1. Introduction

Recent advances in hardware and artificial intelligence systems have paved the way for the practical implementation of edge computing. One crucial application of this technology is the ability to track targets using multiple cameras, which holds significant potential for a wide range of smart city applications. This type of system can play a vital role in various scenarios, such as tracking criminals, efficiently managing traffic for emergency vehicles, and monitoring targets during military operations in smart cities.

Despite the significant potential of multi-camera target tracking, most existing works in this domain focus on centralized processing or require extensive computational resources, making them unsuitable for real-time, resource-constrained applications. These systems often rely on transmitting raw or partially processed data to centralized servers, which introduces latency and poses challenges in scalability and data privacy. While advancements in multi-camera systems have shown promise in areas like trajectory prediction and camera selection, very few studies have explored target tracking implemented directly on edge devices. On-device edge AI offers the advantage of localized processing, enabling low-latency responses and enhanced data privacy by minimizing data transmission. However, research in this area remains limited, particularly in designing frameworks that can operate efficiently across distributed cameras. This gap underscores the need for scalable, energy-efficient, and practical solutions tailored for edge AI systems, which is the focus of our work.

To address this gap, we propose the TEDDY framework, which stands for "An Efficient Framework for Target Tracking Using Edge-Based Distributed Smart Cameras with Dynamic Camera Selection," an innovative and efficient solution for target tracking that leverages edge-based distributed smart cameras with context-aware dynamic camera selection. This framework is specifically designed to operate on resource-constrained edge devices, using lightweight tracking algorithms to ensure fast, energy-efficient, and real-time performance. By focusing on localized processing and dynamic camera activation, the TEDDY framework minimizes redundant computations and optimizes resource utilization. Furthermore, it is tailored for deployment on low-cost devices, allowing seamless integration with existing surveillance infrastructure. This eliminates the need for additional hardware or system overhauls, making the framework a cost-effective and practical solution for real-world applications, particularly in smart city environments.

Although previous works have explored dynamic approaches to target tracking, they have largely focused on specific applications rather than on establishing a flexible and generalizable framework. In contrast, the TEDDY framework emphasizes adaptability, scalability, and efficient use of resources to support a wide range of tracking scenarios. The proposed framework makes the implementation more cost-effective and less disruptive by leveraging existing surveillance infrastructure, eliminating the need for additional cameras or entirely new systems. Additionally, the TEDDY framework processes and analyzes data locally at the edge, significantly reducing latency and enhancing responsiveness. This capability is particularly valuable in situations requiring rapid decision-making, such as emergency responses or dynamic urban environments. Local processing also improves data privacy and security by keeping sensitive information closer to its source, minimizing the risks associated with transmission over networks.

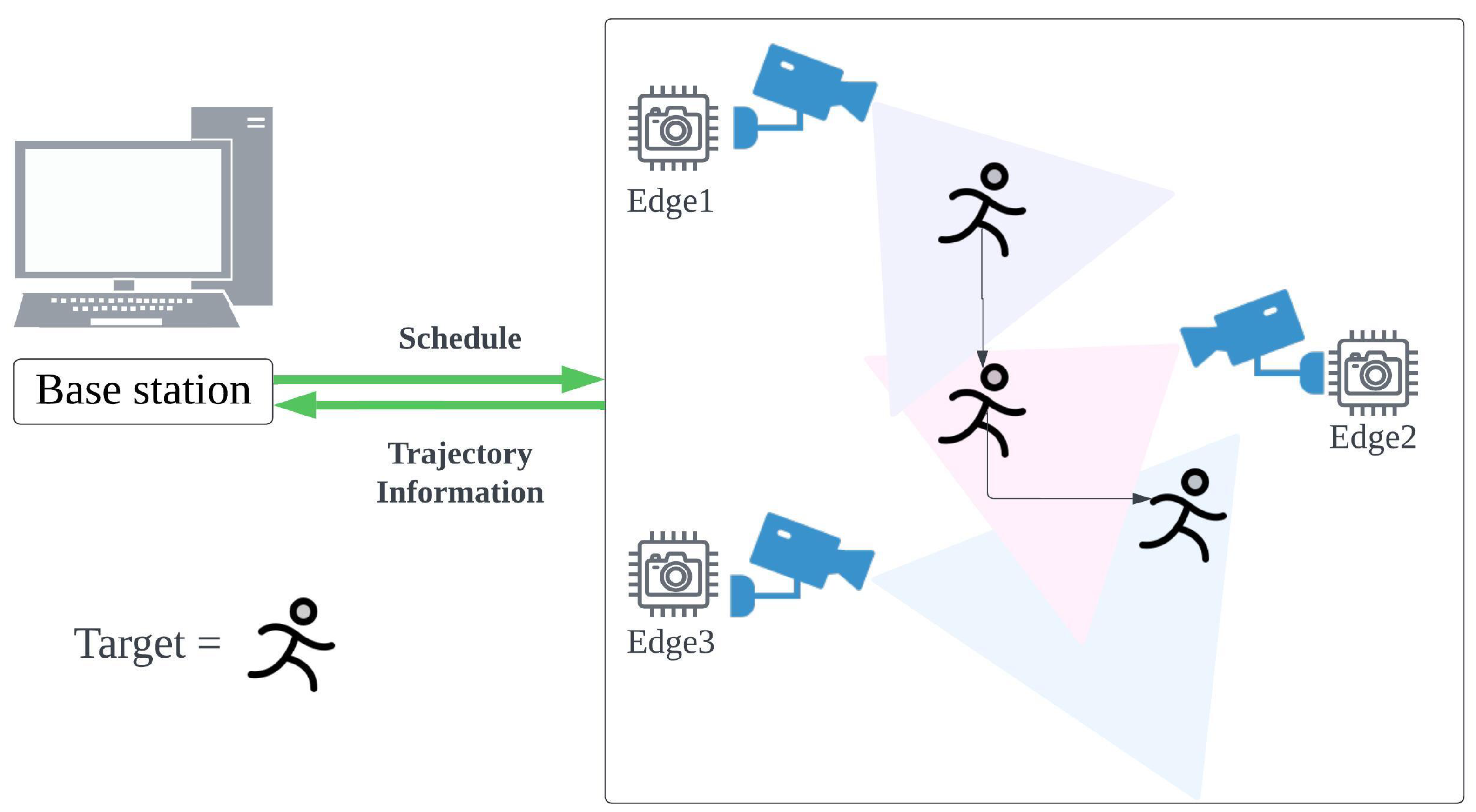

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the TEDDY framework operates through a network of distributed edge devices, each equipped with cameras or other sensors, strategically placed in the area where the target is expected to be. The central component of the system is the

, which manages and coordinates the overall schedule of these edge devices.

In

Figure 1, the target is depicted as a person, and the system is shown with three edges. However, it is important to note that both the target and the number of edges are flexible and can vary depending on the scenario.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the TEDDY framework, we present two practical applications that validate its utility. First, we conduct an experiment with a single person tracking system. For our first experiment, we designed a dataset simulating a scenario in which the system tracks a specific target—a person following various routes at different speeds. We compared our system, which employs dynamic camera selection, to a system without this feature. Our results demonstrate that our system achieves approximately over 20% better performance in terms of computational complexity and energy efficiency when applied to embedded boards. In the second experiment, we simulated a smart city scenario to test our method in a dynamic traffic light adjustment system as a extended scenario of the first experiments. Specifically, we modeled a city where traffic lights can adjust in real-time when an emergency vehicle is detected, allowing it to reach its destination as quickly as possible. From this experiment, our framework allow to achieve around 90% lower computations with the same accuracy.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 summarizes related work in the field of general camera tracking, camera selection, and on-device tracking.

Section 3 details the proposed TEDDY framework.

Section 4 presents our experimental setup, two distinct test scenarios, and the corresponding results.

Section 5 provides an in-depth discussion of the findings and addresses potential limitations of the framework. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses avenues for future research.

2. Related Works

2.1. Camera Tracking

Single-camera tracking serves as the basis for more advanced tracking methods currently under investigation. It involves consistently identifying a moving target within the field of view of a single camera in consecutive frames. One of the pioneering works in this area is SORT [

1], which leverages the fact that object movement between consecutive frames is typically small. It uses a Kalman filter [

2] to predict the spatial locations of tracklets and employs the Hungarian algorithm to associate these predictions with the current frame’s detections. Building on the SORT algorithm, DeepSORT [

3] enhances the tracking by using a CNN model for Re-Identification(ReID) to extract and match appearance features. Subsequent research has continued to advance the use of appearance features [

4,

5,

6]. Additionally, some approaches have framed data association as a graph optimization problem [

7,

8,

9]. Multi-camera tracking (MCT) is a crucial area of research focused on monitoring targets across multiple camera views [

10]. In contrast to single-camera tracking, which primarily aims to maintain the identity of a target within the field of view of a single camera, MCT poses additional challenges. These include managing varying camera viewpoints, addressing occlusions, synchronizing multiple camera feeds, and associating targets across non-overlapping camera views. Due to these varying viewpoints, complex ReID models are required to maintain target identity across different camera views, and the spatial relationships between multiple cameras must be carefully defined. Most of the recent research in multi-camera target tracking employs a two-step framework. First, Single-Camera Tracking (SCT) is performed, followed by Inter-Camera Tracking (ICT) using the information gathered from SCT. To perform ICT, approaches typically estimate entry-exit points between cameras [

11,

12] and predict the future trajectory of the target [

13,

14]. Additionally, ReID methods are used to re-identify the target across different cameras [

15,

16,

17]. Graph-based approaches are also widely used to perform ICT [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Other common methods include leveraging spatiotemporal contextual information [

12] and clique-based approaches [

24,

25].

