1. Introduction

To mitigate the impact of carbon emissions on the global climate, renewable energy sources such as hydropower, wind power, and solar power have gained significant attention and are increasingly integral to the power grid. Among these, hydropower stands out due to its low cost, high returns, mature technology, and potential for large-scale development, thus occupying a substantial share within the grid. In contrast, intermittent energy sources like wind and solar power face challenges in ensuring consistent power quality due to seasonal variations and the day-night cycle, which can affect grid stability. Pumped storage power stations are particularly valuable as they can serve as a power source during peak demand periods while also absorbing excess energy from the grid during low demand periods, thereby providing flexibility to meet grid requirements and warranting further research [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

The efficient and stable operation of the pump-turbine, as a critical component of pumped storage power stations, is essential for ensuring the safe and effective functioning of the facility. With advancements in the hydropower sector, pumped storage power stations are increasingly evolving towards high head and high speed operations, resulting in frequent occurrences of cavitation phenomena affecting the units. Numerous studies indicate that cavitation has a more significant impact on the operational conditions of pumps than on those of turbines, the cavitation performance of pump-turbine under pump conditions is deemed more critical than under turbine conditions [

7,

8,

9],consequently, it is essential to conduct in-depth research on the cavitation flow field specific to pump-turbine operating in pump mode. Li [

10] employed numerical simulation techniques to investigate the cavitation characteristics of pump-turbine runners in high-head regions under varying flow rates and heads for both pump and turbine conditions. Zhang [

9] conducted a study on the cavitation flow field and performance of pump-turbine operating conditions, determining the critical cavitation bubble volume fraction, the findings indicate that varying flow rates influence the location of bubble formation at the inlet. Tao conducted a study on the cavitation behavior of pump-turbine under various operating conditions, the research compared the inception and critical cavitation points across different scenarios, concluding that utilizing an initial cavitation standard allows for a more timely detection of cavitation bubbles, thereby facilitating the early mitigation of cavitation phenomena.

Cavitation can also lead to adverse phenomena such as vibrations and noise within the machinery, which may result in a reduction of mechanical lifespan, a decrease in maintenance intervals, and an increase in the frequency of unit start-ups and shut-downs, ultimately affecting the stability of the power station. Hao [

11] conducted a study on the impact of different impeller tip clearances in the cavitating flow field of mixed-flow pumps operating under pump conditions, specifically focusing on the radial forces acting on the shaft in pumped storage units. The findings indicate that when the apex gap is asymmetrical, the cavitation performance is at its lowest. In this scenario, the amplitude of the radial force increases with the intensification of cavitation, and due to the asymmetric distribution of the cavitation region, the direction of the radial force also varies as cavitation worsens. Liu [

7] research examined the impact of cavitation on the radial forces experienced by water pump turbines under pumping conditions. The study revealed that as cavitation intensified, the number of cavitation bubbles on the blade surfaces increased, resulting in a reduction of blade load and a decrease in the regularity of pressure fluctuations. This led to significant alternation in radial forces, contributing to the emergence of fatigue cracks in high-stress areas of the blades. However, due to the periodic symmetrical structure of the guide vanes and the runner, the distribution of radial forces remained relatively uniform.

The presence of unsteady vortex structures in cavitating flow fields is a significant factor contributing to the decline in the performance of hydraulic machines. Meng [

12] investigated the dynamic characteristics of cavitation vortices within centrifugal pumps using the vorticity transport method. The findings indicated that during severe cavitation conditions, vortex structures were generated at the trailing edge of the cavitation region within the flow passage. Wu [

13] employed numerical simulation techniques to analyze the two-dimensional vortex structures based on velocity components, utilizing a novel Omega vortex identification method proposed by Zhang [

14] to extract vorticity from the pump blade surfaces. The results demonstrated that as the cavitation margin decreased, the volume of vapor bubbles increased, leading to a progressively turbulent flow field characterized by localized vortices. These vortices detached from the blade surfaces as the cavities rolled up, and the vorticity transport method effectively captured large-scale regions of high vorticity. Ruan [

15] examined the cavitation characteristics of water pumps and turbines under various flow conditions. The results revealed that under low flow conditions, severe cavitation on the suction side of the blade's low-pressure edge caused flow separation, disrupting the flow field structure and resulting in extensive flow detachment and vortex formation, ultimately reducing the efficiency of the water pump turbine.

To determine the regions and magnitude of energy dissipation, Gong [

16] was the first to incorporate entropy production theory into the analysis of flow fields. Li [

17] utilized this theory to investigate the energy loss characteristics of the flow field when a pump-turbine operates in the hump region under pump conditions. Furthermore, Yu [

18] employed the entropy production method to conduct an in-depth study of the energy dissipation characteristics of cavitating flow within micro-pumps, establishing the interrelationship among cavitation, vorticity, and entropy production. The findings indicate that during the development of cavitation, hydraulic losses occur due to the mass exchange between the gas and liquid phases, as well as momentum transfer among the fluids.

Traditional methods often struggle to capture the dominant characteristics of unsteady flow fields. Consequently, to effectively manage complex flow field data, numerous reduced-order models have been proposed by researchers in recent years. The most commonly utilized techniques include Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) [

19] and Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD) [

20].

The POD method partitions complex flow fields into a series of spatial orthogonal modes, ranking them based on their energy content, which is indicated by their eigenvalues, thereby emphasizing the dominant flow structures. POD is widely utilized in flow field analysis due to its capability to accurately capture coherent structures within the flow and significantly simplify the flow field representation. Lu [

21] applied the POD technique to decompose and reconstruct the flow field in the tongue region of a centrifugal pump, establishing a relationship between pressure fluctuations and the primary flow structures. Additionally, Yang [

22,

23] and colleagues employed the POD method to investigate the evolution frequency of the stall regions in the flow field of the guide vane area when the pump operates in the hump region.

In contrast to the Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) method, the Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD) technique allows for the decomposition of the flow field into a series of distinct frequency modes, thereby facilitating the observation of flow structures evolving at various frequencies. Xie [

24] employed the DMD method to analyze the velocity field of the cavitating flow around a hydrofoil, revealing that the second-order mode corresponds to the frequency of bubble shedding, while the third and fourth-order modes exhibit frequencies that are harmonics of the second-order mode. In the context of rotating fluid machinery, Lu [

25] utilized wavelet transform to analyze pressure fluctuation data at the inlet and outlet of a centrifugal pump. By integrating DMD with numerical simulations of the internal pressure field, the study elucidated the impact of cavitation on pressure fluctuations. The findings indicate that the centrifugal pump exhibits complex pressure fluctuation characteristics dominated by various frequencies, with the blades playing a significant role in influencing these frequencies throughout the flow field.

In summary, there is a limited amount of research focused on the unsteady characteristics of cavitation vortices and energy loss phenomena caused by the dynamic and static flow fields formed by the impeller and guide vane regions in low flow conditions of pump-turbine. Therefore, this study employs Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) and Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD) methods to analyze the unsteady characteristics of cavitation vortices in low flow conditions of pump-turbine, aiming to investigate the distribution and evolution patterns of these vortices.

2. Research Object

2.1. Pump Turbine Parameters

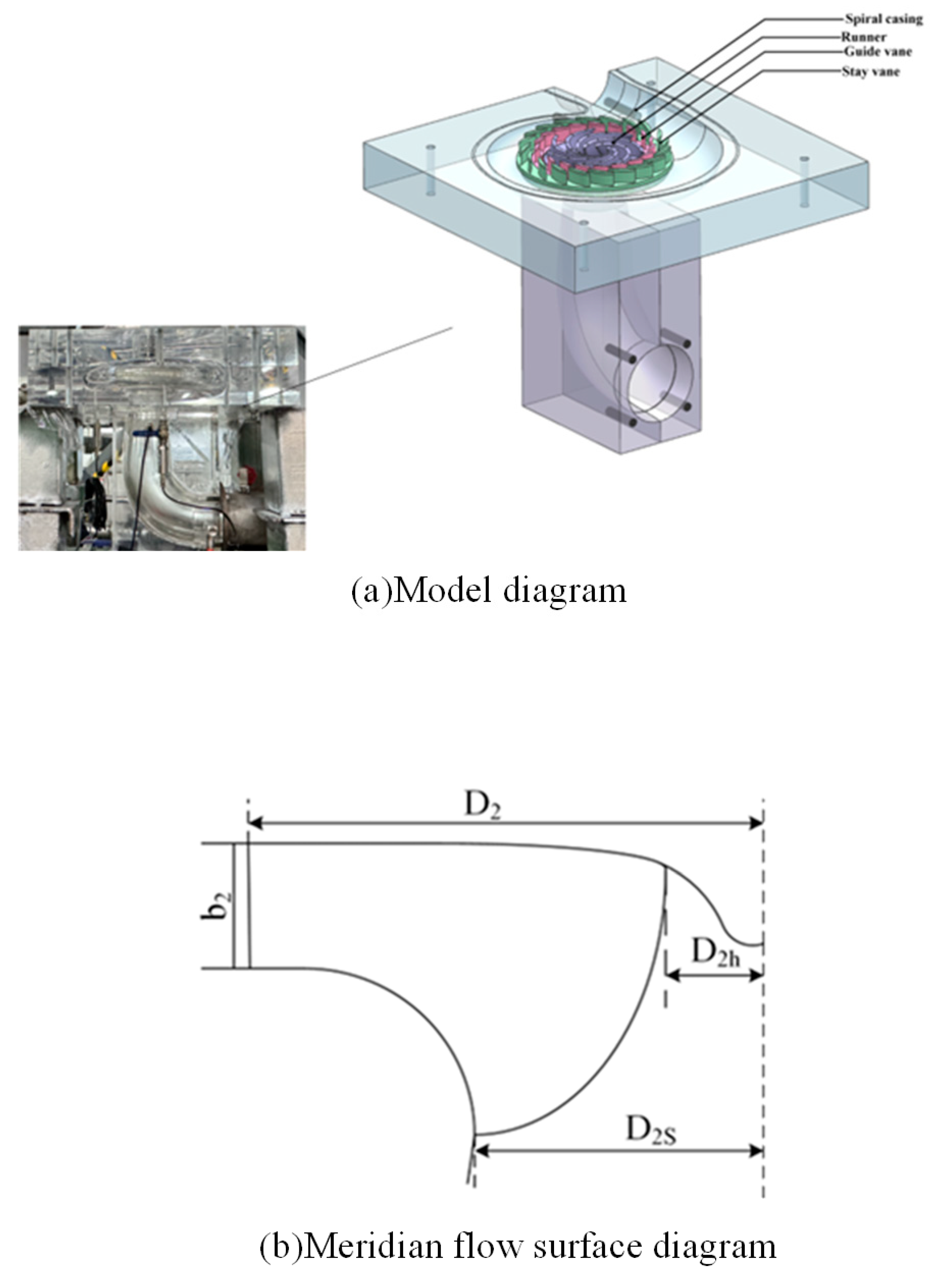

This study focuses on a model of a pump-turbine, as illustrated in

Figure 1. model pump turbine

structure diagram (a). The unit primarily consists of several flow components, including the volute, fixed guide vanes, movable guide vanes, runner, and draft tube. A schematic representation of the meridional flow surface is provided in

Figure 1. model pump turbine

structure diagram (b). Specific parameters of the unit, such as the runner speed, design flow rate, and design head, are detailed in

Table 1.

