan, K., Selvaraj, K., & Subba Rao, P. V. Studies on the functional properties of protein concentrate of Kappaphycus alvarezii (Doty) Doty – An edible seaweed. Food Chem. 2014, 153, 353–360. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., Ahmedna, M., & Goktepe, I. Peanut protein concentrate: Production and functional properties as affected by processing. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 121–129. [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J. Physicochemical and pH-dependent functional properties of proteins isolated from eight traditional Chinese beans. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 112, 106288. [CrossRef]

- Gharehbeglou, P.; Sarabandi, K.; Akbarbaglu, Z. Insights into enzymatic hydrolysis: Exploring effects on antioxidant and functional properties of bioactive peptides from chlorella proteins. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 10, 101129. [CrossRef]

- Akbarbaglu, Z.; Ayaseh, A.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Sarabandi, K. Techno-functional, biological and structural properties of Spirulina platensis peptides from different proteases. Algal Res. 2022, 66, 102755. [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, N. A.; Halim, N. R. A.; Sarbon, N. M. pH levels effect on functional properties of different molecular weight eel (Monopterus sp.) protein hydrolysate. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 4608–4614. [CrossRef]

- Chandi, G. K.; Sogi, D. Functional properties of rice bran protein concentrates. J. Food Eng. 2007, 79, 592–597. [CrossRef]

- Seena, S.; Sridhar, K. Physicochemical, functional and cooking properties of underexplored legumes, Canavalia of the southwest coast of India. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 803–814. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, M.; Waterhouse, G. I.; Sun, W. Soybean protein isolate hydrolysates-liposomes interactions under oxidation: Mechanistic insights into system stability. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 112, 106336. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Qiao, Y.; Shi, B.; Dia, V. P. Alcalase and bromelain hydrolysis affected physicochemical and functional properties and biological activities of legume proteins. Food Struct. 2021, 27, 100178. [CrossRef]

- Pires, J. B.; Dos Santos, F. N.; de Lima Costa, I. H.; Kringel, D. H.; da Rosa Zavareze, E.; Dias, A. R. G. Essential oil encapsulation by electrospinning and electrospraying using food proteins: A review. Food Res. Int. 2023, 170, 112970. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulou, K., Keppler, J.K., van der Goot ,A. J. Functionality of Ingredients and Additives in Plant-Based Meat Analogues. Foods. 2021 Mar 12;10(3):600. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nalinanon, S.; Benjakul, S.; Kishimura, H.; Shahidi, F. Functionalities and antioxidant properties of protein hydrolysates from the muscle of ornate threadfin bream treated with pepsin from skipjack tuna. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1354–1362. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Xie, H.; Liu, Z.; Rakariyatham, K.; Yu, C.; Shahidi, F.; Zhou, D. Antioxidant activity and functional properties of Alcalase-hydrolyzed scallop protein hydrolysate and its role in the inhibition of cytotoxicity in vitro. Food Chem. 2021, 344, 128566. [CrossRef]

- Lawal, O. S. Functionality of African locust bean (Parkia biglobossa) protein isolate: Effects of pH, ionic strength and various protein concentrations. Food Chem. 2004, 86, 345. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S. M.; Assadpoor, E.; He, Y.; Bhandari, B. Re-coalescence of emulsion droplets during high-energy emulsification. Food Hydrocoll. 2008, 22, 1191–1202. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yin, F.; Zhan, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, B.; Nakamura, Y.; Wang, J.; Antioxidative effect of Chlorella pyrenoidosa protein hydrolysates and their application in krill oil-in-water emulsions. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 345. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Soltanzadeh, M.; Ebrahimi, A. R.; Hamishehkar, H. Spirulina platensis protein hydrolysates: Techno-functional, nutritional and antioxidant properties. Algal Res. 2022, 65, 102739. [CrossRef]