2.2. Camera Selection in Tracking

Camera selection is a crucial aspect of multi-camera tracking systems. Processing data from all cameras in a large-scale camera network simultaneously can lead to inefficient computation. The goal of camera selection is to optimize resource utilization and tracking performance by selecting the camera where the target is most likely to appear next. Camera selection decisions can be addressed through various reinforcement learning methods. [

26] employs a traditional Q-learning algorithm to effectively solve the cross-camera handover problem and learn a selection policy. In [

27], deep Q-learning combined with n-step bootstrapping is used to optimize the scheduling of re-identification queries in a multi-camera network. Additionally, [

28] improves camera selection performance by leveraging state representation learning and adopts a semi-supervised learning approach to train the policy. These methods refine camera selection decisions and improve tracking efficiency. Sequential characteristics can also be considered in tracking and camera selection. To handle these time-series characteristics, [

13] utilizes deep learning models specialized for time-series data, such as LSTM and GRU, for predicting the next camera. The study also explored methods like shortest distance, transition frequency, trajectory similarity with the training set, and handcrafted features [

13] for next-camera prediction.

2.3. On-Device Tracking

On-device tracking has gained significant attention as an efficient approach for real-time object tracking. Running tracking systems on a device is particularly valuable in environments where computational resources are limited, such as edge-based camera networks. Various strategies have been developed to reduce the computational overhead of on-device tracking from a single camera. Context-aware skipping techniques dynamically skip certain video frames, lowering computation costs while maintaining tracking precision [

29]. In addition, input slicing and output stitching methods partition high-resolution images for parallel processing and recombine them, significantly decreasing detection latency and enhancing tracking efficiency [

30].

Compared to the aforementioned works, our approach offers significant advancements in both camera selection and on-device tracking. Prior studies on camera selection often rely on reinforcement learning, which requires extensive training and is not optimized for on-device implementation, limiting its practicality in resource-constrained environments. In contrast, our framework eliminates the need for complex training processes, employing a simple yet effective method tailored specifically for on-device operation. Furthermore, while previous on-device tracking efforts have primarily focused on single-camera setups, very few have addressed the challenges of tracking across distributed cameras. Our framework bridges this gap by enabling seamless and energy-efficient tracking in distributed camera systems, providing a scalable and practical solution for real-world applications, particularly in resource-limited environments. This combination of simplicity, scalability, and on-device optimization highlights the unique novelty of our approach.

3. Proposed Method

The TEDDY framework introduces a novel, energy-efficient, and scalable approach to multi-camera target tracking by leveraging dynamic scheduling and on-device processing. Unlike traditional systems that rely on continuous operation of all cameras or complex reinforcement learning-based scheduling, the TEDDY framework dynamically activates and deactivates distributed edge devices based on the predicted trajectory of the target. This section details the architectural components, iterative scheduling mechanism, data flow, and the framework’s expandability, providing a comprehensive understanding of its design and functionality.

3.1. System Architecture

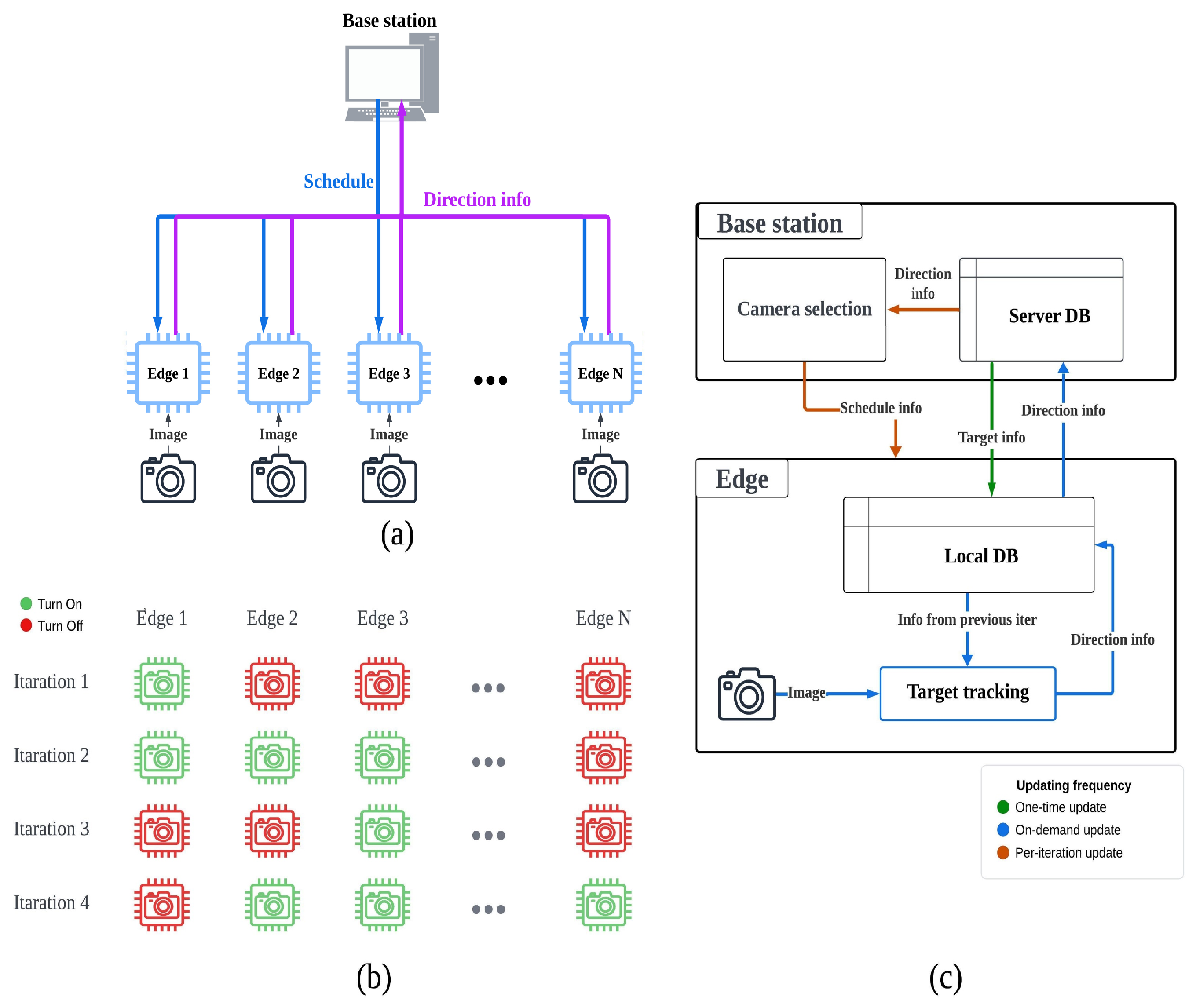

The TEDDY framework consists of two primary components: the base station and the distributed edge devices, as illustrated in

Figure 2a. The base station serves as the central control unit, responsible for scheduling, coordination, and maintaining global tracking consistency. Edge devices are distributed across the system and perform localized target tracking using lightweight processing algorithms. The system operates in iterative cycles, with the base station and the edge devices collaborating to optimize tracking performance and resource efficiency.

At the beginning of each iteration, the base station evaluates the target’s predicted position and trajectory. Based on this evaluation, it determines which edge devices should be activated or deactivated during the upcoming cycle. The base station sends scheduling information to the selected edge devices and receives target position updates after each iteration. This division of labor ensures that computationally intensive tasks, such as trajectory prediction and scheduling, are handled by the base station, while edge devices focus on localized, lightweight processing of image data. Edge devices are equipped with cameras and local databases that store the necessary tracking information for the current iteration. Unlike traditional systems that continuously upload raw data to a centralized server, the TEDDY framework processes data locally at the edge. This approach reduces bandwidth usage, reduces energy consumption, and enhances data privacy by minimizing the transmission of sensitive data.

3.2. Dynamic Scheduling

The dynamic scheduling mechanism is the core innovation of the TEDDY framework, as shown in

Figure 2b. Traditional camera networks often operate with all cameras active, resulting in unnecessary energy consumption and redundant processing. In contrast, the TEDDY framework optimizes resource utilization by activating only the edge devices that are relevant to the target’s current and predicted movement.