2.2. Experiment Method

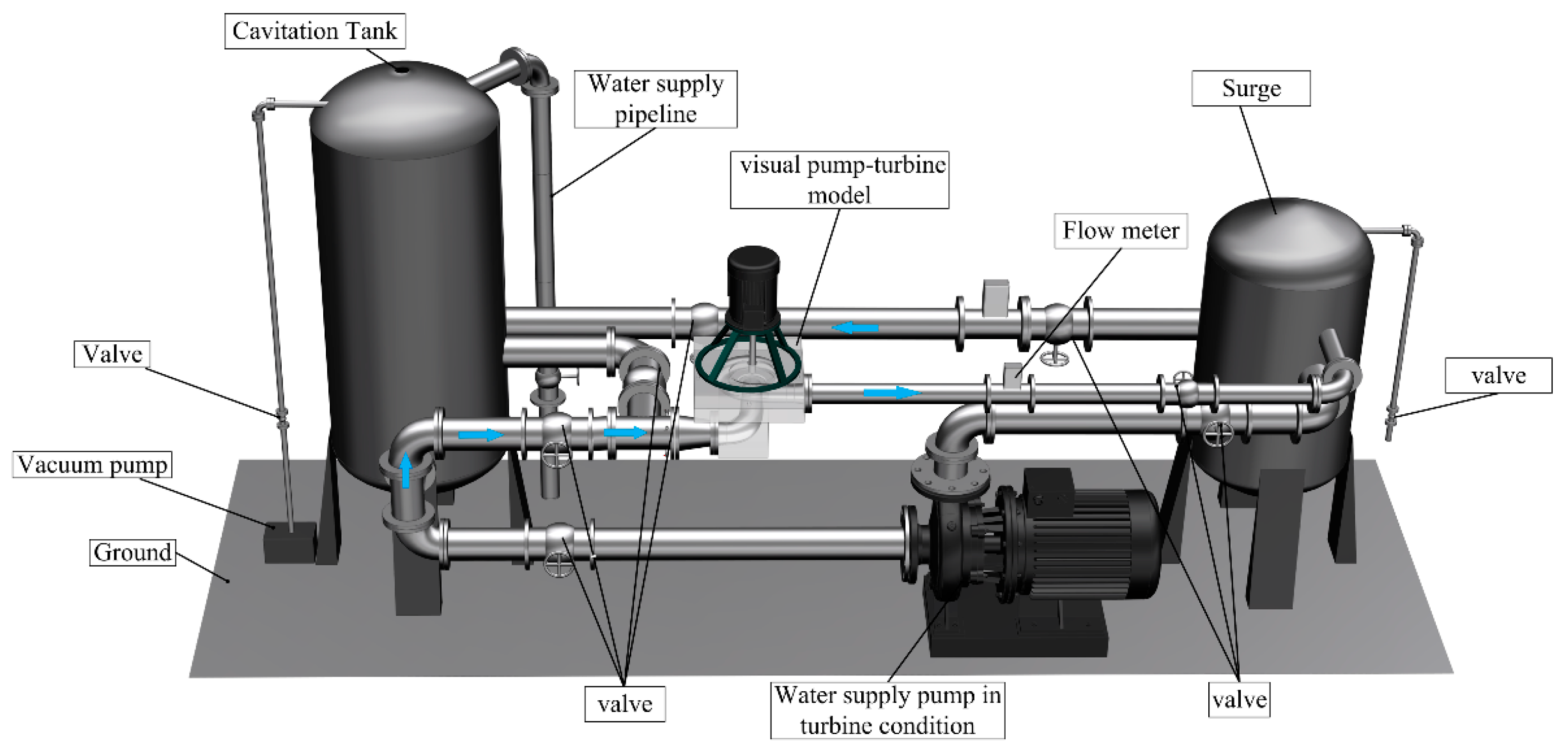

The experiment was conducted on a closed-loop water pump turbine test rig, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The experimental setup included force sensors, data acquisition instruments, and solenoid valves. Pressure gauges were installed at the inlet and outlet of the water pump turbine unit to measure pressure, allowing for the calculation of the pressure differential across the pump turbine. Additionally, a flow meter was utilized to determine the flow rate within the system.

The specific experimental procedure is as follows: (1) Close the valves on the inlet and outlet pipelines of the water supply pump while simultaneously opening the valves on the inlet and outlet pipelines under pump operation, as well as the return water valve. (2) Verify the opening and closing status of the relevant valves during the experiment and ensure the system is sealed. (3) Fill the left-side cavitation tank with water to a level that submerges the turbine runner, then activate the motor. Next, fill the right-side pressure tank with water. Once the right-side pressure tank is full, close its valve. (4) Release any air trapped in the system through the valve of the left-side cavitation tank and adjust the valve on the return water line to its maximum opening. (5) Collect data from the flow meter and pressure gauge. (6) Gradually reduce the valve opening. (7) After the flow meter data stabilizes, repeat steps (5) and (6) until all data has been collected.

3. Numerical Simulation Methods

3.1. Numerical Simulation Setup

Numerical simulation of the flow field was conducted using computational software.

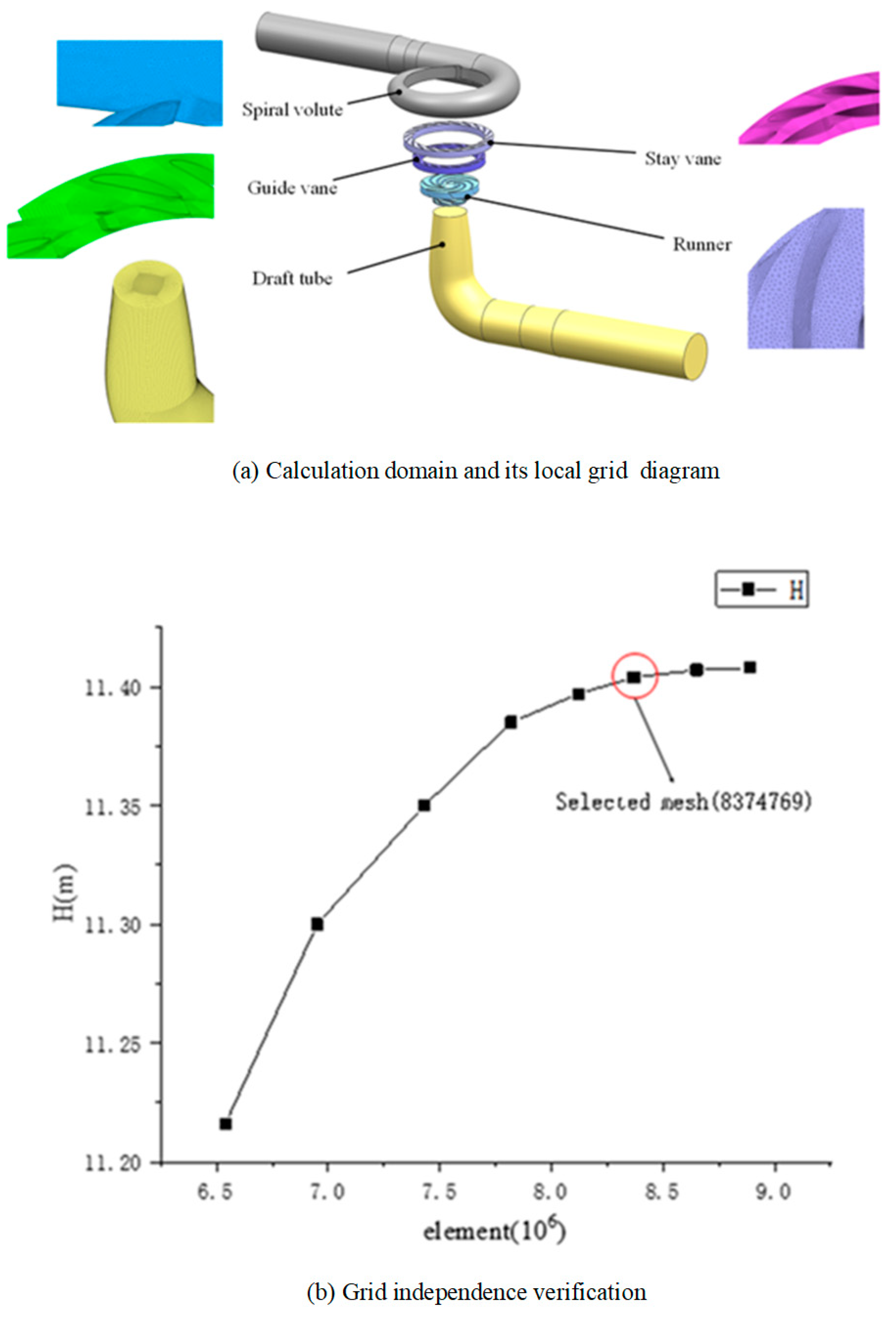

Figure 3 illustrates the computational domain and the grid schematic, which consists of five flow components: the volute, fixed guide vanes, movable guide vanes, runner, and tailwater pipe. The computational domain was pre-processed for grid generation using commercial software. Hexahedral mesh elements were employed for the fixed guide vanes, movable guide vanes, and tailwater pipe, while tetrahedral mesh elements were utilized for the volute and runner, as depicted in

Figure 4(a). To minimize computational resource expenditure while ensuring the accuracy of the results, the independence of the grid was verified by examining the head rise. As shown in

Figure 4(b), the increase in head rise of the pump-turbine diminishes progressively with an increase in the number of grid elements

Considering the costs associated with simulation and the required computational accuracy, this study selects a grid count of 8,374,769 for the calculations.

Table 2 presents the types and quantities of grid cells for each flow region.

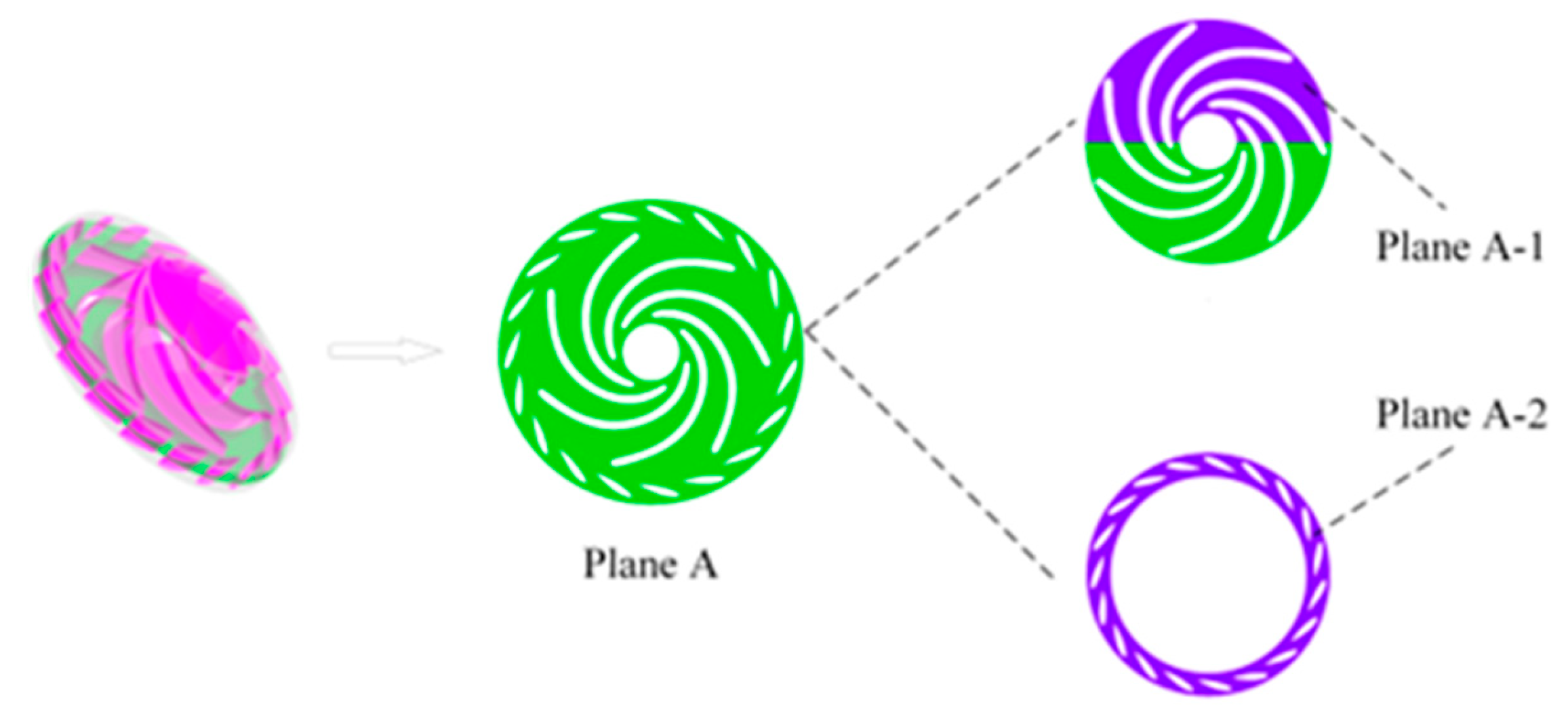

In the computational software, the rotor region is designated as a rotating area based on multiple reference frames (MRF), while the remaining regions are classified as stationary. The inlet of the tailwater pipe is configured as a total pressure inlet, the volute outlet is set as a flow outlet, and the wall surfaces are defined as non-slip boundaries. The governing equations consist of the continuity equation, the energy conservation equation, and the momentum conservation equation. The calculations employ the RNG k-ε turbulence model, the mixture multiphase flow model, and the Schnerr-Sauer cavitation model, which is based on the Rayleigh-Plesset bubble dynamics equation. The fluid medium is specified as water and water vapor, with the saturation vapor pressure of water set at Pv = 3540 Pa and the ambient pressure at 0 Pa. A convergence criterion of a residual less than 10^-5 is established. The mid-plane flow surface between the rotor and the movable guide vanes is captured as Plane A, as illustrated in

Figure 5. The time step is set to one step for every 3° of rotation, totaling 120 steps for one complete rotation, with a time increment of 0.0005 seconds. Starting from the last step of the transient calculation at the 10th rotation of the rotor, a sequence of 121 data sets, spaced by two time steps, is utilized for subsequent flow field analysis.

3.2. Snapshot POD Method

When the number of grid nodes and elements significantly exceeds the number of sampling instances, the classic POD method can become excessively resource-intensive and time-consuming. Consequently, this study employs the snapshot POD approach proposed by Sirovich [

26]. The underlying principle is as follows: a set of snapshots is formed by selecting flow field data from M grid elements at N instantaneous moments within a specified flow duration, and the time-averaged data for each grid element during this period is extracted.

By applying equation (3) to remove the time-averaged data corresponding to each grid cell from the original flow field at each instant, the resulting data reflects the fluctuations within the flow field.

