Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. UV-Vis Spectroscopy Study of the Degradation of DA.

2.3. Preparation and UV-Vis Spectroscopy Study of DA-Encapsulated DOPC Vesicles

2.4. Ascorbic Acid (AA) Oxidation Rate

2.5. Study of the Total Free Radical Formation from Fe3+-Catalyzed AA Degradation

2.6. Scavenging Capacity of IP6 Against HO· Radical

2.7. Fibril Formation from Human α-Synuclein (αS)

3. Results

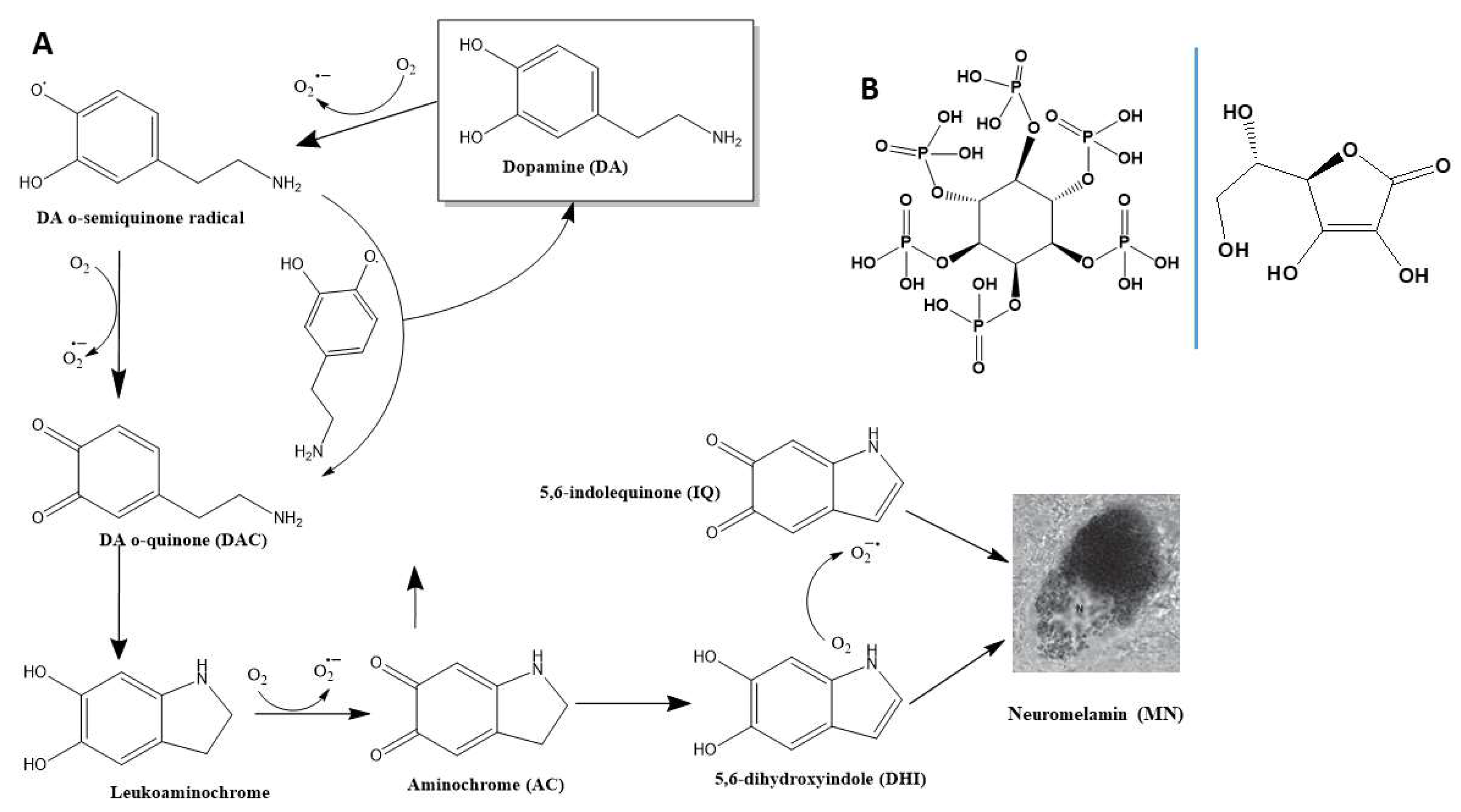

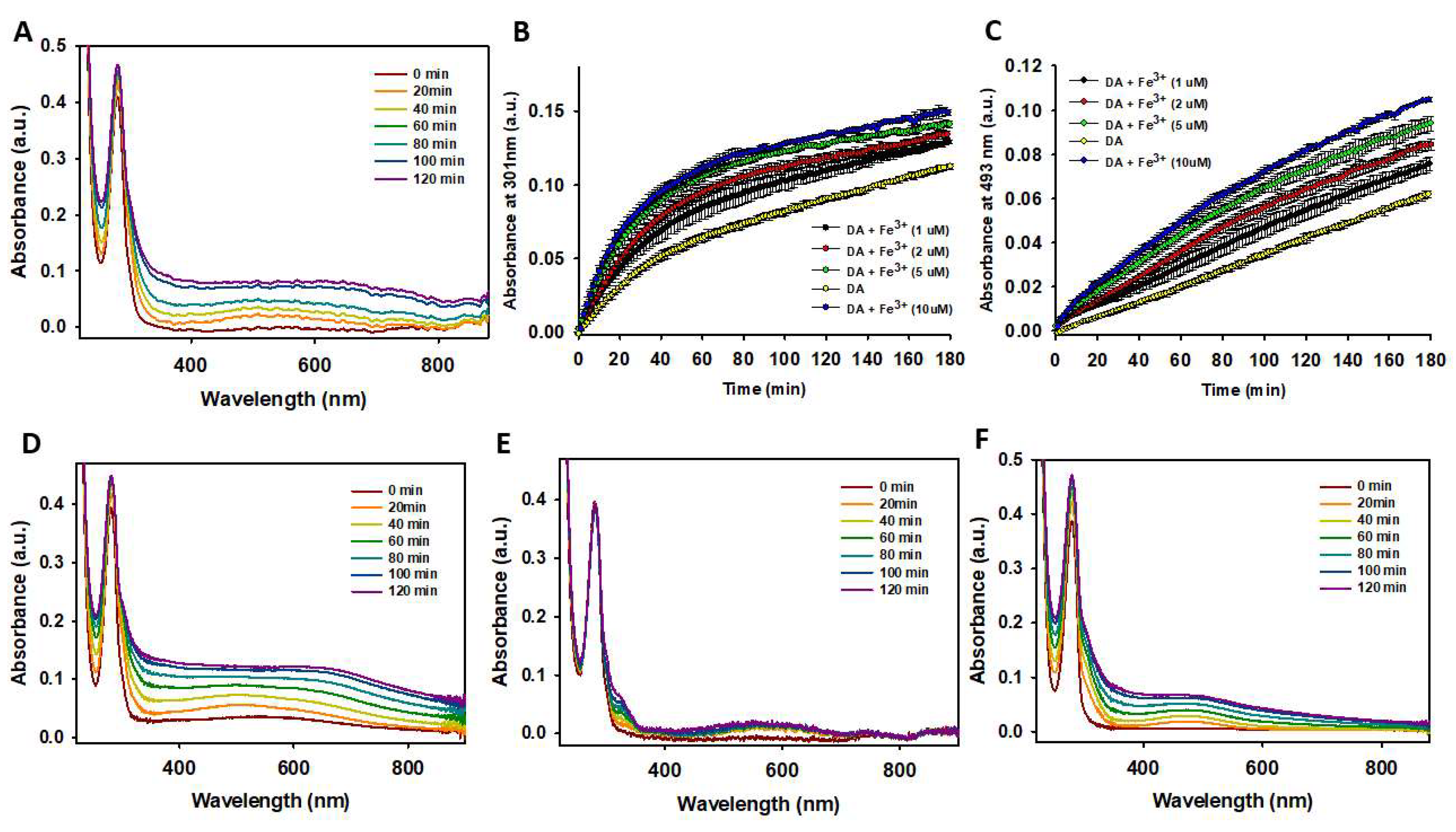

3.1. Understanding the Environmental Factors Affecting the Degradation of DA

3.1.1. The Conversion of AC into NM is Dependent of the Initial Concentration of DA

3.1.2. Phosphate Catalyzes the Formation of NM from of AC

3.1.3. NaCl Slightly Affects the Degradation Rate of DA

3.1.4. On the Effect of Oxidants and Reductants on the Degradation of DA

3.1.5. Fe3+ Enhances the Degradation Rate of DA

3.1.6. On the effect of Ca2+, Zn2+ and Al3+ on the degradation of DA

3.1.7. Effect of pH and Buffer-Type on the Degradation of DA

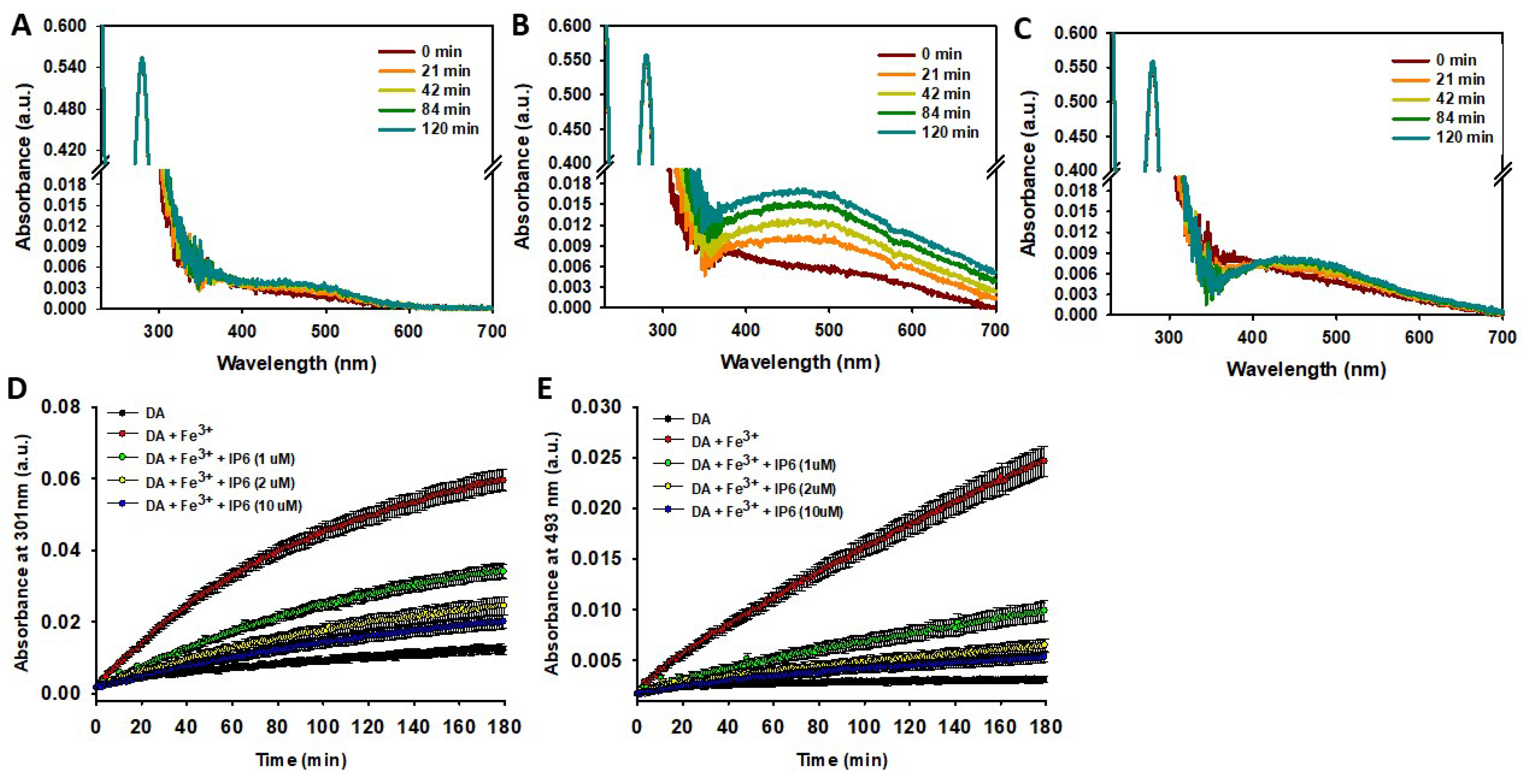

3.2. IP6 Inhibits the Fe3+-Catalyzed Degradation of DA

3.2.1. IP6 Inhibits the Fe3+-Catalyzed Degradation of Free DA

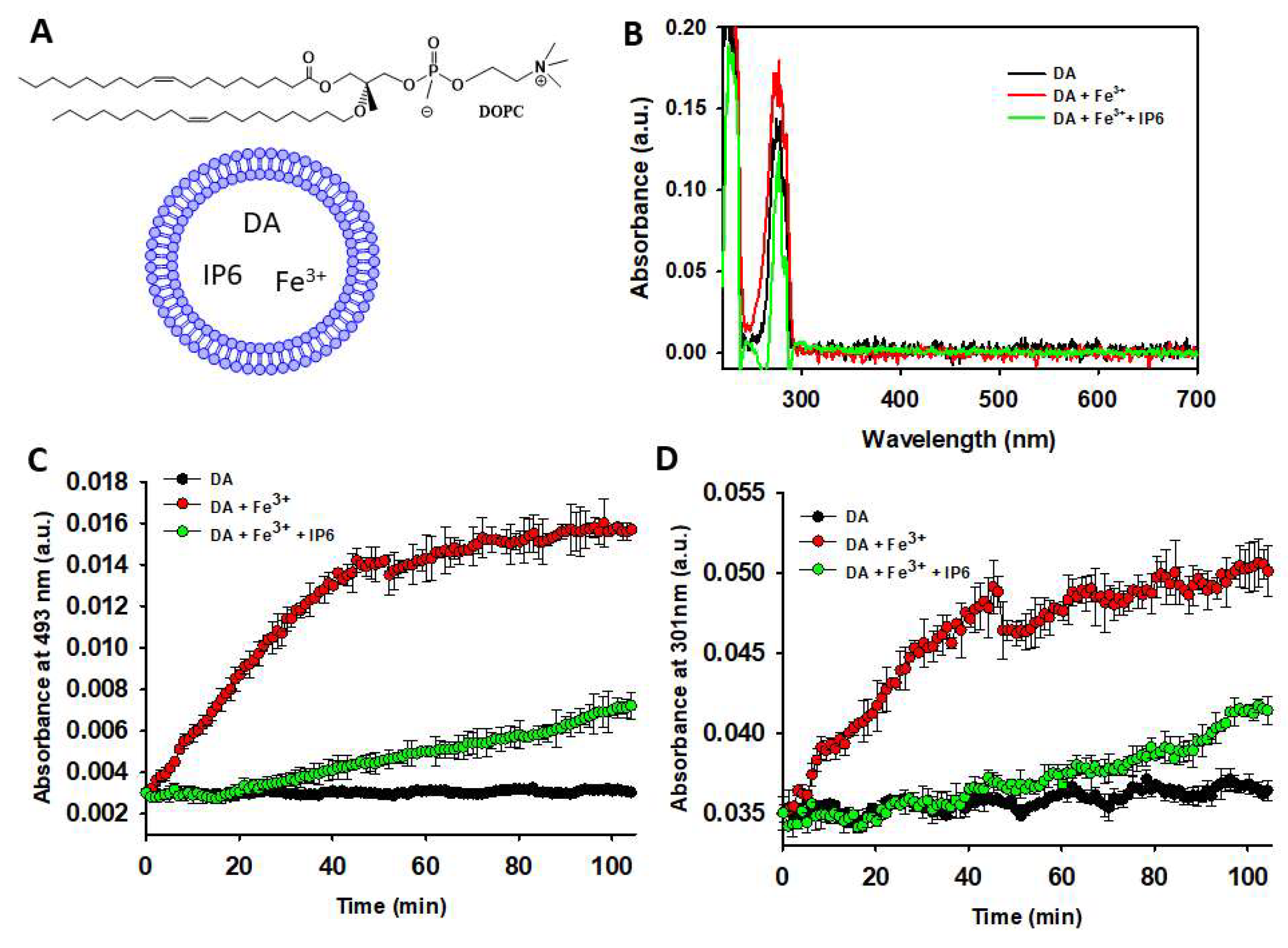

3.2.2. IP6 Inhibits the Fe3+-Catalyzed Degradation of Liposome-Encapsulated DA

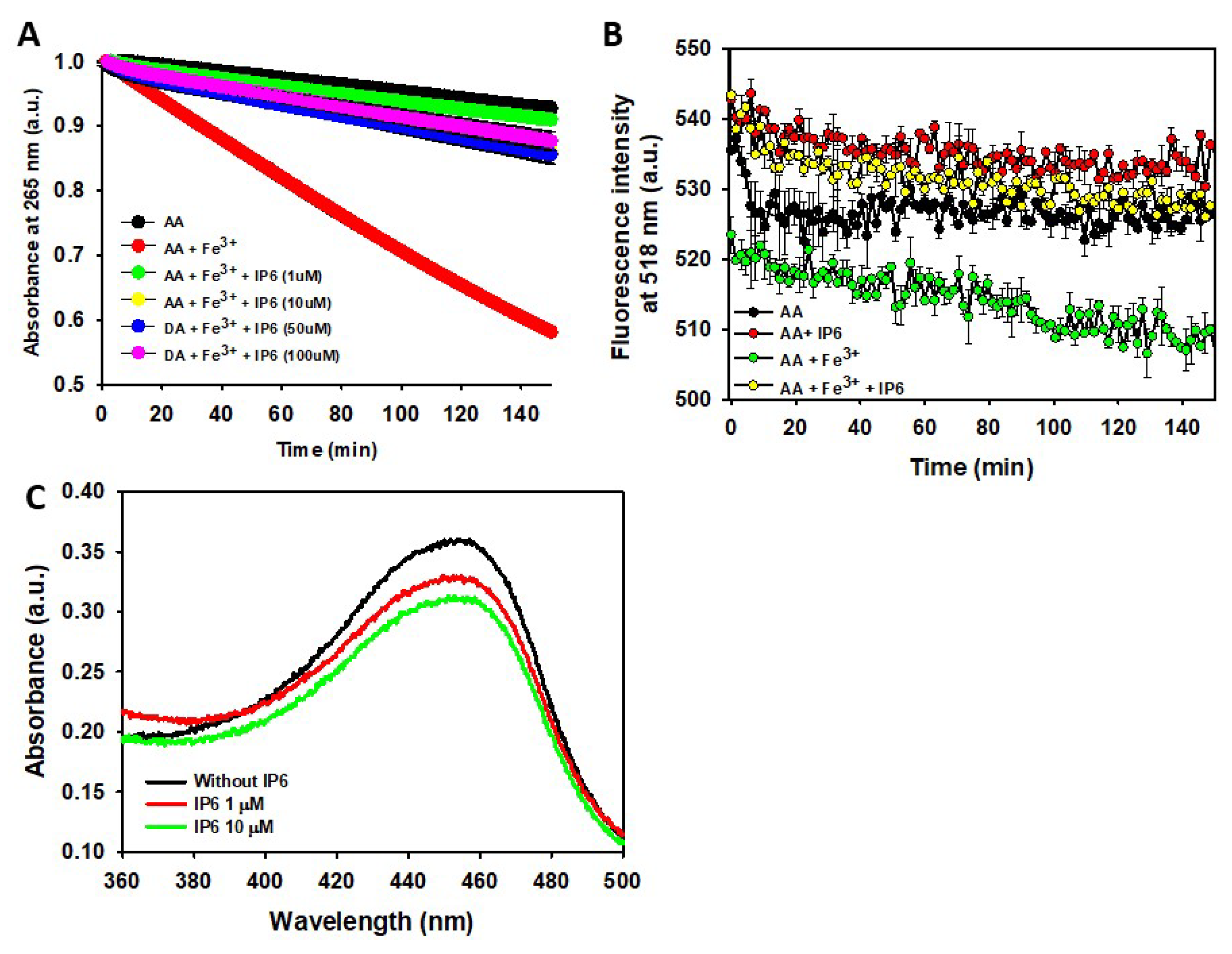

3.3. IP6 Inhibits the Fe3+-Catalyzed Degradation of AA and the Formation of ROS.

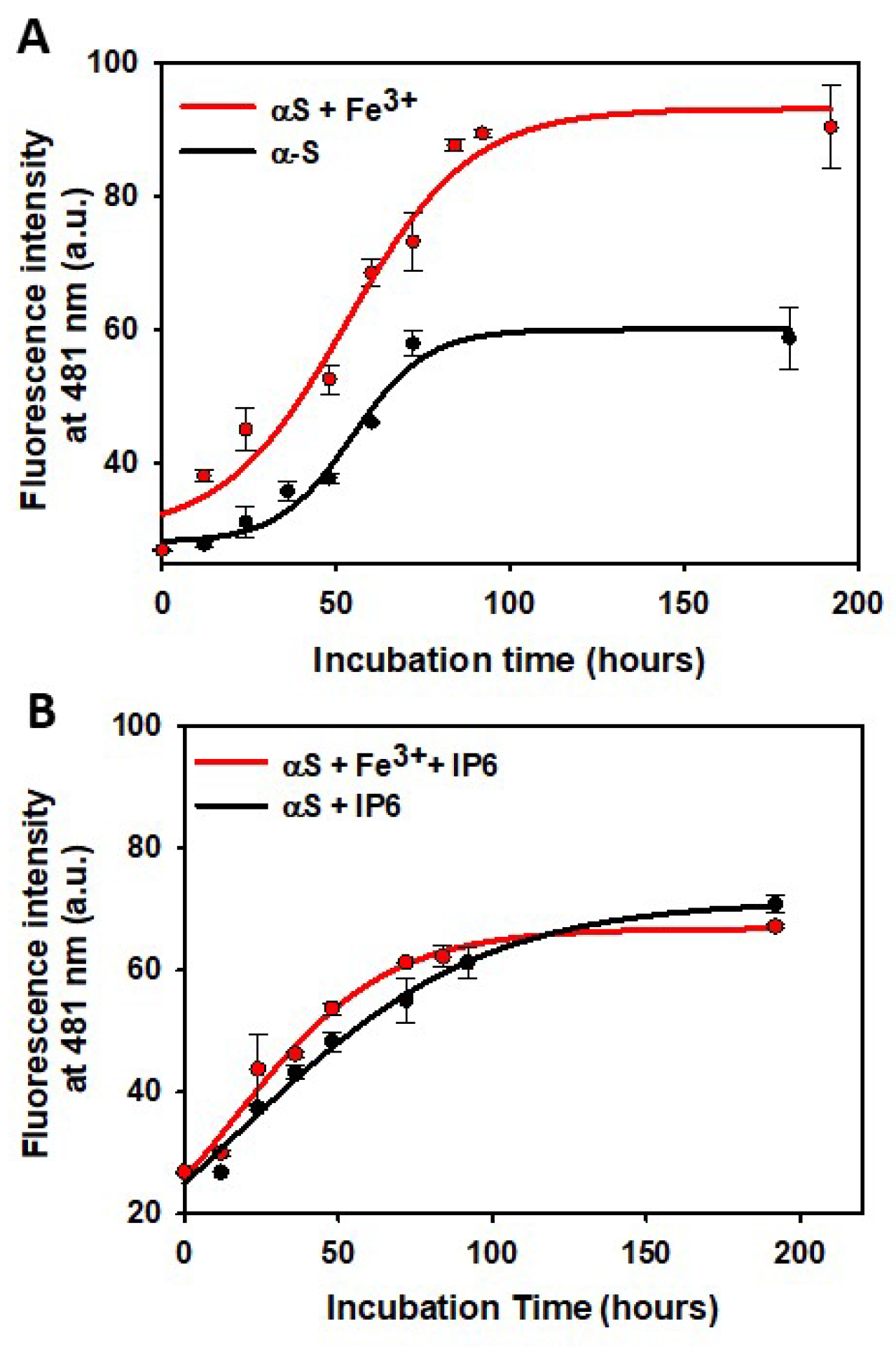

3.4. Effect of IP6 on the Fibrillization of α-Synuclein

4. Discussion

4.1. IP6 is a Protective Agent Against Fe3+-Catalysed Degradation of DA

4.2. Vesicle Encapsulation and the Role of IP6 in DA Stability

4.3. Inhibition of Fe3+-Catalyzed AA Degradation and ROS Formation

4.4. Modulation of α-Synuclein Aggregation by IP6

4.5. Implications for Neurodegeneration Prevention

4.6. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feizollahi, E.; Mirmahdi, R.S.; Zoghi, A.; Zijlstra, R.T.; Roopesh, M.S.; Vasanthan, T. Review of the beneficial and anti-nutritional qualities of phytic acid, and procedures for removing it from food products. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, W.; Xu, Q.; Reddy, M.B. Neuroprotection of phytic acid in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Functional Foods 2023, 110, 105856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.M.; Putti, F.F.; White, P.J.; Reis, A.R.D. Phytic acid accumulation in plants: Biosynthesis pathway regulation and role in human diet. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 164, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlemmer, U.; Frølich, W.; Prieto, R.M.; Grases, F. Phytate in foods and significance for humans: food sources, intake, processing, bioavailability, protective role and analysis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009, 53, S330–S375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, B.; Raigond, P.; Sahu, C.; Mishra, U.N.; Sharma, S.; Lal, M.K. Phytic acid: Blessing in disguise, a prime compound required for both plant and human nutrition. Food Res. Int. 2021, 142, 110193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferry, S.; Matsuda, M.; Yoshida, H.; Hirata, M. Inositol hexakisphosphate blocks tumor cell growth by activating apoptotic machinery as well as by inhibiting the Akt/NFκB-mediated cell survival pathway. Carcinogenesis 2002, 23, 2031–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffucci, T.; Falasca, M. Signalling properties of inositol polyphosphates. Molecules 2020, 25, 5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Aruga, J.; Niinobe, M.; Aimoto, S.; Mikoshiba, K. Inositol-1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate binding to C2B domain of IP4BP/synaptotagmin II. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 29206–29211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidarov, I.; Krupnick, J.G.; Falck, J.R.; Benovic, J.L.; Keen, J.H. Arrestin function in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis requires phosphoinositide binding. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanakahi, L.A.; Bartlet-Jones, M.; Chappell, C.; Pappin, D.; West, S.C. Binding of inositol phosphate to DNA-PK and stimulation of double-strand break repair. Cell 2000, 102, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.D.; Odom, A.R.; Murphy, R.; Ives, E.B.; Wente, S.R. A phospholipase C-dependent inositol polyphosphate kinase pathway required for efficient messenger RNA export. Science 1999, 285, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, S.S.; Cheryan, M. Effects of phytic acid, divalent cations, and their interactions on α-amylase activity. J. Food Sci. 1984, 49, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.S.; Damodaran, S. Effect of phytate on solubility, activity and conformation of trypsin and shymotrypsin. J. Food Sci. 1989, 54, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouns, F. Phytic acid and whole grains for health controversy. Nutrients 2021, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grases, F.; Simonet, B.M.; Prieto, R.M.; March, J.G. Dietary phytate and mineral bioavailability. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2001, 15, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grases, F.; Simonet, B.M.; Perelló, J.; Costa-Bauzá, A.; Prieto, R.M. Effect of phytate on element bioavailability in the second generation of rats. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2004, 17, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grases, F.; Söhnel, O.; Zelenková, M.; Rodriguez, A. Phytate effects on biological hydroxyapatite development. Urolithiasis 2015, 43, 571–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggi, P.; Bellasi, A.; Bushinsky, D.; Bover, J.; Rodriguez, M.; Ketteler, M.; Sinha, S.; Salcedo, C.; Gillotti, K.; Padgett, C.; Garg, R.; Gold, A.; Perelló, J.; Chertow, G.M. Slowing progression of cardiovascular calcification with SNF472 in patients on hemodialysis: results of a randomized phase 2b study. Circulation 2020, 141, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, P.; Buades, J.M.; Berga, F.; Gelabert, M.M.; Molina, M.; Íñigo, M.V.; García, S.; Gonzalez, J.; Bernabeu, M.R.; Costa-Bauzá, A.; Grases, F. Protective effect of myo-inositol hexaphosphate (phytate) on abdominal aortic calcification in patients with chronic kidney disease. J. Ren. Nutr. 2016, 26, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grases, F.; Sanchis, P.; Perelló, J.; Isern, B.; Prieto, R.M.; Fernández-Palomeque, C.; Torres, J.J. Effect of crystallization inhibitors on vascular calcifications induced by vitamin D: a pilot study in Sprague-Dawley rats. Circ. J. 2007, 71, 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.-B.; Lin, M.-E.; Huang, R.-H.; Hong, Y.-K.; Lin, B.-L.; He, X.-J. Dietary and lifestyle factors for primary prevention of nephrolithiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, O.H.; Booth, C.J.; Choi, H.S.; Lee, J.; Kang, J.; Hur, J.; Jung, W.J.; Jung, Y.S.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, H.; Auh, J.H.; Kim, J.W.; Cha, J.Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, C.S.; Choi, C.; Jung, Y.J.; Yang, J.Y.; Im, S.S.; Lee, D.H.; Cho, S.W.; Kim, Y.B.; Park, K.S.; Park, Y.J.; Oh, B.C. High-phytate/low-calcium diet is a risk factor for crystal nephropathies, renal phosphate wasting, and bone loss. Elife 2020, 9, e52709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grases, F.; Perelló, J.; Sanchis, P.; Isern, B.; Prieto, R.M.; Costa-Bauzá, A.; Santiago, C.; Ferragut, M.L.; Frontera, G. Anticalculus effect of a triclosan mouthwash containing phytate: a double-blind, randomized, three-period crossover trial. J. Periodontal Res. 2009, 44, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchis, P.; López-González, Á.A.; Costa-Bauzá, A.; Busquets-Cortés, C.; Riutord, P.; Calvo, P.; Grases, F. Understanding the protective effect of phytate in bone decalcification related-diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grases, F.; Sanchis, P.; Prieto, R.M.; Perelló, J.; López-González, Á.A. Effect of tetracalcium dimagnesium phytate on bone characteristics in ovariectomized rats. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimerà, J.; Martínez, A.; Bauza, J.L.; Sanchís, P.; Pieras, E.; Grases, F. Effect of phytate on hypercalciuria secondary to bone resorption in patients with urinary stones: pilot study. Urolithiasis 2022, 50, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilworth, L.L.; Omoruyi, F.O.; Simon, O.R.; Morrison, E.Y.; Asemota, H.N. The effect of phytic acid on the levels of blood glucose and some enzymes of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. West Indian Med. J. 2005, 54, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoruyi, F.O.; Budiaman, A.; Eng, Y.; Olumese, F.E.; Hoesel, J.L.; Ejilemele, A.; Okorodudu, A.O. The potential benefits and adverse effects of phytic acid supplement in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 2013, 172494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoruyi, F.O.; Stennett, D.; Foster, S.; Dilworth, L. New frontiers for the use of IP6 and inositol combination in treating diabetes mellitus: a review. Molecules 2020, 25, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, P.; Hosseini, S.; Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Azizi, F. Legume consumption increases adiponectin concentrations among type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized crossover clinical trial. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. (Engl. Ed.) 2019, 66, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge, M.J.; Irvine, R.F. Inositol trisphosphate, a novel second messenger in cellular signal transduction. Nature 1984, 312, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onomi, S.; Okazaki, Y.; Katayama, T. Effect of dietary level of phytic acid on hepatic and serum lipid status in rats fed a high-sucrose diet. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004, 68, 1379–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, P.; Rivera, R.; Berga, F.; Fortuny, R.; Adrover, M.; Costa-Bauzá, A.; Grases, F.; Masmiquel, L. Phytate decreases formation of advanced glycation end-products in patients with type II diabetes: randomized crossover trial. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn, B.J.; Mann, J.I. Cereal grains, legumes and diabetes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 1443–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Peláez, S.; Fito, M.; Castaner, O. Mediterranean diet effects on type 2 diabetes prevention, disease progression, and related mechanisms: a review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucenik, I.; Shamsuddin, A.M. Protection against cancer by dietary IP6 and inositol. Nutr. Cancer 2006, 55, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiśniewski, K.; Jozwik, M.; Wojtkiewicz, J. Cancer prevention by natural products introduced into the diet—selected cyclitols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wattenberg, L. Chalcones, myo-inositol and other novel inhibitors of pulmonary carcinogenesis. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl. 1995, 22, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacić, I.; Druzijanić, N.; Karlo, R.; Skifić, I.; Jagić, S. Efficacy of IP6 + inositol in the treatment of breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: prospective, randomized, pilot clinical study. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 29, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, R.; Nassar, M.; Vianna, M.E.; Naidoo, N.; Alqutami, F.; Kaklamanos, E.G.; Senok, A.; Williams, D. Antimicrobial activity of phytic acid: an emerging agent in endodontics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 753649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otake, T.; Shimonaka, H.; Kanai, M.; Miyano, K.; Ueba, N.; Kunita, N.; Kurimura, T. Inhibitory effect of inositol hexasulfate and inositol hexaphosphoric acid (phytic acid) on the proliferation of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in vitro. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 1989, 63, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grases, F.; Simonet, B.M.; Prieto, R.M.; March, J.G. Variation of InsP4, InsP5 and InsP6 levels in tissues and biological fluids depending on dietary phytate. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2001, 12, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grases, F.; Simonet, B.M.; Prieto, R.M.; March, J.G. Phytate levels in diverse rat tissues: influence of dietary phytate. Br. J. Nutr. 2001, 86, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.N.; Yu, J.; Mayr, G.W.; Hofmann, F.; Larsson, O.; Berggren, P.O. Inositol hexakisphosphate increases L-type Ca2+ channel activity by stimulation of adenylyl cyclase. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 1753–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidarov, I.; Chen, Q.; Falck, J.R.; Reddy, K.K.; Keen, J.H. A functional phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate/phosphoinositide binding domain in the clathrin adaptor AP-2 alpha subunit. Implications for the endocytic pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 20922–20929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llinàs, R.; Sugimori, M.; Lang, E.J.; Morita, M.; Fukuda, M.; Niinobe, M.; Mikoshiba, K. The inositol high-polyphosphate series blocks synaptic transmission by preventing vesicular fusion: a squid giant synapse study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994, 91, 12990–12993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Ikenaka, K.; Niinobe, M.; Yamada, H.; Mikoshiba, K. Myelin proteolipid protein (PLP), but not DM-20, is an inositol hexakisphosphate-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 27838–27846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, J.M.; Plomann, M.; Ritter, B.; Modregger, J.; Freeman, H.N.; Falck, J.R.; Krishna, U.M.; Tobin, A.B. Phosphorylation of a synaptic vesicle-associated protein by an inositol hexakisphosphate-regulated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 16341–16347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larvie, D.Y.; Armah, S.M. Estimated phytate intake is associated with improved cognitive function in the elderly, NHANES 2013–2014. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, L.; Wang, Y.; Fakuda, K.; Leurgans, S.; Aggarwal, N.; Morris, M. Mediterranean-Dash intervention for neurodegenerative delay (MIND) diet slows cognitive decline after stroke. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 6, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, B.; Caulfield, L.; Richard, S.; Pendergast, L.; Murray-Kolb, L.; Mald-Ed Network investigators. Nurturing environments and nutrient-rich diets may improve cognitive development: analysis of cognitive trajectories from six to sixty months from the MAL-ED study. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz034.OR10-01-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Kanthasamy, A.G.; Reddy, M.B. Neuroprotective effect of the natural iron chelator, phytic acid in a cell culture model of Parkinson’s disease. Toxicology 2008, 245, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Kanthasamy, A.G.; Reddy, M.B. Phytic acid protects against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced dopaminergic neuron apoptosis in normal and iron excess conditions in a cell culture model. Parkinsons Dis. 2011, 2011, 431068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Hou, L.; Li, X.; Ju, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Lv, Y.; Wang, Y. Neuroprotection of inositol hexaphosphate and changes of mitochondrion mediated apoptotic pathway and α-synuclein aggregation in 6-OHDA induced Parkinson’s disease cell model. Brain Res. 2016, 1633, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.K.; Taniguchi, M. Identification of myo-inositol hexakisphosphate (IP6) as a β-secretase 1 (BACE1) inhibitory molecule in rice grain extract and digest. FEBS Open Bio. 2014, 4, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Jung, Y.S.; Jung, Y.J.; Kim, O.H.; Oh, B.C. High-phytate diets increase amyloid β deposition and apoptotic neuronal cell death in a rat model. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marolt, G.; Sala, M.; Pihlar, B. Voltammetric investigation of iron (III) interactions with phytate. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 176, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crea, F.; De Stefano, C.; Milea, D.; Sammartano, S. Formation and stability of phytate complexes in solution. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 1108–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusek, P.; Hofer, T.; Alexander, J.; Roos, P.M.; Aaseth, J.O. Cerebral iron deposition in neurodegeneration. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakaria, M.; Belaidi, A.A.; Bush, A.I.; Ayton, S. Ferroptosis as a mechanism of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2021, 159, 804–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney-Sánchez, L.; Bouchaoui, H.; Ayton, S.; Devos, D.; Duce, J.A.; Devedjian, J.C. Ferroptosis and its potential role in the physiopathology of Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2021, 196, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedges, D.M.; Yorgason, J.T.; Perez, A.W.; Schilaty, N.D.; Williams, B.M.; Watt, R.K.; Steffensen, S.C. Spontaneous formation of melanin from dopamine in the presence of iron. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.M.; Martell, A.E. Metal ion and metal chelate catalyzed oxidation of ascorbic acid by molecular oxygen. II. Cupric and ferric chelate catalyzed oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 7104–7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Olguín, H.; Calderón-Guzmán, D.; Hernández-García, E.; Barragán-Mejía, G. The role of dopamine and its dysfunction as a consequence of oxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 9730467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covarrubias-Pinto, A.; Acuña, A.I.; Beltrán, F.A.; Torres-Díaz, L.; Castro, M.A. Old things new view: ascorbic acid protects the brain in neurodegenerative disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 28194–28217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, M.; Fraga, D.B.; Rodrigues, A.L.S. Preventive and therapeutic potential of ascorbic acid in neurodegenerative diseases. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017, 23, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Pham, A.N.; Hare, D.J.; Waite, T.D. Kinetic modeling of pH-dependent oxidation of dopamine by iron and its relevance to Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Il’ichev, Y.V.; Simon, J.D. Building blocks of eumelanin: relative stability and excitation energies of tautomers of 5, 6-dihydroxyindole and 5, 6-indolequinone. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 7162–7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, S.; Lakshmi, K.V.; Reddy, V. Trial of ferrous glycine sulphate in the fortification of common salt with iron. Food Chem. 1996, 57, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, B.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Flanagan, J.; Deemer, E.K.; Prior, R.L.; Huang, D. Novel fluorometric assay for hydroxyl radical prevention capacity using fluorescein as the probe. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 2772–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyürek, M.; Bektaşoğlu, B.; Güçlü, K.; Apak, R. Hydroxyl radical scavenging assay of phenolics and flavonoids with a modified cupric reducing antioxidant capacity (CUPRAC) method using catalase for hydrogen peroxide degradation. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 616, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uceda, A.B.; Donoso, J.; Frau, J.; Vilanova, B.; Adrover, M. Frataxins emerge as new players of the intracellular antioxidant machinery. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uceda, A.B.; Frau, J.; Vilanova, B.; Adrover, M. Glycation of α-synuclein hampers its binding to synaptic-like vesicles and its driving effect on their fusion. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uceda, A.B.; Frau, J.; Vilanova, B.; Adrover, M. Tyrosine nitroxidation does not affect the ability of α-synuclein to bind anionic micelles, but it diminishes its ability to bind and assemble synaptic-like vesicles. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariño, L.; Ramis, R.; Casasnovas, R.; Ortega-Castro, J.; Vilanova, B.; Frau, J.; Adrover, M. Unravelling the effect of N(ε)-(carboxyethyl)lysine on the conformation, dynamics and aggregation propensity of α-synuclein. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 3332–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariño, L.; Uceda, A.B.; Leal, F.; Adrover, M. Insight into the effect of methylglyoxal on the conformation, function, and aggregation propensity of α-synuclein. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202400890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancalana, M.; Koide, S. Molecular mechanism of Thioflavin-T binding to amyloid fibrils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, J.; Bi, S. Aluminum facilitation of the iron-mediated oxidation of DOPA to melanin. Anal. Sci. 2004, 20, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.F. The solubility of nitrogen, oxygen and argon in water and seawater. Deep-Sea Res. Oceanogr. Abstr. 