Before the system begins, the base station sends the target information, such as the reference image of the target, to the local database on each edge. At the start of each iteration, the base station evaluates the target’s position, trajectory, and surrounding environmental factors. This evaluation determines which cameras are likely to capture the target’s movement in the next iteration. The base station then generates a schedule that indicates which edge devices should remain active and which can be temporarily deactivated. This schedule is communicated to the edge devices before the iteration begins. The iterative scheduling process enables the system to adapt to dynamic scenarios, such as targets with unpredictable movement patterns or changing environmental conditions. By deactivating unnecessary edge devices, the framework minimizes energy consumption while maintaining tracking accuracy. This iterative design also allows the TEDDY framework to scale efficiently, as additional edge devices can be integrated into the network without overwhelming the system.

3.3. Dataflow and Communication

The dataflow and communication between the base station and edge devices, as illustrated in

Figure 2c, are designed to balance efficiency, accuracy, and scalability. The base station plays a central role in the system, predicting the target’s trajectory based on previous position data and movement patterns, generating optimal schedules for activating and deactivating edge devices, and maintaining a centralized server database that stores information such as the target’s position, movement direction, and scheduling updates. On the other hand, edge devices perform localized processing of image data to detect the target and analyze its movement direction, thereby reducing the computational load on the base station and minimizing data transmission requirements. Each edge device maintains a local database to store relevant tracking information and sends processed updates, including the target’s position and direction, back to the base station. Communication between the base station and edge devices follows a structured approach with three types of updates: one-time updates for initial settings, on-demand updates to dynamically control the schedule of the edge devices, and per-iteration updates, which include real-time tracking results sent at the end of each iteration to ensure synchronization and accuracy. This structured data flow reduces communication overhead while maintaining the system’s responsiveness and accuracy in dynamic and resource-constrained environments.

4. Experiments and Results

To evaluate the effectiveness of our TEDDY framework, we conducted two distinct experiments. The first experiment focused on tracking a person across multiple cameras in an indoor environment. The second experiment involved a smart city simulation, where we implemented a dynamic traffic light adjustment system to prioritize the movement of an emergency vehicle. In both experiments, we compared the performance of systems with and without the TEDDY framework to assess its impact. Furthermore, the second experiment demonstrated the framework’s flexibility and ability to adapt to other applications seamlessly.

4.1. Algorithms

4.1.1. Target Object Detection

To detect a target object in real-time, we utilized the YOLOv8 model, which offers both high accuracy and rapid processing speeds, making it well-suited for real-time tracking on edge devices [

31]. YOLOv8 is available in various model sizes (n, s, m, l, xl), enabling flexibility based on resource constraints and performance requirements. For our experiments, we employed the lightweight YOLOv8n model to balance computational efficiency and detection accuracy. YOLOv8n has the least number of parameters and computational load, still ensuring smooth operation on edge devices with limited resources. For both experiments, pre-trained YOLOv8n model was fine-tuned using additional data tailored to the experimental environment. This fine-tuning process enhanced the detection performance for specific objects, such as people and emergency vehicles, thereby improving the accuracy of target detection.

4.1.2. Re-ID and Target Tracking

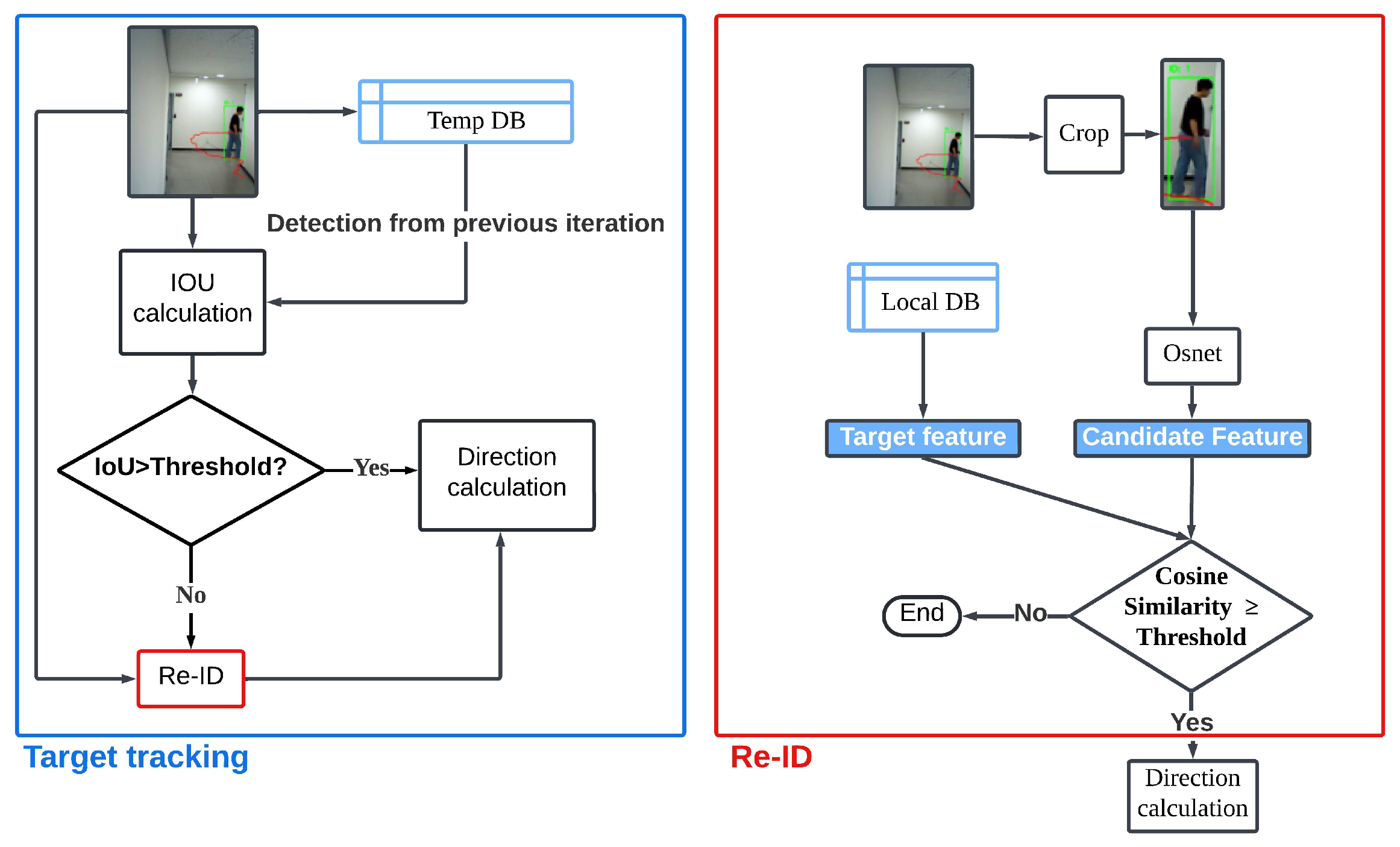

As illustrated in

Figure 3a, the process begins with the calculation of the Intersection over Union (IoU) between the detection result from the current iteration and the detected result from the previous iteration. The IoU value serves as a measure of overlap between the two detections. If the IoU exceeds a predefined threshold, which is a hyperparameter tuned during the experiment, the framework assumes that the detected object is the same target from the previous iteration. In this case, it directly proceeds to the direction calculation process, bypassing additional verification steps. However, if the IoU does not exceed the threshold, the system initiates the Re-Identification (Re-ID) process to confirm whether the detected object matches the target, as detailed in

Figure 3b.

In the Re-ID process, the detected individual is cropped from the image, and the feature map of the detected area is extracted using Osnet. Specifically, we utilize the osnet x1.0 model from the TorchReID library [

32,

33,

34], which offers superior performance among the available models in the library. Osnet is particularly well-suited for edge device implementations due to its efficiency, as it has 2 to 10 times fewer parameters compared to other models like ResNet or MobileNet, making it significantly more lightweight. After feature extraction, the system computes the cosine similarity between the candidate feature map (from the current detection) and the target feature map stored in the local database. If the similarity value exceeds a predefined threshold, another tunable hyperparameter, the framework concludes that the detected object matches the target and proceeds to the direction calculation process. Conversely, if the similarity falls below the threshold, the process terminates without further actions. This combination of IoU and Re-ID ensures accurate tracking while maintaining computational efficiency.

Additionally, during the first detection of an object, a Re-ID procedure is performed to determine whether the detected object is the actual target. In this process, the features of the detected object, obtained by cropping the relevant image, are extracted using the Re-ID model. These feature vectors are then sent to the server, allowing all edge devices in the network to share consistent target information. This ensures that the tracking process remains unified and accurate across distributed devices. If the target object is known beforehand, its feature vectors can be precomputed and distributed to edge devices through the server, bypassing the need for on-the-fly feature extraction during the first detection. To maintain clarity and avoid overcomplicating the visualization, the details of this specific case have been omitted from

Figure 3. This approach ensures that the framework remains flexible, accommodating both scenarios where the target is predefined and where it needs to be identified dynamically.

