1. Introduction

According to flight conditions and mission requirements, the variable camber wing can smoothly and continuously deform its leading and trailing edges, maintain optimal aerodynamic performance and expand its flight envelope [

1], with its low energy consumption and high cruising efficiency, the variable camber wing has become a hot spot in the field of morphing aircraft design. In recent years, some companies such as Boeing, NASA, and Airbus have successively launched projects on Variable Camber Flexible Wings (VCFW) [0], the feasibility of smooth and continuous variable camber wings has been demonstrated through the use of smart materials and flexible structures.

The variable camber of the leading and trailing edges can transform the base airfoil into a laminar flow airfoil, which can enhance lift and reduce drag by increasing the airfoil camber. Currently, many researchers have conducted extensive studies focusing on the aerodynamic performance analysis and structural design of variable camber wings. Kaul et al. investigated the aerodynamic effects of trailing-edge camber in the Variable Camber Continuous Trailing Edge Flap (VCCTEF) project [

3], the results demonstrated that appropriate trailing-edge deflection improves the lift-to-drag ratio [

4,

5], however, excessive downward deflection angles increase drag. The computed lift increments showed good agreement with theoretical predictions. Focusing on drag reduction benefits, Ting E et al. conducted some experiments on the aerodynamic characteristics of variable camber trailing edges by using aerodynamic-structural modeling based on the vortex lattice method, which be combined with transonic small disturbance theory and boundary layer integral solutions. Compared to the basic wing, the results showed that the parabolic trailing-edge flap deflection with three curved segments reduced drag by 8.4% [

6]. Livne E et al. investigated the optimal trailing-edge deformation region for maximum drag reduction under varying flight conditions. They compared fuel consumption between uncoupled and aeroelastic-coupled scenarios. The results indicated that considering aeroelastic coupling reduced fuel consumption by 1.72% [

7]. Peter F N et al. proposed a geometric airfoil modification method to address the application of variable camber technology in aircraft design. This method improved the lift-to-drag ratio of the airfoil during cruise by 1.2% and reduced fuel consumption by 239 kg [

8]. Keidel D et al. proposed a novel structural deformation method to address the challenges faced in flight control of flying-wing aircraft. By optimizing internal flexible structures and electromechanical actuators, rear-edge deformation was achieved. The variable camber deformation predicted by numerical simulations was validated through experiments [

9,

10].

Some research achievements in airfoil optimization. Fakhari S. M. et al. investigated the improvement of aerodynamic performance for variable camber airfoils via taking NACA4412 and NACA2245 as research models. Through parameterized modeling with B-spline curves, an unconstrained conjugate gradient optimization algorithm was proposed, the lift-to-drag ratios of the two airfoils were improved by 13.7% and 32%, respectively [

11]. Bao N. et al. studied an optimization method for variable camber airfoils to enhance the flight efficiency of large aircraft based on deep neural networks (DNN) and the genetic algorithm. Using CFD simulations, the aerodynamic effects of leading edge and trailing edge camber variations were analyzed, and an iterative optimization framework was established by integrating DNN with Fluent validation. The optimization results showed an improvement in the airfoil's lift-to-drag ratio by over 14%. When extended to three-dimensional configurations, the optimized airfoil maintained similar aerodynamic performance trends [

12]. Wei N I U et al. addressed the challenge of improving aircraft aerodynamic performance under multiple flight conditions by conducting an in-depth analysis of the aerodynamic characteristics of trailing-edge camber variation technology. He proposed an airfoil optimization strategy incorporating variable camber technology. The study revealed that the optimized airfoil achieved lift coefficient improvements of 10% and 30% over the base airfoil under two flight conditions, significantly enhancing aerodynamic performance compared to traditional discrete shape optimization methods [

13]. Zhao A et al. designed a four-section optimized airfoil structure using a genetic algorithm, which can achieve overall camber variation. CFD simulations were conducted to analyze the aerodynamic performance of the variable camber airfoil. ,the results indicated that the variable camber airfoil exhibited better stall characteristics and achieved higher lift coefficients compared with the basic airfoil [

14]. Takahashi H et al. proposed a morphing wing design with two deformation sections: the leading and trailing edges, as well as the trailing edge alone, based on corrugated structures. Using finite element structural analysis and wind tunnel experiments under 20 m/s airflow, and the results showed that the measured deformation closely correlated with the simulated deformation [

15]. The studies aboved mainly focus on the impact of trailing edge camber variation on aerodynamic performance, while researches on the effects of leading edge deflection on airfoil aerodynamic performance remains relatively limited.

In recent years, the combination of surrogate modeling methods and optimization algorithms has been widely studied in the field of aircraft design, with the Kriging surrogate model is one them. Compared to other surrogate models, the Kriging model not only provides estimates of unknown functions but also gives an estimate of the associated error, making it one of the most representative surrogate modeling methods available today. Aleisa H et al. and Jesus T et al. focused on optimizing the maximum lift-to-drag ratio for UCAVs under low-speed conditions. They employed the Kriging surrogate model and vortex lattice method for multidisciplinary design optimization of UAVs. Through simulation calculations, they demonstrated the accuracy of the surrogate model [

16,

17]. Rajagopal S et al. addressed the multi-objective design optimization of low-speed, long-endurance UAV wings. He employed the Kriging surrogate model to replace high-fidelity analysis tools, reducing computational time, and solved the optimization problem using the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II). The results revealed multiple useful Pareto-optimal design solutions, which can guide the preliminary design of UAV wings. Significant research achievements have also been made in the surrogate model-based optimization design of airfoils [

18]. Weaver-Rosen J M et al. proposed a parameter optimization method for the continuous variable camber design of lightweight aircraft wings. They applied the Kriging surrogate model to the output of a genetic algorithm to obtain the optimal solution. The results indicated that the parameter optimization method had practical application in various operating conditions [

19]. Qiu Yasong et al. proposed a new method for supersonic airfoil optimization by combining orthogonal decomposition with data dimensionality reduction to construct a Kriging surrogate model. The results showed that this method reduced the number of design variables by 50% and improved optimization efficiency by 200% [

20]. Wang X et al .presented a deformation method that combines piezoelectric actuation with flexible dynamic shape control, based on the Kriging surrogate model and using only 150 sampling points. This approach provides an effective means for the rapid optimization of flexible trailing edge variable camber wings [

21]. Zhao Y et al. introduced the Kriging surrogate model into NSGA-II for aerodynamic optimization. They compared the optimization results of the RAE2822 airfoil at low Reynolds numbers in transonic and subsonic regimes and analyzed the mechanisms behind the airfoil's lift generation [

22]. Zhao X et al. addressed the multi-objective optimization problem in UAV flying wing control surface design by proposing a multi-objective control allocation method based on the Kriging surrogate model. This approach effectively solved the control allocation issue for UAV continuously deformable trailing edges [

23]. Ju S et al. proposed an optimization method based on particle swarm optimization algorithm combined with Kriging surrogate model for the design of high-lift devices. The method was used to optimize the parameters of flap configuration position, and the optimal flap deflection position was found with only a 1% loss in lift to drag ratio [

24]. Wauters J focused on the wingtip stall problem of blended wing body UAVs and integrated the Kriging surrogate model into robust design optimization techniques. The study identified airfoil design on the Pareto front that avoided wingtip stall while satisfying longitudinal static stability requirements [

25]. Du C et al. investigated variable camber airfoil design by combining the Xfoil application and Kriging surrogate model to elucidate the relationship between driving variables and airfoil aerodynamic characteristics. The results demonstrated a high sensitivity index of the angle of attack to aerodynamic performance [

26]. To improve the computational efficiency of aerodynamic shape optimization, Raul V et al. proposed a least squares programming technique based on the Kriging surrogate model. This approach helped delay and mitigate the dynamic stall characteristics of the airfoil [

27]. In summary, the current research primarily involves the following issues: (1) most optimization designs focus on fixed airfoils, with relatively few studies on variable camber airfoils; (2) the research on variable camber is mostly concentrated on the trailing edge, while there is relatively little research on the variable curvature of the leading edge; (3) Kriging surrogate model is predominantly used for single-objective optimization and it is rarely applied to multi-objective optimization design of airfoils with both leading edge and trailing edge variable camber. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a Kriging prediction model for the multi-objective optimization of airfoils with variable camber at both the leading and trailing edge.

This work focuses on the transonic airfoil RAE2822. First, the aerodynamic performance of the airfoil is analyzed by varying the camber of the leading and trailing edges. Then, a Kriging surrogate model is established with the leading and trailing edge deflection angles as input variables and the lift coefficient and drag coefficient as output variables. Using NSGA-II multi-objective optimization, the optimal airfoil configurations for three Mach numbers are obtained, with the goals of minimizing the drag coefficient and maximizing the lift-to-drag ratio. Finally, the errors between the predicted optimization model and the optimized CFD model are compared, demonstrating the high reliability of the surrogate model and significant improvements in computational efficiency.

