5.1. The MTC Problem

In this section the ILP, , is formulated that solves the MTC problem. When tracking moving objects, should be updated and computed at each time step.

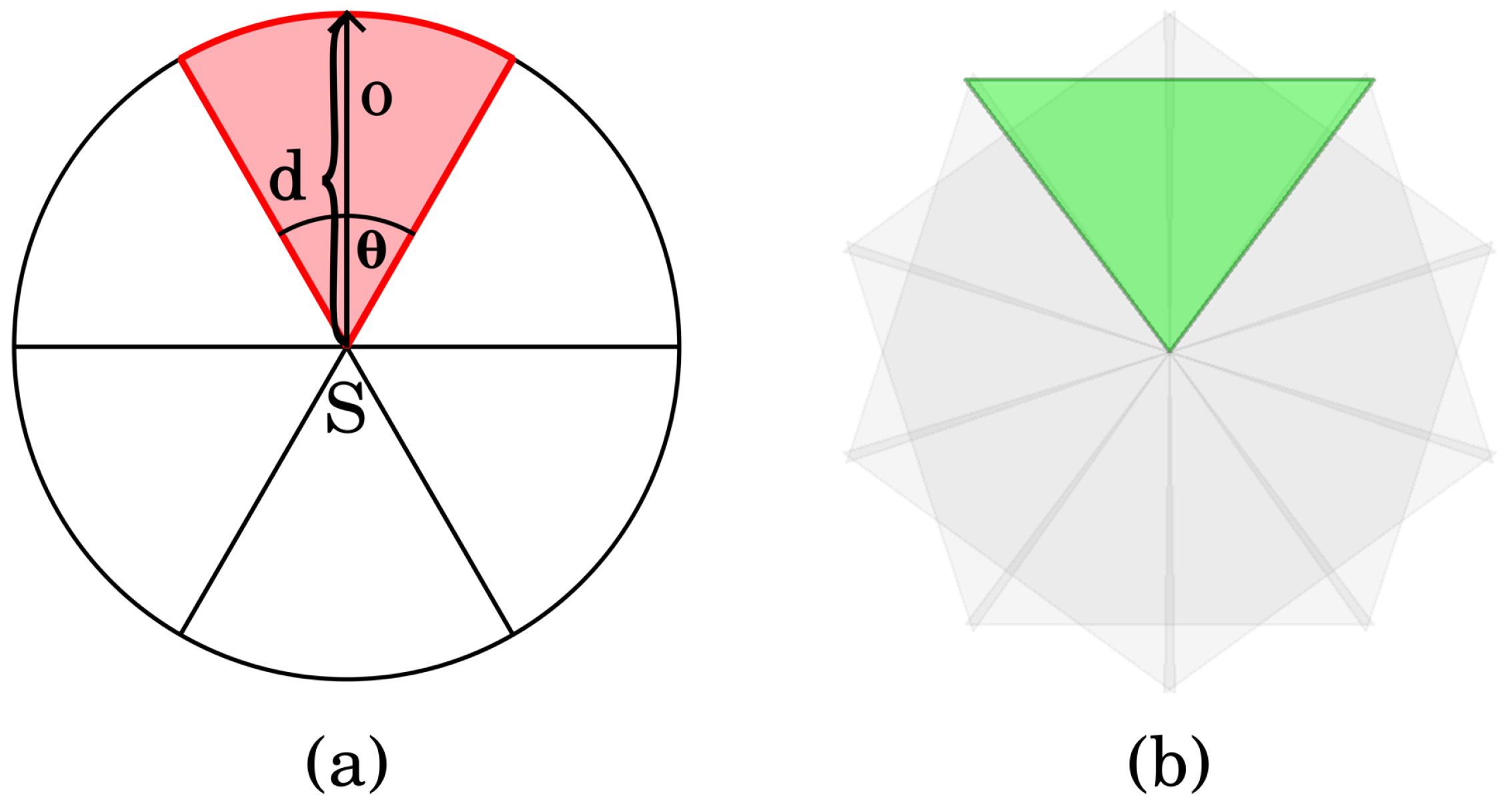

As before, let be the sensor network deployed on the open belt. Let be the set of targets. In addition to the actual sectors of the sensors, to each target a dummy sector is assigned. This sector covers only the given target and does not belong to any sensor (Alternatively, it can also be said that each dummy sector belongs to a new sensor that only has this sector, or the rest of its sectors do not cover any targets.). The role of the dummy sectors will become apparent soon. If denotes the number of the real sectors, then the total number of sectors is , where m is the number of targets.