1970, 17, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hider, R.C.; Howlin, B.J.; Miller, J.R.; Mohd-Nor, A.; Silver, J. Model compounds for microbial iron-transport compounds. Part IV. Further solution chemistry and Mössbauer studies on iron(II) and iron(III) catechol complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1983, 80, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.; Mañez, P.A.; Cabrera, G.M.; Maître, P. Gas phase structure and reactivity of doubly charged microhydrated calcium(II)–catechol complexes probed by infrared spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 4942–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, J.; Bi, S. Aluminum facilitation of the iron-mediated oxidation of DOPA to melanin. Anal. Sci. 2004, 20, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, H.S.; Chiang, H.C.; Lin, A.M.; Chiang, H.Y.; Chu, Y.C.; Kao, L.S. Synergistic effects of dopamine and Zn2+ on the induction of PC12 cell death and dopamine depletion in the striatum: possible implication in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2004, 17, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Uchiyama, K.; Ohsawa, K.; Imaeda, K. Effects of buffer solutions and chelators on the generation of hydroxyl radical and the lipid peroxidation in the Fenton reaction system. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 1992, 13, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minotti, G.; Aust, S.D. The role of iron in the initiation of lipid peroxidation. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1987, 44, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadolini, B. Iron autoxidation in Mops and Hepes buffers. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 1987, 4, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, M.D.S.; Gamiz-Arco, G.; Martinez, A. Dopamine synthesis and transport: current and novel therapeutics for parkinsonisms. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2024, 52, 1275–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, S.M.; Gaskill, P.J. Where is dopamine and how do immune cells see it?: dopamine-mediated immune cell function in health and disease. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020, 15, 114–164. [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano, A.; Pezzella, A.; Prota, G. New reaction pathways of dopamine under oxidative stress conditions: nonenzymatic iron-assisted conversion to norepinephrine and the neurotoxins 6-hydroxydopamine and 6,7-dihydroxytetrahydroisoquinoline. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1999, 12, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, I.; Martinez-Alvarado, P.; Perez-Pastene, C.; Vieira, M.N.; Olea-Azar, C.; Raisman-Vozari, R.; Cardenas, S.; Graumann, R.; Caviedes, P.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Monoamine transporter inhibitors and norepinephrine reduce dopamine-dependent iron toxicity in cells derived from the substantia nigra. J. Neurochem. 2005, 92, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofic, E.; Riederer, P.; Heinsen, H.; Beckmann, H.; Reynolds, G.P.; Hebenstreit, G.; Youdim, M.B. Increased iron (III) and total iron content in post mortem substantia nigra of parkinsonian brain. J. Neural Transm. 