2. Computational Model

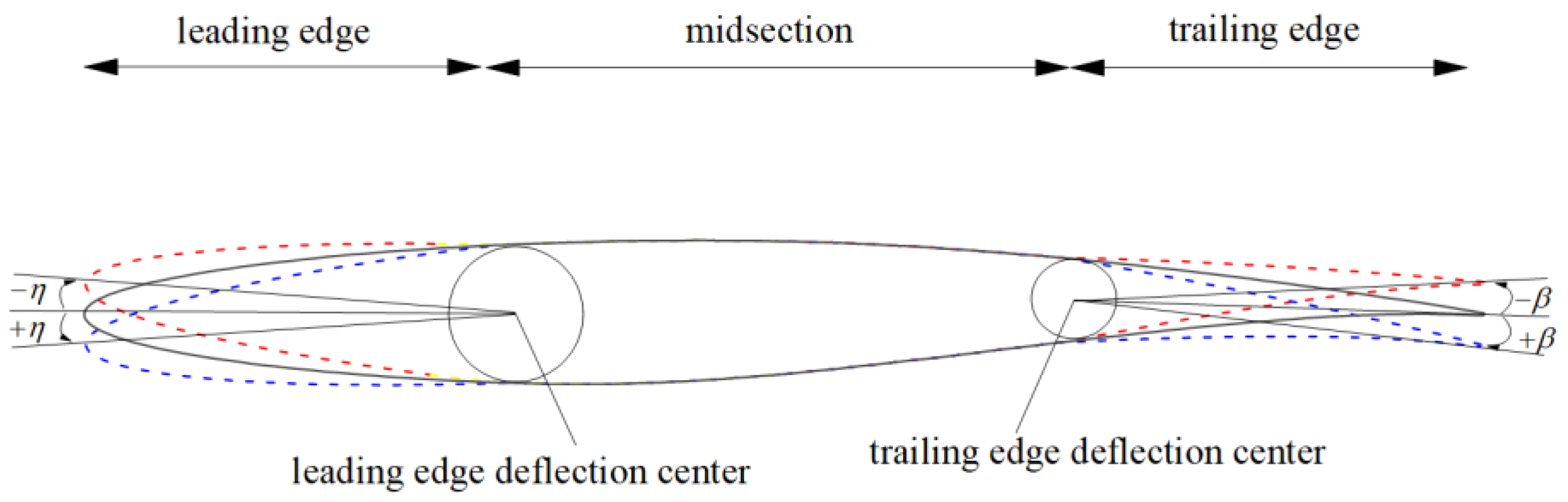

According to the VCCTEF [

5], NASA concluded that the layout of using the middle arc of the airfoil as a parabolic trajectory to change curvature is optimal in improving cruising aerodynamic performance. Based on this method, this work takes the RAE2822 transonic airfoil as the research object, with the deflection centers for variable camber located at 30% of the chord length on both the leading and trailing edges. The deformable section of the leading edge ranges from 20% to 40% of the chord length, while the deformable section of the trailing edge ranges from 60% to 80% of the chord length. The deformation curve is smoothly transitioned using B-spline interpolation.

Figure 1 shows the schematic of the leading and trailing edges camber variation for the transonic airfoil. The leading edge deflection angle is denoted as

η, and the trailing edge deflection angle is denoted as

β, where upward deflection is represented by sign "-" and downward deflection by sign "+" .

To solve transonic viscous flows, the two-dimensional steady-state compressible RANS equations are used, with numerical solutions obtained through the finite volume method. Spatial discretization is performed using a second-order upwind scheme. The turbulence model selected is the Spalart-Allmaras (SA) one-equation model, which is suitable for simulating the interaction between surface shock waves and boundary layers. The far-field boundary conditions are set as follows: a pressure far-field boundary is applied at the inlet, and a pressure outlet boundary is applied at the outlet. The actual reference chord length of the airfoil is 1000 mm, and the distance from the airfoil to the far-field boundary is set to 15 times the reference chord length. Based on the modified inflow parameters from the EUROVAL project for Test Case 9 [

28], the incoming flow conditions for the calculations are to established that incoming Mach number

Ma = 0.73, the angle of attack

α = 2.54°, and Reynolds number

Re = 6.5×10

6. The grid adopts a C-type structured mesh, which has been densified on the airfoil surface and both the leading and trailing edges. Mesh independence studies were conducted using 50,000, 100,000, 150,000 and 200,000 meshes.

Figure 2 shows the near-wall mesh for the case with 150,000 grid points, where the height of the first mesh layer is 1×10

-6 m, and the wall-normal mesh spacing (y+) < 1.

Table 1 shows compares of the aerodynamic coefficients obtained from different mesh resolutions with experimental results [

29]. The difference in aerodynamic coefficients between the 150,000-grid and 200,000-grid cases is less than 0.5%, which verifies that the aerodynamic coefficients are independent of the mesh density, confirming that mesh independence has been achieved.

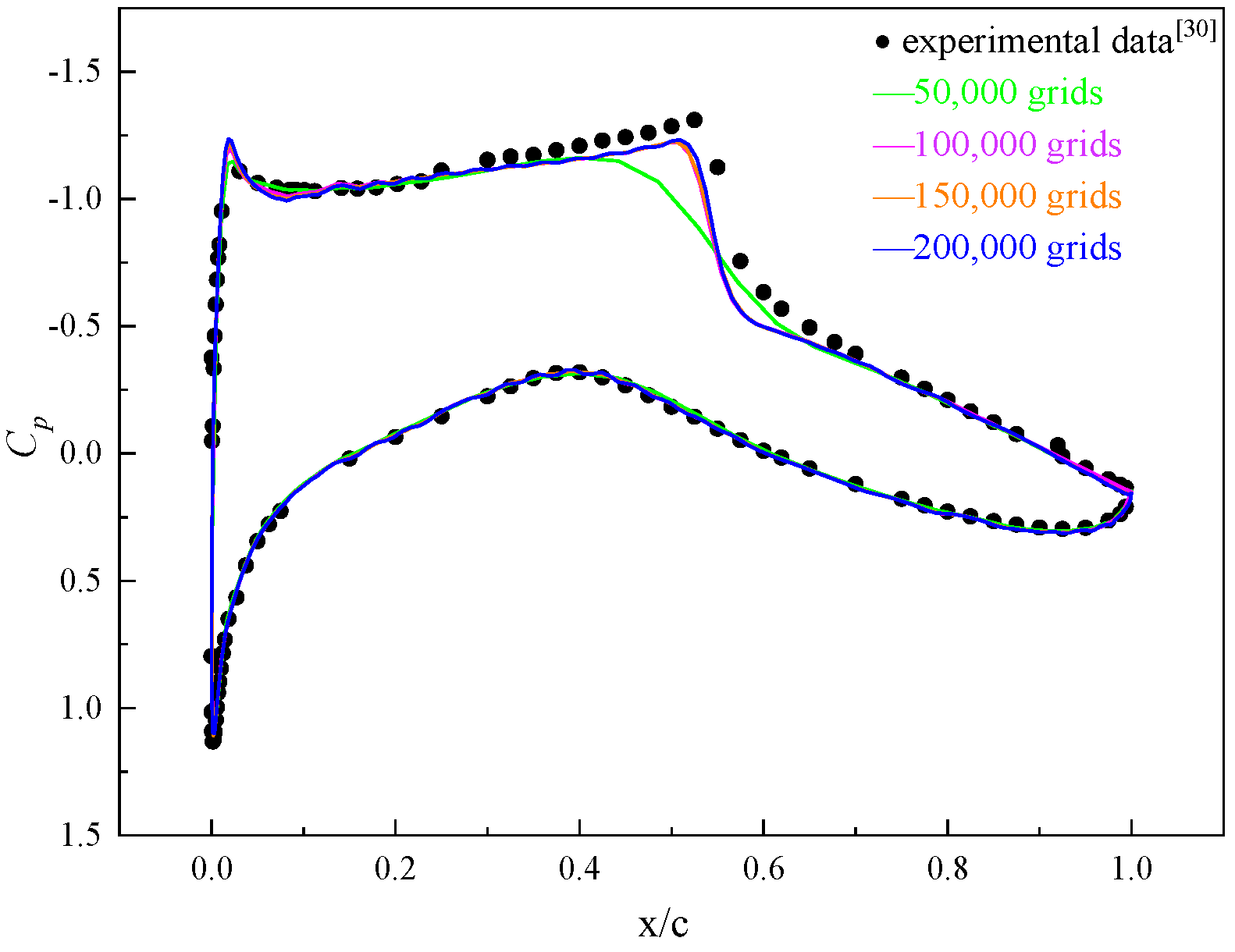

The curves of the pressure coefficient

CP for different mesh resolutions are shown in

Figure 3. It can be seen from the figure that the pressure coefficients are relatively close to the experimental data. However, the 50,000-grid can not capture the shock wave clearly. From

Table 1 and

Figure 3, it can be observed that the 100,000, 150,000, and 200,000 grids are in good agreement with the experimental values and are capable of accurately reflecting the flow field. Considering both computational accuracy and efficiency, the 150,000-grid resolution is chosen for the simulation calculation.