The elements of the variable vector of will represent whether a sector is selected to be active or not, hence they can take 0 or 1 values. It is assumed that the last m elements of correspond to the dummy sectors.

The cost vector,

, is defined as follows:

In other words, the element of is 0 if it represents a real sector, and 1 otherwise. The aim is to minimize , where is the dot product of and . Obviously, is minimized if as few dummy sectors as possible are used to cover the targets.

As constraints of , two requirements need to be expressed. Firstly, it needs to be guaranteed that each solution encodes a permissible sector selection. Secondly, this permissible sector selection must cover all targets. Note that dummy sectors were introduced specifically to ensure the existence of such permissible sector selections. Since, clearly, a permissible sector selection containing all dummy sectors always covers all targets.

Formally,

is:

Basically, the elements together form the incidence matrix of the sensors and their sectors. Note that if the element of , , represents a dummy sector then is 0 for all sectors, i.e., for all i.

The elements together constitute the incidence matrix between the targets and the sectors.

It is easy to see that if Inequality

2 is satisfied then

encodes a permissible sector selection. Meanwhile, Inequality guarantees that each target is covered by at least one sector. Furthermore, the minimality condition ensures that among the permissible selections that provide a complete coverage, the ILP solutions will be those where the number of dummy sector used is minimal, or to put it differently, the number of targets covered by real sectors is maximal. All together this shows that a solution of

encodes a solution to the MTC problem.

Further considerations.

Optionally, the number of usable sensors can also be limited. Simply add inequality

to the constraints of

. Here,

Evidently, if is a solution to this extended version of then in the encoded permissible sector selection at most r sectors, and consequently r sensors, are used.

Note also that the first elements of are 0, which means additional costs can be introduced for the real sectors. For example, if all these elements are set to 1 and the cost of using a dummy sector is higher than the number of the real sectors, then a solution to this modified ILP also minimizes the number of employed sensors. Alternatively, the sum of the angles of rotation required to move from one sector selection to another can be minimized as well.

Lastly, the targets can also be distinguished from each other. For example, if target t must be covered and there is a real sector capable of covering it, then the dummy sector corresponding to t should not be added to . This ensures that t is covered by a real sector in any solution.

The targets can also be distinguished from each other based on the costs assigned to their associated dummy sectors. Suppose that the set of targets contains both static and moving targets. Then, for example, if , where and denote the costs of the dummy sectors of static and moving targets respectively, then covering 4 moving targets is equally important as covering 1 static target.

5.2. The MTCBC-k Problem

In the ILP,

, that solves the MTCBC-k problem in addition to covering the maximum number of targets, k-barrier coverage must also be ensured. Recall that by Theorem 1, an open belt is k-barrier covered by a permissible sector selection

if and only if there are

k vertex-disjoint paths from

s to

t in the coverage graph representing

,

. In what follows, a network graph with the appropriate capacities will be constructed in such a way that the size of the maximum flow will be equal to the maximum number of these vertex-disjoint paths (When Menger’s theorem is proven by reducing it to the Max-flow min-cut theorem, it is shown that for any undirected graph with selected vertices

s and

t, a network can be created where the value of the maximum flow is equal to the number of vertex-disjoint paths between

s and

t[

18]. Here, basically, the same construction is utilized.). The maximum flow problem can be formulated as a linear program, and this construction will be used in

to guarantee k-barrier coverage.