The covariance matrix is derived from the matrix formed by the fluctuating data of the flow field, followed by the calculation of the eigenvalues and corresponding eigenvectors of the covariance matrix.

The corresponding spatial basis modes and temporal mode coefficients of the POD can be derived from equations (6) and (7).

The temporal average mode, in conjunction with a set of base modes, can reconstruct the flow field at any given moment using different order modes, as expressed in equation (8).

3.3. DMD Method

The principle of DMD decomposition, as proposed by Schmid [

20], is outlined as follows: The computational results are organized in chronological order, forming a set of snapshot matrices as represented in equation (9).

Let

represent the i-th snapshot, and N denote the total number of snapshots. It is assumed that there exists a linear mapping from the snapshot matrix

to the matrix

, expressed as follows:

Consequently, all subsequent snapshots can be represented using the matrix A and the vector x

1 as indicated in equation (11).

Matrix A can be defined as follows:

The matrix represents the pseudoinverse of the matrix , while the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of matrix A serve as the eigenvalues and modes in the context of DMD.

The singular value decomposition of matrix X yields matrices

,

, and

, as indicated in equation (13). By retaining the first r rows and r columns of these matrices, new matrices

,

, and

are obtained. Subsequently,

is computed using equation (14).

The eigenvalues and eigenvectors of matrix

are denoted as

and

, respectively, and the corresponding DMD modes can be derived using equation (15).

The logarithm of the eigenvalues, when considered in relation to the time step size, has its imaginary and real components corresponding to the magnitudes of the frequencies and the growth/decay rates of the various modes in DMD.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Cavitation Characteristics

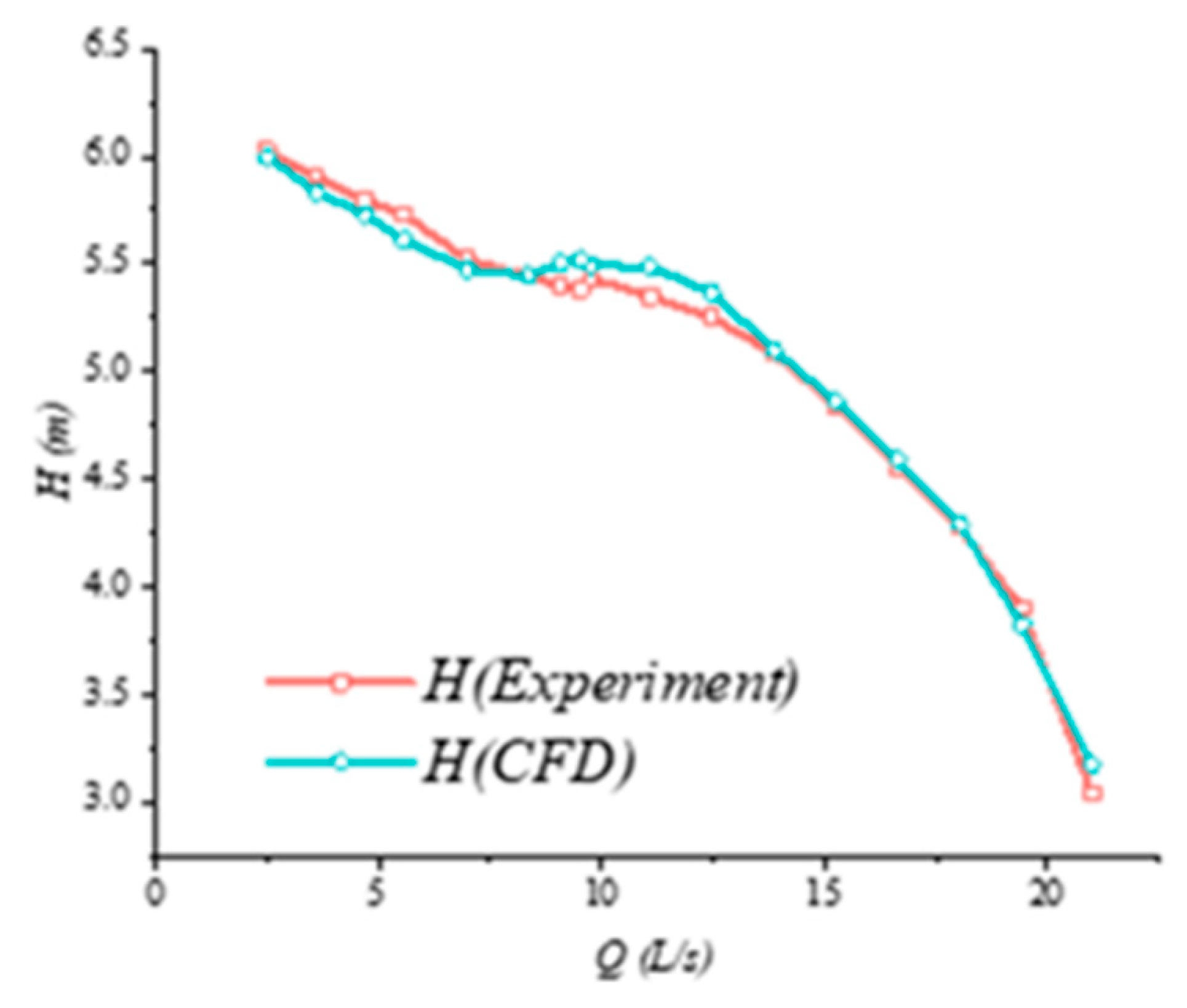

To validate the accuracy of the numerical simulation calculations, this study conducted experiments and numerical simulations under the conditions of 0 to 1.2 times Q

d. The resulting Q-H (flow-head) curve is illustrated in

Figure 5. The findings indicate that the relative error is within 5%, which falls within an acceptable range. Consequently, the numerical simulation results can be utilized for subsequent analyses.

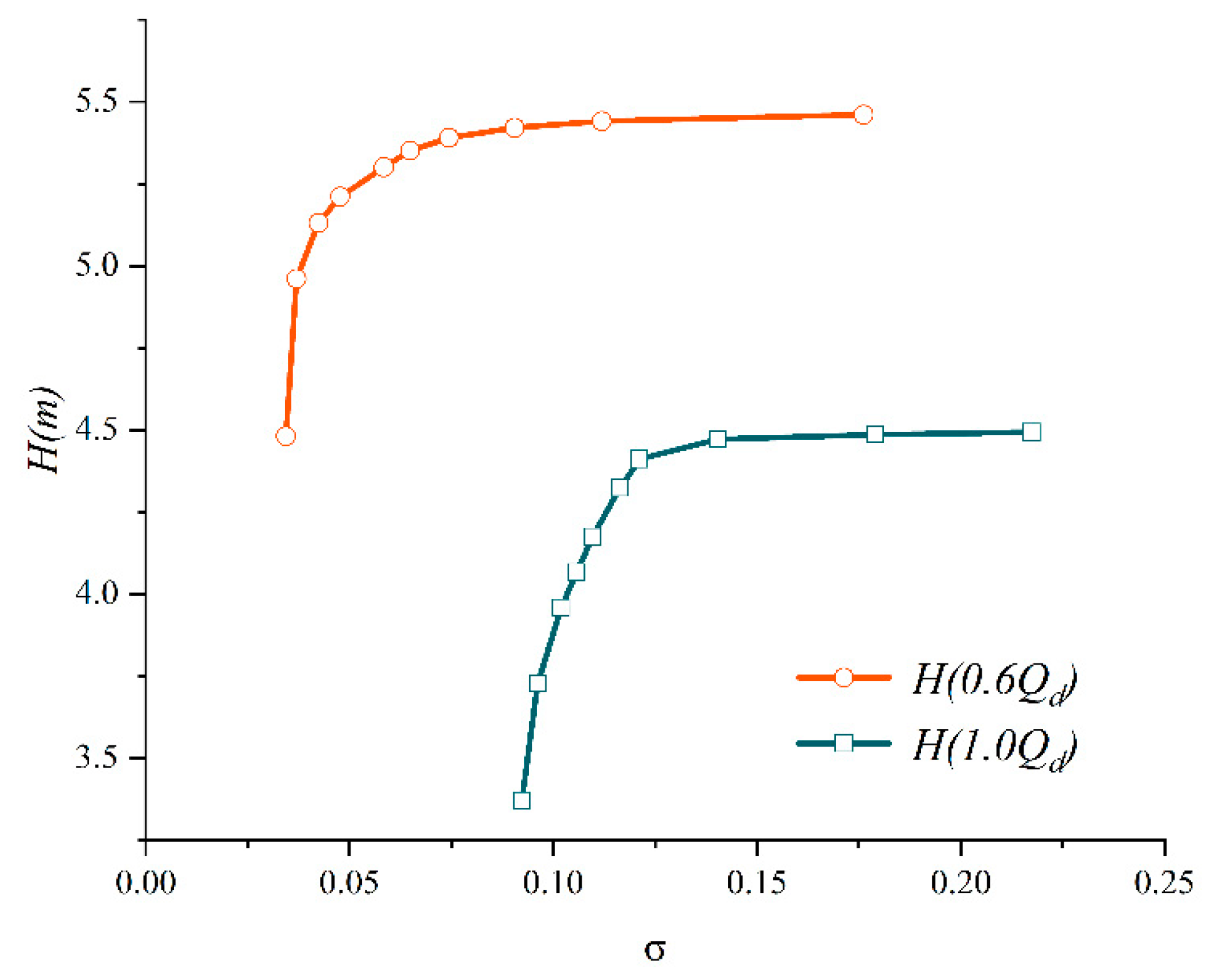

Numerical simulations of cavitation characteristics were conducted for the conditions of 0.6 times Q

d and Q

d. The resulting cavitation characteristic curves are illustrated in

Figure 6, where the horizontal axis represents the cavitation coefficient defined in equation (17), and the vertical axis indicates the head corresponding to the respective cavitation number.

It is evident that as the cavitation number decreases, there is little variation in the head during the initial phase until a critical point is reached (referred to as critical cavitation), at which point a noticeable decline in head begins. Subsequently, the slope of the curve increases rapidly, leading to a sharp decrease in head, significantly impacting the performance of the unit.

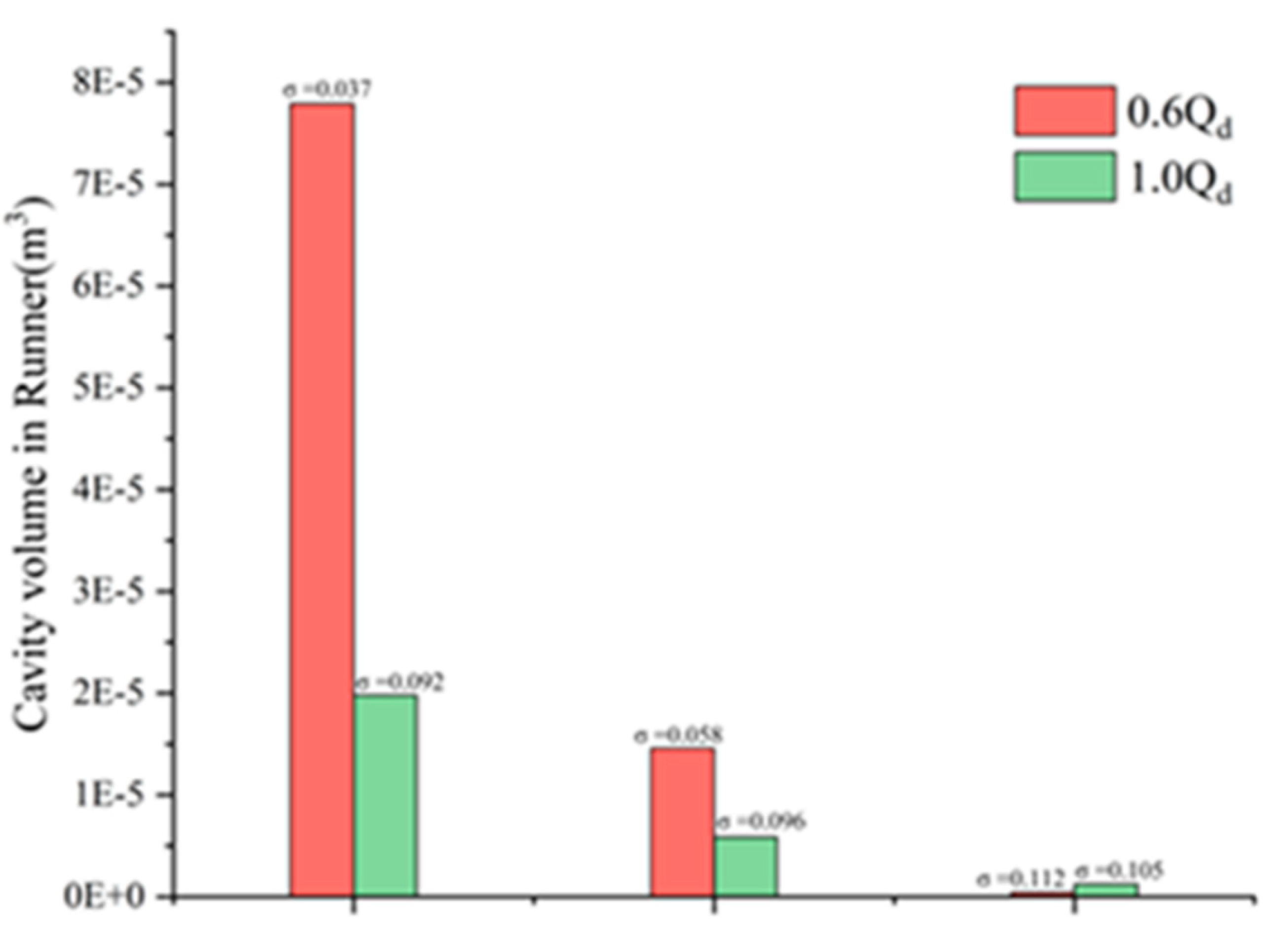

Figure 7 illustrates the total volume of cavitation bubbles in the impeller region under the conditions of 0.6 Q

d and Q

d at varying levels of cavitation.