1988, 74, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista-Nascimento, L.; Pimentel, C.; Menezes, R.A.; Rodrigues-Pousada, C. Iron and neurodegeneration: from cellular homeostasis to disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 128647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohorovic, L.; Lavezzi, A.; Stifter, S.; Perry, G.; Malatestinic, D.; Micovic, V.; Materljan, E. Ferric iron brain deposition as the cause, source and originator of chronic neurodegenerative diseases. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2015, 2, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, S.K.; Novak, J.E.; Agranoff, B.W. Inositol and higher inositol phosphates in neural tissues: homeostasis, metabolism and functional significance. J. Neurochem. 2002, 82, 736–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabb, J.S.; Kish, P.E.; Van Dyke, R.; Ueda, T. Glutamate transport into synaptic vesicles: roles of membrane potential, pH gradient, and intravesicular pH. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 15412–15418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretti, C.; Cigala, R.M.; Lando, G.; Milea, D.; Sammartano, S. Sequestering ability of phytate toward biologically and environmentally relevant trivalent metal cations. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 8075–8082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritacca, A.G.; Malacaria, L.; Sicilia, E.; Furia, E.; Mazzone, G. Experimental and theoretical study of the complexation of Fe3+ and Cu2+ by L-ascorbic acid in aqueous solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 355, 118973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshnikov, V.A.; Kobzeva, T.V.; Polyakov, N.E.; Kontoghiorghes, G.J. Redox interactions of vitamin C and iron: inhibition of the pro-oxidant activity by deferiprone. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, S. Oxidation of ascorbic acid and metal ions as affected by NaCl. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1994, 42, 2402–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Panda, D. Contrasting effects of ferric and ferrous ions on oligomerization and droplet formation of tau: implications in tauopathies and neurodegeneration. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 4393–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizaki, T. Fe3+ facilitates endocytic internalization of extracellular Aβ1–42 and enhances Aβ1–42-induced caspase-3/caspase-4 activation and neuronal cell death. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 4812–4819. [Google Scholar]

- Joppe, K.; Roser, A.E.; Maass, F.; Lingor, P. The contribution of iron to protein aggregation disorders in the central nervous system. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straumann, N. Iron deposition and α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2024, 34, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arosio, P.; Knowles, T.P.; Linse, S. On the lag phase in amyloid fibril formation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 7606–7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salahuddin, P.; Fatima, M.T.; Abdelhameed, A.S.; Nusrat, S.; Khan, R.H. Structure of amyloid oligomers and their mechanisms of toxicities: targeting amyloid oligomers using novel therapeutic approaches. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 114, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayed, R.; Head, E.; Thompson, J.L.; McIntire, T.M.; Milton, S.C.; Cotman, C.W.; Glabe, C.G. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science 2003, 300, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, D.; Double, K. Iron and dopamine metabolism in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).