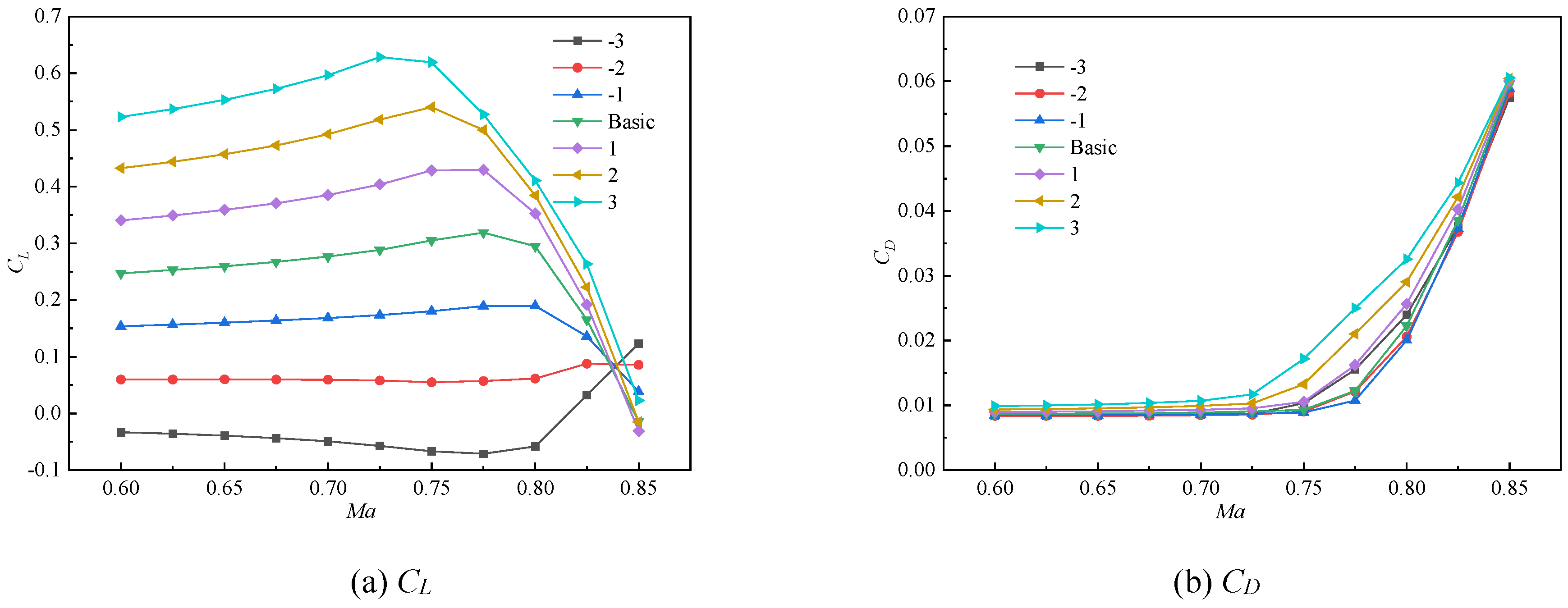

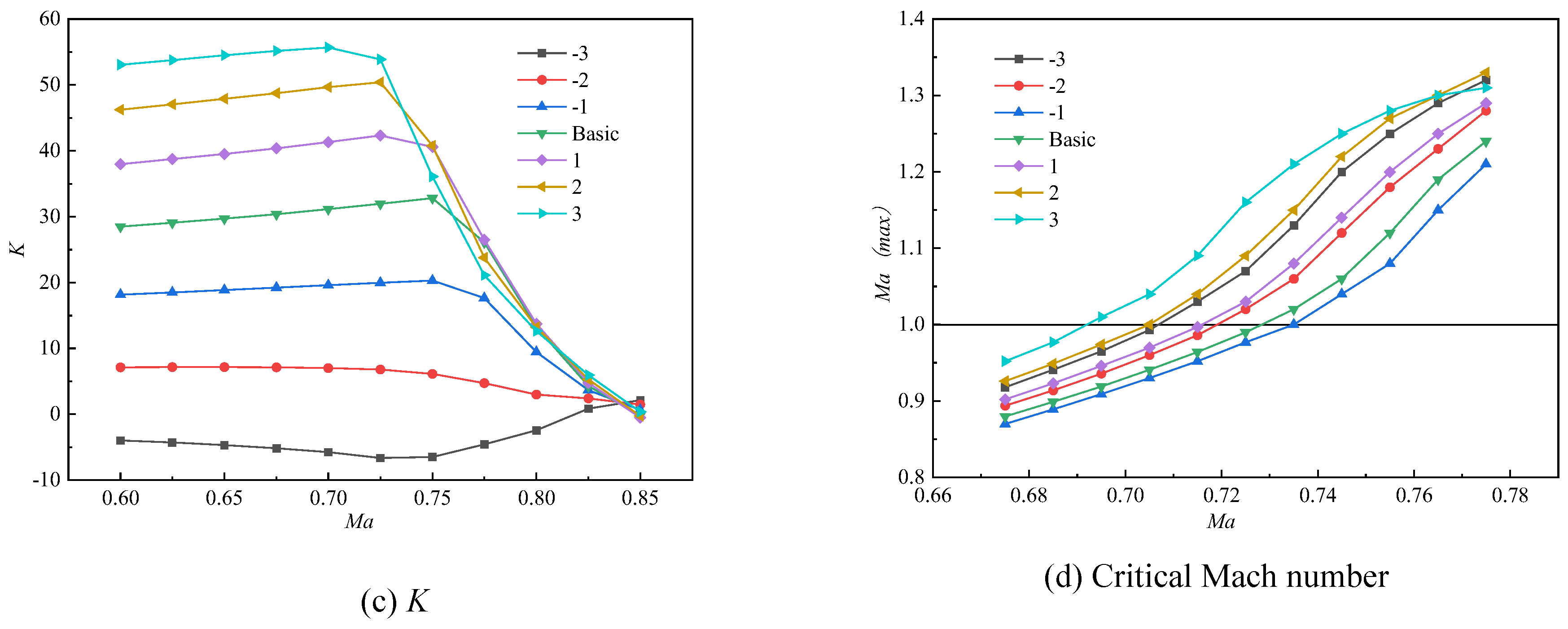

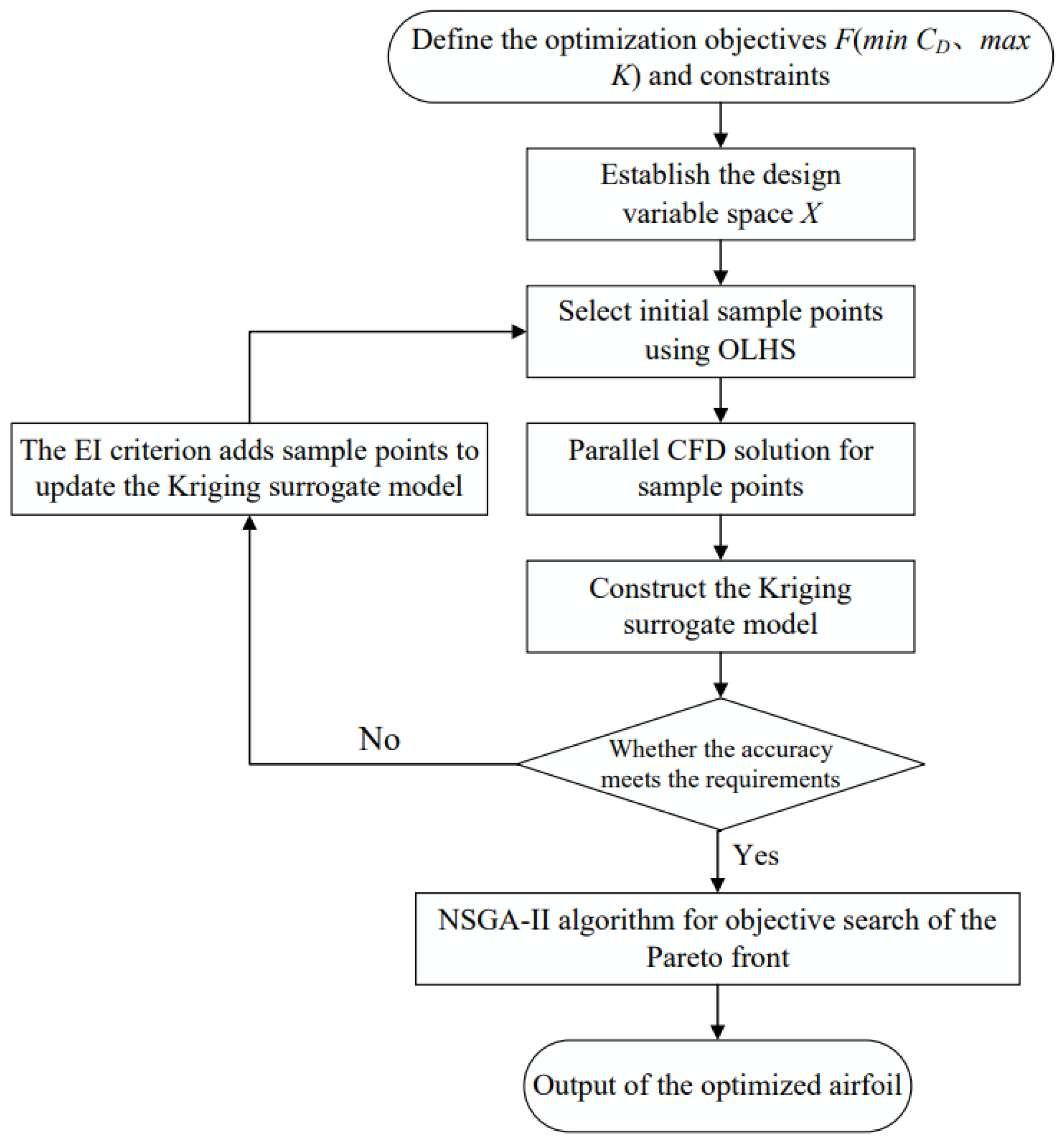

4. Multi-Objective Airfoil Optimization Based on the Kriging Surrogate Model

From the aerodynamic analysis above, it is known that the critical Mach number of the RAE2822 airfoil is 0.73 with

Re = 1.7×10

7,

α = 2°(Figure9(d)). To improve the aerodynamic characteristics of the airfoil in flight conditions beyond the critical Mach number, three different flight states at

Ma = 0.74, 0.75 and 0.76 will be selected for multi-objective optimization. Compared to the traditional Genetic Algorithm (GA), NSGA-II can optimize multiple objective functions simultaneously through fast non-dominated sorting and crowding distance calculation. It generates a Pareto optimal solution set with good diversity and uniform distribution, making it easier to achieve diversity, uniformity and robustness in the solution set [

30]. By using the surrogate model to the optimization process and combining it with NSGA-II to improve optimization efficiency and find the Pareto optimal solution set of the objective function. The optimization process is illustrated in

Figure 10.

1. Define the optimization objective functions F(min CD, max K) and design constraints, and establish the design space X for the leading and trailing edge deflection.

2. Select initial sample points using the optimal Latin hypercube sampling method, and perform parallel CFD calculations to obtain the performance data.

3. In the surrogate model construction process, the Expected Improvement (EI) criterion is used to guide the automatic dynamic addition of sample points, and EI < 10-3 is used as the convergence criterion to improve the accuracy of the Kriging surrogate model.

4. Use the NSGA-II algorithm for optimization, generate the Pareto solution set, and select the optimal solutions on the Pareto front as the final optimized airfoil configuration.