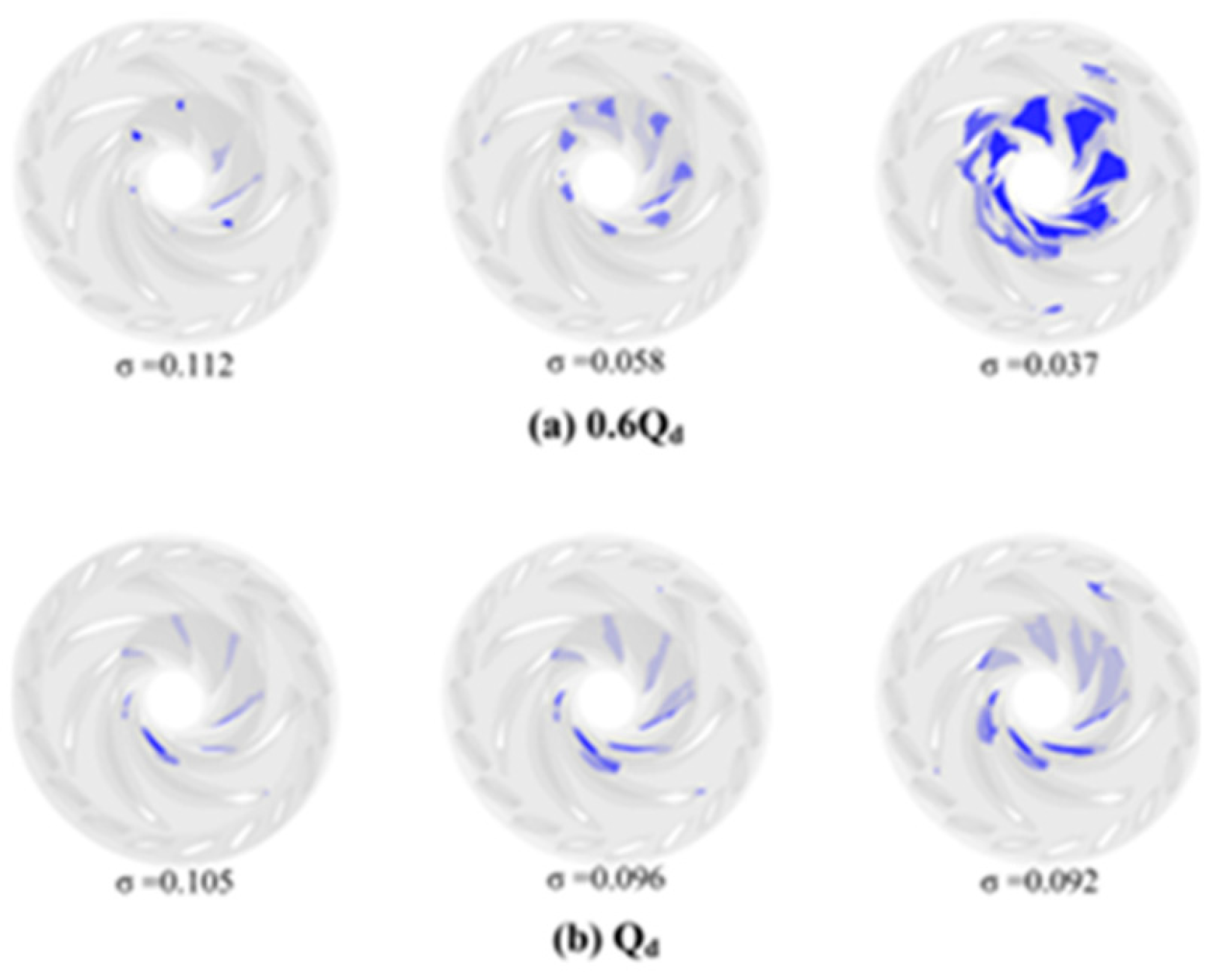

Figure 8 depicts the iso-surface formed by the cavitation volume fraction equal to 10% under the corresponding cavitation conditions. A comparison of these two figures reveals that when the cavitation number is relatively high and bubbles are just beginning to form, the volume of the bubbles is minimal, occupying a small portion of the flow channel and causing negligible disturbance to the flow field. As the cavitation number decreases to a critical point, cavitation develops to a certain extent, resulting in bubbles occupying part of the flow channel and affecting the flow field, which leads to a reduction in head. Conversely, when cavitation is fully developed, the bubbles occupy a significant portion of the space, severely impeding the normal flow of water.

In the Qd operating condition, cavitation occurs predominantly on the pressure side, whereas in the 0.6Qd condition, significant cavitation is observed on both the suction and pressure sides. Notably, the cavitation on the suction side is primarily concentrated near the upper cover plate, while the pressure side cavitation is mainly found close to the hub. Additionally, due to the dynamic interference between the rotating blades and the stationary guide vanes, cavitation begins to manifest at the outlet of the rotating blades and in the no-blade region. As cavitation progresses, the volume of the vapor bubbles in the no-blade area increases, adversely affecting the flow in that region. This phenomenon leads to a sharp decline in head and a reduction in efficiency.

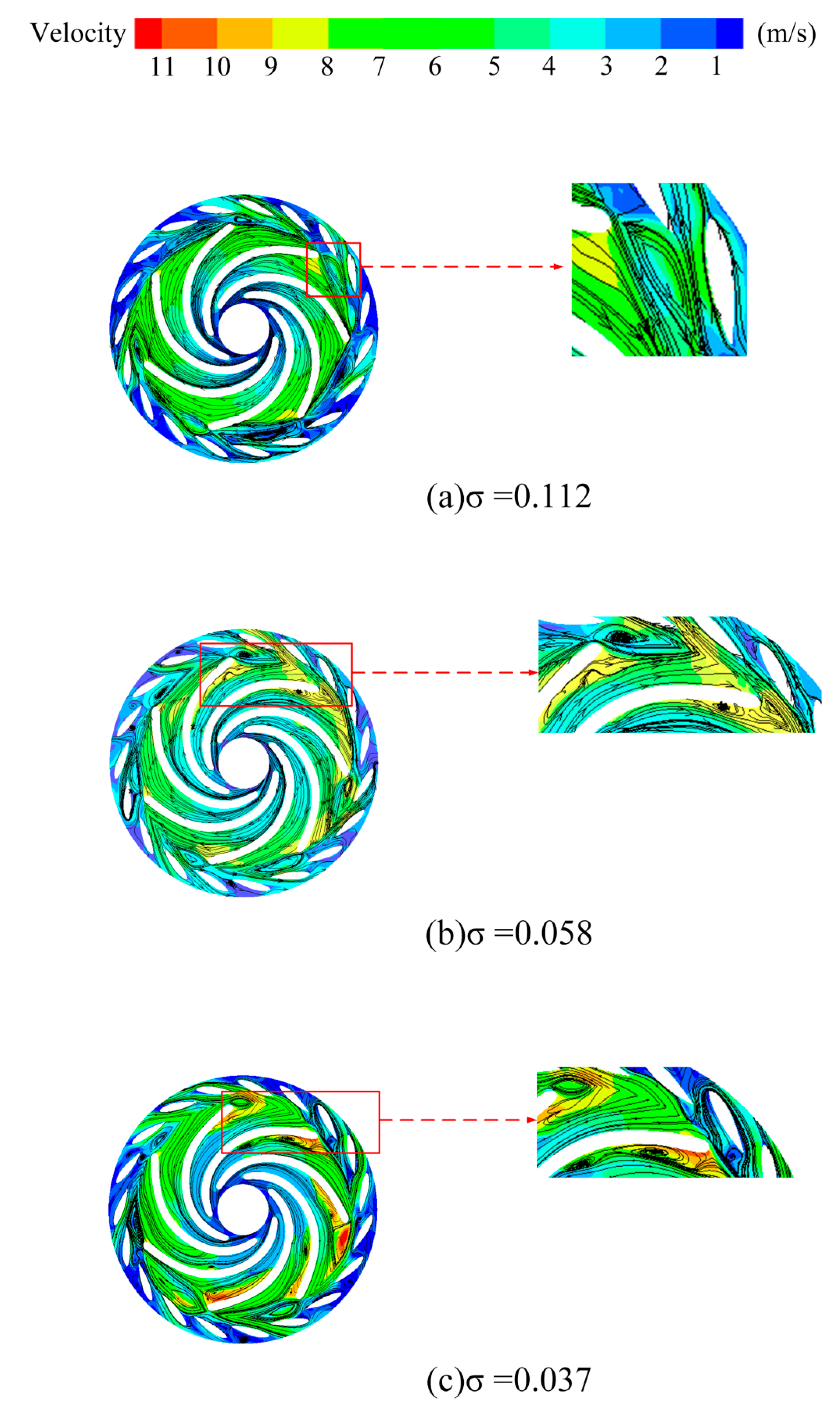

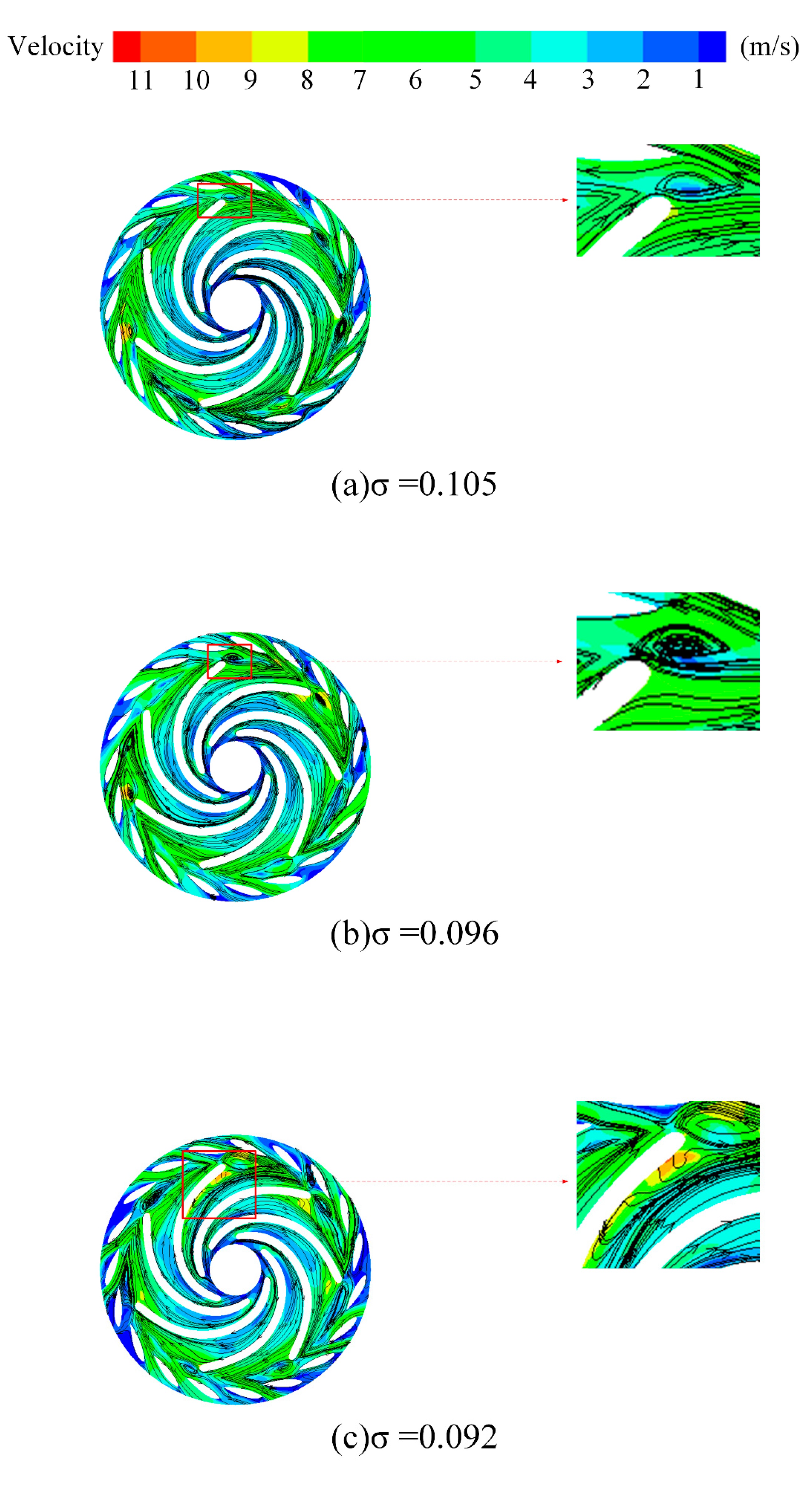

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 illustrate the velocity contours and streamlines on the Plane A for different cavitation levels at 0.6 Q

d and Q

d operating conditions. The flow separation on the suction side of the blade exit and the recirculation in the variable guide vane region result in the formation of large-scale vortex structures in the blade-free zone due to internal viscous forces. In comparison to the Q

d condition, the recirculation phenomenon in the guide vane area at 0.6 Q

d is more pronounced, leading to larger vortex structures. Furthermore, as the degree of cavitation intensifies, the size of the vortices in the blade-free zone increases, exacerbating the flow separation on the suction side of the blades. This results in water flowing back into the rotating wheel, creating recirculation vortices near the suction side of the blades, which disrupts the flow field structure in the rotating wheel region. The vortices present in both the blade-free and rotating wheel areas significantly impede the flow within the field, ultimately resulting in a decline in the performance of the unit.