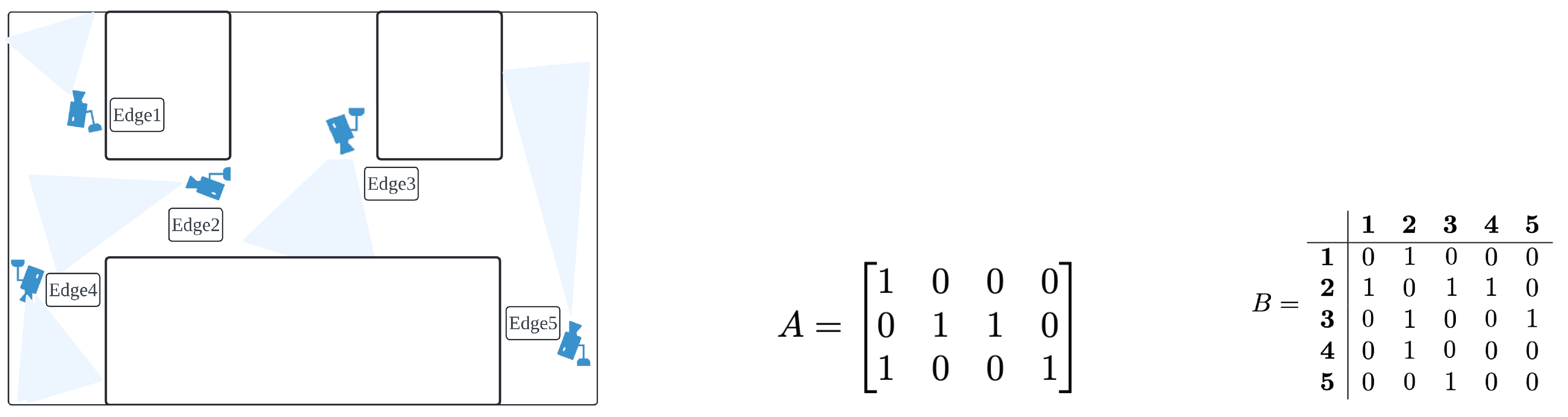

4.1.3. Camera Selection

Camera selection process is deployed to activate edge devices based on the movement of a tracked target. To implement the camera selection, the spatial relationships of the camera network are first represented using matrices. The network is visualized from the top view, and each camera location is marked as "1" on a

matrix to create the first matrix,

A. This matrix visually represents the camera layout within the network. The second matrix,

B, is an adjacency matrix that expresses how cameras are interconnected (see

Figure 4c). Camera numbers are assigned sequentially from the top-left to the bottom-right corner of matrix

A, and these numbers are used as indices in matrix

B to organize the connectivity information. The example of the camera network and the method for assigning indices can be seen in

Figure 4a,b.

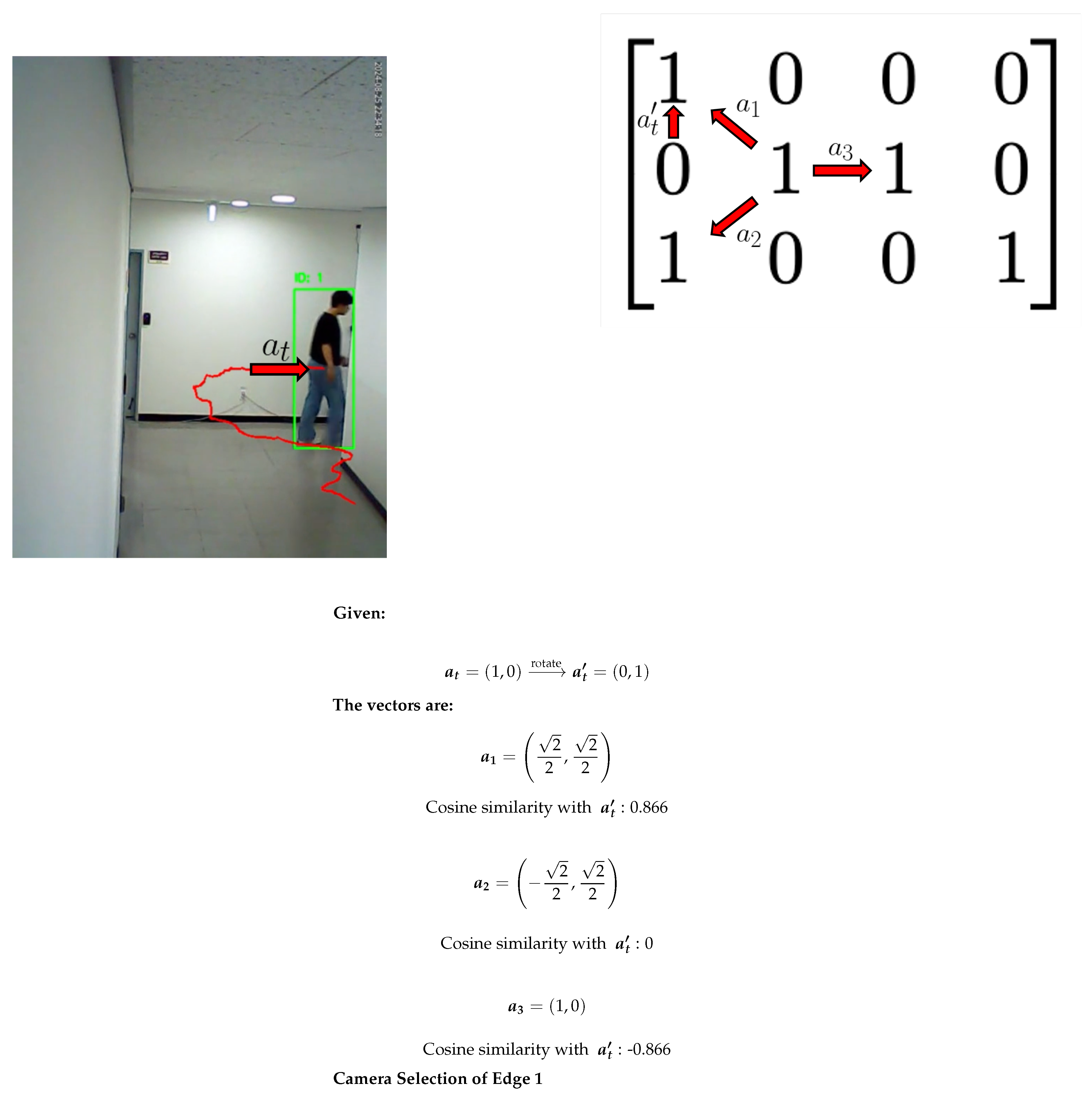

Camera selection is performed by utilizing directional vectors between nodes on matrix A. For example, when a target moves from the area covered by Camera 2 to the area covered by Camera 1, the directional vector from Camera 2 to Camera 1 is computed based on matrix A. Normalizing this vector to a magnitude of 1 yields a directional vector of . Similarly, all directional vectors from Camera 2 to its connected nodes (e.g., Cameras 1, 4, and 3) are calculated. For example, the directional vector from Camera 2 to Camera 4, , is , and the vector from Camera 2 to Camera 3, , is . These vectors represent the spatial relationships between nodes.

Next, the actual movement direction of the target is compared with the directional vectors between camera nodes to determine the next camera. When a target moves within the view of Camera 2, the average movement direction over the last 5 frames is calculated to obtain

. This process can be visually confirmed through

Figure 5a. Since camera views differ in orientation,

is rotated to align with the camera’s perspective and normalized to produce

. This normalized vector,

, represents the target’s movement direction on the Camera network considering the camera’s orientation.

Subsequently, the cosine similarity is calculated between

and the directional vectors

,

, and

derived for Camera 2. Referencing

Figure 5b,

and the directional vectors

,

, and

represented in matrix

A can be intuitively visualized.The edge corresponding to the vector with the highest cosine similarity is activated to select the next camera. This process dynamically tracks the target and ensures that the most appropriate camera is activated at each step.

Figure 5c presents the detailed procedure of the actual camera selection process for the given example. Through this methodology, camera selection is effectively implemented within the camera network.