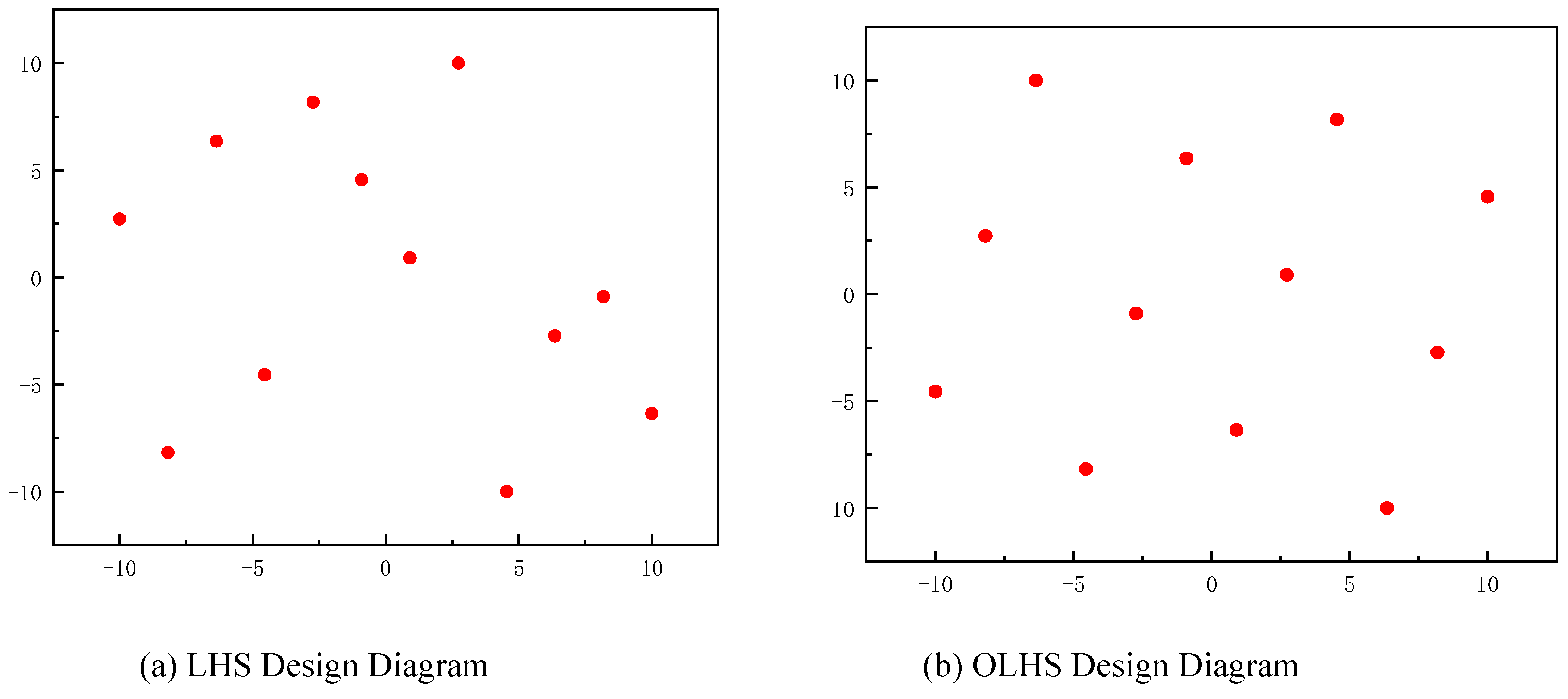

4.1. Optimal Latin Hypercube Sampling Design

Optimal Latin Hypercube Sampling (OLHS) is an improved version of the Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) method, it is used to efficiently generate sample points in a multidimensional parameter space for more comprehensive coverage of the parameter space [

31]. The basic principle is to maximize the minimum distance between any two sample points through the optimization algorithm, which can prevent samples from clustering in certain areas, and make the distribution of generated sample points more uniform, for improving the accuracy of the initial model. OLHS achieves effective coverage of multi-dimensional parameter spaces, reduces sampling bias, and improves the accuracy of the analysis results. Before constructing the Kriging surrogate model, it is necessary to sample the design space.

Figure 11 compares LHS and OLHS sampling. As shown in the figure, the sample points from OLHS are more evenly distributed.

4.2. Kriging Surrogate Model Construction

For a real function

, the Kriging surrogate model can be written as:

Where

is an unknown function of

and represents the global simulation of the design space.

can be considered as a constant and replaced by

;

is a Gaussian normal random function with a mean of 0 and a variance of

and denotes the deviation from the global simulation. So expression (1) is estimated from the determined response values:

The covariance matrix of

is as follows:

where

is a diagonal symmetric correlation matrix, the correlation matrix,

is a selectable correlation function,

,

,

is the number of known response data points. The correlation function

can be expressed an isotropic Gaussian exponential function

where

is a scalar coefficient,

is the number of design variables, and the predicted estimate

of the response value

is given

where

is a column vector of length

, which contains the response values corresponding to the sample data. When

is a constant,

is a unit column vector of length

.

is the correlation vector among the sample data

of length

.

In Eq (5),

is estimated:

The estimated value of the variance

, denoted as

, which is given by

and

.

In Eq (4), the related parameter

is given by the maximum likelihood estimation, which maximizes the following expression when

>0.

and

are functions of

.

The root mean square error (RMSE) and the coefficient of determination (R2) are used to evaluate the predictive performance of the model in this paper.

The expression for

RMSE is as follows:

where

represents the true value at point

, while

is the predicted value by the surrogate model at point

.

is the number of sample points used for the surrogate model. The higher the prediction accuracy of the surrogate model, the smaller its value will be.

The expression for

R2 is as follows:

represents the average of the true outputs for all sample points of the surrogate model. The higher the prediction accuracy of the surrogate model, the closer its value is to 1.