4.2. Analysis of Energy Dissipation Characteristics in Cavitating Flow Fields

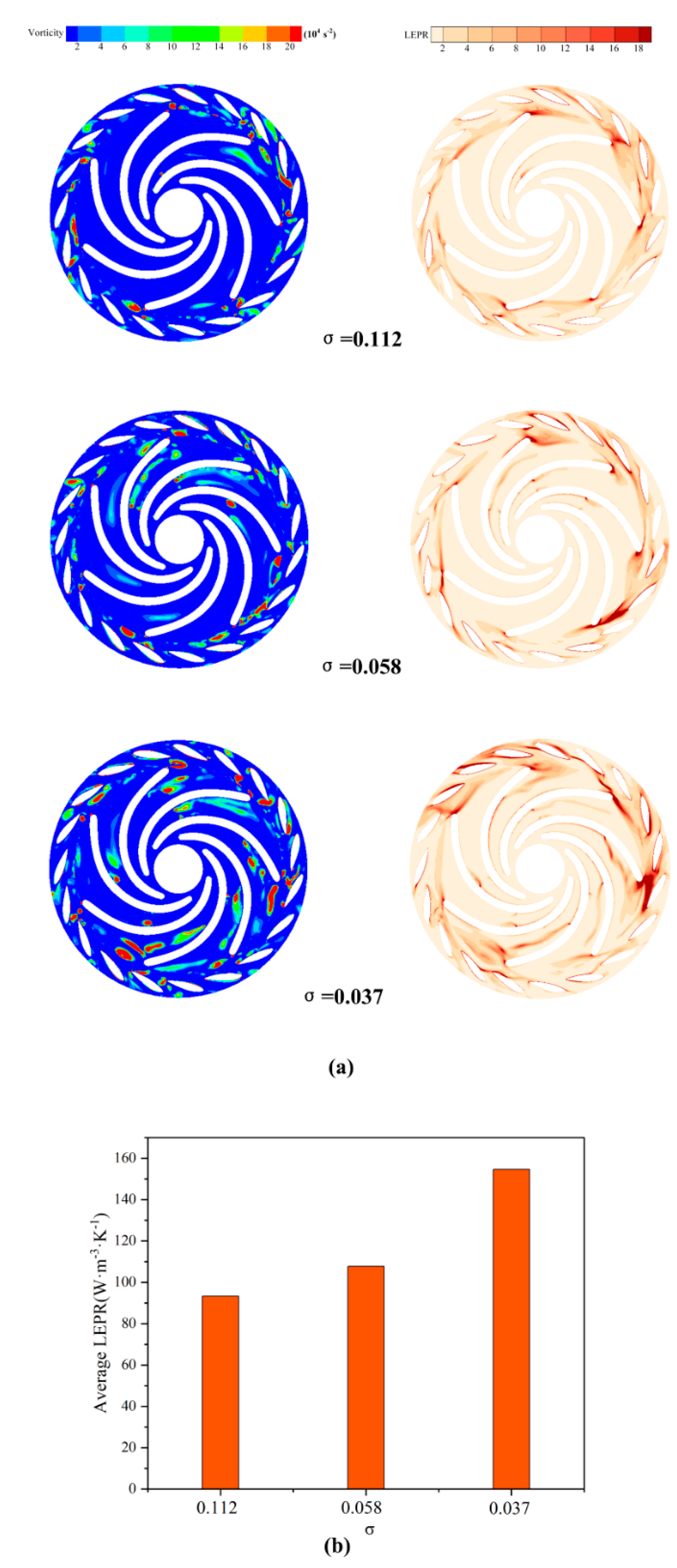

To facilitate a more intuitive observation of the vortices and the associated energy loss distribution in low flow conditions, the Q criterion vortex identification method was employed to capture the vortices in the flow field of Plane A.

Figure 11 illustrates the vorticity and its corresponding entropy generation distribution, along with the average entropy generation in Plane A's flow field. As indicated by the comparison of the average entropy generation in Plane A's flow field shown in

Figure 11 (b), it is evident that with the progression of cavitation, the entropy generation increases, leading to greater energy loss.

Figure 11 (a) presents the vortex map identified using the Q criterion, revealing that during the initial stages of cavitation, high vorticity primarily occurs in the blade exit region and the blade-free zone between the moving guide vanes. As cavitation intensifies, the scale of the high-intensity vortices in the blade-free zone increases, and the number of vortices in the impeller flow field also rises, resembling the vortex structure distribution depicted in

Figure 9 , thereby accurately identifying the vortex structures. Furthermore,

Figure 11 (a)also displays the entropy generation distribution, which, upon comparison, is predominantly concentrated in the vortex regions. Consequently, the cavitation vortices in the low-flow operating conditions of the pump-turbine are identified as the primary cause of energy loss.

4.3. POD Analysis of Vorticity Field

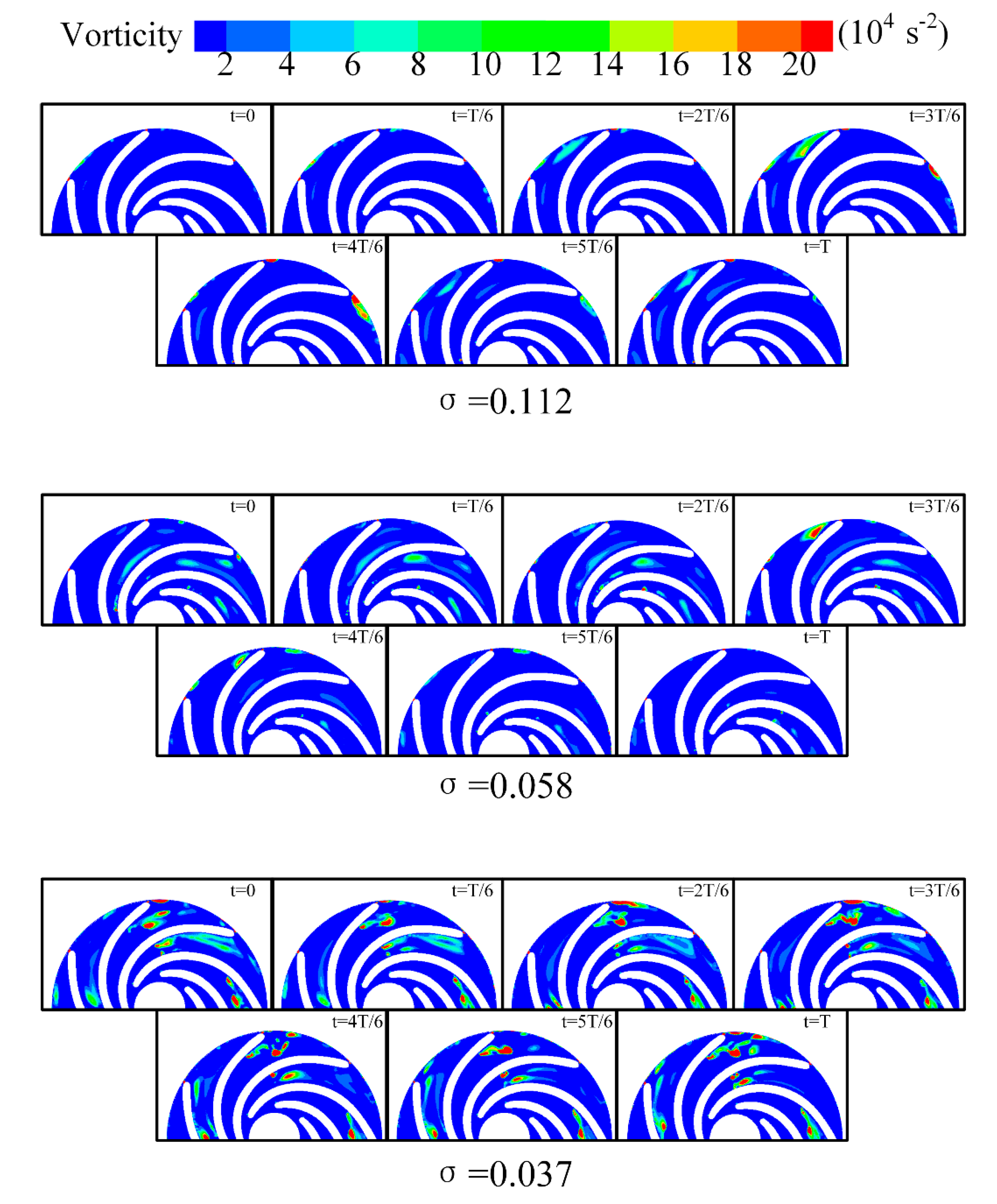

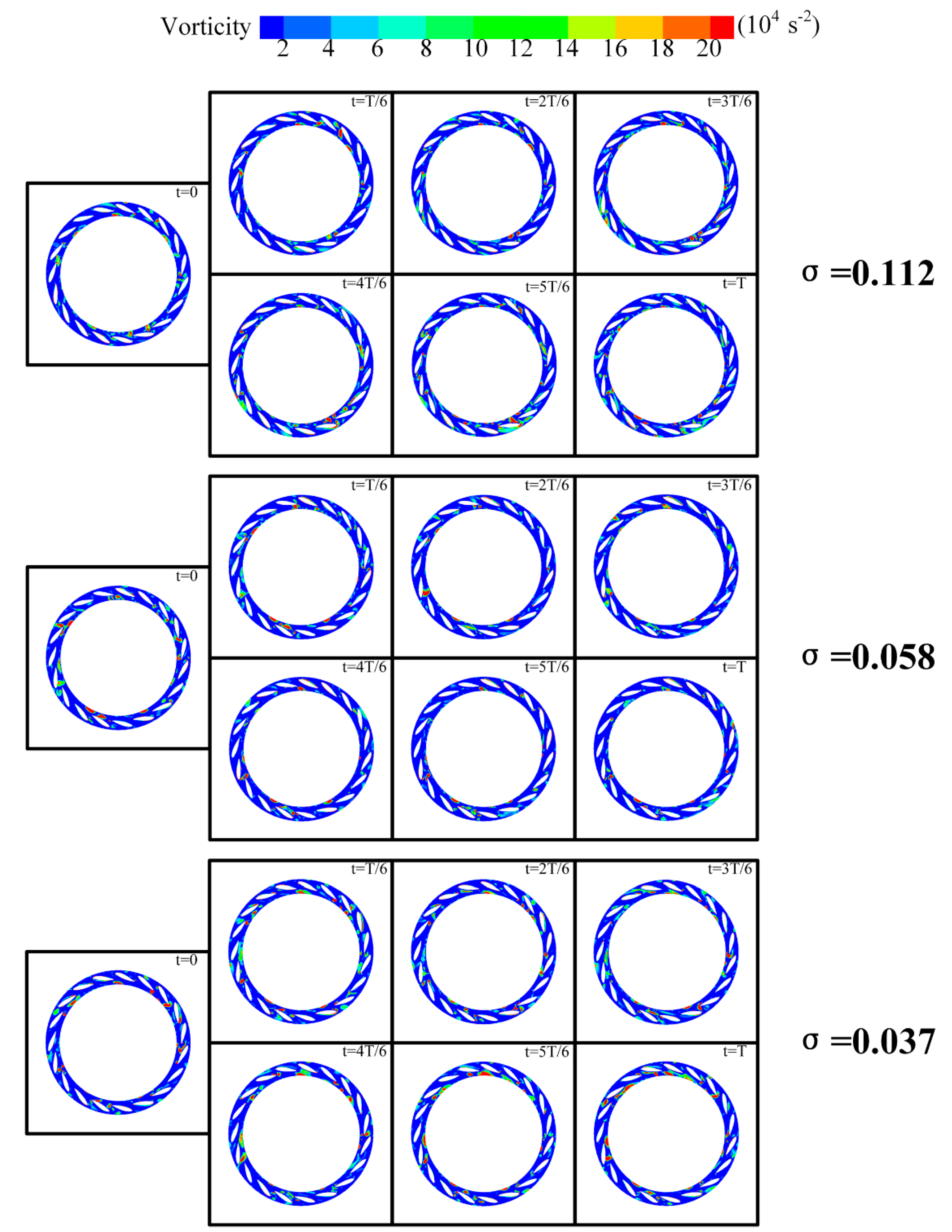

To investigate the evolution of vortices,

Figure 12 illustrates the vortex evolution of the flow field at Plane A-1 over one rotation period under various cavitation conditions. When σ is 0.112, the changes in the blade tip vortex during one cycle are minimal, indicating that this cavitation condition primarily governs the vortex distribution in the impeller region. At the impeller outlet, vortices resulting from the shedding of the blade tip are present, with an evolution period approximately equal to one rotation period T. As the cavitation coefficient decreases to σ = 0.058, Plane A-1 generates vortices with consistent evolution periods at the same location. However, due to the development of cavitation, the intensity of these vortices is significantly higher than during the initial stages of cavitation. Additionally, other flow passages exhibit vortices of varying sizes that lack a clear evolutionary pattern. With the further reduction of the cavitation coefficient to σ = 0.058, cavitation becomes fully developed, resulting in a substantial presence of vortices with unstable evolution periods throughout the entire rotation cycle at Plane A-1.