4.2. Experiment 1 : Single Person Tracking

4.2.1. Dataset

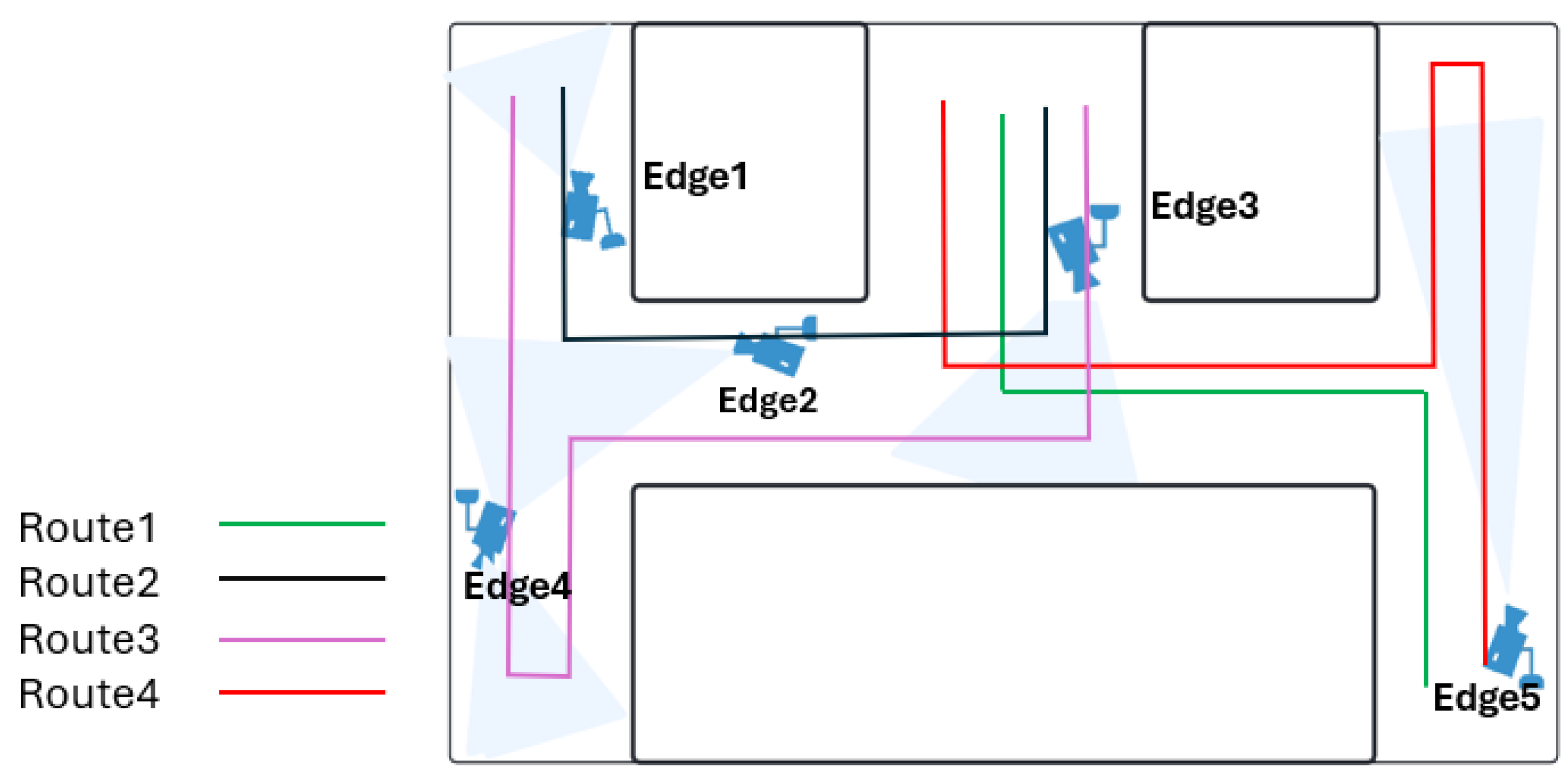

The experiments were conducted using a self-collected dataset comprising footage from five strategically positioned cameras, as outlined in

Table 1. These cameras were installed at key locations within the experimental environment to ensure optimal coverage of the target object as it navigated through multiple pre-defined routes.

Figure 6 illustrates the layout of these routes and the placement of cameras, which were designed to simulate realistic scenarios involving various behavioral patterns.

Table 1.

Dataset Overview

Table 1.

Dataset Overview

| Item |

Value |

| Number of cameras |

5 |

| Video resolution |

640 × 480 |

| Frame rate (FPS) |

30 |

| Total number of frames |

106,677 frames |

| Number of routes |

4 |

| Number of behavior types |

3 |

| Total number of tracks |

12 |

| Environment details |

Kwangwoon University |

| |

Sae-bit building |

| Route |

Behavior Type |

Frame Count |

| Route 1 |

Walking |

451 |

| |

Running |

271 |

| |

Staggering |

511 |

| Route 2 |

Walking |

781 |

| |

Running |

301 |

| |

Staggering |

721 |

| Route 3 |

Walking |

991 |

| |

Running |

661 |

| |

Staggering |

1,321 |

| Route 4 |

Walking |

751 |

| |

Running |

541 |

| |

Staggering |

991 |

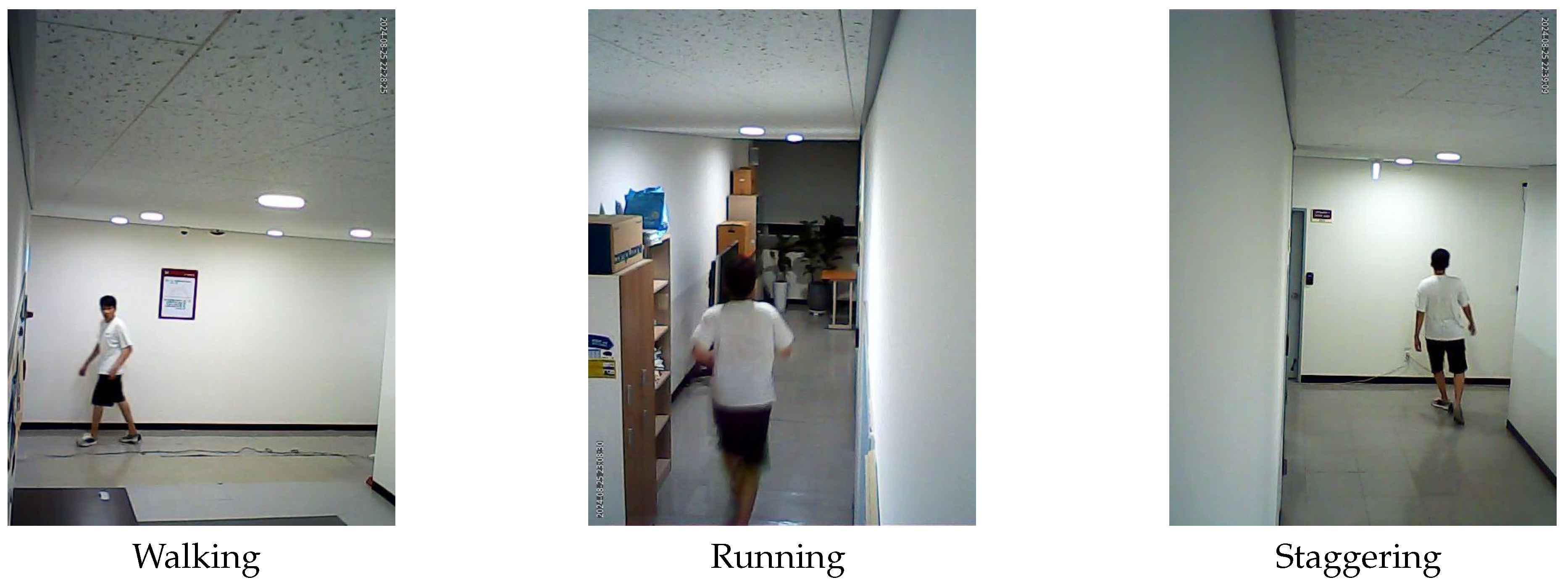

Each route in the dataset was specifically designed to encompass three types of target behaviors: walking, running, and staggering. The walking behavior represents a consistent and steady movement, reflecting the most common and predictable gait. The running behavior involves rapid movement, which presents a greater challenge for accurate tracking due to increased speed and shorter intervals between camera transitions. The staggering behavior introduces irregular and unpredictable movement patterns, characterized by abrupt changes in direction and unstable trajectories, further testing the system’s robustness.

The dataset includes a comprehensive collection of frames for each route and behavior type, providing sufficient diversity for experimental analysis. The detailed frame counts for each route and behavior type are presented in

Table 1. Additionally,

Figure 7 showcases illustrative examples of each behavior type along the various routes, offering visual insight into the complexity and variety of scenarios captured in the dataset. This well-structured and diverse dataset forms the basis for evaluating the performance of the TEDDY framework in dynamic and challenging environments.