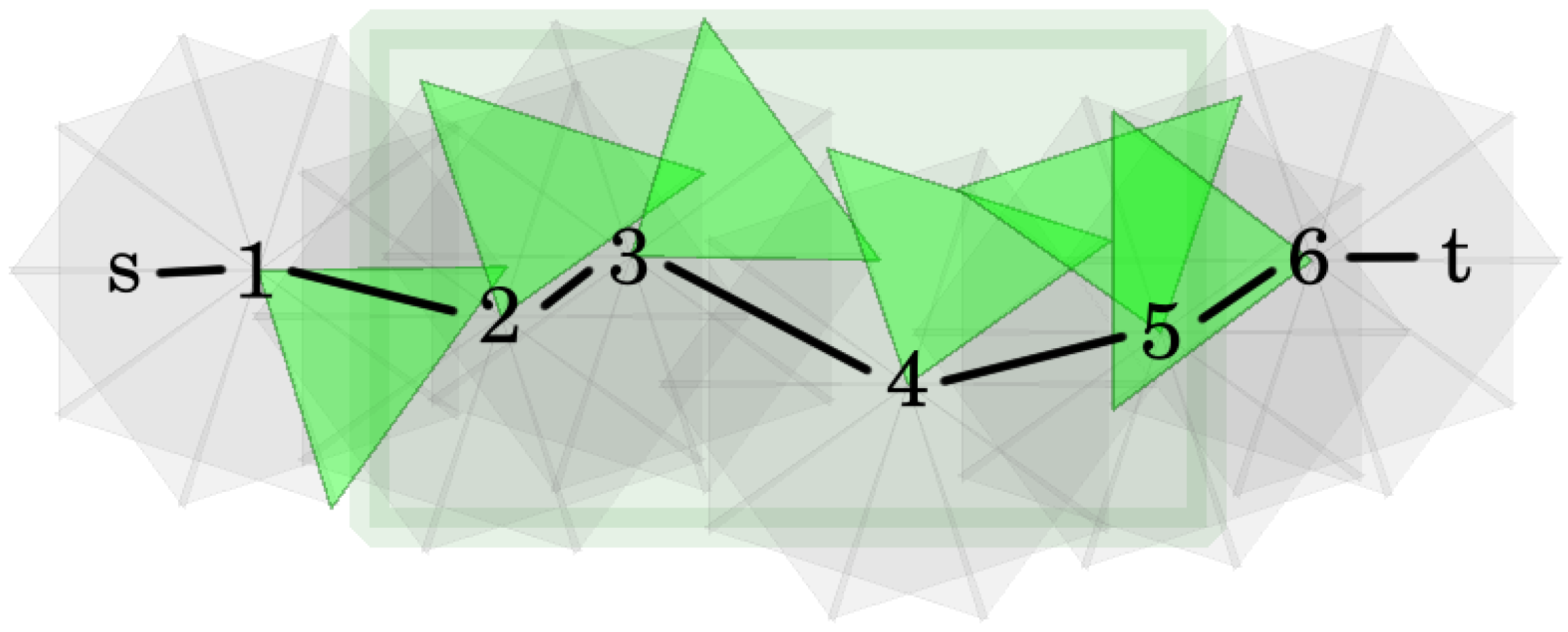

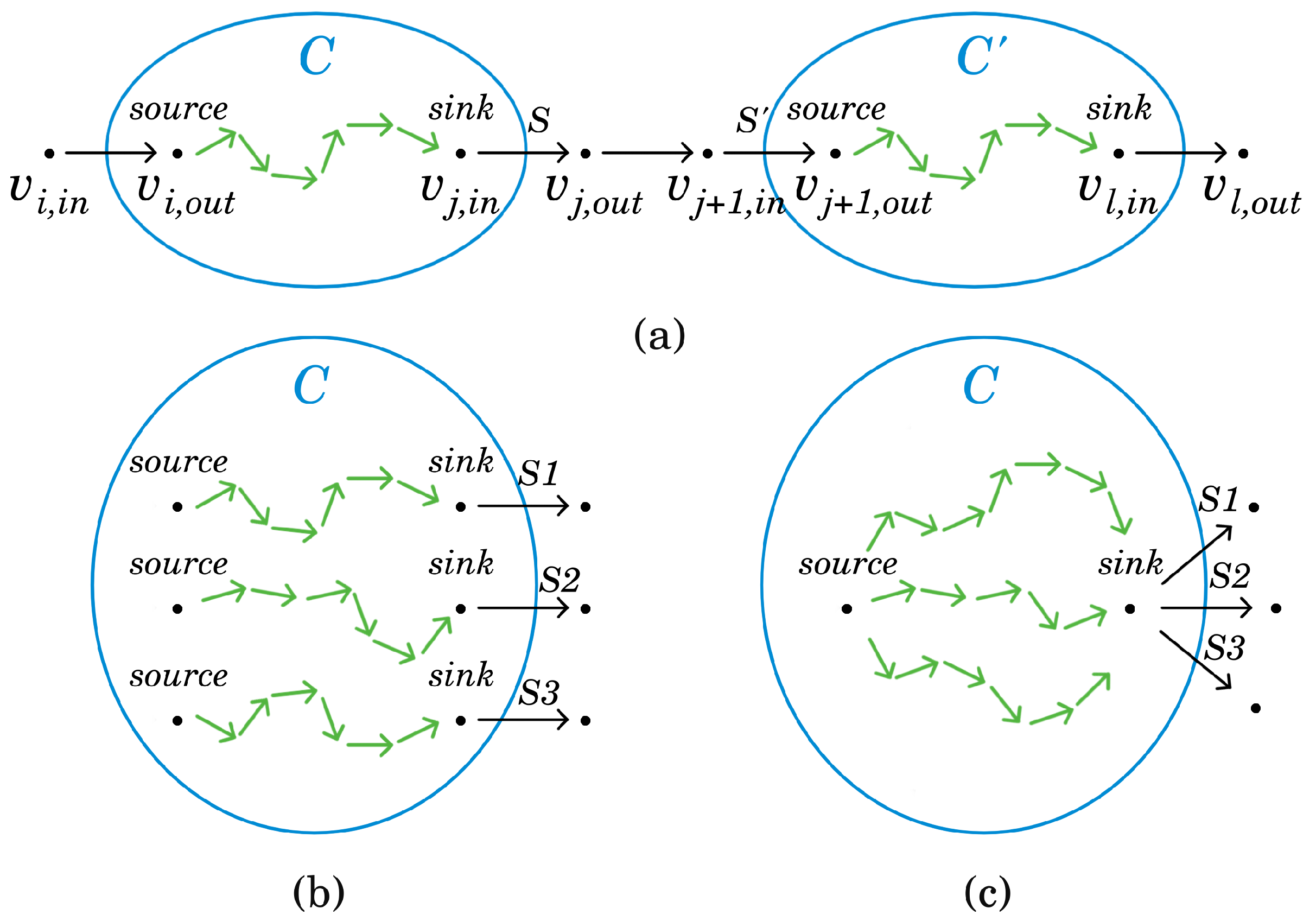

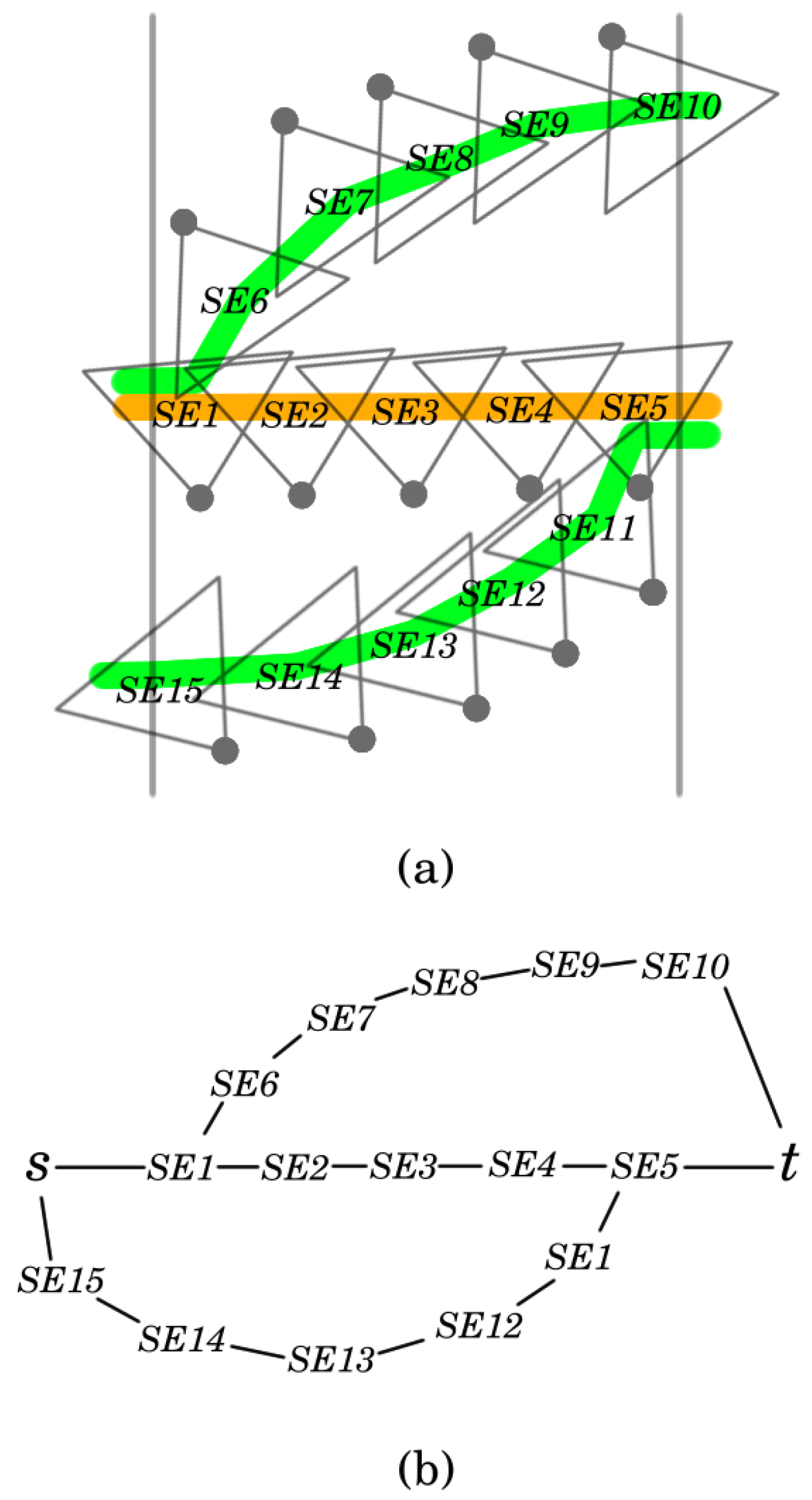

Let be an open belt with deployed sensor network . Denote by the set of targets. In the construction of the aforementioned network graph, first a coverage graph, , is created. This will be very similar to the coverage graph of a permissible sector selection. The only difference is that, in this case, not just a single permissible sector selection will be represented, but all of them. Next, will be modified in two steps. First, since capacities and flows can be defined on edges and represents sectors as vertices, these vertices will be replaced with edges. Then, the undirected edges will be converted into directed ones.

Considering the details, as in the case of a coverage graph belonging to a permissible sector selection, the vertices of stand for sectors of and the left and right boundaries of the open belt. These last two vertices are denoted by s and t. The edges of s and t can be defined exactly in the same way as before. Two sector vertices are connected if the sectors belong to different sensors and their intersection is not empty.