Figure 13 illustrates the evolution of vortices in the flow field of Plane A-2 over a single rotation period under various cavitation conditions. It is observed that large-scale vortices are predominantly located in the blade-free region and the trailing edge of the movable guide vanes. At the onset of cavitation, large-scale vortices are present in the blade-free area. As cavitation progresses, its influence on the flow field intensifies, leading to an expansion of vortex size in the blade-free region of Plane A-2, an increase in the number of vortex structures, and the emergence of small-scale, low-intensity vortices with varying periodicity.

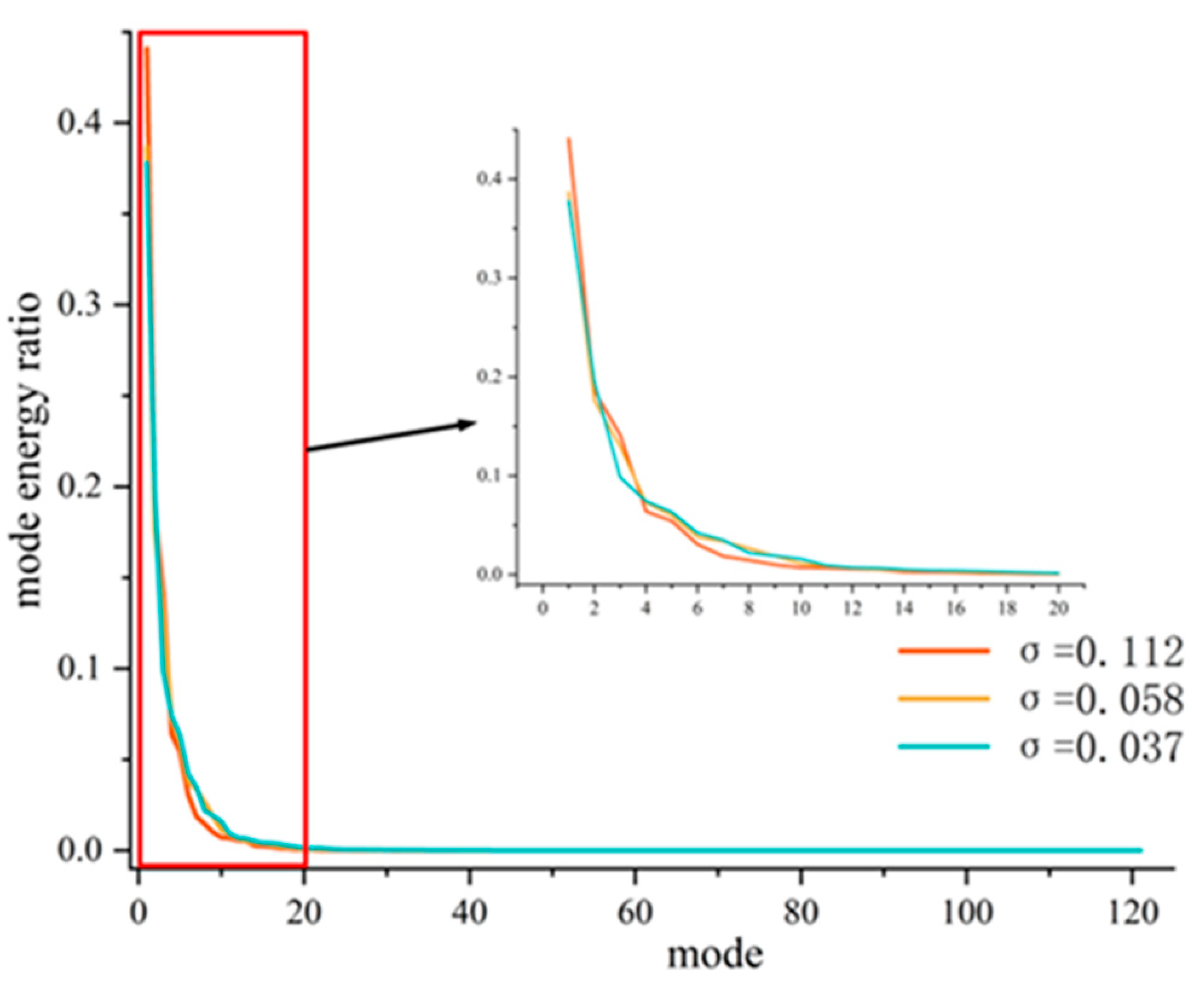

The instability of cavitation vortex structures leads to variability in the duration of vortex evolution cycles, making it challenging to observe the periodicity of these cycles. To address this, POD was employed to perform dimensionality reduction on snapshots of the vorticity field in a low flow condition over two rotation periods. This approach allowed for the extraction of the primary coherent vortex structures on Plane A based on the energy contributions of the various modal orders.

Figure 14 illustrates the proportion of energy contained in various order POD modes, represented as the ratio of the modal characteristic values to the sum of the eigenvalues. It is evident that the first-order mode possesses the highest energy proportion, significantly surpassing that of the second-order and higher modes, indicating that it represents the predominant coherent structures within the vorticity field. Furthermore, for modes of order greater than eight, the energy proportion falls below 1%, and this proportion decreases gradually with increasing mode order. This suggests that the corresponding modal vorticity fields are influenced by the unsteady characteristics of the flow, rendering their contributions negligible. Additionally, across different levels of cavitation, the distribution of energy proportions among the various modes remains largely consistent. Notably, the energy proportion of the first-order mode diminishes as the degree of cavitation intensifies, indicating that the progression of cavitation enhances the unsteady characteristics of the vorticity field.

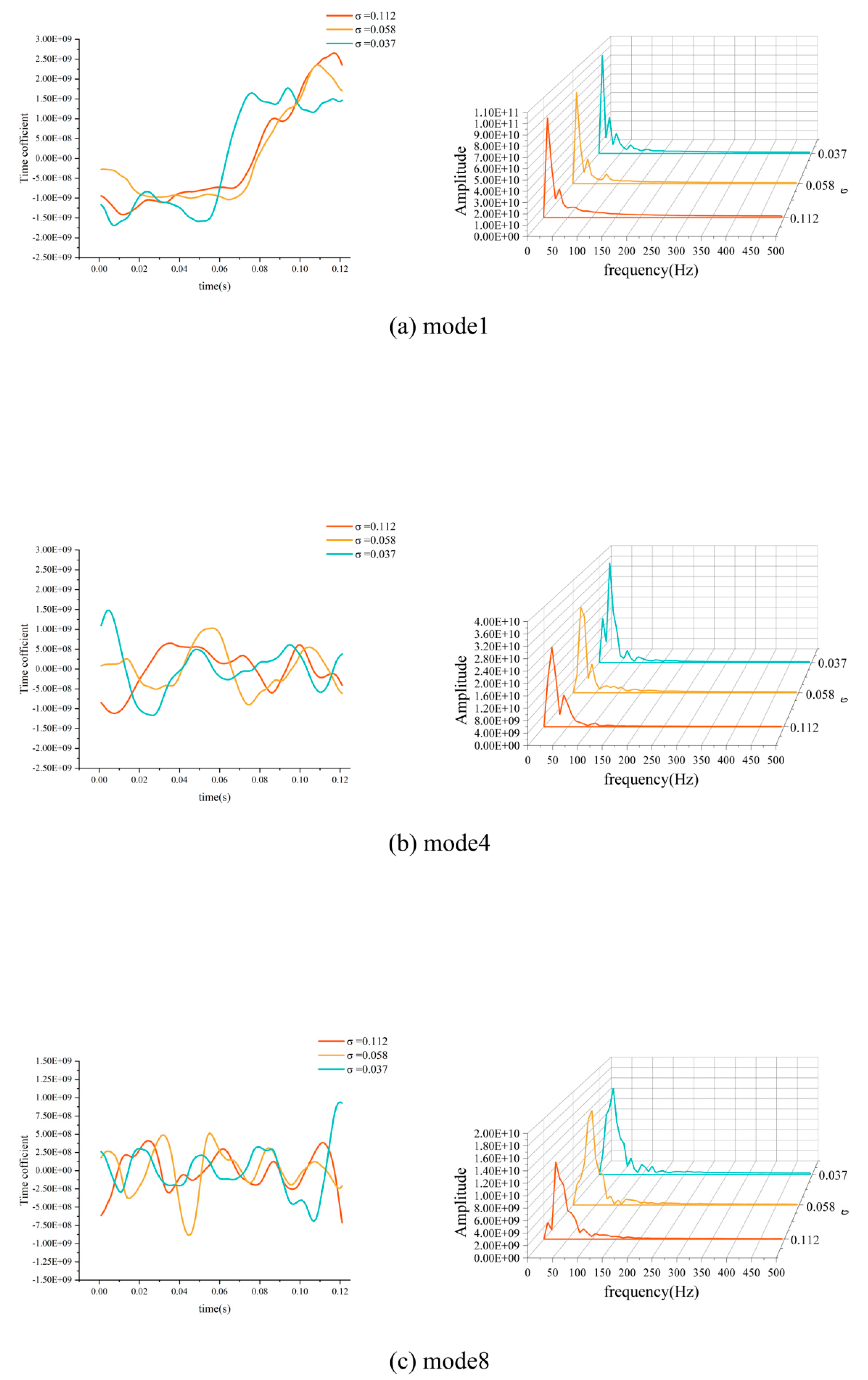

The time mode coefficients for the first, fourth, and eighth mode were subjected to a fast Fourier transform (FFT), resulting in the time evolution graphs and corresponding frequency spectra illustrated in Figure 15 (a), (b), and (c). In figure 15(a), the evolution of the first-order POD mode's time modal coefficients reveals a predominantly low frequency. This is attributed to a high energy proportion, indicating that the mode encompasses a significant amount of instability. As the instability of the cavitating flow field increases, the mode incorporates more unstable elements, leading to a chaotic evolution of the vortices. Conversely, as the mode order increases, the primary frequency of the time modal coefficients rises, while the energy proportion decreases, resulting in a reduction of the flow field information contained within the mode, thus rendering the frequency more distinct and clear.