4.2.2. Result

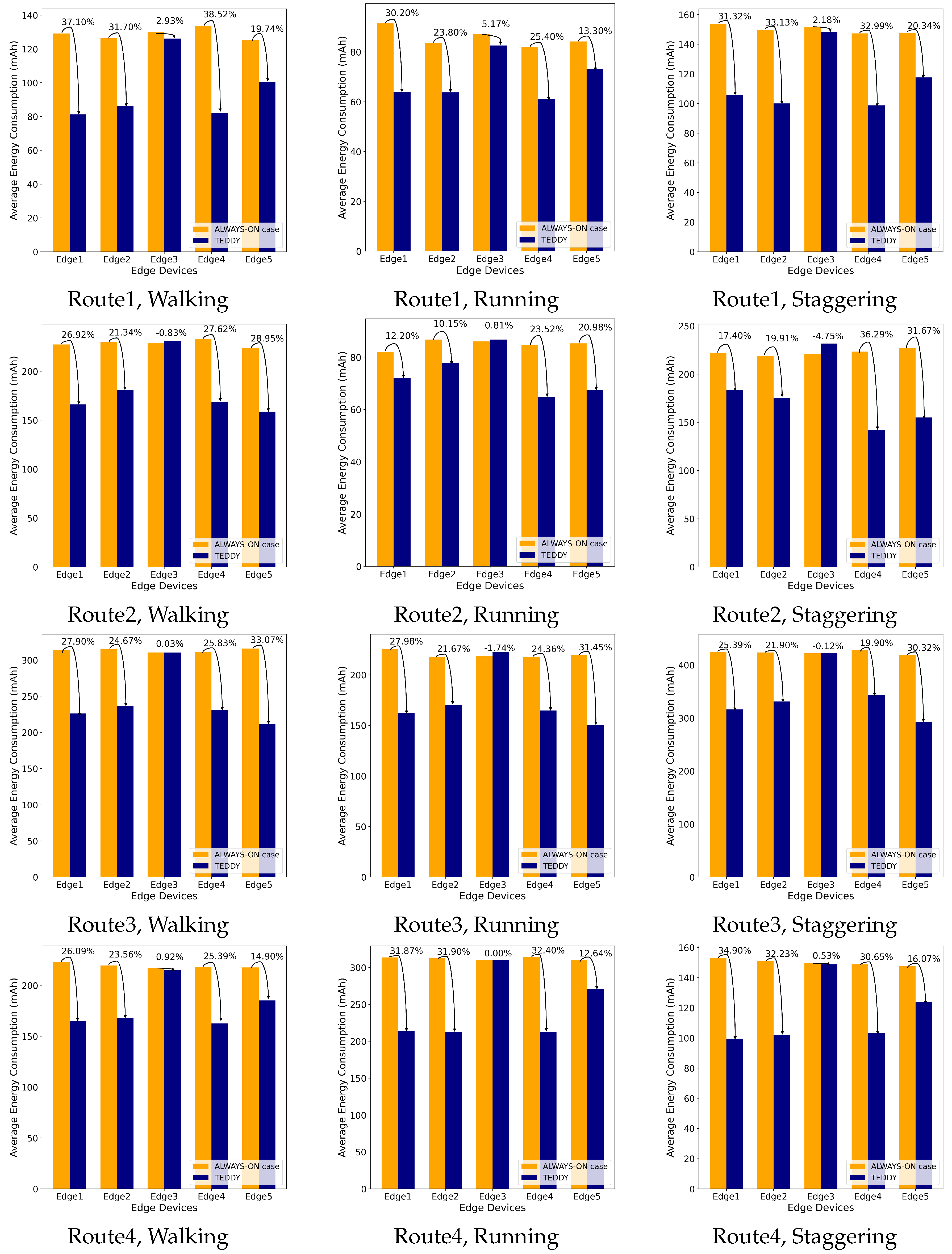

In this experiment, we evaluated the TEDDY framework by comparing its performance to a multi-camera target tracking system where all cameras remain continuously active. In the TEDDY framework, cameras located at entry points operate continuously to ensure that no individual entering or exiting the building is missed. Once a target is detected, the framework dynamically activates only the cameras expected to capture the target based on its movement and predicted trajectory. The remaining cameras are deactivated, significantly reducing unnecessary operations and improving resource efficiency. In contrast, the always-active camera method processes data from all cameras continuously, regardless of the target’s position. While this ensures comprehensive coverage, it results in substantially higher resource consumption and computational load due to the constant activity of all cameras. By dynamically managing camera activation, the TEDDY framework demonstrates a more efficient approach to resource allocation while maintaining accurate tracking capabilities. Both methods were tested using the same dataset and under identical conditions to compare their outcomes. In each experiment, power consumption and tracking performance were measured to evaluate the efficiency of the TEDDY framework.

The experimental results, as shown in

Figure 8, provide a detailed analysis of power consumption and efficiency across various routes and behavior types. The results clearly demonstrate that the TEDDY framework significantly reduces energy usage compared to the traditional method where all cameras remain continuously active. Specifically, the TEDDY framework achieved a 20.96% reduction in power consumption, highlighting the effectiveness of its dynamic camera selection mechanism. This reduction is a direct result of the framework’s ability to deactivate unnecessary cameras while ensuring that only the cameras relevant to the target’s trajectory remain active, thus enhancing overall resource efficiency.

In addition to power savings, the TEDDY framework was evaluated for its tracking accuracy in comparison to the always-active camera approach. The findings indicate that both methods achieved identical performance in terms of maintaining consistent and reliable tracking until the completion of the target’s trajectory. This demonstrates that the TEDDY framework achieves significant energy efficiency without compromising the quality of tracking performance. By effectively balancing energy optimization and operational accuracy, the TEDDY framework validates its potential as a robust and practical solution for multi-camera tracking systems in resource-constrained environments. The results reaffirm that the framework successfully optimizes energy usage while preserving high tracking effectiveness across diverse scenarios.

4.3. Experiment 2 : Traffic Light Adjustment System for an Emergency Vehicle

The purpose of Experiment 2 is to demonstrate the versatility of the TEDDY Framework beyond a simple tracking system through its application to emergency vehicles and to validate the computational efficiency by utilizing the TEDDY Framework.

4.3.1. Simulation Settings

Experiment 2 is conducted in an urban environment where an emergency vehicle drives along with other vehicles. In Experiment 2, the TEDDY framework targets the emergency vehicle for tracking. The experimental environment is set up in Unreal Engine (CARLA), which is widely used in research to simulate environments similar to the real world. The environment consists of a rectangular urban area with various vehicles driving while following traffic signals. The CARLA Python API was used to create this environment. A total of 12 CCTV cameras are set up in the experimental environment, placed at locations where vehicles within the map might change direction.

Figure 9 the simulation environment as seen from above in (a), and in (b), it captures a scene of the emergency vehicle navigating through the actual simulation setting.

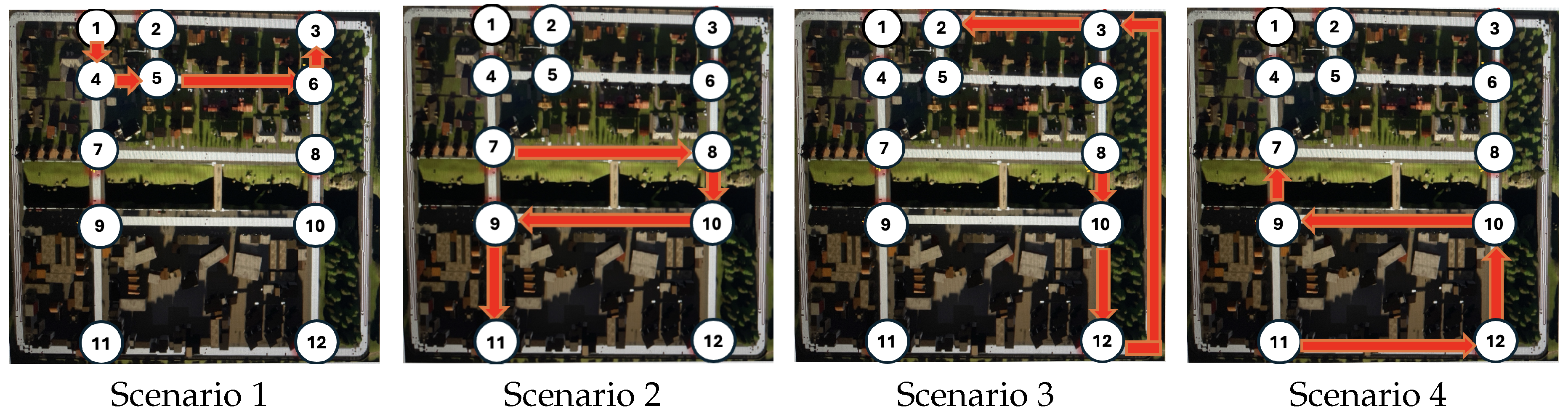

Figure 10 illustrates the four predefined paths used in the experiment, with the movement of the emergency vehicle indicated by red arrows. Each scenario was randomly selected within the CARLA simulation environment, providing diverse and realistic testing conditions. The white circles with sequential numbers represent the locations of the surveillance cameras, numbered from the top left to the bottom right of the map. Each surveillance camera is strategically positioned to monitor multiple paths, covering the front, left, and right directions. For instance, Camera 5 is oriented to provide a viewpoint toward Camera 2, ensuring comprehensive coverage along the vehicle’s route.

4.3.2. Result

In Experiment 2, the TEDDY framework was evaluated by comparing its computational efficiency to a traditional always-on camera system, similar to the analysis conducted in the previous experiment. To facilitate this comparison, the TEDDY framework, comprising 12 edge devices and a base station, was implemented on a single hardware platform. This setup allowed for a direct performance comparison, demonstrating the advantages of the dynamic scheduling mechanism in reducing unnecessary computations while maintaining high operational effectiveness. The results validate the TEDDY framework’s ability to optimize computational resources, particularly in scenarios requiring efficient and responsive tracking, such as emergency vehicle management.