- Sathe, S.; Deshpande, S.; Salunkhe, D. Functional properties of lupin seed (Lupinus mutabilis) proteins and protein concentrates. J. Food Sci. 1982, 47, 491–497. [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.; Zayas, J. Emulsifying capacity and emulsion stability of milk proteins and corn germ protein flour. J. Food Sci. 1991, 56, 1216–1218. [CrossRef]

- Chau, C.-F.; Cheung, P. C.; Wong, Y.-S. Functional properties of protein concentrates from three Chinese indigenous legume seeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 2500–2503. [CrossRef]

- Ragab, D. M.; Babiker, E. E.; Eltinay, A. H. Fractionation, solubility and functional properties of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) proteins as affected by pH and/or salt concentration. Food Chem. 2004, 84, 207–214. [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, G., Karuppiah, S. K. & Subba Rao, P. V. Salt- and pH-induced functional changes in protein concentrate of edible green seaweed Enteromorpha species. Fish Sci. 2012, 78, 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Aluko, R.; Yada, R. Structure-function relationships of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) globulin isolate: Influence of pH and NaCl on physicochemical and functional properties. Food Chem. 1995, 53, 259–265. [CrossRef]

- Kinsella, J. E.; Damodaran, S.; German, B. Physicochemical and functional properties of oilseed proteins with emphasis on soy proteins. In New Protein Foods; Alschul, A. M., Wilke, H. L., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 107–179.

- Yamaguchi, N., Kawaguchi, K., Yamamoto, N. Study of the mechanism of antihypertensive peptides VPP and IPP in spontaneously hypertensive rats by DNA microarray analysis. European Journal of Pharmacology,2009, 620, 71-77.

- Zlotek, U., Jakubczyk, A., Tkaczyk, K., Cwiek, P., Baraniak, B., Lewicki, S. Characterisation of new peptides GQLGEHGGAGMG, GEHGGAGMGGGQFQPV, EQGFLPGPEESG, RLARAGLAQ, YGNPVGGVG, and GNPVGGVGHGTTGT as inhibitors of enzymes involved in Metabolic Syndrome and Antimicrobial potential. Molecules, 2020, 27, 2492. doi.10.3390/molecules25112492.

- Silva, P. G.; Kalschne, D. L.; Salvati, D.; Bona, E.; Rodrigues, A. C. Aquafaba powder, lentil protein and citric acid as egg replacer in gluten-free cake: A model approach. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100188. [CrossRef]

- Aslan, M.; Ertaş, N. Possibility of using 'chickpea aquafaba' as egg replacer in traditional cake formulation. Harran Tarım ve Gıda Bilimleri Dergisi 2020, 24, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Majzoobi, M.; Ghiasi, F.; Habibi, M.; Hedayati, S.; Farahnaky, A. Influence of soy protein isolate on the quality of batter and sponge cake. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2014, 38, 1164–1170. [CrossRef]

- Jarpa-Parra, M.; Bamdad, F.; Tian, Z.; Temelli, F.; Zeng, H.; Shaheen, N.; Chen, L. Quality characteristics of angel food cake and muffin using lentil protein as egg/milk replacer. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 1604–1613. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Salami, M.; Yarmand, M.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; McClements, D. J. Production and characterization of functional bakery goods enriched with bioactive peptides obtained from enzymatic hydrolysis of lentil protein. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 3402–3409. [CrossRef]

- Gani, A.; Wani, S. M.; Masoodi, F. A.; Hameed, G.; Ashraf, Z. Effect of whey and casein protein hydrolysates on rheological, textural and sensory properties of cookies. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 5718–5726. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, D. A.; Shehita, H. A.; Soliman, H. R. E. S. Development of eggless cake physical, nutritional and sensory attributes for vegetarians by using wholemeal chia (Salvia hispanica L.) flour. Middle East J. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 313–329. [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, N. F.; Tehrani, M. M. Influence of different emulsifiers on characteristics of eggless cake containing soymilk: Modelling of physical and sensory properties by mixture experimental design. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 1697–1710. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Tay, S. H.; Yang, H.; Yang, B.; Li, H. Development of eggless cakes suitable for lacto-vegetarians using isolated pea proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2017b, 69, 440–449. [CrossRef]

- Gray, J. A.; Bemiller, J. N. Bread staling: Molecular basis and control. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2003, 2, 1–21. [ 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00011.x].