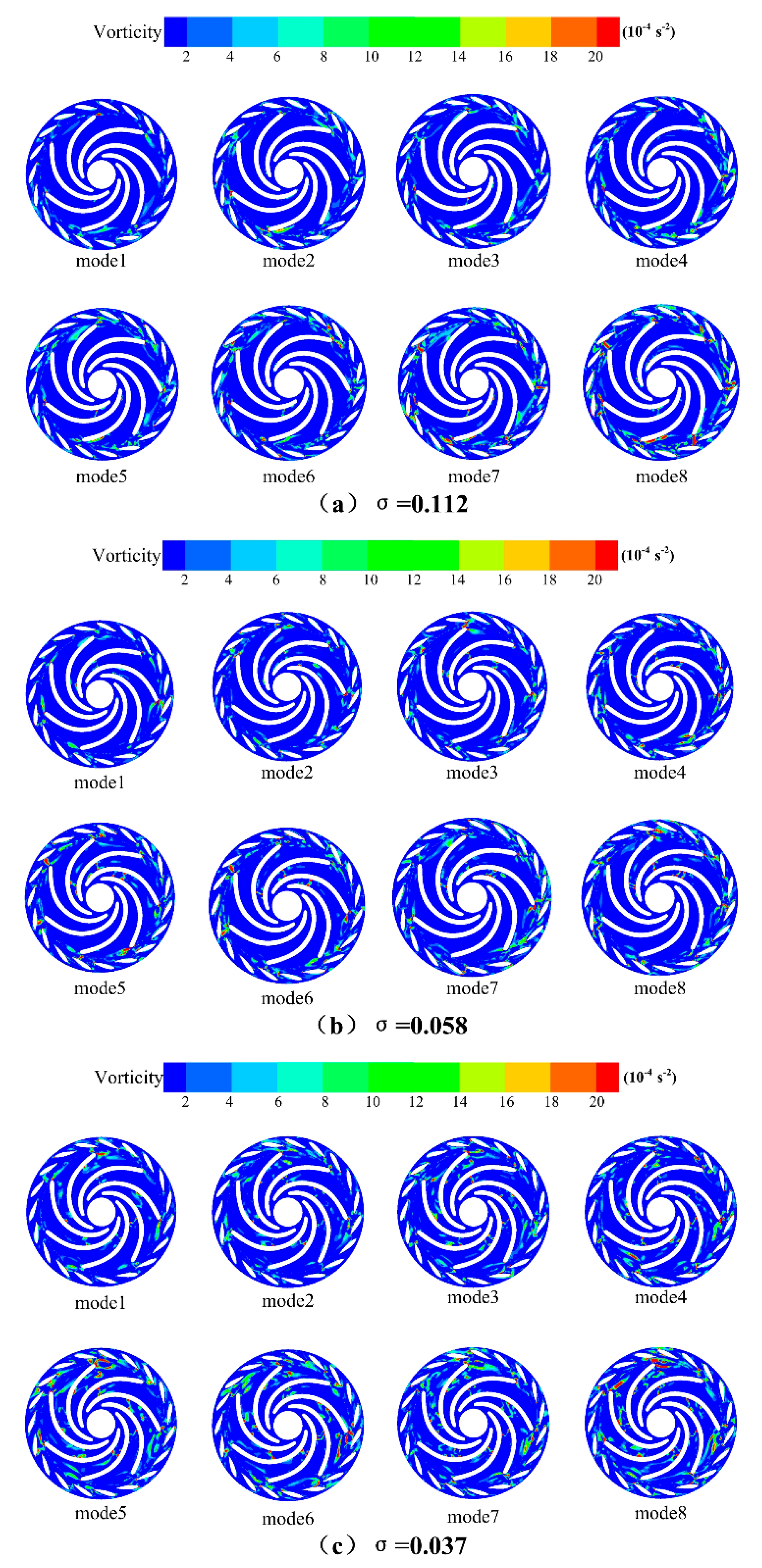

To provide a more intuitive and concrete observation of the coherent vortex structures at various cavitation levels,

Figure 16 illustrates the spatial distribution of the first eight modal shapes. When the cavitation number σ is set at 0.112, the mode 1 represents the coherent vortex attached to the outlet of the impeller blades. Modes 2-6 depict the diffusion of vorticity from the blade outlet into the non-bladed region. As the modal order increases to the mode 7 and mode 8, the wake vortices at the blade outlet expand, leading to dynamic interactions with the movable guide vanes. Concurrently, numerous small-scale vortices emerge in the surrounding non-bladed area, and vorticity is also generated on both the pressure and suction sides of the blades. Therefore, at a cavitation number of σ = 0.112, the wake vortices at the blade outlet are distributed across all modal orders, representing the inherent modes of the flow field. The wake vortices from the blades are identified as the primary source of energy dissipation, while the small-scale vortices in the non-bladed region predominantly appear in higher modal orders, a phenomenon attributed to the characteristics of the unsteady flow field. Although the contribution of small-scale vortices to the main flow structure is relatively minor, their high-frequency evolution significantly enhances the energy dissipation within the flow field.

As cavitation progresses, the scale of the vortices represented by the mode1 increases, leading to a greater number of vortices adhering to the blade surfaces within the rotor passage. When severe cavitation occurs, vortices that detach from the suction side of the blades are distributed across all modal orders, particularly near the rotor exit. Concurrently, smaller-scale vortices begin to transition towards lower-order modes, which possess a higher energy contribution, thereby enhancing their impact on the flow field. Consequently, with the advancement of cavitation, the vortices associated with the blade wake, as represented by the lower-order modes, increase in size and number, resulting in heightened energy losses. This phenomenon is accompanied by a reduction in the energy contribution of mode1, while the contributions from the mode2 and higher modes to the flow field become more significant, intensifying the unsteady characteristics of the flow and accelerating energy dissipation.

4.4. DMD Analysis of Vorticity Field

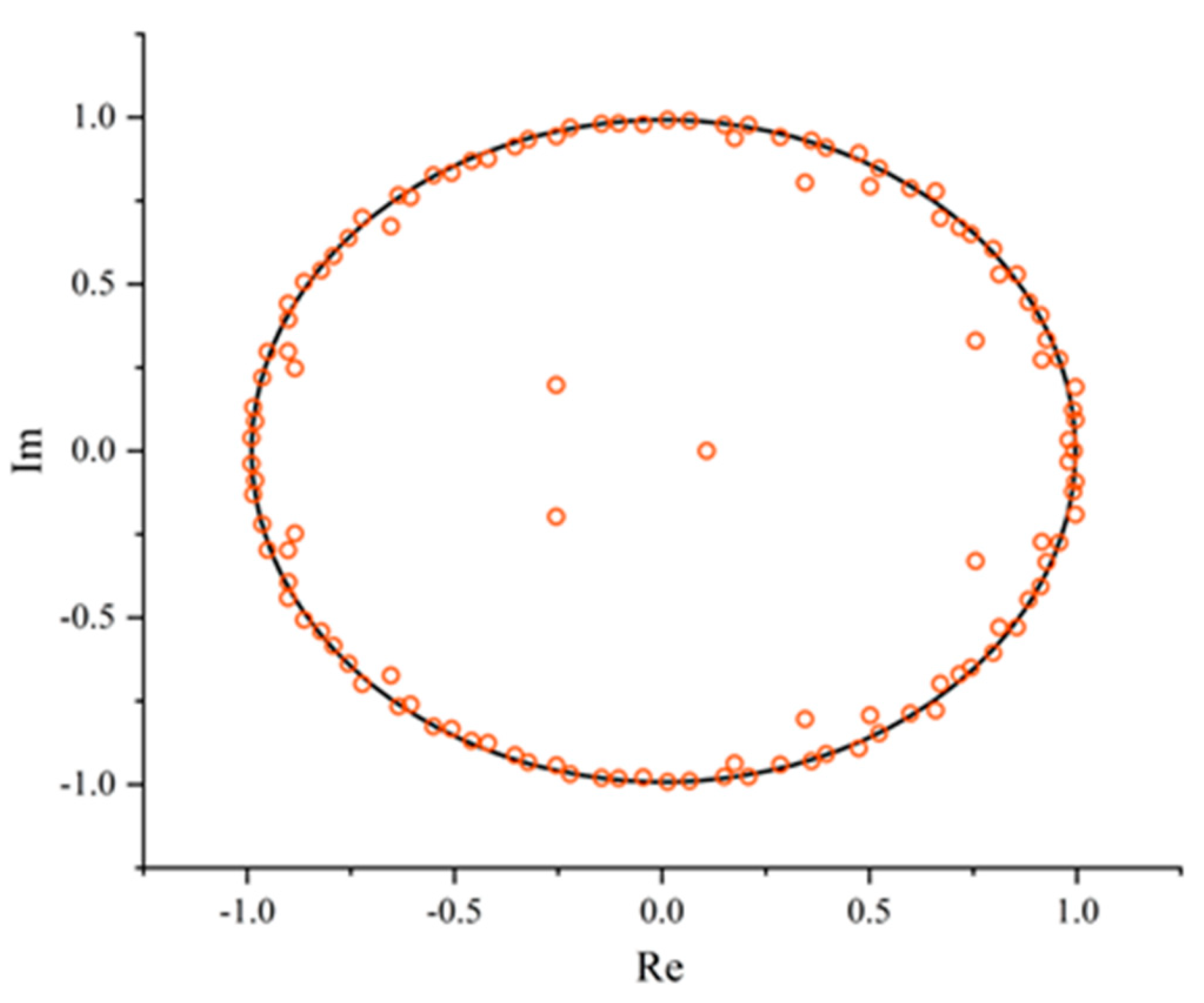

The POD method primarily identifies dominant coherent structures within a flow field by arranging modes based on their energetic contributions. The modes exhibit complex frequency components, and the DMD technique is employed for dimensionality reduction and decomposition of the flow field, allowing for the extraction of coherent structures at specific characteristic frequencies. This facilitates a comparative analysis of the dynamic characteristics of evolving vortex structures across different scales.

Figure 17 illustrates the distribution of the DMD modal eigenvalues in the complex plane, where the horizontal axis represents the real part of the eigenvalues and the vertical axis represents the imaginary part. A majority of the eigenvalues cluster near the unit circle, indicating that the corresponding modes are relatively stable and represent the primary coherent structures of the vorticity field. Conversely, modes located within the unit circle are deemed unstable and do not correspond to the main vortex structures of the vorticity field. The parameters that describe the flow field information of each mode are the real parts of the spatial basis modes, with each set of conjugate eigenvalues corresponding to conjugate modes.

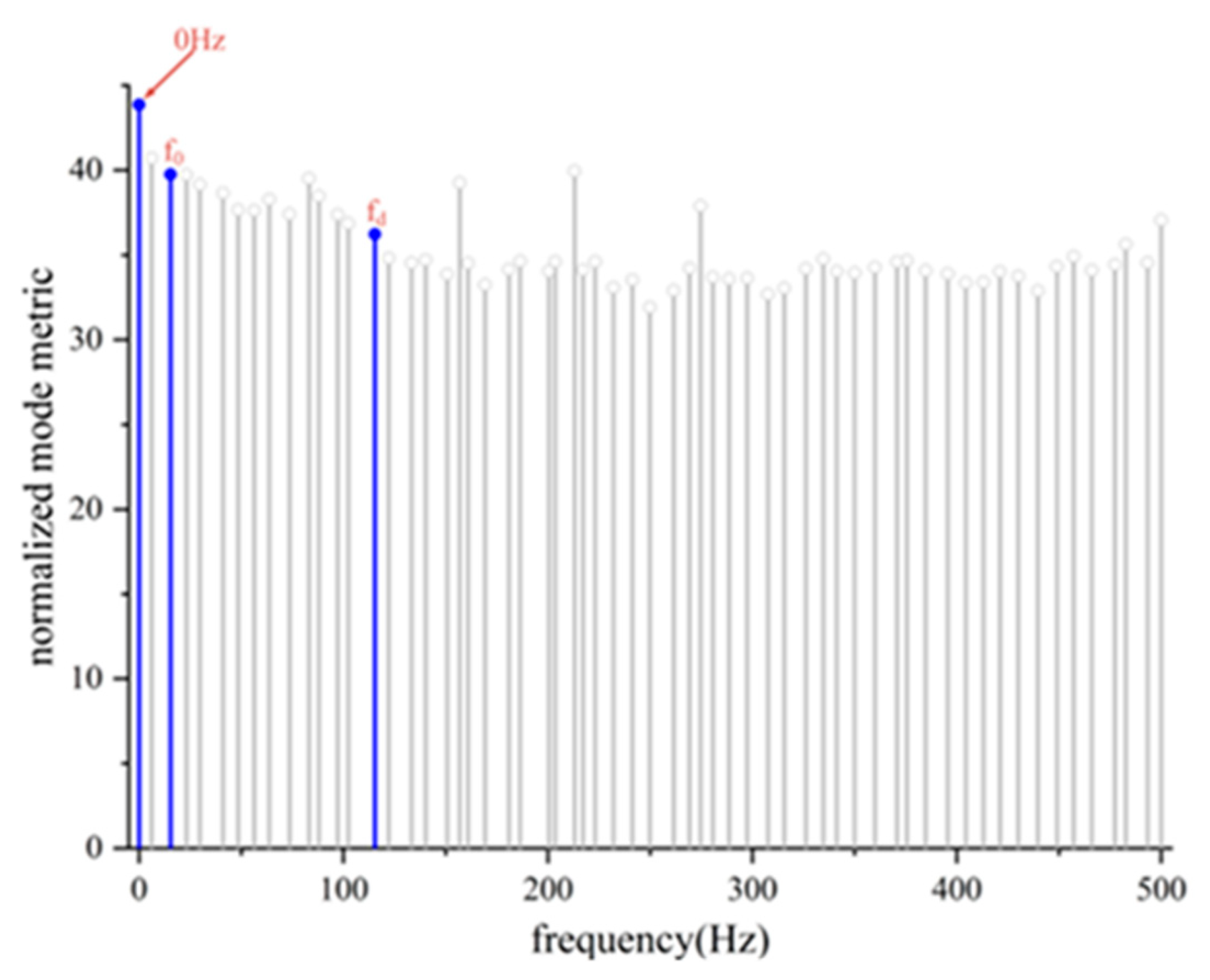

The mode frequencies and their corresponding correlation coefficients are illustrated in

Figure 18. The analysis was conducted by extracting modal characteristics at three specific frequencies: 0 Hz, the shaft passing frequency at f

0=16.66Hz, and the blade passing frequency at f

d=116.66Hz, based on varying wheel speeds and the number of blades.