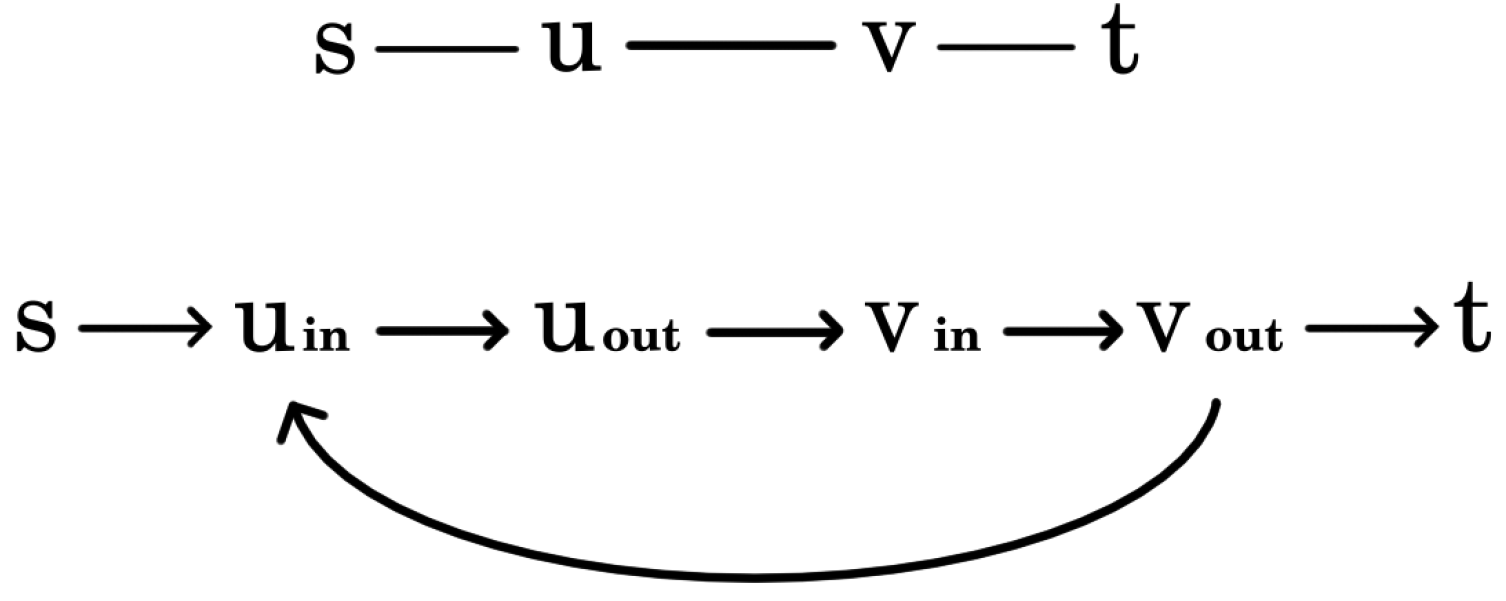

Next, each sector vertex

v of

should be substituted by a directed edge

. Finally, the remaining undirected edges of

are changed to directed ones. Edges with

s (or

as an endpoint should be converted to edges originating from

s (or ending in

t). Additionally, each edge

between sector vertices should be replaced with two directed edges:

and

. An example can be found in

Figure 3. Finally, the capacity of the edges derived from sector vertices is set to 1, while the capacity of the remaining edges is defined to be infinity. Denote the resulting network as

.

Definition 6.