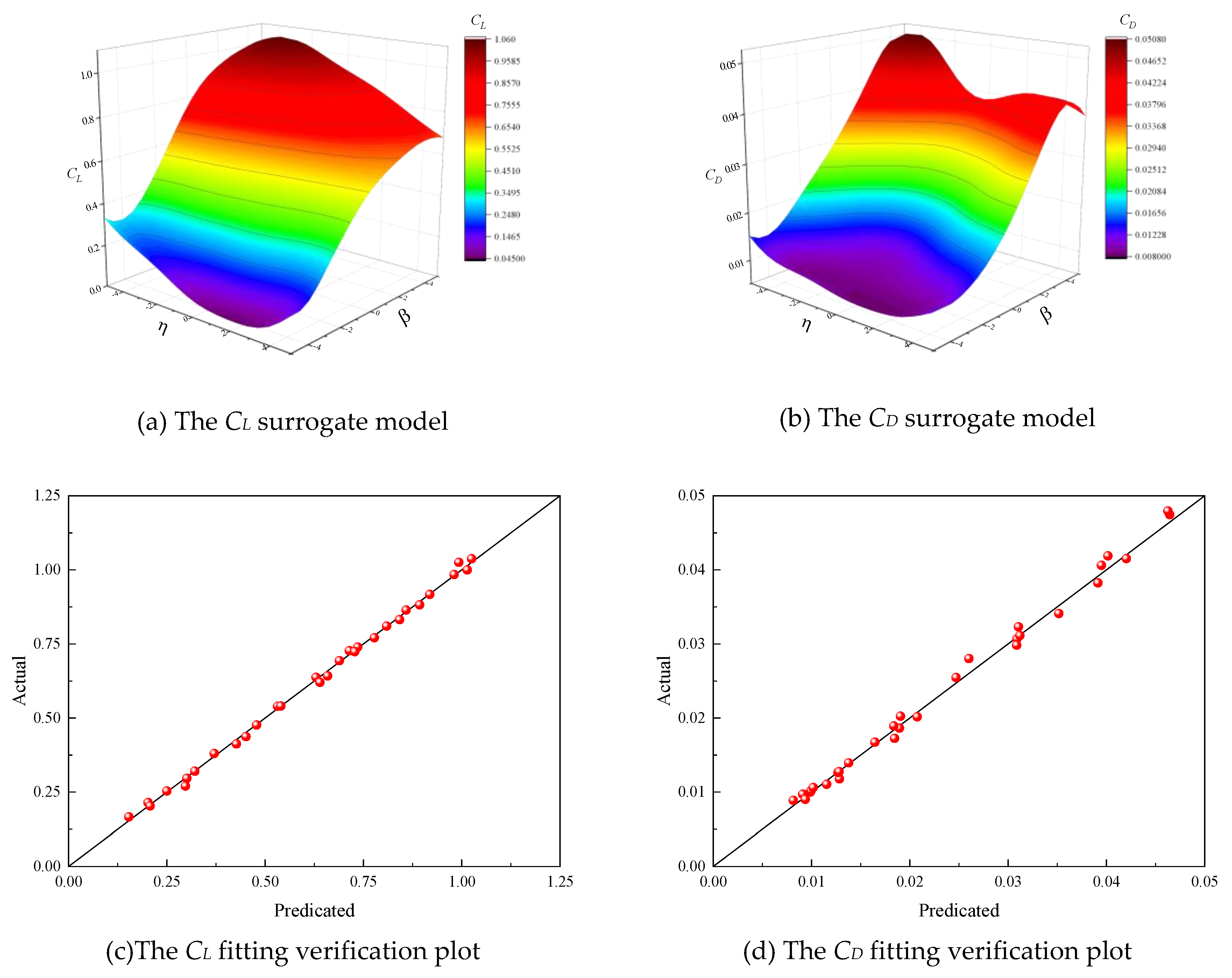

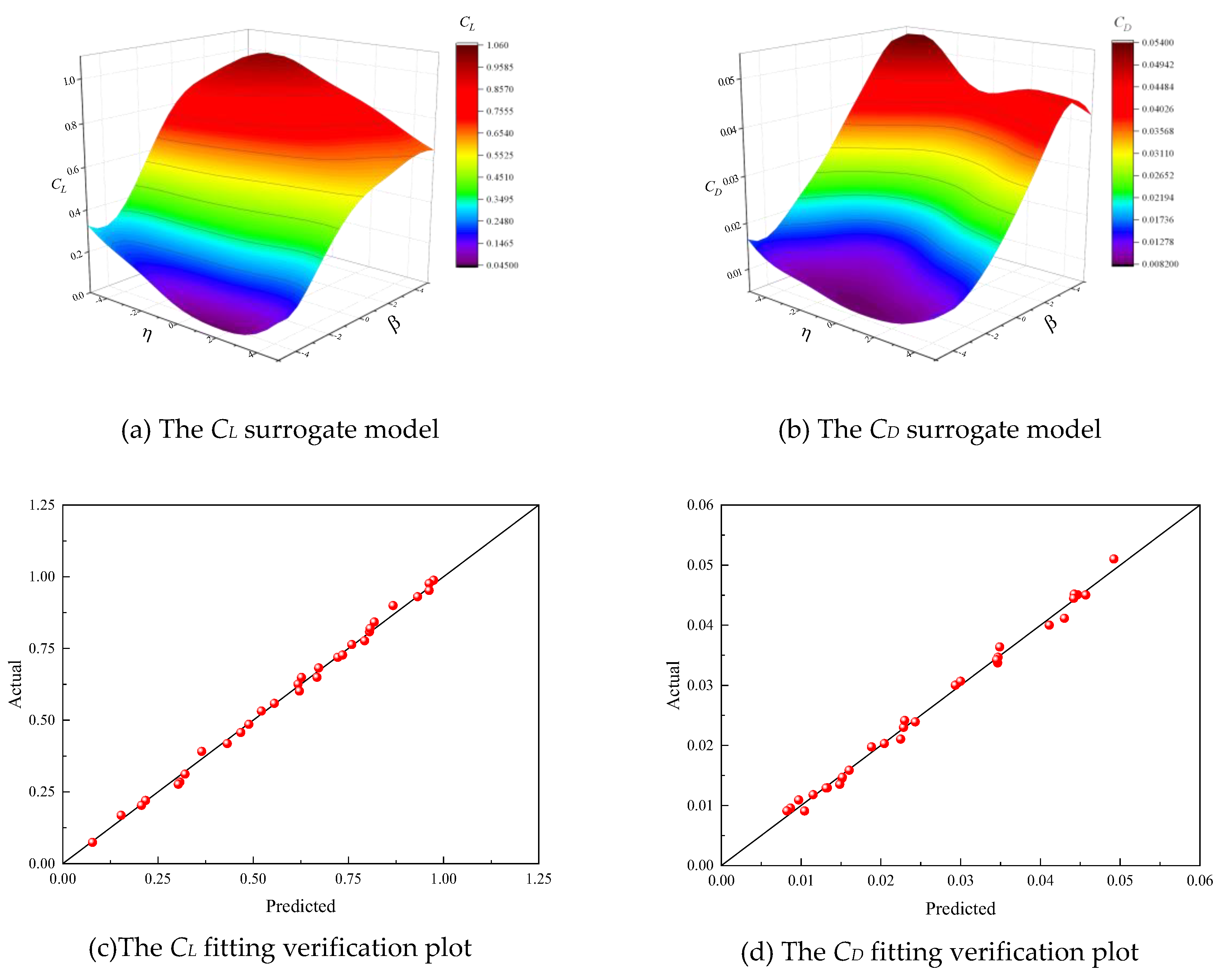

4.3. Kriging Surrogate Model Interpolation Accuracy Verification

The OLHS was performed on the leading and trailing edge deflection angles, with sampling ranges [-5°, 5°] for both deflections. Based on the EI criterion, 30 sample points were sampled under three different flight conditions to meet the accuracy requirements. The aerodynamic Kriging surrogate model was then fitted. According to Eqs (10) and (11), the fitting accuracy is shown in the

Table 2. The values of

R2 for three Mach numbers are greater than 0.9, and the values of

RMSE are less than 0.1, the results demonstrate that the surrogate model has high reliability in handling complex aerodynamic data.

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 show the aerodynamic coefficient surrogate models and fitting validation plots for

Ma = 0.74, 0.75 and 0.76. The

CL and

CD surrogate models are in good agreement with the aerodynamic analysis results (

Figure 6 and

Figure 9). The solid line in the fitting validation plots represents the line where the true values are equal to the predicted values. The closer the sample points are to this solid line, the smaller the prediction deviation, the more accurate the model.. The proportion of high-confidence sample points exceeds 95% for three Mach numbers.

4.4. Multi-Objective Optimization

In the optimization process for three Mach numbers, the NSGA-II algorithm are set with a population size of 40, evolutionary generations of 100, crossover probability of 0.9, and mutation probability of 0.01. If the optimization is performed by iterating in a sequential loop, the number of calls to the numerical model will reach up to 4000 times. In contrast, the optimization process based on the Kriging surrogate model only required 30 times to the numerical model, significantly reducing the computational load and improving the efficiency of the variable camber optimization.

The optimization model for

Ma = 0.74、0.75 and 0.76 are as follows:

Where

represents the optimization objective,

denotes the design space, and

represents the constraints.