In this experiment, we aimed to demonstrate the potential applicability of the TEDDY framework in controlling traffic light systems, particularly in scenarios involving emergency vehicles. While the framework was evaluated for its ability to optimize camera usage and computational efficiency, building and integrating a complete traffic light control system was beyond the scope of this study. Therefore, we focused on simulating the target tracking and trajectory prediction capabilities of the framework, which are fundamental components for implementing such traffic control applications. This approach highlights the framework’s potential for future extensions into real-world traffic management systems without compromising the primary focus of this work. In each scenario, we measured the number of processed frames and the computational load for both the always-on camera system and our TEDDY framework, concentrating exclusively on computations related to the tracking task. This focused evaluation ensured a direct comparison of the frameworks’ efficiency in handling tracking operations under identical conditions. The results revealed the advantages of the TEDDY framework in minimizing computational overhead while maintaining tracking accuracy, demonstrating its ability to optimize resource utilization compared to the always-on approach. Detailed results are presented in the subsequent sections to illustrate these performance improvements.

Table 2 summarizes the experimental results, demonstrating the significant computational load reduction achieved by the TEDDY framework compared to the always-on system. By limiting inference to the edge devices where the target is present, the TEDDY framework minimizes unnecessary computations and optimizes resource utilization.

As shown in

Table 2, the number of processed frames decreased substantially across all scenarios. For instance, in Scenario 2 (tracking a firetruck along the route monitored by Cameras 7-8-10-9-11), the always-on system performed inference on all 12 edge devices, processing a total of 20,472 frames. In contrast, the TEDDY framework only processed 1,697 frames, distributed among Camera 7 (127 frames), Camera 8 (464 frames), Camera 10 (150 frames), Camera 9 (625 frames), and Camera 11 (331 frames). This represents a significant reduction in processed frames, resulting in a more efficient system.

The computational load reduction across all scenarios exceeded 90%, with slight variations depending on the length of the routes. This consistent trend highlights the framework’s ability to reduce computations by dynamically selecting cameras based on the target’s location. Since this experiment focused on single-object tracking, the computational demand decreased to approximately , where N is the number of cameras in the network. In this experiment, with 12 edge devices, the target was present in only one camera frame at any given time, further enhancing computational efficiency.

Moreover, the time required for the camera selection process in the TEDDY framework was minimal and had no impact on tracking performance. As the number of edge devices increases, the computational efficiency of the framework is expected to improve further, making it highly scalable for larger networks. These results validate the effectiveness of the TEDDY framework in significantly reducing computational load while maintaining high tracking accuracy.

4.4. Implementation Detail

In Experiment 1, five Raspberry Pi 5 devices were used as edge devices, each running Ubuntu 24.04 as the operating system and equipped with 8 GB of RAM. These devices were responsible for performing local computations as part of the TEDDY framework. A computer with an AMD Ryzen 5 5600HS processor and 16 GB of RAM served as the base station, acting as the central decision-making unit for camera scheduling and target trajectory predictions. The base station also operated on Ubuntu 24.04 to ensure compatibility across the system.

The video recordings used in the experiment were captured using cameras with a maximum resolution of 640 × 480 pixels, ensuring consistent video quality across all edge devices. To measure power consumption accurately, a Beezap Type-C Voltage Current Tester was utilized. This setup provided a controlled environment to evaluate the TEDDY framework’s performance in terms of computational efficiency, power consumption, and tracking accuracy, while highlighting its suitability for resource-constrained edge hardware configurations.

In Experiment 2, evaluations were conducted on hardware equipped with a 12th Gen Intel i7-12800HX processor, an NVIDIA 3080 Ti GPU with 16 GB VRAM, and running Linux 22.04 LTS. Since the evaluation was conducted on a single hardware platform, it was assumed that the camera would be activated 1 to 3 frames later, proportional to the time required for Camera Selection and communication between the base station and the edge devices. The experiment involved four scenarios, each with varying frame counts: Scenario 1 consisted of 1,267 frames, Scenario 2 included 1,706 frames, Scenario 3 had 1,565 frames, and Scenario 4 processed 1,491 frames. These scenarios were designed to test the TEDDY framework’s performance in handling dynamic tracking tasks within diverse and realistic settings.

5. Discussion

The TEDDY framework represents a significant advancement in target tracking by leveraging edge-based distributed smart cameras with dynamic camera selection. The results from both experiments validate its effectiveness in optimizing resource utilization without compromising tracking accuracy, highlighting its potential as a practical and scalable solution for real-world applications.

In Experiment 1, the framework demonstrated its efficiency in single-person tracking scenarios across various routes and behaviors. The ability to dynamically activate and deactivate edge devices based on the target’s predicted path led to an average resource consumption reduction of 20.96%. This substantial improvement underscores the effectiveness of the dynamic camera selection mechanism, which minimizes redundant computations while maintaining consistent tracking performance. The experiment also highlighted the versatility of the framework, successfully adapting to diverse behavioral patterns such as walking, running, and staggering, which pose varying challenges to tracking systems.

In Experiment 2, the TEDDY framework was applied to a traffic light adjustment system for emergency vehicles in a simulated urban environment. The results revealed a significant computational load reduction, achieving equivalent tracking performance with only 8–9% of the computational resources required by the always-on system. This efficiency was achieved by limiting inference to cameras most likely to capture the target based on trajectory predictions, thus reducing unnecessary computations. The scalability of the TEDDY framework is evident, as these results suggest that its efficiency would be even more pronounced in larger-scale camera networks with greater numbers of edge devices.

The key contribution of this framework lies in its ability to balance computational efficiency with operational accuracy, making it well-suited for resource-constrained environments. Unlike traditional always-on systems, which are computationally intensive and energy-inefficient, the TEDDY framework provides a scalable and energy-aware alternative. Its success in both single-person tracking and traffic management scenarios demonstrates its adaptability and applicability to a wide range of use cases, from smart city infrastructure to emergency response systems.

However, while the experiments validate the framework’s capabilities, there are areas for further exploration. For instance, the current implementation focuses on single-object tracking, and extending the framework to handle multi-object tracking in real-time could broaden its applicability. Additionally, integrating other functionalities, such as predictive analytics for target movement in complex scenarios or enhanced privacy-preserving mechanisms, could further strengthen its practicality. The use of the TEDDY framework in larger-scale networks and its deployment in real-world settings also warrant further investigation.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the TEDDY framework represents a robust and efficient solution for target tracking in edge-based camera networks, achieving substantial reductions in computational load and energy consumption without compromising tracking accuracy. By dynamically activating and deactivating cameras based on the target’s predicted trajectory, the framework optimizes resource utilization while maintaining consistent tracking performance. These findings demonstrate the potential of the TEDDY framework as a scalable and adaptable approach, particularly suited for smart cities, emergency response systems, and other resource-constrained applications. The experimental results validate its effectiveness across a range of scenarios, providing a strong foundation for future research and development.

For future research, enhancing the TEDDY framework’s camera selection methodology by incorporating geometric information could further improve its precision. Current camera selection methods lack geometric alignment between the projected network matrix and the actual physical camera placements. Integrating geometric data into the selection process would refine the framework’s ability to predict target trajectories, enabling more accurate and efficient camera activation strategies.

Additionally, extending the framework to address more complex and dynamic environments is crucial. Applications such as high-speed object tracking on highways or multi-object tracking in crowded, fast-paced environments would require advanced tracking algorithms and high-performance hardware tailored to these challenges. These adaptations would broaden the applicability of the TEDDY framework to diverse real-world scenarios.

The framework also has potential applications in dynamic camera networks, such as drone-based systems, which require new methodologies for camera selection. Exploring these dynamic networks would enable the TEDDY framework to move beyond static setups and accommodate evolving use cases. Furthermore, for ultra-large-scale camera networks typical of urban environments, efficiency could be enhanced by grouping multiple camera edges into single nodes or employing hierarchical network structures. These modifications would improve scalability while maintaining the framework’s efficiency and accuracy, paving the way for its adoption in expansive, real-world applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, J.Y and J.L ; software,J.Y, J.L and I.L; investigation, J.Y, J.L and I.L; resources,I.L; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y and J.L ; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, all authors.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration,Y.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L.

Funding

The present research has been conducted by the Research Grant of Kwangwoon University in 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT in order to enhance the clarity and coherence of the few parts of the manuscript, refine technical explanations, and streamline the drafting process. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upcroft, B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE; 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E. A New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems. Journal of Basic Engineering 1960, 82, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple Online and Realtime Tracking with a Deep Association Metric. 2017; arXiv:cs.CV/1703.07402. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Towards Real-Time Multi-Object Tracking. 2020; arXiv:cs.CV/1909.12605. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zeng, W.; Liu, W. FairMOT: On the Fairness of Detection and Re-identification in Multiple Object Tracking. International Journal of Computer Vision 2021, 129, 3069–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, P.; Wang, D.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, P.; Lu, H. Towards Grand Unification of Object Tracking. 2022; arXiv:cs.CV/2207.07078. [Google Scholar]

- Braso, G.; Leal-Taixe, L. Learning a Neural Solver for Multiple Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Huang, Z.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Z. Learnable Graph Matching: Incorporating Graph Partitioning with Deep Feature Learning for Multiple Object Tracking. 2021; arXiv:cs.CV/2103.16178. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.; Li, F.; Ciptadi, A.; Rehg, J.M. Multiple Hypothesis Tracking Revisited. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015; pp. 4696–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amosa, T.I.; Sebastian, P.; Izhar, L.I.; Ibrahim, O.; Ayinla, L.S.; Bahashwan, A.A.; Bala, A.; Samaila, Y.A. Multi-camera multi-object tracking: A review of current trends and future advances. Neurocomput. 2023, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, D.; Ellis, T.; Black, J. Bridging the gaps between cameras. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2004. CVPR 2004., 2004, Vol. 2, pp. II–II. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Medioni, G. Exploring context information for inter-camera multiple target tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision; 2014; pp. 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styles, O.; Guha, T.; Sanchez, V.; Kot, A. Multi-Camera Trajectory Forecasting: Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction in a Network of Cameras. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2020; pp. 4379–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Buduru, A.B. Foresee: Attentive Future Projections of Chaotic Road Environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and MultiAgent Systems, Richland, SC, 2018; AAMAS ’18, p. 2073–2075.