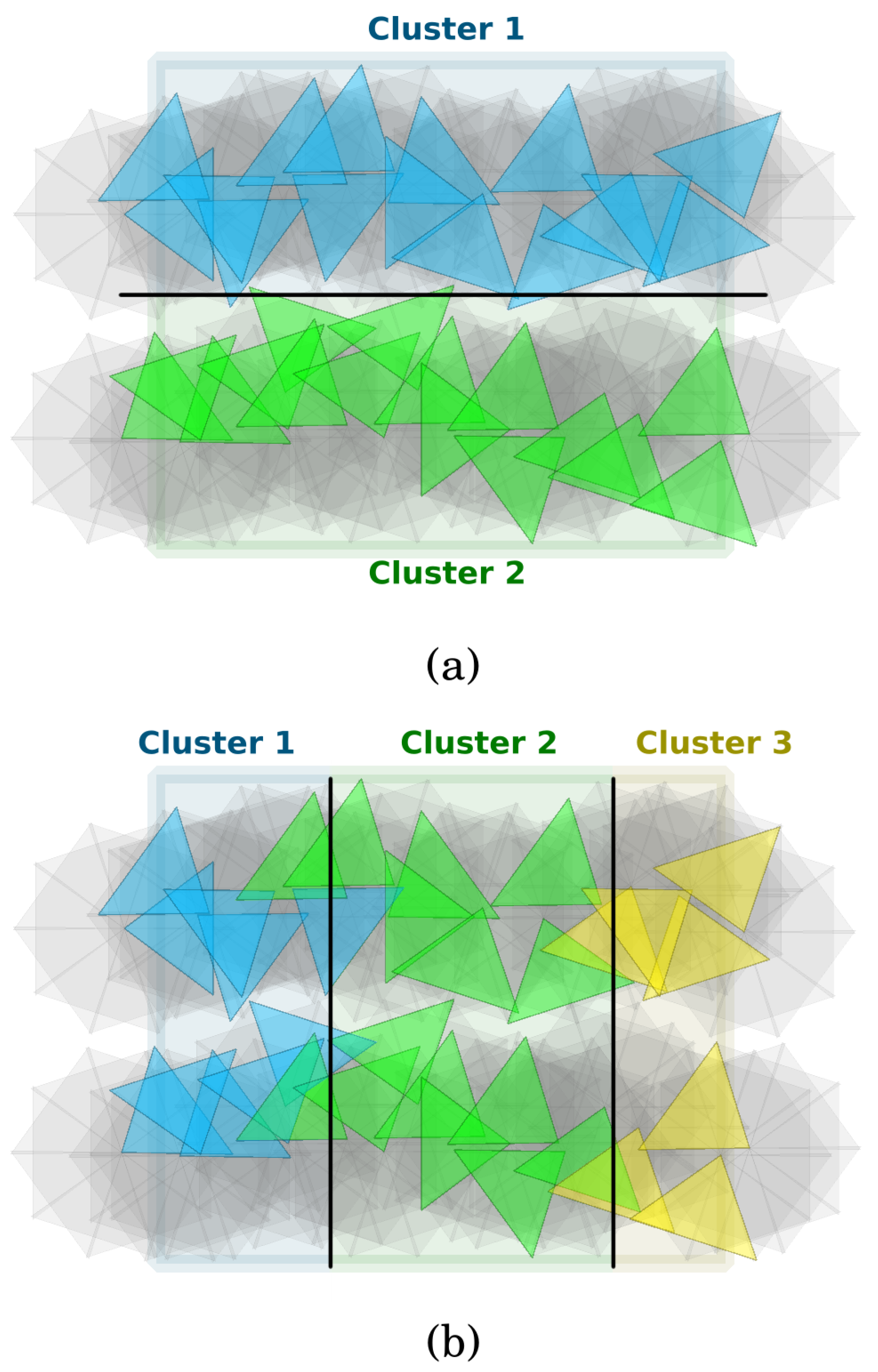

With the above notations, a flow f in ispermissibleif there are no two sectors represented by the sector edges with positive flow that belong to the same sensor. Here, a sector edge is an edge derived from sector vertex u in .

Theorem 2. With the above notations, there is a permissible sector selection, , in that provides k-barrier coverage on if and only if there exists a permissible flow of value k from s to t in .

Proof. By Theorem 1, is k-barrier covered by if and only if there are k vertex-disjoint paths from s to t in . From the definition of a permissible sector selection it follows that no two sectors involved in these paths belong to the same sensor. is a subgraph of , hence these paths are also included in . Now, note that if is a path in , where are sector vertices, then is a directed path in , and vice versa. Thus, there exist k different paths from s to t in such that no two sector edges in the paths represent sectors that belong to the same sensor. The capacities of sector and non-sector edges are 1 and ∞ respectively, therefore on each such path a flow of value 1 can go from s to t. Since the number of these paths is k, this proves the existence of a permissible flow of value k from s to t in . By reversing the above reasoning, the other direction of the statement can also be proven. □

Remark 1.

Paths in where no two sectors, represented by the sector edges of these paths, belong to the same sensor, are calledsensor-disjoint. Consider a flow of value k in . In the proof of Theorem 2 it has just been shown that the edges with positive flow form k sensor-disjoint paths from s to t. Obviously, sensor-disjoint paths do not even share a common edge. This is because at least one ending vertex of each edge in represents a sector.