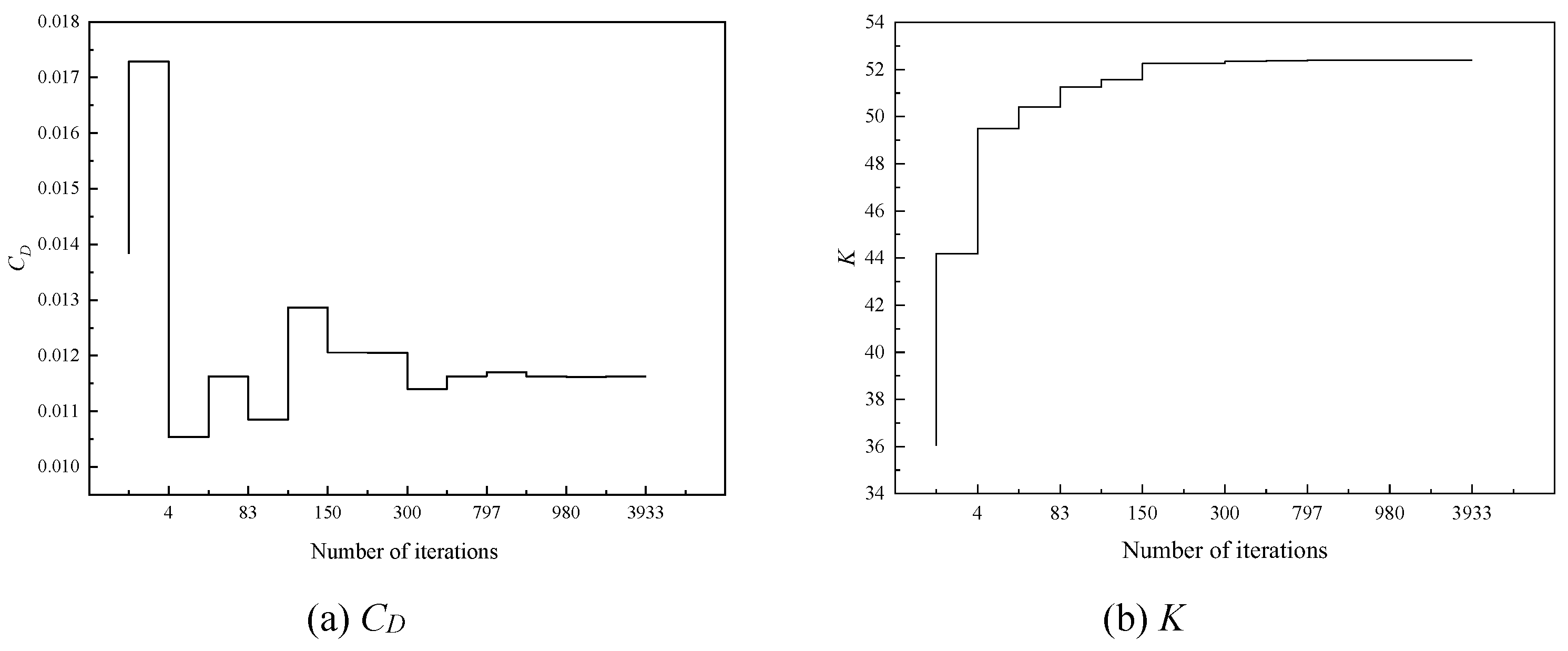

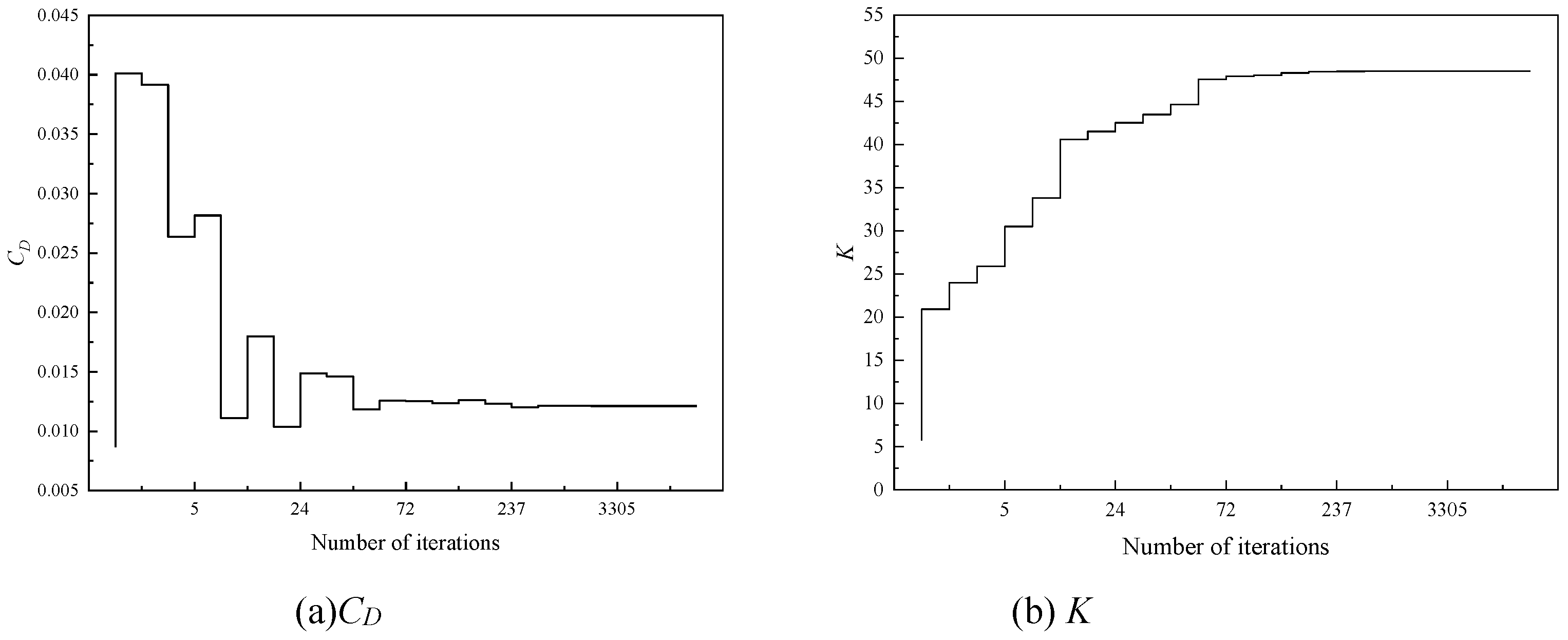

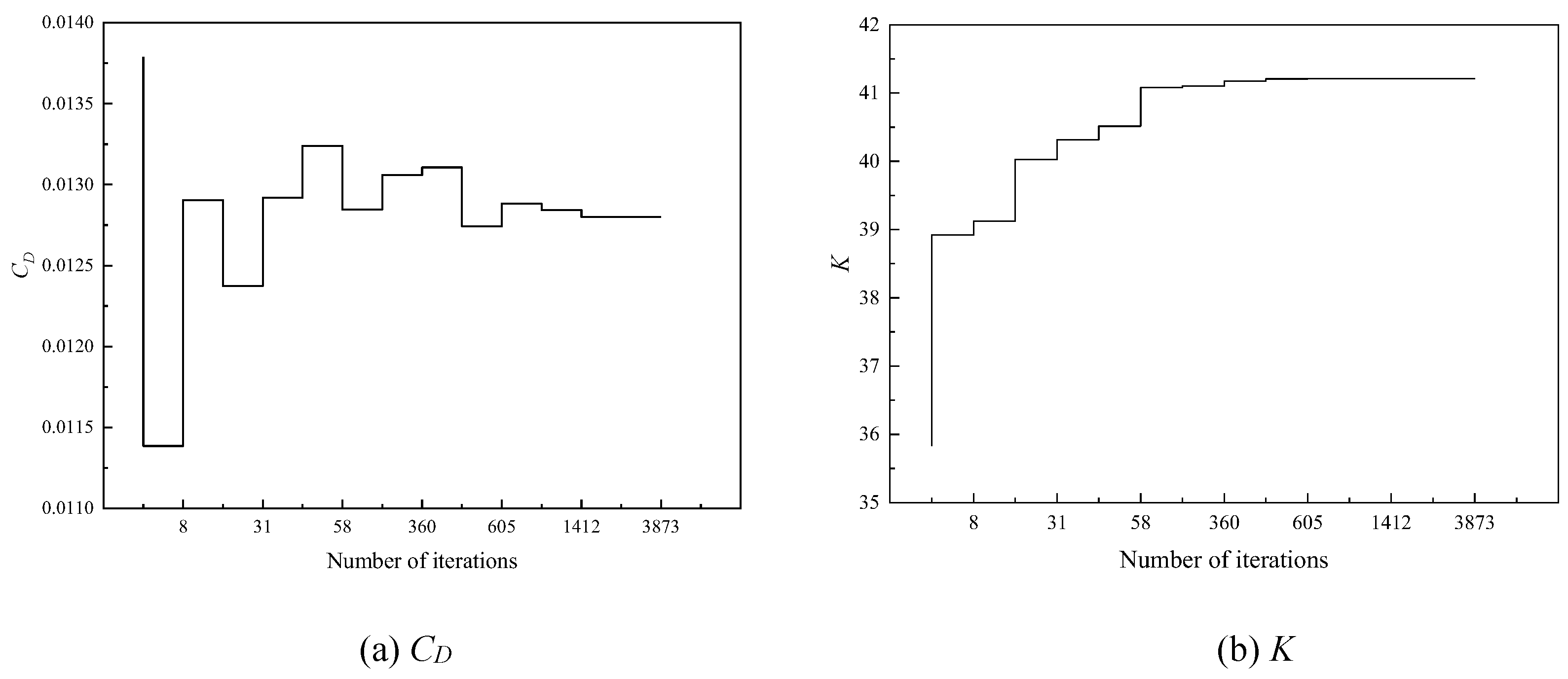

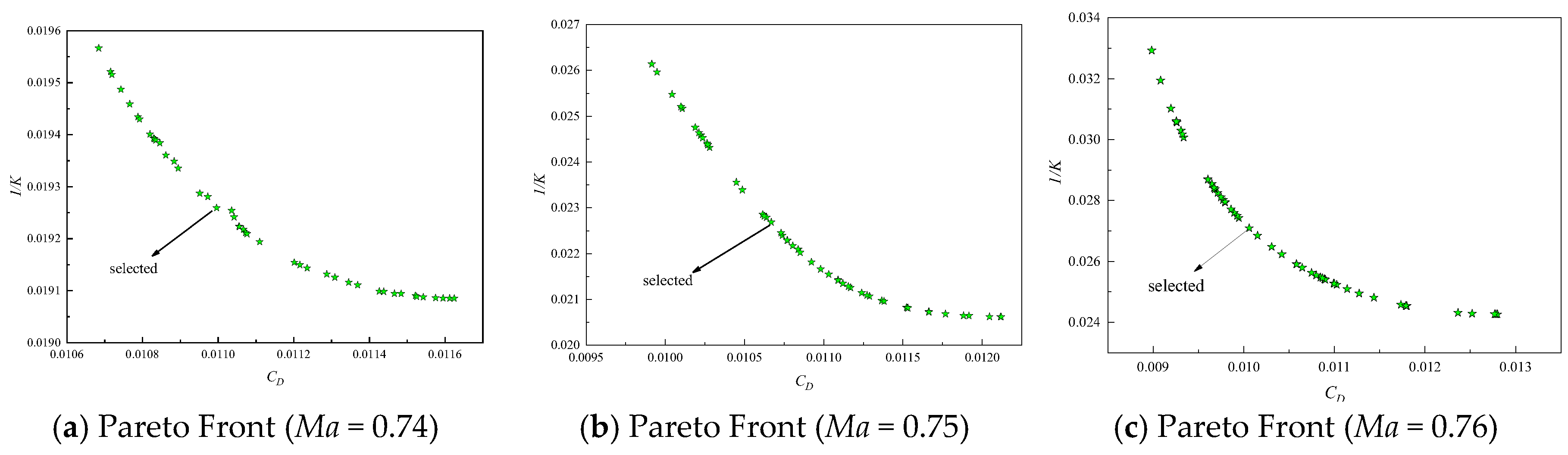

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 show the convergence process of the objective function during the optimization process for three Mach numbers. The two objective functions in each case converged after 864, 1205, and 1412 iterations, respectively. The points marked as "select" are the optimal combinations selected from the Pareto front for three Mach numbers, as shown in

Figure 18.

The geometric design parameters for selecting the optimal combination at three Mach numbers,

=-0.94°, -0.85°, and -1.08°,

=-0.95°, -1.98°, and -2.81°, respectively. Based on the above geometric design parameters, the optimization results are shown in

Table 3. It can be observed that the deviation between the surrogate model optimization and the CFD optimization results is less than 6%. The results indicate that the Kriging surrogate model has high prediction accuracy, meets the requirements for aerodynamic layout parameter matching, and successfully achieves the optimization expectations.

In the three flight conditions, the

CD decreased by 22.92%, 43.88%, and 56.31% , and the

K increased by 11.13%, 20.65%, and 24.89%, respectively, the results achieved the desired multi-objective aerodynamic performance optimization. The pressure nephograms before and after optimization are shown in

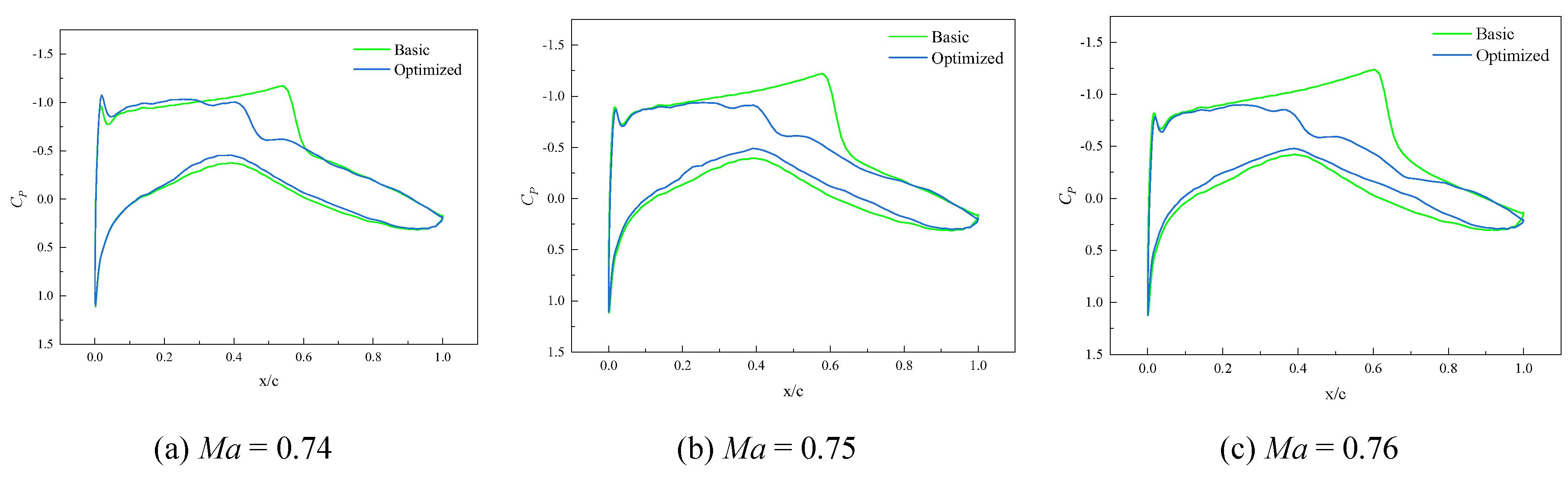

Figure 21. From the pressure nephogram of the basic airfoil, it can be seen that there is a relatively obvious shock wave structure near the trailing edge of the upper surface of the airfoil. The shock wave intensity is relatively strong, forming a clear pressure jump region. The formation of the shock leads to higher shock-induced drag. From the pressure nephogram of the optimized airfoil, it can be seen that the shock wave intensity on the upper airfoil surface is significantly reduced, the shock wave is no longer concentrated in a certain position, the pressure jump region disappears, and the shock wave resistance also decreases accordingly. The pressure coefficient distributions before and after optimization are shown in

Figure 22. Before optimization, a rapid decrease in pressure coefficient near the trailing edge can be observed. This steep slope change indicates that the airflow is strongly compressed in the shock region, resulting in higher shock resistance. After optimization, it can be observed that the pressure coefficient distribution becomes smoother on the upper surface, which means that the intensity of the shock wave is weakened, the degree of airflow compression is reduced, and the wave resistance caused by the shock wave is reduced. At the same time, the change in pressure coefficient on the lower surface before and after optimization is not obvious, indicating that the optimization design mainly affects the upper surface of the airfoil. In summary, the optimized airfoil effectively reduces the drag caused by shock waves during high-speed cruise, significantly improving the aerodynamic performance of the wing.