- Ye, M.; Shen, J.; Lin, G.; Xiang, T.; Shao, L.; Hoi, S.C.H. Deep Learning for Person Re-Identification: A Survey and Outlook. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2022, 44, 2872–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristani, E.; Tomasi, C. Features for Multi-Target Multi-Camera Tracking and Re-Identification. 2018; arXiv:cs.CV/1803.10859. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, N.; Bai, S.; Xu, Y.; Xing, C.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, W. Online Inter-Camera Trajectory Association Exploiting Person Re-Identification and Camera Topology. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, New York, NY, USA, 2018; MM ’18, p. 1457–1465. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Staudt, E.; Faltemier, T.C.; Roy-Chowdhury, A.K. A Camera Network Tracking (CamNeT) Dataset and Performance Baseline. 2015 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision 2015, 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Cao, L.; Chen, X.; Huang, K. An equalised global graphical model-based approach for multi-camera object tracking. 2016; arXiv:cs.CV/1502.03532. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.W.; Lai, C.C.; Lee, P.J.; Chen, C.S.; Hung, Y.P. Adaptive Learning for Target Tracking and True Linking Discovering Across Multiple Non-Overlapping Cameras. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2011, 13, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleuret, F.; Berclaz, J.; Lengagne, R.; Fua, P. Multicamera People Tracking with a Probabilistic Occupancy Map. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2008, 30, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Andriluka, M.; Andres, B.; Schiele, B. Multiple People Tracking by Lifted Multicut and Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, J.; Li, L. Distributed optimization for global data association in non-overlapping camera networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 Seventh International Conference on Distributed Smart Cameras (ICDSC); 2013; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristani, E.; Solera, F.; Zou, R.S.; Cucchiara, R.; Tomasi, C. Performance Measures and a Data Set for Multi-Target, Multi-Camera Tracking. 2016; arXiv:cs.CV/1609.01775. [Google Scholar]

- Ristani, E.; Tomasi, C. Tracking Multiple People Online and in Real Time. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ACCV 2014; Cremers, D., Reid, I., Saito, H., Yang, M.H., Eds.; Cham, 2015; pp. 444–459. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Anand, S.; Kaul, S.K. Reinforcement Learning Based Querying in Camera Networks for Efficient Target Tracking. Proceedings of the International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling 2021, 29, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Anand, S.; Kaul, S.K. Intelligent querying for target tracking in camera networks using deep Q-learning with n-step bootstrapping. Image and Vision Computing 2020, 103, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Anand, S.; Kaul, S.K. Intelligent Camera Selection Decisions for Target Tracking in a Camera Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2022; pp. 3083–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, S.V.; Wu, Y.; Liu, G.; Kompella, R.; Liu, L. Amplifying Object Tracking Performance on Edge Devices. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 5th International Conference on Cognitive Machine Intelligence (CogMI); 2023; pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.; Lee, M.; Lim, C. Towards Real-Time On-Drone Pedestrian Tracking in 4K Inputs. Drones 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLOv8, 2023.

- Zhou, K.; Xiang, T. Torchreid: A Library for Deep Learning Person Re-Identification in Pytorch. arXiv preprint, 2019; arXiv:1910.10093 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, Y.; Cavallaro, A.; Xiang, T. Omni-Scale Feature Learning for Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the ICCV; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, Y.; Cavallaro, A.; Xiang, T. Learning Generalisable Omni-Scale Representations for Person Re-Identification. TPAMI 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

High-level diagram of the TEDDY framework: The target is represented as a person, with three edges shown. Both the type of target and the number of edges can vary.

Figure 1.

High-level diagram of the TEDDY framework: The target is represented as a person, with three edges shown. Both the type of target and the number of edges can vary.

Figure 2.

Overview of the TEDDY Framework. (a) System architecture illustrating the base station’s role in scheduling and communicating with edge devices, which process image data locally and send target position updates. (b) An example of iterative edge device activation and deactivation, showcasing the dynamic scheduling mechanism across multiple iterations of the TEDDY framework. (c) Overall architecture of the proposed TEDDY framework.

Figure 2.

Overview of the TEDDY Framework. (a) System architecture illustrating the base station’s role in scheduling and communicating with edge devices, which process image data locally and send target position updates. (b) An example of iterative edge device activation and deactivation, showcasing the dynamic scheduling mechanism across multiple iterations of the TEDDY framework. (c) Overall architecture of the proposed TEDDY framework.

Figure 3.

Diagram of (a) target tracking process and (b) re-identification(Re-ID) process for our experiments.

Figure 3.

Diagram of (a) target tracking process and (b) re-identification(Re-ID) process for our experiments.

Figure 4.

(a) represents the top view of a camera network. The positions of the cameras in (a) are modeled on an matrix (), as shown in (b). The locations marked with ’1’ in (b) are treated as nodes, and the adjacency matrix of the matrix A is then represented in (c) as Matrix B.

Figure 4.

(a) represents the top view of a camera network. The positions of the cameras in (a) are modeled on an matrix (), as shown in (b). The locations marked with ’1’ in (b) are treated as nodes, and the adjacency matrix of the matrix A is then represented in (c) as Matrix B.

Figure 5.

(a) The direction of the target tracked in the edge device. (b) The representation of , which is a rotated version of , along with . (c) An example where actual camera selection is performed.

Figure 5.

(a) The direction of the target tracked in the edge device. (b) The representation of , which is a rotated version of , along with . (c) An example where actual camera selection is performed.

Figure 6.

Illlustratioon of routes. Each scenario is designed for the object to pass through a minimum of two and a maximum to four cameras, navigating through two or more intersections.

Figure 6.

Illlustratioon of routes. Each scenario is designed for the object to pass through a minimum of two and a maximum to four cameras, navigating through two or more intersections.

Figure 7.

Illustrative Images of Target Behaviors Across Different Routes

Figure 7.

Illustrative Images of Target Behaviors Across Different Routes

Figure 8.

Improvement in the performance across routes and behavior types

Figure 8.

Improvement in the performance across routes and behavior types

Figure 9.

(a) This map represents the simulated urban environment (CARLA) built for conducting the experiment. To predict the direction of the vehicle, cameras were positioned at locations where vehicles might change direction, with arrows indicating the camera locations. (b) A scene collected within Unreal Engine that was used in the experiment.

Figure 9.

(a) This map represents the simulated urban environment (CARLA) built for conducting the experiment. To predict the direction of the vehicle, cameras were positioned at locations where vehicles might change direction, with arrows indicating the camera locations. (b) A scene collected within Unreal Engine that was used in the experiment.

Figure 10.

Each scenario route includes a total of five cameras. The emergency vehicle starts at the location of the first numbered camera in each scenario. (a) Scenario 1 follows the route 1-4-5-6-3, (b) Scenario 2 follows 7-8-10-9-11, (c) Scenario 3 follows 8-10-12-3-2, and (d) Scenario 4 follows 11-12-10-9-7

Figure 10.

Each scenario route includes a total of five cameras. The emergency vehicle starts at the location of the first numbered camera in each scenario. (a) Scenario 1 follows the route 1-4-5-6-3, (b) Scenario 2 follows 7-8-10-9-11, (c) Scenario 3 follows 8-10-12-3-2, and (d) Scenario 4 follows 11-12-10-9-7

Table 2.

Inference Frames and Computation: Comparison with and without the TEDDY Framework.

Table 2.

Inference Frames and Computation: Comparison with and without the TEDDY Framework.

| Scenario (Route) |

Total Frames |

Always-on |

TEDDY (Per Camera) |

Computational Load Ratio |

| 1 (1-4-5-6-3) |

1267 |

15204 |

1254 (101, 374, 109, 339, 331) |

8.07% |

| 2 (7-8-10-9-11) |

1706 |

20472 |

1697 (127, 464, 150, 625, 331) |

8.63% |

| 3 (8-10-12-3-2) |

1565 |

18780 |

1554 (105, 124, 305, 615, 405) |

8.31% |

| 4 (11-12-10-9-7) |

1491 |

17892 |

1484 (101, 439, 204, 516, 224) |

8.29% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).