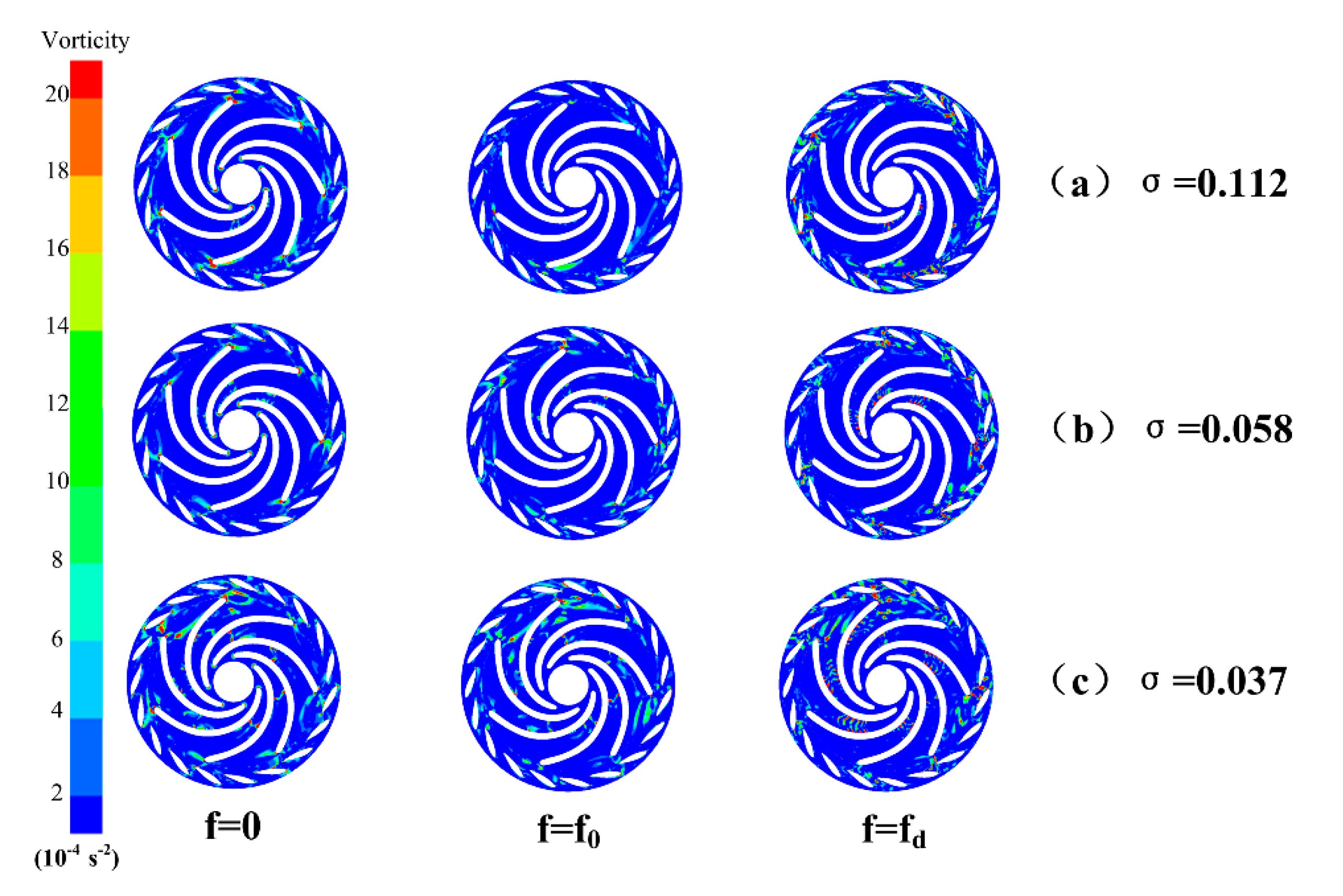

The spatial distribution and comparison of three DMD modes under various cavitation conditions are illustrated in Figure 19. The spatial distribution of the 0 Hz frequency mode represents the dominant time-averaged flow field within the flow, highlighting the primary regions of vortex distribution. The coherent vortex locations in the f0 and fd frequency modes correspond to those observed in the 0 Hz frequency mode. The f0 frequency mode predominantly showcases large-scale coherent vortices evolving at the rotational frequency of the main axis. In contrast, the fd frequency mode depicts coherent vortices evolving at the blade passage frequency, characterized by smaller scales compared to the previous two modes. Consequently, the vortices in the cavitating flow field evolve primarily at the main axis rotational frequency, while the instability induced by cavitation also gives rise to coherent vortices evolving at higher frequencies, such as the blade passage frequency fd. As the degree of cavitation intensifies, there is an increase in the number of small-scale vortical structures.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the impact of cavitation development on the structure of the flow field through experimental and numerical methods. It explores the primary regions of energy loss distribution and employs modal decomposition techniques to establish the relationship between cavitation development and vortex evolution, leading to the following conclusions:

1.The performance curves obtained from experiments and numerical simulations align closely, with the errors remaining within acceptable limits, thereby confirming the accuracy of the numerical simulations presented in this study. Additionally, the simulation methods were employed to investigate the cavitation characteristics under the design flow condition (Qd) and the low flow condition (0.6Qd). It was observed that cavitation phenomena are more pronounced under the Qd condition, with larger vortex structures compared to the lower flow scenario.

2.The findings related to the Q criterion and entropy production indicate that the Q criterion effectively captures vortex structures. As cavitation progresses, the scale of high-intensity vortices in the non-blade region increases, and there is a rise in the number of vortices in the rotor area. Additionally, regions of high entropy production are predominantly located within the corresponding high-intensity vortex areas. Consequently, the vortices present in the cavitating flow field are identified as the primary cause of energy loss in the system.

3.The cumulative energy contribution of the first eight POD modes exceeds 99%, encapsulating the predominant coherent structures within the flow field. The first POD mode exhibits a lower dominant frequency in its temporal modal coefficients, with the highest amplitude, representing vortices of varying evolutionary frequencies. As the mode order increases, the frequency of the temporal modal coefficients rises, resulting in a reduction of the frequency information contained, leading to clearer evolutionary frequencies and diminished amplitudes. Concurrently, as cavitation progresses, the instability of the flow field intensifies, causing a disruption in the vortex evolution cycle, which complicates the frequency content of the temporal modal coefficients. In the absence of significant cavitation, the wake vortices at the blade exit are distributed across all modal orders, representing the inherent modes of the flow field and contributing the most to energy dissipation. Conversely, small-scale vortices in the non-blade region predominantly appear in higher-order modes, a consequence of the unsteady characteristics of the flow field. As cavitation develops, the unsteady vortices from higher-order modes begin to diffuse into lower-order modes, leading to a decrease in the energy contribution of these lower modes, while the influence of unstable vortices on the flow field increases, thereby resulting in heightened energy dissipation.

4.The DMD method is employed to decompose the flow field from a frequency perspective, allowing for the extraction of coherent vortices. Cavitation vortices evolve at the rotational frequency of the main shaft f0, while the instability characteristics of the flow field induced by cavitation are accompanied by coherent vortices that evolve at higher frequencies, such as the blade passage frequency fd. Furthermore, as the degree of cavitation intensifies, there is an increase in the number of small-scale vortex structures.

Author Contributions

analyzed the data and wrote the paper, J.L.(Jiaxing Lu), and J.L.(Jiarui Li); C.Z., Y.Z., Y.H., and Y.P., designed the experiment and simulated; review and editing, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Sichuan Province natural science Foundation project and Joint Fund of National Natural Science Foundation. (No. 2024NSFSC0214 and No. U23A20669).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the main text of the article.

References

- Ambec, S.; Crampes, C. Electricity Provision with Intermittent Sources of Energy. Resource and Energy Economics 2012, 34, 319–336.

- Guezgouz, M.; Jurasz, J.; Bekkouche, B.; Ma, T.; Javed, M.S.; Kies, A. Optimal Hybrid Pumped Hydro-Battery Storage Scheme for off-Grid Renewable Energy Systems. Energy Conversion and Management 2019, 199, 112046.

- Pommeret, A.; Schubert, K. Optimal Energy Transition with Variable and Intermittent Renewable Electricity Generation. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 2022, 134, 104273.

- Rehman, S.; Al-Hadhrami, L.M.; Alam, Md.M. Pumped Hydro Energy Storage System: A Technological Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 44, 586–598.

- Widén, J.; Carpman, N.; Castellucci, V.; Lingfors, D.; Olauson, J.; Remouit, F.; Bergkvist, M.; Grabbe, M.; Waters, R. Variability Assessment and Forecasting of Renewables: A Review for Solar, Wind, Wave and Tidal Resources. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 44, 356–375.

- Xu, L.; Kan, K.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, D.; Binama, M.; Xu, Z.; Yan, X.; Guo, M.; Chen, H. Rotating Stall Mechanism of Pump-Turbine in Hump Region: An Insight into Vortex Evolution. Energy 2024, 292, 130579.

- Liu, Y.; Gong, J.; An, K.; Wang, L. Cavitation Characteristics and Hydrodynamic Radial Forces of a Reversible Pump–Turbine at Pump Mode. J. Energy Eng.2020,146,04020066.

- Tao, R.; Xiao, R.; Wang, F.; Liu, W. Cavitation Behavior Study in the Pump Mode of a Reversible Pump-Turbine. Renewable Energy 2018, 125, 655–667.

- Zhang, L.; Jing, X.; Wang, Z.; Chang, J.; Peng, G. Analysis of Francis Pump-Turbine Runner Cavitation Flows in Pump Mode. In Proceedings of the Volume 2: Fora; ASMEDC: Vail, Colorado, USA, January 1 2009; pp. 131–134.

- Li, G.; Hou, W.; Wang, H.; Qin, H.; Zhu G. Study on Cavitation Performance of High Water-Head Pump Turbine Based on CFD. Power System and Clean Energy2017, 33, 131-136.

- Hao, Y.; Tan, L. Symmetrical and Unsymmetrical Tip Clearances on Cavitation Performance and Radial Force of a Mixed Flow Pump as Turbine at Pump Mode. Renewable Energy 2018, 127, 368–376.

- Meng, Q.; Shen, X.; Zhao, X.; Yang, G.; Zhang, D. Numerical Investigation on Cavitation Vortex Dynamics of a Centrifugal Pump Based on Vorticity Transport Method. JMSE 2023, 11, 1424.

- Wu, J.; Qiu, N.; Zhu, H.; Xu, P.; Si, Q. Numerical Analysis of Vortex Structure in Centrifugal Pump Based on Unsteady Cavitation Flow. Journal of Xihua University2023, 42, 90 − 99.

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.; Li, J.; Xian, H.; Du, X. Analysis of the Vortices in the Inner Flow of Reversible Pump Turbine with the New Omega Vortex Identification Method. J Hydrodyn 2018, 30, 463–469.

- Ruan, H.; Guo, P.; Yu, L.; Zhou,C.; CHAO, W.;Li, X.Cavitation induced flow instability mechanism of pumptubine under pump conditions. Journal of Drainage and Irrigation Machinery Engineering.2021, 41, 779-786.

- Gong, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Li, D.; Zhang, H.; Wei, X. Application of Entropy Production Theory to Hydro-Turbine Hydraulic Analysis. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2013, 56, 1636–1643.

- Li, D.; Gong, R.; Wang, H.; Xiang, G.; Wei, X.; Qin, D. Entropy Production Analysis for Hump Characteristics of a Pump Turbine Model. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2016, 29, 803–812.

- Yu, A.; Wang, Y.; Lv, S.; Tang, Q. Numerical Analysis of the Cavity Vorticity Transport and Entropy Production in a Micropump. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer .2024, 159, 108144.

- Lumley, J. The structure of inhomogeneous turbulent flows. Atmospheric turbulence and radio wave propagation.1967, 166-178.

- Schmid, P.; Sesterhenn, J. Dynamic Mode Decomposition of Numerical and Experimental Data. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2008, 656.

- Lu, J.; Wu, F.; Liu, X.; Zhu, B.; Yuan, S.; Wang, J. Investigation of the Mechanism of Unsteady Flow Induced by Cavitation at the Tongue of a Centrifugal Pump Based on the Proper Orthogonal Decomposition Method. Physics of Fluids 2022, 34.

- Yang, G.; Zhang, D.; Shen, X.; Pan, Q.; Pang, Q.; Lu, Q. Investigation on Flow Instability in the Hump Region of the Large Vertical Centrifugal Pump under Cavitation Conditions Based on Proper Orthogonal Decomposition. Physics of Fluids 2024, 36.

- Yang, J.; Feng, X.; Liao, Z.; Pan, K.; Liu, X. Analysis on the Mechanism of Rotating Stall Inner a Pump Turbine in Pump Mode Based on the Proper Orthogonal Decomposition. Journal of Fluids Engineering 2023, 145, 091202.

- Xie, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhang, G.; Sun, T. Analysis of unsteady cavitation flow over hydrofoil based on dynamic mode decomposition. Chinese Journal of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics2020, 52, 1045-1054.

- Lu, J.; Liu, J.; Qian, L.; Liu, X.; Yuan, S.; Zhu, B.; Dai, Y. Investigation of Pressure Pulsation Induced by Quasi-Steady Cavitation in a Centrifugal Pump. Physics of Fluids 2023, 35.

- Sirovich L. Turbulence and the dynamics of coherent structures. I. Coherent structures. Quarterly of applied mathematics1987, 45, 561-571.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).