- Wilderjans, E.; Luyts, A.; Brijs, K.; Delcour, J. A. Ingredient functionality in batter type cake making. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 30, 6–15. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J. P.; Kaur, A.; Singh, N. Development of eggless gluten-free rice muffins utilizing black carrot dietary fibre concentrate and xanthan gum. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1269–1278. [CrossRef]

| Ingredients | Quantity (g or ml) |

| Oat milk | 150 ml |

| Self-raising flour | 150 g |

| Caster sugar | 150 g |

| Rapeseed oil | 60 ml |

| Salt | ½ Pinch |

| Baking powder | Pinch |

| Vanilla extract | ½ tsp |

| Ingredients | Quantity (g or ml) |

| Butter | 150 g |

| Self-raising flour | 150 g |

| Caster sugar | 150 g |

| Eggs | 2 |

| Vanilla extract | ½ tsp |

| Quality | Standard For Evaluation | Score |

| Appearance | Neat shape, flat surface and no wrinkle, collapse and crack | 8 – 10 |

| Neat shape and surface with minor wrinkle collapse or crack | 5 – 7 | |

| Irregular shape and surface with evident wrinkle, collapse and crack | 0 – 4 | |

| Colour | Gold-yellow surface, milk yellow inside, uniform colour and no spots | 8 – 10 |

| Yellow surface, light yellow inside, uniform colour and a few spots | 5 – 7 | |

| Uneven colour and many spots | 0 – 4 | |

| Odour | Pure fragrance, no peculiar smell | 8 – 10 |

| A little fragrance, no peculiar smell | 5 – 7 | |

| No fragrance, with a peculiar smell | 0 – 4 | |

| Texture | Elastic, uniform honeycomb structure and even pore size | 8 – 10 |

| Elastic, honeycomb structure with some large pore size | 5 – 7 | |

| Non-uniform honeycomb structure with plenty of large holes | 0 – 4 |

| Biomass type | Seaweed |

| Chondrus crispus | |

| Whole biomass | 50 ± 0 g |

| Supernatant (protein hydrolysates) | 9.71 ± 0.23 g |

| Protein hydrolysates yield (%) | 19.42 ± 0.46 % |

| Colour coordinates | Whole biomass | Protein hydrolysates |

| L* value | 51.02 ± 0.85 | 68.35 ± 0.25 |

| a* (red to green) | 3.08 ± 0.39 | 4.44 ± 0.05 |

| b* (yellow to blue) | 6.37 ± 0.56 | 11.60 ± 0.10 |

| C* | 7.19 ± 0.43 | 12.14 ± 0.11 |

| h° | 62.89 ± 4.41 | 69.23 ± 0.17 |

| ∆E* ab | 18.34 | |

| Water activity (aW) | 0.45 ± 0.005 |

| pH | 6.82 ± 0.01 |

| (g of water or oil/g of hydrolysate) | ||

| Water Holding Capacity (WHC) | 10.145 ± 0.221 | |

|

Oil Holding Capacity (OHC) |

Sunflower oil | 9.226 ± 0.084 |

| Peanut oil | 9.175 ± 0.135 | |

| Rapeseed oil | 9.169 ± 0.137 |

| Peptide Sequence | Protein & accession number | Peptide Ranker Score | Anti-inflammatory prediction with PreAIP RF (combined values) | Anti-diabetic potential prediction with AntiDMPpred (tp 0.6) | Umami prediction with Umami-MRNN | Novelity (found in BIOPEP-UWM) |