5. Conclusions

For the transonic airfoil RAE2822, the aerodynamic effects of variable camber at the leading and trailing edges are analyzed using CFD methods. An aerodynamic multi-objective optimization design approach is developed based on the Kriging surrogate model and NSGA-II algorithm, following conclusions were achieved:

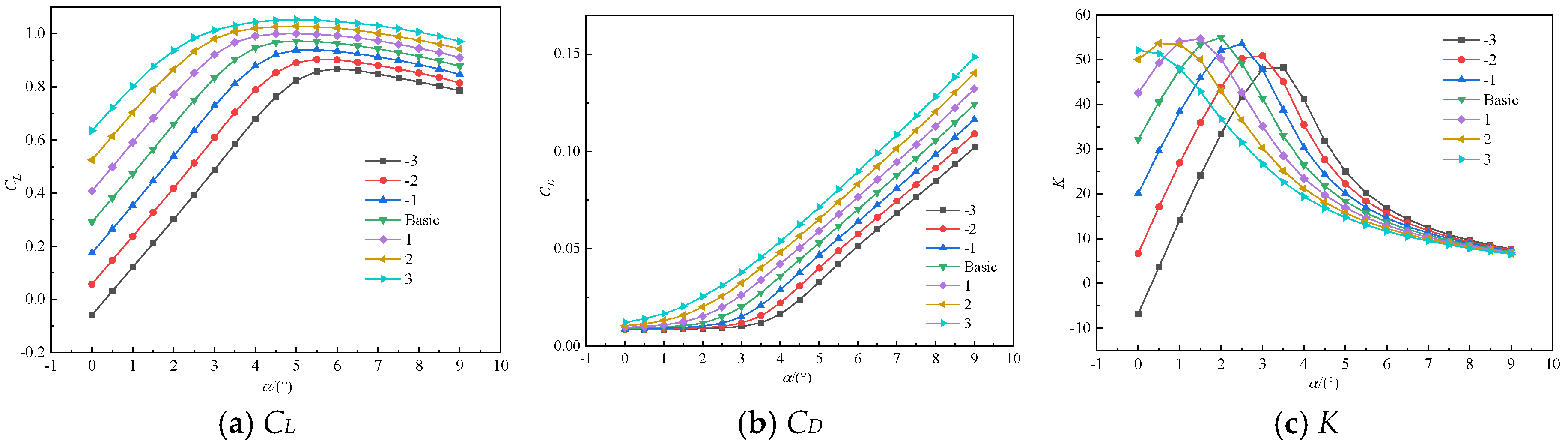

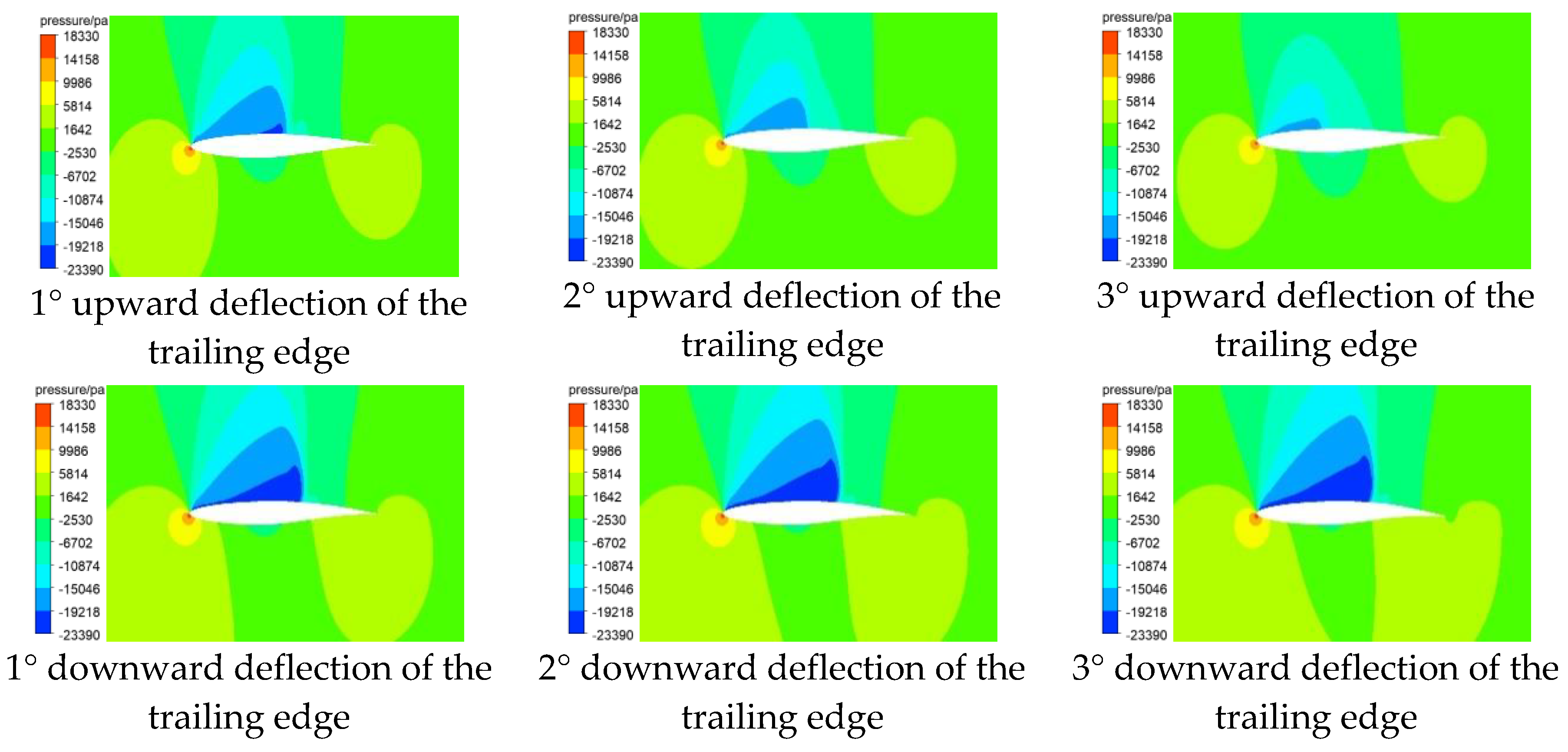

(1) The upward deflection of the leading edge moderately increased the lift-to-drag ratio, while the downward deflection of the leading edge improved the critical angle of attack and enhanced the airfoil's stall characteristics. The trailing edge deflection has little influence on the critical angle of attack, however the downward deflection of the trailing edge increased the lift coefficient. Moderate upward deflection of both the leading and trailing edges can delay the critical Mach number, while downward deflections of the leading and trailing edges cause the critical Mach number to decrease, which is unfavorable for the aircraft's performance at high speed flight.

(2) Optimal Latin Hypercube Sampling (OLHS) was used to sample the leading and trailing edge deflection angles. Aerodynamic coefficient Kriging surrogate models were established for Ma = 0.74, 0.75, and 0.76. The prediction deviations of the aerodynamic coefficients were fitted and tested, and the R² of the surrogate models were found to be greater than 0.9, while the RMSE was less than 0.1. These results indicate that the surrogate models meet the required accuracy standards.

(3) The optimization process reduced the number of numerical model calls by combining the Kriging surrogate model with NSGA-II, thus the efficiency of multi-objective optimization is improved. For the optimized airfoils at Ma = 0.74, 0.75, and 0.76, the shock wave strength was significantly weakened. The CD decreased by 22.92%, 43.88%, and 56.31%, respectively, while the K increased by 11.13%, 20.65%, and 24.89%, respectively, resulting in improved aerodynamic performance of the airfoils.

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of Leading and Trailing Edge Variable Camber for Transonic Airfoils.

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of Leading and Trailing Edge Variable Camber for Transonic Airfoils.

Figure 2.

Near-Wall CFD Mesh Model.

Figure 2.

Near-Wall CFD Mesh Model.

Figure 3.

Pressure Coefficient Curves for Different Grid Numbers.

Figure 3.

Pressure Coefficient Curves for Different Grid Numbers.