Based on Theorem 2, when formulating , the existence of a permissible flow of value k needs to be ensured. This in turn guarantees the existence of a permissible sector selection providing k-barrier coverage on .

The elements of the variable

of

stand for sector, non-sector edges of

, and dummy sectors as in the case of

. Their numbers are

and

m respectively, where

m is the number of targets. It is also assumed that the elements appear in

in the aforementioned order. The first

elements represent the flow on the sector and non-sector edges of

. Since the goal is to encode whether a sector is selected or not, the flow of the sector edges can be either 0 or 1, while the non-sector edges can have arbitrary non-negative flows. It follows from the Ford-Fulkerson method that if the capacities are integer or infinite values, as is the case in

, then there exists a maximum flow

f such that

is an integer for every edge

[

18]. This statement guarantees that despite restricting the possible values of the "sector elements" in

to 0 or 1, a maximum flow can still be found. Finally, the last

m elements of

represent whether a dummy sector is selected or not for covering the targets, thus they can also have either 0 or 1 values.

The goal formulated with cost optimization is the same as in

: to minimize the number of dummy sectors used for covering the targets. Consequently, the cost vector,

, is basically the same as

:

The constraints of

represent the conservation of flows rule, the capacity constraints, and they also ensure the existence of a k-valued flow from

s to

t in

. In addition, a slight modification of Inequalities

2 and should also be included in order to guarantee that a solution can only encode a permissible sector selection which covers all of the targets.

For vertex

v of

denote by

,

the sets of ingoing and outgoing edges of

v, respectively. Now,

can be defined as follows:

where

n and

m are the numbers of sensors and targets, respectively, and

Thus, Equality guarantees that a flow of value

k leaves

s in

, while Equality

5 and Inequality ensure the arrival of this flow at

t.

The definitions of

and

are very similar to those given in Inequalities

2 and . The only difference is the presence of non-sector edges in this case. However, these have no role here. Thus,

and

can be defined in the same way as before for sector edges and dummy sectors, and can be set to 0 for non-sector edges.

Based on what has been discussed so far in this section, it is easy to see that a solution to indeed represents a solution to the MTCBC-k problem.

Further considerations.

Note that the number of sensors to be used can be limited in the same way as in the case of . The same can be said about the possible cost assignment to real sectors and the opportunity to distinguish between targets.

5.3. Supplementary ILP Formulations

In what follows, it will be important to find a permissible sector selection that provides k-barrier coverage on . Moreover, among the permissible sector selections that also ensure k-barrier coverage should contain the minimal number of sectors – which entails that it also contains the minimal number of sensors. Next, it is shown how can be transformed into another ILP, , whose solution encodes a permissible sector selection with the desired property.

Targets play no role in the formation of k-barrier coverage. Thus the elements of the variable of , , only represent the sector and non-sector edges of , i.e., the dummy sectors are not included. Inequality also needs to be removed from the constraints. The rest of the constraints of can be preserved without any further change. Note that in all of these constraints in the positions of the dummy sectors only 0s appeared, consequently, the deletion of these columns does not result in any significant changes.

The cost vector,

should be defined as follows:

needs to be minimized.

With this, is fully defined. It is easy to see that a solution of encodes a permissible sector selection that provides k-barrier coverage over . Moreover, the minimization in the objective guarantees that the number of involved sectors is minimal.

Maximum level of barrier coverage.

To decide how strict barrier coverage one wishes to ensure, one must know the maximum level of barrier coverage that the sensor network is capable of providing. can easily be transformed into another ILP, , that answers this question.

The structure of the variable of

is the same as that in

. From the set of constraints in

, Equality , which guarantees the existence of a flow of value

k leaving

s, should be removed. The rest of the constraints can remain unchanged. As an objective, one should require that the value of the flow leaving

s be maximal. Thus,

should be defined in the same way as the coefficients of Equality

needs to be minimized.

Clearly, if

is a solution of

, then the value of

is equal to the maximum level of barrier coverage that

can provide over

. Note that

was already formulated in [

14]. Here, it was only reiterated for sake of completeness.