| APPPPPPAPF | Uncharacterized protein (R7QQW5_CHOCR) | 0.97 | Negative AIP (0.292) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| DDDPFGPF | Tyrosine-protein kinase ephrin type A/B receptor-like domain-containing protein (R7QEH3_CHOCR) | 0.959 | Negative AIP (0.299) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| VDPSPWPF | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 3 (COX3_CHOCR) | 0.945 | Low confidence AIP (0.376) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| GMPSDDPFPF | Malate dehydrogenase (R7QPY8_CHOCR) | 0.942 | Low confidence AIP (0.372) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 39.25773mmol/L | Novel |

| SIPDGWMGL | Phosphoglycerate kinase (Q8GVE6_CHOCR) | 0.939 | Medium confidence AIP (0.443) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 31.829782mmol/L | Novel |

| FDPVFIM | Potential copper-zinc superoxide dismutase, CuZn SOD2 R7QRY5_CHOCR) | 0.933 | Medium confidence AIP (0.436) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| SADDDPFGPF | Tyrosine-protein kinase ephrin type A/B receptor-like domain-containing protein (R7QEH3_CHOCR) | 0.932 | Negative AIP (0.299) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 27.236626mmol/L | Novel |

| GGGAPFFPVA | SMP-30/Gluconolactonase/LRE-like region domain-containing protein (R7QCK1_CHOCR) | 0.93 | Low confidence AIP (0.367) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| GPGPGPGPGPGPGPV | Hint domain-containing protein (R7QIA6_CHOCR) | 0.926 | Negative AIP (0.241) | Predicted to be anti-diabetic | umami, predicted threshold: 15.696608mmol/L | Novel |

| VGPPPPPPPPP | C-CAP/cofactor C-like domain-containing protein (R7QP74_CHOCR) | 0.923 | Negative AIP (0.342) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| AMPPFPNPY | Uncharacterized protein (R7QQW5_CHOCR) | 0.916 | Medium confidence AIP (0.410) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| ADMGGMGF | NAD-dependent sugar epimerase (R7QUS9_CHOCR) | 0.913 | Medium confidence AIP (0.434) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 8.370863mmol/L | Novel |

| SPPPPVDPF | Acetohydroxy-acid reductoisomerase (R7QNL4_CHOCR) | 0.912 | Negative AIP (0.317) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| AGPGPGPGPGPGPGPV | Hint domain-containing protein (R7QIA6_CHOCR) | 0.911 | Medium confidence AIP (0.444) | Predicted to be anti-diabetic | umami, predicted threshold: 22.584654mmol/L | Novel |

| DDFDFNPL | catalase (R7QFJ3_CHOCR) | 0.91 | Low confidence AIP (0.349) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| FAGGPKIPF | Ascorbate Peroxidase, APX1(R7QH61_CHOCR) | 0.906 | Medium confidence AIP (0.392) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 38.71417mmol/L | Novel |

| VGGDPSFGPF | NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase domain-containing protein (R7Q496_CHOCR) | 0.9 | Low confidence AIP (0.369) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 26.573849mmol/L | Novel |

| GIPDEWMGL | Phosphoglycerate kinase (Q8GVE6_CHOCR) | 0.9 | High confidence AIP (0.469) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 36.3166mmol/L | Novel |

| FDPVFIMN | Potential copper-zinc superoxide dismutase, CuZn SOD2 (R7QRY5_CHOCR) | 0.9 | Medium confidence AIP (0.436) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| VLPSLPFM | Animal heme peroxidase homologue (R7QJ77_CHOCR) | 0.89 | High confidence AIP (0.478) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 34.225975mmol/L | Novel |

| SSPQFGFPT | SMP-30/Gluconolactonase/LRE-like region domain-containing protein (R7QCK1_CHOCR) | 0.89 | Negative AIP (0.335) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 36.78789mmol/L | Novel |