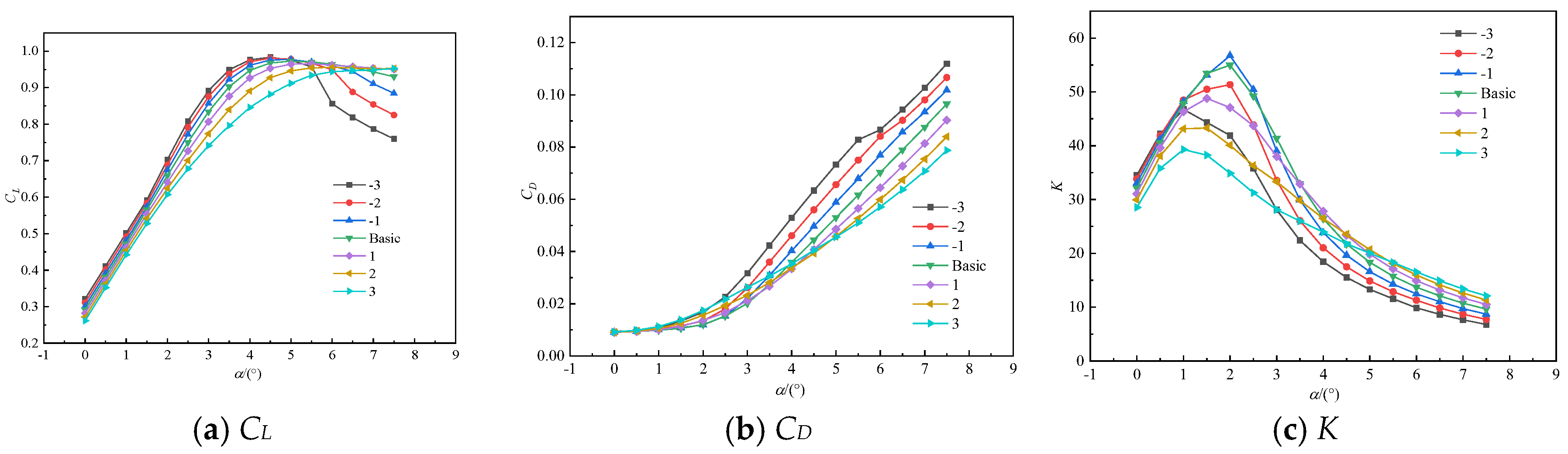

Figure 4.

Effect of Leading-Edge Deflection on the Aerodynamic Performance of Airfoils.

Figure 4.

Effect of Leading-Edge Deflection on the Aerodynamic Performance of Airfoils.

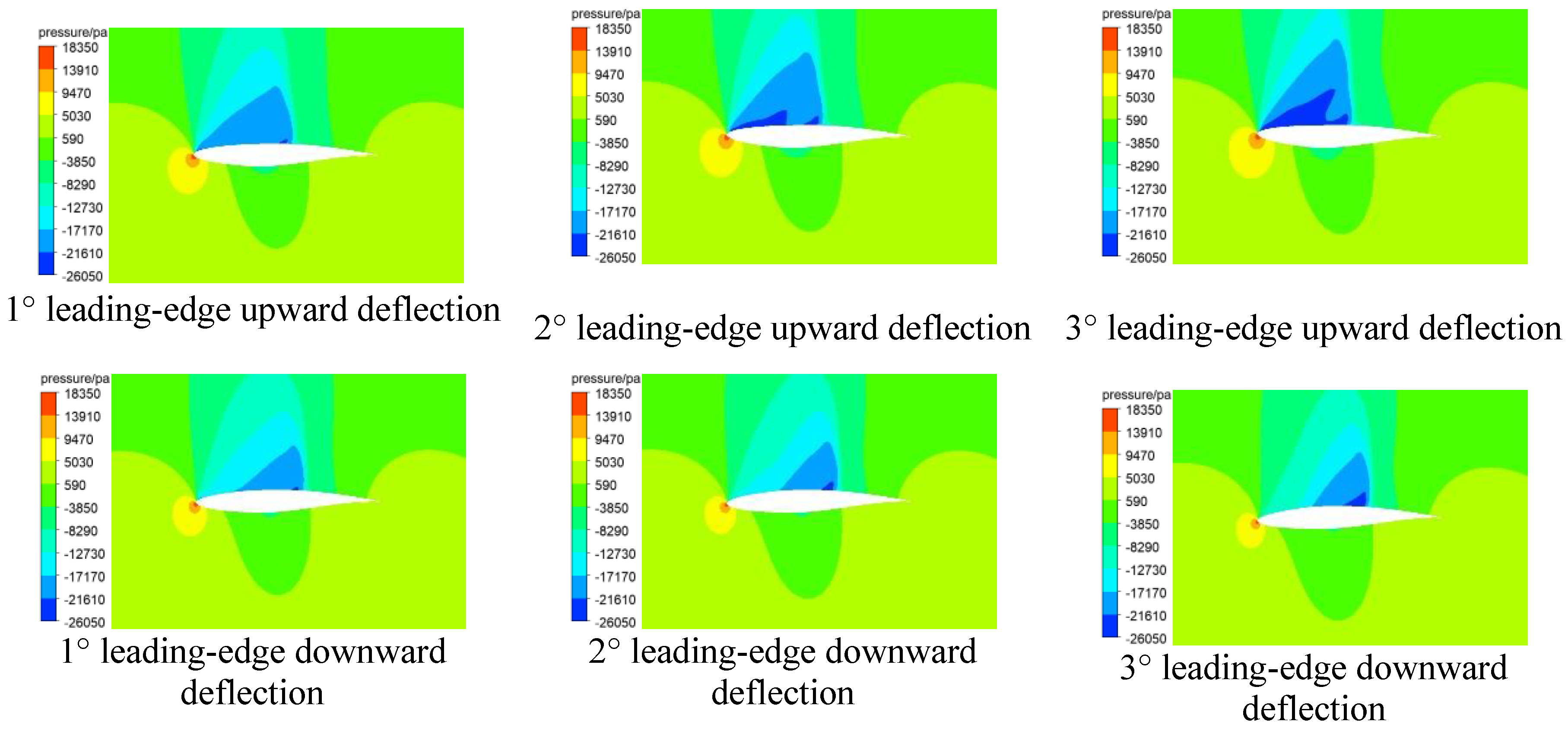

Figure 5.

Leading edge deflection pressure nephograms.

Figure 5.

Leading edge deflection pressure nephograms.

Figure 6.

Aerodynamic Performance of Leading Edge Deflection at Different Mach Numbers.

Figure 6.

Aerodynamic Performance of Leading Edge Deflection at Different Mach Numbers.

Figure 7.

Effect of Trailing-Edge Deflection on the Aerodynamic Performance of Airfoils.

Figure 7.

Effect of Trailing-Edge Deflection on the Aerodynamic Performance of Airfoils.

Figure 8.

Trailing edge deflection pressure nephograms.

Figure 8.

Trailing edge deflection pressure nephograms.

Figure 9.

Aerodynamic Performance of Trailing Edge Deflection at Different Mach Numbers.

Figure 9.

Aerodynamic Performance of Trailing Edge Deflection at Different Mach Numbers.

Figure 10.

Flowchart of Multi-Objective Optimization for Variable-Camber Airfoils.

Figure 10.

Flowchart of Multi-Objective Optimization for Variable-Camber Airfoils.

Figure 11.

Comparison of Two Sampling Designs.

Figure 11.

Comparison of Two Sampling Designs.

Figure 12.

Surrogate Model of Aerodynamic Coefficients and Fitting Validation Plot at Ma = 0.74.

Figure 12.

Surrogate Model of Aerodynamic Coefficients and Fitting Validation Plot at Ma = 0.74.

Figure 13.

Surrogate Model of Aerodynamic Coefficients and Fitting Validation Plot at Ma = 0.75.

Figure 13.

Surrogate Model of Aerodynamic Coefficients and Fitting Validation Plot at Ma = 0.75.

Figure 14.

Surrogate Model of Aerodynamic Coefficients and Fitting Validation Plot at Ma = 0.76.

Figure 14.

Surrogate Model of Aerodynamic Coefficients and Fitting Validation Plot at Ma = 0.76.

Figure 15.

Convergence Process (Ma = 0.74).

Figure 15.

Convergence Process (Ma = 0.74).

Figure 16.

Convergence Process (Ma = 0.75).

Figure 16.

Convergence Process (Ma = 0.75).

Figure 17.

Convergence Process (Ma = 0.76).

Figure 17.

Convergence Process (Ma = 0.76).

Figure 21.

pressure nephogram of the Airfoil Before and After Optimization.

Figure 21.

pressure nephogram of the Airfoil Before and After Optimization.

Figure 22.

Pressure Coefficient Curves of Basic Airfoil and Optimized Airfoil.

Figure 22.

Pressure Coefficient Curves of Basic Airfoil and Optimized Airfoil.

Table 1.

Aerodynamic Coefficients with Different Grid Resolutions.

Table 1.

Aerodynamic Coefficients with Different Grid Resolutions.

| Number of grids |

Lift coefficient CL |

Drag coefficient CD

|

Pitching moment coefficient CM

|

| Experiment [29] |

0.803 |

0.0168 |

-0.099 |

| 50000 |

0.731279 |

0.016198 |

-0.08786 |

| 100000 |

0.748625 |

0.016247 |

-0.09152 |

| 150000 |

0.749577 |

0.016465 |

-0.09343 |

| 200000 |

0.759939 |

0.016505 |

-0.09389 |

Table 2.

Accuracy of Fitting for 30 Sampling Points.

Table 2.

Accuracy of Fitting for 30 Sampling Points.

| Flight Mach number |

Types of Errors |

Fit Accuracy of CL |

Fit Accuracy of CD

|

|

Ma=0.74 |

RMSE |

0.05614 |

0.06679 |

| R2 |

0.96384 |

0.9575 |

|

Ma=0.75 |

RMSE |

0.05773 |

0.06787 |

| R2 |

0.96108 |

0.95705 |

|

Ma=0.76 |

RMSE |

0.06099 |

0.06293 |

| R2 |

0.9551 |

0.96267 |

Table 3.

Optimization Results.

Table 3.

Optimization Results.

| Ma |

Aerodynamic coefficients |

Basic airfoil

|

Surrogate model

Optimization |

CFD Optimization |

Surrogate model prediction error rate δ% |

Improvement percentage ε % |

| 0.74 |

CD |

0.0144 |

0.0110 |

0.0111 |

0.90 |

-22.92 |

| K |

46.846 |

51.923 |

52.060 |

0.26 |

+11.13 |

| 0.75 |

CD |

0.0180 |

0.0107 |

0.0101 |

5.94 |

-43.88 |

| K |

37.636 |

44.077 |

45.409 |

2.93 |

+20.65 |

| 0.76 |

CD |

0.0222 |

0.0101 |

0.0097 |

4.12 |

-56.31 |

| K |

30.098 |

36.909 |

37.590 |

1.81 |

+24.89 |