| ALEPPPPVGPPGL | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase (R7QGF5_CHOCR) | 0.89 | Medium confidence AIP (0.402) | Predicted to be anti-diabetic | umami, predicted threshold: 26.183607mmol/L | Novel |

| GVSAPFDPF | Translation initiation factor eIF1 (R7QJC0_CHOCR) | 0.88 | Low confidence AIP (0.363) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 33.65273mmol/L | Novel |

| YAMPPYAF | Photosystem I P700 chlorophyll a apoprotein A2 (M5DES3_CHOCR) | 0.88 | Low confidence AIP (0.379) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| SPDMPGYVGF | Uncharacterized protein (R7QQW5_CHOCR) | 0.88 | Low confidence AIP (0.364) | No | non-umami | Novel |

| DSDSDLFFG | Gal-2,6-Sulfurylases II (R7Q2Y4_CHOCR) | 0.88 | Low confidence AIP (0.361) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 29.827625mmol/L | Novel |

| GGPAGGGPAGGDAGLA | Transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase (Valosin-containing protein), (R7QAA8_CHOCR) | 0.87 | High confidence AIP (0.480) | Predicted to be anti-diabetic | umami, predicted threshold: 13.955362mmol/L | Novel |

| AQVPPLPNMPRMPA | Prohibitin (R7QRM0_CHOCR) | 0.87 | High confidence AIP (0.478) | Predicted to be anti-diabetic | umami, predicted threshold: 37.8484mmol/L | Novel |

| DSDSDLFFGR | Gal-2,6-Sulfurylases II (R7Q2Y4_CHOCR) | 0.87 | Low confidence AIP (0.384) | No | umami, predicted threshold: 8.039184mmol/L | Novel |

| Samples | Baking loss (%) | Colour characteristics | ||||

| L* | a* | b* | ∆E*ab | |||

| Control cakes | 8.92 ± 0.63 | Crust | 49.50 ± 0.33 | 17.52 ± 0.15 | 37.54 ± 0.22 | Crust (10.16)Crumb (11.61) |

| Crumb | 68.02 ± 0.42 | 2.70 ± 0.09 | 38.03 ± 0.21 | |||

| 11.72 ± 0.13 | Crust | 56.23 ± 0.22 | 10.03 ± 0.26 | 36.17 ± 0.36 | ||

| Vegan cakes | Crumb | 59.93 ± 0.37 | 3.25 ± 0.06 | 29.71 ± 0.30 | ||

| Cake density (g/cm3) | Specific volume (cm3/g) | Volume index (cm) | |

| Control cake | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 1.95 ± 0.02 | 9.66 ± 0.13 |

| Vegan cake | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 1.66 ± 0.04 | 9.21 ± 0.18 |

| Days | Moisture content (%) | Water activity (aW) | pH | |||

| Control | Vegan | Control | Vegan | Control | Vegan | |

| 0 | 26.03 ± 0.41 | 29.34 ± 0.18 | 0.810 ± 0.001 | 0.754 ± 0.004 | 7.84 ± 0.01 | 7.25 ± 0.00 |

| 1 | 24.63 ± 0.60 | 28.15 ± 0.13 | 0.817 ± 0.003 | 0.759 ± 0.005 | 7.85 ± 0.02 | 7.30 ± 0.01 |

| 2 | 24.06 ± 0.08 | 27.20 ± 0.07 | 0.822 ± 0.003 | 0.762 ± 0.005 | 7.89 ± 0.00 | 7.31 ± 0.01 |

| Days | Appearance | Colour | Odour | Texture |

| Control cake | 9.33 ± 0.22 | 9.78 ± 0.14 | 10.00 ± 0.00 | 9.67 ± 0.16 |

| Vegan cake | 8.67 ± 0.22 | 8.56 ± 0.23 | 7.56 ± 0.17 | 7.67 ± 0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).